State-Society Relations in Ethiopia: A Political-Economy Perspective of the Post-1991 Order

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. State-Society Relations: A Conceptual Overview

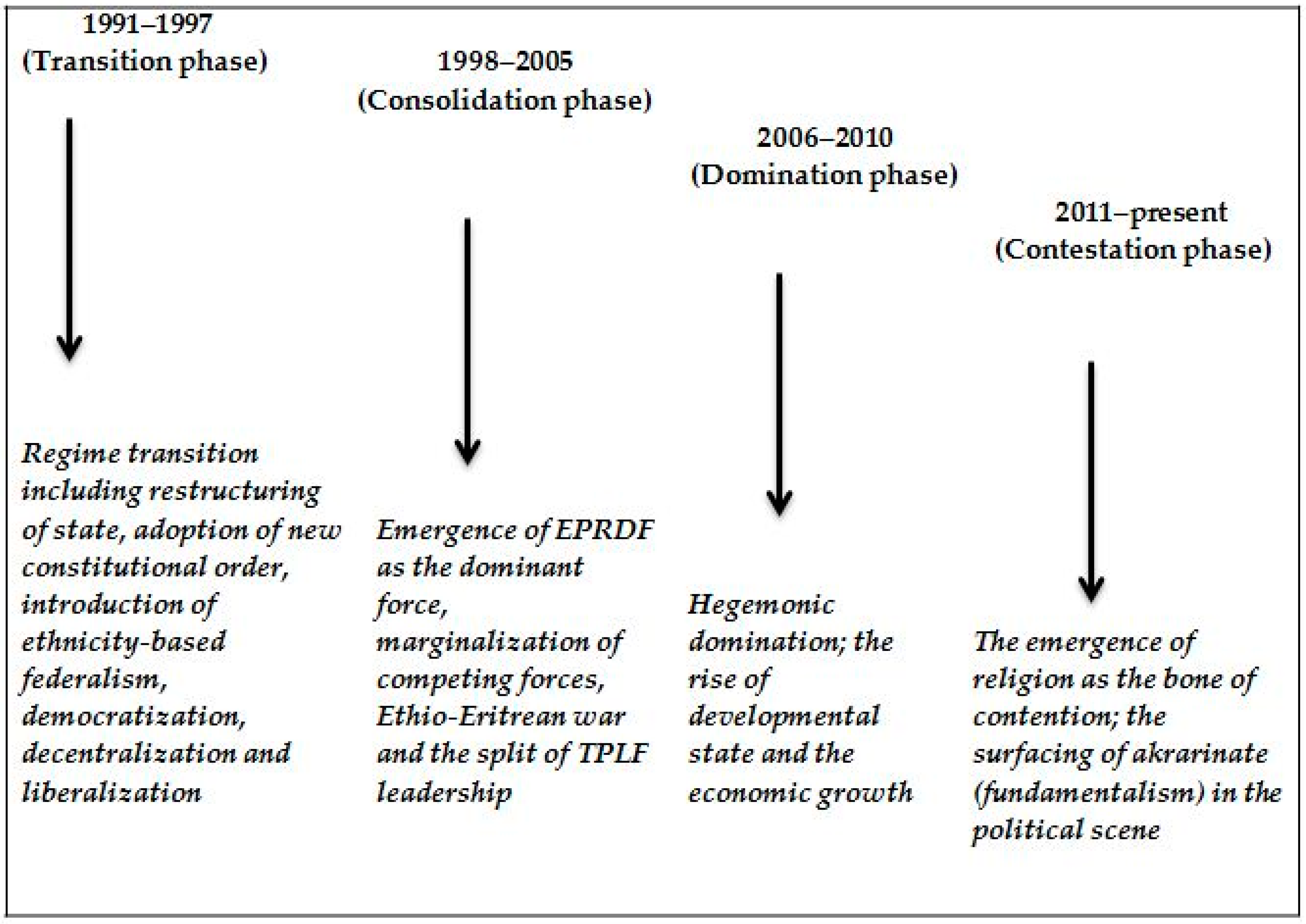

3. The Post-1991 Dynamics: Political Transformation and Continuity

4. State-Society Relations in Ethiopia: Property, Representation and Identity Rights

The centrifugal force of Ethiopian politics and Ethiopian society since 1960 is an irreversible dispute between the urban and rural elite. Both are fiercely fighting to justify their cause in noble ways using ethno-nationalism and civic nationalism. It seems that the rural elite are gaining dominance and restructuring the very nature of Ethiopian society along ethnic lines. However, the remarkable thing is most people could not recognize the hassle behind ethnic politics.[50]

