Abstract

This study focuses on the current service/care difficulties and challenges that social institutions in Hungary are facing during their daily operations; how they can react to them utilizing their internal resources, mechanisms, and capacities; and what concrete, tangible needs and demands are emerging in terms of methodological professional support, potential forms, interventions, and direction for professional development. A total of 24 general and 55 specific service and operational problems were identified and assessed in eight different service areas (family and child welfare services, family and child welfare centers, respite care for children, care for the homeless, addiction intervention, care for people with disabilities, care for psychiatric patients, specialized care for the elderly, and basic services for the elderly). The empirical base of the study uses a database of 201 online questionnaires completed by a professional target group working for social service providers in two counties (Győr-Moson-Sopron and Veszprém), representing 166 social service providers. The questionnaires were completed between November and December of 2022. The findings will be used to develop a professional support and development problem map. Social institutions face complex and serious service/care difficulties and challenges in their daily operations. Three distinctive basic problems clearly stand out in both severity and significance from the complex set of factors assessed. The biggest problem in the social care system is clearly the complex challenge of low wages, followed by the administrative burdens in the ranking of operational difficulties, and the third key factor was the psycho-mental workload of staff.

1. Introduction

The aim of this study is to present the current service/care difficulties and challenges (problems) that social services in Hungary face in their daily operations and to explore how these services can react to these problems, utilizing their internal resources, mechanisms, and capacities (solutions), as well as to identify what concrete, tangible needs and demands are formulated for methodological professional support, including possible directions, forms, and interventions for professional development (forms of support).

Identifying and systematizing the general (for all actors) and specific (by type of service/care, by target group) elements of the operational difficulties and problems (understood in relation to the service sites of social services) proved to be a key professional challenge. A total of 24 general problems were identified and assessed along three dimensions (resource-based, financial, and technical), along with 55 specific problems in the eight different service areas (family and child welfare services, family and child welfare centers, respite care for children, care for the homeless, addiction intervention, care for people with disabilities, care for psychiatric patients, specialized care for the elderly, and basic services for the elderly). The study assesses the probability of occurrence and the degree of exposure to the general and specific problems affecting the day-to-day functioning of social services (how significant the problem is).

The empirical questions of the research are structured along the threefold logic described above (current problems/difficulties, possible solutions, external professional support needs), and based on this, a total of five research questions were formulated.

- What are the basic problems that hamper the daily functioning of social services the most, and what is the order of importance of the problem system? What are the main challenges and difficulties identified by the professionals concerned?

- What are the most significant specific target area and target group problems within each service area?

- In the cases where the phenomena are considered “major” or “very big problem”, what are the concrete solutions, mechanisms, and practices utilized by the services concerned to alleviate and address these phenomena?

- What external help would be needed to address the above problems, and what changes would be necessary to alleviate or eliminate them?

- What are the most important external professional support solutions that social services need right now?

The study will review the available literature on the assessment of general and specific operational problems and difficulties of social services and their results, the research methodology used (questionnaire, sample, etc.), a detailed presentation of the most important quantifiable empirical results (incidence, importance, ranking of problems, support needs), and the opinions expressed in the form of open questions (own internal problem management solutions), as well as the summary of the basic outlines of a professional support and development problem map and the outline of institutional and operational development proposals based on these results. The national and international studies forming the foundations of this study clearly show that the problem system is mostly national in scope and characterized by a complex and systematic nature (Netten and Davies 1990; Webb 2003).

Hungary inherited a comprehensive welfare system from its socialist past that aligned with European social models, particularly when joining the European Union (EU) in 2004. This included centralized social insurance, social assistance, and labor market policies aimed at social inclusion and poverty alleviation, reflecting typical EU welfare system goals (Hoffman 2017). Municipalities play a significant role in the field of social care services. The basic social services are primarily provided by local governments, similarly to other decentralized European models, with a focus on maintaining grassroots service provision, which is common in many EU countries (Hoffman and Szatmári 2020). While Hungarian local governments are responsible for providing basic services, the county and the state provide specialized social services (residential and specialized care services, such as nursing homes). The Hungarian social care system therefore consists of decentralized and centralized services, supplemented by church and non-profit service providers. In this study, the examination of the Hungarian social care system is therefore presented through the county level.

The social sector in Hungary has been characterized by a dynamic development between 1993 and 2018. The most significant increase was in the basic social services, as the legislation in this area links the provision of basic social services at the municipal level (Czibere and Mester 2020). This dynamic development has, however, created problems in the current social care system that have not been addressed despite previous problem statements (Győri 2012; Darvas et al. 2013). In most EU countries (e.g., Austria, Germany, France, and Belgium), on the other hand, state social policy is complemented and often taken over by the family and the local community, in line with the principle of subsidiarity, which in many cases generates completely different problems (e.g., women’s participation in the labor market or fertility) (Bettio and Plantenga 2004; Neyer 2021). Another difference is that while the Hungarian social system addresses the care needs by differentiating and expanding free services, in EU countries (e.g., Germany, Italy, France, Sweden, and the Netherlands), the provision of cash benefits is more widespread, with service users purchasing the necessary care themselves (Timonen et al. 2006; Roit and Bihan 2010; Roit and Gori 2019). While this form of benefit provides greater freedom for service users, it also generates problems such as the commodification of informal care or the presence of foreign workers who may not be able to communicate with service users (Ungerson 2004; Carey et al. 2019).

Despite these differences, three major common concerns emerge in the field of personal care services in Hungary and EU countries (mainly in Eastern Europe and Nordic countries, as well as Greece and Spain): funding (and the impact of socio-political changes on the funding of services), the human resources crisis, and the accessibility and quality of services, and in some cases their integration (Ferge 2017; Meleg 2020, 2021; Kozma 2007, 2020; Bugarszki 2014; Nyitrai 2021; Csoba et al. 2022; Lamura et al. 2008; Courtin et al. 2014; Leichsenring 2004; Wollmann 2018; Da Roit et al. 2013; Llena-Nozal et al. 2022).

1. From a financial point of view, it would be important to regulate the wages of professionals working in the Hungarian social sector, to regulate public funding, to ensure predictable developmental funds for infrastructure investments as well, and to end funding discrimination based on the maintainer of the social services (Ferge 2017; Czibere and Mester 2020; Meleg 2021; Nyitrai 2021). However, the funding crisis in social services is not unique to Hungary; the impact of political and economic changes in the social sector is felt across the EU. Recent trends show that the austerity measures resulted in most EU countries returning to public/local government to finance services (Wollmann 2018; Llena-Nozal et al. 2022).

