Paths to Self-Employment: The Role of Childbirth Timing in Shaping Entrepreneurial Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Motivational Differences Between Mothers and Women Without Children

2.2. Self-Employment Timing Relative to Fertility

2.3. Self-Employment, Fertility, and Performance

2.4. The Israeli Context

3. Data and Variables

Variables

4. Methods

5. Results

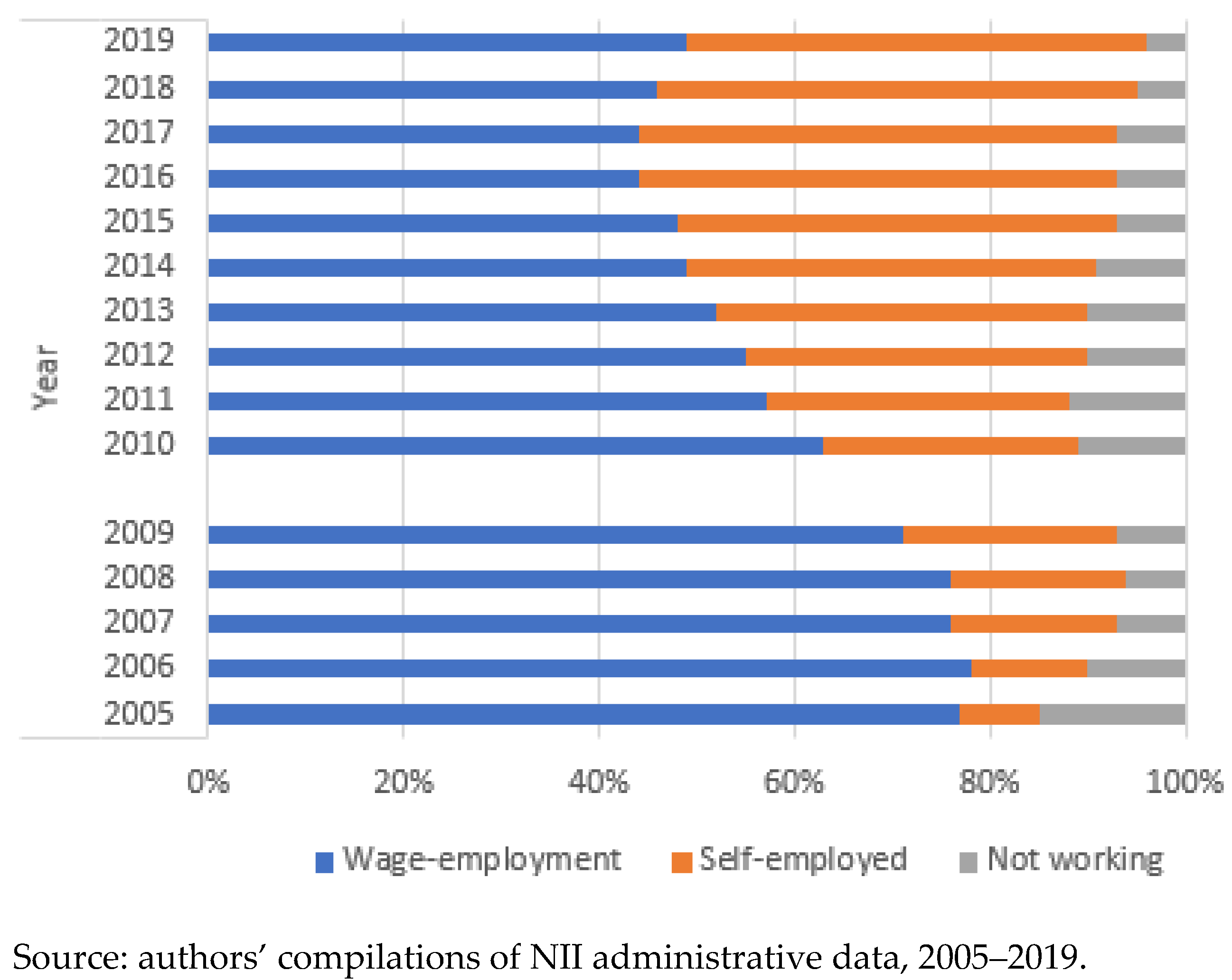

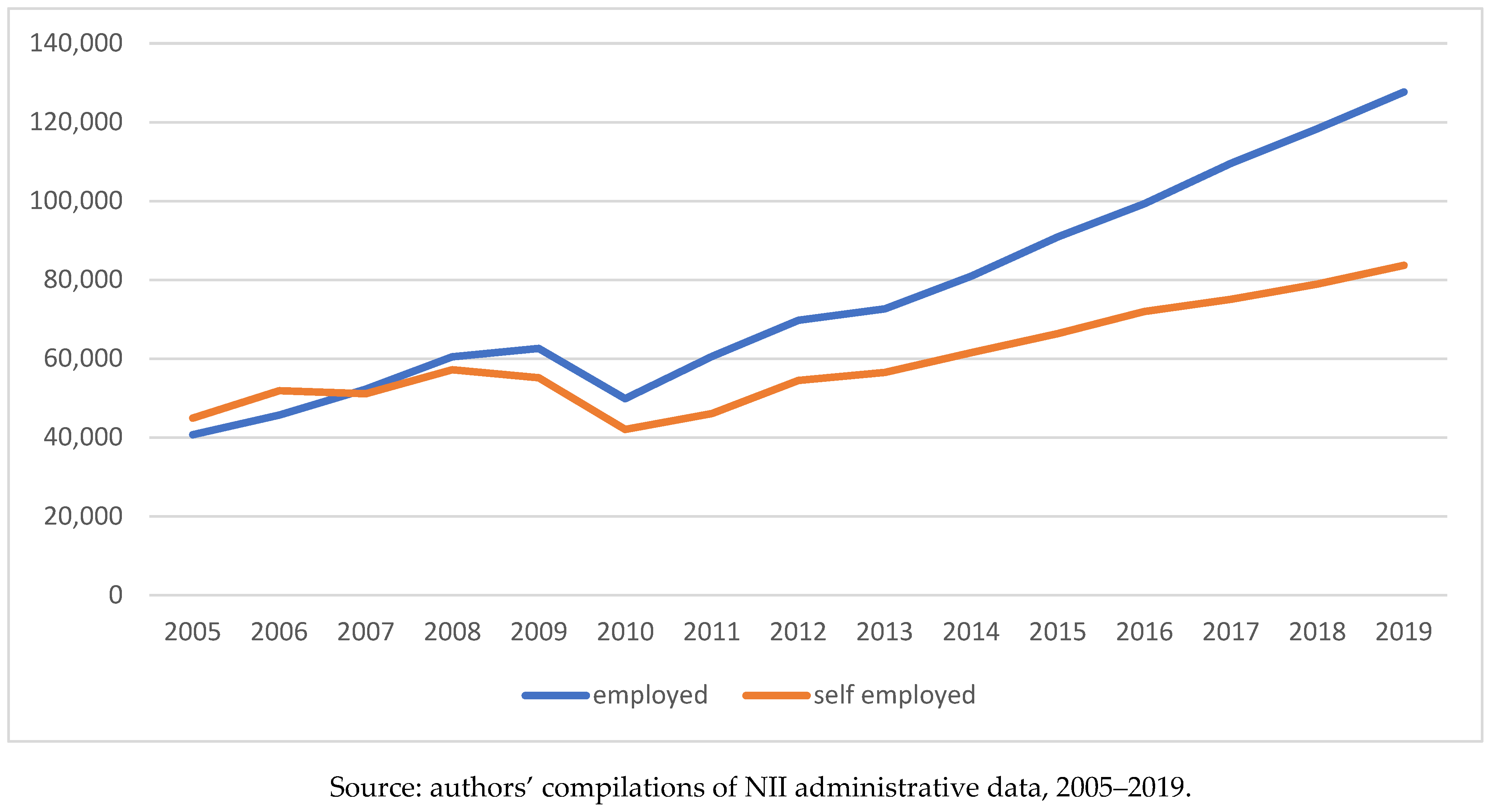

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Logistic Regressions: Self-Employment and Ownership of Small Business

