Abstract

Schools play a central role in the prevention and control of school bullying, and there are both theoretical and practical grounds for legally establishing their obligations in this regard. This study employs a mixed-methods approach, primarily qualitative research supplemented by quantitative analysis, to conduct textual analysis and coding of 155 civil judgments on school bullying litigation in China. It aims to explore the main scenarios where schools are held liable for failing to fulfill their prevention and intervention obligations, and to examine the impact of school accountability on bullied students. Through textual analysis and t-tests, this study found that schools are primarily held liable for inadequate prevention, failure to detect or allowing bullying behavior, and failure to provide timely assistance to victims. Meanwhile, neglecting antibullying obligations exacerbates the mental harm suffered by victims. However, as public educational institutions, schools should not bear an excessive legislative burden, as this could increase their workload and lead to resistance in practice. Therefore, it is crucial to strike a balance and refine school responsibilities. Establishing clear legal obligations for schools can help clarify the standards for school liability in judicial decisions. Accordingly, improving fundamental antibullying obligations, granting schools a certain degree of disciplinary discretion, and enhancing guidance in high-risk situations can ensure the fulfillment of essential responsibilities while empowering schools to effectively combat bullying.

1. Research Background: The Issue at Hand

School bullying, as a global issue, has garnered increasing attention from both the Chinese government and academic circles because of its severity and frequent occurrence. UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization) and WABF (World Anti-Bullying Forum) acknowledge that current progress in reducing school bullying remains slow (CDC 2024). The concurrent survey also reveals that 53.5% of students still report experiencing bullying in China (China National Radio Network 2024). Numerous studies have demonstrated that bullying severely undermines victims’ health and academic achievement (Sacks and Salem 2009), with its detrimental effects on students’ physical and mental well-being being recognized as a pressing social, health, and educational concern (Abrams 2013). Bullying constitutes a violation of children’s human rights and fundamental freedoms. Legal intervention against school bullying is essential to protect victims’ rights, correct perpetrators’ misconduct, and safeguard children’s physical and mental integrity (Chen and Han 2023). Since the release of the first official policy document on school bullying prevention, Guiding Opinions on the Prevention and Control of Bullying and Violence Among Primary and Secondary School Students (hereinafter referred to as the Guiding Opinions), issued in 2016 by nine government departments, including the Ministry of Education, China has introduced and amended multiple legal and policy documents, thus gradually advancing the legal framework for school bullying prevention and control (Liu and Ren 2024). As the primary entities responsible for implementing antibullying measures, schools have increasingly become the focus of both academic and governmental attention, with growing expectations for them to assume broader social responsibilities (Ren 2019).

From a legal perspective, a school’s responsibility for preventing bullying stems from its obligations to ensure safety and protect the rights and interests of students. The first obligation refers to the duty of a school, as the institution is responsible for managing and operating educational services for minors, to safeguard their personal and property safety when they enter the school premises. This duty is defined by law (Yao 2020). The second obligation concerns the school’s responsibility to protect students’ legitimate rights and interests, as stated in Article 30 of the Education Law of the People’s Republic of China. These obligations arise from both public law and private law. In terms of public law, such as education law and administrative law, Chinese primary and secondary schools are required to comply with government management and guidance when exercising their educational rights. They are predominantly public institutions with a nonprofit nature and a focus on child welfare, making them subjects within the administrative relationship of education. Compulsory education, as stipulated in the Compulsory Education Law of the People’s Republic of China, is a public welfare activity that the state must ensure, and the safety and rights protection duties of schools fall under administrative responsibilities, supported by laws such as the Education Law and the Compulsory Education Law.

From the perspective of private law, such as civil law, contract theory argues that schools, as legal entities engaged in educational activities, have the same duty as other civil entities to take reasonable measures to protect the safety and well-being of their “customers” (i.e., students). The theory of guardianship transfer, among other theories, suggests that when students enter school, parents’ guardianship is transferred to the school, either through delegation or guardianship agency (Tong 2007). This creates a trust relationship among the school, the students, and their guardians, who have reasonable expectations that the school will safeguard their interests. Furthermore, with respect to the protection of the right to education, bullying that causes victims to lose focus in class, develop a fear of attending school, or even hinders their ability to study constitutes an infringement of their right to education. As the executor of education and the guardian of the right to education, the school is naturally obligated to address behaviors that infringe upon this right within its premises. Countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan have established legal frameworks for combating school bullying, aiming to enforce the duty of bullying prevention through legal means.

From a legal and regulatory perspective, the evolution of schools’ obligations in bullying prevention has undergone three distinct phases: from self-regulation by schools to administrative guidance from education authorities and, ultimately, to formal legal codification. Prior to 2016, there was no specific legal basis for schools to address bullying, and incidents were largely handled in accordance with the Measures for the Handling of Student Injury Accidents (2002), which focused on general student injury cases rather than bullying-specific issues. A pivotal shift occurred in 2016 when the State Council’s Education Supervision Committee issued the Notice on the Special Governance of School Bullying, marking the government’s recognition of school bullying as a distinct governance issue. This was followed by the Guiding Opinions and the Comprehensive Governance Plan for Strengthening the Prevention and Control of Bullying Among Primary and Secondary School Students (2017) (hereinafter referred to as the Governance Plan), which, at the level of regulatory documents issued by education authorities, explicitly designated schools as the primary entities responsible for handling and addressing bullying incidents. These documents, although low in legal hierarchy and limited in binding force, were the first to establish schools’ obligations in bullying prevention (Xiao and Huang 2022). In 2020, this school obligation was elevated to the legal level with the extensive revision of the Law on the Protection of Minors. Article 39 of the revised law explicitly mandates that “schools shall establish a student bullying prevention and control system and provide education and training for staff, teachers, and students on bullying prevention.” This mandate marked a fundamental shift from nonbinding administrative guidance to a legally enforceable duty. Following this legal codification, the principle of school accountability in bullying prevention was further reinforced through subsequent regulatory measures. The Ministry of Education issued Regulations on the Protection of Minors in Schools and the Special Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Bullying Among Primary and Secondary School Students. These documents imposed more specific responsibilities on schools. Most recently, in 2024, the Notice on the “Standardized Management Year” Action for Basic Education included school bullying on the “negative list” of issues requiring rectification in the governance of basic education. This move signals a continued effort to institutionalize antibullying measures and compel schools to adopt more effective strategies in both prevention and response.

