Political Ecology as an Analytical Tool in the Mezquital Valley, Mexico: A Permanent Struggle

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical and Geographical Framework

2.1. Approach to Accumulation Mechanisms

2.2. Social Organizations Around the Conflict

3. Methodology

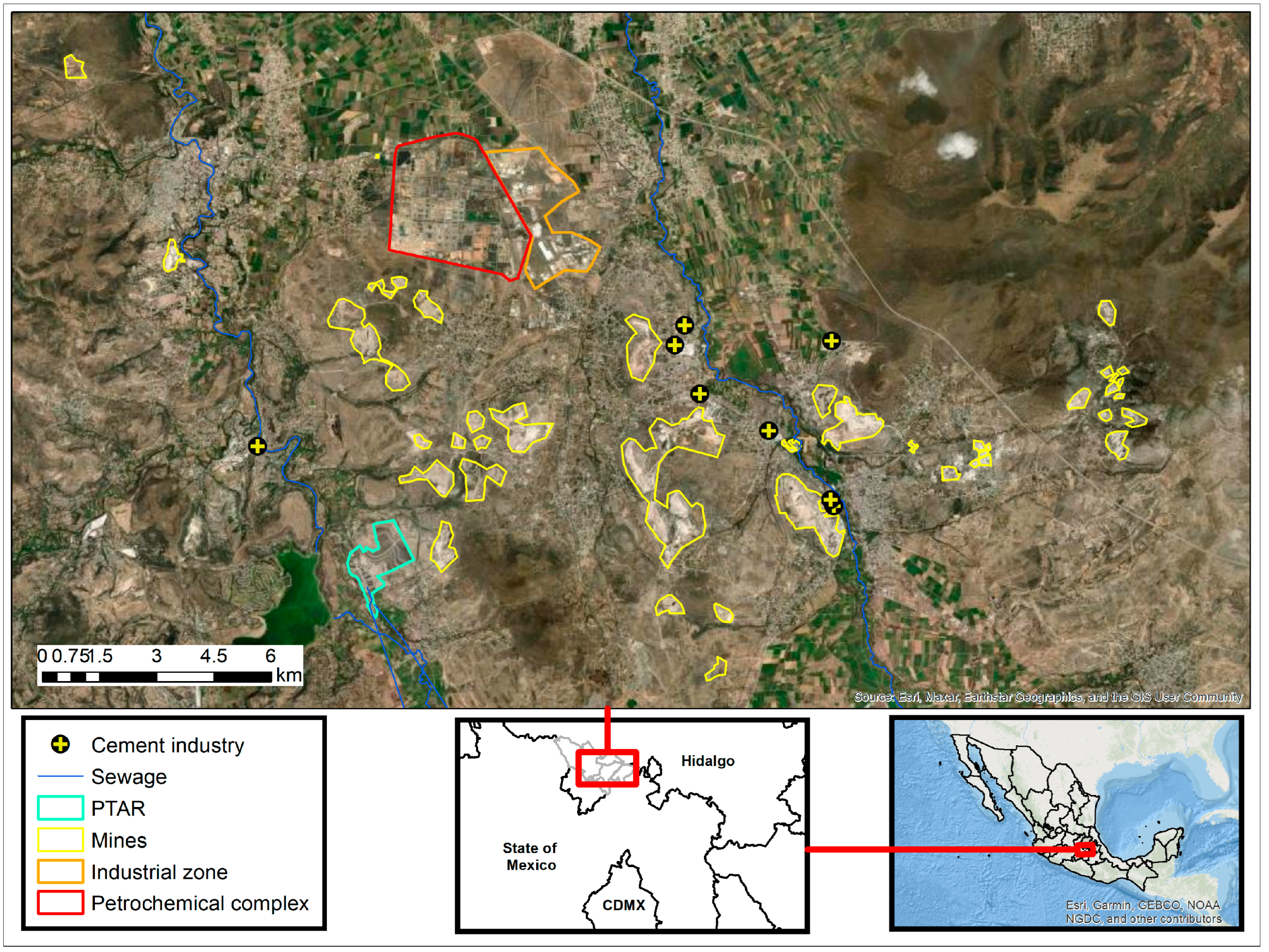