5.3. OLS Regression: Self-Employment Duration

5.4. Income

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In Israel, fertility rates vary substantially across groups, with ultra-Orthodox Jewish women averaging 6.2 children and Muslim women 2.4 (CBS 2022). |

| 2 | In contrast, a report made by the Israeli Ministry on finance in 2021 (Israeli Ministry of Finance 2021) argues that the Motherhood Penalty in Israel is as much as 28% a decade after the first childbirth. Most of this gap, however, is explained by mothers switching to part-time employment. https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/dynamiccollectorresultitem/periodic-review-13122021/he/weekly_economic_review_periodic-review-13122021.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2025) (In Hebrew). |

| 3 | These findings pertain to a single cohort of first-time mothers who gave birth in 2010 and should, therefore, be interpreted in light of the specific temporal and policy context shaping their employment trajectories. |

| 4 | We agree that the conditions used to define self-employment may, in some cases, also characterize forms of dependent employment (e.g., part-time or low-wage salaried work). However, salaried employment in Israel is not contingent on meeting these minimum income or hour thresholds. In contrast, the National Insurance Institute uses these criteria to identify active self-employed contributors and to differentiate them from those who are only marginally or occasionally self-employed. |

| 5 | See: https://www.btl.gov.il/English%20Homepage/Insurance/National%20Insurance/Detailsoftypes/SelfEmployedPerson/Pages/default.aspx/ (accessed on 24 February 2025). |

| 6 | Price level adjustments were not considered since throughout the period from 2005–2019, the price index in Israel rose by less than 5%. |

| 7 | We do not take into account spacing between children, as the effect of these factors are beyond the scope of this paper. |

| 8 | In the Israeli context, it is particularly important to control for single motherhood. Unlike in many European countries, cohabitation outside of marriage is uncommon and single mothers typically do not reside with a partner. This makes single motherhood a meaningful indicator of the absence of both financial and caregiving support from a co-residing partner. |

| 9 | A partner’s income and employment status may influence the decision to enter self-employment by providing financial security or constraints. However, our focus is not on explaining entry into self-employment, but rather on how the timing of self-employment—before versus after childbirth—relates to subsequent business outcomes among women who were all self-employed at some point during the observation period. In any case, in Israel, 89% of partnered men with children are employed (CBS 2022), making variations in the partner employment status relatively limited and thus less likely to account for differences in the timing of self-employment among this population. |

| 10 | We combine wage-employed and non-employed women into a single reference group to maintain a consistent analytic contrast between those who entered self-employment and those who did not. This approach preserves the focus of this study on the timing of entry and business outcomes, rather than on the labor market status at the baseline. |

| 11 | That is to say, the women coded with 1 for the second regression are a proper sub-group of those coded with 1 in the first. |

| 12 | It is also possible that as highly educated women tend to be matched with highly educated men, such women may benefit from a higher household income. That assortative matching is particularly present in Israel is documented by Kaplan and Herbst (2015) and by Stier and Shavit (2003). |

| 13 | The interpretation of this coefficient for all women, in contrast to that of the self-employed, needs to be regarded with caution. Specifically, it is likely that the seemingly high marginal return to additional employment months is actually representing a discrete income difference between women who hold regular all-year jobs and those that work in precarious forms of employment. |

References

- Acs, Zoltan. 2006. How is entrepreneurship good for economic growth? Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization 1: 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba-Ramirez, Alfonso. 1994. Self-employment in the midst of unemployment: The case of Spain and the United States. Applied Economics 26: 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, Howard E., and Roger Waldinger. 1990. Ethnicity and entrepreneurship. Annual Review of Sociology 16: 111–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, Raphael, and Eitan Muller. 1995. ‘PUSH’ and ‘PULL’ entrepreneurship. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 12: 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthias, Floya. 2012. Transnational mobilities, migration research and intersectionality. Nordic Journal of Migration Research 2: 102–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baikovich, Avital, Varda Wasserman, and Talia Pfefferman. 2022. ‘Evolution from the inside out’: Revisiting the impact of (re) productive resistance among ultra-orthodox female entrepreneurs. Organization Studies 43: 1247–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Ted, and Friederike Welter. 2020. Contextualizing Entrepreneurship Theory. London: Routledge, p. 188. [Google Scholar]

