Empowerment of Rural Women Through Autonomy and Decision-Making

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Methodology

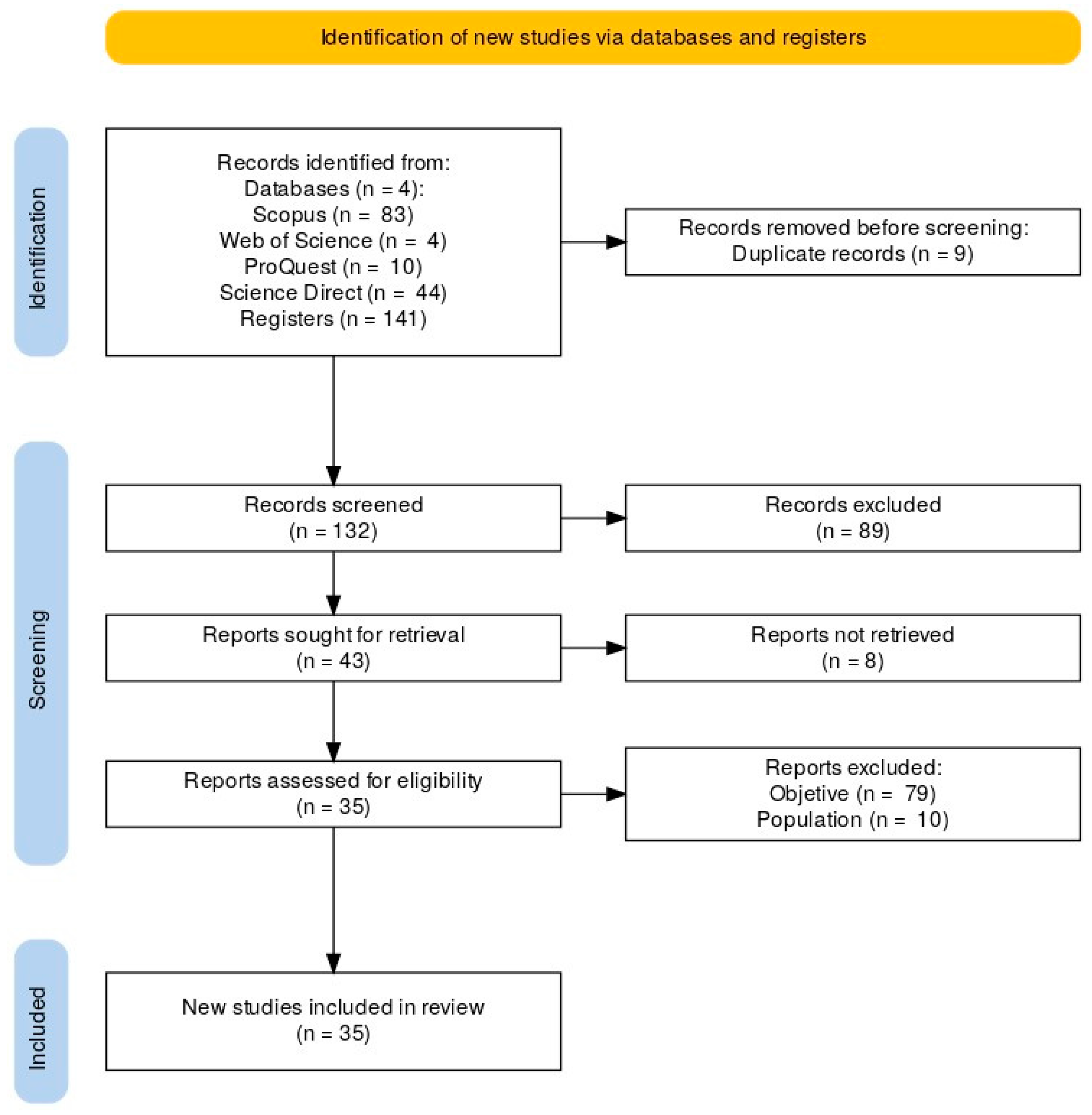

2.2. Using PRISMA to Select Materials

2.3. Results of the Adoption of PRISMA

3. Analysis of Selected Materials and Discussion

3.1. Women’s Empowerment

3.2. Focus on Women’s Autonomy

3.3. Decision-Making

3.4. Sustainable Development

3.5. Limitations of the Study

- -

- Language restriction. The review was limited to the literature published in English and Spanish. This decision facilitated the rigorous analysis of the texts; however, it may have excluded relevant research published in other languages such as French, Portuguese, Chinese, Hindi, Arabic or other languages in other latitudes such as West Africa, Southeast Asia or the Middle East. This exclusion of languages may reduce the overall representativeness of the findings.

- -

- Reliance on secondary sources. The study relied on secondary information extracted from scientific articles. Although these studies were carefully selected using PRISMA criteria, the quality and consistency of the data vary across research, as indicators of empowerment, autonomy and decision-making are not always homogeneous or comparable across contexts, which may affect the generalisability of the conclusions.

- -

- Possible publication bias and open access. The search prioritised indexed and open access journals. These articles facilitate dissemination but do not necessarily represent the totality of knowledge produced.

