1. Introduction

The transition from education to employment has traditionally been conceptualised as a linear process, where individuals progress sequentially from primary to secondary education, then to higher education, and finally into stable employment. However, this model does not accurately reflect the global realities. Increasingly, education-to-work trajectories have become non-linear, marked by interruptions, re-skilling, career shifts, and lifelong learning, reflecting broader structural and personal transitions in modern societies (

Busemeyer and Trampusch 2020;

Skrobanek 2016). Economic transformations, technological advancements, and labour market volatility have reshaped workforce demands, compelling individuals to seek diverse educational routes, including vocational training, online learning, and preparatory programs, to acquire necessary skills.

Gonzalez and Stephany (

2024) observe a shift towards skill-based hiring in emerging fields like artificial intelligence and green jobs, noting that employers increasingly value specific competencies over formal qualifications; they recommend alternative skill-building formats such as apprenticeships, on-the-job training, massive open online courses (MOOCs), vocational education and training, micro-certificates, and online bootcamps to address talent shortages.

Elia et al. (

2023) discuss the challenges organisations face in predicting workforce requirements due to rapid technological adoption. They propose an ontology linking business transformation initiatives to occupations and skills, aiming to guide enterprises and educational institutions in aligning workforce development with evolving business needs.

Weichselbraun et al. (

2022) address the surge in reskilling and upskilling programs triggered by labour market disruptions. They introduce a knowledge extraction system that integrates educational programs from various providers into a unified knowledge graph, facilitating the search, comparison, and selection of suitable continuing education options for individuals seeking to update their skills. In regions where socio-economic inequalities and institutional barriers limit direct university entry, non-traditional pathways are even more prevalent, necessitating policies that accommodate diverse learning experiences (

McCowan 2007,

2019).

One of the most significant barriers to higher education and career progression is the lack of requisite academic qualifications. Many students, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds, face systemic hurdles such as low-quality secondary education, inadequate career guidance, and exclusionary admission criteria, which collectively undermine their access to higher education (

McCowan 2007,

2019;

Tewari and Ilesanmi 2020;

Moses et al. 2017). These challenges disproportionately affect students from rural and economically marginalised communities, where secondary schooling infrastructure and educational resources remain inadequate (

UNESCO 2019). As a result, many prospective students find themselves excluded from university education, limiting their career opportunities and socio-economic mobility.

Recognising the barriers posed by rigid admission requirements, universities worldwide have introduced preparatory programs as alternative entry pathways. These programs serve as bridging mechanisms, providing students with foundational academic skills, discipline-specific knowledge, and university readiness training (

Dodd et al. 2023). In high-income countries such as Australia, foundation-year programs and academic bridging courses have been institutionalised as part of national higher education frameworks (

Gale and Parker 2013). In many African countries, preparatory and access programs are increasingly recognised as vital tools to address educational disparities and offer second chances to non-traditional or underprepared learners (

Mohamedbhai 2014).

