GPU-Accelerated Data-Driven Surrogates for Transient Simulation of Tileable Piezoelectric Microactuators

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Contributions:

- A COMSOL-to-dataset pipeline that produces time-series trajectories spanning diverse voltage/traction waveforms.

- Two lightweight, GPU-optimized recursive sequence-to-sequence surrogate variants that predict displacement rollouts from short history windows.

- Evaluation on a holdout set showing strong fidelity across displacement channels and fast runtimes for a single actuator.

- Evaluation of surrogate runtime scaling; performing batched inference across multiple GPUs, yielding predictions for millions of actuators.

- Limitations of Analytical Modeling

2. Methodology

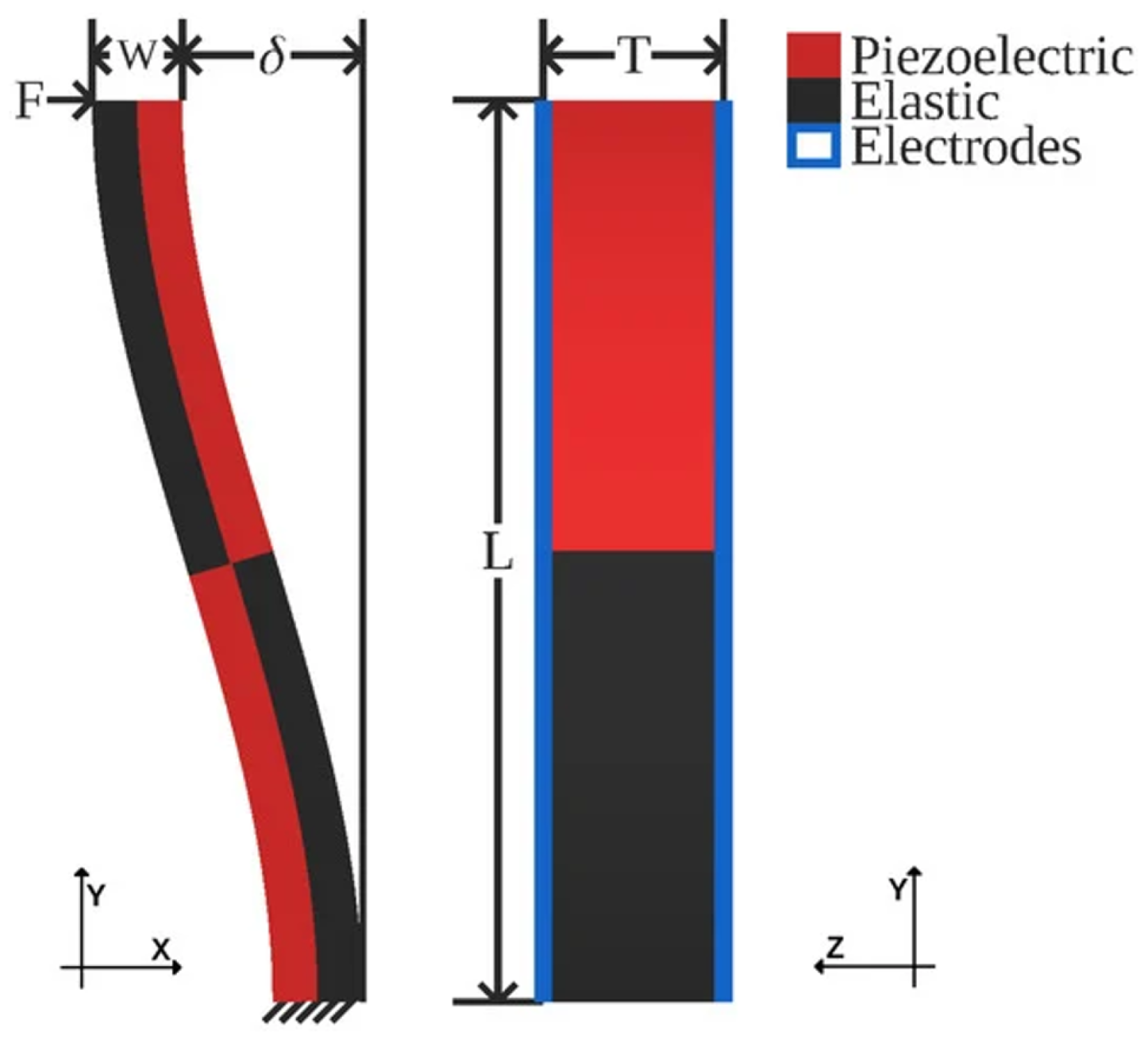

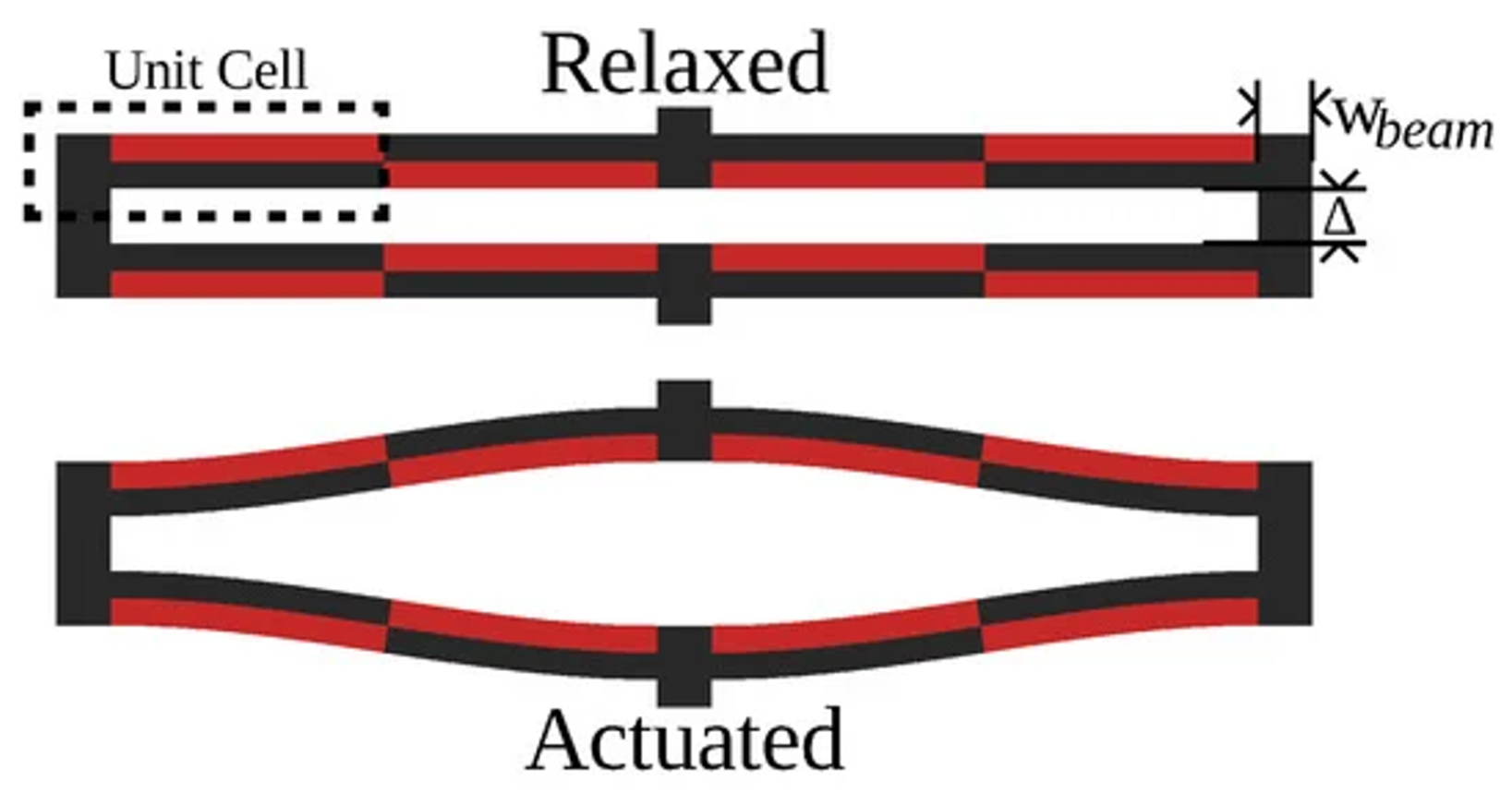

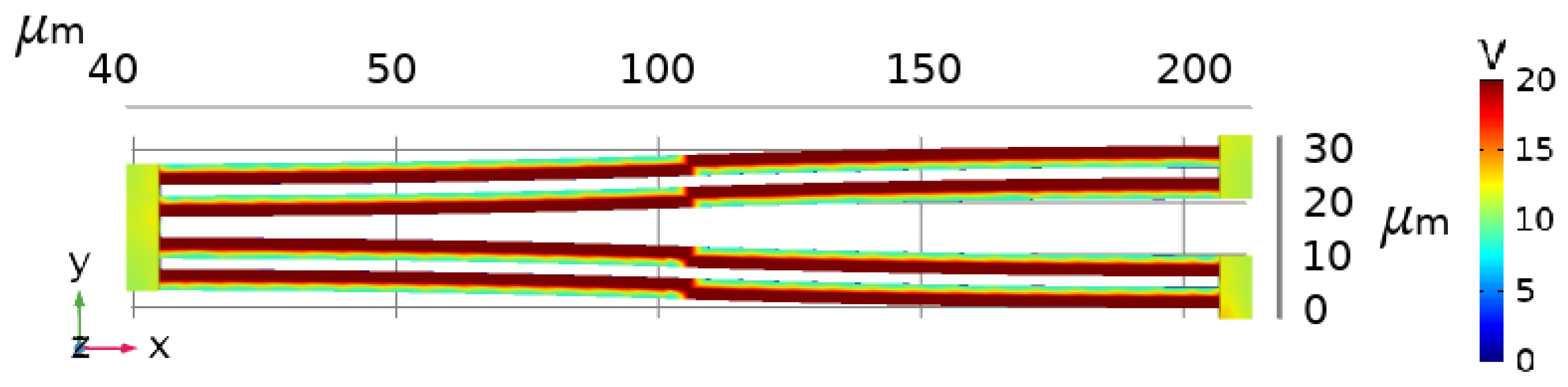

2.1. Actuator Design

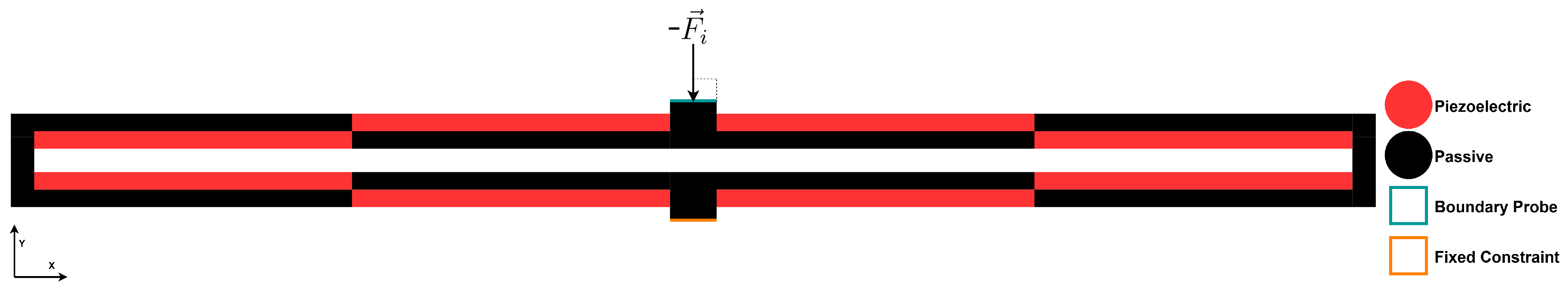

- 1.

- Fixed constraint: the exterior face of the fixed shuttle on the -plane is clamped.

- 2.

- Traction + Displacement Probe: the opposing shuttle’s exterior face is subjected to time-varying traction load, and its displacement is recorded via a boundary probe during solves.

- 3.

- Voltage Terminals: a checkerboarded terminal pattern applies voltage on the top electrodes (), and all bottom () surfaces are grounded.

2.2. Material Selection

2.3. Input Waveform Generation

