Oral Microbiota and Carcinogenesis: Exploring the Systemic Impact of Oral Pathogens

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Via the lymphatic system—from the oral mucosa, pathogens may access distant sites by utilizing the lymphatic channels [8].

- Through the digestive tract—oral–gut translocation can occur via continuous swallowing of saliva, as approximately 1–2 L of saliva containing up to 108 oral bacteria per milliliter are swallowed daily, potentially enabling microbial migration to the gastrointestinal tract [9].

- Through direct contact—poor oral hygiene combined with oral–genital contact can allow pathogens to colonize parts of the urogenital tract [10].

2. Organ and System-Specific Influences

2.1. Oro-Gastrointestinal Cancers

2.1.1. Oral Cancer

2.1.2. Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma

2.1.3. Gastric Cancer

| Study Sample | Sample Type | Oral Bacteria and Main Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| GC, n = 57 Controls, n = 80 | Tongue swab | The relative increase in Firmicutes and the reduced abundance of Bacteroidetes were associated with increased risk of GC; greater abundance of Alloprevotella spp., Veillonella spp., and Streptococcus spp. trended with higher risk of GC | [64] |

| GC, n = 12 Controls (functional dyspepsia), n = 20 | Gastric biopsy | Several bacterial taxa were enriched in GC, such as Veillonella spp., Fusobacterium spp., Leptotrichia spp., and Campylobacter spp. | [63] |

| GC, n = 103 Controls (chronic gastritis), n = 212 | Gastric biopsy | Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Fusobacterium spp., Actinobacteria, and Nitrospirae were enriched in GC | [65] |

| GC, n = 162 Controls (non-cancerous tissue), n = 62 | Gastric biopsy | The bacterial taxa enriched in the cancer samples were Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroides spp., Actinobacteria, and Fusobacterium spp. | [66] |

| GC, n = 6 Gastritis, n = 5 | Gastric wash sample | Neisseria spp., Alloprevotella spp., Aggregatibacter spp., and Streptococcus spp. were the most representative taxa abundant in GC | [62] |

| GC, n = 116 Healthy control, n = 88 | Feces | Veillonella spp. and Streptococcus spp. were enriched in GC and showed good performance in distinguishing GC patients from healthy controls | [59] |

| GC, n = 134 Healthy control, n = 58 | Feces | S. mitis and S. salivarius in feces were associated with a higher risk for GC; they may be associated with GC through influencing the amino acid metabolism | [60] |

| GC, n = 38 Healthy control, n = 35 | Feces | Enterobacteria, Streptococcus spp., and Escherichia spp. were increased in the GC | [61] |

| GC, n = 22 Healthy control, n = 30 | Feces | Prevotella spp. and Streptococcus spp. were more abundant in patients with GC | [62] |

2.1.4. Colorectal Cancer

| Study Sample | Sample Type | Oral Bacteria and Main Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 CRC and 30 healthy controls |

Unstimulated saliva, cancer tissues/biopsies, and stools | α and β diversity of the salivary and mucosal microbiome were higher for CRC | [78] |

| 14 CRC patients | Biopsy and saliva samples | F. nucleatum group was isolated from 57.1% of CRC biopsies; an identical strain of bacteria from the F. nucleatum group was found in CRC and saliva in 40% of patients | [79] |

| 101 CRC patients | CRC tissue samples and healthy tissue 10 cm beyond cancer margins | The abundance of F. nucleatum group bacteria in CRC tissues was significantly higher than that in normal controls | [80] |

| 19 CRC patients | CRC tissue samples and non-neoplastic mucosa from the proximal resection margin | The abundance of Fusobacterium and Campylobacter spp. was significantly higher in the tumor | [81] |

| 44 pieces of tissue from the tumors of 11 patients with CRC | CRC tissue | Fusobacterium and Bacteroides as the most dominant genera in the CRC | [82] |

| 807 tumor tissues from patients with CRC | CRC tissue | 17 bacterial species, including 4 Fusobacterium spp., classified as orally derived, were enriched in inflamed tumors | [83] |

| CRC (99 subjects), colorectal polyps (32), or controls (103) | Oral swabs, colonic mucosae, and stool | Streptococcus spp. and Prevotella spp. were differentially abundant in CRC compared with controls | [84] |

| 59 patients undergoing surgery for CRC, 21 individuals with polyps, and 56 healthy controls | Fecal and mucosal samples | Increased abundance of Bacteroides, Roseburia, Ruminococcus, and Oscillibacter, among others, and genera previously reported as oral pathogens (such as Porphyromonas, Peptostreptococcus, Parvimonas, and Fusobacterium, among others) | [85] |

| 252 CRC subjects | Fecal samples | Elevated relative abundance of members of F. nucleatum group, Peptostreptococcus stomatis, Gemella morbillorum, and Parvimonas micra | [86] |