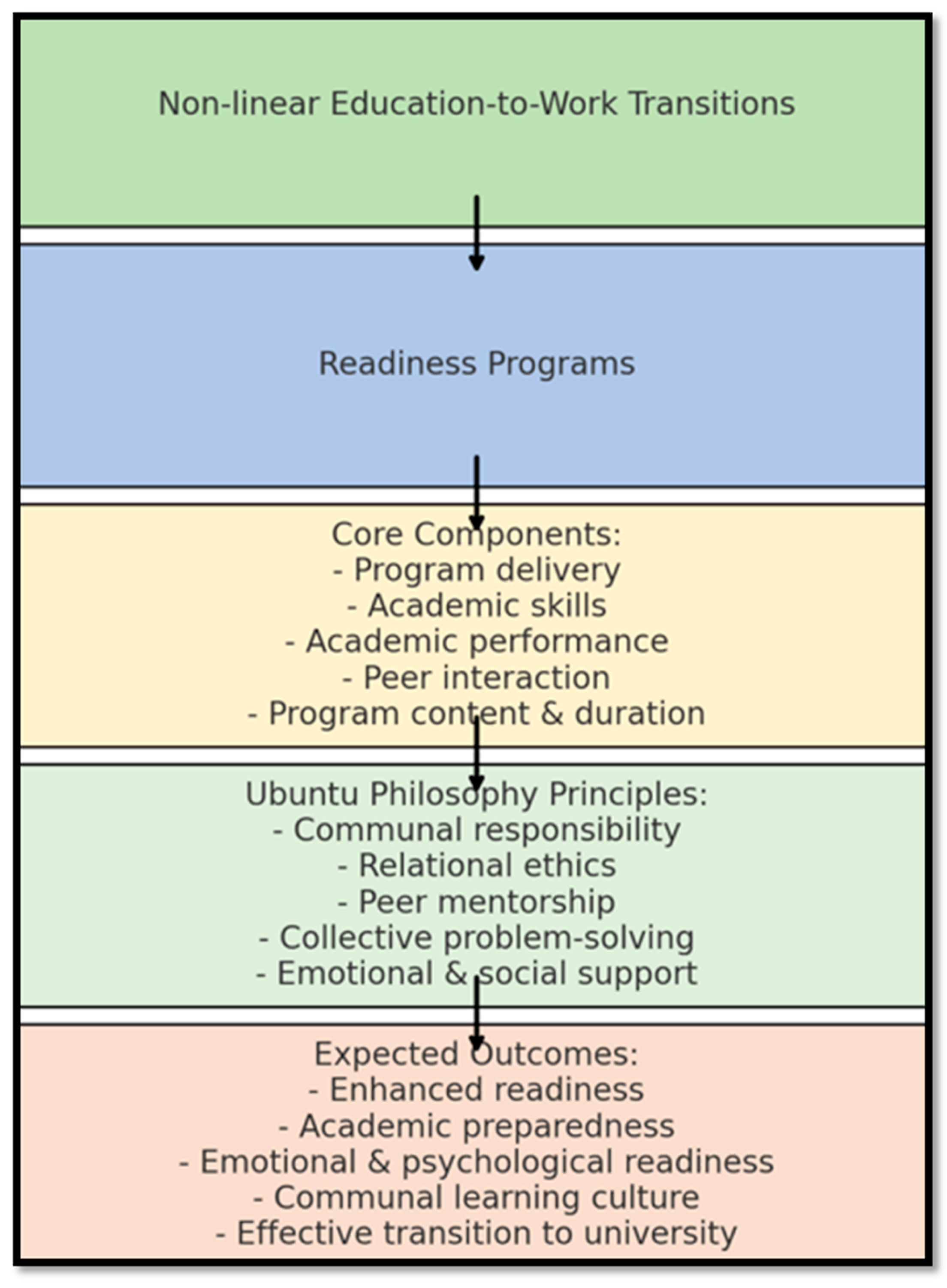

This study explores the effectiveness of readiness programs and draws implications for the integration of the African Ubuntu philosophy into such programs. The study tests the null hypothesis that the readiness programs do not significantly influence the readiness of the participants to go for university studies. Understanding how readiness programs influence readiness informs the design of more effective interventions, ensuring that those willing to join universities are better prepared to navigate complex educational and career landscapes, on the one hand, and drawing implications for the integration of the African Ubuntu philosophy into such programs is important for the education processes contextualisation in Africa. The key questions for this study are, therefore: To what extent are the readiness programs effective in the readiness of the participants to go for university studies?; and How can the Ubuntu philosophy be integrated in the readiness programs for effective readiness program delivery in the African context?

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 presents the literature review,

Section 3 outlines the methodology,

Section 4 reports the findings and interpretation,

Section 5 discusses the findings in light of the African Ubuntu, and

Section 6 provides the conclusion and recommendations.

3. Study Methodology

The research used a quantitative approach in data collection and analysis. The population was composed of all 2024 Readiness Program students, who were about 3057 in total. The survey targeted all participants in the Readiness Program, with the actual number of the participants depending on those who willed and participated in the survey. Participation in the survey was voluntary and open to all students enrolled in the Readiness Program. While all students were invited, the final sample reflects those who chose to participate, introducing a potential self-selection bias that is acknowledged in interpreting the findings. The survey was conducted online by sharing Google Forms to student WhatsApp groups to facilitate easy access and completion. To maximise participation, students were given one week to complete the survey, with periodic reminders to encourage participation. The response rate was approximately 37% of the total enrolled population, which is consistent with typical online survey response rates in educational research.

