Challenges and Advances in Gender Equity: Analysis of Policies, Labor Practices, and Social Movements

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

- P (Population): Women and groups vulnerable to gender discrimination and inequality;

- I (Interest): Impact of public policies;

- Co (Context): Diverse socio-economic and political environments.

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Inclusion criteria: Original scientific articles published in peer-reviewed indexed journals, studies published in English or Spanish, and research explicitly focused on evaluating how public policies, labor structures, and social movements impact gender equity;

- Exclusion criteria: Documents that did not directly address the impact of public policies on the specific topic, book chapters, conference proceedings, theses, or non-peer-reviewed gray literature.

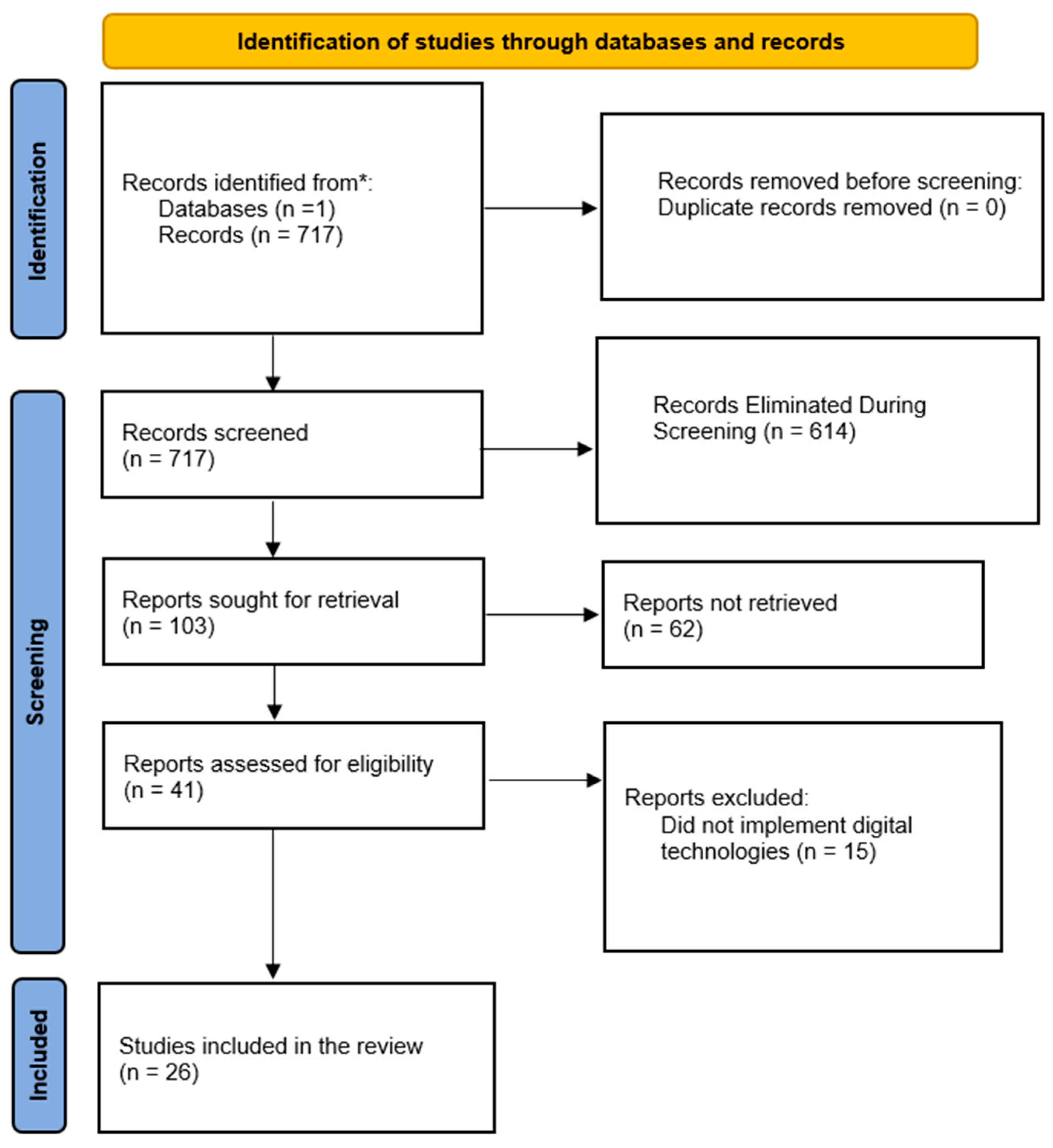

2.3. Document Selection Process (PRISMA)

- Identification: Initial retrieval of articles from Scopus using the search equation;

