Liquid Crystal Elastomer Microfiber Actuators Prepared by Melt-Centrifugal Technology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

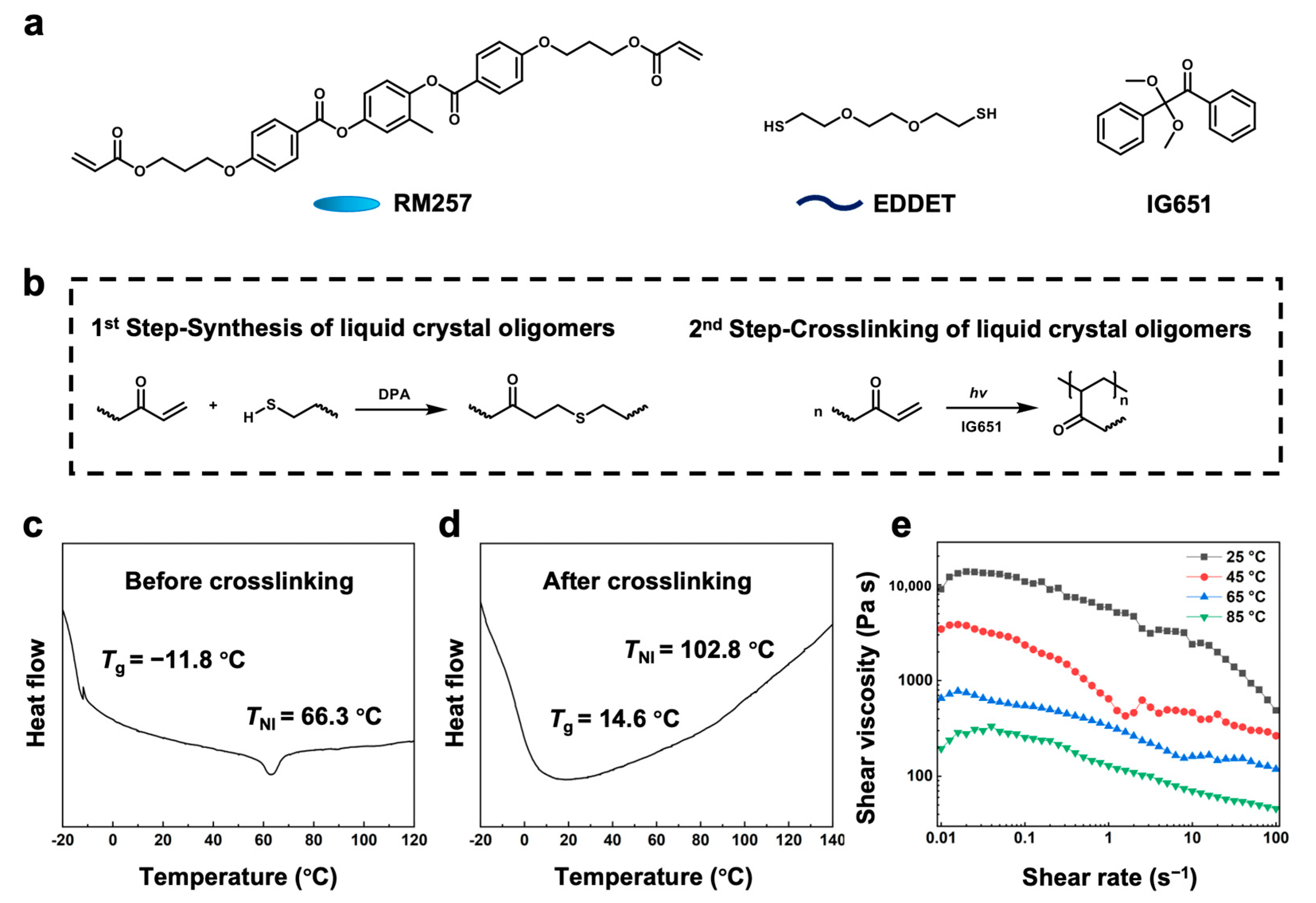

2.1. Synthesis of Liquid Crystal (LC) Oligomer Ink

2.2. Melt-Centrifugal Spinning Procedure

2.3. Characterization of LCE Microfibers

2.3.1. Morphology and Anisotropy

2.3.2. Thermal Response to Deformation

2.4. Actuator Demonstrations

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Melt-Centrifugal Spinning of LCE Microfibers

