The Evolutionary Trajectory of the Agile Concept Viewed from a Management Fashion Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Purpose

1.2. Structure

2. Research Approach

3. A Brief History of Agile

3.1. Origins and Emergence

3.2. Evolution

4. The Framing and Characteristics of Agile

4.1. Agile as a Management Concept

4.2. Label

4.3. Performance Improvements

4.4. Interpretive Space

4.5. Universality

5. The Supply-Side of Agile

5.1. Consulting Firms

5.2. Management Gurus

5.3. Conference and Seminar Organizers

5.4. Trainers and Coaches

5.5. Business Schools

5.6. Business and Social Media

6. The Demand-Side of Agile

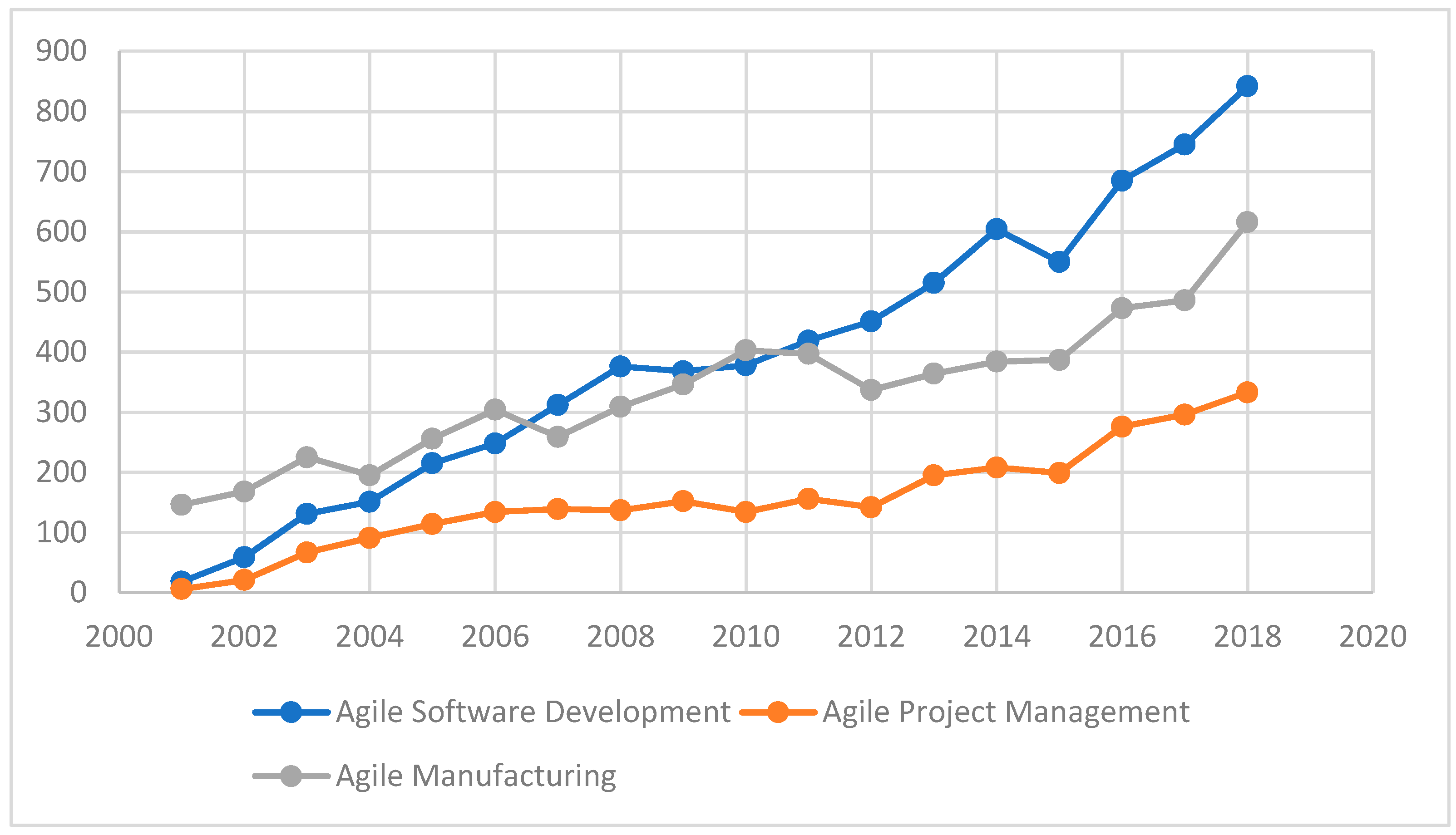

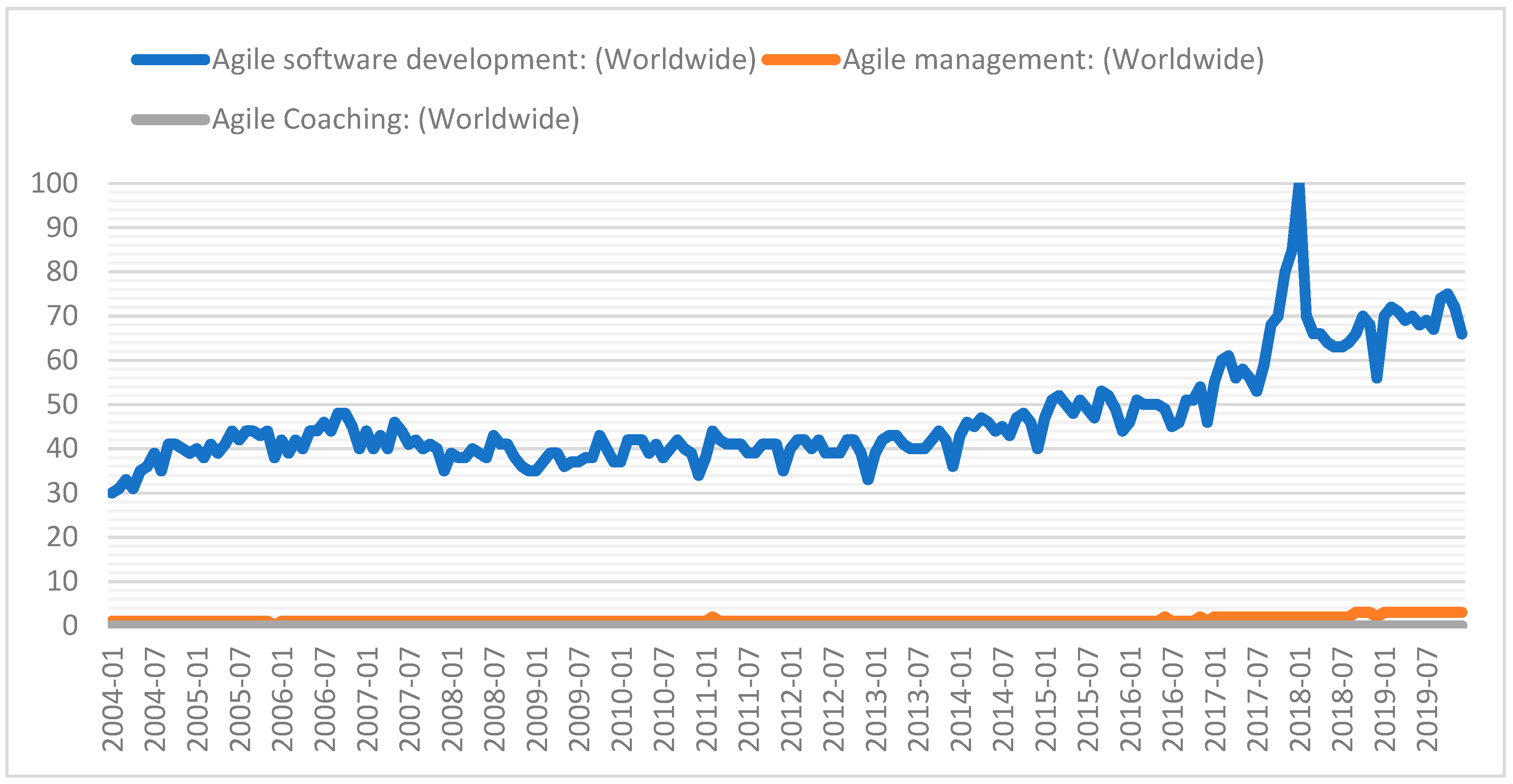

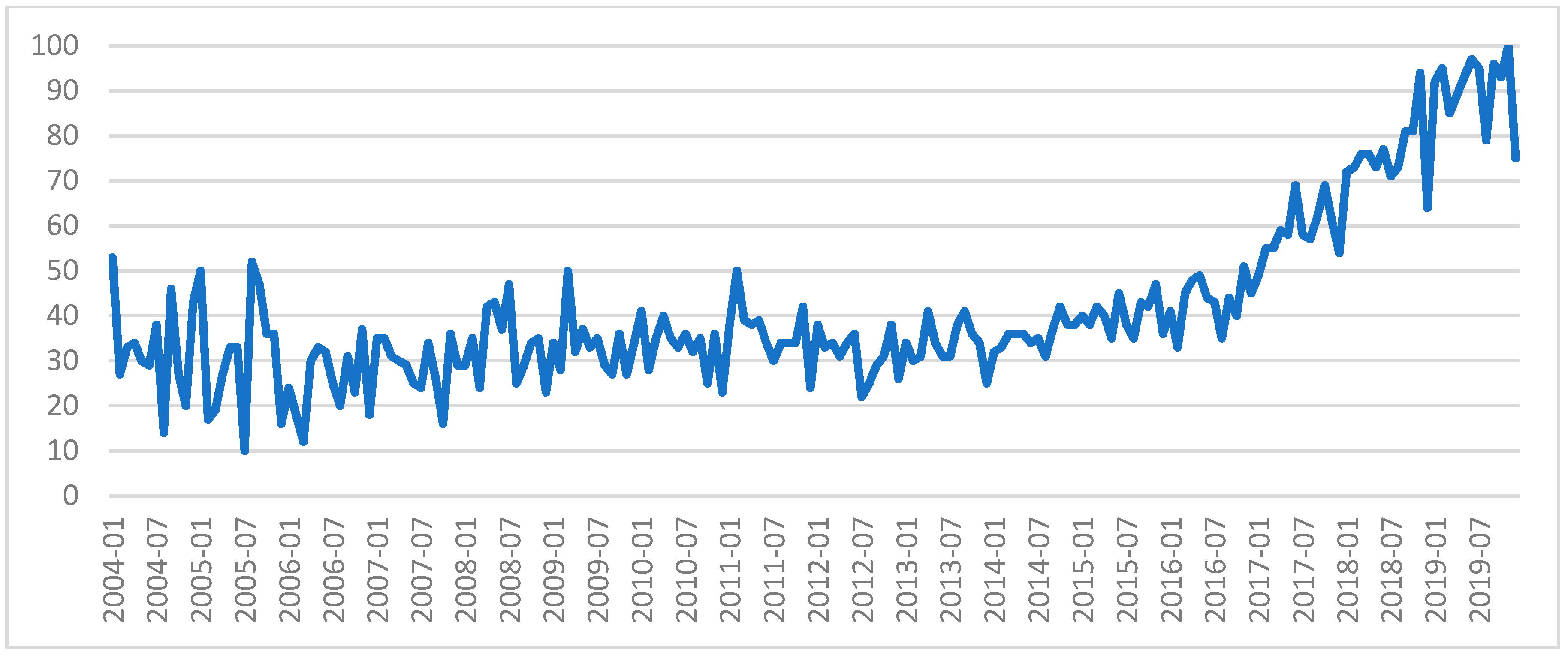

6.1. Interest

6.2. Adoption and Diffusion

6.3. Implementation

7. Discussion

7.1. Emergence

7.2. Evolution

7.3. Current Status and Likely Future Trajectory

8. Conclusions

8.1. Contributions

8.2. Limitations and Future Research

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbas, Noura, Andrew M. Gravell, and Gary B. Wills. 2008. Historical Roots of Agile Methods: Where Did “Agile Thinking” Come from? Paper Presented at the International Conference on Agile Processes and Extreme Programming in Software Engineering, Limerick, Ireland, June 10–14; Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamson, Eric. 1996. Management Fashion. Academy of Management Review 21: 254–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamson, Eric, and Alessandro Piazza. 2019. The Lifecycle of Management Ideas. In The Oxford Handbook of Management Ideas. Edited by Andrew Sturdy, Stefan Heusinkveld, Trish Reay and David Strang. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 42–67. [Google Scholar]

- Accardi-Petersen, Michelle. 2012. Agile Marketing. New York: Apress. [Google Scholar]