- Voltage waveforms (11 families): pseudorandom binary sequences (PRBS); square-pulse trains with random pulse widths; multi-sine signals (sum of five sinusoids with random frequencies and phases); logarithmic-frequency chirps; triangular waves with random frequency; sawtooth waves with random frequency; random telegraph (two-state) processes; sparse impulse trains (short high-amplitude pulses); hold-then-step waveforms; amplitude-modulated sine waves and colored noise (white noise filtered by a moving-average filter).

- Force waveforms (12 families): pure sinusoidal waves with random frequency; linear ramps (increasing or decreasing); linear-frequency chirps; logarithmic-frequency chirps; piecewise-linear interpolations between randomly sampled anchor points; multi-sine signals (sum of five sinusoids); triangular waves with random frequency; sawtooth waves with random frequency; sparse impulse trains; hold-then-step waveforms; amplitude-modulated sine waves and colored noise.

2.4. Simulation Hyperparameters

- 1.

- Gaussian Noise (0–2500 ms),

- Time-Stepping Method: Backward Differentiation Formula (BDF) order 2;

- Relative Tolerance: ;

- Nonlinear Method: Constant (Newton);

- Nonlinear Method Maximum Iterations: 65;

- 2.

- Waveform Family Combinations (2500–5000 ms)

- Time-Stepping Method: Backward Differentiation Formula (BDF) order 1;

- Relative Tolerance: ;

- Nonlinear Method: Constant (Newton);

- Nonlinear Method Maximum Iterations: 20;

