Abstract

The participation of families in socio-educational processes is a key topic in applied research, offering new strategies for family support. However, active participation in the research process itself remains a challenge. This study aims to define a participatory research process with mothers at social risk to co-produce a resource aimed at improving parenting skills. A qualitative, participatory approach was used with a peer research process, following the phases of preparation, audience, and validation with a group of mothers supported by social services. The results identified the phases of the process and the conditions and limits in each. Preparation included organizing the workshop logistics, recruiting participants, and holding an introductory session for those who chose to participate as researchers. In the audience phase, the sequence, use of materials, and generated group dynamics were highlighted. Finally, in the validation phase, dialogue and consensus were used as methods for discussion and decision-making. Incorporating mothers as researchers generates new perspectives on parenting in at-risk contexts and enables the creation of resources that better meet family needs. This participatory approach highlights the importance of including parents in research to develop more effective support tools for vulnerable families.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Involvement of Families in Parenting Support

In Europe, it has been observed that since the adoption of the Council of Europe Recommendation Rec (Consejo de Europa 2006), which promotes positive parenting, various forms of parenting support have proliferated. From this perspective, family support consists of a combination of information, support, education, training, counselling, and other measures or services aimed at influencing how parents understand and perform their roles as caregivers and nurturers (Daly et al. 2015). In the case of family support aimed at families in situations of risk and in difficulty in exercising parenting, scientific advances in working with families suggest a participatory approach. These risk situations refer to those in which the necessary conditions to ensure the well-being and development of children and adolescents are compromised. Among them is the lack of physical or psychological care, which can affect the fulfilment of their basic needs, as well as severe difficulty in providing adequate care for children. It also includes the use of physical and emotional punishment as a disciplinary method, lack of schooling, absenteeism, and school dropout, factors that can negatively impact children’s educational and social development.

Additionally, these situations encompass severe and chronic conflicts within the family dynamic, which can create an unstable environment for the child, and the inability to control their behaviour when it poses a risk to themselves or others. Moreover, discriminatory practices that affect their physical and mental well-being, such as gender-based violence, mutilation, or ablation, are also considered. According to Lacharité (2017), a participatory approach should be an essential strategy to prevent situations of child abuse as well as for intervention when the child’s safety and development are compromised. According to Toros et al. (2018) “family engagement is associated with family members’ active involvement and family and social service professionals working together with an emphasis on the quality of the relationship” (p. 599).

This approach requires focusing the intervention on a joint analysis of the family, considering how parents respond to children’s needs, as an essential strategy to prevent situations of child abuse as well as for intervention when the child’s safety and development are compromised (Lacharité 2017). The family’s self-assessment and capacity to observe their reality, strengths, and deficits are fundamental when working with a family at risk. According to Lemay (2013), a joint assessment between professionals and the people involved supports the awareness process about their own reality; it also entails the acquisition of new knowledge about their circumstances; and it transforms their view of the situation. Asking those who are involved about their reality and how they have lived and experienced it allows them to self-assess their process (Osterling and Han 2011) and to acquire new knowledge about their situation. Being aware of family achievements implies recognition of the family’s capacity, which generates feelings of efficiency and of control of the situation (Lemay 2013). When parents and children are asked, they reflect on and become aware of their own parenting skills and competencies, and the strengths and deficits they may have. Family engagement in the context of child welfare practice (Toros et al. 2018) is the key element to enable moving forward. The family’s perceptions of their reality allow us to know what the motivation, attitudes, and commitment are for change (Lindsey et al. 2014; Staudt 2007; Yatchmenoff 2005). This participatory approach considers the family’s point of view as the central element not only to understand the needs of children, but also to facilitate intervention using services developed for families (Balsells et al. 2019). The strength-based participatory approach is being explored in a growing number of studies on child neglect and abuse (Chamberland et al. 2014; Léveillé and Chamberland 2010; Milani et al. 2011). In this type of intervention, efforts are made to maximize the families’ strengths and to assist them in making choices to improve their situation rather than imposing solutions.

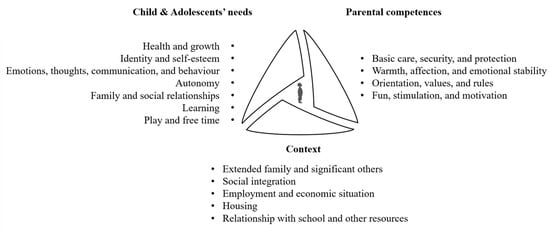

This participation requires resources and adequate strategies to support families, for example, use of the Triángulo P+ (Balsells et al. 2023). This is a visual participatory resource to promote parenting within the family unit. It is a graphic representation that summarizes parenting along three fundamental dimensions: (1) the needs of children and adolescents (C&A); (2) the parental competencies to fulfil those identified needs; (3) the contextual factors that play a role in supporting the process of meeting those needs (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Triángulo P+ (Balsells et al. 2023).

