Prevalence of Borreliaceae Spirochetes in Ticks Removed from Humans in Poland During 2018–2022

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

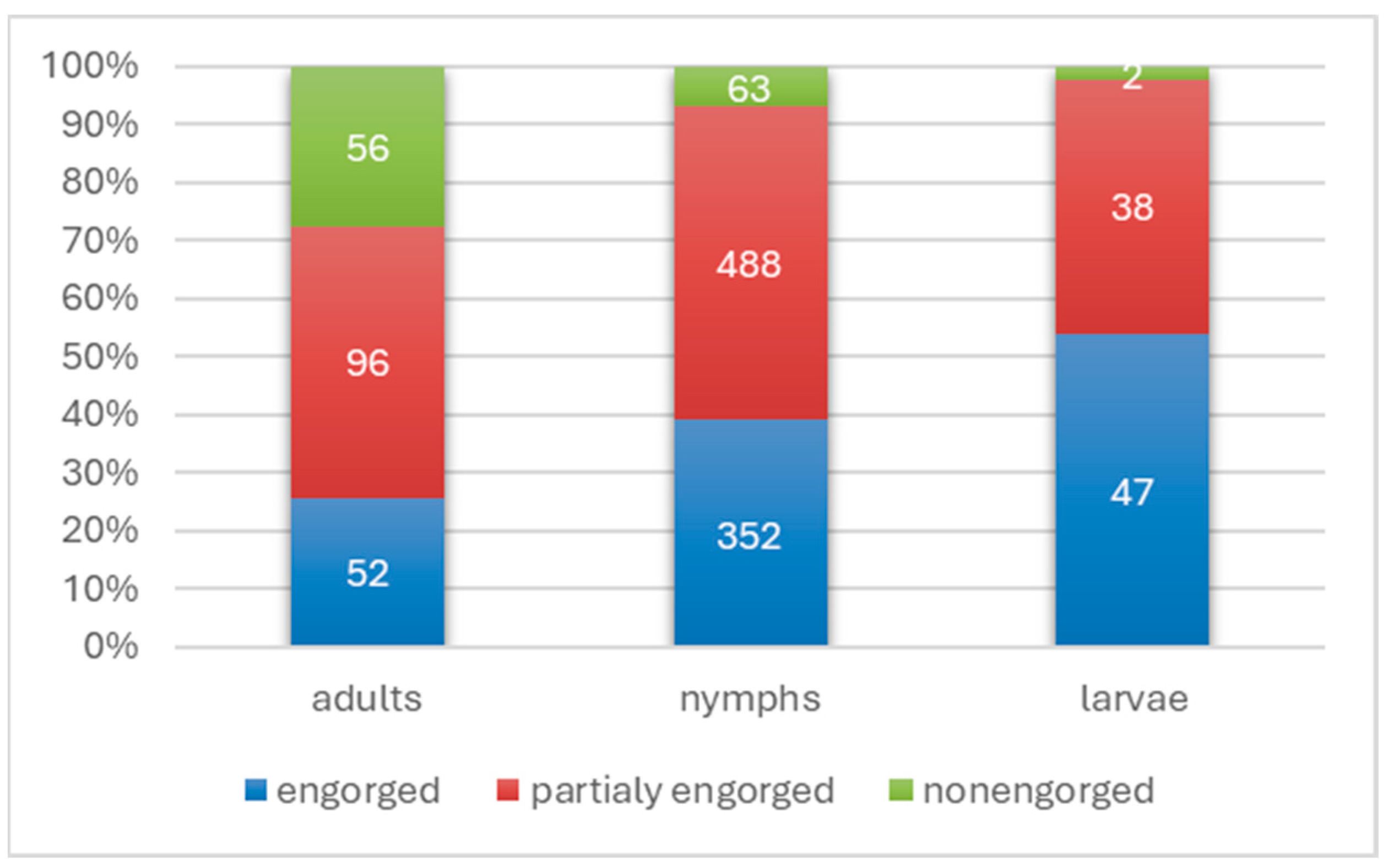

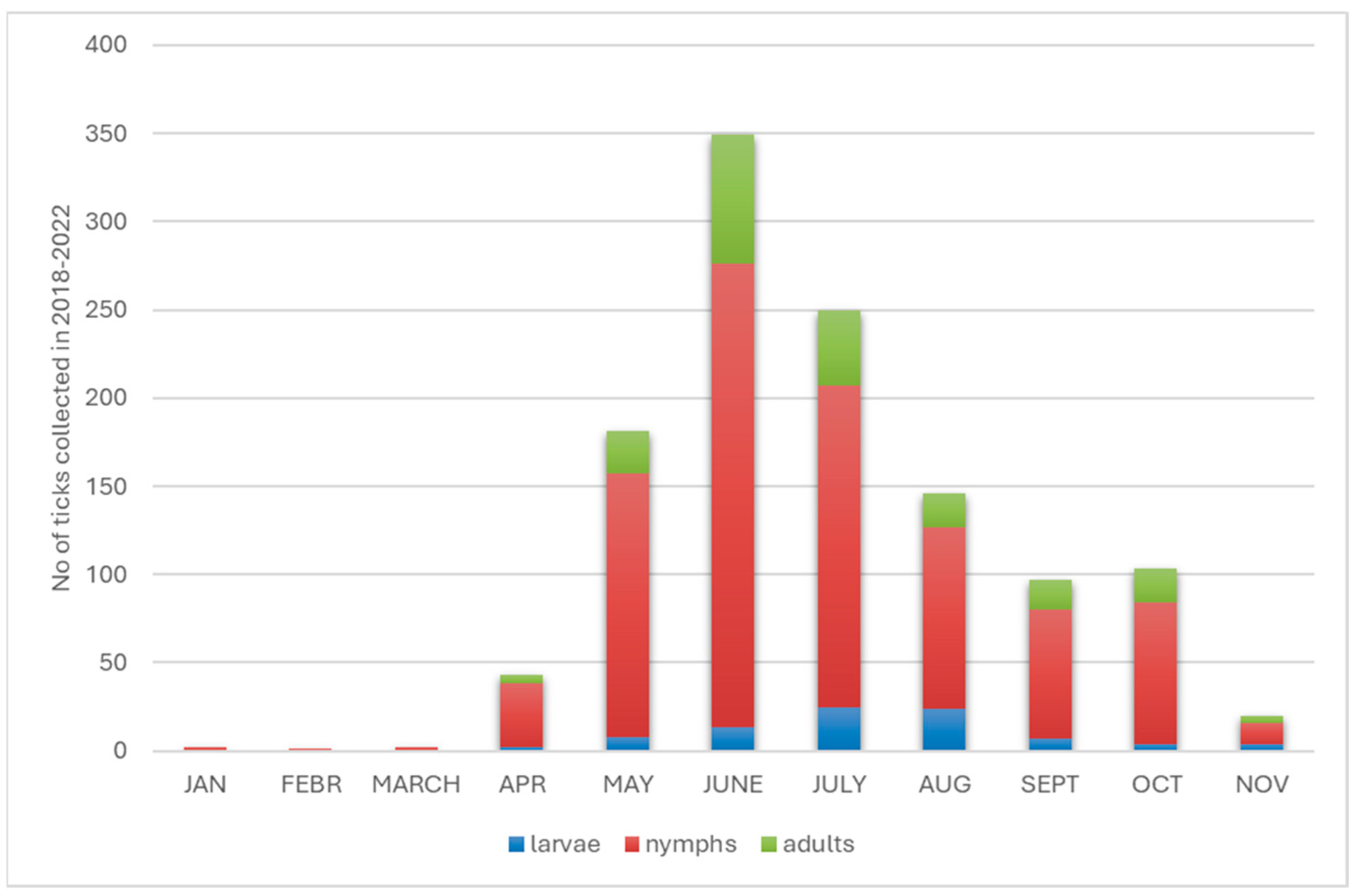

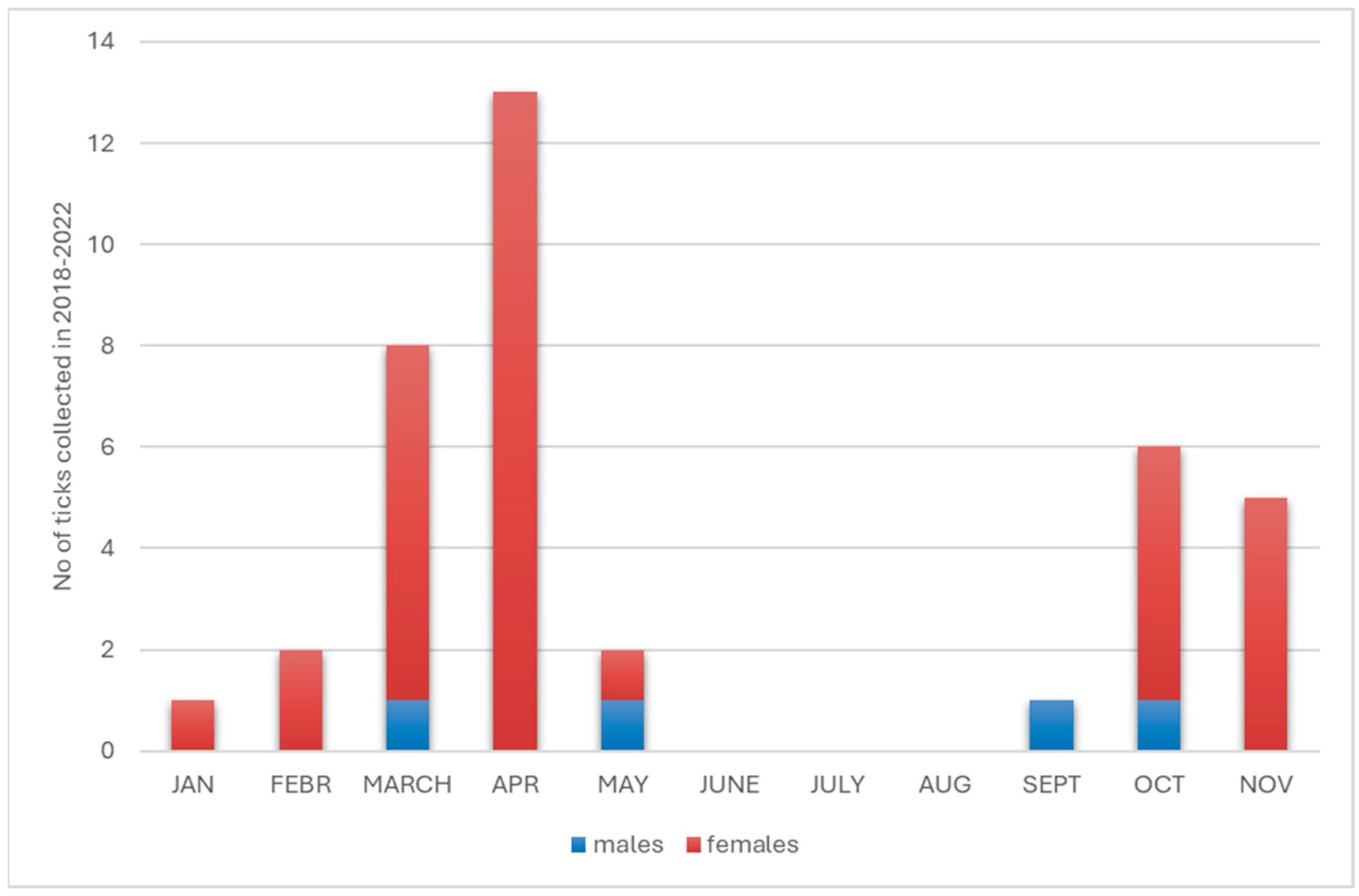

3.1. Identification of Tick Species Attacking Humans

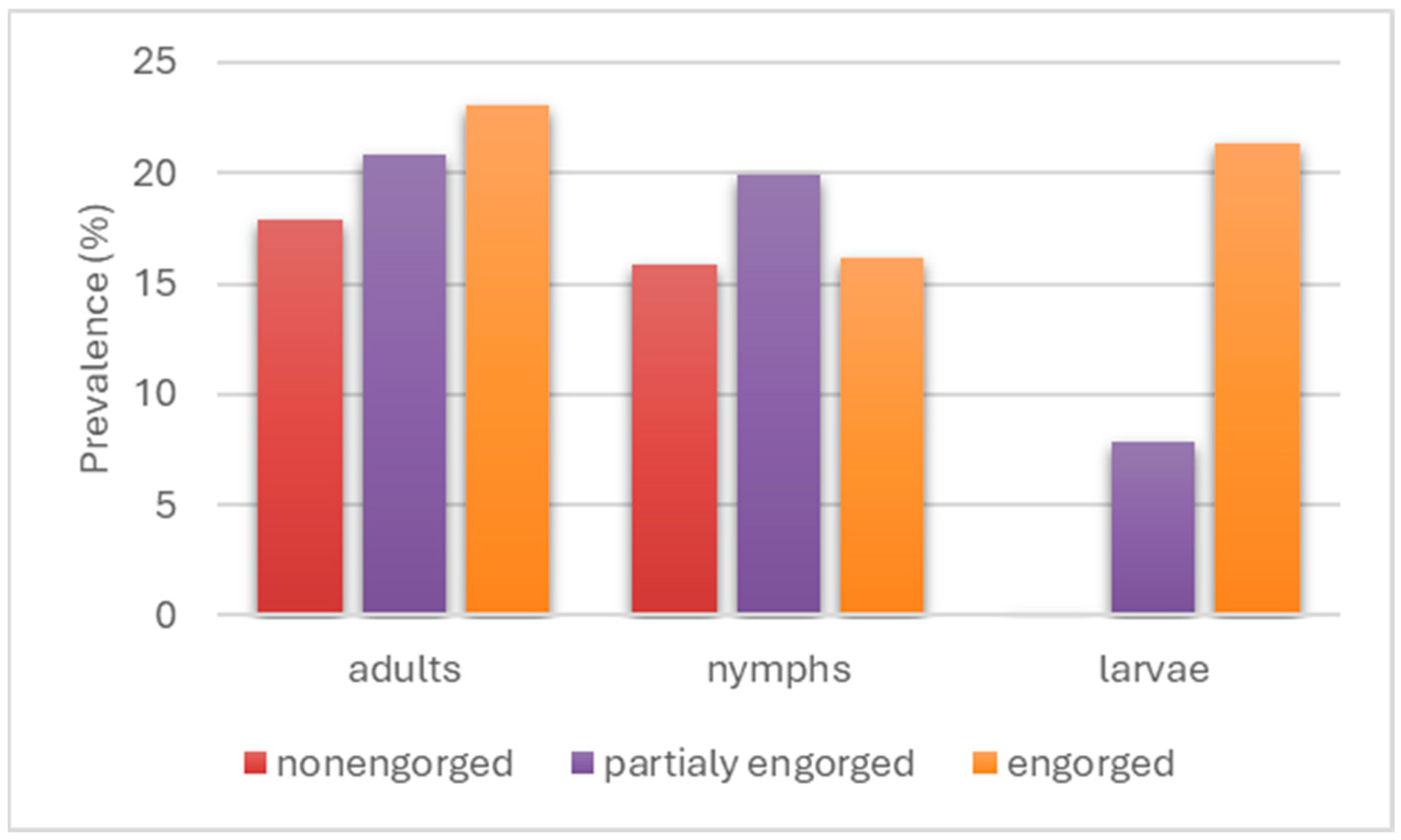

3.2. Prevalence of Borreliaceae Spirochetes in I. ricinus and D. reticulatus Ticks

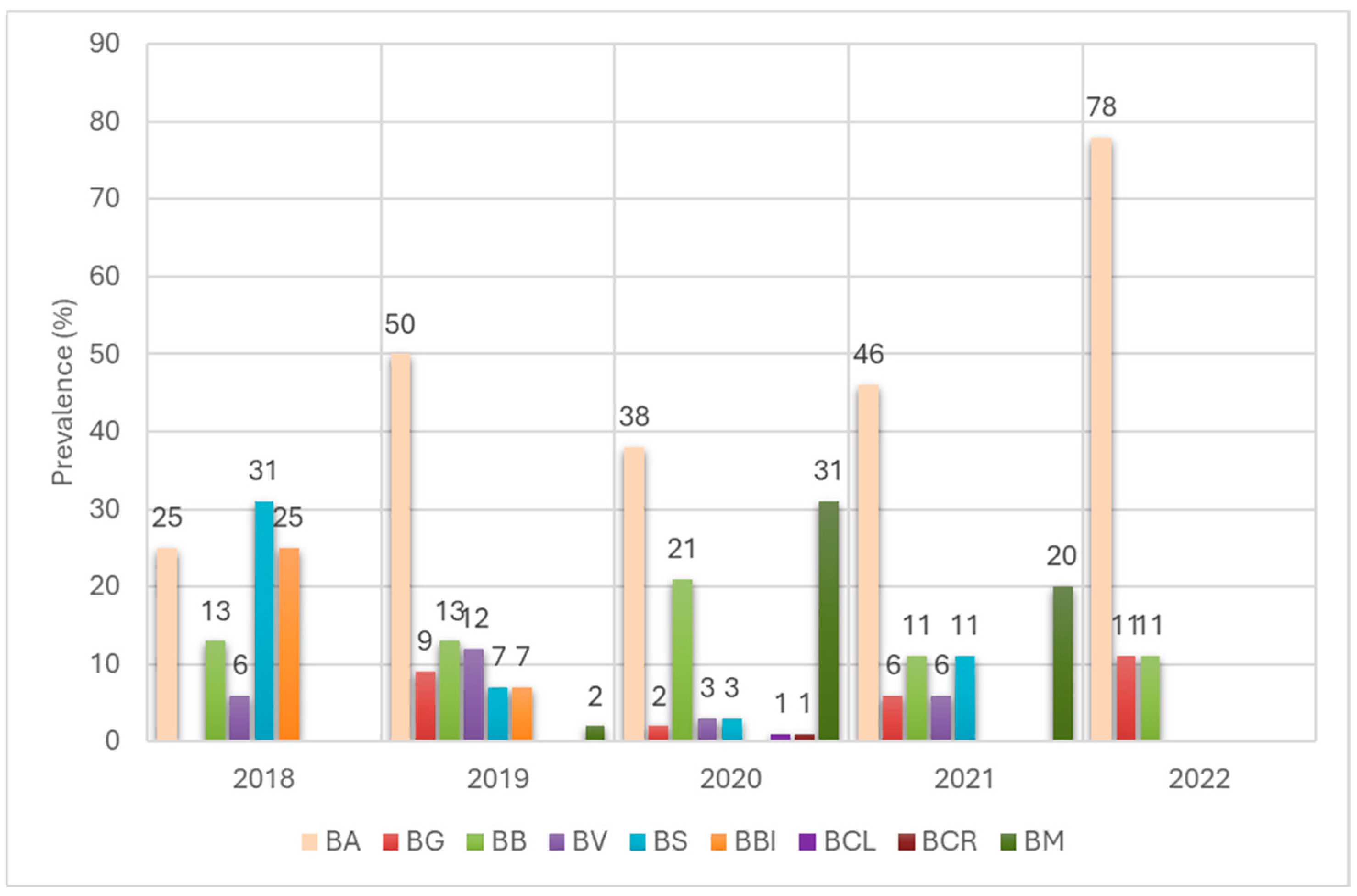

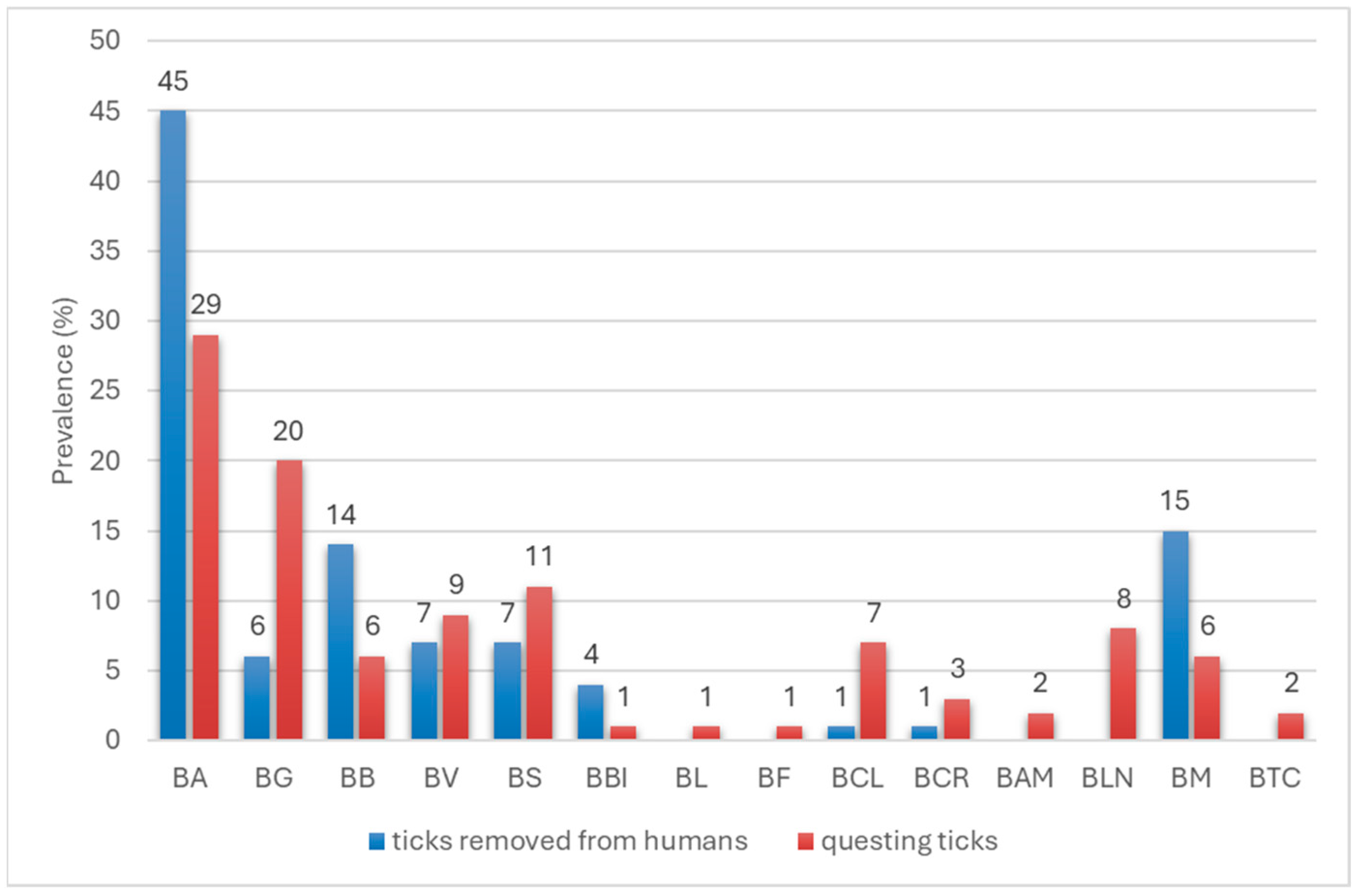

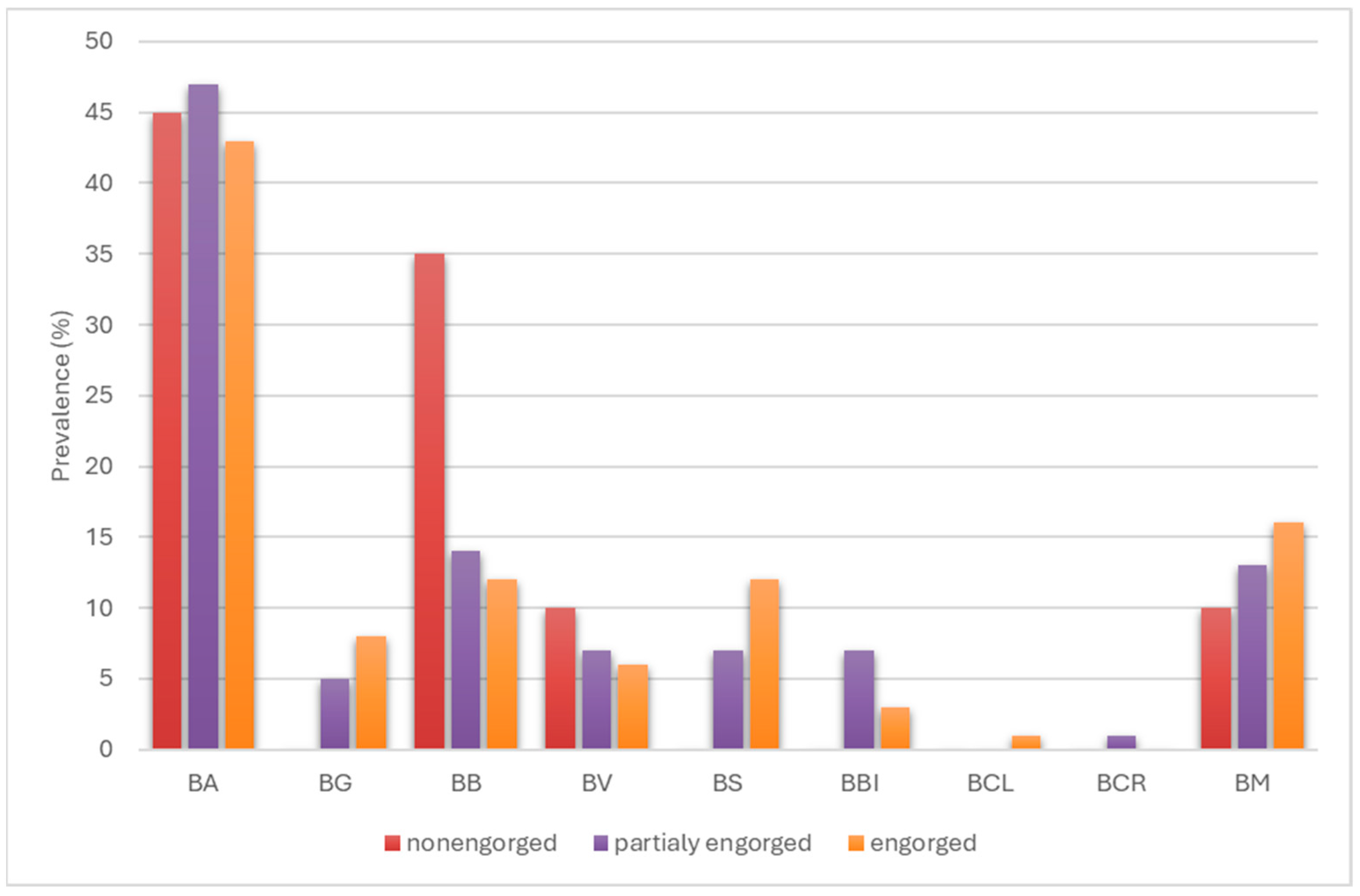

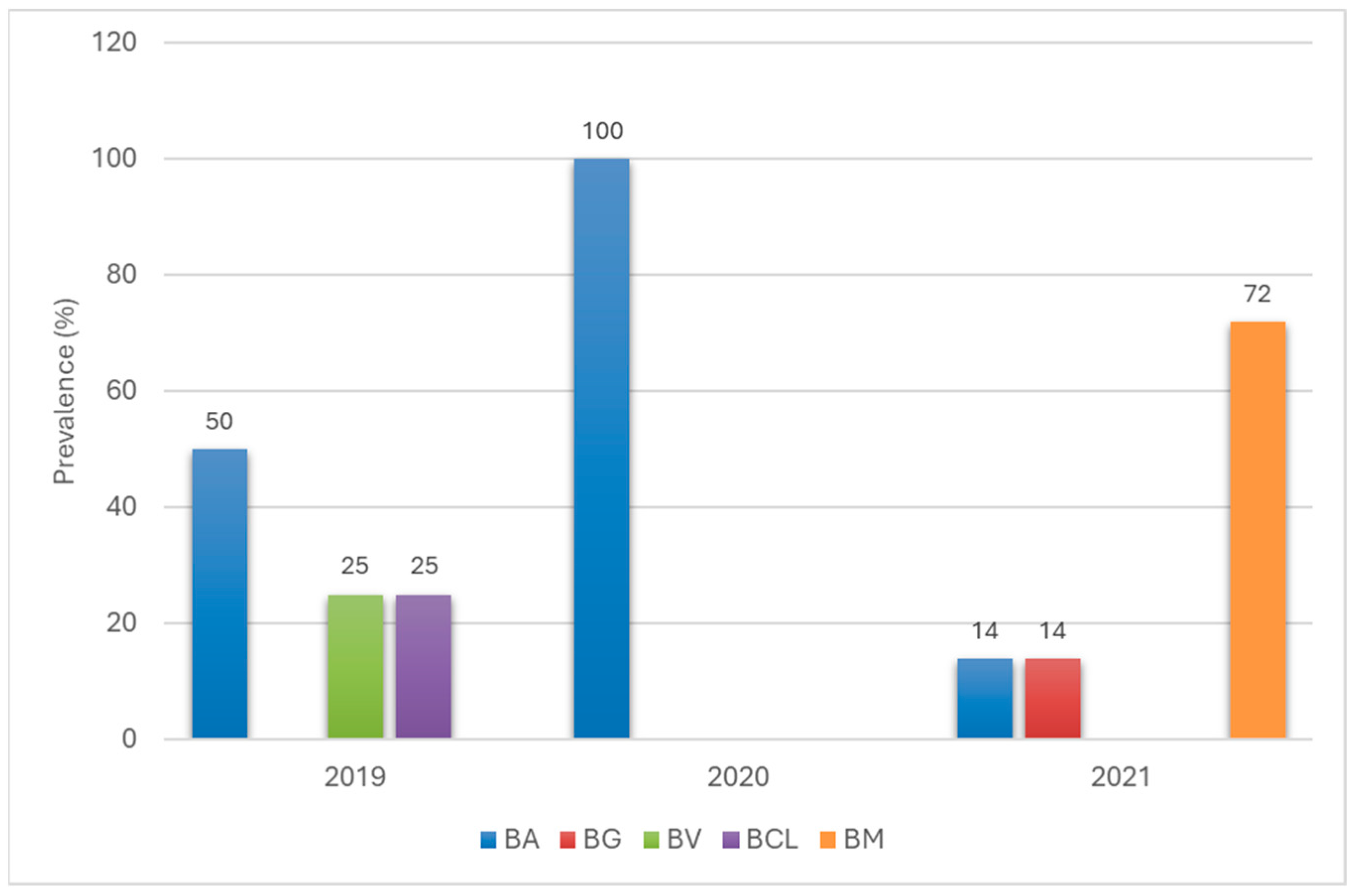

3.3. Identification of Borreliella and Borrelia Species in I. ricinus and D. reticulatus Ticks

3.4. Genetic Variability of Borreliaceae Detected in Ticks Removed from Humans

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burn, L.; Vyse, A.; Pilz, A.; Tran, T.M.P.; Fletcher, M.A.; Angulo, F.J.; Gessner, B.D.; Moïsi, J.C.; Stark, J.H. Incidence of Lyme Borreliosis in Europe: A Systematic Review (2005–2020). Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2023, 23, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Public Health-National Institute of Hygiene. Epidemiological Reports. Available online: https://www.pzh.gov.pl/serwisy-tematyczne/meldunki-epidemiologiczne/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Adeolu, M.; Gupta, R.S. A phylogenomic and molecular marker based proposal for the division of the genus Borrelia into two genera: The emended genus Borrelia containing only the members of the relapsing fever Borrelia, and the genus Borreliella gen. nov. containing the members of the Lyme disease Borrelia (Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex). Antonie Leeuwenhoek 2014, 105, 1049–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arahal, D.R.; Bull, C.T.; Busse, H.; Christensen, H.; Chuvochina, M.; Dedysh, S.N.; Fournier, P.; Konstantinidis, K.T.; Parker, C.T.; Rossello-Mora, R.; et al. Judicial Opinions 123–127. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2022, 72, 005708, [N.B.: The request of Margos et al. (2020) to place the genus name ‘Borreliella’ and the names of all of its species on the list of nomina rejicienda is denied.]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socarras, K.M.; Marino, M.C.; Earl, J.P.; Ehrlich, R.L.; Cramer, N.A.; Mell, J.C.; Sen, B.; Ahmed, A.; Marconi, R.T.; Ehrlich, G.D. Characterization of the family-level Borreliaceae pan-genome and development of an episomal typing protocol. mBio 2025, 16, e0094325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margos, G.; Stevenson, B.; Birtles, R.; Gofton, A.; Talagrand-Reboul, E.; Goeker, M.; Fingerle, V. Proposing a subgenus Borreliella. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2025, 16, 102536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norte, A.C.; Ramos, J.A.; Gern, L.; Núncio, M.S.; Lopes de Carvalho, I. Birds as reservoirs for Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. in Western Europe: Circulation of B. turdi and other genospecies in bird-tick cycles in Portugal. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 15, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanek, G.; Strle, F. Lyme borreliosis–from tick bite to diagnosis and treatment. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 42, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wodecka, B.; Kolomiiets, V. Genetic Diversity of Borreliaceae Species Detected in Natural Populations of Ixodes ricinus Ticks in Northern Poland. Life 2023, 13, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamo, S.; Trevisan, G.; Ruscio, M.; Bonin, S. Borrelial Diseases Across Eurasia. Biology 2025, 14, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fesler, M.C.; Shah, J.S.; Middelveen, M.J.; Du Cruz, I.; Burrascano, J.J.; Stricker, R.B. Lyme Disease: Diversity of Borrelia species in California and Mexico detected using a novel immunoblot assay. Healthcare 2020, 8, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodecka, B.; Michalik, J.; Grochowalska, R. Red Foxes (Vulpes vulpes) Are Exposed to High Diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi Sensu Lato Species Infecting Fox-Derived Ixodes Ticks in West-Central Poland. Pathogens 2022, 11, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gern, L. Life cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato and transmission to humans. Curr. Probl. Dermatol. 2009, 37, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strnad, M.; Hönig, V.; Ružek, D.; Grubhoffer, L.; Rego, R.O.M. Europe-wide meta-analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato prevalence in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e00609-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansford, K.M.; Wheeler, B.W.; Tschirren, B.; Medlock, J.M. Questing Ixodes ricinus ticks and Borrelia spp. in urban green space across Europe: A review. Zoonoses Public Health 2022, 69, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobudic, S.; Burgmann, H.; Stanek, G.; Winkler, S.; Schötta, A.M.; Obermüller, M.; Markowicz, M.; Lagler, H. Human Borrelia miyamotoi infection, Austria. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 2201–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, T.; Gotoh, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Kawabata, H.; Takano, A. Antigenic variation is caused by long plasmid segment conversion in a hard tick-borne relapsing fever Borrelia miyamotoi. PLoS Pathog. 2025, 21, e1013514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiak, K.; Szczotko, M.; Dmitryjuk, M. Borrelia miyamotoi—An Emerging Human Tick-Borne Pathogen in Europe. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoornstra, D.; Stukolova, O.A.; van Eck, J.A.; Sokolova, M.I.; Platonov, A.E.; Hofhuis, A.; Vos, E.R.A.; Reimerink, J.H.; van den Berg, O.E.; van den Wijngaard, C.C.; et al. Exposure, infection and disease with the tick-borne pathogen Borrelia miyamotoi in the Netherlands and Sweden, 2007–2019. J. Infect. 2024, 89, 106326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotté, V.; Bonnet, S.; Cote, M.; Vayssier-Taussat, M. Prevalence of five pathogenic agents in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks from western France. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010, 10, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heylen, D.; Fonville, M.; van Leeuwen, A.D.; Stroo, A.; Duisterwinke, M.; van Wieren, S.; Diuk-Wasser, M.; de Bruin, A.; Sprong, H. Pathogen communities of songbird-derived ticks in Europe’s low countries. Parasites Vectors 2017, 10, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunaj, J.; Drewnowska, J.; Moniuszko-Malinowska, A.; Swięcicka, I.; Pancewicz, S. First metagenomic report of Borrelia americana and Borrelia carolinensis in Poland—A preliminary study. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2021, 28, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sormunen, J.J.; Kulha, N.; Klemola, T.; Mäkelä, S.; Vesilahti, E.M.; Vesterinen, E.J. Enhanced threat of tick-borne infections within cities? Assessing public health risks due to ticks in urban green spaces in Helsinki, Finland. Zoonoses Public Health 2020, 67, 823–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cull, B.; Pietzsch, M.E.; Gillingham, E.L.; McGinley, L.; Medlock, J.M.; Hansford, K.M. Seasonality and anatomical location of human tick bites in the United Kingdom. Zoonoses Public Health 2020, 67, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas-Torres, F. Climate change, biodiversity, ticks and tick-borne diseases: The butterfly effect. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2015, 4, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmsson, P.; Lindblom, P.; Fryland, L.; Ernerudh, J.; Forsberg, P.; Lindgren, P.E. Prevalence, diversity, and load of Borrelia species in ticks that have fed on humans in regions of Sweden and Åland Islands, Finland with different Lyme borreliosis incidences. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briciu, V.T.; Meyer, F.; Sebah, D.; Ţăţulescu, D.F.; Coroiu, G.; Lupşe, M.; Carstina, D.; Mihalca, A.D.; Hizo-Teufel, C.; Klier, C.; et al. Real-time PCR based identification of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato species in ticks collected from humans in Romania. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2014, 5, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waindok, P.; Schicht, S.; Fingerle, V.; Strube, C. Lyme borreliae prevalence and genospecies distribution in ticks removed from humans. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2017, 8, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.O.; Marga, G.; Banu, T.; Dobler, G.; Chitimia-Dobler, L. Tick-borne pathogens in tick species infesting humans in Sibiu County, central Romania. Parasitol. Res. 2018, 117, 1591–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springer, A.; Raulf, M.-K.; Fingerle, V.; Strube, C. Borrelia prevalence and species distribution in ticks removed from humans in Germany, 2013–2017. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2020, 11, 101363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banovic, P.; Díaz-Sanchez, A.A.; Galon, C.; Simin, V.; Mijatovic, D.; Obregon, D.; Moutailler, S.; Cabezas-Cruz, A. Humans infested with Ixodes ricinus are exposed to a diverse array of tick-borne pathogens in Serbia. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2021, 12, 101609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowicz, M.; Schötta, A.M.; Höss, D.; Kundi, M.; Schray, C.; Stockinger, H.; Stanek, G. Infections with Tickborne Pathogens after Tick Bite, Austria, 2015–2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 1048–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jumpertz, M.; Sevestre, J.; Luciani, L.; Houhamdi, L.; Fournier, P.E.; Parola, P. Bacterial Agents Detected in 418 Ticks Removed from Humans During 2014–2021, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippe, C.; Geebelen, L.; Hermy, M.R.G.; Dufrasne, F.E.; Tersago, K.; Pellegrino, A.; Fonville, M.; Sprong, H.; Mori, M.; Lernout, T. The prevalence of pathogens in ticks collected from humans in Belgium, 2021, versus 2017. Parasites Vectors 2024, 17, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lernout, T.; De Regge, N.; Tersago, K.; Fonville, M.; Suin, V.; Sprong, H. Prevalence of pathogens in ticks collected from humans through citizen science in Belgium. Parasites Vectors 2019, 12, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawełczyk, A.; Bednarska, M.; Hamera, A.; Religa, E.; Poryszewska, M.; Mierzejewska, E.J.; Welc-Falęciak, R. Long-term study of Borrelia and Babesia prevalence and co-infection in Ixodes ricinus and Dermacentor recticulatus ticks removed from