The data, with an Alpha co-efficient of 0.8148, has high reliability and the variables are internally consistent. Content validity of the questionnaire was established through expert review by academic staff experienced in higher education and readiness programs. A small-scale pilot test was also conducted with 11 students to ensure clarity of the items and response options. Descriptive statistics are used to provide a general overview of the variables. Indices on the issues of appropriateness of program structure and delivery, resilience to the burden of challenges, and the effectiveness of the program, are used to reduce multi-collinearity for their combined effect rather than the individual components. Missing data were minimal (<2%) and were handled through listwise deletion. The dataset was also checked for outliers, and no extreme values were found to significantly distort the results. An ordered logistic regression is used with the dependent variable being readiness to go to university (ordered on a 5-Likert scale) and the independent variables being appropriateness of program structure, appropriateness of program delivery, resilience to the burden of challenges, and the program effectiveness. Ordered logistic regression was selected because the dependent variable (readiness to go to university) is an ordinal variable with five ordered categories. The assumptions of proportional odds were checked and found to be acceptable for this model.

The participants of the survey were all informed about the purpose of the survey, the voluntary nature of participation, and that the data would be used for the improvement of the program. All responses were anonymous, with no identifying information collected. The data for the survey is password-protected in a folder on a university computer in form of Google Form, CSV, Excel, and Stata (version 15) files.

This paper is based on data originally collected as part of an internal program evaluation exercise, conducted under the university’s routine quality assurance processes. At the time of data collection, the intent was not for formal research, but for internal program improvement. The data are fully anonymised and aggregate, and no individual participant is identifiable in the analysis. Following the identification of broader academic relevance in the findings, the authors developed this manuscript for scholarly dissemination. No sensitive personal data are presented, and no foreseeable risk of harm to participants exists. The university’s ethics office has been consulted regarding this matter.

4. Findings and Interpretation

4.1. Demography and Readiness Program

In presenting the findings, this section links the results to the study’s two research questions and to the theoretical perspectives on non-linear transitions and Ubuntu philosophy discussed in the literature review.

Table 1 summarises the findings regarding the demographic characteristics of the participants.

The majority of participants (47.79%) fall within the 25–30 age group, who delay their entry into university for various reasons, including financial constraints, personal circumstances, or career-related factors such as initial workforce entry. This suggests that Readiness Programs appeal to those who initially entered the workforce or other forms of post-secondary education before considering university. The 18–24 age group constitutes 28.27%, a segment of traditional university-aged students, who did not meet direct admission criteria or feel the need for additional academic preparation. Students lacking adequate academic readiness are more likely to require remedial coursework upon entering higher education due to insufficient academic preparation during secondary education. The participation of individuals aged 31–40, accounting for 22.79% of the enrolees, underscores the significance of such programs in facilitating lifelong learning and career transitions. Such individuals seek to enhance their skills, pivot to new career paths, or advance within their current professions. The minimal participation of individuals over 40 years old in readiness programs, constituting only 1.15% of participants, reflects two broad trends observed in adult education. The first one is that older adults often face significant barriers that deter them from engaging in further education. Adult learners often confront a complex web of challenges that can deter them from pursuing further education. Financial responsibilities such as covering household expenses, paying children’s school fees, and sustaining daily livelihoods can make even basic tuition costs prohibitive. For many prospective students, especially adult learners, the opportunity cost of stepping away from paid work presents a significant barrier to pursuing higher education. Beyond finances, the responsibilities of work and family life, childcare, eldercare, long working hours compete for adults’ limited time and energy. These situational pressures can substantially reduce their capacity to take on rigorous academic or training commitments. The second one is the perception of career stability, which often leads to a diminished sense of urgency to invest in additional qualifications. Individuals who feel secure in their current job positions may perceive little immediate need to obtain additional qualifications, thereby reducing their motivation to enrol in further education; dispositional barriers, in which personal attitudes such as the belief that one’s career path is already established undermine the perceived value of continued learning. Those in relatively stable, well-paying roles often weigh the potential gains from additional education against existing life responsibilities and may conclude that further study is not worth the time or financial investment.

The significant female representation (72.88%) in the Readiness Program reflects a broader trend of increased female engagement in African education systems. However, this positive development occurs within a complex landscape still shaped by gender disparities, where sociocultural norms, poverty, and limited resources continue to hinder progress despite targeted interventions. Factors such as economic hardship and sociocultural norms create barriers. For example, early marriage and domestic responsibilities can disrupt education for girls. The finding of a lower male participation rate (26.59%) in readiness programs suggests that men are less inclined to seek preparatory programs, this inclination stems from a complex web of intersecting influences. A key factor limiting male participation in preparatory programs is the persistence of traditional gender roles, which often position men as primary providers expected to prioritise immediate income over continued education. This pressure to enter the workforce early reduces the appeal of academic pursuits that delay economic productivity. Such gendered expectations significantly influence educational trajectories, particularly in African contexts. The small percentage of participants (0.53%) who preferred not to disclose their gender reflects broader societal shifts toward greater recognition of gender diversity. As awareness of non-binary and gender-diverse identities grows, some individuals choose not to identify within binary frameworks, signalling a desire for inclusivity and recognition beyond traditional categories.

