Lactobacillus sp. for the Attenuation of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease in Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

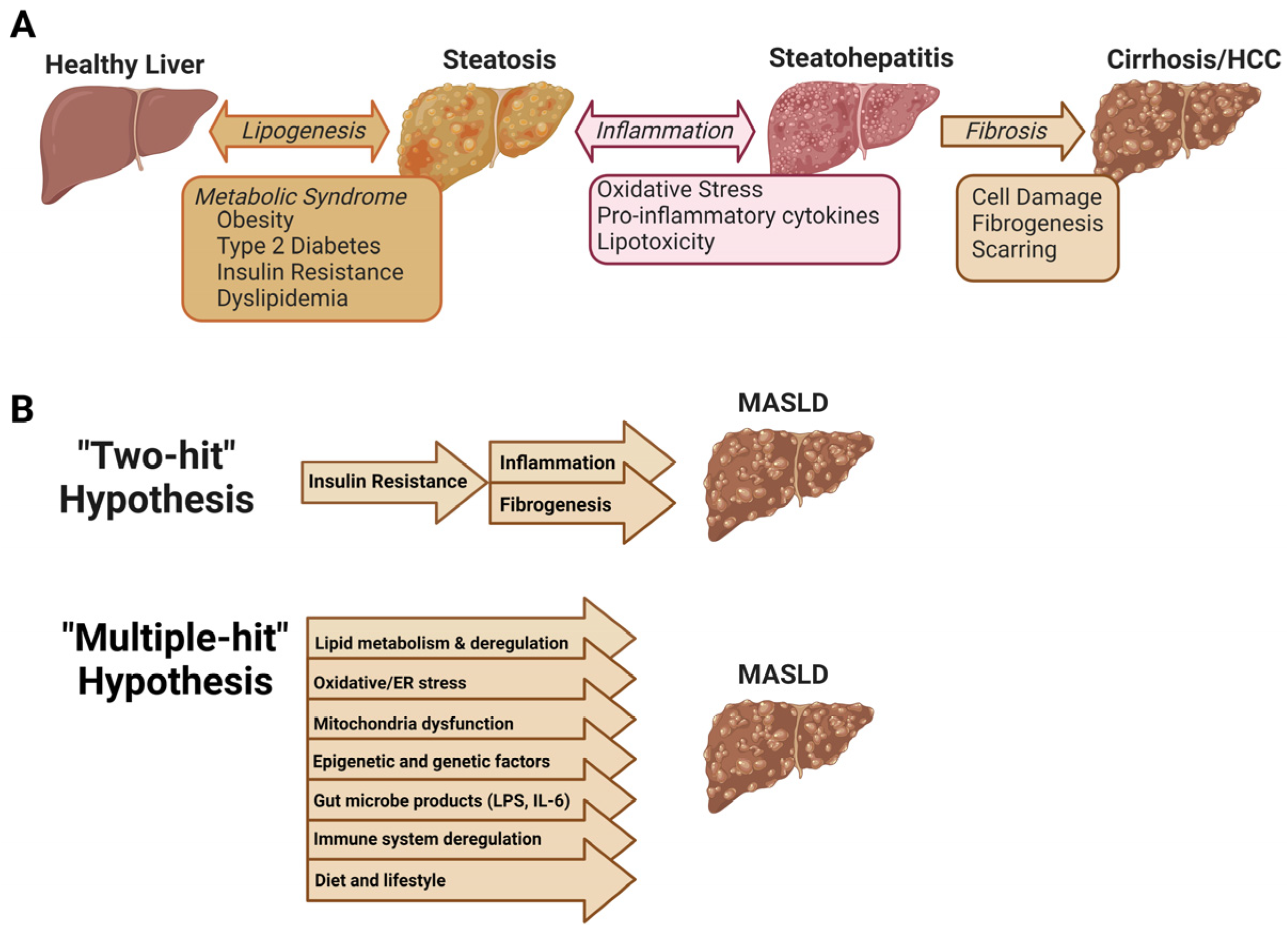

1.1. Pathogenesis of MASLD

1.2. “Multiple Hit” Hypothesis of MASLD

2. Metabolic Pathways Altered by Dysbiosis in MASLD

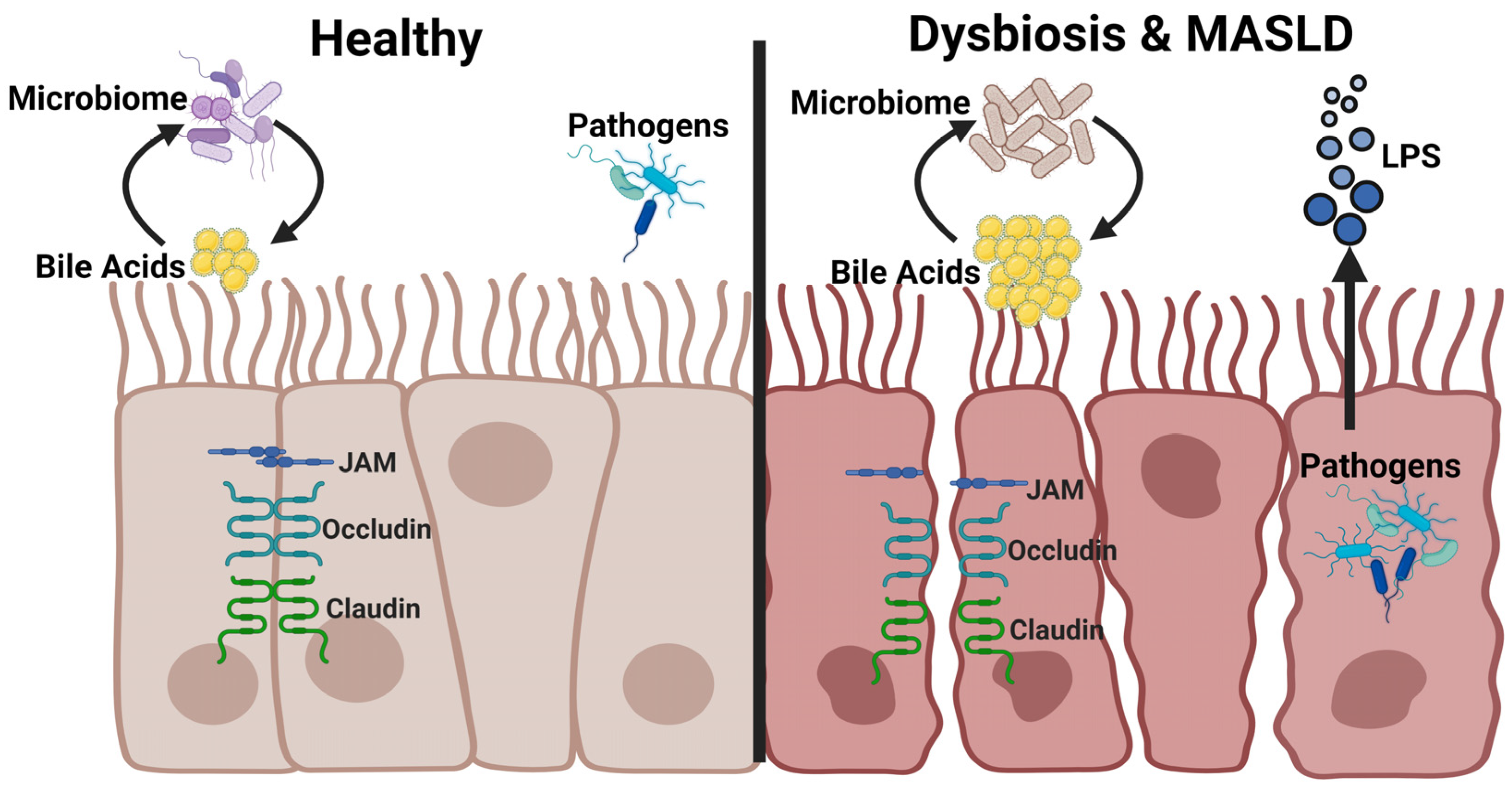

2.1. Intestinal Barrier Function

2.2. Bacterial Endotoxins

2.3. Short Chain Fatty Acids

2.4. Altered Bile Acid Synthesis and Composition

2.5. Increased Energy Harvest

2.6. MASLD and Sarcopenia

3. Lactobacillus for the Treatment of MASLD

3.1. Mechanisms of Action of Lactobacillus spp.

3.2. Intestinal Barrier Improvement

3.3. Gut Microbiome Modulation

3.4. Bile Acids

3.5. Lipids and Steatosis

3.6. Inflammation and Fibrosis

4. Discussion

Limitations of Probiotic Therapy and the Challenge of Sustaining Therapeutic Levels of Probiotics in the Gut