2.2. Other Cancer Types

2.2.1. Lung Cancer

2.2.2. Breast Cancer

2.2.3. Pancreatic Cancer

2.2.4. Urogenital Cancers

2.2.5. Liver Cancer

3. Pathogenic Mechanisms

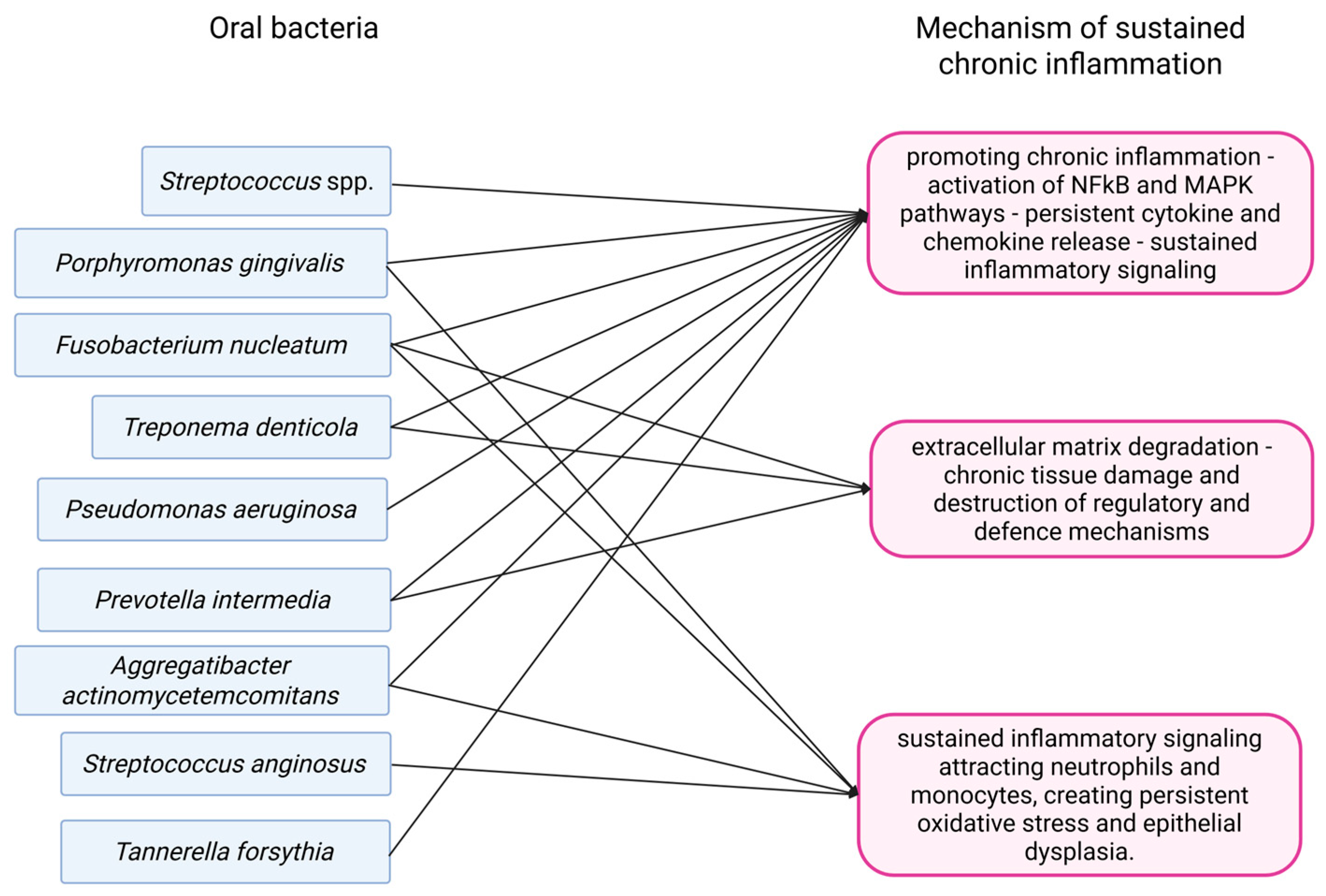

3.1. Chronic Inflammation

3.1.1. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma

3.1.2. Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma

3.1.3. Lung Cancer

3.1.4. Colorectal Cancer

3.1.5. Pancreatic Cancer

3.1.6. Gastric Cancer

3.1.7. Urogenital Cancers

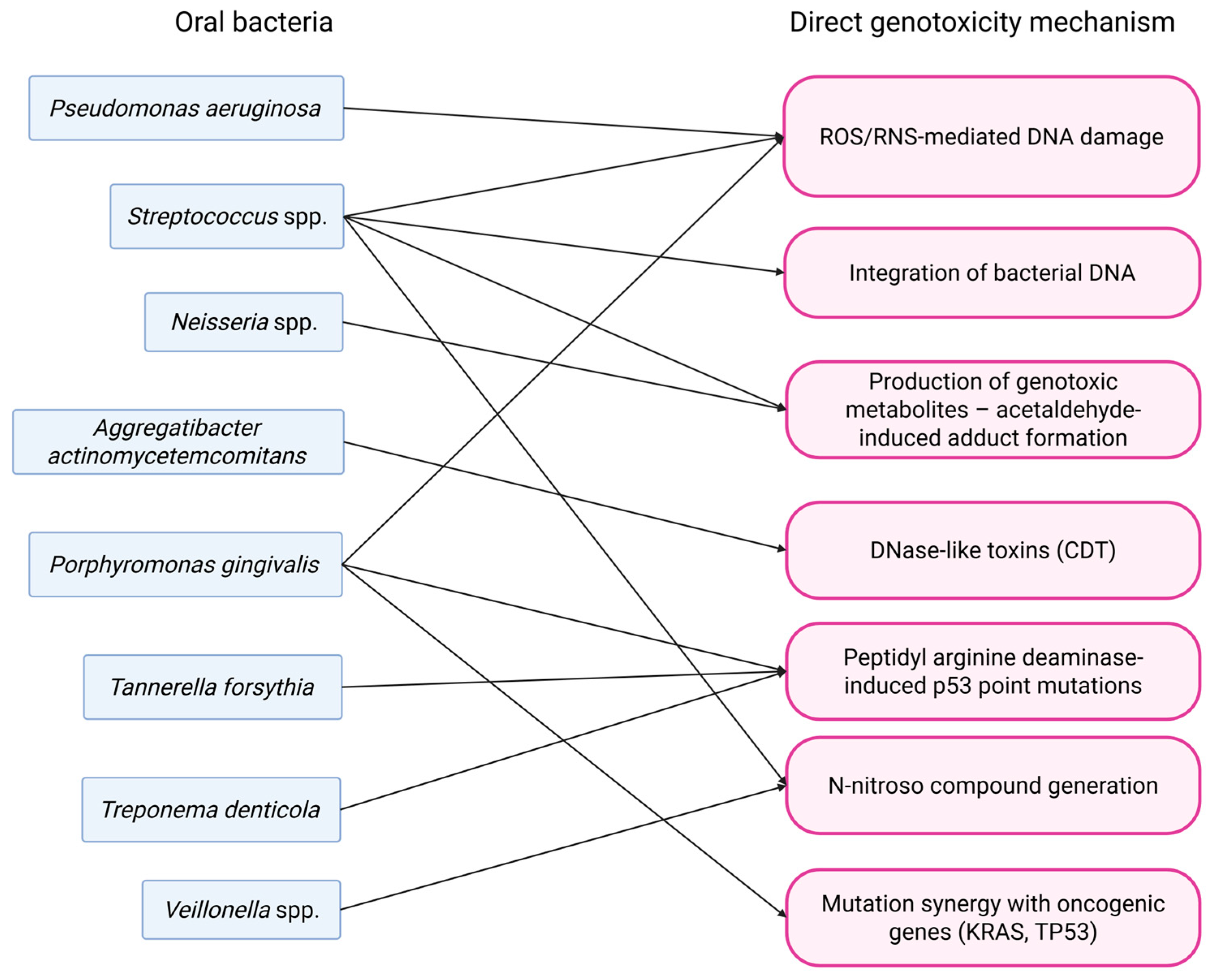

3.2. Direct Genotoxicity

3.2.1. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma

3.2.2. Lung Cancer

3.2.3. Gastric Cancer

3.2.4. Pancreatic Cancer

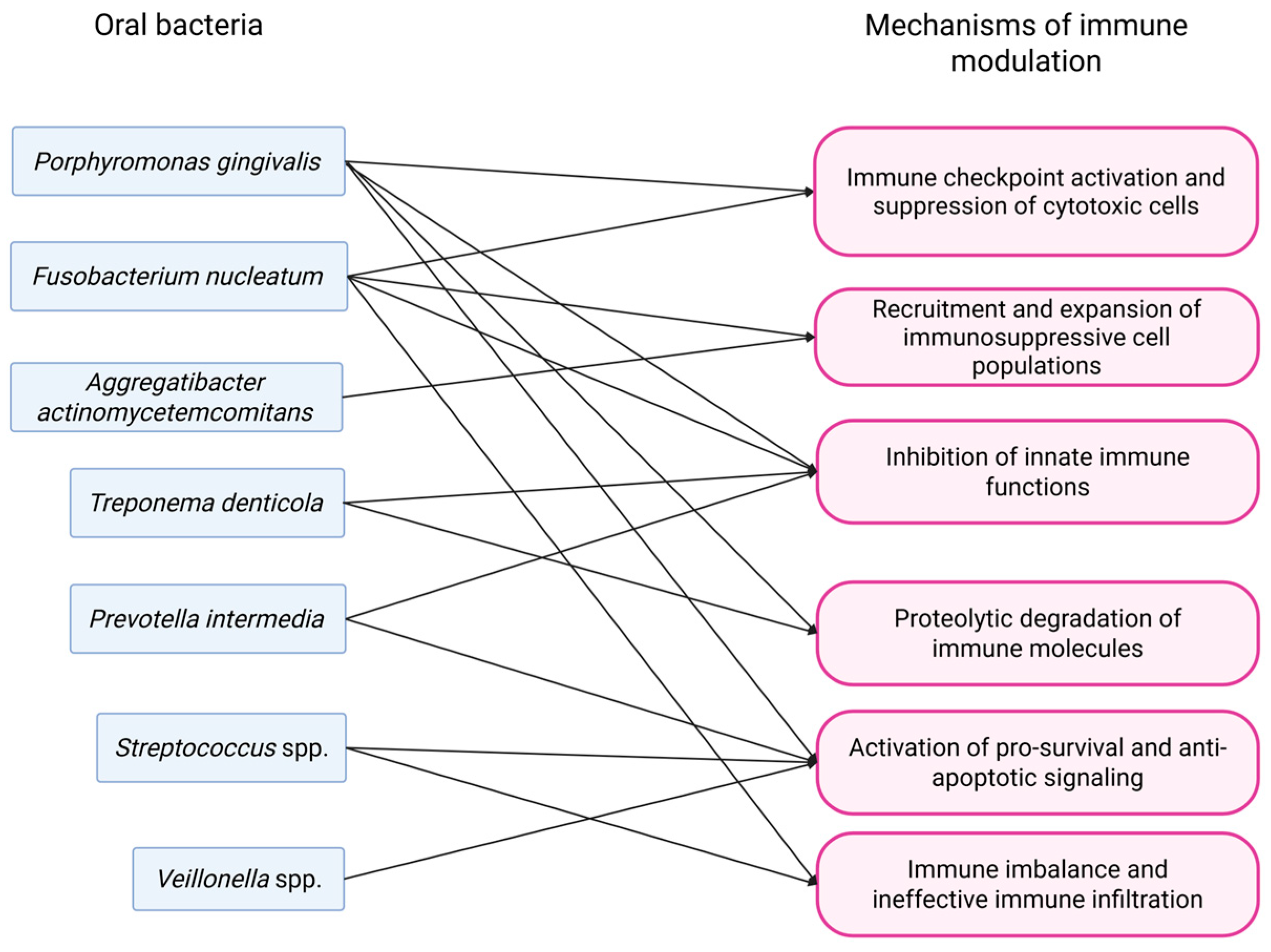

3.3. Modulation of Immune Response

3.3.1. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma

3.3.2. Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma

3.3.3. Colorectal Carcinoma

3.3.4. Lung Cancer

3.3.5. Gastric Cancer

3.3.6. Pancreatic Cancer

3.3.7. Urogenital Cancers

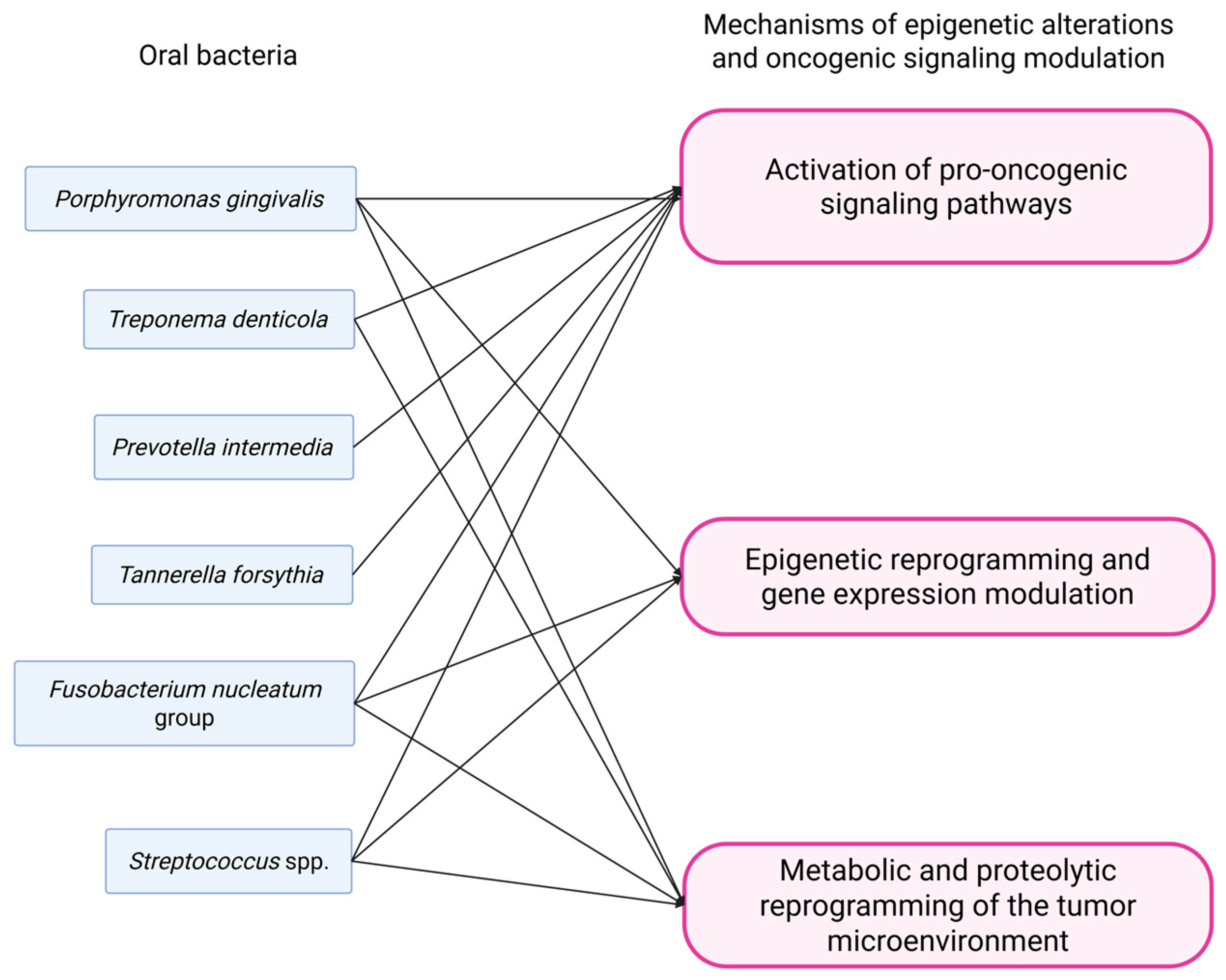

3.4. Epigenetic Alterations and Oncogenic Signaling Pathways Activation/Modulation

3.4.1. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma

3.4.2. Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma

3.4.3. Colorectal Cancer

3.4.4. Lung Cancer

3.4.5. Gastric Cancer

3.4.6. Pancreatic Cancer

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wolf, M.; Steinberg, T.; Scholz, K.J.; Kruse, A.; Rezasoltani, S.; Conrads, G.; Al-Ahmad, A.; Cieplik, F. The Rise and Evolving Role of Fusobacterium nucleatum Subspecies. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2025, 9, 100414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, F.; Xie, M.; Huang, X.; Long, Y.; Lu, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, L. Porphyromonas gingivalis and Its Systemic Impact: Current Status. Pathogens 2020, 9, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, P.; Tian, Z.; Kong, X.; Yang, L.; Shan, X.; Dong, B.; Ding, X.; Jing, X.; Jiang, C.; Jiang, N.; et al. FadA Promotes DNA Damage and Progression of Fusobacterium nucleatum-Induced Colorectal Cancer through up-Regulation of Chk2. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 39, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teshima, R.; Hanada, K.; Akada, J.; Kawano, K.; Yamaoka, Y. Aggregatibacter Actinomycetemcomitans Infection Causes DNA Double-Strand Breaks in Host Cells. Genes Cells 2018, 23, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, Y.; Suo, L.; Zhang, W.; Cao, H.; Wang, R.; Luan, J.; Yu, X.; Dong, L.; Wang, W.; et al. Characterizing Microbiota and Metabolomics Analysis to Identify Candidate Biomarkers in Lung Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1058436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarabi, G.; Heydecke, G.; Seedorf, U. Roles of Oral Infections in the Pathomechanism of Atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannosh, I.; Staletovic, D.; Toljic, B.; Radunovic, M.; Pucar, A.; Petrovic, S.M.; Grubisa, I.; Lazarevic, M.; Brkic, Z.; Vukcevic, J.K.; et al. The Presence of Periopathogenic Bacteria in Subgingival and Atherosclerotic Plaques—An Age Related Comparative Analysis. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2018, 12, 1088–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siggins, M.K.; Sriskandan, S. Bacterial Lymphatic Metastasis in Infection and Immunity. Cells 2022, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benn, A.; Thomson, W. Saliva: An Overview. N. Z. Dent. J. 2014, 110, 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Saini, R.; Saini, S.; Sharma, S. Oral Sex, Oral Health and Orogenital Infections. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2010, 2, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, M.; Li, B.; Huang, Z.; Qin, S.; Nice, E.C.; Tang, J.; Huang, C. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinomas: State of the Field and Emerging Directions. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2023, 15, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyhnalova, T.; Danek, Z.; Gachova, D.; Linhartova, P.B. The Role of the Oral Microbiota in the Etiopathogenesis of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakabadze, M.Z.; Paresishvili, T.; Karalashvili, L.; Chakhunashvili, D.; Kakabadze, Z. Oral Microbiota and Oral Cancer: Review. Oncol. Rev. 2020, 14, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, P.E. Oral Cancer Prevention and Control—The Approach of the World Health Organization. Oral Oncol. 2009, 45, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuominen, H.; Rautava, J. Oral Microbiota and Cancer Development. Pathobiology 2020, 88, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, A.K.; Panda, M.; Das, A.K.; Rahman, T.; Das, R.; Das, K.; Sarma, A.; Kataki, A.C.; Chattopadhyay, I. Dysbiosis of Salivary Microbiome and Cytokines Influence Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma through Inflammation. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M.; Yamaura, C.; Ohara-Nemoto, Y.; Tajika, S.; Kodama, Y.; Ohya, T.; Harada, R.; Kimura, S. Streptococcus anginosus Infection in Oral Cancer and Its Infection Route. Oral Dis. 2005, 11, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, M.; Al-Hebshi, N.N.; Perera, I.; Ipe, D.; Ulett, G.C.; Speicher, D.J.; Chen, T.; Johnson, N.W. Inflammatory Bacteriome and Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 97, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.; Onate, M.D.; Pauley, K.M.; Bhattacharyya, I.; Cha, S. Presence of Porphyromonas gingivalis in Gingival Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2011, 3, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Park, J.; Hosomi, K.; Yamada, T.; Kobayashi, A.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Iketani, S.; Kunisawa, J.; Mizuguchi, K.; Maeda, N.; et al. Analysis of Oral Microbiota in Japanese Oral Cancer Patients Using 16S rRNA Sequencing. J. Oral Biosci. 2019, 61, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, H.J.; Zhang, C.P. The Oral Microbiota May Have Influence on Oral Cancer. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, M.; Rai, A.K.; Rahman, T.; Das, A.; Das, R.; Sarma, A.; Kataki, A.C.; Chattopadhyay, I. Alterations of Salivary Microbial Community Associated with Oropharyngeal and Hypopharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients. Arch. Microbiol. 2020, 202, 785–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Funchain, P.; Bebek, G.; Altemus, J.; Zhang, H.; Niazi, F.; Peterson, C.; Lee, W.T.; Burkey, B.B.; Eng, C. Microbiomic Differences in Tumor and Paired-Normal Tissue in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Genome Med. 2017, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushalkar, S.; Ji, X.; Li, Y.; Estilo, C.; Yegnanarayana, R.; Singh, B.; Li, X.; Saxena, D. Comparison of Oral Microbiota in Tumor and Non-Tumor Tissues of Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. BMC Microbiol. 2012, 12, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mager, D.; Haffajee, A.; Devlin, P.; Norris, C.; Posner, M.; Goodson, J. The Salivary Microbiota as a Diagnostic Indicator of Oral Cancer: A Descriptive, Non-Randomized Study of Cancer-Free and Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Subjects. J. Transl. Med. 2005, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, B.L.; Kuczynski, J.; Bhattacharya, A.; Huey, B.; Corby, P.M.; Queiroz, E.L.S.; Nightingale, K.; Kerr, A.R.; DeLacure, M.D.; Veeramachaneni, R.; et al. Changes in Abundance of Oral Microbiota Associated with Oral Cancer. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.-H.; Chen, H.-M.; Yang, S.-F.; Liang, C.; Peng, C.-Y.; Lin, F.-M.; Tsai, L.-L.; Wu, B.-C.; Hsin, C.-H.; Chuang, C.-Y.; et al. Bacterial Alterations in Salivary Microbiota and Their Association in Oral Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.-Y.; Yeh, Y.-M.; Yu, H.-Y.; Chin, C.-Y.; Hsu, C.-W.; Liu, H.; Huang, P.-J.; Hu, S.-N.; Liao, C.-T.; Chang, K.-P.; et al. Oral Microbiota Community Dynamics Associated With Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Staging. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Chu, M.; Huang, Z.; Yang, X.; Ran, S.; Hu, B.; Zhang, C.; Liang, J. Variations in Oral Microbiota Associated with Oral Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hebshi, N.N.; Nasher, A.T.; Maryoud, M.Y.; Homeida, H.E.; Chen, T.; Idris, A.M.; Johnson, N.W. Inflammatory Bacteriome Featuring Fusobacterium nucleatum and Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Identified in Association with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, S.J.; Crean, S.J.; Lewis, M.A.O.; Spratt, D.A.; Wade, W.G.; Wilson, M.J. Viable Bacteria Present within Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Tissue. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006, 44, 1719–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, S.J.; Crean, S.-J.; Fardy, M.J.; Lewis, M.A.O.; Spratt, D.A.; Wade, W.G.; Wilson, M.J. A Molecular Analysis of the Bacteria Present within Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Med. Microbiol. 2007, 56, 1651–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Geng, F.; Shi, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, X.; Pan, Y. The Prevalence Rate of Periodontal Pathogens and Its Association with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 1393–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Corzo, G.-J.; Infante-Rodríguez, L.-F.; Villamil-Poveda, J.-C.; Bustillo, J.; Cid-Arregui, A.; García-Robayo, D.-A. Association of Prevotella intermedia with Oropharyngeal Cancer: A Patient-Control Study. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abnet, C.C.; Arnold, M.; Wei, W.-Q. Epidemiology of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, H.-C.; Lin, M.-Y.; Lin, F.-C.; Chiang, N.-J.; Wang, Y.-C.; Lai, W.-W.; Chang, W.-L.; Sheu, B.-S. Transferrin and Prealbumin Identify Esophageal Cancer Patients with Malnutrition and Poor Prognosis in Patients with Normal Albuminemia: A Cohort Study. Nutr. Cancer 2022, 74, 3546–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Meng, L. Comparative Genomic Analysis of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Adenocarcinoma: New Opportunities towards Molecularly Targeted Therapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 1054–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagergren, J.; Smyth, E.; Cunningham, D.; Lagergren, P. Oesophageal Cancer. Lancet 2017, 390, 2383–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Lu, X.; Nossa, C.W.; Francois, F.; Peek, R.M.; Pei, Z. Inflammation and Intestinal Metaplasia of the Distal Esophagus Are Associated With Alterations in the Microbiome. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, J.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S. Characterization of Esophageal Microbiota in Patients With Esophagitis and Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 774330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; He, R.; Hou, G.; Ming, W.; Fan, T.; Chen, L.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, W.; Wang, W.; Lu, Z.; et al. Characterization of the Esophageal Microbiota and Prediction of the Metabolic Pathways Involved in Esophageal Cancer. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, X.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, J.; Shen, B.; Zhao, L.; Wang, J. Comprehensive Analysis of the Glycolysis-Related Gene Prognostic Signature and Immune Infiltration in Endometrial Cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 9, 797826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; Vogtmann, E.; Liu, A.; Qin, J.; Chen, W.; Abnet, C.C.; Wei, W. Microbial Characterization of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Gastric Cardia Adenocarcinoma from a High-risk Region of China. Cancer 2019, 125, 3993–4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, H.; Huang, N.; Li, D.; Luo, C.; Wang, T. Characteristics of Oral Microbiota in Patients with Esophageal Cancer in China. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 2259093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xian, B.; Wei, J.; Chen, Y.; Yang, D.; Lai, X.; Liu, L.; Wu, Y.; Lin, X.; Deng, Y.; et al. Predictive Value of the Presence of Prevotella and the Ratio of Porphyromonas gingivalis to Prevotella in Saliva for Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 997333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Li, S.; Ma, Z.; Liang, S.; Shan, T.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, P.; Liu, G.; Zhou, F.; et al. Presence of Porphyromonas gingivalis in Esophagus and Its Association with the Clinicopathological Characteristics and Survival in Patients with Esophageal Cancer. Infect. Agents Cancer 2016, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Yang, T.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Xia, Y.; Xiao, H.; Han, H.; et al. Alterations of Oral Microbiota in Chinese Patients With Esophageal Cancer. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 541144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Winckler, B.; Lu, M.; Cheng, H.; Yuan, Z.; Yang, Y.; Jin, L.; Ye, W. Oral Microbiota and Risk for Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma in a High-Risk Area of China. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, B.A.; Wu, J.; Pei, Z.; Yang, L.; Purdue, M.P.; Freedman, N.D.; Jacobs, E.J.; Gapstur, S.M.; Hayes, R.B.; Ahn, J. Oral Microbiome Composition Reflects Prospective Risk for Esophageal Cancers. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 6777–6787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, M.; Ikeda, Y.; Ikeda, E.; Takahashi, M.; Tanaka, D.; Nakajima, Y.; Arakawa, S.; Izumi, Y.; Miyake, S. Oral Infectious Bacteria in Dental Plaque and Saliva as Risk Factors in Patients with Esophageal Cancer. Cancer 2021, 127, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, L.; Lin, L.; Jin, D.; Du, Y.; Lyu, J. Research Progress on Gut Microbiota in Patients with Gastric Cancer, Esophageal Cancer, and Small Intestine Cancer. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 4415–4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Lin, Y.; Chen, Y.; Peng, X.; He, F.; Liu, S.; Yan, S.; Huang, L.; Lu, W.; et al. Streptococcus and Prevotella Are Associated with the Prognosis of Oesophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Med. Microbiol. 2018, 67, 1058–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Shi, C.; Zheng, J.; Guo, Y.; Fan, T.; Zhao, H.; Jian, D.; Cheng, X.; Tang, H.; Ma, J. Fusobacterium nucleatum Predicts a High Risk of Metastasis for Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessède, E.; Mégraud, F. Microbiota and Gastric Cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 86, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castaño-Rodríguez, N.; Kaakoush, N.O.; Pardo, A.L.; Goh, K.-L.; Fock, K.M.; Mitchell, H.M. Genetic Polymorphisms in the Toll-like Receptor Signalling Pathway in Helicobacter pylori Infection and Related Gastric Cancer. Hum. Immunol. 2014, 75, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, U.; Tripathi, S.; Kumar, S.; Mittal, B.; Chourasia, D.; Kumari, N.; Krishnani, N.; Ghoshal, U.C. Genetic Polymorphism of Cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A1, CYP1A2, and CYP2E1 Genes Modulate Susceptibility to Gastric Cancer in Patients with Helicobacter pylori Infection. Gastric Cancer 2014, 17, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.-H.; Wang, Y.-D.; Luo, H.; Zhao, K.; Huang, G.-L.; Luo, S.-Y.; Peng, J.-X.; Song, J.-K. Association between Tooth Loss and Gastric Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.-L.; Pang, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.-J. The Gastric Microbiome Is Perturbed in Advanced Gastric Adenocarcinoma Identified Through Shotgun Metagenomics. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Sun, J.; Ren, L.; Cao, X.; Dong, J.; Tao, K.; Guan, X.; Cui, Y.; Su, W. Intestinal Microbiota Is Altered in Patients with Gastric Cancer from Shanxi Province, China. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2019, 64, 1193–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, C.; Xu, S.; Xiang, C.; Wang, R.; Yang, D.; Lu, B.; Shi, L.; Tong, R.; Teng, Y.; et al. Fecal Microbiome Alteration May Be a Potential Marker for Gastric Cancer. Dis. Markers 2020, 2020, 3461315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Dai, J.; Lan, X.; Fan, B.; Dong, T.; Zhang, Y.; Han, M. Intestinal Bacteria Are Potential Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets for Gastric Cancer. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 151, 104747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Ma, Y.; Wang, B.; Ci, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Dou, C.; Gu, Q.; An, Y.; et al. Study on the Characteristics of Intestinal Flora Composition in Gastric Cancer Patients and Healthy People in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 194, 1510–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño-Rodríguez, N.; Goh, K.-L.; Fock, K.M.; Mitchell, H.M.; Kaakoush, N.O. Dysbiosis of the Microbiome in Gastric Carcinogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Xu, S.; Xiang, C.; Cao, Q.; Li, Q.; Huang, J.; Shi, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhan, Z. Tongue Coating Microbiota Community and Risk Effect on Gastric Cancer. J. Cancer 2018, 9, 4039–4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, J.; Xin, Y.; Geng, C.; Tian, Z.; Yu, X.; Dong, Q. Bacterial Overgrowth and Diversification of Microbiota in Gastric Cancer. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 28, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.-H.; Wang, A.; Chu, A.-N.; Gong, Y.-H.; Yuan, Y. Mucosa-Associated Microbiota in Gastric Cancer Tissues Compared With Non-Cancer Tissues. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baidoun, F.; Elshiwy, K.; Elkeraie, Y.; Merjaneh, Z.; Khoudari, G.; Sarmini, M.T.; Gad, M.; Al-Husseini, M.; Saad, A. Colorectal Cancer Epidemiology: Recent Trends and Impact on Outcomes. Curr. Drug Targets 2021, 22, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.G.; Karlitz, J.J.; Yen, T.; Lieu, C.H.; Boland, C.R. The Rising Tide of Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer: A Comprehensive Review of Epidemiology, Clinical Features, Biology, Risk Factors, Prevention, and Early Detection. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawla, P.; Sunkara, T.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of Colorectal Cancer: Incidence, Mortality, Survival, and Risk Factors. Prz. Gastroenterol. 2019, 14, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasperson, K.W.; Tuohy, T.M.; Neklason, D.W.; Burt, R.W. Hereditary and Familial Colon Cancer. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 2044–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.-C.; Zhou, Y.-L.; Fang, J.-Y. Oral Pathogen in the Pathogenesis of Colorectal Cancer. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 37, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullman, S.; Pedamallu, C.S.; Sicinska, E.; Clancy, T.E.; Zhang, X.; Cai, D.; Neuberg, D.; Huang, K.; Guevara, F.; Nelson, T.; et al. Analysis of Fusobacterium Persistence and Antibiotic Response in Colorectal Cancer. Science 2017, 358, 1443–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadgar-Zankbar, L.; Elahi, Z.; Shariati, A.; Khaledi, A.; Razavi, S.; Khoshbayan, A. Exploring the Role of Fusobacterium nucleatum in Colorectal Cancer: Implications for Tumor Proliferation and Chemoresistance. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suehiro, Y.; Sakai, K.; Nishioka, M.; Hashimoto, S.; Takami, T.; Higaki, S.; Shindo, Y.; Hazama, S.; Oka, M.; Nagano, H.; et al. Highly Sensitive Stool DNA Testing of Fusobacterium nucleatum as a Marker for Detection of Colorectal Tumours in a Japanese Population. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2017, 54, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudra, A.; Muszyński, D.; Sobocki, B.K.; Atzeni, A.; Carbone, L.; Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka, K.; Połom, K.; Kalinowski, L. Insights into Oral Microbiome and Colorectal Cancer—On the Way of Searching New Perspectives. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1159822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueva, C.; Silva, M.; Pinillos, I.; Bartolomé, B.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V. Interplay between Dietary Polyphenols and Oral and Gut Microbiota in the Development of Colorectal Cancer. Nutrients 2020, 12, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobocki, B.K.; Basset, C.A.; Bruhn-Olszewska, B.; Olszewski, P.; Szot, O.; Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka, K.; Guziak, M.; Nibali, L.; Leone, A. Molecular Mechanisms Leading from Periodontal Disease to Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, Y.; Xie, Y.-H.; Jiang, S.-S.; Kang, Z.-R.; Chen, Y.-X.; Chen, Z.-F.; Fang, J.-Y. Alterations in the Oral and Gut Microbiome of Colorectal Cancer Patients and Association with Host Clinical Factors. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 149, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komiya, Y.; Shimomura, Y.; Higurashi, T.; Sugi, Y.; Arimoto, J.; Umezawa, S.; Uchiyama, S.; Matsumoto, M.; Nakajima, A. Patients with Colorectal Cancer Have Identical Strains of Fusobacterium nucleatum in Their Colorectal Cancer and Oral Cavity. Gut 2019, 68, 1335–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-Y.; Ge, Q.-X.; Cao, J.; Zhou, Y.-J.; Du, Y.-L.; Shen, B.; Wan, Y.-J.Y.; Nie, Y.-Q. Association of Fusobacterium nucleatum Infection with Colorectal Cancer in Chinese Patients. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 3227–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, P.H.M.; Subramanya, R.; Mou, Q.; Lee, K.T.-W.; Islam, F.; Gopalan, V.; Lu, C.-T.; Lam, A.K.-Y. Characterization of Mucosa-Associated Microbiota in Matched Cancer and Non-Neoplastic Mucosa From Patients With Colorectal Cancer. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galeano Niño, J.L.; Wu, H.; LaCourse, K.D.; Kempchinsky, A.G.; Baryiames, A.; Barber, B.; Futran, N.; Houlton, J.; Sather, C.; Sicinska, E.; et al. Effect of the Intratumoral Microbiota on Spatial and Cellular Heterogeneity in Cancer. Nature 2022, 611, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younginger, B.S.; Mayba, O.; Reeder, J.; Nagarkar, D.R.; Modrusan, Z.; Albert, M.L.; Byrd, A.L. Enrichment of Oral-Derived Bacteria in Inflamed Colorectal Tumors and Distinct Associations of Fusobacterium in the Mesenchymal Subtype. Cell Rep. Med. 2023, 4, 100920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemer, B.; Warren, R.D.; Barrett, M.P.; Cisek, K.; Das, A.; Jeffery, I.B.; Hurley, E.; O’Riordain, M.; Shanahan, F.; O’Toole, P.W. The Oral Microbiota in Colorectal Cancer Is Distinctive and Predictive. Gut 2018, 67, 1454–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemer, B.; Lynch, D.B.; Brown, J.M.R.; Jeffery, I.B.; Ryan, F.J.; Claesson, M.J.; O’Riordain, M.; Shanahan, F.; O’Toole, P.W. Tumour-Associated and Non-Tumour-Associated Microbiota in Colorectal Cancer. Gut 2017, 66, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftus, M.; Hassouneh, S.A.-D.; Yooseph, S. Bacterial Community Structure Alterations within the Colorectal Cancer Gut Microbiome. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.; Dowling, R.B.; Jackson, A.D. The Biology of Bacterial Colonization and Invasion of the Respiratory Mucosa. Eur. Respir. J. 1996, 9, 1523–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlson, E.S.; Bittinger, K.; Haas, A.R.; Fitzgerald, A.S.; Frank, I.; Yadav, A.; Bushman, F.D.; Collman, R.G. Topographical Continuity of Bacterial Populations in the Healthy Human Respiratory Tract. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 184, 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, A.; Beck, J.M.; Schloss, P.D.; Campbell, T.B.; Crothers, K.; Curtis, J.L.; Flores, S.C.; Fontenot, A.P.; Ghedin, E.; Huang, L.; et al. Comparison of the Respiratory Microbiome in Healthy Nonsmokers and Smokers. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 187, 1067–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassis, C.M.; Erb-Downward, J.R.; Dickson, R.P.; Freeman, C.M.; Schmidt, T.M.; Young, V.B.; Beck, J.M.; Curtis, J.L.; Huffnagle, G.B. Analysis of the Upper Respiratory Tract Microbiotas as the Source of the Lung and Gastric Microbiotas in Healthy Individuals. mBio 2015, 6, e00037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, R.P.; Erb-Downward, J.R.; Huffnagle, G.B. Towards an Ecology of the Lung: New Conceptual Models of Pulmonary Microbiology and Pneumonia Pathogenesis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2014, 2, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson, R.P.; Erb-Downward, J.R.; Freeman, C.M.; McCloskey, L.; Beck, J.M.; Huffnagle, G.B.; Curtis, J.L. Spatial Variation in the Healthy Human Lung Microbiome and the Adapted Island Model of Lung Biogeography. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2015, 12, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarner, F.; Malagelada, J.R. Gut Flora in Health and Disease. Lancet 2003, 361, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bello, S.; Vengoechea, J.J.; Ponce-Alonso, M.; Figueredo, A.L.; Mincholé, E.; Rezusta, A.; Gambó, P.; Pastor, J.M.; Galeano, J.; Del Campo, R. Core Microbiota in Central Lung Cancer with Streptococcal Enrichment as a Possible Diagnostic Marker. Arch. Bronconeumol. (Engl. Ed.) 2021, 57, 681–689. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, R.P.; Martinez, F.J.; Huffnagle, G.B. The Role of the Microbiome in Exacerbations of Chronic Lung Diseases. Lancet 2014, 384, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natalini, J.G.; Singh, S.; Segal, L.N. The Dynamic Lung Microbiome in Health and Disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, R.P.; Erb-Downward, J.R.; Freeman, C.M.; McCloskey, L.; Falkowski, N.R.; Huffnagle, G.B.; Curtis, J.L. Bacterial Topography of the Healthy Human Lower Respiratory Tract. MBio 2017, 8, e02287-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, F.; Tian, Z. Role of Microbiota on Lung Homeostasis and Diseases. Sci. China Life Sci. 2017, 60, 1407–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpiński, T.M. Role of Oral Microbiota in Cancer Development. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molyneaux, P.L.; Cox, M.J.; Willis-Owen, S.A.G.; Mallia, P.; Russell, K.E.; Russell, A.-M.; Murphy, E.; Johnston, S.L.; Schwartz, D.A.; Wells, A.U.; et al. The Role of Bacteria in the Pathogenesis and Progression of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 190, 906–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.J.; Nelson, C.E.; Brodie, E.L.; DeSantis, T.Z.; Baek, M.S.; Liu, J.; Woyke, T.; Allgaier, M.; Bristow, J.; Wiener-Kronish, J.P. Airway Microbiota and Bronchial Hyperresponsiveness in Patients with Suboptimally Controlled Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 127, 372–381.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, P.; Salimian, J.; Ahmadi, A.; Imani Fooladi, A.A. The Transient but Not Resident (TBNR) Microbiome: A Yin Yang Model for Lung Immune System. Inhal. Toxicol. 2015, 27, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsson, G.G.; Comer, D.M.; McIlreavey, L.; Parkhill, J.; Ennis, M.; Tunney, M.M.; Elborn, J.S. Community Dynamics and the Lower Airway Microbiota in Stable Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Smokers and Healthy Non-Smokers. Thorax 2016, 71, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Schiller, J.H.; Gazdar, A.F. Lung Cancer in Never Smokers—A Different Disease. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 778–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Sung, J.Y.; Yong, D.; Chun, J.; Kim, S.Y.; Song, J.H.; Chung, K.S.; Kim, E.Y.; Jung, J.Y.; Kang, Y.A.; et al. Characterization of Microbiome in Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid of Patients with Lung Cancer Comparing with Benign Mass like Lesions. Lung Cancer 2016, 102, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsay, J.-C.J.; Wu, B.G.; Badri, M.H.; Clemente, J.C.; Shen, N.; Meyn, P.; Li, Y.; Yie, T.-A.; Lhakhang, T.; Olsen, E. Airway Microbiota Is Associated with Upregulation of the PI3K Pathway in Lung Cancer. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, 1188–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greathouse, K.L.; White, J.R.; Vargas, A.J.; Bliskovsky, V.V.; Beck, J.A.; von Muhlinen, N.; Polley, E.C.; Bowman, E.D.; Khan, M.A.; Robles, A.I. Interaction between the Microbiome and TP53 in Human Lung Cancer. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yuan, X.; Chen, K.; Zhou, F.; Yang, H.; Yang, H.; Qi, Y.; Kong, J.; Sun, W.; Gao, S. Clinical Significance and Prognostic Value of Porphyromonas gingivalis Infection in Lung Cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 14, 100972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.A.; Hayes, R.B.; Goparaju, C.; Reid, C.; Pass, H.I.; Ahn, J. The Microbiome in Lung Cancer Tissue and Recurrence-Free Survival. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2019, 28, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Yang, M.; Liu, J.; Gao, R.; Hu, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Shi, Y.; Guo, H.; Cheng, J.; et al. Discovery and Validation of Potential Bacterial Biomarkers for Lung Cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2015, 5, 3111–3122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Lu, J.; Beck, J.D.; Moss, K.L.; Prizment, A.E.; Demmer, R.T.; Porosnicu Rodriguez, K.A.; Joshu, C.E.; Michaud, D.S.; Platz, E.A. Periodontal and Other Oral Bacteria and Risk of Lung Cancer in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2023, 32, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coussens, L.M.; Werb, Z. Inflammation and Cancer. Nature 2002, 420, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Noci, V.; Bernardo, G.; Bianchi, F.; Tagliabue, E.; Sommariva, M.; Sfondrini, L. Toll Like Receptors as Sensors of the Tumor Microbial Dysbiosis: Implications in Cancer Progression. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 732192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Mu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, J.; Liang, C.; Chen, B.; Wang, J.; Zhao, C.; Zuo, Z.; et al. Dysbiosis of the Salivary Microbiome Is Associated With Non-Smoking Female Lung Cancer and Correlated With Immunocytochemistry Markers. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Hu, S.; Cao, C.; Xiao, H. In-Depth Metaproteomics Analysis of Oral Microbiome for Lung Cancer. Research 2022, 2022, 9781578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, D.; Forman, D.; Ferlay, J.; Brinton, L.A.; Cook, M.B. An International Comparison of Male and Female Breast Cancer Incidence Rates. Int. J. Cancer 2013, 132, 1918–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamińska, M.; Ciszewski, T.; Łopacka-Szatan, K.; Miotła, P.; Starosławska, E. Breast Cancer Risk Factors. Menopause Rev./Prz. Menopauzalny 2015, 14, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbaniak, C.; Cummins, J.; Brackstone, M.; Macklaim, J.M.; Gloor, G.B.; Baban, C.K.; Scott, L.; O’Hanlon, D.M.; Burton, J.P.; Francis, K.P.; et al. Microbiota of Human Breast Tissue. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 3007–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, C.; Shamonki, J.M.; Chung, A.; Dinome, M.L.; Chung, M.; Sieling, P.A.; Lee, D.J. Microbial Dysbiosis Is Associated with Human Breast Cancer. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e83744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, R.; Marino, N.; Hemmerich, C.; Podicheti, R.; Rusch, D.B.; Stiemsma, L.T.; Gao, H.; Xuei, X.; Rockey, P.; Storniolo, A.M. Exploring Breast Tissue Microbial Composition and the Association with Breast Cancer Risk Factors. Breast Cancer Res. 2023, 25, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzeng, A.; Sangwan, N.; Jia, M.; Liu, C.-C.; Keslar, K.S.; Downs-Kelly, E.; Fairchild, R.L.; Al-Hilli, Z.; Grobmyer, S.R.; Eng, C. Human Breast Microbiome Correlates with Prognostic Features and Immunological Signatures in Breast Cancer. Genome Med. 2021, 13, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minelli, E.B.; Beghini, A.; Vesentini, S.; Marchiori, L.; Nardo, G.; Cerutti, R.; Mortani, E. Intestinal Microflora as an Alternative Metabolic Source of Estrogens in Women with Uterine Leiomyoma and Breast Cancer. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1990, 595, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groh, H.; Schade, K.; Hörhold-Schubert, C. Steroid Metabolism with Intestinal Microorganisms. J. Basic Microbiol. 1993, 33, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransohoff, J.D.; Ritter, V.; Purington, N.; Andrade, K.; Han, S.; Liu, M.; Liang, S.-Y.; John, E.M.; Gomez, S.L.; Telli, M.L.; et al. Antimicrobial Exposure Is Associated with Decreased Survival in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Tian, T.; Wei, Z.; Shih, N.; Feldman, M.D.; Peck, K.N.; DeMichele, A.M.; Alwine, J.C.; Robertson, E.S. Distinct Microbial Signatures Associated with Different Breast Cancer Types. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niccolai, E.; Baldi, S.; Nannini, G.; Gensini, F.; Papi, L.; Vezzosi, V.; Bianchi, S.; Orzalesi, L.; Ramazzotti, M.; Amedei, A. Breast Cancer: The First Comparative Evaluation of Oncobiome Composition between Males and Females. Biol. Sex Differ. 2023, 14, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbaniak, C.; Gloor, G.B.; Brackstone, M.; Scott, L.; Tangney, M.; Reid, G. The Microbiota of Breast Tissue and Its Association with Breast Cancer. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 5039–5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieken, T.J.; Chen, J.; Hoskin, T.L.; Walther-Antonio, M.; Johnson, S.; Ramaker, S.; Xiao, J.; Radisky, D.C.; Knutson, K.L.; Kalari, K.R.; et al. The Microbiome of Aseptically Collected Human Breast Tissue in Benign and Malignant Disease. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regel, I.; Mayerle, J.; Ujjwal Mukund, M. Current Strategies and Future Perspectives for Precision Medicine in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.; Lowenfels, A.B. The Epidemiology of Pancreatitis and Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology 2013, 144, 1252–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iodice, S.; Gandini, S.; Maisonneuve, P.; Lowenfels, A.B. Tobacco and the Risk of Pancreatic Cancer: A Review and Meta-Analysis. Langenbeck’s Arch. Surg. 2008, 393, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chari, S.T.; Leibson, C.L.; Rabe, K.G.; Timmons, L.J.; Ransom, J.; De Andrade, M.; Petersen, G.M. Pancreatic Cancer–Associated Diabetes Mellitus: Prevalence and Temporal Association With Diagnosis of Cancer. Gastroenterology 2008, 134, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hujoel, P.P.; Drangsholt, M.; Spiekerman, C.; Weiss, N.S. An Exploration of the Periodontitis–Cancer Association. Ann. Epidemiol. 2003, 13, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.; Segers, S.; Hayes, R.B. Periodontal Disease, Porphyromonas gingivalis Serum Antibody Levels and Orodigestive Cancer Mortality. Carcinogenesis 2012, 33, 1055–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.S.; Tsai, C.-R.; Chen, L.-T.; Shan, Y.-S. Investigating the Association Between Periodontal Disease and Risk of Pancreatic Cancer. Pancreas 2016, 45, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, J.J.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, H.; Chia, D.; Elashoff, D.; Akin, D.; Paster, B.J.; Joshipura, K.; Wong, D.T.W. Variations of Oral Microbiota Are Associated with Pancreatic Diseases Including Pancreatic Cancer. Gut 2012, 61, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Alekseyenko, A.V.; Wu, J.; Peters, B.A.; Jacobs, E.J.; Gapstur, S.M.; Purdue, M.P.; Abnet, C.C.; Stolzenberg-Solomon, R.; Miller, G.; et al. Human Oral Microbiome and Prospective Risk for Pancreatic Cancer: A Population-Based Nested Case-Control Study. Gut 2018, 67, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, P.J.; Fletcher, E.M.; Gibbons, S.M.; Bouvet, M.; Doran, K.S.; Kelley, S.T. Characterization of the Salivary Microbiome in Patients with Pancreatic Cancer. PeerJ 2015, 3, e1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Ren, Z.; Li, A.; Li, J.; Xu, S.