3.2. Effect of Collection Distance, Rotational Speed and Nozzle Diameter on LCE Microfibers

3.3. Mechanistic Analysis of Jet Stabilization and Fiber Formation

3.4. Thermally Induced Actuation of LCE Microfibers

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dong, K.; Peng, X.; Wang, Z.L. Fiber/fabric-based piezoelectric and triboelectric nanogenerators for flexible/stretchable and wearable electronics and artificial intelligence. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1902549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Chen, J.; Lee, P.S. Functional fibers and fabrics for soft robotics, wearables, and human–robot interface. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2002640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Xu, B.; Li, M.; Han, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X. Advanced design of fibrous flexible actuators for smart wearable applications. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2024, 6, 622–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Y.; Leng, J. Smart polymer fibers: Promising advances in microstructures, stimuli-responsive properties and applications. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2025, 7, 1010–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yang, Z. Smart liquid crystal elastomer fibers. Matter 2025, 8, 101950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, L.; Petersen, K.; Lum, G.Z.; Sitti, M. Soft actuators for small-scale robotics. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1603483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotikian, A.; Truby, R.L.; Boley, J.W.; White, T.J.; Lewis, J.A. 3D printing of liquid crystal elastomeric actuators with spatially programed nematic order. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1706164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, W.; Khan, M.T.A.; Sitti, M. Shape-programmable liquid crystal elastomer structures with arbitrary three-dimensional director fields and geometries. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, B.; Liu, G.; Zhang, M.; Tatoulian, M.; Keller, P.; Li, M.-H. Customizable sophisticated three-dimensional shape changes of large-size liquid crystal elastomer actuators. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 54439–54446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Wang, J.; Lv, J. Bioinspired liquid crystalline spinning enables scalable fabrication of high-performing fibrous artificial muscles. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2211800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terentjev, E.M. Liquid crystal elastomers: 30 years after. Macromolecules 2025, 58, 2792–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Lee, M.; Park, T.; Wang, Y.; Lee, H.; Cai, S.; Park, Y. Bio-inspired artificial muscle-tendon complex of liquid crystal elastomer for bidirectional afferent-efferent signaling. Adv. Mater. 2025, 38, e03094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Broer, D.J. Programmable and adaptive mechanics with liquid crystal polymer networks and elastomers. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 1087–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, K.M.; Fowler, H.E.; McCracken, J.M.; Schlafmann, K.R.; Koch, J.A.; White, T.J. Synthesis and alignment of liquid crystalline elastomers. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 7, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Tong, D.; Meng, L.; Tan, B.; Lan, R.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, H.; Wang, C.; Liu, K. Knotted artificial muscles for bio-mimetic actuation under deepwater. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2400763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Annapooranan, R.; Zeng, J.; Chen, R.; Cai, S. Electrospun liquid crystal elastomer microfiber actuator. Sci. Robot. 2021, 6, eabi9704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Chung, C.; Dunn, M.L.; Yu, K. 4D printing of liquid crystal elastomer composites with continuous fiber reinforcement. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, M.C.; White, T.J. Fast and slow-twitch actuation via twisted liquid crystal elastomer fibers. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2401140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naciri, J.; Srinivasan, A.; Jeon, H.; Nikolov, N.; Keller, P.; Retna, B.R. Nematic elastomer fiber actuator. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 8499–8505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocentini, S.; Martella, D.; Wiersma, D.S.; Parmeggiani, C. Beam steering by liquid crystal elastomer fibres. Soft Matter 2017, 13, 8590–8596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelebart, A.H.; Mc Bride, M.; Schenning, A.P.H.J.; Bowman, C.N.; Broer, D.J. Photoresponsive fiber array: Toward mimicking the collective motion of cilia for transport applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 5322–5327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Saed, M.O.; Terentjev, E.M. Continuous spinning aligned liquid crystal elastomer fibers with a 3D printer setup. Soft Matter 2021, 17, 5436–5443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrossamay, M.R.; McIlwee, H.A.; Goss, J.A.; Parker, K.K. Nanofiber assembly by rotary jet-spinning. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 2257–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihova, M.; Lepcio, P.; Cicmancova, V.; Frumarova, B.; Hromádko, L.; Bureš, F.; Vojtová, L.; Macak, J.M. The centrifugal spinning of vitamin doped natural gum fibers for skin regeneration. Carbohyd. Polym. 2022, 294, 119792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Qu, W.; Yu, R.; Tong, W.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M. Aligned triboelectric dipoles in fiber structure via centrifugal spinning for airflow sensing. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 524, 169302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannini Luz, H.; Loureiro Dos Santos, L.A. Centrifugal spinning for biomedical use: A review. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2023, 48, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Yagi, S.; Ashour, S.; Du, L.; Hoque, M.E.; Tan, L. A review on current nanofiber technologies: Electrospinning, centrifugal spinning, and electro-centrifugal spinning. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2023, 308, 2200502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Lyu, J.; Ding, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhang, X. Aerogel fibers made via generic sol-gel centrifugal spinning strategy enable dynamic removal of volatile organic compounds from high-flux gas. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2407221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Yang, Z. The integration of sensing and actuating based on a simple design fiber actuator towards intelligent soft robots. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2022, 7, 2101260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, S.; Dersch, R.; Wendorff, J.H.; Finkelmann, H. Photocrosslinkable liquid crystal main-chain polymers: Thin films and electrospinning. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2007, 28, 2062–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, X.; Long, Z.; Ren, L.; Xia, X.; Wang, Q.; Li, J.; Lv, P.; et al. Novel biomimetic “spider web” robust, super-contractile liquid crystal elastomer active yarn soft actuator. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2400557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reneker, D.H.; Yarin, A.L. Electrospinning jets and polymer nanofibers. Polymer 2008, 49, 2387–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, A.P.; Ng, A.; Nah, S.H.; Yang, S. Active-textile yarns and embroidery enabled by wet-spun liquid crystalline elastomer filaments. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2400742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Feng, J. High-strength and fast-response liquid crystal elastomer fiber and fabric actuators. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 46161–46171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javadzadeh, M.; Del Barrio, J.; Sánchez-Somolinos, C. Melt Electrowriting of liquid crystal elastomer scaffolds with programmed mechanical response. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2209244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohm, C.; Morys, M.; Forst, F.R.; Braun, L.; Eremin, A.; Serra, C.; Stannarius, R.; Zentel, R. Preparation of actuating fibres of oriented main-chain liquid crystalline elastomers by a wetspinning process. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Wang, L.; Xue, Z.; Xie, C.; Han, J.; Pei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, W.; Lu, B. Melt electrowriting enabled 3D liquid crystal elastomer structures for cross-scale actuators and temperature field sensors. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gao, Y.; Wang, H.; Poling-Skutvik, R.; Osuji, C.O.; Yang, S. Shaping and locomotion of soft robots using filament actuators made from liquid crystal elastomer–carbon nanotube composites. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2020, 2, 1900163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Li, K.; Lin, Y.; Lu, C.; Duan, X. Characterization techniques of polymer aging: From beginning to end. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 3007–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugger, S.J.D.; Ceamanos, L.; Mulder, D.J.; Sánchez-Somolinos, C.; Schenning, A.P.H.J. 4D printing of supramolecular liquid crystal elastomer actuators fueled by light. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 2201472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Wang, L.; Wei, Z.; Xiao, R.; Qian, J. Fracture and fatigue characteristics of monodomain and polydomain liquid crystal elastomers. Soft Matter 2025, 21, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.S.; Lee, Y.-J.; Wang, Y.; Park, J.; Winey, K.I.; Yang, S. Self-folding liquid crystal network filaments patterned with vertically aligned mesogens. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 50171–50179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Liu, H.; He, Y.; Li, N.; Wang, T.; Yang, Z.; Guo, Q.; Gan, J.; Yang, Z. Biocompatible liquid crystal elastomer optical fiber actuator for in vivo endoscopic navigation and laser ablation therapy. Adv. Mater. 2025, e16047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Liao, W.; Yang, Z. Liquid crystal elastomer twist fibers toward rotating microengines. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2107840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Liao, W.; Yang, Z. Additive manufacturing of liquid crystal elastomer actuators based on knitting technology. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2400763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Technology | Typical Diameter/μm | Alignment Fixation | Limitations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrospinning | 10–100 | Fixation via external stretching followed by post-curing | ➓ Prone to polydomain ➓ High voltage | [16,30,31] |