2.5. Transient FEA Simulations and Data Collection

2.6. Electromechanical Bounds

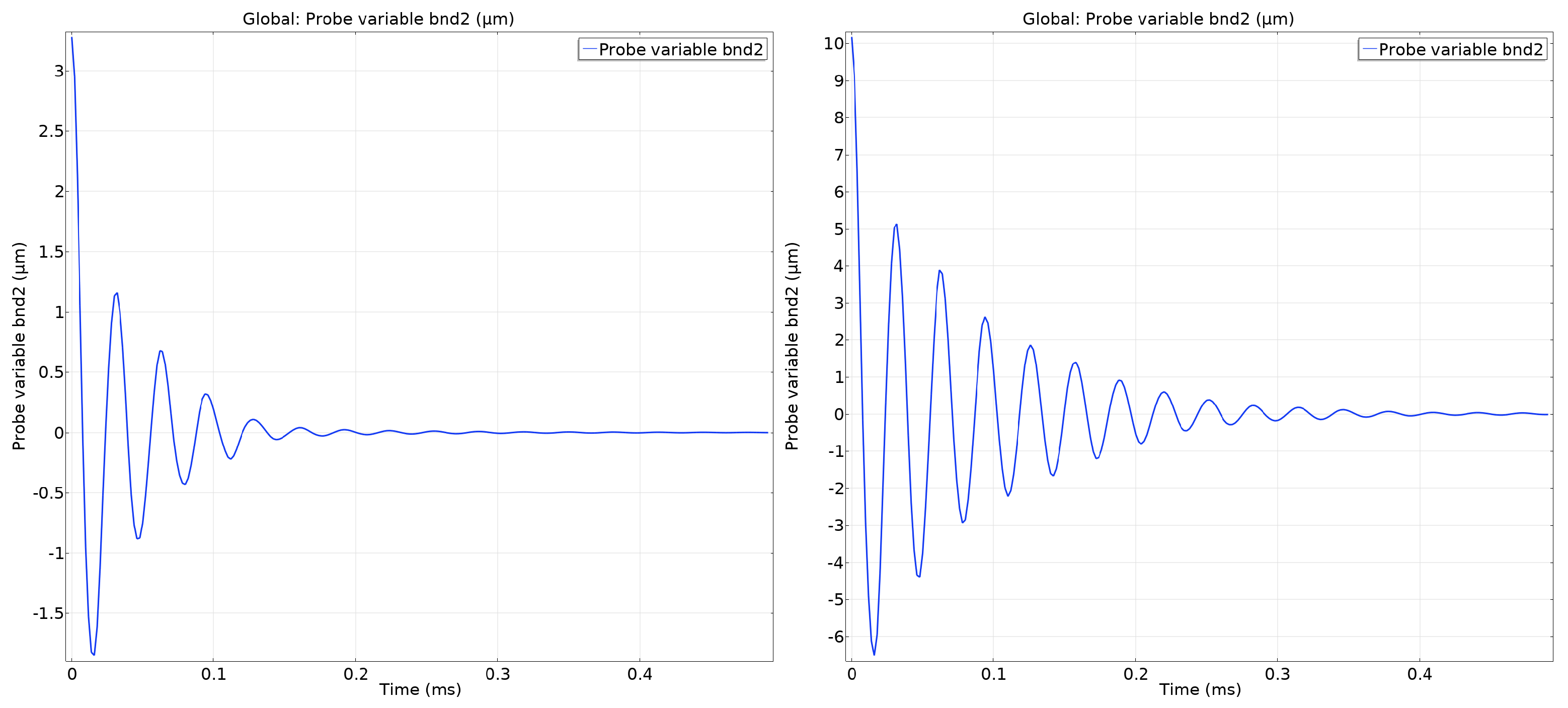

2.7. History Length via Ring-Down Analysis

2.8. Data Preprocessing

2.8.1. Training and Validation Splitting

- : (455453, 32, 5),

- : (455453, 100, 3),

- : (41405, 32, 5),

- : (41405, 100, 3).

2.8.2. Sliding-Window Sequence Generation

2.8.3. Feature Standardization

2.9. Surrogate Model Architecture

- a 2-layer GRU encoder that compresses the L-step input history into a stacked hidden state;

- a 2-layer GRU decoder that autoregressively generates H future displacement vectors conditioned on the encoder’s hidden state;

- and finally, a linear projection that maps the decoder hidden vectors to displacement outputs.