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Loomba, R.; Sanyal, A.J. The global NAFLD epidemic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 10, 686–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, L.F.; Musante, C.J.; Allen, R. A continuous-time Markov chain model of fibrosis progression in NAFLD and NASH. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1130890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loomba, R.; Friedman, S.L.; Shulman, G.I. Mechanisms and disease consequences of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell 2021, 184, 2537–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, R.; Noureddin, M.; Clark, J.M. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Review of Management for Primary Care Providers. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2022, 97, 1700–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzetti, E.; Pinzani, M.; Tsochatzis, E.A. The multiple-hit pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Metabolism 2016, 65, 1038–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferenc, K.; Sokal-Dembowska, A.; Helma, K.; Motyka, E.; Jarmakiewicz-Czaja, S.; Filip, R. Modulation of the Gut Microbiota by Nutrition and Its Relationship to Epigenetics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, V.W.-S.; Ekstedt, M.; Wong, G.L.-H.; Hagström, H. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiriger, J.; Chauhan, K.; Khan, A.; Shahzad, T.; Parra, N.S.; Zhang, P.; Chen, S.; Nguyen, A.; Yan, B.; Bruckbauer, J.; et al. Advancements in Understanding and Treating NAFLD: A Comprehensive Review of Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease and Emerging Therapies. Livers 2023, 3, 637–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierantonelli, I.; Svegliati-Baroni, G. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Basic Pathogenetic Mechanisms in the Progression From NAFLD to NASH. Transplantation 2019, 103, e1–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, Y.; Cohen, D.E. Mechanisms of hepatic triglyceride accumulation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 48, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Yin, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) Pathogenesis and Natural Products for Prevention and Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessone, F.; Razori, M.V.; Roma, M.G. Molecular pathways of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease development and progression. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jandhyala, S.M.; Talukdar, R.; Subramanyam, C.; Vuyyuru, H.; Sasikala, M.; Nageshwar Reddy, D. Role of the normal gut microbiota. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 8787–8803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastelli, M.; Cani, P.D.; Knauf, C. The Gut Microbiome Influences Host Endocrine Functions. Endocr. Rev. 2019, 40, 1271–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrncir, T.; Hrncirova, L.; Kverka, M.; Hromadka, R.; Machova, V.; Trckova, E.; Kostovcikova, K.; Kralickova, P.; Krejsek, J.; Tlaskalova-Hogenova, H. Gut Microbiota and NAFLD: Pathogenetic Mechanisms, Microbiota Signatures, and Therapeutic Interventions. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasirwan, C.O.M.; Lesmana, C.R.A.; Hasan, I.; Sulaiman, A.S.; Gani, R.A. The role of gut microbiota in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Pathways of mechanisms. Biosci. Microbiota Food Heal. 2019, 38, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpino, G.; Del Ben, M.; Pastori, D.; Carnevale, R.; Baratta, F.; Overi, D.; Francis, H.; Cardinale, V.; Onori, P.; Safarikia, S.; et al. Increased Liver Localization of Lipopolysaccharides in Human and Experimental NAFLD. Hepatology 2020, 72, 470–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Wirth, U.; Koch, D.; Schirren, M.; Drefs, M.; Koliogiannis, D.; Nieß, H.; Andrassy, J.; Guba, M.; Bazhin, A.V.; et al. The Role of Gut-Derived Lipopolysaccharides and the Intestinal Barrier in Fatty Liver Diseases. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2022, 26, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yin, M.; Gao, J.; Yu, C.; Lin, J.; Wu, A.; Zhu, J.; Xu, C.; Liu, X. Intestinal Barrier Function in the Pathogenesis of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2022, 11, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tommaso, N.; Gasbarrini, A.; Ponziani, F.R. Intestinal Barrier in Human Health and Disease. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 12836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoletti, A.; Ponziani, F.R.; Biolato, M.; Valenza, V.; Marrone, G.; Sganga, G.; Gasbarrini, A.; Miele, L.; Grieco, A. Intestinal permeability in the pathogenesis of liver damage: From non-alcoholic fatty liver disease to liver transplantation. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 4814–4834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornick, S.; Tawiah, A.; Chadee, K. Roles and regulation of the mucus barrier in the gut. Tissue Barriers 2015, 3, e982426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, P.; Seebauer, C.T.; Mazagova, M.; Horvath, A.; Wang, L.; Llorente, C.; Varki, N.M.; Brandl, K.; Ho, S.B.; Schnabl, B. Deficiency of intestinal mucin-2 protects mice from diet-induced fatty liver disease and obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2016, 310, G310–G322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, M.E.V.; Larsson, J.M.H.; Hansson, G.C. The two mucus layers of colon are organized by the MUC2 mucin, whereas the outer layer is a legislator of host–microbial interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 4659–4665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Huang, W.; Xia, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Ai, L. Cholesterol-lowering potentials of Lactobacillus strain overexpression of bile salt hydrolase on high cholesterol diet-induced hypercholesterolemic mice. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 1684–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, E.; Brenner, D.A. Toll-like receptors and adaptor molecules in liver disease. Hepatology 2008, 48, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilan, Y. Review article: Novel methods for the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis—targeting the gut immune system to decrease the systemic inflammatory response without immune suppression. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 44, 1168–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takiishi, T.; Fenero, C.I.M.; Câmara, N.O.S. Intestinal barrier and gut microbiota: Shaping our immune responses throughout life. Tissue Barriers 2017, 5, e1373208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakaroun, R.M.; Massier, L.; Kovacs, P. Gut Microbiome, Intestinal Permeability, and Tissue Bacteria in Metabolic Disease: Perpetrators or Bystanders? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Wang, Q.; Chang, R.; Zhou, X.; Xu, C. Intestinal Barrier Function-Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Interactions and Possible Role of Gut Microbiota. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2019, 67, 2754–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, D.; Zong-Shun, L.; Bang-Mao, W.; Lu, Z. Expression of intestinal tight junction proteins in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatogastroenterology 2014, 61, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rahman, K.; Desai, C.; Iyer, S.S.; Thorn, N.E.; Kumar, P.; Liu, Y.; Smith, T.; Neish, A.S.; Li, H.; Tan, S.; et al. Loss of Junctional Adhesion Molecule A Promotes Severe Steatohepatitis in Mice on a Diet High in Saturated Fat, Fructose, and Cholesterol. Gastroenterology 2016, 151, 733–746.