Interplay Between NLRP3 Activation by DENV-2 and Autophagy and Its Impact on Lipid Metabolism in HMEC-1 Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and DENV-2 Virus

2.2. Virus Quantification

2.3. Treatment with Inhibitor Glyburide and Infection Assay

2.4. Immunofluorescence Analysis (IF)

2.5. Immunoblot Analysis

2.6. Transfection of Reporter Plasmids with GPF-LC3

2.7. MTT Assay

3. Results

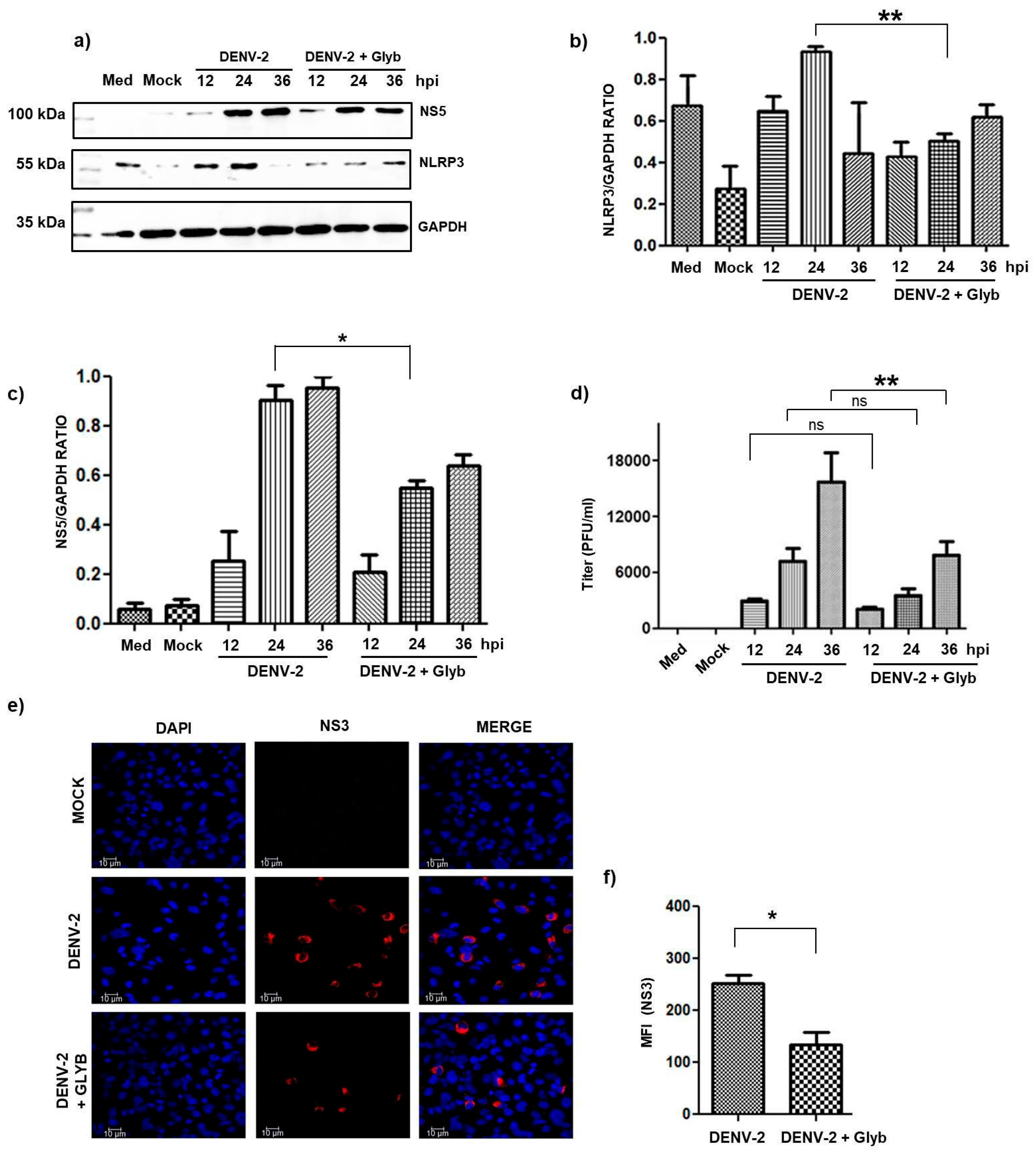

3.1. The Inhibition of NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by DENV Infection Decreased Viral Replication

