1. Introduction

Social support, both formal and informal, is widely recognized as a critical factor in promoting positive mental health outcomes (

LeFevre and Shaw 2012;

Choi et al. 2021). Beyond its psychological benefits, social support plays a key role in fostering individuals’ sense of safety and personal security, especially during periods of emotional distress or threat (

Evans and Feder 2016;

Schroevers et al. 2010). In such contexts, social support can offer protection and also contribute to an individual’s subjective feeling of being protected (

Gregory et al. 2017).

High-intensity intimate conflicts, particularly those involving separation or divorce, pose a substantial threat to the personal safety and emotional well-being of both partners (

Logan and Walker 2004). These periods often involve heightened hostility, verbal aggression, and psychological distress, which may or may not escalate into physical violence (

Capaldi et al. 2012). The emotional distress and uncertainty inherent in these conflicts amplify feelings of vulnerability and fear, making safety a pressing concern for both individuals involved.

Within this challenging context, social support emerges as a crucial protective factor for buffering the stress experienced by the individual receiving it and influencing the overall dynamics of the relationship. For instance, previous research suggests that social support can reduce feelings of fear and danger for women involved in conflictual relationships (

Coker et al. 2002;

Choi et al. 2021). However, less is known about how the distribution of that support, whether both, one, or neither partner receives it, affects perceived safety and risk. In some cases, when support is provided solely to one partner (e.g., the woman), the other partner (e.g., the man) may feel isolated, threatened, or even antagonized. This imbalance may inadvertently escalate the risk of hostility or violence, rather than de-escalating it. Thus, the implications of who receives support and who does not are critical for understanding the dynamics of danger and protection in intimate conflicts.

Due to both practical and cultural considerations, the current study included only women participants. In traditional societies, women are more likely to access social services and participate in research, making them more available for recruitment. Importantly, previous studies using tools like the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2;

Straus et al. 1996) support the validity of collecting data from one partner regarding both their own and their partner’s behaviors. In many such studies, women are required to report the man’s violence toward her as well as her own violence toward him (

Abramsky et al. 2011). Additionally, in sociocultural environments where masculinity norms emphasize strength and emotional control, men may underreport their own vulnerability or sense of danger (

Vandello et al. 2008). As such, relying on women’s perceptions offers valuable insight into the dynamics of conflict and danger in relationships.

This study aims to examine the differences in the feelings of danger experienced by men and women during high-intensity intimate conflicts, as compared to couples from the general population, based on women’s reports. It will also investigate how social support influences these feelings, focusing on four distinct scenarios: when neither partner has support, when only the woman has support, when only the man has support, and when both partners have support. These findings will contribute to our understanding of social support’s role in feelings of danger and protection while also offering deeper insight into the gender dynamics within high-intensity conflicts, including those that may escalate to violence.

1.1. Social Support

Social support is defined in the literature as the positive interactions an individual has with significant others, such as family and friends, who provide emotional, instrumental, and informational assistance (

Almedom 2005) targeted at protecting individuals and mitigating the negative consequences caused by a stressful situation (

Choi et al. 2021;

Sowan et al. 2023). Ultimately, social support reflects a person’s belief that he or she is loved, valued, and integrated into an interpersonal network of connections and mutual commitment (

Leary and DeRosier 2012).

Research into social support began in the middle of the last century and has become a major topic in social sciences due to its importance for and contribution to the promotion of personal and psychological well-being (

Oppedal et al. 2004;

Vinokur and van Ryn 1993). People who receive support from their social network develop a general sense of security that is fertile ground for positive behaviors, such as coping in a crisis (

Choi et al. 2021;

Schroevers et al. 2010).

Studies that have examined the differences in the seeking of social support among men and women have found that women turn to others for social support and receive social support more than men do (

Caetano et al. 2013). This is true in the context of intimate partner violence as well, and the literature indicates that women seek help more often than men do and that this help is usually informal support based on familial and social relationships (

Ansara and Hindin 2010). The social support that women receive helps them greatly to reduce the negative effects of violence (

Coker et al. 2002,

2003;

Thompson et al. 2000). This is seen particularly when a separation (or temporary separation) from a partner may detach them from their familiar and stable environment (

Beeble et al. 2009;

Bybee and Sullivan 2005).

The literature on social support has focused primarily on women seeking and receiving support, and very little is known about men seeking or receiving such support (formally or informally). This gap in the research literature may be due to a social perception that does not view men as legitimate and blameless victims in intimate relationships (

Ansara and Hindin 2010;

Tjaden and Thoennes 2000).

1.2. Sense of Danger

Researchers distinguish between two constructs of danger as it pertains to physical danger presented by other humans. Danger as a feeling refers to a human’s rapid, instinctive, and intuitive reactions to threatening situations and is described as an emotional indicator of fear. Meanwhile, danger as a cognitive perception refers to logical analysis of the likelihood of victimization (

Ferraro and LaGrange 1987;

Mesch 2000;

Slovic 2011). The first construct is typically measured in terms of “worry” about crime, while the second is typically measured in terms of “safety” from crime (

Ferraro and LaGrange 1987;

Mesch 2000;

Rader 2004).

The differences between men and women in terms of danger in the family setting have not been directly investigated. However, research on individuals’ fears around crime has provided consistent evidence that women and men differ in their perceptions and feelings of danger (

Harris and Miller 2000;

Slovic 1992,

1998,

2011). Women express higher levels of concern and fear about given risks than men do (

Stanko 1995;

Slovic 2011).

Harris and Miller (

2000) found that women generally perceive situations as more dangerous and respond with heightened anxiety, while men tend to downplay the risks even in identical scenarios. They also perceive and handle risks in different ways than men (

May et al. 2010). These high levels of women’s fear lead to greater engagement in behaviors such as dependence on others to ensure protection (

Chan and Rigakos 2002;

Rader 2008).