- -

- Predominant quantitative approach. Most of the included studies employed quantitative methodologies and the use of empowerment indices (such as the WEAI). This implies a possible underrepresentation of qualitative or participatory approaches to understanding the symbolic, subjective and contextual dimensions of rural women’s power.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdu, Aishat, Esi K. Colecraft, Grace S. Marquis, Naa D. Dodoo, and Franque Grimard. 2022. The association of women’s participation in farmer-based organizations with female and male empowerment and its implication for nutrition-sensitive agriculture interventions in rural Ghana. Current Developments in Nutrition 6: nzac121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, Bina. 1997. “Bargaining” and gender relations: Within and beyond the household. Feminist Economics 3: 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, Sonia. 2021. Do catastrophic floods change the gender division of labor? Panel data evidence from Pakistan. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 60: 102296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkire, Sabina, Ruth Meinzen-Dick, Amber Peterman, Agnes Quisumbing, Greg Seymour, and Ana Vaz. 2013. The Women’s empowerment in agriculture index. World Development 52: 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, Chiew Way, and Siow Li Lai. 2023. Women’s Empowerment in Malaysia and Indonesia: The Autonomy of Women in Household Decision-Making. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities 31: 155–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyidoho, Nana Akua. 2020. Women, Gender, and Development in Africa. In The Palgrave Handbook of African Women’s Studies. Edited by Olajumoke Yacob-Haliso and Toyin Falola. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 155–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batliwala, Srilatha. 2007. Taking the power out of empowerment—An experiential account. Development in Practice 17: 557–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutia, Kesand Wangmo. 2021. Labour Force Participation Rate in Agricultural and Non-Agricultural Activities in Sikkim with Special Emphasis on Women’s Work Participation: Variation Across Districts. Indian Journalds 9: 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonis-Profumo, Gianna, Stacey Natasha, and Julie Brimblecombe. 2021. Measuring women’s empowerment in agriculture, food production, and child and maternal dietary diversity in Timor-Leste. Food Policy 102: 102102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordo, Susan. 2003. Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body. Los Ángeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Judith. 2004. Lenguaje, Poder e Identidad. [Language, Power and Identity]. Madrid: Editorial Síntesis. Available online: https://studylib.es/doc/9428491/butler--judith---lenguaje--poder-e-identidad--2004-?p=15 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Chant, Sylvia. 2016. Women, girls and world poverty: Empowerment, equality or essentialism? International Development Planning Review 38: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwall, Andrea, and Jenny Edwards. 2010. Introduction: Negotiating empowerment. Ids Bulletin 41: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1991. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review 43: 1241–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Kathy. 2007. The Making of our Bodies, Ourselves: How Feminism Travels Across Borders. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deere, Carmen Diana, and Magdalena León. 2001. Empowering Women: Land and Property Rights in Latin America. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. Available online: https://books.google.cl/books?hl=es&lr=&id=UpAREQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&dq=Empowering+women:+Land+and+property+rights+in+Latin+America&ots=G2WIN5ikAy&sig=m-LKvT4LkPBB5UGpNL39I4yTv1g#v=onepage&q=Empowering%20women%3A%20Land%20and%20property%20rights%20in%20Latin%20America&f=false (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Denyer, David, and David Tranfield. 2009. Producing a Systematic Review. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods. Los Angeles: Sage Publications Ltd., pp. 671–89. Available online: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/the-sage-handbook-of-organizational-research-methods/book230566#contents (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Duflo, Esther. 2012. Women empowerment and economic development. Journal of Economic Literature 50: 1051–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essilfie, Gloria, Joshua Sebu, Samuel Kobina Annim, and Emmanuel Ekow Asmah. 2021. Women’s empowerment and household food security in Ghana. International Journal of Social Economics 48: 279–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2011. The State of Food and Agriculture 2010–2011: Women in agriculture—Closing the Gender Gap for Development. Rome: FAO. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/i2050e/i2050e00.htm (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Foucault, Michel. 1983. Vigilar y Castigar. Nacimiento de la Prisión. [Surveillance and Punishment. Birth of the Prison]. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI. Available online: https://sigloxxieditores.com.mx/libro/vigilar-y-castigar-2/ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- García-Reyes, Paola, and Henrik Wiig. 2020. Reasons of gender. Gender, household composition and land restitution process in Colombia. Journal of Rural Studies 75: 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, Mehdi, Mohammad Badsar, Leila Falahati, and Email Karamidehkordi. 2021. The mediation effect of rural women empowerment between social factors and environment conservation (combination of empowerment and ecofeminist theories). Environment, Development and Sustainability 23: 13755–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzaga, Gretchen L., Wolfreda T. Alesna, and Editha G. Cagasan. 2022. Women’s experiences of a livelihood project after Haiyan: A phenomenological study. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 83: 103402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grown, Caren, Geeta Rao Gupta, and Aslihan Kes. 2005. Taking Action: Achieving Gender Equality and Empowering Women. London: Earthscan. Available online: https://books.google.com.co/books/about/Taking_Action.html?id=dP-SRE4WCJEC&redir_esc=y (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Haddaway, Neal R., Matthew J. Page, Chris C. Pritchard, and Luke A. McGuinness. 2022. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Systematic Reviews 18: e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haley, Chelsea, and Robin Marsh. 2021. Income generation and empowerment pathways for rural women of Jagusi Parish, Uganda: A double-sided sword. Social Sciences & Humanities Open 4: 100225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). 2009. Gender and Rural Microfinance: Reaching and Empowering Women. Rome: International Fund for Agricultural Development. Available online: https://www.findevgateway.org/sites/default/files/publications/files/mfg-en-paper-gender-and-rural-microfinance-reaching-and-empowering-women-aug-2009_0.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Ishfaq, Sidra, Abedullah, and Shahzad Kouser. 2023. Measurement and Determinants of Rural Women’s Empowerment in Pakistan. Global Social Welfare 10: 139–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Faisal Bin, and Madhuri Sharma. 2021. Gendered dimensions of unpaid activities: An empirical insight into rural Bangladesh households. Sustainability 13: 6670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Faisal Bin, and Madhuri Sharma. 2022. Socio-economic determinants of women’s livelihood time use in rural Bangladesh. GeoJournal 87: 439–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, Charu, Disha Saxena, Somnath Sen, and Deepak Sanan. 2023. Women’s land ownership in India: Evidence from digital land records. Land Use Policy 133: 106835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, Naila. 1999. Resource, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Development and Change 30: 435–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimli, Leyla, Els Lecoutere, Christine R. Wells, and Leyla Ismayilova. 