The predominance of high school graduates (80.57%) in the Readiness Program reflects its core mission to support students transitioning into university through academic bridging interventions. Many high school graduates require targeted preparation to meet the cognitive and social demands of university education. The participation of students with technical or vocational qualifications (7.86%) highlights the growing trend of practically trained individuals seeking academic advancement, aiming to complement their experiential skills with theoretical grounding. Vocational pathways are increasingly viewed as stepping stones to higher education and improved employability. The lower participation of diploma holders (4.24%) is consistent with institutional practices, as most accredited diplomas meet university entry standards and thus reduce the need for additional readiness interventions.

4.2. Reasons to Join University

Table 2 presents the findings about reasons to join university.

The fact that 82% of participants enrolled in the Readiness Program to improve their grades highlights the program’s central role in academic enhancement and university access. The participants view the program as a second chance to qualify for university, addressing previous academic shortcomings or the need to meet competitive admission standards. Participants’ focus on grade improvement is driven by several factors, including competitive university admission processes, scholarship opportunities tied to academic merit, or an understanding that strong grades are crucial for academic success in university. Nearly half (43%) of participants enrolled to pursue specific career goals, underscoring the program’s critical role in career development and planning. The participants view the program as a structured pathway to achieving their career aspirations, particularly in fields that require university qualifications. While vocational education and training (VET) provide essential hands-on skills for immediate employment, higher education is often necessary for long-term career progression and access to advanced professional roles. The substantial proportion of participants (38%) enrolled to enhance their knowledge and skills, reflecting the recognition of lifelong learning as essential in today’s rapidly evolving job markets. This trend highlights that continuous skill development is vital for career advancement, adaptability, and personal growth, with individuals recognising the need to stay relevant in their fields by continuously updating their competencies for professional success and lifelong adaptability. The finding that 16% of participants enrolled in the Readiness Program for personal development highlights the intrinsic value of education beyond academic or career objectives, reflecting the broader motivations of adult learners, who pursue educational opportunities to enhance attributes such as confidence, critical thinking, and general knowledge. In sum, the findings on the reasons for enrolment into the program suggest that the program is designed to bridge academic gaps and support university admission. However, the program also serves broader educational and career-oriented purposes, including academic preparation for university (main reason), career-focused learning for those seeking professional qualifications, skill-building and knowledge enhancement for better university performance and job market competitiveness, and personal development, demonstrating the intrinsic value of education beyond formal qualifications. Such insights highlight the multifaceted role of Readiness Programs, which cater to diverse learner needs and contribute to both individual empowerment and workforce readiness.

4.3. Appropriateness of Program Structure

Table 3 presents findings about the appropriateness of the program’s structure, observing the two indicators of duration of the program and the course content.

The participants show moderate satisfaction with the program’s duration, indicated by a mean score of 3.49. This level of satisfaction suggests varying preferences regarding program duration, reflecting the need for flexibility in learning structures to accommodate diverse student needs. The findings about the relevance of course content indicate that participants generally perceive the course content as relevant to their academic and career goals, with a mean satisfaction score of 3.72, suggesting a strong consensus on the content’s relevance. It is important to align course content with students’ academic and professional aspirations, as the course content significantly influences student satisfaction, particularly when it aligns with their professional development goals.

4.4. Appropriateness of Program Delivery

Table 4 presents findings about the appropriateness of the program’s delivery by observing the variables of delivery methods, tutoring services, learning materials, accessibility to instructors, engagement of class activities, quality of interaction, clarity of explanations, and program administration.

The participants’ general satisfaction with the program’s delivery methods (mean score of 3.70) reflects the benefits of incorporating diversified instructional strategies. The high mean score of 3.75 for tutoring support reflects the effectiveness of this component of the Readiness Program. The finding that learning materials received the lowest satisfaction rating (mean score = 3.20) points to a gap in this area of program delivery. The high mean score of 3.83 for instructor accessibility indicates that students generally perceive their instructors as available and supportive. However, diverse student needs such as learning difficulties or personal responsibilities often require differentiated support strategies. The mean engagement score of 3.77 suggests that students generally find class activities engaging, though individual experiences vary. The high mean score of 4.15 for peer interaction underscores students’ strong appreciation for collaborative learning environments within the program. The mean score of 3.89 for clarity of explanation suggests that instructors are largely perceived as effective in making course content understandable. However, variation in students’ learning styles and prior knowledge requires instructors to employ diverse explanatory strategies including concrete examples, analogies, and interactive questioning to ensure accessibility and comprehension for all learners. A classroom climate that encourages questions and dialogue further enhances clarity and deepens learning. The participants’ satisfaction with program administration (mean score of 3.76) indicates a generally positive perception of how the program is managed.

