Abstract

Chlamydia psittaci is traditionally regarded as a globally distributed avian pathogen that can cause zoonotic spill-over. Molecular research has identified an extended global host range and significant genetic diversity. However, Australia has reported a reduced host range (avian, horse, and human) with a dominance of clonal strains, denoted ST24. To better understand the widespread of this strain type in Australia, multilocus sequence typing (MLST) and ompA genotyping were applied on samples from a range of hosts (avian, equine, marsupial, and bovine) from Australia. MLST confirms that clonal ST24 strains dominate infections of Australian psittacine and equine hosts (82/88; 93.18%). However, this study also found novel hosts (Australian white ibis, King parrots, racing pigeon, bovine, and a wallaby) and demonstrated that strain diversity does exist in Australia. The discovery of a C. psittaci novel strain (ST306) in a novel host, the Western brush wallaby, is the first detection in a marsupial. Analysis of the results of this study applied a multidisciplinary approach regarding Chlamydia infections, equine infectious disease, ecology, and One Health. Recommendations include an update for the descriptive framework of C. psittaci disease and cell biology work to inform pathogenicity and complement molecular epidemiology.

Keywords:

Chlamydia psittaci; genetic diversity; Australia; MLST; novel strains; novel hosts; ompA genotyping 1. Introduction

Chlamydia psittaci is traditionally regarded as an avian pathogen of global distribution with zoonotic potential [1]. Chlamydia psittaci infections are common in a variety of birds, including poultry, wild birds, and pet birds [1,2]. These infections are also found in humans, and to a lesser degree, domesticated livestock, such as sheep, cattle, horses, and pigs [2,3]. Spill-over transmission from the avian host to the non-avian host, via direct or indirect contact, is the hypothesised route of infection [1,4]. Compared to global studies [5,6,7], Australia has limited reporting in humans and domesticated livestock, such as sheep and cattle [4,8,9,10]. In contrast, C. psittaci has found a preferred host niche in the Australian psittacine birds [11,12] and Thoroughbred horses [13,14].

Whilst C. psittaci infections in Australian psittacine birds are not new [15], the first descriptions of C. psittaci in Thoroughbred horses in 2014 were considered novel and raised biosecurity concerns regarding a potential emerging infection [16]. Chlamydia psittaci infection in a pregnant horse resulted in late-term pregnancy loss and a novel infectious aerosol transmission of C. psittaci to humans handling infected equine foetal membranes [16,17]. Since then, C. psittaci has remained an annually reported cause of foal loss in the Hunter Valley region of Australia, a major Thoroughbred breeding center, as observed in a longitudinal study over four years from 2016 to 2020 [14,18]. A recent retrospective study has also provided evidence that this pathogen is not new in Australian horses and has been a cause of sporadic equine foal loss in Australia for over 30 years [19]. These studies highlight potential underreporting as C. psittaci was not previously considered in equine diagnostic panels. Addressing C. psittaci knowledge gaps is important considering the high individual value of the Thoroughbred foals and the zoonotic risk to farmworkers.

Globally, C. psittaci strains are genetically diverse, as evidenced by ongoing molecular characterisation by a chlamydial marker gene ompA [20], multilocus sequence typing (MLST) [21,22], and/or whole genome sequencing (WGS) [4,23]. The Chlamydiales MLST emerged as a “gold standard” methodology for molecular characterisation of strains, barcoding them as sequence types (STs). MLST of Australian equine samples typed to date have characterized a dominant strain, denoted ST24, in 53/55 samples (96.3%) [14,17,18,19,24] spanning three geographically separate regions in Australia (New South Wales [NSW], Victoria [Vic], and South Australia [SA]). This same strain has also been confirmed in a range of Australian psittacine birds, including little corella (Cacatua sanguinea), scaly breasted lorikeet (Trichoglossus chlorolepidotus), cockatiel (Nymphicus hollandicus), crimson rosella (Platycercus elegans), and the budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus) [12,25,26] from different Australian states (NSW, Vic), and importantly, humans from NSW [26]. Genomic studies have found that the Australian psittacine, horse, and human ST24 strains are highly clonal, with less than 80 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) differences [4,13] and that they cluster with other global virulent ST24 strains [22,23].

Despite the reported dominance of ST24, there is evidence that other STs can infect horses and birds in Australia. In a single case of equine foal loss in a northern region of Australia (Queensland [Qld]), a C. psittaci strain, denoted as ST27, was detected [13]. This “pigeon type” strain clustered with other closely related pigeon strains from Europe [22,27]. It has also been detected in a wild sulphur-crested cockatoo (Cacatua galerita) from a geographically different location (Vic.) [12]. Additionally, another closely related but distinct “pigeon type” strain (ST35) was detected from a spotted dove (Spilopelia chinensis) from yet another geographically different location (NSW) [13].

To date, no other C. psittaci STs, nor new hosts, have been identified in Australia, contrasting starkly with the known global host and genetic diversity [1,22,27]. These studies suggest that there may be a potential underreporting of C. psittaci host range and genetic diversity, perhaps masked by a dominant clonal ST24 strain, raising questions about the epidemiology of these infections in Australia. This study applies MLST and ompA genotyping to evaluate the widespread of the Australian ST24, determine the presence of other genetically distinct strains, and expand knowledge on the avian and mammalian host range. Furthermore, we applied and reviewed a multidisciplinary approach regarding Chlamydia infections, ecology, equine infectious disease, and One Health into discussion of this original work. This will provide future directions for C. psittaci research to prevent loss of Thoroughbred foals and potential zoonotic events.