5. State-Society Relations in Rural Ethiopia

5.1. Perception and Symbols of the State: Kawo, Motuma, and Mengist

We elect the government and we make the state. However, the state decides our fate and organizes our life. We give our power to the state for the common good of our life. Otherwise our lives might be in jeopardy.[55]

State is the essence of our life. Without state we cannot work, we cannot trade and send our kids to school. The moment we lose the state, we start killing and robbing each other. We can have only peaceful and prosperous life so long as the state exists.[56]

5.2. The Practice of State: Social Control, Decision-Making and Control over Means of Violence

The popular organizations are quite helpful to support each other, learn from each other, work together, mobilize the community in conservation; water shed management and maintain security of the locality. We are being organized in popular wing (heizebawikenfe), governmental wing (Mengistawikenfe) and party wing (derjetawikenfi). All these three broad organizational chains have created interconnectedness and interdependence among the local communities.[61]

We do not have any rights in this land. Kawos decides everything. My family’s fate and existence depend on the will of Kawo because we got land, selected seed, credit and assistance from our Kawo. Our Kawo is even more powerful than God in our land.[62]

Few years back there was a serious security problem. But nowadays the security situation is significantly improved. The popular organizations and the introduction of community policing are the reasons for improved security in our locality. We do not have any security problem. The security of our neighborhood is effectively maintained by local security forces and the people themselves.[63]

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- John Markakis. Ethiopia: The Last Two Frontiers. Rochester: James Currey, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Aaron Tesfaye. Political Power and Ethnic Federalism: Struggle for Democracy in Ethiopia. Maryland: University press of America, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Taddesse Tamrat. Church and State in Ethiopia, 1270–1527. New York: Clarendon Press, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Teshale Tibebu. The Making of Modern Ethiopia, 1896–1974. Lawrenceville: The Red Sea Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bahru Zewede. The History of Modern Ethiopia, 1855–1974. London: James Carrey, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gebru Tareke. Ethiopia: Power and Protest: Peasant Revolts in the Twentieth Century. Lawrenceville: The Red Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Aregawi Berhe. A Political History of the Tigray People's Liberation Front (1975–1991): Revolt, Ideology and Mobilisation in Ethiopia. Los Angles: Tsehai Publishers, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mesfin M. WoldeMariam. Rural Vulnerability to Famine in Ethiopia: 1958–1977. New Delih: Vikas Publishing House, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Joel S. Migdal. State in Society: Studying How States and Societies Transform and Constitute One Another. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy Mitchell. “The Limits of the State: Beyond Statist Approaches and Their Critiques.” American Political Science Review 85 (1991): 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georg Sørensen. The Transformation of the State: Beyond the Myth of Retreat. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferey M. Sellers, and Sun-Young Kwak. “State and Society in Local Governance: Lessons from a Multilevel Comparison.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 35 (2010): 620–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joel S. Migdal. Strong Societies and Weak States: State-Society Relations and State Capabilities in the Third World. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis H. Wrong. Power. New Brunswick. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis H. Wrong. Power: Its Forms, Bases and Uses. Piscataway: Transaction Books, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Janice E. Thomson. “State sovereignty in international relations: Bridging the gap between theory and empirical research.” International Studies Quarterly 39 (1995): 213–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derek Layder. “Power, Structure and Agency.” Journal for the Theory of Social Behavior 15 (1985): 131–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael Mann. “The autonomous power of the state: Its origins, mechanisms and results.” European Journal of Sociology 25 (1984): 185–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjetil Tronvoll, and Tobias Hagmann. Contested Power in Ethiopia: Traditional Authorities and Multiparty Election. Leiden: Bril, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sarah Vaughan. “Revolutionary democratic state-building: Party, state and people in the EPRDF’s Ethiopia.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 5 (2011): 619–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jon Abbink. “Ethnic-based federalism and ethnicity in Ethiopia: Reassessing the experiment after 20 years.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 5 (2011): 596–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarah Vaughan, and Kjetil Tronvoll. The Culture of Power in Contemporary Ethiopian Political Life. Stockholm: Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nahum Fasil. Constitution for a Nation of Nations: The Ethiopian Prospect. Lawrenceville and Asmara: The Red Sea Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lovise Aalen. “Ethnic Federalism in a Dominate Party State: the Ethiopian Experience 1991–2000.” In Development Studies and Human Rights Report. Christainsend: Bergen Michelson Institute, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Assefa Fiseha. Federalism and Accommodation of Diversity in Ethiopia: A Comparative Study. Utrecht: Wolf Legal Publisher, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- David Turton. Ethnic Federalism: The Ethiopian Experience in Comparative Perspective. Oxford: James Currey, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Christophe Van der Beken. “Ethiopia: Constitutional Protection of Ethnic Minorities at the Regional Level.” Afrika Focus 20 (2007): 105–51. [Google Scholar]