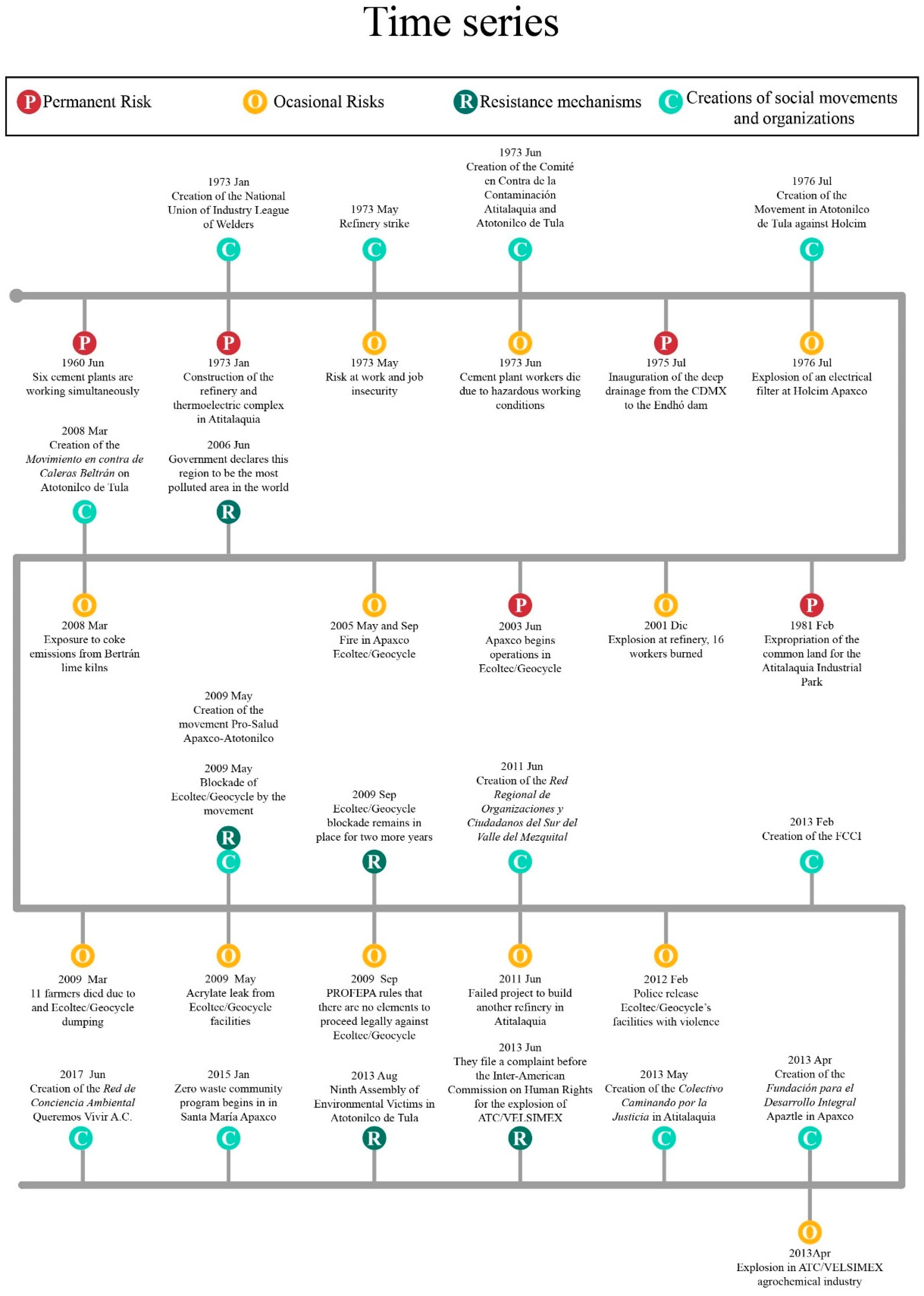

4. Results

4.1. Regarding Accumulation Mechanisms

quienes las explotan son grupos de ejidatarios o particulares que rentan y pagan muy poquito 6 pesos por tonelada (0.25 USD/TON).

The ones who exploit them are groups of ejidatarios or individuals who rent and pay very little, 6 pesos per ton (0.25 USD/TON).