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, J.; Yang, J.; Luo, Q.; Zhou, K.; et al. Tongue Coating Microbiome Data Distinguish Patients with Pancreatic Head Cancer from Healthy Controls. J. Oral Microbiol. 2019, 11, 1563409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, D.S.; Izard, J.; Wilhelm-Benartzi, C.S.; You, D.-H.; Grote, V.A.; Tjønneland, A.; Dahm, C.C.; Overvad, K.; Jenab, M.; Fedirko, V.; et al. Plasma Antibodies to Oral Bacteria and Risk of Pancreatic Cancer in a Large European Prospective Cohort Study. Gut 2013, 62, 1764–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Castillo, E.; Meier, R.; Chung, M.; Koestler, D.C.; Chen, T.; Paster, B.J.; Charpentier, K.P.; Kelsey, K.T.; Izard, J.; Michaud, D.S. The Microbiomes of Pancreatic and Duodenum Tissue Overlap and Are Highly Subject Specific but Differ between Pancreatic Cancer and Noncancer Subjects. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2019, 28, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Fang, C.; Leng, W.-D.; Wu, L.; Li, B.-H.; Wang, X.-H.; Hu, H.; Zeng, X.-T. Oral Microbiota in the Oral-Genitourinary Axis: Identifying Periodontitis as a Potential Risk of Genitourinary Cancers. Mil. Med. Res. 2021, 8, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Yin, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Ge, Y.; Liu, B.; Yao, L. Relationship between Vaginal and Oral Microbiome in Patients of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection and Cervical Cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ece, G.; Aktaş, A.; Caner, A.; Sağlık, İ.; Kula Atik, T.; Ulusan Bağcı, Ö.; Bayındır Bilman, F.; Demirbakan, H.; Güdül Havuz, S.; Kaya, E.; et al. The Urogenital System Microbiota: Is It a New Gamechanger in Urogenital Cancers? Microorganisms 2025, 13, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javadi, K.; Ferdosi-Shahandashti, E.; Rajabnia, M.; Khaledi, M. Vaginal Microbiota and Gynecological Cancers: A Complex and Evolving Relationship. Infect. Agents Cancer 2024, 19, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Håheim, L.L.; Thelle, D.S.; Rønningen, K.S.; Olsen, I.; Schwarze, P.E. Low Level of Antibodies to the Oral Bacterium Tannerella forsythia Predicts Bladder Cancers and Treponema denticola Predicts Colon and Bladder Cancers: A Prospective Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bučević Popović, V.; Šitum, M.; Chow, C.-E.T.; Chan, L.S.; Roje, B.; Terzić, J. The Urinary Microbiome Associated with Bladder Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Ren, Z.; Li, A.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, J.; Xu, S.; Luo, Q.; Zhou, K.; Sun, X.; Zheng, S.; et al. Deep Sequencing Reveals Microbiota Dysbiosis of Tongue Coat in Patients with Liver Carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takuma, R.; Morozumi, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Matsui, T.; Yoneda, M.; Kessoku, T.; Nogami, A.; Tamura, M.; Kamata, Y.; et al. Association between Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Periodontopathic Bacteria: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xi, W.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, L.; Deng, C.; Chen, J.; Sun, C.; Zhang, N.; Xu, J. Oral Microbial Community Analysis of the Patients in the Progression of Liver Cancer. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 149, 104479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, B.Y.; Zhu, X.; Risch, H.A.; Lu, L.; Ma, X.; Irwin, M.L.; Lim, J.K.; Taddei, T.H.; Pawlish, K.S.; Stroup, A.M.; et al. Oral Cyanobacteria and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2022, 31, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; He, Q.; Lu, F.; Chen, K.; Ni, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, B.; Bo, Z.; et al. A Distinct Microbiota Signature Precedes the Clinical Diagnosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2201159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christofakis, E.P.; Miyazaki, H.; Rubink, D.S.; Yeudall, W.A. Roles of CXCL8 in Squamous Cell Carcinoma Proliferation and Migration. Oral Oncol. 2008, 44, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulkareem, A.A.; Shelton, R.M.; Landini, G.; Cooper, P.R.; Milward, M.R. Periodontal Pathogens Promote Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Oral Squamous Carcinoma Cells In Vitro. Cell Adhes. Migr. 2018, 12, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yee, M.; Kim, S.; Sethi, P.; Düzgüneş, N.; Konopka, K. Porphyromonas gingivalis Stimulates IL-6 and IL-8 Secretion in GMSM-K, HSC-3 and H413 Oral Epithelial Cells. Anaerobe 2014, 28, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New, J.; Arnold, L.; Ananth, M.; Alvi, S.; Thornton, M.; Werner, L.; Tawfik, O.; Dai, H.; Shnayder, Y.; Kakarala, K.; et al. Secretory Autophagy in Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Promotes Head and Neck Cancer Progression and Offers a Novel Therapeutic Target. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 6679–6691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, B.P. TNF-Alpha/NF-kappaB/Snail Pathway in Cancer Cell Migration and Invasion. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 102, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Tao, D.; Fang, Y.; Deng, C.; Xu, Q.; Zhou, J. TNF-Alpha Promotes Invasion and Metastasis via NF-Kappa B Pathway in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Med. Sci. Monit. Basic Res. 2017, 23, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uitto, V.-J.; Baillie, D.; Wu, Q.; Gendron, R.; Grenier, D.; Putnins, E.E.; Kanervo, A.; Firth, J.D. Fusobacterium nucleatum Increases Collagenase 3 Production and Migration of Epithelial Cells. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, A.; Baek, K.J.; Shin, J.E.; Choi, Y. Mechanisms of IL-8 Suppression by Treponema denticola in Gingival Epithelial Cells. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2014, 92, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieminen, M.T.; Listyarifah, D.; Hagström, J.; Haglund, C.; Grenier, D.; Nordström, D.; Uitto, V.-J.; Hernandez, M.; Yucel-Lindberg, T.; Tervahartiala, T.; et al. Treponema denticola Chymotrypsin-like Proteinase May Contribute to Orodigestive Carcinogenesis through Immunomodulation. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 118, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, C.D.M.; Calegari-Silva, T.C.; Pereira, R.M.S.; Santos, S.A.d.O.L.; Lopes, U.G.; Plotkowski, M.-C.M.; Saliba, A.M. ExoU Activates NF-κB and Increases IL-8/KC Secretion during Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Infection. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghimi, M.; Bakhtiari, R.; Mehrabadi, J.F.; Jamshidi, N.; Jamshidi, N.; Siyadatpanah, A.; Mitsuwan, W.; Nissapatorn, V. Interaction of Human Oral Cancer and the Expression of Virulence Genes of Dental Pathogenic Bacteria. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 149, 104464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belibasakis, G.N.; Maula, T.; Bao, K.; Lindholm, M.; Bostanci, N.; Oscarsson, J.; Ihalin, R.; Johansson, A. Virulence and Pathogenicity Properties of Aggregatibacter Actinomycetemcomitans. Pathogens 2019, 8, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiko, Y.; Nishimura, M.; Kusano, K.; Nakashima, K.; Okumura, K.; Arakawa, T.; Takuma, T.; Mizoguchi, I.; Kaku, T. Expression of MIP-3alpha/CCL20, a Macrophage Inflammatory Protein in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Arch. Oral Biol. 2003, 48, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, B.A.; Novince, C.M.; Kirkwood, K.L. Aggregatibacter Actinomycetemcomitans, a Potent Immunoregulator of the Periodontal Host Defense System and Alveolar Bone Homeostasis. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2016, 31, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.K.; Gupta, S.; Jiang, B.; Weinberg, A. Fusobacterium nucleatum and Human Beta-Defensins Modulate the Release of Antimicrobial Chemokine CCL20/Macrophage Inflammatory Protein 3α. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79, 4578–4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, S.; Liu, Y.; Duan, X.; Liu, K.; Mohammed, M.; Gu, Z.; Ren, J.; Yakoumatos, L.; Yuan, X.; Lu, L.; et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis Infection Exacerbates Oesophageal Cancer and Promotes Resistance to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 125, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinthamani, S.; Settem, P.R.; Honma, K.; Nakajima, T.; Sharma, A. Purification of Tannerella forsythia Surface-Layer (S-Layer) Proteins. In Periodontal Pathogens; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Smith, S.; Hu, X. Role of Notch Signaling in Regulating Innate Immunity and Inflammation in Health and Disease. Protein Cell 2016, 7, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groblewska, M.; Siewko, M.; Mroczko, B.; Szmitkowski, M. The Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) and Their Inhibitors (TIMPs) in the Development of Esophageal Cancer. Folia Histochem. Cytobiol. 2012, 50, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narikiyo, M.; Tanabe, C.; Yamada, Y.; Igaki, H.; Tachimori, Y.; Kato, H.; Muto, M.; Montesano, R.; Sakamoto, H.; Nakajima, Y.; et al. Frequent and Preferential Infection of Treponema denticola, Streptococcus mitis, and Streptococcus anginosus in Esophageal Cancers. Cancer Sci. 2004, 95, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmi, H.; Akira, S. TLR Signalling and the Function of Dendritic Cells. Chem. Immunol. Allergy 2005, 86, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.B.; He, F.L.; Fang, M.; Hua, T.F.; Hu, B.D.; Zhang, Z.H.; Cao, Q.; Liu, R.Y. Increased Expression of Toll-like Receptors 4 and 9 in Human Lung Cancer. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2009, 36, 1475–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Crozet, L.; Damotte, D.; Iribarren, K.; Schramm, C.; Alifano, M.; Lupo, A.; Cherfils-Vicini, J.; Goc, J.; Katsahian, S.; et al. TLR7 Promotes Tumor Progression, Chemotherapy Resistance, and Poor Clinical Outcomes in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 5008–5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidi, R.; Guerra, L.; Levi, L.; Stenerlöw, B.; Fox, J.G.; Josenhans, C.; Masucci, M.G.; Frisan, T. Chronic Exposure to the Cytolethal Distending Toxins of Gram-Negative Bacteria Promotes Genomic Instability and Altered DNA Damage Response. Cell. Microbiol. 2013, 15, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.R.; Chang, Y.F.; Ma, J.; Chiu, C.H.; Kuo, M.L.; Lai, C.H. From DNA Damage to Cancer Progression: Potential Effects of Cytolethal Distending Toxin. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 760451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lien, E.; Means, T.K.; Heine, H.; Yoshimura, A.; Kusumoto, S.; Fukase, K.; Fenton, M.J.; Oikawa, M.; Qureshi, N.; Monks, B.; et al. Toll-like Receptor 4 Imparts Ligand-Specific Recognition of Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide. J. Clin. Investig. 2000, 105, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Jia, Y.; Wen, L.; Mu, W.; Wu, X.; Liu, T.; Liu, X.; Fang, J.; Luan, Y.; Chen, P.; et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis Promotes Colorectal Carcinoma by Activating the Hematopoietic NLRP3 Inflammasome. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 2745–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bregaint, S.; Boyer, E.; Fong, S.B.; Meuric, V.; Bonnaure-Mallet, M.; Jolivet-Gougeon, A. Porphyromonas gingivalis Outside the Oral Cavity. Odontology 2022, 110, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, S.; Leader, A.M.; Merad, M. MDSC: Markers, Development, States, and Unaddressed Complexity. Immunity 2021, 54, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesi, R.J. MDSC; the Most Important Cell You Have Never Heard Of. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 40, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Liu, Y.; Kong, X.; Wu, R.; Peng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Duan, L. Fusobacterium nucleatum Facilitates M2 Macrophage Polarization and Colorectal Carcinoma Progression by Activating TLR4/NF-κB/S100A9 Cascade. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 658681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostic, A.D.; Chun, E.; Robertson, L.; Glickman, J.N.; Gallini, C.A.; Michaud, M.; Clancy, T.E.; Chung, D.C.; Lochhead, P.; Hold, G.L.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Potentiates Intestinal Tumorigenesis and Modulates the Tumor-Immune Microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Li, Q.; Wu, J.; Wu, Y.; Peng, W.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Tang, X.; Peng, Y.; Fu, X. Fusobacterium nucleatum Promotes M2 Polarization of Macrophages in the Microenvironment of Colorectal Tumours via a TLR4-Dependent Mechanism. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2018, 67, 1635–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Q.; Ma, X.; Yang, B.; Liu, Y.; Xie, Y.; Wang, X.; Yuan, W.; Ma, J. Periodontitis Pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis Promotes Pancreatic Tumorigenesis via Neutrophil Elastase from Tumor-Associated Neutrophils. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2073785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udayasuryan, B.; Ahmad, R.N.; Nguyen, T.T.D.; Umaña, A.; Monét Roberts, L.; Sobol, P.; Jones, S.D.; Munson, J.M.; Slade, D.J.; Verbridge, S.S. Fusobacterium nucleatum Induces Proliferation and Migration in Pancreatic Cancer Cells through Host Autocrine and Paracrine Signaling. Sci. Signal. 2022, 15, eabn4948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, M.; Ikenaga, N.; Nakata, K.; Luo, H.; Zhong, P.; Date, S.; Oyama, K.; Higashijima, N.; Kubo, A.; Iwamoto, C.; et al. Intratumor Fusobacterium nucleatum Promotes the Progression of Pancreatic Cancer via the CXCL1-CXCR2 Axis. Cancer Sci. 2023, 114, 3666–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, S.; Beyaert, R. A Universal Role for MyD88 in TLR/IL-1R-Mediated Signaling. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2002, 27, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ding, J.; Yang, J.; Guo, X.; Zheng, Y. MicroRNA Roles in the Nuclear Factor Kappa B Signaling Pathway in Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Weng, W.; Peng, J.; Hong, L.; Yang, L.; Toiyama, Y.; Gao, R.; Liu, M.; Yin, M.; Pan, C.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Increases Proliferation of Colorectal Cancer Cells and Tumor Development in Mice by Activating Toll-Like Receptor 4 Signaling to Nuclear Factor−κB, and Up-Regulating Expression of MicroRNA-21. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 851–866.e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osaki, T.; Mabe, K.; Hanawa, T.; Kamiya, S. Urease-Positive Bacteria in the Stomach Induce a False-Positive Reaction in a Urea Breath Test for Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori Infection. J. Med. Microbiol. 2008, 57, 814–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsen, S.; Collin-Faure, V.; Gidrol, X.; Lemercier, C. The Opportunistic Pathogen Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Activates the DNA Double-Strand Break Signaling and Repair Pathway in Infected Cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013, 70, 4385–4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateda, M.; Shiga, K.; Saijo, S.; Sone, M.; Hori, T.; Yokoyama, J.; Matsuura, K.; Takasaka, T.; Miyagi, T. Streptococcus anginosus in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Implication in Carcinogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2000, 6, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritani, K.; Takeshita, T.; Shibata, Y.; Ninomiya, T.; Kiyohara, Y.; Yamashita, Y. Acetaldehyde Production by Major Oral Microbes. Oral Dis. 2015, 21, 748–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagaino, R.; Washio, J.; Abiko, Y.; Tanda, N.; Sasaki, K.; Takahashi, N. Metabolic Property of Acetaldehyde Production from Ethanol and Glucose by Oral Streptococcus and Neisseria. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öğrendik, M. Oral Bacteria in Pancreatic Cancer: Mutagenesis of the P53 Tumour Suppressor Gene. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 11835. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, C.; Lagoudas, G.K.; Zhao, C.; Bullman, S.; Bhutkar, A.; Hu, B.; Ameh, S.; Sandel, D.; Liang, X.S.; Mazzilli, S. Commensal Microbiota Promote Lung Cancer Development via Γδ T Cells. Cell 2019, 176, 998–1013.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Park, Y.; Hasegawa, Y.; Tribble, G.D.; James, C.E.; Handfield, M.; Stavropoulos, M.F.; Yilmaz, O.; Lamont, R.J. Intrinsic Apoptotic Pathways of Gingival Epithelial Cells Modulated by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Cell. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 1997–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Shi, D.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, W. The Relationship between Gastric Microbiota and Gastric Disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 54, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, N.S.; Alexander, D.D.; Coughlin, J.R.; Milkowski, A.L.; Boffetta, P. Ingested Nitrate and Nitrite and Stomach Cancer Risk: An Updated Review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 3646–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.J.; Kim, J.; Kim, N.; Park, J.H.; Nam, R.H.; Seok, Y.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, J.M.; et al. Analysis of Gastric Microbiota by Pyrosequencing: Minor Role of Bacteria Other Than Helicobacter pylori in the Gastric Carcinogenesis. Helicobacter 2016, 21, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.-H.; Kim, N.; Jo, H.J.; Kim, J.; Park, J.H.; Nam, R.H.; Seok, Y.-J.; Kim, Y.-R.; Lee, D.H. Analysis of Gastric Body Microbiota by Pyrosequencing: Possible Role of Bacteria Other Than Helicobacter pylori in the Gastric Carcinogenesis. J. Cancer Prev. 2017, 22, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammallahti, H.; Kokkola, A.; Rezasoltani, S.; Ghanbari, R.; Asadzadeh Aghdaei, H.; Knuutila, S.; Puolakkainen, P.; Sarhadi, V.K. Microbiota Alterations and Their Association with Oncogenomic Changes in Pancreatic Cancer Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeger, S.; Domann, E.; Gonzales, J.R.; Chakraborty, T.; Meyle, J. B7-H1 and B7-DC Receptors of Oral Squamous Carcinoma Cells Are Upregulated by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Immunobiology 2011, 216, 1302–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhou, X.; Peng, X.; Li, M.; Ren, B.; Cheng, G.; Cheng, L. Porphyromonas gingivalis Promotes Immunoevasion of Oral Cancer by Protecting Cancer from Macrophage Attack. J. Immunol. 2020, 205, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuzillet, C.; Marchais, M.; Vacher, S.; Hilmi, M.; Schnitzler, A.; Meseure, D.; Leclere, R.; Lecerf, C.; Dubot, C.; Jeannot, E.; et al. Prognostic Value of Intratumoral Fusobacterium nucleatum and Association with Immune-Related Gene Expression in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gur, C.; Ibrahim, Y.; Isaacson, B.; Yamin, R.; Abed, J.; Gamliel, M.; Enk, J.; Bar-On, Y.; Stanietsky-Kaynan, N.; Coppenhagen-Glazer, S.; et al. Binding of the Fap2 Protein of Fusobacterium nucleatum to Human Inhibitory Receptor TIGIT Protects Tumors from Immune Cell Attack. Immunity 2015, 42, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gur, C.; Maalouf, N.; Shhadeh, A.; Berhani, O.; Singer, B.B.; Bachrach, G.; Mandelboim, O. Fusobacterium nucleatum Supresses Anti-Tumor Immunity by Activating CEACAM1. Oncoimmunology 2019, 8, e1581531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, A.A.; Patil, R.S.; Pradhan, T.N.; Chaukar, D.A.; D’Cruz, A.K.; Chiplunkar, S.V. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Impede T Cell Functionality and Promote Th17 Differentiation in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2020, 69, 1071–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Arévalo, F.; Leija-Montoya, A.G.; González-Ramírez, J.; Isiordia-Espinoza, M.; Serafín-Higuera, I.; Fuchen-Ramos, D.M.; Vazquez-Jimenez, J.G.; Serafín-Higuera, N. Modulation of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell Functions by Oral Inflammatory Diseases and Important Oral Pathogens. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1349067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Ghosh, S.K.; Shokeen, B.; Eapan, B.; Lux, R.; Kiselar, J.; Nithianantham, S.; Young, A.; Pandiyan, P.; McCormick, T.S.; et al. FAD-I, a Fusobacterium nucleatum Cell Wall-Associated Diacylated Lipoprotein That Mediates Human Beta Defensin 2 Induction through Toll-Like Receptor-1/2 (TLR-1/2) and TLR-2/6. Infect. Immun. 2016, 84, 1446–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.E.; Choi, Y. Treponema denticola Suppresses Expression of Human Beta-Defensin-2 in Gingival Epithelial Cells through Inhibition of TNFalpha Production and TLR2 Activation. Mol. Cells 2010, 29, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, A.; Jin, J.-O.; Johnston, C.D.; Yamazaki, H.; Houri-Haddad, Y.; Rittling, S.R. Pathogenic Bacterial Species Associated with Endodontic Infection Evade Innate Immune Control by Disabling Neutrophils. Infect. Immun. 2014, 82, 4068–4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, S.-G.; Yang, J.-Q.; Ma, Z.-K.; Yuan, X.; Zhao, C.; Wang, G.-C.; Wei, H.; Feng, X.-S.; Qi, Y.-J. Preoperative Serum Immunoglobulin G and A Antibodies to Porphyromonas gingivalis Are Potential Serum Biomarkers for the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, H.; Dai, N.; Zhang, N.; Sun, W.; Guo, Y.; Kong, J.; Wang, X.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Induces MDSCs Enrichment via Activation the NLRP3 Inflammosome in ESCC Cells, Leading to Cisplatin Resistance. Ann. Med. 2022, 54, 989–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, M.A.; Aduse-Opoku, J.; Rangarajan, M. Cysteine Proteases of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 2001, 12, 192–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.E.; Kim, J.H.; Cho, N.-Y.; Lee, H.S.; Kang, G.H. Intratumoral Fusobacterium nucleatum Abundance Correlates with Macrophage Infiltration and CDKN2A Methylation in Microsatellite-Unstable Colorectal Carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2017, 471, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, M. Control of Regulatory T-Cell Differentiation and Function by T-Cell Receptor Signalling and Foxp3 Transcription Factor Complexes. Immunology 2020, 160, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, T.; Nishikawa, H.; Wada, H.; Nagano, Y.; Sugiyama, D.; Atarashi, K.; Maeda, Y.; Hamaguchi, M.; Ohkura, N.; Sato, E.; et al. Two FOXP3(+)CD4(+) T Cell Subpopulations Distinctly Control the Prognosis of Colorectal Cancers. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abed, J.; Emgård, J.E.M.; Zamir, G.; Faroja, M.; Almogy, G.; Grenov, A.; Sol, A.; Naor, R.; Pikarsky, E.; Atlan, K.A.; et al. Fap2 Mediates Fusobacterium nucleatum Colorectal Adenocarcinoma Enrichment by Binding to Tumor-Expressed Gal-GalNAc. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 20, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, M.R.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Hao, Y.; Cai, G.; Han, Y.W. Fusobacterium nucleatum Promotes Colorectal Carcinogenesis by Modulating E-Cadherin/β-Catenin Signaling via Its FadA Adhesin. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casasanta, M.A.; Yoo, C.C.; Udayasuryan, B.; Sanders, B.E.; Umaña, A.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, H.; Duncan, A.J.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Host-Cell Binding and Invasion Induces IL-8 and CXCL1 Secretion That Drives Colorectal Cancer Cell Migration. Sci. Signal. 