Fake News in Tourism: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Fake News

1.2. Approaches to Handling Misinformation in Communication

1.3. Fake News and the Tourism Aspect

2. Review Method

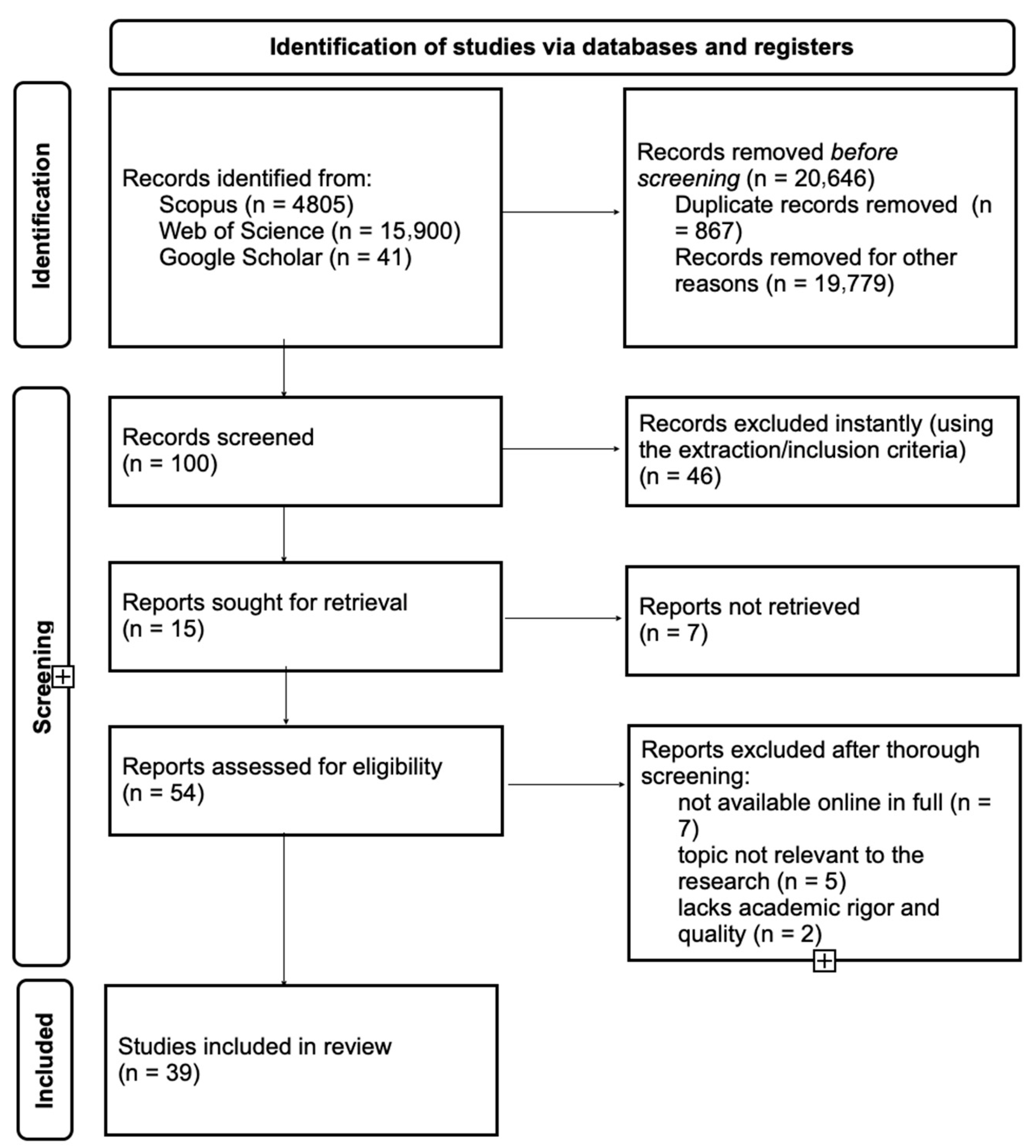

2.1. PRISMA Method

2.2. Study Selection and Data Extraction Process

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3. Results

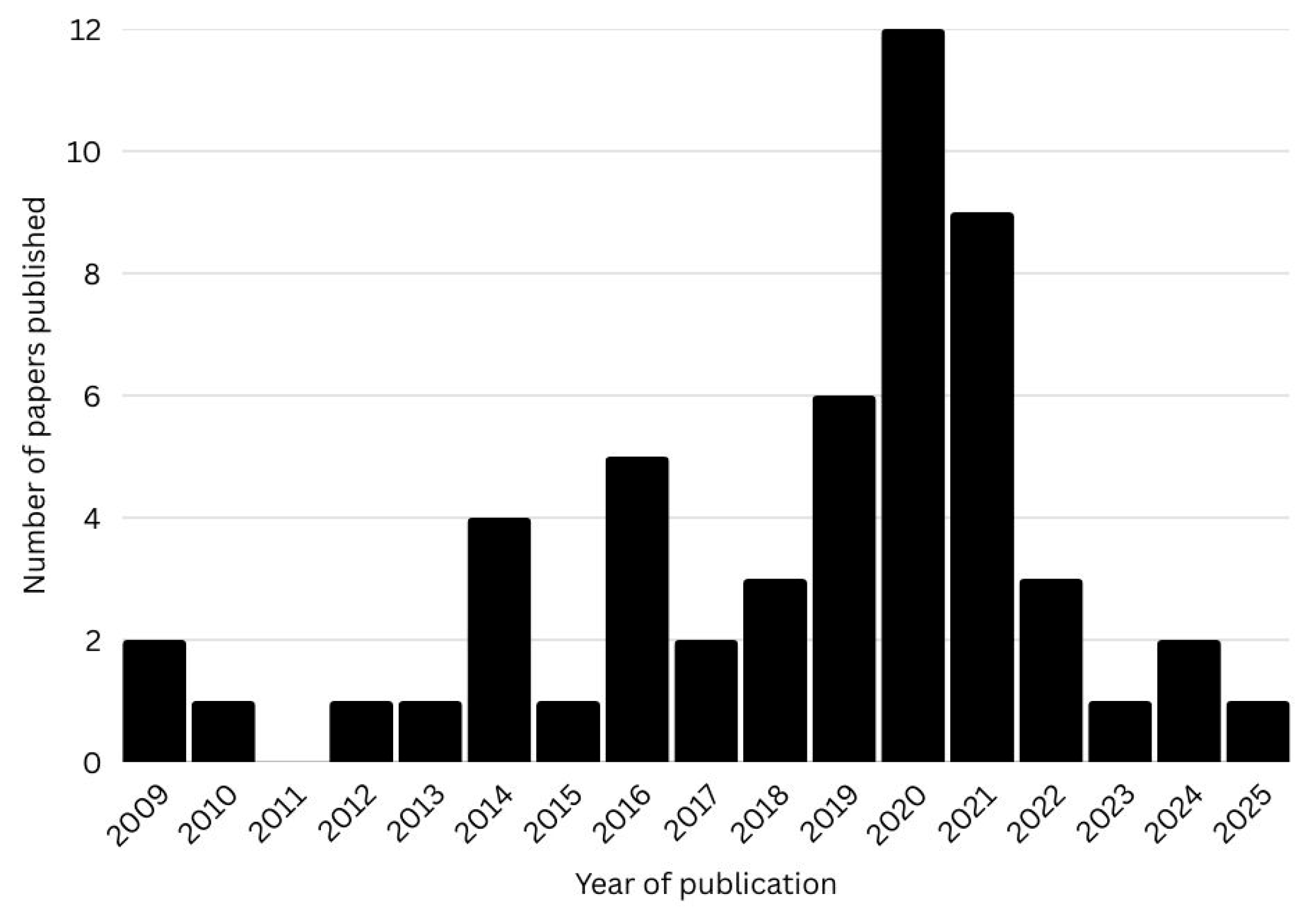

3.1. Chronological Distribution of the Articles

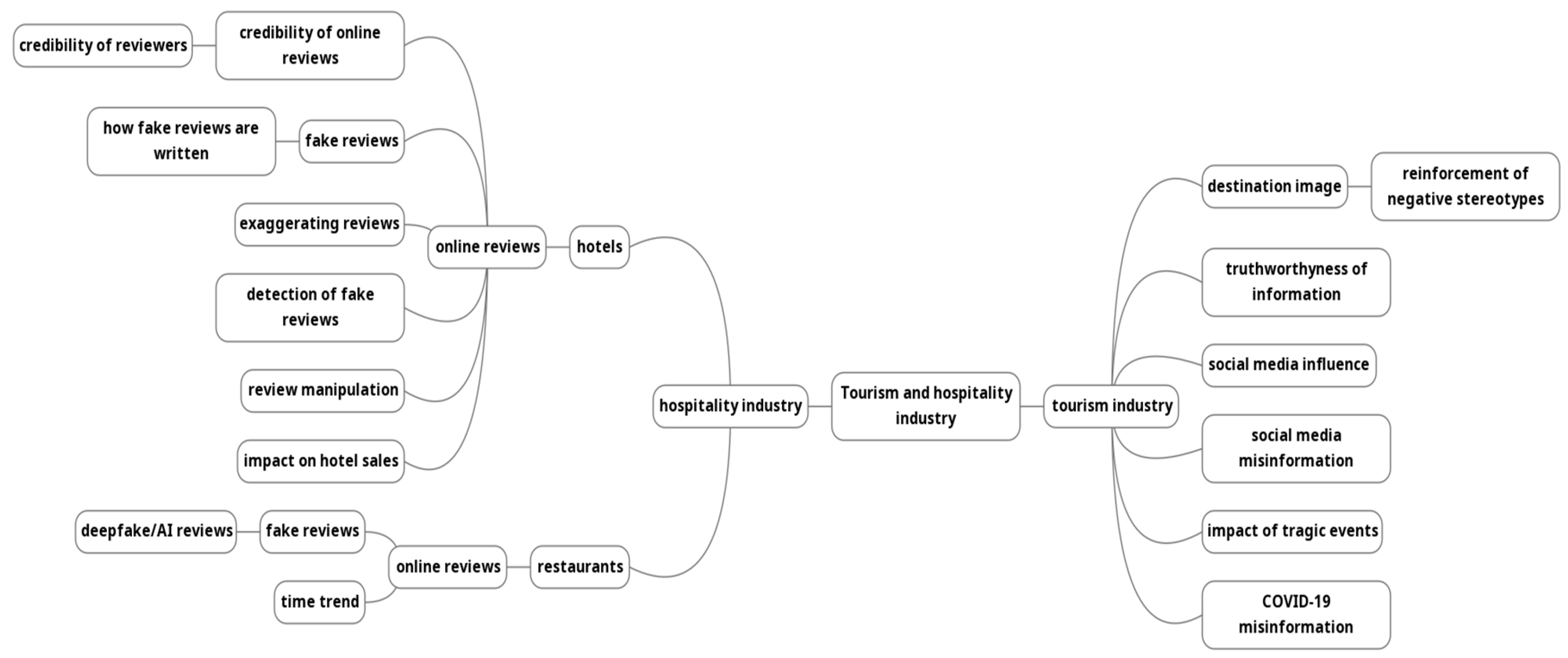

3.2. Topical Distribution of the Articles

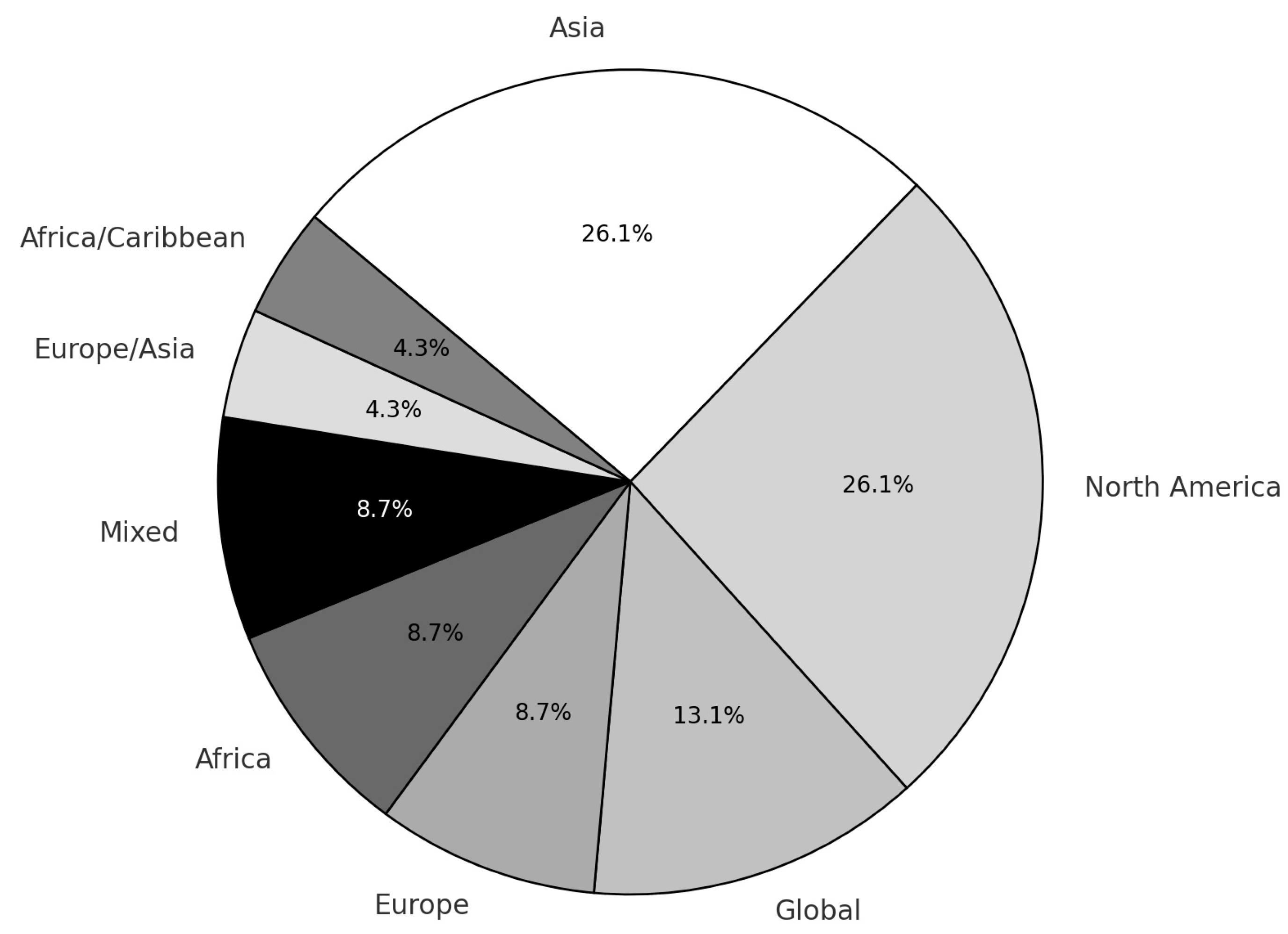

3.3. Geographical Distribution of the Articles

4. Discussion

4.1. Articles Focusing on Fake Reviews in the Hospitality Industry

4.2. Articles Focusing on Fake News in the Tourism Industry

5. Limitations and Future Research Paths

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Data Extraction Form

| Study ID | Author(s) | Title | Year | Journal/Proceedings | Context | Key Findings | Limitations/Relevance to Topic | Future Research Paths | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abdallah, A. (Abdallah 2021) | Fake news, false advertising, social media, and the tourism industry | 2021 | International Journal of Development Research | tourism: explores the role that news plays in our everyday lives and the impact of fake news on the tourism industry | The paper establishes a link between ‘Fake News’ and social media and reveals how ‘Fake News’ is at times purposefully adopted by destinations as a means of providing a positive image rather than a negative one. | Limited academic sources in the topic, case studies/examples mainly from online sources | ethical questions and doubt raised of the legality of purposefully using fake news in marketing | qualitative, literature review |

| 2 | Abedin, E., Mendoza, A., Karunasekera, S. (Abedin et al. 2020) | Credible vs. fake: a literature review on differentiating online reviews based on credibility | 2020 | Conference on Information Systems | hospitality: fake online reviews (Yelp, eBay, Booking.com) in the hospitality industry | Using co-topic analysis, the paper identifies important attributes used to assess the credibility of online reviews. They further classify these attributes into four main categories: review-centric, reviewer-centric, receiver and environmental attributes. | There is a lack of research that considers environmental and receiver-centric attributes, and particularly there is no study among data-driven approaches using receiver-centric attributes. | Addressing some other problem areas overlooked in the literature, e.g., coherence of reviews for the same products in different platforms, and investigate the differences between fake news and fake reviews in more details. | qualitative, literature review |

