Income Sharing within Households: Evidence from Data on Financial Satisfaction

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Norms and Expectations Regarding Income Sharing

2.2. Empirical Findings about Income Sharing from Satisfaction Data

2.3. The Validity of Financial Satisfaction for Analyses of Intra-Household Sharing

3. Theoretical Approach

4. Data and Empirical Specification

4.1. Differences in Financial Satisfaction and the Distribution Factor

How satisfied are you today with the following areas of your life? Please answer by using the following scale: 0 means ‘totally unhappy’, 10 means ‘totally happy’.

How satisfied are you with your household income?

4.2. Further Covariates

5. Estimation and Results

5.1. Joint Estimates

5.2. Subsample Estimates

5.3. Interpretation

6. Concluding Remarks

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stephen P. Jenkins. “Poverty Measurement and the Within-Household Distribution.” Journal of Social Policy 20 (1991): 457–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelley A. Phipps, and Peter S. Burton. “Sharing within families: Implications for the measurement of poverty among individuals in Canada.” Canadian Journal of Economics 28 (1995): 177–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susan Himmelweit, Cristina Santos, Almudena Sevilla, and Catherine Sofer. “Sharing of Resources Within the Family and the Economics of Household Decision Making.” Journal of Marriage and Family 75 (2013): 625–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notburga Ott. Intrafamily Bargaining and Household Decisions. Berlin: Springer, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Shelly Lundberg, and Robert A. Pollak. “Bargaining and Distribution in Marriage.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 10 (1996): 139–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert O. Blood, and Donald M. Wolfe. Husbands & Wives. The Dynamics of Married Living. New York: Free Press, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Patricia F. Apps, and Ray Rees. “Taxation and the household.” Journal of Public Economics 35 (1988): 355–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre-André Chiappori. “Rational household labor supply.” Econometrica 56 (1988): 63–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre-André Chiappori. “Collective labor supply and welfare.” Journal of Political Economy 100 (1992): 437–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan Thomas. “The Distribution of Income and Expenditure within the Household.” Annales d’Economie et de Statistique, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin Browning, Francois Bourguignon, Pierre-André Chiappori, and Valerie Lechene. “Income and Outcomes: A Structural Model of Intrahoushold Allocation.” Journal of Political Economy 102 (1994): 1067–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelly J. Lundberg, Robert A. Pollak, and Terence J. Wales. “Do Husbands and Wives Pool Their Resources? Evidence from the United Kingdom Child Benefit.” Journal of Human Resources 32 (1997): 463–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelley A. Phipps, and Peter S. Burton. “What’s Mine is Yours? The Influence of Male and Female Incomes on Patterns of Household Expenditure.” Economica 65 (1998): 599–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francois Bourguignon, Martin Browning, Pierre-André Chiappori, and Valérie Lechene. “Intra Household Allocation of Consumption: A Model and Some Evidence from French Data.” Annales d’Économie et de Statistique, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerome De Henau, and Susan Himmelweit. “Unpacking Within-Household Gender Differences.” Journal of Marriage and Family 75 (2013): 611–24. [Google Scholar]

- Namkee Ahn, Victoria Ateca-Amestoy, and Arantza Ugidos. “Financial Satisfaction from an Intra-Household Perspective.” Journal of Happiness Studies 15 (2013): 1109–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francine M. Deutsch, Josipa Roksa, and Cynthia Meeske. “How gender counts when couples count their money.” Sex Roles 48 (2003): 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julie L. Hotchkiss. “Do Husbands and Wives Pool Their Resources? Further Evidence.” Journal of Human Resources 40 (2005): 519–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan Pahl. Money & Marriage. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Frances Woolley. “Control over Money in Marriage.” In Marriage and the Economy: Theory and Evidence from Advanced Industrial Societies. Edited by Shoshana Grossbard-Shechtman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Paul Frijters, and B. Van Praag. “The measurement of welfare and well-being: The Leyden approach.” In Well-Being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology. Edited by Daniel Kahneman, Edward Diener and Norbert Schwarz. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1999, pp. 413–33. [Google Scholar]

