Abstract

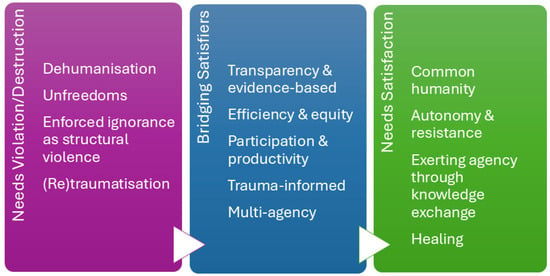

This article utilises Max-Neef’s Human Scale Development (HSD) framework (1991) to answer two research questions: what impact does government and community-based social protection (SP) have on UK asylum-seeker wellbeing; how are interactions with all forms of SP, both as giver and receiver, supporting or harming the satisfaction of asylum-seekers’ fundamental human needs at this time? The research study utilised a mixed-methods, collaborative, case study design situated within a refugee and asylum-seeker (RAS) support charity in Southwest England. Methods included peer-led Qualitative Impact Protocol interviews, Photovoice, surveys, and staff interviews. Data were subjected to an inductive, bottom-up process on Causal Map software (version 2, Causal Map Ltd., 39 Apsley Rd., Bath BA1 3LP, UK) and the analysis used the HSD framework. We found eight over-arching themes. The four main needs-violators/destroyers of asylum-seeker wellbeing were dehumanisation, unfreedoms, enforced ignorance, and (re)traumatisation, and the four main needs-satisfiers were common humanity, autonomy and resistance, exerting agency through knowledge exchange, and healing. Five policy and practice-focused bridging satisfiers are recommended to help move individual and collective experience from a negative to a positive state in the research population. Policy and practice should be transparent and evidence-based, efficient and equitable, supportive of participation and productivity, trauma-informed, and multi-agency.

1. Introduction

The 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) call for the introduction of integrated social protection (SP) and development policies to end all forms of poverty, foster inclusive societies, support human rights, and improve collective wellbeing. To achieve this, the goals recognise the need to combat “inequality within and among countries” (UN 2015), focusing on population groups at the highest risk of poverty and marginalisation, such as international migrants and ethnic and racial minorities (UN 2018). Yet in the UK, it has been argued that SP is not administered in an equitable way, and a growing body of literature provides evidence of what authors and their research participants describe as the negative impact of an increasingly hostile, punitive, and discriminatory SP system on asylum-seeker wellbeing, creating destitution, marginalisation, and poor mental health in this population (Fitzpatrick et al. 2015; Mayblin et al. 2020; Pettitt 2013; Refugee Action 2023; Refugee Council 2004). Reinforced by consecutive governments, this hostile policy environment (Kirkup and Winnett 2012) that facilitates growing border militarisation across Europe (Linke 2010) and often inappropriate distribution of arriving asylum seekers across the country has failed to discourage individuals and families from seeking refuge in Britain. Further, civil societies are increasingly responding to and filling welfare gaps left by constricting government provisions (Mayblin and James 2019); this is despite political and media attempts to curtail public sympathies through their portrayal of incoming asylum seekers as unwanted invaders or illegal, economic migrants in disguise (Mayblin 2019; Parker 2015).

Social protection is traditionally understood as a formal state mandate and responsibility, organised and delivered by government ministries, departments, and their agents to eradicate poverty. However, Devereux and Sabates-Wheeler offer a more comprehensive definition that speaks to the SDG’s wider articulation of poverty alleviation as follows,

describes all public and private initiatives that provide income or consumption transfers to the poor, protect the vulnerable against livelihood risks, and enhance the social status and rights of the marginalised; with the overall objective of reducing the economic and social vulnerability of poor, vulnerable and marginalised groups.(Devereux and Sabates-Wheeler 2004, p. 9)

Devereux’s (2019) comprehensive framework suggests a wider range of implementation actors, including the following: government and its agents that provide formal SP, such as universal credit, maternity pay, and disability benefit; private SP, available mainly through the private sector or tripartite agreements among employers, government, and individuals, offering insurance schemes and contributory welfare schemes such as pensions; semi-formal SP, provided by non-governmental, formally registered organisations (NGOs) such as charities and faith-based groups; and informal SP, obtained through social support networks, including peers, friends, neighbours, and family.

A systematic literature review (James 2021) and policy critique (James and Forrester-Jones 2022) found that formal SP was inadequate to meet asylum-seekers’ needs and was often experienced as harmful to their wellbeing. Community-based SP (including both semi- and informal) were, conversely, found to be mainly positive for wellbeing, fulfiling wider psychosocial needs alongside practical, spiritual, and legal support. However, the literature review and critique highlighted the lack of first-hand accounts of the effect of these different forms of SP on asylum-seeker wellbeing and the need for further research to test effective and inclusive approaches for the articulation of wellbeing in this population. In response to this research need, a mixed-methods, collaborative research project was devised, including peer-led Qualitative Impact Protocol (QuIP) interviews, Photovoice project, survey with refugees and asylum seekers (RAS), NGO staff interviews, and formal feedback mechanisms. (For a critique of the QuIP and Photovoice research elements, see (James 2023a, 2024). Following a review of wellbeing literature and to further the current scholarship, we chose to test Max-Neef’s (1991) Human Scale Development (HSD) framework as a novel analytical tool. This paper provides a case study of our theoretical and methodological process. Although there are several examples of the HSD approach in social sciences literature (Cardoso et al. 2021; Cuthill 2003; Guillen-Royo 2015), the conceptual framework has not, to the authors’ knowledge, been used in immigration or asylum research to date. Examples of the HSD framework as a data analysis tool also appear to be lacking. As such, this case study provides a practical exemplar of a novel utilisation of the framework in contexts where a collaborative workshop-based process is unattainable.

First, we introduce HSD theory. We then provide details of the study dataset and how HSD theory was adapted for the project context. Following a summary of the key findings, we conclude with a methodological discussion highlighting the benefits and limitations of using the HSD approach in the study. Our objectives are two-fold. First, to provide a practical exemplar and critique of the methodological technique to support the future utilisation of HSD theory in contexts where community-based workshops are unethical or unsuitable. Second, to present the key themes of our primary research concerning the impact of SP on asylum-seeker wellbeing. Our findings add to a growing body of RAS wellbeing literature and will be of interest to practitioners, researchers, and local and national policymakers.

2. Wellbeing and Human Scale Development Theory

One of the earliest wellbeing scholars, Maslow (1970), related human wellbeing to a hierarchy of human needs, starting with basic needs, such as subsistence and safety, and progressing up through psychological needs and self-fulfilment (or self-actualisation) in order of priority. More recently, Sen (1985, 2001) and Nussbaum (2011) conceptualised wellbeing as a set of capabilities or opportunities to be able to carry out life-fulfiling activities (or functionings) such as being well-nourished, getting married, being educated, and travelling (Robeyns and Byskov 2020). Max-Neef’s (1991) Human Scale Development (HSD) theory combined both ideas, defining wellbeing as the fulfilment of nine fundamental needs—subsistence, protection, affection, understanding, participation, leisure, creation, identity and freedom—satisfied through capabilities and functionings.

Given the UK asylum-seeker populations’ diverse histories, experiences, cultures, personal attributes, and contexts, we decided Max-Neef’s nine needs and satisfiers offered coherence and order to research findings without a requirement to pre-designate boundaries or impose descriptive terminology on participants’ own articulations of wellbeing. The contingent nature of needs’ satisfiers changing over time as societies evolve or individuals migrate among cultures, religions, or geo-political environments was also deemed beneficial when investigating asylum seekers who had travelled from a range of countries to the UK, with all the potential differences that may occur regarding how their needs are, or could be, met longitudinally. Finally, as concepts of human need and wellbeing may be understood, experienced, or articulated divergently, particularly across cultural boundaries, there was a belief that participants’ experiences of wellbeing should be self-reported and given equal value. As such, the HSD framework was adopted to organise emergent themes collected through collaborative data collection.

