Identification of Oral Microbiome Biomarkers Associated with Lung Cancer Diagnosis and Radiotherapy Response Prediction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Sample Collection and Storage

2.3. Clinical Data Collection

2.4. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

2.5. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.6. Follow up and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Basic Characteristics of the Enrolled Subjects

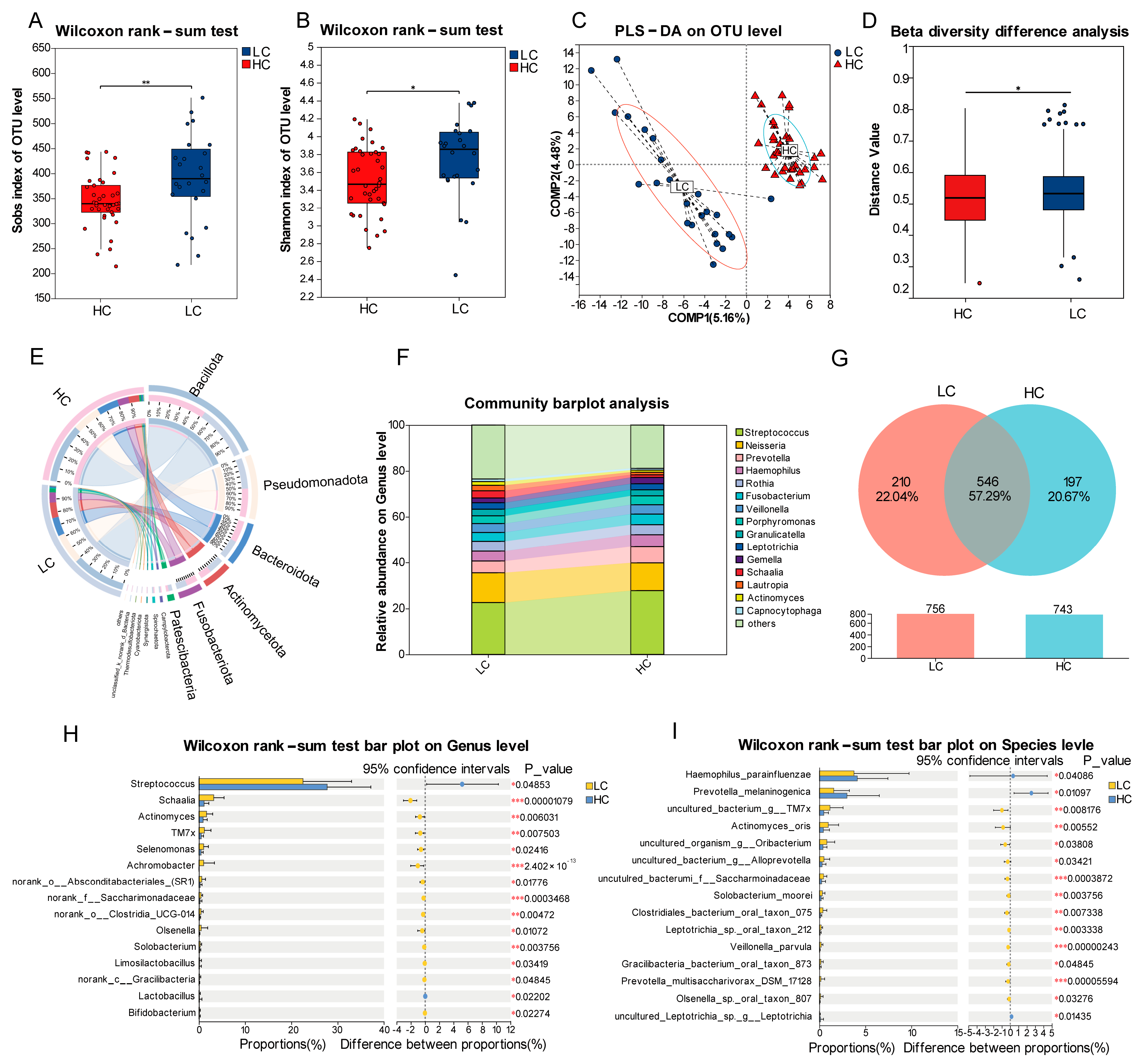