Many explanations have been proposed for why women express higher levels of fear. The explanation that has received the most consistent support in the literature comes from the field of sociology of gender—gender roles. This explanation states that men and women grow up in different ways and that, therefore, they adopt different behaviors, values, and attitudes (

Connell 1987;

Kimmel 2004). The sense of fear of danger may reflect concerns about the safety of others, which depends on women’s activities, roles, and living conditions (

Davidson and Freudenburg 1996). One reason for this is that, in the context of safety issues, the role of caregiver and nurturer is performed primarily by women. Another reason is that parents’ concern for the conduct of girls, over boys, leads girls to develop a greater sensitivity to and concern for risks (

Blackwell et al. 2002).

Beyond gender roles, societal power imbalances and systemic inequities also shape gendered perceptions of danger.

Procentese et al. (

2020), through in-depth interviews with social and health professionals, found that violence is often perceived as repetitive and normalized within patriarchal cultural contexts. This normalization reinforces gendered expectations about who is most at risk and shapes how danger is perceived. These structural conditions contribute to women’s heightened fear and sense of vulnerability, particularly in relation to intimate partner violence (

Johnson et al. 2024), and help explain persistent gender differences in the perception of danger.

Studies focused on gender differences in fear of physical risk from others have focused primarily on explaining why women fear victimization, yet little research has focused on the perception and fear of danger among men (

May et al. 2010). Even in the few studies that have taken men’s fear of danger into account, the focus has tended to be on men’s fear of danger to the other rather than men’s fears for their own safety (

May et al. 2010;

Warr and Ellison 2000). The little research that has focused on men’s fears for themselves indicates that men also fear danger, especially in situations in which they feel a loss of control or when they are confronted by other males (

Brownlow 2005;

Day et al. 2003).

1.3. Gender Differences in the Relationship Between Social Support and the Sense of Danger

The present study is based on gender-motivation theory. This theory focuses primarily on motivations that differentiate men and women in different life situations (

Winstok et al. 2017). The theory distinguishes between the motivation to raise one’s social status (status enhancement), which is stronger among men, and the motivation to reduce risk, which is stronger among women. A major principle of this theory is that the expression of that motivation is contingent and dependent on risk perception within the situation. For men in high-risk situations, the motivation to enhance status will be manifested as a willingness to confront others. However, in low-risk situations, this motivation will not come into play and, instead, avoidance or withdrawal from conflict will be observed.

The arguments of gender-motivation theory were supported by a study conducted by

Winstok and Straus (

2011) that examined gender differences in escalatory tendencies among the general population. In that study, participants were presented with hypothetical cases in which they experienced verbal and physical aggression from an unknown man, an unknown woman, and an intimate partner. The situations examined in that study represent different levels of perceived physical threat. The study’s assumption was that a male stranger’s aggression is perceived as more dangerous than that of a female stranger, and that the aggression of strangers is perceived as more dangerous than that of familiar, normative intimate partners. The results showed that among most men, the strongest escalatory tendency was present in situations involving unknown males (a high-risk situation); this tendency was weaker in situations involving unknown females (a moderate-risk situation) and weakest in situations involving their partners (a low-risk situation). Among most women, the strongest escalatory tendency was observed in situations involving their intimate partners (a low-risk situation); a weaker escalatory tendency was observed in situations involving unknown females (a moderate-risk situation), and the weakest escalatory tendency was observed in situations involving unknown males (a high-risk situation). This interpretation was further reinforced by

Cross and Campbell’s (

2012) study, which found that women were more aggressive toward their partners than toward others. In contrast, men were more aggressive toward their peers (of the same gender) than women were, including their intimate partners.

1.4. Living in a Conflictual Relationship

It is generally accepted that intimate relationships are the most important social relationships in an individual’s life. More than any other social context, those relationships are expected to provide a protected environment in which couples can thrive (

Hook et al. 2003;

Winstok 2012). Conflict is an inevitable part of these relationships; conflict is not negative or unproductive by itself, and its consequences relate to how the conflict is handled (

Markman et al. 1993;

Winstok 2012). When conflict is well managed, it has the potential to lead to more rewarding and satisfactory relationships (

Canary and Messman 2000). However, despite the constructive potential that may lie in a conflict, conflict is often perceived as a risk and evokes emotional and physiological responses similar to those evoked by other risks (

Kiecolt-Glaser and Newton 2001).

Unfortunately, sustained and unresolved marital conflict can create tension at home, erode the strength and satisfaction of relationships, and even negatively affect the health and well-being of both partners (

Hannibal and Bishop 2014;

Newsom et al. 2008;

Wood et al. 2007) and influence handling future conflicts (

Winstok 2012). High-intensity conflicts often involve a significant change from a close, personal, and harmonious relationship to one characterized by bitterness and antipathy (

Hopper 2001;

Johnston 1994). Research shows that living in an intensive conflictual relationship, including various expressions of hostility, as well as verbaleva and physical aggression (

Hopper 2001;

Sowan 2024;

Sowan-Basheer 2020).

Conflict in both populations is an integral part of the relationship. However, the frequency, severity, and process of escalating conflict might be different. Research shows that during conflict, families engaged in high-intensity conflict experience threat and loss of control greater than the general population and demonstrated additional tensions, as well as various expressions of hostility (

Hopper 2001;

Johnston 1994;

Sowan 2024).