| 3 | Ahmad, W., Sun, J. (Ahmad and Sun 2018) | Modeling consumer distrust of online hotel reviews | 2018 | International Journal of Hospitality Management | hospitality (online hotel reviews) | Reviewer attributes of fake identity and ulterior motivation directly influence distrust, which further leads to consumers’ psychological discomfort and engagement in negative electronic word-of-mouth. Surprisingly, psychological discomfort positively affects repeat purchase intentions. Service failure attribution positively moderates the relationship between reviewer attributes and distrust. | Research limited to China (Beijing) and not specifically focusing on fake reviews. | Future work could focus on exploring the influence of message-based factors (e.g., online reviews diversity) and website-based factors to obtain greater variance in dis- trust. | quantitative, survey using a 5-point Likert-scale |

| 4 | Anton, E., Teodorescu, C.A., Vargas, V. M. (Anton et al. 2020) | Perspectives and reviews in the use of narrative strategies for communicating fake news in the tourism industry | 2020 | Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Excellence | tourism/travel: case studies of fake news of destinations | The author identifies several case studies from around the world and states that manipulation of information shapes differently the image of tourism destinations, accommodation units, cruise ships and even tourist attractions mostly in order to produce higher economic benefits. | Limited academic sources in the topic, case studies/examples mainly from online sources | The phenomenon requires more attention by tourism academics in order to analyze consumer behavior and crisis management. | qualitative, literature review |

| 5 | Ayeh, J. K., Au, N., Law, R. (Ayeh et al. 2013) | “Do we believe TripAdvisor?” Examining credibility perceptions and online travelers’ attitude towards using user-generated content | 2013 | Journal of Travel Research | hospitality: online reviews on TripAdvisor | the study found significant support for the impact of source credibility perceptions on attitude toward using user-generated content (UGC). This would imply that online travelers are more favorably disposed toward the use of UGC for travel planning if they believe that UGC is from credible travelers. | The study only tested the theories of homophily and source credibility to under- stand UGC use for travel planning. There are no questions about fake reviews and the sample is limited to responses from consumers in Singapore. | Future research proposed for different forms of credibility; there are other forms of credibility such as corporate credibility, message credibility, and channel credibility as well as different cultural settings. | quantitative, online survey (component-based structural equation modeling technique) |