3.2. Baseline Oral Microbiota in Lung Cancer Patients Versus Matched Healthy Controls

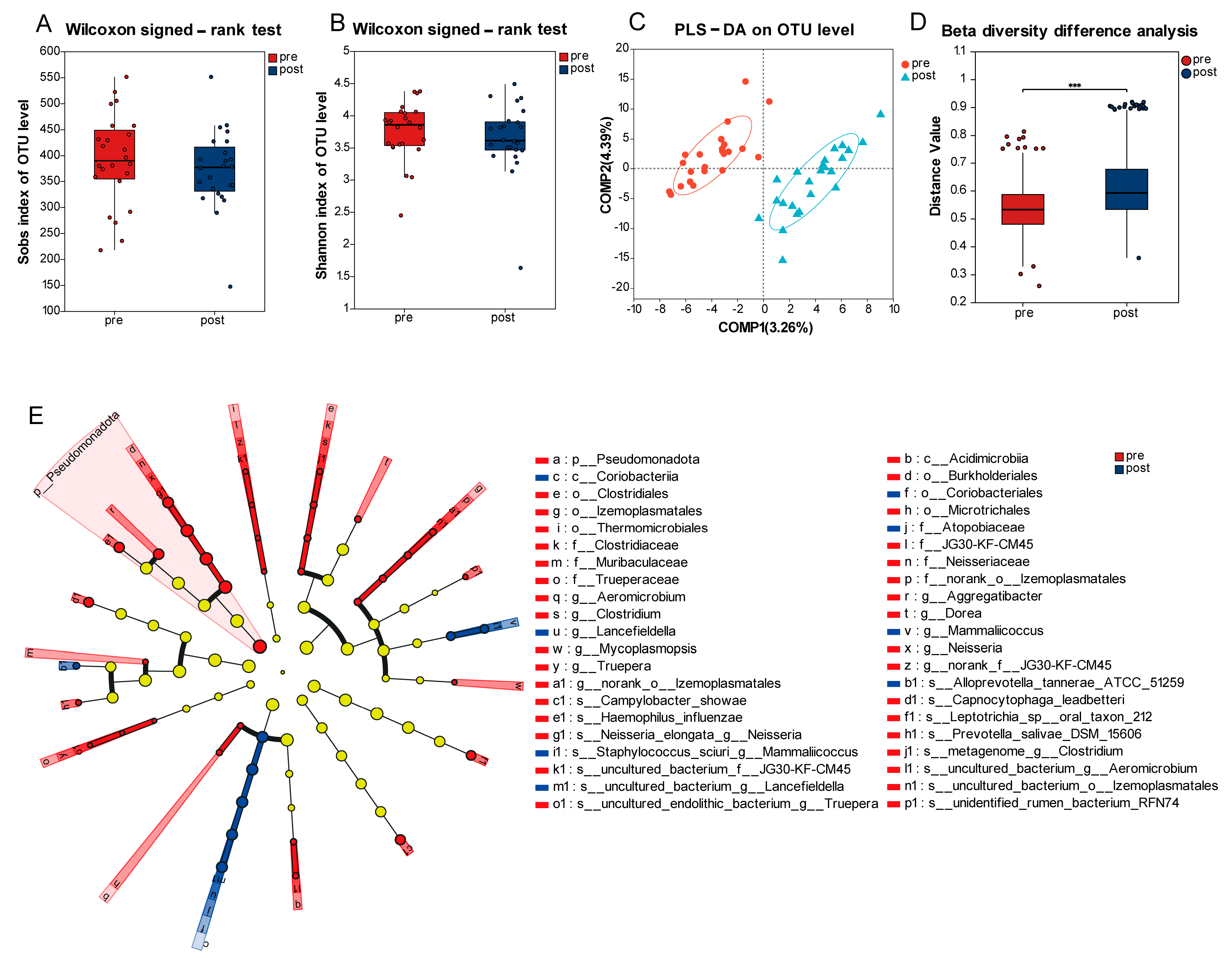

3.3. Longitudinal Variation of Oral Microbiome Profiles Pre- and Post-Radiotherapy

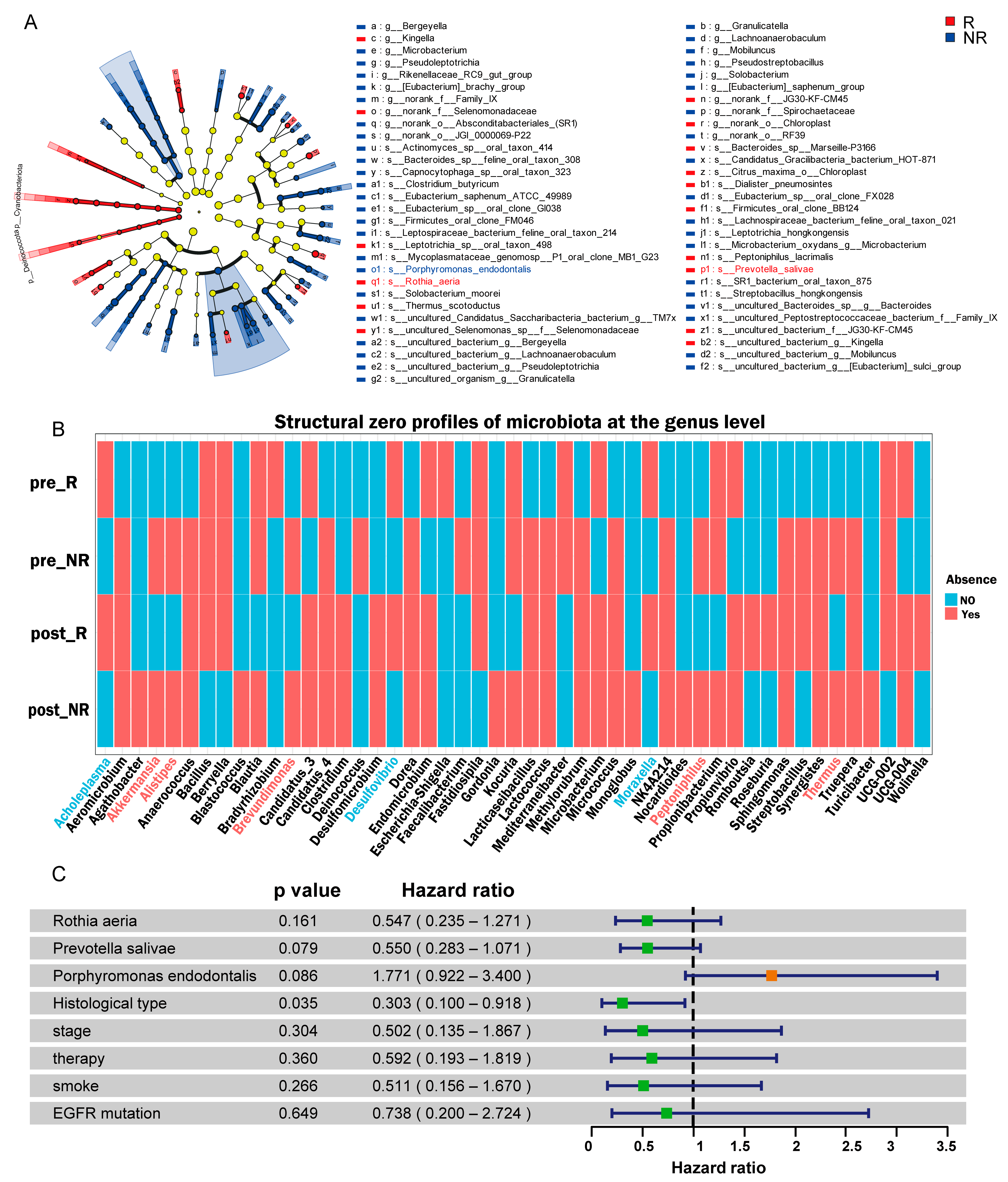

3.4. Identification of Microbial Taxa Associated with Treatment Response

3.5. Negative Correlation of Oral Microbiota Richness and Diversity with ECOG Score and ProGRP Levels

3.6. Construction of Lung Cancer Diagnosis Model and Treatment Response Prediction Model