1.5. Conceptual Framework and Research Hypotheses

As mentioned earlier, support is very important for one’s sense of personal security and safety (

Evans and Feder 2016), particularly during challenging periods and in situations that evoke a sense of actual and immediate danger. Therefore, the first research hypothesis is that there is an association between social support and the sense of danger. In addition, when a relationship faces high-intensity conflict (i.e., a separation process), an environment that was previously safe and protected becomes hostile, unpredictable, and even dangerous (

Hopper 2001;

Johnston 1994). Consequently, the second research hypothesis is that the sense of danger will be greater among couples whose relationships are characterized by high-intensity conflict than it will be among couples that have normative relationships. A review of literature also revealed that women express higher levels of concern and fear over risks (

Stanko 1995;

Slovic 2011). Although the literature notes such gender-related patterns, the current study does not explicitly examine gender differences between women and men. The third research hypothesis is that, based on women’s self-reports and their perceptions of their male partners, there will be differences in the reported sense of danger. Specifically, women are expected to report a stronger sense of danger for themselves compared to the level they attribute to their partners. Finally, many individuals consider social support to be a very important resource. Providing social support in an unbalanced way may violate the power balance in the relationship. Accordingly, the fourth research hypothesis is also framed based on women’s reports and their perceptions of their partners. It states that there is an association between the sense of danger and the identity of the recipient(s) of any social support. Accordingly, in women’s reports, the weakest sense of danger will be observed among couples in which both parties receive social support. The strongest sense of danger will be observed among couples in which both parties do not receive social support, and an intermediate level of danger will be found in cases in which only one party receives social support.

2. Methods

The participants in the first subsample (general population) ranged in age from 20–54 years. The mode age was 30 years, the median age was 34.50, and the average age was 34.23 years (SD = 7.12). Partners ranged in age from 25–60 years, with an average age of 38.96 years (SD = 7.88). The average number of years of cohabitation was 11.17 (SD = 6.38). The number of children per couple ranged from one to five. The average number of children per couple was 2.67 (SD = 1.25). In this subsample, 87.1% of the participants were Muslim, and 12.9% were Christian. In this subsample, 7.1% of the participants had studied for fewer than 12 years, 51.4% had a full secondary education, and 41.4% held an academic degree. In addition, 31.5% of the participants did not work, and approximately 68.6% worked at least part-time. Finally, 10% of the participants reported that their economic status was above average, 54.3% reported that it was about average, and 35.7% reported that it was below average.

In the research population subsample, the participants ranged in age from 20–56 years. The mode age was 30 years, the median age was 34, and the average age of participants was 35.4 years (SD = 6.99). Partners ranged in age from 26–57 years, with an average age of 39.66 years (SD = 6.18). The average number of years of cohabitation was 9.26 (SD = 5.77). The number of children per couple ranged from one to five. The average number of children per couple was 2.61 (SD = 1.08). The vast majority of the participants (88.4%) were Muslim, and 11.6% were Christian. Among the first group, 17.9% of the participants had studied for less than 12 years, 47.4% had a full secondary education, and 34.8% held an academic degree. In addition, 34.8% of the participants did not work, and approximately 65.2% worked at least part-time. Finally, 4.2% of the participants reported that their economic status was above average, 45.3% reported that it was about average, and 50.5% reported that it was below average. Demographic data are presented in

Table 1. The background characteristics of this subsample are presented in

Table 1.

The study was approved by the University of Haifa Committee for Ethical Research with Humans (permit no. 1882). For the high-intensity conflict group, social workers in welfare departments were contacted to identify and recruit eligible women who were actively engaged in the legal process of separation or divorce, representing a period of heightened interpersonal conflict and transition. A key inclusion criterion for this group was that participants were no longer co-residing with their separating partner; all women in this sample were living separately at the time of data collection. These social workers were guided on the ethical considerations and rights of the study participants and on how to facilitate questionnaire completion. Both verbally and in writing, the purpose, importance, and subjects of the study were emphasized, as well as the ways in which the participants should answer the questions. In addition, the participants were assured, in writing and orally, that their anonymity would be protected, that their responses would be kept confidential, and that they had the right to stop at any stage and to choose not to answer some of the questions. The participants filled out the questionnaires in Arabic, in a separate room, without the social worker’s presence.

The general population subsample was a convenience sample, recruited via a snowball method by the research team. The key inclusion criteria were not being in the care of social services, living a normative lifestyle, and not having experienced any significant clashes with their partners indicating a relationship crisis. Women who met those criteria were invited to participate in the study, and each participant was given a copy of the questionnaires to complete. The participants completed the questionnaires at home after receiving the same instructions and explanations as the other subsample group.

2.1. Measuring Instruments

This study used three questionnaires: a sociodemographic questionnaire, a questionnaire that examined social support received by each spouse, and a questionnaire that examined the sense of danger from the partner.

2.2. Sociodemographic Questionnaire

This questionnaire asked about background variables such as gender, age, marital status, number of children, education, religion, and economic status.

2.3. Questionnaire That Examined Social Support Received by Each Spouse

The questionnaire that examined the Social Support received by each spouse was based on the multidimensional scale of perceived social Support (

Zimet et al. 1988). This questionnaire had two parts. In the first part, participants rated the levels of support they receive from their social environment. In the second part, they rated the amount of support that they estimate their spouse receives. Each part consisted of 12 items (24 items overall). Each item referred to a specific source of support, such as a father, brother, neighbor, etc. For each item, the questionnaire asked:

How true is it to say that you receive significant support from this source? The participants were asked to respond in terms of a sequence of intensity levels:

very high (5),

high (4),

medium (3),

low (2), or

not at all (0). Reliability in terms of the internal consistency of the items was acceptable (α Cronbach

(women) = 0.80; α Cronbach

(men) = 0.85). A new variable was created for women and men based on the average of the 12 items. Average values greater than 2 were considered as “getting social support”, and average values below or equal to 2 were considered as” not getting support”. Based on this variable, a new variable was created, which we refer to as

topology of social support. That variable had four levels: both partners received social support, only the woman received social support, only the partner received social support, and neither partner received social support.