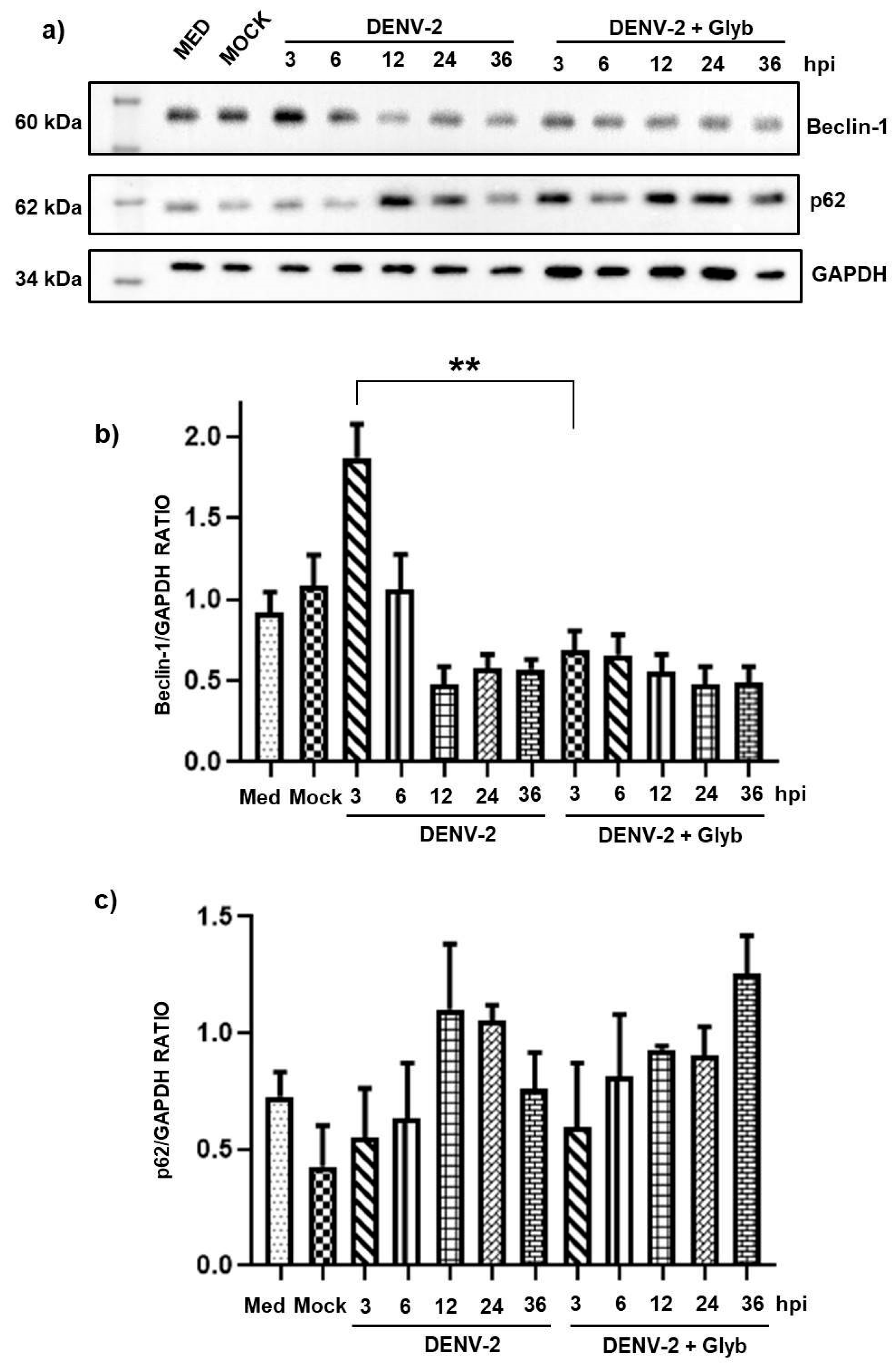

3.2. Dengue Virus Induces Autophagy Activation at Early Time Points in HMEC-1 Cells

3.3. Inhibition of the NLRP3 Inflammasome Does Not Reduce Autophagy at Early Time Points

3.4. Infection of HMEC-1 Cells with DENV Induces SREBP-1 and SREBP-2 Activation and the Expression of FAS

3.5. NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibition During DENV-2 Infection Reduces SREBP Activation and Viral Replication