| 6 | Baka, V. (Baka 2016) | The becoming of user-generated reviews: Looking at the past to understand the future of managing reputation in the travel sector | 2016 | Tourism Management | hospitality (online reviews—the shift from word-of-mouth (WOM) to eWOM and to user-generated content) | After the rapid growth of User- Generated-Content (UGC) in the travel sector, hotels place reputation management on the frontline of everyday organizational life. Even though TripAdvisor’s fraud detection algorithm is purported to detect fake reviews the issue of manipulation has become a problem. The paper proposes a conceptual model which takes all actors’ inputs into account, acknowledging the processual and emergent nature of reputation making. | The dynamism of UGC means that the topic is always changing and hoteliers, as well as researchers should revisit it again. | the route to reputation standing for hoteliers necessarily entails relationships to and with TripAdvisor and other eWOM websites. This is an area that needs further exploration. | qualitative, longitudinal research project designed around a case study and a netnographic approach |

| 7 | Banerjee S, Chua AY. (Banerjee and Chua 2014) | Understanding the process of writing fake online reviews | 2014 | International conference on digital information management | hospitality: fake online reviews—how they are written | 1. fake reviews are written to comprise short, catchy and succinct titles 2. written to include descriptions that contain both informative and subjective comments 3. writing fake reviews is not overly challenging 4. the process of information gathering appeared more extensive for fake positive or fake moderate reviews | This exploratory study disinterred the strategies used by Asian participants to write fake reviews for hotels within Asia. | Future research could consider investigating if the process of writing fake reviews for hotels is similar to that for products and other services (even whole destinations) | exploratory study |

| 8 | Banerjee, S. (Banerjee 2022) | Exaggeration in fake vs. authentic online reviews for luxury and budget hotels | 2022 | International Journal of Information Management | hospitality: online reviews—luxury vs. budget hotels | 1. the paper busts the myth that fake reviews are more exaggerated than authentic ones. 2. contextual idiosyncrasy created by crossing hotel category with review polarity dictated the dose of exaggeration injected in authentic and fake reviews 3. empirically confirms that individuals are more prepared to accept positive reviews for luxury hotels, and negative entries for budget properties 4. humans strengthen their online information processing vigilance under disconfirmatory contexts | the current understanding of online review authenticity still remains incomplete. the research was set in the context of hotel reviews as hotels are subjected to widespread review fraud | future research could replicate the current work by obtaining fake reviews from professionals who have experience of writing bogus entries for monetary and/or non-monetary benefits. | quantitative, data analysis (reviews gathered from 3 platforms, creating fake reviews, experimental survey on dissemination, questionnaire) |

