Abstract

Piezoelectric synthetic jet actuators typically struggle to generate high-speed jets at low driving frequencies due to the coupling effect between jet frequency and jet intensity. This limitation to some extent restricts their application in flow control within low-speed flow fields. To address this issue, this study presents two methods of signal modulation. The effects of driving signal modulation on dual synthetic jet actuator (DSJA) characteristics were experimentally investigated. A laser displacement meter was used to measure the central point amplitude of the piezoelectric diaphragm, while the velocity at the exit of the DSJAs was measured using a hot-wire anemometer. The effects of signal modulation on the amplitude of the piezoelectric diaphragm, the maximum jet velocity, and the frequency domain characteristics of the dual synthetic jet (DSJ) were thoroughly analyzed. Experimental results demonstrate that driving signal modulation can enhance jet velocity at relatively low driving frequencies. The modulated DSJ exhibits low-frequency characteristics, rendering it suitable for flow control applications that require low-frequency jets. Furthermore, the coupling effect between jet frequency and jet intensity in the piezoelectric DSJA is significantly alleviated. Starting from the vibration displacement of the piezoelectric transducer (PZT), this paper systematically elaborates on the corresponding relationship between PZT displacement and the peak velocity at the jet outlet, and the “low-frequency and high-momentum jet generation method based on signal modulation” proposed herein is expected to break through the momentum–frequency coupling limitation of traditional piezoelectric dual-stenosis jet actuators (DSJAs) and enhance their application potential in low-speed flow control.

1. Introduction

Active flow control (AFC) remains a leading area of research, with wide-ranging applications in aeronautics, civil engineering, and mechanical engineering, among other fields. In recent years, remarkable progress has been made in various active flow control technologies. Among these, blowing/suction [1,2], synthetic jet [3,4,5,6,7], dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma jet [8], and sweeping jet technologies [9] have shown significant development. In particular, synthetic jet (SJ) technology has emerged as one of the most rapidly advancing active flow control technologies in recent decades.

Passive control typically requires the addition of auxiliary devices or modifications to aerodynamic surfaces [10,11,12,13,14]. In contrast, the core of active flow control technology lies in the actuator. Luo et al. [15] have emphasized that achieving effective control results depends on a highly reliable synthetic jet actuator, which serves as the core foundation of active flow control technology. Based on the vibration components of the actuator, synthetic jet actuators can be classified into various types. Common vibration sources include piezoelectric diaphragms (PZT), pistons, and shape memory alloy diaphragms. Among these, the piezoelectric synthetic jet actuator (SJA) is widely used due to its advantages, such as not requiring an external air source, compact size, lightweight design, rapid response, and high efficiency [16].

In the 1990s, Smith et al. [7] invented the first piezoelectric SJA. This actuator is capable of generating jets with maximum velocities ranging from tens to hundreds of meters per second and achieving frequencies of up to thousands of Hertz, thereby demonstrating robust flow control capabilities in low-speed flow fields. Additionally, its ease of miniaturization and precise control of electrical parameters make it highly promising for various flow control applications [17]. Building on the SJA, Luo et al. [18] developed the dual synthetic jet actuator (DSJA) in 2006, significantly enhancing control efficiency. Compared to the conventional SJ, the DSJ operates at twice the vibrating frequency of the piezoelectric diaphragm, effectively doubling the range of controllable flow field frequencies. DSJ technology has been successfully applied in various fields, including airfoil flow separation control, flow control around blunt bodies, and fluidic flight control. For instance, Zhao et al. [19] investigated the use of DSJAs positioned along the chord and a trailing-edge SJA to control the flow separation of a NACA0015 airfoil. The results showed that the DSJAs effectively suppressed flow separation, while the trailing-edge SJA facilitated circulation control. Notably, the combined use of SJA and DSJAs successfully suppressed flow separation even at a high angle of attack (AOA) of 19°. In another study, Li et al. [20] applied dual synthetic jet technology to control the flow around a three-dimensional square cylinder, demonstrating its effectiveness in managing aerodynamic forces and wake flows. Furthermore, Zhao et al. [21] introduced a flight control method based on DSJs and applied it to a large-sweep flying wing aircraft at the leading edge. Their findings indicated that the leading-edge DSJ is an effective method for lift enhancement and flight control, as it generated significant increments in lift coefficient and pitching moment.

While piezoelectric synthetic jet actuators (SJA) and dual synthetic jet actuators (DSJA) have been extensively utilized in flow control applications, their development is, to some extent, restricted by the properties of the piezoelectric diaphragm. Typically, a piezoelectric SJA or DSJA operates at frequencies ranging from several hundred to one or two thousand Hz. In contrast, their typical targets, low-speed flow fields, have characteristic frequencies in the range of tens of Hertz. Numerous studies have indicated that for low-speed flow fields, the optimal excitation frequency for periodic excitation is approximately around F+ ~ O(1) [22]. This requires the piezoelectric actuator to generate low-frequency jets. However, the resonant frequency of the piezoelectric diaphragm in the piezoelectric actuator is approximately one order of magnitude higher than the characteristic frequency of the flow field. If the driving frequency is adjusted to several tens of Hertz, the piezoelectric actuator cannot operate in its optimal state, thus being unable to simultaneously generate a jet with a high momentum coefficient and a low jet frequency. This phenomenon is known as the coupling effect between the jet frequency and jet intensity of a piezoelectric actuator [16], which significantly limits the applicability of piezoelectric actuators for flow control in low-speed flow fields. To further enhance the control capability of synthetic jet actuators, it is essential to address and overcome the coupling effect between jet frequency and jet intensity.

