Abstract

There has recently been increased interest in the potential for formal and informal networks to aid interventions with biologic families in helping them achieve reunification in the context of the child protection system. When group support is provided to families, the creation of a network of social support seems to be a consequence. The article analyzes the conceptualization of social support in order to create social support networks and the benefits on the intervention with families in the framework of the child protection system through a systematic review. From a wide search 4348 documents, finally 14 articles were included in the reviews. Results show that social support is considered a process by which social resources are provided from formal (professional services and programs associated with those services in any off the protection, health of educational systems) and informal (extended family, friends, neighbors and acquaintances) networks, allowing the families to confront daily moments as well as in crisis situations. This social support is related to emotional, psychological, physical, instrumental, material and information support that allow families to face their difficulties. Formal and informal networks of child protection systems contribute to social support, resilience, consolidation of learning and the assistance of families to social intervention programs.

1. Introduction

Family reunification in child protection systems refers to the experiences a child has when they return to live with their family of origin after a temporary separation as a result of a measure of protection of foster care and/or residential foster care (Balsells et al. 2016a). However, the process is more complex than this definition, since it is important to understand reunification as the set of considerations, strategies and actions necessary to achieve the return of the child to the home and family safely (Nager 2010), which involves resolving conflict situations, maintaining the emotional ties of the children and their parents, improving their parental skills and, especially, ensuring that the family provides a stable, safe and affectionate environment.

To achieve stable family reunification, a series of interventions and resources are launched, such as the provision of economic, social, school, home or even therapeutic support if there is a problem of mental health or substance addiction, in addition to a possible intervention of socio-educational character aimed at improving parental skills (Balsells et al. 2016a). Facilitating birth parents’ access to the full continuum of services and integrating them into the overall case plan is crucial to resolving concerns to ensure the child’s safety and eventual reunification (Fernandez 2014).

In this way, programs that seek to support the specific parental competencies that families have to develop in a process of reception and reunification represent a necessary strategy for the improvement in the exercise of parenthood (Child Welfare Information Gateway 2011).

The group methodology offers professionals and families a new way of addressing learning situations in a more satisfactory and effective way (Amorós et al. 2009). This intervention format offers important opportunities to help families through the significance of their strengths, to reduce stigma and the sense of social isolation, in addition to increasing the training and social support of families (Balsells et al. 2016a). In the same way, group work allows the creation of support dynamics among group members that help fathers and mothers feel more valued and more comfortable (Balsells 2006).

These support dynamics can involve the creation of a social support network, understood as the process by which social resources are endowed from formal and informal networks in everyday moments, as well as in crisis situations. This social support is related to emotional, psychological, physical, instrumental, material and information support that promote overcoming the difficulties families encounter (Lin and Ensel 1989). The benefits of having or receiving support from various sources are associated with the prevention of relapses, the strengthening of the capacities of the family system and the maintenance and improvement of family functioning (Fuentes-Peláez et al. 2014).

In the welfare system formal networks connect with informal ones to cause effects on those targeted. Agents of the formal network are understood to be those institutions and services in charge of the social and educational intervention with families, as well as those that do paid professional work within those institutions, including everyone from the professionals working directly on the intervention to those working on management of it, offering services of coordination and organization of the service and as supporting agents of the informal network, families, groups, communities or family community or social surroundings of the people receiving the social intervention.

In terms of building resilience, social support enhances well-being and health, as social relationships provide the individual with a set of identities and positive evaluations (Fuentes-Peláez, et al. 2014). In this sense, combined social resources, formal and informal support networks, help families to cope from day to day or in crisis situations (Lin and Ensel 1989).

These social support networks, whether formal or informal, represent an important resilience factor for families in situations of social vulnerability (Lietz and Strength 2011), as they help to deal with stressful life situations (Armstrong et al. 2005), improve well-being and health, reduce the rates of depression and emotional distress after traumatic events, while providing a different perspective on the intervention of professionals working in the child protection system (Lietz et al. 2011).

2. Methods

This review aims to know the elements of the group methodology that promote social support in the development of group intervention programs in the protection system and child welfare.

2.1. Search Strategy

In order to respond to this objective, we decided to do a systematic review by searching in different databases. Anglo–Saxon, Hispanic and French databases were selected (PsycINFO, Educational Resource Information Center—ERIC, Web of Science, Scopus, Dialnet and Francis). However, no articles were selected from the Hispanic and French databases. The following keywords were used to perform the search (a) group intervention, (b) social support, (c) social network and family reunification. The Table 1 shows the results of the search. It describes the results by the databases and the keywords used.

Table 1.

Results of the search.

