1. Introduction

Soft robotics is an emerging field that aims to replicate the movements and mechanical properties of living organisms through bioinspired systems [

1,

2]. These robots are fabricated using highly deformable elastomeric materials, including silicones, resins, hydrogels, and polymers [

3,

4]. Their motion arises from structural deformation, which provides flexibility and adaptability, making them particularly suitable for operation in uncertain or dynamic environments [

5], for delicate object manipulation [

6], and for ensuring safe human interaction in fields such as medicine, agriculture, and exploration [

7,

8,

9].

Unlike conventional rigid robots powered by electric motors, soft robots rely on alternative actuation mechanisms such as tendons, pressurized fluids, magnetic or electric fields, and chemical reactions [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Among these, pneumatic actuators are the most extensively studied. They operate by inflating or deflating internal chambers to generate motions such as bending, stretching, compression, and twisting [

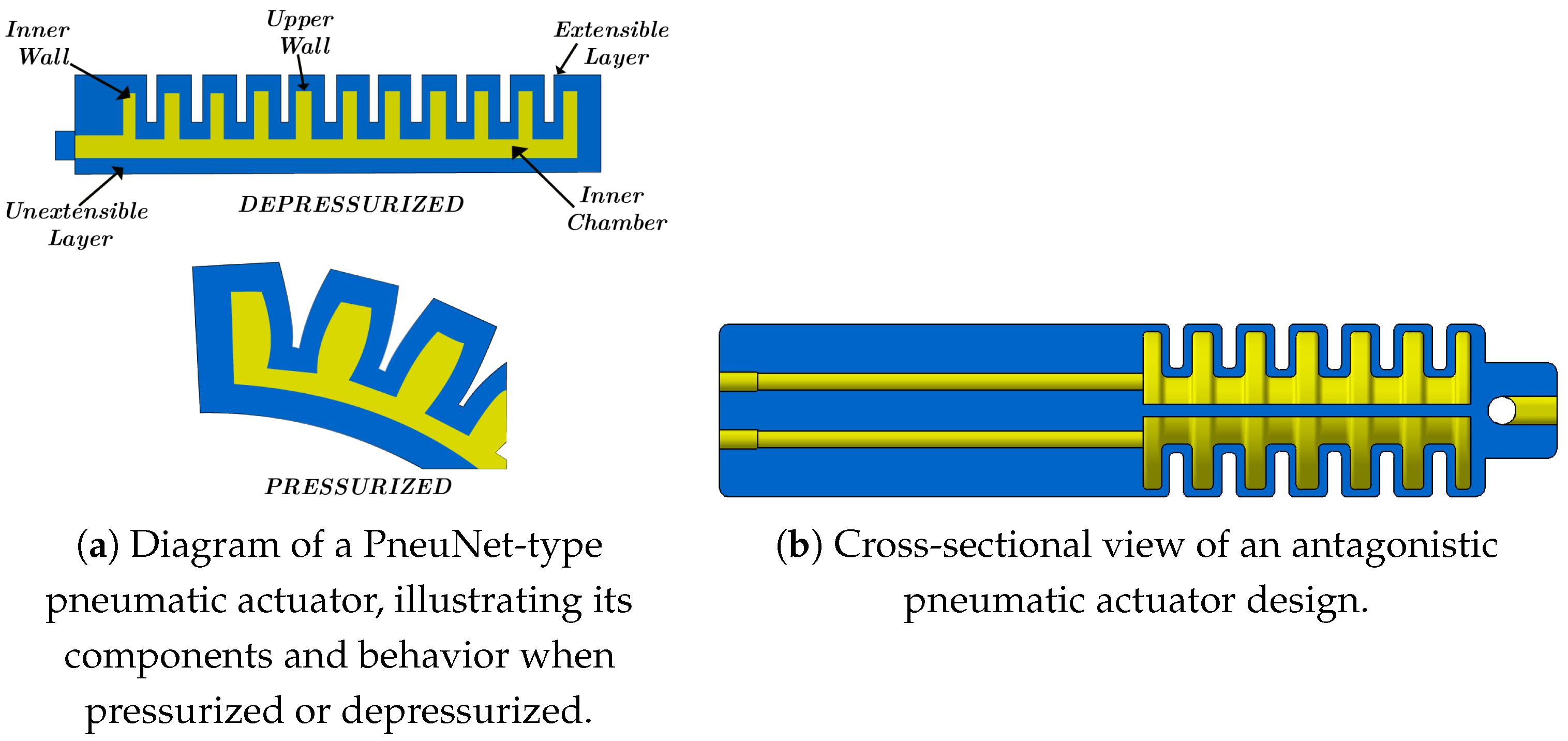

15]. These actuators, known as PneuNets (Pneumatic Networks), are shown in

Figure 1. By arranging multiple PneuNet actuators antagonistically, it is possible to reproduce muscle-like coordinated movement.

