Biochar–Urea Peroxide Composite Particles Alleviate Phenolic Acid Stress in Pogostemon cablin Through Soil Microenvironment Modification

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Batch Experiment for Phenolic Acid Degradation and Analytical Characterization Methods

2.3. Pot Experiment Method

2.4. Determination of Physiological and Biochemical Indicators

2.4.1. Determination of Patchouli Growth Indexes

2.4.2. Determination of Patchouli Quality Indexes

2.4.3. Determination of Soil Physiochemical Properties and Enzyme Activities

2.4.4. Analysis of Microbial Diversity in Rhizosphere Soil of Patchouli

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Mechanism of Phenolic Acid Removal by BC-UP Composite Particles

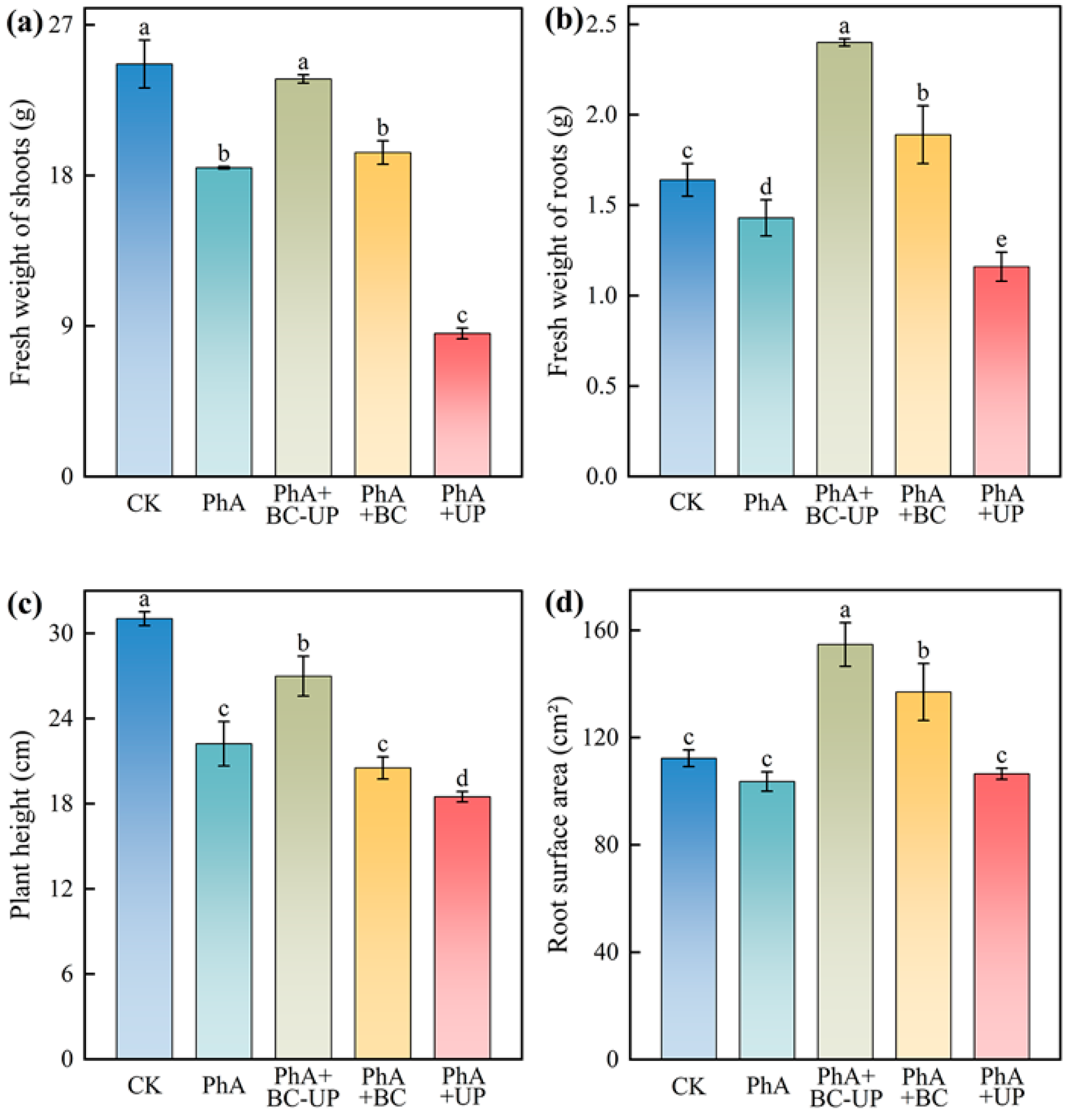

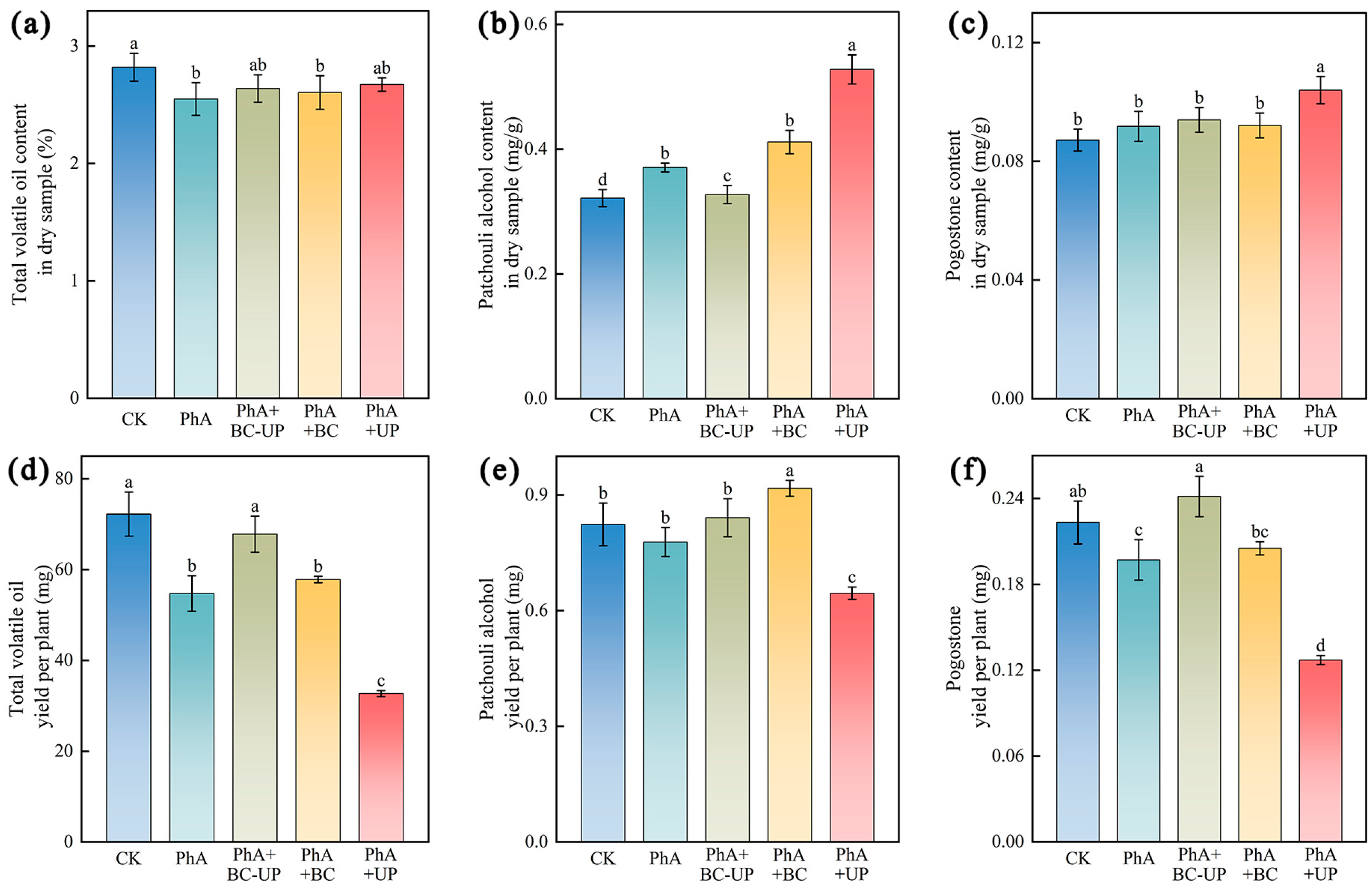

3.2. Effects of Different Exogenous Additives on Growth and Quality Indicators of Patchouli Cuttings

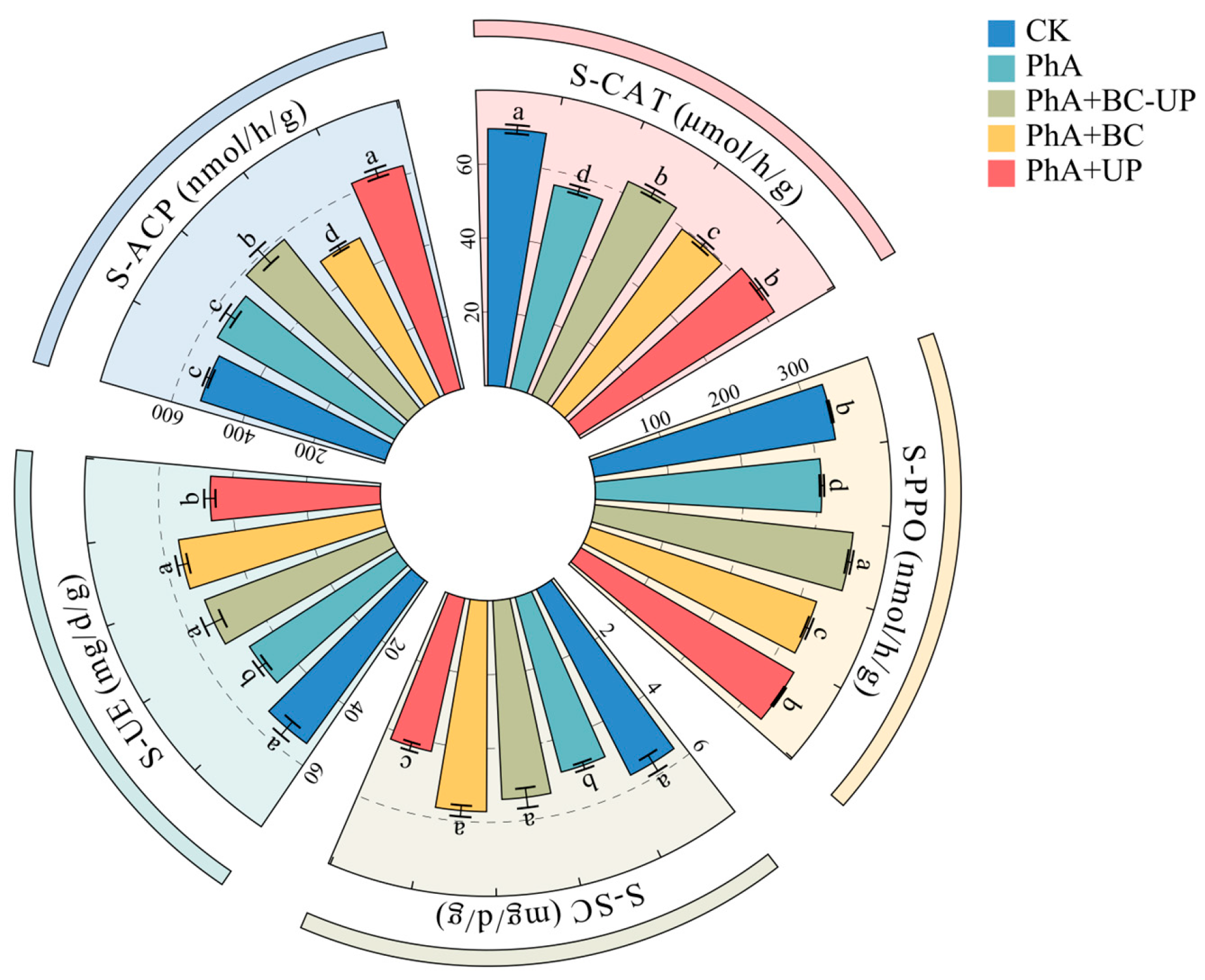

3.3. Effects of Different Exogenous Additives on Physicochemical Properties and Enzyme Activity of Patchouli Rhizosphere Soil