This approach—imposing and reinforcing certain legal obligations on schools through legal regulations—aligns with academic expectations and mirrors the models adopted by most developed countries. Many scholars and foreign legislative practices suggest that establishing specific obligations for schools can include more bullying incidents under statutory regulation, thereby increasing the effectiveness of antibullying measures (Feng and Chen 2020). However, the role of schools is dual in nature. They are both public educators and potential bearers of liability for school bullying. When these two roles overlap, their expected function in preventing bullying may be compromised. The educational mandate of schools, coupled with China’s long-standing exam-oriented education system, has led to an institutional emphasis on academic performance, graduation rates, and teaching quality. Excessive legislative imposition of bullying prevention obligations could potentially undermine schools’ inherent public education functions and disrupt the traditionally harmonious relationship between legal and educational domains (Feng 2018). In other words, if schools are burdened with excessive legal responsibilities in school bullying, they may become entangled in frequent bullying lawsuits, making it difficult to maintain a stable educational environment. This situation could lead to unintended negative consequences. Studies have shown that some schools have not properly fulfilled—or have only partially fulfilled—their legal obligations in bullying prevention (Zhang et al. 2024). Problems such as the failure of mandatory reporting mechanisms (S. Li 2024), ineffective detection of bullying incidents, and delayed victim assistance remain prevalent. To comply with the legal obligations set forth in the Law on the Protection of Minors, some schools have simply integrated bullying prevention into their existing safety management policies without implementing targeted measures (Q. Chen 2024). Others have developed antibullying plans merely to meet inspection requirements rather than to achieve substantive prevention.

Theoretically, after the Law on the Protection of Minors established schools’ obligations at the legal level, schools should have become more proactive in fulfilling their responsibilities. However, a gap remains between legal expectations and actual school practices. Why does this discrepancy exist? What is the root of this discrepancy? Is it reasonable to reinforce schools’ bullying prevention responsibilities through legal regulation? How should school responsibilities be improved in the future? To explore these questions, this paper outlines the basic logic and mixed-methods approach for sample selection in Section 2. Section 3 presents the results of the coding analysis and t-test regarding schools’ responsibilities in judicial decisions. Section 4 discusses the assumption and balance of schools’ antibullying obligations, including both the theoretical foundations and the empirical evidence supporting bullying prevention efforts in schools. This section also highlights the challenges schools face when implementing these obligations, as evidenced in the sample cases analyzed. Section 5 of this paper offers four recommendations for improving schools’ antibullying responsibilities and outlines potential pathways for enhancing their role in preventing and addressing bullying. This paper aims to clarify the circumstances under which schools have been held accountable by examining cases of school bullying, thereby elucidating the role of schools in bullying prevention and control, revealing the existing problems, and providing recommendations for refining schools’ legal responsibilities. Furthermore, this paper aims to serve as a reference for improving the legal framework regarding school responsibilities.

2. Sample Selection and Research Design

It is reasonable and legally sound to support that schools should bear certain responsibilities in bullying prevention. However, in practice, the extent to which schools fulfill these antibullying responsibilities remains unclear, and the actual significance of school-based prevention efforts requires further empirical validation. So, in the study of schools’ responsibilities in bullying prevention and improvement strategies, two key issues must be addressed. First, under the existing legal framework, it is essential to examine the specific circumstances in which schools are held accountable for failing to fulfil their bullying prevention obligations. This clarification serves three purposes: (1) delineating the current state of school antibullying implementation, (2) highlighting common practical shortcomings, and (3) establishing a foundation for refining institutional accountability in the future. It can be determined through case analysis. Second, it is crucial to assess whether a school’s failure to meet its antibullying duties negatively influences the mental harm experienced by victims, thereby demonstrating the importance of schools’ role in preventing bullying. Here, we primarily examine the relationship between school liability and the psychological harm suffered by victims of bullying through quantitative analysis, that is, whether the failure of schools to fulfill their obligations in preventing and addressing bullying, and thereby assuming liability, has an adverse impact on the psychological harm experienced by the victims. The reason for observing psychological damage rather than physical damage is the harmful characteristics of school bullying. Theoretically, physical damage will directly manifest along with bullying behavior, and schools cannot intervene in the instantaneous harmful results. However, the psychological trauma and mental damage caused by bullying tend to develop gradually alongside bullying behavior (Roland 2002). If a school fails to properly address and respond to bullying, factors such as the bully’s subsequent behavior and the school’s permissive attitude will likely continue to exacerbate the victim’s psychological harm.

2.1. Basic Logic and Approach for Sample Selection

In the context of China’s legal system, one of the meanings of school liability is the civil liability arising from damage to the bullied party due to the school’s failure to fulfil its antibullying obligations (by action or omission). This type of liability stems from the civil legal relationship between the school and the students (Qin and Zhang 2020), which is based on the equality of civil subjects. Therefore, studying civil cases where schools have been held liable provides insight into the school’s performance in fulfilling its antibullying duties. In terms of case analysis, the authenticity and objectivity of judicial documents make them the best observational samples. The “facts found by the court after trial” section in judicial decisions represents information obtained through strict evidence collection and cross-examination. This factual and objective content offers a comprehensive reflection of the school’s performance and the victim’s harm. The “court’s opinion” section clearly explains the reasons for holding the school accountable. In summary, using civil judgments related to school bullying meets the needs of this research.

The China Judgments Online platform, operated by the Supreme People’s Court, is a public platform that publishes effective judicial decisions from courts at all levels. It is the largest and most authoritative website for accessing case information in China. All cases cited from third-party websites also originate from China Judgments Online. The website is characterized by openness, transparency, and authority, allowing for public access to all published judgments. In this paper, “school bullying” and “student bullying” were used as keywords, resulting in the selection of 240 relevant judgments related to school bullying from the China Judgments Online platform. Among these, 194 were civil judgments. After duplicate information from retrials and second-instance cases were excluded, 155 cases were retained as complete and detailed samples of school bullying cases.

2.2. Methods

This paper employed a mixed-methods research approach to examine specific circumstances of school responsibility and its link with the mental distress experienced by bullied students. Regarding the circumstances of school liability, this study adopts a textual analysis approach. First, primary textual analysis: the author conducted a close reading of all 155 judicial rulings, systematically extracting and categorizing original text segments pertaining to school liability. Second, pattern identification: cases demonstrating substantive commonalities were thematically grouped through an iterative classification process. Finally, A three-level coding analysis method employing open coding, axis coding, and selective coding was used. The author identified the following circumstances of school liability based on the antibullying requirements for schools stipulated in the Law on the Protection of Minors, as well as relevant provisions regarding institutional responsibilities in the Regulations on School Protection of Minors and the Special Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Bullying Among Primary and Secondary School Students:

- Failure to provide antibullying education and training for faculty and students.

- Failure to immediately intervene in bullying incidents.

- Failure to provide timely psychological counseling, education, and guidance to affected students.

- Failure to report severe bullying cases to authorities.

- Failure to promptly address potential risks.

These circumstances constitute the third-level coding framework for case analysis, with each category corresponding to specific circumstances identified in judicial cases.

The researcher established a coding analysis framework on the basis of the obligations for the prevention and control of school bullying in the 2020 revised Chinese Law on the Protection of Minors, combined with the school responsibility rules in the Regulations on the Protection of Minors in Schools and the Work Plan for the Special Governance Action to Prevent Bullying among Primary and Secondary School Students issued by the Ministry of Education of China.