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DENV | dengue virus |

| NLRP3 | NOD-like receptor (NLR) family pyrin domain containing-3 |

| HMEC-1 | human microvascular endothelial cells-1 |

| SREBP | sterol regulatory element binding proteins |

| ER | endoplasmic reticulum |

| SCAP | SREBP cleavage-activating protein |

| Nrf2 | nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2 -like 2 |

| MOI | multiplicity of infection |

| hpi | hours post-infection |

| oxLDL | oxidized low-density lipoprotein |

| HCV | hepatitis C viral virus |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| ULK1 | unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1 |

| PI3K | phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| PIK3C3/Vps34 | phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase catalytic subunit type 3/vacuolar protein-sorting 34 |

| ATG5 | autophagy-related gene 5 |

| FAS | fatty acid synthase |

| RVA | rotavirus A |

| HMGCR | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase |

References

- Álvarez-Díaz, D.A.; Gutiérrez-Díaz, A.A.; Orozco-García, E.; Puerta-González, A.; Bermúdez-Santana, C.I.; Gallego-Gómez, J.C. Dengue virus potentially promotes migratory responses on endothelial cells by enhancing pro-migratory soluble factors and miRNAs. Virus Res. 2019, 259, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuartas-López, A.M.; Hernández-Cuellar, C.E.; Gallego-Gómez, J.C. Disentangling the role of PI3K/Akt, Rho GTPase and the actin cytoskeleton on dengue virus infection. Virus Res. 2018, 256, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicenzi, E.; Pagani, I.; Ghezzi, S.; Taylor, S.L.; Rudd, T.R.; Lima, M.A.; Skidmore, M.A.; Yates, E.A. Subverting the Mechanisms of Cell Death: Flavivirus Manipulation of Host Cell Responses to Infection. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2018, 46, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez Ochoa, M.; García Cordero, J.; Gutiérrez Castañeda, B.; Santos Argumedo, L.; Villegas Sepúlveda, N.; Cedillo Barrón, L. A Clinical Isolate of Dengue Virus and Its Proteins Induce Apoptosis in HMEC-1 Cells: A Possible Implication in Pathogenesis. Arch. Virol. 2009, 154, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villordo, S.M.; Carballeda, J.M.; Filomatori, C.V.; Gamarnik, A.V. RNA Structure Duplications and Flavivirus Host Adaptation. Trends Microbiol. 2016, 24, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Acosta, R.; Bautista-Carbajal, P.; Cervantes-Salazar, M.; Angel-Ambrocio, A.H.; Del Angel, R.M. DENV Up-Regulates the HMG-CoA Reductase Activity through the Impairment of AMPK Phosphorylation: A Potential Antiviral Target. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroja-Mazo, A.; Martín-Sánchez, F.; Gomez, A.I.; Martínez, C.M.; Amores-Iniesta, J.; Compan, V.; Barberà-Cremades, M.; Yagüe, J.; Ruiz-Ortiz, E.; Antón, J.; et al. The NLRP3 Inflammasome Is Released as a Particulate Danger Signal That Amplifies the Inflammatory Response. Nat. Immunol. 2014, 15, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhu, X.; An, S.; Dong, X.; Yu, J.; Zhang, S.; Wu, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, Y.; et al. NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation Mediates Zika Virus-Associated Inflammation. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 217, 1942–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Callaway, J.B.; Ting, J.P.Y. Inflammasomes: Mechanism of Action, Role in Disease, and Therapeutics. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.F.; Chen, S.T.; Yang, A.H.; Lin, W.W.; Lin, Y.L.; Chen, N.J.; Tsai, I.S.; Li, L.; Hsieh, S.L. CLEC5A Is Critical for Dengue Virus-Induced Inflammasome Activation in Human Macrophages. Blood 2013, 121, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.Y.; Chu, J.J.H. Dengue Virus-Infected Human Monocytes Trigger Late Activation of Caspase-1, Which Mediates pro-Inflammatory IL-1β Secretion and Pyroptosis. J. Gen. Virol. 2013, 94, 2215–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beese, C.J.; Brynjólfsdóttir, S.H.; Frankel, L.B. Selective Autophagy of the Protein Homeostasis Machinery: Ribophagy, Proteaphagy and ER-Phagy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaid, S.; Brandts, C.H.; Serve, H.; Dikic, I. Ubiquitination and Selective Autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2013, 20, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lan, Y.; Li, M.Y.; Lamers, M.M.; Fusade-Boyer, M.; Klemm, E.; Thiele, C.; Ashour, J.; Sanyal, S. Flaviviruses Exploit the Lipid Droplet Protein AUP1 to Trigger Lipophagy and Drive Virus Production. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 819–831.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.; Ahn, J.H.; Park, H.H.; Kim, H.N.; Kim, H.; Yoo, Y.; Shin, H.; Hong, K.S.; Jang, J.G.; Park, C.G.; et al. COVID-19-Activated SREBP2 Disturbs Cholesterol Biosynthesis and Leads to Cytokine Storm. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2020, 5, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Pan, X.; Cheng, C.; Liu, B.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, K. Regulation of SREBP-2 Intracellular Trafficking Improves Impaired Autophagic Flux and Alleviates Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in NAFLD. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2017, 1862, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; Wu, J.; Goldstein, J.L.; Brown, M.S.; Hobbs, H.H. Structure of the Human Gene Encoding Sterol Regulatory Element Binding Protein-1 (SREBF1) and Localization of SREBF1 and SREBF2 to Chromosomes 17p11.2 and 22q13. Genomics 1995, 25, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.S.; Goldstein, J.L. The SREBP Pathway: Regulation of Cholesterol Metabolism by Proteolysis of a Membrane-Bound Transcription Factor. Cell 1997, 89, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, J.D.; Goldstein, J.L.; Brown, M.S. SREBPs: Activators of the Complete Program of Cholesterol and Fatty Acid Synthesis in the Liver. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 109, 1125–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, L.; Zhu, L.; Liu, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhao, M. Lipid Droplets, the Central Hub Integrating Cell Metabolism and the Immune System. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 746749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, V.C.; Dias, S.S.G.; Santos, J.C.; Azevedo-Quintanilha, I.G.; Moreira, I.B.G.; Sacramento, C.Q.; Fintelman-Rodrigues, N.; Temerozo, J.R.; da Silva, M.A.N.; Barreto-Vieira, D.F.; et al. Inhibition of the SREBP Pathway Prevents SARS-CoV-2 Replication and Inflammasome Activation. Life Sci. Alliance 2023, 6, e202302049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.H.; Lin, X.L.; Xiao, L.L. SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein Promotes TMAO-Induced NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by SCAP-SREBP Signaling Pathway. Tissue Cell. 2024, 86, 102276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Wright, R.E.; Giri, S.; Arumugaswami, V.; Kumar, A. Targeting ABCG1 and SREBP-2 Mediated Cholesterol Homeostasis Ameliorates Zika Virus-Induced Ocular Pathology. iScience 2024, 27, 109088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, S.S.; Yousef, L.; Blaschitz, C.; Liu, J.Z.; Edwards, R.A.; Young, S.G.; Raffatellu, M.; Osborne, T.F. Linking Lipid Metabolism to the Innate Immune Response in Macrophages through Sterol Regulatory Element Binding Protein-1a. Cell Metab. 2011, 13, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, A.; Naveed, M.A.; Akram, L.; Sharif, M.; Kang, M.I.; Park, S.I. Rotavirus Exploits SREBP Pathway for Hyper Lipid Biogenesis during Replication. J. Gen. Virol. 2022, 103, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos-Arriaga, J.; García-Machorro, J.; León-Juárez, M.; García-Cordero, J.; Santos-Argumedo, L.; Flores-Romo, L.; Méndez-Cruz, A.R.; Juárez-Delgado, F.J.; Cedillo-Barrón, L. Activation of the Innate Immune Response against DENV in Normal Non-Transformed Human Fibroblasts. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2011, 5, e1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cordero, J.; Ramirez, H.R.; Vazquez-Ochoa, M.; Gutierrez-Castañeda, B.; Santos-Argumedo, L.; Villegas-Sepúlveda, N.; Cedillo-Barrón, L. Production and characterization of a monoclonal antibody specific for NS3 protease and the ATPase region of Dengue-2 virus. Hybridoma 2005, 24, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, G.; Visoso-Carvajal, G.; Garcia-Cordero, J.; Leon-Juarez, M.; Chavez-Munguia, B.; Lopez, T.; Nava, P.; Villegas-Sepulveda, N.; Cedillo-Barron, L. Dengue Virus Serotype 2 and Its Non-Structural Proteins 2A and 2B Activate NLRP3 Inflammasome. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, T.S.; Sun, D.S.; Wu, C.Y.; Chang, H.H. Exposure to Dengue Envelope Protein Domain III Induces Nlrp3 Inflammasome-Dependent Endothelial Dysfunction and Hemorrhage in Mice. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 617251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, T.S.; Chan, H.; Sun, D.S.; Wu, J.C.; Lin, Y.Y.; Lin, G.L.; Chang, H.H. Exposure of Platelets to Dengue Virus and Envelope Protein Domain III Induces Nlrp3 Inflammasome-Dependent Platelet Cell Death and Thrombocytopenia in Mice. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 616394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, W.; Wang, W.; Lao, Z.; Zhang, W.; Shen, M.; Wan, P.; Xiao, F.; Liu, F.; et al. Dengue Virus M Protein Promotes NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation to Induce Vascular Leakage in Mice. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00996–e01019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, A.; Li, B.; Kombe, A.J.K.; Jin, T.; Tao, J. Pharmacological Inhibitors of the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jounai, N.; Kobiyama, K.; Shiina, M.; Ogata, K.; Ishii, K.J.; Takeshita, F. NLRP4 Negatively Regulates Autophagic Processes through an Association with Beclin1. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 1646–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloherty, A.P.M.; Olmstead, A.D.; Ribeiro, C.M.S.; Jean, F. Hijacking of Lipid Droplets by Hepatitis C, Dengue and Zika Viruses-from Viral Protein Moonlighting to Extracellular Release. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, J.; Harris, E. Early Dengue Virus Protein Synthesis Induces Extensive Rearrangement of the Endoplasmic Reticulum Independent of the UPR and SREBP-2 Pathway. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvedev, R.; Ploen, D.; Spengler, C.; Elgner, F.; Ren, H.; Bunten, S.; Hildt, E. HCV-Induced Oxidative Stress by Inhibition of Nrf2 Triggers Autophagy and Favors Release of Viral Particles. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 110, 300–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Gillette, D.D.