Abstract

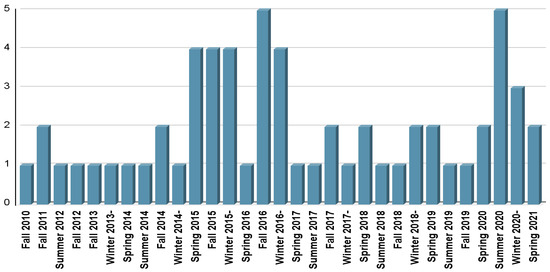

One in four students in the United States is part of an immigrant family. The purpose of this study is to enhance our understanding of the barriers that immigrant students experience in US public schools by critically analyzing how newspapers portray barriers to success, as the goals and processes used in media differ from those of peer-reviewed research. The authors used a document analysis, a qualitative research methodology, and reviewed 67 newspaper articles on immigrant children struggling in US schools. The results show that immigrant students struggle with language barriers, discrimination, mental health, financial stress associated with higher education in the US, lack of preparedness and resources to provide education, lack of familiarity with policy, lack of cultural knowledge about the US, lack of parent involvement, and work and familial obligations. Results also indicate that newspapers published more articles about immigrant struggles during certain time periods, such as Spring 2015 through Winter 2016 and again Summer 2020 through Spring 2021. The paper provides implications for (1) research, suggesting a need for more qualitative primary data collection, (2) practice, including enhanced training, improved mental health referrals and collaborations, and (3) policy, which could include welcoming policies at the school level and advocacy efforts for immigrant student rights under the incoming presidential administration.

Keywords:

education; immigrant; United States; struggles; inclusion; social and emotional well-being 1. Introduction

There are more than 40 million immigrants in the US (Budiman 2020), which is about one in every seven people (American Immigration Council 2021a). However, in US public schools, we saw 649,000 recent arrivals (i.e., children who had been in the US for three years or less) in 2021, in addition to 1.5 million immigrant children who have been in the US longer (Sugarman 2023). When we include children who are US citizens born to immigrant parents, we see about one in four students who are part of an immigrant family (Figlio et al. 2021). As of 2022, 89% of children living in immigrant families are US citizens (Annie E. Casey Foundation 2021), but there are 4.4 million US citizen children who have at least one undocumented parent (American Immigration Council 2021b).

School is often the first place where immigrant students can connect to people outside of their families, and it is often seen as a safe space for a return to normalcy (Birman et al. 2007; Correa-Velez et al. 2010; Kim and Suárez-Orozco 2014). For many immigrant families, school is necessary to advance in their careers, and many immigrant families highly value education (Zarate et al. 2016).

Immigration is a highly contested subject in the US (Bolter 2022; Jones-Correa 2012; Jones 2024), and, therefore, the purpose of this study is to understand the ways that newspapers portray the barriers that immigrant students experience in US public schools. The authors were curious to see if there were nuances found in the stories of the newspapers that are not otherwise captured in the peer-reviewed literature in order to amplify the knowledge that can be shared in academic spaces. The analysis was performed to assist in creating a full and accurate picture of how various struggles affect education for immigrant students in the US, and how these challenges have created a barrier to academic success. The research questions for this paper are as follows: (1) What are the barriers to immigrant student success in US schools discussed in the National Newspapers Proquest? (2) Which newspapers discuss immigrant student struggles most? and (3) Are there trends in when (month/year) articles on immigrant students have been published recently? To do this, we provide a literature review that summarizes some main themes discussed as barriers in the peer-reviewed literature, followed by the findings of our study, and a discussion of the findings. We end with implications for future research, practice (including mental health professionals and teachers), and policy.

2. Literature Review: Challenges Immigrant Students Experience

In this section, we aim to provide a brief overview and literature review regarding the challenges immigrant students (across many nationalities and immigration statuses) face in US public schools to provide background context for our study and the analysis below. The peer-reviewed research shows that immigrant students face a multitude of challenges to fully engaging in the classroom. As will be discussed, some of these challenges include language barriers (Umansky et al. 2022), financial difficulties (Batalova and Fix 2023), racism and discrimination (Kumi-Yeboah et al. 2020), mental health challenges and past traumatic experiences (Hasson III et al. 2020), and a host of challenges around the school systems, funding streams, policy, etc., at the macro level (DeMatthews and Izquierdo 2020; Evans et al. 2022b). We acknowledge that each of these topics could alone contain a full literature review, but here we aim to highlight the overarching themes as an introduction to the current study.

2.1. Discrimination

Discrimination, and specifically systemic racism based on race and ethnicity, is widespread in the US, and this is true for immigrants as well (Bu 2020; Esses 2021). Research indicates that institutional racism has led to social and structural inequities and health disparities (Hearst et al. 2021; Misra et al. 2021), greater psychological symptoms (Assari et al. 2018), lessened well-being, and increased stress (Torres et al. 2022) for immigrants living in the US. Before even entering the school building, immigrant students face discrimination in the enrollment process (Evans et al. 2020). This includes discrimination from the school administration in terms of required enrollment paperwork, as well as intentional and unconscious bias among schools, such as delays in academic testing and grade placement, and even teacher expectations (Booi et al. 2016; Evans et al. 2020). Once in school, many immigrant students experience bullying and teasing from classmates that stems from racism (Thakore-Dunlap and Van Velsor 2014).

Negative stereotypes of Latinx students and structural racism run deep in school systems (Rosenbloom and Way 2004; Carey 2019). This can lead to lower academic outcomes, behavioral acting out, and poor emotional well-being (Delgado et al. 2019). Other studies showed discrimination by teachers toward English Language Learning (ELL) students. For instance, teachers had views of immigration that were not true, such as the supposed “ease” with which an immigrant can be granted citizenship in the US (Monreal and McCorkle 2021). One study found that discrimination from teachers led to lower academic performance and a lack of motivation, which often led to dropping out (Brown 2015). Some textbooks used in classes reflected disinformation, either by omitting information, portraying immigration as fair and simple for all, or associating immigration with criminal activity (Monreal and McCorkle 2021). Misinformation and unconscious biases can be detrimental. For example, Kantamneni et al. (2016) discuss how, through inaction, educators, community members, and other well-intentioned individuals let undocumented students suffer through benign neglect.

2.2. Mental Health and Trauma

Another difficulty many immigrant students face is the trauma they have endured prior to entering US schools. Hasson III et al. (2020) found that PTSD was common in about eight percent of unaccompanied children in the US, which is higher than for the US-born population. Hos (2020) studied immigrant students’ need for social-emotional support due to past trauma and acculturative stress and found that not much effort was made by some schools to provide psychological support for students, which further marginalizes immigrant students. Overlooking psychological needs (Hos 2020) and social isolation (Lilly 2022) can deter immigrant students’ ability to fully participate in the US school system. Fuentes et al. (2024) found that some of the disparity was in immigrant students’ knowledge and logistical barriers to accessing services. At the same time, the sample of youth had positive attitudes towards mental health care, which is promising for increasing utilization rates moving forward.

2.3. Language

Many immigrant students struggle with language barriers in both classroom learning and interactions with peers and staff (Andrés Bolado 2023). While research suggests that, in general terms, many immigrant students enter school in the US academically behind their US-born peers, it also demonstrates that they grow their academic and language skills immensely in the first two years in the US (Umansky et al. 2022). Lee and Sauro (2021) suggest that language assessment should be performed over time to address learning changes and include student self-reports or other student-centered metrics. Barrett et al. (2012) found that immigrants’ English proficiency in sophomore year and math achievement in senior year were mediated by academic motivation. Immigrant students tend to rely on and be more comfortable with ELL teachers, and the lack of communication between students and their other teachers can negatively affect their learning experience (Somé-Guiébré 2016).