| 9 | Berhanu, K., & Raj, S. (Berhanu and Raj 2020) | The trustworthiness of travel and tourism information sources of social media: perspectives of international tourists visiting Ethiopia | 2020 | Heliyon | tourism: truthworthiness of social media sources | The findings revealed that visitors had a positive perception towards the trustworthiness of social media travel information sources. Visitors with the age of 18–35 years have a higher level of agreement towards the trustworthiness of social media travel information sources. As the age of visitors increases, the mean scores marginally decreases where the lowest mean scores lay on visitors who are above 46 years. | Due to the nature of the study population where sampling frame of visitors is not available, mostly incidental or convenience sampling method which is non-probable was employed, and hence the issue of reprsentativeness is questionable. Only limited to Ethiopia and English-speaking visitors. | Using the method with visitors of other countries. | quantitative, Cross-sectional research to compute mean, one sample T-test, independent sample T-test and one-way Analysis of variance |

| 10 | Chatzigeorgiou, C. (Chatzigeorgiou 2017) | Modelling the impact of social media influencers on behavioural intentions of millennials: The case of tourism in rural areas in Greece | 2017 | Journal of Tourism, Heritage & Services Marketing | tourism: impact of social media influencers | Rural businesses need to use the personal relationships they develop with their customers and expand these relationships on social media. It is also apparent that traditional marketing fails to apply to small rural businesses, whereas influencer marketing becomes a valuable asset for tourism. | millennials actually trust one of their friends or someone of their age better over a famous influencer. | Further study needs to be developed in order to identify the activities that would be more attractive to millennials who are the active players through creating content and communicating images, videos or audio files. | qualitative, literature review |

| 11 | Domenico, G.D., Sit, J., Ishizaka, A., Nunan, D. (Domenico et al. 2021) | Fake news, social media and marketing: a systematic review | 2021 | Journal of Business Research | fake news in various disciplines | It identifies (1) a broad range of disciplines in which fake news has been studied, further highlighting the growing interest in this topic; (2) the unique traits or characteristics underpinning fake news, which can be used to support consumer detection of it, and (3) a collection of themes that summarise the issues that have been discussed and their interrelationships, summarised through the proposed theoretical framework. | the study focused on fake news itself (e.g dissemination of misinformation, sources, social media aspect) not on the different disciplines it may affect. Unfortunately, sources are still limited in this topic. | future research can continue this endeavour and develop a more comprehensive understanding of the topic in question. | systemiatic literature review |

| 12 | Fedeli, G. (Fedeli 2019) | Fake news’ meets tourism: a proposed research agenda | 2019 | Annals of Tourism Research | fake news in tourism | Key themes already well researched in tourism academia such as: authenticity, consumer behaviour (e.g., risk perception), marketing and crisis management in tourism certainly represent important connections to extant knowledge to help understand the issue. However, this phenomenon represents a peculiar area of study as it combines wide-ranging disciplines linked by a common underlaying issue. | Due to the novelty of the subject and its original application to the tourism domain, the use of non-academic sources (e.g., newspaper articles) was deemed valuable and incorporated to properly to address the discourse. | Ethical aspects, marketing (on micro and macro levels), impact on tourists’ perception and behaviour, security and regulations could all be possible research paths in the future | literature review |

| 13 | Filieri, R., McLeay, F. (Filieri and McLeay 2014) | E-WOM and accommodation: an analysis of the factors that influence travelers’ adoption of information from online reviews | 2014 | Journal of Travel Research | hospitality: online reviews and accommodations, decision-making | The results of this study reveal that product ranking, information accuracy, information value-added, information relevance, and information timeliness are strong predictors of travelers’ adoption of information from ORs on accommodations. These results imply that high-involvement travelers adopt both central (information quality) and peripheral (product ranking) routes when they process information from ORs. | the study does not deal with fake reviews and the effects of fake reviews on decision-making and it was composed mainly by Italian respondents, but can be a relevant source to research guest behaviour. | Further research could test the model proposed in this research on different typologies of COPs. In fact, results may differ for two typologies of COPs: independent websites (i.e., Tripadvisor.com) and e-merchants (i.e., Booking.com). E-merchants publish ORs written only by travelers who have previously purchased a product, while in an independent website travelers only need a valid email address to publish a review. | elaboration likelihood model |

| 14 | Fong, L.H.N., Ye, B.H., Leung, D., Leung, X.Y. (Fong et al. 2021) | Unmasking the imposter: do fake hotel reviewers show their faces in profile pictures | 2021 | Annals of Tourism Research | hospitality: fake online reviews—reviewers | 1. The findings which are based on an analysis of data from Yelp.com and an online experiment confirm our hypothesis that fake review writers are less likely to provide a profile picture. That means they recognize their misbehavior, and thereby refraining from providing a picture which could expose their true identity. 2. fake review writers are just as likely to use a profile picture that only shows the face of others as one without face or not providing any image at all. As such, they are probably attempting to disguise their misbehavior. | The study’s big data analytics only focuses on hotels in Las Vegas and the results may vary with different contexts. | Future research can examine other pictorial cues of fake review such as characteristics of picture, and if detectability of fake review by profile picture varies with user anonymity, review usefulness, and deepfake review. | literature review |

| 15 | Fotis, J. N., Buhalis, D., Rossides, N. (Fotis et al. 2012) | Social media use and impact during the holiday travel planning process | 2012 | Springer-Verlag | impact of social media on holiday planning process | Findings suggest that social media are predominantly used after holidays for experience sharing. It is also shown that there is a strong correlation between perceived level of influence from social media and changes made in holiday plans prior to final decisions. Moreover, it is revealed that user-generated content is perceived as more trustworthy when compared to official tourism websites, travel agents and mass media advertising. | (a) The sample is not random due to the self- response nature of the specific online panel survey; (b) there was no treatment for non-responses and the research focused on holidaymakers from the former Soviet Union states. | Future research may focus on how fake social media entries influence holiday-planners. | quantitative, online survey |

| 16 | Harris, C. (Harris 2018) | Decomposing TripAdvisor: Detecting potentially fraudulent hotel reviews in the era of big data | 2018 | International Conference on Big Knowledge | hospitality: fake/fraudulent online reviews | The word frequency between the two types of holiday planning websites (Agoda and Booking.com) and the patterns of reviewer activity differ considerably, even though the relative ranking of hotel reputation scores across review platforms are similar. | First, we examined reviews only in English and only in 12 markets. Second, we cannot verify that the suspected properties engaged in review fraud, so we can only infer fraudulent intent. Third, even among hotels with suspicious reviews, there were many genuine contributions that we did not separate from suspicious ones in our study. | Future research may look at more sophisticated review fraud; for example, how boosting and vandalism efforts may go together as a single campaign. | qualitative, longitudinal research project |

| 17 | Hlee, S., Lee, H., Koo, C., Chung, N. (Hlee et al. 2021) | Fake reviews or not: exploring the relationship between time trend and online restaurant reviews | 2021 | Telematics and Informatic | hospitality: fake restaurant reviews | The findings indicate that online reviews of newly opened restaurants show a time trend in which there are less negative sentiments and fewer words reflecting extreme reviews than long-running restaurants. | The study does not offer ways to identify products whose reviews are manipulated. This study only provides a guide to the properties of fake reviews that can be written about a newly opened restaurant. Second, some scholars may recognize certain data as a fake review, whereas others may think it is an authentic review written by a real consumer. | Future research may uncover the attributes of actual fake reviews, and study the impact of the attributes on consumers’ perceptions, review usefulness, and sales performance. | literature review, inductive approach |