In sum, the participants perceive the program delivery as appropriate. This suggests that the program’s delivery methods, tutoring services, learning materials, accessibility to instructors, class activities, interaction, explanations, and administration generally meet the needs of most participants. This positive perception contributes to participant satisfaction, engagement, and ultimately, program effectiveness.

4.5. The Burden of Challenges

Table 5 presents the findings about the burden of challenges, which are namely the financial difficulties, time management, lack of access to learning materials, personal responsibilities, technology, and stress.

With 82.2% of participants reporting difficulties related to technology, it is clear that digital access remains a substantial barrier to participation. These challenges ranging from unreliable internet and outdated devices to low digital literacy limit access to course materials and online platforms and hinder effective communication with instructors and peers. With 77.6% of students reporting stress, this emerges as the second most prevalent challenge within the program. Elevated stress levels are known to impair academic performance, reduce motivation and engagement, and negatively affect physical and mental health. Nearly 47% of students reported facing financial difficulties, underscoring the extent to which economic constraints hinder educational access and persistence. A significant portion of students (37.9%) reported difficulties in accessing learning materials, highlighting barriers that stem from financial constraints (e.g., textbook and internet costs), technological limitations (e.g., lack of devices or stable internet), geographic remoteness, and accessibility challenges (e.g., materials not being available in inclusive formats). Access to learning resources is critical for academic success, as these materials are fundamental to knowledge acquisition and meaningful engagement with course content. With 31.8% of participants reporting difficulty managing time, it is evident that time management poses a significant challenge for many students, especially those navigating work, family, and academic responsibilities concurrently. Effective time management is crucial for academic success, particularly among adult and non-traditional learners, as it supports consistent study habits, timely assignment completion, and reduced stress. Conversely, poor time management is associated with increased anxiety, missed deadlines, and even withdrawal from academic programs. With 28.8% of participants reporting difficulty managing personal responsibilities, this challenge reflects a broader pattern seen among adult and non-traditional learners who juggle multiple life roles. Responsibilities such as family care, work obligations, health concerns, and personal commitments often reduce study time, elevate stress, and negatively impact academic outcomes and persistence.

Students in the program carry the burden of challenges stemming from a variety of factors, including academic difficulties, financial constraints, time management issues, technology problems, personal responsibilities, or a combination of these and other challenges. This finding underscores the need for programs to be aware of the various burdens students carry and to provide comprehensive support services to help them overcome these obstacles. Such support might include academic tutoring, financial aid, counselling services, time management workshops, technology assistance, or resources for managing personal responsibilities. Understanding the specific nature and intensity of the challenges faced by students is crucial for developing effective interventions. Challenges impact student motivation, engagement, persistence, and ultimately, program success. Moreover, the high prevalence of stress and technological challenges underscores the need for readiness programs to adopt an Ubuntu-informed approach that fosters communal support networks and peer-based coping strategies, rather than placing the burden of resilience solely on individual students.

4.6. Effectiveness of the Program

The effectiveness of the program is measured by the readiness of the participants to go for university studies. It is established by testing the hypothesis that the Readiness Program has no significant influence on the readiness of the participants to go for university studies.

Table 6 presents the descriptives of the dependent variable (readiness to join university) and the independent variables (duration of the program, relevance of program content, effectiveness of program delivery, resilience to burden of challenges, improved academic skills, improved academic performance, and effective program administration.

In order to test the hypothesis, a regression analysis was performed, the results of which are summarised in

Table 7 (only the variables and

p-values).