Beyond the challenges that the individual student faces due to language, it can be hard for immigrant families to access specific information and guide their children through US schools when information is unavailable in multiple languages (Norheim and Moser 2020; Sattin-Bajaj 2015). Also, many parents feel frustrated and discouraged by their inability to translate documents and material from English to their native language, or because of the absence of staff who can do it, relying on their children to translate for them (Norheim and Moser 2020). Similarly, Hong et al. (2021) found that during the COVID-19 pandemic, Korean parents experienced increased stress because of challenges in both meeting the educational needs of their children and their own language barriers.

2.4. Financial Struggles

US immigrant students and their families often face financial struggles and/or have limited financial resources (Batalova and Fix 2023; Thiede et al. 2021) as many live in low-income neighborhoods (DeMatthews and Izquierdo 2020). Haro-Ramos and Bacong (2022) found that Asian and Latinx immigrant households experienced greater food insecurity than their respective Asian and Latinx US-born peers. Food insecurity and hunger can make it hard for students to pay attention in class and learn (Rubio et al. 2019). This is complicated by the fact that undocumented families and those who have received citizenship in the last five years are generally unable to access social welfare assistance such as SNAP and TANF (Broder and Lessard 2024), often leading to a negative impact on the schooling of children. Immigrant youth who attend high schools in states that provide generous welfare benefits such as TANF, Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income, SNAP, etc., to immigrants and refugees are more likely to graduate from high school compared to peers who live in states giving less generous benefits (Bozick and Miller 2014), but, in many instances, undocumented families are ineligible to receive these benefits (Broder and Lessard 2024).

All the challenges mentioned above—financial struggles, poverty, school attendance in low-income neighborhoods, food insecurity, and undocumented students’ ineligibility for social welfare—are compounded as older immigrant students think about life after college. Once again, undocumented students and some immigrants on temporary visas are unable to apply for federal financial aid, which can drastically hinder their college potential (Averett et al. 2024). Even among those who do reach college, Enriquez et al. (2023) found that financial challenges continue and are exacerbated for students who are either undocumented or have undocumented parents.

2.5. School System Challenges

Mezzo and macro level challenges exist at the school and school district levels when it comes to equity for immigrant students, and some of this stems from discrimination and systemic policy injustices. Many school districts place pressure on principals and school administrators to ensure student success and improve academic achievement without providing resources to support immigrant students (DeMatthews and Izquierdo 2020). Beyond the aforementioned individual and family-level factors that pose challenges for immigrant students, there are also macro-level factors, such as the school and staff’s lack of preparedness and resources to serve immigrant students. Multiple studies have found that schools nationwide lack adequate resources and are therefore underprepared to attend to the needs of immigrant students (Borjian 2016; Crawford and Valle 2016). Many schools face a lack of resources, training, teacher shortages (including English as a Second Language (ESL)-certified teachers), lack of space, lack of enough bilingual mental health providers, and struggle with providing a decent education to recently arrived immigrant students (Booi et al. 2016; DeMatthews and Izquierdo 2020; Evans et al. 2022b). Also, a lack of awareness of the unique needs that immigrant children have can create a barrier to immigrant students in their education/educational path/academic path, etc. (Booi et al. 2016; Borjian 2016; Crawford and Valle 2016; Evans et al. 2018).

Policies and political rhetoric in the community can also influence a school’s ability to properly serve immigrant students. For example, because of the lack of proper guidance and knowledge, some school districts have forcibly enrolled undocumented students in alternative schools that were intended for children with correctional or behavioral needs (Booi et al. 2016). There is also a lack of understanding of policies and a failure to effectively communicate with parents regarding critical information, such as student records, report cards, education programs, and disciplinary proceedings (Booi et al. 2016). Concurrently, the school system faces its own burdens. As noted by Kirksey et al. (2020), schools are constantly influenced by immigration enforcement and political rhetoric. This is accentuated when there is high deportation activity near schools that impacts families of students, often leading to greater absences among students (Kirksey et al. 2020). Absenteeism has an influence on teachers and the ways they need to prepare for and conduct their classes.

At times, immigrant students and parents experience an adjustment period when using technology that differs from what the students use in their country of origin (Carhill-Poza and Williams 2020; Sattin-Bajaj 2015). This was exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic and the need to learn virtually from home. ESL teachers noted the extra steps needed in teaching immigrant students just to navigate the various technology platforms, while mainstream teachers assumed that all their students were adept at the nuances of technology and current applications (Carhill-Poza and Williams 2020). On top of this, many immigrant homes had a slow connection to the internet or no internet at all, which added stress to immigrant families as teachers were consistently assigning virtual homework and meetings (Carhill-Poza and Williams 2020). These limitations and lack of resources made the process of learning difficult for immigrant children and youth (Carhill-Poza and Williams 2020).

2.6. The Current Study

As previously mentioned, not all schools are prepared to address the needs of immigrant students (Borjian 2016; Crawford and Valle 2016), especially undocumented students and parents (Lovato and Abrams 2022). The peer-reviewed literature shows a variety of issues affecting this population and the negative effects, such as lower graduation rates and fewer students attending college (Koyama and Desjardin 2019). The purpose of this study is to analyze how the struggles portrayed in newspapers relate to or add to the story portrayed in the peer-reviewed literature, looking at how these struggles have impacted immigrant students in the US, and how these stories have created a barrier to academic success. The interplay of media stories and policy development (Entman 1993; Bou-Karroum et al. 2017) at the state and national levels is critical for researchers and community members to understand as we enter a new presidential administration in 2025 and think about the impact of what stories we tell, and how we tell them in regard to immigrants.

3. Methodology

According to Bowen (2009), document analysis is a qualitative research method most often used to provide context, to suggest questions to ask, or to triangulate data. In this study, we use document analysis as the primary form of data collection (though we discuss the findings in terms of triangulation with peer-reviewed literature in the discussion section below). The study aims to understand what knowledge is already available, thereby conducting a content analysis using newspaper articles as the documents or data source.

This study utilized a document analysis of newspaper articles that captured the challenges that immigrant students face in the US education system. Research assistants used the National Newspapers (Proquest) database to search for articles within a 10-year timeframe (January 2011–June 2021). This database includes articles from the following: The Baltimore Sun: 1990–present, The Christian Science Monitor: 1980–present, The New York Times + Book Review & Magazine: 1980–present, The New York Times in Español, 2020–, The Wall Street Journal: 1984–present, and The Washington Post: 1987–present. They searched for stories of immigrants in the USA that specifically related to educational experiences for students in grades preschool through high school. The articles were searched using the following criteria to locate relevant newspaper articles: (1) immigrant or foreign-born or refugee and (2) student or school or education or learning, (3) challenge or struggle or difficulty, (4) United States, and (5) child. The scope of this paper and our research questions is specifically around news that addresses immigrants, both documented and undocumented. While some immigrants may also be English Language Learners, they are not the focus of this paper, nor are groups of people that many people conflate with immigrants, such as the larger Latinx population.

The initial search yielded 1970 articles. Duplicate articles, articles in languages other than English, those written by the “Foreign Desk” of local newspapers, and articles that were not available as a full text were eliminated. Then, research assistants read the synopsis of articles (when present) or the first paragraph if a clear synopsis was not found, and they excluded articles related to college, Latinx/Asians (that did not specify being immigrants), and articles that did not focus on educational barriers. After all exclusion criteria were met, 67 articles were included in this study. The list of articles can be found in the Supplementary Materials section at the end of this paper.