| 18 | Lappas, T., Sabnis, G., Valkanas, G. (Lappas et al. 2016) | The impact of fake reviews on online visibility: a vulnerability assessment of the hotel industry | 2016 | Information Systems Research | hospitality: impact of online reviews on visibility | In certain markets, 50 fake reviews are sufficient for an attacker to surpass any of its competitors in terms of visibility. We also compare the strategy of self-injecting positive reviews with that of injecting competitors with negative reviews and find that each approach can be as much as 40% more effective than the other across different settings. | The primary limitation of the work is the absence of a large data set of injection attacks, including the fake reviews that were successfully injected, as well as those that were blocked by the attacked platform’s defenses. This is a standard limitation for research on fake reviews. | Useful kit to study online (including fake) reviews, and also empirically uncovers response strategies that may be used in the travel industry (not just hotels, but destinations as well) | estimation method |

| 19 | Long, H-D., Kong, Y-Q., Olya, H., Lee C-K., Girish, V.G. (Duong et al. 2025) | Echoes of tragedy: How negative social media shapes tourist emotions and avoidance intensions? A multi-methods approach | 2025 | Tourism Management | tourist behaviour—affected by negative social media | Empirical evidence shows that negative eWOM significantly affects tourists’ negative emotions, thus eliciting avoidance intentions towards Itaewon and crowded destinations. Furthermore, cross-country analysis indicates that tourists from China and Vietnam differ in the degree of negative emotions elicited by eWOM and the emotional strategies they employ. This research provides deep insights into the psychological mechanism underlying tourists’ negative emotions and avoidance intentions following a tragic event in a tourist destination. | The study focuses on Chinese and Vietnamese tourists. The authors does not deal with fake news, or misinformation on social media, only real tragic events that may influence tourists’ choices. | Incorporating diverse stakeholder perspectives, including destination managers, will provide a more comprehensive understanding of managing tourism destinations after tragic events. | multi-method approach (including Noldus FaceReader 7.1 AI software, in-depth interviews and a quantitative study) |

| 20 | Luca, M., Zervas, G. (Luca and Zervas 2016) | Fake it till you make it: reputation, competition, and yelp review fraud | 2016 | Management Science | hospitality: fake online restaurant reviews (by the restaurant) | First, roughly 16% of restaurant reviews on Yelp are filtered. These reviews tend to be more extreme (favorable or unfavorable) than other reviews, and the prevalence of suspicious reviews has grown significantly over time. Second, a restaurant is more likely to commit review fraud when its reputation is weak, i.e., when it has few reviews, or it has recently received bad reviews. Third, chain restaurants—which benefit less from Yelp—are also less likely to commit review fraud. Fourth, when restaurants face increased competition, they become more likely to receive unfavorable fake reviews. | - | Future research may look at how fake reviews left by businesses affect consumer’s choices | qualitative and quantitative |

| 21 | Martinez-Torres, M.R., Toral, S.L. (Martinez-Torres and Toral 2019) | A machine learning approach for the identification of the deceptive reviews in the hospitality sector using unique attributes and sentiment orientation | 2019 | Tourism Management | hospitality: machine learning approach to identify fake reviews | Positive and negative unique attributes lead to non-biased classifiers and that experience-based reviews tend to be non-deceptive. | The dataset corresponds of truthful and deceptive hotel reviews of 20 most popular Chicago hotels. They follow a review centric approach, so we do not include anything about user profiles or user networking activities. | May conduct a longitudinal study to check how the polarity-oriented unique attributes and the distinguishing topics change over time. The reason is that fraudsters can also change their patterns of action over time. The development of artificial intelligence and deep learning is making possible the artificial creation of reviews by bots or algorithms that learn from honest reviews. | content analysis |

| 22 | Mayzlin, D., Dover, Y., Chevalier, J. (Mayzlin et al. 2014) | Promotional reviews: an empirical investigation of online review manipulation | 2014 | American Economic Review | hospitality: online review manipulation | Hotels with next-door neighbors have more negative reviews on TripAdvisor, and the effect is exacerbated if the neighbor is an independent, small hotel—there is evidence of negative review manipulation. | it is not the aim of the article to contribute to the literature on fake reviews, however it does: it also suggest a detection algorithm. The limitation of the study is that it does not observe manipulation directly, but must infer it. | measuring the impact of the review manipulation on consumer behaviour | differentiation |

| 23 | Reyes-Menendez, A., Saura, J.R., Filipe, F. (Reyes-Menendez et al. 2019) | The importance of behavioral data to identify online fake reviews for tourism businesses: a systematic review | 2019 | PeerJ Computer Science | fake online reviews in the tourism sector | results demonstrate that (i) the analysis of fake reviews is interdisciplinary, ranging from Computer Science to Business and Management, (ii) the methods are based on algorithms and sentiment analysis, while other methodologies are rarely used; and (iii) the current and future state of fraudulent detection is based on emotional approaches, semantic analysis and new technologies such as Blockchain. | the number of studies reviewed and the databases consulted. Although the authors consulted the main scientific databases—Scopus, PubMed, PsyINFO, ScienceDirect and Web of Science—there are more databases available for consultation. | A promising area of future research is studying the behavioral aspects of users who write online reviews for tourism businesses. | systemiatic literature review |

| 24 | Rivera, M.A. (Rivera 2020) | Fake News and hospitality research | 2020 | International Journal of Hospitality Management | hospitality | The main goal is to initiate a discourse on matters pertaining to “fake news” that will help us rethink and inquire what constitutes knowledge in order to better understand the past, present, and future of hospitality research. | - | - | - |

| 25 | Tham, A., Chen, Sh. (Tham and Chen 2022) | Fake News and Tourism—Whose Responsibility Is It? | 2022 | Journal of Responsible tourism management | fake news in tourism | Participant scores ranged from 1 to 6 out of 10 in terms of correctly picking out real news from fake news. Several participants commented that it was challenging and confusing to detect fake news from real information because each of these appeared somewhat authentic, except for those that they felt were likely exaggerating, or hardly possible. | As an exploratory investigation, the outcomes of the fake news tourism experiment may not be generalizable across different contexts, such as students or leisure travelers. | Future studies may wish to investigate fake news in other contexts, such as hospitality or events. | literature review and fake news experiment among conference participants |

| 26 | Tuomi, A. (Tuomi 2021) | Deepfake consumer reviews in tourism: Preliminary findings | 2021 | Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights | hospitality: deepfake (computer-generated) reviews | the paper provides tourism scholars preliminary insight into how deepfake online reviews influence tourism management, including the kinds of features that make a given narrative particularly “human- or machine-like”. | only preliminary studies | Future research should continue this line of inquiry by exploring strategies for detecting, moderating, and replying to computer-generated reviews in tourism. In particular, attention should be paid to exploring impacts of computer-generated reviews across different review platforms. | qualitative analysis (descriptive) |

| 27 | Vasist, P.N., & Krishnan, S. (Vasist and Krishnan 2023) | Disinformation ‘gatecrashes’ tourism: An empirical study | 2023 | Annals of Tourism Research | tourism: political disinformation | The study finds that there is influence of various forms of disinformation on the performance of the travel and tourism sector, the study reveals the complexity of disinformation as a phenomenon and provides crucial insights for researchers weighing their options for evaluating the influence of particular disinformation aspects on the travel and tourism sector. | Focuses exclusively on political disinformation and its consequences on tourism | Future studies may incorporate a range of fake news genres and examine their effects on travel and tourism. | qualitative, comparative analysis |