- Aghina, Wouter, Aaron De Smet, and Kirsten Weerda. 2015. Agility: It rhymes with stability. McKinsey Quarterly 51: 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Agile Alliance. 2020. What is Agile? Available online: https://www.agilealliance.org/agile101/ (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Agile Anon. 2016. 10 Ways Agile Feels Like a Fucking Cult. Available online: https://medium.com/@agileanon/10-ways-agile-feels-like-a-fucking-cult-8c1ed74b8882 (accessed on 20 December 2019).

- Ahlbäck, Karin, Clemens Fahrbach, Monica Murarka, and Olli Salo. 2017. How to Create an Agile Organization. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/how-to-create-an-agile-organization# (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Alexandre, J. H. de O., Marcelo L. M. Marinho, and Hermano P. de Moura. 2020. Agile governance theory: Operationalization. Innovations in Systems and Software Engineering 16: 3–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ambler, Scott, and Matthew Holitza. 2012. Agile for Dummies. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, Amit, Sahil Merchant, Arun Sunderraj, and Belkis Vasquez-McCall. 2019. Growing Your Own Agility Coaches to Adopt New Ways of Working. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/digital-mckinsey/our-insights/growing-your-own-agility-coaches-to-adopt-new-ways-of-working# (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Augustine, Sanjiv. 2005. Managing Agile Projects. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall PTR. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, Marcos, and Charles-Clemens Rüling. 2019. Business Media. In The Oxford Handbook of Management Ideas. Edited by Andrew Sturdy, Stefan Heusinkveld, Trish Reay and David Strang. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 195–215. [Google Scholar]

- Bazigos, Michael, Aaron De Smet, and Chris Gagnon. 2015. Why agility pays. McKinsey Quarterly 4: 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Kent, Mike Beedle, Arie Van Bennekum, Alistair Cockburn, Ward Cunningham, Martin Fowler, James Grenning, Jim Highsmith, Andrew Hunt, and Ron Jeffries. 2001. Manifesto for Agile Software Development. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Manifesto-for-Agile-Software-Development-Beck-Beedle/3edabb96a07765704f9c6a1a5542e39ac2df640c (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Benders, Jos, Robert-Jan van den Berg, and Mark van Bijsterveld. 1998. Hitch-hiking on a hype: Dutch consultants engineering re-engineering. Journal of Organizational Change Management 11: 201–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benders, Jos. 1999. Tricks and Trucks? A Case Study of Organization Concepts at Work. International Journal of Human Resource Management 10: 624–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benders, Jos, and Mark Van Bijsterveld. 2000. Leaning on lean: The reception of management fashion in Germany. New Technology, Work and Employment 15: 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benders, Jos, Jurriaan Nijholt, and Stefan Heusinkveld. 2007. Using print media indicators in management fashion research. Quality and Quantity 41: 815–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benders, J., Marlieke Van Grinsven, and J. Ingvaldsen. 2019. The persistence of management ideas; How framing keeps lean moving. In The Oxford Handbook of Management Ideas. Edited by A. Sturdy, H. Stefan Heusinkveld, Trish Rey and D. Strang. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 271–85. [Google Scholar]

- Benders, Jos, and Kees Van Veen. 2001. What’s in a Fashion? Interpretative Viability and Management Fashions. Organization 8: 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Nathan, and James Lemoine. 2014a. What VUCA really means for you. Harvard Business Review 92. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Nathan, and James Lemoine. 2014b. What a difference a word makes: Understanding threats to performance in a VUCA world. Business Horizons 57: 311–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, NMK, and Mohan Thite. 2019. Agile approach to e-HRM project management. e-HRM: Digital Approaches, Directions & Applications. [Google Scholar]

