Designing a Novel Multi-Epitope Trivalent Vaccine Against NDV, AIV and FAdV-4 Based on Immunoinformatics Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protein Sequence Retrieval

2.2. Prediction of Linear B-Cell Epitopes

2.3. Prediction of CTL Epitopes

2.4. Prediction of HTL Epitopes

2.5. Multiple Epitope Antigens Design

2.6. Molecular Docking

2.7. NFAF Expression and Purification

2.8. Immunoreactivity Detection

2.9. Isolation of PBMC from Chickens

2.10. Effects of NFAF on Cytokine mRNA Expression Profiles in Chicken PBMC

2.11. Statistical Analysis of Data

3. Results

3.1. Screening for Immunodominant B Cell, CTL and HTL Epitopes

3.2. Construction and Evaluation of Multi-Epitope Vaccines

3.3. Secondary/Tertiary Structure Prediction and 3D Model Refinement

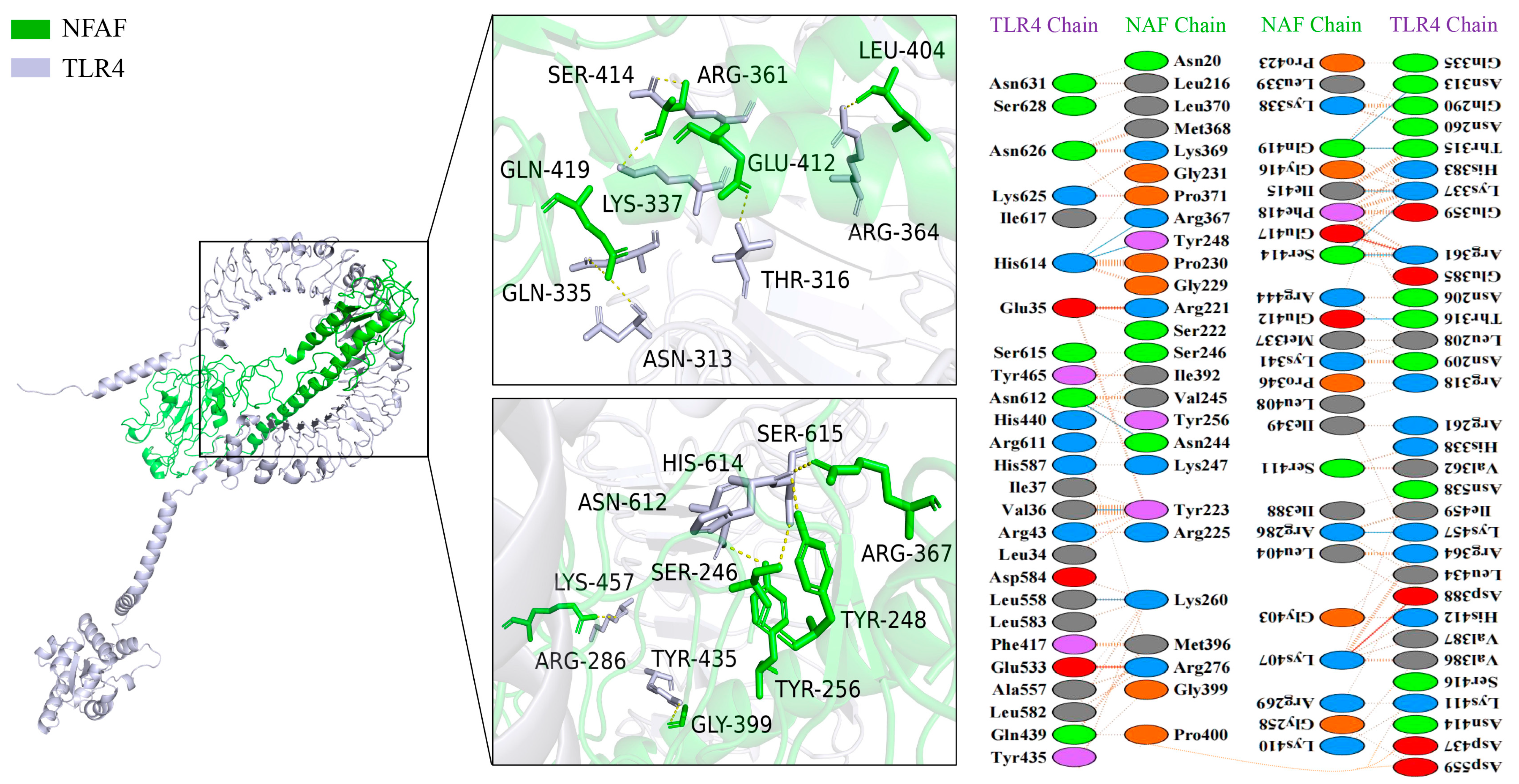

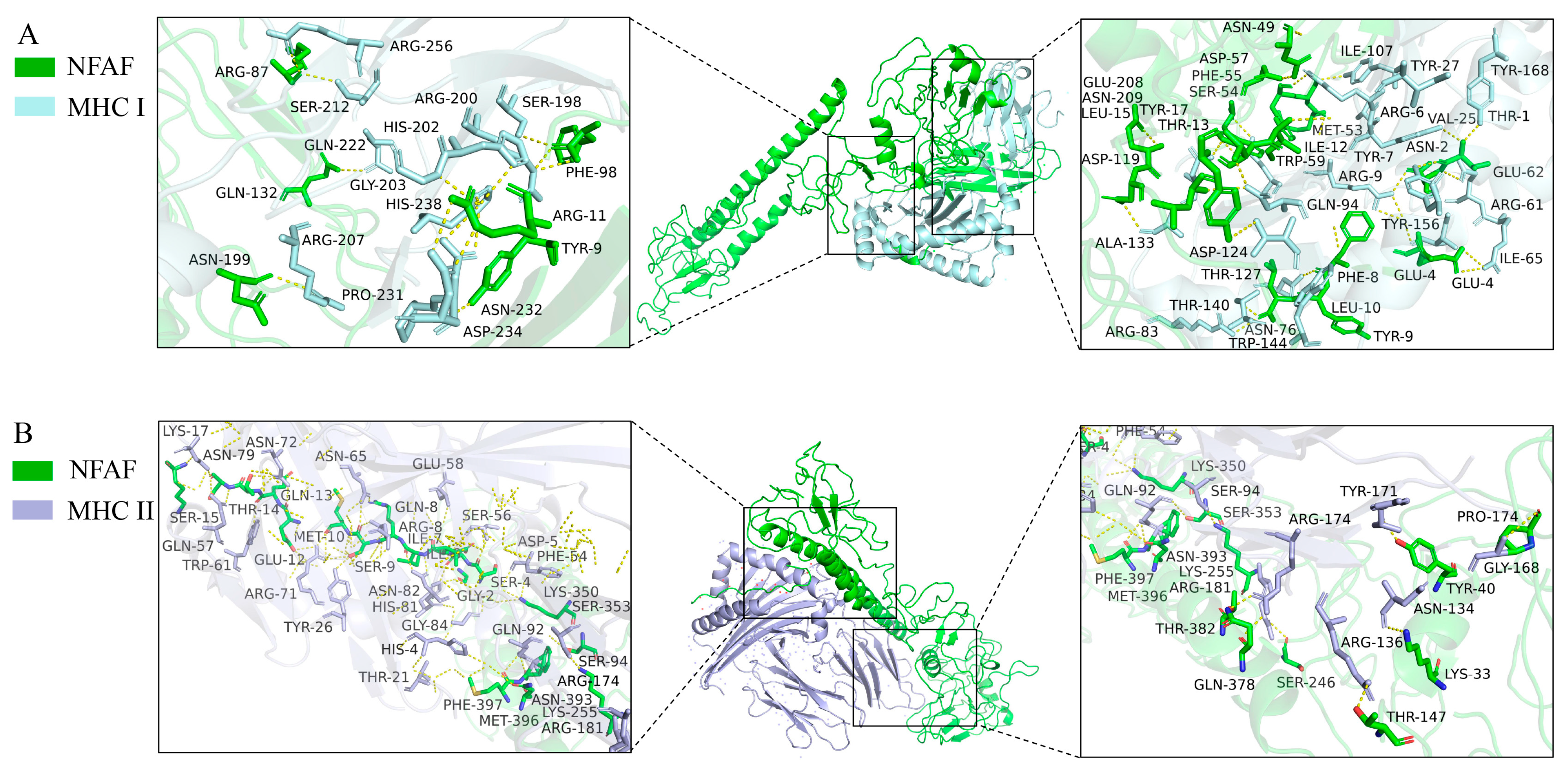

3.4. Molecular Docking of NFAF with TLRs, MHC I, and MHC II

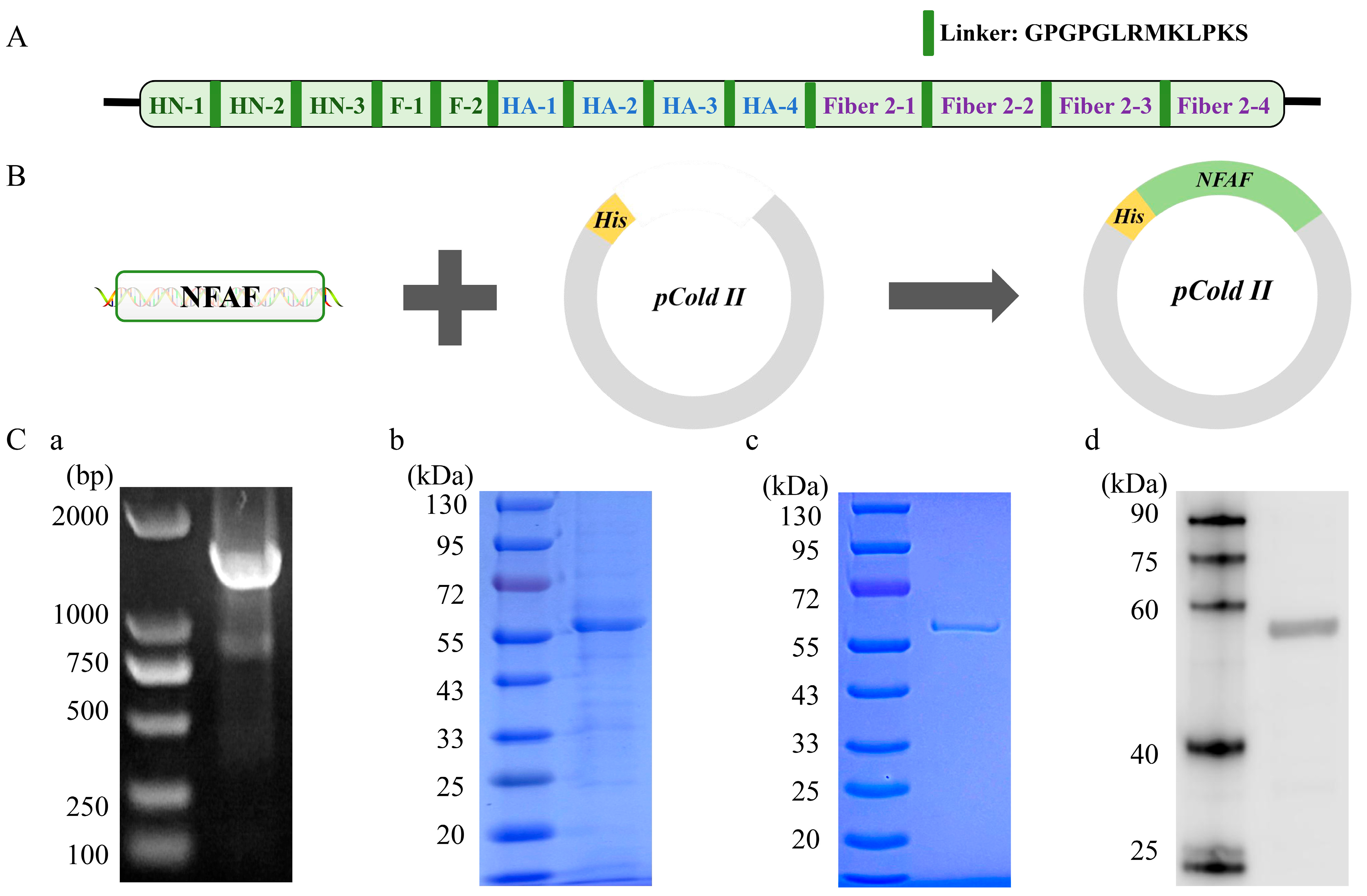

3.5. Expression and Purification of Recombinant Chimeric Protein NFAF

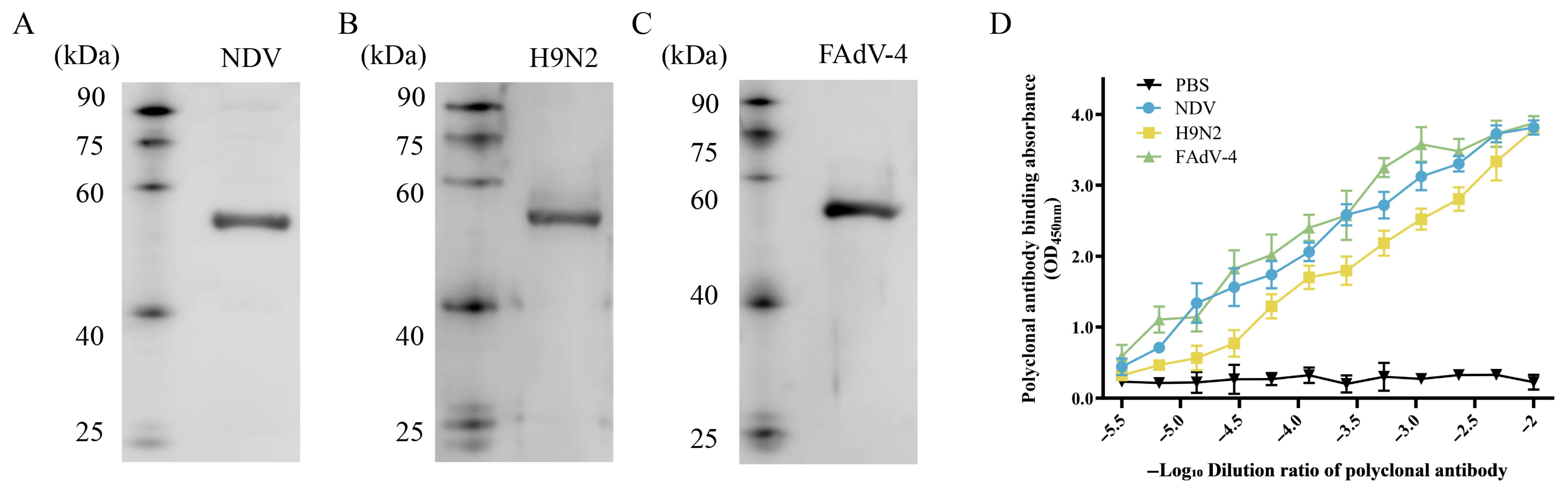

3.6. In Vitro Validation of the Antigenicity of NFAF

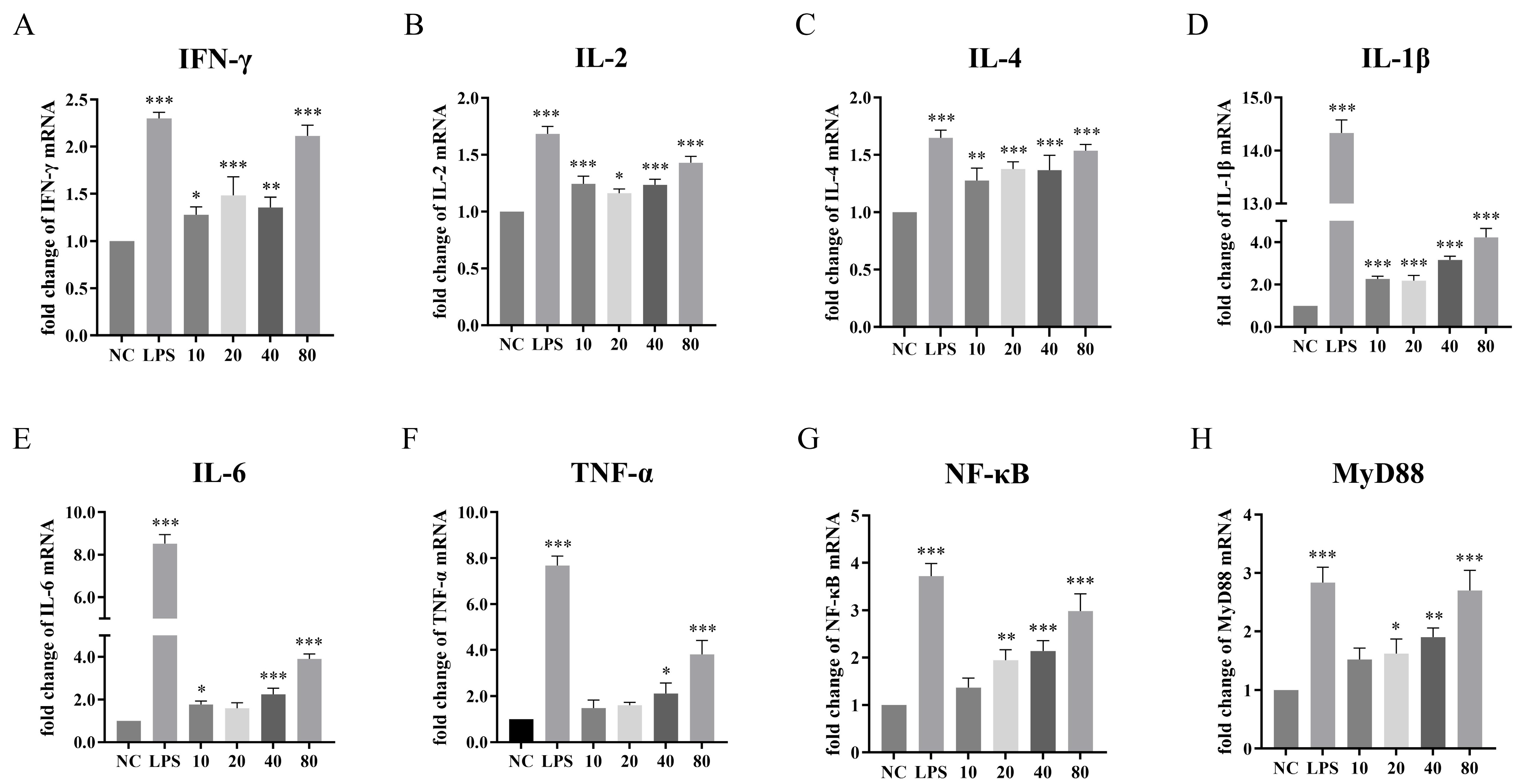

3.7. Effects of NFAF on the Transcription of Cytokines in Chicken PBMC

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dimitrov, K.M.; Abolnik, C.; Afonso, C.L.; Albina, E.; Bahl, J.; Berg, M.; Briand, F.X.; Brown, I.H.; Choi, K.S.; Chvala, I.; et al. Updated unified phylogenetic classification system and revised nomenclature for Newcastle disease virus. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019, 74, 103917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirrmacher, V. Molecular Mechanisms of Anti-Neoplastic and Immune Stimulatory Properties of Oncolytic Newcastle Disease Virus. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, Y.W.; Yang, H.M.; Jin, J.H.; Zhao, J.; Xue, J.; Zhang, G.Z. Recombinant Newcastle disease virus (NDV) La Sota expressing the haemagglutinin-neuraminidase protein of genotype VII NDV shows improved protection efficacy against NDV challenge. Avian Pathol. 2019, 48, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.; O’Kennedy, M.M.; Ross, C.S.; Lewis, N.S.; Abolnik, C. The production of Newcastle disease virus-like particles in Nicotiana benthamiana as potential vaccines. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1130910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peacock, T.H.P.; James, J.; Sealy, J.E.; Iqbal, M. A Global Perspective on H9N2 Avian Influenza Virus. Viruses 2019, 11, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, D.W.A.; Jones, D.T. The PSIPRED Protein Analysis Workbench: 20 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W402–W407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Bi, Y.; Wong, G.; Gray, G.C.; Gao, G.F.; Li, S. Epidemiology, Evolution, and Recent Outbreaks of Avian Influenza Virus in China. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 8671–8676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.; Li, R.; Chen, Y.; Deng, J.; Yu, S.; Lin, Q.; Chen, L.; Ren, T. Construction of a replication-defective recombinant virus and cell-based vaccine for H9N2 avian influenza virus. Vet. Res. 2025, 56, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinotti, F.; Kohnle, L.; Lourenço, J.; Gupta, S.; Hoque, M.A.; Mahmud, R.; Biswas, P.; Pfeiffer, D.; Fournié, G. Modelling the transmission dynamics of H9N2 avian influenza viruses in a live bird market. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Loh, L.; Kedzierski, L.; Kedzierska, K. Avian Influenza Viruses, Inflammation, and CD8(+) T Cell Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Zhu, S.; Govinden, R.; Chenia, H.Y. Multiple Vaccines and Strategies for Pandemic Preparedness of Avian Influenza Virus. Viruses 2023, 15, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cargnin Faccin, F.; Perez, D.R. Pandemic preparedness through vaccine development for avian influenza viruses. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2024, 20, 2347019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.N.; Guo, X.R.; Han, Y.; Tian, T.; Sun, J.; Lei, B.S.; Zhang, W.C.; Yuan, W.Z.; Zhao, K. The Cellular and Viral circRNAs Induced by Fowl Adenovirus Serotype 4 Infection. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 925953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Hou, L.; Wei, L.; Quan, R.