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allam-Ndoul, B.; Castonguay-Paradis, S.; Veilleux, A. Gut Microbiota and Intestinal Trans-Epithelial Permeability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miele, L.; Valenza, V.; La Torre, G.; Montalto, M.; Cammarota, G.; Ricci, R.; Mascianà, R.; Forgione, A.; Gabrieli, M.L.; Perotti, G.; et al. Increased intestinal permeability and tight junction alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2009, 49, 1877–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gäbele, E.; Dostert, K.; Hofmann, C.; Wiest, R.; Schölmerich, J.; Hellerbrand, C.; Obermeier, F. DSS induced colitis increases portal LPS levels and enhances hepatic inflammation and fibrogenesis in experimental NASH. J. Hepatol. 2011, 55, 1391–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albillos, A.; de Gottardi, A.; Rescigno, M. The gut-liver axis in liver disease: Pathophysiological basis for therapy. J. Hepatol. 2020, 72, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, R.A.; Tiffany, C.M.; Pakpour, N.; Lokken, K.L.; Tiffany, C.R.; Cheung, K.; Tsolis, R.M.; Luckhart, S. Mast cells and histamine alter intestinal permeability during malaria parasite infection. Immunobiology 2016, 221, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konturek, P.C.; Harsch, I.A.; Konturek, K.; Schink, M.; Konturek, T.; Neurath, M.F.; Zopf, Y. Gut–Liver Axis: How Do Gut Bacteria Influence the Liver? Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henao-Mejia, J.; Elinav, E.; Jin, C.; Hao, L.; Mehal, W.Z.; Strowig, T.; Thaiss, C.A.; Kau, A.L.; Eisenbarth, S.C.; Jurczak, M.J.; et al. Inflammasome-mediated dysbiosis regulates progression of NAFLD and obesity. Nature 2012, 482, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, W.; Hao, Y.; Xie, H.; Ni, Y.; Zhao, R. Hepatic Inflammatory Response to Exogenous LPS Challenge is Exacerbated in Broilers with Fatty Liver Disease. Animals 2020, 10, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwabara, W.M.T.; Yokota, C.N.F.; Curi, R.; Alba-Loureiro, T.C. Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes mellitus induce lipopolysaccharide tolerance in rat neutrophils. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Hegazy, M.; Mogawer, S.M.; Alnaggar, A.R.L.R.; A Ghoniem, O.; Samie, R.M.A. Serum LPS and CD163 Biomarkers Confirming the Role of Gut Dysbiosis in Overweight Patients with NASH. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 3861–3872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barchetta, I.; Cimini, F.A.; Sentinelli, F.; Chiappetta, C.; Di Cristofano, C.; Silecchia, G.; Leonetti, F.; Baroni, M.G.; Cavallo, M.G. Reduced Lipopolysaccharide-Binding Protein (LBP) Levels Are Associated with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and Adipose Inflammation in Human Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolodziejczyk, A.A.; Zheng, D.; Shibolet, O.; Elinav, E. The role of the microbiome in NAFLD and NASH. EMBO Mol. Med. 2019, 11, e9302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; He, J.; Gao, N.; Lu, X.; Li, M.; Wu, X.; Liu, Z.; Jin, Y.; Liu, J.; Xu, J.; et al. Probiotics may delay the progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by restoring the gut microbiota structure and improving intestinal endotoxemia. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tack, C.J.; Stienstra, R.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Netea, M.G. Inflammation links excess fat to insulin resistance: The role of the interleukin-1 family. Immunol. Rev. 2012, 249, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plomgaard, P.; Bouzakri, K.; Krogh-Madsen, R.; Mittendorfer, B.; Zierath, J.R.; Pedersen, B.K. Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Induces Skeletal Muscle Insulin Resistance in Healthy Human Subjects via Inhibition of Akt Substrate 160 Phosphorylation. Diabetes 2005, 54, 2939–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestri, M.; Santopaolo, F.; Pompili, M.; Gasbarrini, A.; Ponziani, F.R. Gut microbiota modulation in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Effects of current treatments and future strategies. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1110536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Yin, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, W. Gut Microbiota-Derived Components and Metabolites in the Progression of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD). Nutrients 2019, 11, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Ren, M.; Yang, J.; Cai, C.; Cheng, W.; Zhou, X.; Lu, D.; Ji, F. Gut microbiome and microbial metabolites in NAFLD and after bariatric surgery: Correlation and causality. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1003755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, M.M.; Ahmed, M.M.; Salah-Eldin, A.-E.; Abdel-Aal, A.A.-A. Butyrate regulates leptin expression through different signaling pathways in adipocytes. J. Vet. Sci. 2011, 12, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, R.J.; Peng, L.; Barry, N.A.; Cline, G.W.; Zhang, D.; Cardone, R.L.; Petersen, K.F.; Kibbey, R.G.; Goodman, A.L.; Shulman, G.I. Acetate mediates a microbiome–brain–β-cell axis to promote metabolic syndrome. Nature 2016, 534, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, M.A.G.; Canfora, E.E.; Jocken, J.W.E.; Blaak, E.E. The Short-Chain Fatty Acid Acetate in Body Weight Control and Insulin Sensitivity. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaki, S.-I.; Tazoe, H.; Hayashi, H.; Kashiwabara, H.; Tooyama, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Kuwahara, A. Expression of the short-chain fatty acid receptor, GPR43, in the human colon. J. Mol. Histol. 2008, 39, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tazoe, H.; Otomo, Y.; Karaki, S.-I.; Kato, I.; Fukami, Y.; Terasaki, M.; Kuwahara, A. Expression of short-chain fatty acid receptor GPR41 in the human colon. Biomed. Res. 2009, 30, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nøhr, M.K.; Pedersen, M.H.; Gille, A.; Egerod, K.L.; Engelstoft, M.S.; Husted, A.S.; Sichlau, R.M.; Grunddal, K.V.; Seier Poulsen, S.; Han, S.; et al. GPR41/FFAR3 and GPR43/FFAR2 as Cosensors for Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Enteroendocrine Cells vs FFAR3 in Enteric Neurons and FFAR2 in Enteric Leukocytes. Endocrinology 2013, 154, 3552–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruta, H.; Yoshimura, Y.; Araki, A.; Kimoto, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Yamashita, H. Activation of AMP-Activated Protein Kinase and Stimulation of Energy Metabolism by Acetic Acid in L6 Myotube Cells. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, M.G.; Jeong, S.; Yun, C.-H.; Han, S.H. Short-chain Fatty Acids Inhibit Staphylococcal Lipoprotein-induced Nitric Oxide Production in Murine Macrophages. Immune Netw. 2019, 19, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juanola, O.; Ferrusquía-Acosta, J.; García-Villalba, R.; Zapater, P.; Magaz, M.; Marín, A.; Olivas, P.; Baiges, A.; Bellot, P.; Turon, F.; et al. Circulating levels of butyrate are inversely related to portal hypertension, endotoxemia, and systemic inflammation in patients with cirrhosis. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 11595–11605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Cuesta-Zuluaga, J.; Mueller, N.T.; Corrales-Agudelo, V.; Velásquez-Mejía, E.P.; Carmona, J.A.; Abad, J.M.; Escobar, J.S. Metformin Is Associated With Higher Relative Abundance of Mucin-Degrading Akkermansia muciniphilaand Several Short-Chain Fatty Acid–Producing Microbiota in the Gut. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Z.; Liao, Y.; Zhou, T.; Xiang, Q. A potential link between plasma short-chain fatty acids, TNF-α level and disease progression in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A retrospective study. Exp. Ther. Med. 2022, 24, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behary, J.; Amorim, N.; Jiang, X.-T.; Raposo, A.; Gong, L.; McGovern, E.; Ibrahim, R.; Chu, F.; Stephens, C.; Jebeili, H.; et al. Gut microbiota impact on the peripheral immune response in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease related hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, H.-J.; Hung, W.-C.; Hung, W.-W.; Lee, Y.-J.; Chen, Y.-C.; Lee, C.-Y.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Dai, C.-Y. Circulating Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Severity in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdes, A.M.; Walter, J.; Segal, E.; Spector, T.D. Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. BMJ 2018, 361, k2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, M.R.; Shin, A.; Siwiec, R.; James-Stevenson, T.; Bohm, M.; Rogers, N.; Wo, J.; Waseem, L.; Gupta, A.; Jarrett, M.; et al. Associations of Fecal Short Chain Fatty Acids With Colonic Transit, Fecal Bile Acid, and Food Intake in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2023, 14, e00541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchin, S.; Bertin, L.; Bonazzi, E.; Lorenzon, G.; De Barba, C.; Barberio, B.; Zingone, F.; Maniero, D.; Scarpa, M.; Ruffolo, C.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Human Health: From Metabolic Pathways to Current Therapeutic Implications. Life 2024, 14, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thing, M.; Werge, M.P.; Kimer, N.; Hetland, L.E.; Rashu, E.B.; Nabilou, P.; Junker, A.E.; Galsgaard, E.D.; Bendtsen, F.; Laupsa-Borge, J.; et al. Targeted metabolomics reveals plasma short-chain fatty acids are associated with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024, 24, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Coker, O.O.; Chu, E.S.; Fu, K.; Lau, H.C.H.; Wang, Y.-X.; Chan, A.W.H.; Wei, H.; Yang, X.; Sung, J.J.Y.; et al. Dietary cholesterol drives fatty liver-associated liver cancer by modulating gut microbiota and metabolites. Gut 2021, 70, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangana, E.; Omolekulo, T.; Areola, E.; Olaniyi, K.; Soladoye, A.; Olatunji, L. Sodium acetate protects against nicotine-induced excess hepatic lipid in male rats by suppressing xanthine oxidase activity. Chem. Interact. 2020, 316, 108929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Fan, J.-G. Microbial metabolites in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 2019–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Pan, Q.; Xin, F.-Z.; Zhang, R.-N.; He, C.-X.; Chen, G.-Y.; Liu, C.; Chen, Y.-W.; Fan, J.-G. Sodium butyrate attenuates high-fat diet-induced steatohepatitis in mice by improving gut microbiota and gastrointestinal barrier. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.-H.; Wang, Z.-X.; Zhou, D.; Han, Y.; Ma, F.; Hu, Z.; Xin, F.-Z.; Liu, X.-L.; Ren, T.-Y.; Zhang, F.; et al. Sodium Butyrate Supplementation Inhibits Hepatic Steatosis by Stimulating Liver Kinase B1 and Insulin-Induced Gene. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 12, 857–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Ciaula, A.; Baj, J.; Garruti, G.; Celano, G.; De Angelis, M.; Wang, H.H.; Di Palo, D.M.; Bonfrate, L.; Wang, D.Q.-H.; Portincasa, P. Liver Steatosis, Gut-Liver Axis, Microbiome and Environmental Factors. A Never-Ending Bidirectional Cross-Talk. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larabi, A.B.; Masson, H.L.P.; Bäumler, A.J. Bile acids as modulators of gut microbiota composition and function. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2172671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, J.Y.L.; Ferrell, J.M. Bile Acid Metabolism in Liver Pathobiology. Gene Expr. 2018, 18, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, A.; Inoue, R.; Inatomi, O.; Bamba, S.; Naito, Y.; Andoh, A. Gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, M.H.; Walker, M.E.; Stewart, A.K.; O’flaherty, S.; Gentry, E.C.; Patel, S.; Beaty, V.V.; Allen, G.; Pan, M.; Simpson, J.B.; et al. Bile salt hydrolases shape the bile acid landscape and restrict Clostridioides difficile growth in the murine gut. Nat. Microbiol. 2023, 8, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillard, J.; Clerbaux, L.-A.; Nachit, M.; Sempoux, C.; Staels, B.; Bindels, L.B.; Tailleux, A.; Leclercq, I.A. Bile acids contribute to the development of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. JHEP Rep. 2022, 4, 100387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, B.; Tong, J.; Hao, H.; Yang, Z.; Chen, K.; Xu, H.; Wang, A. Bile acid coordinates microbiota homeostasis and systemic immunometabolism in cardiometabolic diseases. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 2129–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Ramón, V.; Chinchilla-López, P.; Ramírez-Pérez, O.; Méndez-Sánchez, N. Bile Acids in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: New Concepts and Therapeutic Advances. Ann. Hepatol. 2017, 16, S58–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, A.D.; Novak, P.; Shipkova, P.; Aranibar, N.; Robertson, D.; Reily, M.D.; Lu, Z.; Lehman-McKeeman, L.D.; Cherrington, N.J. Decreased hepatotoxic bile acid composition and altered synthesis in progressive human nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2013, 268, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottlieb, A.; Canbay, A.; Gottlieb, A.; Canbay, A. Why Bile Acids Are So Important in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) Progression. Cells 2019, 8, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrell, J.M.; Chiang, J.Y. Bile acid receptors and signaling crosstalk in the liver, gut and brain. Liver Res. 2021, 5, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.-X.; Shen, W.; Sun, H. Effects of nuclear receptor FXR on the regulation of liver lipid metabolism in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatol. Int. 2010, 4, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, J.Y.L.; Ferrell, J.M. Bile Acids as Metabolic Regulators and Nutrient Sensors. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2019, 39, 175–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Luo, L.; Zhou, T.; Feng, X.; Ye, J.; Zhong, B. Alterations in Circulating Bile Acids in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilson, J.; Scorletti, E.; Swann, J.R.; Byrne, C.D. Bile Acids as Emerging Players at the Intersection of Steatotic Liver Disease and Cardiovascular Diseases. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Ju, X.; Chen, W.