- Blomstrom, Duena. 2019a. Agile Versus DevOps. Who Cares? Forbes, February 4. [Google Scholar]

- Blomstrom, Duena. 2019b. Agile by Heart Not by McKinsey Power Point. Forbes, February 18. [Google Scholar]

- Blomstrom, Duena. 2019c. Agile—It’s Not Business, It’s Personal. Forbes. [Google Scholar]

- Blomstrom, Duena. 2019d. Agile Isn’t Out, You Are. Forbes, January 16. [Google Scholar]

- Blomstrom, Duena. 2019e. Agile Starts at The Top. Forbes, February 11. [Google Scholar]

- Blomstrom, Duena. 2019f. Leveraging Strong Agile Teams—Are You Being Heard? Forbes, January 22. [Google Scholar]

- Bogsnes, Bjarte. 2016. Beyond Budgeting and Agile. In Implementing Beyond Budgeting. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Bort, Suleika. 2015. Turning a management innovation into a management panacea: Management ideas, concepts, fashions, practices and theoretical concepts. In Handbook of Research on Management Ideas and Panaceas: Adaptation and Context. Edited by Anders Örtenblad. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, pp. 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Braam, G., and E. Nijssen. 2004. Performance effects of using the Balanced Scorecard: a note on the Dutch experience. Long Range Planning 37: 335–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braam, Geert J. M., Jos Benders, and Stefan Heusinkveld. 2007. The balanced scorecard in the Netherlands: An analysis of its evolution using print-media indicators. Journal of Organizational Change Management 20: 866–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briers, Michael, and Wai Fong Chua. 2001. The role of actor-networks and boundary objects in management accounting change: A field study of an implementation of activity-based costing. Accounting, Organizations and Society 26: 237–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byker, Martin. 2017. Is Agile a Religion? Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/agile-religion-martin-byker (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Cagle, Kurt. 2019a. The End of Agile. Forbes, August 23. [Google Scholar]

- Cagle, Kurt. 2019b. The End of Agile: A Rebuttal. Forbes, August 28. [Google Scholar]

- Cagle, Kurt. 2019c. Beyond Agile: The Studio Model. Forbes. [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos, Sara. 2019. Campbell Goes Agile, From Soup to Snacks. Wall Street Journal, July 8. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Hyunyoung, and Hal Varian. 2012. Predicting the present with google trends. Economic Record 88: 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, Clayton M. 2006. The ongoing process of building a theory of disruption. Journal of Product Innovation Management 23: 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, Martin. 2000. The agile supply chain: Competing in volatile markets. Industrial Marketing Management 29: 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, Martin, Robert Lowson, and Helen Peck. 2004. Creating agile supply chains in the fashion industry. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 32: 367–76. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Timothy. 2004. The fashion of management fashion: A surge too far? Organization 11: 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cluley, Robert. 2013. What Makes a Management Buzzword Buzz? Organization Studies 34: 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, Jeffrey L., and Zhichuan Frank Li. 2019a. An Empirical Assessment of Empirical Corporate Finance. Available at SSRN 1787143. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1787143 (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Coles, Jeffrey L., and Zhichuan Frank Li. 2019b. Managerial attributes, incentives, and performance. SSRN Working Paper. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collabnet Versionone. 2018. 12th State of Agile Report. Atlanta: Collabnet VersionOne. Available online: https://www.stateofagile.com/#ufh-c-473508-state-of-agile-report (accessed on 15 December 2019).

- Collins, David. 2000. Management Fads and Buzzwords. Critical-Practical Perspectives. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, David. 2019. Management’s Gurus. In The Oxford Handbook of Management Ideas. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 216. [Google Scholar]