humans in Poland, 2016–2019. Parasites Vectors 2021, 14, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grochowska, A.; Dunaj-Małyszko, J.; Pancewicz, S.; Czupryna, P.; Milewski, R.; Majewski, P.; Moniuszko-Malinowska, A. Prevalence of Tick-Borne Pathogens in Questing Ixodes ricinus and Dermacentor reticulatus Ticks Collected from Recreational Areas in Northeastern Poland with Analysis of Environmental Factors. Pathogens 2022, 11, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiak, K.; Szymańska, H.; Dmitryjuk, M.; Dzika, E. Abundance of Ixodes ricinus Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) and the Diversity of Borrelia Species in Northeastern Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciebiera, O.; Grochowalska, R.; Łopińska, A.; Zduniak, P.; Strzała, T.; Jerzak, L. Ticks and spirochetes of the genus Borrelia in urban areas of Central-Western Poland. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2024, 93, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalik, J.; Wodecka, B.; Liberska, J.; Dabert, M.; Postawa, T.; Piksa, K.; Stańczak, J. Diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato species in Ixodes ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) associated with cave-dwelling bats from Poland and Romania. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2020, 11, 101300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, M.M.; Kubiak, K.; Szczotko, M.; Chajęcka, M.; Dmitryjuk, M. Molecular detection of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in ticks collected from dogs in urban areas of North-Eastern Poland. Pathogens 2020, 9, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, M.M.; Kubiak, K.; Szczotko, M.; Dmitryjuk, M. Tick-Borne Pathogens in Ticks Collected from Wild Ungulates in North-Eastern Poland. Pathogens 2021, 10, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyczko, D.; Krysmann, A.; Kolanek, A.; Borczyk, B.; Kiewra, D. Bacterial pathogens in Ixodes ricinus collected from lizards Lacerta agilis and Zootoca vivipara in urban areas of Wrocław, SW Poland-preliminary study. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2024, 93, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulisz, J.; Zając, Z.; Foucault-Simonin, A.; Woźniak, A.; Filipiuk, M.; Kloskowski, J.; Rudolf, R.; Corduneanu, A.; Bartosik, K.; Moutailler, S.; et al. Wide spectrum of tick-borne pathogens in juvenile Ixodes ricinus collected from autumn-migrating birds in the Vistula River Valley, Poland. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolomiiets, V.; Wodecka, B. Molecular Identification of Borreliella Species in Ixodes hexagonus Ticks Infesting Hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus and E. roumanicus) in North-Western Poland. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 26, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siuda, K. Ticks (Acari: Ixodida) of Poland. Part II: Taxonomy and Distribution; Polskie Towarzystwo Parazytologiczne: Warsaw, Poland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wodecka, B. FlaB gene as a molecular marker for distinct identification of Borrelia species in environmental samples by the PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism method. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 7088–7092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodecka, B.; Michalik, J.; Lane, R.S.; Nowak-Chmura, M.; Wierzbicka, A. Differential associations of Borrelia species with European badgers (Meles meles) and raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) in western Poland. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2016, 7, 1010–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbrink, A.; Brugger, K.; Margos, G.; Kraiczy, P.; Klimpel, S. The evolving story of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato transmission in Europe. Parasitol. Res. 2022, 121, 781–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornok, S.; Takács, N.; Nagy, G.; Lakos, A. Retrospective molecular analyses of hard ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) from patients admitted to the Centre for Tick-Borne Diseases in Central Europe, Hungary (1999–2021), in relation to clinical symptoms. Parasites Vectors 2025, 18, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koczwarska, J.; Polaczyk, J.; Wieczorek, W.; Zdzienicka, O.; Żórańska, J.; Pawełczyk, A.; Welc-Falęciak, R. Coexistence of Borrelia spp. with different tick-borne pathogens in Ixodes ricinus ticks removed from humans in Poland. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mierzejewska, E.J.; Estrada-Peña, A.; Bajer, A. Spread of Dermacentor reticulatus is associated with the loss of forest area. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2017, 72, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zając, Z.; Obregon, D.; Foucault-Simonin, A.; Wu-Chuang, A.; Moutailler, S.; Galon, C.; Kulisz, J.; Woźniak, A.; Bartosik, K.; Cabezas-Cruz, A. Disparate dynamics of pathogen prevalence in Ixodes ricinus and Dermacentor reticulatus ticks occurring sympatrically in diverse habitats. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmár, Z.; Dumitrache, M.O.; D’Amico, G.; Matei, I.A.; Ionică, A.M.; Gherman, C.M.; Lupșe, M.; Mihalca, A.D. Multiple tick-borne pathogens in Ixodes ricinus ticks collected from humans in Romania. Pathogens 2020, 9, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, D.; Debski, A.; Hubalek, Z.; Matuschka, F.R. Absence of Lyme disease spirochetes in larval Ixodes ricinus ticks. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012, 12, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuner, N.E.; Hojgaard, A.; Replogle, A.J.; Boegler, K.A.; Eisen, L. Transmission of the relapsing fever spirochete, Borrelia miyamotoi, by single transovarially-infected larval Ixodes scapularis ticks. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2018, 9, 1464–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, L.; Da Rold, G.; Beltrame, A.; Formenti, F.; Mazzi, C.; Ragusa, A.; Scarso, S.; Drigo, I.; Degani, M.; Piubelli, C.; et al. Surveillance of Tick-Borne Pathogens in Ticks from Humans in the Province of Verona, Italy (2018–2022): A Prospective Study. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusňáková Tarageľová, V.; Derdáková, M.; Selyemová, D.; Chvostáč, M.; Mangová, B.; Didyk, Y.M.; Koči, J.; Kolenčík, S.; Víchová, B.; Petko, B.; et al. Two decades of research on Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks in Slovakia. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1496925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coipan, E.C.; Jahfari, S.; Fonville, M.; Maassen, C.B.; van der Giessen, J.; Takken, W.; Takumi, K.; Sprong, H. Spatiotemporal dynamics of emerging pathogens in questing Ixodes ricinus. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2013, 3, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siński, E.; Welc-Falęciak, R.; Zajkowska, J. Borrelia miyamotoi: A human tick-borne relapsing fever spirochete in Europe and its potential impact on public health. Adv. Med. Sci. 2016, 61, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikentjeva, M.; Geller, J.; Bragina, O. Ticks and Tick-Borne Pathogens in Popular Recreational Areas in Tallinn, Estonia: The Underestimated Risk of Tick-Borne Diseases. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornok, S.; Daccord, J.; Takács, N.; Kontschán, J.; Tuska-Szalay, B.; Sándor, A.D.; Szekeres, S.; Meli, M.L.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R. Investigation on haplotypes of ixodid ticks and retrospective finding of Borrelia miyamotoi in bank vole (Myodes glareolus) in Switzerland. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2022, 13, 101865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelebi, B.; Yeni, D.K.; Yılmaz, Y.; Matur, F.; Babür, C.; Öktem, M.A.; Sözen, M.; Karataş, A.; Raoult, D.; Mediannikov, O.; et al. Borrelia miyamotoi in wild rodents from four different regions of Turkey. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2023, 14, 102143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialini, C.; Cafiso, A.; Waldeck, M.; Lundgren, Å.; Fält, J.; Settergren, B.; Choklikitumnuey, P.; Chiappa, G.; Rosso, E.; Roveri, L.; et al. Prevalence of tick-borne pathogens in feeding and questing Ixodes ricinus ticks from Southern Sweden. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2025, 16, 102453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burri, C.; Schumann, O.; Schumann, C.; Gern, L. Are Apodemus spp. mice and Myodes glareolus reservoirs for Borrelia miyamotoi, Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis, Rickettsia helvetica, R. monacensis and Anaplasma phagocytophilum? Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2014, 5, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, C.; Gern, L.; Voordouw, M.J. Species co-occurrence patterns among Lyme borreliosis pathogens in the tick vector Ixodes ricinus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 7273–7280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, A.; Springer, A.; Raulf, M.K.; Fingerle, V.; Strube, C. 15-year Borrelia prevalence and species distribution monitoring in Ixodes ricinus/inopinatus populations in the city of Hanover, Germany. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2023, 14, 102074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schötta, A.M.; Stelzer, T.; Stanek, G.; Stockinger, H.; Wijnveld, M. Bacteria and protozoa with pathogenic potential in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Viennese recreational areas. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2023, 135, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoxha, I.; Dervovic, J.; Ruivo, M.; Wijnveld, M.; Obwaller, A.G.; Jäger, B.; Weiler, M.; Walochnik, J.; Kniha, E.; Alic, A. Molecular Typing of Tick-Borne Pathogens in Ixodids of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klitgaard, K.; Højgaard, J.; Isbrand, A.; Madsen, J.J.; Thorup, K.; Bødker, R. Screening for multiple tick-borne pathogens in Ixodes ricinus ticks from birds in Denmark during spring and autumn migration seasons. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2019, 10, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šujanová, A.; Cužiová, Z.; Václav, R. The Infection Rate of Bird-Feeding Ixodes ricinus Ticks with Borrelia garinii and B. valaisiana Varies with Host Haemosporidian Infection Status. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Genetic Marker | Sequence of Primers (5′->3′) | Annealing Temp. (°C) | Length of Amplicons (bp) | Usage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| flaB | FL84F: AGAAGCTTTCTAGTGGGTACAGA FL976R: GATTGGCCTGTGCAATCAT | 57 | 893 | PCR-RFLP, sequencing | [7] |

