Changes in the Structure of Strawberry Leaf Surface Bacterial and Fungal Communities by Plant Biostimulants

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strawberry Cultivation and Sample Collection

2.2. DNA Extraction, Sequencing, and Data Processing

2.3. Isolation of Treatment-Specific Bacteria from Strawberry Leaves

2.4. Identification of Bacterial Isolates

2.5. Growth Assay of Isolates with Sugar-Enhancing Biostimulant

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effects of the Plant Biostimulant on Fruit Sugar Content and Relative Abundance of Microbial Taxa

3.2. Microbial Diversity in Strawberry Leaves After Treatment

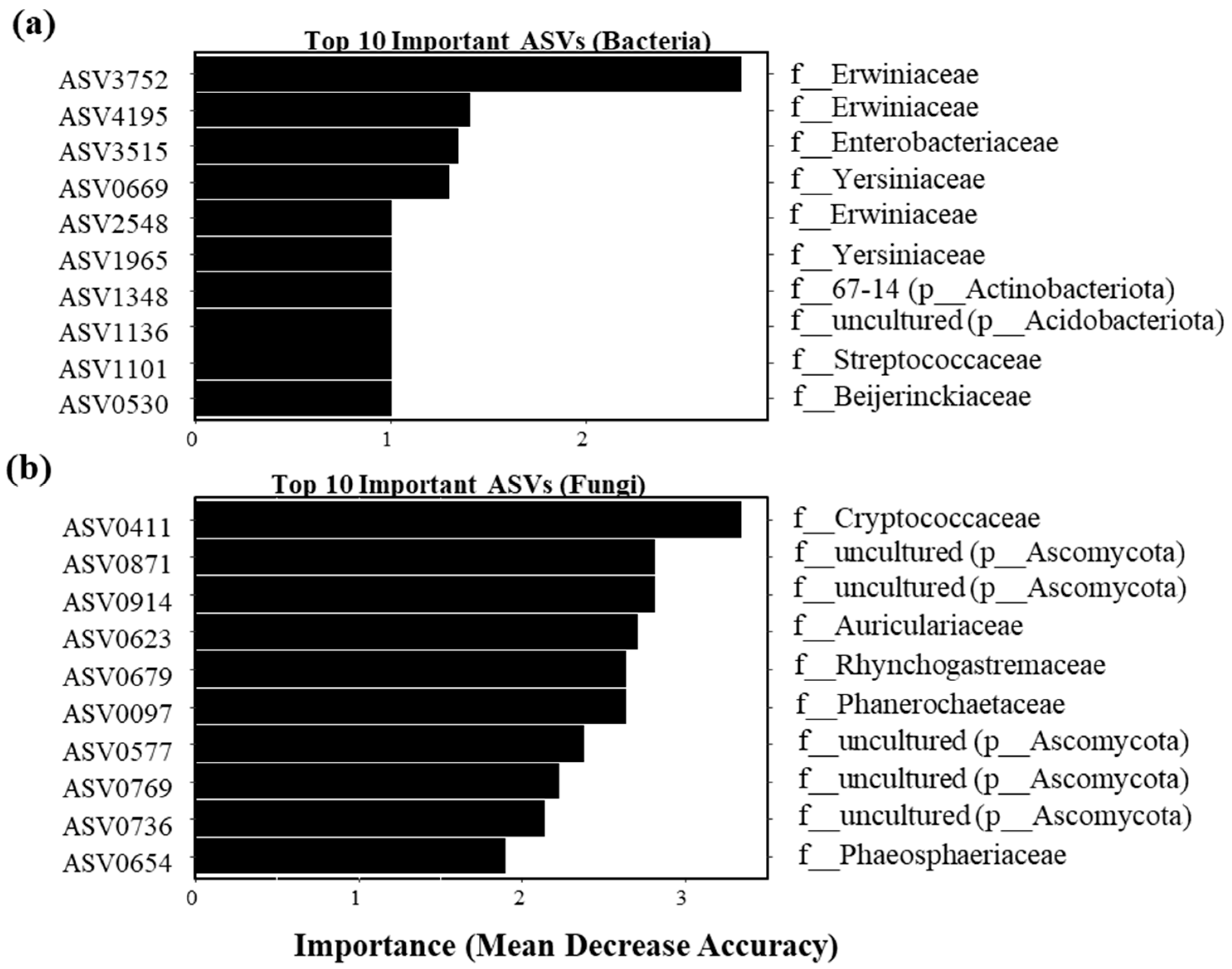

3.3. Random Forest Analysis of Key ASVs

3.4. Functional Features of the Phyllosphere Microbiota

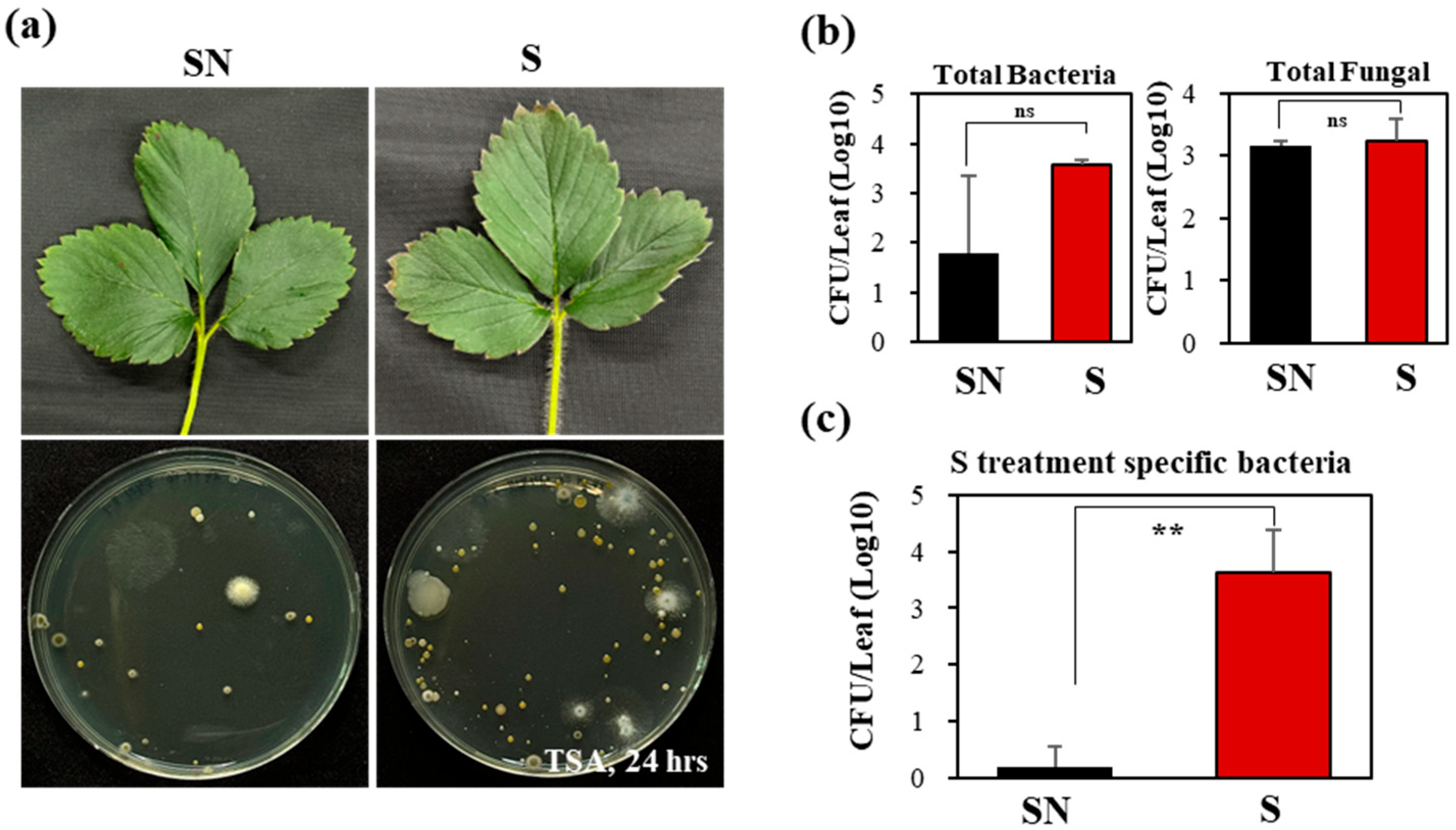

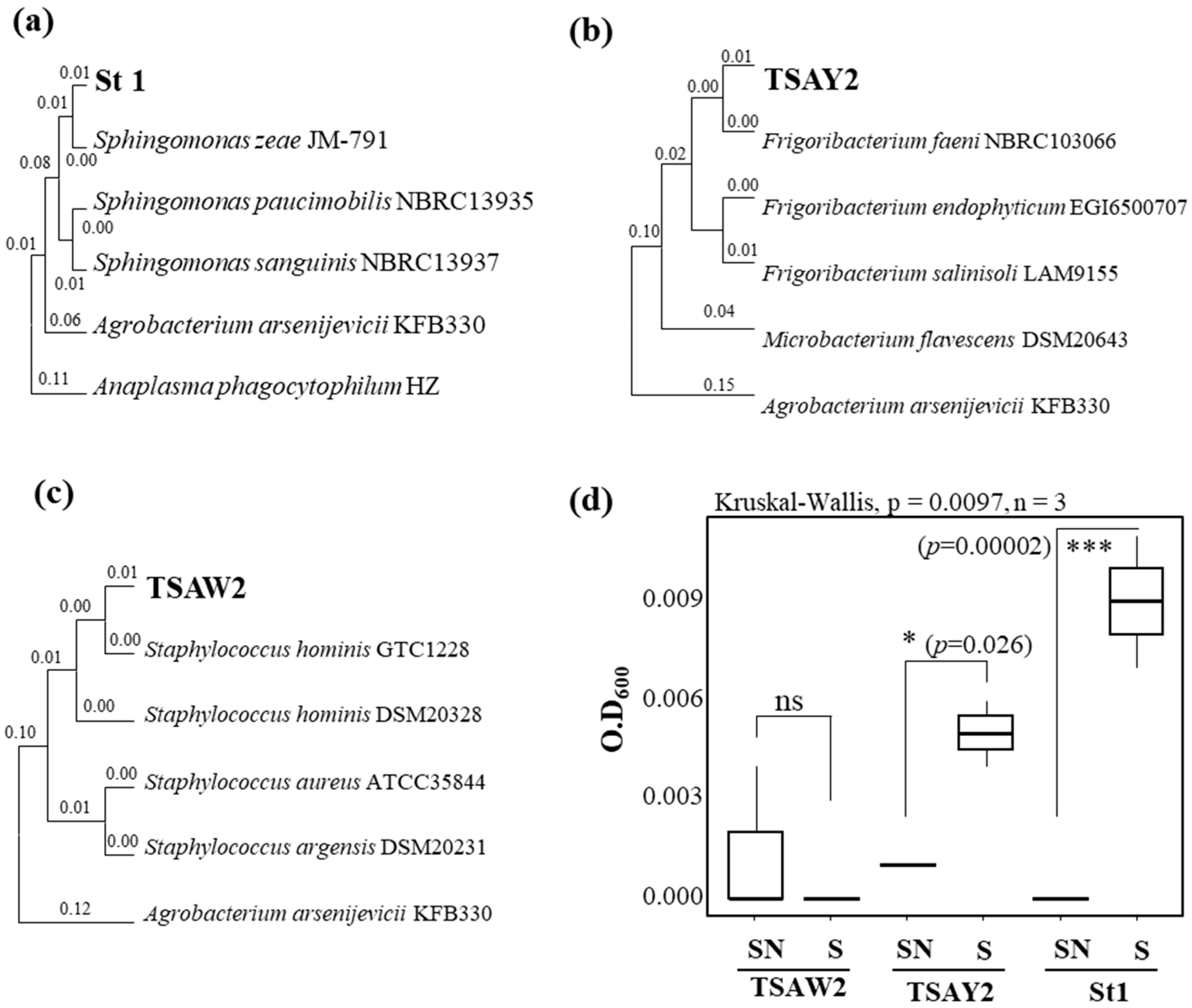

3.5. Cultivation-Based Analysis of Leaf Microbes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zahedifar, M.; Moosavi, A.A.; Gavili, E.; Ershadi, A. Tomato fruit quality and nutrient dynamics under water deficit conditions: The influence of an organic fertilizer. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0310916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rejman, K.; Górska-Warsewicz, H.; Kaczorowska, J.; Laskowski, W. Nutritional Significance of Fruit and Fruit Products in the Average Polish Diet. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, M.; Fan, Z.; Lee, S.; Whitaker, V.M. Strawberry breeding for improved flavor. Crop Sci. 2023, 63, 1949–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, V. Duchesne and his work. In The Strawberry: History, Breeding and Physiology; Darrow, G.M., Ed.; Holt Rinehart & Winston: Austin, TX, USA, 1966; pp. 40–72. [Google Scholar]