Sí, sí, claro, el precio del forraje en la región está en función de la demanda de leche de un establo que está por acá por Tequixquiac. Que es administrado por gente de Alpura, y que es el que fija los precios en la zona. Nadie más.

Yes, yes, of course, the price of forage in the region is based on the demand for milk from a ranch that is around here in Tequixquiac. Which is managed by people from Alpura, and they’re the ones that set the prices in the area. No one else.

4.2. Emergence and Evolution of Social Organizations Around the Conflict

Y me dicen “¿sabes lo que te quieren hacer?” Y digo: ¿no? Dice, “bueno, te van a meter preso y no vas a salir,” dice. “Yo te aconsejo que no vayas,” y dije, no carajo, pero esa citación decía que si no me presentaba a declarar (en las instalaciones penitenciarias) iban a venir a buscarme a la fuerza.

And they say to me, “Do you know what they want to do to you?” And I say, no? He says, “Well, they’re going to put you in jail, and you won’t get out,” he says. “I advise you not to go.” And I said, no damn it, but that summons said that if I didn’t show up to testify (in the penitentiary facilities), they were going to come and get me by force.

Me parece una barbaridad que haya gente que tenga que ir, bueno, o sea, el municipio proporciona una ambulancia, pero es una barbaridad que los tengan que transportar de la región hacia el sur de la CDMX, para diálisis y luego de regreso. Es decir, después, regresar en ambulancia por más, como si fuera un colectivo, es decir, ¿una ambulancia para 8 personas? Y entonces a la primera, que ya regresó de su diálisis, le hacen pasar por el calvario de terminar todo esto, que ahí no haya un centro de salud, en condiciones de atender a la gente sobre los problemas que ahí se generan, eso es algo lamentable.

It seems outrageous to me that there are people who have to go, well, I mean, the municipality provides an ambulance, but it’s outrageous that they have to be transported from the region to southern CDMX for dialysis and then back. That is to say, later, returning in an ambulance for more, as if it were a bus, I mean, an ambulance for 8 people? And then the first one, who has already returned from their dialysis, has to go through the ordeal of finishing all this, that there isn’t a health center there, that’s able to attend to the people because the problems that arise there; it’s awful.

No somos mexicanos de segunda, nuestras vidas también valen [haciendo referencia a que los de primera son los habitantes de la CDMX] No somos mexicanos de segunda, ¿cuál es la diferencia entre un chilango [habitante de la CDMX] y yo?

We are not second-class Mexicans; our lives matter too [referring to those of first-class as the inhabitants of CDMX]. We are not second-class Mexicans, what makes a chilango [inhabitant of CDMX] different from me?

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albert, Lilia América, and Jacott Marisa. 2015. México Tóxico: Emergencia Química. Ciudad de México: Siglo XXI Editores, p. 310. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, Paul. 2020. Movimientos sociales, La estructura de la acción colectiva. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires: CLACSO, p. 374. [Google Scholar]