2. The human resource crisis is not unique to the Hungarian care system. One of the most recent evaluation studies on the Hungarian social careers model concludes that “the high turnover, the growing shortage of professionals, the steady decline in the number of young people enrolling in higher social education, and the burnout of professionals in the field call for systemic changes in the development of the sector. Amongst the many priority areas to development within the sector, human resource development, enhancing the prestige of the social profession, motivating professionals, recognizing quality work, and developing a unified career path system have become a topical issue.” (Csoba et al. 2022; Meleg 2021; Nyitrai 2021). EU countries’ social services providing personal care face similar challenges to the Hungarian care system. Due to the shortage of professionals, most care systems either employ foreign caregivers or a “cash for care” system. However, these solutions raise numerous problems, such as language barriers, along with other long-term problems like the deterioration in the quality of service and vulnerability of both the service user, family members, and the workers, as well as the problem of a commodified form of informal care. Marketization, lack of managerial skills, and the decline in the number of caregivers are also problems for most EU countries (Da Roit et al. 2013; Leichsenring 2004; Villalba et al. 2013; Federation of European Social Employers 2019, 2022).

3. The Hungarian service structure and institutional network in many aspects can be deemed inadequate, as in many cases, it only provides a nominal coverage of service areas, and it cannot meet the actual needs due to lack of capacity (Ferge 2017). This is due to the fact that the service structure is fragmented and inefficient; pilot schemes of model experiments have been contingent for several years (Ferge 2017; Czibere and Mester 2020; Meleg 2021; Nyitrai 2021). There are significant differences in access to services across EU countries. The affordability of services varies from country to country, as do the access and patterns of formal and informal care. In many places, informal caregivers do not receive any support, and therefore, access to these types of services is not available to the poorer classes (Lamura et al. 2008; Courtin et al. 2014; Mantu and Minderhoud 2023; European Commission 2024).

Two important problem areas appear in the Hungarian system that are less mentioned in the international literature. One of them is the inadequacy of regulations: legislative unpredictability characterizes the Hungarian legislation regulating social services, which is becoming increasingly difficult to understand due to constant changes, and, due to its size and structure, it becomes increasingly difficult to manage for practitioners (Ferge 2017; Czibere and Mester 2020; Meleg 2021); the second problem area is the fact that the administrative obligations of the Hungarian social sector have increased in recent years to the detriment of the professional work (Meleg 2021).

In summary, while Hungary’s social services share foundational elements with other EU member states—especially in its formal structures and historical legacies—recent policy shifts towards centralization, austerity, and conservative family roles mark a significant divergence from mainstream European social models. These changes have implications for social integration, inequality, and the overall effectiveness of social protection compared to other EU nations.

Despite these undeniably serious problems, as a responsible professional, one cannot ignore the fact that the problems listed are all external, pointing to funding, service structure, the human resources crisis, and changes in the legislative requirements—factors which, given the sector’s weak self-advocacy/advocacy capacity (Meleg 2021), are inherently beyond the control of the individual social services.

“A critical attitude could be a shift away from professional self-pity” (Varsányi 2006). Varsányi primarily draws attention to the fact that the operational problems faced by social services have an internal basis as well. Her study highlights the lack of cooperation among professionals, the dominance of case management, the degrading role of the donor, and the professional role of accepting problems and feeling sorry for themselves. Lamura agrees with Varsányi that better cooperation would also be key for the proper functioning of the European social services (Lamura et al. 2008). “According to Márta Erdős B., social work is a weakly monopolized field, and the representatives of the profession are not in a position to defend their own field. This is illustrated by the emergence of new professions that carve out a part of the social work field (e.g., mental health workers, community organizers).” (Berger 2019, p. 107). The weak monopoly of social work also has an impact on the functioning of services. The problems in the sector listed above may also stem from this fact.

2. Materials and Methods

The empirical base of the study uses a database of online questionnaires completed by a professional target group working for social service providers (377 institutional units in total) in two counties (Győr-Moson-Sopron and Veszprém). The questionnaires were completed between November and December of 2022, which resulted in 201 personal questionnaires for analysis. The sample consists of 201 analyzable personal questionnaires, representing 166 social service places in the two selected counties. The sampling frame of the survey was the service providers of social and/or child welfare services in the two counties selected for the survey (family and child welfare services, family and child welfare centers, respite care for children, care for the homeless, addiction intervention, care for people with disabilities, care for psychiatric patients, specialized care for the elderly, and basic services for the elderly). The decision to conduct the survey at the county level (specifically the aforementioned two Hungarian counties) is based on the content and regional profile of the funding project on which the research is based. The research was funded by Hungarian Maltese Charity Service Association (Grant number: TSZR2021-1481—Title: Elaboration of a vocational development and support system in Győr-Moson-Sopron and Veszprém counties). Given that the structure and operation of the social service system are very similar in all counties in Hungary, the results obtained can also be interpreted nationally.

The structure of the questionnaire was adapted to the list of services. The questionnaire was divided into four question groups. The first set of questions was used to identify the services provided by the establishments and to collect their basic statistics. The second set of questions dealt with the perception and assessment of general problems (applicable to all sites/establishments) and the ideas to solve these problems. The third set of questions was used to identify and assess the specific problems related to the services provided by the individual establishments. The last set of questions in the questionnaire dealt with the evaluation of the planned professional support solutions. The list of problems raised in the second and third sets of questions and the professional support solutions outlined in the fourth set of questions contained the items listed at the professional roundtables preceding the data collection as closed questions, which were followed by additional, open-ended questions, where respondents could name additional elements.

Regarding the sample of service providers, it can be concluded that most of the providers are municipally run, with more than half of the respondents belonging to this category (51.2%). A quarter of the remaining providers are non-profit (25.9%), while the remaining quarters of respondents are either church-run (12.7%) or state-run (10.2%) in the two counties. In terms of size, small establishments with 0–5 employees dominate, accounting for more than one-third (34.8%) of all service establishments. The average number of professional staff per establishment is 13, which is supplemented by an average of 4 other non-professional staff. Further details on the sample are available in Appendix A.

In terms of service areas, the data collection process included information on several multifunctional facilities; therefore, the sum of the values here is higher than the number of service providers. Among the service areas, the most notable were the basic and specialized care for the elderly and care for people with disabilities, as nearly 60% (57.4%) of the service providers identified the elderly as their main target group, while almost 40% (38–37.3%) of the service providers identified children and families as the main target group. In contrast, specialized services for addicts, the homeless, and psychiatric patients are significantly less frequently mentioned as the services’ target groups.

3. Results

The results of the expert questionnaire survey are summarized by the problem type. In addition to a classification of the significance and severity of the problems, the mechanisms for solving them are also presented. The results are detailed in two parts. The scale and nature of the general and specific problems are presented in two separate steps.

3.1. General Problems and Their Possible Solutions

The most important point of the empirical survey is to prioritize the overall operational problems and challenges and to clarify which factors can be considered as the most serious and pressing difficulties of the social care system at the moment. The ranking of the general problem scores on a four-point scale (Table 1) clearly highlights the main challenges: low wages, increasing administrative tasks, and the psycho-mental workload of the professionals. Other elements of the ranking include overwork, lack of certain forms of care, difficulty in filling jobs, lack of specialists, burnout, lack of a proper career path, and lack of supervision.