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, J. Fowl Adenovirus Serotype 4 Induces Hepatic Steatosis via Activation of Liver X Receptor-α. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e01938-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Chang, J.; Lu, S.; Hu, P.; Zou, D.; Li, Y.; Li, F.; Liu, J.; Cao, Q.; Zhang, K.; et al. Multiantigen epitope fusion recombinant proteins from capsids of serotype 4 fowl adenovirus induce chicken immunity against avian Angara disease. Vet. Microbiol. 2023, 278, 109661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Liu, Q.; Li, T.; Geng, T.; Chen, H.; Xie, Q.; Shao, H.; Wan, Z.; Qin, A.; Ye, J. Fiber-1, Not Fiber-2, Directly Mediates the Infection of the Pathogenic Serotype 4 Fowl Adenovirus via Its Shaft and Knob Domains. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e00954-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ather, F.; Zia, M.A.; Habib, M.; Shah, M.S. Development of an ELISA for the detection of fowl adenovirus serotype-4 utilizing fiber protein. Biologicals 2024, 85, 101752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Yin, L.; Zhou, Q.; Li, Q.; Luo, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, C.; Cao, Y. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of recombinant fiber-2 protein in protecting SPF chickens against fowl adenovirus 4. Vaccine 2018, 36, 1203–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawade, D.B.; Teke, J.; Fapohunda, O.; Weerasinghe, K.; Usman, S.O.; Ige, A.O.; Clement