- Alemseged Abbay. “Diversity and State Building in Ethiopia.” African Affairs 103 (2004): 593–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodore M. Vestal. Ethiopia: A Post-Cold War African State. London: Praeger, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Siegfried Pausewang, Kjetil Tronvoll, and Lovise Aalen. Ethiopia Since the Derg: A Decade of Democratic Pretensions and Performance. London: Zed books, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Merera Gudina. Ethiopia: Competing Ethnic Nationalisms and the Quest for Democracy, 1960–2000. Addis Ababa: Chamber Printing House, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Medhane Tadesse, and John Young. “TPLF: Reform or decline? ” Review of African Political Economy 30 (2003): 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher Clapham. “Post-War Ethiopia: The Trajectories of Crisis.” Review of African Political Economy 30 (2009): 181–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- René Lefort. “Powers-Mengist—and Peasants in Rural Ethiopia: The May 2005 Elections.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 45 (2007): 253–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovise Aalen. The Politics of Ethnicity in Ethiopia: Actors, Power and Mobilisation under Ethnic Federalism. Leiden: Brill, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Randi Rønning Balsvik. Haile Selassie’s Students: The Intellectual and Social Background to Revolution: 1952–1974. Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bahru Zewde, ed. Documenting the Ethiopian Student Movement: An Exercise in Oral History. Addis Ababa: Fourm for Social Studies, 2010.

- Gebru Tareke. The Ethiopian Revolution: War in the Horn of Africa. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- The Provisional Military Council of Ethiopia. “Negarit Gazeta—A Proclamation to Provide for Government Ownership of Urban Lands and Extra Urban Houses. No. 41.” 26 July 1975. Available online: http://faolex.fao.org/cgibin/faolex.exe?database=faolex&search_type=link&table=result&lang=eng&format_name=@ERALL&rec_id=001827 (accessed on 15 August 2016).

- The Provisional Military Council of Ethiopia. “Negarit Gazeta—A Proclamation to Provide for the Public Ownership of Rural Lands. No. 31.” 26 July 1975. Available online: http://faolex.fao.org/cgibin/faolex.exe?rec_id=001828&database=faolex&search_type=link&table=result&lang=eng&format_name=@ERALL (accessed on 15 August 2016).

- Edmond J. Keller. “Constitutionalism, Citizenship and Political Transition in Ethiopia: Historic and Contemporary Process.” In Self-Determination and National Unity: A Challenge for Africa. Edited by Francis M. Deng. Trenton: World Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Edmond J. Keller. “Federalsim, citizenship and national identity in Ethiopia.” The International Journal of African Studies 6 (2007): 38–70. [Google Scholar]

- Allen Hoben. Land Tenure among the Amhara of Ethiopia:The Dynamics of Cognatic Descent. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- John M. Cohen, and Dov Weintraub. Land and Peasants in Imperial Ethiopia. The Social Background to a Revolution. Assen: Van Gorcum & Comp., 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Siegfri Pausewang. Peasants, Land and Society: A Social History of Land Reform in Ethiopia. Munchen: Weltfourm Verlag, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Sandra F. Joireman. Property Rights and Political Development in Ethiopia and Eritrea 1941–74. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Teketel Abebe Kebede. “Tenants of the State: The Limitations of Revolutionary Agrarian Transformation in Ethiopia, 1974–1991.” Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Sociology, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 4 June 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dessalegn Rahmato. The Peasant and the State: Studies in Agrarian Change in Ethiopia 1950–2000’s. Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Donald Crummey. Land and Society in the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia: From the Thirteenth to the Twentieth Century. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- A politician and academic, and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. “Interview.” 2012. [Google Scholar]