Table 1.

Rankings of the general problems based on average score (minimum 1 point = no problem at all–maximum 4 points = major problem).

The overall problem index is 2.6, which is only marginally different from the four-point rating scale average (2.5). If a score of four were to be considered as a full-scale operational anomaly (i.e., all problem areas would have major problems), the above score would suggest that services are currently at a 65% problem level. As expected, the financial sub-index is the highest of the three problem areas (with an average of approximately 3 points), which represents a problem level of 75 percentage points. When comparing the type of services, the overall problem index is highest among church-run services (2.8 points). For resource-related problems, the scores of the church-run and centrally run services stand out (2.9 points). The financial problem index is high for all four types of institutions (2.8–3.0 points), proving to be a general system challenge. For the aggregate overall problem index and the three sub-area problem indices, there is a clear correlation between the size of the institution (in terms of the number of professionals) and the severity of the problems. The average values are highest for larger social institutions with more than 20 people. The problem index averages increase with size and can be clearly observed by most sub-indicators.

When asked about the general problems, respondents were also given the opportunity to identify individual problems (problems specific to their own service that were not mentioned above). One relevant and often mentioned individual problem identified from the responses is a lack of psychologists, psychiatrists, and psychoeducation or the difficulty to access these services when they are required. Regardless of the area or type of service, psychological counselling is difficult to access or absent from social services.

The range of autonomous internal organizational solutions to the problems examined is very complex. Most of the answers to the major resource problems involve measures such as overtime, substitution, mutual aid within teams, flexible work sharing, reorganization within the institution, or mergers. Several services are trying to attract university trainees who show an interest in the field during their training and/or to persuade retired colleagues to stay on or possibly be called back to help with certain tasks. Several services reported using case conferences, supervision, or institutional psychologists as their solution to the human resources problems they face. Often, they have some kind of mentoring scheme: they train unskilled workers, organize open days for recruitment, or advertise in local media. The “solution” to financial problems relies primarily on grant funding, similarly to how they rely on these grants to solve human resource issues. Additionally, the organizations organize/participate in fundraising, regrouping, and merging to reduce the problems. The fund managers often use compensation for the services they run, if they have the possibility to do so (surplus funds, transfers, etc.). For professional problems, most services responded with solutions that met the expectations. They use well-established forums in the social care system: case conferences, supervision, consultation with the professional manager, psychologist, methodological institute, professional contacts, training, professional forums, professional workshops, and adoption of good practices.

3.2. Specific Problems and Their Possible Solutions

Specific problems are factors specific to the service area, which primarily concern the specific service type and are not included in the general difficulties/challenges. Specific problems were defined in the questionnaire by the area of care and the target group.

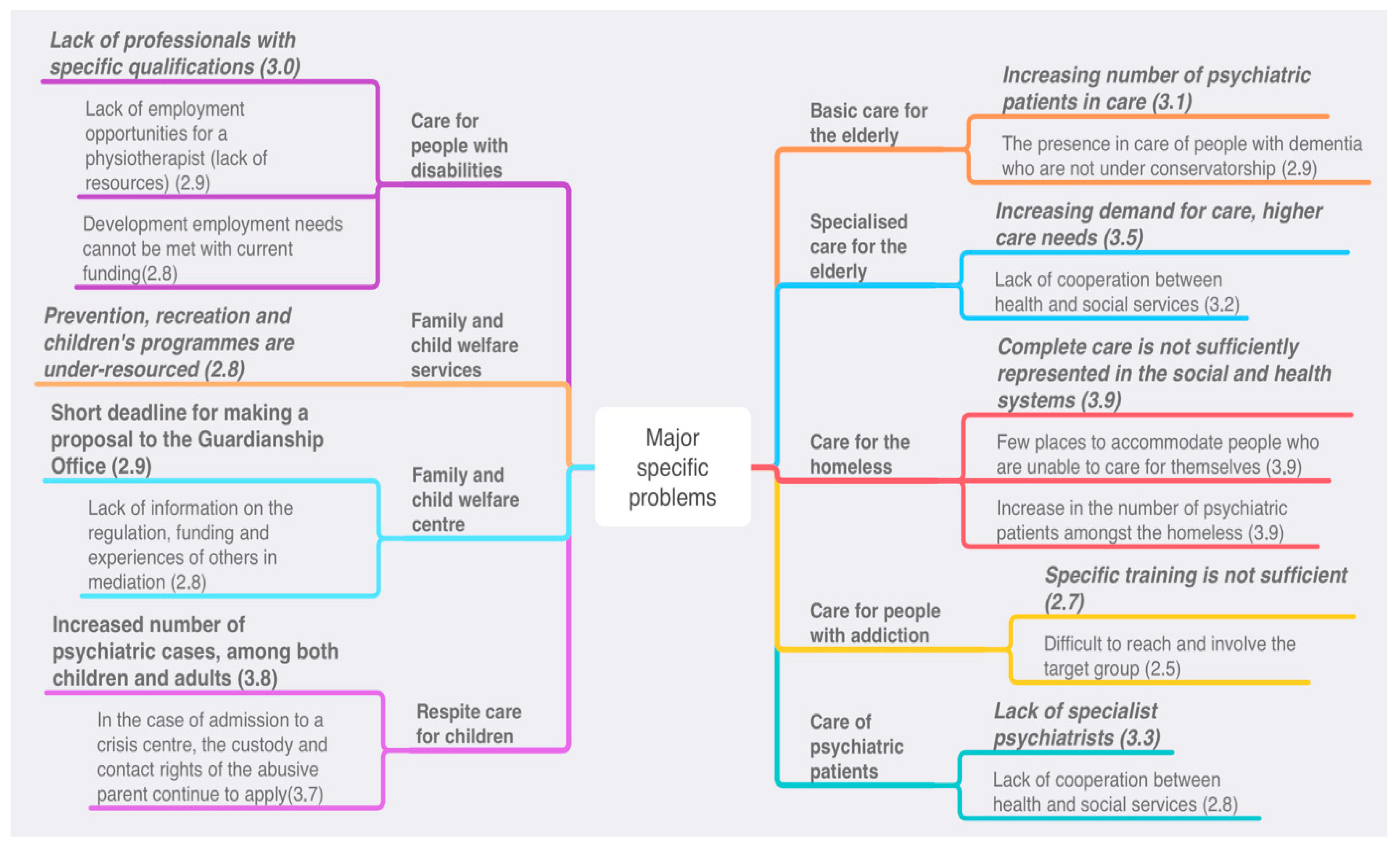

Some of the responses from professionals reiterate the well-known problems (e.g., increasing care needs in specialized care for the elderly, increasing need for care, shortage of social workers in nurseries and schools, shortage of psychiatrists, etc.), and there were also responses that indicated classic, long-standing, and persistent problems (e.g., signposting system members not familiar with primary child welfare services). In several areas (services for the elderly, respite care for children, services for the homeless), this included the appearance of a high proportion of psychiatric patients (often undiagnosed or under treatment but not present in psychiatric care).