- Screening: Removal of duplicate documents;

- Eligibility: Review of titles and abstracts according to inclusion and exclusion criteria;

- Inclusion: Full-text reading of the remaining articles and critical evaluation by two expert researchers to ensure methodological quality and thematic relevance.

2.4. Bibliometric Analysis

- Annual publication trends;

- Scientific journals with the highest output on the topic;

- The geographical distribution of publications (collaborations between countries).

3. Results

3.1. Bibliometric Analysis

- International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal—SJR: 1.763 (Q1)

- Revista de Salud Pública—SJR: 0.148 (Q4)

- Vibrant Virtual Brazilian Anthropology—SJR: 0.145 (Q4)

3.2. International Collaboration Network

3.3. Thematic Distribution of the Selected Articles

3.4. Public Policies and Gender-Based Violence

3.5. Wage Inequality and Workplace Barriers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author | Study Title | Country | Methodology | Type of Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Javakhishvili and Jibladze (2018) | Analysis of Anti-Domestic Violence Policy Implementation in Georgia Using Contextual Interaction Theory (CIT) | Georgia | Qualitative | Contextual Interaction Theory (CIT), interviews |

| Ramírez et al. (2015) | Building a Public Policy Agenda Gender of Men in Mexico: Prolegomenon | Mexico | Qualitative | Document analysis, theoretical discussion |

| Ariza-Ruiz et al. (2017) | Challenges of Menstruation in Girls and Adolescents from Rural Communities of the Colombian Pacific | Colombia | Mixed methods | Surveys, focus groups |

| Frías (2017) | Challenging the Representation of Intimate Partner Violence in Mexico: Unidirectional, Mutual Violence, and the Role of Male Control | Mexico | Mixed methods | Police data, victim testimonies |

| Linthon-Delgado and Méndez-Heras (2022) | Decomposition of the Gender Wage Gap in Ecuador | Ecuador | Quantitative | Decomposition analysis using survey data |

| Arzú (2021) | Diagnosis of Racism and Discrimination in Guatemala: Qualitative and Participatory Methodology for the Development of a Public Policy | Guatemala | Qualitative | Participatory methods, interviews |

| Hoyt and Kurtulus (2025) | Examining the Effect of Wrongful Discharge Laws on Women’s Occupational Employment | USA | Quantitative | Regression analysis with labor statistics |

| Naradech (2023) | Factors of Gender Discrimination Against Transgender Women in Private Organizations in Bangkok, Thailand | Thailand | Quantitative | Survey of private sector HR departments |

| Zetter et al. (2017) | Gender Desegregated Analysis of Mexican Inventors in Patent Applications Under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) | Mexico | Quantitative | Patent application data analysis |

| Bilan et al. (2020) | Gender Discrimination and Its Links with Compensation and Benefits Practices in Enterprises | Ukraine/Poland | Quantitative | Enterprise survey data |

| Proni and Proni (2018) | Gender Discrimination in Large Companies in Brazil | Brazil | Mixed methods | Surveys, case study of corporations |

| Ayentimi et al. (2020) | Gender Equity and Inclusion in Ghana: Good Intentions, Uneven Progress | Ghana | Mixed methods | Policy review, interviews |

| Plomien (2019) | Gender Inequality by Design: Does Successful Implementation of Childcare Policy Deliver Gender-Just Outcomes? | Poland | Qualitative | Policy analysis |

| Forgues-Puccio and Lauw (2021) | Gender Inequality, Corruption, and Economic Development | Multiple (cross-national) | Quantitative | Econometric modeling |