2.4. Questionnaire That Examined the Sense of Danger from the Partner

This questionnaire also had two parts. The first part included seven items describing the women’s own sense of danger from their partners, covering both psychological and emotional threats as well as potential for physical harm. The second part included seven items that described women’s estimations of their male partners’ sense of danger from them. These items similarly aimed to capture the partner’s perceived psychological/emotional insecurity and potential physical threat. For each item, participants responded to the question: How true is it to say that the following statement is true for you? Participants were asked to respond in terms of a sequence of intensity levels: very high (5), high (4), medium (3), low (2), or not at all (0). A new variable was created for women who received support, based on the average of the seven items, as well as for men. Reliability in terms of internal consistency was acceptable (α Cronbach(men) = 0.79; α Cronbach(women) = 0.88).

3. Results

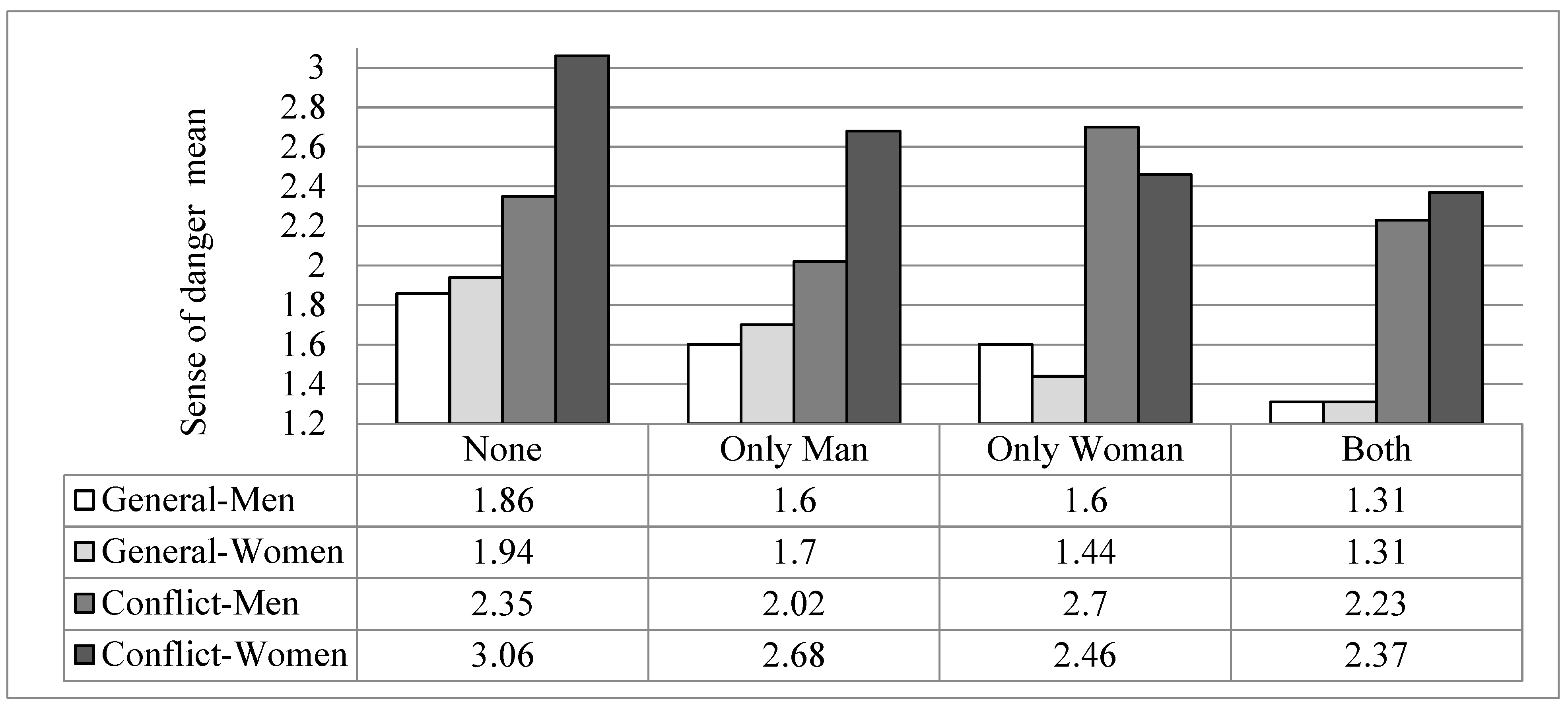

Repeated measures were performed to examine the sense of danger among respondents from the two subsamples (i.e., high-intensity conflict and general population). In this analysis, the dependent variable was the sense of danger as experienced by the women themselves and as estimated by them for their partners. There were three independent variables: type of report (women’s own perception vs. women’s estimation of their partner’s perception), subsample type (i.e., high-intensity conflict or the general population), and social-support recipient(s) (i.e., neither partner received social support, only the man received social support, only the women received social support, or both partners received social support). The inferential statistics from our analysis are presented in

Table 2.

As shown in

Table 2, the identity of the subsample had a significant effect on the intensity of the sense of danger (F

(1157) = 172.65;

p < 0.001;

η2 = 0.52). Specifically, the level of perceived danger was greater among the high-intensity conflict subsample (M = 2.45, SD = 0.05) than among the general population subsample (M = 1.50, SD = 0.06). These results support our first hypothesis.

The analysis also showed that the type of report (women’s own perception vs. their estimation of their partner’s perception) had a significant effect on the level of perceived danger (F(1157) = 17.68, p < 0.001; η2 = 0.10). The descriptive statistics showed that the intensity of the sense of danger was greater among women’s reported perceptions (M = 2.06, Std. Error = 0.05) than it was among men (M = 1.89, SD = 0.04). These results indicate that the second hypothesis was also supported.

