1. Background

Violent conflict across African countries has had far-reaching implications for youth development, particularly concerning education and employment transitions. Approximately 120,000 children ranging in age from 7 to 18 have participated in violent conflicts on the continent both as victims and perpetrators in the last decade (

Tar et al. 2021). For example, in Uganda, the rebel groups the Allied Democratic Force (ADF), the Uganda People’s Army (UPA), and the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) have orchestrated violent conflicts in western, eastern, and northern Uganda, respectively, since the 1980s (

Gersony 1997;

Titeca and Vlassenroot 2012). In Sierra Leone and Liberia, the rebel groups the Revolutionary United Front (RUF: 1991 to 2002) and the National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL: 1989 to 1997), respectively, enlisted thousands of children in their ranks, unleashing widespread and systemic disruptions (

Brownell et al. 2020). While these historical accounts offer essential context, they also highlight a pressing developmental gap in reintegration programmes. Often, the reintegration programmes rarely exceed surface-level technical and vocational training to address deeper psychological, agency-based barriers and the local economy that are vital for improving the education-to-work transition.

In post-conflict regions such as the Great Lakes, Sahel, and West Africa, war-affected youths encounter multiple challenges in reintegration, relevant education and training, and performance in employment (

Blanchet-Cohen et al. 2017;

Brownell et al. 2020;

Ibrahim 2023;

Matsumoto 2008). For example, in the Great Lake region that covers 10 countries (Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia), significant mental health problems and a lack of knowledge of available mental health services abound. Despite the proliferation of post-conflict recovery initiatives, reintegration into formal education and employment remains an elusive goal or is poorly implemented. In northern Uganda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and South Sudan, young people continue to struggle with mental health problems, interrupted schooling, minimal skills training opportunities, and persistent employment barriers. For example, between 2020 and 2021, 66% of the youth reported symptoms of depression, and 40% lacked knowledge of available mental health services (

Wipfli et al. 2023). These figures emphasise the critical need for mental health and psychosocial support in the education-to-work transition. While material and structural reintegration frameworks exist, the psychosocial dimension remains insufficiently theorised, supported, or even understood.

The transition from education to employment is not merely procedural; it is also profoundly psychological, especially for individuals exposed to trauma, displacement, and prolonged insecurity. Mental health problems such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) act as silent disruptors, curtailing young people’s ability to acquire, retain, and thrive in jobs (

Wipfli et al. 2023). In the workplace, these mental health problems manifest as low self-esteem, apathy, behavioural problems, poor coping skills, impaired social relationships, and dysfunction (

Kahn and Lundgren-Resenterra 2021;

Newnham et al. 2015;

Wipfli et al. 2023;

Woldetsadik 2017;

Cieslik et al. 2022;

Ripamonti 2023;

Williams 2021). In addition to limiting war-affected youth’s career prospects, mental health problems, social dysfunction, and performance difficulties also impede job retention and professional development (

Betancourt et al. 2014;

Blanchet-Cohen et al. 2017;

Fortune 2021;

Ibrahim 2023).

Furthermore, the long-term impact of exposure to violent conflict has a cumulative and debilitating effect on the mental health and social functioning of the war-affected youth (

Kahn and Lundgren-Resenterra 2021;

Newnham et al. 2015;

Wipfli et al. 2023;

Woldetsadik 2017). Not only do these youth experience diminished career aspirations and reduced goal orientation, but the performance issues that stem from poor mental well-being also inhibit job retention and growth (

Cieslik et al. 2022). Yet, mainstream skills development initiatives continue to operate under the assumption that technical competence alone is sufficient for workforce integration, neglecting individual agency, mental and psychosocial support, social and life skills, and market forces that are equally vital for education-to-work transition.

Youth employability in post-conflict settings presents a significant developmental challenge, necessitating a comprehensive examination of the factors influencing their employability. Also, systemic barriers and socio-economic complexities, such as disrupted education systems, entrenched poverty, and weakened institutional frameworks, exacerbate youth unemployment (e.g., irrelevant curriculum, unemployment, underemployment, infrastructure not fit for purpose, inability to keep a job, and an unresponsive and irresponsible workplace) (

Apunyo et al. 2022;

Bbaale et al. 2023;

Cieslik et al. 2022;

Fox et al. 2016). The resulting educational discontinuities leave young people with poor academic outcomes and few marketable skills (

Mallett et al. 2016). Compounding this, stigma, familial rejection, and marginalisation further alienate youth from community-based support systems and job networks (

Woldetsadik 2017). While there are efforts to redress these issues, an integrated approach is still lacking. Similarly, governments and NGOs have introduced vocational training in trades like carpentry, tailoring, and mechanics to equip youth with marketable skills and promote economic participation (

Amone-P’Olak et al. 2016;

Kitambo 2021;

Williams 2021), but without other factors to facilitate the skills. This review therefore departs from previous descriptive accounts of post-conflict skilling programmes by positioning individual agency (motivation, aspirations, intentionality) and mental health and psychosocial well-being as foundational, which are often the missing components in existing interventions to reintegrate war-affected youths.