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Z.; Aluko, R.E.; He, R. Rice bran attenuated obesity via alleviating dyslipidemia, browning of white adipocytes and modulating gut microbiota in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 2406–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Hamady, M.; Yatsunenko, T.; Cantarel, B.L.; Duncan, A.; Ley, R.E.; Sogin, M.L.; Jones, W.J.; Roe, B.A.; Affourtit, J.P.; et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature 2009, 457, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michail, S.; Lin, M.; Frey, M.R.; Fanter, R.; Paliy, O.; Hilbush, B.; Reo, N.V. Altered gut microbial energy and metabolism in children with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2015, 91, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley, R.E.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Klein, S.; Gordon, J.I. Human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature 2006, 444, 1022–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, Y.K.; Estaki, M.; Gibson, D.L. Clinical Consequences of Diet-Induced Dysbiosis. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 63 (Suppl. S2), 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Zhang, J.; Luo, Q.; Peng, L. Effects of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease on sarcopenia: Evidence from genetic methods. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Wang, Y.; Fu, W.; Zhang, G.; Feng, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, F.; Zhang, L.; Deng, Y. Association between sarcopenia and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 978110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri-Mashhadi, N.; Navab, F.; Ansari, S.; Rouhani, M.H.; Hajhashemy, Z.; Saraf-Bank, S. A meta-analysis of the effect of probiotic administration on age-related sarcopenia. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 4975–4987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.-S.; Shin, Y.-J.; Ma, X.; Park, H.-S.; Hwang, Y.-H.; Kim, D.-H. Bifidobacterium bifidum and Lactobacillus paracasei alleviate sarcopenia and cognitive impairment in aged mice by regulating gut microbiota-mediated AKT, NF-κB, and FOXO3a signaling pathways. Immun. Ageing 2023, 20, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chang, S.; Chang, H.; Wu, C.; Pan, C.; Chang, C.; Chan, C.; Huang, H. Probiotic supplementation attenuates age-related sarcopenia via the gut–muscle axis in SAMP8 mice. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 515–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemarajata, P.; Versalovic, J. Effects of probiotics on gut microbiota: Mechanisms of intestinal immunomodulation and neuromodulation. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2013, 6, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzaal, M.; Saeed, F.; Shah, Y.A.; Hussain, M.; Rabail, R.; Socol, C.T.; Hassoun, A.; Pateiro, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Rusu, A.V.; et al. Human gut microbiota in health and disease: Unveiling the relationship. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 999001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, F.H.; Nookaew, I.; Petranovic, D.; Nielsen, J. Prospects for systems biology and modeling of the gut microbiome. Trends Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoufou, M.; Tsigalou, C.; Vradelis, S.; Bezirtzoglou, E. The Networked Interaction between Probiotics and Intestine in Health and Disease: A Promising Success Story. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gratz, S.W. Probiotics and gut health: A special focus on liver diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dempsey, E.; Corr, S.C. Lactobacillus spp. for Gastrointestinal Health: Current and Future Perspectives. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 840245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żukiewicz-Sobczak, W.; Wróblewska, P.; Adamczuk, P.; Silny, W. Probiotic lactic acid bacteria and their potential in the prevention and treatment of allergic diseases. Central Eur. J. Immunol. 2014, 1, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cerbo, A.; Palmieri, B.; Aponte, M.; Morales-Medina, J.C.; Iannitti, T. Mechanisms and therapeutic effectiveness of lactobacilli. J. Clin. Pathol. 2016, 69, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, A.; Shehzad, A.; Niazi, S.; Zahid, A.; Ashraf, W.; Iqbal, M.W.; Rehman, A.; Riaz, T.; Aadil, R.M.; Khan, I.M.; et al. Probiotics: Mechanism of action, health benefits and their application in food industries. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1216674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanmani, P.; Kim, H. Probiotics counteract the expression of hepatic profibrotic genes via the attenuation of TGF-β/SMAD signaling and autophagy in hepatic stellate cells. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khushboo; Karnwal, A.; Malik, T. Characterization and selection of probiotic lactic acid bacteria from different dietary sources for development of functional foods. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1170725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, E.D.; Antony, J.M.; Crowley, D.C.; Piano, A.; Bhardwaj, R.; Tompkins, T.A.; Evans, M. Efficacy of Lactobacillus paracasei HA-196 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175 in Alleviating Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofori, F.; Dargenio, V.N.; Dargenio, C.; Miniello, V.L.; Barone, M.; Francavilla, R. Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Effects of Probiotics in Gut Inflammation: A Door to the Body. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 578386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobreva, L.; Atanasova, N.; Donchev, P.; Krumova, E.; Abrashev, R.; Karakirova, Y.; Mladenova, R.; Tolchkov, V.; Ralchev, N.; Dishliyska, V.; et al. Candidate-Probiotic Lactobacilli and Their Postbiotics as Health-Benefit Promoters. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diop, L.; Guillou, S.; Durand, H. Probiotic food supplement reduces stress-induced gastrointestinal symptoms in volunteers: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Nutr. Res. 2008, 28, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Hai, D.; Wei, C.; Zhang, L.; Li, P. The Functional Roles of Lactobacillus acidophilus in Different Physiological and Pathological Processes. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 32, 1226–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.J.; Lee, J.M.; Hasan, T.; Lee, B.-J.; Lim, S.G.; Kong, I.-S. Effects of probiotic supplementation of a plant-based protein diet on intestinal microbial diversity, digestive enzyme activity, intestinal structure, and immunity in olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 92, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.; He, Z.; Wang, T.; Wang, X.; Wang, T.; Long, M. Lactobacillus salivarius WZ1 Inhibits the Inflammatory Injury of Mouse Jejunum Caused by Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli K88 by Regulating the TLR4/NF-κB/MyD88 Inflammatory Pathway and Gut Microbiota. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Chen, S.; Ren, F.; Li, Y. Lactobacillus paracasei N1115 attenuates obesity in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritze, Y.; Bárdos, G.; Claus, A.; Ehrmann, V.; Bergheim, I.; Schwiertz, A.; Bischoff, S.C. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG Protects against Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Mice. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e80169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.B.; Jun, D.W.; Kang, B.-K.; Lim, J.H.; Lim, S.; Chung, M.-J. Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Study of a Multispecies Probiotic Mixture in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, V.W.-S.; Vergniol, J.; Wong, G.L.-H.; Foucher, J.; Chan, A.W.