2020, 13, eaba9157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, M.C.; Er, E.E.; Blenis, J. The Ras-ERK and PI3K-mTOR Pathways: Cross-Talk and Compensation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2011, 36, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, A.M.; Soldi, R.; Anderlind, C.; Scholand, M.B.; Qian, J.; Zhang, X.; Cooper, K.; Walker, D.; McWilliams, A.; Liu, G.; et al. Airway PI3K Pathway Activation Is an Early and Reversible Event in Lung Cancer Development. Sci. Transl. Med. 2010, 2, 26ra25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Yang, Y.; Yu, J.; Dang, T.; Qin, W.; Teng, L.; Ye, J.; Jiang, H. Interactions between Gastric Microbiota and Metabolites in Gastric Cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraki, D.; Uehara, O.; Kuramitsu, Y.; Morikawa, T.; Harada, F.; Yoshida, K.; Akino, K.; Chiba, I.; Asaka, M.; Abiko, Y.P. gingivalis Lipopolysaccharide Stimulates the Upregulated Expression of the Pancreatic Cancer-Related Genes Regenerating Islet-Derived 3 A/G in Mouse Pancreas. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanasekaran, J.; Binder Gallimidi, A.; Saba, E.; Pandi, K.; Eli Berchoer, L.; Hermano, E.; Angabo, S.; Makkawi, H.A.; Khashan, A.; Daoud, A.; et al. Intracellular Porphyromonas gingivalis Promotes the Tumorigenic Behavior of Pancreatic Carcinoma Cells. Cancers 2020, 12, 2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groeger, S.; Jarzina, F.; Domann, E.; Meyle, J. Porphyromonas gingivalis Activates NFκB and MAPK Pathways in Human Oral Epithelial Cells. BMC Immunol. 2017, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Pan, C.; Zhang, D.; Li, X.; Pan, Y. Porphyromonas gingivalis Infection Promoted the Proliferation of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells through the miR-21/PDCD4/AP-1 Negative Signaling Pathway. ACS Infect. Dis. 2019, 5, 1336–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arjunan, P.; Meghil, M.M.; Pi, W.; Xu, J.; Lang, L.; El-Awady, A.; Sullivan, W.; Rajendran, M.; Rabelo, M.S.; Wang, T.; et al. Oral Pathobiont Activates Anti-Apoptotic Pathway, Promoting Both Immune Suppression and Oncogenic Cell Proliferation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Sztukowska, M.; Ojo, A.; Scott, D.A.; Wang, H.; Lamont, R.J. FOXO Responses to Porphyromonas gingivalis in Epithelial Cells. Cell. Microbiol. 2015, 17, 1605–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, B.H.; Kim, D.J.; Choi, J.I.; Kim, S.J.; Park, B.S.; Song, J.M.; Lee, J.H.; Park, H.R. Oral Cancer Cells Sustainedly Infected with Porphyromonas gingivalis Exhibit Resistance to Taxol and Have Higher Metastatic Potential. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 46981–46992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamarajan, P.; Ateia, I.; Shin, J.M.; Fenno, J.C.; Le, C.; Zhan, L.; Chang, A.; Darveau, R.; Kapila, Y.L. Periodontal Pathogens Promote Cancer Aggressivity via TLR/MyD88 Triggered Activation of Integrin/FAK Signaling That Is Therapeutically Reversible by a Probiotic Bacteriocin. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, R.T.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, X.D.; Liu, S.Y.; Han, Q.; Cheng, L.; Peng, X. Treponema denticola Promotes OSCC Development via the TGF-β Signaling Pathway. J. Dent. Res. 2022, 101, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listyarifah, D.; Nieminen, M.T.; Mäkinen, L.K.; Haglund, C.; Grenier, D.; Häyry, V.; Nordström, D.; Hernandez, M.; Yucel-Lindberg, T.; Tervahartiala, T.; et al. Treponema denticola Chymotrypsin-like Proteinase Is Present in Early-stage Mobile Tongue Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Related to the Clinicopathological Features. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2018, 47, 764–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, L.; Chu, L.; Kolodrubetz, D. Multiple Enzymes Can Make Hydrogen Sulfide From Cysteine in Treponema denticola. Anaerobe 2020, 64, 102231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Bian, H.; Li, X.; Wu, H.; Bi, Q.; Yan, Y.; Wang, Y. Hydrogen Sulfide Promotes Cell Proliferation of Oral Cancer through Activation of the COX2/AKT/ERK1/2 Axis. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 35, 2825–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.-M.; Zhang, M.; He, J.-J.; Wu, J.-Z. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases and Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Are Involved in Prevotella intermedia-Induced Proinflammatory Cytokines Expression in Human Periodontal Ligament Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 386, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.-M.; Shu, L.; Fu, S.-M.; Liu, B.; Xu, X.-L.; Wu, J.-Z. Prevotella intermedia Induces Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Expression in Human Periodontal Ligament Cells. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008, 283, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, F.; Liu, J.; Guo, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Zhao, H.; Pan, Y. Persistent Exposure to Porphyromonas gingivalis Promotes Proliferative and Invasion Capabilities, and Tumorigenic Properties of Human Immortalized Oral Epithelial Cells. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Andrade, K.Q.; Almeida-da-Silva, C.L.C.; Coutinho-Silva, R. Immunological Pathways Triggered by Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum: Therapeutic Possibilities? Mediat. Inflamm. 2019, 2019, 7241312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.-F.; Lu, M.-S.; Hsieh, C.-C.; Chen, W.-C. Porphyromonas gingivalis Promotes Tumor Progression in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cell. Oncol. 2021, 44, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birkedal-Hansen, H.; Moore, W.G.I.; Bodden, M.K.; Windsor, L.J.; Birkedal-Hansen, B.; DeCarlo, A.; Engler, J.A. Matrix Metalloproteinases: A Review. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 1993, 4, 197–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomoto, D.; Baba, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tsutsuki, H.; Okadome, K.; Harada, K.; Ishimoto, T.; Iwatsuki, M.; Iwagami, S.; Miyamoto, Y.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Promotes Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Progression via the NOD1/RIPK2/NF-κB Pathway. Cancer Lett. 2022, 530, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Baba, Y.; Ishimoto, T.; Tsutsuki, H.; Zhang, T.; Nomoto, D.; Okadome, K.; Yamamura, K.; Harada, K.; Eto, K.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Confers Chemoresistance by Modulating Autophagy in Oesophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enersen, M.; Nakano, K.; Amano, A. Porphyromonas gingivalis Fimbriae. J. Oral Microbiol. 2013, 5, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, S.; Konishi, Y.; Narukawa, M.; Sugiura, Y.; Yoshimoto, S.; Arai, Y.; Sato, S.; Yoshida, Y.; Tsuji, S.; Uemura, K.; et al. Gut Bacteria Identified in Colorectal Cancer Patients Promote Tumourigenesis via Butyrate Secretion. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, O.; Jungas, T.; Verbeke, P.; Ojcius, D.M. Activation of the Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt Pathway Contributes to Survival of Primary Epithelial Cells Infected with the Periodontal Pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 3743–3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Jermanus, C.; Barbetta, B.; Choi, C.; Verbeke, P.; Ojcius, D.M.; Yilmaz, O. Porphyromonas gingivalis Infection Sequesters Pro-Apoptotic Bad through Akt in Primary Gingival Epithelial Cells. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2010, 25, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffatt, C.E.; Lamont, R.J. Porphyromonas gingivalis Induction of microRNA-203 Expression Controls Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling 3 in Gingival Epithelial Cells. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79, 2632–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwahori, K.; Serada, S.; Fujimoto, M.; Nomura, S.; Osaki, T.; Lee, C.M.; Mizuguchi, H.; Takahashi, T.; Ripley, B.; Okumura, M.; et al. Overexpression of SOCS3 Exhibits Preclinical Antitumor Activity against Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 129, 1005–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, O.; Yao, L.; Maeda, K.; Rose, T.M.; Lewis, E.L.; Duman, M.; Lamont, R.J.; Ojcius, D.M. ATP Scavenging by the Intracellular Pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis Inhibits P2X7-Mediated Host-Cell Apoptosis. Cell. Microbiol. 2008, 10, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuboniwa, M.; Hasegawa, Y.; Mao, S.; Shizukuishi, S.; Amano, A.; Lamont, R.J.; Yilmaz, O.P. gingivalis Accelerates Gingival Epithelial Cell Progression through the Cell Cycle. Microbes Infect. 2008, 10, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, C.; Xu, X.; Tan, L.; Lin, L.; Pan, Y. The Effects of Porphyromonas gingivalis on the Cell Cycle Progression of Human Gingival Epithelial Cells. Oral Dis. 2014, 20, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, M.; Naito, M.; Omori, K.; Ono, S.; Nakayama, K.; Ohara, N. Porphyromonas gingivalis Gingipains Induce Cyclooxygenase-2 Expression and Prostaglandin E2 Production via ERK1/2-Activated AP-1 (c-Jun/c-Fos) and IKK/NF-κB P65 Cascades. J. Immunol. 2022, 208, 1146–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, W.; Jia, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, B. Intracellular Porphyromonas gingivalis Promotes the Proliferation of Colorectal Cancer Cells via the MAPK/ERK Signaling Pathway. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 584798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benakanakere, M.; Abdolhosseini, M.; Hosur, K.; Finoti, L.S.; Kinane, D.F. TLR2 Promoter Hypermethylation Creates Innate Immune Dysbiosis. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wara-aswapati, N.; Chayasadom, A.; Surarit, R.; Pitiphat, W.; Boch, J.A.; Nagasawa, T.; Ishikawa, I.; Izumi, Y. Induction of Toll-Like Receptor Expression by Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Periodontol. 2013, 84, 1010–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.-L.; Azuma, Y.; Shinohara, M.; Ohura, K. Toll-like Receptor 4-Mediated Signal Pathway Induced by Porphyromonas gingivalis Lipopolysaccharide in Human Gingival Fibroblasts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 273, 1161–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivas, M.A.; Carnevale, R.P.; Proietti, C.J.; Rosemblit, C.; Beguelin, W.; Salatino, M.; Charreau, E.H.; Frahm, I.; Sapia, S.; Brouckaert, P. TNFα Acting on TNFR1 Promotes Breast Cancer Growth via P42/P44 MAPK, JNK, Akt and NF-κB-Dependent Pathways. Exp. Cell Res. 2008, 314, 509–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, B.; Wang, H.; Rabbani, Z.N.; Zhao, Y.; Li, W.; Yuan, Y.; Li, F.; Dewhirst, M.W.; Li, C.Y. Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Is a Potent Endogenous Mutagen That Promotes Cellular Transformation. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 11565–11570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, S.; Wu, Z.; Qi, Y.; Wu, B.; Zhu, X. The Metastasizing Mechanisms of Lung Cancer: Recent Advances and Therapeutic Challenges. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 138, 111450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikezawa, K.; Hikita, H.; Shigekawa, M.; Iwahashi, K.; Eguchi, H.; Sakamori, R.; Tatsumi, T.; Takehara, T. Increased Bcl-xL Expression in Pancreatic Neoplasia Promotes Carcinogenesis by Inhibiting Senescence and Apoptosis. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 4, 185–200.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Sample | Sample Type | Oral Bacteria and Main Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 OSCC patients and 24 healthy controls | Saliva | Streptococcus anginosus (S. anginosus), Veillonella parvula, Porphyromonas endodontalis, and Peptostreptococcus anaerobius could contribute to OSCC | [16] |