3. Max-Neef’s Human Scale Development Theory and Matrix

Max-Neef’s (1991) HSD theory posited that all people have nine fundamental needs, irrespective of time or place, which can be satisfied, but may also be pseudo-satisfied, inhibited, or destroyed/violated in different ways contingent on individual or community history, culture, personal/collective attributes, context, or environment (see Table 1 for satisfier descriptions). Beyond basic subsistence to stay alive, all needs are deemed of equal value, inter-related, and interactive; one need might require multiple satisfiers or, conversely, one satisfier may fulfil multiple needs.

Max-Neef designed a two-day stakeholder workshop-based process to help communities self-diagnose the current state of their needs’ satisfaction, what support they are or are not receiving or giving out, and what support would help (or not help) satisfy their needs. During the workshop, two matrices are completed by participants: negative and positive (Table 2). Each matrix includes 36 empty cells. The nine axiological categories of need are set against four existential categories—being (attributes), doing (actions), having (norms, laws, institutions, tools), and interacting (spaces, times). The negative matrix is populated with ‘destructive elements’, harmful satisfiers that either destroy/violate the satisfaction of a need immediately or over time, pseudo-satisfy one or multiple needs, or inhibit the satisfaction of one need by over-satisfying another. The positive matrix is populated with singular or synergic satisfiers (satisfying multiple needs at once) to demonstrate how participants believe their needs are, or could be, satisfied optimally. Once populated, descriptions are distilled down into simple terms and phrases to identify the key positive and negative satisfiers observed by the community. Finally, the matrices are interrogated alongside one another by participants to consider what bridging satisfiers, both endogenous and exogenous, could encourage positive community development, moving individual and collective experiences from a negative to a positive state.

Table 2.

Empty Human Scale Development needs matrix (based on Max-Neef 1991, pp. 44–48).

Max-Neef’s theory and matrices (which we placed in a table for ease of understanding) were used in our study to answer two main research questions:

- What positive and negative impact does government and community-based SP have on the self-reported wellbeing of UK asylum seekers?

- How are interactions with all forms of SP, both as giver and receiver, supporting or harming the satisfaction of UK asylum seekers’ nine fundamental human needs at this time, as defined by Max-Neef (1991)?

4. Study Design and Method

The study design was a one-time qualitative exploration of SP in relation to asylum seekers living in a city in Southwest England. Fieldwork took place over a 10-month period at an RAS support charity located in the centre of the city.

Data collection tools were chosen to foreground the voices of asylum seekers and provide collaboration opportunities, which were hoped to improve the wellbeing of those involved (James 2023a). To this end, we chose to use the Qualitative Impact Protocol (QuIP) (Copestake et al. 2019), Photovoice, a survey, collection of participant feedback data, and RAS charity staff interviews. We describe each instrument below:

The QuIP is a deep-dive, semi-structured interview and analysis technique designed to investigate changes in the wellbeing of beneficiaries of development interventions in complex contexts, mitigating against potential response bias by asking about changes in broad domains of respondents’ lives following a personal baseline. In our project, asylum seekers were questioned about changes in six life domains that could be mapped to Max Neef’s matrix since government dispersal:

- Practical and material support—accommodation, food, and essential items

- Work—paid or voluntary

- Skills and education

- Freedom of choice and movement

- Relationships

- Overall wellbeing

Peer RAS interviewers were trained to dig deeply during interviews to uncover the self-reported drivers of the changes identified by participants in each domain.

Photovoice (Wang and Burris 1997) is a participatory needs assessment tool. In its simplest form, Photovoice research involves defining a research question or theme and considering who holds relevant knowledge to inform it; recruiting photographer participants from the target population; co-developing the project with participants; conducting training in photographic methods and research ethics; providing a time-frame for participant-photographers to take photographs; a workshop where participants describe and discuss their photographs; and a dissemination event to share the findings illustrated by participant-chosen photographs with a wider audience. In our study, participants were asked to photographically document what made them happy or made their life easier and what made them unhappy or their life harder. At a discussion workshop, photographers shared the meaning attached to their images, followed by a group discussion. The Photovoice project culminated in a public exhibition of all images (James 2022).

Survey data were collected from service users of local RAS support organisations. Questions focused on respondents’ knowledge of, and access to, community support services, their experiences of interacting with these services, and recommendations for improvement.

Feedback was collected from Photovoice participants during the discussion workshop and through post-project interviews. Each peer QuIP researcher was interviewed following the end of their project involvement. Feedback cards were completed by Photovoice exhibition attendees.

Interviews were conducted with RAS support organisation staff who were questioned about the role of their organisations in RAS wellbeing, concerns and challenges within the sector, and their opinion on current and future government and community SP provision.

4.1. Recruitment and Sample

Seventeen QuIP-recorded interviews were completed with asylum seekers (two QuIP interviewees also took part in the Photovoice project), nine of which were undertaken by peer researchers recruited from the RAS community.

Seven asylum seekers and three recent refugees took part in a Photovoice project. The project aimed to recruit only asylum seekers; however, a small number of recent refugees requested to take part and, due to the potential benefit to their wellbeing, they were admitted. Their different legal status was considered during the analysis. The QuIP and Photovoice key informant findings were triangulated with qualitative survey data from 47 members of 5 local RAS organisations (who did not take part in the Photovoice or QuIP), 23 pieces of feedback data (1 Photovoice participant, 3 QuIP peer researchers, and 19 Photovoice exhibition viewers), and 9 RAS charity staff interviews.

4.2. Sample Characteristics

The QuIP, Photovoice, and survey data were mainly collected from asylum seekers, with a small number of recent refugees included in the Photovoice project (as described above) and the survey. The full cohort came from a wide range of countries, particularly Iran, Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan, and El Salvador, with participants speaking over 20 languages. They had been living in the UK for between 3 months and 18 years. They were between the ages of 17 and 54, and their highest educational attainment varied from primary school to post-graduate level. Women accounted for 32% of the data and men 68%.

4.3. Analysis

An inductive, bottom-up process using Causal Map software (James 2023b; Powell et al. 2024) (Version 2, Causal Map Ltd., 39 Apsley Rd., Bath BA1 3LP, UK) was applied to key informant narrative statements, Photovoice discussion dialogue, and survey data, with two types of factors coded in the dataset:

- Consequence factors—changes reported in the wellbeing of participants since moving to the city.

- Influence factors—the drivers of these wellbeing changes as reported by participants.

Influence and consequence factors were linked together to form chains, demonstrating the complex causal wellbeing pathways in individuals’ lives. The software linked the causal pathways to underlying narrative statements, evidencing each relationship: 130 factors were developed in total, and 2851 causal links were coded (see James 2024 for the full Causal Map outputs). The second stage of analysis utilised an adapted HSD process and the Causal Map factor codes to consider how asylum seekers’ needs were being satisfied or inhibited by different forms of SP.

4.4. Adapting the Human Scale Development Approach

Optimally, the QuIP and Photovoice participants would have followed up their project involvement by attending an in-person HSD workshop. However, three factors meant this was deemed unsuitable. Firstly, there were language constraints, as six different languages were spoken by the key informant cohort, and several individuals had little or no English language skills. Secondly, there was evidence during the QuIP interview process of participants’ fear that candid discussion concerning the asylum application process might negatively affect their claim. Thirdly, there were attendance challenges during the Photovoice project, given the busy weekly schedules of participants. These concerns led us to opt out of a multi-day HSD workshop for ethical reasons (see ethics section below).

