P-Selectin Glycoprotein Ligand (PSGL)-1 Expression on CD4+ T Cells in Patients with HIV: Insights from an Observational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population, Inclusion, and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Clinical Samples and Isolation of PBMCs

2.4. HIV-1 Viral Load and CD4+ and CD8+ T Cell Counts

2.5. PSGL-1 Profiling, CD4+ T Cell–Platelet Aggregates, and CD4+ T Cell Signatures

2.6. Detection of Specific Markers of Inflammation Using ELISA

2.7. Collection of Clinical Data

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of Enrolled Participants

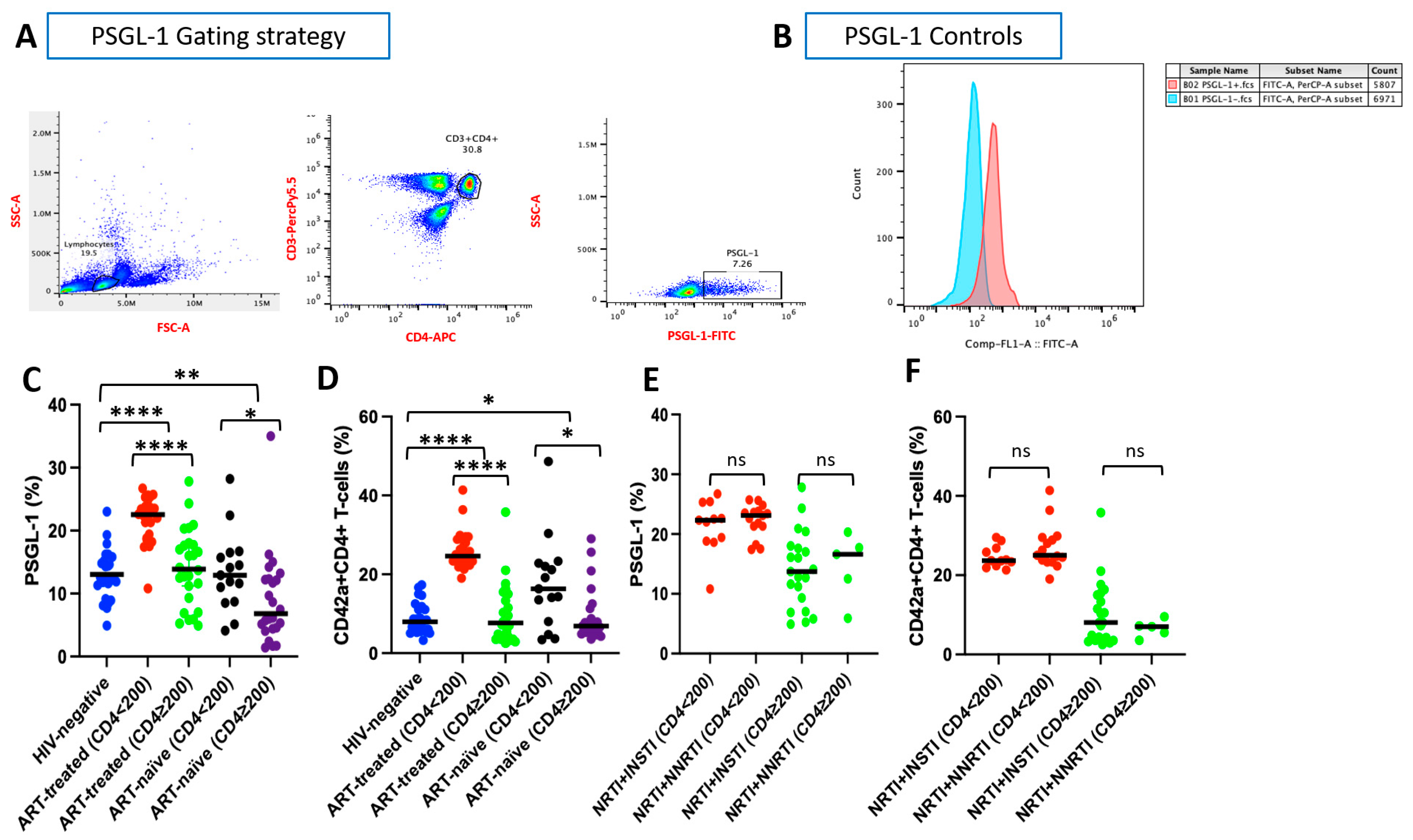

3.2. PSGL-1 Expression on CD4+ T Cells

3.3. CD4+ T Cell–Platelet Aggregates

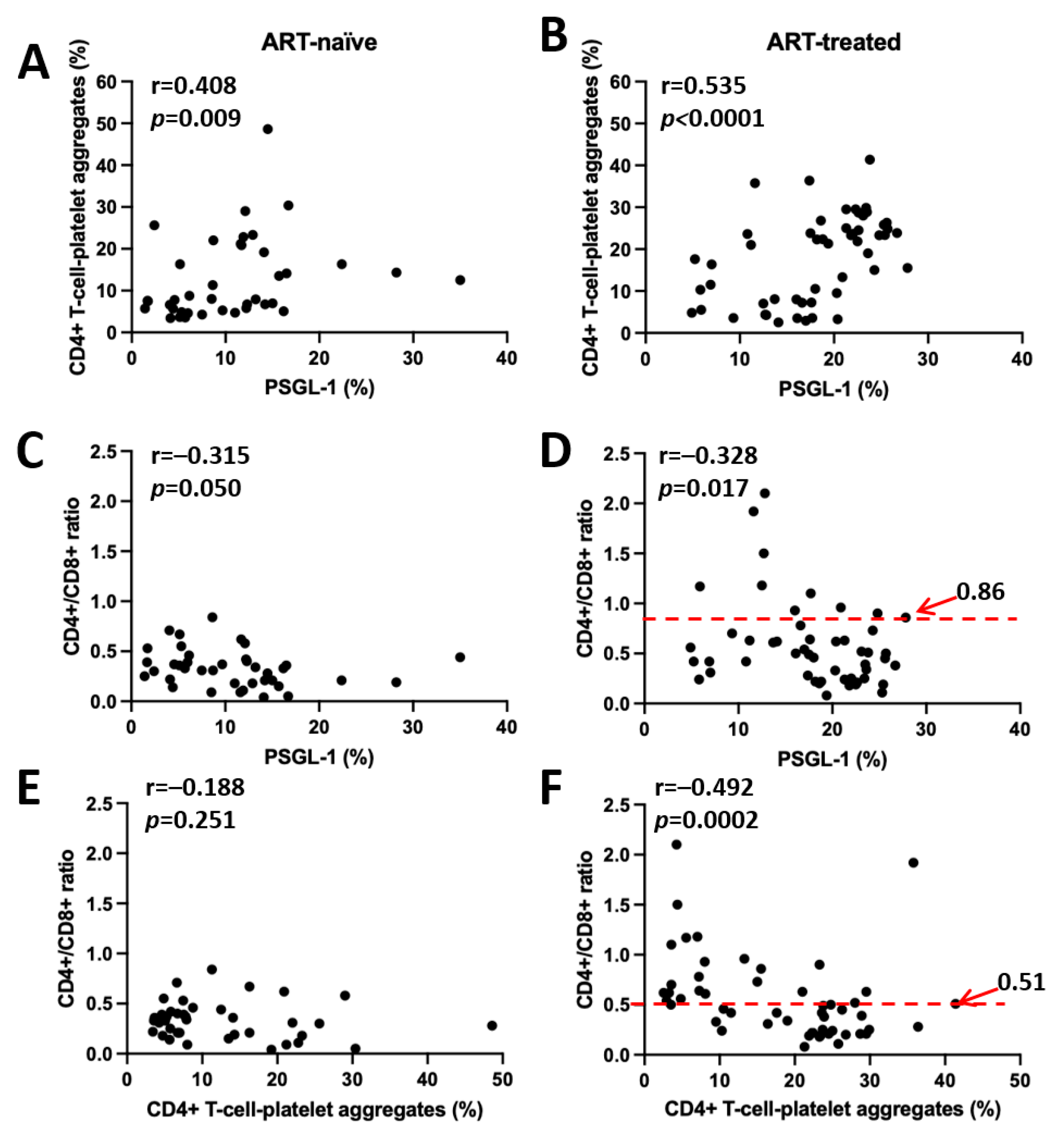

3.4. Correlation Between PSGL-1 Expression, CD4+ T Cell–Platelet Aggregates, and CD4+/CD8+ Ratio

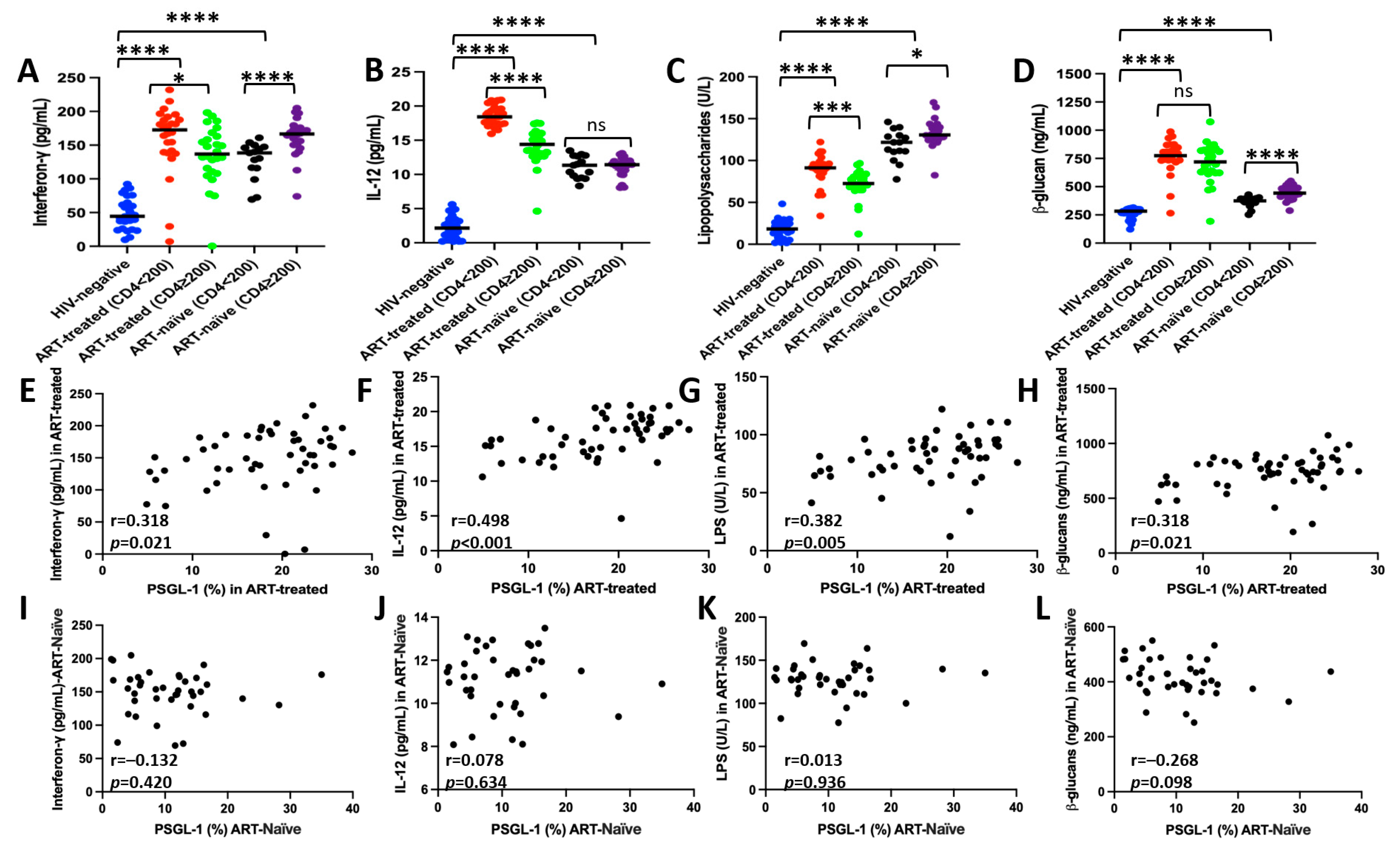

3.5. Correlation Between PSGL-1 Expression and Plasma Markers of Inflammation/Microbial Translocation

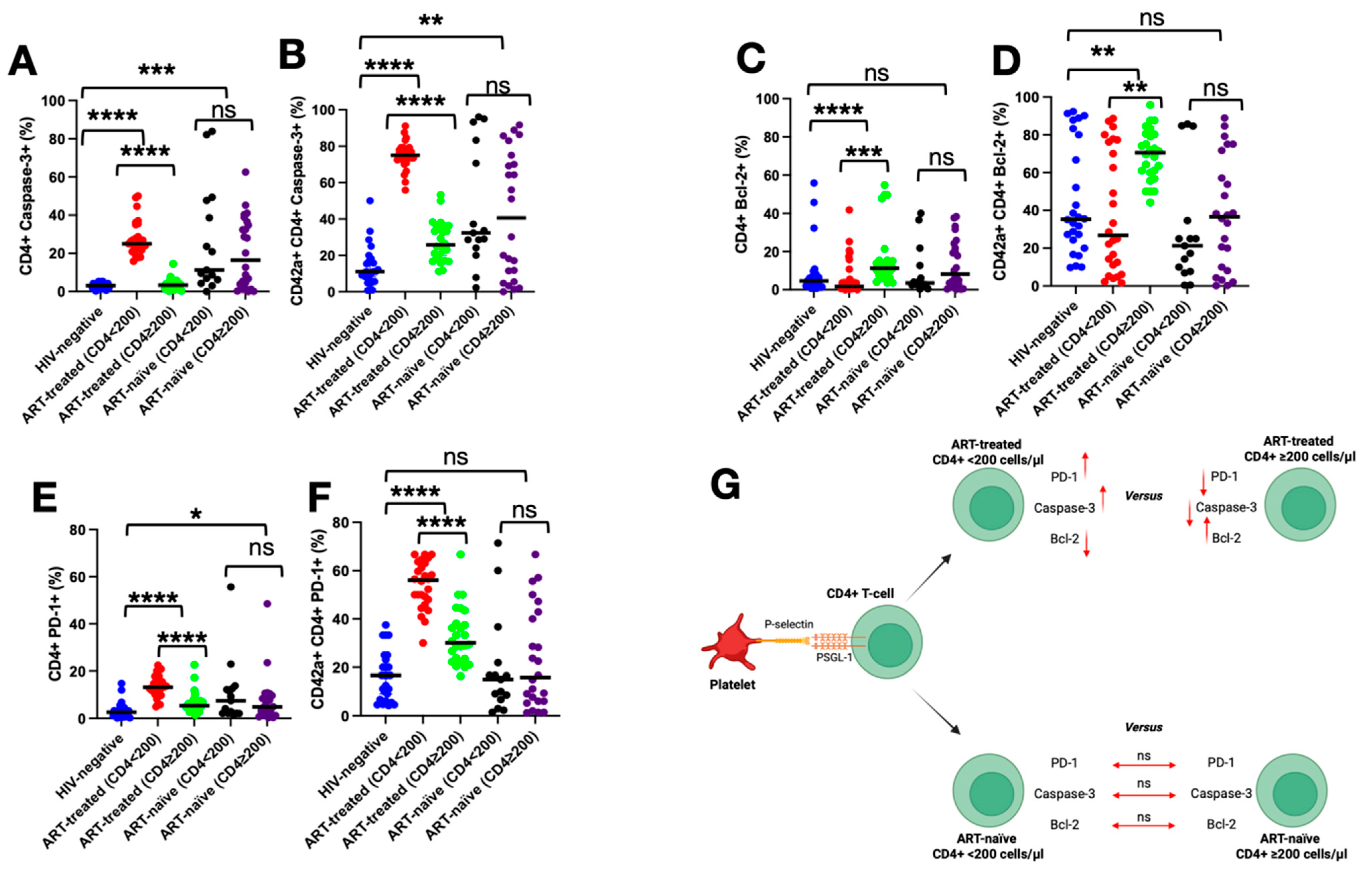

3.6. Impact of PSGL-1 on Markers of Death, Survival, and Exhaustion of CD4+ T Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tinoco, R.; Bradley, L.M. Targeting the PSGL-1 pathway for immune modulation. Immunotherapy 2017, 9, 785–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulki, L.; Noda, K.; Amini, R.; Schering, A.; Garland, R.C.; Nakao, S.; Nakazawa, T.; Hisatomi, T.; Thomas, K.L.; Masli, S.; et al. Surprising up-regulation of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) in endotoxin-induced uveitis. FASEB J. 2009, 23, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, W.S.; Tang, J.; Shaw, G.D.; Camphausen, R.T. Insights into the molecular basis of leukocyte tethering and rolling revealed by structures of P- and E-selectin bound to SLe(X) and PSGL-1. Cell 