Adolescents’ Openness to Include Refugee Peers in Their Leisure Time Activities

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Adolescents’ Openness Regarding Refugee Peers

1.2. Theoretical Framework

1.3. Current Study

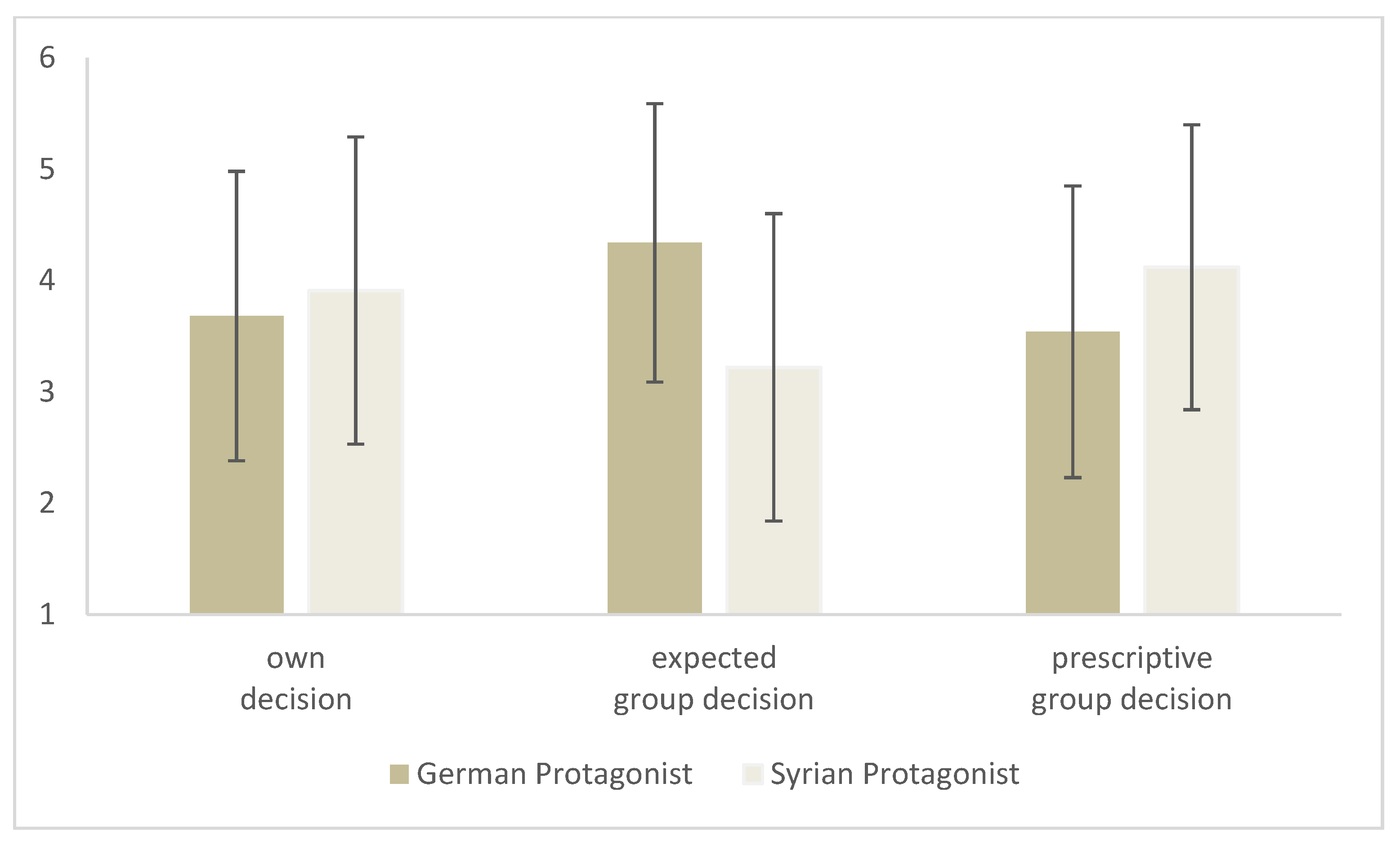

- Adolescents expect that their group would be less inclusive of the Syrian peer than they themselves would be and than they thought their group should be.

- Adolescents’ reasoning about the group decision will include more references to socialconventional aspects and group functioning (compared to the reasoning about their own decision and about what the group should do).

- Adolescents’ reasoning about their own decision and about what the group should do will include more moral reasoning (compared to the reasoning about what the group would carry out).