Based on the questionnaire responses, the area of social services for the homeless is the most problematic (Table 2). The staff scored all the specific problems listed over 3.5, highlighting the lack of or insufficient number of complete care for the homeless. The areas with the least problems were addiction services, where none of the problems scored over 3, and the family and child welfare services, where only two specific problems were identified, and both scored below 3. Details of the results are shown in Appendix B.

Table 2.

Rankings of specific problems in the field of care for the homeless based on average scores (minimum 1 point = no problem at all–maximum 4 points = major problem).

Similarly, as in the case of the general problems, there were several respondents who did not see their own solution to the specific problems. The justification was that professionalism is always subordinate to financial solutions. Co-professions often do not see social care professions with a lower social prestige as partners (e.g., psychiatrists and social workers), so cooperation problems are difficult to solve in certain areas. The third reason is simply the lack of services, which the professionals in the field cannot cope with, as the creation of services is not up to them but to the managers, who often decide on financial grounds rather than on professional ones.

Internal solutions often include seeking cooperation with other areas, professionals, institutions, and services, even by mobilizing one’s own personal social capital. If there is another form of service in the area that is suitable for the service user, they will continue to care for the client. This can be seen as a form of profile cleansing in the social services sector. In the case of very specific problems (e.g., in the field of addiction services, it is difficult to engage the beneficiaries in the service), special tools are used. This can include, for example, influencing and sensitizing the population and public opinion towards the problem and the people living with the problem.

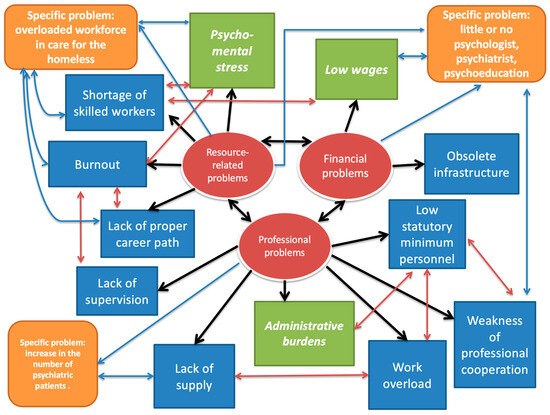

3.3. Problem Map

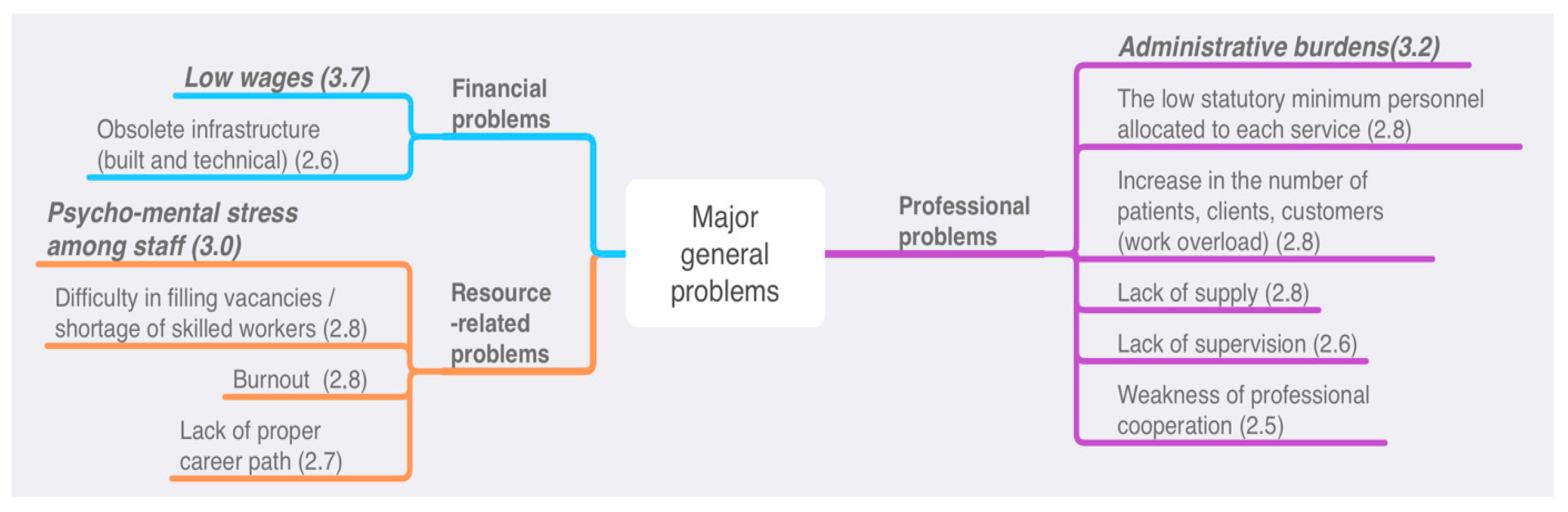

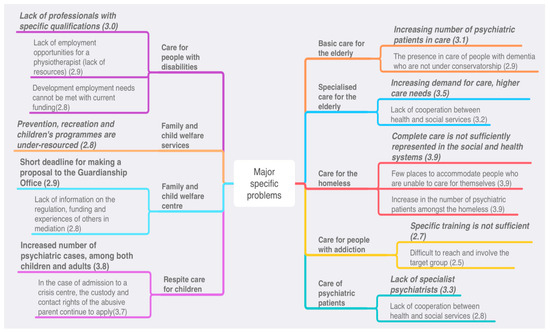

Using the empirical data presented in the previous chapter, the actual problem structures are divided and summarized in three professional support and development problem maps. Of the almost 80 general (common to all social institutions and service areas) and specific (differentiated by type of service) operational challenges we examined, 12 general (Figure 1) and 19 specific (Figure 2) problems stand out due to the severity of the current situation; this was confirmed by the majority of the service providers interviewed.

Figure 1.

Major general problems.

Figure 2.

Major specific problems.

Two of the three financial problems and four of the nine resource-related problems were included in the problem map, while six of the twelve professional problems are predicted to be the major challenges and difficulties for the social service providers surveyed. In the case of specific problem areas, one-third of the factors assessed can be considered of major importance, as in the case of these two counties, these problems create above-average disruptions and difficulties in the day-to-day operations of the institutions.

The three main problems indicated by the problem map are low wages, administrative burdens, and psychological and mental stress among staff. Since social work is undervalued in Hungary, this is also reflected in the financial resources spent on the sector. Social workers working in services maintained by the state or local governments are paid according to the public employee salary scale. A graduate social worker starting their career receives a net salary of around 280 thousand HUF/month, which is equivalent to approximately 700 euros. This low salary does not motivate young people to find a job within the social sector, which is why there is a shortage of professionals.

