Abstract

(1) Background: The under-representation of women in STEM fields, particularly in areas such as physics and computing, is far from being resolved. This gender gap has complex causes. This research was carried out to understanding how physics teachers in Portugal are aware of the existence of a gender gap and how they use or are willing to use girl-friendly strategies in their lessons; (2) Methods: A sample of 55 Portuguese physics and chemistry teachers from the third cycle of basic education and secondary education and an 8-item survey were used. (3) Results: The results show that most teachers perceive girls’ participation in physics as satisfactory, and that girls do not perceive a gender gap and are interested in the subject, but may not be aware of the concept and application of girl-friendly strategies. (4) Conclusions: No correlation was found between gender or years of service and interest in the topic of girl-friendly strategies. Further research with a more diverse sample is needed to generalize these findings.

1. Introduction

The invisibility of women in the history of science, which was essentially dominated by men until the 20th century, still accompanies educational environments today, with direct repercussions on careers related to STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths) (I. Fernandes and Cardim 2018). Despite the efforts of international organizations such as the United Nations (Nações Unidas 2023), which stood out in promoting actions to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and set a target for equality and empowerment of women, both in terms of ‘Quality Education’ (SDG 4) and ‘Gender Equality’ (SDG 5), the number of women in STEM careers remains below that of men. According to Vidor et al. (2020) in 2017, only 28.8% of science and technology workers worldwide were women. In Portugal, women account for only 38% of the workforce (tertiary sector) in STEM fields, according to 2020 data from the Department of Statistics of the International Labour Organization (ILOSTAT 2023). On the other hand, in a recent study involving 190 12th grade students in Portugal, interest in pursuing studies in engineering and technology was higher in boys, and the difference is statistically significant compared to girls (Ribeirinha et al. 2024).

The under-representation of women in STEM fields is a problem for several reasons. Firstly, it is a problem because it is estimated that more workers will need to be trained in these fields in the coming decades and secondly, because the absence of women (who represent about half of the population) also limits innovation and new scientific discoveries, thus reducing global competitiveness. In addition to these two aspects, salaries in STEM fields are on average 33% higher than those in non-STEM fields, and as a result, the wage gap between women and men is perpetuated, contributing downstream to a society less committed to equality opportunities for men and women (Miner et al. 2018). The 2023 report ‘Diversity and STEM: Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities’ indicates that the average salary of a worker in STEM fields is around 38% higher than in a non-STEM field (National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES) 2023). This disparity (also known as the gender gap) raised alarm bells among education researchers. If it is assumed that all members of society should have the opportunity to empower themselves economically and socially, regardless of their gender or ethnicity, girls should be allowed to tread a path, without obstacles or barriers, in the STEM field, particularly in the area of physics (Hazari et al. 2017).

According to Allen (2018), this gender gap is particularly persistent in physics (and computing), due to a complexity marked by historical, socio-cultural and psychological factors. The classroom reality often fails to resonate with girls, leading to a lack of identification with the subject (Wilson and Low 2016). This disconnect is frequently attributed to a prevailing culture of masculinity within the field, as noted by several researchers (Doucette and Singh 2024; Götschel 2014). A significant obstacle to girls’ engagement and success in this subject area is the pedagogical approach employed by teachers. The teaching methods and practices utilized play a crucial role in determining the extent to which girls feel connected.

Doucette and Singh (2024) emphasize that equity in physics education, along with the integral role of teachers in its various dimensions, are crucial for ensuring women’s participation in STEM fields. They argue that boys and girls often begin with different backgrounds and experiences, making it necessary to implement tailored interventions that address structural disadvantages and promote equal opportunities. This approach recognizes that achieving equity requires more than equal treatment; it demands targeted strategies to overcome existing barriers and provide genuine opportunities for all students in physics education. A girl-friendly strategy in STEM can be defined as a set of actions, practices, and policies intentionally designed to create inclusive, welcoming, and motivating environments for girls and women, reducing barriers to access, retention, and success in these areas that have historically been male-dominated. These interventions are summarized as curricular interventions that align with girls’ interests, a welcoming classroom environment that fosters self-efficacy, appropriate role models, and student-centered teaching (Baker 2013).

Differences between girls and boys manifest themselves from an early age, such as differences in schooling or parental incentives for certain interests and different hobbies (Miner et al. 2018). In the context of physics teaching and learning, Holmes et al. (2022) define (gender) equity as “everyone has access to the learning environment and everyone’s voice being heard” (p. 18). This definition goes beyond achieving outcomes but is also linked to classroom culture. Hazari et al. (2017) point out that the recognition given by teachers is an important aspect in developing a sense of belonging for girls, which later leads them to choose a career in STEM. Often, teachers do not provide girls with the necessary encouragement to pursue physics and only emphasize the difficulties they may experience in the subject (Cwik and Singh 2022; Zohar and Bronshtein 2005). Several authors (Gilmartin et al. 2007; Hazari and Potvin 2005) state that the teachers’ gender is less important than the relationship established with the pupils. This relationship between teachers and pupils’ gender is revealed in various aspects of the classroom environment. P. Murphy and Whitelegg (2006) highlight the imbalanced attention that teachers pay to boys, to the detriment of girls, because they are more participative in the classroom, monopolizing the classroom (A. Fernandes et al. 2024). Girls become used to not being the main protagonists and seeing that space reserved for boys (A. Fernandes et al. 2024; M. Oliveira 2018). Due (2014) further reveals that boys participate in a more competitive manner than girls, who tend to avoid conflicts. Boys end up receiving more feedback, both positive and negative. On the other hand, since the relationship with teachers is more relevant for girls than for boys, this aspect also becomes a disadvantage for girls. Additionally, teachers hold higher expectations for boys, which becomes an additional constraint for girls (P. Murphy and Whitelegg 2006).

In the context of physics education, girl-friendly strategies involve promoting gender equity and ensuring that both boys and girls have the same opportunities to learn and develop an interest in the subject. These strategies are interconnected and play a decisive role in the classroom (Haussler and Hoffmann 2002).

Girls’ tendency to use everyday language for a longer period compared to boys, who more rapidly adopt the technical terminology of physics, often results in unintended penalties from their teachers. This linguistic disparity, characterized by girls’ more frequent use of analogies and anthropomorphisms, can inadvertently impact their academic assessment and engagement in the subject. This penalty has a dual impact: it not only affects girls’ immediate performance but also leads teachers to inadvertently reserve more challenging tasks for boys. This practice reinforces a cycle of unequal expectations and opportunities in physics education (M. Oliveira 2018; Stadler et al. 2000, 2001).