2. Results

In this study, we applied C. psittaci MLST and ompA genotyping on 21 C. psittaci-positive samples to evaluate genetic diversity of these infections. The four new clinical samples from this study of an aborted foal (Equus caballus), a bovine (Bos taurus), and two corellas (Cacatua sanguinea) from cases of suspected chlamydiosis were confirmed C. psittaci-positive by a C. psittaci-specific qPCR assay (Table S1). Chlamydia psittaci MLST and ompA genotyping were then applied to these four samples and 17 previously diagnosed C. psittaci-positive samples, selected from a range of Australian hosts (Table S1). All 21 samples were successfully ompA genotyped; however, complete MLST was achieved for 19 samples. Complete MLST was not achieved for two samples (Ibis A and Cow UGT) due to low infection loads, and these were excluded from the MLST analysis.

2.1. Hosts, Infecting Strains Diversity and Clinical Signs

An evaluation of genetic diversity using MLST was performed on the 15 newly typed strains from this study and 73 previously characterised strains from all reported cases of C. psittaci cases in Australia (Table S1). Chlamydia psittaci-specific MLST detected a single dominant clonal strain, ST24, in a total of 82/88 (93.18%) samples (Table S1) from a total of 68/73 (93.15%) Australian animal and human hosts (Table 1). With regards to the strains in avian infections, all but one Australian psittacine (W234-12) strains were denoted ST24 (19/20, 95.00%). Clinical signs of emaciation, conjunctivitis, and dyspnoea, consistent with a diagnosis of psittacosis, were observed in 10 out of 19 (52.6%) Australian psittacine birds with ST24 infections. One of these infections resulted in zoonotic transmission (Adel_Rosella). In cases of foal loss, C. psittaci ST24 was detected in 57/59 samples (96.61%), except for one case in Queensland where ST27 strains were detected in two samples (2/59, 3.39%; Qld/H/pl; Qld/H/Tissues) (Table S1). ST24 was detected in 44/45 (97.77%) of equine hosts (Table 1), with all 45 hosts presenting with clinical signs, and one of these events also included documented zoonotic transmission (Horse_Pl) (Table S1). All cases of human psittacosis (n = 5 hosts) were previously described and were due to direct or indirect contact with presumably infected birds. All detected Australian human sequence types were ST24 (5/5; 100%), and severe clinical signs were observed in 4/5 (80%) hosts (Table 1).

Table 1.

Hosts and their infecting strain diversity with noted presence or absence of clinical signs of chlamydiosis in Australia. The clinical signs are described in Table S1 in detail for each host and include: pneumonia in humans; wasting, dyspnoea, and conjunctivitis in birds; and reproductive loss in horses.

The Australian non-psittacine birds (Racing_pigeon and NSW/Dove/tissue) displayed strain diversity (ST213 and ST35, respectively), although both had clinical signs consistent with psittacosis (Table S1). A novel strain, ST306, was detected in a Western brush wallaby (Macropus irma) with the reported clinical signs of joint pathology (Table 1).

2.2. Phylogenetic Analyses of Detected C. psittaci Strains

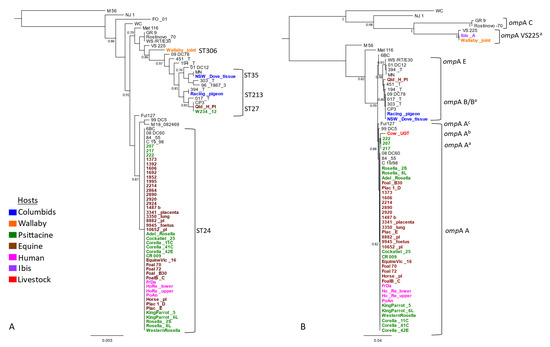

The Australian strains were also phylogenetically compared with previous global 26 strains, selected for representative host and ST diversity (Table S1). Newly typed strains from Australian king parrots (Alisterus scapularis), little corellas (Cacatua sanguinea), rosellas (Platycercus elegans), western rosellas (Platycerus icterotis), and horses, described in this study, resolved ST24 and clustered into well-supported globally distributed clonal ST24 clade (Figure 1A). The new C. psittaci strain ST306, detected in the wallaby, formed its own clade. The racing pigeon strain denoted ST213, was identical to a strain 394_T from a pigeon from Switzerland. This strain clustered in a broader “pigeon clade” with other closely related strains from Australian horses, a cockatoo and a dove, and global pigeon and mammalian hosts (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Genetic diversity and phylogenetic analyses of C. psittaci from this study. The mid-point rooted phylogenetic analyses of (A) the concatenated 3098 bp C. psittaci STs alignment, and (B) full length (1050 bp) ompA genotypes alignment. Support values of >0.80 are displayed on the tree nodes, and the scale bar represents the number of substitutions per site. The hosts are indicated as per colours in the legend. Australian isolates are denoted in bold and in colours as per host (outlined in the legend), while global isolates are denoted in normal black font.