-H.; Chermak, F.; Choi, P.C.-L.; Merrouche, W.; Chu, S.H.-T.; Pesque, S.; et al. Liver Stiffness Measurement Using XL Probe in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 107, 1862–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-S.; Lim, S.K.; Lee, J.; Park, H.K.; Kwon, M.-S.; Yun, M.; Kim, N.; Oh, Y.J.; Choi, H.-J. Latilactobacillus sakei WIKIM31 Decelerates Weight Gain in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Mice by Modulating Lipid Metabolism and Suppressing Inflammation. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 31, 1568–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.R.; Park, H.-J.; Kang, D.; Chung, H.; Nam, M.H.; Lee, Y.; Park, J.-H.; Lee, H.-Y. A protective mechanism of probiotic Lactobacillus against hepatic steatosis via reducing host intestinal fatty acid absorption. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019, 51, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Shi, L.P.; Shi, L.; Xu, L. Efficacy of probiotics on the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi 2018, 57, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Panpetch, W.; Phuengmaung, P.; Cheibchalard, T.; Somboonna, N.; Leelahavanichkul, A.; Tumwasorn, S. Lacticaseibacillus casei Strain T21 Attenuates Clostridioides difficile Infection in a Murine Model Through Reduction of Inflammation and Gut Dysbiosis With Decreased Toxin Lethality and Enhanced Mucin Production. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 745299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Huang, Y.; Wang, F. Short-Chain Fatty Acids Manifest Stimulative and Protective Effects on Intestinal Barrier Function Through the Inhibition of NLRP3 Inflammasome and Autophagy. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 49, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karczewski, J.; Troost, F.J.; Konings, I.; Dekker, J.; Kleerebezem, M.; Brummer, R.-J.M.; Wells, J.M. Regulation of human epithelial tight junction proteins by Lactobacillus plantarum in vivo and protective effects on the epithelial barrier. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2010, 298, G851–G859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Henry, K.C.; Donato, K.A.; Shen-Tu, G.; Gordanpour, M.; Sherman, P.M. Lactobacillus rhamnosus Strain GG Prevents Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7-Induced Changes in Epithelial Barrier Function. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 1340–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, P.L.; Laight, D.; Aspinall, R.J.; Higginson, A.; Cummings, M.H. A randomised placebo controlled trial of VSL#3® probiotic on biomarkers of cardiovascular risk and liver injury in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021, 21, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, L.A.; Wang, Z.; Liddle, C.; Melton, P.E.; Ariff, A.; Chandraratna, H.; Tan, J.; Ching, H.; Coulter, S.; De Boer, B.; et al. Bile acids associate with specific gut microbiota, low-level alcohol consumption and liver fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2020, 40, 1356–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delik, A.; Dinçer, S.; Ülger, Y.; Akkız, H.; Karaoğullarından, Ü. Metagenomic identification of gut microbiota distribution on the colonic mucosal biopsy samples in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gene 2022, 833, 146587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hullar, M.A.J.; Jenkins, I.C.; Randolph, T.W.; Curtis, K.R.; Monroe, K.R.; Ernst, T.; Shepherd, J.A.; Stram, D.O.; Cheng, I.; Kristal, B.S.; et al. Associations of the gut microbiome with hepatic adiposity in the Multiethnic Cohort Adiposity Phenotype Study. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1965463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.; Sun, D.; Liu, X.; She, Z.-G.; Chen, Y. The Role of the Intestinal Microbiota in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 812610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jee, J.J.; Lim, J.; Park, S.; Koh, H.; Lee, H.W. Gut microbial community differentially characterizes patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 37, 1822–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Chen, C.; Cui, J.; Lu, J.; Yan, C.; Wei, X.; Zhao, X.; Li, N.; Li, S.; Xue, G.; et al. Fatty Liver Disease Caused by High-Alcohol-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 675–688.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Chierico, F.; Nobili, V.; Vernocchi, P.; Russo, A.; De Stefanis, C.; Gnani, D.; Furlanello, C.; Zandonà, A.; Paci, P.; Capuani, G.; et al. Gut microbiota profiling of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and obese patients unveiled by an integrated meta-omics-based approach. Hepatology 2017, 65, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, H.; Long, X.; Ni, Y.; Qian, L.; Nychas, E.; Siliceo, S.L.; Pohl, D.; Hanhineva, K.; Liu, Y.; Xu, A.; et al. Risk assessment with gut microbiome and metabolite markers in NAFLD development. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabk0855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, J.; Despot, T.; Rodriguez, D.A.; Khan, I.; Mech, E.; Khan, M.; Bojadzija, M.; Pai, N. Implications of Microbiota and Immune System in Development and Progression of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Gu, M.; Werlinger, P.; Cho, J.-H.; Cheng, J.; Suh, J.-W. Lactobacillus sakei MJM60958 as a Potential Probiotic Alleviated Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet by Modulating Lipid Metabolism, Inflammation, and Gut Microbiota. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riezu-Boj, J.I.; Barajas, M.; Pérez-Sánchez, T.; Pajares, M.J.; Araña, M.; Milagro, F.I.; Urtasun, R. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum DSM20174 Attenuates the Progression of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease by Modulating Gut Microbiota, Improving Metabolic Risk Factors, and Attenuating Adipose Inflammation. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, V.W.S.; Wong, G.L.H.; Chim, A.M.L.; Chu, W.C.W.; Yeung, D.K.W.; Li, K.C.T.; Chan, H.L.Y. Treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis with probiotics. A proof-of-concept study. Ann. Hepatol. 2013, 12, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajan, K.; MacSharry, J.; Casey, P.G.; Shanahan, F.; Joyce, S.A.; Gahan, C.G.M. Unconjugated Bile Acids Influence Expression of Circadian Genes: A Potential Mechanism for Microbe-Host Crosstalk. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgin, M.; Kriaa, A.; Mkaouar, H.; Mariaule, V.; Jablaoui, A.; Maguin, E.; Rhimi, M. Bile Salt Hydrolases: At the Crossroads of Microbiota and Human Health. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kriaa, A.; Bourgin, M.; Potiron, A.; Mkaouar, H.; Jablaoui, A.; Gérard, P.; Maguin, E.; Rhimi, M. Microbial impact on cholesterol and bile acid metabolism: Current status and future prospects. J. Lipid Res. 2019, 60, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, X.-C.; Luo, X.-G.; Wang, C.-X.; Ma, D.-Y.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.-Y.; Li, W.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, T.-C. Cloning and analysis of bile salt hydrolase genes from Lactobacillus plantarum CGMCC No. 8198. Biotechnol. Lett. 2014, 36, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sridevi, N.; Vishwe, P.; Prabhune, A. Hypocholesteremic effect of bile salt hydrolase from Lactobacillus buchneri ATCC 4005. Food Res. Int. 2009, 42, 516–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.