Effects of MAPK Homologous Genes on Chemotaxis and Egg Hatching in Meloidogyne incognita

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Culture of Tomato and of Meloidogyne incognita

2.2. RNA Interference of Genes Associated with Chemotaxis and Egg Hatching in Meloidogyne incognita

2.3. Chemotaxis Assay of Meloidogyne incognita

2.4. Tomato Pot Experiment with Meloidogyne incognita

2.5. Egg Hatching Assay of Meloidogyne incognita

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

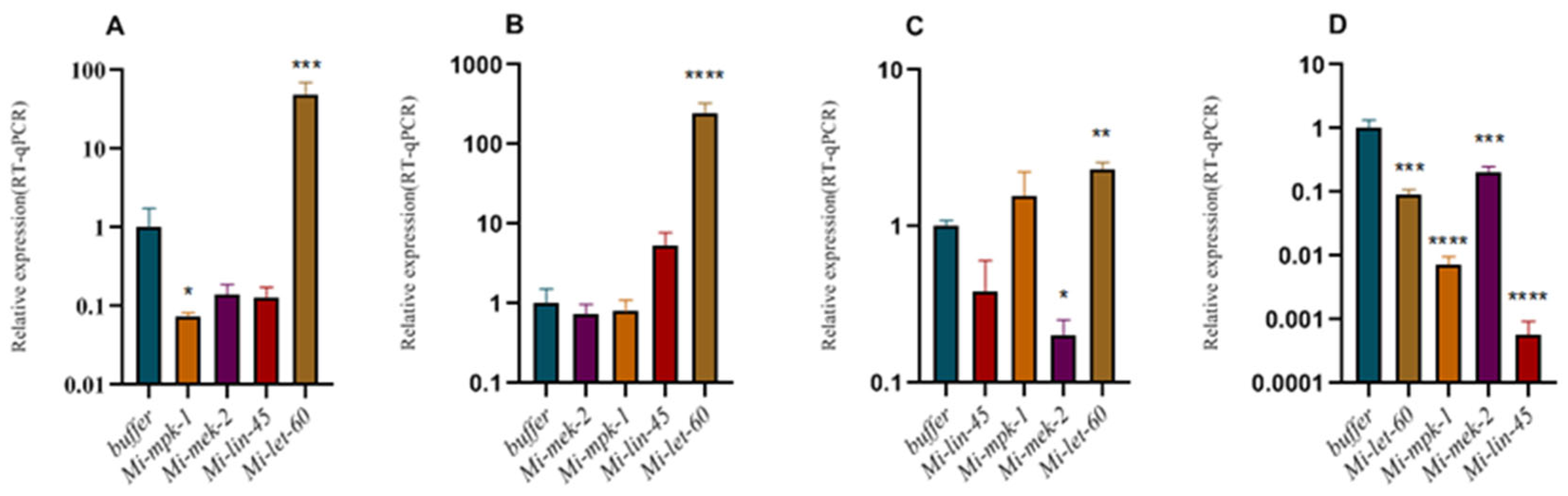

3.1. RNAi of MAPK Genes in Meloidogyne incognita

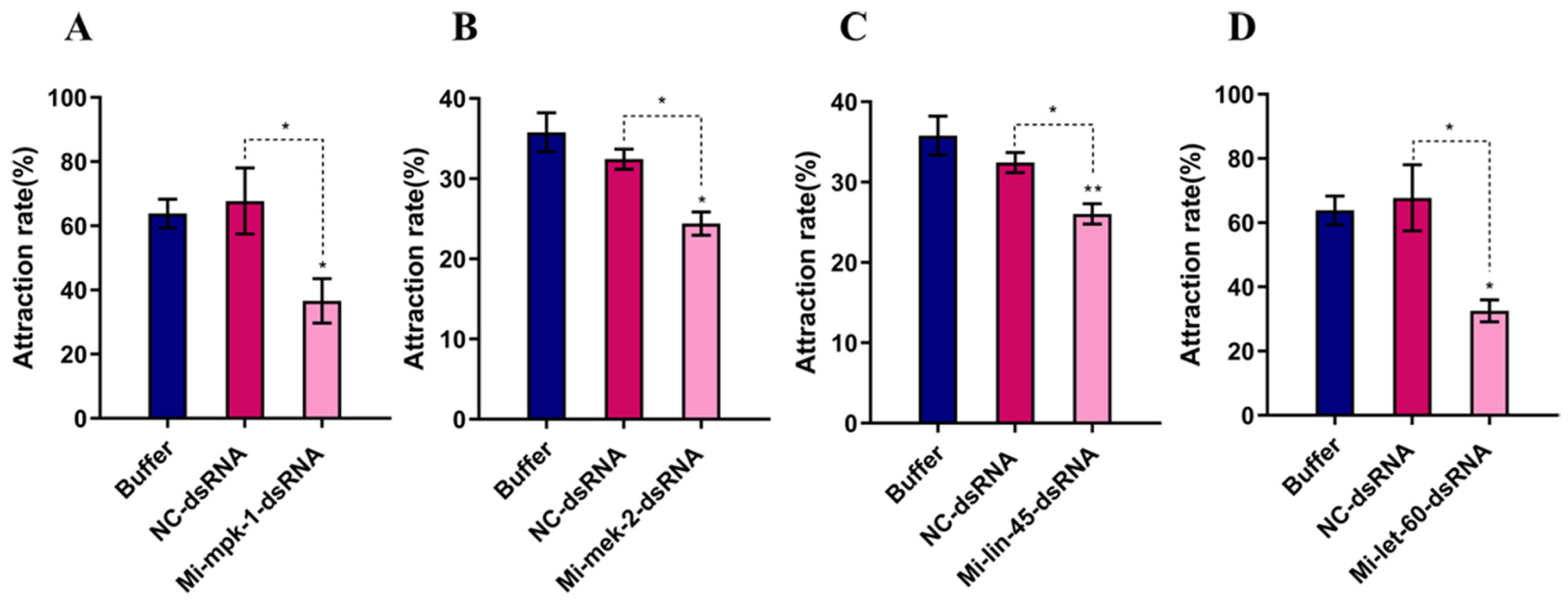

3.2. Chemotactic Activity of Meloidogyne incognita After RNAi

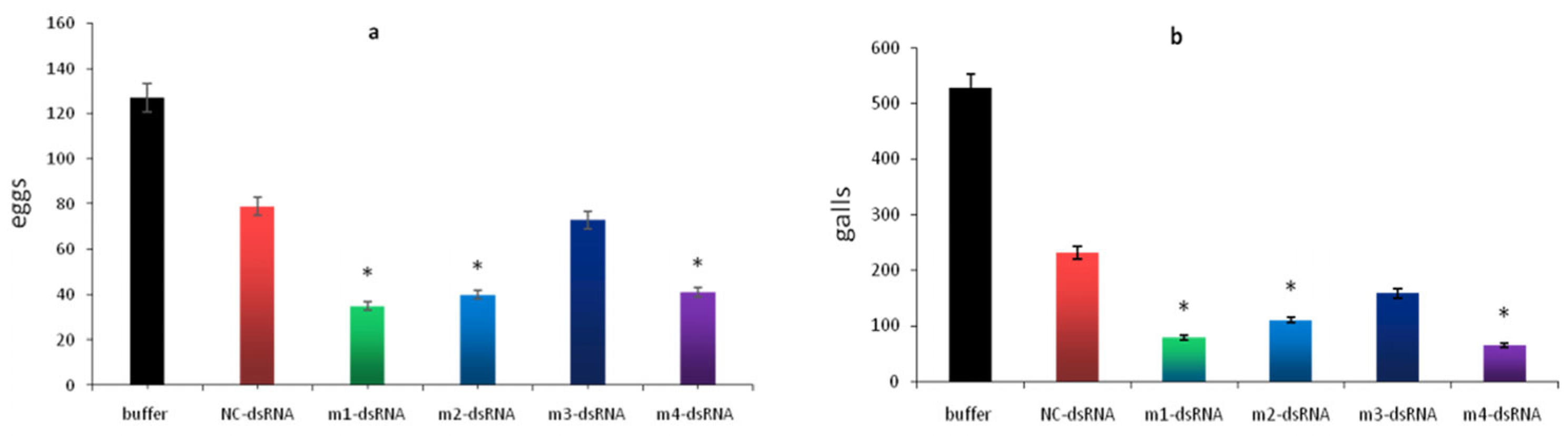

3.3. Effect of MAPK Genes on Egg Hatching Ability in Meloidogyne incognita

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coyne, D.L.; Cortada, L.; Dalzell, J.J.; Claudius-Cole, A.O.; Haukeland, S.; Luanobano, N.; Talwana, H. Plant-Parasitic Nematodes and Food Security in Sub-Saharan Africa. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2018, 56, 381–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widmann, C.; Gibson, S.; Jarpe, M.B.; Johnson, G.L. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase: Conservation of a Three-Kinase Module from Yeast to Human. Physiol. Rev. 1999, 79, 143–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumienny, T.L.; Lambie, E.; Hartwigg, E.; Horvitz, H.R.; Hengartner, M.O. Genetic Control of Programmed Cell Death in the Caenorhabditis elegans Hermaphrodite Germline. Development 1999, 126, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Donlevy, S.; Smolikovs, S. Coordination of Recombination with Meiotic Progression in the Caenorhabditis elegans Germline by KIN-18, a TAO Kinase That Regulates the Timing of MPK-1 Signaling. Genetics 2016, 202, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aobaobe, H.; Laurent, L.; Hecker-Mimoun, Y.; Ishkaveh, H.; Rappaport, Y.; Kroizer, E.; Colaiácovo, M.P.; Tzur, Y.B. Progression of Meiosis Is Coordinated by the Level and Location of MAPK Activation Via OGR-2 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 2019, 212, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Gibson, T.B.; Robinson, F.; Silvestro, L.; Pearson, G.; Xu, B.E.; Wright, A.; Vanderbilt, C.; Cobb, M.H. MAP Kinases. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 2449–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirotsu, T.; Saeki, S.; Yamamoto, M.; Iino, Y. The Ras-MAPK Pathway Is Important for Olfaction in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 2000, 404, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battu, G.; Hoier, E.F.; Hajnal, A. The C. elegans G-Protein-Coupled Receptor SRA-13 Inhibits RAS/MAPK Signalling, during Olfaction and Vulval Development. Development 2003, 130, 2567–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirotsu, T.; Into, Y. Neural Circuit-Dependent Odor Adaptation in C. elegans Is Regulated by the Ras-MAPK Pathway. Genes Cells 2005, 10, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Fu, Y.; Ren, M.; Xiao, B.; Rubin, C.S. A RasGRP, C. elegans RGEF-1b, Couples External Stimuli to Behavior by Activating LET-60 (Ras) in Sensory Neurons. Neuron 2011, 70, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Suzuki, K.; Kuultongo, H.; Tomioka, M.; Into, Y. Multiple p38/JNK Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Signaling Pathways Mediate Salt Chemotaxis Learning in C. elegans. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2023, 13, jkad129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson-Thiewes, S.; McCloskey, J.; Kimble, J. Two Classes of Active Transcription Sites and Their Roles in Developmental Regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 26812–26821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achache, H.; Falk, R.; Lerner, N.; Beatus, T.; Tzur, Y.B. Oocyte Aging Is Controlled by Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Signaling. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogra, D.; Kulalert, W.; Schroeder, F.C.; Kim, D.H. Neuronal KGB-1 JNK MAPK Signaling Regulates the Dauer Developmental Decision in Response to Environmental Stress in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 2022, 220, iyab186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.-S.-Z. Cloning and RNAi Analysis of the Me-mapk1 Gene in Meloidogyne enterology. Master’s Thesis, Hainan University, Haikou, Hainan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.-D.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Li, L. Cloning of mapk Gene from Busasphelenchus xylophyllus and Its RNAi Effect. Acta Phytopathol. Sin. 2016, 46, 662–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Cloning and Preliminary Functional Analysis of the let-60 Gene Encoding Ras Protein in Meloidogyne incognita. Master’s Thesis, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Xie, B. RNA interference effect on mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) gene in Meloidogyne incognita. Acta Phytopathol. Sin. 2008, 38, 509–513. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, L.; Xu, J.; Chen, S.; Li, X.; Zuo, Y. Mi-flp-18 and Mi-mpk-1 Genes Are Potential Targets for Meloidogyne incognita Control. J. Parasitol. 