This resource is inspired by the Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and Their Families (Department of Health 2000) and by three subsequent participatory initiatives: L’initiative AIDES: Une Approche Centrée Sur les Besoins des Enfants Vulnérables (Chamberland et al. 2012), PAPFC: Cadre d’Analyse Écosystémique des Besoins de Developement des Enfants (Lacharité 2017), PIPPI: Il Modelo Multidimensionale “Il Mondo del Bambino” (Milani et al. 2013), and the program Caminar en Familia (Balsells et al. 2015).

The design of Triángulo P+ implies that it is a valid resource for parents’ and children’s self-assessment of parenting, being consistent and participatory in approach. It comprises three dimensions (Mateos et al. 2021) as follows: (a) Behavioral dimension: participation is considered in terms of the use of services, of assistance obtained using formal resources, and of participation in activities; (b) Attitudinal or emotional dimension: expressed in terms of the quality of the relationship with professionals, and of the commitment, motivation, and acceptance of help; (c) Cognitive and interpretative dimension: in which the family becomes the focus of the assessment process of their own actions and learns to assess their own efficiency with an ecological view of the children’s needs.

1.2. The Involvement of Families in Research

Participation of the people involved is becoming increasingly common in research in different fields of study. Participation becomes especially significant for children in situations of risk or of vulnerability (Dixon et al. 2019; Mitchell et al. 2010), as it has important implications for their well-being and development (Tisdall 2017). The same applies to the families of children at risk. Participatory research methodologies emphasize the responsibility of the research team ensure the real participation of those involved in the research and to seek a balance of power between the researchers and the people involved. As Flewitt et al. (2018) and Templeton et al. (2019) point out, there are huge differences between researchers’ inferences of results and the perspectives of the people involved. In this sense, Dillon (2018) claims that there is a challenge of sharing power between the researchers and the people involved. This implies an assumption of the principles of social inclusion and reciprocity (Davidson 2017). Following the Lundy model of child participation (2007), the research design should enable those involved to have space to express themselves, whereby they are actively heard, such that their ideas and opinions are valued and adopted. To this effect, the researcher must be a facilitator who helps participants to produce knowledge about themselves (Bouma et al. 2018). Although the number of studies advocating for this participatory approach is increasing, many studies are still in the initial stages where research is based on consultation (Dixon et al. 2019). Participatory research should not be limited to just consulting participants, but should aspire to produce knowledge and resources between the researchers and the participants (Mateos et al. 2020) using peer-research or co-production approaches. Ground-breaking results (Urrea-Monclús et al. 2023) obtained suggest that there are four phases in which the participants must be present during the research design: (1) The preparation phase, where thought is given to how to provide space, time, and a suitable format for the participants to express their opinions; (2) The audience phase, where thought is given to how the participants can express their suggestions; (3) The validation phase, where thought is given to how the information gathered from all the agents involved in the process is triangulated; and (4) The transference phase, where thought is given to how the results are transmitted to society and influence policy. Erta-Majó and Vaquero (2023) found that using a transmedia approach supports equality of position and provides the freedom to produce resources. These can facilitate production of resources in different media and active participation of some of the consumers in the production process, hence becoming “prosumers” (both producers and consumers) (Jenkins 2006; Vaquero et al. 2022). The intention is to bring research closer to those affected, and for the resulting products to have greater significance for them and their peers. As Majee et al. (2022) suggest, involving the people affected in the assessment of their needs can improve the value of the information obtained, which, in turn, can facilitate better allocation of community resources, such as, for example, those related to social support, employment, housing, or education.

Given the benefits of the participatory approach in supporting families at risk, as well as the advances in participatory research processes, is it possible to conduct participatory research with families at risk to co-construct a family support resource? The current state of knowledge in the field of family participation highlights the limited research built by, for, and with families.

Building knowledge in a participatory way requires considering participants’ lived experiences. Moreover, the co-creation of knowledge with families who face challenges in parenting is particularly relevant for developing interventions that address their needs as they express them. In this article, we consider how to develop a co-construction process with families at risk that enables their knowledge to more directly inform the development of resources that facilitate participatory intervention.

1.3. Research Questions and Objectives

Given the proliferation of participatory approaches in family intervention. in research, and in the very definition of parenting, is it possible to conduct a participatory study to co-produce the intervention resources with and for the receiving families? How should a participatory study be carried out with the population at risk to co-produce strategies and resources for family intervention? What steps, constraints, and possibilities arise from the application of the precepts of participatory study with families in a situation of risk or at high social risk?

The objective of this study is to propose a participatory research process using a peer-research approach to:

- Establish the phases of a participatory research process with mothers in situations of risk, focused on the co-production of a resource for self-assessing parenting practices.

- Identify the elements of each phase that facilitate the process of participatory research with mothers at risk through application of the Triángulo P+ co-production approach.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

This study follows a qualitative and participatory approach focused on a process of peer research. As Dixon et al. (2019) state, peer research considers the knowledge of the people involved (e.g., mothers) and the academic knowledge of the researchers to be equally important. In this regard, mothers assume the role of researchers who produce knowledge about themselves. In this approach, the professional researchers take the role of accompanying and helping the mothers to generate this knowledge.