Regarding the relationship between school liability and psychological harm to bullying victims, this study employs an exploratory design methodology. The exploratory design refers to a design in which the qualitative phase is conducted first, and then the quantitative phase is conducted to help confirm the quantitative data. During the preceding phase of textual analysis of judicial rulings, the researcher concurrently examined the mechanisms through which school liability impacts the psychological harm experienced by bullied students in the documented cases. For this study, the researcher created a conceptual map of the themes, wrote a thematic passage, and developed a narrative story. Following the textual analysis, a quantitative approach with descriptive statistics and a t-test was applied to verify the associations between school duties and mental damage. SPSS 25.0 was used for the data analysis. The degree of mental damage was assigned a scale of 5, ranging from mild to severe: 1 = no obvious damage; 2 = mild mental disorder or psychological problem; 3 = moderate mental disorder; 4 = severe mental disorder; and 5 = suicidal behavior. This paper used the determination of whether a school was responsible in judicial cases as a grouping variable to compare the degree of mental damage of bullied students in cases where the school was not responsible with that in cases where the school was responsible and to determine whether there was a significant difference between the two.

3. Research Findings

3.1. Coding Results: Causes and Circumstances of School Responsibility

On the basis of the coding analysis, the common cause for schools being held accountable was their failure to adequately perform bullying prevention duties, which either caused or exacerbated harm to the victim. These circumstances can be categorized into the following three main types: 1. Inadequate prevention: This is manifested through insufficient safety education and failure to comply with duties related to surveillance and patrols. The failure of schools to implement proper preventive measures to create a safe environment for students is a key contributing factor. 2. Problems in responding to bullying: This includes situations where the bullying went unnoticed, the school ignored the bullying, condoned the behavior, or failed to eliminate conditions that could lead to bullying. These situations violate the school’s safety obligations in student management and were the most frequent circumstances identified in the cases. 3. Improper handling of bullying: This includes instances where the school failed to provide timely assistance to the victim, failed to notify relevant parties, or did not take necessary actions to intervene. This failure violates the school’s responsibility to assist victims following a bullying incident and properly address the situation. Table 1 below illustrates these findings in more detail.

Table 1.

Coding analysis results.

In reviewing the cases, the author found that, in many instances where schools were held responsible, the victims experienced significant mental harm. In some cases where the school failed to act, the psychological damage to the victims was particularly severe. For example, in a 2020 case in Jilin Province (Civil Judgment No. 653 2020), the homeroom teacher was aware that the plaintiff was being bullied by being forced to wash the bully’s socks and prepare foot baths but failed to take effective action. As a result, the plaintiff endured bullying for more than a year and a half, and their mental state progressively deteriorated. In a case in Guangdong (Civil Judgment No. 75 2022), after the victim, Deng, reported being bullied and beaten by He to the homeroom teacher, the school failed to intervene in a timely manner. This failure allowed for Deng to suffer further retaliatory bullying, worsening both the physical and mental harm he experienced. In some cases, the school’s neglect led students to lose hope, even resulting in tragic outcomes. For example, in a case in Shanghai (Civil Judgment No. 24142 2019), the school’s simple management approach caused the plaintiff immense psychological pressure. The plaintiff felt burdened with the label of being a liar and faced ridicule from classmates, which ultimately led them to attempt suicide by jumping from a building. Thus, the author asserts that there is a significant relationship between the school’s responsibility and the mental harm suffered by the victim in bullying cases. This relationship stems from the school’s neglect, improper handling, or delayed response, which allows for bullying to continue or intensify, thereby exacerbating the psychological damage to the bullying victim.

3.2. T-Test Results

Descriptive statistics revealed that 20.65% (N = 32) of the judicial cases were reported among students in primary school or below, 61.29% (N = 95) were reported in junior high school, 9.68% (N = 15) were reported in senior high school, and 8.39% (N = 13) were reported in vocational high schools or others. Additionally, 32.9% (N = 51) of the schools were held responsible in judicial cases. In terms of mental damage, 39.35% (N = 61) of the students showed no significant impairment, 28.39% (N = 44) had mild mental disorders or psychological problems, 12.90% (N = 20) had moderate mental disorders, 14.19% (N = 22) had severe mental disorders, and 5.2% (N = 8) displayed suicidal behavior.

A between-groups t-test analysis was conducted to assess whether school liability status (responsible/not responsible) significantly affected victims’ mental health outcomes. Table 2 reports that the bullied students whose schools were held responsible in the case had higher levels of mental damage than their counterparts did (mean difference = −0.705). The t-test results indicated that the difference was significant at the level of 0.05 (p < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 1.197). The results of the t-test confirm the author’s hypothesis: In cases where the school is responsible, the psychological harm suffered by bullied individuals tends to be more severe. This finding aligns with the persistent nature of campus bullying and the cumulative effect of bullying-related harm (Smith 2014). For detailed t-test results, see Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of mental damage between two groups.

4. Discussion: The Fulfilment and Balance of Schools’ Antibullying Obligations

The aforementioned empirical study directly reveals common institutional failures in school bullying prevention, while indirectly validating the critical importance of timely intervention. Collectively, the findings demonstrate that schools’ antibullying obligations are justified on three grounds: ethical rationale, legal principles, and empirical evidence. However, some schools’ negligence in fulfilling these obligations may stem from the inherent difficulty in balancing their core educational mission with antibullying responsibilities.

4.1. The Critical Role and Prevailing Challenges of Schools in Bullying Prevention

Schools are the central pillars in the governance of campus bullying, play a pivotal role in both preventing and addressing bullying, and are arguably the most effective public entity for this purpose (Stewart and Fritsch 2011). From an educational perspective, the advantages of schools in bullying prevention are as follows:

Access to specialized educational resources: Schools possess professional and readily available educational resources, enabling them to maximize educational interventions to address bullying (Ren 2019).

Main socialization agents: Schools are the primary site for students’ socialization, and factors within schools—such as academic performance, teachers’ evaluations of students, and peer relationships—greatly influence adolescent behavior and deviations, thereby directly contributing to the emergence of bullying behaviors (F. Li 2017).

School climate: School climate is the spiritual core of a school. A positive and healthy school environment has a significant negative predictive effect on bullying and reduces the risk of bullying behavior. Conversely, a poor school climate can exacerbate bullying risk, especially when students lack support from family or peers (Cohen et al. 2009; Turner et al. 2014). Therefore, schools are responsible for fostering a safe and supportive environment (Q. Chen 2024).

Primary venue for bullying: Schools are the primary places where bullying occurs. As the first responders and adjudicators, the school and its decisions regarding bullying significantly influence the development of bullying situations and can impact the potential for future bullying behaviors (Q. Chen 2020). Thus, schools are both strategically positioned and legally obligated to play a central role in combating bullying.

This empirical study shows that schools’ failure to intervene in bullying in a timely manner exacerbates the psychological harm to victims, thus indirectly highlighting the importance of schools responding promptly to campus bullying. This aligns with the cumulative nature of the psychological damage caused by bullying. The persistent and repetitive characteristics of campus bullying undermine the mental health of victims and gradually intensify their psychological damage (Guerin and Hennessy 2002). Research has shown that repeated bullying can have a cumulative effect on victims’ psychological harm (X. Chen 2022). In the sample cases, there were extreme instances where depression developed into suicidal tendencies. Therefore, if a school fails to address bullying promptly after it occurs, does not adequately assist the victim, or even allows bullying to continue, the victim’s psychological state becomes more fragile, their sense of safety decreases, and their mental harm worsens.