2021. More assets, more decision-making power? Mediation model in a cluster-randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of the graduation program on women’s empowerment in Burkina Faso. World Development 137: 105159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagarde y De los Ríos, Marcela. 2005. Los Cautiverios de las Mujeres Madresposas, Monjas, Putas, Presas y Locas. [The Captivities of Women Motherswives, Nuns, Whores, Prisoners and Madwomen]. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/es/book/1867767/los-cautiverios-de-las-mujeres-madresposas-monjas-putas-presas-y-locas-pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Malhotra, Anju, and Sidney Ruth Schuler. 2005. Women’s empowerment as a variable in international development. In Measuring Empowerment: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives. Washington, DC: The World Bank, pp. 71–88. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/960161468175149824/pdf/344100PAPER0Me101Official0use0only1.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Mazhazha-Nyandoro, Zivanayi, and Verna Sambureni. 2022. Cotton farming and the socio-economic status of women in Zimbabwe. Gender & Behaviour 20: 19508-17. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-genbeh_v20_n2_a25 (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Mechlowitz, Karah, Nytia Singh, Xiaolong Li, Dehao Chen, Yang Yang, Anna Rabil, Adriana Joy Cheraso, Ibsa Abdusemed Ahmed, Jafer Kedir Amin, Wondwossen A. Gebreyes, and et al. 2023. Women’s empowerment and child nutrition in a context of shifting livelihoods in Eastern Oromia, Ethiopia. Frontiers in Nutrition 10: 1048532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihelich, John, and Debbie Storrs. 2003. Higher education and the negotiated process of hegemony: Embedded resistance among Mormon women. Gender & Society 17: 404–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, Toma Deb, and Dusit Athinuwat. 2021. Key factors of women empowerment in organic farming. GeoJournal 86: 2501–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, Lucie. 2021. Disrupted gender roles in Australian agriculture: First generation female farmers’ construction of farming identity. Agriculture and Human Values 38: 803–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhung, Pham Thi, Martin Kappas, and Daniel Wyss. 2020. Benefits and Constraints of the Agricultural Land Acquisition for Urbanization for Household Gender Equality in Affected Rural Communes: A Case Study in Huong Thuy Town, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam. Land 9: 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, Martha. 2012. Las mujeres y el desarrollo humano. [Women and Human Development]. Barcelona: Herder Editorial. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, Martha, and Amartya Sen. 1998. La calidad de vida. [Quality of life]. Ciudad de México: México, Fondo Cultura Económica. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/polis/8073 (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Okonya, Joshua S., Netsayi N. Mudege, John N. Nyaga, and Wellington Jogo. 2021. Determinants of Women’s Decision-Making Power in Pest and Disease Management: Evidence From Uganda. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 5: 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Rodríguez, Jeyle, and Esteban Picazzo-Palencia. 2022. Differences in Decision-Making Capacity Among Mexican Women of Different Ages. Population Research and Policy Review 41: 1525–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372: n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, Itishree, and Kuntala Lahiri-Dutt. 2020. What determines women’s agricultural participation? A comparative study of landholding households in rural India. Journal of Rural Studies 76: 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan Shrestha, Rosy, Sopin Jirakiattikul, and Mandip Shrestha. 2023. “Electricity is result of my good deeds”: An analysis of the benefit of rural electrification from the women’s perspective in rural Nepal. Energy Research & Social Science 105: 103268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quisumbing, Agnes R., Ruth Meinzen-Dick, Terri L. Raney, André Croppenstedt, Julia A. Behrman, and Amber Peterman. 2014. Gender in Agriculture. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, vol. 102072, p. 444. [Google Scholar]