2.9.1. Dropout and Regularization

2.9.2. GRU Encoder

2.9.3. GRU Decoder

2.9.4. Loss Function and Optimization

2.10. Training Hyperparameters

3. Results

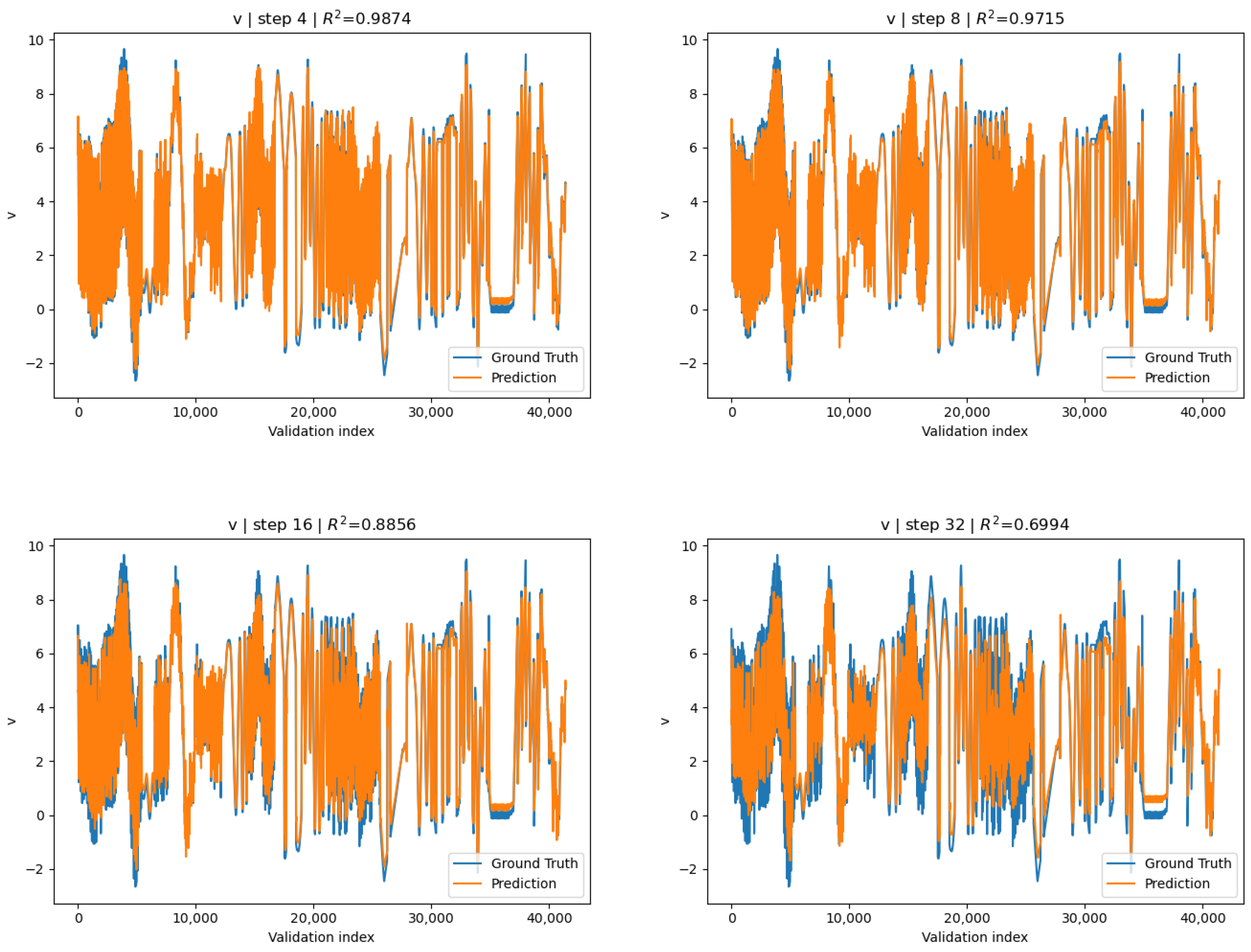

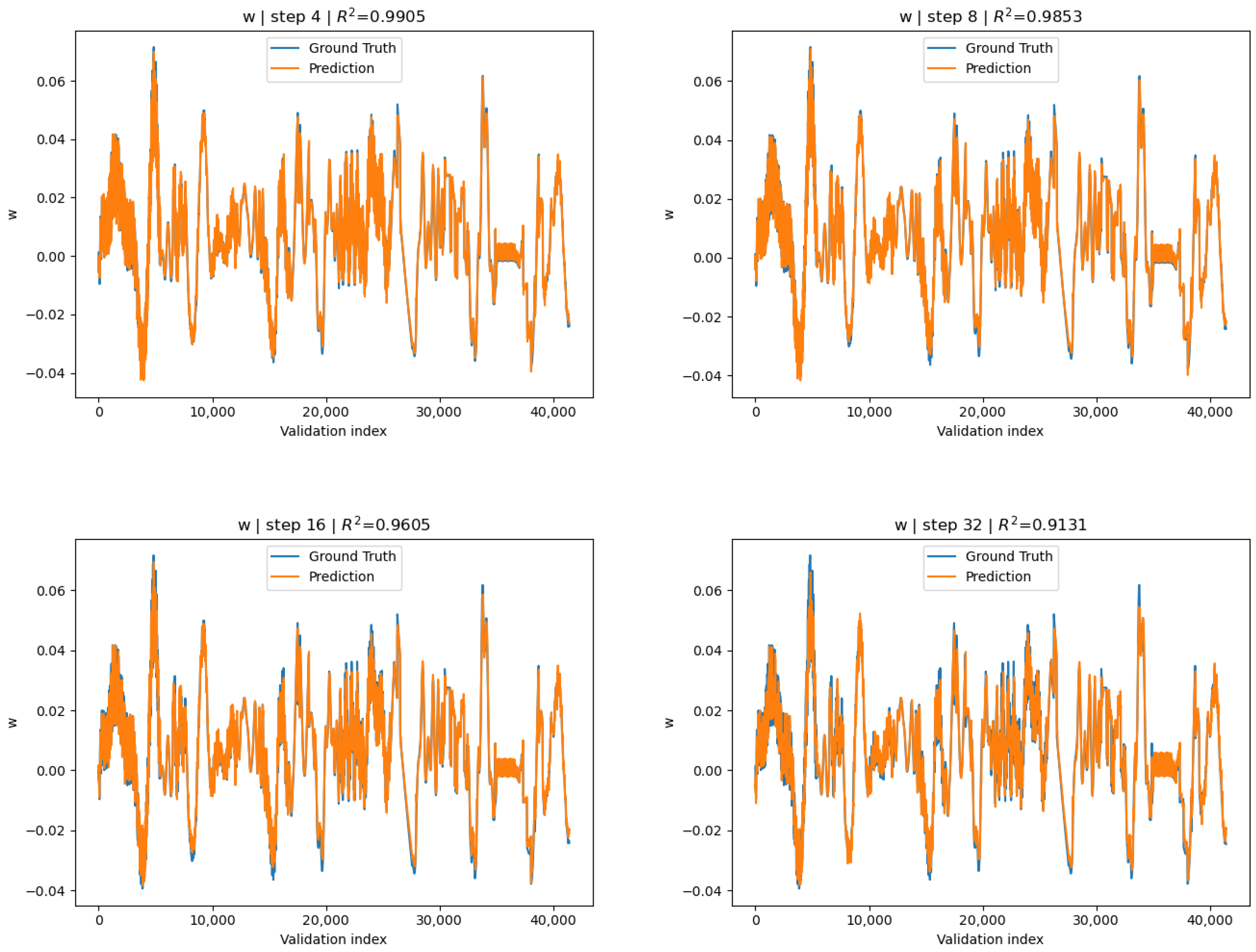

3.1. Surrogate Accuracy

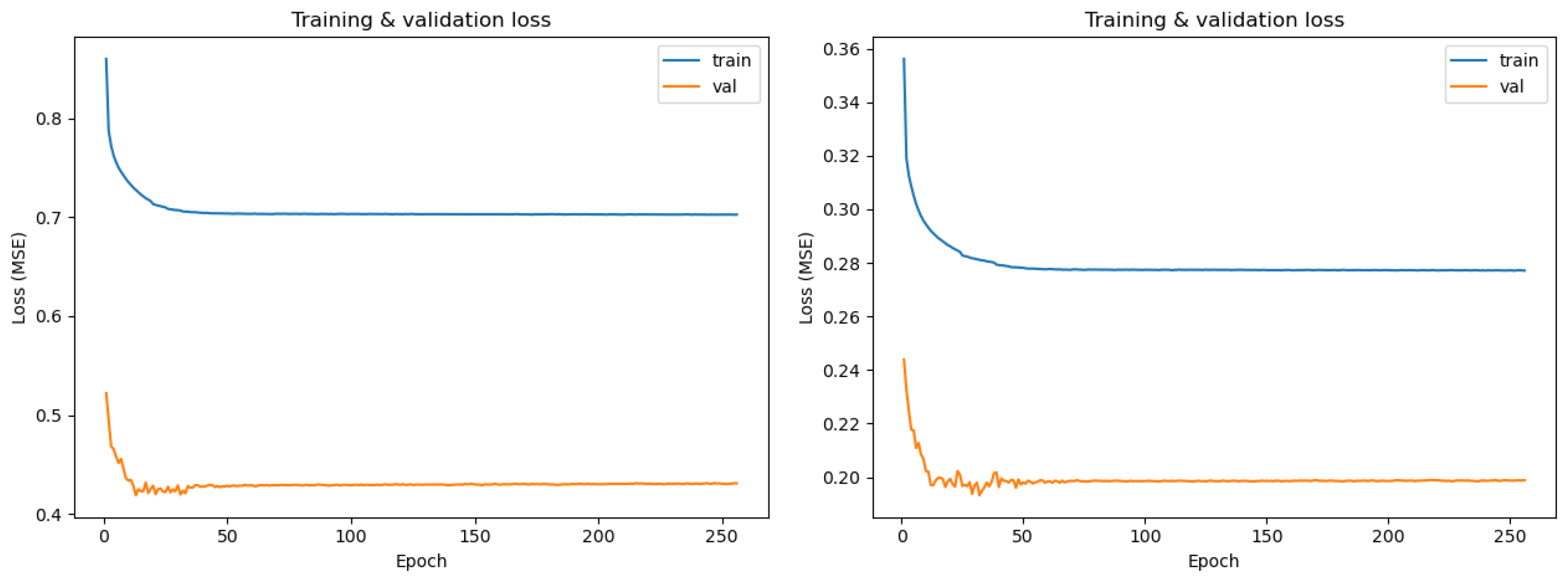

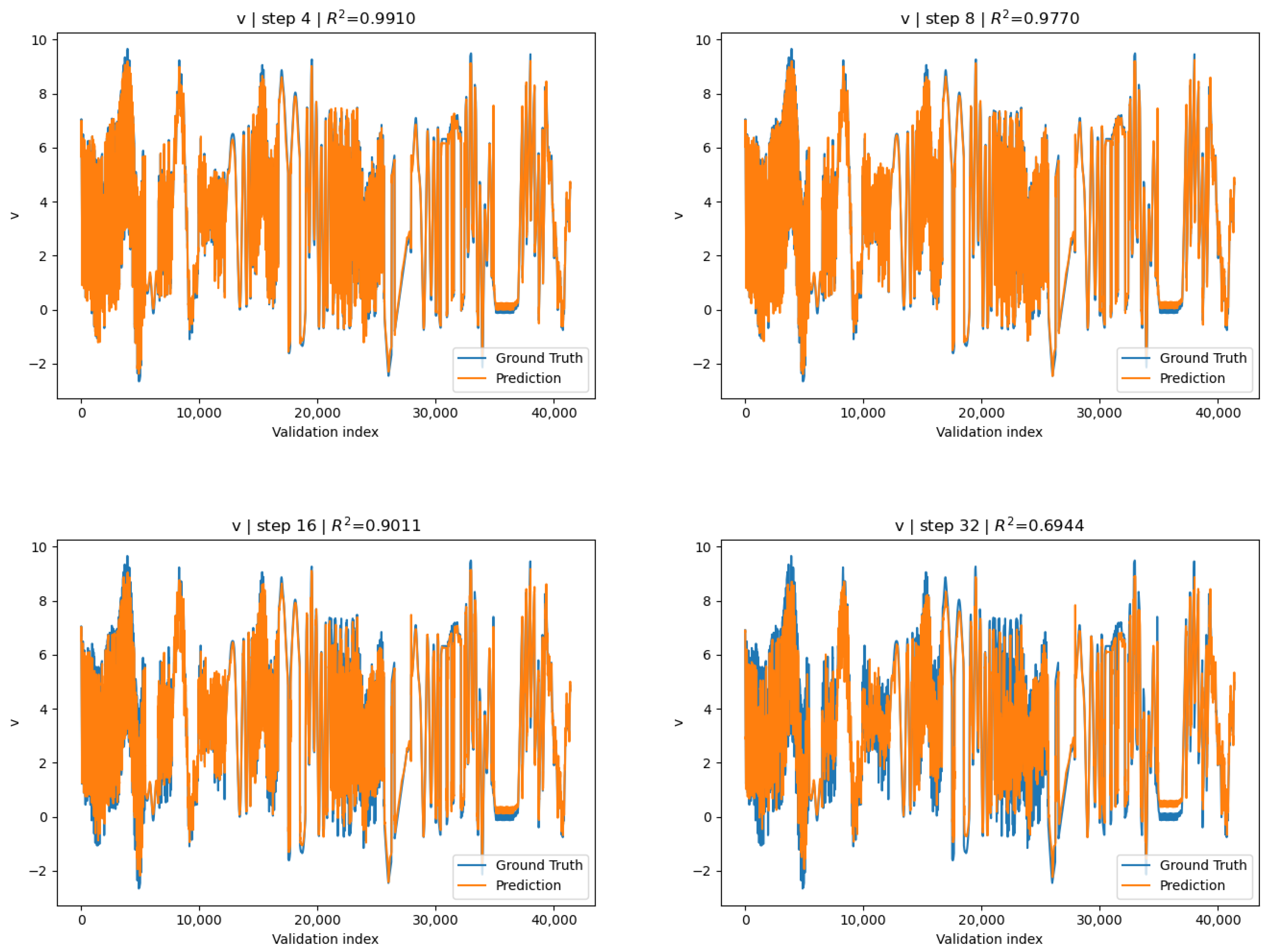

3.1.1. Globally Standardized Surrogate

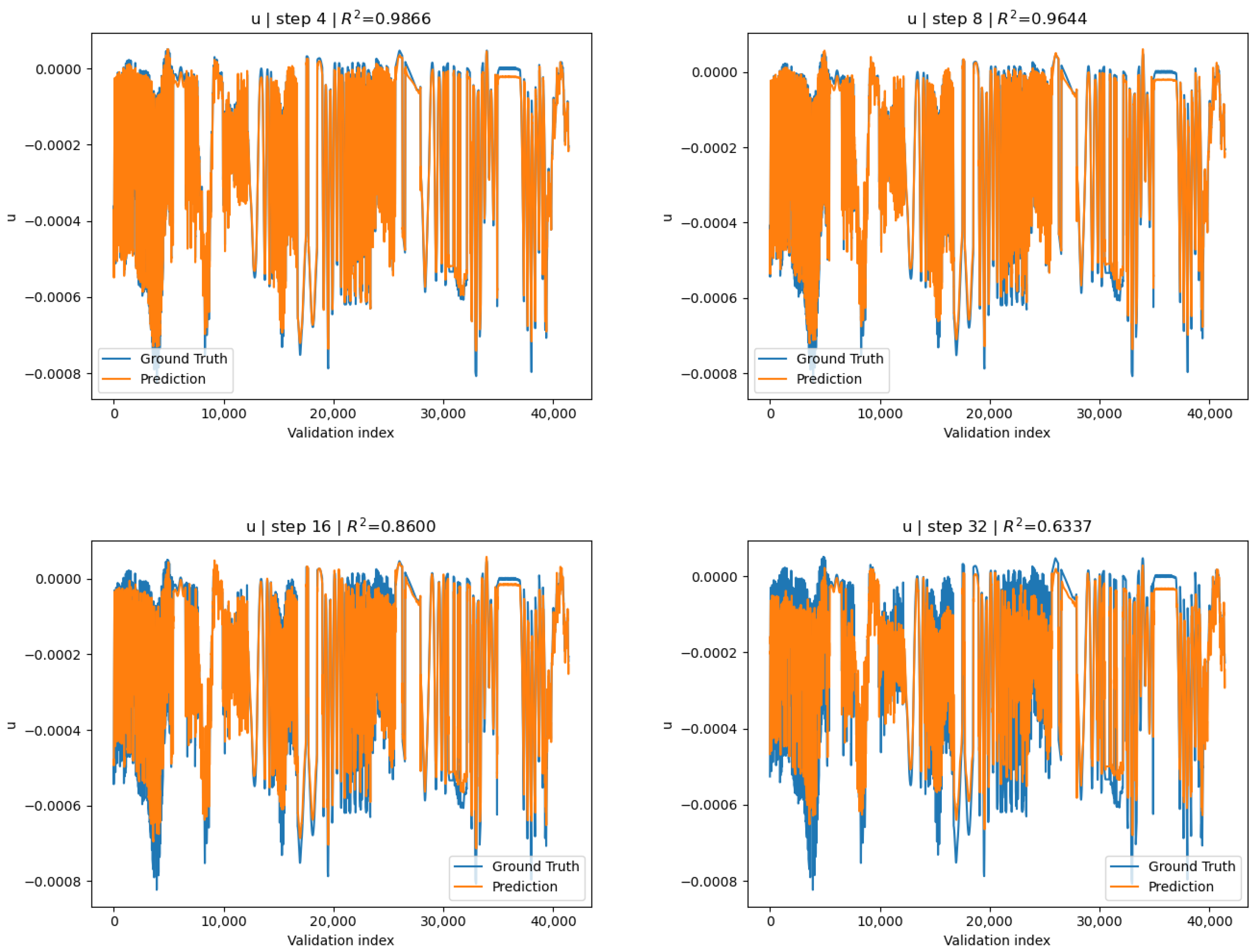

3.1.2. Channel-Wise Standardized Surrogate

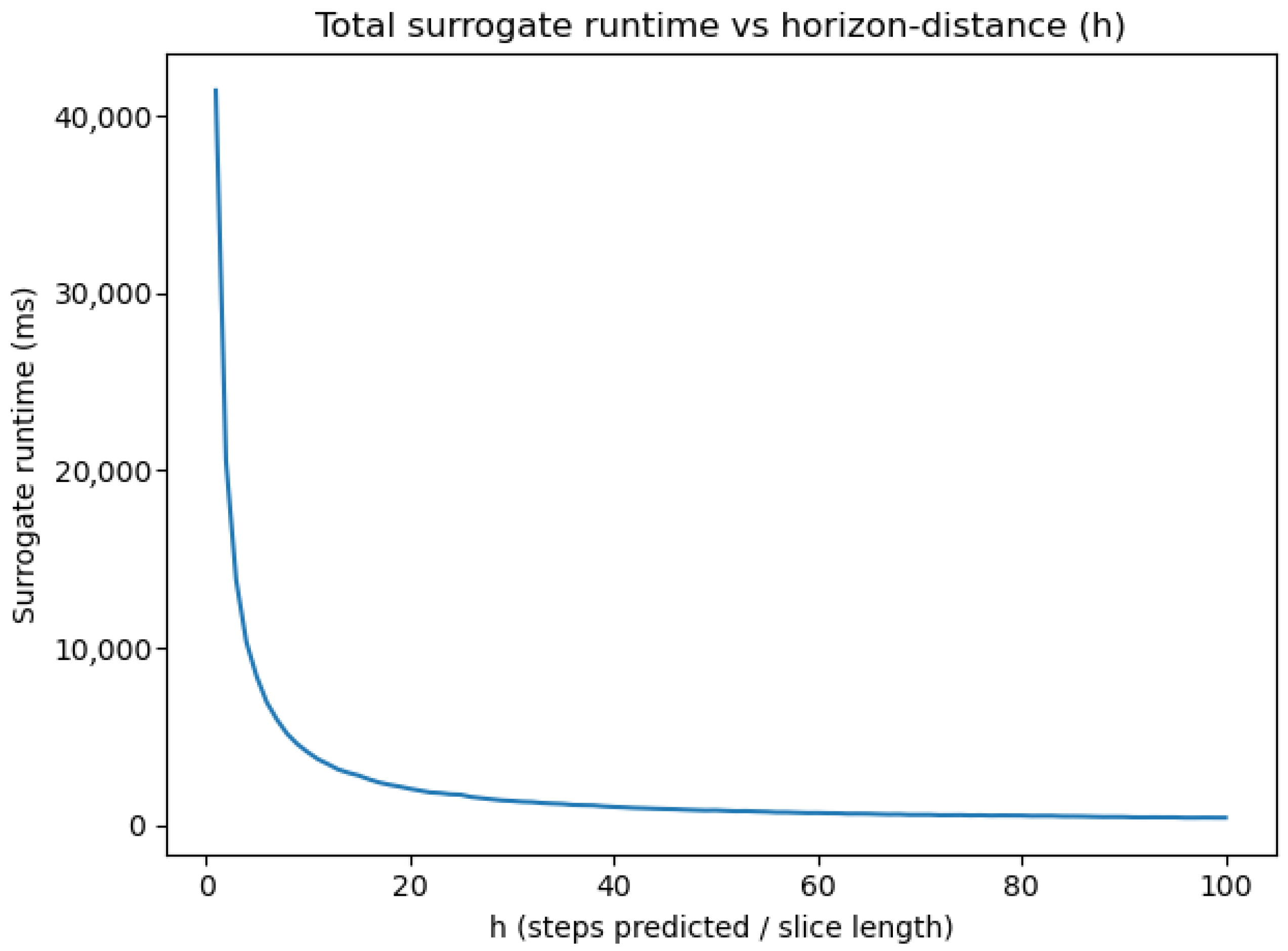

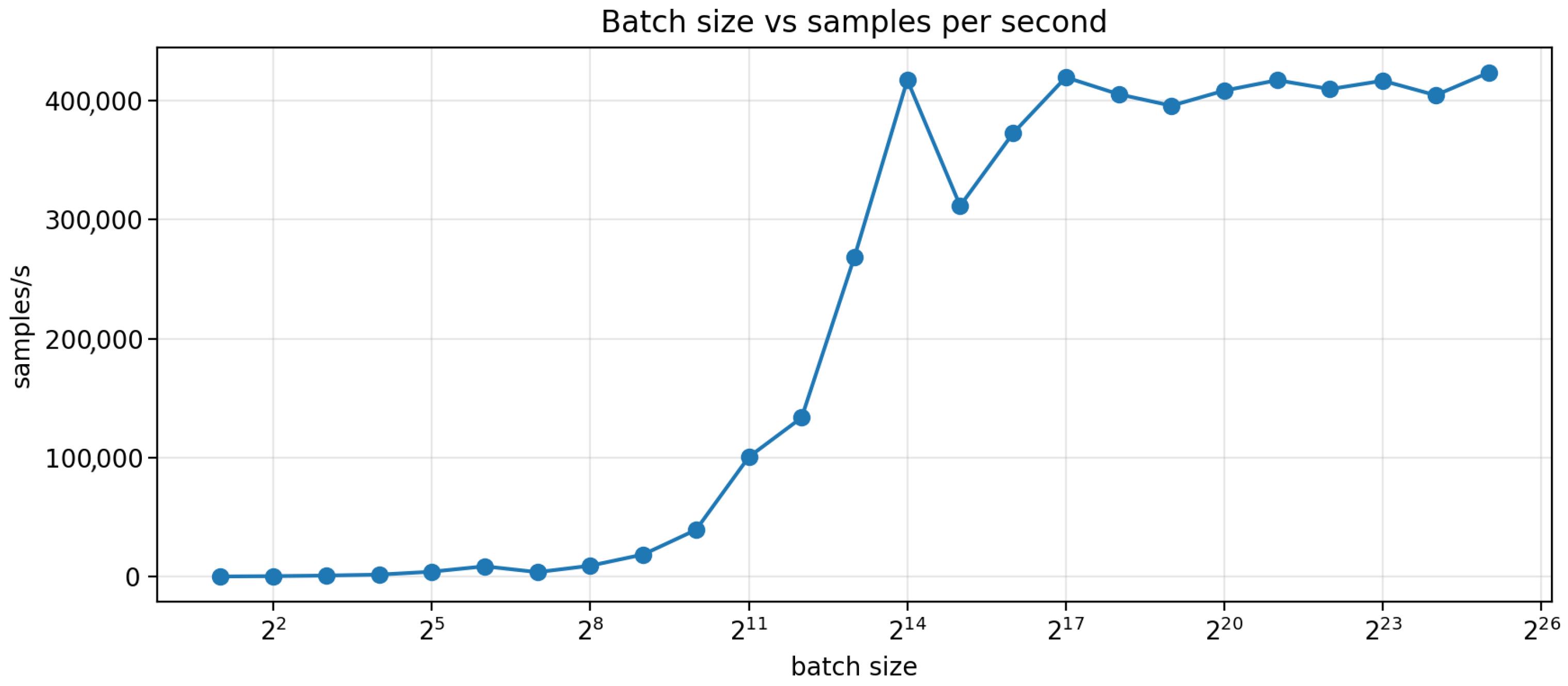

3.2. Surrogate Runtime Performance

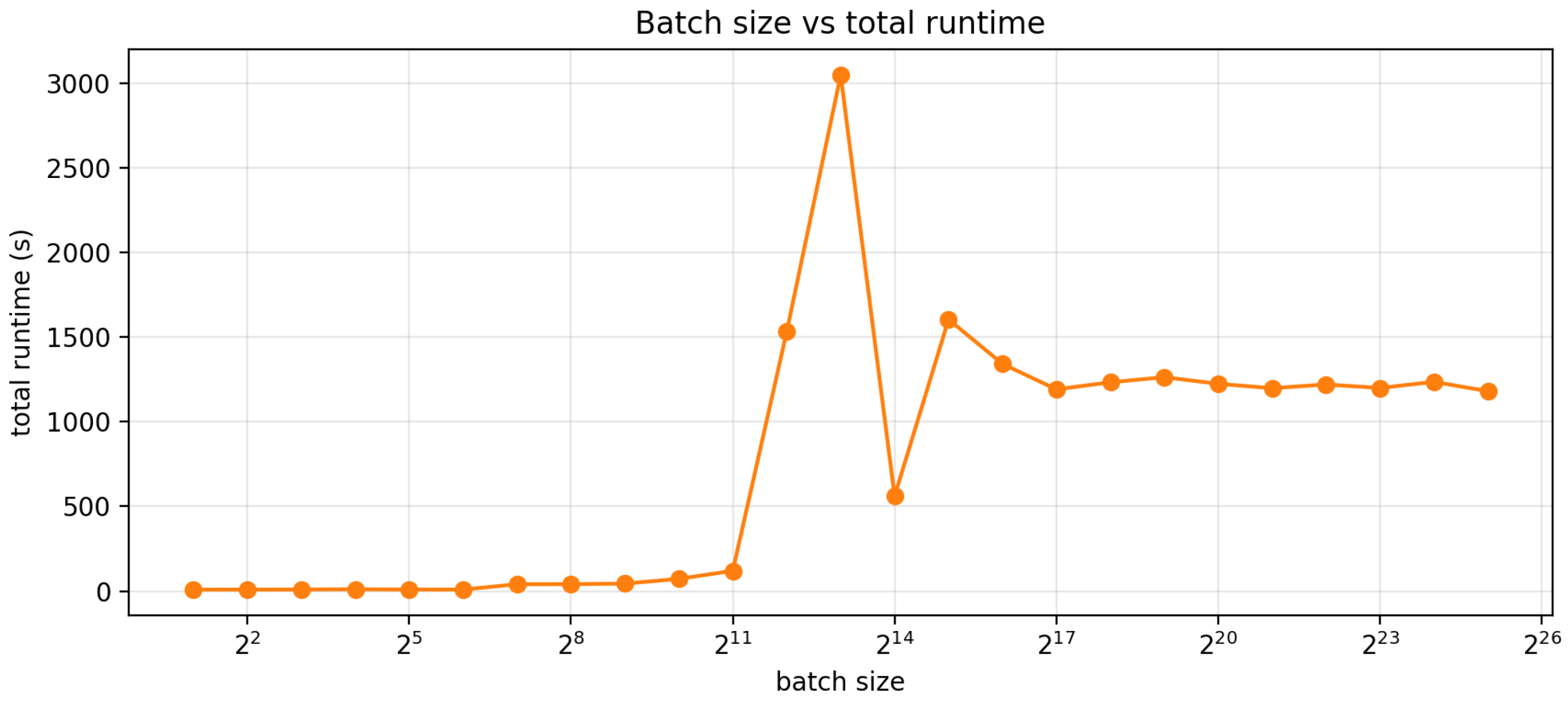

3.3. Multi-Surrogate Runtime Performance

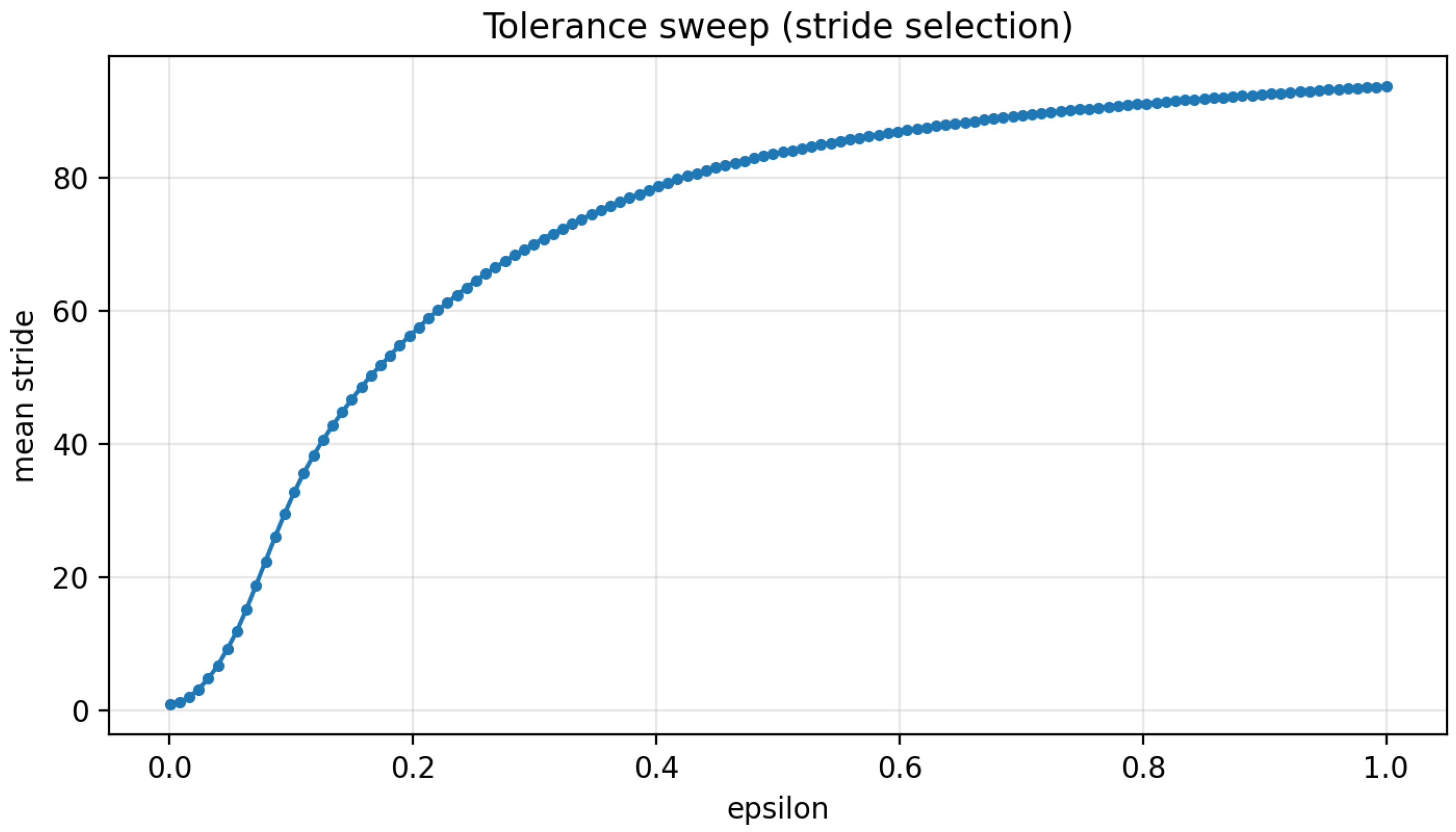