Recent studies have demonstrated that signal modulation methods are effective in eliminating the coupling effect between jet frequency and jet intensity while simultaneously improving flow control performance. Liu et al. [23] introduced a novel approach of modulating synthetic jet driving signals with Amplitude Modulation (AM) to enhance control authority. Their study demonstrated that modulating the driving signal at low frequencies can alter the distribution of vortices in the flow field. The synthetic jet under AM modulation was shown to significantly improve the lift-to-drag ratio of the airfoil. Furthermore, Lu et al. [24] proposed a multi-frequency driving signal modulation method, which combines a basic sinusoidal wave with a superimposed high-frequency signal. Their results indicated that after superposing high-frequency signals, the strength of synthesized vortices induced by the jet flow was enhanced, and the downstream propagation velocity was increased. Güler et al. [25] conducted wind tunnel experiments to investigate the influence of DBD plasma synthetic jets with different types of signal modulation on the flow characteristics of the NACA0015 airfoil. Their findings revealed that signal modulation can increase lift while reducing energy consumption. Additionally, Benard et al. [26] performed wind tunnel experiments to examine the effects of amplitude modulation and pulse modulation on flow control around a circular cylinder using DBD plasma synthetic jets. Their results showed that signal modulation achieved flow control effects comparable to those of unmodulated DBD plasma excitation. Moreover, pulse modulation demonstrated superior performance in suppressing vortex shedding. In conclusion, signal modulation has been proven to offer several advantages in flow control. In addition to the aforementioned methods, more details about the signal modulation method will be provided in Section 2.2. For piezoelectric synthetic jet actuators, Liu et al. [23] noted that signal modulation can somewhat mitigate the coupling effect between jet frequency and jet intensity, and further research is warranted in this area. On the one hand, it is essential to strengthen the research on existing methods. On the other hand, we should focus on exploring new signal modulation methods.

To address the coupling effect, this paper proposes two signal modulation methods to modulate the vibration of the piezoelectric diaphragm for the DSJA, aiming to resolve the critical issue in piezoelectric actuators. The amplitude of the diaphragm at the central location is measured using a laser displacement meter. The velocity characteristics at the outlet region of the DSJA are measured using a hot-wire anemometer. The influence of signal modulation on the velocity characteristics at the DSJA outlet is examined.

2. Experimental Details

2.1. Experimental Setups

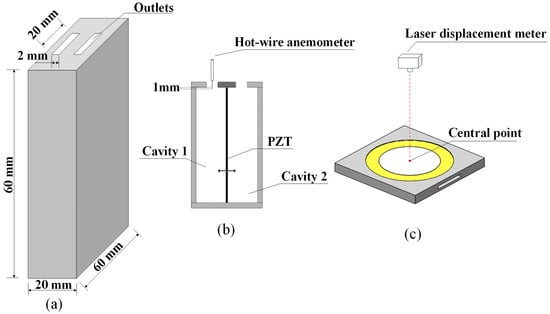

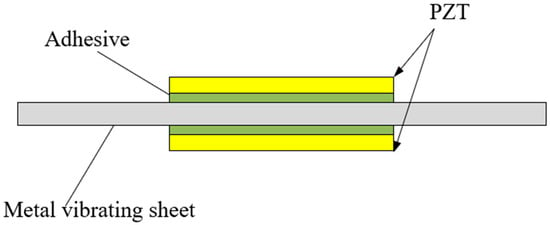

Figure 1a demonstrates the dimensions of the DSJA, with both outlets measuring 2 mm × 20 mm. The DSJA is connected to a signal generator (DG 1022 is manufactured by RIGOL Technologies Co., Ltd., with its production site in Shenzhen, China) and a power amplifier (XE500-A is manufactured by Xi’an Xuner Electronic Technology Co., Ltd., with its production site in Xi’an, China). As shown in Figure 2, the piezoelectric vibrator consists of a PZT ceramic sheet, an adhesive, and a metal vibrating sheet (phosphor bronze). For the metal vibrating sheet, the distance between its two slots is 5 mm and the depth of each slot is 5 mm. Among these components, the PZT ceramic sheet has a diameter of 32 mm and a thickness of 0.2 mm. As illustrated in Figure 3, the signal generator produces a sinusoidal signal, which is amplified by the power amplifier to drive the diaphragm’s vibration, thereby generating the jet. A hot-wire anemometer (HangHua CTA-04A is manufactured by Dalian Hang Hua Technology Co., Ltd., with its production site in Dalian, China) is employed to measure the air velocity at the outlet. The anemometer is positioned at the center of the outlet, extending approximately 1 mm into the outlet. The hot-wire anemometer operates with a sampling frequency of 2000 Hz, a sampling duration of 20 s, and a total of 40,000 sampling points. A laser displacement meter (LK-G150 is manufactured by Keyence Corporation, with its production site in Osaka, Japan) is utilized to measure the vibration displacement of the PZT at its central point. The laser displacement meter is positioned approximately 150 mm above the center point of the diaphragm. After zero calibration, the laser displacement meter can measure a maximum displacement of ±40 mm with a precision of 10−5 mm, satisfying the measurement requirements for the PZT displacement. The laser displacement meter operates with a sampling frequency of 2000 Hz, a sampling duration of 20 s, and a total of 40,000 sampling points.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup. (a) actuator parameters (b) hot-wire probe arrangement (c) laser displacement meter arrangement.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of a piezoelectric vibrator.

Figure 3.

The connection of experimental instruments.

2.2. Signal Modulation Method

Signal modulation is a widely employed technique in the field of communication, commonly utilized to facilitate wireless transmission, reduce antenna size, and enhance signal resistance to interference. When driving a piezoelectric DSJA, the driving signal applied to the diaphragm typically takes the form of a sinusoidal, cosine, or square wave with specific frequency and voltage amplitude. The time-domain and frequency-domain characteristics of the driving signal directly influence the vibration characteristics of the PZT. Therefore, modulating the driving signal can alter the vibration characteristics of the PZT, consequently affecting the characteristics of the DSJ.