Instead of an HSD workshop, the first author populated negative and positive matrices using the 130 factors developed in Causal Map. Each matrix cell was filled with relevant factors that expressed participants’ positive or negative perceptions of their needs’ satisfaction. Through a multi-stage process, the factors were distilled to produce a small number of overarching themes representing participants’ views on how their needs were being harmed (inhibited/destroyed/violated/pseudo-satisfied), satisfied, or they felt could be satisfied, in relation to all forms of SP. Finally, based on the full project dataset, including participant feedback, staff interviews, pertinent existing literature, and ethnographic fieldnotes, five SP-focused synergic bridging satisfiers were developed.

4.5. Ethics

The study received a favourable ethical opinion by the University of Bath, Social Science Research Ethics Committee (SSREC) [reference: S21-102]. The ethical challenges of using participatory Photovoice and peer-research with asylum seeker participants have been discussed in detail elsewhere (James 2023a), but briefly stated here, an anti-oppressive approach in line with human-centredness was helpful in guiding ethical decisions throughout the research process. Drawing from a wide theoretical background, including Marxist, feminist, critical, indigenous, anticolonial, and antiracist literature (Amadasun and Omorogiuwa 2020; Baines 2011) we felt strongly that notwithstanding the ethical need for participant informed consent, voluntariness, autonomy, confidentiality, and anonymity (all transcripts were de-identified at the time of transcription, and we use pseudo-initials for quotes), it was important to avoid viewing our participants through a protection lens, rather than a respect lens (Gifford 2013); the former being a default position that many researchers and ethics committees are apt to take due to the deontological shift in ethical requirements for human research that is underpinned by the medical model. In fact, there is a growing awareness that, despite exposure to traumatic experiences and challenging conditions in settlement contexts, many asylum seekers and refugees show tremendous resilience (Hutchinson and Dorsett 2012; Obijiofor et al. 2018; Perry 2011), and a discourse of respect, agency, capacity, and post-traumatic growth may be more appropriate. We hoped that this research project’s emancipatory research design, practice, and working relationships went some way towards this alternative approach.

5. Results

Eight overarching (four positive and four negative) themes (Figure 1) were delineated from the 130 factors coded in Causal Map. The four main needs violators/destroyers were dehumanisation, unfreedoms, enforced ignorance as structural violence, and (re)traumatisation. The four main needs satisfiers were common humanity, autonomy and resistance, exerting agency through knowledge exchange, and healing. Each theme is described below. Following this, the authors recommend five policy and practice bridging satisfiers that may go some way towards moving individual and collective experience from the negative (needs are violated/destroyed/inhibited/pseudo-satisfied) to a positive (needs are satisfied) state.

Figure 1.

Consolidated HSD Matrix.

5.1. Needs Violation/Destruction

5.1.1. Theme One: Dehumanisation

Dehumanisation is the psychological and socio-political process of disavowing fundamental human characteristics so that people are devalued as ‘other’ and viewed as less human or non-human and therefore less worthy of the rights and humane treatment the majority group expect (Smith 2012; Varvin 2017). Dehumanisation often begins with scapegoating (Debney 2020; Savun and Gineste 2019), the creation of “a suitable enemy” (Fekete 2009) blamed for a current societal problem such as unemployment, and is catalysed and fueled by inflammatory language that leads to side-taking, anger, an inability or unwillingness to listen to alternative viewpoints and a loss of empathy (Brown 2018). A staff member described how government policy and practice dehumanise asylum seekers:

It’s clear at the moment the government’s intention is to make this a hostile environment and to not be welcoming, or to be welcoming to certain types of people. When you start with that kind of policy framing at the top, then it’s gonna just filter down to the way people are treated. The whole asylum process is very alienating and dehumanising and violent actually in different ways.(O, staff member)

This quote reflects civil servants’ statements about how “the Home Office has a role in dehumanising you as an individual (Civil servant B)” (Mayblin 2019, p. 12). By labelling asylum seekers as a homogenous group of illegal, unwanted invaders (Parker 2015), crossing the Channel in large numbers to submit ‘bogus’ asylum applications (Home Office 1998) as ‘economic migrants in disguise’, Conservative government views have been heralded by right-wing media, despite robust evidence to the contrary (Mayblin 2019; Mayblin and James 2016). Asylum seeker presence has been blamed for increasing unemployment figures, terrorism, and a reduction in SP resources for citizens (Taylor 2015; Wike et al. 2016), and it is argued that this negative rhetoric has built up a sense of stigmatisation and moral exclusion2 for this group (Kirkwood 2016), allowing government ministers to enact increasingly hostile, structurally violent policies with minimal backlash from UK citizenry. Our research participants discussed dehumanisation through instances of racism and discrimination and by referring to the negative impacts of a range of formal SP mechanisms such as hotel accommodation, legal restrictions, low levels of financial support, and complex and bureaucratic administration in the asylum application system. Outcomes included poor physical and mental health, lack of human connection/integration, loss of autonomy, insecurity, stress, liminality, occupational deprivation, and enforced destitution, as described by Participant Z:

Asylum seekers in hotels, we are not in a good situation mentally… We not allowed to register for college and can’t find any job as a volunteer…We are under pressure and a lot of stress because we have absolutely no idea what is going to happen to us tomorrow… I find it difficult to be a part of society because … I live in the middle of nowhere.(Z, asylum seeker, Iran)

Dehumanisation of asylum seekers was shown to synergistically violate all nine fundamental human needs by robbing individuals of their identity, merging their unique humanness into a predetermined, prejudged homogenous group. Assumed guilty while awaiting trial through the asylum system (Mayblin 2019, p. 12), their freedom was severely restricted by hostile SP mechanisms that fall short of all but the most basic level of protection and subsistence. The isolation and disconnection caused by living in bridging hotels, a lack of information about formal and semi-formal SP, and dispersal or redispersal away from established community support networks violated the satisfaction of the need for participation, affection, understanding, and leisure. Finally, current policies that criminalise employment for most asylum seekers, a six-month registration ban for new asylum seekers seeking college English classes, and a lack of information about, or housing away from, community-run skills development activities prevented occupational participation and the opportunity for increased understanding and creation.

5.1.2. Theme Two: Unfreedoms

Unfreedoms, described in the dataset as ‘legal restrictions’ and ‘loss of autonomy’ in different areas of individuals’ lives, are mechanisms and consequences of dehumanisation. Canning (2020, p. 1) argues that “structures of coercive control” in the UK asylum system inflict harm on asylum seekers through policies and laws that minimise personal and interpersonal autonomy. The repercussions of these restrictive structures were discussed repeatedly by participants, resulting in a sense of liminality, occupational deprivation, disempowerment, and inhumanity as described below:

[T]ime for waiting for interview and give visa, this very important, very bad. I am human, why waiting for 1 year, 2 years, they don’t treat like humans, they take so long to respond. I can’t open bank account and I cannot [get] driving license. Just waiting before I am normal. It has stopped my life.(R, asylum seeker, Iran)

The 1990s heralded a steady decline in the rights and freedoms of asylum seekers. The Asylum and Immigration Appeals Act (1993) removed the right to permanent council housing and limited financial entitlements to 90% of the standard rate British citizens received, reducing them to 70% in the Asylum and Immigration Act (Asylum and Immigration Act 1996). Responsibility for asylum seeker SP was also transferred to local authorities in 1996, and in 1999, a new Immigration and Asylum Act (1999) created an entirely separate National Asylum Support Service (NASS), fully detaching asylum seekers from mainstream benefits. Since 1999, scholars argue this ‘restrictionist regime’ (Zetter 2000, p. 679) has grown steadily more controlling and punitive with the introduction of dispersal housing, often to deprived areas with poor quality accommodation, a lack of community SP providers, and social exclusion (Parker 2017). Financial benefits have further decreased to 58% of a UK citizen’s standard rate3, paid employment is prohibited for most asylum seekers, and waiting times for asylum decisions have increased by 408% since December 2017 (Sasse et al. 2023).