3.3.1. Tolerance-Driven Stride Selection

Purpose of Tolerance Driven Stride

3.3.2. Scaling Behavior: Throughput and Simulation Runtime

4. Discussion

Mechanical Coupling

- Lumped mass-spring-damper networks: By treating each actuator’s free shuttle as a node with 3 DOFs or just the v displacement channel, connect neighboring nodes with springs/dampers representing the compliant material between actuators. This network, in principle, could model the mechanical coupling between actuator-surrogate assemblies. Furthermore, it would scale linearly with the number of actuators and would exploit massive GPU parallelization.

- Skin/Plate Model: As seen in Figure 15 and Figure 16, the axial-configuration of the s-drive requires several actuators per layer. We can exploit this by treating each slice as a continuous layer where actuators apply point/patch loads and plate deformation gives back reaction forces on each actuator’s location.

- Coarse Global FEM + Localized Surrogates: Using a reduced-order structural mechanics model, for the whole array, each actuator represents an “active element” where the input-output laws are supplied by the surrogate, and the global solver enforces equilibrium. This surrogate-FEM middle-ground allows for iterative design through intuitive and user-friendly UI, superior scaling than that of full-FEA, and is massively accelerated by GPUs.

- Model-Based Reinforcement Learning (MBRL) Direct policy optimization on finite-element models is computationally prohibitive: single transient FEA simulations can take minutes, hours, or even days depending on model size and parameters, making the millions of interactions required by reinforcement learning infeasible. Despite the poor runtime with these models, they are greatly limited by how many degrees of freedom they need to solve, limiting them to smaller-scale assemblies. In contrast, our surrogate can serve as a component-wise dynamics model in an MBRL loop, making predictions in milliseconds, reducing runtimes significantly, and allowing for large-scale assemblies. This dramatic speedup, combined with a highly portable neural network, makes policy optimization practical for piezoelectric microactuator-based systems.