In practice, schools’ deficiencies can be categorized into three main types: inadequate prevention, neglect or tolerance of bullying, and failure to address bullying incidents promptly and properly. Current judicial rulings indicate varying degrees of severity among these institutional failures. Based on established causal relationships between school conduct and detrimental outcomes, courts have identified three particularly consequential patterns: failure to provide timely relief to victims; failure to promptly intervene, allowing bullying to persist; and disregarding student reports of bullying. These scenarios demonstrate the most significant causal links to victim harm, resulting in heavier civil liabilities for schools. In contrast, preventive shortcomings like insufficient safety education or inadequate monitoring are considered less severe, as courts recognize that while prevention cannot completely deter bullying occurrence, active neglect or mishandling directly exacerbates victim harm. This judicial perspective reveals that both improper response and inadequate prevention fundamentally constitute failures in fulfilling antibullying obligations, differing only in the magnitude of negligence.

In summary, there exists a solid foundation—legislative, judicial, and theoretical—for holding schools accountable for bullying prevention. Yet why do some schools persistently fail in their duty of care and safety obligations? How do schools perceive their antibullying responsibilities?

4.2. The Challenge of Balancing School Obligations

In the sample cases, the schools argued that they faced the following two difficulties in fulfilling their bullying prevention responsibilities:

First, schools struggle with the lack of a legal framework for bullying prevention. Currently, China does not have specialized legislation on school bullying. Only a few provinces and cities have enacted local antibullying regulations, such as the Tianjin Regulations on the Prevention and Management of School Bullying. At the national level, policy documents such as the Guiding Opinions and Governance Plans issued by the Ministry of Education are administrative guidelines with weak legal binding force and vague provisions. The Minor Protection Law provides only a general principle regarding school bullying. The absence of specific legislation affects schools’ ability to establish comprehensive prevention, response, and handling procedures. Consequently, schools may fail to implement adequate educational prevention measures and face challenges such as misjudging (mistaking playful interactions for bullying), overlooking (failing to recognize relational bullying, verbal bullying, and cyberbullying), delayed responses, and improper handling (Zhang et al. 2024).

Second, schools lack appropriate measures to address school bullying. Although China has gradually recognized the importance of disciplinary action and has mentioned the need to discipline bullies in various policy documents, the implementation remains cautious. The Rules on Disciplinary Measures in Primary and Secondary Education (hereinafter referred to as the Disciplinary Rules) were introduced with the intent to provide schools with legal support for imposing discipline. In practice, however, teachers and schools remain highly cautious about enforcing disciplinary actions, often adopting a passive or hesitant stance (Y. Chen 2021). On the one hand, schools face pressure from multiple parties when implementing disciplinary actions, including the bully, the victim, and their respective parents. Sometimes, the parents of bullied students, driven by a retributive justice mindset, advocate for “using bullying to stop bullying” (Gu 2019). Meanwhile, the parents of the bully often argue that “it takes two to tango”, questioning why only their child should be punished. On the other hand, legal provisions on disciplinary measures remain ambiguous. The Disciplinary Rules state that schools “should implement educational discipline”, whereas the Law on the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency stipulates that schools “may take management and educational measures.” The distinction between “should” and “may” directly affects the extent and legitimacy of school disciplinary authority (Liu and Ren 2024).

In addition, the above is only one aspect of the issue. The fundamental problem lies in the fact that a school’s primary goal is to fulfil its public education function. Under the current evaluation system, prioritizing antibullying efforts faces significant obstacles. Schools are, by nature, educational institutions. Under the long-standing influence of “exam-oriented education” and the “score-only mentality”, most schools focus primarily on improving student performance and increasing graduation rates rather than preventing school bullying (Liu and Xu 2020). Although the CPC Central Committee and the State Council issued the Overall Plan for Deepening the Reform of Education Evaluation in the New Era in October 2020, aiming to correct misguided educational evaluation orientations and resolutely overcome the stubborn ailments of score-centrism, diploma-centrism, and advancement-centrism, the entrenched nature of these issues makes them difficult to eliminate overnight (Liu and Wei 2021).

School resource allocation and curriculum design still prioritize academic performance, with subjects such as Chinese, mathematics, and English taking precedence. In contrast, legal education—mainly delivered through “Morality and Rule of Law” courses—is often regarded as insignificant or even dispensable (H. Li 2020). Unlike academic achievements, bullying prevention is an “invisible” task with no immediate, measurable “performance” outcomes. Intervention and corrective measures are time-consuming and labor-intensive, and homeroom teachers in China already juggle multiple responsibilities, leaving them with insufficient time and energy to focus on bullying prevention and intervention.

In practice, many schools believe that openly acknowledging bullying incidents could harm their reputation. Admitting to the presence of bullying might trigger a “one-vote veto” from educational authorities that would negatively affect the school’s evaluation and performance assessments of key administrators. As a result, some schools and teachers hold a hidden belief: As long as bullying does not appear, it does not exist, and the school does not need to intervene. Bullying is perceived as a safety and stability issue that becomes “important” only once it has already occurred.

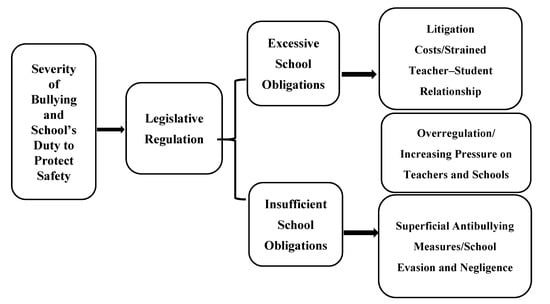

Therefore, the fundamental issue in motivating schools to prevent bullying lies in balancing their educational mission with their responsibility for bullying prevention. The sample cases reveal a critical legislative gap: the absence of dedicated antibullying laws has left schools without clear legal frameworks for prevention (“no laws to follow”). This evidence strongly suggests that specialized legislation is now imperative to provide schools with actionable guidance. However, the enactment of specialized legislation would signify the formal prioritization of schools’ antibullying obligations within the legal framework. Given schools’ public education function and certain nonprofit attributes, it is also necessary to prevent them from being frequently entangled in litigation due to excessive bullying prevention responsibilities, which could undermine their ability to maintain normal educational operations (Feng 2018, as illustrated in Figure 1 below). This dilemma requires legislators to use the authority of the law to balance the competing interests arising from schools’ bullying prevention obligations. The legal framework can optimize the coexistence of different stakeholders’ needs, ensuring both effective bullying prevention and the preservation of schools’ core educational functions.

Figure 1.

The balance framework of school responsibility.

5. Recommendations: Balancing and Improving School Antibullying Responsibilities

Balancing school responsibilities in bullying prevention through the legal framework and unlocking schools’ antibullying potential is key to addressing the aforementioned issues. On the one hand, it is essential to maximize the role of existing laws and regulations at different levels and ensure clarity and balance in school responsibilities within the top-level legal design. On the other hand, schools should be granted a certain degree of autonomous disciplinary authority, while policy measures should provide clear guidance on common challenges in bullying prevention, thereby enhancing schools’ capacity to combat bullying effectively.