- Andreucci, Diego, García-Lamarca Melisa Jonah Wedekind, and Erick Swyngedouw. 2017. “Value Grabbing”: A Political Ecology of Rent. Capitalism Nature Socialism 28: 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arboleda, Martín. 2020. Planetary Mine, Territories of Extraction Under Late Capitalism. Brooklyn: Verso, US, ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-296-3. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Ulrich. 1998. La Sociedad del Riesgo. Edición en Castellano, Barcelona: Ediciones Paidós Ibérica, S.A., p. 304. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco, Brisa Violeta, and Jorge Tadeo Vargas. 2016. No en nuestro patio trasero: Experiencias comunitarias contra la industria del cemento. LIDECS, AC, Estado de México: Astillero Ediciones, ISBN-13: 978-1539669876. Available online: https://www.no-burn.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/libro-Cementeras-4.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Castillo, Mayarí. 2024. Experiencias tóxicas y género en la conflictividad socioambiental: Un análisis del liderazgo femenino para el caso chileno. Journal of Political Ecology 31: 376–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cámara de Diputados. 2025. Proposición con punto de acuerdo con el fin de exhortar, respetuosamente al Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología en coordinación con la Comisión Nacional del Agua, impulsen proyectos de incidencia socioambiental ante la grave contaminación del Río Tula, en la Zona del Valle del Mezquital del Estado de Hidalgo. Ciudad del México. Available online: https://infosen.senado.gob.mx/sgsp/gaceta/64/3/2021-05-31-1/assets/documentos/94-PA_Morena_Dip_Solis_Barrera_Rio_Tula.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- CENACEM. 2025. Cámara Nacional del Cemento. Available online: https://canacem.org.mx/ (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Chahim, Dean. 2022. Gobernar más allá de la capacidad: Ingeniería, banalidad y la calibración del desastre en la Ciudad de México. Desacatos 69: 172–97. Available online: https://desacatos.ciesas.edu.mx/index.php/Desacatos/article/view/2531/1645 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Cifuentes, Enrique, Blumenthal Ursula, Ruiz-Palacio Guillermo, Bennett Stephen, and Peasey Anne. 1994. Escenario epidemiológico del uso agrícola del agua residual: El valle del mezquital, México. Salud Publica Mex. Available online: https://www.saludpublica.mx/index.php/spm/article/view/5724 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- CONAPO. 2020. Índice de Marginación a nivel estatal, 2010, 2015. Consejo Nacional de Población. Available online: https://indicemx.github.io/IMx_Mapa/IME_2010-2020.html#section-2 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Contreras, Jesse, Meza Rafael, Siebeb Chistiana, Rodríguez-Dozal Sandra, López-Vidal Yolanda, Gonzalo Castillo-Roja, Rosa I. Amieva, Sandra G. Solano-Gálvez, Marisa Mazari-Hiriart, Miguel A. Silva-Magaña, and et al. 2017. Health risks from exposure to untreated wastewater used for irrigation in the Mezquital Valley, Mexico: A 25-year update. Water Research 123: 834–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, Jesse, Rob Trangucci, Eunice Felix-Arellano, Sandra Rodríguez-Dozal, Christina Siebe, Horacio Riojas-Rodríguez, Rafael Meza, Jon Zelne, and Joseph N. S. Eisenberg. 2020. Modeling Spatial Risk of Diarrheal Disease Associated with Household Proximity to Untreated Wastewater Used for Irrigation in the Mezquital Valley, Mexico. Environmental Health Perspectives 128: 77002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, Gregory. 2011. Cement Industry Characteristics. Investment, Carbon Pricing and Leakage: A Cement Sector Perspective. Climate Strategies. pp. 6–20. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep15960.4 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Delgado Ramos, Gian Carlos. 2015. Complejidad e interdisciplina en las nuevas perspectivas socioecológicas: La ecología política del metabolismo urbano (Ensayo) o Complexity and interdisciplinarity in novel socioecological perspectives: Political ecology of urban metabolism. Letras Verdes. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Socioambientales Flacso—Ecuador 17: 108–30. [Google Scholar]