The modulation methods utilized in this study include amplitude modulation (AM) and frequency modulation (FM). Amplitude Modulation (AM) is a widely used communication technique that transmits information by varying the amplitude of a carrier wave according to the modulating signal. In AM, the amplitude of the carrier wave is adjusted while maintaining a constant frequency. Frequency modulation, on the other hand, modifies the frequency of the carrier wave in response to variations in the modulating signal, keeping the amplitude constant. While other modulation techniques like phase modulation and pulse modulation exist, they are beyond the scope of this study.

In this study, the piezoelectric DSJA was selected as the research object. Three types of signals, including standard cosine, amplitude-modulated, and frequency-modulated signals, were applied to drive the PZT. The functional form of the standard cosine signal at various time points is presented as [5]

where U(t) represents the voltage of the cosine driving signal. Um denotes the maximum voltage amplitude of the original cosine signal, and signifies the frequency of the original signal. When the signal is modulated using amplitude modulation, the functional expression of the amplitude-modulated driving signal at different times is presented in Equation (2) [27]:

where UAM represents the voltage of the amplitude-modulated driving signal, and fAM denotes the modulation frequency for amplitude modulation. The subscript ‘M’ in this section signifies that the corresponding symbols or variables are associated with signal modulation. For instance, if the original signal with a driving frequency of 800 Hz is modulated with an amplitude-modulated frequency of 50 Hz, then f = 800 Hz and fAM = 50 Hz.

When frequency modulation is applied to the original signal, the frequency of the modulated driving signal varies in accordance with the modulation signal. In this study, the modulation signal is defined as a standard cosine signal. The voltage of the modulation signal (UFM) possesses the following mathematical expression [27]:

where fFM represents the modulation frequency for frequency modulation. UFM denotes the maximum voltage amplitude of the modulation signal. The functional expression of the original cosine signal remains as presented in Equation (1). Let , according to the definition of frequency modulation, the instantaneous angular frequency of the modulated signal after frequency modulation can be expressed as:

In Equation (4), Kf denotes the frequency modulation sensitivity, which establishes the relationship between the instantaneous angular frequencies of the modulated signal and time. The parameter possesses units of rad/s·V. The value of cos(2πfFMt) oscillates between ±1 over time and serves as a dimensionless quantity. By defining , represents the maximum deviation of the instantaneous angular frequency of the modulated signal relative to . Consequently, Equation (4) can be expressed as follows:

Likewise, if we define the relationship between the instantaneous angular velocity and the instantaneous frequency, Equation (5) can be written as follows:

Consequently, the maximum deviation of the instantaneous frequency of the modulated signal relative to f is described by the following function:

The unit of is Hz/V. quantifies the extent of frequency modulation applied to the original signal. In this study, fFM is set to 100 Hz using a signal generator. The instantaneous phase ) of the modulated driving signal is determined by integrating the instantaneous angular frequency () with respect to time, which can be mathematically expressed as:

If we establish = 0, then Equation (8) takes the following form:

By defining , the function expression for the voltage of the frequency-modulated driving signal ( can be mathematically expressed as:

where denotes the modulation factor for FM, which defines the maximum phase deviation of the modulated signal after FM relative to the original signal.

Figure 4 visually illustrates the effects of signal modulation on the original signal by displaying the waveforms of both the original and modulated signals. The original signal, labeled as NM (No Modulation), is represented without any modulation. The horizontal axis denotes the time scale in seconds, while the vertical axis represents the voltage amplitude in volts (denoted as V). The waveform reaches a maximum voltage amplitude of 50 V, with the standard cosine signal operating at a frequency of 500 Hz. Both the AM and FM modulation frequencies are set to 50 Hz. Following AM modulation, the peak values of consecutive peaks vary over time, while the intervals between adjacent peaks remain consistent, leading to temporal amplitude variations. Conversely, after FM modulation, the peak values of consecutive peaks remain stable, but the intervals between adjacent peaks vary, resulting in changes to the waveform’s density. Notably, both AM and FM modulation result in a complete cycle frequency of 50 Hz.

Figure 4.

Schematic of different signal waveforms.

2.3. Schedule of Working Conditions

Both the average velocity and the velocity peak are generally regarded as indicators for characterizing the jet velocity [28]. Signal modulation aims to mitigate the coupling effect between jet frequency and jet intensity, thereby generating high-speed DSJ with low frequency. For this purpose, the peak velocity of the central point at the outlet was selected as the indicator of jet velocity, referred to as peak velocity hereafter. The resonant frequency of the DSJA employed in this study was 400 Hz. Experimental measurements were performed to determine both the peak velocity and the vibration amplitude at the central point of the PZT. Table 1 summarizes the operating conditions for studying the characteristics of modulated DSJ. Without signal modulation, measurements were conducted as the driving frequency varied from 1 Hz to 800 Hz. Subsequently, both AM and FM modulations were applied with modulation frequencies of 1 Hz, 5 Hz, 10 Hz, 20 Hz, 50 Hz, 100 Hz, 200 Hz and 300 Hz, respectively.

Table 1.