- A protagonist with high skills will be more likely included than one with low skills. This should be true for adolescents’ own decisions and their expected group decisions; skill should be less likely to be associated with expectations about what the group should do.

- If there were differences in the skill level of the German and the Syrian peer, there should be more reasoning about group functioning than in conditions in which the skills of the protagonists were the same.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Design and Procedures

2.3. Material and Measures

Imagine you have a group of friends at school. You usually spend recess and much of your free time together. The following situation refers to this group.Now, imagine you and your group are planning to play video games this afternoon. You can only invite one more person. But there are two boys/girls who would like to join your group: Lukas/Laura and Rami/Shata. Both are new at your school. Lukas/Laura moved here from Bremen, he/she is German. Rami/Shata came to Germany with his/her family as a refugee from Syria.

2.4. Coding of Open-Ended Answers

2.4.1. Knowledge About Refugees

2.4.2. Justifications for Inclusion Decisions

3. Results

3.1. Inclusion Decisions

3.2. Reasoning Analyses

3.3. Knowledge About Refugees

4. Discussion

4.1. Inclusion Decisions

4.2. Reasoning

4.3. Knowledge About Refugees

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

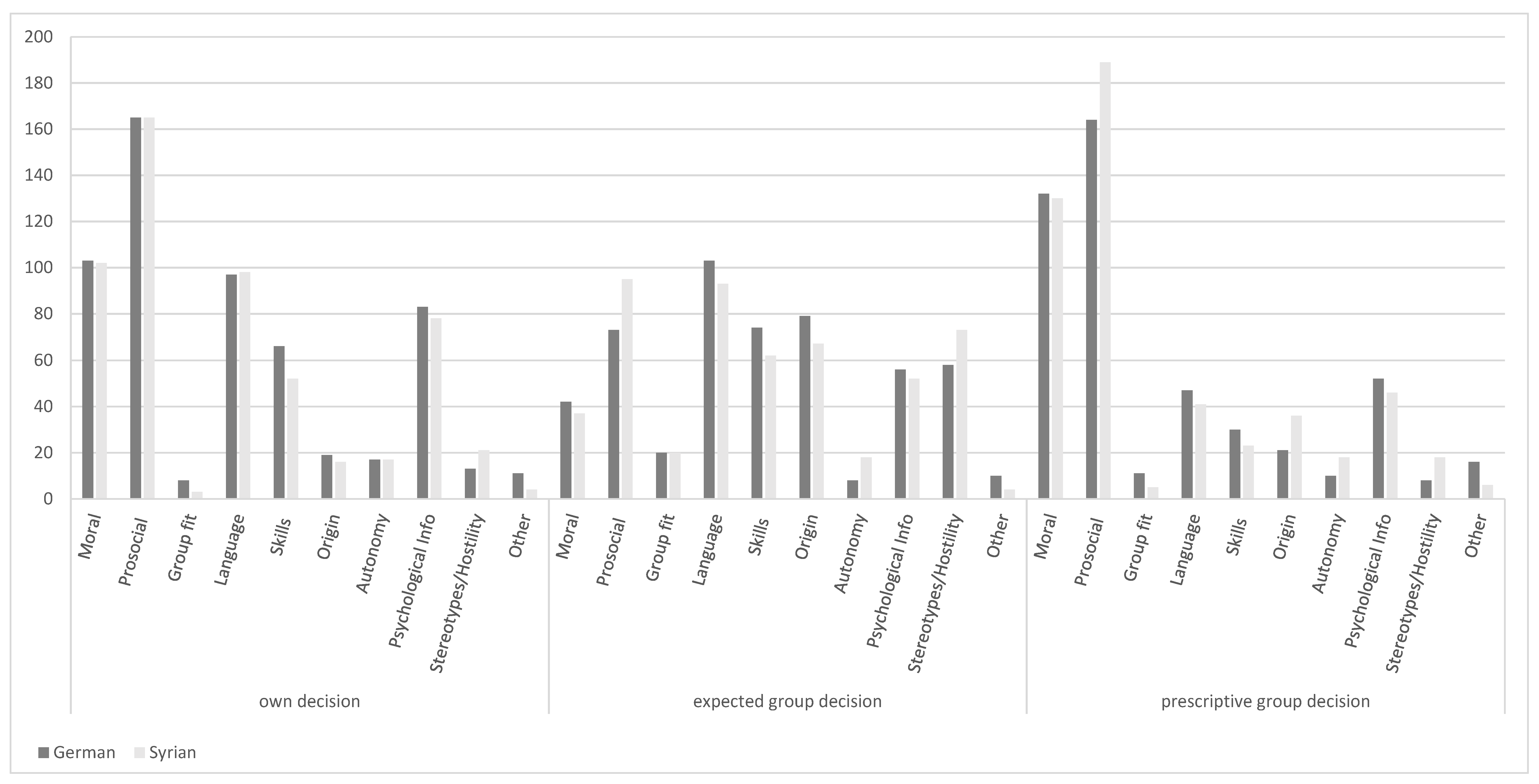

Appendix A. Frequencies of Code Use by Different Measures

References

- Albert, Mathias, Klaus Hurrelmann, and Gudrun Quenzel. 2019. Jugend 2019-18. Shell Jugendstudie: Eine Generation meldet sich zu Wort [Youth 2019-18. Shell Youth Study: A Generation Speaks Out]. Weinheim: Beltz. [Google Scholar]

- Andresen, Sabine, Sascha Neumann, and Ulrich Schneekloth. 2021. How children in Germany experience refugees: A contribution from childhood studies. Child Indicators Research 14: 2045–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beißert, Hanna, and Kelly Lynn Mulvey. 2022. Inclusion of refugee peers: Differences between own preferences and expectations of the peer group. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 855171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beißert, Hanna, Seçil Gönültaş, and Kelly Lynn Mulvey. 2020. Social inclusion of refugee and native peers among adolescents: It is the language that matters! Journal of Research on Adolescence 30: 219–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, John Widdup. 