For these 67 articles, the research assistants read the entire article and extracted basic information such as the following: newspaper of publication, date of publication, title, author, and grade level of students discussed in the article. They compiled the information into an Excel document. Then, a codebook was developed. The codebook was derived from a compilation of sources. First, the authors reviewed the MIPEX Immigrant Integration Policy Index and the major domains they consider in evaluating whether countries are welcoming to immigrants. We felt that this framework was relevant as we were looking for welcoming policies and practices in school systems. These domains include access to nationality, anti-discrimination, education, family reunion, health, labor market mobility, permanent residence, and political participation (MIPEX 2020). However, as we think about these in relation to children in schools, not all are completely relevant. Therefore, access to nationality, permanent residence, and political participation was not included as they were not relevant in the school system setting. Health was expanded to include mental health and trauma, family reunion was expanded to include the idea of parent versus child expectations, and labor market mobility was expanded to focus on financial well-being. Based on a recent article on challenges for unaccompanied immigrant children in schools (Evans et al. 2022a), the authors decided to add cultural norm differences, language, and school system challenges to the list. The resulting list of codes is as follows: language, financial, discrimination, mental health/trauma, school system challenges, cultural norm differences, difficulty navigating the community, peer/interpersonal struggles, parent versus child expectations, and a space for “other challenges”. This list of codes corresponds with the above literature review of peer-reviewed journal articles.

After the codebook was finalized and agreed upon by all research team members, two research assistants deductively coded (Vanover et al. 2021) the newspaper articles. For example, a newspaper article said, “From Burmese families in Catonsville to people from Nepal in East Baltimore, Patterson and other high schools are seeing students arrive with no English skills and little schooling. They are often burdened with trauma from the violence they fled” was coded as mental health. Another newspaper article said, “‘The money I get from the restaurant I use to pay all my bills’, he told us. ‘My phone, the rent, to send money to my mom’ in Colombia’. This was a common experience for the immigrant students we spoke to. During the pandemic, many of them have continued to work full-time” was coded as financial difficulty. During the coding process, research assistants noted when the articles mentioned the themes from the codebook (Labuschagne 2003) in the Excel document. Their notes included the content from the article, copied and pasted with quotation marks and paragraph numbers, and then analyzed by the research team in order to gain understanding and develop new knowledge (Corbin and Strauss 2008). After the initial coding, a third research assistant and one faculty member read over the articles and spreadsheet to review the codes as a verification process. The 67 articles yielded 1499 codes about various struggles.

4. Findings

4.1. Types of Struggles Faced by Immigrant Students Covered in Newspapers

In this section, we will discuss the results addressing the first research question, sharing the barriers immigrant students face as discussed in popular news sources. The themes identified included discrimination, mental health, language barriers, and financial stress associated with higher education in the US, lack of preparedness and resources to provide education, lack of familiarity with policy, lack of cultural knowledge about the US, lack of parent involvement, and work and familial obligations. We intentionally discuss discrimination and oppression first, as these fuel the systems and structures in the US that then perpetuate many of the other struggles mentioned below.

4.1.1. Discrimination, Oppression, and Xenophobia

Immigrant students are often victims of discrimination, oppression, racism, and xenophobia within the school system, similar to other people of color and minoritized groups. Two main sub-themes emerged in terms of discrimination faced in the school, which included the enrollment processes (which is a systems-level discrimination) and bullying victimization (more generally, an individual-level discrimination), both of which are discussed below.

4.1.1.1. Delayed/Diverted School Enrollment

A number of journalists have reported alleged discrimination against immigrants in the school enrollment process. One way schools have been making school enrollment more difficult for immigrants is through the required paperwork. For example, Guarino (2011) published an article about a law in Alabama where parents were required to provide citizenship status as part of the school enrollment process. This caused many undocumented families to remove their children from those schools for fear of being deported or criminalized. Notably, this law has been rescinded since then. Another article went on to note that in 2013, “20 school districts in New York State effectively kept undocumented youngsters out of school by imposing bureaucratic roadblocks such as insisting that the students’ parents produce Social Security cards” (Kirp 2015, para. 2). Mueller also found that students were prevented from enrolling based on their immigration status and reported, “Investigators have also alleged that the district failed to provide adequate instruction to non-English-speaking students, and discouraged students by requiring residency documentation” (Mueller 2015, para. 14). We also see discrimination in enrollment and admissions in various schools and even at the college level (Bachelder 2015; Brody 2019).

4.1.1.2. Bullying Victimization

Facing racial discrimination when trying to enroll in a school is hard. However, immigrant students face an additional struggle of dealing with discrimination through bullying by classmates and school staff once these students are in the school. In one article, an immigrant student from the Republic of Congo was picked on and teased due to her lack of US-normed hygiene and her appearance (Bowie 2015d). Gallagher (2017) documented how Muslim immigrant students have experienced times when other students pull their headscarves from their heads and address them as terrorists or part of ISIS. In another news story, a student threw a water bottle at an immigrant student’s face while calling them an ethnic slur, and the immigrant student pushed back. The staff escorted the immigrant student to the principal’s office and then arrested him, resulting in DHS involvement and immediate deportation proceedings as he was undocumented (Green 2018).

The data show that even school staff are perpetrators of bullying. For instance, a coach at one school faced legal action after being accused of calling out racial slurs during class (Green and Waldman 2018). Balingit et al. (2021) reported how Asian Pacific American parents and kids have shared stories of harassment and people yelling at them to “speak English” or “go back to your home country” (para. 15). In another story, bus drivers would refuse to pick up immigrant children, openly ridicule them, and encourage other students to join in. Lastly, a story disclosed how even teachers turn a blind eye to bullying or tell immigrants they are not cut out for challenging classes (Gallagher 2017; The Portland Press Herald Editorial Board 2017).

There are also examples of how bullying behaviors have an impact on parental decisions. For example, the fear of being harassed made some parents reluctant to access educational materials or free meals or even reach out to teachers or counselors for help (Cheah et al. 2021). During the COVID-19 pandemic period, “As school buildings start to reopen, Asian and Asian American families are choosing to keep their children learning from home at disproportionately high rates” because those families felt fear of infection in multigenerational homes and harassment at school (Balingit et al. 2021, para. 2).

4.1.2. Mental Health and Trauma

The next theme around mental health and trauma included three subthemes. The first theme was discussing traumatic experiences during the journey to the US and the ongoing mental health challenges that linger from this. The second theme centers on mental health challenges that emerge from new life experiences in the US, and the third theme is about barriers to accessing mental health care.

4.1.2.1. Trauma Histories

Many immigrant students enter US schools with a trauma history. For example, Bowie (2014) wrote that school officials have seen students come in with psychological or emotional trauma, such as girls who have been sexually assaulted during their journey across the border, and others who are overwhelmed and depressed. A year later, Bowie (2015a, 2015b) reported on similar issues and noted how some students are unable to recover from trauma while starting their new school life, often burdened with complex mental health conditions. Likewise, Cowley (2017) discussed how immigrant students brought to the US by their parents at a very young age often sustain identity confusion as they feel American growing up here but may not yet be citizens.