- George Shepperson. “Ethiopianism and African Nationalism.” Phylon 14 (1953): 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa Jalata. “Being in and out of Africa: The Impact of Duality of Ethiopianism.” Journal of Black Studies 40 (2009): 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovise Aalen, and Kjetil Tronvoll. “The End of Democracy? Curtailing Political and Civil Rights in Ethiopia.” Review of African Political Economy 36 (2009): 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesfin WoldeMariam. Suffering under God’s Environment: A Vertical Study of the Predicament of Peasants in North-Eastern Ethiopia. Berne: Geographica Bernenisa, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- A peasant, and Gerema Kebele, Jimma area, Ethiopia. “Interview.” 2012. [Google Scholar]

- A peasant, and Alyu Amba Kebele, Debere Berhan area, Ethiopia. “Interview.” 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan. NewYork: Continuum Publishing, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Svein Einar Ege. Class, State and Power in Africa: A Case Study of Kingdom of Shawa (Ethiopia) about 1840. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Eva Poluha, and Mona Rosendahl. Learning Political Behavior: Peasant-State Relations in Ethiopia in Poluha, E & Rosendahl, Mona Contesting “Good” Governance. London: Routledge, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- René Lefort. “Powers-Mengist—And peasants in rural Ethiopia: The post-2005 interlude.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 48 (2010): 435–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A peasant, and Dawa Kebele, Jimma Area, Ethiopia. “Interview.” 2012. [Google Scholar]

- A peasant, and Amara ena Bodo, Gamo Area, Ethiopia. Focus group discussion, 2012.

- A peasant, and Goshe Bado, Debere Berhan area, Ethiopia. “Interview.” 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 1The post-1991 political order is unique in the sense of restructuring the Ethiopian state along ethnic federalism and promoting cultural pluralism of competing ethnic groups. Both factions have negated the idea of pan-Ethiopianism (a unified and single Ethiopia) and uphold ethnic nationalism.

- 2In the wake of the Ethio-Eritrea war (1998–2000), the TPLF senior officials split into two groups, dividing as Yemeslse buden (Prime Minister Meles Zenawi´s team) and Yeanjawu buden (the contester team). The cause of the split was differences over how to deal with the war and dissatisfaction with Zenawi´s leadership in the war. The squabble and power struggle continued for a month. Later, Prime Minister Zenawi´s team emerged as a winner [32].

- 3After 2005, EPRDF introduced the new ideology of the developmental democratic state. Meles Zenawi (the late prime minister) was considered as the mentor of the new ideology. The new ideology undermines Western neo-liberalism and espouses the Chinese model of development, which puts state at the centre of any development activities.

- 4The movement of the Muslim community (demestachen yesema—our voice to be heard) which started in Addis Ababa with small-scale opposition following the arrest of the Muslim leaders, snowballing into a nationwide movement, is an example of this case. In the same way other religious groups too gained popular support.

- 7The land tenure system in Ethiopia is one of the most controversial issues. Before 1974, the tenure system included Rist, Rist-gult, and Gult. The rist system was a kind of corporate ownership system based on descent that granted usufruct rights—the right to appropriate the return from the land. In the rist system, all male and female descendants of an individual founder or occupier were entitled to a share of land [43]. Gult right refers to a fief right that required the occupant of specific rist tenure (or those who held other types of traditional land rights) to pay tribute and taxes in cash, kind, or labour to landlords. Gult rights were not inheritable or not necessarily hereditary [44,45]. Rist-gult right is an exclusive right vested on royal families and provincial lords who have the right to independently levy taxes in cash, kind, and labour [46].

- 8Pan-Ethiopianism represents a unique socio-political and cultural character as being an Ethiopian. It is believed to be constructed by Shewa nobles following the incorporation of the southwestern and southeastern part of present Ethiopia. It is contentious for having two dimensions. Externally, it is widely revered by many populations of black-African origin primarily from the Caribbean and North America, as a symbol of redemption and independence [51] Internally, it is considered devious and branded among contending ethnic groups, mainly by Oromo and other minority ethnic groups, as the symbol of domination. [52].

- 9PDO refers to Peoples’ Democratic Organizations. During the Transition Period (1991–95) different ethnic groups created this kind of political organization in an attempt to get representation in the new government.