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

To be included in the review, studies had to be published after the year 2000 in a journal with impact factor. On the main theme, the articles had to refer to group intervention. It was decided to exclude those articles in which the group intervention was therapeutic. It was decided to include only the articles that studied the group intervention with families or children who were in a vulnerable situation or in the child protection system.

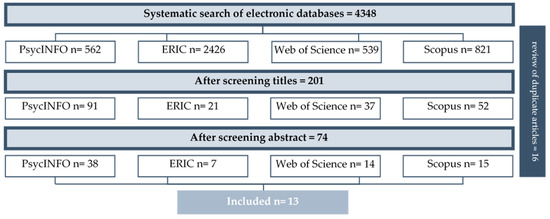

Figure 1 reflects the articles selection process. The total search involved reviewing more than four thousand article titles, of which 201 were selected. After reviewing the abstracts, we selected 74 articles to read completely. The final selection is composed of 13 articles. Finally, we decided to include one more article that was suggested by the experts.

Figure 1.

Selection process.

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Studies Used in the Review

Table 2 summarizes the principal characteristics and results of the selected studies. Specifically, the country in which the research is carried out, the objective and methodology of the article, the sample and the main results obtained are presented.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the studies.

3.2. Data from Studies Selected for Systematic Review

The authors identify different elements of group intervention that favor the possible creation of an informal support network. It was decided to divide these elements into five large groups: (1) Changes in participants, (2) Changes in the development and results of the program, (3) Changes in the perception of formal and informal support, (4) Desire to offer support to other families in the same situation and (5) Evaluation. Table 3 summarizes the elements identified according to the emerging categories mentioned.

Table 3.

Elements identified in the selected articles.

4. Discussion

In the cases where support networks have been built, research shows that the families expressed significant reductions in stress levels and social isolation (McDonald et al. 2009). Participation in group intervention programs also appeared to alleviate feelings of guilt and self-blame associate to the situation of neglect or abuse that originates the enter in the child protection system. The support group provided a sense of having something in common with others (Berrick et al. 2011; Jones and Bryant-Waugh 2012).

In reference to changes in the development and results of the program, Karjalainena et al. (2019) alluded to the effectiveness of the intervention being likely to be associated with the context of the group intervention.

Parents stated that the other families were capable of helping them because they “had been there” and could fully understand and appreciate the parents’ experiences of having their child removed (Jones and Bryant-Waugh 2012). They also stated that communication was made easy by its clarity, availability and frequency. In this sense, families suggested that the opportunity to talk with others was more helpful than any specific topic (Berrick et al. 2011). In some cases, parents transformed the program into a forum of informal support where they could share experiences with those in a similar situation. The bonding of the families who participated was a key factor of the program (Fuentes-Peláez et al. 2014). Finally, studies show that collaborative learning among group members seems to have improved the effectiveness of socio-educational intervention programs (Wei et al. 2012; Aschbrenner et al. 2016).

One of the results is that the families change their perception of formal and informal support after having participated in the group intervention programs. The families are able to identify instrumental and emotional support provided by other families (Berrick et al. 2011). On the other hand, families refer to the informal external support they receive as extended family, friends and neighbors, etc. Families also highlighted the importance of intrafamilial social support, referring to the encouragement and practical help that comes from the family unit (McDonald et al. 2009). Families taking part in group programs had a better understanding of formal support (Fuentes-Peláez et al. 2014). They were able to ask for help when they need it and to seek support regularly. They also increased the use of those resources of support that were rarely used at the beginning of the program: such as police, neighborhood associations, child protection services and other institutions (Lietz et al. 2011; Byrne et al. 2012).

The studies emphasize, not only the support that families receive, but the support they can offer. These narratives included the role that giving social support or helping others played in maintaining healthy functioning post-reunification. As families moved past the crisis, many discussed their desire to give back or contribute in some way to helping others (Lietz et al. 2011; Balsells et al. 2015).

The study of support networks was mainly carried out with traditional techniques such as questionnaires, interviews and focus groups. That is, quantitative and qualitative methodologies. Often combining both methodologies. However, Gesell et al. (2016) introduce Social Network Analysis as a method for evaluating the group intervention program with families.

The Social Network Analysis is a tool to measure and analyze the social structures that arise from the relationships between different social actors. In this sense, network analysis pays special attention to the study of social structures, paying more attention to the understanding of interactions between individuals than to what individuals can or cannot do.

As a summary, the provision of support to biologic parents is viewed as a legally mandated responsibility of Child welfare agencies as these services are aimed at the preservation of families or to work towards reunification (Barth et al. 2005). Lack of support from extended family or neighbors is associated with higher risk of return failure (Thoburn 2009). For this reason, support during the initial months of reunification is important for the stability of the reunification. In this sense, support groups reduce the isolation of caregivers and allow newer parents to seek practical advice from more seasoned parents (Sauls and Esau 2015). These support systems provide parents with emotional, material and financial support, helping them to create stability, which is important for family reunification (Potgieter and Hoosain 2018).