| 60 OSCC patients and 80 non-cancer controls | Saliva | Peptostreptococcus, Fusobacterium, Alloprevotella, and Capnocytophaga spp. more abundant in OSCC | [20] |

| 45 OSCC patients and 229 OSCC-free patients | Saliva | Capnocytophaga gingivalis, P. melaninogenica, and Streptococcus mitis (S. mitis) elevated in the saliva of individuals with OSCC | [25] |

| 125 OSCC cases, 124 cases of epithelial precursor lesions, and 127 controls | Saliva | Parvimonas spp. present only in OSCC samples compared to epithelial precursor lesions and in healthy sites | [27] |

| 51 controls, 41 OSCC stage 1, 66 OSCC stages 2 and 3, and 90 OSCC stage 4 patients | Oral rinse (sterile saline) | Fusobacterium periodonticum, Parvimonas micra, Streptococcus constellatus, Haemophilus influenzae, and Filifactor alocis associated with OSCC, progressively increased in abundance from stage 1 to stage 4 | [28] |

| 22 OSCC patients, 8 precancer patients, And 6 healthy individuals | Oral mucosal swabs | Fusobacterium significantly present in OSCC compared to contralateral healthy site | [26] |

| 50 patients—50 paired samples were obtained from non-tumor (50) and tumor sites (50) | Swab | F. nucleatum group, P. intermedia, Aggregatibacter segnis, Capnocytophaga leadbetteri, and Peptostreptococcus stomatis significantly increased in OSCC | [21] |

| 40 OSCC patients, 40 controls | Oral mucosal swabs | Mycoplasma, Treponema, Campylobacter, Eikenella, Centipeda, Lachnospiraceae_G_7, Alloprevotella, Fusobacterium, Selenomonas, Dialister, Peptostreptococcus, Filifactor, Peptococcus, Catonella, Parvimonas, and Capnocytophaga were more abundant in OSCC | [29] |

| 20 OSCC samples and 20 deep-epithelium control swabs | OSCC tissue and swab | F. polymorphum (F. nucleatum group) was the most significantly overrepresented species in the tumors, followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) and Campylobacter spp. | [30] |

| 42 OSCC, 2 lymphoma, 2 rhabdomyosarcoma, and 3 leukoplakia | Tissue | S. anginosus present in OSCC (19/42) and not in the other type of oral cancers nor in the leukoplakia | [17] |

| 25 OSCC patients and 27 patients with fibroepithelial polyp | Tissue | Genera Capnocytophaga, Pseudomonas, and Atopobium associated with OSCC | [18] |

| 10 OSCC and 5 normal gingiva samples | Paraffin-embedded gingival tissue | Higher levels of P. gingivalis (more than 33%) detected in OSCC samples | [19] |

| 169 patients with paired adjacent OSCC and control tissue | Tissue | Parvimonas sp. was increased in OSCC samples | [23] |

| 20 tissue samples (10 OSCC samples and 10 non-tumor samples) | Tissue | Streptococcus sp. oral taxon 058, Streptococcus salivarius (S. salivarius), Streptococcus gordonii, Streptococcus parasanguinis, Peptostreptococcus stomatis, Gemella haemolysans, Gemella morbillorum, and Johnsonella ignava increased in abundance in tumor samples | [24] |

| 20 OSCC patients and 12 control tissues | Tissue | Exiguobacterium oxidotolerans, P. melaninogenica, Staphylococcus aureus, Veillonella parvula, and Micrococcus luteus detected in OSCC, not in controls | [31] |

| 10 OSCC patients and the same patient controls | Tissue | Fusobacterium naviforme present in OSCC samples, not in nontumorous tissue | [32] |

| 61 OSCC patients and 30 controls | Tissue | P. gingivalis and Fusobacterium increased in OSCC | [33] |

| 24 OSCC patients and 24 controls | OSCC tissue and brush biopsy controls | P. intermedia and P. gingivalis frequently detected in OSCC samples | [34] |

| Study Sample | Sample Type | Oral Bacteria and Main Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| EC, n = 39 Control, n = 51 | Saliva | Neisseria, Prevotella, and Veillonella potential new biomarkers for EC | [47] |

| ESCC, n = 32 Control, n = 35 | Saliva | At the phylum level, in ESCC patients, there were comparatively greater amounts of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes (25.3% vs. 24.9%) and lower amounts of Proteobacteria; at the genus level, ESCC patients exhibited comparatively greater amounts of Streptococcus spp. and Prevotella spp. than healthy controls | [44] |