Metagenomic Profile of Bacterial Communities of Hyalomma scupense and Hyalomma asiaticum Ticks in Kazakhstan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tick Sampling

2.2. Molecular-Genetic Identification of Ticks

2.3. DNA Extraction

2.4. Library Preparation

2.5. Sequencing

2.6. Taxonomic Classification

2.7. Statistical Data Analysis

3. Results

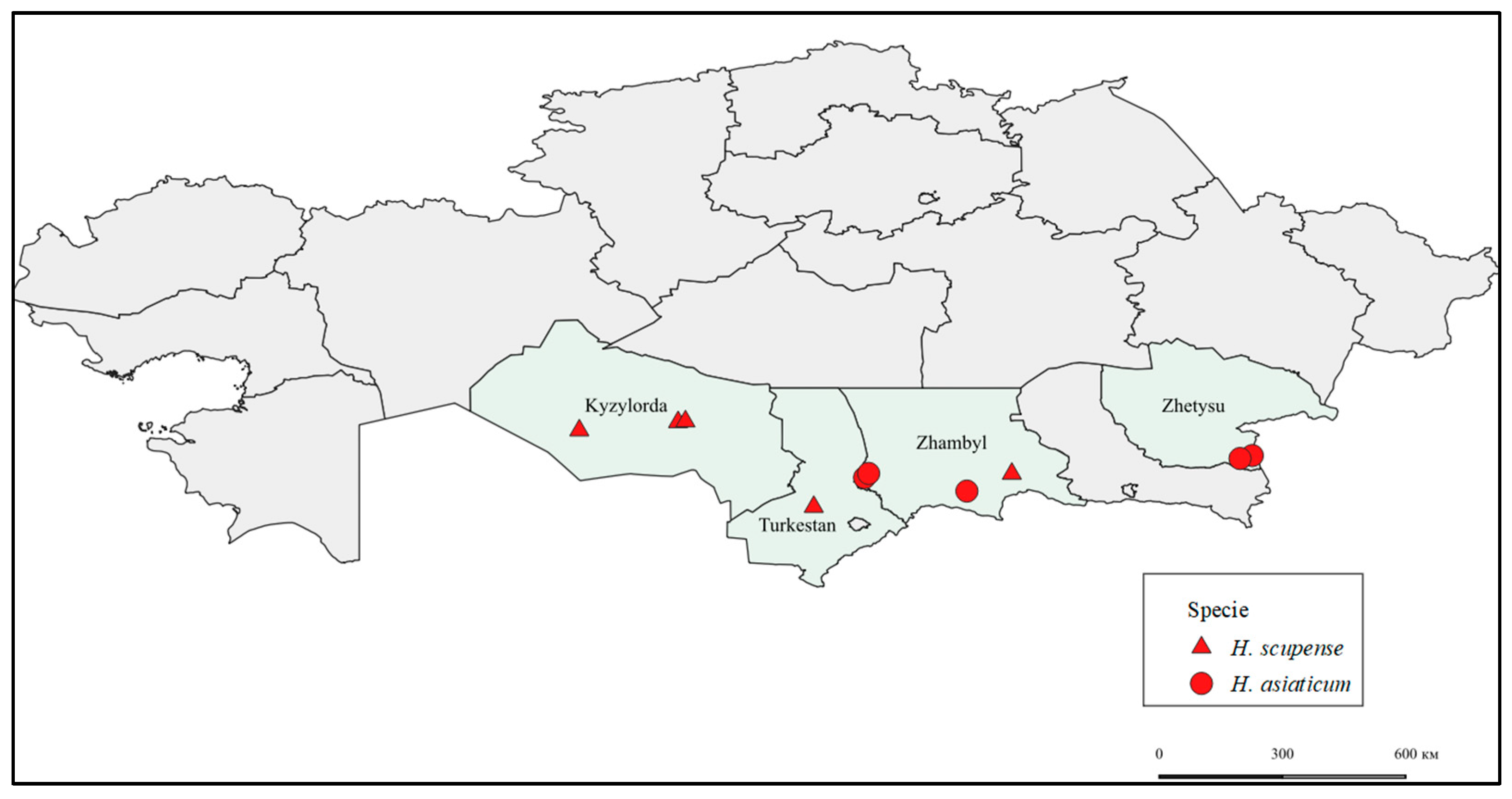

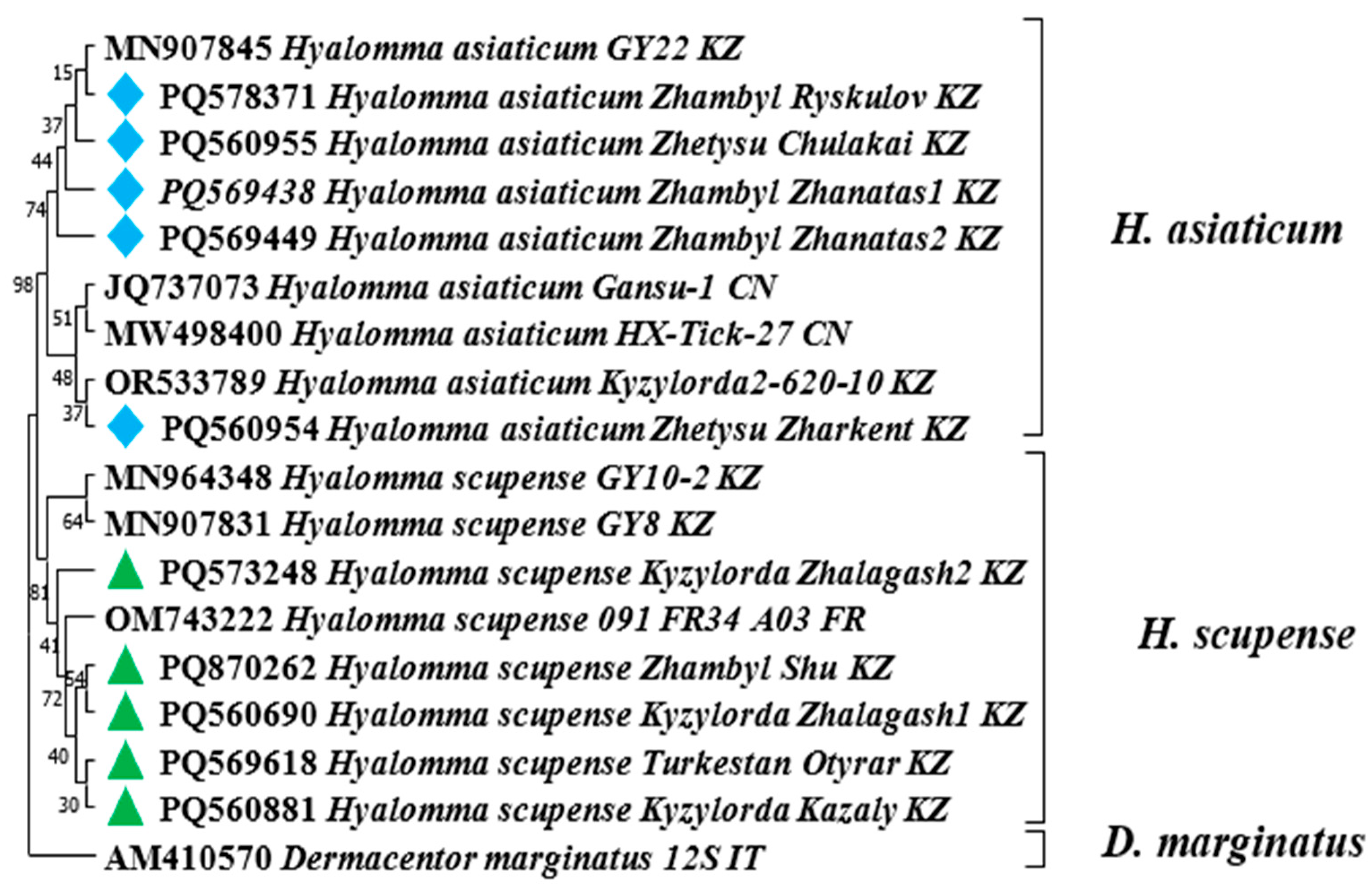

3.1. Tick Collection and Identification

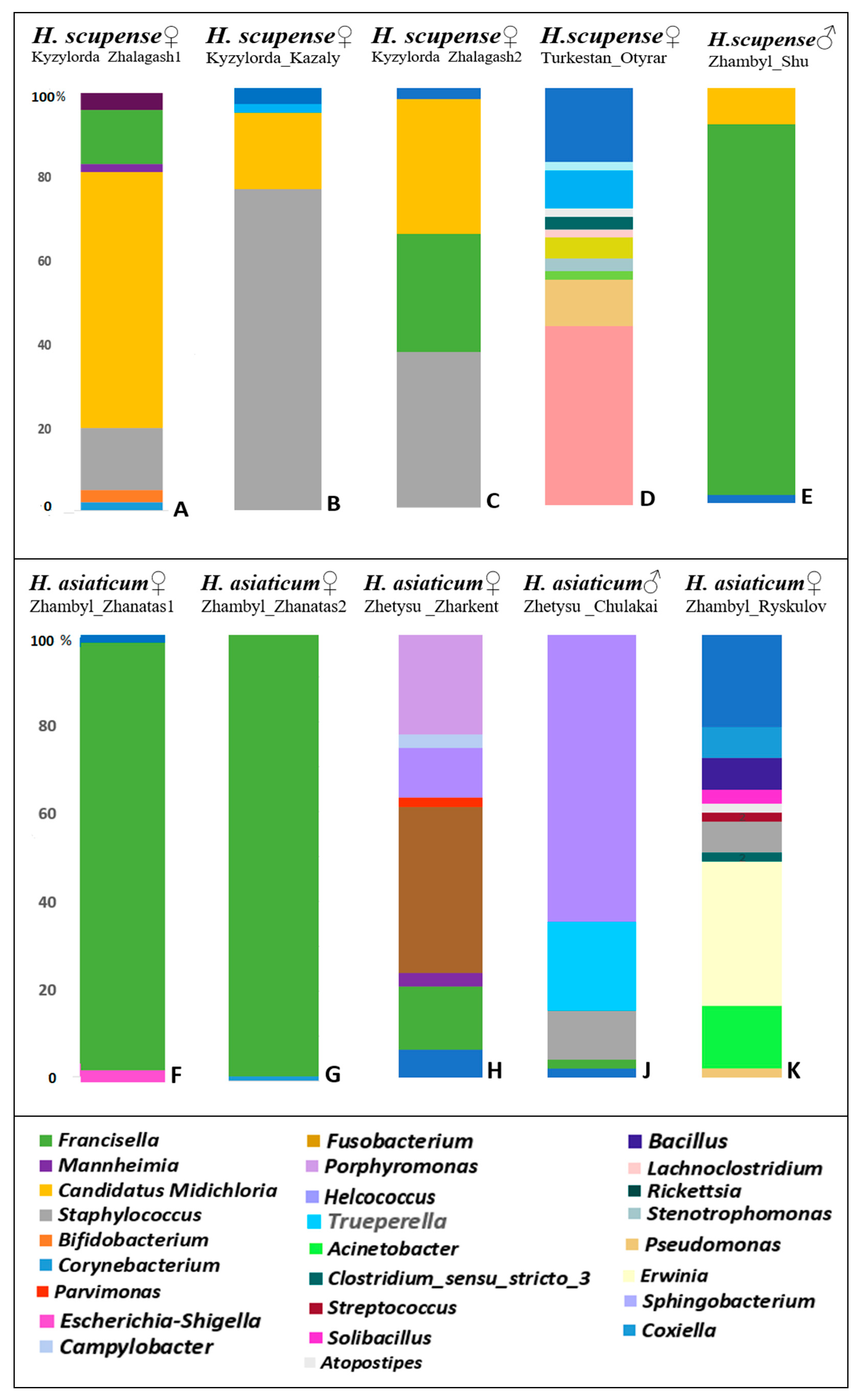

3.2. Assessment of the Bacterial Diversity Profile Based on 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