- Cram, W. Alec, and Sue Newell. 2016. Mindful revolution or mindless trend? Examining agile development as a management fashion. European Journal of Information Systems 25: 154–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, Robert J., and David Strang. 2006. When fashion is fleeting: Transitory collective beliefs and the dynamics of TQM consulting. Academy of Management Journal 49: 215–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Nigel. 2019. Agile Deserves the Hype, But It Can Also Fail: How to Avoid the Pitfalls. Forbes, July 2. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte. 2017. Deloitte Global Human Capital Trends 2017. Rewriting the Rules for the Digital Age. London: Deloitte University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2012. Is Apple Truly ‘Agile’? Forbes, February 3. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2015a. Surprise: Microsoft Is Agile. Forbes, October 27. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2015b. Is Agile Just Another Management Fad? Forbes, June 25. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2015c. Updating the Agile Manifesto. Strategy & Leadership 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, Stephen. 2015d. How Agile and Zara Are Transforming the US Fashion Industry. Forbes, March 13. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2015e. How to make the whole organization Agile. Strategy & Leadership 43: 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, Stephen. 2016a. Explaining Agile. Forbes, September 8. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2016b. Understanding the three laws of Agile. Strategy & Leadership 44: 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, Stephen. 2016c. HBR’s embrace of agile. Harvard Business Review 94: 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2017a. The age of Agile. Strategy & Leadership 45: 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, Stephen. 2017b. The next frontier for Agile: Strategic management. Strategy & Leadership 45: 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2018a. The 12 Stages of the Agile Transformation Journey. Forbes, November 4. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2018b. What The C-Suite Must Do to Make the Whole Firm Agile. Forbes, September 9. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2018c. Why Agile Is Eating the World. Forbes, January 2. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2018d. Ten Agile axioms that make conventional managers anxious. Strategy & Leadership 46: 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, Stephen. 2018e. The role of the C-suite in Agile transformation: The case of Amazon. Strategy & Leadership 46: 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, Stephen. 2018f. Ten Agile Axioms That Make Managers Anxious. Forbes, June 17. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2018g. The emergence of Agile people management. Strategy & Leadership 46: 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2018h. How major corporations are making sense of Agile. Strategy & Leadership 46: 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, Stephen. 2018i. Why Finding the Real Meaning of Agile Is Hard. Forbes, September 16. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2018j. The Age of Agile: How Smart Companies Are Transforming the Way Work Gets Done. New York: Amacom. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2018k. Agile Is Not Just Another Management Fad. Forbes, July 30. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Steve. 2018l. Succeeding in an increasingly Agile world. Strategy & Leadership 46: 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, Stephen. 2019a. World Agility Forum Celebrates Excellence, Flays Fake Agile. Forbes, October 13. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2019b. HR Reinvents the Organization. Forbes, October 4. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2019c. The Five Biggest Challenges Facing Agile. Forbes, September 8. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2019d. How Mapping the Agile Transformation Journey Points the Way to Continuous Innovation. Forbes, March 17. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2019e. Post-bureaucratic management goes global. Strategy & Leadership 47: 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2019f. The ten stages of the Agile transformation journey. Strategy & Leadership 47: 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2019g. The Irresistible Rise of Agile: A Paradigm Shift in Management. Forbes, February 20. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2019h. Lessons learned from mapping successful and unsuccessful Agile transformation journeys. Strategy & Leadership 47: 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2019i. Recognizing Excellence in Agility: The World Agility Forum. Forbes, September 1. [Google Scholar]

- Diegmann, Phil, Tim Dreesen, BjÃrn Binzer, and Christoph Rosenkranz. 2018. Journey Towards Agility: Three Decades of Research on Agile Information Systems Development. Paper Presented at the International Conference on Information Systems, San Francisco, CA, USA, December 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dierdorf, Scott. 2019. Becoming Agile. Tiffany Taylor 410. [Google Scholar]

- Dingsøyr, Torgeir, Sridhar Nerur, VenuGopal Balijepally, and Nils Brede Moe. 2012. A Decade of Agile Methodologies: Towards Explaining Agile Software Development. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Doz, Yves, and Mikko Kosonen. 2008. The dynamics of strategic agility: Nokia’s rollercoaster experience. California Management Review 50: 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doz, Yves L., and Mikko Kosonen. 2010. Embedding strategic agility: A leadership agenda for accelerating business model renewal. Long Range Planning 43: 370–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dybå, Tore, and Torgeir Dingsøyr. 2008. Empirical studies of agile software development: A systematic review. Information and Software Technology 50: 833–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engwall, Lars, and Linda Wedlin. 2019. Business Studies and Management Ideas. In Oxford Handbook of Management Ideas. Edited by Andrew Sturdy, Stefan Heusinkveld, Trish Reay and David Strang. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Felizardo, Katia Romero, Emilia Mendes, Marcos Kalinowski, Érica Ferreira Souza, and Nandamudi L Vijaykumar. 2016. Using forward snowballing to update systematic reviews in software engineering. Paper Presented at the 10th ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement, Ciudad Real, Spain, September 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes Insights. 2018. Management in the Age of Agile. Forbes, November 8. [Google Scholar]

- George, Joey F., Kevin Scheibe, Anthony M. Townsend, and Brian Mennecke. 2018. The amorphous nature of agile: No one size fits all. Journal of Systems and Information Technology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, John R., Si Li, and Jiaping Qiu. 2012. Managerial attributes and executive compensation. The Review of Financial Studies 25: 144–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gren, Lucas, and Per Lenberg. 2019. Agility is responsiveness to change: An essential definition. arXiv arXiv:1909.10082. [Google Scholar]

- Grint, Keith. 1997. TQM, BPR, JIT, BSCs and TLAs: Managerial waves or drownings? Management Decision 35: 731–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, Angappa. 1998. Agile manufacturing: Enablers and an implementation framework. International Journal of Production Research 36: 1223–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, Angappa. 2001. Agile Manufacturing: The 21st Century Competitive Strategy. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Hass, Kathleen B. 2007. The blending of traditional and agile project management. PM World Today 9: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hazzan, Orit, and Yael Dubinsky. 2014. Agile Anywhere: Essays on Agile Projects and Beyond. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Heiligtag, S., D. Luczak, and E. Windhagen. 2015. Agility lessons from utilities. McKinsey Quarterly. [Google Scholar]

- Heusinkveld, S., and J. Benders. 2012. Consultants and organization concepts. In The Oxford Handbook of Management Consulting. Edited by M. Kipping and T. Clark. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 267–84. [Google Scholar]

- Heusinkveld, Stefan. 2013. The Management Idea Factory: Innovation and Commodification in Management Consulting. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hindle, Tim. 2008. Guide to Management Ideas and Gurus. London: The Economist in Assocation with Profile Books Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Hoda, Rashina, Norsaremah Salleh, and John Grundy. 2018. The rise and evolution of agile software development. IEEE Software 35: 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holweg, Matthias. 2007. The genealogy of lean production. Journal of Operations Management 25: 420–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horney, Nick, Bill Pasmore, and Tom O’Shea. 2010. Leadership agility: A business imperative for a VUCA world. Human Resource Planning 33: 34. [Google Scholar]