David-Olawade, A. Leveraging artificial intelligence in vaccine development: A narrative review. J. Microbiol. Methods 2024, 224, 106998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Peng, C.; Cheng, P.; Wang, J.; Lian, J.; Gong, W. PP19128R, a Multiepitope Vaccine Designed to Prevent Latent Tuberculosis Infection, Induced Immune Responses In Silico and In Vitro Assays. Vaccines 2023, 11, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andongma, B.T.; Huang, Y.; Chen, F.; Tang, Q.; Yang, M.; Chou, S.H.; Li, X.; He, J. In silico design of a promiscuous chimeric multi-epitope vaccine against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Q.; Wei, M.; Wang, Y.; Pang, F. Design of a multi-epitope vaccine against goatpox virus using an immunoinformatics approach. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1309096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.; Demneh, F.M.; Rehman, B.; Almanaa, T.N.; Akhtar, N.; Pazoki-Toroudi, H.; Shojaeian, A.; Ghatrehsamani, M.; Sanami, S. In silico design of a novel multi-epitope vaccine against HCV infection through immunoinformatics approaches. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 267, 131517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoeder, C.T.; Gilchuk, P.; Sangha, A.K.; Ledwitch, K.V.; Malherbe, D.C.; Zhang, X.; Binshtein, E.; Williamson, L.E.; Martina, C.E.; Dong, J.; et al. Epitope-focused immunogen design based on the ebolavirus glycoprotein HR2-MPER region. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, F.; Ding, J. Design of a Recombinant Multivalent Epitope Vaccine Based on SARS-CoV-2 and Its Variants in Immunoinformatics Approaches. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 884433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Qi, J.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yang, G.; Ma, Z.; Li, Y. A novel conformational B-cell epitope prediction method based on mimotope and patch analysis. J. Theor. Biol. 2016, 394, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaseke, C.; Tano-Menka, R.; Senjobe, F.; Gaiha, G.D. The Emerging Role for CTL Epitope Specificity in HIV Cure Efforts. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 223, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivia-Olarte, H.; Requena, D.; Ramirez, M.; Saravia, L.E.; Izquierdo, R.; Falconi-Agapito, F.; Zavaleta, M.; Best, I.; Fernández-Díaz, M.; Zimic, M. Design of a predicted MHC restricted short peptide immunodiagnostic and vaccine candidate for Fowl adenovirus C in chicken infection. Bioinformation 2015, 11, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizarullah; Aditama, R.; Giri-Rachman, E.A.; Hertadi, R. Designing a Novel Multiepitope Vaccine from the Human Papilloma Virus E1 and E2 Proteins for Indonesia with Immunoinformatics and Molecular Dynamics Approaches. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 16547–16562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, Y. I-TASSER server: New development for protein structure and function predictions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W174–W181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zheng, W.; Li, Y.; Pearce, R.; Zhang, C.; Bell, E.W.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y. I-TASSER-MTD: A deep-learning-based platform for multi-domain protein structure and function prediction. Nat. Protoc. 2022, 17, 2326–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.; Park, H.; Heo, L.; Seok, C. GalaxyWEB server for protein structure prediction and refinement. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, W294–W297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randriamamisolonirina, N.T.; Razafindrafara, M.S.; Maminiaina, O.F. Design of a Multi-Epitope Vaccine against the Glycoproteins of Newcastle Disease Virus by Using an Immunoinformatics Approach. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 4007–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, M.; Wang, Y.; Yang, W.; Xu, M.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J. Epitope-Optimized Influenza Hemagglutinin Nanoparticle Vaccine Provides Broad Cross-Reactive Immunity against H9N2 Influenza Virus. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 20824–20840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| HN | F | HA | Fiber2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| XNJ14979.1 | AFA90008.1 | WNW65192.1 | WGG88700.1 |