Subtheme: Liminality

Liminality or disorientation, caused by long application delays, was a significant sub-theme of unfreedoms, synergically violating the satisfaction of all nine human needs. Too much time spent isolated in hotel rooms with little knowledge of, or money to travel to, formal (college), semi-formal (charitable), or informal (friends and peers) activities impeded healthy leisure, participation, affection, understanding, creation, and subsistence leading to boredom, reduced social capital, dwindling skills, wasted potential, and material lack. Liminality also intensified feelings of insecurity, stress, and hopelessness as months or years passed with little progress towards receiving refugee status. This precarious position violated the satisfaction of the need for protection, freedom, and identity, with participants losing confidence and self-belief, and experiencing poor mental health and apathy, even when activities were available to them (Burchett and Matheson 2010; Morville 2014; Smith 2015), as described by the quote below:

When you are in the asylum process, you’re in a frustration… you don’t really have the desire of being happy… you are all, all, all the time worried about your situation. And then some[one] came up to you [saying], ‘Look, …we can cheer you up doing this and that. But you don’t really have the… you don’t really want to do these things.(L, staff member, refugee)

Subtheme: Occupational Deprivation

Alongside liminality, Smith (2015, p. 615) suggests the “economic, social and political context of asylum in the UK creates a condition of occupation deprivation”, or what some have labelled ‘occupational apartheid’ when exclusion is “based on certain characteristics such as ethnic background, gender, sex, religion, social condition, among others” (Olivares-Aising 2018, p. 477). “[P]eople are inherently occupational; they require meaningful, purposeful activity in order to function and achieve mental wellbeing” (Moore et al. 2022, p. 6), and occupational deprivation has been found to erode skills, exacerbate social exclusion and isolation, intensify the impact of ill-health and poverty, increase vulnerability, and foster community tensions (Lunden 2012; Smith 2015; Suleman and Whiteford 2013). Occupation is not limited to employment but encompasses any meaningful role, activity, or routine that brings structure, purpose, integration, functional life skills, identity, or independence (WFOT 2023). Occupation is an important determinant of mental health (Moore et al. 2022, p. 6), and participants highlighted how a lack of autonomy over occupation and discontinuity caused by liminality had halted “the chosen or anticipated path of their occupational life” (Smith 2015, p. 615). They discussed how occupational deprivation acted as a violator of participation, subsistence, protection, creation, freedom, and identity, comparing previous occupations and skills with their current controlled existence, as described in the quotes below.

I think I’m just wasting my time and I’m not using my abilities. I’m just waiting for two years and do nothing. I’m losing my skills and forgetting everything which I learned at university.(N, asylum seeker, Iran)

My knowledge and skills have negatively changed … I used [to] fix cars and repair after damage from accident in my country and I can’t do that now here unless I got my leave to remain … It is the job that I love and make money from it but I’m not legal to do that now.(A, asylum seeker, Egypt)

Subtheme: Restrictive Policies and Practices

Alongside occupational deprivation, hostile asylum policies synergically violated or impeded the satisfaction of all nine of the participants’ human needs by removing autonomy in important areas of their lives. Firstly, participants reported that the policy and practice of dispersal housing (which, in one way, satisfied their need for basic subsistence) actually removed any choice they had to live geographically or in what type of accommodation. This violated their wider needs of freedom, participation, affection, understanding, subsistence, protection, creation, leisure, and identity by separating asylum seekers from social support networks, locating them in isolated hotels away from support services and forcing individuals to live in shared housing, where anti-social behaviour was sometimes experienced. Forced recurrent dispersal led participants—who had overcome the challenges of initial dispersal and who had built social capital—to move, seemingly without reason or warning, to other UK regions.

Additional restrictions manifested through strict mealtimes and repetitive, unhealthy menus in hotel accommodation, coupled with a lack of financial support to buy food elsewhere. Accommodation rules also meant some participants were unable to choose who they spent time with and where, as non-residents were sometimes prohibited from entering government housing. This restricted the opportunities for developing social networks that could offer informal SP and the creation of social capital, impeding the satisfaction of the need for affection, protection, participation, leisure, and freedom.

5.1.3. Theme Three: Enforced Ignorance as Structural Violence

[I]gnorance should not be viewed as a simple omission or gap, but rather as an active production. Ignorance can be an actively engineered part of a deliberate plan.(Proctor and Schiebinger 2008, p. 9)

A particularly detrimental aspect of government policy is the lack of information given to new asylum seekers when they arrive in the UK and are dispersed; information about the asylum process in general, the location where they are to be housed, and support services in that locality. Intersecting with other disadvantages and vulnerabilities such as trauma, disability, and lack of English language skills, this (un)conscious withholding of information led our participants to feel isolated, bewildered, and lacking in practical, legal, and emotional support, which contributed to decreasing mental health and violated the satisfaction of all nine of their human needs, as described by a staff member below:

[T]he main challenge is the system itself … The fact that they don’t have access to basic information about the process, insecurity about the future is what is the biggest challenge and what leads them to suffer from a lot of stress, a lot of anxiety, depression.(M, staff member)

Borrelli’s (2018) research into the “use of ignorance, passive or active, subtle or crude” (p. 97) by street-level bureaucrats when dealing with irregular migrants, highlights how “systems of oppression aim to silence the subject as the deliberate maintenance of un-knowledge and the withholding of information towards migrants incapacitates them” (see also Tuana 2008, p. 99). Mulvey (2015) suggests that the UK’s hostile asylum policies seek to restrict integration. Ignorance, therefore, may be actively encouraged, “created by a structural setup of the state and its agencies, which through their rules, frameworks and hierarchies create opportunities for ignorance to arise” (p. 98). Through policies of ignorance, information manipulation (McGoey 2012), and the dependence of many asylum seekers on third parties for linguistic and legal advice and support, asylum seekers’ ability to exert agency is limited (Jackson 2013), power inequalities are maintained, and structural violence is legitimised (Borrelli 2018, pp. 97, 101). The negative effects of this informational void were evident in the dataset through discussion pertaining to asylum seekers’ feelings of isolation in hotel accommodation, lack of knowledge about local support services, unhelpful hotel staff, poor administration, long waiting times with no word about pending asylum claims, and anxiety following the release of partial knowledge on issues such as Rwandan deportation. There were also frustrations with the poor service provided by the government-appointed Migrant Help phone line and a lack of information given about dispersal locations, even when enroute, as described below.

[N]o one told us anything about the process or gave us any information so when we were about to [be] moved [from the Asylum Reception Centre] we were very scared because we didn’t know what was going to happen or where they were taking us.(C, J & D, asylum seekers, El Salvador)

These mechanisms of (un)intentional ignorance violated the satisfaction of asylum seekers’ need for understanding, freedom, and protection, increased feelings of insecurity and fear, and impeded their ability to exert agency in the fulfilment of their need for identity, creation, leisure, participation, affection, and subsistence. This structurally violent, enforced ignorance intersected with other unfreedoms within the formal SP system to maintain docility, segregation, and isolation within the population.