2011. Integration and Multiculturalism: Ways Towards Social Solidarity. Papers on Social Representations 20: 2.1–2.21. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, John Widdup, Jean S. Phinney, David Lackland Sam, and Paul Vedder. 2006. Immigrant Youth in Cultural Transition: Acculturation, Identity, and Adaptation Across National Contexts. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Bradford. 2013. Adolescents’ relationships with peers. In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. Edited by Richard M. Lerner and Laurence Steinberg. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 363–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, Claire V., Nataliya Kubishyn, Amira Noyes, and Gina Kayssi. 2022. Engaging peers to promote well-being and inclusion of newcomer students: A call for equity-informed peer interventions. Psychology in the Schools 59: 2422–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. 2021. First Instance Decisions on Applications by Citizenship, Age and Sex-Annual Aggregated Data (Rounded). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/MIGR_ASYDCFSTA__custom_1497203/bookmark/table?lang=en&bookmarkId=062d9510-98db-4fc8-9e30-e07b3d30ae79 (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Gambaro, Ludovica, Daniel Kemptner, Lisa Pagel, Laura Schmitz, and C. Katharina Spieß. 2020. Integration of refugee children and adolescents in and out of school: Evidence of success but still room for improvement. DIW Weekly Report 10: 345–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitti, Aline, and Melanie Killen. 2015. Expectations about ethnic peer group inclusivity: The role of shared interests, group norms, and stereotypes. Child Development 86: 1522–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitti, Aline, Kelly Lynn Mulvey, and Melanie Killen. 2011. Social exclusion and culture: The role of group norms, group identity and fairness. Anales de Psicología 27: 587–99. [Google Scholar]

- Killen, Melanie, and Adam Rutland. 2011. Children and Social Exclusion: Morality, Prejudice and Group Identity. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killen, Melanie, and Charles Stangor. 2001. Children’s social reasoning about inclusion and exclusion in gender and race peer group contexts. Child Development 72: 174–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killen, Melanie, and Judith G. Smetana. 2015. Origins and development of morality. In Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science. Edited by Michael E. Lamb. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, vol. 3, pp. 701–49. [Google Scholar]