4.1.2.2. Mental Health Challenges in the US

Results also showed setbacks and traumatic experiences that occurred once in US communities. For example, Jordan (2019) recounted a four-year-old who was making steady progress in her pre-K class until her father was arrested by immigration agents in front of her, and later deported. Teachers noted how the little girl fell apart, and they could never get her back into learning mode. Jordan (2019) discussed how some immigrant students as young as fourth and fifth grade have been suicidal and depressed. Additionally, many undocumented students experience a deep sense of hopelessness. According to Semple (2011), many young students have dropped out of school because they say there is no point in staying in school if they will not attend college, believing they are not eligible to apply for financial aid. For example, Ivan, a student who immigrated from Mexico without documentation, said that even though his parents urged him to stay in school, they have no contact with the school and no oversight over his attendance due to his working to earn an income (Semple 2011).

4.1.2.3. Barriers to Accessing Help

Although there are support services available in the US and within US schools, these resources are still more inaccessible to immigrants for various reasons. One reason is the language barrier (Cheah et al. 2021). Other students are not even aware that resources exist. Brown (2012) recounted how a 19-year-old Ethiopian high school student missed out on support services when he had been in school for a month before he discovered that there was a counselor dedicated to helping immigrant students. Another story discussed the difficulty in adding more teachers, staff members, interpreters, and bilingual social workers who could adequately facilitate classes and counseling to students from other countries (Bowie 2015b, 2015d; Harris 2016) due to funding, school priorities, and a lack of qualified individuals.

4.1.3. Financial Stress Associated with Higher Education in the US

Some students pay for college through extensive credit card loans, which can be gruesome to pay back in the future. In Virginia, a student who graduated high school with honors is “ineligible for state resident status and struggling to pay annual tuition of $28,592—three times more than the $9908 her high school classmates pay” (The Washington Post Editorial Board 2013). Such is the harsh reality for many students. In one instance, Mitzie, an undocumented immigrant, has more than one credit card, and she uses them to help pay her tuition at a much higher interest rate than a student loan would carry (Cowley 2017). In 2017, the federal loans interest rate was fixed at 3.76 percent; however, private loans carry interest rates up to 11 percent (Cowley 2017). Higher percentages, such as those, can cause more financial difficulties for students after they have graduated. Private loans also carry fewer protections than federal loans. In another instance, Kang (2017) mentions how multiple stressors come together: “Without access to federal financial aid, I might not be able to go at all. I couldn’t work, couldn’t drive, couldn’t travel outside the country. Even worse was the terrifying possibility that my family might be discovered and deported” (para. 9).

Applying for financial aid can be a difficult process for immigrant students, especially for those who do not have legal documentation, such as permanent residency papers, student visas, and social security numbers. Undocumented immigrants remain ineligible for federal financial aid and state aid in some cases (Lovett 2010), making it challenging for immigrant families to afford college for their children. Students are told by their counselors and teachers to work hard, keep their grades up, and do well on the ACT, and they will be fine (Reckdahl 2020). However, the reality is that they were misled; even if they excelled in all the mentioned areas, the cost of higher education in the US is high without federal financial aid. Many even believe that “the acceptance letters didn’t mean anything” (Jordan 2014, para. 20).

4.1.4. Lack of Preparedness and Resources to Provide Education

A common theme found in the news was discussion of how many schools are underprepared to handle the ever-growing immigrant population. Subthemes included teacher preparedness, funding, and the exacerbation of COVID-19 and poor attendance.

4.1.4.1. Lack of Teacher Preparedness and Funding

Bowie (2015b, 2015c, 2017) wrote about how many teachers feel overwhelmed and underprepared to teach immigrant students while attending to the social-emotional needs of diverse cultural populations. Also, Bowie (2017) wrote about the new standards in English proficiency implemented by the Maryland State Department of Education that prevent students from advancing or testing out of ESL programs and how the new standards affect ESL teachers’ job security since part of the teacher’s performance evaluations are based on ESL student test scores.

Similarly, Harris (2016) wrote about the lack of resources in schools, teacher shortages, and how existing teachers would risk losing their seniority if they were to become ESL certified, which poses a risk during cutbacks. This causes anxiety among teachers because sometimes the school budget does not allow them to restore all the positions that had been eliminated (Stein 2021). Nonetheless, the increase in immigrant students also challenges the federal government as it provides school funding. Politically, some people are against increasing resources and incentives for the acclimation of immigrant students because they do not believe immigrants have the same right to opportunity in this country and/or that it will unfairly cost taxpayers more (Brown 2016).

4.1.4.2. Impacts of COVID-19

During the coronavirus pandemic, immigrant communities were hit hard. Many immigrant students and families had to focus on their financial burdens instead of their education. A local nonprofit director stated, “If their jobs are in the informal economy, and their housing arrangements are informal--and with an additional technology access barrier--their kids’ school enrollment is the first thing to go” (Stein 2021, para. 7).

4.1.5. Lack of Familiarity with US Culture and Policy

Another theme identified in the news was newcomers’ lack of cultural knowledge about school and school policy. Some new immigrant students may struggle to adjust to US classrooms because they are less familiar with the norms and expectations the school has for them. For example, “‘While there are countless differences between and among members of different ethnic groups, children of immigrants of Asian heritage seem to have particular trouble asking for help because to do so has been seen as a failure’, says Ms. Belani, who was born in France to Indian parents and worked as a peer counselor and residential adviser while at Stanford” (Wang 2016, para. 10). At times, a lack of knowledge of policy can impact service access. For example, one news article mentioned “Several teens, part of a District-based advocacy group, said at a meeting with Henderson that immigrant students and their parents often struggle to receive the translation services and other assistance they need to understand their new school system” (Brown 2012, para. 2). Moreover, many students face challenges not only because of lacking language skills but also because of lacking years of formal education. Bowie reported that one coordinator for English language acquisition and international students said, “Many are not literate in Spanish … and may only have gone to school up to the first or second grade. They may have huge gaps” (Bowie 2014, para 6).

4.1.6. Language Barriers

Language barriers are a common struggle for many new immigrant students. The complications that come from a lack of English language skills impact the classroom learning directly, but also go far beyond that and, in many ways, hinder all of the themes identified in this study. A lack of language skills can have a big impact on school life and academic performance, leading some immigrant students to drop out because they can’t catch up or comprehend the curriculum. Bowie (2015a) mentioned, “Too often the students aren’t able to adjust to a rigid educational system that gives them just a few years to learn a new language and master four years of high school curriculum” (para. 4). Williams and Carhill-Poza (2020) mention “Many immigrant students who were still learning English found it difficult to communicate complex ideas through texting or commenting functions. Rather, they preferred the more nuanced conversations that they could have with their teacher and peers in person” (para. 9).

In a different article, Bowie (2015c) noted, “Even though their students may have limited English, they must take the statewide exams” (para. 16). Parents and caregivers with limited language skills struggle to help their children with schoolwork effectively and also struggle to communicate with teachers and school staff. Cheah et al. (2021) mention that with 30% of Asian immigrant families reporting limited English proficiency, these families are more difficult to engage in the school community.

During the pandemic, many ESL learners’ families were frustrated because they were blocked by a language barrier and could not figure out how to access classes or receive help (Alissa 2021). Solomon, a senior from Ethiopia, discussed how he missed out on support services, not realizing the school had a counselor. Speaking on behalf of his immigrant peers, Solomon noted, “Most students feel that if they don’t know English, they don’t know who to ask” (Brown 2012, para. 9). A sixth grader, Taniya, found that the little English she had acquired since moving to the US in 2019 was slipping away due to remote learning (Kim 2020). Even with the vast amount of learning that now takes place through written online communication (i.e., email, Google assignments, etc.), some immigrant students have struggled to translate the teacher’s assignments and feedback (Carhill-Poza and Williams 2020).