- Raynolds, Laura T. 2021. Gender equity, labor rights, and women’s empowerment: Lessons from Fairtrade certification in Ecuador flower plantations. Agriculture and Human Values 38: 657–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, Jo. 1997. Questioning Empowerment: Working with Women in Honduras. London: Oxfam. Available online: https://policy-practice.oxfam.org/resources/questioning-empowerment-working-with-women-in-honduras-121185/ (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Sarma, Nayantara. 2022. Domestic violence and workfare: An evaluation of India’s MGNREGS. World Development 149: 105688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, Amartya. 1985. Commodities and Capabilities. Ámsterdam: North-Holland. Available online: https://archive.org/details/commoditiescapab0000sena (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Sen, Amartya. 2000. Desarrollo y Libertad. [Development and Freedom]. Barcelona: Ediciones Planeta. Available online: https://archive.org/details/desarrollo_y_libertad_-_amartya_sen (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Shahwar, Durr E., Ishti Khan, Naveed Farah, and Babar Shahbaz. 2021. Obstacles and challanges for women empowerment in agriculture: The case of Rural Punjab, Pakistan. Journal of Agricultural Sciences 58: 1075–1080. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351451136_OBSTACLES_AND_CHALLANGES_FOR_WOMEN_EMPOWERMENT_IN_AGRICULTURE_THE_CASE_OF_RURAL_PUNJAB_PAKISTAN (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Sharma, Eliza, and Subhankar Das. 2021. Integrated model for women empowerment in rural India. Journal of International Development 33: 594–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, Hannah, and Allison Shwachman Kaminaga. 2023. What’s in a name? Property titling and women’s empowerment in Benin. Land Use Policy 129: 106608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, Gitta, Emily L. Pakhtigian, and Marc Jeuland. 2023. Women who do not migrate: Intersectionality, social relations, and participation in Western Nepal. World Development 161: 106–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, Hannah. 2019. Literature Review as a Research Methodology: An Overview and Guidelines. Journal of Business Research 104: 333–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagat, Anirudh. 2020. Female matters: Impact of a workfare program on intra-household female decision-making in rural India. World Development Perspectives 20: 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timsina, Pragya, Anjana Chaudhary, Akriti Sharma, Emma Karki, Bhavya Suri, and Brendan Brown. 2023. Necessity as a driver in bending agricultural gender norms in the Eastern Gangetic Plains of South Asia. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 21: 2247766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, David, David Denyer, and Palminder Smart. 2003. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. British Journal of Management 14: 207–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2022. Gender Equality Strategy 2022–2025. New York: UNDP. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Library. 2024. Tesauro UNBIS. Available online: https://metadata.un.org/thesaurus/categories?lang=es (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Weber, Max. 1978. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. Los Ángeles: University of California Press. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000033128 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Wei, Wei, Tanwne Sarker, Rana Roy, Apurbo Sarkar, and Md Ghulam Rabbany. 2021. Women’s empowerment and their experience to food security in rural Bangladesh. Sociology of Health and Illness 43: 971–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Development Report. 2012. Gender Equality and Development: Main Report (English). Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/492221468136792185/Main-report (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Zheng, Hongyun, Yuwen Zhou, and Dil Bahadur Rahut. 2023. Smartphone use, off-farm employment, and women’s decision-making power: Evidence from rural China. Review of Development Economics 27: 1327–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumbyte, Ieva. 2021. The gender system and class mobility: How wealth and community veiling shape women’s autonomy in India. Sociology of Development 7: 469–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Descriptors |