3.4. Effects of Different Exogenous Additives on Microbial Diversity in the Rhizosphere Soil of Patchouli

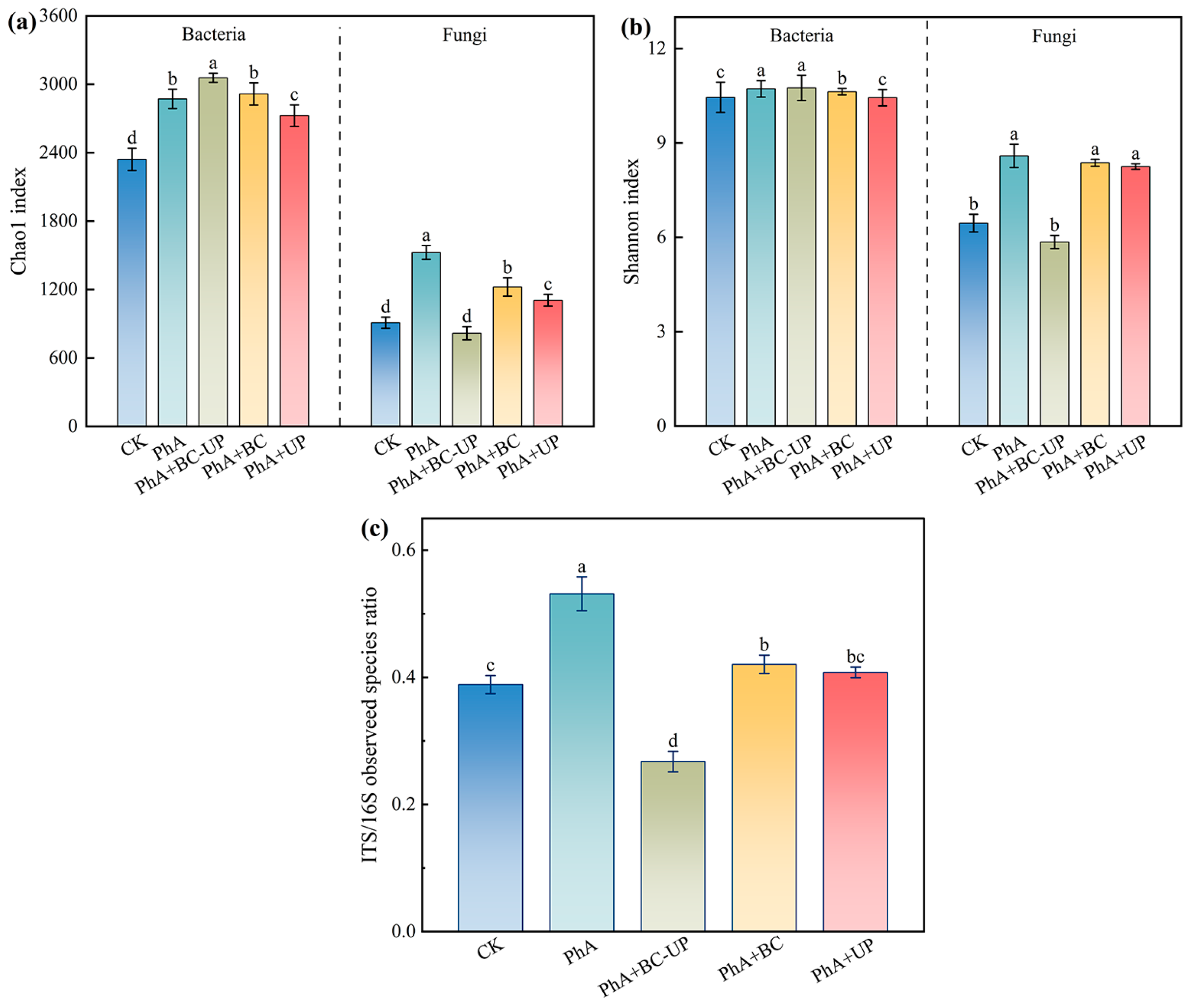

3.4.1. Alpha Diversity Analysis of Microbial Communities in the Rhizosphere Soil of Patchouli Treated with Different Exogenous Additives