Schedule of operating conditions.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Peak Velocity Characteristics

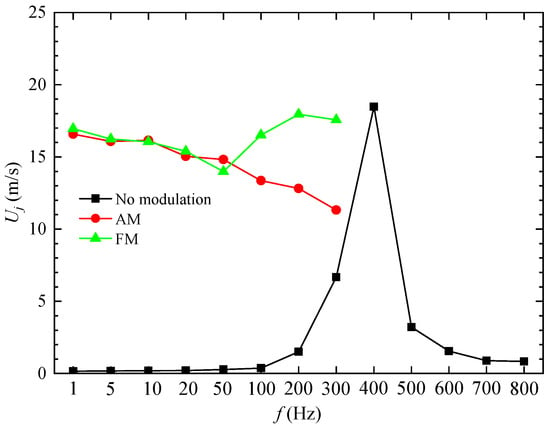

Figure 5 compares the peak velocities of unmodulated and modulated signals, demonstrating the impact of signal modulation on peak velocity (The average of the velocity extremes at the center of the jet inlet, whose experimental data was measured by a hot-wire probe placed 1 mm inward from the jet inlet). The results show that, in the absence of modulation (i.e., when the driving signal waveform is a direct sine or cosine signal), the DSJA achieves its maximum peak velocity of approximately 18.5 m/s at the resonant frequency of 400 Hz. Notably, the peak velocity of the DSJA observed in this section is relatively lower compared to the values reported in previous studies by Luo et al. [18] and Deng et al. [29]. This discrepancy can be attributed to two primary factors. Firstly, the applied voltage in this study is limited to ±210 V, which is relatively low for the PZT utilized. Secondly, a significant pre-tightening force is applied between the PZT and the actuator’s cavity, which to some extent constrains the vibration of the PZT. Importantly, the method proposed in this study remains effective for actuators exhibiting either higher or lower peak velocities. Similar control effects have been documented in related literature [30,31]. Furthermore, when the operating frequency deviates significantly from the resonant frequency (i.e., below 100 Hz or above 600 Hz), the peak velocity diminishes drastically, rendering effective jet generation nearly impossible. This phenomenon underscores the momentum–frequency coupling contradiction inherent to piezoelectric DSJAs. Under such conditions, the DSJA fails to achieve significant control effects in the controlled flow field, thereby limiting its practical application in low-speed flow control scenarios.

Figure 5.

The peak velocities under unmodulated and modulated conditions.

After applying AM and FM, significant changes in peak velocity characteristics are observed. First of all, within the range of 1 Hz to 300 Hz, the peak velocities are significantly enhanced compared to the unmodulated condition, reaching approximately 14 m/s to 17 m/s within the range of 1 Hz to 50 Hz, which is about 76% to 91% of the peak velocity at the resonant frequency. Interestingly, the peak velocity monotonically decreases under AM with increasing modulation frequency, while under FM, the peak velocity initially decreases and then increases. Within the 1 Hz to 50 Hz range, the peak velocities after both modulation types are very close. However, as the modulation frequency increases, the peak velocity after FM exceeds that after AM, approaching the peak velocity at the resonant frequency. In summary, AM and FM significantly enhance peak velocity, with FM generally showing better overall performance. When the modulation frequency is much lower than the resonant frequency, the modulation effects of both methods are comparable. Undoubtedly, amplitude modulation and frequency modulation have added the flexibility of actuator design [31] and resolved the momentum–frequency coupling contradiction mentioned above.

Figure 6 demonstrates the growth rate of peak velocity under different modulation conditions. In the present study, the growth rate is defined as the ratio of the velocity increment after applying modulation to the peak velocity at the resonant frequency without modulation. For instance, when the modulation frequency is set to 1 Hz, the application of AM or FM significantly enhances the peak velocity compared to the case without modulation. The growth rate at 1 Hz is then calculated as the ratio of this increment to the peak velocity at the resonance frequency. As shown in Figure 6, under AM, the growth rate remains above 80% for modulation frequencies ranging from 1 Hz to 20 Hz. Meanwhile, under FM, most modulation conditions maintain a ratio above 70%. This phenomenon clearly demonstrates that signal modulation methods exhibit a pronounced effect when the modulation frequencies are significantly lower than the resonance frequency. Therefore, this study investigates the peak velocity characteristics and vibration properties of the PZT under various modulation frequencies, specifically within the range of 1 Hz to 200 Hz. However, as the modulation frequency exceeds 200 Hz, the growth rate of peak velocity decreases rapidly under AM, leading to a gradual decline in the effectiveness of AM. Consequently, this study does not consider modulation characteristics near the resonance frequency of the PZT under AM.

Figure 6.

The growth rate of peak velocity in different modulation conditions.

Figure 7 illustrates the peak velocity of the DSJA under AM. It should be noted that different scales are used on the horizontal axis. The results indicate that at lower frequencies, the PZT of the DSJA exhibits minimal effective vibration, leading to ineffective jet generation. However, when applying AM, the peak velocity reaches approximately 15 m/s within the modulation frequency range of 1 Hz to 20 Hz. As the modulation frequency increases, the peak velocity gradually decreases. Additionally, it can be observed that the modulated jets exhibit low-frequency characteristics. The low-frequency characteristics become more pronounced when the modulation frequency is far from the resonance frequency.

Figure 7.

The peak velocity of the DSJA under AM.

Figure 8 depicts the peak velocity of the DSJA under FM modulation. When FM is applied, the peak velocity reaches approximately 15 m/s within the low-frequency range of 1 Hz to 20 Hz, yielding results comparable to those obtained with AM. However, a notable difference is observed: as the modulation frequency increases, the peak velocity initially decreases and then increases, attaining its minimum value at 50 Hz. At a modulation frequency of 200 Hz, the peak velocity becomes nearly equivalent to that at the resonant frequency, suggesting that the peak velocity characteristics may only differ in the low-frequency range. In terms of velocity characteristics, FM produces results similar to AM within the 1 to 20 Hz range but outperforms AM for frequencies exceeding 100 Hz.

Figure 8.

The peak velocity of the DSJA under FM.