2000, 103, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Manivannan, A.; Jiang, H.R.; Liversidge, J.; Sharp, P.F.; Forrester, J.V.; Crane, I.J. Recruitment of IFN-gamma-producing (Th1-like) cells into the inflamed retina in vivo is preferentially regulated by P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1:P/E-selectin interactions. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 3215–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, A.; Liebers, U.; John, M.; Gerl, V.; Meyer, M.; Witt, C.; Wolff, G. P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) is up-regulated on leucocytes from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2005, 142, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, E.; Eytner, R.; Moll, T.; Steegmaier, M.; Campbell, M.A.; Ley, K.; Mossmann, H.; Vestweber, D. The P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 is important for recruitment of neutrophils into inflamed mouse peritoneum. Blood 1997, 90, 1934–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asaduzzaman, M.; Mihaescu, A.; Wang, Y.; Sato, T.; Thorlacius, H. P-selectin and P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 mediate rolling of activated CD8+ T cells in inflamed colonic venules. J. Investig. Med. 2009, 57, 765–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Fontecha, A.; Baumjohann, D.; Guarda, G.; Reboldi, A.; Hons, M.; Lanzavecchia, A.; Sallusto, F. CD40L+ CD4+ memory T cells migrate in a CD62P-dependent fashion into reactive lymph nodes and license dendritic cells for T cell priming. J. Exp. Med. 2008, 205, 2561–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley, K.; Kansas, G.S. Selectins in T-cell recruitment to non-lymphoid tissues and sites of inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 4, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, F.W.; Burns, A.R.; Smith, C.W.; Rumbaut, R.E. Platelets enhance neutrophil transendothelial migration via P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011, 300, H468–H475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M.; Joffraud, M.; Giraud, S.; Baïsse, B.; Bernimoulin, M.P.; Schapira, M.; Spertini, O. Regulation of PSGL-1 Interactions with L-selectin, P-selectin, and E-selectin: Role of human fucosyltransferase-IV and -VII. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 5378–5390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, M.; Zhou, Z.; Dabbagh, D.; Fu, C.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, T.; et al. Proteomic profiling of HIV-1 infection of human CD4+ T cells identifies PSGL-1 as an HIV restriction factor. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; He, S.; Waheed, A.A.; Dabbagh, D.; Zhou, Z.; Trinité, B.; Wang, Z.; Yu, J.; Wang, D.; Li, F.; et al. PSGL-1 restricts HIV-1 infectivity by blocking virus particle attachment to target cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 9537–9545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhang, S.; Diao, M.; Huang, S.; Li, S.; Tan, X. PSGL-1 inhibits HIV-1 infection by restricting actin dynamics and sequestering HIV envelope proteins. Cell Discov. 2020, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnie, J.; Persaud, A.T.; Thaya, L.; Liu, Q.; Miao, H.; Grabinsky, S.; Norouzi, V.; Lusso, P.; Tang, V.A.; Guzzo, C. P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1/CD162) is incorporated into clinical HIV-1 isolates and can mediate virus capture and subsequent transfer to permissive cells. Retrovirology 2022, 19, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, R.; Jones, L.D.; Qiu, X.; Thakar, J.; Maggirwar, S.B. Frontline Science: c-Myc regulates P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 expression in monocytes during HIV-1 infection. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2017, 102, 953–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.; Duan, Z.; Li, D.; Li, D.; Wang, Z.; Ren, L.; Shen, T.; Shao, Y. Higher levels of circulating monocyte-platelet aggregates are correlated with viremia and increased sCD163 levels in HIV-1 infection. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2015, 12, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakanjako, D.; Kiragga, A.N.; Musick, B.S.; Yiannoutsos, C.T.; Wools-Kaloustian, K.; Diero, L.; Oyaro, P.; Lugina, E.; Ssali, J.C.; Kambugu, A.; et al. Frequency and impact of suboptimal immune recovery on first-line antiretroviral therapy within the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS in East Africa. AIDS 2016, 30, 1913–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinoco, R.; Neubert, E.N.; Stairiker, C.J.; Henriquez, M.L.; Bradley, L.M. PSGL-1 Is a T Cell Intrinsic Inhibitor That Regulates Effector and Memory Differentiation and Responses During Viral Infection. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 677824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, S.M.; Lee, E.J.; Kotter, C.V.; Austin, G.L.; Dong, Z.; Hecht, D.K.; Gianella, S.; Siewe, B.; Smith, D.M.; Landay, A.L.; et al. An altered intestinal mucosal microbiome in HIV-1 infection is associated with mucosal and systemic immune activation and endotoxemia. Mucosal Immunol. 2014, 7, 983–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeRogatis, J.M.; Viramontes, K.M.; Neubert, E.N.; Tinoco, R. PSGL-1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibition for CD4+ T Cell Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 636238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babu, H.; Ambikan, A.T.; Gabriel, E.E.; Svensson