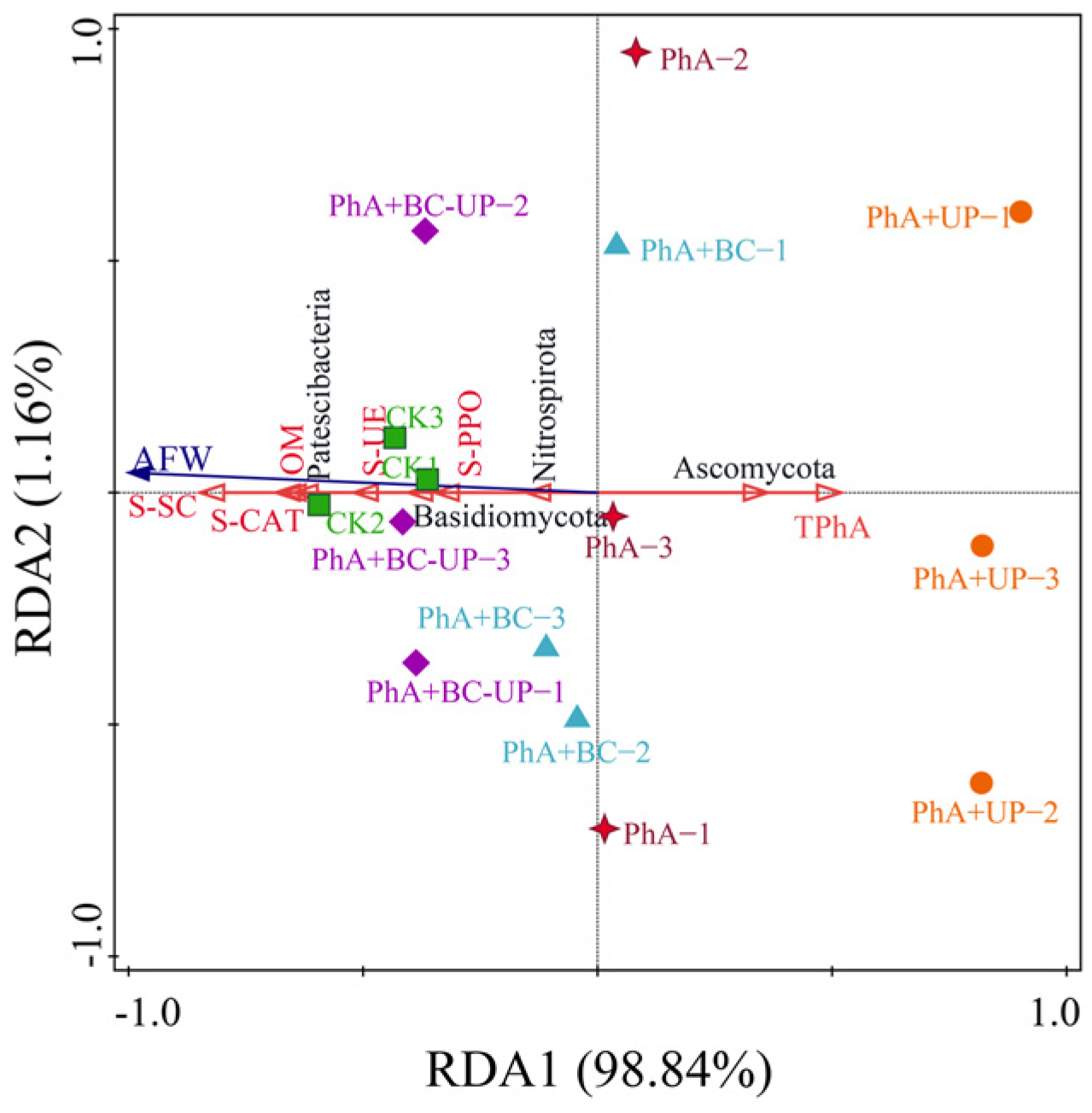

3.4.2. Beta Diversity Analysis of Microbial Communities in the Patchouli Rhizosphere Soil Treated with Different Exogenous Additives