Dreves and Jovanovic (1998) argue that male dominance in the classroom influences girls’ perception of their scientific abilities, particularly as they progress through their education, reinforcing the message that it is necessary to strengthen girls’ self-confidence before they enter science classes. Establishing an environment where girls can freely discuss problem-solving in groups fosters a less competitive learning environment. This approach enables them to validate their ideas and, consequently, improve their performance in the subject (Alexopoulou and Driver 1997; Eickerman and Rifkin 2020; Harskamp et al. 2008).

The results of physics assessments on a global scale and across all age groups have consistently shown lower performance for girls, a discrepancy that becomes more pronounced as students progress in their education (alongside declining interest in the subject), particularly in secondary and higher education (Adegoke 2012; Docktor et al. 2008; Haussler and Hoffmann 2002; McCullough 2004). Equity should also be reflected in assessment, providing girls with equal opportunities to achieve the same outcomes as boys. In other words, equitable evaluation may involve differentiated tools, alternative measurement methods, and diverse contexts in which items and problems are framed (Hazel et al. 1997). Problem contexts related to the human body and greater attention from teachers to multiple-choice items, which girls may perceive as a source of greater ambiguity, should also be considered. This perception, combined with lower self-confidence, often leads to poorer test results for girls. Meanwhile, boys, using a more effective strategy of eliminating incorrect options, tend to achieve better outcomes (Wilson and Low 2016).

A final consideration for teachers is the curriculum design, which is intrinsically linked to the content and presentation of textbooks. This aspect plays a significant role in shaping students’ perceptions and engagement with the subject matter. Good et al. (2010) note that the stereotypes present in textbooks across various scientific disciplines ultimately influence girls’ academic performance. The gender bias inherent in these materials results in boys and girls developing different attitudes and levels of participation in science, as textbook imagery also reflects a hidden curriculum (Lawlor and Niiler 2020). In a study conducted by (Cardim et al. 2024), the researchers concluded that female scientists were almost absent from 7th grade physics and chemistry textbooks. This is undoubtedly an important aspect that warrants reflection by teachers, researchers in the field, publishers, and other education stakeholders. In addition, the literature highlights the STEM approach as one of the girl-friendly strategies to achieve gender equity in physics education. Discovery-based teaching and learning, emphasizing the historical and socio-scientific context of the topics covered, as well as the use of real-life contexts, are important strategies for teachers to consider in physics education (Dare 2015). Studies have shown that the impact of different inquiry-based approaches can differ significantly between male and female students (S. Murphy et al. 2019). In a study conducted in Portugal (Ribeirinha et al. 2024), the implementation of an inquiry-based STEM approach was found to be particularly effective in enhancing STEM career interests among 12th grade female students. At this stage, it is worth referencing Dare (2015), who observes that girl-friendly practices are not only beneficial to girls’ learning but also have no negative impact on boys.

Moreover, the literature reveals that boys and girls have different interests. These differences in interests and learning styles demand a differentiated approach to the curriculum, integrating topics and strategies that address the specific needs of each gender, thereby promoting more balanced and inclusive learning. Boys tend to show greater interest in technology, while girls are more drawn to aspects related to human well-being and health (Hoffmann 2002). Although most studies on inequality in science, particularly in STEM, focus on students in middle school, high school, and the early years of higher education, research conducted with preschool children shows that the interests developed by girls at these ages may influence their future interest in science (Hamel 2021). In this regard, I. Fernandes and Cardim (2018) reveal in their study conducted in Portugal that prospective primary school and preschool teachers demonstrate significant gaps in their understanding of gender equality in the school context and maintain an androcentric view of science. This perspective could impact their female student’s choices regarding a scientific career.

Zohar and Bronshtein (2005) indicate that teachers often express indifference and a lack of knowledge about the reasons for the underrepresentation of girls in high school physics classes. Many educators remain unaware of the multifaceted factors deterring girls from pursuing physics and lack knowledge of effective strategies to encourage female participation and foster an equitable classroom environment. These teachers often maintain stereotypical views and fail to recognize their role in addressing the low representation of girls in physics. This lack of awareness and accountability perpetuates existing gender disparities. Stephenson et al. (2022) reinforce the idea that teachers’ awareness of their own biases and the use of inclusive pedagogical approaches are essential to promote girls’ interest and participation in STEM. In a study conducted in Spain by (Sáinz et al. 2012), teachers (of both genders) acknowledge that men continue to dominate fields such as information technology (IT). However, female teachers are more attuned to the social cost of this situation, while male teachers remain indifferent to gender issues. Additionally, most teachers do not encourage high school girls to pursue studies in this field and often justify the lack of women in IT by citing differences in abilities and biological differences. Another noteworthy aspect is that teachers attribute different causes for their students’ academic success based on gender: while effort and perseverance are attributed to girls, high intellectual abilities are credited to boys (Buckley et al. 2022). A. Fernandes et al. (2024) mention that girls themselves also attribute these characteristics to themselves. Many teachers believe that certain academic fields related to technology are more appropriate for boys, where they have greater opportunities for success than in traditionally female-dominated areas, such as the humanities. Teachers, however, seem unaware of their influence on students’ educational and professional choices (Sáinz et al. 2012).

Addressing gender issues can pave the way for women to acquire the skills necessary for developing a career in STEM fields (Uamusse et al. 2020). However, based on the points raised above, it is evident that teachers’ knowledge and beliefs about equitable physics education are inadequate. Zohar and Bronshtein (2005) argue that teachers’ limited understanding of the gender gap and the lack of opportunities to discuss this issue underscore the need for this topic to be seriously addressed in teacher training. Idin et al. (2017) emphasize the necessity of enhancing teacher training regarding gender-equitable practices in science education. Similarly, I. Fernandes and Cardim (2018) stress the importance of incorporating critical reflection on gender stereotypes into teacher training to implement truly equitable classroom practices.

In this regard, the STEP UP project (Sabouri et al. 2022) is worth highlighting. It prioritizes inclusive development through collaborative creation with teachers, students, and researchers to produce relevant and equitable classroom resources. By integrating ‘counternarratives’ within physics lessons and fostering supportive learning environments, STEP UP seeks to encourage physics identity development, especially among young women and students from marginalized groups. The project’s emphasis on feedback and evidence-based impact ensures that the materials are continuously improved to support these students, ultimately aiming to transform the physics culture into one that is more inclusive and equitable. Within this context, it is important to cite Potvin et al. (2023). This study investigated how counternarratives about physics—challenging stereotypes about who engages in physics and why—can influence high school students’ career intentions, especially among girls. The results indicate that discussing representation and showcasing diverse examples in physics can help address historical inequalities.