- Fran Bennett, Jerome De Henau, Susan Himmelweit, and Sirin Sung. “Financial Togetherness and Autonomy Within Couples.” In Gendered Lives. Gender Inequalities in Production and Reproduction. Edited by Shirley Dex, Jacqueline L. Scott and Anke Plagnol. Cheltenhan: Edwards Elgar, 2012, pp. 97–122. [Google Scholar]

- Carolyn Vogler. “Cohabiting Couples: Rethinking Money in the Household at the Beginning of the Twenty First Century.” The Sociological Review 53 (2005): 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudia Olivetti, and Barbara Petrongolo. “The Evolution of Gender Gaps in Industrialized Countries.” 2016. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w21887.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2016).

- Aline Bütikofer, and Michael Gerfin. “The Economies of Scale of Living Together and How They Are Shared: Estimates Based on a Collective Household Model.” Review of Economics of the Household, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rob Alessie, Thomas F. Crossley, and Vincent Hildebrand. “Estimating a Collective Household Model with Survey Data on Financial Satisfaction.” 2006. Available online: http://www.ifs.org.uk/wps/wp0619.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2016).

- Jens Bonke, and Martin Browning. “The distribution of well-being and income within the household.” Review of Economics of the Household 7 (2009): 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekaterina Kalugina, Natalia Radtchenko, and Catherine Sofer. “How Do Spouses Share their full Income? Identification of the Sharing Rule Using Self-Reported Income.” Review of Income and Wealth 55 (2009): 360–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bernard M.S. Van Praag, and Ada Ferrer-i-Carbonell. Happiness Quantified: A Satsifaction Calculus Approach, rev. ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Alois Stutzer. “The Role of Income Aspirations in Individual Happiness.” Journal of Economic Behaviour and Organization 54 (2004): 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew E. Clark, Paul Frijters, and Michael A. Shields. “Relative Income, Happiness, and Utility: An Explanation for the Easterlin Paradox and Other Puzzles.” Journal of Economic Literature 46 (2008): 95–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ada Ferrer-i-Carbonell. “Happiness Economics.” SERIEs 4 (2013): 35–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Philip Brickman, and Donald T. Campbell. “Hedonic relativism and planning the good society.” In Adaptation-Level Theory. Edited by Mortimer H. Appley. New York: Academic Press, 1999, pp. 287–305. [Google Scholar]

- Keith Magnus, Ed Diener, Frank Fujita, and William Pavot. “Extraversion and neuroticism as predictors of objective life events: A longitudinal analysis.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 65 (1993): 1046–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maike Luhmann, Ulrich Schimmack, and Michael Eid. “Stability and Variability in the Relationship between Subjective Well-Being and Income.” Journal of Research in Personality 45 (2011): 186–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tania Burchardt. “Are One Man’s Rags Another Man’s Riches? Identifying Adaptive Expectations Using Panel Data.” Social Indicators Research 74 (2014): 57–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew E. Clark, Ed Diener, Yannis Georgellis, and Richard E. Lucas. “Lags and Leads in Lifesatisfaction: A Test of the Baseline Hypothesis.” Economic Journal 118 (2008): 222–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich Beck. Risikogesellschaft. Auf dem Weg in Eine Andere Moderne. FrankfurtM: Suhrkamp, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ronald Inglehart. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rüdiger Peuckert. Familienformen im sozialen Wandel. Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Socio-Economic Panel 2012. “Data for Years 1984-2011.” German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin), 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joachim R. Frick, Jürgen Schupp, and Gert G. Wagner. “The German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP)—Scope, Evolution and Enhancements.” Schmollers Jahrbuch (Journal of Applied Social Science Studies) 127 (2007): 139–69. [Google Scholar]

- John P. Haisken-DeNew, and Joachim R. Frick. “DTC Desktop Companion to the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP).” 2005. Available online: http://www.diw.de/documents/dokumentenarchiv/17/diw_01.c.38951.de/dtc.409713.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2016).