4.1.7. Factors That Deter Parent Involvement

The news articles discussed the ways that US educational institutions deter immigrant parents from engaging in the educational journeys of their children despite a desire to do so. An adult ESL program coordinator at a Community College said parents “want to contribute to their children’s education by checking their homework or reading books together” (Michaels 2017, para 6) but went on to explain barriers to actually doing so. Schools are not always willing or able to provide translation or interpretation for parents whose native language is not English, misinformation about the role of school officials, and the need to work to alleviate poverty, all of which can lead to less parental involvement in schools. Semple (2011) discussed how a mother lacked English skills and therefore never spoke to school staff about her child’s performance or attendance as the teacher had not gone the extra mile to reach out and make information available. Additionally, many immigrant parents work multiple jobs to provide for their families, which often leaves them with little or no time to volunteer despite their desire to do so (Semple 2011). Additionally, some immigrant parents have expressed fear of contacting school officials, unsure if it could lead to deportation or other ramifications. Similarly, Michaels (2017) notes that inefficient communication between parents and school staff is a barrier to positive educational outcomes.

4.1.8. Work and Familial Obligations

The newspaper articles discussed how work and family obligations often pull students from their studies, and subthemes included why students feel pressure to work, and how familial obligations require their concentration and have a harsh impact on their ability to continue their education.

4.1.8.1. Pressure to Work

At a Public Charter School in Washington, D.C., the school’s executive noted that “our students are the working poor”, and “it’s a juggling act to work all night, then come to school before leaving for your second job” (Chandler 2015, para. 15). Kanyamanza (2020), discussed how “high school students often take part-time jobs to meet personal needs or to contribute to the family” (para. 4). Many students “feel their first priority is not their education but working to pay back the smuggler who brought them to the U.S., a bill that she believes often runs between $6000 and $10,000. It can take a young person as long as five years to repay the debt” (Bowie 2014, para. 35). In this unfortunate situation, students may have to work more than one job to pay their debts while trying to complete their education.

4.1.8.2. Impact of Obligations Outside of School

In addition to this, having to divide their time between attending school and meeting financial obligations creates immense stress on the students, which ultimately may lead them to drop out and solely focus on providing for their families. For example, one news article mentions “When students drop out, it is usually because they have to earn money or babysit at home” (Constable 2014, para. 32).

4.2. Which Newspapers Cover Stories Regarding Immigrant Struggles

To answer the second research question, Table 1 below shows the number of stories about immigrant student struggles in US education found in each newspaper from 2011 to 2021. This is a compilation of all codes recorded about various struggles (i.e., language, financial difficulty, discrimination, social and peer-to-peer struggles, cultural differences, and struggles navigating the community) across the articles in our sample that were published by that newspaper. As seen in Table 1 below, The Wall Street Journal produced the largest amount of content discussing struggles that immigrant students face, with 531 codes, followed by The New York Times with 465 codes and The Washington Post with 349. The Christian Science Monitor and The Baltimore Sun produced the smallest amount of content, with only 100 and 54 codes (respectively) relating to immigrant struggles.

Table 1.

Frequency of challenges faced by immigrant students in newspaper articles from 2011–2021.

4.3. When Articles About Immigrant Student Struggles Were Published

To answer research question number three, we created the graph below, which shows the number of articles published each season over the ten-year span of this study. As illustrated in Figure 1, we found the greatest number of articles published about immigrant struggles in school during two time points: Spring 2015 through Winter 2016 and again Summer 2020 through Spring 2021. While these were the peaks, there was continually higher coverage from Spring 2015 through Winter 2016 than any other span over the 10 years. Notably, the total number of articles that met inclusion criteria in each time period was five or fewer articles. Given the relatively low number of articles, these results should be interpreted cautiously.

Figure 1.

Articles published by season 2010–2021 (N = 67).

5. Discussion

Most of the stories published in newspapers that met our inclusion criteria prominently portray negative issues about immigrant students and immigration policies (e.g., Alissa 2021; Bowie 2014, 2015a, 2015b, 2015c, 2015d; Cheah et al. 2021; Kirp 2015; Williams and Carhill-Poza 2020). These stories may create a negative connotation in the eyes of the public, potentially increasing biases and having a negative impact on the lives of immigrants. Given the recent presidential change in the US, and the anti-immigrant policies that are being enacted, there is a reminder of the need to think critically about what we read or publish in the news. The media has the ability to influence policy changes (Entman 1993; Bou-Karroum et al. 2017), and, therefore, as we think about policy and advocacy work, it can be important to engage media stakeholders in sharing the stories that will work towards a more inclusive society. The MIPEX framework is used to evaluate the extent to which policies are immigrant-friendly across various countries (MIPEX 2020). The last update was in 2019, where the US overall ranked as “slightly favorable” and education specifically ranked “favorable” (MIPEX 2019), and given the recent policy changes in the US, we are likely to rank much lower. The media narrative in the US is ever-changing, especially given that some people are now fearful of speaking out for fear of deportation or other ramifications (e.g., Goldberg 2025), and so this has an impact on the role of the media in telling narratives, especially true narratives of discrimination against immigrants.

This section will discuss how the findings relate to the existing peer-reviewed literature on immigrant students in the US. We also provide implications for future research, practice, and policy, and discuss the limitations of the study.

5.1. Discrimination, Bullying, and School Enrollment

As discussed in the literature review, discrimination in the US exists at the individual, institutional, and structural levels, and, therefore, the impact of discrimination is embedded in our policies and systems and impacts every aspect of life for immigrants. Discrimination can be a key negative factor in the development of children and research shows that immigrant children who are victims of discrimination within the school setting may have a more difficult time adapting to school norms, language differences, and the culture of the community in which they live, adding difficulty to already existing struggles of navigating a new school (Báez et al. 2024). Similarly, the analysis of newspaper articles in this study shows that immigrants are discriminated against to the point of being bullied, teased, called names, and ignored by both classmates and school staff (Cheah et al. 2021; Cowley 2017; Gallagher 2017; Green and Waldman 2018; Hwang 2019; Kirp 2015). While these are individual experiences of discrimination, they are institutionalized in the ways our schools operate and within policies that exist, and, as discussed in the MIPEX framework, it is also a major challenge of integrating into communities.

But there can also be discrimination in how teachers or administrators treat a student. For example, there were news articles that speak negatively about immigrant children and some that show immigrant children being criminalized when others would perhaps not be in the same situation (Kirp 2015; Matthew 2012; Reckdahl 2020; The Washington Post Editorial Board 2013). This highlights the benefit of having standard operating procedures or policies that explain consequences and hold the administration accountable for not discriminating against immigrants or people of color.

5.2. Difficulties Adapting to a New Culture and Overcoming Mental Health Challenges

The news stories assessed in this study found multiple areas where students struggle to understand the cultural norms in the classroom, which can be compounded when students are dealing with mental health and trauma. Similarly, the peer-reviewed literature noted that immigrant students faced a lack of support networks (Patel et al. 2016; Szlyk et al. 2020) and that schools often fail to provide mental health support and help to immigrant children who need it the most (Bankston 2014; Hos 2020; Patel et al. 2016). Hasson III et al. (2022) describes that the greatest service need for unaccompanied children who arrive to the US is support academically and in their adjustment to US schools. Some authors suggest ways to provide support to new arrivals, such as an orientation and ensuring parental knowledge of graduation requirements (Evans and Reynolds 2024). Positive support networks are known to open doors to opportunities for new immigrants (Bankston 2014). The newspaper articles talked about mental health in a way that was colloquial and easily understood by people, which may help the general public understand the stressors and implications on immigrant families. We feel this is a strength of this research to highlight the human side of mental health and note that many news stories even include images that can help build empathy.