3.7. Association of Species-Level Microbiota with OS and PFS

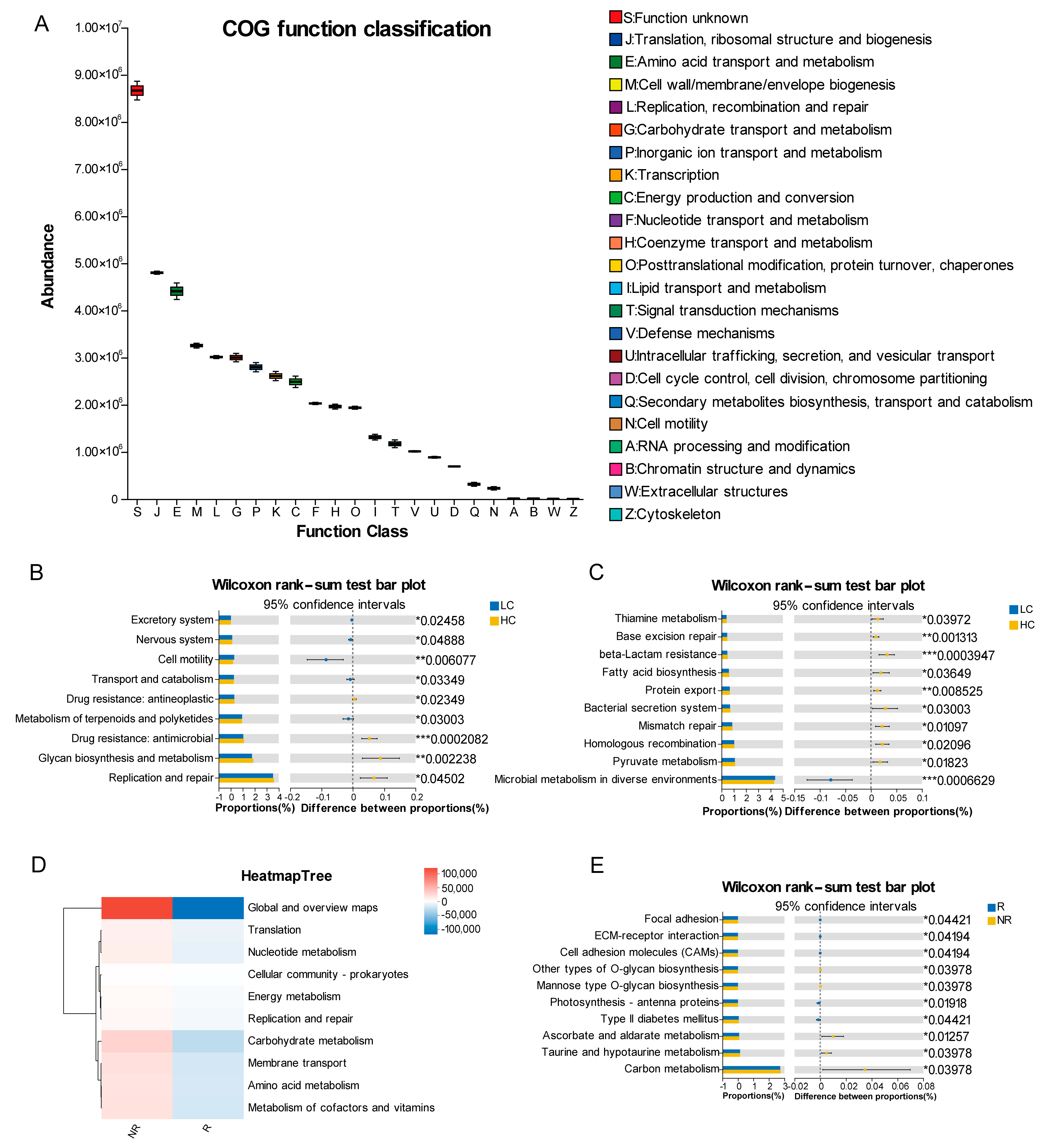

3.8. PICRUSt2 Predicts the Functions of Microbial Communities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| SCLC | Small cell lung cancer |

| ECOG | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group |

| ProGRP | Pro-gastrin-releasing peptide |

| OTUs | Operational taxonomic units |

| PLS-DA | Partial least squares discriminant analysis |

| LEfSe | Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size |

| ANCOM-BC2 | Analysis of Compositions of Microbiomes with Bias Correction 2 |

| VIF | Variance inflation factors |

| db-RDA | Distance-based redundancy analysis |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| PICRUSt2 | Phylogenetic investigation of communities by reconstruction of unobserved states 2 |

| R | Responders |

| NR | Non-responders |

| LC | Lung cancer |

| HC | Healthy control |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| EGFR-TKIs | Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