At the same time, those already working in the sector are given more tasks, which further increases their psychological and mental burden. Mental stress is further exacerbated by the increasing number of service users, many of whom have more serious problems and, in some cases, even lack material conditions (for example, in the case of kindergarten and school social workers, the infrastructure of schools is not suitable for carrying out their aid activities). Innumerable services lack supervision, which alleviates the psychological burden.

The large administrative burdens also drain energy from the aiding process. The family helper carrying out the social aid process must maintain contact with the service user three times a month and then record all of this in the case diary or on the designated online platform. A family helper can have up to 25–30 cases concurrently, so the staff often drown in administrative duties, which leads to further lack of motivation, since those who choose social work primarily want to deal with people, not with administrative tasks. The accumulation of problems leads to an increase in the number of social professionals leaving their careers and countries.

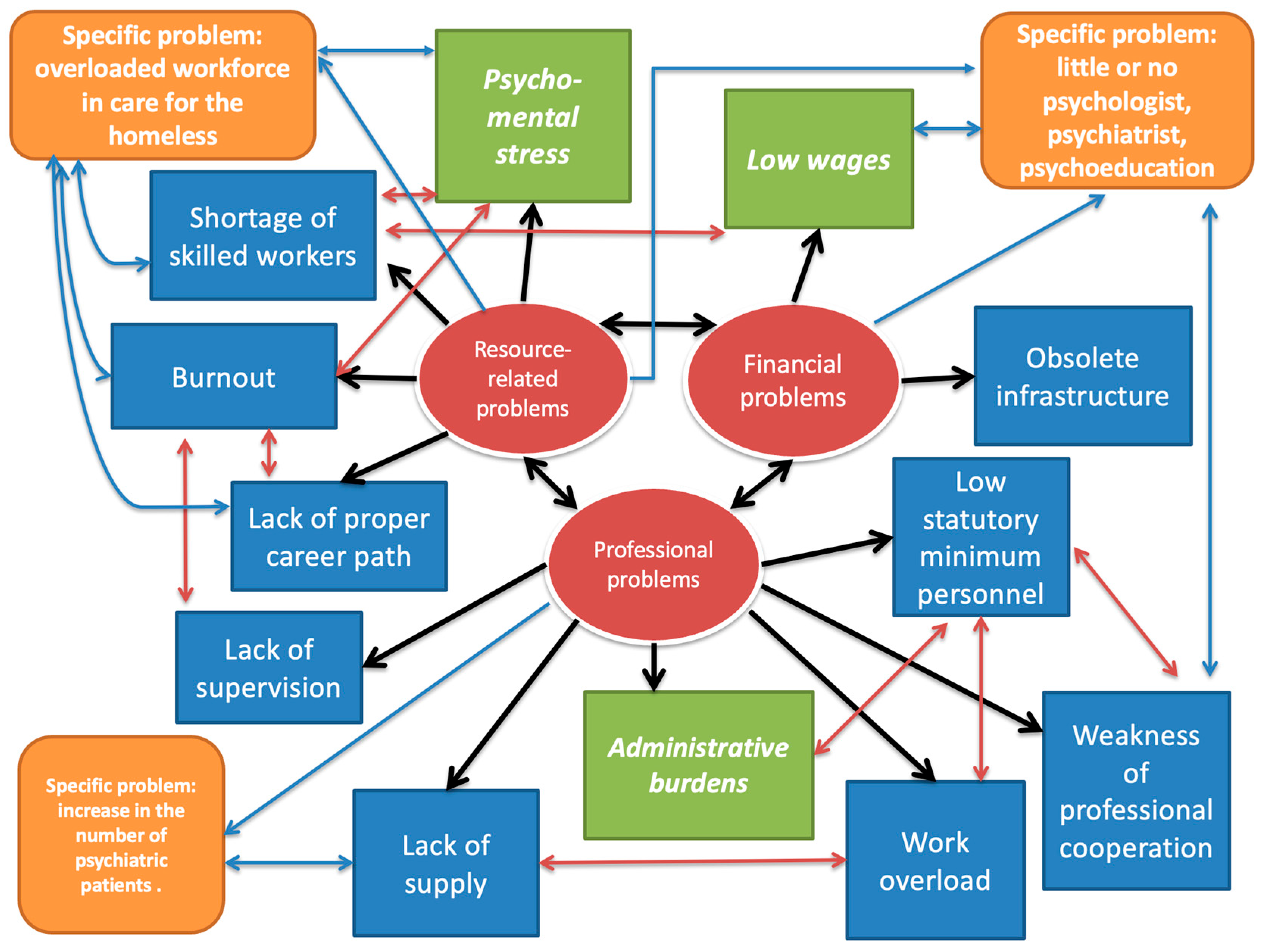

The complex problem map summarizing the study (Figure 3) shows how the three main problem areas, including general and specific problems, are interlinked. The main message of the figure is that everything is interconnected. During their careers, a skilled social worker will see a similar pattern and look for the root causes, the factors that cause the problem. If we were to disregard the social causes (e.g., an aging society) that influence the social services users in a number of ways, for example, the number of people using social services, and focus only on the social services system (including, of course, the legislation, the supervisors, and the system of service users itself), the internal triad of the complex problem map (three main problem areas) appears to be the root of the problems. Moving towards the edges of the figure, we see more consequences and symptoms caused by the roots.

Figure 3.

Summary of the complex problem map.

The main message of the figure is that the problems of social services cannot be solved by symptomatic treatment (constant changes in legislation, introduction of new regulatory elements (e.g., protocols), ad hoc wage increases instead of a career model, periodic supervision financed by grants, reduction of professional staff, model programs based on uncertain grants, etc.). The system, in its current state, does not provide security for many of its actors; therefore, a systematic intervention is needed to improve the situation.

4. Discussion

The results confirm that the prominent problems of social services include low wages, the increasing degree of administrative burdens, and the high psycho-mental workload among staff—operational difficulties that continue to challenge Hungarian social institutions. These findings align with prior national and international studies that highlight similar systemic issues in social care, such as funding shortages, human resource crises, and fragmented service structures (Ferge 2017; Meleg 2021; Kozma 2020; Bugarszki 2014). The predominance of low wages proves to be the most severe problem, as it underscores the critical need for financial reforms and the need for a sustainable funding mechanism in the sector, which has been a recurring theme in the national and European social policy discourses (Czibere and Mester 2020; Nyitrai 2021).

The administrative burdens identified reflect a growing trend in Hungarian social services, where legislative unpredictability and increasing bureaucratic demands detract from professional work and service quality (Meleg 2021; Ferge 2017). This further resonates with the broader European context, where administrative complexity often hampers effective service delivery (Lamura et al. 2008). Moreover, the psycho-mental workload points to a human resource crisis characterized by high turnover rates, burnout, and declining professional prestige, which is consistent with earlier evaluations of the Hungarian social care workforce and comparable European challenges (Csoba et al. 2022; Da Roit et al. 2013).