5.3. Language Barriers and Lack of Resources in Schools

Language barriers were a frequent theme found in the newspaper articles, and the most cross-cutting theme. This is likely since the systemic inequities and discrimination above exacerbate the individual-level language barriers for immigrant families. Language barriers were discussed in terms of a barrier to classroom learning and standardized testing scores (Bowie 2015c), but were also discussed as an intersectional point with many other themes found in this study. For example, bullying due to accent and language (Cheah et al. 2021), gaps in educational history (Jordan 2019), cultural misunderstanding due to language (Kirp 2015), inability to as for mental health assistance (Cheah et al. 2021), and inability of the school district to hire bilingual staff to help meet student needs (Harris 2016).

The results of this study show a variety of language barriers affecting content acquisition and relationships between students, staff, and the members involved in the kids’ educational process. These challenges are well documented in the academic literature as well. One nuance captured in the personal stories shared in the news is how these barriers impact a person’s life. In the academic literature, language acquisition is often quantified and compared to US-born students (Barrett et al. 2012; Umansky et al. 2022), but here we can better understand the emotional stressors that come alongside a language barrier, which is a noteworthy finding to be shared with teachers and school mental health professionals. Limited English proficiency, together with unprepared staff and teachers, and limited bilingual staff, create a barrier to education that in the long run, and affects the educational success of children (Booi et al. 2016; Borjian 2016; Bowie 2015a, 2015b, 2015c, 2015d; Carhill-Poza and Williams 2020; Crawford and Valle 2016; Semple 2011).

5.4. Parental Expectations, Family Involvement, and Financial Stress

The news stories analyzed in this study depict how the lack of involvement of immigrant parents in the educational system can have negative effects, such as leading to children dropping out of school and a lack of communication between parents and school officials (Semple 2011).

However, the newspaper articles showed the reality of how difficult it is to engage in your child’s education and the many responsibilities that immigrant families hold, and the many barriers and discriminatory practices our public schools use to keep immigrant families out. While the peer-reviewed literature discussed many financial struggles experienced by immigrant families, in the newspaper analysis, the stories all revolved around financial access to higher education. More specifically, our findings showed a lack of resources and financial opportunities/scholarships available to immigrant students for higher education (Kantamneni et al. 2016), which is consistent with the peer-reviewed literature (Evans and Unangst 2020; Casellas Connors et al. 2025). While numerous articles in the search addressed topics related to COVID-19 (e.g., online learning), it was surprising that more did not discuss the financial implications that immigrants faced during this time period, with loss of wages and inability to access some governmental assistance through the CARES Act.

5.5. Coverage by Newspapers

The results showed more stories about immigrants’ negative educational experiences in The Washington Post and The New York Times than in any other newspaper. In 2023, the foreign-born population reached 47.8 million people, that is, immigrants made up 14.3% of the people living in the US (Batalova 2024). The number of immigrants living in New York is one of the largest in the country with 22.8% of the state’s overall population being immigrants (American Immigration Council 2022), and more than 40% of New York City’s total population (Adams and Castro 2022), which could help explain why they cover these stories more frequently. While immigrants were only about 14% of the population in Washington, D.C (American Immigration Council 2020), it is the nation’s capital. Similarly to our interpretation of the next research question, we suspect that presidencies have an impact on news coverage around immigration and hypothesize that this is one reason these newspapers saw the highest coverage of immigrant struggles.

Results showed that Spring 2015 through Winter 2016 and again Summer 2020 through Spring 2021 were the two time periods in which the selected newspapers published the most stories about immigrant students’ struggles. One speculation for this timing could be that former President Donald Trump was campaigning for president in 2015, and immigration was a hot topic during the presidential campaign. The media may have been inclined to give more coverage to topics addressing immigrants and the difficulties they experienced adjusting to the US. Around the same time, from Spring 2015 through Winter 2016, there was continually high coverage as compared to any other timespan over the 10 years in this study. Obama made many changes to immigration policy and was heavily criticized from both sides of the political spectrum (Chishti et al. 2017), and that likely influenced the number of newspaper articles during this time. The second time there was an increase in the number of articles published covering news about immigrants was during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Immigrants and migration patterns were drastically impacted as a result of policies such as Title 42 and the Migrant Protection Protocols. Title 42 is a public health policy that exists to ensure disease is not spread across borders and was used to expel and prevent immigrants from entering the US out of fear of transmitting COVID-19; yet many experts say it was unfairly harming asylum seekers and other vulnerable immigrants (Fabi et al. 2022; Martínez et al. 2024). Migrant Protection Protocols (commonly referred to as MPP or “Remain in Mexico Program”) was a Trump policy that mandated that people seeking asylum await their immigration hearing in Mexico (where they experienced unsafe and unsanitary conditions) rather than in the US (Rabin et al. 2022). Additionally, immigrant students struggled more during online learning as a result of COVID-19 (Abraham 2020; Williams and Carhill-Poza 2020) and so the struggles may have been more pronounced.

The analysis of newspaper articles also raises discussion around the media in general. Since 2025, media outlets across the United States have been criticized, questioned, and cautioned regarding fact-checking and biased comments. While these data were collected prior, when the majority of community members deemed the media trustworthy, a key takeaway from this study is to reiterate the need for media coverage to avoid negative biases, false information, and to stop perpetuating stereotypes around immigrants (Education Writers Association 2024). Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution, knowing that media sources could be biased, and that if they are perpetuating negative stereotypes about immigrants, they could do significant harm. Nonetheless, the study brings to light some aspects that have been missing thus far in the peer-reviewed literature and therefore helps to give a wider view of the issue.

5.6. Limitations

This research utilized newspapers, which is a strength as it broadens the scope of what we know about immigrant children and their education from what is normally discussed in the peer-reviewed literature. However, this also poses a limitation because media sources can be biased and are not held to the same research standards as others. Given the political climate in different areas of the country over the years, and the reporters’ political views, the types of immigrants and their highlighted challenges may be skewed. Additionally, this analysis did not take into account the age or grade level of the people discussed in the news articles, in part because not all included these details, and we know from the study of human behavior (Rogers 2020) that the findings would have a different impact and implications based on the age. For example, bullying is experienced and internalized differently at age 6 than at age 16, and also, what we can do about it is different. Lastly, there is a limitation in terms of the content shared in a news story. Typically, the person being interviewed is seen as an expert. If they use terms such as depression or bullying, this is their understanding or perception of the term, which may not indicate depression in the same manner as someone who has been evaluated by a licensed clinician and scored above the cutoff point on a depression scale. Nonetheless, this study intentionally employed the use of newspaper articles and news media, as it is an important source of data regarding immigrant families.

6. Recommendations and Implications

Below, we provide implications for research, practice, and policy based on the findings of our analysis of newspaper articles. As noted below, many of these implications are also supported by the peer-reviewed literature.

6.1. Future Research

This study focused mostly on the struggles faced by immigrants, but an important factor to add to the full story is the strengths and resilience of immigrants, as well as the help they receive. Therefore, future research should be qualitative in nature and capture these strengths. As discussed by Kantamneni et al. (2016), future research should look at coping mechanisms for immigrant students and the ways that students build and utilize resilience in the educational system. Additionally, the document analysis in this study did not locate many articles discussing immigrant students in pre-kindergarten, kindergarten, or Head Start programs. Therefore, we suggest that future research look at early childhood education among immigrant families and intentionally conduct analyses within each age range (early childhood, elementary, middle, high school, and higher education), and provide a comparison of facilitators and barriers across age groups to deepen the analysis.