Next, we evaluated genetic diversity using ompA genotyping on a total of 57 Australian strains. This consisted of 21 newly typed strains from this study, including samples from an Australian white ibis (Threskiornis moluccus) (Ibis_A) and a bovine (Cow_UGT), and 36 previously characterized Australian and global strains (Table S1). The ompA genotyping revealed extended genetic diversity of C. psittaci in Australia; however, genotype A was the most common (Figure 1B). Almost all ST24 strains from this study had identical genotype A; however, variations of genotype A were also observed. The ompA genotypes of the Victorian psittacine strains (217, 207, 222), denoted Aa, were identical to each other, but differed from genotype A by one non-synonymous SNP. The ompA from an Australian bovine, denoted Ab, differed by six to seven SNPs from other genotype A sequences. Finally, the ompA sequences, denoted Ac, from a seabird Fulmar (Fulmarus glacialiscode) and German horse strains, differed by one SNP between them and two from the ompA genotype.

The Australian racing pigeon had ompA genotype B, clustering with another identical genotype B, including that of NSW_Dove (Figure 1B). However, variations of genotype B (denoted Ba) were also observed. The ompAs from other global pigeon strains and an Australian horse (Qld_H_pl) strain were of these genetically diverse Ba genotypes. The ompA sequences detected in the wallaby and Australian white ibis were identical but differed by three SNPs from the reference VS225 ompA F, representing a novel ompA Fa genotype (Figure 1B).

For 64 strains, where we had paired ompA and MLST data, we also used Fastbaps with three levels of hierarchical clustering to further define genetic clusters based on MLST and ompA genotyping (Figure S1, Table S2). The STs resolved into two primary clusters: monophyletic Cluster 1 (highlighted in orange) and polyphyletic Cluster 2 (highlighted in green), respectively (Figure S1). Cluster 1 consisted of “pigeon” STs, not forming any further clades. Cluster 2 further divided into three clades (2.2, 2.3, and 2.4) (Figure S1A). Clades 2.2 and 2.3 consisted of genetically diverse STs, including the novel wallaby ST306, while Clade 2.4 consisted of ST24 and closely related ST218 (Figure 1a and Figure S1A). Similarly, ompA alignment also resolved strains into two primary clusters; however, both clusters (Cluster 1 highlighted in orange, and Cluster 2 highlighted in green) were polyphyletic and further resolved into clades and subclades (Figure S1B).

In this study, by utilizing MLST and ompA genotyping schemes, we revealed increasing genetic diversity, including the novel strain ST306 detected in a wallaby and novel ompA sequences detected in a cow and an ibis, and an expanded host range across all sampled states (with an exception of Northern Territory and Tasmania) in Australia, including a wallaby, bovine, psittacine (king parrot, Adelaide rosella, and western rosella), and non-psittacine (racing pigeon and Australian white ibis) birds (Figure S2).

3. Discussion

This study reveals an extended range of Australian animal hosts infected with clonal (ST24) C. psittaci, as well as novel (ST306) and previously described genetically diverse C. psittaci strains (ST213, ST35, ST27). Focusing on the Australian setting, ST24 is commonly found in psittacine, equine, and human infections [4,12,14,17,18,19]. Less commonly, there are isolated reports of the C. psittaci “pigeon” (ST27, ST35 and ST213) strains infecting a sulphur-crested cockatoo (Cacatua galerita), two columbids (Columba livia domestica and Spilopelia chinensis), and an equine (Equus caballus) [12,13]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first evidence of a genetically novel strain (ST306/novel ompA) infecting a new native marsupial host, a western brush wallaby (Macropus irma). Furthermore, ompA genotyping revealed genetically diverse strains in a bovine Australian wallaby and white ibis, clustering with genotype A and F, respectively.

3.1. Uncovering C. psittaci Genetic Diversity

A comparison of global and Australian strains regarding diversity highlights the widespread of the ST24 in Australia. Most Australian studies, including the new molecular characterisation in this study, were performed on C. psittaci-positive samples from symptomatic and asymptomatic hosts [12,13,14,17,19,26]. However, global studies, often subjected to the same selection bias, still display a greater diversity in both strains and hosts [22]. Studies evaluating global C. psittaci genetic diversity identify at least 30 different STs and at least 15 different ompA genotypes, with an actively expanding range of hosts, including humans, domesticated livestock (sheep, cattle, pigs), and poultry (ducks, turkeys, chickens), and a wide range of free-range psittacine and non-psittacine birds [21,22]. Acknowledging the limitations in the Australian studies to date, are we underestimating the diversity of C. psittaci and host range in Australia?

Our findings suggest that there is likely to be an underestimation of diversity and host range in Australia. This might be the result of simply not testing a broad range of wildlife as well as domesticated animal species. Chlamydia psittaci has shown to be the most diversifying chlamydial species already a decade ago [21]. Indeed, to date, the number of novel STs of C. psittaci submitted to PubMLST is still growing, as well as the number of previously unrecognised host species. Furthermore, considering the increase in host species for C. psittaci [21], it is justifiable to suggest that diversity and host range is underestimated, not only in Australia but globally as well.

3.2. Roadmap to Understanding the Pathogenicity of Equine Abortogenic C. psittaci

Australian studies have focused on molecular descriptions of equine strains, which, on their own, cannot provide an informed understanding of the pathogenicity of each strain and the mechanism of equine foal loss. Indeed, any postulated potential altered pathogenicity/tropism in an emerging Australian equine strain must be interpreted with caution. In contrast, detailed cell biology studies are often performed overseas [2]. A recent European cell biology study has shown in vitro avian strains to be more pathogenic than mammalian strains regarding infection and zoonotic potential [28]. There is a lack of cell biology studies using Australian equine isolates, which may shed new light on mammalian pathogenicity.

