Yeast-Based Screening of Anti-Viral Molecules

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Why Target Viral Enzymes?

3. Assays for Screening Anti-Viral Molecules

3.1. In Vitro Assay for Screening of Anti-Viral Molecules

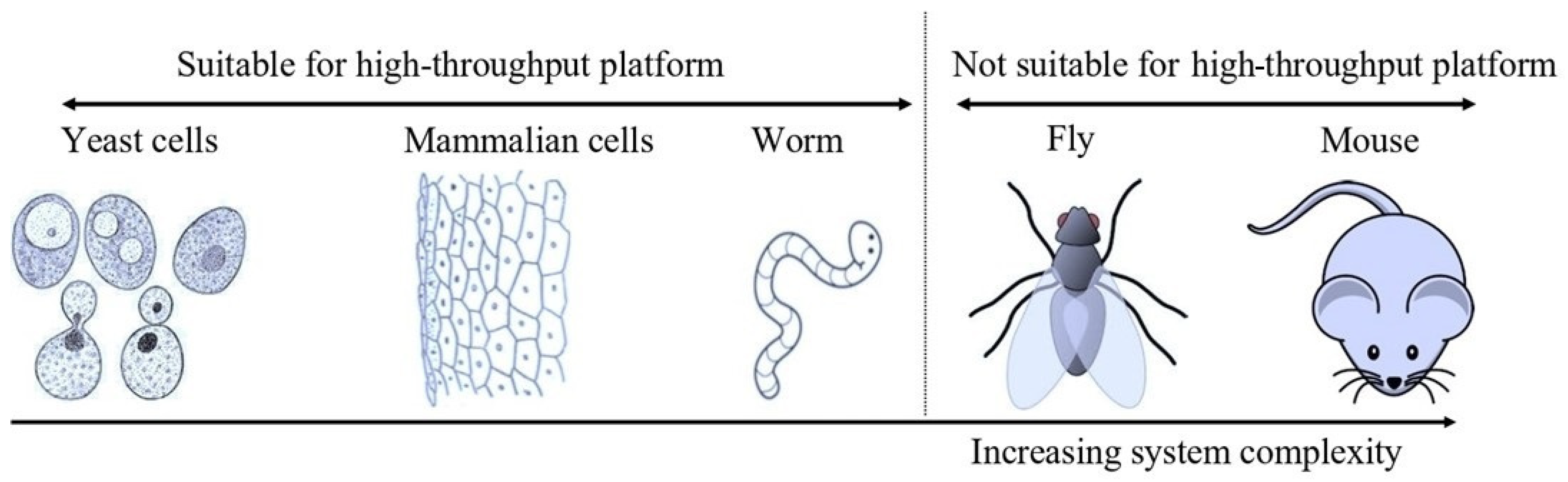

3.2. In Vivo Assay for Screening of Anti-Viral Molecules

4. Yeast as a Screening Model

5. Screening of Viral Protease Inhibitors Using Yeast-Based Platforms

6. The Bottleneck of In Vivo Assays for Viral Protease Inhibitors

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roingeard, P. Viral detection by electron microscopy: Past, present and future. Biol. Cell. 2008, 100, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois-Dalcq, M.; Holmes, K.V.; Rentier, B.; Kingsbury, D.W. Assembly of Enveloped RNA Viruses; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kaján, G.L.; Doszpoly, A.; Tarján, Z.L.; Vidovszky, M.Z.; Papp, T. Virus–Host Coevolution with a Focus on Animal and Human DNA Viruses. J. Mol. Evol. 2020, 88, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koonin, E.V.; Senkevich, T.G.; Dolja, V.V. The ancient Virus World and evolution of cells. Biol. Direct 2006, 1, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, C.M.; Menon, S.; Eilers, B.J.; Bothner, B.; Khayat, R.; Douglas, T.; Young, M.J. Structural and functional studies of archaeal viruses. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 12599–12603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, C.Y.; Miller, S.A. Clinical metagenomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjuán, R.; Nebot, M.R.; Chirico, N.; Mansky, L.M.; Belshaw, R. Viral Mutation Rates. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 9733–9748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, D. Viruses: A Very Short Introduction; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Breitbart, M.; Rohwer, F. Here a virus, there a virus, everywhere the same virus? Trends Microbiol. 2005, 13, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Bushman, F.D. The human virome: Assembly, composition and host interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 514–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, V.; Petty, A.J.; Atwater, A.R.; Wolfe, S.A.; MacLeod, A.S. Skin Viral Infections: Host Antiviral Innate Immunity and Viral Immune Evasion. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 593901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlicka, K.; Barnes, E.; Culver, E.L. Prevention of infection caused by immunosuppressive drugs in gastroenterology. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2013, 4, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugizov, S.; Webster-Cyriaque, J.; Syrianen, S.; Chattopadyay, A.; Sroussi, H.; Zhang, L.; Kaushal, A. Mechanisms of Viral Infections Associated with HIV: Workshop 2B. Adv. Dent. Res. 2011, 23, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, A.D.; Dowdle, J.A.; Bozzacco, L.; McMichael, T.M.; Gelais, C.S.; Panfil, A.R.; Sun, Y.; Schlesinger, L.S.; Anderson, M.Z.; Green, P.L.; et al. Human Genetic Determinants of Viral Diseases. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2017, 51, 241–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singanayagam, A.; Hakki, S.; Dunning, J.; Madon, K.J.; Crone, M.A.; Koycheva, A.; Derqui-Fernandez, N.; Barnett, J.L.; Whitfield, M.G.; Varro, R.; et al. Community transmission and viral load kinetics of the SARS-CoV-2 delta (B.1.617.2) variant in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals in the UK: A prospective, longitudinal, cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babkin, I.V.; Babkina, I.N. The Origin of the Variola Virus. Viruses 2015, 7, 1100–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.R.; Streicker, D.G.; Schnell, M.J. The spread and evolution of rabies virus: Conquering new frontiers. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damas, J.; Hughes, G.M.; Keough, K.C.; Painter, C.A.; Persky, N.S.; Corbo, M.; Hiller, M.; Koepfli, K.-P.; Pfenning, A.R.; Zhao, H.; et al. Broad host range of SARS-CoV-2 predicted by comparative and structural analysis of ACE2 in vertebrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 22311–22322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sit, T.H.C.; Brackman, C.J.; Ip, S.M.; Tam, K.W.S.; Law, P.Y.T.; To, E.M.W.; Yu, V.Y.T.; Sims, L.D.; Tsang, D.N.C.; Chu, D.K.W.; et al. Infection of dogs with SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2020, 586, 776–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosco-Lauth, A.M.; Hartwig, A.E.; Porter, S.M.; Gordy, P.W.; Nehring, M.; Byas, A.D.; VandeWoude, S.; Ragan, I.K.; Maison, R.M.; Bowen, R.A. Experimental infection of domestic dogs and cats with SARS-CoV-2: Pathogenesis, transmission, and response to reexposure in cats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 26382–26388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, J.S.; Mistry, B.; Haslam, S.M.; Barclay, W.S. Host and viral determinants of influenza A virus species specificity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balique, F.; Lecoq, H.; Raoult, D.; Colson, P. Can Plant Viruses Cross the Kingdom Border and Be Pathogenic to Humans? Viruses 2015, 7, 2074–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koonin, E.V.; Dolja, V.V.; Krupovic, M. Origins and evolution of viruses of eukaryotes: The ultimate modularity. Virology 2015, 479–480, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NCEZID: Deadly Infections. CDC. 2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/what-we-do/our-topics/deadly-unexplained-diseases.html (accessed on 4 September 2022).

- Paget, J.; Spreeuwenberg, P.; Charu, V.; Taylor, R.J.; Iuliano, A.D.; Bresee, J.; Simonsen, L.; Viboud, C.; Global Seasonal Influenza-Associated Mortality Collaborator Network and GLaMOR Collaborating Teams. Global mortality associated with seasonal influenza epidemics: New burden estimates and predictors from the GLaMOR Project. J. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 020421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehndiratta, M.M.; Mehndiratta, P.; Pande, R. Poliomyelitis: Historical facts, epidemiology, and current challenges in eradication. Neurohospitalist 2014, 4, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What is Polio? CDC. 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/polio/what-is-polio/index.htm (accessed on 4 September 2022).

- Halawa, S.; Pullamsetti, S.S.; Bangham, C.R.M.; Stenmark, K.R.; Dorfmüller, P.; Frid, M.G.; Butrous, G.; Morrell, N.W.; Perez, V.A.d.J.; Stuart, D.I.; et al. Potential long-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the pulmonary vasculature: A global perspective. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2022, 19, 314–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Ramirez, D.C.; Normand, K.; Zhaoyun, Y.; Torres-Castro, R. Long-Term Impact of COVID-19: A Systematic Review of the Literature and Meta-Analysis. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Leon, S.; Wegman-Ostrosky, T.; Perelman, C.; Sepulveda, R.; Rebolledo, P.A.; Cuapio, A.; Villapol, S. More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthy Habits to Help Protect Against Flu. CDC. 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/actions-prevent-flu.htm (accessed on 4 September 2022).