- Bental, Benjamin, Vered Kraus, and Yuval Yonay. 2017. Ethnic and gender earning gaps in a liberalized economy: The case of Israel. Social Science Research 63: 209–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, Matthias, and Bruno S. Frey. 2008. Being independent is a great thing: Subjective evaluations of self-employment and hierarchy. Economica 75: 362–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghammer, Caroline. 2014. The return of the male breadwinner model? Educational effects on parents’ work arrangements in Austria, 1980–2009. Work, Employment and Society 28: 611–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, Laura, Johannes Huinink, and Richard A. Settersten Jr. 2019. The life course cube: A tool for studying lives. Advances in Life Course Research 41: 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birenbaum-Carmeli, Daphna. 2016. Thirty-five years of assisted reproductive technologies in Israel. Reproductive Biomedicine & Society Online 2: 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzon, Rossella, and Annalisa Murgia. 2021. Work-family conflict in Europe: A focus on the heterogeneity of self-employment. Community, Work & Family 24: 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, Candida G., Anne De Bruin, and Friederike Welter. 2009. A gender-aware framework for women’s entrepreneurship. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship 1: 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budig, Michelle J. 2006. Intersections on the road to self-employment: Gender, family and occupational class. Social Forces 84: 2223–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budig, Michelle J., Vered Kraus, and Asaf Levanon. 2023. Israeli ethno-religious differences in motherhood penalties on employment and earnings. Gender & Society 37: 208–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, Andrew E., Felix R. Fitzroy, and Michael A. Nolan. 2002. Self-employment wealth and job creation: The roles of gender, non-pecuniary motivation, and entrepreneurial ability. Small Business Economics 19: 255–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, Deborah. 1996. Two paths to self-employment? Women’s and men’s self-employment in the United States, 1980. Work and Occupations 23: 26–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, Marylyn, and Joanne Duberley. 2013. Time triage: Exploring the temporal strategies that support entrepreneurship and motherhood. Time & Society 22: 92–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellaneta, Francesco, Raffaele Conti, and Olenka Kacperczyk. 2020. The (un)intended consequences of institutions lowering barriers to entrepreneurship: The impact on female workers. Strategic Management Journal 41: 1274–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Bureau of Statistics (Israel). 2019. Statistical Abstract of Israel 2019. Jerusalem: Central Bureau of Statistics (Israel). [Google Scholar]

- Central Bureau of Statistics (Israel). 2022. Statistical Abstract of Israel 2022. Jerusalem: Central Bureau of Statistics (Israel). [Google Scholar]

- Chudner, Irit, Avi Shnider, Omer Gluzman, Hadas Keidar, and Motti Haimi. 2025. Gender Perspectives on Self-Employment Among Israeli Family Physicians: A Qualitative Study. Social Sciences 14: 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conen, Wieteke, and Joop Schippers, eds. 2019. Self-Employment as Precarious Work: A European Perspective. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Correll, Shelley J., Stephen Benard, and In Paik. 2007. Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty? American Journal of Sociology 112: 1297–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowling, Michael Leith, and Mark Wooden. 2021. Does solo self-employment serve as a ‘stepping stone’ to employership? Labour Economics 68: 101942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, Punita Bhatt, and Robert Gailey. 2012. Empowering women through social entrepreneurship: Case study of a women’s cooperative in India. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36: 569–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekert-Jaffe, Olivia, and Haya Stier. 2009. Normative or economic behavior? Fertility and women’s employment in Israel. Social Science Research 38: 644–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essers, Caroline, and Yvonne Benschop. 2009. Muslim businesswomen doing boundary work: The negotiation of Islam, gender and ethnicity within entrepreneurial contexts. Human Relations 62: 403–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrín, Mónica. 2021. Self-employed women in Europe: Lack of opportunity or forced by necessity? Work, Employment and Society 37: 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogiel-Bijaoui, Sylvie. 2016. Navigating Gender Inequality in Israel: The Challenges of Feminism. In Handbook of Israel: Major Debates. Edited by Eliezer Ben-Rafael, Julius H. Schoeps, Yitzhak Sternberg and Olaf Glöckner. Berlin: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, pp. 423–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, Menachem. 1991. The Haredi (Ultra-Orthodox) Society: Sources, Trends and Processes. Jerusalem: The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, vol. 1, pp. 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, Hadas. 2016. Gender Gaps in the Labor Market: Wage and Occupational Segregation. In State of the Nation Report: Society, Economy and Policy in Israel. Edited by A. A. Adar and A. B. Sela. Washington, DC: World Bank Group, pp. 61–100. [Google Scholar]

- Gafni, Dalit, and Erez Siniver. 2015. Is there a motherhood wage penalty for highly skilled women? The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 15: 1353–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomin, Olivier, Frank Janssen, Jean-Luc Guyot, and Olivier Lohest. 2023. Opportunity and/or Necessity Entrepreneurship? The Impact of the Socio-Economic Characteristics of Entrepreneurs. Sustainability 15: 10786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffee, Robert, and Richard Scase. 1983. Business ownership and women’s subordination: A preliminary study of female proprietors. The Sociological Review 31: 625–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, William H. 2018. Econometric Analysis, 8th ed. London: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, Barton H. 2000. Does entrepreneurship pay? An empirical analysis of the returns to self-employment. Journal of Political Economy 108: 604–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashiloni-Dolev, Yael. 2018. The effect of Jewish-Israeli family ideology on policy regarding reproductive technologies. In Sociology of Health & Illness: Issues in Jewish and Israeli Family Ideology. Edited by Hagai Boas, Yael Hashiloni-Dolev, Shai J. Lavi, Dani Filc and Nadav Davidovitch. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 265–79. [Google Scholar]