- Hosking, Alan. 2018. Agile leaders balance speed and stability. HR Future 2018: 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Huczynski, Andrzej. 1993. Management Gurus: What Makes Them and How to Become One. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Huczynski, Andrzej A. 1992. Management Guru Ideas and the 12 Secrets of their Success. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 13: 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Mostaque, and A. Gunasekaran. 2002. Non-financial management accounting measures in Finnish financial institutions. European Business Review 14: 210–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, Samireh, and Claes Wohlin. 2012. Systematic literature studies: Database searches vs. backward snowballing. Paper Presented at the 2012 ACM-IEEE International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement, Lund, Sweden, September 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Mark W. 2010. Seizing the White Space: Business Model Innovation for Growth and Renewal. Brighton: Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Dong-II, and Won-Hee Lee. 2016. Crossing the management fashion border: The adoption of business process reengineering services by management consultants offering total quality management services in the United States, 1992–2004. Journal of Management & Organization, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Nicole, and Alfred Kieser. 2012. Consultants in the Management Fashion Arena. In The Oxford Handbook of Management Consulting. Edited by Matthias Kipping and Timothy Clark. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 327–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kaarbøe, Katarina, Paul N. Gooderham, and Hanne Nørreklit. 2013. Managing in Dynamic Business Environments: Between Control and Autonomy. Trotterham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, M. 2016. Agile Is Dead. Available online: http://www.linkedin.com/pulse/agile-dead-matthew-kern (accessed on 20 December 2019).

- Kieser, Alfred. 1997. Rhetoric and myth in management fashion. Organization 4: 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieser, Alfred. 2002. Managers as Marionettes? Using Fashion Theories to Explain the Success of Consultancies. In Management Consulting—Emergence and Dynamics of a Knowledge Industry. Edited by Matthias Kipping and Lars Engwall. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W. Chan, and Renée Mauborgne. 2005. Blue Ocean Strategy: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W. Chan, and Renée Mauborgne. 2017. Blue Ocean Shift: Beyond Competing—Proven Steps to Inspire Confidence and Seize New Growth. New York: Hachette Books. [Google Scholar]

- Klincewicz, Krzysztof. 2006. Management Fashions: Turning Best-Selling Ideas into Objects and Institutions. Praxiology: The International Annual of Practical Philosophy and Methodology. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, vol. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Kotter, John P. 2014. Accelerate: Building Strategic Agility for a Faster-Moving World. Harvard: Harvard Business Review Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kruchten, Philippe. 2019. The end of agile as we know it. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Software and System Processes. Montreal: IEEE Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kupersmith, Kupe. 2011. Agile Is a Fad. July 4. Available online: http://www. batimes. com/kupe-kupersmith/agile-is-afad.html (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Laanti, Maarit, Rami Sirkiä, and Mirette Kangas. 2015. Agile portfolio management at Finnish broadcasting company Yle. Scientific Workshop Proceedings of the XP2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layton, Mark C., and Steven J. Ostermiller. 2017. Agile Project Management for Dummies. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Marianne W., Constantine Andriopoulos, and Wendy K. Smith. 2014. Paradoxical leadership to enable strategic agility. California Management Review 56: 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longbottom, David. 2000. Benchmarking in the UK: An empirical study of practitioners and academics. Benchmarking: An International Journal 7: 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias-Lizaso, Gloria, and Kiko Thiel. 2006. Building a nimble organization: A McKinsey global survey. The McKinsey Quarterly-Online Survey, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, Dag, and Kåre Slåtten. 2013. The Role of the Management Fashion Arena in the Cross-National Diffusion of Management Concepts: The Case of the Balanced Scorecard in the Scandinavian Countries. Administrative Sciences 3: 110–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, Dag Øivind, and Tonny Stenheim. 2013. Doing research on ‘management fashions’: Methodological challenges and opportunities. Problems and Perspectives in Management 11: 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, Dag Øivind. 2014. How do managers encounter fashionable management concepts? A study of balanced scorecard adopters in Scandinavia. International Journal of Management Concepts and Philosophy 8: 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, Dag Øivind, and Kåre Slåtten. 2015a. The Balanced Scorecard: Fashion or Virus? Administrative Sciences 5: 90–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, Dag Øivind, and Kåre Slåtten. 2015b. Social media and management fashions. Cogent Business & Management 2: 1122256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, Dag Øivind. 2016a. SWOT Analysis: A Management Fashion Perspective. International Journal of Business Research 16: 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, Dag Øivind. 2016b. Using Google Trends in management fashion research: A short note. European Journal of Management 16: 111–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason-Jones, Rachel, Ben Naylor, and Denis R. Towill. 2000. Engineering the leagile supply chain. International Journal of Agile Management Systems 2: 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medinilla, Ángel. 2012a. Agile Management: Leadership in an Agile Environment. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Medinilla, Ángel. 2012b. Lean and Agile in a Nutshell. In Agile Management: Leadership in an Agile Environment. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 19–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mergel, Ines. 2016. Agile innovation management in government: A research agenda. Government Information Quarterly 33: 516–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergel, Ines, Yiwei Gong, and John Bertot. 2018. Agile Government: Systematic Literature Review and Future Research. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Bertrand. 2014. Agile!: The Good, the Hype and the Ugly. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Pamela. 2016. Agility Shift: Creating Agile and Effective Leaders, Teams, and Organizations. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mezick, Daniel. 2016. The Agile Industrial Complex. Available online: http://newtechusa.net/aic/ (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Millar, Carla CJM, Olaf Groth, and John F. Mahon. 2018. Management Innovation in a VUCA World: Challenges and Recommendations. California Management Review 61: 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Jed. 2017. An ethnography of multiplicity: Wittgenstein and plurality in the organisation. Paper Presented at the 12th Annual International Ethnography Symposium, Manchester, UK, August 29–September 1. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, Alan, and Robin Wensley. 1991. Boxing up or boxed in?: A short history of the Boston Consulting Group share/growth matrix. Journal of Marketing Management 7: 105–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoletti, Bernardo. 2018. Introduction to Agile Procurement Systems. In Agile Procurement: Volume II: Designing and Implementing a Digital Transformation. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Nijholt, J. J., and J. Benders. 2007. Coevolution in management fashions. Group & Organization Management 32: 628–52. [Google Scholar]