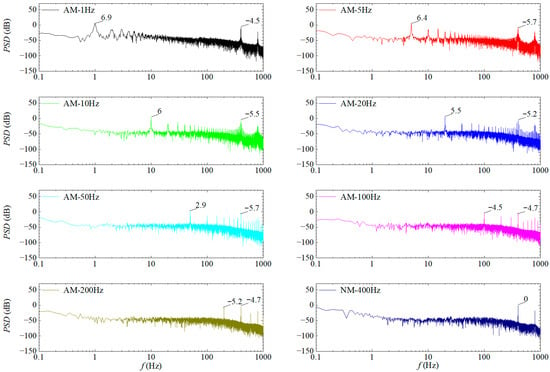

Figure 9 illustrates the power spectral density (PSD) of the peak velocity under AM. Following logarithmic processing, the vertical axis is converted to decibels (dB), while the horizontal axis represents frequency. The results reveal that a prominent peak in the PSD occurs at approximately 400 Hz without modulation. When AM is applied, the fundamental peak at 400 Hz remains distinctly noticeable. However, distinct peaks are also evident at various modulation frequencies in the PSD results, with each peak value being either more significant than or very close to the peak value at the resonant frequency. This phenomenon indicates that AM can effectively impart significant low-frequency characteristics to the modulated jets. Thus, the objective of utilizing signal modulation methods to address the momentum–frequency coupling contradiction has been preliminarily achieved in this chapter. Specifically, the AM method enables the piezoelectric DSJA to generate jets with both pronounced low-frequency characteristics and relatively higher velocities. This method is also applicable to the SJA.

Figure 9.

Frequency-domain characteristics of peak velocities under AM.

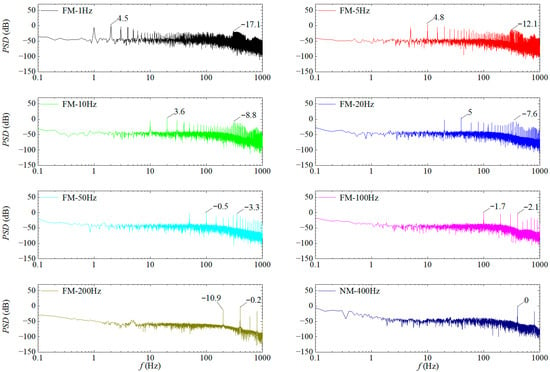

Figure 10 illustrates the PSD of the peak velocity under FM. The study demonstrates that when FM is applied at relatively lower frequencies (1 Hz to 20 Hz), two distinct peak values are observed: one at the modulation frequency and the other at twice the modulation frequency. Notably, the peak value at twice the modulation frequency exceeds that at the resonant frequency of 400 Hz. As the modulation frequency increases, the peak value at the resonant frequency surpasses both the peak value at the modulation frequency and twice the modulation frequency. This phenomenon suggests that the frequency-domain characteristics of modulated jets approach those of unmodulated jets when the modulation frequency is close to the resonant frequency, consistent with the observations in Figure 8. Additionally, it indicates that FM primarily enhances the low-frequency characteristics of the jets at relatively lower modulation frequencies. As shown in Figure 4, the waveform of the modulation signal with FM applied gradually resembles the original signal, causing the vibration characteristics under FM modulation to align with those observed without modulation. Consequently, the velocity characteristics after modulation also approach those without modulation. Furthermore, the low-frequency characteristics of the modulated jets are less pronounced compared to those at relatively lower modulation frequencies.

Figure 10.

Frequency-domain characteristics of peak velocities under FM.

3.2. Vibration Characteristics of PZT

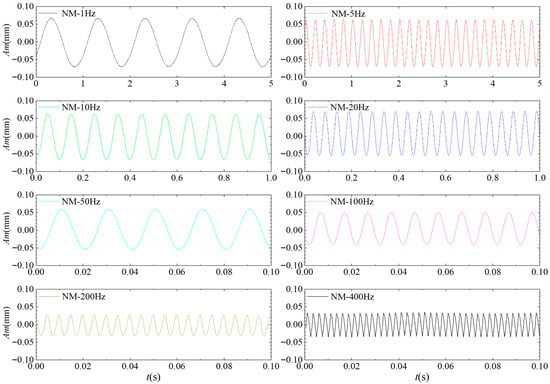

Figure 11 demonstrates the central point amplitude of the PZT under no modulation conditions at various frequencies. The study reveals that at relatively low frequencies (1 to 100 Hz), the amplitude of the PZT is considerably higher but decreases as it approaches the resonance frequency. The amplitude of the PZT reflects the change in the cavity’s volume compression. As shown in Figure 5, the velocity characteristics indicate that a DSJA can barely produce effective jets when its driving frequency is far from the resonance frequency. This occurs because, although the PZT amplitude is higher at low frequencies, the maximum rate of change in volume compression of the DSJA’s cavity is relatively low, resulting in a low peak velocity. However, as the driving frequency increases within a specific range near the PZT’s resonant frequency, both the maximum rate of change in volume compression and the volume compression of the DSJA are relatively high, leading to a significant increase in peak velocity. Deng et al. [27] pointed out that the prerequisite for generating high-momentum jets in a DSJA may be the simultaneous presence of large-volume compression and a high rate of change in volume compression. Therefore, when modulating the vibration characteristics of a PZT, it is essential to simultaneously enhance both the volume compression and the rate of change in volume compression. To further elucidate the mechanism of the modulating characteristics of AM and FM, the following sections will compare and analyze the volume compression and the rate of change in volume compression under different modulated conditions.

Figure 11.

The amplitude of the PZT’s central point at different frequencies under the no modulation condition.