5.1. Basic Logic of Defining School Responsibilities in the Legal System and Foreign Experiences

In addressing the issue of balancing school responsibilities, the United States, Japan, and the United Kingdom, which represent common law and civil law systems, have adopted different legislative models. The specialized antibullying legislation in the United States includes state bullying law, state model bullying policies, and school district bullying policies (Rose and Pierce 2012). When formulating antibullying legislation, individual states typically reference the predominant characteristics of school bullying incidents within their jurisdictions. Regarding the issue of school liability, the U.S. has employed an indirect approach in its antibullying legislation, avoiding direct specification of schools’ duties in state bullying laws. Instead, it requires school districts to develop antibullying policies, granting schools the authority to impose disciplinary measures (Gallagher 2002). The law indirectly forces schools to take antibullying actions while also outlining the core elements and minimum requirements of state model bullying policies and school district bullying policies for schools to reference. In general, school district bullying policies are more comprehensive than state model bullying policies. The district policies provide the most direct requirements and guidance for schools to implement bullying strategies. Some districts have a greater degree of discretion when formulating their policies. Another reason for urging public school administrators in the United States to establish antibullying policies is the gradual judicial recognition of schools’ roles and responsibilities through court precedents, compelling schools to develop policies and procedures to address bullying (J. Lin 2017). When lawsuits against schools arise from bullying incidents, courts will evaluate whether the school has fulfilled its obligations by examining the adequacy of its antibullying policies.

In contrast, Japan has attempted to address bullying directly through national-level legislation with the School Bullying Prevention Law, which, as superior legislation, established fundamental principles for combating school bullying and defined the legal relationships among relevant entities (L. Lin 2020). This law mandates that schools properly handle bullying issues and protect students’ rights. As stipulated in Article 13 of this law, schools are required to develop specific methods on the basis of a unified policy and local prevention measures (Toda 2016). This provides legal systemic support for the implementation of the School Bullying Prevention Law, further clarifying schools’ responsibilities. UK law has strengthened the regulation of teacher and school duties at the regional level. In England and Wales, the law has specifically expanded the authority of teachers (Middlemiss 2012); in Northern Ireland, the Bullying Incident Management Law requires schools to keep detailed records of bullying incidents and strengthens the oversight of schools.

The commonality among these three countries’ legal systems is that, at a high legislative level, they outline the basic responsibilities of schools in preventing and addressing bullying. At the local level, antibullying policies are supplemented and implemented, while schools are given some degree of authority to handle bullying cases. The differences are as follows: In the U.S., the state or district bullying policies can be seen a part of state bullying law, and the state bullying law serves as the minimum standards for policies at the state or school district level, imposing stringent binding requirements on policy formulation. This reflects a progressive legislative model with tiered implementation. In contrast, Japan has relatively fewer local policies, because the School Bullying Prevention Law stipulates comprehensive provisions encompassing extensive antibullying elements. This represents a national-level legislative model. Meanwhile, the UK adopts a region-centric legislative approach. However, regardless of the legislative model adopted, all three aforementioned countries establish school antibullying responsibilities through laws or regulations occupying superior positions within their respective legal hierarchies.

In the context of China, although there have been persistent calls from academia for specialized antibullying legislation, enacting a nationwide antibullying law remains premature. Given China’s vast territory and diverse ethnic composition, economic conditions, cultural norms, and customs vary significantly across different regions (Huang 2017). Implementing uniform standards nationwide without considering regional differences may be counterproductive. In recent years, the frequent revisions of laws related to bullying, such as the Law on the Protection of Minors and the Law on the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency, indicate the government’s preference for addressing bullying within the existing legal framework rather than imposing additional pressure on schools and other stakeholders through specialized legislation. Therefore, a more suitable approach at this stage would be to leverage the Legislation Law to optimize the hierarchical structure of legal norms and stimulate schools’ proactive role in bullying prevention. Specifically, the following measures should be considered: 1. Strengthening schools’ fundamental antibullying obligations within national legislation to establish a clear baseline for responsibility. Similar to the three aforementioned countries, China’s top-level legislation should establish schools’ fundamental responsibilities in bullying prevention and intervention. 2. Granting schools a certain degree of discretionary authority in local regulations to enhance their proactive role in bullying prevention and intervention. In local legislation, it is necessary to expand the provisions related to school liability in the law and to grant schools the authority to develop bullying prevention programs based on their specific circumstances. 3. Developing more detailed bullying prevention measures in policy guidelines (just like state/district bullying policies in the U.S.) to address common issues of noncompliance in school practices and reinforce their responsibilities. The content should be specific, clear, and actionable.

5.2. Enhancing Schools’ Fundamental Antibullying Obligations in the Law

Schools bear antibullying responsibilities and corresponding liability for torts because they have a legal duty to manage and protect minor students (Lao 2004). Clearly, defining schools’ obligations in legislation can serve as a reference for courts when determining a school’s tort liability in litigation, thereby encouraging schools to better fulfil their prevention duties.

Moreover, establishing schools’ obligations in the law provides educational authorities with a basis for inspecting and assessing a school’s antibullying practices, further urging schools to meet their antibullying responsibilities. Therefore, national legislation should stipulate the basic elements of bullying prevention, response, handling, and redress. Under the current legal framework, the Law on the Protection of Minors not only protects the physical and mental health and legal rights of minors but is also the only law that specifically mentions school bullying and school protection. Given its high legal status and binding force, this law can be improved to establish the fundamental antibullying responsibilities of schools.

From a legal principle perspective, the provisions of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Protection of Minors regarding school obligations are rather simplistic—it merely stipulates that schools must establish a system for preventing and controlling bullying without detailing how to implement such a system. It neither provides any specific directives for teachers and staff, who are on the front lines of confronting bullying and implementing prevention measures, nor addresses redress for victims. In some of the legal cases mentioned above, schools ignored bullying, neglected the victims, and failed to identify prolonged bullying incidents, thus highlighting the shortcomings of overly simplistic regulations. In future legislative revisions, there should be an emphasis on enforceability and on recognizing teachers and staff as the primary agents of bullying prevention to strengthen schools’ efforts in identifying and addressing bullying.

From the perspective of fundamental educational responsibilities of schools and teachers, every adult in the school should provide and create a safe learning and growing environment for children (Hu 2018). Therefore, all school staff and teachers must publicly demonstrate their opposition to any form of school bullying and concretely and consistently fulfill their duties as required by antibullying laws and police. The legal provisions may strengthen schools’ management responsibilities through the following stipulations: (1) Schools must implement their own antibullying plans, allocate the necessary time and resources to assess their bullying situation, and provide training in antibullying strategies for all staff. (2) Educational authorities should conduct regular inspections of schools’ antibullying measures. (3) Teachers and staff must intervene immediately to stop any bullying behavior and, on the basis of these circumstances, propose appropriate remedial actions. (4) Schools should pay attention to the physical and mental well-being of victims and offer them the necessary help and support. (5) Schools should regularly assess campus bullying and promptly address any incidents that are identified. (6) Each school shall designate an antibullying officer, form a bullying prevention team, and hold the principal accountable as the chief responsible person.