5. Conclusions

Studies of family resilience discover that families are capable of generating positive relationships, which help to optimize their possibilities and resources (Walsh 2002). Social support is considered a protective factor for families in a social risk situation (Balsells et al. 2016b).

Regarding informal support, although such support is considered to be indispensable to the reunification process, various studies have found that families at risk (Rodrigo et al. 2007; Fuentes-Peláez et al. 2014) and families under the care of the protection system typically have a poor, insufficient network of informal support to call on when addressing the difficult circumstances and changes to which they must respond.

After participation in the group intervention programs, the studies show that the support received from the new informal support networks is mainly instrumental (like accompanying other members of the group with transport difficulties) or emotional (making them feel understood and not judged) (Berrick et al. 2011).

Furthermore, we can see that there is a change in the way the families view the support offered by the formal network services. Although the studies do not show differences between the support received at the beginning and the end of the group intervention programs, the families have a much more positive view of the help that these services can offer them. In some cases, the families started the programs facing the formal networks due to measures that these services have taken (for example the removal of their children) (Lietz et al. 2011), and by the end of their participation in social intervention programs, they are able to understand the circumstances that lead the professionals to separate the family. In other cases, the families increased the use of the services of the formal network that they did not intend to use at the beginning of the intervention program, such as police, neighborhood associations, child protection services and other institutions (e.g., mental health services, Red Cross) (Byrne et al. 2012).

These changes can also be seen in the effectiveness and the results of the group intervention programs with the families. The families feel listened to and not judged which makes them more open to talking about their stories and working on them (Berrick et al. 2011; Balsells et al. 2016b). Moreover, collaborative earning among group members improves the effectiveness of the socio-educational intervention program (Aschbrenner et al. 2016; Karjalainena et al. 2019).

The authors not only emphasize the importance of families receiving the formal and informal support offered to them, they also come to be seen as sources of informal support in themselves for the rest of the group (Balsells et al. 2015). This change of perspective may be a factor of family resilience.

Scientific evidence demonstrates that group methodology favors this type of support, promoting the development of support networks and mutual help. In this sense, it seems necessary to continue studying the methodologies that favor these networks. This review also shows that these networks can be studied, not only with traditional methodologies, but also with other methodologies such as social network analysis.

6. Limitations

One of the key limitations of the revision was finding research that refers directly to group intervention for family reunification. Furthermore, not all of the articles present the same information, which has made it difficult to compare the studies. Another limitation was not being able to search French and German databases. Finally, it is possible that other sources of social support exist and that have not been considered, for example support via technological tools.

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed equally to the study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received external funding. Funding Reference RTI2018-099305-B-C22 (Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades, Spanish Government).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Amorós, Pere, Maria Àngels Balsells, Nuria Fuentes-Peláez, Crescencia Pastor, Maria Cruz Molina, and Maria Isabel Mateos. 2009. Programme de formation pour familles d’accueil. Impact sur la qualité des enfants et la résilience familiale. In Resilience, Regulation and Quality of Life. Edited by Nader-Grosbois. Louvain: UCL Presses Universitaires de Louvain, pp. 187–93. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, Mary I., Shelly Birnie-Lefcovitch, and Michael T. Ungar. 2005. Pathways Between Social Support, Family Well Being, Quality of Parenting, and Child Resilience: What We Know. Journal of Child and Family Studies 14: 269–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschbrenner, Kelly A., John A. Naslund, and Stephen J. Bartels. 2016. A Mixed methods study of peer-to-peer support in a group-based lifestyle intervention for adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 39: 328–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsells, Maria Àngels. 2006. Québec y Cataluña: Redes y profesionales para la acción socioeducativa con familias, infancia y adolescencia en situación de riesgo social. Revista Española de Educación Comparada 12: 365–87. [Google Scholar]