Figure 12 illustrates the PZT’s central point amplitude at different frequencies under AM. As shown in Figure 12, when no modulation is applied, the PZT operates at a relatively high frequency of 400 Hz, with a maximum amplitude of approximately 0.03 mm at the central point. After applying AM, a significant increase in the maximum amplitude is observed. Under a modulation frequency of 1 Hz, the maximum amplitude at the central point of the PZT reaches approximately 0.25 mm. Additionally, it can be observed that the PZT exhibits both low-frequency and high-frequency vibration characteristics under the modulation frequency of 1 Hz. Therefore, two significant peaks appear in Figure 8, corresponding to the resonant and modulation frequencies. Moreover, the vibration of the PZT is no longer a cyclical motion centered around the initial position but rather a periodic vibration biased towards one side. However, due to the small displacement towards one side, the volumes of the two cavities remain approximately equal, and this does not affect the anti-phase characteristic of the DSJ.

Figure 12.

The amplitude of the PZT’s central point at different frequencies under AM.

Figure 13 illustrates the PZT’s central point amplitude at different frequencies under FM. The study demonstrates that after applying FM, the PZT exhibits low-frequency vibration characteristics between 1 Hz and 20 Hz. Similar to AM, the PZT continues to vibrate at the resonant frequency with high-frequency vibration. The maximum amplitude of the PZT is approximately 0.2 mm. As the modulation frequency increases, the maximum amplitude gradually decreases. When the modulation frequency increases from 50 Hz to 200 Hz, the vibration of the PZT becomes increasingly similar to that without modulation, i.e., exhibiting regular high-frequency vibration at the resonant frequency, particularly at the modulation frequency of 200 Hz. It is worth noting that under FM, the frequency at which the maximum amplitude occurs at the central point of the PZT corresponds to twice the modulation frequency, consistent with the velocity characteristics shown in Figure 10.

Figure 13.

The amplitude of the PZT’s central point at different frequencies under FM.

Figure 14 illustrates the power spectral density (PSD) of the amplitude under amplitude modulation (AM). When no modulation is applied (NM-400Hz condition), the peak value of the PSD result appears at approximately 400 Hz with a value of 0 dB. After applying AM modulation, the peak at the 400 Hz resonant frequency persists, but its magnitude varies slightly with different modulation frequencies. As the modulation frequency increases further: under the AM-50Hz condition, the peak at 50 Hz drops to 2.9 dB, lower than the 5.7 dB peak at 400 Hz, under the AM-100Hz condition, the peak at 100 Hz is 4.5 dB, comparable to but not exceeding the 4.7 dB peak at 400 Hz, when the modulation frequency exceeds 100 Hz, the peak at 200 Hz is only 5.2 dB and the peak at 400 Hz is 4.7 dB. Both are less prominent and lower than the peak levels observed when the modulation frequency is ≤20 Hz. The above quantitative comparison further confirms that a more pronounced modulation effect is achieved at lower modulation frequencies. After applying signal modulation, some inconspicuous small peaks appear in the frequency-domain characteristics of the piezoelectric ceramic (PZT) vibration—for example, the secondary small peaks outside 1 Hz and 400 Hz under the AM-1Hz condition. These peaks typically have low values, so their impact on vibration characteristics is limited. In conclusion, after applying AM modulation, the dominant effects on PZT vibration are the low-frequency vibration at the corresponding modulation frequency and the high-frequency vibration at the resonant frequency. AM modulation can induce additional low-frequency vibration in the PZT, but this effect is only significant when the modulation frequency is much lower than the resonant frequency.

Figure 14.

Frequency-domain characteristics of the amplitude under AM.

Figure 15 illustrates the power spectral density (PSD) of the amplitude under frequency modulation (FM). The study shows that after FM modulation, the peak at the 400 Hz resonant frequency persists. Compared with Figure 13, peaks at twice the modulation frequency emerge in the low—frequency range: when the modulation frequency is 1 Hz, the peak at 2 Hz reaches 4.5 dB, much higher than the 17.1 dB near 400 Hz, for 5 Hz modulation, the peak at 10 Hz is 4.8 dB, higher than 12.1 dB, for 10 Hz modulation, the peak at 20 Hz is 3.6 dB, higher than 8.8 dB, for 20 Hz modulation, the peak at 40 Hz is 5 dB, higher than 7.6 dB, and these low—frequency peaks all exceed the peak at 400 Hz. As the modulation frequency increases, such as for 50 Hz, 100 Hz, and 200 Hz modulation, the peaks at the corresponding frequencies (100 Hz, 200 Hz, etc.) gradually decrease (to −0.5 dB, −1.7 dB, −10.9 dB, respectively), indicating that the effect of signal modulation on the PZT’s vibration is weakened.

Figure 15.

Frequency-domain characteristics of the amplitude under FM.

Overall, it can be concluded that both FM and AM can induce low-frequency vibration on the PZT, and the modulation effect on the PZT’s vibration is significant when the modulation frequency is much lower than the resonant frequency.

Figure 16 illustrates the RMS value of the PZT’s amplitude under different modulation conditions. The RMS value serves as an indicator for evaluating the volume compression of the DSJA’s cavities. The results indicate that the variations in the RMS values of the amplitude of the PZT’s central point with modulation frequency are consistent with the variations in the peak velocities with modulation frequency. Specifically, under both AM and FM, at lower frequencies, the RMS values of the amplitude exhibit a significant increase compared to the unmodulated conditions, with maximum increments of 22% (fAM = 5 Hz) and 21% (fFM = 5 Hz), respectively. These increments directly demonstrate that the volume compression is enhanced after signal modulation. Moreover, in the absence of modulation, the RMS values of the amplitude of the PZT’s central point are already at a relatively high level, which corresponds to the results in Figure 10, indicating the further modulating capability of signal modulation on the PZT’s vibration characteristics.