We are still facing knowledge gaps on how C. psittaci is transmitted to the pregnant mare, how it colonises the placenta, and how pathological processes in the foetal membranes/organs are induced. If the infectious agent (chlamydial elementary bodies [EBs]) is orally ingested from pastures contaminated with faecal droppings containing C. psittaci, information about the density of the bird population shedding C. psittaci is of importance. While psittacine birds might play a major role in Australia, pigeons might be considered as a potential infection source in European countries. Moreover, the case numbers of equine foetal loss in the respective geographical regions are closely related to the type and density of horse farming and breeding. Mixed infection of C. psittaci and other abortigenic agents (i.e., Equine Herpes Virus 1 [EHV-1]) have been reported [22] but it remains unclear whether one of the agents (or a combination of both) induced the abortion. Specific laboratory methods, such as immunohistochemistry and in-situ hybridisation, are helpful to demonstrate the agent in associated tissue lesions. Further characterisation of histopathological lesions and inflammatory processes would help us to understand this ongoing pathogenesis, as learnt from field and experimental infection studies of ovine enzootic abortion caused by C. abortus, although the latter might not be justified in the equine host.

3.3. Are We Missing Other Hosts?

Other major equine breeding centres worldwide have not reported chlamydial foal loss despite globally reported C. psittaci prevalence in birds of between 1–5% [1,11]. Should we be exploring host diversity closer to home for an answer? An area of future research could involve Australian fauna that shares a common habitat with livestock. The detection of C. psittaci in a wallaby joint in this study is the first detection of C. psittaci in a marsupial. However, the severe impact of C. pecorum infections on Australian koalas, resulting in reproductive, urinary, and ocular disease, is well known [8,29]. Earlier reports of C. psittaci in koalas have since been revised, and to date, there remains no evidence of C. psittaci in koalas, nor any other marsupial. Considering the close contact koalas have with Australian birds in the shared arboreal habitat, and the C. psittaci preferred niche of the respiratory and reproductive tract, should C. psittaci be considered on a diagnostic panel for koala disease? Furthermore, should other marsupials be investigated considering the shared landscape?

It is becoming clear that several species of Chlamydia that had previously not been considered to be present in hosts, such as horses, marsupials, and others, do indeed infect these hosts. Part of the issue is that, previously, we were not considering C. psittaci as a potential cause and did not routinely test specifically for this species. If we test more hosts, such as Australian marsupials, for C. psittaci, might we expect to find more? Given the opportunity for transmission between hosts due to co-location, this may well be the case.

Although the role of Chlamydia in disease is well known in koalas and other Australian marsupials, C. psittaci is not actively investigated for in marsupials by veterinary diagnosticians, and its presence and impact are not known. The detection of C. psittaci from the joint of a wallaby in this study is significant and suggests a broader host range and possible pathogenicity in marsupials than we currently understand. We sporadically observe inflammatory lesions in koalas and other marsupials, for which aetiology is not yet determined. Targeted investigation of C. psittaci in Australian marsupials would be of great benefit; this study suggests the host range, and thus conservation and zoonotic risk impacts may be broader than we presently appreciate.

Australian flying foxes (Pteropus spp. fruit bats) are known reservoirs for zoonotic viruses, including Hendra virus, Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV), and Menangle virus [30,31,32]. Hendra virus spill-over transmission from flying foxes to horses occurs annually, including recently in the Upper Hunter Valley of NSW, a major Thoroughbred breeding centre [33,34,35]. Overseas studies have observed a prevalence of 31.4% of Chlamydiales in free-ranging and captive bats from a range of families in the Yinpterochiroptera and Yangochiroptera bat suborders [36], but no data currently exist on chlamydial infections in Australian bats. Understanding what is happening in Australia at the wildlife/equine/human interface provides knowledge about the emerging zoonotic disease.

As nectar feeders and pollinators, Australian flying foxes play critical ecosystem roles as they move nomadically across the landscape, feeding on flowering native trees. When nectar is scarce, for example, as a result of climate cycles and loss of habitat due to land clearing, flying foxes will seek out alternative food sources, including fruit trees in urban and agricultural areas. Subsequently, increased contact with horses and other domestic animals may amplify the risk of pathogen spill-over. Further investigations into the infectious agents circulating endemically in Australian bats, as well as systematic pathogen discovery efforts following unusual deaths in domestic animals and livestock, is required to detect the extend of pathogen spill over from bats. Sustainable One Health solutions, such as habitat restoration, present the most promising opportunities for preventing spill-over [37].

3.4. Diagnostic Directions for C. psittaci Equine Abortion and Zoonosis

A diagnosis of C. psittaci in the equine is challenging [14,38]. Whilst high loads are noted in clinical cases of both avian psittacosis and equine foal loss, the significance of detection of low levels in a healthy host remains unknown [18]. Importantly, early detection for intervention in the pregnant mare is still lacking. Considering that Australia’s major Thoroughbred breeding centre in the Upper Hunter Valley is in a potentially endemic ST24 region, what risk does the emerging strain diversity pose for an outbreak of foal loss and human psittacosis?