|---|---|

| Women empowerment |

|

| |

| |

| Women’s autonomy |

|

| |

| Women’s decision-making |

|

| In Spanish | In English |

|---|---|

| (“empoderamiento femenino” OR “promoción de la mujer” OR “mujeres rurales” OR “Mujer y medio ambiente”) AND (“autonomía femenina” OR “trabajo no remunerado” OR “igualdad de remuneración”) AND (“toma de decisiones de la mujer” OR “mujeres en la agricultura”) | (“Women empowerment” OR “Promotion of women” OR “Rural women” OR “Women and the environment”) AND (“Women’s autonomy” OR “Unpaid work” OR “ Equal pay”) AND (“Women’s decision-making” OR “Women in agriculture”) |

| Database | English | Spanish | Total * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Web of Science | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Scopus | 82 | 1 | 83 |

| ProQuest | 9 | 1 | 10 |

| Science Direct | 44 | 0 | 44 |

| Total | 139 | 2 | 141 |

| Source | Items Included |

|---|---|

| World Development | 16 |

| Social Science & Medicine | 5 |

| Food Policy | 4 |

| GeoJournal | 3 |

| Population Research and Policy Review | 3 |

| Global Food Security | 3 |

| Energy Research & Social Science | 3 |

| World Development Perspectives | 2 |

| Journal of Biosocial Science | 2 |

| Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Sciences | 2 |

| Environment, Development and Sustainability | 2 |

| Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems | 2 |

| Midwifery | 2 |

| Land Use Policy | 2 |

| International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction | 2 |

| Agriculture and Human Values | 2 |

| Feminist Economics | 2 |

| Journal of Rural Studies | 2 |

| Journal of International Development | 2 |

| Others | 71 |

| Total | 132 |

| N° | Author | Title | Year of Publication | Journal | Categories Addressed | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural Women | Women’s Empowerment | Autonomy Approach | Decision-Making (Choice Theory) | Sustainable Development | |||||

| 1 | Abdu, A.; Marquis, G.S.; Colecraft, E.K.; Dodoo, N.D.; Grimard, F. (Abdu et al. 2022) | The Association of Women’s Participation in Farmer-Based Organizations with Female and Male Empowerment and its Implication for Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture Interventions in Rural Ghana | 2022 | Current Developments in Nutrition | X | X | X | ||

| 2 | Akter, S. (Akter 2021) | Do catastrophic floods change the gender division of labor? Panel data evidence from Pakistan | 2021 | International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction | X | X | X | ||

| 3 | Ang, C.W.; Lai, S.L. (Ang and Lai 2023) | Women’s Empowerment in Malaysia and Indonesia: The Autonomy of Women in Household Decision-Making | 2023 | Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities | X | X | X | X | |

| 4 | Bhutia, K. W. (Bhutia 2021) | Labour Force Participation Rate in Agricultural and Non-Agricultural Activities in Sikkim with Special Emphasis on Women’s Work Participation: Variation Across Districts | 2021 | International Journal of Applied Science and Engineering | X | X | |||

| 5 | Bonis-Profumo, G.; Stacey, N.; Brimblecombe, J. (Bonis-Profumo et al. 2021) | Measuring women’s empowerment in agriculture, food production, and child and maternal dietary diversity in Timor-Leste | 2021 | Food Policy | X | X | X | X | |

| 6 | Essilfie, G.; Sebu, J.; Annim, S.K.; Asmah, E.E. (Essilfie et al. 2021) | Women’s empowerment and household food security in Ghana | 2021 | International Journal of Social Economics | X | X | X | ||

| 7 | García-Reyes, Paola; Wiig, Henrik (García-Reyes and Wiig 2020) | Reasons of gender. Gender, household composition and land restitution process in Colombia | 2020 | Journal of Rural Studies | X | X | |||

| 8 | Ghasemi, M.; Badsar, M.; Falahati, L.; Karamidehkordi, E. (Ghasemi et al. 2021) | The mediation effect of rural women empowerment between social factors and environment conservation (combination of empowerment and ecofeminist theories) | 2021 | Environment, Development and Sustainability | X | X | X | X | X |

| 9 | Gonzaga, Gretchen L.; Alesna, Wolfreda T.; Cagasan, Editha G. (Gonzaga et al. 2022) | Women’s experiences of a livelihood project after Haiyan: A phenomenological study | 2022 | International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction | X | X | X | ||

| 10 | Haley, Ch.; Marsh, R. (Haley and Marsh 2021) | Income generation and empowerment pathways for rural women of Jagusi Parish, Uganda: A double-sided sword | 2021 | Social Sciences & Humanities Open | X | X | X | X | |

| 11 | Ishfaq, S.; Kouser, S. (Ishfaq et al. 2023) | Measurement and Determinants of Rural Women’s Empowerment in Pakistan | 2023 | Global Social Welfare | X | X | X | X | X |

| 12 | Islam, F.B.; Sharma, M. (Islam and Sharma 2021) | Gendered dimensions of unpaid activities: An empirical insight into rural Bangladesh households | 2021 | Sustainability | X | X | X | X | X |