Reintegration is the process of supporting and empowering individuals formerly associated with armed forces or groups to return to civilian life and participate fully and thrive in their families and communities (

Honwana 2017). In this review about reintegration, the successes and challenges of reintegration are examined to help develop a more complete picture regarding the gaps in interventions, the challenges associated with the education-to-work transition, and the nexus with different stakeholders in Sub-Saharan Africa. The review will discuss the interplay among individual agency, mental health, and employability factors, with a focus on informing interventions to meet the unique needs and contexts of war-affected populations in Sub-Saharan Africa. Furthermore, this review will propose establishing a participatory action research agenda to better understand education-to-work transition issues.

Furthermore, this review aims to synthesise current debates and theoretical frameworks on education-to-work transitions among youth in post-conflict Sub-Saharan Africa. To support this discussion, we conducted a rapid scoping review of the literature published between 1982 and 2024. The search drew from databases such as Google Scholar, PubMed, Scopus, and ERIC, using combinations of keywords like “post-conflict youth,” “education-to-work transition,” “youth employability”, “mental health,” “self-efficacy,” and “individual and or personal agency.” Both the peer-reviewed and grey literature, including reports from organisations providing professional skilling programmes to youths in post-conflict settings, were reviewed. Studies were included if they focused on youths in post-conflict Sub-Saharan Africa and addressed themes such as employability, mental health, or individual/personal agency. We considered only publications offering empirical, theoretical, or programmatic insights into education-to-work transitions. Studies were excluded if they focused solely on non-conflict settings, lacked relevance to youth transitions, or did not align methodologically with the aims of this review.

Reimagining education-to-work skilling programmes includes addressing mental health and personal agency and two critical but often neglected aspects in intervention for war-affected youth, all nested within the local economic and market realities. This review is divided into four parts. The first two parts examine the roles of individual agency, mental health, and psychosocial well-being in education-to-work transition. This is followed by a discussion of the implications of individual agency and mental and psychosocial well-being. Thereafter, we propose an integrated model of reintegrating war-affected and vulnerable youths in Sub-Saharan Africa. Finally, the review concludes with a discussion of the way forward.

2. Individual Agency in Education-to-Employment Transition

Individual agency refers to the capacity of an individual to make purposeful choices and act on them to influence their life outcomes (

Thoits 2006). It encompasses cognitive, emotional, and behavioural dimensions that enable individuals to navigate opportunities and constraints in their environment (

Thoits 2006;

Wessells 2021). In post-conflict settings, where displacement, trauma, and social instability are prevalent, personal agency is especially critical for young people transitioning from education to work.

This review is centred on Albert Bandura’s Self-Efficacy Theory (SET) to establish a framework for evaluating the development of agency. According to SET, self-efficacy—a person’s belief in their ability to execute the actions required to achieve desired outcomes—plays a pivotal role in shaping motivation, goal setting, and resilience (

Bandura 1997). These beliefs are built through four interrelated processes: mastery of experiences, vicarious learning, verbal persuasion, and the interpretation of emotional and physiological states. In contexts of adversity, such as those faced by war-affected youth, the processes of self-efficacy may be disrupted, thereby diminishing the sense of control needed to pursue employment pathways. However, the Cumulative Stress Hypothesis (CSH) reiterates that prolonged exposure to conflict-related stress not only undermines the psychological resources necessary for agency to emerge and thrive but also affects skills training and employability.

Employability is typically defined as the capacity of an individual to secure and maintain meaningful work (

Kahn and Lundgren-Resenterra 2021). Employability is shaped by a combination of technical skills, behavioural competencies, attitudes, and knowledge of labour market dynamics (

McGrath 2022;

Tight 2023). However, Forrier and colleagues (2018) caution against viewing employability solely as an individual asset. They critique the dominant narrative that assumes that employability is entirely self-managed, universally beneficial, and detached from institutional or social structures. Instead, they propose a relational and contextual model of employability, one that is influenced by labour market opportunities, network access, and organisational support. For war-affected youth, whose ability for independent action is influenced by both institutional and structural limitations in addition to emotional, behavioural, and individual effort, this more comprehensive perspective is especially pertinent.

While fostering individual agency remains essential, a narrow focus on self-direction risks ignoring the real effects of trauma, poverty, and institutional breakdown is counterproductive. Therefore, Forrier and colleagues (2018) urge researchers and practitioners to recognise that employability in disadvantaged and vulnerable contexts requires attention to both individual capacities and the environments that enable or inhibit their realisation. In Sub-Saharan Africa, systemic barriers like limited vocational training opportunities, a curriculum not fit for purpose in the current labour market, and a lack of access to formal employment disproportionately impact employability (

Apunyo et al. 2022). Understanding these dynamics helps to illuminate how individual agency interacts with broader structural factors to shape employment outcomes.