The identity of the recipient(s) of any social support also had a significant effect on the intensity of the perceived danger (F(3157) = 7.83; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.13). The intensity of risk perceived by members of couples who received no social support was greater (M = 2.22, Std. Error = 0.07) than that observed by the other groups. Lower levels of perceived danger were observed among the group in which only the woman received social support (M = 2.00, Std. Error = 0.07). Even lower levels of perceived danger were observed among couples in which only the man received social support (M = 1.89, Std. Error = 0.09). The lowest levels of perceived danger were observed among couples in which both partners received social support (M = 1.81, Std. Error = 0.05).

Significant results were also obtained from the analysis of the following interactions: the two-way interactions between type of report and type of population and between type of report and the social-support object, and the three-way interaction between type of report, population type, and the recipient(s) of any social support. Descriptive statistics for the three-way interaction are presented in

Table 2.

As shown in that figure, the highest levels of perceived danger were observed among women in high-intensity conflicts when reporting on their own sense of danger in cases in which neither partner received social support (M = 2.91, Std. Error = 0.12). Levels of perceived danger were lower among couples in which only the man received social support (M = 2.75, Std. Error = 0.14) and much lower among couples in which only the woman received social support (M = 2.39, Std. Error = 0.09). The lowest levels of perceived danger were observed among couples in which both partners received social support (M = 2.40, Std. Error = 0.08). The sense of danger among the women in the high-intensity conflict group was greater than that observed among women from the general population, regardless of the identity of the recipient(s) of any social support. The strongest sense of danger among women from the general population was found in cases in which neither partner received social support (M = 1.79, Std. Error = 0.11). The next strongest sense of danger was reported by women in situations in which only their partner received social support (M = 1.48, SE = 0.14). Much lower levels of perceived danger were reported by women in situations in which only they received social support (M = 1.43, Std. Error = 0.18), and the weakest sense of danger was reported by women in situations in which both partners received social support (M = 1.32, Std. Error = 0.09).

Figure 1 shows that the sense of danger among women in the high-intensity conflict group, whether based on their own perceptions or their estimates of their partners’ experiences, was greater than that observed among women from the general population. Within the high-intensity conflict group, when women reported on their own or their partners’ sense of danger, the strongest sense of danger was observed when only the woman received social support (M = 2.54, Std. Error = 0.10). A weaker sense was observed when neither spouse received social support (M = 2.36, Std. Error = 0.10). A much weaker sense was found in women’s estimates of their partners’ experiences when both partners received social support (M = 2.22, SE = 0.07), and the weakest sense was observed in women’s estimates of their partners’ experiences when only the man received social support (M = 2.06, Std. Error = 0.12).

Figure 1 also shows that in the general population group, for women reporting on their own or their partners’ sense of danger, the strongest sense was in women’s estimates of their partners’ experiences when neither spouse received social support (M = 1.83, Std. Error = 0.09). A weaker sense was found in women’s own reports when only the woman received social support (M = 1.54, Std. Error = 0.14), and the weakest senses were found in women’s own reports when either both partners received social support or only the man received social support (M = 1.31, Std. Error = 0.08).

These findings show that the sense of danger was stronger in both women’s own reports and in their estimates of their partners’ experiences in relationships characterized by high-intensity conflict than it was among men and women (reporting their own perceptions or estimating their partner’s perceptions) from the general population. The findings also show that social support significantly affected the sense of danger. In most cases, social support moderated the sense of danger. In both subsamples, the lowest levels of perceived danger were observed in situations in which both partners received social support. There is an exception in the case of men in relationships characterized by high-intensity conflict in situations in which only the wife received social support. In these cases, the estimated sense of danger for the partner was the strongest. Here, the social support of the partner added to the perceived threat. For men, in cases in which there is a balance in men’s and women’s social support (both have or do not have support), the perceived threat is weaker than it is in cases in which the woman receives support and the man does not. Social support is perceived as a source of power. If it is recruited for the man’s benefit, the man feels less threatened. However, if it is recruited solely for the woman’s benefit, then the man feels more threatened.

4. Discussion

The current research aims to examine the differences in the feelings of danger experienced by women themselves versus their estimates of their partners’ feelings of danger who are experiencing high-intensity intimate conflicts, as compared to couples from the general population. As mentioned earlier, intimate relationships are the most important social relationships in an individual’s life. More than any other social context, these relationships are expected to provide a protected environment in which couples can thrive (

Hook et al. 2003;

Winstok 2012). Intensive conflicts and separation processes often involve a significant change from a close, personal, and harmonious relationship to a conflictual relationship characterized by bitterness and antipathy (

Johnston 1994) that may include various expressions of hostility, as well as verbal and physical aggression (

Hopper 2001).

Our analysis showed that the first hypothesis, which postulated that there is an association between social support and the sense of danger, was supported. That is, the higher the level of social support, the weaker the sense of danger. This finding is consistent with literature findings on social support, which have demonstrated that social support contributes to the promotion of personal and psychological well-being and a sense of safety (

Oppedal et al. 2004). A possible explanation could be that social support gives an individual a feeling that he or she is not alone and that there are others who can be trusted and who will provide their support. This inner feeling that someone shares our experience reduces the intensity of the sense of danger (

Vinokur and van Ryn 1993). This finding aligns with more recent work emphasizing the stress-buffering effects of social support in various challenging life circumstances, including relational difficulties (e.g.,

Liu et al. 2021;

Ghafari et al. 2021).

The second hypothesis, which postulated that the sense of danger is stronger among couples engaged in high-intensity conflicts than among couples in the general population, was also supported. This finding is consistent with literature findings on families experiencing high-intensity conflicts and/or families that have gone through separation processes, which have demonstrated that those processes create additional conflicts and tensions, as well as various expressions of hostility (

Hopper 2001;

Johnston 1994). A possible explanation is that the divorce/separation process is a transitional stage between the known and familiar environment and a new stage that is shrouded in mystery and uncertainty. This unpredictable stage may produce more opportunities for friction and confrontation. The persistent relevance of these earlier findings highlights the enduring nature of distress during high-intensity conflict, a pattern consistently observed across decades of research despite societal or relational shifts.