1The regression results indicate that several variables significantly influence the dependent variable. Program delivery (Coef. = 0.3529, p < 0.000) has the strongest positive effect, suggesting that improvements in how the program is delivered are highly associated with increased readiness. Improved academic skills (Coef. = 0.1538, p < 0.000) and improved academic performance (Coef. = 0.2978, p < 0.000) are also significant predictors, reinforcing the program’s effectiveness in enhancing student readiness. Relevance of the program content (Coef. = 0.0723, p = 0.009) and duration of the program (Coef. = 0.0526, p = 0.046) show smaller but statistically significant positive effects, indicating that well-structured content and program length contribute to satisfaction. However, resilience to challenges (Coef. = 0.1521, p = 0.161) is not statistically significant, suggesting that this factor does not strongly predict the outcome. The constant term (_cons, p = 0.256) is also insignificant, meaning that without the independent variables, the model does not predict the outcome well. The insignificance of the constant term confirms that the program’s components are essential in shaping students’ readiness for higher education because students do not naturally develop the necessary readiness for university without structured interventions, such as relevant course content, strong program delivery, and academic skill-building. This underscores the crucial role of the readiness program in equipping students with the necessary skills, knowledge, and confidence to transition into higher education successfully. Overall, the findings highlight that duration of the program, program delivery, academic skills, and performance are key drivers of success, while resilience to challenges has a weaker relationship with the outcome.

4.7. Summary of How Research Questions Are Addressed

The findings presented above address the study’s two research questions in the following ways:

Research Question 1: To what extent are the readiness programs effective in the readiness of the participants to go for university studies? The results clearly show that program delivery, improved academic skills, and improved academic performance are statistically significant predictors of student readiness for higher education. The relevance of program content and the duration of the program also contribute positively, though to a smaller extent. These findings demonstrate that readiness programs significantly enhance students’ preparedness for university studies, thereby rejecting the null hypothesis. However, resilience to personal challenges did not significantly predict readiness, suggesting that structured program interventions play a more pivotal role than individual perseverance.

Research Question 2: How can the Ubuntu philosophy be integrated in the readiness programs for effective readiness program delivery in the African context? While the quantitative data primarily assessed program effectiveness, several findings support the relevance of Ubuntu principles. The high levels of satisfaction with peer interaction (mean = 4.15) and engagement in collaborative learning activities highlight the importance of communal learning environments. These elements align with Ubuntu’s emphasis on relational learning and collective support. Moreover, addressing the burden of challenges through structured communal support, rather than relying solely on individual resilience, reflects Ubuntu values. These insights provide a basis for integrating Ubuntu-driven approaches into readiness programs, as further elaborated in the Discussion section.

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Findings in Relation to Literature and Ubuntu

This section interprets the key findings of the study in relation to the existing literature on non-linear education-to-work transitions and readiness programs and considers how these findings align with the principles of the Ubuntu philosophy. The age distribution of participants reflects the non-linear nature of education-to-work transitions, with many students entering the Readiness Program after time in the workforce or with family responsibilities. This finding is consistent with prior studies showing that adult learners often delay higher education due to financial constraints and life circumstances (

Scanlon et al. 2019;

Harrison and Tran 2020;

Stewart et al. 2015;

Cadorin et al. 2017;

Ambrose et al. 2010). Older adults face barriers such as opportunity costs and competing responsibilities (

Gupta 2018;

Walker and Mathebula 2020;

Merriam and Baumgartner 2020;

Boeren 2017;

Schuetze and Slowey 2002). Ubuntu philosophy encourages a communal approach to education, which could help mitigate some of these barriers through community-based support systems.

The strong female representation in the program reflects ongoing trends in African higher education (

Unterhalter et al. 2019,

2022), though gender disparities remain. Early marriage and domestic responsibilities still create barriers for many girls (

Kabubo-Mariara et al. 2021). Conversely, traditional gender roles may discourage men from participating in readiness programs (

Moosa and Bhana 2019,

2020;

Govender and Bhana 2023;

Levtov et al. 2014). The small percentage of students not disclosing gender aligns with emerging recognition of gender diversity (

Hellerstedt et al. 2024). An Ubuntu-informed approach would promote inclusivity and challenge harmful gender norms, supporting equitable access for all learners.

The predominance of high school graduates in the program reflects the need for bridging interventions (

Shay 2015), while the participation of vocational graduates supports the growing permeability between VET and higher education pathways (

Moodie et al. 2019;

McGrath and Powell 2016;

Wheelahan and Moodie 2025). Such bridging aligns with Ubuntu’s emphasis on lifelong learning and communal advancement.

Participants’ reasons for enrolment reflect both academic and personal motivations. The emphasis on improving grades aligns with

Tinto’s (

2017) model of academic preparation. Career goals and lifelong learning motivations are consistent with research by

Super (

1953,

1957),

Moodie et al. (

2019), and

Merriam and Baumgartner (

2020). The desire for personal development also aligns with the literature on lifelong learning (

Merriam and Baumgartner 2020). Ubuntu philosophy supports such holistic development by fostering both individual growth and collective benefit.