| Chakraborty (2020) | Gender Wage Differential in Public and Private Sectors in India | India | Quantitative | Public/private sector labor data analysis |

| Levasseur and Paterson (2016) | Jack (and Jill) of All Trades—A Canadian Case Study of Equity in Apprenticeship Supports | Canada | Qualitative | Case study |

| Phipps and Prieto (2021) | Leaning In: A Historical Perspective on Influencing Women’s Leadership | USA/Spain | Qualitative | Historical analysis |

| Russi-Ardila (2020) | Legitimate Guarantee of the Public Gender Equity Policy in a Health Institution in Facatativá | Colombia | Qualitative | Institutional review, staff interviews |

| Ferdous and Mallick (2019) | Norms, Practices, and Gendered Vulnerabilities in the Lower Teesta Basin, Bangladesh | Bangladesh | Mixed methods | Field research, interviews |

| Essig and Soparnot (2019) | Re-thinking Gender Inequality in the Workplace: A Framework from the Male Perspective | France | Qualitative | Organizational analysis |

| Kim and Kim (2017) | Socio-Ecological Perspective of Older Age Life Expectancy: Income, Gender Inequality, and Financial Crisis in Europe | Europe | Quantitative | Cross-country public health data |

| Lambert et al. (2021) | Socio-Economic Impacts of COVID-19 on Working Mothers in France | France | Qualitative | Survey of working mothers |

| Welsh et al. (2017) | The Influence of Perceived Management Skills and Perceived Gender Discrimination in Launch Decisions by Women Entrepreneurs | USA | Quantitative | Survey of entrepreneurs |

| Méndez-Suárez et al. (2025) | The Perception of Effort as a Driver of Gender Inequality: Institutional and Social Insights for Female Entrepreneurship | Spain/Latin America | Mixed methods | Institutional analysis, survey |

| Matthews (2022) | The Politics of Protest and Gender: Women Riding the Wings of Resistance | Thailand | Qualitative | Ethnographic analysis |

| McGrath et al. (2022) | The WCAA Global Survey of Anthropological Practice | Global | Quantitative | Survey of anthropologists |