The third research hypothesis, which postulated that there is an association between women’s own perceptions versus their estimates of their partners’ perceptions and the sense of danger, was also supported; the sense of danger experienced by women themselves is stronger than what they estimate is experienced by their partners. This finding is consistent with previous research that has shown that women express higher levels of concern and fear than men do over the same risks (

Stanko 1995;

Slovic 2011). The stronger sense of danger may reflect concerns for the safety of others, which are more characteristic of women (

Blackwell et al. 2002). It is important to note that the current findings regarding “men” actually represent women’s perceptions of their partners’ feelings rather than direct reports from men themselves. Therefore, interpretations should be made with caution, as these perceptions may be influenced by women’s own experiences, beliefs, or emotional states. This long-established gender difference in risk perception continues to be documented in contemporary studies, reinforcing the idea that gender roles and societal expectations shape how individuals experience and report feelings of danger (e.g., studies on fear of crime or vulnerability).

The last research hypothesis, which postulated that there is a correlation between the sense of danger and the identity of the recipient(s) of any social support, was also supported. Accordingly, the weakest sense of danger was reported among couples in which both spouses receive social support and the highest levels of perceived danger were reported by women who indicated that both they and their partners received social support, whereas the highest levels of perceived danger were reported by women who indicated that neither received support or that only one received support. They feel that they are not alone in facing the situation and that there are others whom they can trust (

Oppedal et al. 2004). This tendency was stronger according to women’s reports about relationships in high-intensity conflicts. It seems that when both parties receive support, women perceive that neither they nor their partners are alone in facing the situation and that there are others whom they each can trust. However, when only one party receives support, women may perceive that their partners feel a loss of balance or power, potentially increasing perceived threat levels. This finding, particularly the exacerbation of perceived danger when support is unbalanced, is a crucial contribution, especially given the relative scarcity of recent research explicitly investigating the dyadic and potentially negative implications of asymmetrical social support within high-conflict intimate relationships. While foundational work exists on power dynamics, the direct link to perceived danger based on the distribution of social support within a couple’s conflict appears to be an area ripe for further contemporary investigation.

4.1. Theoretical Implications for Conflicts During the Separation Process

The results from this study shed light on social support as an important factor that affects couples’ behavior during conflict and is associated with the sense of danger within the couple. These results indicate that social support, as reported by women, is associated with both their own perceived sense of danger and their estimates of their partners’ perceived danger. The more social support is offered, the weaker the sense of danger will be. This correlation is stronger according to women’s reports about couples involved in a separation process and appears particularly pronounced when women perceive that only one partner receives social support.

Our assumption is that social support can serve as an important resource that may reduce women’s perceived sense of danger in conflictual relationships. Therefore, interventions should consider providing support to both partners whenever possible. At the same time, the supply of support should be well considered. Providing support to only one partner may, according to women’s reports, increase their perception that the other partner feels threatened, which they associate with heightened hostility and conflict. These interpretations, however, should be viewed cautiously because the present study did not include direct reports from men. In other words, unbalanced social support (i.e., support provided to only one party) does not necessarily have a positive effect. On the contrary, it may exacerbate the conflict.

Finally, according to gender-motivation theory (

Winstok et al. 2017), as risk levels rise, men may be more likely to engage in confrontational responses. Conflictual relationships and separation processes may be perceived by some men as threatening and may lead to a perceived loss of control (

Brownlow 2005;

Day et al. 2003;

Hopper 2001). In the context of the current study, however, these interpretations are based solely on women’s reports and theoretical assumptions rather than men’s self-reported experiences. Therefore, while women who receive support may feel more protected, their perceptions suggest that this could potentially increase the perceived threat attributed to their partners—an interpretation that requires further research with data collected directly from men. This emphasizes the need for a nuanced understanding of social support interventions in conflict, moving beyond a simplistic “more is better” approach to consider the relational context and potential unintended consequences, a perspective increasingly recognized in contemporary relationship research.

4.2. Limitations and Implications for Practice and Research

Despite the importance of the current study, there are a number of limitations to be addressed. First, the ability to generalize these findings is limited. The population examined in this study was a community sample that is not necessarily representative of the entire population of couples engaged in high-intensity conflict. The second limitation of this research is that this was a cross-sectional, rather than a longitudinal study, and as such, it does not allow for the drawing of any conclusions regarding causal relationships. The third limitation is that the present study examined the study variables that related to men from their wives’ perspective. The subjective experience is personal, and, therefore, it would be more accurate to interview men directly. Nevertheless, this work represents an important contribution to our understanding of the relationship between social support and the sense of danger in conflictual intimate partner relationships and has important practical implications.

The research limitations provide a guide for future research recommendations. First, subsequent studies should seek to expand the theoretical frameworks that can be used to examine the phenomenon. For example, cultural and personal variables such as religion, religiosity, and attitudes toward gender roles should be included. The comparative basis of the study should also be extended. Another limitation of this study is the exclusive inclusion of women participants. While this decision was guided by practical considerations, relying on women’s reports to assess the male partner’s perception of danger may introduce bias. Future studies should aim to incorporate men’s self-reports to more fully capture gendered experiences of conflict and perceived threat.