- Domingo, José, Marquès Montse, Nadal Mart, and Schuhmacher Marta. 2020. Health risks for the population living near petrochemical industrial complexes. 1. Cancer risks: A review of the scientific literature. Environmental Research 186: 109495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, José Andrés, and Aledo Antonio. 2001. Teoría para una Sociología Ambiental. Sociología ambiental. Grupo Editorial Universitario. Available online: https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/nd/ark:/59851/bmc0983682 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Downs, Timothy, Cifuentes-Garcíía Enrique, and Irwin Mel Suffet. 1999. Risk Screening for Exposure to Groundwater Pollution in a Wastewater Irrigation District of the Mexico City Region. Environmental Health Perspectives 107: 553–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EjAtlas. 2025. Global Atlas of Environmental Justice, Huichapan. Available online: https://ejatlas.org/conflict/huichapan-waste-incineration-in-cemex-factory-hidalgo (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Folchi, Mauricio. 2019. Environmentalism of the Poor: Environmental Conflicts and Environmental Justice. In Social-Ecological Systems of Latin America: Complexities and Challenges. Edited by Delgado Luisa and Marín Victor. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonchingong Che, Charles, and Henry Ngenyam Bang. 2024. Towards a “Social Justice Ecosystem Framework” for Enhancing Livelihoods and Sustainability in Pastoralist Communities. Societies 14: 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, David. 2005. El “nuevo” imperialismo: Acumulación por desposesión. Buenos Aires: CLACSO, Socialist Register. Available online: https://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/clacso/se/20130702120830/harvey.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Herrera, Juan Antonio. 2019. Conflictos territoriales en el estado de Hidalgo: El Movimiento Indígena Santiago de Anaya se Vive y se Defiende…. In Espinosa and Meza, Reconfiguraciones socioterritoriales: Entre el despojo capitalista y las resistencias comunitarias. Puebla: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, ISBN UAM: 978-607-28-1756-2, ISBN BUAP: 978-607-525-659-7. Available online: https://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/Mexico/dcsh-uam-x/20201118025655/Reconfiguraciones.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Holcim, Línea de Tiempo. 2025. Available online: https://www.holcim.com.mx/linea-de-tiempo (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Hoornweg, Daniel, and Kevin Pope. 2008. Population predictions for the world’s largest cities in the 21st century. Environment and Urbanization 29: 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Matt. 2018. Resource geography II: What makes resources political? Progress in Human Geography 43: 553–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Matt. 2022. Resource geography III: Rentier natures and the renewal of class struggle. Progress in Human Geography 46: 1095–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juskus, Ryan. 2023. Sacrifice Zones: A Genealogy and Analysis of an Environmental Justice Concept. Environmental Humanities 15: 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanazawa, Mark. 2023. Research Methods for Environmental Studies: A Social Science Approach. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-68017-3. [Google Scholar]

- Labastida, Julio. 1976. Tula: Una experiencia proletaria. Cuadernos Políticos 10: 65–79. Available online: http://www.cuadernospoliticos.unam.mx/cuadernos/num05.html (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- La Jornada. 2024. Reportan explosión al interior de refinería de Pemex en Tula. Available online: https://www.jornada.com.mx/noticia/2024/02/12/estados/reportan-explosion-al-interior-de-la-refineria-de-pemex-en-tula-885 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- La Jornada. 2025. Infiernos La Región Más Contaminada, Castiga 140 empresas el Valle del Mezquital. Available online: https://www.jornada.com.mx/2014/01/21/politica/003n1pol (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- La Jornada del Campo. 2025. Infiernos Ambientales. Las cloacas de la civilización. Suplemento informativo de La Jornada. Available online: https://www.jornada.com.mx/2020/11/21/delcampo/delcampo158.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Leduc, Paul. 1977. Etnocidio: Notas Sobre El Mezquital. [Film]. México: National Film Board of Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Leff, Enrique. 2023. Ecología Política. De la deconstrucción del capital a la territorialización de la vida. Ciudad de México: Siglo XXI editores, p. 483. [Google Scholar]

- Merlinsky, Gabriela. 2013. La espiral del conflicto. Una propuesta metodológica para realizar estudios de caso en el análisis de conflictos ambientales. In Cartografías del conflicto ambiental en Argentina. Edited by CLACSO. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires: CICCUS, pp. 61–90. Available online: https://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/clacso/se/20140228033437/Cartografias.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- OCMAL. 2024. Conflictos Mineros en América Latin. México: Observatorio de Conflictos Mineros de América Latina. Available online: https://mapa.conflictosmineros.net/ocmal_db-v2/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Ortiz-Espejel, Benjamín. 2020. Región Atitalaquia-Tula-Apaxco: Hacia un modelo de restauración ecológica. In Diálogos Ambientales. Ciudad de México: Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, pp. 79–82, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Quezada Ramírez, Noemí. 2009. El Valle de Mezquital en el siglo XVI. Anales de Antropología 13: 185–97. Available online: https://www.revistas.unam.mx/index.php/antropologia/article/view/325 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Ramírez, C., and J. A. Cañón. 2022. Vigencia del concepto centro-periferia para comprender nuestra realidad líquida. Revista Mexicana de Sociología 84: 323–60. [Google Scholar]