5.1.4. Theme Four: Re(Traumatisation)

Trauma encompasses the lasting adverse effects on an individual’s physical, emotional, social, spiritual, and mental functioning and wellbeing following exposure to life-threatening or emotionally disturbing events, or an on-going negative state, such as poverty, discrimination, or oppression (Center for Health Care Strategies 2021). Research indicates that asylum seekers “frequently endure premigratory traumatic events that correlate with distress” (Morgan et al. 2017, p. 654; see also Bogic et al. 2015), such as “threat to life, human rights violations, incarceration, conflict, war, murder of close family, and multiple loss” (Fernandes et al. 2022, p. 152). However, some scholars have warned against focusing solely on a premigratory trauma discourse, suggesting that it may “pathologi[se] distress in ways that neglect the impact of the postmigratory environment” (Morgan et al. 2017, p. 654; see also Papadopoulos 2001; Watters 2001), finding that the isolation and restrictions experienced by UK asylum seekers “remained … significant predictor[s] [of PTSD scores] even when controlling for the effects of all premigratory stress predictors and age”, particularly in relation to immigration insecurity, poor asylum administration, occupational deprivation, poverty, lack of human connection, and autonomy (ibid, p. 665).

Staff participants reported increasing trauma symptomology and a decline in mental health in asylum seekers in recent years linked to hostile government policies, secondary trauma associated with large numbers living in bridging hotels, and the COVID-19 pandemic:

[W]e are just getting more cases of safeguarding issues. This is a growing problem because of years of hostility towards asylum seekers and refugees. … I think a lot of people are just so traumatised that maybe they just don’t want to engage [with semi-formal or informal SP], they can’t engage.(J, staff member)

Though several participants commented on the positive nature of British law and order in general, many also described the actual asylum application process as an extended period of fear, anxiety, insecurity, poverty, and physical and mental decline, violating their need for protection, affection, subsistence, and freedom. Interpersonal bonds and social networks were curtailed by government policies designed to hinder integration, connection, and acculturation, such as dispersal housing, employment restrictions, and the six-month waiting period for English classes. Disconnection from their homeland, relationships and culture, occupation deprivation, stigmatisation, and the liminal space that asylum seekers inhabit also negatively impacted their ability to make sense of their journey, and narrate a coherent, purposeful identity and hopeful vision for the future. This lack of human and cultural connection and journey coherence impeded the satisfaction of their need for protection, affection, understanding, participation, creation, freedom, and identity.

[W]e don’t feel that immigrants are integrated … our kids don’t still join education here and we think that really affects their wellbeing and mental health. … [C’s] child got really, really depressed and now is with the psychiatric doctor and one of her [J’s] sons was going in the same direction … [T]here is frustration as parents that we can’t really fulfil our children’s needs, so psychologically it’s very difficult. As adults we have cried a lot.(C, J & D, asylum seekers, El Salvador)

Finally, their belief in justice was damaged by inefficient Home Office administration that caused long delays, repeated application refusals, legal challenges, and re-applications. It was also affected by (un)intentional ignorance or dis-information that limited asylum seekers’ agency to represent their case effectively, or find legal, practical, or social support for themselves, impeding the satisfaction of their need for protection, subsistence, participation, affection, understanding, leisure, creation, identity, and freedom.

5.2. Needs Satisfaction

5.2.1. Theme Five: Common Humanity

Common humanity is the antithesis to dehumanisation. It is the belief that humans are fundamentally alike and a discursive effort to construct “people as belonging to a common moral community, of acting in ways that are understandable, and as deserving of support” (Kirkwood 2017, p. 116), with equal compassion and respect. It recognises “group-based differences” but maintains “a moral imperative for equality” (Kirby and Harris 2021, p. 402). Alongside the psychosociological definition, the ‘law of common humanity’ has been relied upon in legal representation of individuals found destitute, injured, or unsupported by different forms of UK SP as far back as Kemp v Wickes (1809)4, including more recent cases concerning the cessation of formal SP for refused asylum seekers (Salih & Rahmani n51 para 69, in York 2017, p. 23).

In the data, common humanity was found to synergistically satisfy all nine human needs in a variety of ways. The need for affection, protection, subsistence, identity, and participation was supported by the giving and receiving of informal SP by asylum seekers. Informal SP took many forms, including the sharing of food and essential items, teaching new skills to others such as cookery or IT, giving advice about, or accompaniment to, support services, hospitality, offering a floor to sleep on, or providing free services such as hairdressing. These acts of kindness occurred both organically, through social networks built up in shared housing, religious congregations, community-based communal spaces and colleges, and through more intentional gatherings and support interventions provided by community organisations such as volunteering roles, mentoring programmes, and activity groups. Research participants talked about giving advice or practical support because it was the ‘right thing to do’, with empathy borne out of similar asylum experiences, despite cultural and individual differences. Others said they had been helped by RAS on arrival in the UK or, conversely, wished there had been others to help them when they needed it. Their experiences are encapsulated by the following quote:

I’ve been an asylum seeker for many years and literally sometimes I was dying with nothing on the pavement and many lovely people, like angels, helped me, rescued me … I love to put this love in a circle. If I help others, it’s lovely, but if others help someone else it would be amazing, and this world would be a better world.(S, refugee, Iran)

Acts of common humanity supported positive identity construction and increased self-confidence as participants took on the role of ‘organic intellectual’, passing on advice that increased others’ understanding (Gramsci 1982; in Vickers 2016) and enabling feelings of solidarity, empathy, and support. The role of ‘organic intellectual’ also boosted identity and satisfied the need for participation, understanding, and creation in some participants who, through discussing RAS wellbeing and voicing their opinions, felt more connected to wider society and positive that they were contributing to a greater good. Common humanity was experienced through a more multicultural, welcoming community in the city, when compared to previous dispersal locations. The friendly, family environment and human connection/integration found in community-based SP spaces also satisfied the need for protection, affection, and identity, and was described as ‘being part of society’ or feeling human/alive. Finally, fun and relaxing activities, such as sports, board games, walking, or simply sitting in a comfortable, companionable space while eating a hot meal, fulfiled the need for leisure, and the ability to take part in a range of volunteering roles promoted positive identity and a temporal sense of autonomy and freedom, psychologically and physically away from difficult housing situations and the stress associated with the asylum application system.

5.2.2. Theme Six: Autonomy and Resistance

We found that participants utilised a wide range of actions to enact agency and develop a sense of productivity, belonging, and humanity. Many resisted liminality by constructing busy routines, giving them a sense of purpose, human connection, and personal development. Learning new skills, such as English, Maths, IT, and cooking, was important, linked to a hoped-for future, when refugee status would allow individuals to build a life.

[I]t’s very good to learn something. It will help you out in your future. … If I did some classes, like computer classes, like some other occupation … if I learn electrician, in the future I can go and get a job, a good job … you know with good money.(Photovoice discussion)

Subtheme: Occupation and Meaningful Activity

Occupation, in the form of volunteering in community organisations and the provision of informal SP to other RAS, mediated a range of positive benefits, including self-confidence and worth, human connection and integration, solidarity and support, improved psychological wellbeing, and opportunities for intellectual stimulation, voicing opinions, and advocacy. Smith (2015, p. 616) describes how asylum seekers utilise occupation to construct meaning in their lives through the lens of doing, being, belonging, and becoming, “expressing the pleasure of getting up with a purpose, and ending the day feeling tired”. Similarly, volunteering and giving informal SP satisfied our participants’ need for affection, understanding, participation, creation, identity, and freedom in the giver through the HSD’s four existential categories of:

- Being—autonomous, psychologically well, human, resilient, hopeful for the future.

- Having—improved skills, access to volunteering/informal SP opportunities, cultural understanding and local knowledge, improved future job opportunities, and social capital.

- Doing—connection with RAS and the community, informal SP, volunteering, solidarity and support, activism/advocacy, voicing opinions, new and existing skills, giving advice.

- Interacting—at intentional spaces and gatherings at semi-formal SP organisations, government accommodation, community locations, neighbourhoods, and religious buildings.