5. Conclusions

The main finding of this work is that the level of perceived danger is associated with social support. The more social support that is provided, the weaker the sense of danger as reported by women regarding their own experiences and their perceptions of their partners’ experiences. Because this study did not include men’s self-reports, conclusions about men’s actual behaviors should be interpreted cautiously. Women’s responses suggest that they may perceive their partners as more unpredictable or hostile when support is unbalanced, but these are subjective estimates rather than direct evidence of men’s behavior. Therefore, when providing social support to couples, individuals should take into account the possibility (based on women’s perceptions) that support provided to only one partner could increase the perceived sense of danger attributed to the other partner, potentially heightening tension and conflict. This underscores the critical need for a nuanced, dyadic perspective when considering social support interventions in intimate partner conflict, especially in high-stakes situations like separation, while acknowledging that the present findings are based solely on women’s reports and that future studies should incorporate data from both partners to validate these interpretations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.S.; methodology, W.S. and A.S.; software, W.S.; validation, W.S. and A.S.; formal analysis, W.S.; investigation, W.S.; resources, W.S. and A.S.; data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, W.S.; writing—review and editing, W.S. and A.S.; visualization, W.S.; supervision, W.S.; project administration, W.S.; funding acquisition, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Approval was obtained from the University of Haifa Committee for Ethical Research with Humans (permit no. 1882).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. In addition, all methods were performed in accordance with the University of Haifa Committee for Ethical Research with Humans guidelines and regulations.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abramsky, Tanya, Charlotte H. Watts, Claudia Garcia-Moreno, Karen Devries, Ligia Kiss, Mary Ellsberg, Henrica Afm Jansen, and Lori Heise. 2011. What factors are associated with recent intimate partner violence? Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. BMC Public Health 11: 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almedom, Astier M. 2005. Resilience, hardiness, sense of coherence, and posttraumatic growth: All paths leading to light at the end of the tunnel? Journal of Loss and Trauma 10: 253–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansara, Donna L., and Michelle J. Hindin. 2010. Formal and informal help-seeking associated with women’s and men’s experiences of intimate partner violence in Canada. Social Science & Medicine 71: 1011–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeble, Melissa L., Deborah Bybee, Cris M. Sullivan, and Angela E. Adams. 2009. Main, mediating, and moderating effects of social support on the well-being of survivors of intimate partner violence across 2 years. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 77: 718–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, Brenda S., Christopher S. Sellers, and Sarah M. Schlaupitz. 2002. A power-control theory of vulnerability to crime and adolescent role exits—Revisited. Canadian Review of Sociology 39: 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlow, Alec. 2005. A geography of men’s fear. Geoforum 36: 581–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Deborah, and Cris Sullivan. 2005. Predicting re-victimization of battered women 3 years after exiting a shelter program. American Journal of Community Psychology 36: 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caetano, Simone C., Claudia Silva, and Mario V. Vettore. 2013. Gender differences in the association of perceived social support and social network with self-rated health status among older adults: A population-based study in Brazil. BMC Geriatrics 13: 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canary, Daniel J., and Susan J. Messman. 2000. Relationship conflict. In Close Relationships: A Sourcebook. Edited by Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 261–270. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi, Deborah M., Nicole B. Knoble, Jennifer W. Shortt, and Hyoun K. Kim. 2012. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse 3: 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Wing, and George Rigakos. 2002. Risk, crime and gender. British Journal of Criminology 42: 743–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Angel W. M., Ben C. Y. Lo, Raymond T. F. Lo, Patrick Y. L. To, and Jessie Y. H. Wong. 2021. Intimate partner violence victimization, social support, and resilience: Effects on the anxiety levels of young mothers. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 36: NP12299–NP12323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, Ann L., Katherine W. Watkins, Paige H. Smith, and Heidi M. Brandt. 2003. Social support reduces the impact of partner violence on health: Application of structural equation models. Preventive Medicine 37: 259–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, Ann L., Paige H. Smith, Michael P. Thompson, Robert E. McKeown, Linda Bethea, and Karen E. Davis. 2002. Social support protects against the negative effects of partner violence on mental health. Journal of Women’s Health and Gender-Based Medicine 11: 465–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, Raewyn W. 1987. Gender and Power. Sydney: Allen and Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, Catharine P., and Anne Campbell. 2012. The effects of intimacy and target sex on direct aggression: Further evidence. Aggressive Behavior 38: 272–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, Debra J., and William R. Freudenburg. 1996. Gender and environmental risk concerns: A review and analysis of available research. Environment & Behavior 28: 302–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, Kristen, Candace Stump, and Daisy Carreon. 2003. Confrontation and loss of control: Masculinity and men’s fear in public space. Journal of Environmental Psychology 23: 311–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Megan A., and Gene Feder. 2016. Help-seeking amongst women survivors of domestic violence: A qualitative study of pathways towards formal and informal support. Health Expectations 19: 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraro, Kenneth F., and Randy L. LaGrange. 1987. The measurement of fear of crime. Sociological Inquiry 57: 70–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafari, Reza, Akram Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, and Elnaz Nasiri. 2021. Social support and mental health: The mediating role of perceived stress. BMC Public Health 21: 10497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, Alison, Gene Feder, Ann Taket, and Emma Williamson. 2017. Qualitative study to explore the health and well-being impacts on adults providing informal support to female domestic violence survivors. BMJ Open 7: e014511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannibal, Kara E., and Mark D. Bishop. 2014. Chronic stress, cortisol dysfunction, and pain: A psychoneuroendocrine rationale for stress management in pain rehabilitation. Physical Therapy 94: 1816–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Mary B., and Kathleen C. Miller. 2000. Gender and perceptions of danger. Sex Roles 43: 843–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, Misty K., Lawrence H. Gerstein, Lisa Detterich, and Barbara Gridley. 2003. How close are we? Measuring intimacy and examining gender differences. Journal of Counseling & Development 81: 462–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, Joseph. 2001. The symbolic origins of conflict in divorce. Journal of Marriage and Family 63: 446–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Nicole L., Michelle Benner, Nicole S. Lipp, Cassandra F. Siepser, Zarmeen Rizvi, Zhen Lin, and Emily Calene. 2024. Gender inequality: A worldwide correlate of intimate partner violence. Women’s Studies International Forum 107: 103016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, Janet R. 1994. High-conflict divorce. Future of Children 4: 165–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., and T. L. Newton. 2001. Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin 127: 472–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmel, Allan J. 2004. Rumors and Rumor Control: A Manager’s Guide to Understanding and Combatting Rumors. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, Kimberly A., and Melissa E. DeRosier. 2012. Factors promoting positive adaptation and resilience during the transition to college. Psychology 3: 1215–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeFevre, Ann L., and Thomas V. Shaw. 2012. Latino parent involvement and school success: Longitudinal effects of formal and informal support. Education and Urban Society 44: 707–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Yong, Shujun Li, Hongbo Wang, and Yanhong Zhang. 2021. Social support, resilience, and self-esteem protect against common mental health problems in early adolescence: A nonrecursive analysis from a two-year longitudinal study. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 641490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, T. K., and Robert Walker. 2004. Separation as a risk factor for victims of intimate partner violence: Beyond lethality and injury: A response to Campbell. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 19: 1478–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markman, Howard J., Mari Jo Renick, Frank Floyd, Scott M Stanley, and Mari L. Clements. 1993. Preventing marital distress through communication and conflict management training: A 4- and 5-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 61: 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, David C., Nicole E. Rader, and Sarah Goodrum. 2010. A gendered assessment of the threat of victimization: Examining gender differences in fear of crime, perceived risk, avoidance, and defensive behaviors. Criminal Justice Review 35: 159–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesch, Gustavo. 2000. Perceptions of risk, lifestyle activities, and fear of crime. Deviant Behavior: An Interdisciplinary Journal 21: 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsom, Jason. T., Tyrae L. Mahan, Karen S. Rook, and Neal Krause. 2008. Stable negative social exchanges and health. Health Psychology 27: 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppedal, Brit, Espen Røysamb, and David L. Sam. 2004. The effect of acculturation and social support on change in mental health among young immigrants. International Journal of Behavioral Development 28: 481–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procentese, Fortuna, Raffaella Fasanelli, Sabrina Carnevale, Stefano Gherardo, Vincenzo Bellino, Luigi Gualtieri, Chiara Marano, and Immacolata D. Napoli. 2020. Downside: The perpetrator of violence in the representations of social and health professionals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 7061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rader, Nicole E. 2004. The threat of victimization: A theoretical reconceptualization of fear of crime. Sociological Spectrum 24: 689–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rader, Ronald. 2008. Expression systems for process and product improvement. Bioprocess International 6: 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Schroevers, Maya, Vicki Helgeson, Robbert Sanderman, and Anja Ranchor. 2010. Type of social support matters for prediction of posttraumatic growth among cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology 19: 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, Paul. 1992. Perceptions of risk: Reflections on the psychometric paradigm. In Theories of Risk. Edited by Dominic Golding and Sheldon Krimsky. New York: Praeger, pp. 117–52. [Google Scholar]