| COG | Clusters of Orthologous Groups |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| PDAC | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiter, A.; Veluswamy, R.R.; Wisnivesky, J.P. The global burden of lung cancer: Current status and future trends. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 20, 624–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamoto, S.; Nagao-Kitamoto, H.; Hein, R.; Schmidt, T.M.; Kamada, N. The Bacterial Connection between the Oral Cavity and the Gut Diseases. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Chen, Y.; Li, C.; Yang, S.; Lin, L.; Zhang, X.; Su, X.; Liu, L.; Zhao, H.; Luo, T.; et al. Variations in salivary microbiome and metabolites are associated with immunotherapy efficacy in patients with advanced NSCLC. mSystems 2025, 10, e0111524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.Y.; Hong, S.; Hwang, K.H.; Lim, E.J.; Han, J.Y.; Nam, Y.D. Diagnostic and prognostic potential of the oral and gut microbiome for lung adenocarcinoma. Clin. Transl. Med. 2021, 11, e508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abola, I.; Gudra, D.; Ustinova, M.; Fridmanis, D.; Emulina, D.E.; Skadins, I.; Brinkmane, A.; Lauga-Tunina, U.; Gailite, L.; Auzenbaha, M. Oral Microbiome Traits of Type 1 Diabetes and Phenylketonuria Patients in Latvia. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Tan, Y.; An, T.; Zhuo, M.; Pan, Z.; Ma, M.; Jia, B.; Zhang, H.; et al. Characterization of Lung and Oral Microbiomes in Lung Cancer Patients Using Culturomics and 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0031423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Song, Q.; Zhang, C.; Li, M.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xu, L.; Xie, X.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, R.; et al. Saliva microbiome alterations in dental fluorosis population. J. Oral Microbiol. 2023, 15, 2180927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhao, D.; Ma, W.; Guo, Y.; Wang, A.; Wang, Q.; Lee, D.-J. Denitrifying sulfide removal process on high-salinity wastewaters in the presence of Halomonas sp. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 100, 1421–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magoč, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. UPARSE: Highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 996–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloss, P.D.; Westcott, S.L.; Ryabin, T.; Hall, J.R.; Hartmann, M.; Hollister, E.B.; Lesniewski, R.A.; Oakley, B.B.; Parks, D.H.; Robinson, C.J.; et al. Introducing mothur: Open-Source, Platform-Independent, Community-Supported Software for Describing and Comparing Microbial Communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7537–7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Peddada, S.D. Multigroup analysis of compositions of microbiomes with covariate adjustments and repeated measures. Nat. Methods 2023, 21, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, G.M.; Maffei, V.J.; Zaneveld, J.R.; Yurgel, S.N.; Brown, J.R.; Taylor, C.M.; Huttenhower, C.; Langille, M.G.I. PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukundan, D.; Ecevit, Z.; Patel, M.; Marrs, C.F.; Gilsdorf, J.R. Pharyngeal Colonization Dynamics of Haemophilus influenzae and Haemophilus haemolyticus in Healthy Adult Carriers. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 3207–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, S.H.; Satagopan, J.; Xu, Y.; Ling, L.; Leong, S.; Orlow, I.; Saldia, A.; Li, P.; Nunes, P.; Madonia, V.; et al. The oral microbiota in patients with pancreatic cancer, patients with IPMNs, and controls: A pilot study. Cancer Causes Control 2017, 28, 959–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawamoto, D.; Borges, R.; Ribeiro, R.A.; de Souza, R.F.; Amado, P.P.P.; Saraiva, L.; Horliana, A.C.R.T.; Faveri, M.; Mayer, M.P.A. Oral Dysbiosis in Severe Forms of Periodontitis Is Associated with Gut Dysbiosis and Correlated with Salivary Inflammatory Mediators: A Preliminary Study. Front. Oral Health 2021, 2, 722495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mager, D.L.; Haffajee, A.D.; Devlin, P.M.; Norris, C.M.; Posner, M.R.; Goodson, J.M. The salivary microbiota as a diagnostic indicator of oral cancer: A descriptive, non-randomized study of cancer-free and oral squamous cell carcinoma subjects. J. Transl. Med. 2005, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallen, Z.D.; Demirkan, A.; Twa, G.; Cohen, G.; Dean, M.N.; Standaert, D.G.; Sampson, T.R.; Payami, H. Metagenomics of Parkinson’s disease implicates the gut microbiome in multiple disease mechanisms. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yachida, S.; Mizutani, S.; Shiroma, H.; Shiba, S.; Nakajima, T.; Sakamoto, T.; Watanabe, H.; Masuda, K.; Nishimoto, Y.; Kubo, M.; et al. Metagenomic and metabolomic analyses reveal distinct stage-specific phenotypes of the gut microbiota in colorectal cancer. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, N.; van Passel, M.W.J.; Kant, R.; Zoetendal, E.G.; Plugge, C.M.; Derrien, M.; Malfatti, S.A.; Chain, P.S.G.; Woyke, T.; Palva, A.; et al. The Genome of Akkermansia muciniphila, a Dedicated Intestinal Mucin Degrader, and Its Use in Exploring Intestinal Metagenomes. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belzer, C.; de Vos, W.M. Microbes inside—From diversity to function: The case of Akkermansia. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1449–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derosa, L.; Routy, B.; Thomas, A.M.; Iebba, V.; Zalcman, G.; Friard, S.; Mazieres, J.; Audigier-Valette, C.; Moro-Sibilot, D.; Goldwasser, F.; et al. Intestinal Akkermansia muciniphila predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routy, B.; Le Chatelier, E.; Derosa, L.; Duong, C.P.M.; Alou, M.T.; Daillère, R.; Fluckiger, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Rauber, C.; Roberti, M.P.; et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 2018, 359, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Qian, X.; Chen, S.; Fu, X.; Ma, G.; Zhang, A. Akkermansia muciniphila Enhances the Antitumor Effect of Cisplatin in Lewis Lung Cancer Mice. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Zou, Y.; Gong, J.; Ge, Z.; Lin, X.; Zhang, W.; Huang, H.; Zhao, J.; Saw, P.E.; et al. A high-fat diet promotes cancer progression by inducing gut microbiota–mediated leucine production and PMN-MDSC differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2306776121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Meng, F.; Wang, J.; Wei, J.; Zhang, K.; Qin, S.; Li, M.; Wang, F.; Wang, B.; Liu, T.; et al. Desulfovibrio vulgaris flagellin exacerbates colorectal cancer through activating LRRC19/TRAF6/TAK1 pathway. Gut Microbes 2024, 17, 2446376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsay, J.-C.J.; Wu, B.G.; Sulaiman, I.; Gershner, K.; Schluger, R.; Li, Y.; Yie, T.-A.; Meyn, P.; Olsen, E.; Perez, L.; et al. Lower Airway Dysbiosis Affects Lung Cancer Progression. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojcik, E.; Kulpa, J. Pro-gastrin-releasing peptide (ProGRP) as a biomarker in small-cell lung cancer diagnosis, monitoring and evaluation of treatment response. Lung Cancer Targets Ther. 2017, 8, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogtmann, E.; Hua, X.; Yu, G.; Purandare, V.; Hullings, A.G.; Shao, D.; Wan, Y.; Li, S.; Dagnall, C.L.; Jones, K.; et al. The Oral Microbiome and Lung Cancer Risk: An Analysis of 3 Prospective Cohort Studies. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2022, 114, 1501–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Li, J.; Zhou, X. Lung microbiome: New insights into the pathogenesis of respiratory diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucaciu, S.-R.; Domokos, B.; Puiu, R.; Ruta, V.; Motoc, S.N.; Rajnoveanu, R.; Todea, D.; Stoia, A.M.; Man, A.M. Lung Microbiome in Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsay, J.-C.J.; Wu, B.G.; Badri, M.H.; Clemente, J.C.; Shen, N.; Meyn, P.; Li, Y.; Yie, T.-A.; Lhakhang, T.; Olsen, E.; et al. Airway Microbiota Is Associated with Upregulation of the PI3K Pathway in Lung Cancer. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, 1188–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, K.; Cheung, A.H.K.; Wong, C.C.; Liu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, F.; Huang, P.; Yuan, K.; Coker, O.O.; Pan, Y.; et al. Streptococcus anginosus promotes gastric inflammation, atrophy, and tumorigenesis in mice. Cell 2024, 187, 882–896.e817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Fang, Z.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, J.; Gao, R.; Yao, S.; Ye, Y.; Wang, S.; Lin, C.; et al. Specific gut microbiome signature predicts the early-stage lung cancer. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 1030–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, S.; Wang, C.; Usyk, M.; Wu, F.; Freedman, N.D.; Huang, W.-Y.; McCullough, M.L.; Um, C.Y.; Shrubsole, M.J.; Cai, Q.; et al. Oral Microbiome and Subsequent Risk of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2024, 10, 1537–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.-H.; Du, Y.; Xue, W.-Q.; He, M.-J.; Zhou, T.; Zhao, Z.-Y.; Pei, L.; Chen, Y.-W.; Xie, J.-R.; Huang, C.-L.; et al. Oral microbiota signature predicts the prognosis of colorectal carcinoma. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.A.; Nishimata, H.; Ohara-Nemoto, Y.; Baba, T.T.; Hoshino, T.; Fujiwara, T.; Shimoyama, Y.; Kimura, S.; Nemoto, T.K. Identification of Dipeptidyl-Peptidase (DPP)5 and DPP7 in Porphyromonas endodontalis, Distinct from Those in Porphyromonas gingivalis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, F.; Yang, R.; Yu, X.; Zhou, X.; Tang, N. Characteristics of the oral and gastric microbiome in patients with early-stage intramucosal esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, A.K.; Panda, M.; Das, A.K.; Rahman, T.; Das, R.; Das, K.; Sarma, A.; Kataki, A.C.; Chattopadhyay, I. Dysbiosis of salivary microbiome and cytokines influence oral squamous cell carcinoma through inflammation. Arch. Microbiol. 2020, 203, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.-L.; Pang, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.-J. The Gastric Microbiome Is Perturbed in Advanced Gastric Adenocarcinoma Identified Through Shotgun Metagenomics. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, P.; Xiong, J.; Sha, H.; Dai, X.; Lu, J. Tumor bacterial markers diagnose the initiation and four stages of colorectal cancer. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1123544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liang, X.; Zhi, M.; Li, L.; Zhang, G.; Chen, C.; Wang, L.; Wang, P.; Zhong, N.; Feng, Q.; et al. Succession of the multi-site microbiome along pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma tumorigenesis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1487242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasin, M.; Rothstein, R. Repair of strand breaks by homologous recombination. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a012740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, T.W.H.; Peeters, W.J.M.; Dubois, L.J.; van Gisbergen, M.W.; Biemans, R.; Venhuizen, J.-H.; Span, P.N.; Bussink, J. Targeting glucose and glutamine metabolism combined with radiation therapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2018, 126, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunt, S.Y.; Vander Heiden, M.G. Aerobic Glycolysis: Meeting the Metabolic Requirements of Cell Proliferation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2011, 27, 441–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duszka, K. Versatile Triad Alliance: Bile Acid, Taurine and Microbiota. Cells 2022, 11, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Wu, X.; Zhou, X.; Sun, Z.; Shen, J.; Kong, M.; Chen, N.; Qiu, J.-G.; Jiang, B.-H.; Yuan, C.; et al. Association of cigarette smoking with oral bacterial microbiota and cardiometabolic health in Chinese adults. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Healthy Control (HC), (n = 38) | Lung Cancer (LC), (n = 24) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), Median (IQR) | 53 (7) | 61 (16) | 0.025 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.117 | ||