It is crucial to emphasize at this point that “sex” and “gender” are not synonymous: the term “sex” refers to a biological characteristic, encompassing male, female, or other identities, while “gender” reflects a socially and culturally constructed identity associated with masculinity, femininity, both, or neither. Gender is linked to a broad spectrum of physical and emotional attraction (Gonsalves 2010). Simplifying reality into a binary model may restrict students’ identities in the educational context, ignoring, for example, LGBTQ+ identities or ethnic issues (Traxler et al. 2016). While acknowledging the complexity of gender identity, the authors opted for a binary model in their study due to the limited published literature in Portugal on this topic. This approach, which overlaps sex and gender using generic language for readability, serves as a starting point for a productive discussion on gender-equitable practices in physics education. The authors recognize that this simplified model has limitations but believe it can initiate important conversations about inclusivity in STEM fields.

Given the factors outlined above, addressing these challenges requires a deeper examination of how these often-invisible teacher-related barriers contribute to the systemic exclusion of girls in physics. Therefore, given the almost nonexistent literature in Portugal regarding teachers’ perceptions of gender issues in physics teaching practices, this empirical and exploratory study was conducted to explore how Physics teachers are aware of the gender gap and how they use, or are willing to use, girl-friendly strategies in their classrooms. The research aims to answer the research questions: “What are physics teachers’ perspectives on the gender gap?” and “How do Portuguese teachers implement girl-friendly strategies?”

2. Materials and Methods

The sample for this study consists of 55 Portuguese physics and chemistry teachers from two educational levels: lower secondary education (middle school) and upper secondary education in Portugal. It should be noted that in Portugal, teachers are qualified to teach both these scientific subjects, which, from year 7 to year 11, are taught together in a single course. Given the researchers’ access to a limited sample, the snowball sampling technique (Parker et al. 2019) was employed, in which the initial participants (volunteers) were encouraged to disseminate the study. The researchers began data collection with a small number of teachers who met the inclusion criteria—being a Portuguese teacher in the disciplines of physics and chemistry These participants, in turn, invited other individuals meeting the same criteria. Data collection took place between July and September 2024.

The teachers voluntarily participated in the research and were informed about the terms of confidentiality and anonymity, with the data being processed by national data protection regulations. Participants were also informed about the purpose of the questionnaire: “This research aims to contribute to the enrichment of knowledge regarding the influence of gender on physics learning in the national context, specifically understanding the perspectives of physics and chemistry teachers, and promoting equitable and inclusive teaching practices, referred to as girl-friendly, at the secondary education level, which may ultimately reflect a society committed to equal opportunities for men and women”. Regarding gender distribution, 6 participants identified as male, 48 as female, and 1 preferred not to disclose their gender. To maintain consistency with a binary gender model, data from the latter participant were not considered in the analysis. It should be noted that according to official national statistics (DGEEC 2024) for the 2022/2023 academic year, in public education, approximately 76% of teachers are female and 24% are male. Even so, the disproportion is even more pronounced in the study sample compared to the overall population.

The data collection instrument comprises a questionnaire, of which the initial three items aimed at characterizing participants in terms of gender, years of service, and educational level, which constitute the independent variables of the study:

- Gender: A closed-ended item with three response options: 1—Female; 2—Male; 3—Prefer not to disclose. To maintain internal consistency with this research, and as previously mentioned, only data from participants who chose options 1 and 2 were considered.

- Years of Service: A closed-ended item allowing participants to choose from several time intervals: [0–5 years]; [6–10 years]; [11–20 years]; [21–30 years]; [>31 years].

- Educational Level: A closed-ended Item providing options to select among “Lower secondary education”; “Upper secondary education”; or both.

The questionnaire includes two multiple-choice items, each with five answer options. These questions are designed to elicit teachers’ perspectives on girls’ participation in physics classes compared to boys, as well as their observations on how this participation has evolved throughout their teaching careers.

- Do you consider that there are differences in the participation of girls compared to boys in physics classes?

- Based on your experience, have you noticed, over the years, an increase in girls’ participation and engagement in physics classes?

The remaining three open-ended items relate to dependent variables that can be described as: “Interest in the Topic”, “Implementation of Strategies”, and “Curriculum”. All were presented using a 5-point Likert scale.

- Item: “Promoting girls’ participation in physics is a topic of my interest”. The five options correspond to the following levels: level 1 represents the minimum level of interest, and level 5 represents the maximum level of interest. This item aims to assess teachers’ level of interest in promoting female participation in physics, emphasizing the importance of this issue to them.

- Item: “I consciously implement classroom strategies to encourage greater participation of girls in physics classes”. The five options correspond to “I never implement”; “I rarely implement”; “I implement infrequently”; “I implement frequently”; and “I always implement”. This item aims to measure how often teachers deliberately apply strategies to encourage girls’ participation in physics classes, thereby evaluating their level of commitment and preference for inclusive strategies.

- Item: “In your opinion, in physics, should textbooks and curriculum objectives better reflect girls’ interests to motivate them to learn physics?” The five options correspond to the following levels: level 1 represents a less favorable opinion, while level 5 represents a more favorable opinion. This item aims to understand the extent to which teachers perceive textbooks and physics essential learning (Direção Geral da Educação 2017) content as being tailored to include interests and perspectives that could better motivate female students. This opinion reflects teachers’ perception of the importance of a more inclusive curriculum.

The scope of the closed-ended Items, the items themselves, the type of variable, and the answer options are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Closed questions asked in the descriptive–correlational study, type of variable and respective response options.

The open-ended item aims, on the one hand, to compare the data obtained in the quantitative section and, on the other, to generate additional insights into the strategies teachers actually employ.

- What do you think could be changed in physics classes to make girls feel more drawn to careers in this field? (This item can remain open to allow more detailed responses).

The data obtained through the application of the questionnaire were analyzed using SPSS® software (version 29.0) (for closed-ended questions) and WebQDA® (Version 3.0) (for open-ended questions). Quantitative data from the closed-ended questions were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics, while qualitative data from the open-ended question were subjected to categorical content analysis (Bardin 2013). The results of the categorical content analysis were interpreted by triangulating them with the previous results.