Community-based housing and the accompanying weekly financial allowance facilitated limited levels of freedom of movement and activity satisfying, on some level, the need for subsistence, protection, affection, understanding, participation, leisure, creation, identity, and freedom. Shared housing tended to be closer to the city centre than government-appointed hotels, where semi-formal support services allowed residents to utilise meeting spaces, planned activities, volunteering roles, and social networking opportunities, with less reliance on cost-prohibitive public transportation. Cooking facilities and money to purchase groceries supported autonomy in food consumption and mealtimes, and relaxed rules concerning outside guests in some properties allowed hospitality and socialising.

5.2.3. Theme Seven: Exerting Agency Through Knowledge Exchange

Research participants reported two main avenues through which they satisfied their need for understanding and, once in possession of this understanding, exerted agency to choose how to fulfil their need for freedom, protection, identity, creation, leisure, participation, affection, and subsistence. Firstly, the role of informal SP within the RAS community was discussed as playing a positive role in sharing information about their locality and what community-based support services were available. Knowledge imparted included where to find volunteering opportunities, free food and essential items, sport and social activities, emergency accommodation, cultural shops, church meetings, and English and other classes.

I introduce Aid Box Community and Borderlands to many people from the hotel so if they like to [do] volunteering they can be in contact with them.(Z, asylum seeker, Iran)

Linguistic capabilities and personal experience of the hurdles seeking refugee status were particularly important elements of informal SP for research participants, findings supported in wider research (James 2021; Lewis 2007; Mcgovern and Yong 2022; Murray 2015; Wenning 2018). Asylum seekers were able to provide information through informal interactions in a range of community settings, engaging others through their mother tongue and offering a sense of solidarity which helped bridge the gap between community organisations and those who could benefit from their services (Hunt 2008).

Community organisations were also significant knowledge-exchange and social capital conduits via which participants received information about formal and community-based SP and more specialised legal advice. This knowledge increased participants’ ability to exert agency in asylum applications and government housing and financial support enquiries. It also helped them access mental and physical health interventions, mobile technology ownership, IT training and English language training, advocacy services, and involvement with activism and decision-making.

Asylum seekers, refugees, often either can’t speak the language or don’t have a voice just because they know very little or nothing about the country they’re living in or their rights. And that’s the [role of the] semi-formal, is the advocacy work and advice work that’s life changing for many people.(J, staff member)

5.2.4. Theme Eight: Holistic Healing for Wellbeing

Holistic healing focuses on the whole person—psychological, physical, social, spiritual, cultural, and environmental—restoring balance within and among all of these human dimensions to allow individual and communal flourishing and fulfilment (Anon 2022). Despite widespread academic and practitioner acknowledgement of the traumatic impact of asylum policy on UK asylum seekers, our participants described instances of happiness, positivity, resilience to hardship, and post-traumatic growth5.

HSD theory does not define wellbeing, other than the satisfaction of fundamental needs, so two main mechanisms were used to investigate how participants described wellbeing in their own lives. Firstly, QuIP interviewees were asked to articulate their understanding of the term before being questioned about changes in their own wellbeing since moving to the city. Secondly, Photovoice participants captured images in response to the prompt, ‘what makes you happy or improves your life as an asylum seeker?’, adding descriptive words to images during the discussion workshop. These interviews and photographic self-reported indicators of wellbeing are set against the HSD fundamental needs list in Table 3. Participants expressed wellbeing in terms that encompassed all nine HSD categories, indicating how holistic healing was occurring, or had the potential to occur, in their lives.

Table 3.

Consolidated research participant indicators of wellbeing.

Community organisations facilitated healing firstly by providing safe, welcoming, non-judgmental spaces for intentional, regular communal activities. This act supported the need for protection, leisure, and creation. Secondly, access to food and essential items, practical support, and physical health interventions, such as exercise or mindfulness classes, satisfied the need for subsistence. Thirdly, knowledge and skills transfer, such as legal and local advice and English and other classes, increased individual and collective agency and capabilities, satisfying the need for understanding and freedom. Fourth, the opportunity to take part in meaningful occupations, such as volunteering or advocacy activities, fulfiled a desire to be productive, responsible, and useful, satisfying the need for participation and identity. Finally, through all of the above interventions, social networks developed, leading to many acts of informal SP, directly supporting the need for affection for some, but also indirectly the satisfaction of all nine need categories through a range of informal support given among the wider RAS community. Informal SP was also catalysed through religious and cultural networks and gatherings, most notably, church congregations, where informal SP was mainly given by city residents, including refugees.

Though formal SP was described as a generally traumatic experience, some formal mechanisms did support holistic healing. By bringing asylum seekers together and integrating them into the local community, communal housing facilitated social network creation, affording an opportunity framework for a range of informal SP and social support (Forrester-Jones and Grant 1997) that satisfied a range of needs. Community housing and weekly financial allowance also provided subsistence, some sense of protection, and freedom of movement and association. These, in turn, led to more interaction with community-based SP initiatives and the wider community with the potential to support all nine human needs, as described above. College attendance was also a healing process, mediating social and friendship networks and improving understanding, particularly of the English language. English skills were highly prized and deemed essential by many for proper participation in society.

Participants’ stories of change and growth, in spite of post-migratory trauma, demonstrate significant resilience. However, participants mainly expressed healing and wellness as contingent on a hoped-for future, when they were granted refugee status, with its accompanying freedoms, integration, security, and occupation. This suggests that, though some degree of healing and wellness can occur in their current liminal context, until the pervasive trauma of the UK asylum application process comes to an end, either individually through the granting of refugee status or constitutionally through a change in policy, healing will be partial and temporal, with everyday (re)traumatisation a normative mechanism of an inhumane asylum system.

5.3. Bridging Satisfiers

Based on the positive and negative matrices, five bridging satisfiers were formulated (see Figure 1). In a traditional HSD process, these are endogenous and exogenous actions that participants believe will encourage positive community development, moving individual and collective experiences from the negative to positive state. In this research context, the external nature of the needs-violators/destroyers and the severe constraints imposed on asylum seekers’ autonomy resulted in bridging satisfiers concentrated on aspirational changes to government and local policy and practice rather than personal changes instigated by participants. Due to the nature and scope of the research project, the proposed policy changes are normative and conceptual, while more practical suggestions are included at the local practitioner level where the empirical research was centred. The bridging satisfiers imagine a national and local asylum policy that is transparent and evidence-based, efficient and equitable, participative and productive, trauma-informed, and multi-agency, an antithesis to the increasingly hostile and punitive UK policy landscape described by scholars, practitioners, and those waiting in the asylum system today.

5.3.1. Transparency and Evidence Based

Mayblin (2016, 2019) and Singleton (2015) revealed a poor evidence base for UK asylum policy, particularly in relation to the widespread acceptance of an unevidenced ‘economic migrant in disguise’ pull factor construal (Mayblin and James 2016). Senior Home Office personnel interviews reported the common acceptance of large, quantitative operational data that “aligned with existing Home Office priorities and construals of how and why irregular migration for asylum occurs” and the dismissal of smaller qualitative datasets “on the basis that they were not ‘representative’” unless they happened to support the government stance (Mayblin 2019, pp. 14, 15). Mayblin and Singleton suggest two reasons for this evidence exclusion. Firstly, that senior Home Office staff simply do not want to view evidence that contradicts ‘pull factor’ ideology, and, secondly, conceived wisdom that qualitative data lacks methodological rigour compared to objective statistics. To improve the informational basis of asylum policy, deeply embedded values, beliefs, and attitudes held by government officials should be reflexively deliberated through multi-agency dialogue that considers how the cognitive and normative content of policies has been established, and the power dynamics intertwined with their creation. Qualitative data, which can provide detail about why something is happening and its impact, should form decision-making, supporting agency through the use of participative, creative, action research, and policy lab methodologies (Forrester-Jones et al. 2025).