- MAYO CLINIC. Germs: Understand and Protect against Bacteria, Viruses and Infections. Mayo Clinic. 2022. Available online: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/infectious-diseases/in-depth/germs/art-20045289 (accessed on 4 September 2022).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How to Protect Yourself and Others. 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html (accessed on 4 September 2022).

- Fenner, F. Global Eradication of Smallpox. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1982, 4, 916–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norrby, E.; Uhnoo, I.; Brytting, M.; Zakikhany, K.; Lepp, T.; Olin, P. Polio close to eradication. Lakartidningen 2017, 114, EPDT. [Google Scholar]

- Tregoning, J.S.; Brown, E.S.; Cheeseman, H.M.; Flight, K.E.; Higham, S.L.; Lemm, N.-M.; Pierce, B.F.; Stirling, D.C.; Wang, Z.; Pollock, K.M. Vaccines for COVID-19. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2020, 202, 162–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.P.; Gupta, V. COVID-19 Vaccine: A comprehensive status report. Virus Res. 2020, 288, 198114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, E. The race for coronavirus vaccines: A graphical guide. Nature 2020, 580, 576–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Srivastava, V.; Baindara, P.; Ahmad, A. Thermostable vaccines: An innovative concept in vaccine development. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2022, 21, 811–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R. Investigating the long-term stability of protein immunogen(s) for whole recombinant yeast-based vaccines. FEMS Yeast Res. 2018, 18, foy071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Kharbikar, B.N. Lyophilized yeast powder for adjuvant free thermostable vaccine delivery. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 3131–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kumar, P. Yeast-based vaccines: New perspective in vaccine development and application. FEMS Yeast Res. 2019, 19, foz007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, V.; Nand, K.N.; Ahmad, A.; Kumar, R. Yeast-Based Virus-like Particles as an Emerging Platform for Vaccine Development and Delivery. Vaccines 2023, 11, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Srivastava, V. Application of anti-fungal vaccines as a tool against emerging anti-fungal resistance. Front. Fungal Biol. 2023, 4, 1241539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korber, B.; Fischer, W.M.; Gnanakaran, S.; Yoon, H.; Theiler, J.; Abfalterer, W.; Hengartner, N.; Giorgi, E.E.; Bhattacharya, T.; Foley, B.; et al. Tracking Changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: Evidence that D614G Increases Infectivity of the COVID-19 Virus. Cell 2020, 182, 812–827.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalkanen, P.; Kolehmainen, P.; Häkkinen, H.K.; Huttunen, M.; Tähtinen, P.A.; Lundberg, R.; Maljanen, S.; Reinholm, A.; Tauriainen, S.; Pakkanen, S.H.; et al. COVID-19 mRNA vaccine induced antibody responses against three SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Liu, B.; Li, F. Cryo-EM structure of a SARS-CoV-2 omicron spike protein ectodomain. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saville, J.W.; Mannar, D.; Zhu, X.; Srivastava, S.S.; Berezuk, A.M.; Demers, J.-P.; Zhou, S.; Tuttle, K.S.; Sekirov, I.; Kim, A.; et al. Structural and biochemical rationale for enhanced spike protein fitness in delta and kappa SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magen, O.; Waxman, J.G.; Makov-Assif, M.; Vered, R.; Dicker, D.; Hernán, M.A.; Lipsitch, M.; Reis, B.Y.; Balicer, R.D.; Dagan, N. Fourth Dose of BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine in a Nationwide Setting. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1603–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hippisley-Cox, J.; Patone, M.; Mei, X.W.; Saatci, D.; Dixon, S.; Khunti, K.; Zaccardi, F.; Watkinson, P.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Doidge, J.; et al. Risk of thrombocytopenia and thromboembolism after COVID-19 vaccination and SARS-CoV-2 positive testing: Self-controlled case series study. BMJ 2021, 374, n1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamey, G.; Garcia, P.; Hassan, F.; Mao, W.; McDade, K.K.; Pai, M.; Saha, S.; Schellekens, P.; Taylor, A.; Udayakumar, K. It is not too late to achieve global COVID-19 vaccine equity. BMJ 2022, 376, e070650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsagkaris, C.; Laubscher, L.; Papadakis, M.; Vladychuk, V.; Matiashova, L. Immunization in state of siege: The importance of thermostable vaccines for Ukraine and other war-torn countries and territories. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2022, 21, 1007–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Srivastava, V.; Baindara, P.; Ahmad, A. Response to: “immunization in state of siege: The importance of thermostable vaccines for Ukraine and other war-torn countries and territories”. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2022, 21, 1009–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Srivastava, V.; Nand, K.N. The Two Sides of the COVID-19 Pandemic. COVID 2023, 3, 1746–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, D.S.; Scott, R.M.; Johnson, D.E.; Nisalak, A. A Prospective Study of Dengue Infections in Bangkok. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1988, 38, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliks, S.C.; Nimmanitya, S.; Nisalak, A.; Burke, D.S. Evidence That Maternal Dengue Antibodies Are Important in the Development of Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever in Infants. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1988, 38, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng’uni, T.; Chasara, C.; Ndhlovu, Z.M. Major Scientific Hurdles in HIV Vaccine Development: Historical Perspective and Future Directions. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 590780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monto, A.S. Vaccines and Antiviral Drugs in Pandemic Preparedness. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardi, N.; Weissman, D. Development of vaccines and antivirals for combating viral pandemics. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 4, 1128–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.T.; Yang, Q.; Gribenko, A.; Perrin, B.S.; Zhu, Y.; Cardin, R.; Liberator, P.A.; Anderson, A.S.; Hao, L. Genetic Surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 M pro Reveals High Sequence and Structural Conservation Prior to the Introduction of Protease Inhibitor Paxlovid. mBio 2022, 13, e0086922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo-Filho, C.C.; Bobrowski, T.; Martin, H.J.; Sessions, Z.; Popov, K.I.; Moorman, N.J.; Baric, R.S.; Muratov, E.N.; Tropsha, A. Conserved coronavirus proteins as targets of broad-spectrum antivirals. Anti-Viral Res. 2022, 204, 105360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craigie, R. The molecular biology of HIV integrase. Future Virol. 2012, 7, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delelis, O.; Carayon, K.; Saïb, A.; Deprez, E.; Mouscadet, J.-F. Integrase and integration: Biochemical activities of HIV-1 integrase. Retrovirology 2008, 5, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aftab, S.O.; Ghouri, M.Z.; Masood, M.U.; Haider, Z.; Khan, Z.; Ahmad, A.; Munawar, N. Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase as a potential therapeutic drug target using a computational approach. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Omran, K.; Khan, E.; Ali, N.; Bilal, M. Estimation of COVID-19 generated medical waste in the Kingdom of Bahrain. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 801, 149642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phadke, R.; Costa, A.C.d.S.; Dapke, K.; Ghosh, S.; Ahmad, S.; Tsagkaris, C.; Raiya, S.; Maheswari, M.S.; Essar, M.Y.; Ahmad, S. Eco-friendly vaccination: Tackling an unforeseen adverse effect. J. Clim. Chang. Health 2021, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Islam, N.; Billah, M.; Sarker, A. COVID-19 pandemic and healthcare solid waste management strategy—A mini-review. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 778, 146220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, H.; Yamaya, M. A Synthetic Serine Protease Inhibitor, Nafamostat Mesilate, Is a Drug Potentially Applicable to the Treatment of Ebola Virus Disease. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2015, 237, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.Z.; Yasuo, N.; Sekijima, M. Screening for Inhibitors of Main Protease in SARS-CoV-2: In Silico and In Vitro Approach Avoiding Peptidyl Secondary Amides. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cihlova, B.; Huskova, A.; Böserle, J.; Nencka, R.; Boura, E.; Silhan, J. High-Throughput Fluorescent Assay for Inhibitor Screening of Proteases from RNA Viruses. Molecules 2021, 26, 3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, C.; Gallo, G.; Campos, C.B.; Hardy, L.; Würtele, M. Biochemical screening for SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graudejus, O.; Wong, R.D.P.; Varghese, N.; Wagner, S.; Morrison, B. Bridging the gap between in vivo and in vitro research: Reproducing in vitro the mechanical and electrical environment of cells in vivo. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Hu, Y.; Townsend, J.A.; Lagarias, P.I.; Marty, M.T.; Kolocouris, A.; Wang, J. Ebselen, Disulfiram, Carmofur, PX-12, Tideglusib, and Shikonin Are Nonspecific Promiscuous SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Inhibitors. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2020, 3, 1265–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Sacco, M.D.; Xia, Z.; Lambrinidis, G.; Townsend, J.A.; Hu, Y.; Meng, X.; Szeto, T.; Ba, M.; Zhang, X.; et al. Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 Papain-like Protease Inhibitors through a Combination of High-Throughput Screening and a FlipGFP-Based Reporter Assay. ACS Central Sci. 2021, 7, 1245–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, C.; Schildknecht, S. In Vitro Research Reproducibility: Keeping Up High Standards. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.; Davis-Gardner, M.E.; Garcia-Ordonez, R.D.; Nguyen, T.-T.; Hull, M.; Chen, E.; Yu, X.; Bannister, T.D.; Baillargeon, P.; Scampavia, L.; et al. High throughput screening for drugs that inhibit 3C-like protease in SARS-CoV-2. SLAS Discov. 2023, 28, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, D.R.; Allerton, C.M.N.; Anderson, A.S.; Aschenbrenner, L.; Avery, M.; Berritt, S.; Boras, B.; Cardin, R.D.; Carlo, A.; Coffman, K.J.; et al. An oral SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor clinical candidate for the treatment of COVID-19. Science 2021, 374, 1586–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Gao, W.; Hu, H.; Zhou, S. Why 90% of clinical drug development fails and how to improve it? Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 3049–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, J.R.; Diboun, I.; Dessailly, B.H.; Lees, J.G.; Orengo, C.A. Transient Protein-Protein Interactions: Structural, Functional, and Network Properties. Structure 2010, 18, 1233–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavesley, S.J.; Rich, T.C. Overcoming limitations of FRET measurements. Cytom. Part A 2016, 89, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nierode, G.; Kwon, P.S.; Dordick, J.S.; Kwon, S.-J. Cell-Based Assay Design for High-Content Screening of Drug Candidates. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 26, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovida, C.; Hartung, T. Re-evaluation of animal numbers and costs for in vivo tests to accomplish REACH legislation requirements for chemicals—A report by the transatlantic think tank for toxicology (t(4)). ALTEX 2009, 26, 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwell, L.H.; Szankasi, P.; Roberts, C.J.; Murray, A.W.; Friend, S.H. Integrating Genetic Approaches into the Discovery of Anticancer Drugs. Science 1997, 278, 1064–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, T.A.; Park, D.; Kann, M.G. A protein domain-centric approach for the comparative analysis of human and yeast phenotypically relevant mutations. BMC Genom. 2013, 14 (Suppl. S3), S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.Y. Yeast for virus research. Microb. Cell 2017, 4, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galao, R.P.; Scheller, N.; Alves-Rodrigues, I.; Breinig, T.; Meyerhans, A.; Díez, J. Saccharomyces cerevisiae: A versatile eukaryotic system in virology. Microb. Cell Factories 2007, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glingston, R.S.; Yadav, J.; Rajpoot, J.; Joshi, N.; Nagotu, S. Contribution of yeast models to virus research. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 4855–4878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaever, G.; Nislow, C. The Yeast Deletion Collection: A Decade of Functional Genomics. Genetics 2014, 197, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubreuil, B.; Sass, E.; Nadav, Y.; Heidenreich, M.; Georgeson, J.M.; Weill, U.; Duan, Y.; Meurer, M.; Schuldiner, M.; Knop, M.; et al. YeastRGB: Comparing the abundance and localization of yeast proteins across cells and libraries. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D1245–D1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duina, A.A.; Miller, M.E.; Keeney, J.B. Budding Yeast for Budding Geneticists: A Primer on the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Model System. Genetics 2014, 197, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longtine, M.S.; McKenzie, A., 3rd; Demarini, D.J.; Shah, N.G.; Wach, A.; Brachat, A.; Philippsen, P.; Pringle, J.R. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 1998, 14, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanov, A.; Nitiss, K.C.; Neale, G.; Nitiss, J.L. Enhancing Drug Accumulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by Repression of Pleiotropic Drug Resistance Genes with Chimeric Transcription Repressors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008, 74, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalkova-Papajova, D.; Obernauerova, M.; Subik, J. Role of the PDR Gene Network in Yeast Susceptibility to the Antifungal Antibiotic Mucidin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 418–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, F.; Wen, Y.; Guo, X. CRISPR/Cas9 for genome editing: Progress, implications and challenges. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, R40–R46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doke, S.K.; Dhawale, S.C. Alternatives to animal testing: A review. Saudi Pharm. J. 2015, 23, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressey, D. UK ‘absolutely committed’ to reducing animal use in research. Nature 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. EPA New Approach Methods: Efforts to Reduce Use of Vertebrate Animals in Chemical Testing. EPA. 2022. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/research/epa-new-approach-methods-efforts-reduce-use-vertebrate-animals-chemical-testing (accessed on 4 September 2022).