The internal coping mechanisms and the solutions employed by institutions are also highlighted, which is a valuable contribution given that much of the existing literature tends to focus on external systemic problems. This internal perspective echoes Varsányi’s (2006) argument that operational issues also have roots within professional practices, such as insufficient cooperation and a culture of professional self-pity. Enhancing collaboration and professional development within institutions could therefore be a strategic focus for improving the service efficacy.

5. Conclusions

The first research question addressed the basic problems that hamper the daily functioning of social institutions and the main challenges and difficulties identified by the professionals. The empirical results clearly show that the main problem of the social care system is the complex challenge of low wages. Administrative burdens ranked second in the ranking of operational difficulties, and the third key factor was the psycho-mental workload of staff.

The second research question focused on the most significant specific target area and target group problems within each service area. The internal problem-solving responses and solutions of the different service areas are also very diverse in terms of the specific challenges and their difficulties. There were several respondents who did not see their own solutions to specific problems. Internal solutions often include seeking cooperation with other areas, professionals, institutions, and services, even by mobilizing one’s own personal social capital. However, these collaborations are often the result of the professional’s social network.

In cases where the phenomena are considered “major” or “very big problem”, the detailed analysis of concrete solutions, mechanisms, and practices utilized by the institutions has highlighted several important points. Responses to significant resource problems through internal coping mechanisms include overtime, substitution, mutual aid within teams, flexible work sharing, reorganization, or mergers within the institution.

The fourth research question is concerned with the need for external assistance and the concrete ways to address it. The survey showed that the scarcity and shortcomings of internal problem-solving opportunities are related to inadequate external assistance. The examined problems of social services cannot be solved by symptomatic treatment (constant amendment of legislation, continuous incorporation of new regulatory elements (e.g., protocols) into the system, ad hoc wage increases instead of a career model, supervision periodically financed from tender sources, reduction of professional staff, model programs based on uncertain tender sources, etc.). This system, in its current state, does not provide security to many of its actors, so well-considered, systemic intervention is needed to improve the situation.

The fifth research question is centered on the most important external professional support solutions that social institutions need right now. There is a high demand for workshops by services and by sites. This is seen as a potential for better cooperation with associate fields (by getting to know each other’s perspectives). It would be essential to learn as many good practices as possible for all areas so that they can then solve their specific problems using their own resources. All respondents believe that taking advantage of online opportunities is important, especially in accessing support this way. In the context of the preparation of professional programs, methodological recommendations, the verification of operating licenses, and the development and publication of templates, as well as specific guidelines and assistance tailored to the service in question, are expected. They would also be happy to participate in internal professional surveys, but they would like to receive feedback on concrete research results. The FAQs (frequently asked questions) are much anticipated, as people in the same field often face similar problems, though they may have different solutions. There is a strong demand for an internet forum, a quarterly newsletter, information on changes in legislation, or information on training and tender opportunities.

It can be concluded that service professionals often have no other choice regarding the “vicious circle” of lack of funding and human resources and the consequent mental burdens faced by those working in the industry. The internal coping mechanisms cannot be considered as a definitive solution. A key message identified through our research was that the financial decision-maker is the maintainer, over whom the profession has less and less influence. Professionalism and service are often subordinated to finance. There is a complete lack of resources. These problems cannot be addressed. There are local sponsors and grant opportunities, but this is just firefighting, not a solution!

Based on the feedback from respondents, the basic and specialized services for the homeless appear to be the biggest problem areas amongst the individual service areas. The managers and staff of the institutions and service providers surveyed also made concrete proposals for professional development.

The social institutions examined face complex and serious service/care difficulties and challenges in their daily operations, which they are forced to respond to with a variety of internal resources, mechanisms, capacities, and constraints at the given moment, while also expressing concrete and immediate needs for methodological professional support, possible directions, forms, and interventions in professional development. Three basic problems clearly stand out in terms of their severity and importance amongst the factors examined.

The implications of these findings extend beyond Hungary, reflecting universal challenges in social service provision, such as workforce shortages, funding instability, and service fragmentation. The study’s identification of specific needs for methodological and professional support provides a practical roadmap for targeted interventions. For instance, addressing wage disparities, simplifying administrative procedures, and implementing mental health support for staff could significantly improve service quality and sustainability.

Future research should build on this baseline by exploring longitudinal changes in these operational difficulties and evaluating the effectiveness of implemented support measures. Comparative studies across different regions and service types could further elucidate context-specific challenges and best practices. Additionally, investigating the impact of emerging policy reforms and technological innovations on service delivery and staff well-being would be valuable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.C. and K.K.; methodology, P.T.; validation, P.T. and T.Z.B.; formal analysis, Z.C.; investigation, K.K.; resources, P.T. and T.Z.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.C., K.K., P.T. and T.Z.B.; writing—review and editing, P.T. and T.Z.B.; visualization, Z.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Hungarian Maltese Charity Service, grant number TSZR2021-1481—Elaboration of a vocational development and support system in Győr-Moson-Sopron and Veszprém counties. The APC was funded by Széchenyi István University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study. All personal identifiers were removed from the data, ensuring that participants could not be directly identified or linked to their data. This anonymization process met the stringent requirements of the applicable data protection regulations. The study did not involve any potential harm or risks to participants. The analysis of anonymized, public data posed no ethical concerns. This study adheres to the relevant ethical guidelines regarding the use of public and anonymized data. These guidelines acknowledge that research using such data may be exempt from formal ethical review. All data was handled in accordance with the principles of data privacy and confidentiality, ensuring that it could not be used for any purpose other than the intended research.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions (privacy reasons); the data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questionnaire sample characteristics (number of items, frequency (%), median, and mean).

Table A1.