- Slovic, Paul. 1998. The risk game. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 59: 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, Paul. 2011. The feeling of risk: New perspectives on risk perception. Energy & Environment 22: 835–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowan, Wafaa. 2024. A conflict escalation comparison: Couples from the general population and couples engaged in high-intensity conflict. Family Relations 73: 858–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowan, Wafaa, Talia Kochli-Hailovski, and Miri Cohen. 2023. Objective and subjective stress among grandparents providing assistive regular grandchild care. Journal of Applied Gerontology 42: 1820–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowan-Basheer, Wafaa. 2020. The effect of gender on negative emotional experiences accompanying Muslims’ and Jews’ use of verbal aggression in heterosexual intimate-partner relationships. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 29: 332–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanko, Elizabeth A. 1995. Women, crime, and fear. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 539: 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, M. A., S. L. Hamby, S. U. E. Boney-McCoy, and D. B. Sugarman. 1996. The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2) development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues 17: 283–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Robert S., Frederick P. Rivara, Donald C. Thompson, William E. Barlow, Nancy K. Sugg, Richard D. Maiuro, and David M Rubanowice. 2000. Identification and management of domestic violence: A randomized trial. Preventive Medicine 19: 253–63. [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden, Patricia, and Nancy Thoennes. 2000. Prevalence and consequences of male-to-female and female-to-male intimate partner violence as measured by the National Violence Against Women Survey. Violence Against Women 6: 142–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandello, Joseph Alan, Dov Cohen, and Sean Ransom. 2008. U.S. Southern and Northern differences in perceptions of norms about aggression: Mechanisms for the perpetuation of a culture of honor. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 39: 162–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinokur, Amiram D., and Maury van Ryn. 1993. Social support and undermining in close relationships: Their independent effects on the mental health of unemployed persons. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 65: 350–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warr, Mark, and Christopher Ellison. 2000. Rethinking social reactions to crime: Personal and altruistic fear in family households. American Journal of Sociology 106: 551–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winstok, Zeev. 2012. A New Paradigm for Understanding Conflict Escalation. The Springer Series on Human Exceptionality. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Winstok, Zeev, and Murray Straus. 2011. Gender differences in intended escalatory tendencies among marital partners. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 26: 3599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winstok, Zeev, Miri Weinberg, and Rinat Smadar-Dror. 2017. Studying partner violence to understand gender motivations—Or vice versa? Aggression and Violent Behavior 34: 120–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Robert G., Brian Goesling, and Sarah Avellar. 2007. The Effect of Marriage on Health: A Synthesis of Recent Research Evidence. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Zimet, Gregory, Nancy Dahlem, Sara Zimet, and Gordon Farley. 1988. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment 52: 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).