In the descriptive–correlational study, in addition to the use of descriptive statistics—particularly for questions 4 and 5 (“participation of girls” and “evolution of girls’ participation”)—the Chi-Square test was applied to assess the existence of correlations between categorical variables (“gender” and “teaching level”) and ordinal variables (“interest”, “strategy implementation”, and “curriculum”), i.e., the independent and dependent variables. This test of independence is used to estimate the likelihood that factors other than chance explain the observed relationship (Onchiri 2013). It is used to compare distributions of a categorical variable across different groups or to determine whether the variable and the groups are independent (Kim 2017).

However, when the sample size for each category is less than five, another test, Fisher’s Exact Test, is required. This test is a modification of Pearson’s Chi-Square test and was considered in this study (Bolboacă et al. 2011; Maroco 2007; L. Oliveira 2017). Relationships between the independent categorical variables and dependent variables were studied under the null hypothesis H0, i.e., there is no relationship between the variables, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Chi-Square test and Fisher’s Exact test applied to the variables.

The correlation between the ordinal variables “years of service” and “interest”, “strategy implementation”, and “curriculum” was also explored. Correlation can be seen as a way to measure how similar or parallel two variables vary. Moreover, correlation is described as a measure of agreement, as it can quantify the degree of consistency between two rankings. Correlation differs from the Chi-Square test because the latter only provides a measure of association between two variables (Jakobsson and Westergren 2005).

The most commonly applied test is Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rho), a non-parametric measure of correlation. Unlike Pearson’s correlation coefficient, it does not require the assumption of a linear relationship between variables and can be used for ordinal variables (Pereira and Patrício 2022).

For the variables whose association was statistically significant with Fisher’s Exact test, non-parametric tests were applied (Pereira and Patrício 2022):

- Mann–Whitney U test is used to assess whether the distributions of two independent samples are significantly different.

- Kruskal–Wallis test the non-parametric version of ANOVA (Analysis of Variance). This test evaluates (for more than two groups) whether at least one group differs significantly from the others in terms of the variable of interest.

The use of non-parametric statistics is related, on the one hand, to the fact that the variables are not continuous, and on the other, to the robustness of non-parametric tests in small samples, as they do not depend on specific distributions (Maroco 2007).

3. Results

Of the 55 participants in the study, all responded to both the open-ended and closed-ended questions, with no missing cases. Hereafter, the data analysis will only include responses from 48 female and 6 male participants, totaling 54 participants.

3.1. Quantitative Analysis

The relative frequencies of each independent variable are presented in Table 3. Observing these frequencies, it can be determined that the vast majority of participants are female, have 20–30 years of service, and teach at the secondary education level.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of participants concerning the variables “gender”, “years of service”, and “teaching level”.

The results of the responses to the questions were graphically analyzed concerning the two descriptive variables, “girls’ participation” and “evolution of girls’ participation”, and the three dependent variables, “curriculum”, “implementation of girl-friendly strategies”, and “interest in the topic”.

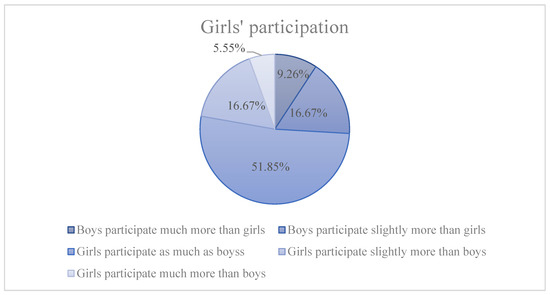

Regarding the girls’ participation variable, the most frequent response (51.85%) was “girls are as participatory as boys”. However, a small number of teachers believe that “girls participate much more than boys” (5.56%). The same percentage of teachers (16.7%) believe that “girls participate slightly more than boys” and that “boys participate slightly more than girls”, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Responses, in percentage, in the various categories of the variable “girls’ participation”.

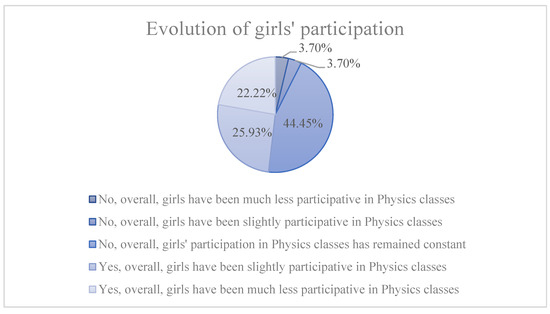

Regarding the variable “evolution of girls’ participation”, as shown in Figure 2, it is noteworthy that almost half of the teachers (44.44%) answered that “overall, girls’ participation in physics classes has remained constant”. Only 7.4% of the teachers consider that “girls are much less participative” or “less participative”. However, approximately 48% of the participants believe that girls’ participation has been more or much more than boys’ participation in physics classes.

Figure 2.

Responses, in percentage, in the various categories of the variable “evolution of girls’ participation”.

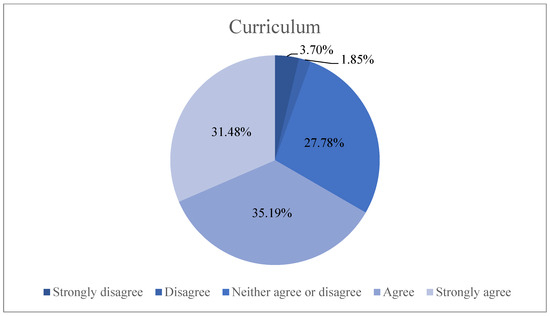

Regarding the variable “curriculum”, the majority of teachers believe that school textbooks and the physics essential learnings should reflect the interests of girls in order to make them feel more motivated, considering the percentage (66.7%) of categories 4 and 5 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Responses, in percentage, in the various categories of the variable “curriculum”.

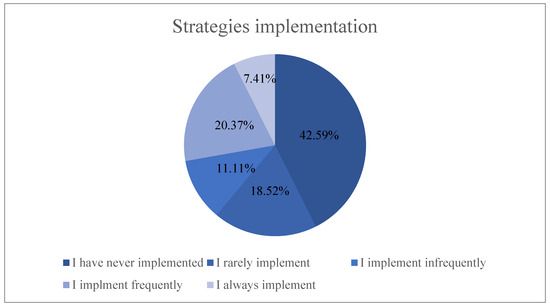

In terms of “implementation of girl-friendly strategies”, the highest percentage of responses was for the option “never” with 42.59%, followed by “rarely” with 18.52%, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Responses, in percentages, across the various categories of the variable “implementation of girl-friendly strategies”.