- Killen, Melanie, Kerry Pisacane, Jennie Lee-Kim, and Alicia Ardila-Rey. 2001. Fairness or stereotypes? Young children’s priorities when evaluating group exclusion and inclusion. Developmental Psychology 37: 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killen, Melanie, Laura Elenbaas, Michael T. Rizzo, and Adam Rutland. 2017. The Role of Group Processes in Social Exclusion and Resource Allocation Decisions. In The Wiley Handbook of Group Processes in Children and Adolescents. Edited by Adam Rutland, Drew Nesdale and Christia Spears Brown. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kober, Ulrich, and Orkan Kösemen. 2019. Willkommenskultur zwischen Skepsis und Pragmatik: Deutschland nach der „Fluchtkrise“ [Welcome Culture Between Skepticism and Pragmatism: Germany After the Refugee Crisis]. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kösemen, Orkan, and Ulrike Wieland. 2022. Willkommenskultur zwischen Stabilität und Aufbruch: Aktuelle Perspektiven der Bevölkerung auf Migration und Integration in Deutschland [Welcome culture between stability and change: Current perspectives of the population on migration and integration in Germany]. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, Luke, Adam Rutland, and Drew Nesdale. 2015. Peer group norms and accountability moderate the effect of school norms on children’s intergroup attitudes. Child Development 86: 1290–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuire, Luke, Michael T. Rizzo, Melanie Killen, and Adam Rutland. 2018. The development of intergroup resource allocation: The role of cooperative and competitive in-group norms. Developmental Psychology 54: 1499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, Luke, Michael T. Rizzo, Melanie Killen, and Adam Rutland. 2019. The role of competitive and cooperative norms in the development of deviant evaluations. Child Development 90: e703–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mediendienst Integration. 2024. Flucht & Asyl: Syrische Flüchtlinge [Refuge & asylum: Syrian refugees]. Available online: https://mediendienst-integration.de/migration/flucht-asyl/syrische-fluechtlinge.html (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Mulvey, Kelly Lynn. 2016. Children’s reasoning about social exclusion: Balancing many factors. Child Development Perspectives 10: 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvey, Kelly Lynn, Aline Hitti, Adam Rutland, Dominic Abrams, and Melanie Killen. 2014. When do children dislike ingroup members? Resource allocation from individual and group perspectives. Journal of Social Issues 70: 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakeyar, Cisse, Victoria Esses, and Graham J. Reid. 2018. The psychosocial needs of refugee children and youth and best practices for filling these needs: A systematic review. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry 23: 186–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesdale, Drew, Michael J. Lawson, Kevin Durkin, and Amanda Duffy. 2010. Effects of information about group members on young children’s attitudes towards the in-group and out-group. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 28: 467–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oncu, Elif Celebi, and Dilara Yilmaz. 2022. Primary school pupils’ views on refugee peers: Are they accepted or not? Intercultural Education 33: 302–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapanta, Chrysi, and Susana Trovão. 2020. Shall we receive more refugees or not? A comparative analysis and assessment of Portuguese adolescents’ arguments, views, and concerns. Pedagogy, Culture & Society 28: 581–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, Michael T., Shelby Cooley, Laura Elenbaas, and Melanie Killen. 2018. Young children’s inclusion decisions in moral and social–conventional group norm contexts. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 165: 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutland, Adam, and Melanie Killen. 2015. A developmental science approach to reducing prejudice and social exclusion: Intergroup processes, social-cognitive development, and moral reasoning. Social Issues and Policy Review 9: 121–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutland, Adam, Melanie Killen, and Dominic Abrams. 2010. A new social-cognitive developmental perspective on prejudice: The interplay between morality and group identity. Perspectives on Psychological Science 5: 279–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smetana, Judith G., Marc Jambon, and Courtney Ball. 2014. The social domain approach to children’s moral and social judgments. In Handbook of Moral Development, 2nd ed. Edited by Melanie Killen and Judith G. Smetana. New York and London: Psychology Press, pp. 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, Henri, and John Charles Turner. 1976. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Edited by William G. Austin and Stephen Worchel. Belmont: Brooks-Cole, pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, Henri, and John Charles Turner. 1986. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In The Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Edited by Stephen Worchel and William G. Austin. Binfield: Nelson Hall, pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Toppe, Theo, Susanne Hardecker, and Daniel Benjamin Moritz Haun. 2020. Social inclusion increases over early childhood and is influenced by others’ group membership. Developmental Psychology 56: 324–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turiel, Elliot. 1983. The Development of Social Knowledge: Morality and Convention. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. 2024. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2023. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/global-trends-report-2023 (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- van Bommel, Ghislaine, Jochem Thijs, and Marta Miklikowska. 2021. Parallel empathy and group attitudes in late childhood: The role of perceived peer group attitudes. The Journal of Social Psychology 161: 337–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Würbel, Iris, and Patricia Kanngiesser. 2023. Pre-schoolers’ images, intergroup attitudes, and liking of refugee peers in Germany. PLoS ONE 18: e0280759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Condition | Wording | |

|---|---|---|

| A | Syrian peer skilled, German peer skilled | Both are very good in playing Wii. |

| B | Syrian peer not skilled, German peer not skilled | Both have never played Wii before. |

| C | Syrian peer skilled, German peer not skilled | Rami/Shata is very good in playing Wii. Lukas/Laura has never played Wii before. |

| D | Syrian peer not skilled, German peer skilled | Lukas/Laura is very good in playing Wii. Rami/Shata has never played Wii before. |

| Own Decision | Expected Group Decision | Prescriptive Group Decision | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| German | Syrian | German | Syrian | German | Syrian | |