- Reygadas, Rafael. 2016. Zimapán, Hidalgo: Resistencia, memoria colectiva y nuevas generaciones. In Decisio, saberes para la acción en educación de adultos. Centro de Cooperación Regional para la Educación de Adultos en América Latina y el Caribe, Ciudad deiuda dpp. 43–44. Available online: https://www.revistas.unam.mx/index.php/antropologia/article/view/325/307 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Saccucci, Ericka. 2024. La construcción de sentidos sobre un territorio de sacrificio en un conflicto socioambiental por la producción de bioetanol en la ciudad de Córdoba, Argentina. Journal of Political Ecology 31: 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidel, Arnim, Daniela Del Bene, Juan Liu, S. Grettel Navas, Sara Mingorría, Federico Demaria, Sofía Avila, Brototi Roy, Irmak Ertör, Leah Temper, and et al. 2020. Environmental conflicts and defenders: A global overview. Global Environmental Change 63: 102104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEDESOL. 2012. Impacto del Megaproyecto de la Refinería de PEMEX en Tula Hidalgo: Incidencia de Actores Institucionales y Sociales en el Desarrollo Regional. Ciudad de México: Secretaría de Desarrollo Social, Instituto Nacional de Desarrollo Social, Red Unida de Organizaciones de la Sociedad Civil de Hidalgo A. C., Centro de Derechos Humanos y Sociales A. C., Centro de Desarrollo Humano A, p. 81. [Google Scholar]

- SEMARNAT. 2020. Manifestación de Impacto Ambiental. Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales modalidad regional proyecto CC Tula II fase I. Available online: https://apps1.semarnat.gob.mx:8443/dgiraDocs/documentos/hgo/estudios/2020/13HI2020E0061.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- SENER. 2025. Sistema de Información Energética Petróleos Mexicanos. Available online: Elaboración de productos petrolíferos por refinería. Available online: https://sie.energia.gob.mx/bdiController.do?action=cuadroandcvecua=PMXD1C02 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Siemens, Jan, Gerd Huschek, Christina Siebe, and Martin Kaupenjohann. 2008. Concentrations and mobility of human pharmaceuticals in the world’s largest wastewater irrigation system, Mexico City Mezquital Valley. Water Research 42: 2124–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, Victor Manzur. 2024. Infiernos Ambientales de México, Opinión en La Jornada. Available online: https://www.jornada.com.mx/2019/07/30/opinion/016a1pol (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Vargas, Mónica. 2022. Empresas transnacionales y libre comercio en México. Caravana sobre los impactos socioambientales, TNI, México. Available online: https://www.tni.org/files/publication-downloads/informe_caravana_toxitourmexico_cast.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Vásquez, Belem, and Salvador Corrales. 2017. Industria del cemento en México: Análisis de sus determinantes. Revista Problemas del Desarrollo 48: 113–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Rodríguez, Gabriela Alejandra. 2023. La acción comunitaria contra la “basurización” de Hidalgo, México. Letras Verdes Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Socioambientales, p. 34. Available online: https://revistas.flacsoandes.edu.ec/letrasverdes/article/download/5960/4591/27645 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Vélez-Torres, Irene, Moreno-Moreno Carolina, and Hurtado Chaves Diana Marcela. 2024. Empobrecimiento e intoxicación de cuerpos-territorios en zonas cultivadas con coca y marihuana en Colombia. Journal of Political Ecology 31: 351–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morales, J.G.; Gallegos, B.V.C.; Reyes, R.H.; Alanis, J.C.; Vargas, E.C. Political Ecology as an Analytical Tool in the Mezquital Valley, Mexico: A Permanent Struggle. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 509. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090509

Morales JG, Gallegos BVC, Reyes RH, Alanis JC, Vargas EC. Political Ecology as an Analytical Tool in the Mezquital Valley, Mexico: A Permanent Struggle. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(9):509. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090509

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorales, Jesús Guerrero, Brisa Violeta Carrasco Gallegos, Raquel Hinojosa Reyes, Juan Campos Alanis, and Edel Cadena Vargas. 2025. "Political Ecology as an Analytical Tool in the Mezquital Valley, Mexico: A Permanent Struggle" Social Sciences 14, no. 9: 509. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090509

APA StyleMorales, J. G., Gallegos, B. V. C., Reyes, R. H., Alanis, J. C., & Vargas, E. C. (2025). Political Ecology as an Analytical Tool in the Mezquital Valley, Mexico: A Permanent Struggle. Social Sciences, 14(9), 509. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090509