3.3. Bacterial Microbiome Diversity in H. scupense and H. asiaticum

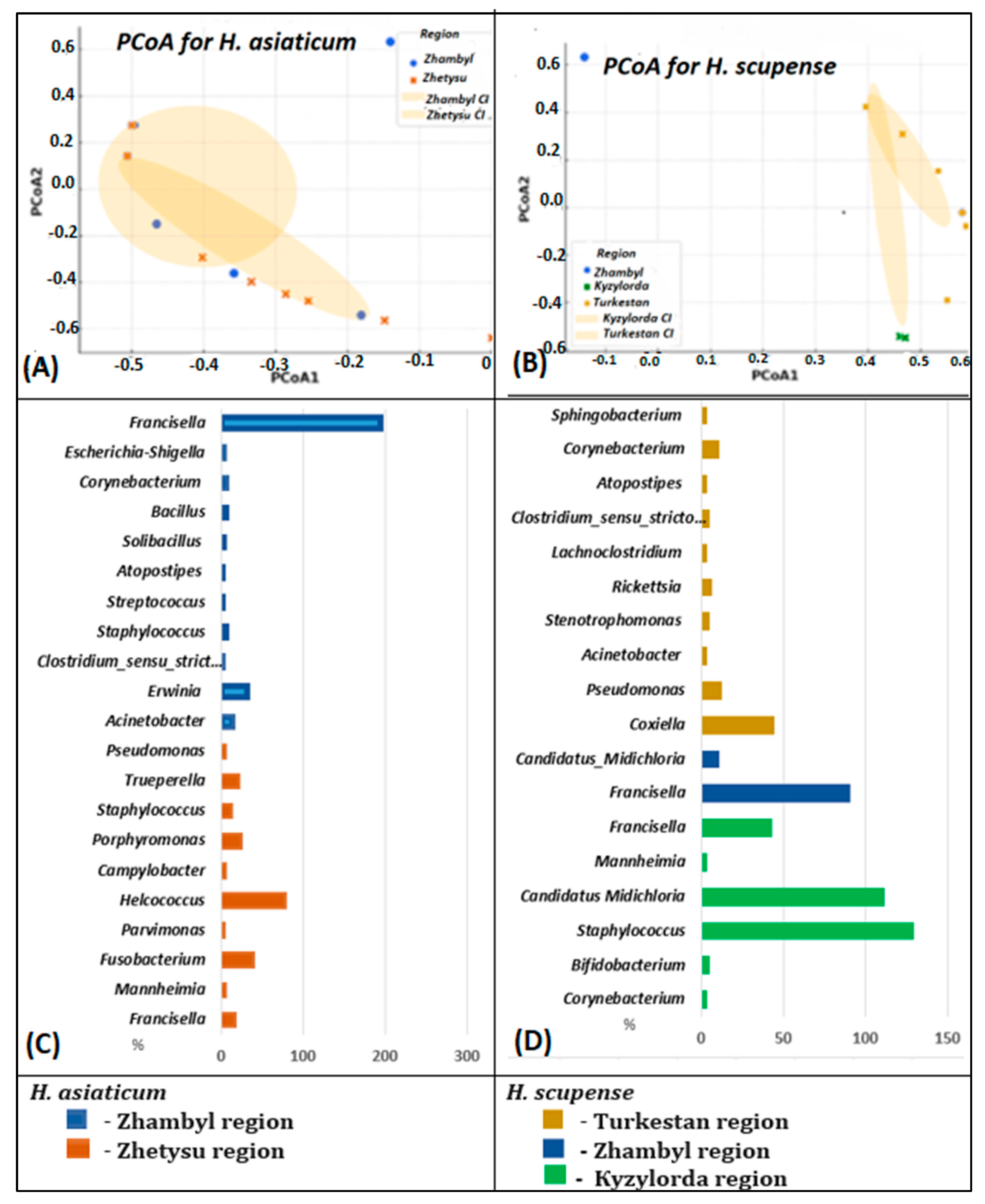

3.4. Microbial Variations Depending on Geographic Origin

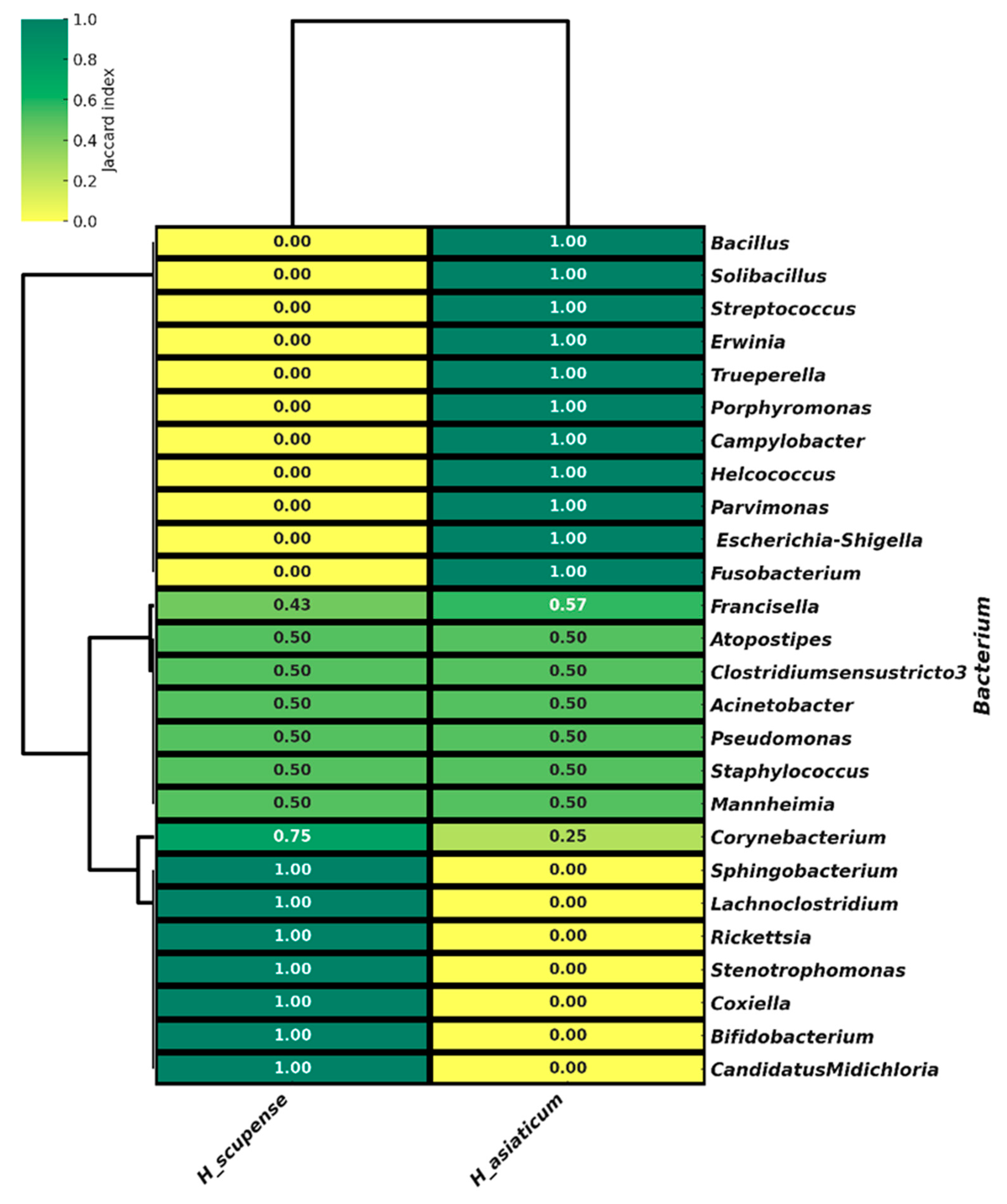

3.5. Beta Diversity of the Bacterial Community in the Microbiome of H. scupense and H. asiaticum Ticks

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boulanger, N.; Boyer, P.; Talagrand-Reboul, E.; Hansmann, Y. Ticks and tick-borne diseases. Med. Mal. Infect. 2019, 49, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parola, P.; Raoult, D. Ticks and tickborne bacterial diseases in humans: An emerging infectious threat. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 32, 897–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greay, T.L.; Gofton, A.W.; Paparini, A.; Ryan, U.M.; Oskam, C.L.; Irwin, P.J. Recent insights into the tick microbiome gained through next-generation sequencing. Parasit. Vectors 2018, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu-Chuang, A.; Hodzic, A.; Mateos-Hernandez, L.; Estrada-Pena, A.; Obregon, D.; Cabezas-Cruz, A. Current debates and advances in tick microbiome research. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector Borne Dis. 2021, 1, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmone, A.A.; Robbins, R.G.; Apanaskevich, D.A.; Petney, T.N.; Estrada-Peña, A.; Horak, I.G.; Shao, R.; Barker, S. The Argasidae, Ixodidae and Nuttalliellidae (Acari: Ixodida) of the world: A list of valid species names. Zootaxa 2010, 2528, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonenshine, D.E.; Lane, R.; Nicholson, W. Ticks (Ixodida). In Medical and Veterinary Entomology; Mullen, G., Durden, L., Eds.; Academia: Orlando, FL, USA, 2002; pp. 517–558. [Google Scholar]