Post-conflict regions in Sub-Saharan Africa face compounded challenges, including disrupted education systems, weakened institutional frameworks, and heightened youth vulnerability. Previous studies have examined how structural inequities, such as limited institutional capacity and inadequate infrastructure, exacerbate these challenges in post-conflict settings (

Chakravarty et al. 2017;

Bbaale et al. 2023). In addition, according to Apunyo and colleagues (2022), skill-building programmes help young people develop a sense of control over their lives, build confidence, and empower them to make decisions and solve problems effectively. Employment helps war-affected youth recover by mitigating their susceptibility to further violence, which, in turn, fosters post-war stability and peace (

Betancourt et al. 2020;

Newnham et al. 2015). Equally, employment benefits the youth who have experienced violent conflicts to have greater self-efficacy, enhanced self-worth, and improved social capital (

Angucia et al. 2010;

Amone-P’Olak 2020). Moreover, employment builds in the youth the capacity to contribute to their community and to develop societal values and play their citizenship roles in society (

Angucia et al. 2010;

Amone-P’Olak 2020;

Newnham et al. 2015). For instance, the government of Uganda, through public–private partnerships, has actively engaged organisations such as the Private Sector Foundation Uganda (PSFU) and ENABEL, the Belgian Federal Development Agency, to support initiatives like the Work Readiness Programme, aimed at boosting employability among the youth (

Okitela 2024). However, while these programmes focus on skill-building and employability, they often neglect critical aspects such as fostering individual agency and providing mental and psychosocial support to beneficiaries. In an evaluation of both PSFU and ENABEL,

Okitela (

2024) outlined the gaps and challenges faced by the organisations. These include insufficient funding and resources allocated specifically for mental health and psychosocial support, limited expertise or trained personnel in mental health fields, and the difficulty of integrating these components into existing programmes. Additionally, stigmas surrounding mental health and the lack of adequate policies supporting psychosocial well-being in post-conflict settings may further complicate efforts to address these issues. To maximise the impact of such initiatives, it is imperative to design programmes that explicitly integrate mental health and individual agency alongside skill-building programmes.

A similar project in Liberia, the USAID Youth Advance Project, focused on increasing the economic self-reliance and resiliency of Liberian youth. In this project, only basic education and vocational skills were incorporated into an education-to-work programme (

Enria 2014). In addition, the youth were trained in entrepreneurship and enrolled in a micro-credit scheme to start an enterprise. Although individual agency may emerge through entrepreneurial initiatives, adaptive career strategies, and the pursuit of skills enhancement, individual agency, mental health, and psychosocial support were not included in the programme. Forrier and colleagues (2018) emphasise the dual dimensions of agency and adaptability, underlining the importance of active career management. For example,

Kahn and Lundgren-Resenterra (

2023) frame employability as a capacity for agency shaped by education, social structures, and individual aspirations. Furthermore, employability and individual agency share a circular relationship: positive individual agency can enhance employability, while securing employment can, in turn, foster greater individual agency by building confidence and enabling further skill development (

Clancy and Holford 2023;

Tholen 2015). Consequently, there is a need to understand employability not as a static outcome but as a dynamic process where individual agency and employment reinforce each other over time (

Kahn and Lundgren-Resenterra 2021).

Systemic barriers, including limited access to financial resources, entrenched gender disparities, institutional inefficiencies, and the lack of human resources in mental health and psychosocial fields, significantly constrain the realisation of agency in post-conflict regions. Likewise, entrenched gender disparities often manifest in structural inequities that disproportionately impede young women’s employment prospects, as

Chakravarty et al. (

2017) highlight in their discussion of gendered dimensions of employability. For example, unemployment rates for female youth are higher, and they work in more vulnerable employment than their male counterparts (

Chakravarty et al. 2017). Despite ongoing efforts to rebuild human capital through post-conflict skilling programmes, significant gender disparities remain (

Hilker and Fraser 2009). In many Sub-Saharan African contexts, young women face disproportionate barriers to employment, including gender-based violence, early marriage, limited access to education, and confinement to traditional female roles such as caregiving (

Mazurana and Cole 2013). While some initiatives have introduced vocational training in non-traditional trades and psychosocial support for female youth, these programmes remain limited in scope and scale (

Annan et al. 2011).

The absence of dedicated mental health and psychosocial activities in the planning processes of programmes like PSFU or ENABEL, alluded to above, further undermines efforts to support individual empowerment. Moreover, excluding mental health and psychosocial activities from education-to-work programmes risks perpetuating frameworks that prioritise technical competencies over empowerment. Addressing these barriers requires not only a deeper exploration of the interplay between individual agency and systemic constraints but also a deliberate effort to prioritise opportunities for birthing and nurturing individual agency. Such an approach ensures that interventions are all-inclusive and capable of driving sustainable, individual agency-driven outcomes in post-conflict settings. More importantly, employability is a lived experience of empowerment, adaptability, and autonomy in the face of systemic barriers rather than merely an external metric for success.