2016, 102, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Bruening, G.; Williamson, V.M. Determination of Preferred pH for Root-Knot Nematode Aggregation Using Pluronic F-127 Gel. J. Chem. Ecol. 2009, 35, 1242–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmann, S.; Ali, J.G.; Helder, J.; van der Putten, W.H. Ecology and Evolution of Soil Nematode Chemotaxis. J. Chem. Ecol. 2012, 38, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igwe, Y.; Huang, M.; Qiu, R.; Liao, J.; Wu, Q.; Du, W.; Peng, D. Full-Length Transcriptome Analysis of Soybean Cyst Nematode (Heterodera glycines) Reveals an Association of Behaviors in Response to Attractive pH and Salt Solutions with Activation of Transmembrane Receptors, Ion Channels, and Ca²⁺ Transporters. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 8778–8796. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, R.H.C. Plant-Nematode Interactions: Environmental Signals Detected by the Nematode’s Chemosensory Organs Control Changes in the Surface Cuticle and Behavior. Parasite 2008, 15, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, S.; Coomer, A.; Baum, T.; Williamson, V.M. Recognition and Response in Plant-Nematode Interactions. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2022, 60, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wei, Y.Y.; Zhang, X.; Xie, J.; Hu, Z.; Sun, R.F. Advances in Chemotaxis of Meloidogyne spp. Chin. J. Resuc. Sci. 2022, 24, 982–996. [Google Scholar]

- Causarello, M.; Roux, P.P. Activation and Function of the MAPKs and Their Substrates, the MAPK-Activated Protein Kinases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011, 75, 50–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, M.V. RTK/Ras/MAPK Signaling. WormBook 2006, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; López, J.M. Understanding MAPK Signaling Pathways in Apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Liu, M.; Li, J.; Hu, C.; Liu, Y. Effects of MAPK Homologous Genes on Chemotaxis and Egg Hatching in Meloidogyne incognita. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1290. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121290

Wang Y, Liu M, Li J, Hu C, Liu Y. Effects of MAPK Homologous Genes on Chemotaxis and Egg Hatching in Meloidogyne incognita. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1290. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121290

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Youjing, Mingxin Liu, Jiefang Li, Caiwei Hu, and Yajun Liu. 2025. "Effects of MAPK Homologous Genes on Chemotaxis and Egg Hatching in Meloidogyne incognita" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1290. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121290

APA StyleWang, Y., Liu, M., Li, J., Hu, C., & Liu, Y. (2025). Effects of MAPK Homologous Genes on Chemotaxis and Egg Hatching in Meloidogyne incognita. Pathogens, 14(12), 1290. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121290