| Female | 17 (44.7) | 6 (25.0) | |

| Male | 21 (55.3) | 18 (75.0) | |

| Smoking, n (%) | 0.062 | ||

| Nonsmoker | 25 (65.8) | 10 (41.7) | |

| Current or former smoker | 13 (34.2) | 14 (58.3) | |

| Alcohol, n (%) | 0.704 | ||

| Absent | 24 (63.2) | 14 (58.3) | |

| Present | 14 (36.8) | 10 (41.7) | |

| BMI (kg/m2), (Mean ± SD) | 24.54 ± 3.54 | 24.00 ± 3.20 | 0.550 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, X.; Bi, N.; Liu, W.; Ma, L.; Liu, M.; Xu, T.; Shu, X.; Gao, L.; Wang, R.; Chen, Y.; et al. Identification of Oral Microbiome Biomarkers Associated with Lung Cancer Diagnosis and Radiotherapy Response Prediction. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121294

Shi X, Bi N, Liu W, Ma L, Liu M, Xu T, Shu X, Gao L, Wang R, Chen Y, et al. Identification of Oral Microbiome Biomarkers Associated with Lung Cancer Diagnosis and Radiotherapy Response Prediction. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121294

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Xiaoqian, Nan Bi, Wenyang Liu, Liying Ma, Mingyang Liu, Tongzhen Xu, Xingmei Shu, Linrui Gao, Ranjiaxi Wang, Yinan Chen, and et al. 2025. "Identification of Oral Microbiome Biomarkers Associated with Lung Cancer Diagnosis and Radiotherapy Response Prediction" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121294

APA StyleShi, X., Bi, N., Liu, W., Ma, L., Liu, M., Xu, T., Shu, X., Gao, L., Wang, R., Chen, Y., Li, L., Zhu, Y., & Li, D. (2025). Identification of Oral Microbiome Biomarkers Associated with Lung Cancer Diagnosis and Radiotherapy Response Prediction. Pathogens, 14(12), 1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121294