3. Mental Health and Psychosocial Well-Being in Education-to-Work Transition

Violent conflict is often associated with persistent adverse stressors and mental health problems occasioned by experiences such as injuries, witnessing violence, sexual abuse, displacement, and loss (

Amone-P’Olak et al. 2013). These stressors include lack of food, unsanitary living conditions, deprivation, and post-war poor educational outcomes. Numerous prior studies have found a connection between mental health problems and violent conflicts (

Amone-P’Olak et al. 2022;

Lim et al. 2022;

Musisi and Kinyanda 2020). Consequently, these mental health problems are associated with severe behavioural, emotional, and cognitive deficits that render many war-affected youth unemployable and/or unable to keep a job (

Betancourt et al. 2020). For instance, prior research indicated increased absenteeism, poor job performance, and challenges with mental and intrapersonal and interpersonal functioning among former war-affected youth in education and employment in Sierra Leone (

Betancourt et al. 2020).

Additionally, war-affected youths who are employed also exhibit low self-esteem, are frequently demoralised with heightened feelings of insecurity and low motivation, and have a limited capacity for self-reliance, all of which are essential to function well in employment (

Ripamonti 2023). Consequently, to ensure their long-term employability, the post-conflict reintegration of war-affected youth must address other levels of support beyond skills training to acquire gainful and sustainable employability. This section of the paper will address the need for mental health and psychosocial well-being for war-affected youth to reach their full potential in employment.

The negative mental health and psychosocial consequences of violent conflicts on young people are often neglected in the reintegration of war-affected youth. Drawing on the Cumulative Stress Hypothesis (CSH) (

Nederhof and Schmidt 2012), this paper addresses the background of war-affected youth that limits their successful reintegration. The CSH posits that cumulative exposure to stress leads to the build-up of a stress load, which increases the likelihood of developing mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, or PTSD (

Nederhof and Schmidt 2012). The accumulation of numerous stressors during violent conflicts and in the post-war environment is associated with emotional and behavioural problems that are likely to impact an individual’s functioning and relationships generally and in employment specifically (

Amone-P’Olak et al. 2014;

Betancourt et al. 2020;

Newnham et al. 2015). For instance, war-affected youth faced a variety of post-war environmental stressors such as economic issues (e.g., poverty and deprivation), family problems (e.g., rejection, dysfunction), community stressors (discrimination, stigma, gang violence, and land conflicts), alcohol and substance abuse, lack of food, and lack of social support (

Amone-P’Olak et al. 2014;

Lim et al. 2022;

Musisi and Kinyanda 2020). Therefore, if the accumulated stressors caused by violent conflicts and the post-conflict environment are not addressed, they will negatively impact the skills training and employability of young people afflicted by war.

On the contrary, the CSH also presents a mismatch hypothesis. According to the mismatch hypothesis, an individual who has experienced a high density of stress early in life is programmed to better deal with adversity and other stressors in later life (

Nederhof and Schmidt 2012). This is also in line with the post-traumatic growth hypothesis (

Tedeschi and Calhoun 2004), which may occur when an individual experiences adverse life events that significantly and meaningfully alter their perception of and relationship with the world, making them more resilient and positive (

Tedeschi and Calhoun 2004). Corresponding to the harsh life endured in captivity, war-affected youth bring to the interventions unique experiences that include survival skills, resilience, indigenous knowledge, and expectations (

Amone-P’Olak 2020). As a result, trainers and employers can harness the unique and beneficial experiences in rebel captivity that war-affected youth possess as a valuable support system to prepare them for training and better employment prospects. Consequently, interventions to support the psychosocial well-being of war-affected youth should extend beyond vocational skills training to build psychological and social capital to enable war-affected youth to achieve their full potential in employment.

In general, young people in Sub-Saharan Africa place a high priority on education. Most young people see formal education and skills training as a means of securing employment and a prosperous life (

Cieslik et al. 2022). Most of the war-affected youth have no possibility of being employed because violent conflicts disrupted their education and career opportunities (

Amone-P’Olak 2020;

Evans and Repper 2000). In the aftermath of violent conflicts, many sub-populations of young people can be identified based on their school backgrounds. These sub-populations include young people who have very little or no education, those who left primary or secondary school either before or due to the war, and those who completed a level of education but could not continue due to the war (

Peters et al. 2003).

For the young people listed above, vocational training may be more significant and pertinent for them than completing a previously interrupted academic programme (

Peters et al. 2003). Even in the absence of violent conflicts, all school graduates would not be able to find employment in the formal sector or white-collar jobs because these positions are scarce and difficult to secure (

Sumberg et al. 2020). Moreover, the education curricula for many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa do not seem to be relevant to many young people in the majority of war-afflicted countries (

Peters et al. 2003). In the post-war situation in most Sub-Saharan African countries, particularly where the majority of the youth live, the only plausible alternative to the white-collar job is self-employment in either a trade or a craft (

Peters et al. 2003). Although often undervalued, vocational training for self-employment is now a key focus of most post-war employment programmes for vulnerable youth as part of the disarmament, demobilisation, and reintegration (DDR) programmes (

Amone-P’Olak 2020;

Nezam and Marc 2010;

Peters et al. 2003).