Traditionally, soft pneumatic actuators are manufactured by casting silicone elastomers. Although effective, this process is slow, costly, and limited in geometric complexity [

16,

17]. Additive manufacturing (AM), particularly stereolithography (SLA), has emerged as a promising alternative, enabling the mold-free fabrication of complex actuators with high resolution and geometric precision [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

Several studies have demonstrated the potential of SLA in soft actuator fabrication. Peele et al. [

20] pioneered the stereolithographic printing of an antagonistic four-chamber actuator capable of 3D deformation. However, the relatively stiff resin used (Shore 65A, Elastomeric Precursor (EP); Spot-E resin, Spot-A Materials Inc., Askeby, Denmark, elongation ≈40%) limited its strain capacity, and no constitutive modeling or finite element analysis (FEA) was performed. Subsequent works, notably by Xavier et al., advanced the integration of analytical modeling, FEA, and experimental validation for 3D-printed actuators. In [

24], they emphasized the need for accurate hyperelastic characterization to capture nonlinear deformation and pressure–geometry coupling. In a related study [

25], the authors reviewed computational modeling techniques, identifying the limitations of simplified analytical methods and stressing the importance of constitutive calibration for predictive reliability, principles that guided the present study.

Recent advances have extended toward functional materials and smart actuation strategies. Tawk et al. [

26] presented a modular SLA-printed gripper integrating mechanical metamaterials for conformal grasping, validated through FEA and experimental testing. Gunawardane et al. [

27] introduced deep learning algorithms to identify variable-stiffness configurations in zig-zag pneumatic actuators. These works illustrate a trend toward adaptive and intelligent soft systems. However, they primarily focus on motion control and stiffness tuning rather than on an experimental–numerical correlation of material properties, stress distribution, and failure behavior, critical aspects for reliability and scalability.

Parallel advances in material characterization have also underscored the need for rigorous constitutive modeling. The nonlinear and nearly incompressible behavior of elastomers requires robust hyperelastic formulations such as Neo-Hookean, Mooney–Rivlin, Yeoh, or Ogden models [

28,

29]. Shahzad et al. [

30] demonstrated how fitting procedures based on uniaxial data can accurately reproduce material response under multiple loading modes when properly optimized. However, many SLA-based actuator studies still rely on nominal manufacturer data rather than experimentally fitted parameters, introducing uncertainty into FEA simulations. Recent works by Zamora-García et al. [

22] and Zhuang et al. [

23] characterized the mechanical response of photopolymer resins but did not link these data to actuator-level stress prediction or performance analysis.

In this work, we present the stress analysis of an SLA-printed soft antagonistic pneumatic actuator designed with four independent PneuNet chambers, inspired by Peele’s architecture.The actuator is fabricated using Elastic 50A Resin V2 (Formlabs Inc., Somerville, MA, USA), a softer material with improved elongation properties. The material is experimentally characterized through uniaxial tensile tests following the ASTM D412 standard [

31]. Subsequently, the parameters of several hyperelastic models are calibrated in the Abaqus environment to identify the model that best reproduces the experimental behavior. The actuator’s response is then simulated using the Yeoh hyperelastic model under various operating modes, and the simulation results are validated experimentally, confirming the predictive capability of the numerical model.

Unlike previous studies that only demonstrated the printability of soft structures or performed basic material characterization, the present study integrates material testing, hyperelastic modeling, finite element simulation, and experimental validation. The main contributions of this work are as follows: (1) the direct fabrication of a four-chamber antagonistic actuator in a single SLA printing step, without molds, bonding, or assembly, capable of producing multidirectional bending, elongation, and compression; (2) the experimental characterization of Elastic 50A Resin V2 and calibration of the Yeoh hyperelastic model for accurate numerical prediction; (3) the finite element modeling of pressure thresholds, structural failure, and stress localization to define safe operational limits and (4) the experimental quantification of rupture pressures and their comparison with simulation results, confirming the conservative accuracy of the FEA-based predictions. Together, these contributions provide a complete digital–experimental workflow that supports the development of structurally reliable, reproducible and scalable soft actuators for bioinspired and biomedical robotic applications.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the material characterization process and the selection of appropriate hyperelastic models for the elastomer.

Section 3 describes the design and fabrication of the actuator using stereolithography and the finite element analysis setup.