5.3. Granting Schools a Degree of Autonomous Disciplinary Authority

Granting schools a certain degree of autonomous disciplinary authority serves two main functions. First, it enhances schools’ proactive initiative by enabling them to create and maintain a safe and supportive environment tailored to their own circumstances, which can be achieved by allowing schools to develop their own antibullying plans. Second, it reinforces the central role of schools in combating bullying by providing them with the necessary authority to address bullying incidents effectively. This provision requires legislation to strengthen schools’ power to intervene and impose disciplinary measures.

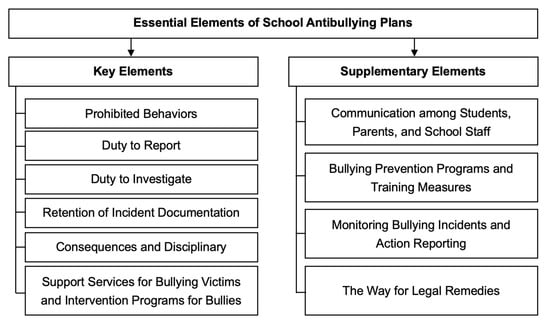

A school’s own antibullying plan is a typical expression of its autonomous disciplinary authority. The reductions in school bullying are closely associated with classroom rules, classroom management, and disciplinary methods. Moreover, a positive school atmosphere can effectively decrease the occurrence of bullying. Schools possess the most comprehensive understanding of their own classrooms, curricula, campus environment, facilities, teaching quality, and parental characteristics. Therefore, allowing schools to develop their own antibullying plans tailored to their specific circumstances maximizes their proactive capacity, prevents conflicts between bullying prevention and academic instruction, and aligns with the reality that educational policy orientations and school management capabilities differ across regions in China (Feng and Chen 2020). Moreover, given that the causes, methods, and consequences of school bullying are highly complex and require schools to make judgments based on specific circumstances, provisions that allow schools a certain degree of discretion in handling bullying cases would enable them to choose appropriate responses tailored to local conditions. For example, vocational high schools and key high schools have different educational objectives, and the frequency of bullying may also vary between them. It is more appropriate for each type of school to develop its own antibullying plan on the basis of its specific circumstances. Obviously, the content of the antibullying plan should, based on being in line with the essence of local antibullying laws and policies, exceed the basic requirements stipulated by law. In particular, it should detail the everyday management of bullying prevention, including the criteria for determining bullying, reporting procedures, the responsibilities of homeroom teachers, handling processes, and redress procedures. This will create a stable, long-term, and binding antibullying plan that allows for an efficient response when bullying occurs. Additionally, the plan should include antibullying initiatives that schools can choose and implement on their own, such as specific antibullying projects, courses, models for parent–school cooperation, and methods for collaborating with public security and judicial authorities. Schools may refer to the Figure 2 below when developing their antibullying programs.

Figure 2.

Essential elements of school antibullying plans.

It is also extremely important to clarify the authority of schools and teachers in handling and disciplining bullying incidents. On the one hand, teachers must be granted the right to take coercive measures. Sudden bullying incidents in schools—especially those involving physical violence—are a primary focus of school prevention efforts. These incidents are intensely immediate in nature; when teachers encounter violent bullying, they must act swiftly to prevent the danger from escalating. In these situations, teachers may find that they can achieve effective student management only by resorting to measures that infringe upon the physical aspects of students’ personal rights (Zhang and Wang 2017).

For such cases, foreign legislation grants teachers the authority to take coercive measures. In the United Kingdom, the Education and Inspections Act of 2006 stipulates that when a student engages in illegal or criminal behavior, teachers have the power of staff members to use force (Department for Education 2006). In Japan, the School Education Law states that when a fight occurs between a student or a student directs violence against a teacher, the use of reasonable force by teachers to halt the violence or for self-defense does not constitute corporal punishment (School Education Act 1972). In the United States, when students engage in physical altercations or when a student uses violence to harm other classmates, teachers are permitted to use force within reasonable limits to control the situation. Moreover, only when the restriction of freedom in a particular context is deemed unreasonable and excessively apparent does the physical restraint of a student by a teacher or administrator violate the Fourth Amendment (Walace v. Batavia Sch. Dist. 1995). To protect student safety, prevent the escalation of harmful outcomes, and maintain normal teaching order, legislation should, within the bounds of reasonableness, grant teachers the authority and leeway to implement immediate coercive measures. Teachers shall be authorized to take necessary coercive measures to stop ongoing school bullying.

Moreover, at the school level, it is necessary to clarify how the Disciplinary Rules should be applied in cases of campus bullying. In the current regulatory documents on campus bullying governance, the content related to educational discipline merely confirms that disciplinary actions can be taken against bullies but does not specify how or what types of discipline should be imposed (Xiao and Huang 2022). This lack of detail creates a disconnect between disciplinary norms and bullying governance: schools know that they are permitted to use disciplinary measures, yet they are uncertain about which specific measures will achieve a punishment that is proportionate to the offense. Consequently, awkward situations arise where bullies become overly cautious in the face of discipline while victims are left without adequate redress. In the absence of separate legislation that specifically addresses disciplinary authority, educational authorities can, at this stage, issue normative documents to guide the application of the Disciplinary Rules in aligning educational disciplinary measures with particular bullying scenarios. Additionally, schools can, on the basis of their own circumstances, specify the exact situations and applicable rules for disciplining bullies within their own antibullying plans. For example, schools can refer to the tiered and categorized approach in the Disciplinary Rules for dealing with violations and disciplinary offenses and classify student bullying into three levels: “mild bullying”, “severe bullying”, and “very severe bullying” for identification purposes (Liu and Ren 2024). Different educational disciplinary measures can then be established for each level of bullying behavior.

5.4. Key Considerations for Schools in Bullying Prevention

The coding analysis indicated that, in practice, schools still make several errors in their approach to bullying prevention, including inadequate preventative education, failure to detect bullying, ignoring bullying behavior, and not providing timely assistance to victims. Notably, negligence and inaction in response to campus bullying represent significant misconduct for which schools will inevitably bear responsibility. Consequently, schools must strengthen their measures in three key areas: prevention, response, and handling of incidents. Moreover, the guiding documents issued by educational authorities should offer detailed guidance on these aspects to ensure a more effective approach to bullying prevention.

It should be recognized that prevention is a “limited” responsibility—completely eradicating bullying is unrealistic—but failing to take preventive measures will only worsen the situation. Chinese judicial decisions also reflect this view, stating that when a school fails to fulfil its duty of safety education, bullying may or may not occur. While the school’s failure to act may not be the direct cause of the victim’s harm, it still constitutes a negligent omission in preventing bullying. In such cases, the school’s subjective fault is classified as negligence, and it must bear responsibility proportional to its degree of fault.

Case analysis reveals that some schools conduct bullying prevention education in a perfunctory manner, leading courts to rule that they have failed to fulfil their educational duties. Additionally, some boarding schools have been found to have inadequately enforced internal management regulations, thereby creating conditions that enable bullying. Therefore, schools should take a two-pronged approach: First, they must enhance bullying prevention education by fostering moral development and cultivating an antibullying school culture; second, they must rigorously implement campus patrol policies, particularly in boarding schools, where lapses in supervision can create opportunities for bullying. Schools should strengthen inspections of areas where bullying is more likely to occur, thereby reducing the environmental conditions that facilitate such behavior.