Following several violent conflicts in Sub-Saharan Africa, the World Bank, UN agencies, NGOs, and numerous national governments launched DDR programmes (

Nezam and Marc 2010). The DDR programmes were run in many countries, such as Angola, Burundi, Chad, DR Congo, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and Uganda, among others (

Colleta et al. 1996,

2004). The majority of them did not, however, address the negative effects of violent conflicts on the mental health and psychosocial well-being of war-affected youth (

Nezam and Marc 2010). One such initiative was the Northern Uganda Youth Development Centre, which was founded in 2007 and supported by the Commonwealth Secretariat in the UK (

Amone-P’Olak et al. 2016). The centre was intended to provide vocational skills to the youth whose education was disrupted by the conflict in northern Uganda. Poor functioning and behavioural and mental health problems led to low retention rates, and many of the beneficiaries abandoned the centre, even though their education and training were subsidised (

Amone-P’Olak et al. 2016). While associated with increased school attendance, subsidies for education or any skilling programme alone do not influence classroom behaviour, mental health, functioning, or school retention, all important factors for successful skills training and employment outcomes for war-affected youths (

Betancourt et al. 2014). Consequently, the failure to address the mental health and psychosocial well-being of the war-affected youth may hinder their ability to reach their full potential.

To improve the mental health and well-being of war-affected youth, Betancourt and colleagues (2014) used an evidence-based intervention with war-affected youth in Sierra Leone to prepare them to return to education. The programme included a ten-week programme that included building group cohesion; trauma psychoeducation; links between beliefs and behaviour; problem-solving; relaxation, emotion regulation, and behavioural activation; building interpersonal skills; coping skills and problem-solving skills; addressing negative self-perceptions; making good choices; and working towards goals (

Betancourt et al. 2014). These psychosocial skill sets provide a vital foundation for the application of vocational skills and employment for war-affected youth. In addition to improving school enrolment, attendance, and classroom behaviour, the intervention showed remarkable post-intervention effects on emotion regulation, prosocial attitudes and behaviours, social support, and decreased functional impairment (

Betancourt et al. 2014). This can be accomplished through promoting a cooperative strategy that brings together multiple stakeholders with a range of skills and expertise from different organisations (

Ibrahim 2023).

Furthermore, programming for reintegration should take into consideration the gender differences that existed before, during, and post-conflict regarding the roles, responsibilities, experiences, needs, and vulnerabilities that war-affected male and female youths face at different phases during and in the aftermath of violent conflicts. The unique experiences and difficulties that girls are confronted with, such as increased stigma due to sexual violence, forced marriages, and early pregnancy, are part of the reality of many war-affected child mothers that exclude them from training and employment (

Amone-P’Olak et al. 2015). A risk analysis can be utilised to identify possible risk factors of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), including harmful practices and gendered social norms that contribute to SGBV risks for girls and boys, even if gender considerations are not restricted to sexual violence.

Finally, it would be beneficial for businesses and training programmes to incorporate young people’s perspectives into intervention design and programming. Where feasible, involve young people affected by war, their families, and the community in defining success criteria for training and job placement to improve their employability (

Ibrahim 2023). Rebuilding mutual understanding and trust between war-affected youth and the communities they are being reintegrated into is also crucial. This can be accomplished through promoting a cooperative strategy that brings together multiple stakeholders with a range of skills and expertise (

Ibrahim 2023).

To guarantee success, these programmes should be anchored in local sustainability (

Amone-P’Olak 2020;

Nezam and Marc 2010;

Peters et al. 2003). Education and skilling in different crafts and trades should not only be situated within the local economy for sustainability but should also be cognisant of the different sub-populations with unique needs and training requirements, such as war-affected child-mothers. In addition, different sub-populations should be involved in programming and designing interventions in a participatory research methodology approach.

Furthermore, reintegration services should be extended to the communities in which war-affected youth are being reintegrated, such as building community wells, schools, etc. Similarly, the psychosocial interventions should be anchored on local culture and support structures for success. For example, for child mothers, their close female relatives, such as aunts, can be involved as coaches, and for former boy-child soldiers, their male relatives or uncles can be involved as coaches or mentors. Ultimately, besides education and skilling programmes, interventions to mitigate the adverse mental health and psychosocial consequences of violent conflicts should be prioritised to prevent the further marginalisation and exclusion of war-affected youth from the labour market. In summary, this section has examined the inclusion of mental health and psychosocial well-being in youth education and employment in post-conflict settings in Sub-Saharan Africa. War-affected youth bring along unique experiences such as survival skills, resilience, indigenous knowledge, and expectations that can be harnessed in both education and the workplace (

Amone-P’Olak 2020).