Figure 16.

The RMS value of the PZT’s amplitude under different modulation conditions.

Figure 17 provides the RMS values of the PZT’s vibration velocity under different modulation conditions, denoted as Up,RMS, where the subscript ‘p’ represents the PZT. These values serve as an indicator for evaluating the rate of change in volume compression. The results clearly demonstrate that applying modulation significantly increases the RMS values of the PZT’s vibration velocity compared to the unmodulated conditions, with maximum increments of 86% and 97%, respectively. Combined with the results in Figure 15, it can be further confirmed that applying modulation can simultaneously enhance both the volume compression and the rate of change in volume compression at lower modulation frequencies, thereby improving the vibration characteristics of the PZT and significantly increasing the peak velocities of jets. It is important to note that when the modulation frequency is far from the resonance frequency, the modulation effect is more pronounced. Additionally, it can be observed that at the resonant frequency of 400 Hz, both the volume compression and the rate of change in volume compression are at a relatively high level, which explains why the DSJA can generate high-velocity jets at the resonant frequency, consistent with the velocity characteristics shown in Figure 5. The results also indicate that, for FM, at a modulation frequency of 200 Hz, both the volume compression and the rate of change in volume compression are very close to those at the unmodulated condition with a driving frequency of 400 Hz. Therefore, under FM with a modulation frequency of 200 Hz, the peak velocity characteristics are very close to those at the resonant frequency.

Figure 17.

The RMS values of the PZT’s vibration velocity under different modulation conditions.

In general, the proposed AM and FM methods can effectively address the momentum–frequency coupling contradiction of the piezoelectric DSJA. Modulated jets exhibit both high and low-frequency characteristics at lower modulation frequencies, with peak velocities approaching those at the resonant frequency. Furthermore, the modulated jets demonstrate a combination of low-frequency and high-frequency characteristics, indicating that the modulated jet possesses composite frequencies. By utilizing signal modulation, a DSJA capable of generating composite-frequency jets can be designed through the selection of an appropriate piezoelectric transducer (PZT) and subsequent modulation of its vibration characteristics. These composite-frequency DSJAs can potentially be applied to control specific flow fields. Additionally, the low-frequency characteristics can directly regulate low-speed flow fields, ensuring jet frequencies that satisfy F+ ~ O(1), thereby ultimately improving the flow control effect.

4. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper presents methods for generating low-frequency and high-momentum jets based on signal modulation. The effects of two modulation methods, amplitude modulation (AM) and frequency modulation (FM), on the characteristics of dual-stenosis jet actuators (DSJAs) are investigated through experimental studies. The primary conclusions are as follows:

- By employing AM and FM, the piezoelectric transducer (PZT) can generate low-frequency vibration when subjected to a relatively high resonant frequency and a relatively low modulation frequency. Significant modulation effects on the PZT’s vibration are observed when the modulation frequency is much lower than the resonant frequency. This results in DSJAs with low-frequency characteristics and relatively high peak velocities. The peak velocity reaches 91% of that at the resonant frequency.

- Both AM and FM methods resolve the momentum–frequency coupling contradiction of a piezoelectric DSJA, resulting in composite frequencies in the modulated jets. The DSJA’s low-frequency and composite-frequency characteristics may offer new approaches and ideas for addressing flow control issues.

- Applying signal modulation enhances both the volume compression and the rate of change in volume compression at lower modulation frequencies, which significantly increases the peak velocity of jets, particularly when the modulation frequency is far from the resonant frequency. Compared to the unmodulated case, the RMS values of the PZT’s amplitude under AM and FM experience a maximum increase of 22% and 21%, respectively. The RMS values of the PZT’s vibration velocity experience a maximum increase of 86% and 97%, respectively.

The results of this paper demonstrate the modulation effect of the signal modulation method on the peak velocity. However, the findings do not address the flow field outcomes. Therefore, the flow field characteristics after modulation will be prioritized in future research. Additionally, further investigation is necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of flow control applications utilizing the signal modulation method proposed in this study. This will also be a key focus of our future work.

Additionally, only the vibration phenomenon of the piezoelectric ceramic (PZT) has been observed in this study, while the internal mechanism behind why signal modulation enables the piezoelectric ceramic (PZT) to exhibit such vibration characteristics still needs to be clarified through further research. In the process of conducting subsequent research, the Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) technique will be adopted for flow field observation to verify the effectiveness of flow control; we plan to carry out a study related to “cylinder flow control using modulated jets”.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and Z.L.; Methodology, S.L. and L.Z.; Software, S.L.; Validation, L.Z. and Z.L.; Data curation, S.L. and S.C.; Writing—original draft, S.L.; Writing—review & editing, S.L., S.C., L.Z. and Z.L.; Visualization, S.C.; Funding acquisition, S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52408506 and U2141252), the Excellent Young Fund of the Education Department of Hunan Province (23B0332).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| AM | Amplitude modulation | SJ | Synthetic jet |

| DSJ | Dual synthetic jet | SJA | Synthetic jet actuator |

| DSJA | Dual synthetic jet actuator | t | Time |

| FM | Frequency modulation | U | Voltage of the cosine driving signal |

| Frequency of the original signal | Um | Maximum voltage amplitude of the original cosine signal | |

| Modulation frequency for amplitude modulation | Voltage of the amplitude-modulated driving signal | ||

| fFM | Modulation frequency for frequency modulation | Voltage of the frequency-modulated signal | |

| Maximum deviation of the instantaneous frequency of the modulated signal relative to f | V | volt | |

| Kf | Frequency modulation sensitivity | Angular frequency | |

| Frequency modulation sensitivity, = Kf/2 | Maximum deviation of the instantaneous angular frequency of the modulated signal relative to | ||