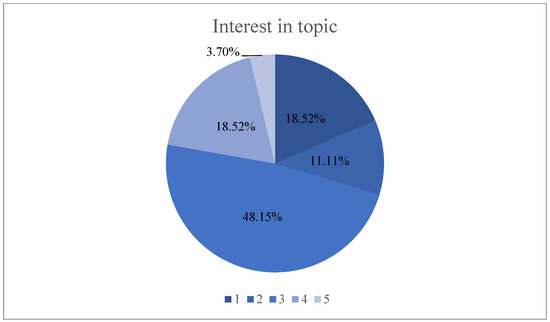

The “interest in the topic” appears to be significant among the teachers, as nearly half of them (48.15%) express “some” interest. The percentage of teachers who have “some”, “considerable”, or “great” interest totals 70.37%, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Frequency of responses in the various categories of the variable “interest in the topic”.

The results from the Pearson Chi-Square and Fisher’s Exact test indicate that the associations between the categorical variables “gender” and “educational cycle” and “girls’ participation”, “evolution of participation”, “curriculum”, and “implementation of girl-friendly strategies” are not statistically significant, as shown in Table 4. The association between “gender” and “educational cycle” and “interest in the topic” appears to be statistically significant, although these results must be interpreted with caution, given the limited size of the sample.

Table 4.

Summary of the results of the Chi-Square tests and Fisher’s Exact test.

Non-parametric tests were performed after identifying an association between variables using Fisher’s test, which, however, showed no statistically significant difference between the various categories for the independent variable “topic of interest” (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Summary of the results of the non-parametric tests.

The association between ordinal variables, namely the independent variables such as “years of service” and “strategy implementation”, “curriculum” and “interest in the topic”, was investigated through a correlation test and the Spearman correlation coefficient, which also indicates that none of the variables are significant, as none of the values are close to 1 or −1, and are in fact closer to 0, as observed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Summary of Chi-square Test and Fisher’s Exact Test Results.

3.2. Qualitative Analysis

Regarding the analysis of responses to open-ended questions, seven categories of analysis were created, and defined a posteriori after an exploratory analysis of participants’ responses. These categories are as follows: “competitions”, “role model”, “classroom strategies”, “deconstructing stereotypes”, “no room for new strategies”, “strategies in the classroom”, “strategies outside the classroom”, and “don’t know”, with their operational descriptions provided in Table 7. Table 8 shows the number of references for each category. It is important to note that each participant has more than one intervention, meaning they may be categorized into more than one analysis category.

Table 7.

Summary of non-parametric tests.

Table 8.

Frequency and percentage of references by category.

It is also possible to obtain the data through Table 9, that is, by cross-referencing the teacher’s gender data with the various analysis categories. It is observed that the options, particularly for the most represented group, female teachers, are polarized between the category “no room for new strategies” and “classroom strategies” (see Table 9).

Table 9.

Frequency analysis of categories in relation to teacher gender.

From these results, it is possible to deepen the discussion on the use of girl-friendly strategies in physics education, considering the teacher’s perspective and its educational implications. The analysis of the teachers’ responses reveals an ambivalent stance regarding the adoption of girl-friendly strategies. Although a significant proportion of respondents—particularly female teachers—expressed openness to more inclusive practices, such as the promotion of female role models and the deconstruction of gender stereotypes, the most frequently mentioned category was “no new strategies”. This may reflect a certain resistance to change, a lack of training, or a perceived ineffectiveness of such approaches.

4. Discussion

Considering the exploratory nature of this mixed-methods study—which focused on investigating physics and chemistry teachers’ perceptions regarding the gender gap and the implementation of girl-friendly practices—it can be asserted that the research contributed to a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the topic. The qualitative findings were particularly significant, as they provided insight into teachers’ perceptions of the barriers faced by female students in physics and how these educators either implement or intend to implement strategies aimed at promoting more inclusive and equitable classroom practices.

Regarding the quantitative analysis globally, it can be stated that most teachers perceive that girls participate as much (or more) as boys and that their level of participation has remained constant over time or has even increased. Teachers believe that boys and girls participate equally and that the participation of girls has remained the same or increased. That is to say, the teachers as a group do not perceive any gender disparity in classroom participation.

The majority of teachers believe that the physics curriculum and textbooks should be more representative of girls’ interests. As mentioned above, one such example could be the inclusion of more female scientists in the illustrations of these textbooks. About 27.2% of teachers stated that they have never (or rarely) implemented girl-friendly strategies, but the data reveal that most have some, considerable, or great interest in the topic. In this regard, it should be recalled that several studies have revealed a widespread underrepresentation of women in school textbooks across the globe (Good et al. 2010) and since teachers rely on the examples provided in it to structure their lessons, it is natural that the percentage of teachers employing these strategies remains low.

At this point, it is necessary to clarify that the teachers were informed about the study’s objective, but the expression “girl-friendly strategies” remained undefined. Thus, there may be some lack of understanding among teachers regarding the actual scope and concept of these strategies at the time of completing the questionnaire, which may explain why a significant percentage stated that they do not implement them. There is no association between the independent variables “gender” and “education cycle” and the dependent variables “curriculum”, “implementation of girl-friendly strategies”, and “interest in the topic”. However, an association was found in Fisher’s test between the independent variables “education cycle” and “gender” and “interest in the topic”, which was not confirmed by the non-parametric tests performed. This discrepancy may be due to the difference in sensitivity and what each test evaluates: Fisher’s test indicates a global association, but this does not necessarily mean there is a significant difference in distributions between two specific groups according to the Mann–Whitney U test and the Kruskal–Wallis test (Maroco 2007). These findings align with the literature, as male and female teachers do not seem to condition girls’ performance differently (Régner 2014). Data should be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size, but they are, to some extent, consistent with the existing literature. Although female teachers may serve as role models for the girls, they represent a highly heterogeneous group, and findings from empirical studies yield multifaceted results (Sansone 2017). The limited participation of male teachers may reflect a certain detachment from gender equity issues, which represents an additional challenge to the implementation of more inclusive and transformative practices within the discipline.

There is also no correlation between the independent variable “years of service” and the dependent variables “curriculum”, “implementation of girl-friendly strategies”, and “interest in the topic”, which are all ordinal, meaning that variations in one variable do not follow a clear trend in variations in the other—the data do not show a consistent pattern of increase, decrease, or any type of association between them. However, it should be noted that lower teaching experience may not be directly associated with the teacher’s age, as current legislation allows for the presence of teachers with subject-specific qualifications (i.e., those with higher scientific training in the subject they teach but not necessarily with a degree in education and teaching). In 2024, these teachers accounted for approximately 15% of all educators, according to press reports (ECO 2024). Additionally, Hammrich et al. (2000) highlight that teachers’ years of service can impact their teaching conceptions and practices, particularly regarding gender equity. Teachers with more years of experience often have established conceptions about science teaching, which may hinder the adoption of new practices, such as girl-friendly strategies. However, their study also suggests that participation in continuous training programs helped some teachers adjust their practices, regardless of their prior experience.