There are now multiple reports implicating C. psittaci as a cause of abortion in horses. This is an emerging pathogen that must be included in routine microbiological diagnostic testing of all equine abortions. It is not clear whether there is a clearly delineated geographical distribution of C. psittaci abortion, but heightened awareness and active surveillance in the future will help to address this concern. The development of excellent molecular diagnostic tests will enable the rapid diagnosis of this organism in clinical samples, which in turn will improve surveillance for this organism. There is a serious zoonotic potential associated with C. psittaci and so equine veterinarians and staff on equine breeding farms must take more precautions when dealing with the aborted equine conceptus and the affected mare.

Equine parturition can now be considered as a time of higher risk for transmission of C. psittaci to farmworkers [16,39]. Compared to global reporting, there is potential underreporting in Australia, with less than 50 notified cases of psittacosis per annum in the past decade reported in the Australian National Notifiable Diseases Surveillances (ANNDS) [40]. To date, some regions are considered endemic, and this study has identified the upper Hunter Valley as another potential region. The recent advent of C. psittaci rapid diagnostic testing in horses [41] shows promise for farm management strategies of C. psittaci and highlights the importance of front-line workers for zoonotic disease. As the world moves towards the more informed One Health approach to disease, a revision of the term psittacosis to chlamydiosis is suggested. This study has provided evidence of an expansion of a host range with zoonotic potential and the term psittacosis in the lexicon may be misleading and limit potential host investigations.

The trans-disciplinary benefits of a One Health approach to investigate the epidemiology of C. psittaci will improve our understanding and management of risk, not just for this disease agent but for zoonoses more broadly. There are additional benefits to landscape ecosystem health [42] and to local capacity to manage threats at the animal–human–wildlife–environment interface [43].

In summary, the molecular analyses of C. psittaci have shown the widespread of a dominant strain (ST24) in Australia with the serious consequences of morbidity in people and animals, and mortality in equines. This work has identified a potentially endemic region within Australia and an expanded host range for C. psittaci, including a novel marsupial, an expanded bird range, and a bovine. Future directions include a recommendation to update the descriptive framework of C. psittaci disease, implement ongoing surveillance and strain identification for potential outbreak intervention, and include cell biology work to inform pathogenicity.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Collection, DNA Extraction and C. psittaci Screening

In this study, molecular characterisation of C. psittaci was performed on a combined set of 4 new and 17 existing samples which were opportunistically collected from a range of sources and hosts across Australia. The four new samples from this study were collected from a new 2020 case of C. psittaci-suspected aborted foal from the Hunter Valley region, NSW (pooled foetal swab; n = 1), a clinically affected bovine from Western Australia (WA) (urogenital tract (UGT; n = 1), and two symptomatic dead little corellas from a wildlife hospital in Qld (pooled eye/choana and cloaca swabs; n = 2). All dry and individually capped swab samples were collected as a part of routine veterinary diagnostic investigations and stored at −20 °C until processing. Swabs were then processed by adding 300 µL of sterile TE (Tris-EDTA) buffer, vortexing for one min, and heating at 95 °C for 10 min. Heat lysis was used to improve the host cell lysis method and release (strict intracellular) chlamydial elementary bodies into solution. DNA extraction was performed using the QIAmp DNA blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Chadstone, VIC, Australia), as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Extracted DNA was eluted in 100 µl of supplied AE buffer (Qiagen) and stored at −20 °C until further analysis. The DNA was screened in duplicate for C. psittaci with the C. psittaci-specific qPCRs targeting a 263 bp fragment of the ORF 607 gene with a Ct result of <33 being deemed positive [8].

This sample set was supplemented with the addition of 16 previously tested C. psittaci-positive DNA samples from a range of hosts across Australia, including equine (n = 3), avian (total n = 12 [psittacine n = 11 and columbid n = 1]), and marsupial (n = 1) hosts, which were generously supplied by collaborators from veterinary diagnostic laboratories across Australia. These samples were initially screened by the respective veterinary diagnostic reference of C. psittaci-specific assays, using the CPS100 and CPS101 primers which targeted the 16S rRNA gene/16S–23S rRNA space [44] or 76bp fragment of the C. psittaci outer membrane protein A (ompA) gene [45]. We also used a C. psittaci-positive sample (Ibis_A) from an asymptomatic Australian white ibis (Threskiornis moluccus) from the same region as the Thoroughbred horses NSW (faeces; n = 1), from a recent study [18]. Prior to further analyses, all samples were internally confirmed for C. psittaci using the same C. psittaci-specific qPCR assays as outlined above for new samples [17]. The final catalogue of samples for molecular characterisation included 21 samples (4 detected in newly collected samples and 17 in previously screened samples). Details are available for all samples in this study regarding host, anatomical site, clinical manifestation, location, and date (Table S1). Trained and experienced veterinary teams collected all swabs, and ethical approval for using these swabs was granted by the University of the Sunshine Coast (ANE 1939/ ANE2057).

4.2. Genotyping

C. psittaci genotyping was applied on a total of 21 samples from this study, using C. psittaci-specific MLST [46] and/or full-length major outer membrane (ompA) gene sequencing [20] as previously described.