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wen, H. Nuclear factor E2-related factor-2 (Nrf2) is required for NLRP3 and AIM2 inflammasome activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 17020–17029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhang, J.J.; Yen, G.C. The role of Nrf2 in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2017, 14, 1011–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaton, N.S.; Randall, G. Dengue Virus-Induced Autophagy Regulates Lipid Metabolism. Cell Host Microbe 2010, 8, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panyasrivanit, M.; Greenwood, M.P.; Murphy, D.; Isidoro, C.; Auewarakul, P.; Smith, D.R. Induced Autophagy Reduces Virus Output in Dengue Infected Monocytic Cells. Virology 2011, 418, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, T.S.; de Sá, K.S.G.; Ishimoto, A.Y.; Becerra, A.; Oliveira, S.; Almeida, L.; Gonçalves, A.V.; Perucello, D.B.; Andrade, W.A.; Castro, R.; et al. Inflammasomes Are Activated in Response to SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Are Associated with COVID-19 Severity in Patients. J. Exp. Med. 2021, 218, e20201707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pombo, J.P.; Sanyal, S. Perturbation of Intracellular Cholesterol and Fatty Acid Homeostasis During Flavivirus Infections. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, J.F.; Patel, R.; Yadav, U.C.S. Sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP)-1 mediates oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) induced macrophage foam cell formation through NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell. Signal. 2019, 53, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Cordero, J.; León Juárez, M.; González-Y.-Merchand, J.A.; Cedillo Barrón, L.; Gutiérrez Castañeda, B. Caveolin-1 in lipid rafts interacts with dengue virus NS3 during polyprotein processing and replication in HMEC-1 cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Chi, Z.; Jiang, D.; Xu, T.; Yu, W.; Wang, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Q.; Guo, X.; et al. Cholesterol Homeostatic Regulator SCAP-SREBP2 Integrates NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Cholesterol Biosynthetic Signaling in Macrophages. Immunity 2018, 49, 842–856.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Hoffman, B.; Liu, Q. PI3K-Akt signaling pathway upregulates hepatitis C virus RNA translation through the activation of SREBPs. Virology 2016, 490, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todoric, J.; Di Caro, G.; Reibe, S.; Henstridge, D.C.; Green, C.R.; Vrbanac, A.; Ceteci, F.; Conche, C.; McNulty, R.; Shalapour, S.; et al. Fructose stimulated de novo lipogenesis is promoted by inflammation. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 1034–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurcel, L.; Abrami, L.; Girardin, S.; Tschopp, J.; van der Goot, F.G. Caspase-1 activation of lipid metabolic pathways in response to bacterial pore-forming toxins promotes cell survival. Cell 2006, 126, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, P.K. From fat to fire: The lipid-inflammasome connection. Immunol. Rev. 2025, 329, e13403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.L.; Lin, Y.S.; Chen, C.L.; Tsai, T.T.; Tsai, C.C.; Wu, Y.W.; Ou, Y.D.; Chu, Y.Y.; Wang, J.M.; Yu, C.Y.; et al. Activation of Nrf2 by the dengue virus causes an increase in CLEC5A, which enhances TNF-α production by mononuclear phagocytes. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Tabbi-Anneni, I.; Gunda, V.; Wang, L. Transcription factor Nrf2 regulates SHP and lipogenic gene expression in hepatic lipid metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2010, 299, G1211–G1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M.; Zevini, A.; Palermo, E.; Muscolini, M.; Alexandridi, M.; Etna, M.P.; Coccia, E.M.; Fernandez-Sesma, A.; Coyne, C.; Zhang, D.D.; et al. Dengue Virus Targets Nrf2 for NS2B3-Mediated Degradation Leading to Enhanced Oxidative Stress and Viral Replication. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e01551-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Liang, Z.; Wu, Q.; Wang, M.; Yang, M.; Chen, C.; Zheng, H.; Zhu, Z.; Li, L.; Yang, G. Hepatic lipid accumulation induced by a high-fat diet is regulated by Nrf2 through multiple pathways. FASEB J. 2022, 36, e22280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Nan, X.; Shi, X.; Mu, X.; Liu, B.; Zhu, H.; Yao, B.; Liu, X.; Yang, T.; Hu, Y.; et al. SREBP1 promotes the invasion of colorectal cancer accompanied upregulation of MMP7 expression and NF-κB pathway activation. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, H.R.; Jo, Y.H.; Kim, J.; Shin, Y.; Kim, S.S.; Choi, T.G. Roles of Autophagy in Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Ding, Z.; Du, K.; Ye, X.; Cheng, S. Reactive Oxygen Species as a Link between Antioxidant Pathways and Autophagy. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 5583215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Feng, C.; Jiang, H. Novel target for treating Alzheimer’s Diseases: Crosstalk between the Nrf2 pathway and autophagy. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 65, 101207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Visoso-Carvajal, G.; García-Cordero, J.; Ybalmea-Gómez, Y.; Diaz-Flores, M.; León-Juárez, M.; Hernández-Rivas, R.; Nava, P.; Villegas-Sepúlveda, N.; Cedillo-Barrón, L. Interplay Between NLRP3 Activation by DENV-2 and Autophagy and Its Impact on Lipid Metabolism in HMEC-1 Cells. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1292. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121292