Section 4 reports the finite element simulation results performed in Abaqus/CAE 6.14-1 (Dassault Systèmes, (Simulia Corp, Vélizy-Villacoublay, France), together with the corresponding experimental validation. Finally,

Section 5 discusses the findings and outlines the main conclusions.

3. Actuator Design

The actuator consists of two antagonistic pneumatic systems [

20], comprising a total of four independently actuated cavities. The upper half incorporates a pair of opposing PneuNet chambers (first antagonistic system) that enable bending in one direction. The lower half includes a second pair of opposing PneuNet chambers, oriented at 90° with respect to the upper set (second antagonistic system), complementing the deformation produced by the upper cavities.

CATIA V5R21 (Dassault Systèmes, Simulia Corp., Vélizy-Villacoublay, France) was used to design an actuator suitable for additive manufacturing via stereolithography (SLA). The design considered three key parameters: the thickness of the top wall (), the thickness of the side walls () of the internal chambers, and the radius of the inner air chamber (). A proper balance of wall thicknesses was essential: excessive thickness increases the actuator’s stiffness, hindering deformation, whereas overly thin walls may cause over-inflation of the chambers, reducing the deflection capacity and increasing the risk of mechanical failure.

The optimal parameter selection for the actuator was determined through finite element simulations in Abaqus. This approach minimized costs, reduced production time, and avoided material waste during prototyping. Multiple simulations were conducted, varying the main design parameters while analyzing the relationship between input pressure and chamber expansion, as well as actuator deformation and stress concentration at critical points. Based on this analysis, the final parameter values were established, as illustrated in

Figure 5.

Since the actuator’s total length was a secondary parameter, it was defined according to the maximum build dimension of the 3D printer, resulting in a length of 170 mm. The actuator diameter was set to 36 mm, with each of the four PneuNets containing six chambers. In addition, the central wall dividing the two upper cavities was designed with two longitudinal perforations of mm in diameter, allowing airflow into the lower cavities. This configuration enables bending and elongation when all four cavities are pressurized, as well as compression when air is simultaneously extracted from them.

3.1. Additive Manufacturing Parameters and Post-Processing

The actuator was fabricated using a Formlabs Form 3+ stereolithography (SLA) printer and Elastic 50A V2 resin. The printing workflow was managed through the PreForm 3.53.0 software (Formlabs Inc., Somervile, MA, USA), which was used to define the part orientation, layer resolution, and support configuration. A layer thickness of 100 μm was selected, consistent with the manufacturer’s recommended settings for this material, providing an adequate balance between surface quality and printing time.

The actuator was oriented diagonally across the build platform to maximize the printable length, resulting in a orientation of the printing layers relative to the XY-plane. The printing parameters were adjusted to prevent the addition of internal supports within the cavities, ensuring that the actuator could be fabricated as a single piece. The printing process required approximately and consumed a total of of resin, generating 420 layers.

Following fabrication, the actuator was washed for in a Form Wash (Formlabs Inc., Somervile, MA, USA) unit containing isopropyl alcohol (IPA) to remove surface and partially trapped resin. Additional manual cleaning was performed using a pipette to ensure complete removal of residual resin from the internal cavities. The final post-curing stage was conducted in a Form Cure (Formlabs Inc., Somervile, MA, USA) chamber at 70 °C for , following the same protocol applied to the test specimens to ensure material consistency across all samples.

The selected printing parameters and post-processing protocol ensured high dimensional fidelity and consistent mechanical behavior, which are critical for accurate experimental validation of the actuator’s performance.

3.2. Soft Pneumatic Behavior Analysis

A finite element analysis (FEA) was conducted to predict the behavior and performance of the soft pneumatic actuator, to optimize its design parameters, and to address the system’s inherent nonlinearities. These nonlinearities include the hyperelastic behavior of elastomers, contact interactions between the external lateral walls of the chambers, and large geometric deformations of the actuator, all of which make the modeling of soft robotic systems particularly challenging. Moreover, FEA enables the visualization of stress concentrations and strain distributions, providing valuable insights for design refinement.

The simulations were performed in Abaqus within the Standard/Explicit framework on a workstation equipped with an Intel Core i9-14900HX processor (Intel Corp., Santa Clara, CA, USA) (24 cores, 32 threads), 32 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 graphics card (NVIDIA Corp., Santa Clara, CA, USA) with 8 GB of memory. The actuator geometry, designed in CATIA V5R21, was imported into Abaqus, where the mechanical properties of the elastic resin were assigned based on experimental uniaxial tensile test data. The Yeoh hyperelastic model was selected due to its superior accuracy in capturing the material’s nonlinear behavior.