- Henley, Andrew. 2023. Is rising self-employment associated with material deprivation in the UK? Work, Employment and Society 37: 1395–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst-Debby, Anat, and Noa Achouche. 2023. Double jeopardy: Gendered social policy for two risky life periods in six welfare state contexts. Women’s Studies International Forum 100: 102814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbrecht, Margo, and Donna S. Lero. 2014. Self-employment and family life: Constructing work–life balance when you’re ‘always on’. Community, Work & Family 17: 20–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Karen D. 2006. Exploring motivation and success among Canadian women entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 19: 107–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyytinen, Ari, and Olli-Pekka Ruuskanen. 2007. Time use of the self-employed. Kyklos 60: 105–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israeli Ministry of Finance. 2021. The Motherhood Penalty in the Israeli Labor Market. Available online: https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/dynamiccollectorresultitem/periodic-review-13122021/he/weekly_economic_review_periodic-review-13122021.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2025). (In Hebrew)

- Jafari-Sadeghi, Vahid. 2020. The motivational factors of business venturing: Opportunity versus necessity? A gendered perspective on European countries. Journal of Business Research 113: 279–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joona, Pernilla Andersson. 2018. How does motherhood affect self-employment performance? Small Business Economics 50: 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, HeeJung, Balagopal Vissa, and Michael Pich. 2017. How do entrepreneurial founding teams allocate task positions? Academy of Management Journal 60: 264–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacperczyk, Olenka, Peter Younkin, and Vera Rocha. 2023. Do employees work less for female leaders? A multi-method study of entrepreneurial firms. Organization Science 34: 1111–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg, Arne L., and Steven P. Vallas, eds. 2017. Precarious Work. Leeds: Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Kanji, Shireen, and Natalia Vershinina. 2024. Gendered transitions to self-employment and business ownership: A linked-lives perspective. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 36: 922–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Amit, and Anat Herbst. 2015. Stratified patterns of divorce: Earnings, education, and gender. Demographic Research 32: 949–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kark, Ronit, and Ronit Waismel-Manor. 2016. Women in management in Israel. In Women in Management Worldwide. London: Gower, pp. 297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, Vered, and Yuval P. Yonay. 2018. Facing Barriers: Palestinian Women in a Jewish-Dominated Labor Market. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leighton, Patricia. 2016. Professional self-employment, new power and the sharing economy: Some cautionary tales from Uber. Journal of Management & Organization 22: 859–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Katherine. 2019. Do American mothers use self-employment as a flexible work alternative? Review of Economics of the Household 17: 805–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, Karen V. 2001. Female self-employment and demand for flexible, nonstandard work schedules. Economic Inquiry 39: 214–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurie, Lilach, and Haya Stier. 2022. Marital status and gender inequality in household income among older adults in Israel: Changes over time. Social Indicators Research 159: 801–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malach, Gilad, and Lee Cahaner. 2017. Elements of Modern Life or ‘Modern Ultra-Orthodoxy’? Numerical Assessment of Modernization Processes in Ultra-Orthodox Society. Democratic Culture 17: 19–51. [Google Scholar]

- Malach, Gilad, and Lee Cahaner. 2019. 2019 Statistical Report on Ultra-Orthodox Society in Israel: Highlights. Jerusalem: The Israel Democracy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel, Hadas, and Moshe Semyonov. 2006. A welfare state paradox: State interventions and women’s employment opportunities in 22 countries. American Journal of Sociology 111: 1910–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiarena, Alona. 2020. Re-examining the opportunity pull and necessity push debate: Contexts and abilities. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 32: 531–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuri, Meytal, Michal Raz-Rotem, and Helena Desivilya Syna. 2025. Why should I be an entrepreneur? A feminist perspective on the drivers and motivations of Israeli women entrepreneurs. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysiak, Anna, and Monika Mynarska. 2020. Self-employment as a work-and-family reconciliation strategy? Evidence from Poland. Advances in Life Course Research 45: 100329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moen, Phyllis. 2003. Linked lives: Dual careers, gender, and the contingent life course. Social Dynamics of the Life Course: Transitions, Institutions, and Interrelations 1: 237–58. [Google Scholar]