4. Discussion

The limits of present training and educational methods for young people impacted by war are generally similar in regions affected by violent conflicts. The war-affected youth are impacted by the horrific lived experiences of violent conflicts in a variety of profound and complex ways (

Blanchet-Cohen et al. 2017). Prior research conducted in Sierra Leone and Uganda revealed that the experiences of war-affected youths are frequently ignored or their unique needs are not attended to in education and skill-training programmes (

Amone-P’Olak 2020;

Newnham et al. 2015). Employers and trainers in technical and vocational institutions need to be cognizant of the challenges faced by survivors of traumatic stress but also need to respond to these challenges responsively and responsibly. For instance, mental health and psychosocial support were largely disregarded in the northern Uganda Youth Development Centre skilling programme in northern Uganda, which resulted in low uptake and poor employment outcomes for the beneficiaries (

Amone-P’Olak 2020). However, a youth readiness intervention with war-affected youths in Sierra Leone was effective in lowering mental health and psychosocial problems and enhancing self-regulation and functioning, all of which are critical factors for employability and job retention (

Newnham et al. 2015).

This proactive engagement requires individual agency, mental and psychosocial well-being, and life skills. Accordingly, the education-to-work transition must create a safe space to engage the war-affected youth in charting out their futures (

Blanchet-Cohen et al. 2017). The lack of engagement of the war-affected youth by the educational and skills training institutions puts the youth at risk of exclusion and feeling trapped or even coerced into skills training programmes that they may not find interesting (

Blanchet-Cohen et al. 2017). However, when employees at training and education institutions receive the necessary training and support, they can provide safe places to meaningfully engage young people affected by war (

Ellis et al. 2011).

While individual agency is crucial for employability, employment can also impart a sense of purpose, enhance self-esteem and self-concept, bolster career self-efficacy and opportunities, and contribute to overall well-being, in that way influencing one’s agency (

Zhao et al. 2012). Likewise, employment also provides the youth with a sense of belonging, an important social capital and network that helps them to cope with mental health and psychosocial problems, thus reducing the risk of dropping out of training institutions and employment (

Blanchet-Cohen et al. 2017).

Transitioning from education to employment is a critical phase for youth employability (

Bukuluki et al. 2020). Individual agency plays a key role in bridging the gap between learning in school and finding meaningful work (

Fantinelli et al. 2024). Personal preference, interest, and contentment with vocational choice all have a big impact on how useful and satisfied the youth are with their work (

Fantinelli et al. 2024). Education, as

McGrath (

2022) highlights, is meant to provide future-ready skills, but in many cases, there is a disconnect between what students are taught and what employers in these fields require. This gap often leaves young people struggling to navigate an already challenging environment. Thus, resilience and adaptability, as

Nguyen (

2024) emphasises, are especially critical for youth in post-conflict settings, where instability and limited opportunities present unique hurdles. These insights highlight the importance of equipping the youth with both practical skills and the tools to thrive in unpredictable environments. Similarly, aligning education with local labour market demands while fostering resilience and individual agency is essential to help youth in post-conflict areas overcome these challenges. In doing so, structural reforms are urgently required in post-conflict settings to support the youth in overcoming systemic barriers. Charting an inclusive education, a relevant and a fit-for-purpose training pathway embedded in the local economy is critical for reintegration (

Blanchet-Cohen et al. 2017;

Nezam and Marc 2010).

In addition, entrenching a reflective and experiential learning within educational frameworks, cultivating the agency required for navigating complex employment landscapes, are important for the war-affected and youths in vulnerable situations (

Bordogna and Lundgren-Resenterra 2023). These perspectives align with

Kahn and Lundgren-Resenterra’s (

2021) assertion that agency must be contextualised within broader social and organisational frameworks, ensuring support systems and resources are available to individual initiatives.

Meanwhile,

Apunyo et al. (

2022) highlight skill-building programmes emphasising decision-making and adaptability, both vital entrepreneurial and traditional employment pathways. Nevertheless, this ought to be augmented with 21st-century skills such as entrepreneurship, effective communication, collaboration, creativity, and digital literacy. This skills training should be based on a curriculum that is not only content-based, problem-based, and competency-based but also systems-based and extends skills training to the realities in the community, workplace, and labour market (

McGrath 2022). Moreover, mentorship initiatives and professional networking, as evidenced by

Burnett (

2023), provide youth with role models and practical guidance, facilitating transitions from education to employment. Entrepreneurial support systems, including access to capital and technical training, empower youth to independently navigate labour market challenges. Furthermore, advocating for interventions that integrate reflective practices, enabling individuals to critically assess and enhance their employability capacities, is imperative (

Forrier et al. 2018).