Questionnaire sample characteristics (number of items, frequency (%), median, and mean).

| Characteristic | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional completion | 166 | 82.6% |

| Duplicate (all personal) completion | 35 | 17.4% |

| All responses | 201 | 100.0% |

| County | ||

| Győr-Moson-Sopron County | 79 | 47.6% |

| Veszprém County | 87 | 52.4% |

| Maintainer | ||

| Local government | 85 | 51.2% |

| Nonprofit | 43 | 25.9% |

| Church | 21 | 12.7% |

| Central government/state | 17 | 10.2% |

| Size | ||

| 0–5 number of professionals | 56 | 34.8% |

| 6–10 number of professionals | 38 | 23.6% |

| 11–20 number of professionals | 31 | 19.3% |

| 21–… number of professionals | 36 | 22.4% |

| Operation | Median | Mean |

| Number of professional staff, persons | 10 | 13 |

| Number of other staff, persons | 2 | 4 |

| Number of unfilled professional staff, persons | 1 | 2 |

| Other staff unfilled, persons | 0 | 1 |

| Number of people waiting, waiting list, persons | 8 | 16 |

| Number of cases | 43 | 80 |

| Number of beneficiaries | 60 | 121 |

| Service area | N | Percentage |

| Basic care for the elderly | 48 | 28.9% |

| Specialized care for the elderly | 36 | 21.7% |

| Care for people with disabilities | 37 | 22.3% |

| Family and child welfare center | 20 | 12.0% |

| Care for people with addiction | 19 | 11.4% |

| Care of psychiatric patients | 17 | 10.2% |

| Care for the homeless | 10 | 6.0% |

| Respite care for children | 7 | 4.2% |

| Target group | N | Percentage |

| Elderly | 95 | 57.2% |

| Children | 63 | 38.0% |

| Families | 62 | 37.3% |

| People living with disabilities | 46 | 27.7% |

| Addiction patients | 28 | 16.9% |

| Psychiatric patients | 24 | 14.5% |

| Homeless | 17 | 10.2% |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Ranking specific problems by the field of care based on average scores (minimum 1 point = no problem at all–maximum 4 points = major problem).

Table A2.

Ranking specific problems by the field of care based on average scores (minimum 1 point = no problem at all–maximum 4 points = major problem).

| Specialized Care for the Elderly | Score |

| Increasing demand for care, higher care needs | 3.50 |

| Lack of cooperation between health and social services | 3.17 |

| Infrastructure development, adapted to needs | 3.09 |

| Lack of simple, transparent, concise professional protocols | 2.85 |

| Low staff preparedness | 2.83 |

| Basic care for the elderly | |

| Increasing number of psychiatric patients in care | 3.12 |

| The presence in care of people with dementia who are not under conservatorship | 2.91 |

| Difficulties in catering for people with special needs due to lack of capacity | 2.88 |

| Problems related to the rights of people with moderate to severe dementia and their representation (signature, guardianship, representation) | 2.76 |

| Getting elderly to day care | 2.45 |

| Care for people with disabilities | |

| Lack of professionals with specific qualifications | 3.05 |

| Lack of employment opportunities for a physiotherapist (lack of resources) | 2.89 |

| Development employment needs cannot be met with current funding. | 2.81 |

| The group breakdown required in day care cannot be ensured by the minimum number of professionals required. | 2.39 |

| Difficulty of cooperation with other social and health services | 2.34 |

| Legal inconsistency: in support services, a personal assistant has become a helper, while a driver has become a caregiver. | 2.33 |

| No professional guidelines for documentation of planned care | 2.27 |

| Care for people with addiction | |

| Specific training is not sufficient. | 2.67 |

| Funding and staffing shortages due to parallel presence (e.g., conflict between care for the homeless and addiction care) | 2.58 |

| Difficult to reach and involve the target group | 2.50 |

| Lack of support to expand professional methodology | 2.38 |

| Access to information is not satisfactory. | 2.29 |

| Scarcity of development employment opportunities | 2.08 |

| Lack of teamwork between social workers, psychiatrists, and psychologists | 2.08 |

| Care for the homeless | |

| Complete care is not sufficiently represented in the social and health systems. | 3.92 |

| Few places to accommodate people who are unable to care for themselves | 3.92 |

| Increase in the number of psychiatric patients amongst the homeless | 3.92 |

| Increase in the number of addiction patients amongst the homeless | 3.75 |

| Conflicts in TEVADMIN system (e.g., Day Care Centre for Psychiatric Patients conflicts with the Transitional Accommodation for the Homeless) | 3.67 |

| There are no best practices or protocols to follow concerning health problems caused by withdrawal. | 3.58 |

| Care of psychiatric patients | |

| Lack of specialist psychiatrists | 3.32 |

| Lack of cooperation between health and social services | 2.77 |

| Specific training is not sufficient. | 2.67 |

| Co-occurring care for people with different psychiatric illnesses creates many difficulties. | 2.67 |

| Scarcity of development employment opportunities | 2.64 |

| Addicts, people with neurological disorders, dementia, homeless addicts in the psychiatric system | 2.48 |

| Conflicts in TEVADMIN (e.g., Care for the homeless) | 2.40 |

| Family- and child-welfare services | |

| Prevention, recreation, and children’s programs are under-resourced, even though under legislation are a core task. | 2.81 |

| Difficulty of cooperation with specialized pedagogical services | 2.43 |

| Family and child welfare center | |

| Short deadline for making a proposal to the Guardianship Office | 2.92 |

| Lack of information on the regulation, funding, and experiences of others in mediation | 2.84 |

| Difficulty of cooperation with specialized pedagogical services | 2.63 |

| Lack of information on the regulation of contact monitoring, its funding, and the experiences of others | 2.58 |

| Lack of professional protocol for contact management (e.g., the time of the contact management service differ from the official working hours). | 2.50 |

| Shortage of social workers in nurseries and schools | 2.48 |

| Respite care for children | |

| Increased number of psychiatric cases among both children and adults, for which the type of institution is not prepared | 3.80 |

| In the case of admission to a crisis center, the custody and contact rights of the abusive parent continue to apply. | 3.67 |

| Slow administration by the Guardianship Office | 3.40 |

| In the case of a crisis center, the case management time is short (56 days), and no results can be achieved. | 3.38 |

| Learning support teachers are not compulsory in the respite home for families, though needed. | 3.30 |

| There is no control over the use of the compulsory pocket money and no way to monitor its use. | 3.22 |

| Funding does not cover the transport of service users. | 3.11 |

| Involving children in the interest representative forums is not always feasible. | 3.10 |

| Members of the signal system are not familiar with the primary child welfare and child protection services, so the signal is sent to the wrong place (resulting in conflict situations). | 2.80 |

| Crisis and confidential care is integrated into family transition homes, making it difficult to protect families, and funding is insufficient. | 2.80 |

References

- Berger, Viktor. 2019. A szociális munka társadalmi presztízse: Beszámoló kerekasztal-beszélgetésről [The social prestige of social work: Report on a roundtable discussion]. Szociális Szemle 1–2: 102–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettio, Francesca, and Janneke Plantenga. 2004. Comparing Care Regimes in Europe. Feminist Economics 10: 113–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugarszki, Zsuzsa. 2014. A magyarországi szociális munka válsága [The Crisis of Social Work in Hungary]. Esély 3: 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, Gemma, Bronwyn Crammond, and Eleanor Malbon. 2019. Personalisation Schemes in Social Care and Inequality: Review of the Evidence and Early Theorising. International Journal for Equity in Health 18: 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtin, Emilie, Nadia Jemiai, and Elias Mossialos. 2014. Mapping Support Policies for Informal Carers across the European Union. Health Policy 118: 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csoba, József, Edit Oláh, and Fanni Maszlag. 2022. A szociális életpályamodellel kapcsolatos dilemmák [Dilemmas Related to the Social Life Course Model]. Párbeszéd: Szociális Munka folyóirat [Dialogue: Social Work Journal] 9: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czibere, Katalin, and Dóra Mester. 2020. A magyar szociális szolgáltatások és főbb jellemzőik 1993 és 2018 között [Hungarian Social Services and Their Main Characteristics between 1993 and 2018]. In Társadalmi Riport 2020 [Social Report 2020]. Edited by Tamás Kolosi, Iván Szelényi and István György Tóth. Budapest: TÁRKI Zrt, pp. 434–49. [Google Scholar]