- Balsells, Maria Àngels, Crescencia Pastor, Ainoa Mateos, Eduard Vaquero, and Aida Urrea. 2015. Exploring the needs of parents for achieving reunification: The views of foster children, birth family and social workers in Spain. Children and Youth Services Review 48: 159–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsells, Maria Àngels, Crescencia Pastor, Maria Cruz Molina, Nuria Fuentes-Peláez, and Noelia Vázquez. 2016a. Understanding Social Support in Reunification: The Views of Foster Children, Birth Families and Social Workers. British Journal of Social Work 47: 812–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsells, Maria Àngels, Nuria Fuentes-Peláez, Maria Isabel Mateo, Joseo Maria Torralba, and Violeta Violant. 2016b. Skills and professional practices for the consolidation of the support group model to foster families. European Journal of Social Work 20: 253–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsells, Maria Àngels, Ainoa Mateos Inchaurrondo, Aida Urrea Monclús, and Eduard Vaquero Tió. 2018. Positive parenting support during family reunification. Early Child Development and Care 188: 1567–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, Richard P., John Landsverk, Patricia Chamberlain, John B. Reid, Jennifer A. Rolls, Michael S. Hurlburt, Elizabeth M. Z. Farmer, Sigrid James, Kristin M. McCabe, and Patricia L. Kohl. 2005. Parent-Training Programs in Child Welfare services: Planning for a More Evidenced-Based Approach to serving Biological Parents. Research on social Work Practice 15: 353–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrick, Jill D., Elizabeth W. Young, Ed Cohen, and Elizabeth Anthony. 2011. “I am the face of success”: Peer mentors in child welfare. Child and Family Social Work 16: 179–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, Sonia, María José Rodrigo, and Juan Carlos Martín. 2012. Influence of form and timing of social support on parental outcomes of a child-maltreatment prevention program. Children and Youth Services 34: 2495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, Ruth M., Rashida M. Crutchfield, Stephanie G. Goddu Harper, Maryam Fatemi, and Angel Y. Rodriguez. 2018. Family reunification in child welfare practice: A pilot study of parent and staff experiences. Children and Youth Services Review 91: 221–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. 2011. Family Reunification: What the Evidence Shows (June). Washington, DC: Child Welfare Information Gateway. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, Elizabeth. 2014. Child Protection and Vulnerable Families: Trends and Issues in the Australian Context. Social Sciences 3: 785–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Peláez, Nuria, Maria Àngels Balsells, Josefina Fernández, Eduard Vaquero, and Pere Amorós. 2014. The social support in kinship foster care: A way to enhance resilience. Child and Family Social Work 21: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesell, Sabina B., Shari L. Barkin, Evan C. Sommer, and Jessica R. Thompson. 2016. Increases in New Social Network Ties are Associated with Increased Cohesion among Intervention Participants. Health Education Behaviour 43: 208–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Ceri J., and Rachel Bryant-Waugh. 2012. Development and pilot of a group skills-and-support intervention for mothers of children with feeding problems. Appetite 58: 450–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjalainena, Piia, Olli Kiviruusu, Eeva T. Aronen, and Päivi Santalahti. 2019. Group-based parenting program to improve parenting and children’s behavioral problems in families using special services: A randomized controlled trial in a real-life setting. Children and Youth Services Review 96: 420–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietz, Cynthia A., and Margaret Strength. 2011. Stories of Successful Reunification: A Narrative Study of Family Resilience in Child Welfare. Families in Society 92: 203–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietz, Cynthia A., Jeffrey R. Lacasse, and Joanne Cacciatore. 2011. Social Support in Family Reunification: A Qualitive Study. Journal of Social Work 14: 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Nan, and Walter M. Ensel. 1989. Life stress and health: Stressors and resources. American Sociological Review 54: 382–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, Lynn, Tammy Conrad, Anna Fairtlough, Joan Fletcher, Liz Green, Liz Moore, and Betty Lepps. 2009. An evaluation of a groupwork intervention for teenage mothers and their families. Child and Family Social Work 14: 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nager, Alan L. 2010. Family Reunification. Concepts and Challenges. Clinical Pediatric Emergency Medicine 3: 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potgieter, Anesta, and Shanaaz Hoosain. 2018. Parents’ experiences of family reunification services. Social Work 54: 438–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, María José, Juan Carlos Martín, María Luisa Máiquez, and Guacimara Rodríguez. 2007. Informal and formal supports and maternal child-rearing practices in at-risk and non at risk psychosocial contexts. Children and Youth Service Review 29: 329–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauls, Heidi, and Esau Faheemah. 2015. An Evaluation of Family Reunification Services in the Western Cape: Exploring Children, Families and Social Workers’ Experiences of Family Reunification Services within the First Twelve Months of Being Reunified; Cape Town: Directorate Research, Population and Knowledge Management, Western Cape Government.

- Thoburn, June. 2009. Reunification of Children in Out-Of-Home Care to Birth Parents or Relatives: A Synthesis of the Evidence on Processes, Practice and Outcomes. Norwich: University of East Anglia. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, Froma. 2002. A family resilience framework: Innovative practice applications. Family Relations 51: 130–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Ying-Shun, Hsin Chu, Chiung-Hua Chen, Yu-Jung Hsueh, Yu-Shiun Chang, Lu-I. Chang, and Kuei-Ru Chou. 2012. Support groups for caregivers of intellectually disabled family members: Effects on physical–psychological health and social support. Journal of Clinical Nursing 21: 1666–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).