Conventional PCRs were performed in a total of 35 µL reaction volumes, including 17.5 µL of the 2X Amplitaq Gold master mix (Thermo Scientific, Scoresby, VIC, Australia), 1 µL of 0.3 µM primer (using ten µM working concentration), 12.5 µL of MilliQ water, and 4 µl of DNA template with cycling profiles as previously described [45]. PCR products were visualised on 1.5% agarose gel stained with SyberSafe following gel electrophoresis for 30 min on 100V. Amplicons were then sent for purification and bidirectional Sanger sequencing (Macrogen, Seoul, Korea). Chromatograms were examined for quality and analysed in Geneious Prime 2020.2.4 [47]. Chromatograms of low quality, evaluated based on Phred scores and lengths shorter than the reference amplicons, were discarded, and sequencing was repeated. The MLST sequences were compared with the Chlamydiales MLST database [48] to determine and/or assign novel alleles and sequence types (ST). The newly generated ompA sequences were subjected to BLASTn analysis [49]. MLST and ompAs sequences generated in this study were deposited in the Chlamydiales MLST database and GenBank with accession numbers MZ207919–MZ207938 and MZ298912.

4.3. Phylogenetic and Cluster Analyses

The 21 ompA and 19 MLST sequences from this study were then aligned using ClustalOmega (as implemented in Geneiois Prime 2020.2.4) to other representative, publicly available ompA and/or MLST sequences. Metadata for these samples (including genotype, hosts, geographical locations, year of isolation, clinical manifestations, and other) are outlined in Table S1. The midpoint rooted maximum likelihood tree was constructed using the 3098 bp alignment of concatenated MLST from a total of 74 strains and 1050 bp ompA alignment from ompA sequences from a total of 66 strains with FastTree using the GTR + G nucleotide substitution model (as implemented in Geneious Prime) with a strain M56 used as an outlier.

Paired ompA and MLST sequences were available for 64 strains analyzed in this study (Table S1). To further assess C. psittaci population structure and cluster strains into genetically close groups (phylogroups), a paired ompA and MLST alignments from 64 strains were analyzed using the R package FASTbaps [50] to partition the data into groups using Bayesian clustering (using the symmetric method for prior optimization and three levels of clustering) (Table S2, Figure S1).