References

- Afolabi, Adedeji O., and Ifeoluwa R. Akinlolu. 2021. Evaluation of women’s access to building credits from banks in Nigeria. Banks and Bank Systems 16: 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, Fahad, Khalid Gufran, Ali Alqerban, Abdullah Saad Alqahtani, Saeed N. Asiri, and Abdullah Almutairi. 2024. Evaluation of Compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Guidelines for Conducting and Reporting Systematic Reviews in Three Major Periodontology Journals. The Open Dentistry Journal 18: e18742106327727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Ruiz, Liany Katerine, Maria Juana Espinoza Menéndez, and Jorge Martín Rodriguez Hernández. 2017. Challenges of menstruation in girls and adolescents from rural communities of the Colombian Pacific. Revista de Salud Publica 19: 833–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzú, Marta Elena Casaus. 2021. Diagnosis of racism and discrimination in guatemala: Qualitative and participatory methodology for the development of a public policy. Vibrant Virtual Brazilian Anthropology, e18807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayentimi, Desmond Tutu, Hossein Ali Abadi, Bernice Adjei, and John Burgess. 2020. Gender equity and inclusion in Ghana; good intentions, uneven progress. Labour and Industry 30: 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilan, Yuriy, Halyna Mishchuk, Natalia Samoliuk, and Viktoriia Mishchuk. 2020. Gender discrimination and its links with compensations and benefits practices in enterprises. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review 8: 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, Shiney. 2020. Gender Wage Differential in Public and Private Sectors in India. Indian Journal of Labour Economics 63: 765–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essig, Elena, and Richard Soparnot. 2019. Re-thinking gender inequality in the workplace—A framework from the male perspective. Management 22: 373–410. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdous, Jannatul, and Dwijen Mallick. 2019. Norms, practices, and gendered vulnerabilities in the lower Teesta basin, Bangladesh. Environmental Development 31: 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgues-Puccio, Gonzalo F., and Erven Lauw. 2021. Gender inequality, corruption, and economic development. Review of Development Economics 25: 2133–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frías, Sonia M. 2017. Challenging the representation of intimate partner violence in Mexico: Unidirectional, mutual violence and the role of male control. Partner Abuse 8: 146–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, Mohammad-Salar, Farid Jahanshahlou, Mohammad Amin Akbarzadeh, Mahdi Zarei, and Yosra Vaez-Gharamaleki. 2024. Formulating research questions for evidence-based studies. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health 2: 100046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyt, Eric, and Fidan Ana Kurtulus. 2025. Examining the Effect of Wrongful Discharge Laws on Women’s Occupational Employment. Labour 39: 101–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javakhishvili, Nino, and Gvantsa Jibladze. 2018. Analysis of Anti-Domestic Violence Policy Implementation in Georgia Using Contextual Interaction Theory (CIT). Journal of Social Policy 47: 317–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jong In, and Gukbin Kim. 2017. Socio-ecological perspective of older age life expectancy: Income, gender inequality, and financial crisis in Europe. Globalization and Health 13: 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, Anne, Violaine Girard, and Elie Guéraut. 2021. Socio-Economic Impacts of COVID-19 on Working Mothers in France. Frontiers in Sociology 6: 732580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levasseur, Karine, and Stephanie Paterson. 2016. Jack (and Jill?) of All Trades—A Canadian Case Study of Equity in Apprenticeship Supports. Social Policy and Administration 50: 520–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linthon-Delgado, Diego Emilio, and Lizethe Berenice Méndez-Heras. 2022. Decomposition of the gender wage gap in Ecuador. Revista Mexicana de Economia y Finanzas Nueva Epoca 17: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Xiaoyan, and Wenfang Tang. 2020. Sexism in Mainland China and Taiwan: A social experimental study. China: An International Journal 18: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, Tasia. 2022. The Politics of Protest and Gender: Women Riding the Wings of Resistance. Social Sciences 11: 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, Pam, Greg Acciaioli, Adele Millard, Emily Metzner, Vesna Vučinić Nešković, and Chandana Mathur. 2022. The WCAA Global Survey of Anthropological Practice (2014–2018): Reported Findings. Vibrant Virtual Brazilian Anthropology, e19701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Hernández, Edith, María José Fernández-Gómez, and Inmaculada Barrera-Mellado. 2021. Gender Inequality in Latin America: A Multidimensional Analysis Based on ECLAC Indicators. Sustainability 13: 13140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Suárez, Mariano, Ramón Arilla, and Luca Delbello. 2025. The perception of effort as a driver of gender inequality: Institutional and social insights for female entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 21: 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, Sabah, Jinan Fiaidhi, and Rahul Kudadiya. 2023. Integrating a PICO Clinical Questioning to the QL4POMR Framework for Building Evidence-Based Clinical Case Reports. Paper presented at 2023 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), Sorrento, Italy, December 15–18; pp. 4940–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naradech, Khemmanath. 2023. Factors of Gender Discrimination Against Transgender Women in Private Organizations in Bangkok, Thailand. Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences Studies 23: 593–608. [Google Scholar]