In the experimental setup, the actuator is anchored at its upper end to a rigid support that secures it to the test platform. Accordingly, in the simulation, the upper surface of the model was constrained in all six degrees of freedom to represent that fixation (see

Figure 6a). The actuator’s lower, free end was left unconstrained to allow deformation under the action of internal pressure and the actuator geometry. Self-contact interactions were defined between the actuator’s external walls (

Figure 6b), since upon pressurization, opposing (antagonistic) cavities tend to compress and come into contact. In the simulation, these contact definitions prevent nonphysical penetration between nodes or elements, faithfully reproducing the real material behavior and ensuring numerical stability during large deformations. The effect of friction between contacting surfaces was also included because a high friction coefficient can restrict sliding and alter the actuator’s mechanical response.

A mesh convergence analysis was performed to determine the optimal element size. This iterative procedure involved defining an initial mesh size, running the simulation, recording the stress and strain results, and refining the mesh until convergence. The convergence criterion—or refinement stopping point—was defined as the stage at which the percentage variation in the relative error of the maximum principal stress and strain was below

, a threshold adopted to ensure numerical stability of the results. Comparative analysis across different mesh sizes showed that for element sizes smaller than

, the relative error variation remained below

. Consequently, a global element size of

was selected, complemented by local mesh refinement to

in critical regions, particularly along the inner walls of the actuator where pressure is applied, following the recommendations of [

25,

40,

41]. The final mesh consisted of 432,140 quadratic tetrahedral C3D10H elements, ensuring independence of the results from mesh discretization. These elements, specifically formulated for hyperelastic materials, enhance accuracy under nonlinear deformations and mitigate volumetric locking, making them particularly suitable for modeling nearly incompressible elastomers.

Pressure loads were applied exclusively to the internal chambers (

Figure 6c), activating one or more cavities depending on the desired deformation mode. The applied pressure ranged from 20 kPa to 130 kPa, consistent with the capacity of the available pneumatic system. To avoid convergence issues, the time increment was set to

for the gravity application step and

for the pressure application step. Pressure was applied gradually to minimize numerical instabilities and to improve the accuracy of the predicted deformations. Additionally, the NLgeom option was activated to account for geometric nonlinearities and large displacements, both of which are critical in simulations of hyperelastic materials and highly deformable structures.

5. Discussion

This study demonstrates that SLA-printed antagonistic actuators can be effectively modeled using the Yeoh hyperelastic formulation, yielding reliable predictions of stress distribution and operational pressure limits. These results extend previous work on cast soft actuators [

20] by validating SLA as a reproducible method for rapid prototyping. In contrast to [

42], which optimized design parameters across different geometries, our work focuses on identifying structural failure thresholds and experimentally validating safe operating pressures.

Geometric deviations and internal resin residues, as reported in [

43], were also observed in our samples and likely contributed to discrepancies between experimental and simulated results. Such deviations led to higher rupture pressures in experiments than in FEA predictions assuming ideal geometries. Our antagonistic architecture achieves multidirectional motion without fiber reinforcement, simplifying fabrication while preserving flexibility, though this simplicity comes with trade-offs in mechanical precision.

Several limitations must be acknowledged regarding both fabrication and modeling. First, fabrication tolerances inherent to the SLA process introduce slight geometric deviations between the CAD model and the printed parts. For example, tensile test specimens designed with a width of and a thickness of showed average printed dimensions of and , respectively. Similarly, the actuator’s external diameter exhibited a variation of less than from the nominal . While these deviations are minimal, they may influence localized stress distribution and, consequently, the failure pressure thresholds observed experimentally.

Two fabrication-related defects were particularly relevant. First, residual uncured resin within internal cavities could not be entirely removed, even after sequential external and internal washing cycles. Once post-cured, these residues locally increased stiffness, potentially altering deformation profiles. Second, tensile stresses generated during the UV post-curing process caused slight warping after support removal. Although minor, these deformations suggest that stress relaxation during curing can influence the final geometry and, consequently, the actuator’s performance. Despite these imperfections, the reproducibility across actuators remained high, indicating that fabrication tolerances had a greater impact on accuracy than on repeatability.

Another source of uncertainty arises from potential material anisotropy. The Elastic 50A V2 resin is designed to exhibit near-isotropic behavior; however, the photopolymerization process may lead to directional differences in stiffness and elongation depending on layer orientation, laser exposure uniformity, and post-curing depth [

36]. In this study, all actuators were printed with the same orientation and curing protocol, and no significant directional variation was observed. Nevertheless, future work should quantitatively evaluate anisotropy through mechanical testing of specimens printed along different axes (X, Y, Z) and include corresponding anisotropic material models in FEA simulations. Such analysis would help determine whether layer orientation or local curing gradients introduce measurable mechanical heterogeneity.