- Bender, A.; Cortés-Ciriano, I. Artificial intelligence in drug discovery: What is realistic, what are illusions? Part 1: Ways to make an impact, and why we are not there yet. Drug Discov. Today 2021, 26, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R.; Lal, S.K. A yeast assay for high throughput screening of natural anti-viral agents. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 301, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottier, V.; Barberis, A.; Lüthi, U. Novel Yeast Cell-Based Assay to Screen for Inhibitors of Human Cytomegalovirus Protease in a High-Throughput Format. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravaux, I.; Perrin-East, C.; Attias, C.; Cottalorda, J.; Durant, J.; Dellamonica, P.; Gluschankof, P.; Stein, A.; Tamalet, C. Yeast cells as a tool for analysis of HIV-1 protease susceptibility to protease inhibitors, a comparative study. J. Virol. Methods 2014, 195, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benko, Z.; Elder, R.T.; Li, G.; Liang, D.; Zhao, R.Y. Fission yeast as a HTS platform for molecular probes of HIV-1 Vpr-induced cell death. Int. J. High Throughput Screen. 2010, 1, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Frieman, M.; Basu, D.; Matthews, K.; Taylor, J.; Jones, G.; Pickles, R.; Baric, R.; Engel, D.A. Yeast Based Small Molecule Screen for Inhibitors of SARS-CoV. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alalam, H.; Sigurdardóttir, S.; Bourgard, C.; Tiukova, I.; King, R.D.; Grøtli, M.; Sunnerhagen, P. A Genetic Trap in Yeast for Inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease. mSystems 2021, 6, e0108721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; Tao, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, A.; Yang, Z.; Wang, K.; Shi, L.; Chen, Y.; Guo, D. Yeast-based assays for the high-throughput screening of inhibitors of coronavirus RNA cap guanine-N7-methyltransferase. Antivir. Res. 2014, 104, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakauskaitė, R.; Liao, P.-Y.; Rhodin, M.H.J.; Lee, K.; Dinman, J.D. A rapid, inexpensive yeast-based dual-fluorescence assay of programmed—1 ribosomal frameshifting for high-throughput screening. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, J.M.; Samant, N.; Schneider-Nachum, G.; Barkan, D.T.; Yilmaz, N.K.; Schiffer, C.A.; Moquin, S.A.; Dovala, D.; Bolon, D.N.A. Comprehensive fitness landscape of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro reveals insights into viral resistance mechanisms. eLife 2022, 11, e77433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Vernon, K.; Li, Q.; Benko, Z.; Amoroso, A.; Nasr, M.; Zhao, R.Y. Single-Agent and Fixed-Dose Combination HIV-1 Protease Inhibitor Drugs in Fission Yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe). Pathogens 2021, 10, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benko, Z.; Elder, R.T.; Li, G.; Liang, D.; Zhao, R.Y. HIV-1 Protease in the Fission Yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Benko, Z.; Liang, D.; Li, G.; Elder, R.T.; Sarkar, A.; Takayama, J.; Ghosh, A.K.; Zhao, R.Y. A fission yeast cell-based system for multidrug resistant HIV-1 proteases. Cell Biosci. 2017, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bader, G.; Enkler, L.; Araiso, Y.; Hemmerle, M.; Binko, K.; Baranowska, E.; De Craene, J.-O.; Ruer-Laventie, J.; Pieters, J.; Tribouillard-Tanvier, D.; et al. Assigning mitochondrial localization of dual localized proteins using a yeast Bi-Genomic Mitochondrial-Split-GFP. eLife 2020, 9, e56649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Yi, S.Y.; Lee, C.-S.; Kim, K.E.; Pai, H.-S.; Seol, D.-W.; Chung, B.H.; Kim, M. A Split Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein-Based Reporter in Yeast Two-Hybrid System. Protein J. 2007, 26, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothan, H.A.; Teoh, T.C. Cell-Based High-Throughput Screening Protocol for Discovering Antiviral Inhibitors Against SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease (3CLpro). Mol. Biotechnol. 2021, 63, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Tan, H.; Choza, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J. Validation and invalidation of SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors using the Flip-GFP and Protease-Glo luciferase assays. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 1636–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castelló, A.; Álvarez, E.; Carrasco, L. The Multifaceted Poliovirus 2A Protease: Regulation of Gene Expression by Picornavirus Proteases. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011, 2011, 369648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kean, K.M.; Teterina, N.; Girard, M. Cleavage specificity of the poliovirus 3C protease is not restricted to Gln-Gly at the 3C/3D junction. J. Gen. Virol. 1990, 71, 2553–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleshin, A.E.; Drag, M.; Gombosuren, N.; Wei, G.; Mikolajczyk, J.; Satterthwait, A.C.; Strongin, A.Y.; Liddington, R.C.; Salvesen, G.S. Activity, Specificity, and Probe Design for the Smallpox Virus Protease K7L. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 39470–39479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.-H.; Chuang, S.-J.; Chen, C.-C.; Cheng, S.-C.; Cheng, K.-W.; Lin, C.-H.; Sun, C.-Y.; Chou, C.-Y. Structural and functional characterization of MERS coronavirus papain-like protease. J. Biomed. Sci. 2014, 21, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumla, A.; Chan, J.F.; Azhar, E.I.; Hui, D.S.; Yuen, K.Y. Coronaviruses—Drug discovery and therapeutic options. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitsche, C.; Holloway, S.; Schirmeister, T.; Klein, C.D. Biochemistry and Medicinal Chemistry of the Dengue Virus Protease. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11348–11381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoog, S.S.; Smith, W.W.; Qiu, X.; Janson, C.A.; Hellmig, B.; McQueney, M.S.; O’Donnell, K.; O’Shannessy, D.; DiLella, A.G.; Debouck, C.; et al. Active Site Cavity of Herpesvirus Proteases Revealed by the Crystal Structure of Herpes Simplex Virus Protease/Inhibitor Complex. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 14023–14029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Janson, C.A.; Culp, J.S.; Richardson, S.B.; Debouck, C.; Smith, W.W.; Abdel-Meguid, S.S. Crystal structure of varicella-zoster virus protease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 2874–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ropp, S.L.; Jackson, R.J.; Frey, T.K. The Rubella Virus Nonstructural Protease Requires Divalent Cations for Activity and Functions in trans. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 4463–4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgenfeld, R.; Lei, J.; Zhang, L. The Structure of the Zika Virus Protease, NS2B/NS3pro. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1062, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Chen, C. Understanding HIV-1 protease autoprocessing for novel therapeutic development. Future Med. Chem. 2013, 5, 1215–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, R.; Carrasco, L.; Ventoso, I. Cell Killing by HIV-1 Protease. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 1086–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstaub, D.; Gradi, A.; Bercovitch, Z.; Grosmann, Z.; Nophar, Y.; Luria, S.; Sonenberg, N.; Kahana, C. Poliovirus 2A Protease Induces Apoptotic Cell Death. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000, 20, 1271–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Komissarov, A.A.; Karaseva, M.A.; Roschina, M.P.; Shubin, A.V.; Lunina, N.A.; Kostrov, S.V.; Demidyuk, I.V. Individual Expression of Hepatitis A Virus 3C Protease Induces Ferroptosis in Human Cells In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babél, L.M.; Linneversl, C.J.; Schmidt, B.F. Production of Active Mammalian and Viral Proteases in Bacterial Expression Systems. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2000, 17, 213–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, K.; Fukagawa, T.; Takisawa, H.; Kakimoto, T.; Kanemaki, M. An auxin-based degron system for the rapid depletion of proteins in nonplant cells. Nat. Methods 2009, 6, 917–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Dhali, S.; Srikanth, R.; Ghosh, S.K.; Srivastava, S. Comparative proteomics of mitosis and meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Proteom. 2014, 109, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian, X.; Mahtar, W.N.A.W.; Chiew, S.P.; Miswan, N.; Yin, K.B. Potential use of Pichia pastoris strain SMD1168H expressing DNA topoisomerase I in the screening of potential anti-breast cancer agents. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 19, 5368–5376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Rahman, M.A.; Nazarko, T.Y. Nitrogen Starvation and Stationary Phase Lipophagy Have Distinct Molecular Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Shroff, A.; Nazarko, T.Y. Komagataella phaffii Cue5 Piggybacks on Lipid Droplets for Its Vacuolar Degradation during Stationary Phase Lipophagy. Cells 2022, 11, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernauer, L.; Radkohl, A.; Lehmayer, L.G.K.; Emmerstorfer-Augustin, A. Komagataella phaffii as Emerging Model Organism in Fundamental Research. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 607028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijewantha, N.V.; Kumar, R.; Nazarko, T.Y. Glycogen Granules Are Degraded by Non-Selective Autophagy in Nitrogen-Starved Komagataella phaffii. Cells 2024, 13, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norcliffe, J.L.; Alvarez-Ruiz, E.; Martin-Plaza, J.J.; Steel, P.G.; Denny, P.W. The utility of yeast as a tool for cell-based, target-directed high-throughput screening. Parasitology 2014, 141, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, K.T.; Ko, J.H.; Shin, H.; Sung, M.; Kim, J.Y. Drive-Through Screening Center for COVID-19: A Safe and Efficient Screening System against Massive Community Outbreak. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020, 35, e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Proteins | Percentage Identity |