- 10In Ethiopian traditional context, state and government are not separate concepts. The term Mengist denotes a unified concept of sovereignty and the machinery of power [54].

- 11The Hobbesian view implies the social disorder and the brute situation of a state of nature; “the war of all against all“could be avoided only by a strong, undivided state [57].

| Background | Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Occupation | Farmer | 479 | 92.5 |

| Other | 39 | 7.5 | |

| Education | Illiterate | 222 | 42.9 |

| Primary | 237 | 45.8 | |

| Secondary and above | 59 | 11.3 | |

| Gender | Male | 483 | 93.2 |

| Female | 35 | 6.8 | |

| Household income (in ETB) | <100 ETB | 118 | 22.8 |

| 101–300 | 154 | 29.7 | |

| 301–500 | 124 | 23.9 | |

| >500 ETB | 122 | 22.6 | |

| Total | N = 518 | 100% |

| Questions | Mean | St.Dv. | Respondents’ Ratings | Total (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD | DA | UD | AG | SA | ||||

| 1.Local authorities are accountable to the local people | 3.83 | 0.86 | 3 (0.6) | 16 (3.1) | 132 (25.5) | 183 (35.4) | 184 (35.5) a | 518 (100) |

| 2.Local people have full right to make decisions on local matters | 3.38 | 0.96 | 2 (0.4) | 30(5.8) | 161 (31.1) | 240 (46.3) | 85 (16.4) | 518(100) |

| 3.Local people have a right to set agenda on local matters | 3.22 | 0.98 | 3 (0.6) | 22 (4.2) | 158 (30.5) | 213 (41.1) | 122 (23.6) | 518 (100) |

| 4.The local authorities properly keep peace and security so that the crime rate is low | 3.73 | 0.82 | 9 (1.7) | 80 (15.4) | 204 (39.4) | 154 (29.7) | 71 (13.7) | 518 (100) |

| Items | Mean | SD | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Local authorities are accountable to the local people | 3.83 | 0.86 | –4.56 * |

| 2. Local people have full right to make decisions on local matters | 3.38 | 0.96 | –14.62 |

| 3. Local people have a right to set agenda on local matters | 3.22 | 0.98 | –18.12 |

| 4.The local authorities properly keep peace and security so that the crime rate is low | 3.73 | 0.82 | –7.637 |