The data from the open-ended question analysis show that teachers are still not highly sensitive to the issue of promoting gender equity in physics education, similar to what the literature reveals regarding teachers’ perceptions of STEM subjects (Andreula 2023). A similar number of references were registered between the categories “no need for new strategies” and “classroom strategies”. Several participants stated that “interest in physics”, “competence”, “personality”, “interests”, “ways of thinking”, or “enthusiasm” are “not gendered” or not related to “sex” (noting here the overlap of the concepts of gender and sex) and that all students should be motivated. One participant also stated that “nothing needs to be changed, only to clarify career opportunities for students”. Another participant mentioned that she does not know how to respond because girls “still say they do not understand why a female teacher likes physics”.

Some responses reflected passive approaches to addressing gender disparities in science education, without emphasizing an active role for teachers. These included suggestions such as exposing girls to “different interests, products, and toys” and promoting “attractive careers in the field”. As Brickhouse et al. (2000) noted, such strategies alone may be insufficient to address the complex factors influencing girls’ participation in science.

The references to classroom strategies seem to contradict the high percentage of teachers who, in closed-ended questions, claimed not to use girl-friendly strategies. The use of an open-ended question may have led teachers to research its meaning to answer, confronting them with practices they may already implement. Several teachers mentioned aligning content with the “female universe”, “female world”, “female reality”, or “girls’ daily lives”. Making the “subject less theoretical and more demonstrative” is a reference related to curriculum issues, as noted by Abraham and Barker (2023). The formation of “mixed-gender groups” mentioned by one participant may not be an effective strategy. According to various authors (e.g., Alexopoulou and Driver 1997; Harskamp et al. 2008), in mixed-gender groups, boys tend to dominate discussions while girls validate their opinions.

A participant referred to using physics examples and applications related to health, “where girls have more representation”, and several teachers mentioned focusing on practical or experimental activities to reduce the theoretical nature of the subject (Dare and Roehrig 2020; Doucette and Singh 2024). Others mentioned “STS (Science, Technology, and Society) activities” and those involving the “historical context and evolution of science”, aligning with previously published studies (e.g., Hughes 2000). Integrating examples of female scientists who contributed to “physics advancements” or “bringing real testimonies to the classroom” using the “role model” approach (Hazari et al. 2017) was mentioned by some participants, with one providing a very specific strategy.

The results suggest that most teachers perceive female participation in physics as satisfactory and do not recognize a gender gap. On the other hand, many teachers still lack a clear understanding or consistent practice of gender equity strategies, believing that external factors, rather than their classroom actions, are responsible for girls’ exclusion. The findings also highlight the necessity of teacher training, which should be taken into account in future research, as the literature indicates promising results in this regard (Stephenson et al. 2022).

5. Conclusions

Overall, teachers perceive that boys and girls participate at similar levels, and that girls’ participation has either remained stable or increased. In other words, they do not collectively perceive a gender gap in classroom participation. However, the findings highlight a need for clearer definitions and understanding of girl-friendly strategies in physics among teachers. Although this exploratory study did not find any significant associations between variables such as teacher gender, years of service, level of education, and the interest in or implementation of girl-friendly strategies, it is important to note certain limitations, such as the reduced number of male teachers and the small overall sample size. Future studies should consider methodological approaches that mitigate this limitation in data collection and more robustly capture teachers’ perceptions. Despite this constraint, the qualitative analysis provided several meaningful insights, such as the fact that some teachers believe that interest and competence in physics are not gender-related, indicating a need for awareness of unconscious biases. Various classroom strategies were mentioned, including aligning content with girls’ interests, focusing on practical activities and incorporating female role models in science. Future research should focus on analyzing the outcomes of teacher training programs aimed at promoting gender equity, in order to assess their effectiveness and the extent to which they translate into concrete changes in physics classroom practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.F. and J.L.A.; methodology, A.M.F. and J.L.A.; software A.M.F.; validation, J.L.A.; formal analysis, A.M.F.; investigation, A.M.F.; resources, A.M.F.; data curation, A.M.F.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.F.; writing—review and editing, A.M.F. and J.L.A.; visualization, A.M.F.; supervision, J.L.A., F.S. and S.G.; project administration, J.L.A.; funding acquisition, J.L.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is financially supported by National Funds through FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P. under the projects UIDB/00194/2020 (CIDTFF) and UIDP/00194/2020 (CIDTFF).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Directorate-General for Education (protocol code 1295700001 and date of approval 13 November 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The authors will provide relevant data upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abraham, Jessy, and Katrina Barker. 2023. Students’ Perceptions of a “Feminised” Physics Curriculum. Research in Science Education 53: 1163–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegoke, Benson Adesina. 2012. Impact of Interactive Engagement on Reducing the Gender Gap in Quantum Physics Learning Outcomes among Senior Secondary School Students. Physics Education 47: 462–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulou, Evinella, and Rosalind Driver. 1997. Gender Differences in Small Group Discussion in Physics. International Journal of Science Education 19: 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Michael. 2018. Gender Gap in Physics among Highest in Science. Physics World 31: 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreula, Danielle. 2023. Teacher Perceptions of the Gender Gap in STEM Education: A Basic Qualitative Study. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/teacher-perceptions-gender-gap-stem-education/docview/2892620603/se-2 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Baker, Dale. 2013. What works: Using curriculum and pedagogy to increase girls’ interest and participation in science. Theory into Practice 52: 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin, Lawrence. 2013. Análise de Conteúdo, 4th ed. Lisboa: Edições. [Google Scholar]