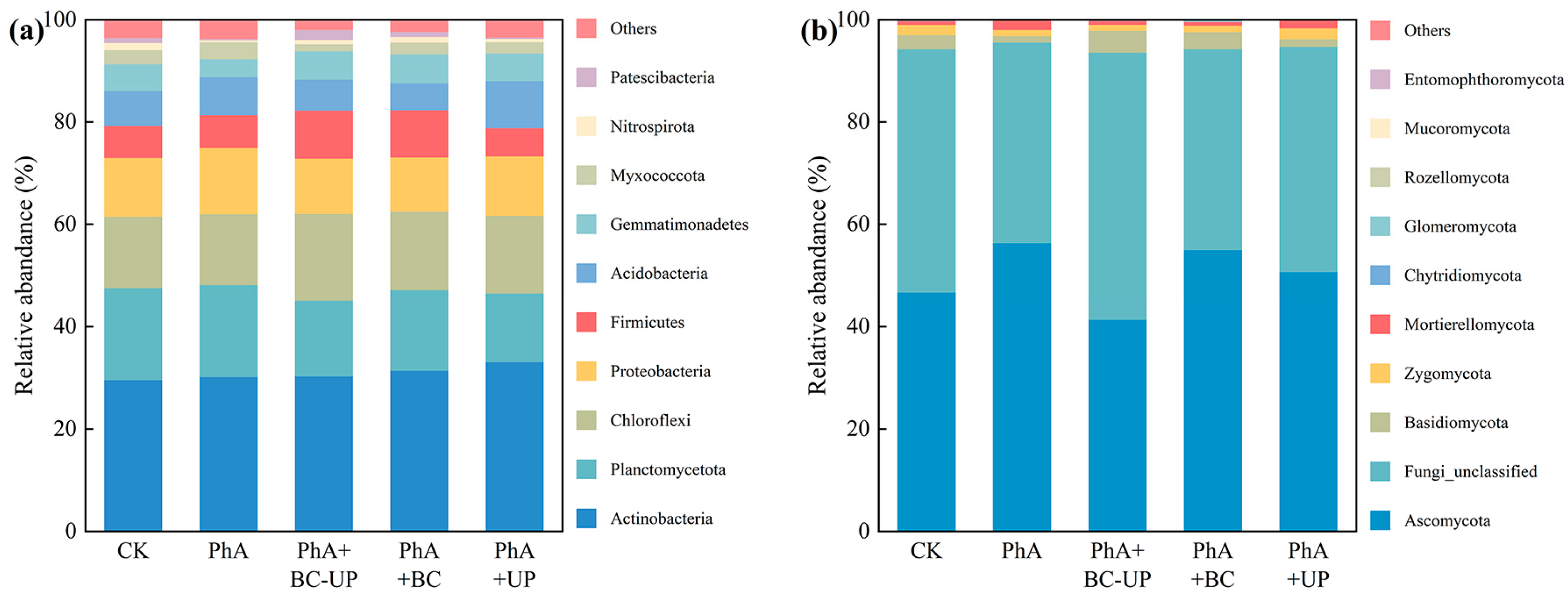

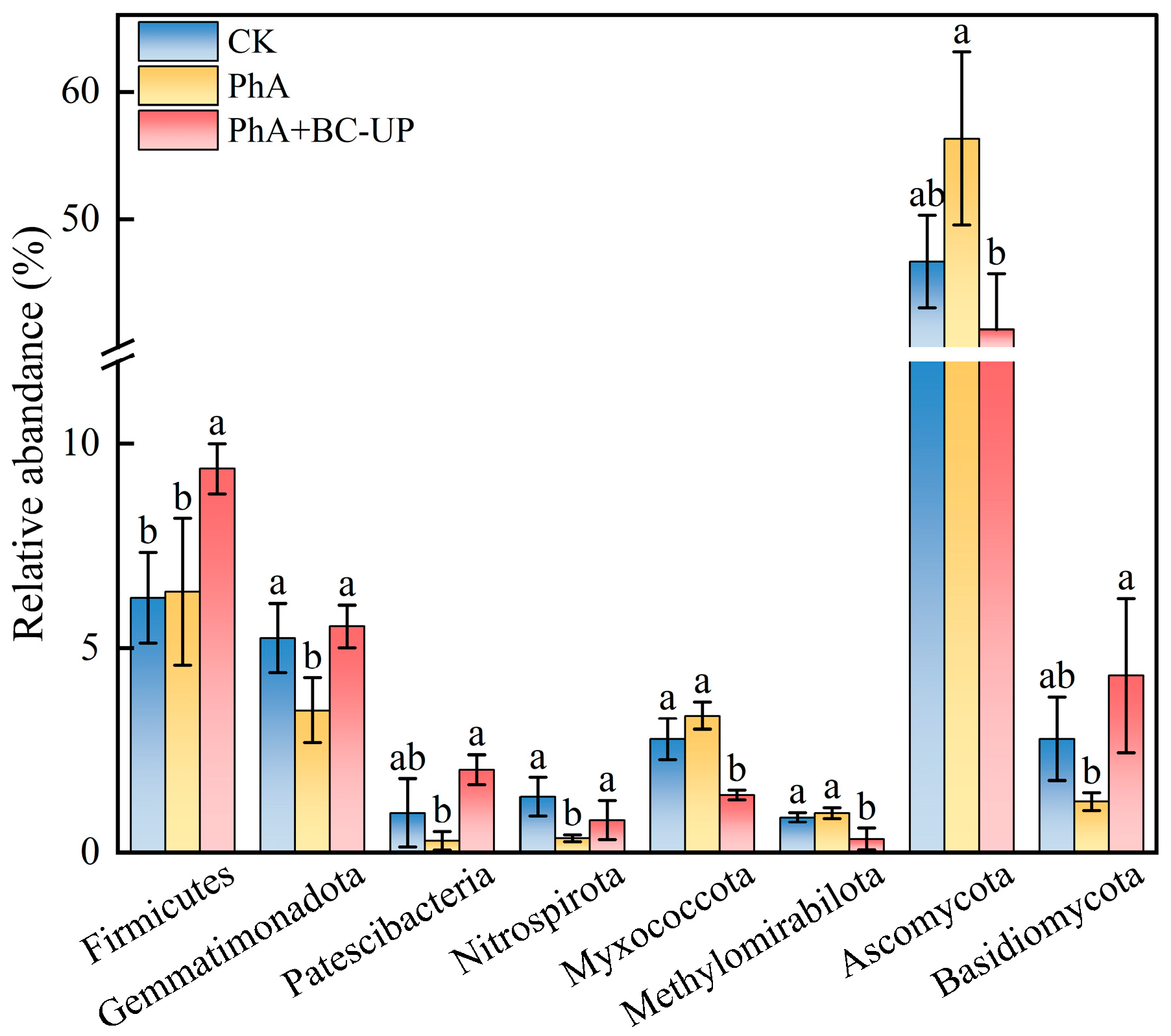

3.4.3. Effects of Different Treatments on Bacterial and Fungal Community Structures in Rhizosphere Soil

3.4.4. Screening of Biomarks in Patchouli Rhizosphere Soil Under Exogenous Phenolic Acid and Composite Particle Treatments

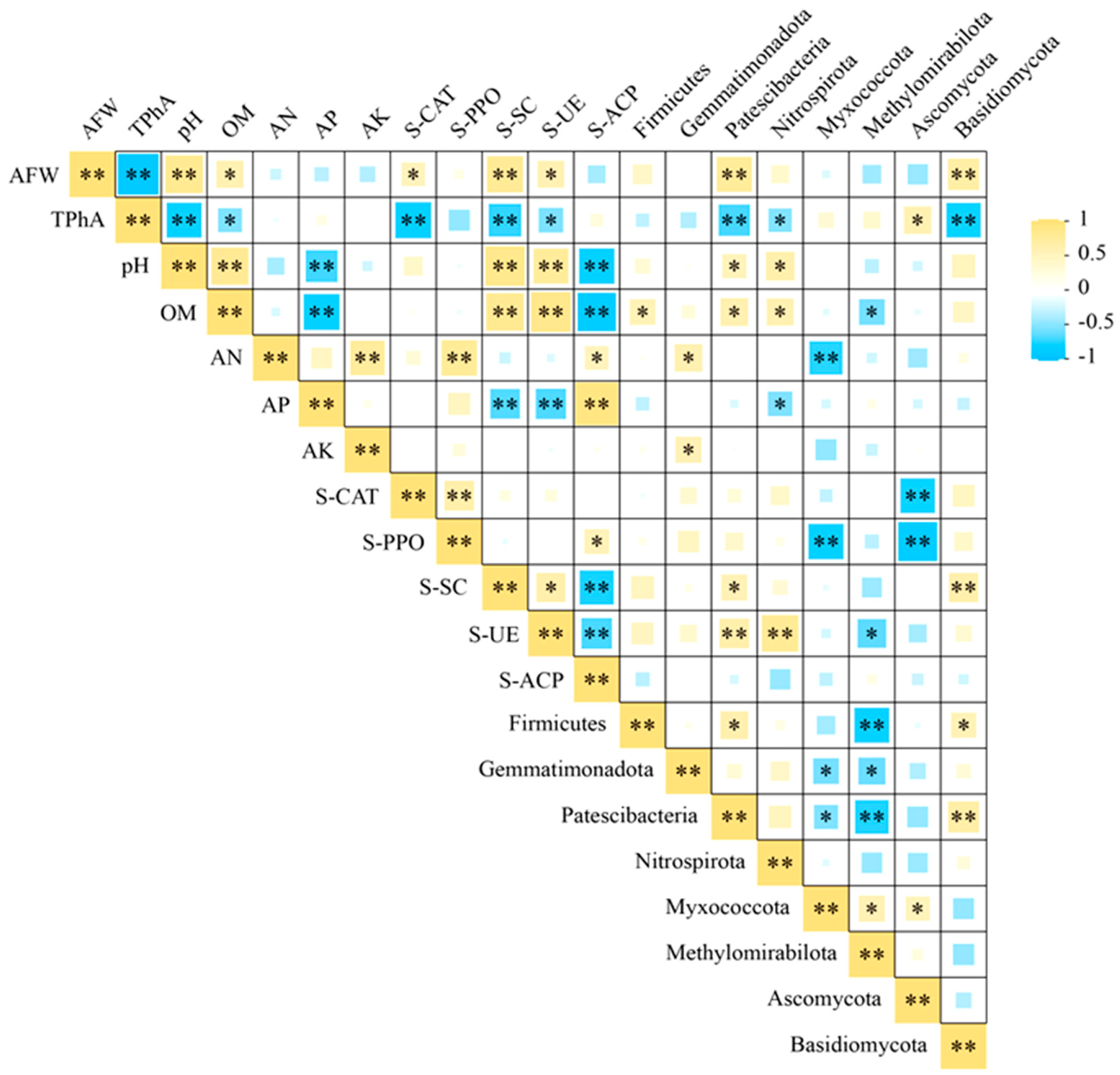

3.5. Correlation Analysis of Patchouli Biomass with Rhizosphere Soil Environmental Factors and Microbial Community Abundance

4. Discussion

4.1. From Phenolic Acid Stress-Induced Inhibition to Conditioner-Mediated Alleviation: Growth and Quality Responses in Patchouli