Finally, the regression findings are consistent with theoretical perspectives that emphasise the importance of structured educational support in non-linear transitions (

Wignall et al. 2023;

Majola et al. 2024), and they also align with Ubuntu philosophy, which values communal responsibility and structured mentorship in promoting educational success (

Letseka 2013;

Waghid 2014).

5.2. Practical Implications

The results of this study offer several practical implications for the design and delivery of readiness programs in African higher education. First, enhancing program delivery through Ubuntu-driven teaching methods can further strengthen student engagement and preparedness. The high ratings for peer interaction and collaborative learning activities suggest that readiness programs should prioritise dialogical and participatory teaching approaches that foster communal responsibility and peer mentorship.

Second, the importance of improved academic skills and academic performance highlights the need for readiness programs to integrate structured academic support with Ubuntu values of shared growth and collective success. This could include community-based learning circles, peer-assisted tutoring, and storytelling-based problem-solving activities that align with indigenous knowledge systems.

Third, addressing student challenges through communal rather than individualised interventions are critical. Given the high levels of stress and technological challenges reported, readiness programs should embed Ubuntu-inspired peer support networks and intergenerational mentorship structures to provide holistic support.

While this paper has argued for the integration of Ubuntu philosophy in readiness programs and early peer learning, it is important to clarify how this philosophical orientation contributes to preparing learners for current and emerging job markets. A fair concern is whether Ubuntu, as a relational and moral framework, can be operationalised in practical, skills-based employment contexts especially within sectors that prioritise technical expertise or formal qualifications. However, Ubuntu should not be viewed as a substitute for specialised education in professions such as medicine or engineering, where credentialism and regulated learning pathways remain essential. Rather, Ubuntu complements these technical pathways by foregrounding values such as empathy, cooperation, and ethical responsibility, capacities that are now increasingly recognised as essential across both traditional and sunrise sectors, including green jobs and AI. For instance, green energy projects that rely on community participation and sustainable resource use benefit from Ubuntu’s ethos of shared stewardship and mutual accountability. Likewise, in AI and data-driven industries, Ubuntu offers a counterbalance to technocratic decision-making by emphasising human dignity, contextual understanding, and inclusivity in algorithmic applications and design processes. Moreover, in non-linear education-to-work trajectories where skills acquisition often occurs outside traditional academic routes such as through open learning platforms, micro-credentials, or informal apprenticeships, Ubuntu plays a crucial role in shaping the social fabric of learning. It fosters peer-to-peer mentorship, collective problem-solving, and a sense of purpose that extends beyond individual gain. By integrating Ubuntu into readiness programs, institutions can cultivate not only technically skilled individuals but also ethically grounded and socially responsive citizens, whose work contributes meaningfully to the communities and ecosystems they serve. In this way, Ubuntu is not only relevant but necessary for shaping 21st-century labour readiness. It shifts the question from “what a person knows” to “how a person lives and relates” a shift that is vital in an era defined by uncertainty, complexity, and the urgent need for human-centred development.

5.3. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the theoretical discourse on non-linear education-to-work transitions by demonstrating how Ubuntu philosophy can complement existing transition theories. Whereas dominant models often foreground individual agency, this study highlights the value of relational ethics and communal belonging in shaping successful transitions. Integrating Ubuntu into readiness programs not only enhances their cultural relevance but also offers a counter-narrative to the competitive individualism prevalent in many educational models.

Furthermore, the study extends the literature on readiness programs in African contexts, where empirical research remains limited (

Mabokela and Mlambo 2017;

Le Grange et al. 2020). By foregrounding Ubuntu as both a philosophical and practical framework, this research contributes to the ongoing project of decolonising African higher education and aligning pedagogical practices with African epistemologies.

5.4. Limitations of the Study

While the study offers valuable insights, certain limitations must be acknowledged. The use of self-reported data introduces potential biases related to social desirability and subjective perceptions. Additionally, the study was conducted within a single institutional context, which may limit the generalisability of the findings to other settings. The cross-sectional design captures readiness at a single point in time, without assessing long-term impacts such as persistence and graduation outcomes. Finally, while the integration of Ubuntu philosophy was explored through interpretation of quantitative results, further qualitative research could provide deeper insights into how Ubuntu principles are experienced and enacted within readiness programs.