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pathogens10081015/s1, TableS1: Samples used in study. Table S2: BAPS analyses of MLST and ompA genotypes from this study. Figure S1: Genetic clustering based on paired MLST and ompA genotyping using Fastbaps analyses with three levels of hierarchical clustering. A: MLST clustering; B: ompA clustering. The first number denotes major clusters (phylogroups), coloured in orange and green, the second number denotes clades (coloured in a lighter shade), and the third number denotes sub-clades (lineage). Figure S2: Schematic representation of various hosts for C. psittaci and MLST strain identity from Australia. Location and host legend from left to right in a clockwise direction is Western Australia: wallaby, bovine, psittacine; Queensland; equine, psittacine; New South Wales: equine, columbids, ibis, psittacine, human; Victoria: equine, psittacine; and South Australia: equine, psittacine. Detection of C. psittaci in Northern Territory and Tasmania is unknown at present.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: S.I.A. and M.J.; methodology (including laboratory and bioinformatic work) and data analyses: S.I.A., V.K., A.L., M.J.; investigations and sample collections: S.I.A., C.J., A.L., J.D., J.A.-G., J.G., S.H., N.P., A.J.P., N.B., Y.P., A.-L.C., L.W., P.T., M.J.; writing—original draft preparation: S.I.A.; funding acquisition: M.J.; writing—review and editing: all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Research Award (DE190100238), awarded to M.J.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted with the approval provided by the Animal Ethics Committee of the University of the Sunshine Coast (ANE 1939/ANE2057).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The MLST and ompA sequences from this study were deposited in the Chlamydiales PubMLST database and Genbank.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the diagnostics laboratory teams from the University of Melbourne, NSW DPI and WA DPIRD for assisting us in sample collection and the USC Chlamydia team for their assistance during laboratory analyses.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the study’s design, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Knittler, M.R.; Sachse, K. Chlamydia psittaci: Update on an underestimated zoonotic agent. Pathog. Dis. 2015, 73, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borel, N.; Polkinghorne, A.; Pospischil, A. A review on chlamydial diseases in animals: Still a challenge for pathologists? Vet. Pathol. 2018, 55, 374–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zaręba-Marchewka, K.; Szymańska-Czerwińska, M.; Niemczuk, K. Chlamydiae—What’s new? J. Vet. Res. 2020, 64, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branley, J.; Bachmann, N.L.; Jelocnik, M.; Myers, G.S.; Polkinghorne, A. Australian human and parrot Chlamydia psittaci strains cluster within the highly virulent 6BC clade of this important zoonotic pathogen. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kemmerling, K.; Müller, U.; Mielenz, M.; Sauerwein, H. Chlamydophila species in dairy farms: Polymerase chain reaction prevalence, disease association, and risk factors identified in a cross-sectional study in western Germany. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 4347–4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenzko, H.; Moog, U.; Henning, K.; Lederbach, R.; Diller, R.; Menge, C.; Sachse, K.; Sprague, L.D. High frequency of chlamydial co-infections in clinically healthy sheep flocks. BMC Vet. Res. 2011, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lagae, S.; Kalmar, I.; Laroucau, K.; Vorimore, F.; Vanrompay, D. Emerging Chlamydia psittaci infections in chickens and examination of transmission to humans. J. Med. Microbiol. 2014, 63, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jelocnik, M.; Laurence, M.; Murdoch, F.R.; Polkinghorne, A. Detection of Chlamydiaceae in ocular swabs from Australian pre-export feedlot sheep. Aust. Vet. J. 2019, 97, 401–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelocnik, M.; Taylor-Brown, A.; O’Dea, C.; Anstey, S.; Bommana, S.; Masters, N.; Katouli, M.; Jenkins, C.; Polkinghorne, A. Detection of a range of genetically diverse chlamydiae in Australian domesticated and wild ungulates. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019, 66, 1132–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anstey, S.I.; Quigley, B.L.; Polkinghorne, A.; Jelocnik, M. Chlamydial infection and on-farm risk factors in dairy cattle herds in South East Queensland. Aust. Vet. J. 2019, 97, 505–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, H.S.; Martens, J.M.; Walder, K.; Segal, Y.; Berg, M.L.; Bennett, A.T.D. Species, sex and geographic variation in chlamydial prevalence in abundant wild Australian parrots. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amery-Gale, J.; Legione, A.R.; Marenda, M.S.; Owens, J.; Eden, P.A.; Konsak-Ilievski, B.M.; Whiteley, P.L.; Dobson, E.C.; Browne, E.A.; Slocombe, R.F.; et al. Surveillance for Chlamydia spp. with multilocus sequence typing analysis in wild and captive birds in Victoria Australia. J. Wildl. Dis. 2020, 56, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelocnik, M.; Jenkins, C.; O’Rourke, B.; Barnwell, J.; Polkinghorne, A. Molecular evidence to suggest pigeon-type Chlamydia psittaci in association with an equine foal loss. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018, 65, 911–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, C.; Jelocnik, M.; Micallef, M.L.; Galea, F.; Taylor–Brown, A.; Bogema, D.R.; Liu, M.; O’Rourke, B.; Chicken, C.; Carrick, J.; et al. An epizootic of Chlamydia psittaci equine reproductive loss associated with suspected spillover from native Australian parrots. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burnet, F.M. A note of the occurrence of fatal psittacosis in parrots living in the wild state. Med. J. Aust. 1939, 1, 545–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.; Doyle, B.; Branley, J.; Sheppeard, V.; Gabor, M.; Viney, K.; Quinn, H.; Janover, O.; McCready, M.; Heller, J. An outbreak of psittacosis at a veterinary school demonstrating a novel source of infection. One Health 2017, 3, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelocnik, M.; Branley, J.; Heller, J.; Raidal, S.; Alderson, S.; Galea, F.; Gabor, M.; Polkinghorne, A. Multilocus sequence typing identifies an avian-like Chlamydia psittaci strain involved in equine placentitis and associated with subsequent human psittacosis. Emerg. Microbes Inf. 2017, 6, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Anstey, S.; Lizárraga, D.; Nyari, S.; Chalmers, G.; Carrick, J.; Chicken, C.; Jenkins, C.; Perkins, N.; Timms, P.; Jelocnik, M. Epidemiology of Chlamydia psittaci infections in pregnant Thoroughbred mares and foals. Vet. J. 2021, 273, 105683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, R.; Sansom, F.M.; El-Hage, C.M.; Gilkerson, J.R.; Legione, A.R.; Devlin, J.M. A 25-year retrospective study of Chlamydia psittaci in association with equine reproductive loss in Australia. J. Med. Microbiol. 2021, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachse, K.; Laroucau, K.; Hotzel, H.; Schubert, E.; Ehricht, R.; Slickers, P. Genotyping of Chlamydophila psittaci using a new DNA microarray assay based on sequence analysis of ompA genes. BMC Microbiol. 2008, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pannekoek, Y.; Dickx, V.; Beeckman, D.S.; Jolley, K.A.; Keijzers, W.C.; Vretou, E.; Maiden, M.C.; Vanrompay, D.; van der Ende, A. Multi locus sequence typing of Chlamydia reveals an association between Chlamydia psittaci genotypes and host species. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e14179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorimore, F.; Aaziz, R.; de Barbeyrac, B.; Peuchant, O.; Szymańska-Czerwińska, M.; Herrmann, B.; Schnee, C.; Laroucau, K. A new SNP-based genotyping method for C. psittaci: Application to field samples for quick identification. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Read, T.D.; Joseph, S.J.; Didelot, X.; Liang, B.; Patel, L.; Dean, D. Comparative analysis of Chlamydia psittaci genomes reveals the recent emergence of a pathogenic lineage with a broad host range. mBio 2013, 4, e00604-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Akter, R.; Stent, A.W.; Sansom, F.M.; Gilkerson, J.R.; Burden, C.; Devlin, J.M.; Legione, A.R.; El-Hage, C.M. Chlamydia psittaci: A suspected cause of reproductive loss in three Victorian horses. Aust. Vet. J. 2020, 98, 570–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutherland, M.; Sarker, S.; Vaz, P.K.; Legione, A.R.; Devlin, J.M.; Macwhirter, P.L.; Whiteley, P.L.; Raidal, S.R. Disease surveillance in wild Victorian cacatuids reveals co-infection with multiple agents and detection of novel avian viruses. Vet. Microbiol. 2019, 235, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branley, J.M.; Weston, K.M.; England, J.; Dwyer, D.E.; Sorrell, T.C. Clinical features of endemic community-acquired psittacosis. New Microbes New infect. 2014, 2, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mattmann, P.; Marti, H.; Borel, N.; Jelocnik, M.; Albini, S.; Vogler, B.R. Chlamydiaceae in wild, feral and domestic pigeons in Switzerland and insight into population dynamics by Chlamydia psittaci multilocus sequence typing. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0226088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Favaroni, A.; Trinks, A.; Weber, M.; Hegemann, J.H.; Schnee, C. Pmp repertoires influence the different infectious potential of avian and mammalian Chlamydia psittaci strains. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 656209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, A.; Hanger, J.; Jelocnik, M.; Quigley, B.L.; Timms, P. Koala immunogenetics and chlamydial strain type are more directly involved in chlamydial disease progression in koalas from two south east Queensland koala populations than koala retrovirus subtypes. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, A.J.; Wells, K.; Giles, J.; Boyd, V.; Burroughs, A.; Edson, D.; Crameri, G.; Baker, M.L.; Field, H.; Wang, L.F.; et al. Synchronous shedding of multiple bat paramyxoviruses coincides with peak periods of Hendra virus spillover. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 1314–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Field, H.E. Evidence of Australian bat lyssavirus infection in diverse Australian bat taxa. Zoonoses Public Health 2018, 65, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barr, J.A.; Smith, C.; Marsh, G.A.; Field, H.; Wang, L.F. Evidence of bat origin for Menangle virus, a zoonotic paramyxovirus first isolated from diseased pigs. J. Gen. Virol. 2012, 93, 2590–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khusro, A.; Aarti, C.; Pliego, A.B.; Cipriano-Salazar, M. Hendra virus infection in horses: A review on emerging mystery paramyxovirus. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2020, 91, 103149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, K.M.; Wheeler, S.; Kerr, J.; Bennett, J.; Freeman, P.; Kohlhagen, J.; Peel, A.J.; Eby, P.; Merritt, T.; Housen, T.; et al. Hendra in the Hunter Valley. One Health 2020, 10, 100162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Water and Environment. National Flying-Fox Monitoring Viewer. Available online: https://www.environment.gov.au/webgis-framework/apps/ffc-wide/ffc-wide.jsf (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Fritschi, J.; Marti, H.; Seth-Smith, H.M.B.; Aeby, S.; Greub, G.; Meli, M.L.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Mühldorfer, K.; Stokar-Regenscheit, N.; Wiederkehr, D.; et al. Prevalence and phylogeny of Chlamydiae and hemotropic mycoplasma species in captive and free-living bats. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plowright, R.K.; Reaser, J.K.; Locke, H.; Woodley, S.J.; Patz, J.A.; Becker, D.J.; Oppler, G.; Hudson, P.J.; Tabor, G.M. Land use-induced spillover: A call to action to safeguard environmental, animal, and human health. Lancet Planet. 2021, 5, e237–e245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.; Taylor, K.; Lucas, R.M.; Merritt, T.; Chicken, C.; Heller, J.; Carrick, J.; Givney, R.; Durrheim, D.N. Challenges in using serological methods to explore historical transmission risk of Chlamydia psittaci in a workforce with high exposure to equine chlamydiosis. Commun. Dis. Intell. 2019, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.A.; Durrheim, D.; Heller, J.; O’Rourke, B.; Hope, K.; Merritt, T.; Freeman, P.; Chicken, C.; Carrick, J.; Branley, J.; et al. Equine chlamydiosis-An emerging infectious disease requiring a one health surveillance approach. Zoonoses Public Health 2018, 65, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. Available online: http://www9.health.gov.au/cda/source/cda-index.cfm (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Jelocnik, M.; Islam, M.M.; Madden, D.; Jenkins, C.; Branley, J.; Carver, S.; Polkinghorne, A. Development and evaluation of rapid novel isothermal amplification assays for important veterinary pathogens: Chlamydia psittaci and Chlamydia pecorum. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reaser, J.K.; Witt, A.; Tabor, G.M.; Hudson, P.J.; Plowright, R.K. Ecological countermeasures for preventing zoonotic disease outbreaks: When ecological restoration is a human health imperative. Restor. Ecol. 2021, e13357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Garine-Wichatitsky, M.; Binot, A.; Ward, J.; Caron, A.; Perrotton, A.; Ross, H.; Tran Quoc, H.; Valls-Fox, H.; Gordon, I.J.; Promburom, P.; et al. “Health in” and “Health of” social-ecological systems: A practical framework for the management of healthy and resilient agricultural and natural ecosystems. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 616328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madico, G.; Gursky, O.; Fairman, J.; Massari, P. Structural and immunological characterization of novel recombinant MOMP-based chlamydial antigens. Vaccines 2017, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pantchev, A.; Sting, R.; Bauerfeind, R.; Tyczka, J.; Sachse, K. Detection of all Chlamydophila and Chlamydia spp. of veterinary interest using species-specific real-time PCR assays. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2010, 33, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jelocnik, M.; Polkinghorne, A.; Pannekoek, Y. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) of Chlamydiales. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 2042, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geneious Prime 2020.2.4. Available online: https://www.geneious.com (accessed on 3 February 2021).

- Chlamydiales MLST Database. Available online: https://pubmlst.org/organisms/chlamydiales (accessed on 3 February 2021).

- BLASTn. Available online: https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Tonkin-Hill, G.; Lees, J.A.; Bentley, S.D.; Frost, S.D.W.; Corander, J. Fast hierarchical Bayesian analysis of population structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 5539–5549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).