4.2. Soil Property and Enzyme Response to Phenolic Acid Stress and Conditioner Remediation

4.3. Shaping of Rhizosphere Microbial Community Structure by Phenolic Acid Stress and BC-UP Remediation

4.3.1. BC-UP Particles Reverse the Microbial Community “Fungalization” Trend

4.3.2. BC-UP Particles Reshape the Bacterial Community Structure: Enrichment of Bacterial Phyla with Putative Beneficial Functions

4.3.3. Fungal Community Shift Induced by BC-UP: Suppression of Pathogen-Associated Phyla

4.3.4. Integrated Analysis Reveals Synergistic Microecological Regulation by BC-UP Particles in Alleviating Autotoxicity

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Phuwajaroanpong, A.; Chaniad, P.; Horata, N.; Muangchanburee, S.; Kaewdana, K.; Punsawad, C. In vitro and In vivo antimalarial activities and toxicological assessment of Pogostemon Cablin (Blanco) Benth. J. Evid.-Based Integr. Med. 2020, 25, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Cao, S.; Wu, Y.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, C.; Yao, G.; Yu, J.; Yang, D.; Zhang, J. Integrated analysis of physiological, mRNA sequencing, and miRNA sequencing data reveals a specifc mechanism for the response to continuous cropping obstacles in Pogostemon cablin roots. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 853110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Su, Y.; Hussain, A.; Xiong, L.; Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Meng, Z.; Dong, Z.; Yu, G. Complete genome sequence of the Pogostemon cablin bacterial wilt pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum strain SY1. Genes Genom. 2023, 45, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, H.; Deng, Z.; Li, Z.; Mai, Y.; Li, G.; He, H. A practical random mutagenesis system for Ralstonia solanacearum strains causing bacterial wilt of Pogostemon cablin using Tn5 transposon. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 35, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Qin, S.; He, H.; Mao, R.; Liang, Z. Dynamic analysis of physiological indices and transcriptome profiling revealing the mechanisms of the allelopathic effects of phenolic acids on Pinellia ternata. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1039507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, W.; Ai, L.; You, J.; Liu, H.; You, J.; Wang, H.; Wassie, M.; Wang, M.; et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals novel insights into the continuous cropping induced response in Codonopsis tangshen, a medicinal herb. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 141, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fan, S.; Qin, J.; Dai, J.; Zhao, F.; Gao, L.; Lian, X.; Shang, W.; Xu, X.; Hu, X. Changes in the microbiome in the soil of an American ginseng continuous plantation. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 572199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Yang, Q. The combination of biochar and Bacillus subtilis biological agent reduced the relative abundance of pathogenic bacteria in the rhizosphere soil of Panax notoginseng. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Luo, X.; Liu, J.; Yao, M.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Huang, L.u.; Sun, X. Promoting international acceptance of clinical studies about traditional Chinese medicine interventions. Sci. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2025, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Li, W. Phase changes of continuous cropping obstacles in strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) production. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 155, 103626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clocchiatti, A.; Hannula, S.E.; Berg, M.V.D.; Hundscheid, M.P.J.; Boer, W.D. Evaluation of phenolic root exudates as stimulants of saptrophic fungi in the rhizosphere. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 644046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Shen, J.; Peng, Z.; Xu, Y.; Li, Z.; Liang, J.; Wei, Q.; Zhao, H.; Huang, J. Biochar-dual oxidant composite particles alleviate the oxidative stress of phenolic acid on tomato seed germination. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Qin, X.; Wu, L.; Li, Z.; Lin, S.; Lin, W.; Zhu, Q.; Khan, M.U.; et al. Insights into the mechanism of proliferation on the special microbes mediated by phenolic acids in the Radix pseudostellariae rhizosphere under continuous monoculture regimes. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Li, Q.; Huang, X.; Chen, C. Analysis transcriptome and phytohormone changes associated with the allelopathic effects of ginseng hairy roots induced by different-polarity ginsenoside components. Molecules 2024, 29, 1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, D.; Hu, X.; Zhang, J. Isolation and identification of the water-soluble components of Pogostemon cablin. In Chemical Engineering III; CRC Press: Beijing, China, 2013; pp. 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Song, X.; Zhu, G.; Hu, X. Autotoxicity in Pogostemon cablin and their allelochemicals. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2015, 25, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Ding, Y.; Nie, Y.; Wang, X.; An, Y.; Roessner, U.; Walker, R.; Du, B.; Bai, J. Plant metabolomics integrated with transcriptomics and rhizospheric bacterial community indicates the mitigation effects of Klebsiella oxytoca P620 on p-hydroxybenzoic acid stress in cucumber. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 415, 125756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šoln, K.; Klemenčič, M.; Koce, J.D. Plant cell responses to allelopathy: From oxidative stress to programmed cell death. Protoplasma 2022, 259, 1111–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Z.; Zhou, S.; Shah, A.; Arafat, Y.; Rizvi, S.A.H.; Shao, H. Plant allelopathy in response to biotic and abiotic factors. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadiji, A.E.; Adeniji, A.; Lanrewaju, A.A.; Babalola, O.O. Dynamics of soil microbiome and allelochemical interactions: An overview of current knowledge and prospects. Ann. Microbiol. 2025, 75, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Wang, F.; Huang, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Ye, X.; Li, Z.; Hou, Y.; Huang, Y.; Ma, J.; et al. Metabolic Pathway Involved in 6-Chloro-2-Benzoxazolinone Degradation by Pigmentiphaga sp. Strain DL-8 and Identification of the Novel Metal-Dependent Hydrolase CbaA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 4169–4179, Erratum in Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e03488-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión, V.J.; Perez-Jaramillo, J.; Cordovez, V.; Tracanna, V.; De Hollander, M.; Ruiz-Buck, D.; Mendes, L.W.; Van Ijcken, W.F.J.; Gomez-Exposito, R.; Elsayed, S.S.; et al. Pathogen-induced activation of disease-suppressive functions in the endophytic root microbiome. Science 2019, 366, 606–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revillini, D.; David, A.S.; Reyes, A.L.; Knecht, L.D.; Vigo, C.; Allen, P.; Searcy, C.A.; Afkhami, M.E. Allelopathy-selected microbiomes mitigate chemical inhibition of plant performance. New Phytol. 2023, 240, 2007–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámiz, B.; López-Cabeza, R.; Velarde, P.; Spokas, K.A.; Cox, L. Biochar changes the bioavailability and bioefficacy of the allelochemical coumarin in agricultural soils. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 834–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Elcin, E.; He, L.; Vithanage, M.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Deng, Y.; Niazi, N.K.; Shaheen, S.M.; et al. Using biochar for the treatment of continuous cropping obstacle of herbal remedies: A review. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 193, 105127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Qin, X.; Wu, H.; Li, F.; Wu, J.; Zheng, L.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Y.; Lin, S.; et al. Biochar mediates microbial communities and their metabolic characteristics under continuous monoculture. Chemosphere 2020, 246, 125835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Xu, W.; Guan, H.; Wang, K.; Xiang, P.; Wei, F.; Yang, S.; Miao, C.; Ma, L. Biochar increases Panax notoginseng’s survival under continuous cropping by improving soil properties and microbial diversity. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 850, 157990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Wang, F.; Cao, F.; Guo, J.; Sun, H. Desorption of atrazine in biochar-amended soils: Effects of root exudates and the aging interactions between biochar and soil. Chemosphere 2018, 212, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Pignatello, J.J.; Qu, D.; Xing, B. Activation of hydrogen peroxide and solid peroxide reagents by phosphate ion in alkaline solution. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2016, 33, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhang, X.; Xue, Y. Application of calcium peroxide in water and soil treatment: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 337, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Shi, W.; Kronzucker, H.J.; Li, Y. Oxygenation promotes vegetable growth by enhancing P nutrient availability and facilitating a stable soil bacterial community in compacted soil. Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 230, 105686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Lin, C.; Fan, K.; Ying, J.; Li, H.; Qin, J.; Qiu, R. The use of urea hydrogen peroxide as an alternative N-fertilizer to reduce accumulation of arsenic in rice grains. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 349, 119489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.; Hughes, E.W.; Giguère, P.A. The crystal structure of the urea-hydrogen peroxide addition compound CO(NH2)2·H2O2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1941, 63, 1507–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Zhou, C.; Xie, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhou, C.; Li, X.; Du, Y.; Lu, F. A new method for simultaneous determination of 14 phenolic acids in agricultural soils by multiwavelength HPLC-PDA analysis. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 14939–14944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R.; Li, A.; Tan, X.; Tang, X.; He, X.; Wang, L.; Kang, J.; Li, S.; Liu, Y. Patchouli essential oil extends the lifespan and healthspan of Caenorhabditis elegans through JNK-1/DAF-16. Life Sci. 2025, 360, 123270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Jin, C.; Liu, A.; Chen, Y.; Hu, Y. Physiological and transcriptomic analyses to reveal underlying phenolic acid action in consecutive monoculture problem of Polygonatum odoratum. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanjana, N.; Li, Y.; Shen, Z.; Mao, J.; Zhang, L. Effect of phenolics on soil microbe distribution, plant growth, and gall formation. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 924, 171329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, M.M.; Kakouridis, A.; Starr, E.; Nguyen, N.; Shi, S.; Pett-Ridge, J.; Nuccio, E.; Zhou, J.; Firestone, M.; Giovannoni, S.J. Fungal-bacterial cooccurrence patterns differ between arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and nonmycorrhizal fungi across soil niches. mBio 2021, 12, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Feng, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, X.; Jin, W.; Liang, Z. Identification of phenolic acids in rhizosphere soil of continuous cropping of Salvia miltiorrhiza Bge. Allelopath. J. 2021, 53, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Weston, L.A.; Li, M.; Zhu, X.; Weston, P.A.; Feng, F.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, L.; Gu, L.; Zhang, Z. Rehmannia glutinosa replant issues: Root exudate-rhizobiome interactions clearly influence replant success. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, J.; Xia, P. Continuous cropping obstacles of medicinal plants: Focus on the plant-soil-microbe interaction system in the rhizosphere. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 328, 112927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Guan, H.; Wang, R.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Li, W.; Xiang, P.; Xu, W. Effects of tobacco stem-derived biochar on soil properties and bacterial community structure under continuous cropping of Bletilla striata. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2021, 21, 1318–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Liu, Y.; Chang, P.; Hsieh, Y.; Tzou, Y. Inhibition of continuous cropping obstacle of celery by chemically modified biochar: An efficient approach to decrease bioavailability of phenolic allelochemicals. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 348, 119316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Luo, M.; Wang, Q.; Wu, X. Bacillus cereus WL08 immobilized on tobacco stem charcoal eliminates butylated hydroxytoluene in soils and alleviates the continuous cropping obstacle of Pinellia ternata. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 450, 131091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, T.; Yuan, Z.; Gustave, W.; Luan, T.; He, L.; Jia, Z.; Zhao, X.; Wang, S.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. Challenges of continuous cropping in Rehmannia glutinosa: Mechanisms and mitigation measures. Soil Environ. Health 2025, 3, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, S.; Young, T.; Macinnis-Ng, C.; Nyugen, T.V.; Duxbury, M.; Alfaro, A.C.; Leuzinger, S. Untargeted metabolomics in halophytes: The role of different metabolites in New Zealand mangroves under multi-factorial abiotic stress conditions. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 173, 103993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ma, L.; Wei, R.; Ma, Y.; Ma, T.; Dang, J.; Chen, Z.; Li, S.; Ma, S.; Chen, G. Effect of continuous cropping on growth and lobetyolin synthesis of the medicinal plant Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. based on the integrated analysis of plant-metabolite-soil factors. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 19604–19617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, C.; El-Desouki, Z.; Riaz, M.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Ding, J.; Chen, Z.; Liu, H.; et al. Effects of exogenous application of phenolic acid on soil nutrient availability, enzyme activities, and microbial communities. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, A.; Li, X.; Zhang, D.; Yang, X.; Shi, Y.; Dong, L.; Lei, F.; Lv, M.; Sun, L.; Sun, X. Changes in herbaceous peony growth and rhizosphere soil after benzoic and gallic acids application. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 344, 114117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Hussain, Q.; Khan, K.S.; Akmal, M.; Ijaz, S.S.; Hayat, R.; Khalid, A.; Azeem, M.; Rashid, M. Response of soil microbial biomass and enzymatic activity to biochar amendment in the organic carbon deficient arid soil: A 2-year field study. Arab. J. Geosci. 2019, 12, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, P.; Chen, Q.; Lu, M.; Steinberg, C.E.W.; Wu, M. Biochar reduces generation and release of benzoic acid from soybean root. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 5026–5035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.; Piao, J.; Miao, S.; Che, W.; Li, X.; Li, X.B.; Shiraiwa, T.; Tanaka, T.; Taniyoshi, K.; Hua, S.; et al. Long-term effects of biochar one-off application on soil physicochemical properties, salt concentration, nutrient availability, enzyme activity, and rice yield of highly saline-alkali paddy soils: Based on a 6-year field experiment. Biochar 2024, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Waigi, M.G.; Gudda, F.O.; Zhang, C.; Ling, W. Promoted oxidation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soils by dual persulfate/calcium peroxide system. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 758, 143680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, M.; Sweygers, N.; Al-Salem, S.; Appels, L.; Aminabhavi, T.M.; Dewil, R. Biochar for soil applications-sustainability aspects, challenges and future prospects. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 428, 131189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, H.; Luo, S.; Man, H.; Shi, G. Phenolic acids alleviated consecutive replant problems in lily by regulating its allelopathy on rhizosphere microorganism under chemical fertiliser reduction with microbial agents in conjunction with organic fertiliser application. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 205, 105780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Kuzyakov, Y. Mechanisms and implications of bacterial-fungal competition for soil resources. ISME J. 2024, 18, wrae073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Wu, C.; Fan, L.; Kang, M.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Xu, X.; Yao, Y. Effects of the Long-term continuous cropping of Yongfeng yam on the bacterial community and function in the rhizospheric soil. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Fan, X.; Fu, P.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Hua, D. Anaerobic digestion of wood vinegar wastewater using domesticated sludge: Focusing on the relationship between organic degradation and microbial communities (archaea, bacteria, and fungi). Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 374, 126384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, L.; Yao, Y.; Lei, C.; Hong, C.; Zhu, W.; Zhu, F.; Wang, W.; Lu, T.; Qi, X. Declined symptoms in Myrica rubra: The influence of soil acidification and rhizosphere microbial communities. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 313, 111892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Li, H.; Ma, Q.; Dong, Q.; Gao, J.; Zhang, F.; Xie, H. Mitigating continuous cropping challenges in alkaline soils: The role of biochar in enhancing soil health, microbial dynamics, and pepper productivity. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 234, 121576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Lei, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Yang, G.; Pan, H.; Hou, Y.; Yu, J.; Sun, K.; Dong, Y. The influence of aerated irrigation on the evolution of dissolved organic matter based on three-dimensional fluorescence spectrum. Agronomy 2023, 13, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ji, X.; Li, X.; Wei, Y.; Zi, F.; Tan, Y. Differences in autotoxic substances and microbial community in the root space of Panax notoginseng coinducing the occurrence of root rot. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90, e0228723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Yin, C.; Pan, F.; Wang, X.; Xiang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Tian, C.; Chen, J.; Mao, Z. Analysis of the fungal community in apple replanted soil around Bohai Gulf. Hortic. Plant J. 2018, 4, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma-Poudyal, D.; Schlatter, D.; Yin, C.; Hulbert, S.; Paulitz, T. Long-term no-till: A major driver of fungal communities in dryland wheat cropping systems. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Gao, J.; Chang, D.; He, T.; Cai, H.; Wang, M.; Li, C.; Luo, Z.; E, Y.; Meng, J.; et al. Biochar contributes to resistance against root rot disease by stimulating soil polyphenol oxidase. Biochar 2023, 5, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanov, A.A.; Shulaev, N.A.; Vasilchenko, A.S. The Ecological Strategy Determines the Response of Fungi to Stress: A Study of the 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol Activity Against Aspergillus and Fusarium Species. J. Basic Microbiol. 2025, 65, e2400334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, L.; Fan, S.; Lu, X.; Zhang, X. Effect of compost as a soil amendment on the structure and function of fungal diversity in saline-alkali soil. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2025, 9, 100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Treatment | Total Phenolic Acids (μg/g) | pH | Organic Matter (g/kg) | Alkali-Hydrolysable N (mg/kg) | Available P (mg/kg) | Available K (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 6.56 ± 0.12 d | 6.36 ± 0.01 a | 25.85 ± 0.58 b | 90.76 ± 0.87 d | 162.34 ± 1.42 b | 83.94 ± 0.76 b |