| Nested PCR | |||||

| 220f: CAGACAACAGAGGGAAAT | |||||

| 823r: TCAAGTCTATTTTGGAAAGCACC | 54 | 604 | PCR-RFLP | [43] | |

| FL120F: TGATGATGCTGCTGGGATGG | |||||

| FL908R: TCATCTGTCATTGTAGCATCTT | 56 | 789 | Sequencing | [7] | |

| mag-trnI | mag-268F: TCTAATTAAAACAGCHTGDGGAYT | ||||

| trnI-20R: TGAACATCCGACCTCAGG | 51 | 521–1395 | [41] | ||

| Nested PCR | PCR-SLP, sequencing | ||||

| mag-435F: CCATATAAGCTTCCGTTTCAAC | |||||

| trnI-65R: CTAACCACCTGAGCTATGATCC | 51 | 309–1183 | PCR-SLP, sequencing | [41] |

| Year of Study | Stage/Sex (%) | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Males | Nymphs | Larvae | ||

| Ixodes ricinus | |||||

| 2018 | 29 (18) | 2 (1.2) | 113 (70.2) | 17 (10.6) | 161 |

| 2019 | 57 (14.5) | 2 (0.5) | 313 (79.2) | 23 (5.8) | 395 |

| 2020 | 55 (22.3) | 1 (0.4) | 182 (73.7) | 9 (3.6) | 247 |

| 2021 | 27 (12.1) | 2 (0.8) | 168 (75) | 27 (12.1) | 224 |

| 2022 | 29 (17.4) | 127 (76) | 11 (6.6) | 167 | |

| Subtotal | 197 (16.5) | 7 (0.6) | 903 (75.6) | 87 (7.3) | 1194 |

| Dermacentor reticulatus | |||||

| 2018 | 1 (100) | 1 | |||

| 2019 | 8 (88.9) | 1 (11.1) | 9 | ||

| 2020 | 8 (80) | 2 (20) | 10 | ||

| 2021 | 12 (100) | 12 | |||

| 2022 | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) | 6 | ||

| Subtotal | 34 (89.5) | 4 (10.5) | 38 | ||

| Total | 231 (18.7) | 11 (0.9) | 903 (73.3) | 87 (7.1) | 1232 |

| Province | Stage/Sex (%) | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Males | Nymphs | Larvae | ||

| Ixodes ricinus | |||||

| Zachodniopomorskie | 54 (15.7) | 6 (1.7) | 238 (69.2) | 46 (13.4) | 344 |

| Lubuskie | 13 (19.2) | 0 (0) | 53 (77.9) | 2 (2.9) | 68 |

| Wielkopolskie | 11 (16.2) | 0 (0) | 52 (76.5) | 5 (7.3) | 68 |

| Dolnośląskie | 16 (16) | 0 (0) | 75 (75) | 9 (9) | 100 |

| Opolskie | 6 (15) | 0 (0) | 33 (82.5) | 1 (2.5) | 40 |

| Pomorskie | 12 (18.2) | 0 (0) | 52 (78.8) | 2 (3) | 66 |

| Kujawsko-Pomorskie | 9 (23.1) | 0 (0) | 30 (76.9) | 0 (0) | 39 |

| Łódzkie | 6 (14) | 0 (0) | 37 (86) | 0 (0) | 43 |

| Śląskie | 11 (17.4) | 0 (0) | 50 (79.4) | 2 (3.2) | 63 |

| Warmińsko-Mazurskie | 10 (20.8) | 0 (0) | 38 (79.2) | 0 (0) | 48 |

| Mazowieckie | 9 (18) | 0 (0) | 39 (78) | 2 (4) | 50 |

| Świętokrzyskie | 9 (16.1) | 0 (0) | 44 (78.6) | 3 (5.3) | 56 |

| Małopolskie | 12 (15.2) | 0 (0) | 52 (65.8) | 15 (20) | 79 |

| Podlaskie | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | 36 (90) | 0 (0) | 40 |