Akusjärvi, S.; Palaniappan, A.N.; Sundaraj, V.; Mupanni, N.R.; Sperk, M.; Cheedarla, N.; Sridhar, R.; et al. Systemic Inflammation and the Increased Risk of Inflamm-Aging and Age-Associated Diseases in People Living With HIV on Long Term Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hileman, C.O.; Funderburg, N.T. Inflammation, Immune Activation, and Antiretroviral Therapy in HIV. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2017, 14, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.P.; Wu, F.Y.; Cui, C.; Liao, X.J.; Jiao, Y.M.; Zhang, C.; Song, J.W.; Fan, X.; Zhang, J.Y.; He, Q.; et al. Increased Platelet-CD4+ T Cell Aggregates Are Correlated With HIV-1 Permissiveness and CD4+ T Cell Loss. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 799124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, S.A.; Smith, M.; Hasley, R.B.; Stephany, D.; Harned, A.; Nagashima, K.; Abdullah, S.; Pittaluga, S.; Imamichi, T.; Qin, J.; et al. Activated platelet-T-cell conjugates in peripheral blood of patients with HIV infection: Coupling coagulation/inflammation and T cells. AIDS 2015, 29, 1297–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaongo, S.D.; Song, Y.; Chen, Y. P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 and cardiovascular diseases: From a general perspective to an HIV infection context. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1521158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, W.; Cooper, C.J.; Zhang, Z.; Brown, J.B.; Zhu, Y.; Issekutz, A.; Fuss, I.; Lee, H.O.; Kansas, G.S.; Barrett, T.A. P-selectin and P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 are major determinants for Th1 cell recruitment to nonlymphoid effector sites in the intestinal lamina propria. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 198, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaongo, S.D.; Chen, Y. PSGL-1, a Strategic Biomarker for Pathological Conditions in HIV Infection: A Hypothesis Review. Viruses 2023, 15, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévesque, J.P.; Zannettino, A.C.; Pudney, M.; Niutta, S.; Haylock, D.N.; Snapp, K.R.; Kansas, G.S.; Berndt, M.C.; Simmons, P.J. PSGL-1-mediated adhesion of human hematopoietic progenitors to P-selectin results in suppression of hematopoiesis. Immunity 1999, 11, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hope, J.L.; Otero, D.C.; Bae, E.A.; Stairiker, C.J.; Palete, A.B.; Faso, H.A.; Lin, M.; Henriquez, M.L.; Roy, S.; Seo, H.; et al. PSGL-1 attenuates early TCR signaling to suppress CD8+ T cell progenitor differentiation and elicit terminal CD8+ T cell exhaustion. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.; Huang, C.C.; Chien, C.L.; Jeng, C.J.; Su, H.T.; Chiang, E.; Liu, M.R.; Wu, C.H.; Chang, C.N.; Lin, R.H. Cross-linking of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 induces death of activated T cells. Blood 2004, 104, 3233–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susin, S.A.; Zamzami, N.; Castedo, M.; Hirsch, T.; Marchetti, P.; Macho, A.; Daugas, E.; Geuskens, M.; Kroemer, G. Bcl-2 inhibits the mitochondrial release of an apoptogenic protease. J. Exp. Med. 1996, 184, 1331–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.H.; Nussbaum, C.; Grewal, P.K.; Marth, J.D.; Sperandio, M. Coordinated roles of ST3Gal-VI and ST3Gal-IV sialyltransferases in the synthesis of selectin ligands. Blood 2012, 120, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PLWH ART-Treated | p-Value | PLWH ART-Naïve | p-Value | HIV-Negative (n = 26) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+ < 200 (n = 26) | CD4+ ≥ 200 (n = 26) | CD4+ < 200 (n = 15) | CD4+ ≥ 200 (n = 24) | ||||