- Nyce, Caroline Mimbs. 2017. The Winter Getaway That Turned the Software World Upside Down: How a group of programming rebels started a global movement. The Atlantic, December 8. [Google Scholar]

- Perkmann, Markus, and André Spicer. 2008. How are Management Fashions Institutionalized? The Role of Institutional Work. Human Relations 61: 811–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, Alessandro, and Eric Abrahamson. 2020. Fads and Fashions in Management Practices: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. International Journal of Management Reviews. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poolton, Jenny, Hossam S. Ismail, Iain R. Reid, and Ivan C. Arokiam. 2006. Agile marketing for the manufacturing-based SME. Marketing Intelligence & Planning 24: 681–93. [Google Scholar]

- Prange, Christiane, and Loizos Heracleous. 2018a. Agility.X: How Organizations Thrive in Unpredictable Times. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prange, Christiane, and Loizos Heracleous. 2018b. Introduction. In Agility.X: How Organizations Thrive in Unpredictable Times. Edited by Christiane Prange and Loizos Heracleous. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rigby, Darrell, Jeff Sutherland, and Hirotaka Takeuchi. 2016a. The Secret History of Agile Innovation. Harvard Business Review, April 20. [Google Scholar]

- Rigby, Darrell, Jeff Sutherland, and Hirotaka Takeuchi. 2016b. Embracing Agile. Harvard Business Review, May. [Google Scholar]

- Rigby, Darrell, and Barbara Bilodeau. 2018. Management Tools & Trends.

- Rigby, Darrell K., Steve Berez, Greg Caimi, and Andrew Noble. 2015. Agile Innovation. San Francisco: Bain & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Røvik, Kjell Arne. 1998. Moderne Organisasjoner. Oslo: Fagbokforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Røvik, Kjell Arne. 2002. The secrets of the winners: Management ideas that flow. In The Expansion of Management Knowledge: Carriers, Ideas and Sources. Edited by K. Sahlin-Andersson and L. Engwall. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 113–44. [Google Scholar]

- Røvik, Kjell Arne. 2011. From Fashion to Virus: An Alternative Theory of Organizations’ Handling of Management Ideas. Organization Studies 32: 631–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlin-Andersson, Kerstin, and Lars Engwall. 2002. Carriers, Flows, and Sources of Management Knowledge. In The Expansion of Management Knowledge. Edited by Kerstin Sahlin-Andersson and Lars Engwall. Stanford: Stanford Business Books–Stanford University Press, pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sahota, Michael, Bjarte Bogsnes, Jaana Nyfjord, Jorgen Hesselberg, and Almir Drugovic. 2014. Beyond Budgeting: A Proven Governance System Compatible with Agile Culture. Available online: http://bbrt.co.uk/bbfiles/BeyondBudgetingAgileWhitePaper_2014.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Schwarz, Colleen. 2015. A review of management history from 2010–2014 utilizing a thematic analysis approach. Journal of Management History 21: 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, Jim. 2013. Agile HR delivery. Workforce Solutions Review 4: 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Shellenbarger, Sue. 2019. Are You Agile Enough for Agile Management. Wall Street Journal, August 12. [Google Scholar]

- Sibbet, David. 1997. 75 years of management ideas and practice 1922–1997. Harvard Business Review 75: 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sirkiä, Rami, and Maarit Laanti. 2013. Lean and agile financial planning. White Paper 24: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sirkiä, Rami, and Maarit Laanti. 2015. Adaptive Finance and Control: Combining Lean, Agile, and Beyond Budgeting for Financial and Organizational Flexibility. Paper Presented at the 2015 48th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Kauai, HI, USA, January 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Skeels, Jack. 2018. Will Management Succeed at Killing Agile? And can true leadership save it? June 24. [Google Scholar]

- Soe, Ralf-Martin, and Wolfgang Drechsler. 2018. Agile local governments: Experimentation before implementation. Government Information Quarterly 35: 323–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stormi, Kati Tuulikki, Teemu Laine, and Tuomas Korhonen. 2019. Agile performance measurement system development: An answer to the need for adaptability? Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change 15: 231–56. [Google Scholar]

- Strang, David, and Christian Wittrock. 2019. Methods for the Study of Management Ideas. In Oxford Handbook of Management Ideas. Edited by Andrew Sturdy, Stefan Heusinkveld, Trish Reay and D. Strang. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 86–103. [Google Scholar]