6.2. Implications for Practice

This study has numerous implications for social service practice with immigrant students. First, our research showed that trauma was a significant barrier to educational success for immigrant and refugee youth. Therefore, we want to ensure that teachers understand when a referral should be made and to whom. Many schools employ multiple people who work with children regarding social and emotional needs, such as school social workers, school psychologists, and counselors, and this can lead to confusion among school staff in terms of who provides which services and how to reach the support needed for immigrant students most effectively. At the same time, the school cannot provide all resources in-house, and so, as discussed by Evans et al. (2022b), schools should work to establish relationships with community-based agencies that serve immigrants and refugees so that staff can complete a warm handoff when services are better suited outside the school. Other successful community-school partnerships might include applying for grants (e.g., Refugee School Impact Grant (RSIG), a federal grant program) together, or having staff from the refugee agency come into the school to train teachers and school staff.

Second, our findings discussed evidence of bullying victimization. Bilingual and culturally responsive school administrators can make parents and students feel more comfortable with the information they are presented and feel welcomed into the education system through immigrant-friendly policies, and personal communication (DeMatthews and Izquierdo 2020; Gonzalez 2018). Districts should consider the needs of immigrant students when setting up their policies and workflows to ensure that everyone receives the services they need to succeed. For example, many schools already implement bullying prevention programs. Still, research indicates that these programs are not always inclusive of the immigrant experience nor effective in reducing bullying victimization for immigrant students (Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger et al. 2024), and, therefore, programmatic or policy improvements could be made to these programs.

Lastly, the results showed that professionals felt unprepared to serve immigrant clients, and, therefore, more training is needed for teachers, administrators, and school counseling staff. Topics might include best practices in orientation for new immigrant students (Evans and Reynolds 2024), understanding how to work with students with little technological skills (Carhill-Poza and Williams 2020), better understanding cultural and educational backgrounds (including gaps in education) of immigrant students (Evans et al. 2018; Szlyk et al. 2020), and understanding the unique needs of undocumented students (Borjian 2016; Crawford and Valle 2016). The Center on Immigration and Child Welfare Initiative has a free self-paced bilingual training module on immigrant inclusivity that could be very beneficial (The Center on Immigration and Child Welfare Initiative 2025). Increased teacher training could increase preparedness and perhaps improve some of the other struggles mentioned in this paper, such as the referral process for mental health services, or decrease oppression and discrimination perpetuated by teachers and school staff. Given the current administration’s priorities and interest in dismantling the federal Department of Education, we suggest increasing access to training and funding opportunities at the individual school, county, or state level, given that any increase for this population is not likely at the federal level. For example, local foundations may want to create funding opportunities for equity in education for immigrants.

6.3. Policy Implications

At a policy level, we can also do more. Specifically, the results showed that there are significant barriers to accessing higher education for immigrant students. Therefore, we can advocate to extend in-state tuition policies to immigrant youth (Bozick and Miller 2014) and increase awareness of state-based financial aid (e.g., Maryland Higher Education Commission 2023), which could greatly impact the future educational and career possibilities of immigrant youth. State-based financial aid is currently available in about one-third of the states (Averett et al. 2024) and increases access to higher education and long-term wealth for families.

The current presidential administration plans to make financial cuts for public education (Lieberman 2024), and, therefore, ongoing advocacy is going to be needed to ensure that the needs of immigrant children continue to be met and that staff providing services have the resources they need. Currently, all children in the US are able to attend school regardless of immigration status as established by a court case Plyler v. Doe (Supreme Court of the United States 1982), and we need to ensure this protection is not reversed.

7. Conclusions

Immigrant students face multiple barriers when they enter school in the US. Compounding the issue, schools are challenged to prepare newcomers (who do not always speak English) with limited training and funding (Bowie 2015b, 2015d; Harris 2016) to help them transition to universities or colleges (Jordan 2014; Kang 2017), or to prepare them to join the workforce (Kantamneni et al. 2016). There are also challenges related to general knowledge of the country and educational system (Brown 2012; Bowie 2015a), language barriers (Bowie 2015c; Williams and Carhill-Poza 2020), and a deficiency in school structures and system to adequately welcome and serve new immigrant students (Bowie 2017; Brown 2012; Harris 2016; Kirp 2015). These challenges are also aggravated by both intentional and unintentional biases, racism, discrimination, and a sense of fear created in the population that shows immigrants and newcomers as causing problems or being detrimental to the country’s system (Bachelder 2015; Brody 2019; Guarino 2011; Kirp 2015). Immigrant students can achieve further educational success if they are provided with sufficient emotional, informational, and financial support to navigate the American educational system (Evans and Reynolds 2024).

Even though some articles have tried to accentuate the positive stories and programs that aid immigrants, most of the stories seen in newspapers from 2011 to 2021 are negative and often negate the benefits of bringing new people to the country.