| 28 | Vasist, P.N., & Krishnan, S. (Vasist and Krishnan 2024) | Country branding in post-truth Era: A configural narrative | 2024 | Journal of Destination Marketing & Management | tourism: impact of online disinformation and hate speech on a country’s image | increasing dominance of state and partisan factions-led disinformation, which collectively impact the nation’s image. The findings also shed light on the diminishing role of foreign disinformation, while the ancillary function of online hate emphasizes the significance of disinformation amplified hate speech, which has become increasingly commonplace in global political discourse, with such disinformation campaigns using hate speech as an amplification strategy. | the analysis incorporates secondary data from credible sources, and the impact of hate speech and disinformation on a country’s image was empirically validated, it is possible that a nation’s poor brand image may become a target for disinformation campaigns and foreign interference. | future research can consider gathering primary data and analyzing the precise consequences of disinformation and its influence on regional perceptions of a nation’s brand | configurational analysis |

| 29 | Vasist, P.N., & Krishnan, S. (Vasist and Krishnan 2022) | Demystifying fake news in the hospitality industry: A systematic literature review, framework, and an agenda for future research | 2022 | International Journal of Hospitality Management | hospitality and food industry, focusing on fake reviews | Four broad themes characterizes the research on fake news in the hospitality industry: 1. Fake reviews may be tools for inducing an epistemic crisis 2. Food facts, fads, and myths may be vehicles of fake news 3. Health scares may impact hotels and restaurants 4. There are deceptive narratives in travel and recreation | The implications of engaging with content of a false nature may be explored at the levels of individual, brand, and the society. | qualitative, systematic literature review | |

| 30 | Vidriales, A. L. (Vidriales 2020) | Fake news or real: Analysis of the impact of travel alerts in Mexico’s sun and sea main tourist destinations | 2020 | Journal of Travel, Tourism and Recreation | tourism:fake news case study (mexico) | US travel alerts of increased violence, insecurity and crime cause the decrease flows of American tourists to main Mexico’s sun and sea tourist destinations, as consequence, the local population might be affected for all the lack of income. | only deals with one part of Mexico and US citizens | Other studies may look into other destinations (where the US issued travel alerts) | documental/statistical data analysis |

| 31 | Wang, Y., Chan, S.C., Leong, H.V., Ngai, G., Au, N. (Wang et al. 2016) | Multi-dimension reviewer credibility quantification across diverse travel communities | 2016 | Knowledge and Information Systems | tourism: reviewer credibility | The study shows that both Impact Index and Exposure-Impact Index lead to more consistent results with human judgments than the state-of-the-art method in measuring the credibility of reviewers from diverse communities, manifesting their effectiveness and applicability. | Qunar is less known in Europe, so it is only relevant in the context of the Asian/Chinese travel community | Future studies may examine the impact of adjusting the weight of two dimensions to satisfy travellers’ different demands. | adopts Impact and Exposure-Impact Index to quantify the credibility of reviewers |

| 32 | Williams, N. L., Wassler, P., & Ferdinand, N. (Williams et al. 2022) | Tourism and the COVID- (Mis)infodemic | 2022 | Journal of Travel Research | tourism: misinformation about the pandemic | As a “misinfodemic,” COVID-19 discussions have also attracted actors seeking to share misinformation enabled and exacerbated by social media networks, which include willful distortions as well as conspiracy theories. Combined, this (mis)infodemic can change risk perceptions of travel, resulting in travel patterns based on technological, regulatory, and perceived behavioral homophily. | it is dealing with misinformation about covid-19, which is not relevant at the moment, however, may shed light to the inner workings of misinformation about pandemics and natural disasters | gateway for future tourism research that incorporates the discussed concepts (conspiracy theories, vaccine hesitancy) as part of theoretical frameworks to examine travel behaviour as described in this study. | literature review |

| 33 | Wu, Y., Ngai, E.W.T., Wu, P., Wu, C. (Wu et al. 2020) | Fake online reviews: literature review, synthesis, and directions for future research | 2020 | Decision Support Systems | fake online reviews | Based on a review of the extant literature on the issue, the study identifies 20 future research questions and suggest 18 propositions. Notably, research on fake reviews is often limited by lack of high-quality datasets. To alleviate this problem, the study comprehensively compile and summarize the existing fake reviews-related public datasets. | The literature review is not exhaustive, but it can be a beneficial resource for future research, as it highlights possible research directions | 20 future research Q’s and 18 propositions | literature review (antecedent–consequence–intervention conceptual framework) |

| 34 | Ye, Q., Law, R., Gu, B. (Ye et al. 2009) | The impact of online user reviews on hotel room sales | 2009 | International Journal of Hospitality Management | hospitality: impact of online reviews on room sales | The result showed that positive online reviews can significantly increase the number of bookings in a hotel, and the variance or polarity of WOM for the reviews of a hotel had a negative impact on the amount of online sales. Additionally, hotels with higher star ratings received more online bookings, but room rates had a negative impact on the number of online bookings. Furthermore, the GDP of the host city had a positive impact on the number of online bookings. | studies the largest travel website in China | Future research, such as the refinement of the evaluation model, is needed to improve the generalization of research findings in this area. | fixed effect log-linear regression model |

| 35 | Zelenka, J., Azubuike, T., Pásková, M. (Zelenka et al. 2021) | Trust model for online reviews of tourism services and evaluation of destinations | 2021 | Administrative Sciences | hospitality (online hotel reviews) | In the early days of Web 2.0, studies focusing tourism services offered in destinations. In the early days of Web 2.0, studies focusing on user trust in UGC, as well as comparing trust in UGC and CGC and the factors that user trust in UGC, as well as comparing trust in UGC and CGC and the factors that influence that trust, were published. This trust is significantly influenced by the evaluation of the level of truth and intentional cognitive or emotional distortion of UGC content, and this is even more true of e-WOM, including reviews of tourism services and destination ratings. | When using review sites as a source of information in marketing research, the systematic use of a false input filter can be expected. | Further research into various aspects of false communications in tourism can also be expected, e.g., to examine the ethics, marketing, perception and behaviour of tourism participants, as well as safety and regulation. | SWOT analysis, processual analysis and an analysis of verification process, conditions, factors affecting trust in reviews on review sites. |

| 36 | Zeng, B., & Gerritsen, R. (Zeng and Gerritsen 2014) | What do we know about social media in tourism? A review | 2014 | Tourism management perspective | tourism: social media | The paper suggests that research on social media in tourism is still in its infancy. It is critical to encourage comprehensive investigation into the influence and impact of social media (as part of tourism management/marketing strategy) on all aspects of the tourism industry including local communities, and to demonstrate the economic contribution of social media to the industry. | This review did not include social media sources in the literature, such as blogs, micro-blogs, Facebook, and Twitter. | Social media in tourism research will have to deal with the issues associated with local communities such as socio-economic and cultural impacts (either positive or negative) of social media on local residents. | literature review |

| 37 | Zhang, D., Zhou, L., Kehoe, J.L., Kilic, I.Y. (Zhang et al. 2016) | What online reviewer behaviors really matter? Effects of verbal and nonverbal behaviors on detection of fake online reviews | 2016 | Journal of Management Information Systems | hospitality: fake online reviews—detection | The results of an empirical evaluation using real-world online reviews reveal that incorporating nonverbal features of reviewers can significantly improve the performance of online fake review detection models. Moreover, com- pared with verbal features, nonverbal features of reviewers are shown to be more important for fake review detection. Furthermore, model pruning based on a sensitivity analysis improves the parsimony of the developed fake review detection model without sacrificing its performance. | Detecting online fake reviews is a challenging task. Fabricating a fake review is essentially a deception process. Extensive deception studies have shown that the accuracy of human deception detection is only slightly higher than 50 percent, primarily due to people’s truth bias and misuse of telltale signs of deception. | The findings provide several research and practical implications for improving the trustworthiness of online review platforms and the performance of online fake review detection. | review content analysis and feature extraction using the Natural Language ToolKit (NLTK 3.0) |