| 13 | Islam, F.B.; Sharma, M. (Islam and Sharma 2022) | Socio-economic determinants of women’s livelihood time use in rural Bangladesh | 2022 | GeoJournal | X | X | X | X | |

| 14 | Jain, C.; Saxena, D.; Sen, S.; Sanan, D. (Jain et al. 2023) | Women’s land ownership in India: Evidence from digital land records | 2023 | Land Use Policy | X | X | X | ||

| 15 | Karimli, L.; Lecoutere, E.; Wells, Ch. R.; Ismayilova, L. (Karimli et al. 2021) | More assets, more decision-making power? Mediation model in a cluster-randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of the graduation program on women’s empowerment in Burkina Faso | 2021 | World Development | X | X | X | X | |

| 16 | Mazhazha-Nyandoro, Z.; Sambureni, V. (Mazhazha-Nyandoro and Sambureni 2022) | Cotton farming and the socio-economic status of women in Zimbabwe | 2022 | Gender & Behaviour | X | X | X | X | X |

| 17 | Mechlowitz, K.; Singh, N.; Li, X.; Chen, D.; Yang, Y.; Rabil, A.; Cheraso, A.J.; Ahmed, I.A.; Amin, J.K.; Gebreyes, W.A.; Hassen, J.Y.; Ibrahim, A.M.; Manary, M.J.; Rajashekara, G.; Roba, K.T.; Usmane, I.A.; Havelaar, A.H.; McKune, S.L.; (Mechlowitz et al. 2023) | Women’s empowerment and child nutrition in a context of shifting livelihoods in Eastern Oromia, Ethiopia | 2023 | Frontiers in Nutrition | X | X | X | X | X |

| 18 | Nath, T.D.; Athinuwat, D. (Nath and Athinuwat 2021) | Key factors of women empowerment in organic farming | 2021 | GeoJournal | X | X | X | X | X |

| 19 | Newsome, L. (Newsome 2021) | Disrupted gender roles in Australian agriculture: first generation female farmers’ construction of farming identity | 2021 | Agriculture and Human Values | X | X | X | X | X |

| 20 | Nhung Pham T.; Kappas, M.; Wyss, D. (Nhung et al. 2020) | Benefits and Constraints of the Agricultural Land Acquisition for Urbanization for Household Gender Equality in Affected Rural Communes: A Case Study in Huong Thuy Town, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam | 2020 | Land | X | X | X | ||

| 21 | Okonya, J.S.; Mudege, N.N.; Nyaga, J.N.; Jogo, W. (Okonya et al. 2021) | Determinants of Women’s Decision-Making Power in Pest and Disease Management: Evidence From Uganda | 2021 | Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems | X | X | X | X | |

| 22 | Ortiz-Rodríguez, J.; Picazzo-Palencia, E. (Ortiz-Rodríguez and Picazzo-Palencia 2022) | Differences in Decision-Making Capacity Among Mexican Women of Different Ages | 2022 | Population Research and Policy Review | X | X | X | X | |

| 23 | Pattnaik, Itishree; Lahiri-Dutt, Kuntala (Pattnaik and Lahiri-Dutt 2020) | What determines women’s agricultural participation? A comparative study of landholding households in rural India | 2020 | Journal of Rural Studies | X | X | X | ||

| 24 | Pradhan Shrestha, Rosy; Jirakiattikul, Sopin; Shrestha, Mandip (Pradhan Shrestha et al. 2023) | “Electricity is result of my good deeds”: An analysis of the benefit of rural electrification from the women’s perspective in rural Nepal | 2023 | Energy Research & Social Science | X | X | X | X | X |

| 25 | Raynolds, Laura T. (Raynolds 2021) | Gender equity, labor rights, and women’s empowerment: lessons from Fairtrade certification in Ecuador flower plantations | 2021 | Agriculture and Human Values | X | X | X | X | |