5.5. Directions for Future Research

Future research should explore the longitudinal effects of readiness programs on student outcomes, including academic persistence, graduation rates, and employment trajectories. Comparative studies across different institutional and national contexts in Africa would help to further validate the applicability of Ubuntu-informed readiness models. Moreover, qualitative studies involving student and educator perspectives could enrich understanding of how Ubuntu principles can be operationalised in program design and delivery. As African universities continue to engage in curriculum transformation and decolonisation efforts, integrating Ubuntu into readiness programs offers a promising avenue for creating more inclusive and contextually relevant pathways to higher education.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

The findings of this study highlight the critical role of readiness programs in preparing students for higher education, with program delivery, academic skills development, and academic performance emerging as the strongest predictors of readiness. While program content and duration contribute positively, resilience to challenges appears to have a weaker influence, suggesting that readiness is more effectively cultivated through structured interventions rather than individual perseverance alone. These insights align with the African Ubuntu philosophy, which emphasises collaborative learning, mutual support, and shared responsibility in education.

This study’s findings show that readiness programs which foster peer interaction, cooperative learning, and structured academic support are more effective in preparing students for higher education. Moreover, the high levels of stress and technological challenges reported by students highlight the need for readiness programs to provide communal support structures in line with Ubuntu principles. The integration of Ubuntu into readiness programs ensures that education is not just a means of economic mobility but also a tool for community upliftment and social justice. This integration offers a transformative approach that aligns education with Africa’s cultural values, social realities, and long-term aspirations for inclusive growth and development.

In order for universities and policymakers to enhance the effectiveness of readiness programs, strengthen student preparedness for higher education, and align learning practices with the Ubuntu philosophy for a more inclusive, community-driven approach to academic success, the following are recommendations:

Enhancing program delivery through Ubuntu-driven teaching methods. Readiness programs should incorporate peer mentoring, cooperative learning, and community engagement to foster a sense of shared responsibility in learning. Dialogical and participatory teaching approaches should be prioritised to ensure that students learn not only from instructors but also from their peers, making program delivery both efficient and culturally relevant. This is supported by the study’s finding that program delivery is a key predictor of readiness.

Fostering academic skills development as a community-driven effort. Academic skills development should be structured around collaborative support networks, where students engage in peer-assisted learning, intergenerational mentorship, and African storytelling-based problem-solving. Readiness programs should emphasise knowledge co-creation through relationships and shared experiences, reinforcing Ubuntu’s communal approach to education. The study shows that improved academic skills strongly influence student readiness.

Broadening the focus beyond academic performance. Readiness programs should balance academic instruction with character-building, ethical leadership, and emotional intelligence development to produce graduates who are both intellectually competent and socially responsible. Universities should integrate Ubuntu’s values of integrity, collective responsibility, and personal growth into readiness programs to prepare students for life beyond university. This responds to the finding that resilience alone was not a strong predictor of readiness, underscoring the importance of communal support and holistic development.

Ensuring culturally relevant and contextualised course content. Readiness programs should align curriculum content with students’ lived experiences and African contexts, incorporating indigenous knowledge systems, storytelling methods, and real-world problem-solving activities. Curriculum indigenisation should be a key priority to ensure relevance and meaningful engagement with students. The positive influence of program content on readiness supports this recommendation.

Optimising program duration for maximum impact. Readiness programs should allow sufficient time for communal reflection, mentorship, and experiential learning to strengthen student preparedness for university. The structure of programs should be designed to ensure holistic student engagement rather than rushed academic preparation. Findings show that program duration contributes positively to readiness when appropriately structured.

Prioritising structured communal support over individual resilience. Readiness programs should not rely solely on students’ personal resilience, as Ubuntu emphasises that resilience is best cultivated through communal support. Institutions should integrate Ubuntu-based peer support groups, mentorship by community elders, and participatory decision-making processes to provide structured emotional and academic support. This recommendation responds directly to the finding that resilience alone was not a significant predictor of readiness.

Strengthening readiness programs through Ubuntu-driven policies. Since students do not naturally develop university readiness without structured interventions, readiness programs should be designed to integrate Ubuntu’s principles of interconnectedness and communal learning. Institutions should establish robust support networks, mentorship structures, and community engagement initiatives as essential components of the transition process.

Institutionalising Ubuntu to strengthen program effectiveness. Universities should adopt Ubuntu-driven strategies to enhance the effectiveness of readiness programs, ensuring that education is framed around cooperative learning, shared responsibility, and holistic development. Structured community support systems should be embedded into readiness programs to improve student outcomes and reinforce the values of community, ethics, and shared growth in African higher education.