| 38 | Johnson, A.G. (Johnson 2024) | Fake news simulated performance: gazing and performing to reinforce negative destination stereotypes | 2024 | Tourism Geographies | fake news in tourism | The study draws attention to the spatiality of the phenomenon, which can provide practitioners with insights for developing and implementing destination image repair strategies. Practitioners should incorporate gazers into their strategies for com- batting stereotypes. They also need to carry out continuous and real-time repair alongside bunking strategies prior to and during performances. Debunking strategies should provide contextual data in order to be effective. | The study mainly deals with the proposal that fake news has emerged as hyperreality performances that serve as a means of reinforcing negative stereotypes for destinations with populations of African descent, thus only deals with relevant destinations. | Explorations can extend beyond tourism as fake news that reinforce stereotypes towards individuals of African descent is being confronted in international relations and crisis research. | literature review, case studies |

| 39 | Mushawemhuka, W., Hoogendoorn, G., M. Fitchett, J. (Mushawemhuka et al. 2021) | Implications of Misleading News Reporting on Tourism at the Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe | 2021 | American Meteorological Society | tourism in general | Inaccurate reporting is argued by the tourism operators to have negatively affected the tourism sector and destination image of the key attraction. This paper highlights the need for accurate science-based media reporting on weather, climate, climate change, and the knowledge of the local tourism stakeholders within the tourism sector. | Not all newspaper articles who mentioned about the Victoria falls were considered in this research. | Accurate high-resolution data could be applied in future research to limit the impacts of fake media on the tourist destination. | content analysis |

References

- Abdallah, Ali. 2021. Fake news, false advertising, social media, and the tourism industry. International Journal of Development Research 11: 48999–9003. [Google Scholar]