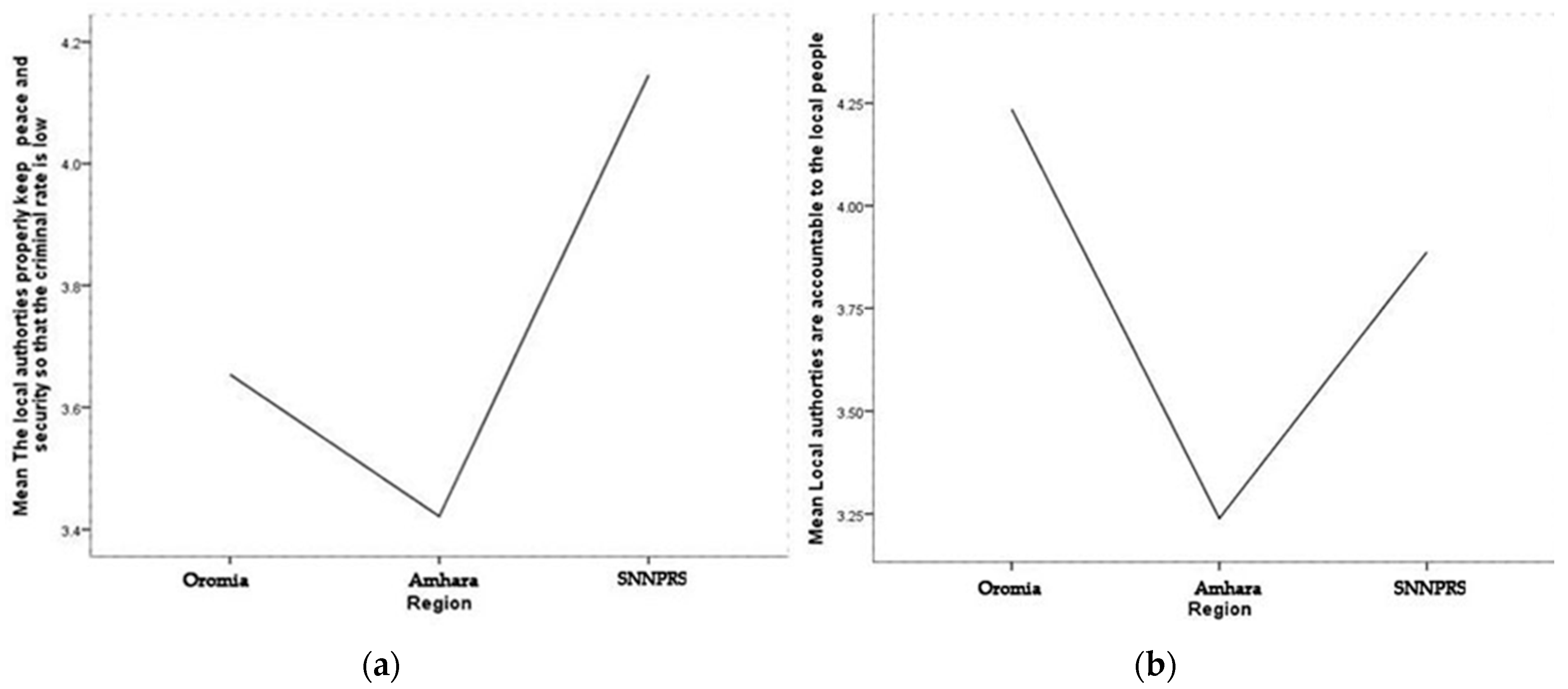

| Indicators | Region | Mean | SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Local authorities are accountable to the local people | Oromia | 4.24 | 0.59 | 208 |

| Amhara | 3.42 | 0.70 | 159 | |

| SNNPRS | 4.15 | 0.88 | 151 | |

| Total | 3.73 | 0.82 | 518 | |

| 2. Local people have the right to set agenda on local matters | Oromia | 3.25 | 0.92 | 208 |

| Amhara | 2.80 | 0.78 | 159 | |

| SNNPRS | 3.62 | 1.08 | 151 | |

| Total | 3.22 | 0.98 | 518 | |

| 3.Local people have full right to make decisions on local matters | Oromia | 3.44 | 0.93 | 208 |

| Amhara | 3.08 | 0.81 | 159 | |

| SNNPRS | 3.62 | 1.07 | 151 | |

| Total | 3.38 | 0.96 | 518 | |

| 4. The local authorities properly keep peace and security so that the crime rate is low | Oromia | 3.65 | 0.73 | 208 |