In summary, while global perspectives provide valuable frameworks and interventions, crucial elements such as individual agency, mental health and psychosocial challenges, and the local economy are still neglected. This study identifies a significant gap in understanding how individual agency operates in post-conflict settings. Bridging these gaps requires a concerted effort to generate empirical insights and align policy frameworks with local economic realities.

4.1. Implications and Recommendations for Youth Education-to-Work Programmes

The findings of this review indicate that education-to-work programmes for war-affected youth must adopt an integrated approach that addresses mental health and psychosocial problems, life skills, and local labour market and economic realities. To adopt this integrated approach, a participatory action research approach should be taken, involving war-affected youths, education and training institutions, potential employers, and all other stakeholders. Together, they should co-design a curriculum that includes mental health and psychosocial support and life skills beyond technical and vocational education (

Amone-P’Olak 2020;

Blanchet-Cohen et al. 2017;

Ellis et al. 2011;

Newnham et al. 2015;

Zhao et al. 2012). This includes incorporating psychosocial assessments, trauma recovery components, peer support systems, and staff training in trauma-informed care and psychological first aid (

Newnham et al. 2015;

Ripamonti 2023). These measures are critical to creating safe learning environments that enable youth participation and retention. Moreover, life skills such as communication, decision-making, emotional regulation, and conflict resolution should be delivered alongside technical and vocational training. These non-cognitive skills support both workplace functioning and reintegration in post-conflict societies (

Ibarraran et al. 2014;

McGrath 2022).

Programmes should also align closely with local labour market demands. Collaborating with employers, trade associations, and local government helps ensure that training remains responsive to economic opportunities, whether in agriculture, crafts, or small-scale entrepreneurship (

Keith Mark 2021;

Nezam and Marc 2010). A report by an NGO on war-affected youths in northern Uganda revealed that only 21.9% of youth who underwent vocational training felt economically empowered, and 27.8% found their acquired skills inadequate or irrelevant to market demands (

International Alert 2013). Consequently, skills development programmes should be tailored to the demands of the labour market and local economy to guarantee that graduates secure jobs after training (

Blanchet-Cohen et al. 2017;

Nezam and Marc 2010). For example, the focal point of support for war-affected youth in Ethiopia following the violent conflict was the local economy, where rural youths were supported in subsistence farming (coffee, wheat, and animals) while the urban ones were supported in apprenticeships and microcredits to operate small-scale businesses (

Blanchet-Cohen et al. 2017;

Nezam and Marc 2010). Other programmes, such as the EU-supported local integration of refugees in Uganda, have provided skills training for over 2500 refugees, including youth, women, and local communities, emphasising competencies aligned with the settlement economy (

Keith Mark 2021).

Interventions must also be tailored to the specific needs of vulnerable sub-populations, including victims of sexual abuse and child mothers with unique needs (

Amone-P’Olak 2005;

Amone-P’Olak et al. 2015), youth with disabilities, and former combatants. These groups may face additional barriers such as stigma, educational gaps, and caregiving responsibilities, and should receive targeted support, including flexible learning pathways and community-based reintegration strategies (

Amone-P’Olak et al. 2016).

For young people affected by war, life skills—also referred to as “soft” or “non-cognitive” skills—are essential. These abilities are intended to impart a wide range of behavioural and social skills that enable individuals to navigate the challenges of daily living successfully. These skills include decision-making (such as problem-solving and critical and creative thinking); community living (such as effective communication, resisting peer pressure, forming healthy relationships, and resolving conflicts); and individual awareness and management (e.g., self-awareness, self-esteem, emotional regulation, assertiveness, stress management, and sexual and reproductive health behaviours and attitudes) (

Ibarraran et al. 2014). Consequently, life skills training can improve functioning, enhance occupational performance, and boost self-esteem and confidence (

Ibarraran et al. 2014).

Rebuilding mutual understanding and trust between war-affected youth and the communities they are being reintegrated into is also crucial. Additionally, this will reduce the possibility that young people affected by war will become a privileged group, which might promote resentment and envy in the receiving community.

The promotion of consortia strategy for reintegrating war-affected youths is crucial because many governments lack forward-looking labour market analyses in post-conflict situations. This hinders the education-to-work transition for war-affected youth. Accordingly, programming should be across government, donors, UN, NGOs, and local civil society organisations, bringing together multiple actors with a range of skills and expertise in curriculum design, mental health, and psychosocial and life skills (

Blanchet-Cohen et al. 2017;

Nezam and Marc 2010).