-C.; Ding, X.-C.; Liu, H.-J.; Ma, W.-L.; Feng, X.-Y.; Ma, L.-N. Effects of Lactobacillus paracasei N1115 on gut microbial imbalance and liver function in patients with hepatitis B-related cirrhosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 1556–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, N.; Yang, F.; Li, A.; Prifti, E.; Chen, Y.; Shao, L.; Guo, J.; Le Chatelier, E.; Yao, J.; Wu, L.; et al. Alterations of the human gut microbiome in liver cirrhosis. Nature 2014, 513, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, L.-G.; Ahmad, R.; Yuen, K.-H.; Liong, M.-T. Lactobacillus acidophilus CHO-220 and inulin reduced plasma total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol via alteration of lipid transporters. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 5048–5058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.L.; Martoni, C.J.; Prakash, S. Cholesterol lowering and inhibition of sterol absorption by Lactobacillus reuteri NCIMB 30242: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 1234–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.L.; Martoni, C.J.; Parent, M.; Prakash, S. Cholesterol-lowering efficacy of a microencapsulated bile salt hydrolase-active Lactobacillus reuteri NCIMB 30242 yoghurt formulation in hypercholesterolaemic adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107, 1505–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpeli, A.; Taranto, M.P.; Cravero, R.C.; Tavella, M.; Fasano, V.; Vicentin, D.; Ferrari, G.; Magrini, G.; Hébert, E.; de Valdez, G.F.; et al. Effect of Daily Consumption of Lactobacillus reuteri CRL 1098 on Cholesterol Reduction in Hypercholesterolemic Subjects. Food Nutr. Sci. 2015, 06, 1583–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liong, M.; Shah, N. Bile salt deconjugation ability, bile salt hydrolase activity and cholesterol co-precipitation ability of lactobacilli strains. Int. Dairy J. 2005, 15, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, S.; Guo, J.; Xie, Q.; Evivie, S.E.; Song, Y.; Li, B.; Huo, G. The Protective Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum KLDS 1.0344 on LPS-Induced Mastitis In Vitro and In Vivo. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 770822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.; Park, K.-Y.; Ji, Y.; Park, S.; Holzapfel, W.; Hyun, C.-K. Protective effects of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG against dyslipidemia in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 473, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Hou, Q.; Zheng, W.; Yang, T.; Yan, X. Lactobacillus gasseri LA39 promotes hepatic primary bile acid biosynthesis and intestinal secondary bile acid biotransformation. J. Zhejiang Univ. B 2023, 24, 734–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Jiang, C.; Krausz, K.W.; Li, Y.; Albert, I.; Hao, H.; Fabre, K.M.; Mitchell, J.B.; Patterson, A.D.; Gonzalez, F.J. Microbiome remodelling leads to inhibition of intestinal farnesoid X receptor signalling and decreased obesity. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degirolamo, C.; Rainaldi, S.; Bovenga, F.; Murzilli, S.; Moschetta, A. Microbiota Modification with Probiotics Induces Hepatic Bile Acid Synthesis via Downregulation of the Fxr-Fgf15 Axis in Mice. Cell Rep. 2014, 7, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabavi, S.; Rafraf, M.; Somi, M.; Homayouni-Rad, A.; Asghari-Jafarabadi, M. Effects of probiotic yogurt consumption on metabolic factors in individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 7386–7393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, K.; Yen, T.; Huang, C.; Hong, K. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG as dietary supplement improved survival from lipopolysaccharides-induced sepsis in mice. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 6786–6793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaro-Duchesneau, C.; Jones, M.L.; Shah, D.; Jain, P.; Saha, S.; Prakash, S. Cholesterol Assimilation by Lactobacillus Probiotic Bacteria: An In Vitro Investigation. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 380316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-C.; Lin, P.-P.; Hsieh, Y.-M.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Wu, H.-C.; Huang, C.-C. Cholesterol-Lowering Potentials of Lactic Acid Bacteria Based on Bile-Salt Hydrolase Activity and Effect of Potent Strains on Cholesterol Metabolism In Vitro and In Vivo. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Jeong, D.; Kang, I.; Kim, H.; Song, K.; Seo, K. Dual function of Lactobacillus kefiri DH5 in preventing high-fat-diet-induced obesity: Direct reduction of cholesterol and upregulation of PPAR-α in adipose tissue. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1700252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, F.; Ishida, Y.; Sawada, D.; Ashida, N.; Sugawara, T.; Sakai, M.; Goto, T.; Kawada, T.; Fujiwara, S. Fragmented Lactic Acid Bacterial Cells Activate Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors and Ameliorate Dyslipidemia in Obese Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 2549–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Duan, C.; Zhang, X.; Gao, L.; Li, S. Lactobacillus plantarum NA136 improves the non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by modulating the AMPK/Nrf2 pathway. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 5843–5850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardie, D.G.; Pan, D.A. Regulation of fatty acid synthesis and oxidation by the AMP-activated protein kinase. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2002, 30, 1064–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saponaro, C.; Gaggini, M.; Carli, F.; Gastaldelli, A. The Subtle Balance between Lipolysis and Lipogenesis: A Critical Point in Metabolic Homeostasis. Nutrients 2015, 7, 9453–9474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.K.; Marcinko, K.; Desjardins, E.M.; Lally, J.S.; Ford, R.J.; Steinberg, G.R. Treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Role of AMPK. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 311, E730–E740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, H.Y.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, S.J.; Jo, H.K.; Kim, G.W.; Chung, S.H. Betulinic acid alleviates non-alcoholic fatty liver by inhibiting SREBP1 activity via the AMPK–mTOR–SREBP signaling pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2013, 85, 1330–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivey, K.L.; Hodgson, J.M.; Kerr, D.A.; Thompson, P.L.; Stojceski, B.; Prince, R.L. The effect of yoghurt and its probiotics on blood pressure and serum lipid profile; a randomised controlled trial. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 25, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famouri, F.; Shariat, Z.; Hashemipour, M.; Keikha, M.; Kelishadi, R. Effects of Probiotics on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Obese Children and Adolescents. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 64, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aller, R.; De Luis, D.A.; Izaola, O.; Conde, R.; Gonzalez Sagrado, M.; Primo, D.; Fuent, B.D.L.; Gonzalez, J. Effect of a probiotic on liver aminotransferases in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients: A double blind ran-domized clinical trial. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2011, 15, 1090–1095. [Google Scholar]