- Cahit Guven, Claudia Senik, and Holger Stichnoth. “You Can’t Be Happier Than Your Wife. Happiness Gaps And Divorce.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 82 (2012): 110–30. [Google Scholar]

- Joachim R. Frick, Jan Goebel, Edna Schechtman, Gert G. Wagner, and Shlomo Yitzhaki. “Using Analysis of Gini (AnoGi) for Detecting Whether Two Sub-Samples Represent the Same Universe: The German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP) Experience.” Sociological Methods & Research 34 (2006): 427–68. [Google Scholar]

- Johannes Schwarze. “Using Panel Data on Income Satisfaction to Estimate Equivalence Scale Elasticity.” Review of Income and Wealth 49 (2003): 359–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ada Ferrer-i-Carbonell, and Paul Frijters. “How Important is Methodology for the Estimates of the Determinants of Happiness? ” The Economic Journal 114 (2004): 641–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fran Bennett. “Researching Within-Household Distribution: Overview, Developments, Debates, and Methodological Challenges.” Journal of Marriage and Family 75 (2013): 582–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2.This information exists in only four of the 12 years of data that I use, but of those, it was 73% of the couples who congruently answered at least once that they pool their entire incomes; and those who pool do this for most (86%) of the time.

- 3.This information exists in only four of the 12 years of data that I use; 79% of the couples who answered congruently at least once that they make financial decisions together gave this answer in 71% of the years.

- 4.Less critical caveats include the argument that financial satisfaction depends not only on the income (share), but also on needs, expectations and deviations thereof (for an overview, see [30,31,32]), and may also be driven by individual’s personality [33,34,35]. These concerns are accounted for by controlling for a wide range of covariates and by using fixed effects estimation.

- 5.For single households, this is the household income; for individuals in multi-person households, it is some share of the household income. Note that the sum of shares may exceed the household income because of the economies of scales of living together [25].

- 6.According to the idea of adaptation [30], I assume that expectations about welfare levels are tailored towards the household’s scope, i.e., expected welfare-effective income is a function of total household income.

- 7.This assumption is necessary because otherwise, only deviations from expected shares of income can be detected and not deviations from equal sharing. In the cultural context of present-day Germany, which is characterized by individualization [38] and post-materialism [39], this assumption is sound. However, research into the allocation of domestic work (for an overview: [40]) and of income sharing (see [5,10,11,13,19]) shows that reality often falls short of such expectations.

- 8.For this step, the assumptions that partners expect equal sharing in terms of equal welfare levels (cf. Equation (1)) and that expected welfare-effective income is a function of the household income are necessary.

- 9.This distribution factor can be derived from bargaining models, as well as from the resource theory of power.

- 11.This reduces the sample by about .