| PhA | 10.73 ± 0.49 a | 5.51 ± 0.06 d | 22.85 ± 0.57 c | 87.51 ± 1.21 d | 165.11 ± 1.69 ab | 83.26 ± 1.36 b |

| PhA+BC-UP | 6.73 ± 0.12 d | 5.66 ± 0.07 c | 25.12 ± 0.91 b | 120.51 ± 1.65 b | 166.72 ± 2.21 a | 86.53 ± 2.39 b |

| PhA+BC | 7.32 ± 0.09 c | 5.95 ± 0.07 b | 27.85 ± 0.32 a | 112.17 ± 3.1 c | 154.38 ± 0.87 c | 95.57 ± 0.48 a |

| PhA+UP | 8.70 ± 0.08 b | 5.34 ± 0.08 e | 21.40 ± 0.18 d | 153.96 ± 3.05 a | 168.58 ± 3.12 a | 96.68 ± 3.14 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tu, Y.; Chen, B.; Wei, Q.; Xu, Y.; Peng, Y.; Li, Z.; Liang, J.; Zhuo, L.; Zhong, W.; Huang, J. Biochar–Urea Peroxide Composite Particles Alleviate Phenolic Acid Stress in Pogostemon cablin Through Soil Microenvironment Modification. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2772. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122772

Tu Y, Chen B, Wei Q, Xu Y, Peng Y, Li Z, Liang J, Zhuo L, Zhong W, Huang J. Biochar–Urea Peroxide Composite Particles Alleviate Phenolic Acid Stress in Pogostemon cablin Through Soil Microenvironment Modification. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2772. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122772

Chicago/Turabian StyleTu, Yuting, Baozhu Chen, Qiufang Wei, Yanggui Xu, Yiping Peng, Zhuxian Li, Jianyi Liang, Lifang Zhuo, Wenliang Zhong, and Jichuan Huang. 2025. "Biochar–Urea Peroxide Composite Particles Alleviate Phenolic Acid Stress in Pogostemon cablin Through Soil Microenvironment Modification" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2772. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122772

APA StyleTu, Y., Chen, B., Wei, Q., Xu, Y., Peng, Y., Li, Z., Liang, J., Zhuo, L., Zhong, W., & Huang, J. (2025). Biochar–Urea Peroxide Composite Particles Alleviate Phenolic Acid Stress in Pogostemon cablin Through Soil Microenvironment Modification. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2772. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122772