- Sayakova, Z.Z.; Abdybekova, A.M.; Zhaksylykova, A.A.; Kenessary, S.A.; Berdiakhmetkyzy, S.; Kulemin, M.V. Distribution of Hyalomma asiaticum Schulze et Schlottke, 1929 (Acari, Ixodidae) ticks in southern Kazakhstan. Sci. Educ. 2024, 3, 76. [Google Scholar]

- Kulemin, M.V.; Rapoport, L.P.; Vasilenko, A.V.; Kobeshova, Z.h.B.; Shokputov, T.M.; Saylaubekuly, R.; Atovullaeva, L.M. Ixodid ticks of farm animals in Southern Kazakhstan: Fauna structure, abundance, epizootological significance. Parazitologiya 2020, 54, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Perfilyeva, Y.V.; Shapiyeva, Z.Z.h.; Ostapchuk, Y.O.; Berdygulova, Z.A.; Bissenbay, A.O.; Kulemin, M.V.; Ismagulova, G.A.; Skiba, Y.A.; Sayakova, Z.Z.; Mamadaliyev, S.M. Tick-borne pathogens and their vectors in Kazakhstan. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2020, 11, 101498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultankulova, K.T.; Shynybekova, G.O.; Kozhabergenov, N.S.; Mukhami, N.N.; Chervyakova, O.V.; Burashev, Y.D.; Zakarya, K.D.; Nakhanov, A.K.; Barakbayev, K.B.; Orynbayev, M.B. The prevalence and genetic variants of the CCHF virus circulating among ticks in the southern regions of Kazakhstan. Pathogens 2022, 11, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultankulova, K.T.; Shynybekova, G.O.; Issabek, A.U.; Mukhami, N.N.; Melisbek, A.M.; Chervyakova, O.V.; Kozhabergenov, N.S.; Barmak, S.M.; Bopi, A.K.; Omarova, Z.D. The prevalence of pathogens among ticks collected from livestock in Kazakhstan. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orynbayev, M.B.; Rystaeva, R.A.; Omarova, Z.D.; Kerimbaev, A.A.; Sarsenbaeva, G.Z.H.; Kopeev, S.K.; Nakhanov, A.K.; Strochkov, V.M.; Sultankulova, K. Isolation of Coxiella burnetii from ticks in Kazakhstan. Biosafety Biotechnol. 2020, 1, 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Sultankulova, K.T.; Kozhabergenov, N.S.; Shynybekova, G.O.; Chervyakova, O.V.; Usserbayev, B.S.; Alibekova, D.A.; Zhunushov, A.T.; Orynbayev, M.B. Metagenomic Detection of RNA Viruses of Hyalomma asiaticum Ticks in the Southern Regions of Kazakhstan. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serretiello, E.; Astorri, R.; Chianese, A.; Stelitano, D.; Zannella, C.; Folliero, V.; Santella, B.; Galdiero, M.; Franci, G.; Galdiero, M. The Emerging Tick-Borne Crimean-Congo Haemorrhagic Fever Virus: A Narrative Review. Travel. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 37, 101871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyedem, H.; Lekired, A.; Mhadhbi, M.; Dhibi, M.; Romdhane, R.; Chaari, S.; Rekik, M.; Ouzari, H.I.; Hajji, T.; Darghouth, M.A. First Insights into the Microbiome of Tunisian Hyalomma Ticks Gained through Next-Generation Sequencing with a Special Focus on H. scupense. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, J.A.; Blaser, M.J.; Caporaso, J.G.; Jansson, J.K.; Lynch, S.V.; Knight, R. Current understanding of the human microbiome. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kratou, M.; Maitre, A.; Abuin-Denis, L.; Selmi, R.; Belkahia, H.; Alanazi, A.D.; Gattan, H.; Al-Ahmadi, B.M.; Shater, A.F.; Mateos-Hernández, L.; et al. Microbial community variations in adult Hyalomma dromedarii ticks from Saudi Arabia and Tunisia. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1543560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Díaz, H.; Quiroz-Castañeda, R.E.; Cobaxin-Cárdenas, M.; Salinas-Estrella, E.; Amaro-Estrada, I. Advances in the study of the tick cattle microbiota and the influence on vectorial capacity. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 710352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Ruiz, P. The tick microbiome: The “other bacterial players” in tick biocontrol. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masri, M.T.A.; Al-Deeb, M.A. A systematic review of the microbiome of Hyalomma Koch, 1844 ticks using next-generation sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene. Vet. World 2025, 18, 1090–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimoldi, S.G.; Tamoni, A.; Rizzo, A.; Longobardi, C.; Pagani, C.; Salari, F.; Matinato, C.; Vismara, C.; Gagliardi, G.; Cutrera, M. Evaluation of 16S-Based Metagenomic NGS as Diagnostic Tool in Different Types of Culture-Negative Infections. Pathogens 2024, 13, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkathiri, B.; Lee, S.; Ahn, K.; Cho, Y.S.; Youn, S.Y.; Seo, K.; Umemiya-Shirafuji, R.; Xuan, X.; Kwak, D.; Shin, S.; et al. 16S rRNA Metabarcoding for the Identification of Tick-Borne Bacteria in Ticks in the Republic of Korea. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.Q.; Wang, S.Y.; Yang, M.H.; Ulzhan, N.; Omarova, K.; Liu, Z.Q.; Kazkhan, O.; Wang, Y.Z. First Detection of Tacheng Tick Virus 2 in Hard Ticks from Southeastern Kazakhstan. Kafkas Univ. Vet. Fak. Derg. 2022, 28, 139–142. [Google Scholar]