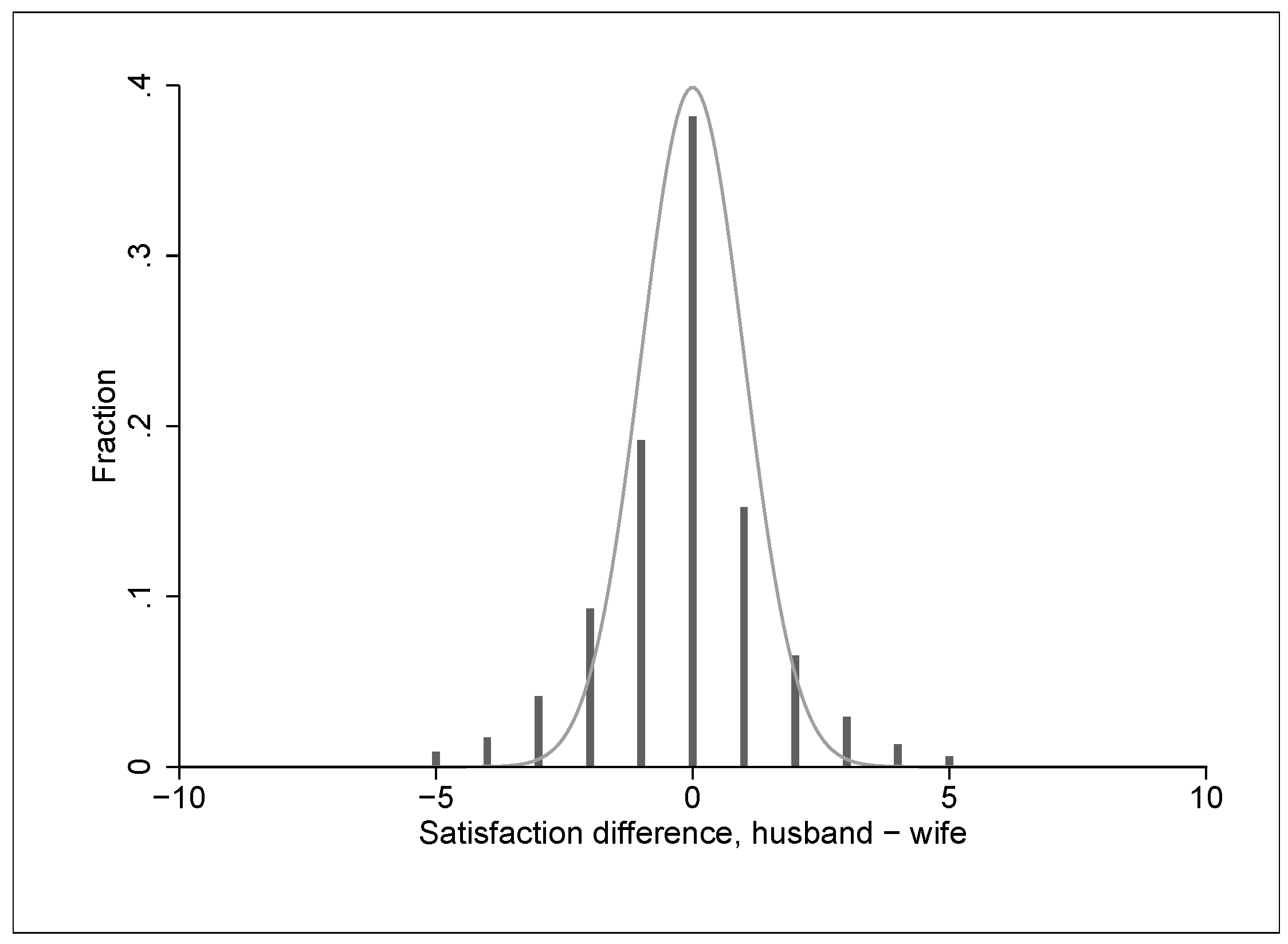

- 12.While this variable could theoretically range from −10–10, its empirical range is −5–5.

- 13.These include all monthly incomes at the time of the interview that do not depend on the household’s structure or income, e.g., no means-tested transfers, but, for example, different sorts of unemployment benefits, child benefits and widows’ pensions.

- 14.Results are not shown here, though available on request.

- 15.Information about the household income is one partner’s response to the question: “If you take a look at the total income from all members of the household: how high is the monthly household income today? Please state the net monthly income, which means after deductions for taxes and social security. Please include regular income such as pensions, housing allowance, child allowance, grants for higher education support payments, etc.”

- 16.Couples where both partners are part-time or not employed (but not unemployed) and female breadwinner couples are too few for corresponding estimations.