| Lubelskie | 8 (17.8) | 0 (0) | 37 (82.2) | 0 (0) | 45 |

| Podkarpackie | 7 (15.6) | 1 (2.2) | 37 (82.2) | 0 (0) | 45 |

| Subtotal | 197 (16.5) | 7 (0.6) | 903 (75.6) | 87 (7.3) | 1194 |

| Dermacentor reticulatus | |||||

| Zachodniopomorskie | 31 (91.2) | 3 (8.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 34 |

| Lubuskie | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 |

| Subtotal | 34 (89.5) | 4 (10.5) | 38 | ||

| Total | 231 (18.7) | 11 (0.9) | 903 (73.3) | 87 (7.1) | 1232 |

| Year of Study | Stage/Sex [N/n (%)] | Total [N/n (%)] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Males | Nymphs | Larvae | ||

| Ixodes ricinus | |||||

| 2018 | 3/29 (10.3) | 0/2 (0) | 11/113 (9.7) | 2/17 (11.8) | 16/161 (9.9) |

| 2019 | 14/57 (24.6) | 0/2 (0) | 71/313 (22.7) | 6/23 (26.1) | 91/395 (23) |

| 2020 | 14/55 (25.5) | 0/1 (0) | 54/182 (29.7) | 0/9 (0) | 68/247 (27.5) |

| 2021 | 8/27 (29.6) | 1/2 (50) | 21/168 (12.5) | 5/27 (18.5) | 35/224 (15.6) |

| 2022 | 2/29 (6.9) | 7/127 (5.5) | 0/11 (0) | 9/167 (5.4) | |

| Subtotal | 41/197 (20.8) | 1/7 (14.3) | 164/903 (18.2) | 13/87 (14.9) | 219/1194 (18.3) |

| Dermacentor reticulatus | |||||

| 2018 | 0/1 (0) | 0/1 (0) | |||

| 2019 | 4/8 (50) | 0/1 (0) | 4/9 (44.4) | ||

| 2020 | 2/8 (25) | 0/2 (0) | 2/10 (20) | ||

| 2021 | 7/12 (58.3) | 7/12 (58.3) | |||

| 2022 | 0/5 (0) | 0/1 (0) | 0/6 (0) | ||

| Subtotal | 13/34 (38.2) | 0/4 (0) | 13/38 (34.2) | ||

| Total | 54/231 (23.4) | 1/11 (9.1) | 164/903 (18.2) | 13/87 (14.9) | 232/1232 (18.8) |

| Province | Stage/Sex [N/n (%)] | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Males | Nymphs | Larvae | ||

| Ixodes ricinus | |||||

| Zachodniopomorskie | 14/54 (25.9) | 1/6 (16.7) | 49/238 (20.6) | 9/46 (19.6) | 73/344 (21.2) |

| Lubuskie | 3/13 (23.1) | 0 (0) | 8/53 (15.1) | 1/2 (50) | 12/68 (17.6) |

| Wielkopolskie | 2/11 (18.2) | 0 (0) | 8/52 (15.4) | 0/5 (0) | 10/68 (14.7) |

| Dolnośląskie | 4/16 (25) | 0 (0) | 16/75 (21.3) | 1/9 (11.1) | 21/100 (21) |

| Opolskie | 0/6 (0) | 0 (0) | 4/33 (12.1) | 0/1 (0) | 4/40 (10) |

| Pomorskie | 4/12 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 11/52 (21.2) | 1/2 (50) | 16/66 (24.2) |

| Kujawsko-Pomorskie | 1/9 (11.1) | 0 (0) | 3/30 (10) | 0 (0) | 4/39 (10.3) |

| Łódzkie | 0/6 (0) | 0 (0) | 5/37 (13.5) | 0 (0) | 5/43 (11.6) |

| Śląskie | 3/11 (27.3) | 0 (0) | 12/50 (24) | 2 (3.2) | 15/63 (23.8) |

| Warmińsko-Mazurskie | 2/10 (20) | 0 (0) | 5/38 (13.2) | 0 (0) | 7/48 (14.6) |

| Mazowieckie | 2/9 (22.2) | 0 (0) | 6/39 (15.4) | 0/2 (0) | 8/50 (16) |

| Świętokrzyskie | 1/9 (11.1) | 0 (0) | 6/44 (13.6) | 1/3 (33.3) | 8/56 (14.3) |

| Małopolskie | 4/12 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 7/52 (13.5) | 0/15 (0) | 11/79 (13.9) |

| Podlaskie | 1/4 (25) | 0 (0) | 6/36 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 7/40 (17.5) |

| Lubelskie | 0/8 (0) | 0 (0) | 8/37 (21.6) | 0 (0) | 8/45 (17.8) |

| Podkarpackie | 0/7 (0) | 0/1 (0) | 10/37 (27) | 0 (0) | 10/45 (22.2) |

| Subtotal | 41/197 (20.8) | 1/7 (14.3) | 164/903 (18.2) | 13/87 (14.9) | 219/1194 (18.3) |

| Dermacentor reticulatus | |||||

| Zachodniopomorskie | 12/31 (38.7) | 0/3 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 12/34 (35.3) |

| Lubuskie | 1/3 (33.3) | 0/1 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1/4 (25) |

| Subtotal | 13/34 (38.2) | 0/4 (0) | 13/38 (34.2) | ||

| Total | 54/231 (23.4) | 1/11 (9.1) | 164/903 (18.2) | 13/87 (14.9) | 232/1232 (18.8) |

| Spirochete Species | Ixodes ricinus (N/%) | Dermacentor reticulatus (Females Only; N/%) | Total (N/%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | Subtotal | |||||

| Adults | Nymphs | Larvae | ||||

| Bl. afzelii | 15/35.7 | 78/47.6 | 6/46.2 | 99/45.2 | 5/38.5 | 104/44.8 |

| Bl. garinii | 2/4.8 | 9/5.5 | 1/7.7 | 12/5.5 | 1/7.7 | 13/5.6 |

| Bl. burgdorferi | 10/23.8 | 22/13.4 | 1/7.7 | 33/15.1 | 33/14.2 | |

| Bl. valaisiana | 4/9.5 | 12/7.3 | 16/7.3 | 1/7.7 | 17/7.3 | |

| Bl. spielmanii | 2/4.8 | 12/7.3 | 3/23.1 | 17/7.8 | 17/7.3 | |

| Bl. bissettiae | 1/2.4 | 8/4.9 | 1/7.7 | 10/4.6 | 10/4.3 | |

| Bl. californiensis | 1/0.6 | 1/0.5 | 1/7.7 | 2/0.9 | ||

| Bl. carolinensis | 1/0.6 | 1/0.5 | 1/0.4 | |||

| B. miyamotoi | 8/19 | 21/12.8 | 1/7.7 | 30/13.7 | 5/38.5 | 35/15.1 |

| Total (N) | 42 | 164 | 13 | 219 | 13 | 232 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wodecka, B.; Kolomiiets, V. Prevalence of Borreliaceae Spirochetes in Ticks Removed from Humans in Poland During 2018–2022. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1234. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121234

Wodecka B, Kolomiiets V. Prevalence of Borreliaceae Spirochetes in Ticks Removed from Humans in Poland During 2018–2022. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1234. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121234

Chicago/Turabian StyleWodecka, Beata, and Valentyna Kolomiiets. 2025. "Prevalence of Borreliaceae Spirochetes in Ticks Removed from Humans in Poland During 2018–2022" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1234. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121234

APA StyleWodecka, B., & Kolomiiets, V. (2025). Prevalence of Borreliaceae Spirochetes in Ticks Removed from Humans in Poland During 2018–2022. Pathogens, 14(12), 1234. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121234