- Moen, Phyllis. 2011. From ‘work–family’ to the ‘gendered life course’ and ‘fit’: Five challenges to the field. Community, Work & Family 14: 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, Walter, and Richard Arum. 2004. Self-employment dynamics in advanced economies. In The Reemergence of Self-Employment: A Comparative Study of Self-Employment Dynamics and Social Inequality. New York: JSTOR, pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Noseleit, Florian. 2014. Female self-employment and children. Small Business Economics 43: 549–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2018. Parental Leave Systems. OECD Family Database. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/PF2_1_Parental_leave_systems.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- OECD. 2019a. Society at a Glance 2019. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available online: http://oe.cd/sag (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- OECD. 2019b. Child Allowance. OECD Family Database. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/PF3_4_Childcare_support.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- OECD. 2020. Is Child Care Affordable? OECD Family Database. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/els/family/OECD-Is-Childcare-Affordable.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- OECD. 2022. Gender Wage Gap (Indicator). Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2023a. Fertility Rates (Indicator). Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2023b. Self-Employment Rate (Indicator). Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okun, Barbara S. 2016. An investigation of the unexpectedly high fertility of secular, native-born Jews in Israel. Population Studies 70: 239–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okun, Barbara S. 2017. Religiosity and fertility: Jews in Israel. European Journal of Population 33: 475–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osowska, Renata. 2016. The development of entrepreneurial culture in a transition economy: An empirical model discussion. In Contemporary Entrepreneurship: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Innovation and Growth. Cham: Springer, pp. 259–73. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, Carlianne, Heather Stephens, and Amanda Weinstein. 2016. Where are all the self-employed women? Push and pull factors influencing female labor market decisions. Small Business Economics 46: 365–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pines, Ayala Malach, Miri Lerner, and Dafna Schwartz. 2010. Gender differences in entrepreneurship. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 29: 186–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raz, Aviad E., and Gavan Tzruya. 2018. Doing gender in segregated and assimilative organizations: Ultra-Orthodox Jewish women in the Israeli high-tech labour market. Gender, Work & Organization 25: 361–78. [Google Scholar]

- Redmond, Janice, Elizabeth Anne Walker, and Jacquie Hutchinson. 2017. Self-employment: Is it a long-term financial strategy for women? Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 36: 362–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Martí, Andrea, Ana Tur Porcar, and Alicia Mas-Tur. 2015. Linking female entrepreneurs’ motivation to business survival. Journal of Business Research 68: 810–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindova, Violina, Daved Barry, and David J. Ketchen Jr. 2009. Entrepreneuring as emancipation. Academy of Management Review 34: 477–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rønsen, Marit. 2014. Children and family: A barrier or an incentive to female self-employment in Norway? International Labour Review 153: 337–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybczynski, Kate. 2015. What drives self-employment survival for women and men? Evidence from Canada. Journal of Labor Research 36: 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa’ar, Amalia. 2017. The gender contract under neoliberalism: Palestinian-Israeli women’s labor force participation. Feminist Economics 23: 54–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stier, Haya, and Yossi Shavit. 2003. Two decades of educational intermarriage in Israel. In Who Marries Whom? Educational Systems as Marriage Markets in Modern Societies. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 315–30. [Google Scholar]

- Thébaud, Sarah. 2016. Passing up the job: The role of gendered organizations and families in the entrepreneurial career process. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 40: 269–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verduijn, Karen, and Caroline Essers. 2013. Questioning dominant entrepreneurship assumptions: The case of female ethnic minority entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 25: 612–30. [Google Scholar]

- Vosko, Leah F., and Nancy Zukewich. 2006. Precarious by choice? Gender and self-employment. In Precarious Employment: Understanding Labour Market Insecurity in Canada. Edited by Leah F. Vosko. New York: JSTOR, pp. 67–89. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Elizabeth A., and Beverley J. Webster. 2007. Gender, age and self-employment: Some things change, some stay the same. Women in Management Review 22: 122–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, Sarah. 2015. Dimensions of precariousness in an emerging sector of self-employment: A study of self-employed nurses. Gender, Work & Organization 22: 221–36. [Google Scholar]