- 17.The z-value for the difference of the effects is

| Variable | Mean | SD | SD Within |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction difference | −0.137 | 1.573 | 1.207 |

| Men’s financial satisfaction | 6.347 | 2.131 | 1.154 |

| Women’s financial satisfaction | 6.484 | 2.159 | 1.176 |

| Men’s income | 3344.59 | 2582.31 | 1229.92 |

| Women’s income | 1406.11 | 1524.81 | 653.67 |

| Income ratio | 0.705 | 0.244 | 0.112 |

| Men’s working hours | 35.98 | 19.45 | 9.584 |

| Women’s working hours | 20.24 | 18.21 | 8.579 |

| Working hours ratio | 0.586 | 0.341 | 0.178 |

| Equivalized household income | 2007.77 | 1160.37 | 586.36 |

| Married | 0.893 | ||

| Household without children | 0.377 | ||

| Children under age of 6 in household | 0.211 | ||

| Male breadwinner household | 0.512 | ||

| Partners equally employed | 0.303 | ||

| Female breadwinner household | 0.075 | ||

| Households with at least one partner unemployed | 0.085 |

| Variable | Dependent Variable: Satisfaction Difference | Dependent Variable: Financial Satisfaction | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Couples | Men | Women | ||||||||||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | ||||||||||||

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | |||||||

| Income ratio | 0.429 | *** | (0.119) | 0.443 | *** | (0.120) | 0.511 | *** | (0.116) | −0.007 | (0.123) | −0.451 | *** | (0.126) | ||

| Working hours ratio | 0.104 | (0.093) | 0.188 | ** | (0.094) | 0.084 | (0.094) | |||||||||

| Male breadwinner hh | -0.081 | (0.052) | ||||||||||||||

| Female breadwinner hh | 0.012 | (0.063) | ||||||||||||||

| Other hh empl. situations | 0.025 | (0.064) | ||||||||||||||

| Man’s income | −0.026 | ** | (0.012) | −0.027 | ** | (0.012) | −0.026 | ** | (0.012) | 0.070 | *** | (0.014) | 0.097 | *** | (0.013) | |

| Woman’s income | 0.011 | (0.007) | 0.012 | (0.007) | 0.010 | (0.008) | 0.012 | * | (0.007) | 0.000 | (0.008) | |||||

| Man’s weekly working hours | 0.001 | (0.001) | −0.000 | (0.002) | 0.003 | * | (0.002) | 0.003 | * | (0.002) | ||||||

| Woman’s weekly working hours | −0.002 | (0.001) | −0.001 | (0.001) | 0.003 | ** | (0.002) | 0.004 | *** | (0.001) | ||||||

| Man part-time empl. | −0.005 | (0.051) | ||||||||||||||

| Woman part-time empl. | 0.060 | (0.055) | ||||||||||||||

| Man not employed | −0.048 | (0.077) | ||||||||||||||

| Woman not employed | 0.085 | (0.068) | ||||||||||||||

| Youngest child up to 3 years | 0.166 | * | (0.093) | 0.162 | * | (0.093) | 0.191 | ** | (0.093) | 0.050 | (0.091) | −0.112 | (0.091) | |||

| Youngest child 4–6 years | 0.117 | (0.090) | 0.116 | (0.090) | 0.132 | (0.091) | 0.060 | (0.090) | −0.056 | (0.089) | ||||||

| Youngest child 7–10 years | 0.154 | * | (0.088) | 0.153 | * | (0.088) | 0.167 | * | (0.088) | 0.100 | (0.087) | −0.053 | (0.087) | |||

| Youngest child 11–16 years | 0.188 | ** | (0.082) | 0.187 | ** | (0.082) | 0.199 | ** | (0.083) | 0.011 | (0.081) | −0.176 | ** | (0.083) | ||

| Yst. child older than 16 years | 0.134 | * | (0.071) | 0.132 | * | (0.071) | 0.139 | * | (0.071) | −0.084 | (0.072) | −0.216 | *** | (0.073) | ||

| Monthly household income, log. | 0.106 | ** | (0.050) | 0.105 | ** | (0.050) | 0.110 | ** | (0.049) | 1.314 | *** | (0.056) | 1.208 | *** | (0.056) | |

| Household size, log. | −0.332 | *** | (0.122) | −0.332 | *** | (0.122) | −0.329 | *** | (0.122) | −0.569 | *** | (0.122) | −0.237 | * | (0.122) | |