Transparency and a commitment to data accuracy can tackle discrimination and stigmatisation by furnishing civil society with easy-to-navigate, balanced, and evidence-based immigration data. As such, media and political reports should be fact checked, particularly in relation to inflammatory issues such as the annual proportion of asylum seekers entering the UK in relation to other migrant categories. Evidence should also be available concerning the rationale behind and anticipated outcomes of new immigration policy, and the impact of existing policies should be impartially reported. In addition, civil society and those directly affected by immigration policy should be meaningfully included in every stage of the policy planning and implication cycle, with power dynamics addressed to provide appropriate, safe spaces for their inclusion.

An informational deficit was linked to negative wellbeing by participants, compounded by language limitations, tight deadlines for the submission of paperwork, and limited access to legal advice and representation. Transparent information sharing is essential to facilitate asylum seekers’ agency in the pursuit and realisation of formal and semi-formal SP. At the local level, the collection and dissemination of learning (both successes and failures) among community organisations and other interested stakeholders could support mutual trust building, collaborative, joined-up strategic planning, and improved services for asylum seekers and refugees.

5.3.2. Efficiency and Equity

An escalating backlog of asylum applications (Walsh et al. 2023) and the government’s admission that their antiquated administrative processes are contributing to the crisis (HM Government 2021) suggest the need for a significant workforce enlargement and improved administrative systems. The substantial number of asylum refusals that are later overturned in court also support procedural changes to ensure the correct application of asylum law at initial reading. A joined-up, multi-agency approach, including funding for local legal and linguistic support and more flexibility in submission timescales, could improve applicants’ abilities to complete documentation appropriately, increasing the number of applications correctly assessed at their first screening.

Given evidence of the positive impact that semi-formal SP has on wellbeing (James 2021), it may be a cost-efficient way to meet some asylum seekers’ needs, utilising volunteer labour and its role as a catalyst for informal SP. The government should, therefore, consider increased funding for community-based initiatives and research the cost-efficiency of providing SP through intentional collaborations between formal and semi-formal SP providers.

The Migration Observatory has labelled current UK immigration SP “a tale of two protection systems”, describing the different experiences that those who are welcomed as refugees have compared to those seeking asylum independently, even when they arrive from the same country (McNeil 2022; see also Morris 2001, on the stratified rights regime). To support individuals’ right to claim asylum in the UK, effective and easily accessible safe routes of arrival are necessary; routes that include both in-country referrals, when time and safety allow, and access from intermediate countries when individuals have no option but to flee immediately.

Finally, efficiency and equity in local-level support provision are important for organisations serving a diverse, often geographically dispersed population. An awareness of equitable service provision was noted during fieldwork through service adaptation, which saw food delivered to those unable to travel during the pandemic and weekly trips to government hotel accommodation to reach newly arrived asylum seekers with information and support. However, participants also reported challenges in accessing assistance due to issues such as language, mental/physical health and, most notably, transport costs. Free transportation would allow asylum seekers to access crucial community-based welfare services and increase opportunities for informal SP.

5.3.3. Participation and Productivity

Over the past 20 years, there have been sustained calls from NGOs, trade unions, and MPs, for asylum seekers to be allowed to undertake paid employment while awaiting application decisions (Gower et al. 2022; Independent Asylum Commission 2008; Mayblin 2014), a policy that would bring the UK in line with the EU, the USA, and Canada. Despite this, employment remains illegal for most. Alongside the psychological, social, and physical benefits of engagement that work provides (Forrester-Jones et al. 2004), there may be potential economic advantages to society. Indeed, in contrast to political and media rhetoric that focuses on the heavy economic burden of UK asylum seekers, research suggests RAS can have either no effect or a positive impact on national economies (CEBR 2020; D’Albis et al. 2018; Ruist 2014). A re-examination of the foundations of current employment restriction policy is, therefore, required, as is the cost–benefit analysis of allowing asylum seekers employment while awaiting application decisions. Analysis should include wider costs of mental health and skill depletion associated with occupational deprivation and the escalating housing costs of those unable to support themselves.

The benefit and importance of community participation in policy formation and evaluation is supported by numerous government reports (FOSS 2008; Local Government and Public Involvement in Health Act 2007; London Councils 2008), including “better targeted interventions, processes and outcomes”, “more responsive organisations”, “greater sense of control over services and accountability”, and skills and capabilities development for local people (FOSS 2008, pp. 3, 4). As such, finding appropriate and meaningful ways to include asylum seekers and their advocates in policy deliberation is important.

At the local level, our study demonstrated that participation and productivity through community-based volunteering and activities positively impacted asylum seekers’ lives. Finding creative ways to increase the amount and scope of participative occupation for individuals with limited autonomy over their daily lives could have a significant impact on wellbeing outcomes during the often drawn-out, liminal application space. Nationally, a system that can evidence volunteering or skills development may also support future employment or educational access and could impact the perception of UK residents concerning the positive impact that asylum seekers have on their local communities and the UK economy.

5.3.4. Trauma-Informed Policy

Participant stories and wider literature provide evidence of the traumatic nature of the asylum application system, from initial interviews through the lengthy waiting period in a hostile environment, to repeated legal appeals (Morgan et al. 2017, p. 665; see also; Peñuela-O’Brien et al. 2022; Silove et al. 1997). At each stage, the system needs to be considered from a trauma-informed perspective with the input of skilled psychological professionals to minimise the harm inflicted on potentially already traumatised individuals (Schock et al. 2015).

Matheson and Weightman (2021) suggest that social, cultural, and practical factors impact asylum seekers’ ability to engage in trauma therapy. Adapted modalities and interdisciplinary psychosocial interventions should, therefore, be made available (Hinton and Good 2016; Peñuela-O’Brien et al. 2022; Pointon 2005; Schauer 2011). Given the complexity of trauma symptomology and how culture and spirituality impact individuals’ experiences and articulations of distress, culturally sensitive interventions are crucial. Trust, peer modalities, consistent and elongated support, and somatic interventions that help individuals recognise how trauma is stored physically (Van der Kolk 2014) are also important in the process of healing.

The challenging role that staff and volunteers in community settings fulfil for service users also needs to be acknowledged, including how this may lead to vicarious traumatisation (Puvimanasinghe et al. 2015). Debriefing and therapeutic services are, therefore, crucial for staff and volunteers, reducing staff sickness and encouraging the sharing of best practice.

5.3.5. Multi-Agency

The wide-ranging local-level support already available to RAS and the escalating costs of increasingly hostile border control and deterrence policies in the UK support a shift towards a multi-agency, centrally funded but locally organised SP policy. Community-based initiatives already provide millions of pounds of goods, services, and volunteer time to RAS (Mayblin and James 2019), and this paper demonstrates their positive impact on individual and communal wellbeing (James 2021). However, though demand for community-led interventions is growing, funding sources continue to contract and grow more precarious, leading to limited-service provision and high levels of staff stress (Mayblin and James 2019; Price 2016; Streets 2022). As such, rather than relying on ad hoc, private, short-term, or supporter-based funding streams, increased public funding for localised interventions, with planning informed by those directly impacted by services, is recommended to support a comprehensive vision of SP.

City-wide partnerships or communities of practice (CoPs)6 may provide effective oversight for collaborative and joined-up, semi-formal provision supporting capacity and knowledge sharing, effective signposting, and the reduction of service duplication. A nationwide database of service provision, accessible to both semi-formal providers and individual RAS and detailing support services in each locality, would address the current inability of RAS to find desperately needed community support. For local organisations, it may also be an effective tool in signposting RAS that are redispersed to new localities, reducing the isolation and stress associated with dispersal and offering access to community-based services shown to support needs satisfaction. Finally, a multi-agency, joined-up, and comprehensive SP approach could foster opportunities for meaningful engagement, supported by robust sectoral evidence. It could lead to a more collaborative SP provision focused on the full satisfaction of all fundamental human needs, both citizen and immigrant, and facilitate meaningful accountability mechanisms throughout the sector and with civil society.