In terms of response, schools must fulfil their duty of care by identifying bullying behavior as early as possible and taking prompt action to prevent its continuation. Ignoring or neglecting bullying incidents is unacceptable. Teachers, as the primary actors in identifying and addressing bullying, play a crucial role. However, in practice law cases, some teachers failed to intervene even when they witnessed bullying, some did not recognize the harm already inflicted on students, and others left their posts during class, creating opportunities for bullying. Such negligence or inaction directly contributes to the persistence of bullying and exacerbates harm to victims. Research has demonstrated that providing teachers with bullying intervention training enhances their ability to implement effective prevention and intervention strategies, thereby reducing instances where teachers ignore or tolerate bullying behaviors (Bauman et al. 2008). Teachers should also proactively assess potential risks to students on the basis of their age, experience, attention span, emotional state, and ability to recognize danger. In bullying incidents, they must act with caution and reason to ensure students’ safety and well-being (Ahmed v. Glasgow City Council 2000). More importantly, the guiding documents should explicitly define reporting channels for campus bullying, ensuring that victims have a means to speak out when teachers neglect or tolerate such behavior. Schools should also conduct regular assessments of bullying incidents and establish practical response procedures to minimize inaction and negligence in addressing campus bullying.

To handle bullying incidents, schools have a duty of assistance and must provide timely aid to victims while promptly notifying their guardians. Schools should actively intervene when bullying causes direct or imminent harm or danger (Hou and Qin 2019). The immediate steps should include providing medical assistance to injured students and offering psychological support to both victims and bystanders who witness bullying incidents. Mental health support is particularly crucial. In the context of Eastern cultural influences, verbal bullying and relational bullying often cause severe hidden psychological harm, yet many schools fail to address students’ mental health needs. This neglect can trap victims in long-term psychological distress. To address this, legal frameworks should emphasize psychological relief mechanisms, including the following: 1. Mandating psychological support—Policies and regulations should require schools to establish psychological counselling infrastructure and mental health education programs to provide students with access to necessary mental health resources. 2. Compulsory post-bullying psychological counselling—Schools should be required to conduct psychological interventions for both the victim and the bully after a bullying incident. 3. Diversified mental health support options—Schools and local governments should provide multiple forms of counselling services, including school-based psychologists, hotlines, and community-based counselling centers, ensuring that students have access to professional psychological assistance when needed. Importantly, timely intervention and support are crucial for preventing further psychological harm to victims of bullying.

By institutionalizing these measures, schools can move beyond punitive responses and focus on restorative justice and psychological recovery, ensuring a safer and healthier environment for students.

6. Conclusions

In recent years, the Chinese government has increasingly prioritized addressing campus bullying. Since the 2020 revision of the Law on the Protection of Minors first introduced provisions on campus bullying, the legal governance of this issue has become an inevitable trend. However, compared with research on education and psychology, legal studies on campus bullying in China remain relatively rare, with even fewer empirical studies on legal regulation. This paper aims to fill that gap. Schools play a central role in preventing and addressing campus bullying. A key challenge faced by many countries is how to legally incentivize schools to combat bullying effectively without undermining their public education functions. Using 155 civil judgments as an observational sample, this study examined instances where schools were held accountable and evaluated the impact of school responsibility on victims. The findings indicate that despite the law imposing general obligations on schools, they often fail in prevention, response, and post-incident handling. Common issues include inadequate safety education, disregard for bullying incidents, and delayed assistance to victims. Notably, the effectiveness of a school’s response significantly influences the psychological harm suffered by victims. The key to balancing schools’ antibullying responsibilities lies in leveraging the effectiveness and function of different levels of legal norms. This requires not only refining schools’ fundamental obligations for prevention and intervention but also granting them appropriate authority to handle and discipline bullying while strengthening guidance on weak areas of prevention.

The academic value of this study is threefold: First, by clarifying schools’ antibullying responsibilities and identifying common institutional shortcomings in prevention efforts, this research enables schools to benchmark their current practices against the documented scenarios. Such awareness can directly improve antibullying interventions and inform future prevention priorities. Second, this study empirically confirms the adverse psychological impact of school negligence on victims. Specifically, when schools deliberately ignore bullying incidents or respond inappropriately, they inadvertently perpetuate bullying behaviors and exacerbate victims’ mental trauma. These findings serve as a critical reminder for educational institutions to (1) recognize the psychological dimension of bullying, (2) implement timely and proper interventions, and (3) prevent the perpetuation of abusive behaviors. Finally, from the perspective of balancing educational mandates and bullying prevention obligations, this paper proposes actionable recommendations for refining school accountability frameworks. This contribution provides legislators and policymakers with evidence-based references for delineating schools’ legal responsibilities and advancing the rule-of-law approach to bullying governance in China’s educational system.