- Weinreb, Alex, Dov Chernichovsky, and Aviv Brill. 2018. Israel’s exceptional fertility. In State of the Nation Report: Society, Economy and Policy in Israel 2018. Edited by Alex Weinreb. Jerusalem: The Taub Center, pp. 1–25. Available online: https://www.taubcenter.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/exceptionalfertilityeng.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Wellington, Alison J. 2006. Self-employment: The new solution for balancing family and career? Labour Economics 13: 357–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Jonas, and Karel Neels. 2019. Does mothers’ parental leave uptake stimulate continued employment and family formation? Evidence for Belgium. Social Sciences 8: 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonay, Yuval, and Vered Kraus. 2013. Ethnicity, gender, and exclusion: Which occupations are open to Israeli Palestinian women? In Palestinians in the Israeli Labor Market: A Multi-Disciplinary Approach. Edited by Yuval Yonay and Vered Kraus. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 87–109. [Google Scholar]

| All Women | Self-Employment Before Childbirth | Self-Employment After Childbirth | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-employed | 32.9% | 66.1% | |

| Self-employed with small business | 11.4% | 12% | 11.1% |

| Employed (both self-employed and wage-employed) | 58.8% | 50% | 63.1% |

| Average Yearly Income | 62,920 ILS | 69,386 ILS | 59,748 ILS |

| (Std deviation) | (74,824) | (81,020) | (71,375) |

| Age (in 2005) | 25 | 27 | 24 |

| (Std deviation) | (4.7) | (5.0) | (4.6) |

| Number of children (in 2019) | 2.7 | 2.4 | 2.8 |

| (Std deviation) | (1.1) | (0.9) | (1.1) |

| Palestinian | 4.3% | 3.6% | 4.6% |

| Ultra-Orthodox | 5% | 1.2% | 6.8% |

| Immigrant | 14.1% | 12.8% | 14.6% |

| Single parent | 8.2% | 12.2% | 6.3% |

| Receive disability allowance | 0.1% | 0.01% | 0.01% |

| Academic % (B.A) in 2019 | 52.5% | 48.9% | 54.2% |

| Periphery | 22.1% | 19.4% | 23.5% |

| N | 73,141 | 24,074 | 49,067 |

| Self-Employment | Self-Employed, Small Business | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Odds Ratio | Coefficient | Odds Ratio | |

| Self-employment before fertility | 0.11 ** | 1.12 | −0.65 *** | 0.52 |

| (0.06) | (0.10) | |||

| Number of children | 0.29 *** | 1.34 | −0.06 * | 0.94 |

| (0.02) | (0.03) | |||

| Age | 0.06 *** | 1.06 | 0.04 *** | 1.04 |

| (0.00) | (0.01) | |||

| Palestinian | −0.33 *** | 0.72 | −0.96 *** | 0.98 |

| (0.13) | (0.26) | |||

| Immigrant | 0.21 *** | 1.23 | 0.09 | 1.09 |

| (0.07) | (0.13) | |||

| Ultra-Orthodox | 0.09 | 1.10 | −0.44 ** | 0.64 |

| (0.12) | (0.22) | |||

| Single parent | −0.22 *** | 0.80 | −0.18 ** | 0.83 |

| (0.06) | (0.09) | |||

| Disability allowance | 0.19 | 1.21 | 0.35 | 1.42 |

| (0.17) | (0.27) | |||

| Periphery | −0.02 | 0.98 | 0.06 | 1.06 |

| (0.05) | (0.09) | |||

| Academic (at least B.A) | −0.34 *** | 0.71 | 0.67 *** | 1.95 |

| (0.05) | (0.09) | |||

| Constant | −2.78 *** | 0.06 | −4.77 *** | 0.008 |

| (0.14) | (0.23) | |||

| Chi2 | 828.99 | 154.13 | ||

| N | 44,193 | 44,193 | ||

| All Women | Self-Employment Before First Birth | Self-Employment After First Birth | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Self-employment before fertility | 0.41 *** | ||