| Amhara | 3.42 | 0.70 | 159 | |

| SNNPRS | 4.15 | 0.88 | 151 | |

| Total | 3.73 | 0.82 | 518 |

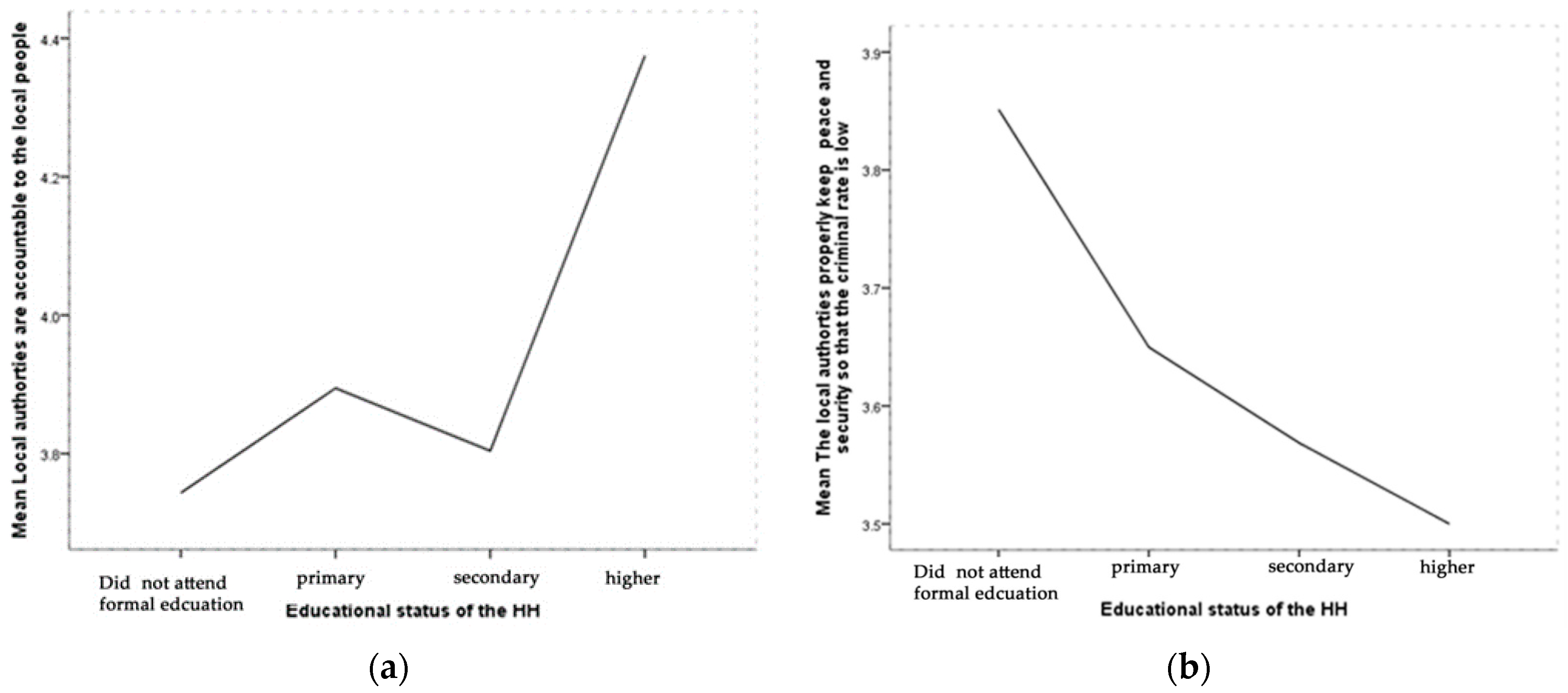

| F | Sig. | Partial eta Squared | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local authorities are accountable to the local people | |||

| Region | 23.92 | 0.000 | 0.086 |

| Educational Status | 2.69 | 0.046 | 0.016 |

| Educational Status x Region | 5.19 | 0.000 | 0.058 |

| a. R squared = 0.300 (adjusted r squared = 0.285) | |||

| Local people have full right to make decisions on local matters | |||

| Region | 1.102 | 0.333 | 0.004 |

| Educational Status | 3.401 | 0.018 | 0.020 |

| Educational Status x Region | 2.166 | 0.045 | 0.025 |

| a. R squared = 0.098 (adjusted r squared = 0.078) | |||

| Local people have the right to set agenda on local matters | |||

| Region | 7.59 | 0.001 | 0.029 |

| Educational status | 3.56 | 0.014 | 0.021 |

| Region x Educational Status | 1.49 | 0.188 | 0.017 |

| a. R squared = 0.140 (adjusted r squared = 0.121) | |||

| Local authorities properly keep peace and security so that the crime rate is low | |||

| Region | 0.657 | 0.519 | 0.003 |

| Educational status | 4.06 | 0.007 | 0.024 |

| Region x Educational Status | 1.829 | 0.092 | 0.021 |

| a. R squared = 0.164(adjusted r squared = 0.146) | |||

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bekele, Y.W.; Kjosavik, D.J.; Shanmugaratnam, N. State-Society Relations in Ethiopia: A Political-Economy Perspective of the Post-1991 Order. Soc. Sci. 2016, 5, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5030048

Bekele YW, Kjosavik DJ, Shanmugaratnam N. State-Society Relations in Ethiopia: A Political-Economy Perspective of the Post-1991 Order. Social Sciences. 2016; 5(3):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5030048

Chicago/Turabian StyleBekele, Yeshtila Wondemeneh, Darley Jose Kjosavik, and Nadarajah Shanmugaratnam. 2016. "State-Society Relations in Ethiopia: A Political-Economy Perspective of the Post-1991 Order" Social Sciences 5, no. 3: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5030048

APA StyleBekele, Y. W., Kjosavik, D. J., & Shanmugaratnam, N. (2016). State-Society Relations in Ethiopia: A Political-Economy Perspective of the Post-1991 Order. Social Sciences, 5(3), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5030048