The implications and recommendations from this study are vast and intersect with various stakeholders. Implications for research suggest a need for primary data collection to hear the voices of students and their parents. The practice implications include a need for enhanced training around media narrative and avoiding stereotypes and harmful narratives, which is more important now than ever. The policy recommendations include creating more welcoming policies at the school level, increasing funding assistance for higher education, and advocacy efforts for immigrant student rights under the new presidential administration (ACLU 2025).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/socsci14060358/s1, Table S1: Articles published by season 2010–2021.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.E. and J.L.; methodology, K.E.; formal analysis, K.E.; data curation, S.G.; writing—original draft, K.E., J.R. and S.G.; writing—review and editing, K.E. and J.L.; supervision, K.E.; project administration, K.E.; funding acquisition, K.E. and J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Maryland Baltimore County, Hrabowski Innovation Grant 2021–2023 award cycle.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the student researchers, Shahana Abdul Javed and Xiaoming Li, who helped in the early qualitative coding processes before the publication process began.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abraham, Roshan. 2020. Only Statewide Program to Help Community College Students Graduate Seeing a Spike in Need. Next City.Org. Available online: https://nextcity.org/urbanist-news/statewide-program-help-community-college-students-graduate-seeing-spike (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- ACLU. 2025. Know Your Rights: Immigrants’ Rights. Available online: https://www.aclu.org/know-your-rights/immigrants-rights (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Adams, Eric L., and Manuel Castro. 2022. Report on New York City’s Immigrant Population and Initiatives of the Office. NYC Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs. Available online: https://www.nyc.gov/assets/immigrants/downloads/pdf/MOIA_WeLoveImmigrantNYC_AR_2023_final.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Alissa, Widman Neese. 2021. Language Liaisons Help to Bridge Gap: Program Assists Students Learning English Online. The Baltimore Sun, February 7. Available online: https://digitaledition.baltimoresun.com/tribune/article_popover.aspx?guid=2818d962-d891-41cd-8b2c-cdfe2e44a7e2 (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- American Immigration Council. 2020. Immigrants in the District of Columbia. Available online: https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/immigrants-in-washington-dc (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- American Immigration Council. 2021a. Immigrants in the United States [Fact Sheet]. Available online: https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/sites/default/files/research/immigrants_in_the_united_states_0.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- American Immigration Council. 2021b. U.S. Citizen Children Impacted by Immigration Enforcement [Fact Sheet]. Available online: https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/us-citizen-children-impacted-immigration-enforcement (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- American Immigration Council. 2022. Immigrants in New York. Available online: https://map.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/locations/new-york/# (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Andrés Bolado, Lidia. 2023. Breaking Language Barriers: Teachers’ Strategies for Supporting Immigrant Children with Limited Language Proficiency. Åbo Akademi University. Available online: https://www.doria.fi/handle/10024/187221 (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Annie E. Casey Foundation. 2021. Understanding the Children of Immigrant Families. Available online: https://www.aecf.org/blog/who-are-the-children-in-immigrant-families (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Assari, Shervin, Frederick X. Gibbons, and Ronald L. Simons. 2018. Perceived discrimination among black youth: An 18-year longitudinal study. Behavioral Sciences 8: 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averett, Susan, Cynthia Bansak, Grace Condon, and Eva Dziadula. 2024. The Gendered Impact of In-State Tuition Policies on Undocumented Immigrants’ College Enrollment, Graduation, and Employment. Journal on Migration and Human Security 13: 64–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachelder, Kate. 2015. Harvard’s Chinese exclusion Act: An immigrant businessman explains his legal challenge to racial quotas that keep Asian-Americans out of elite colleges. Wall Street Journal, June 5. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/harvards-chinese-exclusion-act-1433543969 (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Balingit, Moriah, Hannah Natanson, and Yutao Chen. 2021. As Schools Reopen, Asian Americans Students Are Missing from Classrooms. The Washington Post, March 4. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/asian-american-students-home-school-in-person-pandemic/2021/03/02/eb7056bc-7786-11eb-8115-9ad5e9c02117_story.html (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Bankston, Carl L., III. 2014. Immigrant Networks and Social Capital. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, Alice N., John P. Barile, Esther K. Malm, and Scott R. Weaver. 2012. English proficiency and peer interethnic relations as predictors of math achievement among Latino and Asian immigrant students. Journal of Adolescence 35: 1619–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batalova, Jeanne, and Michael Fix. 2023. Understanding Poverty Declines Among Immigrants and Their Children in the United States. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/mpi-poverty-declines-immigrants-2023_final.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Batalova, Jeanne. 2024. Explainer: Who Are Immigrants in the United States? Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/content/who-is-us-immigrant (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Báez, Johanna Creswell, Padma Swamy, Adriana Gutierrez, Ana Ortiz-Mejias, Jacquelyn Othon, Nohemi Garcia Roberts, and Sanghamitra Misra. 2024. Insights for clinical providers and community leaders: Unaccompanied immigrant children’s mental health includes caregiver support. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birman, Dina, Traci Weinstein, and Sarah Beehler. 2007. Immigrant youth in U.S. schools: Opportunities for prevention. The Prevention Researcher 14: 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bolter, Jessica. 2022. Immigration Has Been a Defining, Often Contentious, Element Throughout U.S. History. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/immigration-shaped-united-states (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Booi, Zenande, Caitlin Callahan, Genevieve Fugere, Mikaela Harris, Alexandra Hughes, Alexander Kramarczuk, Caroline Kurtz, Raimy Reyes, and Sruti Swaminathan. 2016. Ensuring Every Undocumented Student Succeeds: A Report on Access to Public Education for Undocumented Children. In Georgetown Law. Washington, DC: Human Rights Institute. Available online: https://www.law.georgetown.edu/human-rights-institute/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2017/07/2016-HRI-Report-English.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Borjian, Ali. 2016. Educational resilience of an undocumented immigrant student: Educators as bridge makers. CATESOL Journal 28: 121–39. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1119615.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Bou-Karroum, Lama, Fadi El-Jardali, Nour Hemadi, Yasmine Faraj, Utkarsh Ojha, Maher Shahrour, Andrea Darzi, Maha Ali, Carine Doumit, Etienne V. Langlois, and et al. 2017. Using media to impact health policy-making: An integrative systematic review. Implementation Science 12: 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, Glenn A. 2009. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal 9: 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowie, Liz. 2014. Maryland schools see influx of immigrants from Central America. The Baltimore Sun, August 24. Available online: https://www.baltimoresun.com/2014/08/24/maryland-schools-see-influx-of-immigrants-from-central-america-2/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Bowie, Liz. 2015a. Immigrant Schools Aim to Get Students with Little Education Through High School. The Baltimore Sun, November 28, updated 30 June 2019. Available online: https://www.baltimoresun.com/education/bs-md-immigrant-school-20151116-story.html (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Bowie, Liz. 2015b. Maryland lawmakers call for better education, more support for new immigrants. The Baltimore Sun, November 12. Available online: https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/investigations/bs-md-new-americans-react-20151111-story.html (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Bowie, Liz. 2015c. State panel looking at ways to improve education of immigrant children. The Baltimore Sun, December 21. Available online: https://www.immigrationadvocates.org/news/article.585672-State_panel_looking_at_ways_to_improve_education_of_immigrant_children (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Bowie, Liz. 2015d. The struggle with English. The Baltimore Sun, November 8. Available online: https://www.pressreader.com/usa/baltimore-sun-sunday/20151108/281496455165763 (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Bowie, Liz. 2017. English Learners Face a Setback: New Standards Will Hold Back Additional Immigrant Students. The Baltimore Sun, June 26. Available online: https://digitaledition.baltimoresun.com/tribune/article_popover.aspx?guid=37c1b960-8308-41a3-b037-6865b49fad96 (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Bozick, Robert, and Trey Miller. 2014. In-State college tuition policies for undocumented immigrants: Implications for high school enrollment among non-citizen Mexican youth. Population Research & Policy Review 33: 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Broder, Tanya, and Gabrielle Lessard. 2024. Overview of immigrant eligibility for federal programs. National Immigrant Law Center. Available online: https://www.nilc.org/issues/economic-support/overview-immeligfedprograms/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Brody, Leslie. 2019. High Test Scores Earned Them Seats at Stuyvesant; a Tough Question Is Whether to Accept: Among the Challenges of Adding Racial Balance is the Fear of Isolation Among Some Prospective Students of Color. Wall Street Journal (Online), March 30. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/high-test-scores-earned-them-seats-at-stuyvesant-a-tough-question-is-whether-to-accept-11553972519 (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Brown, Christia Spears. 2015. The Educational, Psychological, and Social Impact of Discrimination on the Immigrant Child. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/educational-psychological-and-social-impact-discrimination-immigrant-child (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Brown, Emma. 2012. Immigrant Students ask D.C. Schools Chief for an Assist. The Washington Post, September 6. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/immigrant-students-ask-dc-schools-chief-for-an-assist/2012/09/06/fd43dbc4-f87e-11e1-8b93-c4f4ab1c8d13_story.html (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Brown, Emma. 2016. As Immigration Resurges, U.S. Public Schools Help Children Find Their Footing. The Washington Post, February 7. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/as-immigration-resurges-us-public-schools-help-children-find-their-footing/2016/02/07/6855f652-cb55-11e5-ae11-57b6aeab993f_story.html (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Bu, Liping. 2020. Confronting race and ethnicity: Education and cultural identity for immigrants and students from Asia. History of Education Quarterly 60: 644–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiman, Abby. 2020. Key Findings About U.S. Immigrants. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2020/08/20/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Carey, Roderick L. 2019. Am I smart enough? Will I make friends? And can I even afford it? Exploring the college-going dilemmas of Black and Latino adolescent boys. American Journal of Education 125: 381–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhill-Poza, Avary, and Timothy P. Williams. 2020. Learning “anytime, anywhere”? The imperfect alignment of immigrant students’ experiences and school-based technologies in an urban US high school. Comparative Education Review 64: 428–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casellas Connors, Ishara, Kerri Evans, Lisa Unangst, and Sofia Chunga-Pizarro. 2025. Reframing Higher Education for Refugees: Pathways, Policies, and Community Cultural Wealth. The Journal of Higher Education, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]