| NM | No modulation | Instantaneous angular frequency | |

| Modulation factor for FM | Instantaneous phase | ||

| PZT | piezoelectric |

References

- Hu, P.; Wang, S.; Han, Y.; Cai, C.S.; Yuan, B.; Ding, S. Numerical simulations on flow control of the long hanger around a bridge tower based on active suction and blowing method. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 115145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Cai, S.; Xia, M.; Hu, P.; Zeng, L.; Han, Y. Control of vortex-induced vibrations in rectangular plates: The effects of suction position. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 097121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Cai, S.; Xia, M.; Hu, P.; Zeng, L.; Han, Y. Flow control of a surface-mounted finite-length square cylinder using synthetic jets. Acta Mech. Sin. 2025, 41, 325254. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Wang, K.; Cai, S.; Han, Y.; Hu, P.; Zeng, L. Numerical simulation study of vortex-induced vibration suppression for two tandem circular cylinders based on synthetic jets. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 097125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Luo, Z.; Peng, W.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Q.; Deng, X.; Zhou, Y. Single-degree-of-freedom fluid-structure interaction model of dual synthetic jets actuator. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2025, 9, 103810. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, J.; Peng, W.; Luo, Z.; Deng, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Z. Comparison of aerodynamic characteristics of wing dynamic stall under three typical jets control. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2025, 38, 103284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.L.; Glezer, A. The formation and evolution of synthetic jets. Phys. Fluids 1998, 10, 2281–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.-S.; Jukes, T.; Whalley, R. Turbulent boundary layer control with DBD plasma actuators. Philos. Trans. A 2011, 369, 1443–1458. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wen, X. Sweeping jet control of flow around a circular cylinder. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2023, 141, 110785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Wang, S.; Han, Y.; Cai, C.; Zhang, F.; Yan, N. Mechanism analysis on wake-induced vibration of parallel hangers near a long-span suspension bridge tower. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2023, 241, 105542. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.; Jeon, W.P.; Kim, J. Control of Flow Over a Bluff Body. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2008, 40, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Wang, H.; Hu, X.; Zhou, K.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, H.; Wang, Z. Flow control of D-shaped bluff bodies using attached dual membranes. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 305, 110910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojae, F.J.; Salehi, M.; Ja’FAri, M.; Jaworski, A.J.; Nia, B.B. Passive control of vortex breakdown on slender delta wing using control bump and cavity at low Reynolds number. Ocean Eng. 2025, 329, 121086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algan, M.; Seyhan, M.; Sarıoğlu, M. Effect of aero-shaped vortex generators on NACA 4415 airfoil. Ocean Eng. 2024, 291, 116482. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Deng, X.; Wang, L.; Xia, Z. Dual Synthetic Jets Actuator and Its Applications—Part I: PIV Measurements and Comparison to Synthetic Jet Actuator. Actuators 2022, 11, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Luo, Z.; Deng, X.; Liu, Z.; Gao, T.; Zhao, Z. Lift enhancement based on virtual aerodynamic shape using a dual synthetic jet actuator. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2022, 35, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ja’Fari, M.; Shojae, F.J.; Jaworski, A.J. Synthetic jet actuators: Overview and applications. Int. J. Thermofluids 2023, 20, 100438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.B.; Xia, Z.X.; Liu, B. New Generation of synthetic jet actuators. AIAA J. 2006, 44, 2418–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Luo, Z.; Xu, B.; Deng, X.; Guo, Y.; Peng, W.; Li, S. Novel lift enhancement method based on zero-mass-flux jets and its adaptive controlling laws design. Acta Mech. Sin. 2021, 37, 1567–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Luo, Z.; Deng, X.; Peng, W.; Liu, Z. Experimental investigation on active control of flow around a finite-length square cylinder using dual synthetic jet. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2021, 210, 104519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Luo, Z.; Deng, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Li, S. Effects of dual synthetic jets on longitudinal aerodynamic characteristics of a flying wing layout. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 132, 108043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhiyong, L.; Zhenbing, L.; Xianxu, Y.; Guohua, T. Review of controlling flow separation over airfoils with periodic excitation. Adv. Mech. 2020, 50, 202007. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhiyong, L.; Zhenbing, L.; Qiang, L.; Yan, Z. Modulation of driving signals in flow control over an airfoil with synthetic jet. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2020, 33, 3138–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.R.; Wang, J.S.; Wang, J.J. Numerical investigation of efficient synthetic jets generated by multiple-frequency actuating signals. Acta Mech. Sin. 2022, 38, 321177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, A.A.; Seyhan, M.; Akansu, Y. Effect of signal modulation of DBD plasma actuator on flow control around NACA 0015. J. Therm. Sci. Technol. 2018, 38, 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Benard, N.; Moreau, E. Response of a circular cylinder wake to a symmetric actuation by non-thermal plasma discharges. Exp. Fluids 2013, 54, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.X. Communication Electronic Circuits, 3rd ed.; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo, A.; de Luca, L. Experimental and CFD Characterization of a Double-Orifice Synthetic Jet Actuator for Flow Control. Actuators 2021, 10, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X. Research on Vector-Controlling Characteristic of Dual Synthetic Jets and Its Applications in Heat Transfer Enhancement; National University of Defense Technology: Changsha, China, 2015. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Seo, J.H.; Cadieux, F.; Mittal, R.; Deem, E.; Cattafesta, L. Effect of synthetic jet modulation schemes on the reduction of a laminar separation bubble. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2018, 3, 033901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayoum, A.; Gupta, V.; Panigrahi, P.; Muralidhar, K. Influence of amplitude and frequency modulation on flow created by a synthetic jet actuator. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2010, 162, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).