- Abedin, Ehsan, Antonette Mendoza, and Shanika Karunasekera. 2020. Credible vs. Fake: A Literature Review on Differentiating Online Reviews Based on Credibility. Paper presented at the International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2020)—Making Digital Inclusive: Blending the Local and the Global, Hyerabad, India, December 13–16; Available online: https://arc.net/l/quote/wdbcyvck (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Abu Arqoub, Omar, Adeola Abdulateef Elega, Bahire Efe Özad, Hanadi Dwikat, and Felix Adedamola Oloyede. 2020. Mapping the Scholarship of Fake News Research: A Systematic Review. Journalism Practice 16: 56–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Wasim, and Jin Sun. 2018. Modeling consumer distrust of online hotel reviews. International Journal of Hospitality Management 71: 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, Emanuela, Cosmin Alexandru Teodorescu, and Vanesa Madalina Vargas. 2020. Perspectives and reviews in the use of narrative strategies for communicating fake news in the tourism industry. Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Excellence 14: 728–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoun Barakat, Karine, Amal Dabbous, and Abbas Tarhini. 2021. An empirical approach to understanding users’ fake news identification on social media. Online Information Review 45: 1080–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arin, K. Peren, Deni Mazrekaj, and Marcel Thum. 2023. Ability of detecting and willingness to share fake news. Scientific Reports 13: 7298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayeh, Julian K., Norman Au, and Rob Law. 2013. Do we believe TripAdvisor? Examining credibility perceptions and online travelers’ attitude towards using user-generated content. Journal of Travel Research 52: 437–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, Saumya Tripathi, and Dilip Kumar Sharma. 2021. Fake News Propagation in the era of Covid-19-Tracing and Combating Fake News using Block Chain Technology. Paper presented at the 2021 International Conference on Simulation, Automation & Smart Manufacturing (SASM), Mathura, India, August 20–21; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baka, Vasiliki. 2016. The becoming of user-generated reviews: Looking at the past to understand the future of managing reputation in the travel sector. Tourism Management 53: 148–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, Brian. 2021. Defeating Fake News: On Journalism, Knowledge, and Democracy. Moral Philosophy and Politics 8: 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, Snehasish. 2022. Exaggeration in Fake vs. Authentic Online Reviews for Luxury and Budget Hotels. International Journal of Information Management 62: 102416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, Snehasish, and Alton Yeow-Kuan Chua. 2014. Understanding the process of writing fake online reviews. Paper presented at the Ninth International Conference on Digital Information Management (ICDIM 2014), Phitsanulok, Thailand, September 29–October 1; Piscataway: IEEE, pp. 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhanu, Kessagn, and Sahil Raj. 2020. The trustworthiness of travel and tourism information sources of social media: Perspectives of international tourists visiting Ethiopia. Heliyon 6: e03439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braşoveanu, Adrian M. P., and Răzvan Andonie. 2021. Integrating Machine Learning Techniques in Semantic Fake News Detection. Neural Processing Letters 53: 3055–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broda, Elena, and Jesper Strömbäck. 2024. Misinformation, Disinformation, and Fake News: Lessons from an Interdisciplinary, Systematic Literature Review. Annals of the International Communication Association 48: 139–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzigeorgiou, Chryssoula. 2017. Modelling the impact of social media influencers on behavioural intentions of millennials: The case of tourism in rural areas in Greece. Tourismos: An International Multidisciplinary Journal of Tourism 12: 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damstra, Alyt, Hajo G. Boomgaarden, Elena Broda, Elina Lindgren, Jesper Strömbäck, Yariv Tsfati, and Rens Vliegenthart. 2021. What Does Fake Look Like? A Review of the Literature on Intentional Deception in the News and on Social Media. Journalism Studies 22: 1947–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Domenico, Giandomenico, Jason Sit, Alessio Ishizaka, and Daniel Nunan. 2021. Fake news, social media and marketing: A systematic review. Journal of Business Research 124: 329–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, Long Hai, Yuan-Qi Kong, Hossein Olya, Choong-Ki Lee, and V. G. Girish. 2025. Echoes of tragedy: How negative social media shapes tourist emotions and avoidance intentions? A multi-methods approach. Tourism Management 108: 105122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecker, Ulrich K. H., Stephan Lewandowsky, John Cook, Philipp Schmid, Lisa K. Fazio, Nadia M. Brashier, Panayiota Kendeou, Emily K. Vraga, and Michelle A. Amazeen. 2022. The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nature Reviews Psychology 1: 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedeli, Giancarlo. 2019. ‘Fake news’ meets Tourism: A proposed research agenda. Annals of Tourism Research 80: 102684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, Raffaele, and Fraser McLeay. 2014. E-WOM and accommodation: An analysis of the factors that influence travelers’ adoption of information from online reviews. Journal of Travel Research 53: 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, Lawrence Hoc Nang, Ben Haobin Ye, Daniel Leung, and Xi Yu Leung. 2021. Unmasking the imposter: Do fake hotel reviewers show their faces in profile pictures? Annals of Tourism Research 88: 103321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotis, John, Dimitrios Buhalis, and Nicos Rossides. 2012. Social Media Use and Impact during the Holiday Travel Planning Process. Paper presented at the Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2012, International Conference, Helsingborg, Sweden, January 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Christopher. 2018. Decomposing TripAdvisor: Detecting potentially fraudulent hotel reviews in the era of big data. Paper presented at the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Big Knowledge (ICBK), Singapore, November 17–18; Piscataway: IEEE, pp. 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlee, Sunyoung, Hyunae Lee, Chulmo Koo, and Namho Chung. 2021. Fake reviews or not: Exploring the relationship between time trend and online restaurant reviews. Telematics and Informatics 59: 101560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Sumaiya, Marie Hattingh, and Machdel Matthee. 2024. Understanding the Challenges of Fake News in the Tourism and Travel Industry: A Systematic Literature Review. Paper presented at the Disruptive Innovation in a Digitally Connected Healthy World: 23rd IFIP WG 6.11 Conference on E-Business, E-Services and E-Society, I3E 2024, Heerlen, The Netherlands, September 11–13; Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 371–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Abbie-GayleG. 2024. Fake news simulated performance: Gazing and performing to reinforce negative destination stereotypes. Tourism Geographies 26: 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappas, Theodoros, Gaurav Sabnis, and Georgios Valkanas. 2016. The impact of fake reviews on online visibility: A vulnerability assessment of the hotel industry. Information Systems Research 27: 940–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, M. Asher, and Hemant Kakkar. 2022. Of pandemics, politics, and personality: The role of conscientiousness and political ideology in the sharing of fake news. Journal of experimental psychology. General 151: 1154–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazer, David M. J., Matthew A. Baum, Yochai Benkler, Adam J. Berinsky, Kelly M. Greenhill, Filippo Menczer, Miriam J. Metzger, Brendan Nyhan, Gordon Pennycook, David Rothschild, and et al. 2018. The science of fake news. Science 359: 1094–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeder, Chris. 2019. How college students evaluate and share “fake news” stories. Library & Information Science Research 41: 100967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, Michael, and Georgios Zervas. 2016. Fake it till you make it: Reputation, competition, and Yelp review fraud. Management Science 62: 3412–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Torres, Rocio, and Sergio L. Toral. 2019. A machine learning approach for the identification of the deceptive reviews in the hospitality sector using unique attributes and sentiment orientation. Tourism Management 75: 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayzlin, Dina, Yaniv Dover, and Judith Chevalier. 2014. Promotional reviews: An empirical investigation of online review manipulation. American Economic Review 104: 2421–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushawemhuka, William, Gijsbert Hoogendoorn, and Jennifer M. Fitchett. 2021. Implications of misleading news reporting on tourism at the Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 102: E1011–E1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372: n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paskin, Danny. 2018. Real or Fake News: A Lesson Plan to Teach Students to Analyze the Reliability of News Sources. Communication Teacher. The Journal of Social Media in Society Fall 7: 252–73. Available online: https://thejsms.org/index.php/JSMS/article/view/386 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Pennycook, Gordon, Adam Bear, Evan T. Collins, and David G. Rand. 2020. The Implied Truth Effect: Attaching Warnings to a Subset of Fake News Headlines Increases Perceived Accuracy of Headlines Without Warnings. Management Science 66: 4944–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Menendez, Ana, Jose Ramon Saura, and Ferrão Filipe. 2019. The importance of behavioral data to identify online fake reviews for tourism businesses: A systematic review. PeerJ Computer Science 5: e219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, Manuel A. 2020. Fake news and hospitality research. International Journal of Hospitality Management 85: 102473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Bee Lian, Chee Yoong Liew, Jye Ying Sia, and Kanesh Gopal. 2021. Electronic word-of-mouth in travel social networking sites and young consumers’ purchase intentions: An extended information adoption model. Young Consumers 22: 521–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, Bruno Barbosa, Marina Silva, and Claúdia Miranda Veloso. 2020. The Quality of Communication and Fake News in Tourism: A Segmented Perspective. Quality 21: 101–5. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343546439_The_Quality_of_Communication_and_Fake_News_in_Tourism_A_Segmented_Perspective (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Tandoc, Edson C., Zheng Wei Lim, and Richard Ling. 2017. Defining “Fake News”: A typology of scholarly definitions. Digital Journalism 6: 137–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, Aaron, and Shu-Hsiang Chen. 2022. Fake news and tourism—Whose responsibility is it? Journal of Responsible Tourism Management 2: 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomi, Aarni. 2021. Deepfake consumer reviews in tourism: Preliminary findings. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights 2: 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasist, Pramukh Nanjundaswamy, and Satish Krishnan. 2022. Demystifying fake news in the hospitality industry: A systematic literature review, framework, and an agenda for future research. International Journal of Hospitality Management 106: 103277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasist, Pramukh Nanjundaswamy, and Satish Krishnan. 2023. Disinformation ‘gatecrashes’ tourism: An empirical study. Annals of Tourism Research 101: 10375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasist, Pramukh Nanjundaswamy, and Satish Krishnan. 2024. Country branding in the post-truth era: A configural narrative. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 32: 100854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidriales, Arturo Laure. 2020. Fake news or real: Analysis of the impact of travel alerts in Mexico’s sun and sea main tourist destinations. Journal of Travel, Tourism and Recreation 2: 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosoughi, Soroush, Deb Roy, and Sinan Aral. 2018. The spread of true and false news online. Science 359: 1146–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yuanyuan, Stephen Chi Fai Chan, Hong Va Leong, Grace Ngai, and Norman Au. 2016. Multi-dimension reviewer credibility quantification across diverse travel communities. Knowledge and Information Systems 49: 1071–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Nigel L., Phillipp Wassler, and Nicole Ferdinand. 2022. Tourism and the COVID-(Mis)infodemic. Journal of Travel Research 61: 214–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Yuanyuan, Eric W. T. Ngai, Pengkun Wu, and Chong Wu. 2020. Fake online reviews: Literature review, synthesis, and directions for future research. Decision Support Systems 132: 113280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Qiang, Rob Law, and Bin Gu. 2009. The impact of online user reviews on hotel room sales. International Journal of Hospitality Management 28: 180–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelenka, Josef, Tracy Azubuike, and Martina Pásková. 2021. Trust model for online reviews of tourism services and evaluation of destinations. Administrative Sciences 11: 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Benxiang, and Rolf Gerritsen. 2014. What do we know about social media in tourism? A review. Tourism Management Perspectives 10: 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Dongsong, Lina Zhou, Juan Luo Kehoe, and Isil Doga Kilic. 2016. What online reviewer behaviors really matter? Effects of verbal and nonverbal behaviors on detection of fake online reviews. Journal of Management Information Systems 33: 456–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Available in full text | Full text unavailable electronically |

| Published between 2000 and 2024 | Outside of the 2000–2024 timeframe |

| Written in English | Written in other languages than English |

| Related to the research topic (communication, fake news and tourism) | Vaguely or not related to the research topic |

| Published in the three selected databases (Web of Science, Google Scholar and Scopus) | Research without the description of data sources and methodology |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaszás, F.; Supeková, S.C.; Keklak, R. Fake News in Tourism: A Systematic Literature Review. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080454

Kaszás F, Supeková SC, Keklak R. Fake News in Tourism: A Systematic Literature Review. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(8):454. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080454

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaszás, Fanni, Soňa Chovanová Supeková, and Richard Keklak. 2025. "Fake News in Tourism: A Systematic Literature Review" Social Sciences 14, no. 8: 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080454

APA StyleKaszás, F., Supeková, S. C., & Keklak, R. (2025). Fake News in Tourism: A Systematic Literature Review. Social Sciences, 14(8), 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080454