| Wet spinning | 20–770 | Shear-induced alignment with in situ fixation in coagulation bath | ➓ Complex solvent handling ➓ Stringent requirements for spinning solution properties | [33,34,36] |

| Melt electrowriting | 4.5–60 | Shear-induced alignment with real-time UV curing | ➓ Low printing stability ➓ Low preparation efficiency ➓ Complex equipment setup | [35,37] |

| Melt spinning | 40–860 | Shear-induced alignment with real-time UV curing | ➓ Unable to prepare microfibers | [22,29,38] |

| Melt-centrifugal spinning | 10–40 | Flow-induced alignment with on-the-fly two-step UV curing | ➓ Potential inter-fiber fusion | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liao, W.; Jia, C.; Yang, Z. Liquid Crystal Elastomer Microfiber Actuators Prepared by Melt-Centrifugal Technology. Actuators 2026, 15, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15020093

Liao W, Jia C, Yang Z. Liquid Crystal Elastomer Microfiber Actuators Prepared by Melt-Centrifugal Technology. Actuators. 2026; 15(2):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15020093

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiao, Wei, Chenglin Jia, and Zhongqiang Yang. 2026. "Liquid Crystal Elastomer Microfiber Actuators Prepared by Melt-Centrifugal Technology" Actuators 15, no. 2: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15020093

APA StyleLiao, W., Jia, C., & Yang, Z. (2026). Liquid Crystal Elastomer Microfiber Actuators Prepared by Melt-Centrifugal Technology. Actuators, 15(2), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15020093