| MORAL DOMAIN | ||||||

| Moral “because there should be fairness” | 103 | 102 | 42 | 37 | 132 | 130 |

| Prosocial “because I want to help her find friends” | 165 | 165 | 73 | 95 | 164 | 189 |

| SOCIETAL DOMAIN | ||||||

| Group fit “it’s easier to play with someone who knows our culture” | 8 | 3 | 20 | 20 | 11 | 5 |

| Language “if she doesn’t know German, we can’t explain her the game.” | 97 | 98 | 103 | 93 | 47 | 41 |

| Skills “I’d choose her because she is better in playing Wii.” | 66 | 52 | 74 | 62 | 30 | 23 |

| Origin “I’d choose her because she is from Germany.” | 19 | 16 | 79 | 67 | 21 | 36 |

| Hostility and stereotypes “refugees don’t belong here”, “refugees will steal our stuff” | 13 | 21 | 58 | 73 | 8 | 18 |

| PSYCHOLOGICAL DOMAIN | ||||||

| Autonomy “because I want to get to know her” | 17 | 17 | 8 | 18 | 10 | 18 |

| Psychological information “if she is nice and friendly why should I not choose her” | 83 | 78 | 56 | 52 | 52 | 46 |

| Other | 11 | 4 | 10 | 4 | 16 | 6 |

| Own Decision M (SE) | Expected Group Decision M (SE) | Prescriptive Group Decision M (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moral | 0.22 (0.02) a,c | 0.09 (0.01) a | 0.30 (0.02) c |

| Prosocial | 0.35 (0.02) b | 0.18 (0.02) b | 0.39 (0.02) |

| Group fit | 0.04 (0.01) e | 0.15 (0.02) d,e | 0.03 (0.01) d |

| Language | 0.01 (0.01) j | 0.04 (0.01) f | 0.02 (0.01) f,j |

| Skills | 0.04 (0.01) k | 0.17 (0.02) h | 0.07 (0.01) h,k |

| Origin | 0.21 (0.02) i | 0.23 (0.02) g | 0.11 (0.01) g,i |

| Autonomy | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.01) |

| Psychological information | 0.19 (0.02) n | 0.12 (0.01) n,o | 0.12 (0.01) o |

| Hostility/stereotypes | 0.13 (0.01) l | 0.15 (0.02) l,m | 0.06 (0.01) m |

| Syrian Peer Skilled, German Peer Skilled (Condition A) M (SE) | Syrian Peer Not Skilled, German Peer Not Skilled (Condition B) M (SE) | Syrian Peer Skilled, German Peer Not Skilled (Condition C) M (SE) | Syrian Peer Not Skilled, German Peer Skilled (Condition D) M (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moral | 0.25 (0.03) i | 0.22 (0.03) k | 0.20 (0.02) | 0.14 (0.03) i,k |

| Prosocial | 0.19 (0.03) a,c | 0.24 (0.03) b,d | 0.35 (0.03) a,b | 0.44 (0.03) c,d |

| Group fit | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) |

| Language | 0.20 (0.03) q | 0.25 (0.03) r,s | 0.11 (0.03) q,r | 0.15 (0.03) s |

| Skills | 0.01 (0.02) e,f | 0.02 (0.02) g,h | 0.20 (0.02) e,g | 0.23 (0.02) f,h |

| Origin | 0.13 (0.02) m,n | 0.10 (0.02) | 0.07 (0.01) m | 0.07 (0.01) n |

| Autonomy | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) |

| Psychological information | 0.21 (0.03) o,p | 0.14 (0.02) | 0.08 (0.02) o | 0.13 (0.02) p |

| Hostility/stereotypes | 0.09 (0.02) a,b,j | 0.10 (0.01) l | 0.06 (0.01) a | 0.05 (0.01) b,j,l |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beißert, H.; Mulvey, K.L.; Bonefeld, M. Adolescents’ Openness to Include Refugee Peers in Their Leisure Time Activities. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050309

Beißert H, Mulvey KL, Bonefeld M. Adolescents’ Openness to Include Refugee Peers in Their Leisure Time Activities. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(5):309. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050309

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeißert, Hanna, Kelly Lynn Mulvey, and Meike Bonefeld. 2025. "Adolescents’ Openness to Include Refugee Peers in Their Leisure Time Activities" Social Sciences 14, no. 5: 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050309

APA StyleBeißert, H., Mulvey, K. L., & Bonefeld, M. (2025). Adolescents’ Openness to Include Refugee Peers in Their Leisure Time Activities. Social Sciences, 14(5), 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050309