- Architecture Search Parker et al. demonstrated the feasibility of architecture search in piezoelectric microactuator design, performing systematic sweeps of electrode width, passive-region width, and layer thickness via finite-element analysis to identify geometries that maximize in-plane deflection [45]. Their study highlights the viability and importance of autonomous exploration of geometry search spaces on piezoelectric microactuator-based systems. While focusing on single s-drive optimization, a full-actuator surrogate could be used to accelerate optimization on actuator assemblies.Cheney et al. demonstrated that compositional-pattern-producing networks (CPPNs) combined with a library of various materials allow for the evolution of optimized morphologies for trivial tasks such as locomotion [46]. In theory, a similar approach could be applied by leveraging this surrogate framework, creating optimal geometries of microactuator-based robots for specific tasks.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rugar, D.; Hansma, P. Atomic Force Microscopy. Phys. Today 1990, 43, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bußmann, A.B.; Durasiewicz, C.P.; Kibler, S.H.A.; Wald, C.K. Piezoelectric titanium based microfluidic pump and valves for implantable medical applications. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2021, 323, 112649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangi, M.A.; Elahi, H.; Ali, A.; Jabbar, H.; Aqeel, A.B.; Farrukh, A.; Bibi, S.; Altabey, W.A.; Kouritem, S.A.; Noori, M. Applications of piezoelectric-based sensors, actuators, and energy harvesters. Sens. Actuators Rep. 2025, 9, 100302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigullapalli, A.; Clark, J.V. Extremely Large Deflection Actuators for Translation or Rotation. In Volume 9: Micro- and Nano-Systems Engineering and Packaging, Parts A and B; ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition; ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.A.; Clark, J. Analytical Modeling and Simulation of S-Drive Piezoelectric Actuators. Actuators 2021, 10, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulos, S.; Kalogeris, I.; Papadopoulos, V. Non-intrusive Surrogate Modeling for Parametrized Time-dependent PDEs using Convolutional Autoencoders. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.05555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohar, C.P.; Greve, L.; Eller, T.K.; Connolly, D.S.; Inal, K. A machine learning framework for accelerating the design process using CAE simulations: An application to finite element analysis in structural crashworthiness. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2021, 385, 114008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, G.; Peng, L.; Hu, L. A Gaussian process-based dynamic surrogate model for complex engineering structural reliability analysis. Struct. Saf. 2017, 68, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meethal, R.E.; Obst, B.; Khalil, M.; Ghantasala, A.; Kodakkal, A.; Bletzinger, K.U.; Wüchner, R. Finite Element Method-enhanced Neural Network for Forward and Inverse Problems. Adv. Model. Simul. Eng. Sci. 2023, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Hou, D.; Cao, W.; Huang, X. Composite Data Driven-Based Adaptive Control for a Piezoelectric Linear Motor. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 3527912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarem, S.; Delibas, B.; Koc, B. Data-Driven Tuning of PID Controlled Piezoelectric Ultrasonic Motor. Actuators 2021, 10, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigullapalli, A. Modeling and Validation of S-Drive: A Nestable Piezoelectric Actuator. Ph.D. Thesis, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- PolyK Technologies. 8 µm Thick Piezo PVDF Film with 30 nm Thick Aluminum Electrode. 2026. Available online: https://piezopvdf.com/8-um-pvdf-film-aluminum-electrode/ (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- PolyK Technologies. PVDF Poled Piezoelectric Film, 120 mm × 120 mm, Platinum Electrode Both Surfaces, Uniaxially Oriented with High d31. 2026. Available online: https://piezopvdf.com/pvdf-piezo-Pt/ (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Hake, A.E.; Zhao, C.; Sung, W.K.; Grosh, K. Design and Experimental Assessment of Low-Noise Piezoelectric Microelectromechanical Systems Vibration Sensors. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 17703–17711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, M.W. Properties of PZT-Based Piezoelectric Ceramics Between − 150 and 250 C. 1998. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/19980236888 (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- PIEZO.COM. PZT5A & 5H Materials Technical Data (Typical Values). Available online: https://info.piezo.com/hubfs/Data-Sheets/piezo-PZT-5A_PZT-5H-material-properties.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, J.; Yao, W.; Liu, D.; He, G. Remarkably strong piezoelectricity, rhombohedral-orthorhombic-tetragonal phase coexistence and domain structure of (K,Na)(Nb,Sb)O3–(Bi,Na)ZrO3–BaZrO3 ceramics. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 820, 153411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raul Alin, B.; Badea, I.; Bucur, A.I.; Novaconi, S. Good Quality Factor in GdMnO3-Doped (K0.5Na0.5)NbO3 Piezoelectric Ceramics. J. Electron. Mater. 2016, 45, 3046–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Hou, Y.; Chao, L.; Zhu, M. Piezoelectric KNN ceramic for energy harvesting from mechanochemically activated precursors. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2018, 29, 9582–9587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadwal, N.; Ben Mrad, R.; Behdinan, K. Review of Piezoelectric Properties and Power Output of PVDF and Copolymer-Based Piezoelectric Nanogenerators. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Zhang, Z. PVDF-based dielectric polymers and their applications in electronic materials. IET Nanodielectr. 2018, 1, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleb, S.; Badillo-Ávila, M.A.; Acuautla, M. Fabrication of poly (vinylidene fluoride) films by ultrasonic spray coating; uniformity and piezoelectric properties. Mater. Des. 2021, 212, 110273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.F. Lead-Free Piezoelectric Materials; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Tang, E.; Yang, G.; Han, Y.; Chen, C. Discharge characteristics of fractured soft piezoelectric ceramics under repeated impact. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 23499–23504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Tang, E.; Yang, G.; Han, Y. Experimental research on dynamic response of PZT-5H under impact load. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 2868–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Gülçehre, Ç.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Empirical Evaluation of Gated Recurrent Neural Networks on Sequence Modeling. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.0376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brohan, A.; Brown, N.; Carbajal, J.; Chebotar, Y.; Chen, X.; Choromanski, K.; Ding, T.; Driess, D.; Dubey, A.; Finn, C.; et al. RT-2: Vision-Language-Action Models Transfer Web Knowledge to Robotic Control. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.15818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, A.T.; Gaitonde, D.V. A Deep Learning based Approach to Reduced Order Modeling for Turbulent Flow Control using LSTM Neural Networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.09269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, R.; Damodaran, M.; Cheong, K.B. Deep Learning-Driven Nonlinear Reduced-Order Models for Predicting Wave-Structure Interaction. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.11835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.E.; San, O.; Rasheed, A.; Iliescu, T. A long short-term memory embedding for hybrid uplifted reduced order models. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2020, 409, 132471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzara, M.; Chevalier, M.; Colombo, M.; Garay Garcia, J.; Lapeyre, C.; Teste, O. Surrogate modelling for an aircraft dynamic landing loads simulation using an LSTM AutoEncoder-based dimensionality reduction approach. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 126, 107629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, H.; Cotteleer, L.; Parente, A. Physics-informed non-intrusive reduced-order modeling of parameterized dynamical systems. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2025, 443, 118045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Faverjon, B.; Peters, H.; Kessissoglou, N. Application of Polynomial Chaos Expansion and Model Order Reduction for Dynamic Analysis of Structures with Uncertainties. Procedia IUTAM 2015, 13, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensman, J.; Fusi, N.; Lawrence, N.D. Gaussian Processes for Big Data. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1309.6835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Allen, M.S. A Gaussian process regression reduced order model for geometrically nonlinear structures. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 184, 109720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobat, G.; Opreni, A.; Fresca, S.; Manzoni, A.; Frangi, A. Reduced order modeling of nonlinear microstructures through Proper Orthogonal Decomposition. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 171, 108864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatpattanasiri, C.; Franzetti, G.; Bonfanti, M.; Diaz-Zuccarini, V.; Balabani, S. Towards Reduced Order Models via Robust Proper Orthogonal Decomposition to capture personalised aortic haemodynamics. J. Biomech. 2023, 158, 111759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Bindel, D.; Clark, J.; Demmel, J.; Pister, K.; Zhou, N. New numerical techniques and tools in SUGAR for 3D MEMS simulation. In Proceedings of the Fourth Technical International Conference on Modeling and Simulation of Microsystems, Hilton Head Island, SC, USA, 19–21 March 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Padoan, A.; Forni, F.; Sepulchre, R. Balanced truncation for model reduction of biological oscillators. Biol. Cybern. 2021, 115, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megginson, P.; Clark, J.; Clarson, R. Optimizing the Electrode Geometry of an In-Plane Unimorph Piezoelectric Microactuator for Maximum Deflection. Modelling 2024, 5, 1084–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheney, N.; MacCurdy, R.; Clune, J.; Lipson, H. Unshackling Evolution: Evolving Soft Robots with Multiple Materials and a Powerful Generative Encoding. In Proceedings of the 15th Annual Conference on Genetic and Evolutionary Computation, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 6–10 July 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Governing Equations | Online Runtime Complexity | Generalization | Limitations | Examples and Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTMs) | No; data-driven, non-intrusive | ; (fixed architecture) | Moderate; typically strong within training envelope | Requires extensive and diverse data; training cost | Fluid Dynamics [32,33,34]; Aircraft landing load simulations [35] |

| Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) | No; residuals only needed for training | ; (fixed architecture) | Strong; physics residual helps with unseen inputs, typically strong within the operational envelope of the training data | Training cost; retraining per problem | Non-Intrusive ROM of parameterized dynamic systems [36] |

| Polynomial Chaos Expansion (PCE) | No; statistical basis expansion | ; (fixed architecture) | Moderate; weak outside design/ parameter space, stronger within | Curse of dimensionality | Dynamic analysis of structures with uncertainties [37] |

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) | No; nonparametric regression on data | ≈(M) (Sparse Variational GP) [38] | Moderate; Strong in-range, extrapolation trends to the kernel’s mean | Poor scaling with dataset size, curse of dimensionality, kernel sensitivity | ROM of geometrically nonlinear structures [39] |

| Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD-Galerkin) | Yes; projection onto basis | (Implicit); (Explicit) | Weak; limited to snapshot manifold, otherwise typically moderate-strong | Poor for highly nonlinear problems (without augmentation) | Microstructure modeling [40]; Blood-flow modeling [41] |

| Krylov Subspace Methods | Yes; projection of governing equations | (Implicit); (Explicit) | Moderate; typically strong for linear systems but weak under nonlinearity | Requires full system matrices; | Nodal analysis for MEMS simulations [42] |

| Balanced Truncation | Yes; needs full state-space matrices | (Implicit); (Explicit) | Typically Moderate | Can struggle with nonlinear dynamics (without augmentation) | Biological oscillator simulations [43] |

| h | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.9926 | ||

| 2 | 0.9940 | ||

| 4 | 0.9910 | ||

| 8 | 0.9770 | ||

| 16 | 0.9012 | ||

| 32 | 0.6944 | ||

| 64 | 0.5670 | ||

| 100 | 0.4501 |

| Channel | Min | Max | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| u | μm | μm | μm |

| v | μm | μm | μm |

| w | μm | μm | μm |

| h | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.9877 | 0.9863 | 0.9803 |

| 2 | 0.9918 | 0.9898 | 0.9889 |

| 4 | 0.9867 | 0.9874 | 0.9906 |

| 8 | 0.9647 | 0.9716 | 0.9854 |

| 16 | 0.8601 | 0.8857 | 0.9608 |

| 32 | 0.6337 | 0.6996 | 0.9132 |

| 64 | 0.4521 | 0.5626 | 0.8531 |

| 100 | 0.3128 | 0.4441 | 0.7764 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Scumniotales, J.; Clark, J.; Tran, D. GPU-Accelerated Data-Driven Surrogates for Transient Simulation of Tileable Piezoelectric Microactuators. Actuators 2026, 15, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15020094

Scumniotales J, Clark J, Tran D. GPU-Accelerated Data-Driven Surrogates for Transient Simulation of Tileable Piezoelectric Microactuators. Actuators. 2026; 15(2):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15020094

Chicago/Turabian StyleScumniotales, John, Jason Clark, and Daniel Tran. 2026. "GPU-Accelerated Data-Driven Surrogates for Transient Simulation of Tileable Piezoelectric Microactuators" Actuators 15, no. 2: 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15020094

APA StyleScumniotales, J., Clark, J., & Tran, D. (2026). GPU-Accelerated Data-Driven Surrogates for Transient Simulation of Tileable Piezoelectric Microactuators. Actuators, 15(2), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15020094