Nevertheless, this study has certain limitations, primarily regarding sample size and selection criteria. Although over 200 bullying-related cases were initially identified on China Judgments Online, the final usable sample was reduced to 155 judicial rulings after excluding cases not legally recognized as school bullying and removing poorly documented instances. In addition, since bullying cases settled through mediation are not publicly available online, and there are very few administrative cases published online, this paper is unable to include such cases in the research sample. It is expected that, as the Chinese government enhances transparency in case disclosure, future research could incorporate more administrative bullying cases to examine schools’ performance in such proceedings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.C. and F.H.; methodology, F.H.; software, F.H.; validation, X.C., Y.J. and F.H.; formal analysis, F.H.; investigation, X.C.; resources, X.C.; data curation, F.H.; writing—original draft preparation, X.C.; writing—review and editing, X.C. and F.H.; visualization, Y.J.; supervision, X.C.; project administration, X.C.; funding acquisition, Y.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents] (Tier B) grant number [GZB20240339].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data in this article are sourced from publicly available judgments on China Judgements Online, and all relevant cases can be accessed by anyone through this platform.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abrams, Douglas E. 2013. School bullying victimization as an educational disability. Temple Political & Civil Rights Law Review 22: 273–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed v. Glasgow City Council: ScSf. 2000. July 26. Available online: https://swarb.co.uk/ahmed-v-glasgow-city-council-scsf-26-jul-2000/ (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Bauman, Sheri, Ken Rigby, and Kathleen Hoppa. 2008. US teachers’ and school counsellors’ strategies for handling school bullying incidents. Educational Psychology 28: 837–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. 2024. “Bullying”. October 28. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/youth-violence/about/about-bullying.html (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Chen, Qin. 2020. Preventing Campus Bullying: “Prevention First”—Analysis of US Anti-Bullying Legislation and Practices. Education Science Research, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Qin. 2024. Five Key Measures to Improve School Bullying Governance. People’s Education 3: 94–97. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Xuanyu. 2022. Legal Responses to Campus Bullying. Beijing: China Legal Publishing House, pp. 97–99. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Xuanyu, and Feng Han. 2023. The Jurisprudential Basis for Legal Governance of School Bullying: A Reflection on Child Protection and Simple Justice. Journal of Xinjiang University (Philosophy and Social Sciences) 51: 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Ying. 2021. How Can Educational Discipline Ensure the Steady and Long-Term Management of School Bullying? Contemporary Education Forum 6: 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China National Radio Network. 2024. Protecting Adolescents Series Investigation Part 1: The Hidden Truth Behind Frequent School Bullying Incidents. April 24. Available online: https://news.cnr.cn/dj/20240424/t20240424_526679006.shtml (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Civil Judgment No. 24142 of First Instance, Civil Division, Shanghai City Huangpu District People’s Court. 2019. Available online: https://wenshu.court.gov.cn/website/wenshu/181217BMTKHNT2W0/index.html?pageId=dbe699e3905bc980da38046a0691bdbf&s21=校园欺凌 (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Civil Judgment No. 653 of First Instance, Civil Division, Jilin Province Gongzhuling City People’s Court. 2020. Available online: https://wenshu.court.gov.cn/website/wenshu/181217BMTKHNT2W0/index.html?pageId=dbe699e3905bc980da38046a0691bdbf&s21=校园欺凌 (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Civil Judgment No. 75 of First Instance, Civil Division, Guangdong Province Shaoguan City Wujiang District People’s Court. 2022. Available online: https://wenshu.court.gov.cn/website/wenshu/181217BMTKHNT2W0/index.html?pageId=dbe699e3905bc980da38046a0691bdbf&s21=校园欺凌 (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Cohen, Jonathan, Elizabeth M. McCabe, Nicholas M. Michelli, and Terry Pickeral. 2009. School Climate: Research, Policy, Practice, and Teacher Education. Teachers College Record 111: 180–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Education. 2006. Education and Inspections Act 2006. November 8. Available online: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2006/40/pdfs/ukpga_20060040_en.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Feng, Kai. 2018. On School Obligations and Balancing Policies in U.S. Anti-Bullying Laws. Comparative Education Research 40: 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Kai, and Wenjia Chen. 2020. A Review of Legal Governance Issues in School Bullying in China. Shandong Social Sciences 3: 189–92. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, Cindy. 2002. Sticks and Stones Have Remedies at Law-It Is Name-Calling that Hurts Kids: Can State Anti-Bullying Statutes Really Help Kids Who are Victims of In-School Bullying. JL & Social Challenges 4: 21. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Binbin. 2019. From Severe Punishment to Mediation: The Evolution and Trends of School Bullying Intervention. Education Development Research 39: 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Guerin, Suzanne, and Eilis Hennessy. 2002. Pupils’ definitions of bullying. European Journal of Psychology of Education 17: 249–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Yanfang, and Yuehan Qin. 2019. Prevention and Handling of School Violence from the Perspective of Criminology. Law Forum 34: 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Chunguang. 2018. New York City’s Treatment Mode of School Bullying and its Enlightenment. Journal of Jianghan University (Social Science Edition) 35: 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Mingtao. 2017. Legislative Governance System for School Bullying Abroad: Current Status, Characteristics, and Lessons—A Comparative Analysis of Seven Developed Countries. Ningxia Social Sciences 6: 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Lao, Kaisheng. 2004. Research on Injury Accidents in Primary and Secondary Schools and the Attribution of Liability. Journal of Beijing Normal University (Social Sciences Edition) 2: 18. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Fangxia. 2017. Research on Campus Bullying Behavior and Intervention Strategies. Ningxia Social Sciences 3: 133–36. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Hongbo. 2020. Current Problems in Primary and Secondary School Legal Education and Solutions. Curriculum, Teaching Materials, and Methods 40: 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Siyuan. 2024. The “Failure” of Mandatory Reporting in School Bullying: Theoretical Analysis, Problem Review, and Institutional Reconstruction. Shanghai Educational Research 451: 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Jie. 2017. The Responsibility of School: The Lawsuits and Cases of School Bullying in America. International and Comparative Education 39: 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Lei. 2020. The Mechanism Construction of School Bullying Management from an International Vision. International and Comparative Education 42: 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Haifeng, and Huafeng Wei. 2021. A Historical Examination of the “Score-Only” and “Advancement-Only” Problems in Enrollment and Examination Reform. Education Research 42: 86–100. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Yang, and Haitao Ren. 2024. The Process of Student Bullying Governance and the Construction of a Legal System in China. Educational Development Research 44: 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Zhijun, and Bin Xu. 2020. Comprehensive Quality Evaluation: Key Measures to Break the “Score-Only” Assessment Model. Education Research 41: 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Middlemiss, Sam. 2012. Legal Protection for School Pupils who are Victims of Bullying in the United Kingdom. Education Law Journal, 237. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Tao, and Xudong Zhang. 2020. School Bullying Remedies from the Perspective of the Right to Education: Legal Logic and Pathways. Chinese Education Law Review 19: 128–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Haitao. 2019. Reflections and Reconstruction of China’s Legal System on School Bullying—A Review of the Comprehensive Governance Plan on School Bullying Issued by 11 Departments. Oriental Law 67: 123–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roland, Erling. 2002. Bullying, Depressive Symptoms, and Suicidal Thoughts. Educational Research 44: 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Donna M., and Vincent L. Pierce. 2012. Bullying-Analyses of State Laws and School Policies. Appendix C. New York: Nova Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks, Julie, and Robert S. Salem. 2009. Victims without Legal Remedies: Why Kids Need Schools to Develop Comprehensive Anti-Bullying Policies. Albany Law Review 72: 147–48. [Google Scholar]

- School Education Act. Law No. 26 of March 29. 1972. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/hakusho/html/others/detail/1317990.htm (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Smith, Peter K. 2014. Understanding School Bullying: Its Nature and Prevention Strategies. New York: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Daniel, and Eric Fritsch. 2011. School and Law Enforcement Efforts to Combat Cyberbullying. Preventing School Failure 55: 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, Yuichi. 2016. Bullying (Ijime) and related problems in Japan. History and research. In School Bullying in Different Cultures: Eastern and Western Perspectives. Cambridge: University Printing House, pp. 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Lihua. 2007. Minor Law: School Protection Volume. Beijing: Legal Publishing House, p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Isobel, Katherine J. Reynolds, Eunro Lee, Emina Subasic, and David Bromhead. 2014. Well-being, School Climate, and the Social Identity Process: A Latent Growth Model Study of Bullying Perpetration and Peer Victimization. School Psychology Quarterly 29: 320–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walace v. Batavia Sch. Dist., 101, 68 F.3d 1010 (7th Cir.). 1995. Available online: https://case-law.vlex.com/vid/wallace-by-wallace-v-892509110 (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Xiao, Denghui, and Xiangrui Huang. 2022. School Disciplinary Authority: The Primary Channel for Student Bullying Governance and Its Implementation Path. Research on Juvenile Delinquency Prevention 352: 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Jianlong. 2020. On School Protection–Focusing on the School Protection Chapter of the Minor Protection Law. Oriental Law 77: 117–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Li, and Guangqian Wang. 2017. N the Legal Regulation of Disciplinary Actions by Primary and Secondary School Teachers. Journal of Fujian Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition) 6: 101–13+177. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Qian, Le Cheng, Tian Tian, and Yannan Wu. 2024. The Practical Dilemmas of Teachers in School Bullying Prevention: Causes and Solutions. Educational Development Research 44: 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).