| (0.09) | |||

| Child 1 (2+ the omitted categories) | −0.11 | 0.01 | −0.21 |

| (0.14) | (0.27) | (0.17) | |

| Age | 0.03 ** | 0.02 | 0.04 *** |

| (0.01) | (0.02) | (0.01) | |

| Palestinian | −0.66 *** | −1.49 *** | −0.34 * |

| (0.2) | (0.44) | (0.2) | |

| Immigrant | 0.18 * | 0.43 * | 0.08 |

| (0.11) | (0.25) | (0.12) | |

| Ultra-Orthodox | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.18 |

| (0.18) | (0.74) | (0.17) | |

| Single parent | −0.28 *** | −0.41 * | −0.12 |

| (0.12) | (0.22) | (0.14) | |

| Disability allowance | 0.12 | 0.28 | 0.04 |

| (0.31) | (0.62) | (0.34) | |

| Periphery | −0.19 ** | −0.23 | −0.14 |

| (0.09) | (0.21) | (0.1) | |

| Academic (B.A) | −0.43 *** | −0.67 *** | −0.29 *** |

| (0.08) | (0.17) | (0.09) | |

| Number of working months a year | 0.07 *** | 0.10 *** | 0.06 *** |

| (0.01) | (0.02) | (0.01) | |

| By quantiles (the first quantile is the omitted category) | |||

| 2nd quantile | −0.01 | 0.48 | −0.23 * |

| (0.12) | (0.3) | (0.13) | |

| 3rd quantile | −0.05 | 0.51* | −0.30 ** |

| (0.13) | (0.3) | (0.13) | |

| 4th quantile | −0.40 *** | −0.46 | −0.31 ** |

| (0.13) | (0.31) | (0.14) | |

| 5th quantile | −0.85 *** | −0.73 ** | −0.84 *** |

| (0.14) | (0.32) | (0.15) | |

| Constant | 2.40 *** | 2.83 *** | 2.26 *** |

| (0.42) | (0.86) | (0.47) | |

| N | 4777 | 3211 | 1566 |

| Total Post-Natal Income: All Women | Self-Employment Post-Natal Income: All Women | Total Post-Natal Income: Women Who Had Pre-Natal Self-Employment Experience | Total Post-Natal Income: Women Who Had No Pre-Natal Self-Employment Experience | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Self-employment before fertility | −0.22 *** | −0.04 | ||

| (0.04) | (0.05) | |||

| Years of self-employment | 0.04 *** | 0.01 * | 0.03 *** | 0.05 *** |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | |

| Number of working months per year | 0.52 *** | 0.16 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.51 *** |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Child 1 (base: 2+ children | −0.28 *** | −0.29 *** | −0.42 *** | −0.22 *** |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.04) | (0.03) | |

| Age | 0.01 * | 0.04 *** | 0.01 * | 0 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Palestinian | −0.85 *** | −0.23 *** | −0.79 *** | −0.88 *** |

| (0.09) | (0.11) | (0.18) | (0.10) | |

| Immigrant | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.32 *** | −0.11 ** |

| (0.05) | (0.06) | (0.10) | (0.06) | |

| Ultra-Orthodox | −0.07 | 0.37 *** | 0.11 | −0.09 |

| (0.06) | (0.10) | (0.30) | (0.08) | |

| Lone parent | −0.03 | −0.09 ** | −0.04 | −0.04 |

| (0.04) | (0.05) | (0.06) | (0.06) | |

| Receive disabled allowance | −0.33 *** | −0.52 *** | −0.16 * | −0.38 ** |

| (0.13) | (0.04) | (0.21) | (0.16) | |

| Periphery | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.08 | −0.04 |

| (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.07) | (0.04) | |

| Academic (B.A) | 0.37 *** | −0.04 | 0.36 *** | 0.37 *** |

| (0.03) | (0.04) | (0.07) | (0.04) | |

| Constant | 4.84 *** | 7.37 *** | 4.38 *** | 4.89 *** |

| (0.11) | (0.13) | (0.19) | (0.13) | |

| chi2 | 43,504.38 | 1493.81 | 29,602.2 | 14,012.08 |

| N | 44,193 | 21,593 | 29,786 | 14,407 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Achouche, N.; Endeweld, M.; Bental, B. Paths to Self-Employment: The Role of Childbirth Timing in Shaping Entrepreneurial Outcomes. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060389

Achouche N, Endeweld M, Bental B. Paths to Self-Employment: The Role of Childbirth Timing in Shaping Entrepreneurial Outcomes. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(6):389. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060389

Chicago/Turabian StyleAchouche, Noa, Miri Endeweld, and Benjamin Bental. 2025. "Paths to Self-Employment: The Role of Childbirth Timing in Shaping Entrepreneurial Outcomes" Social Sciences 14, no. 6: 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060389

APA StyleAchouche, N., Endeweld, M., & Bental, B. (2025). Paths to Self-Employment: The Role of Childbirth Timing in Shaping Entrepreneurial Outcomes. Social Sciences, 14(6), 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060389