- Liston, A.; Cronn, R.; Ashman, T.L. Fragaria: A genus with deep historical roots and ripe for evolutionary and ecological insights. Am. J. Bot. 2014, 101, 1686–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. UN Food and Agricultural Organization Statistical Databases. 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL/metadata (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Bhat, R.; Geppert, J.; Funken, E.; Stamminger, R. Consumers perceptions and preference for strawberries—A case study from Germany. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2015, 15, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquhoun, T.A.; Levin, L.A.; Moskowitz, H.R.; Whitaker, V.M.; Clark, D.G.; Folta, K.M. Framing the perfect strawberry: An exercise in consumer-assisted selection of fruit crops. J. Berry Res. 2012, 2, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Hasing, T.; Johnson, T.S.; Garner, D.M.; Schwieterman, M.L.; Barbey, C.R.; Colquhoun, T.A.; Sims, C.A.; Resende, M.F.R.; Whitaker, V.M. Strawberry sweetness and consumer preference are enhanced by specific volatile compounds. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 66, Erratum in Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 224. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41438-021-00664-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampieri, F.; Tulipani, S.; Alvarez-Suarez, J.M.; Quiles, J.L.; Mezzetti, B.; Battino, M. The strawberry: Composition, nutritional quality, and impact on human health. Nutrition 2012, 28, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwieterman, M.L.; Colquhoun, T.A.; Jaworski, E.A.; Bartoshuk, L.M.; Gilbert, J.L.; Tieman, D.M.; Odabasi, A.Z.; Moskowitz, H.R.; Folta, K.M.; Klee, H.J.; et al. Strawberry flavor: Diverse chemical compositions, a seasonal influence, and effects on sensory perception. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallarino, J.G.; Pott, D.M.; Cruz-Rus, E.; Miranda, L.; Medina-Minguez, J.J.; Valpuesta, V.; Fernie, A.R.; Sánchez-Sevilla, J.F.; Osorio, S.; Amaya, I. Identification of quantitative trait loci and candidate genes for primary metabolite content in strawberry fruit. Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enomoto, H.; Sato, K.; Miyamoto, K.; Ohtsuka, A.; Yamane, H. Distribution analysis of anthocyanins, sugars, and organic acids in strawberry fruits using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-imaging mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 4958–4965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Yu, O.; Tang, J.; Gu, X.; Wan, X.; Fang, C. Metabolic profiling of strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) during fruit development and maturation. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 1103–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Bhardwaj, S.; Rahman, M.A.; García-Caparrós, P.; Habib, M.; Saeed, F.; Charagh, S.; Foyer, C.H.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Varshney, R.K. Trehalose: A sugar molecule involved in temperature stress management in plants. Crop. J. 2024, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, L.; Jiang, L.; Wills, R.B.H.; Golding, J.B.; Huo, Y.; Yang, H.; Li, Y. Chitosan oligosaccharides induced chilling resistance in cucumber fruit and associated stimulation of antioxidant and HSP gene expression. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 264, 109187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tian, R.; Wan, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, H. Combined analysis of metabolomics and transcriptomics reveals the effects of sugar treatment on postharvest strawberry fruit quality. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olimi, E.; Kusstatscher, P.; Wicaksono, W.A.; Abdelfattah, A.; Cernava, T.; Berg, G. Insights into the microbiome assembly during different growth stages and storage of strawberry plants. Environ. Microbiome 2022, 17, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.; Batista, B.D.; Bazany, K.E.; Singh, B.K. Plant–microbiome interactions under a changing world: Responses, consequences and perspectives. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 1951–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenkoornhuyse, P.; Quaiser, A.; Duhamel, M.; Le, V.A.; Dufresne, A. The importance of the microbiome of the plant holobiont. New Phytol. 2015, 206, 1196–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, X.; Chen, T.; Wang, W.; Liu, G.; Zhang, W.; Li, S.; Wang, M.; Zhao, C.; Zhou, H.; et al. Plant Phenotypic Traits Eventually Shape Its Microbiota: A Common Garden Test. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnetj 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. Dada2: High-resolution sample inference from illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, P.; Parfrey, L.W.; Yarza, P.; Gerken, J.; Pruesse, E.; Quast, C.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Ludwig, W.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA and “All-species Living Tree Project (LTP)” taxonomic frameworks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louca, S.; Parfrey, L.W.; Doebeli, M. Decoupling function and taxonomy in the global ocean microbiome. Science 2016, 353, 1272–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, C.; Innerebner, G.; Zingg, J.; Guder, J.; Vorholt, J.A. Forward genetic in planta screen for identification of plant-protective traits of Sphingomonas sp. strain Fr1 against Pseudomonas syringae DC3000. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 5529–5535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, L.; Waqas, M.; Kang, S.-M.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Hussain, J.; Al-Rawahi, A.; Al-Khiziri, S.; Ullah, I.; Ali, L.; Jung, H.-Y.; et al. Bacterial endophyte Sphingomonas sp. LK11 produces gibberellins and IAA and promotes tomato plant growth. J. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Sun, Y.; Xie, X.; Kim, M.S.; Dowd, S.E.; Pare, P.W. A soil bacterium regulates plant acquisition of iron via deficiency-inducible mechanisms. Plant J. 2009, 58, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.H.; Ham, S.Y.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, I.-S.; Lee, E.Y. Application of sodium polyacrylate and plant growth-promoting bacterium, Micrococcaceae HW-2, on the growth of plants cultivated in the rooftop. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2016, 113, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazoyon, C.; Hirel, B.; Pecourt, A.; Catterou, M.; Gutierrez, L.; Sarazin, V.; Dubois, F.; Duclercq, J. Sphingomonas sediminicola is an endosymbiotic bacterium able to induce the formation of root nodules in Pea (Pisum sativum L.) and to enhance plant biomass production. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.Y.; Shin, H.; Yu, J.; Kong, H.G. Changes in the Structure of Strawberry Leaf Surface Bacterial and Fungal Communities by Plant Biostimulants. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2461. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112461

Lee JY, Shin H, Yu J, Kong HG. Changes in the Structure of Strawberry Leaf Surface Bacterial and Fungal Communities by Plant Biostimulants. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(11):2461. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112461

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Ji Yoon, Hyeran Shin, Juhyun Yu, and Hyun Gi Kong. 2025. "Changes in the Structure of Strawberry Leaf Surface Bacterial and Fungal Communities by Plant Biostimulants" Microorganisms 13, no. 11: 2461. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112461

APA StyleLee, J. Y., Shin, H., Yu, J., & Kong, H. G. (2025). Changes in the Structure of Strawberry Leaf Surface Bacterial and Fungal Communities by Plant Biostimulants. Microorganisms, 13(11), 2461. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112461