6. Methodological Discussion

Max-Neef’s HSD diagnostic process was adapted for use as a data analysis tool to organise and interrogate a mixed dataset, including QuIP, Photovoice, survey, staff interview, and feedback data. The researchers hoped the process would highlight key themes in the dataset related to the two main research questions. Firstly, the positive and negative impact of government and community-based SP on the self-reported wellbeing of UK asylum seekers, and, secondly, how interaction with all forms of SP, both as giver and receiver, supports or harms the satisfaction of UK asylum seekers’ nine fundamental human needs. As a data manipulation tool, the HSD diagnostic process was helpful, allowing the analyst to attach the 130 factors coded in Causal Map as needs-satisfiers to the positive and negative matrices. This provided a valuable picture of the depth of impact of some factors over others, as they were input into the matrices multiple times under different needs categories. The process also allowed the analysis to focus on the satisfaction of each need separately, giving each due attention rather than concentrating on more obvious aspects of wellbeing. Once all needs categories had been fully populated with Causal Map factors, the view was widened to consider all the needs at once, looking for repeated or similar terminology that could be condensed into key themes through a multi-stage distillation process. The methodical nature of the diagnosis technique, therefore, allowed a large, complex dataset to be reduced slowly and systematically.

However, despite the usefulness of the HSD process, its utilisation was limited in this context. Firstly, the theory behind HSD is that communities have the knowledge, skills, and abilities to diagnose their own needs’ satisfiers, rather than these being formulated by external ‘experts’, and this is done through a facilitated, in-person workshop, where the matrices are populated by community members. Unfortunately, fieldwork limitations discussed earlier precluded this part of the intended process. In populating the matrices only with Causal Map factors that were generated directly from first-person accounts, an attempt was made to foreground participants’ opinions. However, in the formulation of consequence and influence factors in Causal Map and the linking of causal chains, the researchers’ own interpretations were undoubtedly imprinted onto the data. To counter this, and test the validity of the findings, feedback was requested from participants and those with lived experience at two dissemination presentations, and these supported the validity of identified themes.

Secondly, the magnitude or longitudinal effect of the needs-violators and satisfiers is unknown due to data collection being taken at one time point. Through triangulation with wider literature, it was possible, however, to draw indications concerning recurrent themes and how these relate to current SP policy and practice, both nationally and locally.

Finally, in a traditional HSD process, once the matrices are complete and key themes identified, the community members themselves formulate bridging satisfiers that they will own and take action on to improve wellbeing in their context. For the asylum-seeking participants, the potential for ownership of the changes required to improve their wellbeing was limited. This was partly due to the legal restrictions and intersectional vulnerabilities they were experiencing, but more importantly, because the amendments required for significant positive change were found to be mainly external, related to policy or societal attitudes/perception, issues the participants had little control over. The HSD framework’s ability to highlight this was valuable, increasing understanding concerning the limitations of self-development that asylum seekers can achieve due to exogenous systems of control and attitudinal influence. The completion of the matrices also highlighted important ways in which asylum seekers were already using their agency to fulfil some of their needs through giving and receiving informal SP within their social networks, often facilitated by community organisation settings. In this way, the HSD tool illustrated the resilience, ingenuity, and common humanity of humans, even when restricted and oppressed by external forces. It also demonstrated the positive impact of human connection and of simply ‘being with’ others to support processes of healing and post-traumatic growth.

On balance, given the benefits and limitations of the highlighted HSD process, the researchers believe HSD can be employed as a useful analytical framework, where the opportunity for in-person workshops is contextually impractical. Our experiences provide a useful case study and methodological critique of the adaptation of the HSD process to respond to research constraints experienced when working with a hard-to-reach, transient population. Though an HSD workshop was not feasible, first-person data were collected using contextually appropriate tools and the HSD theoretical framework was utilised to systematically interrogate the complex, mixed dataset to understand and present overarching themes. It is hoped that our experiences will raise awareness of the wider uses of the HSD approach and provide helpful guidance to support its utilisation in a range of disciplines, particularly those where methodological adaptation is required in response to challenging fieldwork environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.J. and R.F.-J.; Data curation, M.J.; Formal analysis, M.J.; Funding acquisition, M.J.; Investigation, M.J.; Methodology, M.J. and R.F.-J.; Project administration, M.J.; Resources, M.J.; Software, M.J.; Supervision, R.F.-J.; Validation, M.J. and R.F.-J.; Visualization, M.J.; Writing—original draft, M.J.; Writing—review & editing, M.J. and R.F.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Economic and Social Research Council grant number 149376688 and the APC was funded by UK Research and Innovation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study received a favourable ethical opinion by the University of Bath, Social Science Research Ethics Committee (SSREC) [reference: S21-102].

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Notes

| 1 | The satisfier typology is based on text which can be found in Max-Neef (1991, pp. 30–34). We updated and re-worded the attributes to be more relevant to our theoretical and study context. |

| 2 | “[O]utside the boundary in which moral values, rules, and considerations of fairness apply. Those who are morally excluded are perceived as nonentities, expendable, or undeserving” (Opotow 1990, p. 1). |

| 3 | Comparison between universal credit for over 25s (£77 per week) and asylum seekers’ Section 95 support (£45 per week) in January 2023. |

| 4 | Socialist-based belief that human beings are inherently altruistic and will empathy and compassion towards each other. |

| 5 | “[P]ositive psychological change experienced as the result of the struggle with highly challenging life circumstances” (Karagiorgou et al. 2018). |

| 6 | The concept of a community of practice was first introduced by Brown and Duguid in 1991 and is understood as a group of people who care about the same problem/issue and who intentionally commit to a unified view of learning with each other and from each other (Brown and Duguid 1991). |

References

- Amadasun, Solomon, and Tracy Beauty Evbayiro Omorogiuwa. 2020. Applying anti-oppressive approach to social work practice in Africa: Reflections of Nigerian BSW students. Journal of Humanities and Applied Social Sciences 2: 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anon. 2022. What Is Holistic Health? Overview and Career Outcomes. St. Catherine University. Available online: https://www.stkate.edu/healthcare-degrees/what-is-holistic-health (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Asylum and Immigration Act. 1996. London: TSO. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1996/49/contents (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Asylum and Immigration Appeals Act. 1993. London: TSO. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1993/23/contents (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Baines, Donna. 2011. Doing Anti-Oppressive Practice: Social Justice Social Work. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing Co., Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Bogic, Marija, Anthony Njoku, and Stefan Priebe. 2015. Long-term mental health of war-refugees: A systematic literature review. BMC International Health and Human Rights 15: 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrelli, Lisa Marie. 2018. Using Ignorance as (Un)Conscious Bureaucratic Strategy. Qualitative Studies 5: 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Brené. 2018. Dehumanizing Always Starts with Language. Brené Brown. Available online: https://brenebrown.com/articles/2018/05/17/dehumanizing-always-starts-with-language/ (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Brown, John Seely, and Paul Duguid. 1991. Organizational Learning and Communities-of-Practice: Toward a Unified View of Working, Learning, and Innovation. Organization Science (Providence, R.I.) 2: 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchett, Nicole, and Ruth Matheson. 2010. The need for belonging: The impact of restrictions on working on the well-being of an asylum seeker. Journal of Occupational Science 17: 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canning, Victoria. 2020. Corrosive Control: State-Corporate and Gendered Harm in Bordered Britain. Critical Criminology 28: 259–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, Rodrigo, Ali Sobhani, and Evert Meijers. 2021. The cities we need: Towards an urbanism guided by human needs satisfaction. Urban Studies 59: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]