- Bukharbaev, E.B.; Bayakhmetova, M.M.; Abuova, G.N.; Sailaubekuly, R.; Utepov, P.D.; Eskerova, S.U.; Kulemin, M.V.; Berdiyarova, N.A.; Beisembayeva, Z.I. Entomological and Epidemiological Aspects of Emerging Tick-Borne Infections in Southern Kazakhstan. Pharm. J. Kazakhstan 2024, 2, 173–182. [Google Scholar]

- Apanaskevich, D.A.; Horak, I.G. The genus Hyalomma. XI. Redescription of all parasitic stages of H. (Euhyalomma) asiaticum and notes on its biology. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2010, 52, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Y. Assessment of four DNA fragments (COI, 16S rDNA, ITS2, 12S rDNA) for species identification of the Ixodida (Acari: Ixodida). Parasit. Vectors. 2014, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitimia, L.; Lin, R.Q.; Cosoroaba, I.; Wu, X.Y.; Song, H.Q.; Yuan, Z.G.; Zhu, X.Q. Genetic characterization of ticks from southwestern Romania by sequences of mitochondrial cox1 and nad5 genes. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2010, 52, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thukral, A.K.; Bhardwaj, R.; Kumar, V.; Sharma, A. New indices regarding the dominance and diversity of communities, derived from sample variance and standard deviation. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, E.H. Measurement of diversity. Nature 1949, 168, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalef, D.R. Information theory in ecology. Gen. Syst. 1958, 3, 36–71. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs, C.J. Ecological Methodology; Benjamin Cummings: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pesenko, Y.A. Principles and Methods of Quantitative Analysis in Faunistic Studies; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Peña, A.; Farkas, R.; Jaenson, T.G.; Koenen, F.; Madder, M.; Pascucci, I.; Salman, M.; Tarrés-Call, J.; Jongejan, F. Association of Environmental Traits with the Geographic Ranges of Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) of Medical and Veterinary Importance in the Western Palearctic. A Digital Data Set. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2013, 59, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves Rodrigues, M.; Lesiczka, P.; Fontes, M.C.; Cardoso, L.; Coelho, A.C. The Expanding Threat of Crimean-Congo Haemorrhagic Fever Virus: Role of Migratory Birds and Climate Change as Drivers of Hyalomma spp. Dispersal in Europe. Birds 2025, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capek, M.; Literak, I.; Kocianova, E.; Sychra, O.; Najer, T.; Trnka, A.; Kverek, P. Ticks of the Hyalomma marginatum Complex Transported by Migratory Birds into Central Europe. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2014, 5, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, J.M.; Mohammed, I.A.; Karim, A.J. The epidemiology of tick in transmission of Enterobacteriaceae bacteria in buffaloes in marshes of the south of Iraq. Vet. World 2018, 11, 1677–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, A.; Bursali, A.; Snow, D.E.; Dowd, S.E.; Tekin, S. Assessment of bacterial diversity in Hyalomma. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2017, 73, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scoles, G.A. Phylogenetic analysis of the Francisella-like endosymbionts of Dermacentor ticks. J. Med. Entomol. 2004, 41, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, S.; Budachetri, K.; Mukherjee, N.; Williams, J.; Kausar, A.; Hassan, M.J.; Adamson, S.; Dowd, S.E.; Apanskevich, D.; Arijo, A.; et al. A study of ticks and tick-borne livestock pathogens in Pakistan. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafar, A.; Cabezas-Cruz, A.; Galon, C.; Obregon, D.; Gasser, R.B.; Moutailler, S.; Jabbar, A. Bovine ticks harbour a diverse array of microorganisms in Pakistan. Parasit. Vectors 2020, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Yang, X.; Zhang, L. The differences in microbial communities and tick-borne pathogens between Dermacentor marginatus and Hyalomma asiaticum collected from Northwestern China. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.D.; Falsen, E.; Brownlee, K.; Lawson, P.A. Helcococcus sueciensis sp. nov., isolated from a human wound. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 1557–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.D.; Falsen, E.; Foster, G.; Monasterio, L.R.; Dominguez, L.; Fernandez-Garayzabal, J.F. Helcococcus ovis sp. nov., a Gram-positive organism from sheep. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1999, 49, 1429–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Zhou, X.J.; Chen, K.L.; Masoudi, A.; Liu, J.Z.; Zhang, Y.K. Bacterial microbiota analysis demonstrates that ticks acquire bacteria from habitat and host blood meal. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2021, 87, 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.H.; Cao, J.; Zhou, Y.Z.; Zhang, H.S.; Gong, H.Y.; Zhou, J.L. The midgut bacterial flora of laboratory-reared ticks (Haemaphysalis longicornis, Hyalomma asiaticum, Rhipicephalus haemaphysaloides). J. Integr. Agric. 2014, 13, 1766–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beninati, T.; Lo, N.; Sacchi, L.; Genchi, C.; Noda, H.; Bandi, C. A novel alpha-Proteobacterium resides in mitochondria of ovarian cells of Ixodes ricinus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 2596–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivieri, E.; Epis, S.; Castelli, M. Tissue tropism and metabolic pathways of Midichloria mitochondrii in Ixodes ricinus. Ticks and Tick-Borne Dis. 2019, 10, 1070–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, T.; Hu, E.; Gan, L.; Yang, D.; Wu, J.; Gao, S.; Tuo, X.; Bayin, C.G.; Hu, Z.; Guo, Q. Candidatus Midichloria mitochondrii can be vertically transmitted in Hyalomma anatolicum. Exp. Parasitol. 2024, 265, 108828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swei, A.; Kwan, J.Y. Tick microbiome and pathogen acquisition altered by host blood meal. ISME J. 2017, 11, 813–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollet, T.; Sprong, H.; Lejal, E.; Krawczyk, A.I.; Moutailler, S.; Cosson, J.F.; Vayssier-Taussat, M.; Estrada-Peña, A. Scale affects identification and distribution of microbial communities in ticks. Parasit. Vectors 2020, 13, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aivelo, T.; Norberg, A.; Tschirren, B. Bacterial microbiota composition of Ixodes ricinus: Environmental variation, tick characteristics and microbial interactions. PeerJ 2019, 7, e8217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trout Fryxell, R.T.; DeBruyn, J.M. The microbiome of Ehrlichia-infected and uninfected lone star ticks (Amblyomma americanum). PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0168994. [Google Scholar]