| Age (years) [Median (IQR)] | 49.5 (13) | 47 (14) | 0.213 | 44 (23) | 46 (15) | 0.881 | 45 (3) |

| Sex | 1 | 0.95 | |||||

| Male [n(%)] | 21 (80.8) | 21 (80.8) | 12 (80) | 19 (79.16) | 21 (80.8) | ||

| Female [n(%)] | 5 (19.2) | 5 (19.2) | 3 (20) | 5 (20.84) | 5 (19.2) | ||

| CD4+ count (cells/µL) [Median (IQR)] | 157 (52) | 482 (303) | <0.001 | 141 (77) | 407 (139.5) | <0.001 | N/A |

| CD8+ count (cells/µL) [Median (IQR)] | 458.5 (217) | 790 (316) | <0.001 | 761 (714) | 929.5 (772.5) | 0.245 | N/A |

| CD4+/CD8+ ratio [Median (IQR)] | 0.25 (0.24) | 0.64 (0.46) | <0.001 | 0.18 (0.19) | 0.39 (0.22) | <0.001 | N/A |

| Nadir CD4+ count (cells/µL) [Median (IQR)] | 37.5 (66) | 230 (201) | <0.001 | N/A | N/A | - | N/A |

| HIV VL [Median RNA copies/mL (IQR)] | N/A | N/A | - | 208,000 (306,200) | 59,800 (293,550) | 0.074 | N/A |

| ART duration (years) [Median (IQR)] | 5 (3) | 5 (4) | 0.788 | N/A | N/A | - | N/A |

| Current ART regimens | 0.004 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| NRTI + INSTI [n(%)] | 11 (42.3%) | 21 (80.8) | |||||

| NRTI + NNRTI [n(%)] | 15 (57.7%) | 5 (19.2) | |||||

| Duration of current ART regimens (years) [Median (IQR)] | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||||

| NRTI + INSTI | 3 (4) | 2 (1) | 0.441 | ||||

| NRTI + NNRTI | 5 (3) | 4 (4.5) | 0.355 | ||||

| Number of ART regimens received [Median (IQR)] | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 0.328 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zaongo, S.D.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Tang, S.; Harypursat, V.; Chen, Y. P-Selectin Glycoprotein Ligand (PSGL)-1 Expression on CD4+ T Cells in Patients with HIV: Insights from an Observational Study. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1232. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121232

Zaongo SD, Wan Y, Zhang L, Tang S, Harypursat V, Chen Y. P-Selectin Glycoprotein Ligand (PSGL)-1 Expression on CD4+ T Cells in Patients with HIV: Insights from an Observational Study. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1232. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121232

Chicago/Turabian StyleZaongo, Silvere D., Yan Wan, Lu Zhang, Shengquan Tang, Vijay Harypursat, and Yaokai Chen. 2025. "P-Selectin Glycoprotein Ligand (PSGL)-1 Expression on CD4+ T Cells in Patients with HIV: Insights from an Observational Study" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1232. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121232

APA StyleZaongo, S. D., Wan, Y., Zhang, L., Tang, S., Harypursat, V., & Chen, Y. (2025). P-Selectin Glycoprotein Ligand (PSGL)-1 Expression on CD4+ T Cells in Patients with HIV: Insights from an Observational Study. Pathogens, 14(12), 1232. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121232