| 26 | Sarma, N. (Sarma 2022) | Domestic violence and workfare: An evaluation of India’s MGNREGS | 2022 | World Development | X | X | X | ||

| 27 | Shahwar, D.; Khan, I.A.; Farah, N.; Shahbaz, B. (Shahwar et al. 2021) | Obstacles and challanges for women empowerment in agriculture: The case of Rural Punjab, Pakistan | 2021 | Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Sciences | X | X | X | X | |

| 28 | Sharma, E.; Das, S. (Sharma and Das 2021) | Integrated model for women empowerment in rural India | 2020 | Journal of International Development | X | X | X | X | X |

| 29 | Sheldon, Hannah; Kaminaga, Allison Shwachman (Sheldon and Kaminaga 2023) | What’s in a name? Property titling and women’s empowerment in Benin | 2023 | Land Use Policy | X | X | X | X | |

| 30 | Shrestha, Gitta; Pakhtigian, Emily L.; Jeuland, Marc (Shrestha et al. 2023) | Women who do not migrate: Intersectionality, social relations, and participation in Western Nepal | 2023 | World Development | X | X | X | ||

| 31 | Tagat, A. (Tagat 2020) | Female matters: Impact of a workfare program on intra-household female decision-making in rural India | 2020 | World Development Perspectives | X | X | X | ||

| 32 | Timsina, P.; Chaudhary, A.; Sharma, A.; Karki, E.; Suri, B.; Brown, B. (Timsina et al. 2023) | Necessity as a driver in bending agricultural gender norms in the Eastern Gangetic Plains of South Asia | 2023 | International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability | X | X | X | X | X |

| 33 | Wei, W.; Sarker, T.; Roy, R.; Sarkar, A.; Ghulam Rabbany, M. (Wei et al. 2021) | Women’s empowerment and their experience to food security in rural Bangladesh | 2021 | Sociology of Health and Illness | X | X | X | X | X |

| 34 | Zheng, H.; Zhou, Y.; Rahut, D.B. (Zheng et al. 2023) | Smartphone use, off-farm employment, and women’s decision-making power: Evidence from rural China | 2023 | Review of Development Economics | X | X | X | X | |

| 35 | Zumbyte, I. (Zumbyte 2021) | The gender system and class mobility: How wealth and community veiling shape women’s autonomy in India | 2021 | Sociology of Development | X | X | X | X | |

| Strategic Dimensions | Findings or Evidence | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Economic autonomy and access to resources | Evidence shows that ownership and control of assets (land, income, credit, technology) are directly related to greater decision-making capacity (Ishfaq et al. 2023; Karimli et al. 2021). |

|

| 2. Education and capacity building | Educational attainment and functional literacy impact decisional autonomy (Ang and Lai 2023). |

|

| 3. Participation in community spaces and collective decision-making | Active participation in organisations and committees strengthens collective agency (Abdu et al. 2022). |

|

| 4. Transformation of sociocultural norms | Entrenched gender norms restrict autonomy (Bonis-Profumo et al. 2021; Zumbyte 2021). |

|

| 5. Strengthening inner power (subjective agenda) | Empowerment is also underpinned by self-esteem, dignity and critical awareness (Rowlands 1997). |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Albornoz-Arias, N.; Rojas-Sanguino, C.; Santafe-Rojas, A.-K. Empowerment of Rural Women Through Autonomy and Decision-Making. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080469

Albornoz-Arias N, Rojas-Sanguino C, Santafe-Rojas A-K. Empowerment of Rural Women Through Autonomy and Decision-Making. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(8):469. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080469

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlbornoz-Arias, Neida, Camila Rojas-Sanguino, and Akever-Karina Santafe-Rojas. 2025. "Empowerment of Rural Women Through Autonomy and Decision-Making" Social Sciences 14, no. 8: 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080469

APA StyleAlbornoz-Arias, N., Rojas-Sanguino, C., & Santafe-Rojas, A.-K. (2025). Empowerment of Rural Women Through Autonomy and Decision-Making. Social Sciences, 14(8), 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080469