Visoso-Carvajal G, García-Cordero J, Ybalmea-Gómez Y, Diaz-Flores M, León-Juárez M, Hernández-Rivas R, Nava P, Villegas-Sepúlveda N, Cedillo-Barrón L. Interplay Between NLRP3 Activation by DENV-2 and Autophagy and Its Impact on Lipid Metabolism in HMEC-1 Cells. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1292. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121292

Chicago/Turabian StyleVisoso-Carvajal, Giovani, Julio García-Cordero, Yandy Ybalmea-Gómez, Margarita Diaz-Flores, Moisés León-Juárez, Rosaura Hernández-Rivas, Porfirio Nava, Nicolás Villegas-Sepúlveda, and Leticia Cedillo-Barrón. 2025. "Interplay Between NLRP3 Activation by DENV-2 and Autophagy and Its Impact on Lipid Metabolism in HMEC-1 Cells" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1292. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121292

APA StyleVisoso-Carvajal, G., García-Cordero, J., Ybalmea-Gómez, Y., Diaz-Flores, M., León-Juárez, M., Hernández-Rivas, R., Nava, P., Villegas-Sepúlveda, N., & Cedillo-Barrón, L. (2025). Interplay Between NLRP3 Activation by DENV-2 and Autophagy and Its Impact on Lipid Metabolism in HMEC-1 Cells. Pathogens, 14(12), 1292. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121292