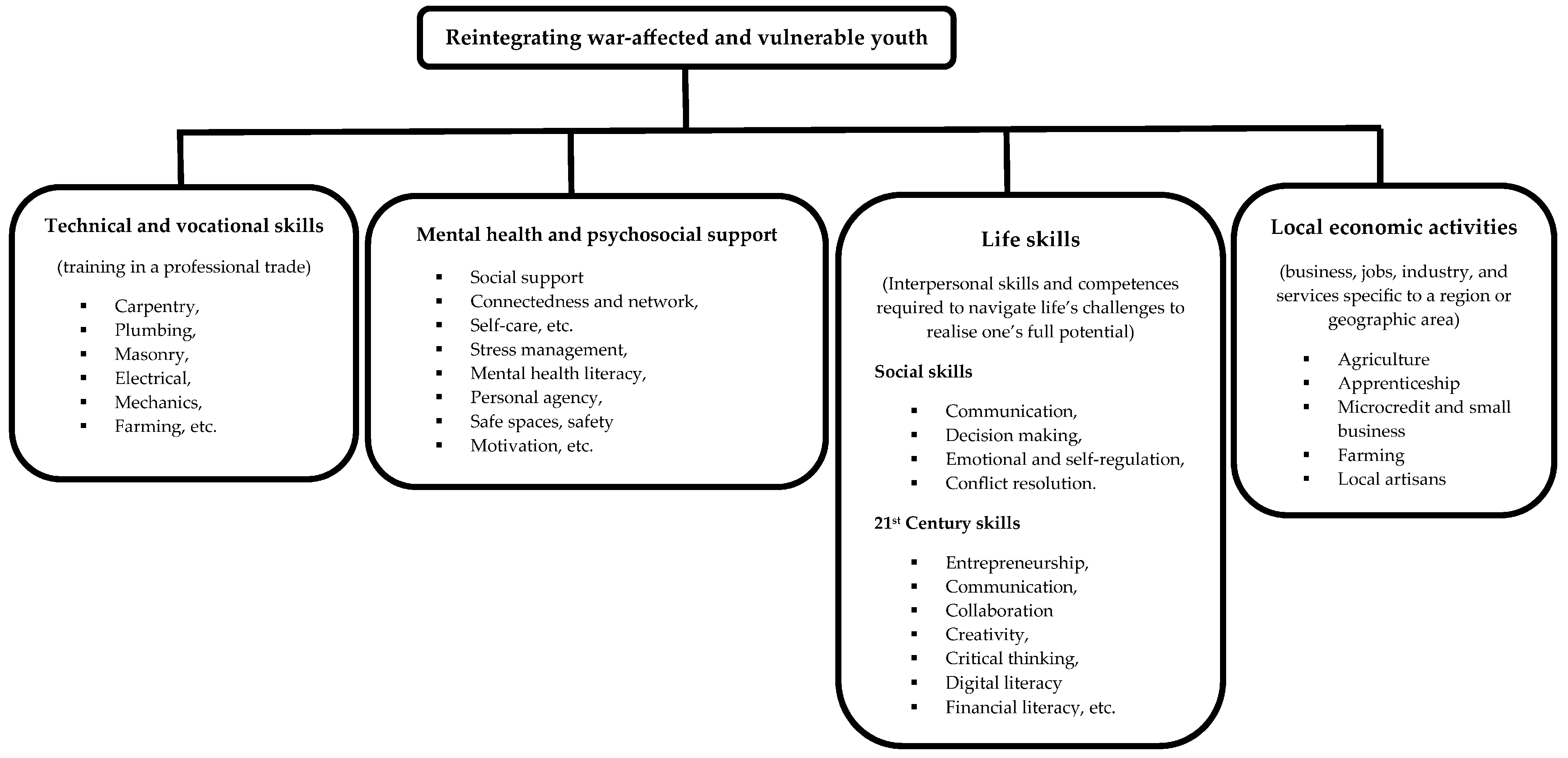

4.2. Integrated Model of Reintegrating War-Affected and Vulnerable Youths

The challenges of reintegrating war-affected and vulnerable youth outlined and discussed above demonstrate the need for a new and inclusive approach. Consequently, we propose an integrated model for reintegrating war-affected and other vulnerable youth. The proposed integrated model is anchored on professional, technical, and vocational skills training; individual agency; provision of mental health and psychosocial support; and life skills training, all situated within a local market and economic realities (see

Figure 1). This integrated model is based on the deficiencies demonstrated in Sierra Leone (

Betancourt et al. 2020) and shown to work in Ethiopia (

Blanchet-Cohen et al. 2017;

Nezam and Marc 2010). The crucial elements of the proposed model in

Figure 1 highlight the theoretical concepts that the reintegration of war-affected and other vulnerable youth may be anchored on to achieve success.

Future education-to-work programmes should go beyond addressing the skills gaps among war-affected youth. They should harness individual agency and tackle mental health and psychosocial challenges while building on survival skills, resilience, and indigenous knowledge, following the harsh conditions during the violent conflicts. This can enhance and reinforce self-worth, foster a sense of purpose, and increase engagement during the education-to-work transition. Additionally, further research should involve war-affected youth using a participatory action research methodology. Participatory action research would offer an opportunity for an in-depth analysis of the challenges and opportunities highlighted in this review (

Blanchet-Cohen et al. 2017). Also, a participatory research methodology will involve the young people who have been impacted by the war to jointly co-create knowledge and jointly tackle youth problems.