- Bolboacă, Sorana D., Lorentz Jäntschi, Adriana F. Sestraş, Radu E. Sestraş, and Doru C. Pamfil. 2011. Pearson-Fisher Chi-Square Statistic Revisited. Information 2: 528–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickhouse, Nancy W., Patricia Lowery, and Katherine Schultz. 2000. What Kind of a Girl Does Science? The Construction of School Science Identities. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 37: 441–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, Chris, Lynn Farrell, and Ian Tyndall. 2022. Brief Stories of Successful Female Role Models in Science Help Counter Gender Stereotypes Regarding Intellectual Ability among Young Girls: A Pilot Study. Early Education and Development 33: 555–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardim, Sofia, Ana Fernandes, and Sandra Soares. 2024. Referência A Mulheres Cientistas—Uma Análise Aos Manuais Escolares Da Disciplina De Físico-Química Do 7o Ano Do Ensino Básico. APEduC (Associação Portuguesa de Educação em Ciências) Revista-Investigação e Práticas em Educação em Ciências, Matemática e Tecnologia 5: 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Cwik, Sonja, and Chandralekha Singh. 2022. Not Feeling Recognized as a Physics Person by Instructors and Teaching Assistants Is Correlated with Female Students’ Lower Grades. Physical Review Physics Education Research 18: 010138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dare, Emily A., and Gillian H. Roehrig. 2020. Beyond Einstein and Explosions: Understanding 6th Grade Girls’ and Boys’ Perceptions of Physics, School Science, And Stem Careers. Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering 26: 541–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dare, Emily Anna. 2015. Understanding Middle School Students’ Perceptions of Physics Using Girl- Friendly and Integrated STEM Strategies: A Gender Study. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Direção Geral da Educação. 2017. Currículo do Ensino Básico e do Ensino Secundário para a Construção de Aprendizagens Essenciais Baseadas no Perfil dos Alunos. Available online: https://www.dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/Curriculo/Projeto_Autonomia_e_Flexibilidade/ae_documento_enquadrador.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Direção-Geral de Estatísticas da Educação e Ciência (DGEEC). 2024. Estatísticas da Educação 2022/2023. Available online: https://www.dgeec.medu.pt/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Docktor, Jennifer, Kenneth Heller, Charles Henderson, Mel Sabella, and Leon Hsu. 2008. Gender Differences in Both Force Concept Inventory and Introductory Physics Performance. Paper presented at Em AIP Conference Proceedings, Edmonton, AB, Canada, July 23–24; Melville: AIP. [Google Scholar]

- Doucette, Danny, and Chandralekha Singh. 2024. Gender Equity in Physics Labs. Physical Review Physics Education Research 20: 010102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreves, Candice, and Jasna Jovanovic. 1998. Male Dominance in the Classroom: Does it Explain the Gender Difference in Young Adolescents’ Science Ability Perceptions? Applied Developmental Science 2: 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Due, Karin. 2014. Who Is the Competent Physics Student? A Study of Students’ Positions and Social Interaction in Small-Group Discussions. Cultural Studies of Science Education 9: 441–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECO. 2024. 15% dos Professores Contratados nas Escolas têm Habilitação Própria. ECO (Blog). 9 de janeiro de 2024. Available online: https://eco.sapo.pt/2024/01/09/15-dos-professores-contratados-nas-escolas-tem-habilitacao-propria/#:~:text=Atualmente,%2015%%20dos%20professores%20contratados%20para (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Eickerman, Olivia, and Moses Rifkin. 2020. The Elephant in the (Physics Class)Room: Discussing Gender Inequality in Our Class. The Physics Teacher 58: 301–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, Ana, José Luís Araújo, and Fátima Simões. 2024. Physics Classroom: Where Is the Gender Gap? Paper presented at 16th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, Palma, Spain, July 1–3. Em Edulearn24 Proceedings. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, Isabel, and Sofia Cardim. 2018. Percepção de futuros docentes portugueses acerca da sub-representação feminina nas áreas e carreiras científico-tecnológicas. Educação e Pesquisa 44: e183907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmartin, Shannon, Nida Denson, Erika Li, Alyssa Bryant, and Pamela Aschbacher. 2007. Gender Ratios in High School Science Departments: The Effect of Percent Female Faculty on Multiple Dimensions of Students’ Science Identities. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 44: 980–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonsalves, Allison J. 2010. Discourses and Gender in Doctoral Physics: A Thesis submitted to McGill University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Ph.D. thesis, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada. Available online: https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/theses/v405s9735 (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Good, Jessica J., Julie A. Woodzicka, and Lylan C. Wingfield. 2010. The Effects of Gender Stereotypic and Counter-Stereotypic Textbook Images on Science Performance. The Journal of Social Psychology 150: 132–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götschel, Helene. 2014. No Space for Girliness in Physics: Understanding and Overcoming the Masculinity of Physics. Cultural Studies of Science Education 9: 531–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, Erin E. 2021. Science Starts Early: A Literature Review Examining the Influence of Early Childhood Teachers’ Perceptions of Gender on Teaching Practices. Journal of Childhood, Education & Society 2: 267–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammrich, Penny L., Greer M. Richardson, and Beverly Livingston. 2000. Sisters in Science: Teachers’ Reflective Dialogue on Confronting the Gender Gap. Journal of Elementary Science Education 12: 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harskamp, Egbert, Ning Ding, and Cor Suhre. 2008. Group Composition and Its Effect on Female and Male Problem-Solving in Science Education. Educational Research 50: 307–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haussler, Peter, and Lore Hoffmann. 2002. An Intervention Study to Enhance Girls’ Interest, Self-Concept, and Achievement in Physics Classes. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 39: 870–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazari, Zahra, and Geoff Potvin. 2005. Views on Female Under-Representation in Physics: Retraining Women or Reinventing Physics? The Electronic Journal for Research in Science & Mathematics 10. [Google Scholar]