- van Treuren, W.; Ponnusamy, L.; Brinkerhoff, R.J.; Gonzalez, A.; Parobek, C.M.; Juliano, J.J.; Andreadis, T.G.; Falco, R.C.; Ziegler, L.B.; Hathaway, N.; et al. Variation in the microbiota of Ixodes ticks with geography, species, and sex. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 6200–6209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigwada, A.D.; Mapholi, N.O.; Ogola, H.J.O.; Mbizeni, S.; Masebe, T.M. Pathogenic and endosymbiotic bacteria and associated antibiotic resistance biomarkers in Amblyomma and Hyalomma ticks infesting Nguni cattle. Pathogens 2022, 11, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angesom, B.G.E. Review on the Impact of Ticks on Livestock Health and Productivity. J. Biol. Agric. Healthc. 2016, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

—Kyzylorda_Zhalagash1_H. scupense, Kyzylorda_Zhalagash2_H. scupense, Kyzylorda_Kazaly_H. scupense, Zhambyl_Shu_H. scupense, Turkestan_Otyrar_H. scupense.

—Kyzylorda_Zhalagash1_H. scupense, Kyzylorda_Zhalagash2_H. scupense, Kyzylorda_Kazaly_H. scupense, Zhambyl_Shu_H. scupense, Turkestan_Otyrar_H. scupense.  —Zhambyl_Zhanatas1_H. asiaticum, Zhambyl_Zhanatas2_H. asiaticum, Zhambyl_Ryskulov_H. asiaticum, Zhetysu_Zharkent_H. asiaticum, Zhetysu_Chulakai_H. asiaticum.

—Zhambyl_Zhanatas1_H. asiaticum, Zhambyl_Zhanatas2_H. asiaticum, Zhambyl_Ryskulov_H. asiaticum, Zhetysu_Zharkent_H. asiaticum, Zhetysu_Chulakai_H. asiaticum.

—Kyzylorda_Zhalagash1_H. scupense, Kyzylorda_Zhalagash2_H. scupense, Kyzylorda_Kazaly_H. scupense, Zhambyl_Shu_H. scupense, Turkestan_Otyrar_H. scupense.

—Kyzylorda_Zhalagash1_H. scupense, Kyzylorda_Zhalagash2_H. scupense, Kyzylorda_Kazaly_H. scupense, Zhambyl_Shu_H. scupense, Turkestan_Otyrar_H. scupense.  —Zhambyl_Zhanatas1_H. asiaticum, Zhambyl_Zhanatas2_H. asiaticum, Zhambyl_Ryskulov_H. asiaticum, Zhetysu_Zharkent_H. asiaticum, Zhetysu_Chulakai_H. asiaticum.

—Zhambyl_Zhanatas1_H. asiaticum, Zhambyl_Zhanatas2_H. asiaticum, Zhambyl_Ryskulov_H. asiaticum, Zhetysu_Zharkent_H. asiaticum, Zhetysu_Chulakai_H. asiaticum.

—Hyalomma scupense identified in this study based on the COX1 gene.

—Hyalomma scupense identified in this study based on the COX1 gene.  —Hyalomma asiaticum identified in this study based on the COX1 gene.

—Hyalomma asiaticum identified in this study based on the COX1 gene.

—Hyalomma scupense identified in this study based on the COX1 gene.

—Hyalomma scupense identified in this study based on the COX1 gene.  —Hyalomma asiaticum identified in this study based on the COX1 gene.