|---|---|

| nsp1 | No results after the BLAST search |

| nsp2 | 20.4 |

| nsp3 (PLpro) | 30.2 |

| nsp4 | 40 |

| nsp5 (Mpro) | 50.6 |

| nsp6 (putative transmembrane domain) | 34.4 |

| nsp7 (cofactor of nsp12) | 55.4 |

| nsp8 (cofactor of nsp12) | 53.0 |

| nsp9 (RNA replicase) | 52.2 |

| nsp10 | 59.4 |

| nsp11 | No results after the BLAST search |

| nsp12 (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase) | 71.3 |

| nsp13 (helicase) | 72.4 |

| nsp14 (proofreading exoribonuclease) | 62.9 |

| nsp15 (NendoU, endoribonuclease) | 50.6 |

| nsp16 (2′-O-methyltransferase) | 66.3 |

| S (spike glycoprotein) | 35.1 |

| orf3a | No results after the BLAST search |

| E (envelope small membrane protein) inferred from homology | 42.4 |

| M (membrane glycoprotein) inferred from homology | 42.6 |

| orf6 inferred from homology | No results after the BLAST search |

| orf7a | No results after the BLAST search |

| orf8 | No results after the BLAST search |

| N (nucleocapsid protein) | 50.9 |

| orf9b | No results after the BLAST search |

| orf10 | No results after the BLAST search |

| Yeast Species | Virus | Protease | Assay Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae | SARS-CoV | Papain-like protease (PLP) | Growth inhibition of yeast in (the presence of protease) rescued by inhibitor | [103] |

| S. cerevisiae | SARS-CoV-2 | Mpro | Increases in fluorescence and cell number in the presence of protease inhibitor | [104] |

| S. cerevisiae | Human cytomegalovirus | HCMV protease | Rescue of yeast by protease inhibitors by preventing cleavage of Trp1 | [100] |

| S. cerevisiae | SARS-CoV | Coronavirus RNA cap guanine-N7-methyltransferase | Growth of colonies on FAO plates | [105] |

| S. cerevisiae | HIV-1 | VP-1 | Growth inhibition of yeast in (the presence of protease) rescued by inhibitor | [101] |

| S. cerevisiae | HIV-1 | HIV-PR | Programmed—1 ribosomal frameshifting | [106] |

| S. cerevisiae | HIV-1 | HIV-PR | Programmed—1 ribosomal frameshifting | [99] |

| S. cerevisiae | SARS-CoV-2 | Mpro | FACS, FRET, growth inhibition | [107] |

| S. pombe | HIV-1 | HIV-PR | Rescue of growth in the presence of positive hits | [108] |

| S. pombe | HIV-1 | HIV-PR | Rescue of growth in the presence of positive hits | [109] |

| S. pombe | HIV-1 | HIV-PR | Rescue of growth in the presence of positive hits | [110] |

| S. pombe | HIV-1 | HIV-PR | Rescue of growth in the presence of positive hits | [102] |

| Virus | Disease | Nature of Genome | Enzyme Type | Protease | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polio | Polio (or poliomyelitis) | (+) ssRNA | Protease | 2Apro and 3 Cpro/3CDpro | [115,116] |

| Variola | Smallpox | dsDNA | Protease | K7L | [117] |

| MERS | Respiratory disease | (+) ssRNA | Protease | Mpro and PLpro | [118] |

| SARS-CoV | Respiratory disease | (+) ssRNA | Protease | Mpro and PLpro | [119] |

| Dengue | Dengue | (+) ssRNA (capped) | Protease | NS2B/3 | [120] |

| Herpes simplex virus | Cold sores, genital herpes | dsDNA (linear) | Protease | HSV protease | [121] |

| Varicella zoster virus | Chickenpox/varicella/shingles | dsDNA (linear) | Protease | VZV protease | [122] |

| Rubella | German measles or rubella | (+) ssRNA | Protease | NS-pro | [123] |

| Zika | Zika fever | (+) ssRNA | Protease | NS2B-NS3pro | [124] |

| HIV | AIDS | (+) ssRNA (linear) | Protease | HIV-PR | [125] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Srivastava, V.; Kumar, R.; Ahmad, A. Yeast-Based Screening of Anti-Viral Molecules. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 578. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12030578

Srivastava V, Kumar R, Ahmad A. Yeast-Based Screening of Anti-Viral Molecules. Microorganisms. 2024; 12(3):578. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12030578

Chicago/Turabian StyleSrivastava, Vartika, Ravinder Kumar, and Aijaz Ahmad. 2024. "Yeast-Based Screening of Anti-Viral Molecules" Microorganisms 12, no. 3: 578. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12030578

APA StyleSrivastava, V., Kumar, R., & Ahmad, A. (2024). Yeast-Based Screening of Anti-Viral Molecules. Microorganisms, 12(3), 578. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12030578