- Hazari, Zahra, Eric Brewe, Renee Michelle Goertzen, and Theodore Hodapp. 2017. The Importance of High School Physics Teachers for Female Students’ Physics Identity and Persistence. The Physics Teacher 55: 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazel, Elizabeth, Peter Logan, and Patricia Gallagher. 1997. Equitable Assessment of Students in Physics: Importance of Gender and Language Background. International Journal of Science Education 19: 381–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, Lore. 2002. Promoting Girls’ Interest and Achievement in Physics Classes for Beginners. Learning and Instruction 12: 447–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, Natasha, Grace Heath, Katelynn Hubenig, Sophia Jeon, Z. Yasemin Kalender, Emily Stump, and Eleanor C. Sayre. 2022. Evaluating the Role of Student Preference in Physics Lab Group Equity. Physical Review Physics Education Research 18: 010106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Gwyneth. 2000. Marginalization of Socioscientific Material in Science-Technology-Society Science Curricula: Some Implications for Gender Inclusivity and Curriculum Reform. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 37: 426–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idin, Sahin, Ismail Donmez, and Ministry of National Education, Turkey. 2017. The Views of Turkish Science Teachers About Gender Equity within Science Education. Science Education International 28: 119–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILOSTAT. 2023. ILOSTAT—International Labour Organization (Blog). Available online: https://ilostat.ilo.org/blog/how-many-women-work-in-stem/ (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Jakobsson, Ulf, and Albert Westergren. 2005. Statistical Methods for Assessing Agreement for Ordinal Data. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 19: 427–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Hae-Young. 2017. Statistical Notes for Clinical Researchers: Chi-Squared Test and Fisher’s Exact Test. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics 42: 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, Timothy M., and Timothy Niiler. 2020. Physics Textbooks from 1960–2016: A History of Gender and Racial Bias. The Physics Teacher 58: 320–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroco, João. 2007. Análise Estatística com Utilização do SPSS, 3rd ed. Lisbon: Edições Sílabo. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough, Laura. 2004. Gender, Context, and Physics Assessment. Journal of International Women’s Studies 5: 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Miner, Kathi N., Jessica M. Walker, Mindy E. Bergman, Vanessa A. Jean, Adrienne Carter-Sowell, Samantha C. January, and Christine Kaunas. 2018. From “Her” Problem to “Our” Problem: Using an Individual Lens Versus a Social-Structural Lens to Understand Gender Inequity in STEM. Industrial and Organizational Psychology 11: 267–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, Patricia, and Elizabeth Whitelegg. 2006. Girls in the Physics Classroom: A Review of the Research on the Participation of Girls in Physics Institute of Physics. London: Institute of Physics. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, Steve, Amy MacDonald, Lena Danaia, and Cen Wang. 2019. An analysis of Australian STEM education strategies. Policy Futures in Education 17: 122–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nações Unidas. 2023. Objetivos de Desenvolvimento Sustentável. Nações Unidas (Blog). Available online: https://unric.org/pt/objetivos-de-desenvolvimento-sustentavel/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES). 2023. Diversity and STEM: Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities. Alexandria: National Science Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, Luís. 2017. A Perturbação de Hiperatividade/Défice de Atenção (PHDA): Do Conhecimento dos Professores às Práticas Educativas no 1.o Ciclo do Ensino Básico. Tese de Doutoramento em Estudos da Criança Especialidade em Educação Especial, Universidade do Minho. Available online: https://repositorium.sdum.uminho.pt/bitstream/1822/48671/1/Luis%20Carlos%20Martins%20de%20Oliveira.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Oliveira, Margarida. 2018. Perceções Sobre a Influência do Género na Aprendizagem das Ciências e no Prosseguimento de Carreiras Científicas: Um Estudo de Métodos Mistos. Ph.D. thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Onchiri, Sureiman. 2013. Conceptual Model on Application of Chi-Square Test in Education and Social Sciences. Educational Research and Reviews 8: 1231–41. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, Sam, Charlie Scott, and A Guedes. 2019. Snowball Sampling. SAGE Research Methods Foundation. University of Gloucestershire. Available online: http://methods.sagepub.com/foundations/snowball-sampling (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Pereira, Alexandre, and Teresa Patrício. 2022. SPSS—Guia Prático de Utilização, 8th ed. Lisbon: Edições Sílabo. [Google Scholar]

- Potvin, Geoff, Zahra Hazari, Raina Khatri, Hang-Chiao Cheng, Tiffany B. Head, Rebecca M. Lock, Anne F. Kornahrens, Kathryne Sparks Woodle, Rebecca E. Vieyra, Beth A. Cunningham, and et al. 2023. Examining the Effect of Counternarratives about Physics on Women’s Physics Career Intentions. Physical Review Physics Education Research 19: 010126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Régner, Isabelle, ed. 2014. Menace Du Stéréotype Chez Les Enfants: Passé et Présent = Stereotype Threat in Children. Revue Internationale de Psychologie Sociale 27: 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeirinha, Teresa, Mónica Baptista, and Marisa Correia. 2024. Investigating the Impact of STEM Inquiry-Based Learning Activities on Secondary School Student’s STEM Career Interests: A Gender-Based Analysis Using the Social Cognitive Career Framework. Education Sciences 14: 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabouri, Pooneh, Zahara Hazari, Raina Khatri, and Bree Dreyfuss. 2022. Considerations for inclusive and equitable design: The case of STEP UP counternarratives in HS physics. The Physics Teacher 60: 740–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, Dario. 2017. Why does teacher gender matter? Economics of Education Review 61: 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáinz, Milagros, Rachel Pálmen, and Sara García-Cuesta. 2012. Parental and Secondary School Teachers’ Perceptions of ICT Professionals, Gender Differences and Their Role in the Choice of Studies. Sex Roles 66: 235–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, Helga, Gertraud Benke, and Reinders Duit. 2001. How Do Boys and Girls Use Language in Physics Classes? In Research in Science Education—Past, Present, and Future. Edited by Helga Behrendt, Helmut Dahncke, Reinders Duit, Wolfgang Gräber, Michael Komorek, Angela Kross and Priit Reiska. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 283–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, Helga, Reinders Duit, and Gertraud Benke. 2000. Do Boys and Girls Understand Physics Differently? Physics Education 35: 417–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, Tanya, Marilyn Fleer, Glykeria Fragkiadaki, and Prabhat Rai. 2022. You can be whatever you want to be!”: Transforming teacher practices to support girls’ STEM engagement. Early Childhood Education Journal 50: 1317–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traxler, Adrienne L., Ximena C. Cid, Jennifer Blue, and Ramón Barthelemy. 2016. Enriching Gender in Physics Education Research: A Binary Past and a Complex Future. Physical Review Physics Education Research 12: 020114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uamusse, Amália Alexandre, Eugenia Flora Rosa Cossa, and Tatiana Kouleshova. 2020. A mulher em cursos de ciências, tecnologia, engenharia e matemática no ensino superior moçambicano. Revista Estudos Feministas 28: e68325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidor, Carolina de Barros, Anna Danielsson, Flavia Rezende, and Fernanda Ostermann. 2020. What Are the Problem Representations and Assumptions About Gender Underlying Research on Gender in Physics and Physics Education? A Systematic Literature Review. Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa Em Educação Em Ciências 20: 1133–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Kate, and David Low. 2016. Reducing the Gender Gap in First-Year Physics Performance. Paper presented at Em Proceedings of the Australian Conference on Science and Mathematics Education, Brisbane, Australia, September 28–30; Brisbane: The University of Queensland, pp. 246–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zohar, Anat, and Boaz Bronshtein. 2005. Physics Teachers’ Knowledge and Beliefs Regarding Girls’ Low Participation Rates in Advanced Physics Classes. International Journal of Science Education 27: 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).