- Sturdy, Andrew. 2004. The adoption of management ideas and practices. Theoretical perspectives and possibilities. Management Learning 35: 155–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturdy, Andrew, Stefan Heusinkveld, Trish Reay, and David Strang. 2019. The Oxford Handbook of Management Ideas. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sull, Donald. 2010. Competing through organizational agility. McKinsey Quarterly 1. [Google Scholar]

- Swan, Jacky. 2004. Reply to Clark: The fashion of management fashion. Organization 11: 307–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørhaug, Tian. 2016. Gull, Arbeid og Galskap: Penger og Objekttrøbbel. Fagbokforlaget Vigmostad og Bjørke. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget Vigmostad og Bjørke. [Google Scholar]

- Taipaleenmäki, Jani. 2017. Towards Agile Management Accounting: A Research Note on Accounting Agility. In A Dean, a Scholar, a Friend: Texts in Appreciation of Markus Granlund. Edited by Kari Lukka. Turku: University of Turku, pp. 175–204. [Google Scholar]

- Taleb, Nassim Nicholas. 2007. The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- ten Bos, René. 2000. Fashion and Utopia in Management Thinking. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- The Economist. 2018. The fashion for agile management is spreading. Cirrus, July 5. [Google Scholar]

- Thedvall, Renita. 2018. Plans for Altering Work: Fitting Kids into Car-Management Documents in a Swedish Preschool. Anthropologica 60: 236–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckman, Alan. 1994. The yellow brick road: Total quality management and the restructuring of organizational culture. Organization Studies 15: 727–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twidale, Michael, and Preben Hansen. 2019. Agile research. First Monday, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, Dave, and Arthur Yeung. 2019. Agility: The new response to dynamic change. Strategic HR Review 18: 161–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versionone. 2017. 11st State of Agile Report. Atlanta: Versionone. Available online: https://www.stateofagile.com/#ufh-i-338501295-11th-annual-state-of-agile-report/473508 (accessed on 20 December 2019).

- Weiderstål, Robin, and Isak Nilsson Johansson. 2018. Translating Agile: An Ethnographic Study of SEB Pension & Försäkring. Available online: http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1221071&dswid=-9003 (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Whiteley, Andrew, Julien Pollack, and Petr Matous. 2019. A Structured Review of the History of Agile Methods and Iterative Approaches to Management. Academy of Management Proceedings. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, Adrian, and Hugh Willmott. 1995. Making Quality Critical: New Perspectives on Organizational Change. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, Adrian, and Hugh Willmott. 1996. Quality management, problems and pitfalls: A critical perspective. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 13: 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Wischweh, Jan. 2019. The Agile Crisis—A Primer. Available online: https://blog.usejournal.com/the-agile-crisis-2016-9fb1c2f52af5 (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Wittrock, Christian. 2015. Reembedding Lean: The Japanese Cultural and Religious Context of a World Changing Management Concept. International Journal of Sociology 45: 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlin, Claes. 2014. Guidelines for snowballing in systematic literature studies and a replication in software engineering. Paper Presented at the 18th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, London, UK, May 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yip, Jason. 2016. What do you mean when you say “Agile”? June 19. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, Yahaya Y., Mansoor Sarhadi, and Angappa Gunasekaran. 1999. Agile manufacturing: The drivers, concepts and attributes. International Journal of Production Economics 62: 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örtenblad, Anders. 2010. Who needs contingency approaches and guidelines in order to adapt vague management ideas? International Journal of Learning and Change 4: 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 |

| Neologism | Reference |

|---|---|

| Agile Manufacturing | Gunasekaran (1998, 2001), Hussain and Gunasekaran (2002), Yusuf et al. (1999) |

| Agile Project Management | Hass (2007), Layton and Ostermiller (2017) |

| Agile Supply Chain | Christopher (2000), Christopher et al. (2004) |

| Agile Procurement | Nicoletti (2018) |

| Agile Management Accounting | Taipaleenmäki (2017) |

| Agile Portfolio Management | Laanti et al. (2015) |

| Agile Financial Planning | Sirkiä and Laanti (2013) |

| Agile Finance & Control | Sirkiä and Laanti (2015) |

| Agile Performance Measurement System | Stormi et al. (2019) |

| Agile HR | Bhatta and Thite (2019), Scully (2013) |

| Agile People Management | Denning (2018k) |

| Agile Governance | Alexandre et al. (2020) |

| Agile Marketing | Accardi-Petersen (2012), Poolton et al. (2006) |

| Agile Research | Twidale and Hansen (2019) |

| Agile Innovation | Rigby et al. (2015) |

| Agile Innovation Management in Government | Mergel (2016) |

| Agile Government | Mergel et al. (2018) |

| Agile Local Governments | Soe and Drechsler (2018) |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Madsen, D.Ø. The Evolutionary Trajectory of the Agile Concept Viewed from a Management Fashion Perspective. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9050069

Madsen DØ. The Evolutionary Trajectory of the Agile Concept Viewed from a Management Fashion Perspective. Social Sciences. 2020; 9(5):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9050069

Chicago/Turabian StyleMadsen, Dag Øivind. 2020. "The Evolutionary Trajectory of the Agile Concept Viewed from a Management Fashion Perspective" Social Sciences 9, no. 5: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9050069

APA StyleMadsen, D. Ø. (2020). The Evolutionary Trajectory of the Agile Concept Viewed from a Management Fashion Perspective. Social Sciences, 9(5), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9050069