| ACT34867.1 | ANZ52445.1 | AWK91180.1 | ADV35562.1 |

| ACT34869.1 | AFA89995.1 | QCU81185.1 | ADV35559.1 |

| ACT34870.1 | AEZ36087.1 | QCU81221.1 | XRL28504.1 |

| ARJ54661.1 | AEZ36086.1 | QQD47992.1 | XRL28492.1 |

| ACT34871.1 | XNJ14935.1 | QCU81173.1 | WMQ56317.1 |

| ARE59575.1 | QXI73422.1 | WHZ30396.1 | QNI22041.1 |

| ACT34873.1 | QPL12208.1 | WHZ30390.1 | ULR92343.1 |

| ACT34874.1 | QPL12196.1 | WHZ30385.1 | ULR92225.1 |

| AUR53331.1 | ANH61879.1 | WHZ30380.1 | ULR92110.1 |

| XRL22480.1 | AEZ36054.1 | QMY22989.1 | WKF25335.1 |

| XRL22485.1 | AFA90006.1 | XQV99186.1 | WKF25331.1 |

| XRL22488.1 | AFA90003.1 | XQV99182.1 | UVI01528.1 |

| XRL22490.1 | ALR96390.1 | XQV99177.1 | APA19532.1 |

| XNJ14954.1 | AFA89998.1 | WNW65192.1 | ANV21448.1 |

| ACT34872.1 | AEZ36084.1 | WHZ30395.1 | WNT44153.1 |

| QPL12203.1 | QCT09563.1 | WFS86944.1 | WNT44151.1 |

| AUR53391.1 | AZP53700.1 | XQM63907.1 | WNT44149.1 |

| ACT34875.1 | AEZ36077.1 | QMY23001.1 | WNT44148.1 |

| APG57100.1 | ADZ96697.1 | AYW17105.1 | XRL28496.1 |

| XNJ14957.1 | ADH10205.1 | XLZ37515.1 | ULR92030.1 |

| XNJ14961.1 | AEZ36071.1 | XLT98263.1 | WKF25334.1 |

| APG57082.1 | UVW56757.1 | WQE73161.1 | UVI01743.1 |

| APC94011.1 | AVO00786.1 | WJQ15874.1 | WRV65845.1 |

| AZP53670.1 | AHJ81381.1 | XFZ89163.1 | UVI01614.1 |

| AZP53677.1 | AYN07325.1 | UUG08308.1 | WEW52982.1 |

| ANZ52446.1 | XYO65859.1 | WPO56664.1 | UNO37669.1 |

| AGT03836.1 | QLB45620.1 | UXC94516.1 | QLI42824.1 |

| ADZ96704.1 | AEZ36055.1 | URN67694.1 | AUO29792.1 |

| CAB69409.1 | AEZ36061.1 | UDE32122.1 | ANV21576.1 |

| Name | Sequence (5′-3′) | Tm (°C) | Product Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IFN-γ | Forward: GTAGCTGACGGTGGACCTAT | 56 | 247 |

| Reverse: TTCTCAAGTCGTTCATCGGGA | |||

| IL-2 | Forward: ACCAACTGAGACCCAGGAGTG | 56 | 172 |

| Reverse: TCCGGTGTGATTTAGACCCGT | |||

| IL-4 | Forward: TGTAGGGGACCTGAGATGTGA | 56 | 197 |

| Reverse: AGGTTGTTATCTCCACCAGGACA | |||

| IL-1β | Forward: GGTCAACATCGCCACCTACA | 56 | 85 |

| Reverse: CATACGAGATGGAAACCAGCAA | |||

| IL-6 | Forward: CGGCTTCGACGAGGAGAAA | 56 | 228 |

| Reverse: TTCAGATTGGCGAGGAGGGA | |||

| TNF-α | Forward: TGTGGGGCGTGCAGTG | 56 | 194 |

| Reverse: ATGAAGGTGGTGCAGATGGG | |||

| MyD88 | Forward: CTGGCATCTTCTGAGTAGT | 60 | 76 |

| Reverse: TTCCTTATAGTTCTGGCTTCT | |||

| NF-κB | Forward: CCACAACACAATGCGCTCTG | 64 | 112 |

| Reverse: AACTCAGCGGCGTCGATG | |||

| β-actin | Forward: GCCGAGAGAGAAATTGTGCG | 56 | 211 |

| Reverse: TACCACAGGACTCCATACCCAA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ji, J.; Dong, X.; Liu, X.; Ding, M.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Lei, B.; Yuan, W.; Zhao, K. Designing a Novel Multi-Epitope Trivalent Vaccine Against NDV, AIV and FAdV-4 Based on Immunoinformatics Approaches. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2744. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122744

Ji J, Dong X, Liu X, Ding M, Lin Y, Zhang Y, Zhang W, Lei B, Yuan W, Zhao K. Designing a Novel Multi-Epitope Trivalent Vaccine Against NDV, AIV and FAdV-4 Based on Immunoinformatics Approaches. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2744. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122744

Chicago/Turabian StyleJi, Jiashuang, Xiaofeng Dong, Xiangyi Liu, Mengchun Ding, Yating Lin, Yunhang Zhang, Wuchao Zhang, Baishi Lei, Wanzhe Yuan, and Kuan Zhao. 2025. "Designing a Novel Multi-Epitope Trivalent Vaccine Against NDV, AIV and FAdV-4 Based on Immunoinformatics Approaches" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2744. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122744

APA StyleJi, J., Dong, X., Liu, X., Ding, M., Lin, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhang, W., Lei, B., Yuan, W., & Zhao, K. (2025). Designing a Novel Multi-Epitope Trivalent Vaccine Against NDV, AIV and FAdV-4 Based on Immunoinformatics Approaches. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2744. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122744