- Da Roit, Barbara, Aina Ferrer, and Francisco Moreno-Fuentes. 2013. The Southern European Migrant-Based Care Model. European Societies 15: 577–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvas, Ágnes, Zsuzsa Farkas, Péter Győri, Edit Kósa, Péter R. Mózer, and József Zolnay. 2013. A szociálpolitika egyes területeire vonatkozó szakpolitikai javaslatok [Policy Proposals for Certain Areas of Social Policy]. Esély 6: 3–137. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission: Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion. 2024. Report on Access to Essential Services in the EU—Commission Staff Working Document. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2767/447353 (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Federation of European Social Employers. 2019. The Social Services Workforce in Europe: Current State of Play and Challenges, Report. Bruxelles: Federation of European Social Employers. [Google Scholar]

- Federation of European Social Employers. 2022. Staff Shortages in Social Services Across Europe. Bruxelles: Federation of European Social Employers. [Google Scholar]

- Ferge, Zsuzsa. 2017. Magyar társadalom- és szociálpolitika 1990–2015 [Hungarian Society and Social Policy 1990–2015]. Budapest: Osiris Kiadó és Szolgáltató Kft. [Google Scholar]

- Győri, Péter. 2012. Elszabotált reformok—‘Tékozló koldus ruháját szaggatja’ Dialógus Mózer Péterrel [Sabotaged Reforms—‘A Prodigal Beggar Tears His Clothes’ Dialogue with Péter Mózer]. Esély 2: 100–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, István. 2017. The Structure of the Personal Social Services in Hungary. In Annales Universitatis Scientiarum Budapestinensis de Rolando Eötvös Nominatae. Sectio Iuridica. Budapest: Eötvös Loránd Tudományegyetem, pp. 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, István, and Andrea Szatmári. 2020. The Transformation of the Municipal Social Care System in Hungary—In the Light of the Provision of Home Care Services. Lex Localis—Journal of Local Self Government 18: 691–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozma, József. 2007. A szociális szolgáltatások modernizációjának kérdései a szociális munka szempontjából [Issues of Modernization of Social Services from the Perspective of Social Work]. Kapocs. Available online: http://szociologiaszak.uni-miskolc.hu/kapott_anyag/kapocs.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Kozma, József. 2020. A szociális munkások munkahelyi biztonságáról, a kockázatokról és a szakma identitáskríziséről [On Social Workers’ Workplace Safety, Risks, and the Profession’s Identity Crisis]. Párbeszéd: Szociális Munka folyóirat [Dialogue: Social Work Journal] 1: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamura, Giovanni, Elke Mnich, Mary Nolan, Beata Wojszel, Björn Krevers, Lefteri Mestheneos, and Helga Döhner. 2008. Family Carers’ Experiences Using Support Services in Europe: Empirical Evidence from the EUROFAMCARE Study. The Gerontologist 48: 752–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichsenring, Kai. 2004. Developing Integrated Health and Social Care Services for Older Persons in Europe. International Journal of Integrated Care 4: e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llena-Nozal, Ana, Rodrigo Fernández, and Sarah Kups. 2022. Provision of Social Services in EU Countries. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers No. 276. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantu, Sandra, and Paul Minderhoud. 2023. Struggles over social rights: Restricting access to social assistance for EU citizens. European Journal of Social Security 25: 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meleg, Szilvia. 2020. Bérek és bérpótlékok 2020 a szociális, gyermekjóléti és gyermekvédelmi ágazatban [Wages and Wage Supplements 2020 in the Social, Child Welfare and Child Protection Sector]. Available online: https://www.tamogatoweb.hu/letoltes2020/berek_berpotlekok_2020_01_02.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Meleg, Szilvia. 2021. Párbeszéd a romok között—Reformgondolatok a személyes gondoskodást nyújtó szociális szolgáltatásokról [Dialogue among the Ruins—Reform Ideas for Social Services Providing Personal Care]. Párbeszéd: Szociális Munka folyóirat [Dialogue: Social Work Journal] 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netten, Ann, and Bleddyn Davies. 1990. The Social Production of Welfare and Consumption of Social Services. Journal of Public Policy 10: 331–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyer, Gerda. 2021. Welfare state regimes, family policies, and family behavior. In Research Handbook on the Sociology of the Family. Edited by Norbert F. Schneider and Michaela Kreyenfeld. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyitrai, István. 2021. A szociális vezetők értékei: Értékek, jellemzők, tulajdonságok—A szociális szolgáltatásokban dolgozó intézményvezetők választásai alapján [Values of Social Leaders: Values, Characteristics, Attributes—Based on the Choices of Institutional Leaders Working in Social Services]. Párbeszéd: Szociális Munka folyóirat [Dialogue: Social Work Journal] 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roit, Barbara, and Brigitte Bihan. 2010. Similar and Yet So Different: Cash-for-Care in Six European Countries’ Long-Term Care Policies. Milbank Quarterly 88: 286–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roit, Barbara, and Cristiano Gori. 2019. The transformation of cash-for-care schemes in European long-term care policies. Social Policy & Administration 53: 515–18. [Google Scholar]

- Timonen, Virpi, Jennifer Convery, and Seán Cahill. 2006. Care Revolutions in the Making? A Comparison of Cash-for-Care Programmes in Four European Countries. Ageing and Society 26: 455–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungerson, Clare. 2004. Whose Empowerment and Independence? A Cross-National Perspective on ‘Cash for Care’ Schemes. Ageing and Society 24: 189–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varsányi, Erika. 2006. Szociális munka és kultúra [Social Work and Culture]. Beszélő. Available online: http://beszelo.c3.hu/cikkek/szocialis-munka-es-kultura (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Villalba, Elena, Isabel Casas, Francesc Abadie, and Montserrat Lluch. 2013. Integrated Personal Health and Care Services Deployment: Experiences in Eight European Countries. International Journal of Medical Informatics 82: 626–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, Stephen. 2003. Local Orders and Global Chaos in Social Work. European Journal of Social Work 6: 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollmann, Hellmut. 2018. Public and Personal Social Services in European Countries from Public/Municipal to Private—And Back to Municipal and ‘Third Sector’ Provision. International Public Management Journal 21: 413–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).