| Married | 0.115 | (0.077) | 0.115 | (0.077) | 0.119 | (0.077) | 0.090 | (0.078) | −0.025 | (0.080) | ||||||

| Living in owned home | 0.072 | * | (0.038) | 0.072 | * | (0.038) | 0.073 | * | (0.038) | −0.025 | (0.037) | −0.098 | *** | (0.037) | ||

| Living in an urban area | 0.070 | (0.060) | 0.070 | (0.060) | 0.070 | (0.060) | 0.072 | (0.058) | 0.002 | (0.060) | ||||||

| Man unemployed | −0.179 | *** | (0.055) | −0.170 | *** | (0.055) | −0.225 | *** | (0.062) | −0.559 | *** | (0.061) | −0.389 | *** | (0.059) | |

| Woman unemployed | 0.107 | ** | (0.052) | 0.104 | ** | (0.052) | 0.133 | * | (0.074) | −0.249 | *** | (0.053) | −0.353 | *** | (0.053) | |

| Man’s self-rated health | 0.121 | *** | (0.014) | 0.121 | *** | (0.014) | 0.121 | *** | (0.014) | 0.215 | *** | (0.015) | 0.094 | *** | (0.015) | |

| Woman’s self-rated health | −0.097 | *** | (0.015) | −0.097 | *** | (0.015) | −0.097 | *** | (0.015) | 0.078 | *** | (0.013) | 0.176 | *** | (0.014) | |

| Time fixed effects | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | |||||||||||

| Constant | −1.218 | *** | (0.414) | −1.244 | *** | (0.414) | −1.312 | *** | (0.418) | −6.046 | *** | (0.462) | −4.801 | *** | (0.466) | |

| Double Full-Time | Male Breadwinner Household | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | ||||||||

| Distribution factor | ||||||||||

| estimate, for | ||||||||||

| - couples | 1.988 | *** | (0.485) | 1.257 | *** | (0.376) | −0.235 | (0.443) | ||

| - men | 1.299 | *** | (0.480) | 0.204 | (0.329) | −0.657 | (0.453) | |||

| - women | −0.688 | (0.468) | −1.053 | *** | (0.379) | −0.422 | (0.404) | |||

| Estimate for the effect of | ||||||||||

| - man’s income | ||||||||||

| - on man’s SWHI | 0.010 | (0.064) | 0.117 | ** | (0.059) | 0.134 | *** | (0.047) | ||

| - on woman’s SWHI | 0.139 | ** | (0.063) | 0.220 | *** | (0.060) | 0.092 | *** | (0.032) | |

| - woman’s income | ||||||||||

| - on man’s SWHI | 0.124 | ** | (0.060) | 0.015 | (0.015) | −0.010 | (0.016) | |||

| - on woman’s SWHI | 0.047 | (0.056) | −0.012 | (0.016) | 0.005 | (0.015) | ||||

| Subsample mean of | ||||||||||

| - man’s SWHI | 6.795 | 6.714 | 6.497 | |||||||

| - woman’s SWHI | 6.887 | 6.847 | 6.646 | |||||||

| - satisfaction difference | −0.092 | −0.133 | −0.136 | |||||||

| - income ratio | 0.556 | 0.757 | 0.929 | |||||||

| n | 2525 | 3617 | 2436 | |||||||

| N | 8065 | 11,737 | 7097 | |||||||

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elsas, S. Income Sharing within Households: Evidence from Data on Financial Satisfaction. Soc. Sci. 2016, 5, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5030047

Elsas S. Income Sharing within Households: Evidence from Data on Financial Satisfaction. Social Sciences. 2016; 5(3):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5030047

Chicago/Turabian StyleElsas, Susanne. 2016. "Income Sharing within Households: Evidence from Data on Financial Satisfaction" Social Sciences 5, no. 3: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5030047

APA StyleElsas, S. (2016). Income Sharing within Households: Evidence from Data on Financial Satisfaction. Social Sciences, 5(3), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5030047