- Kobyliak, N.; Abenavoli, L.; Mykhalchyshyn, G.; Kononenko, L.; Boccuto, L.; Kyriienko, D.; Dynnyk, O. A Multi-strain Probiotic Reduces the Fatty Liver Index, Cytokines and Aminotransferase levels in NAFLD Patients: Evidence from a Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. 2018, 27, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ejtahed, H.; Mohtadi-Nia, J.; Homayouni-Rad, A.; Niafar, M.; Asghari-Jafarabadi, M.; Mofid, V.; Akbarian-Moghari, A. Effect of probiotic yogurt containing Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium lactis on lipid profile in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 3288–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toshimitsu, T.; Gotou, A.; Sashihara, T.; Furuichi, K.; Hachimura, S.; Shioya, N.; Suzuki, S.; Asami, Y. Ingesting Yogurt Containing Lactobacillus plantarum OLL2712 Reduces Abdominal Fat Accumulation and Chronic Inflammation in Overweight Adults in a Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2021, 5, nzab006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Toll-like receptors in sepsis-associated cytokine storm and their endogenous negative regulators as future immunomodulatory targets. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 89, 107087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshimoghaddam, F.; Shateri, K.; Sina, M.; Hashemian, M.; Alizadeh, M. Daily Consumption of Synbiotic Yogurt Decreases Liver Steatosis in Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 1276–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loguercio, C.; Federico, A.; Tuccillo, C.; Terracciano, F.; D’Auria, M.V.; De Simone, C.; Del Vecchio Blanco, C. Beneficial Effects of a Probiotic VSL#3 on Parameters of Liver Dysfunction in Chronic Liver Diseases. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2005, 39, 540–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, H.; Mahmood, N.; Kumar, M.; Varikuti, S.R.; Challa, H.R.; Myakala, S.P. Effect of Probiotic (VSL#3) and Omega-3 on Lipid Profile, Insulin Sensitivity, Inflammatory Markers, and Gut Colonization in Overweight Adults: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Mediat. Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 348959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, S.Y.; Kang, S.-S.; Yun, C.-H.; Han, S.H. Lipoteichoic acid from Lactobacillus plantarum inhibits Pam2CSK4-induced IL-8 production in human intestinal epithelial cells. Mol. Immunol. 2015, 64, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duseja, A.; Acharya, S.K.; Mehta, M.; Chhabra, S.; Shalimar; Rana, S.; Das, A.; Dattagupta, S.; Dhiman, R.K.; Chawla, Y.K. High potency multistrain probiotic improves liver histology in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): A randomised, double-blind, proof of concept study. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2019, 6, e000315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.A.; Duarte, R.; Duarte, M.; Arella, F.; Marques, V.; Roos, S.; Rodrigues, C.M. Impact of Lactobacillaceae supplementation on the multi-organ axis during MASLD. Life Sci. 2024, 354, 122948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenz, E.; Montagut, N.E.; Wang, B.; Stein-Thöringer, C.; Wang, K.; Weng, H.; Ebert, M.; Schneider, K.M.; Li, L.; Teufel, A. Manipulating the Gut Microbiome to Alleviate Steatotic Liver Disease: Current Progress and Challenges. Engineering 2024, 40, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijangos-Trejo, A.; Nuño-Lambarri, N.; Barbero-Becerra, V.; Uribe-Esquivel, M.; Vidal-Cevallos, P.; Chávez-Tapia, N. Prebiotics and Probiotics: Therapeutic Tools for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastogi, S.; Singh, A. Gut microbiome and human health: Exploring how the probiotic genus Lactobacillus modulate immune responses. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1042189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.S.; Wang, J.; Yannie, P.J. Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction, LPS Translocation, and Disease Development. J. Endocr. Soc. 2020, 4, bvz039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didari, T.; Solki, S.; Mozaffari, S.; Nikfar, S.; Abdollahi, M. A systematic review of the safety of probiotics. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2014, 13, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, J.; Zhou, S.; Liao, J.; Ye, Z.; Mao, L. Efficacy of probiotics on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A meta-analysis. Medicine 2023, 102, e32734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rannikko, J.; Holmberg, V.; Karppelin, M.; Arvola, P.; Huttunen, R.; Mattila, E.; Kerttula, N.; Puhto, T.; Tamm, Ü.; Koivula, I.; et al. Fungemia and Other Fungal Infections Associated with Use of Saccharomyces boulardii Probiotic Supplements. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 2090–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerk, K.; Aguilera-Gómez, M. Microbiota analysis for risk assessment: Evaluation of hazardous dietary substances and its potential role on the gut microbiome variability and dysbiosis. EFSA J. 2022, 20, e200404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P.; Shadan, A.; Ma, Y. Biotechnological Applications of Probiotics: A Multifarious Weapon to Disease and Metabolic Abnormality. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2022, 14, 1184–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Olotu, T.; Ferrell, J.M. Lactobacillus sp. for the Attenuation of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease in Mice. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2488. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12122488

Olotu T, Ferrell JM. Lactobacillus sp. for the Attenuation of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease in Mice. Microorganisms. 2024; 12(12):2488. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12122488

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlotu, Titilayo, and Jessica M. Ferrell. 2024. "Lactobacillus sp. for the Attenuation of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease in Mice" Microorganisms 12, no. 12: 2488. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12122488

APA StyleOlotu, T., & Ferrell, J. M. (2024). Lactobacillus sp. for the Attenuation of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease in Mice. Microorganisms, 12(12), 2488. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12122488