- Phipps, Simone T. A., and Leon C. Prieto. 2021. Leaning in: A Historical Perspective on Influencing Women’s Leadership. Journal of Business Ethics 173: 245–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plomien, Ania. 2019. Gender inequality by design: Does successful implementation of childcare policy deliver gender-just outcomes? Policy and Society 38: 643–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proni, Thaíssa Tamarindo da Rocha Weishaupt, and Marcelo Weishaupt Proni. 2018. Gender Discrimination in Large Companies in Brazil. Revista Estudos Feministas, e41780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, Juan Carlos, Norma Celina Gutiérrez de la Torre, and Lizett Guadalupe Cázares Hernández. 2015. Building a public policy agenda gender of men in Mexico: Prolegomenon. Masculinities and Social Change 4: 186–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Russi-Ardila, Jacqueline. 2020. Legitimate guarantee of the public gender equity policy in an institution provider of health of facatativa. Revista de Salud Publica 22: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Prashasti, Vivek Kumar Singh, and Anurag Kanaujia. 2025. Exploring the Publication Metadata Fields in Web of Science, Scopus and Dimensions: Possibilities and Ease of doing Scientometric Analysis. Journal of Scientometric Research 13: 715–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Elst, Wim. 2024. The R Programming Language. In Regression-Based Normative Data for Psychological Assessment: A Hands-On Approach Using R. Edited by En W. Van der Elst. Cham: Springer, pp. 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, Biju, Manas Chatterjee, Vishal Sharma, and Ravinder Sahdev. 2025. Indexing of Journals and Indices of Publications. Indian Journal of Radiology and Imaging 35: S148–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, Dianne H. B., Eugene Kaciak, and Caroline Minialai. 2017. The influence of perceived management skills and perceived gender discrimination in launch decisions by women entrepreneurs. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 13: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetter, Berenice Cepeda, Claudia González Brambila, and Miguel Ángel Pérez Angón. 2017. Gender desegregated analysis of Mexican inventors in patent applications under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT). Interciencia 42: 204–11. [Google Scholar]

| Author (Year) | Country/Context | Main Findings | Recommendations/Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Javakhishvili and Jibladze (2018) | Georgia | Anti-domestic violence policies are implemented symbolically due to lack of cooperation between actors, low motivation, and deeply rooted gender inequality. | Strengthen inter-institutional cooperation, improve training and resources for key actors, and enhance awareness campaigns on gender equality. |

| Frías (2017) | Mexico | Intimate partner violence is mostly perpetrated by men, although there are also cases of mutual violence. Male control is a key factor. | Design comprehensive policies that address violence from a gender perspective, considering its complexity and avoiding a one-sided focus. |

| Russi-Ardila (2020) | Colombia (Facatativá) | The gender equity policy in a healthcare institution includes protocols for assisting victims of sexual violence, but staff training and protective measures remain inadequate. | Increase supervision of policy implementation, provide continuous training to healthcare personnel, and strengthen mechanisms for reporting and protection. |

| Ramírez et al. (2015) | Mexico | Although focusing on men and gender, the study highlights that violence and patriarchal culture require public policies that involve men in promoting gender equity. | Develop public policies that integrate men as agents of change in preventing gender-based violence. |

| Matthews (2022) | Thailand | Women have played a crucial role in resistance movements, including protests against gender-based violence. | Recognize and protect the role of female activists, establish legal frameworks that ensure gender demands are included in political agendas. |

| Author (Year) | Country | Main Findings | Recommendations/Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linthon-Delgado and Méndez-Heras (2022) | Ecuador | Direct discrimination is the primary cause of the gender wage gap. | Implement public policies for monitoring and sanctioning wage discrimination, promote incentives for equitable hiring, and train businesses on gender equality. |

| Proni and Proni (2018) | Brazil | Gender discrimination persists in large companies; women receive lower wages and face a glass ceiling in promotions. | Establish gender quotas in executive positions, enforce wage gap monitoring, and launch corporate awareness campaigns. |

| Chakraborty (2020) | India | The wage gap is more pronounced in the public sector, where women are often hired for low-paying jobs in health and education. | Restructure salary schemes in the public sector, enhance training programs, and promote female career advancement in government programs. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peralta-Jaramillo, K.G. Challenges and Advances in Gender Equity: Analysis of Policies, Labor Practices, and Social Movements. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 401. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070401

Peralta-Jaramillo KG. Challenges and Advances in Gender Equity: Analysis of Policies, Labor Practices, and Social Movements. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(7):401. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070401

Chicago/Turabian StylePeralta-Jaramillo, Kiara Geoconda. 2025. "Challenges and Advances in Gender Equity: Analysis of Policies, Labor Practices, and Social Movements" Social Sciences 14, no. 7: 401. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070401

APA StylePeralta-Jaramillo, K. G. (2025). Challenges and Advances in Gender Equity: Analysis of Policies, Labor Practices, and Social Movements. Social Sciences, 14(7), 401. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070401