—Hyalomma asiaticum identified in this study based on the COX1 gene.

| Sample Collection Site | Coordinates | No. of Ticks | Tick Species | Sex | Host | Genbank Accession No | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kyzylorda_Zhalagash1 | 45°04′55″ 64°40′51″ | 10 | H. scupense | ♀ | Cattle | PQ560690 |

| 2 | Zhambyl_Zhanatas1 | 43°34′00″ 69°45′00″ | 10 | H. asiaticum | ♀ | Cattle | PQ569438 |

| 3 | Kyzylorda_Kazaly | 44°51′00″ 61°59′24″ | 10 | H. scupense | ♀ | Cattle | PQ560881 |

| 4 | Kyzylorda_Zhalagash2 | 45°04′55″ 64°40′51″ | 10 | H. scupense | ♀ | Cattle | PQ573248 |

| 5 | Zhambyl_Zhanatas2 | 43°34′00″ 69°45′00″ | 10 | H. asiaticum | ♀ | Cattle | PQ569449 |

| 6 | Zhambyl_Shu | 43°40′32″ 73°45′40″ | 8 | H. scupense | ♂ | Cattle | PQ571834 |

| 7 | Zhetysu_Zharkent | 44°10′00″ 80°00′00″ | 10 | H. asiaticum | ♀ | Cattle | PQ560954 |

| 8 | Zhetysu_Chulakai | 44°05′15″ 79°58′00″ | 6 | H. asiaticum | ♂ | Cattle | PQ560955 |

| 9 | Zhambyl_Ryskulov | 43°12′00″ 72°32′00″ | 10 | H. asiaticum | ♀ | Cattle | PQ578371 |

| 10 | Turkestan_Otyrar | 42°46′36″ 68°22′09″ | 10 | H. scupense | ♀ | Cattle | PQ569618 |

| Index Name | Formula | Diversity Level |

|---|---|---|

| Shannon–Wiener diversity index | Alpha diversity | |

| Margalef richness index | Alpha diversity | |

| Simpson’s dominance index | ∑ | Alpha diversity |

| Bray–Curtis dissimilarity index | Beta diversity | |

| Jaccard similarity index | Beta diversity |

| Tick Sample | HSKZ1, % | HSKK, % | HSKZ2, % | HSTO, % | HSZS, % | HAZZ1, % | HAZZ2, % | HAZZ, % | HAZC, % | HAZR, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus of Bacteria | |||||||||||

| Corynebacterium | 2 | 2 | - | 9 | - | - | - | - | - | 7 | |

| Bifidobacterium | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Staphylococcus | 15 | 76 | 37 | - | - | - | - | - | 11 | 6 | |

| Candidatus Midichloria | 61 | 17 | 32 | - | 9 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Mannheimia | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | - | - | ||

| Francisella | 13 | - | 28 | - | 89 | 95 | 99 | 14 | 2 | - | |

| Coxiella | - | - | - | 43 | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Pseudomonas | - | - | - | 11 | - | - | - | 37 | - | - | |

| Acinetobacter | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | 14 | |

| Stenotrophomonas | - | - | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | |

| Rickettsia | - | - | - | 5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Lachnoclostridium | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Clostridium sensu stricto 3 | - | - | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | |

| Atopostipes | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | |

| Sphingobacterium | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Escherichia-Shigella | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | |

| Fusobacterium | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Parvimonas | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | |

| Helcococcus | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 11 | 65 | - | |

| Campylobacter | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | - | - | |

| Porphyromonas | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 23 | - | - | |

| Trueperella | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 20 | - | |

| Erwinia | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 32 | |

| Streptococcus | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Bacillus | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 7 | |

| Solibacillus | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 7 | ||

| Other | 4 | 5 | 3 | 18 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 21 | |

| |||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sultankulova, K.T.; Kozhabergenov, N.S.; Shynybekova, G.O.; Almezhanova, M.D.; Zhaksylyk, S.B.; Abayeva, M.R.; Chervyakova, O.V.; Argimbayeva, T.O.; Orynbayev, M.B. Metagenomic Profile of Bacterial Communities of Hyalomma scupense and Hyalomma asiaticum Ticks in Kazakhstan. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14101008

Sultankulova KT, Kozhabergenov NS, Shynybekova GO, Almezhanova MD, Zhaksylyk SB, Abayeva MR, Chervyakova OV, Argimbayeva TO, Orynbayev MB. Metagenomic Profile of Bacterial Communities of Hyalomma scupense and Hyalomma asiaticum Ticks in Kazakhstan. Pathogens. 2025; 14(10):1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14101008

Chicago/Turabian StyleSultankulova, Kulyaisan T., Nurlan S. Kozhabergenov, Gaukhar O. Shynybekova, Meirim D. Almezhanova, Samat B. Zhaksylyk, Madina R. Abayeva, Olga V. Chervyakova, Takhmina O. Argimbayeva, and Mukhit B. Orynbayev. 2025. "Metagenomic Profile of Bacterial Communities of Hyalomma scupense and Hyalomma asiaticum Ticks in Kazakhstan" Pathogens 14, no. 10: 1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14101008

APA StyleSultankulova, K. T., Kozhabergenov, N. S., Shynybekova, G. O., Almezhanova, M. D., Zhaksylyk, S. B., Abayeva, M. R., Chervyakova, O. V., Argimbayeva, T. O., & Orynbayev, M. B. (2025). Metagenomic Profile of Bacterial Communities of Hyalomma scupense and Hyalomma asiaticum Ticks in Kazakhstan. Pathogens, 14(10), 1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14101008