Regarding post-curing variability, all actuators underwent identical UV exposure conditions, minimizing operator-induced inconsistencies. However, excessive immersion in isopropyl alcohol during cleaning could alter surface chemistry and lead to minor changes in elasticity. Systematic evaluation of these effects could improve long-term reproducibility of material properties.

Finally, this study focused on quasi-static pressurization and did not account for dynamic loading or fatigue effects. While rupture tests identified the maximum safe operating pressure, the cyclic durability and Mullins effect of the printed actuators remain unexplored. Assessing the fatigue life under repeated actuation cycles would provide valuable insights into long-term reliability and structural degradation mechanisms. Similarly, the finite element simulations assumed static internal pressure and did not incorporate time-dependent viscoelasticity or cyclic stress accumulation, which could partially explain the discrepancy between numerical and experimental deformation magnitudes.

Future work should incorporate biaxial and shear material characterization, anisotropic constitutive modeling, and topology or shape optimization frameworks to identify geometries that maximize deformation range while minimizing stress concentration. Integration of quantitative tracking systems, such as optical or depth-based sensors, will also enhance experimental validation by enabling precise deformation mapping across multiple actuation modes. Moreover, cyclic actuation tests will be essential to establish fatigue thresholds and further validate the durability of SLA-printed soft actuators for real-world applications.

6. Conclusions

This work presented the design, material characterization, and structural analysis of an SLA-printed antagonistic soft pneumatic actuator fabricated from Elastic 50A Resin V2. Material calibration from uniaxial tensile tests identified the Yeoh hyperelastic formulation as the best fit for the tested deformation range and was successfully implemented in Abaqus to predict actuator behavior. Finite element simulations reproduced the principal deformation modes observed experimentally (multidirectional bending and axial elongation) and identified critical stress zones. The simulations predicted conservative failure thresholds of approximately for the upper cavities and for the lower cavities, while destructive tests yielded experimental rupture pressures near (upper) and (lower). The material ultimate tensile strength, according to the manufacturer, was measured at , and the maximum principal stresses from FEA approaching this value were used to define safety margins for operation.

Beyond summarizing results, several practical conclusions and limitations emerge. Manufacturing reproducibility is high: dimensional deviations measured in tensile specimens were small and actuator diameters deviated by less than from the CAD nominal value. Nonetheless, two fabrication issues materially affect mechanical accuracy: (i) residual uncured resin trapped in internal cavities locally increases stiffness after curing and can raise the experimental rupture pressure relative to idealized simulations; and (ii) minor warping induced by UV post-curing and support removal alters the final geometry. These factors explain part of the conservative bias of the FEA results and indicate that tight control of cleaning and curing protocols is essential for predictive accuracy.

Concerning the scalability and integration of this prototype, the present actuator length (170 mm) was constrained by the printer’s build volume and by the chosen diagonal orientation that maximized printable length but introduced 45° layer directions. Scaling to larger devices will require either segmentation combined with reliable bonding strategies or alternative print orientations and support management. For practical deployment, for instance, in adaptive grippers or biomedical manipulators, designs should account for geometric tolerances and incorporate safety factors consistent with the observed conservative FEA predictions (e.g., limiting operational pressures to approximately 70– of the experimentally observed rupture pressures for continuous use).

Long-term performance and repeatability under cyclic loading remain open issues. This study did not perform systematic fatigue testing or quantify Mullins-type stress softening or viscoelastic relaxation. Preliminary repeated-pressurization trials showed no immediate failure but are insufficient to establish service life. We recommend that future testing aims to (a) quantify fatigue life under representative duty cycles (for example, target benchmarks of – cycles for components intended for repeated actuation), (b) measure Mullins and hysteresis effects under cyclic loading, and (c) incorporate time-dependent viscoelastic material models into FEA to improve dynamic prediction.

Finally, practical recommendations and research directions derived from our findings include: (1) performing biaxial and shear tests to complement uniaxial characterization and enable anisotropic modeling if required and (2) applying topology or shape optimization constrained by the identified stress hotspots to enhance performance while maintaining manufacturability. By following these guidelines and adopting conservative operational limits informed by both FEA and destructive testing, SLA-printed antagonistic actuators can advance toward reliable, repeatable applications in fields such as adaptive grippers and bioinspired manipulators, while addressing the additional steps required to ensure long-term durability and scalability.