The current study follows the phases of the participatory research process proposed by (Urrea-Monclús et al. 2023). The process and results of the preparation, audience, and validation phases are presented.

2.2. Participants

The participants of this study were mothers who were experiencing difficulties in parenting skills, as described in the Triángulo P+ (Balsells et al. 2023). These mothers were users of social services, and their children were at social risk.

The participants comprised 5 women, aged between 29 and 46 years old, with an average age of 37. Single-parent families represented 60% of the families whereas 40% were nuclear families composed of a father and a mother. Mothers with two children represented 60%, mothers with one child represented 20%, and the remaining 20% were mothers with more than two children. The children were aged between 2 and 14 years.

Following Fugard and Potts (2015), a small group of participants was selected to obtain deeper, more nuanced, and individualized data. In the preparation phase, they were considered as participants as the sessions were designed by professional researchers. In the audience and validation phase, the mothers were also considered co-researchers. Their experiential knowledge was valued at the same level as academic knowledge. Their lived experiences and perspectives were not only a source of data, but also part of the co-construction process of knowledge. This recognition aligned with participatory research approaches that seek to bridge the gap between academic and experiential knowledge, recognizing mothers as active contributors to the research process.

2.3. Instruments

Three different methods were employed to gather data. Firstly, the professional researchers’ field journals were used with details (number and date of the session, number of attendants, and other information that might be of relevance for the results) and session notes with texts and graphics related to the following four key elements:

- Sequence: in what phases the session is organized.

- Formats: what formats are chosen to communicate and why.

- Group atmosphere: how group atmosphere impacts production. Influenced by age, gender, place of origin, and others.

- Materials/resources: assessment of their adequacy and sufficiency.

To identify information about the field journal, two variables were controlled: the correspondence of the field journal with the mothers and the session number. This provided the respective identification codes, for example: FJM (mothers) s8 (number of session).

Secondly, the audio recordings from the mothers’ speeches during the group meetings. In order to identify the mothers’ speeches, three variables were controlled: the correspondence of the speeches with the mother-researchers, the phase of the research (preparation, audience, and validation) in which they were collected, and the session number. This provided the relevant identification code, for example: SM (mothers) V (validation) s9 (session number).

Thirdly, the outputs of each dimension of the Triángulo P+, collected in different formats depending on the output’s features: audio, image, and text.

2.4. Procedure

The design of the co-production workshop began with selecting the most appropriate methodological approach, considering the study’s context and specific objectives. In this case, a participatory research approach with a peer-based perspective was chosen, with the study deliberately assigning participants the role of co-researchers.

Following Dixon et al. (2019), this approach actively and non-hierarchically engages participants by equipping them with tools to leverage their knowledge and experience within the study. In this framework, the professional researcher assumes the role of facilitator, guiding the process and supporting participants in generating knowledge about themselves and their reality.

Once the methodology and participant roles were established, the detailed planning of the co-production workshop began, ensuring coherence with the selected approach and alignment with the study’s overarching objectives.

The workshop consisted of eight sessions, each lasting 90 min, with specific objectives, activities, and participatory strategies tailored for each session. The first session introduced the process, fostering a supportive group environment, and providing participants with essential information.

The next six sessions were structured into two blocks, each corresponding to one dimension of the parenting triangle. The sequence involved identifying categories about children’s developmental needs, parental competencies, or contextual factors influencing responses to these needs, defining these categories, and designing relevant practical resources to support other parents. The last session was concerned with validating the resources generated.

The next step involved recruiting participants. To facilitate this, the research team established an agreement with the social services team at Council of Lleida. Family support professionals identified parents who were already receiving assistance from social services and who might be interested in participating in the study.

The research team then conducted an initial recruitment session. During this session, researchers from [anonymized] presented the study’s objectives. Those families who chose to participate attended an induction session, where they received an overview of the study’s goals, of the content, and of the methodological process. This session also clarified and reinforced the role of mothers as co-researchers.

Following this, eight co-production workshop sessions took place at a socio-educational service center supporting at-risk families. These sessions, held twice a week for two hours each, were facilitated by two researchers from University of Lleida. A social services worker attended the sessions to support the facilitation of the sessions and to observe the group dynamics.

Finally, a concluding session was conducted with all the participants to assess their level of agreement with the results to validate the resources generated.

2.5. Data Analysis

Multi-modal data were collected (Perry 2020), that is, in different formats: audio, images, and text. The analysis used a data triangulation process (Aguilar and Barroso 2015) according to the following: the content of the speeches recorded in the researchers’ field diary; the content of the audio recordings of the mother-researchers; and the content of the products produced by the mother-researchers.

An analytical approach was used based on content analysis (Rapley 2014; Valles 2009). In this sense, three levels of analysis were established:

- Thematic classification of the information collected through the creation of a category system (Table 1). This process consisted of the following:

Table 1. Category system.

Table 1. Category system.- The most relevant aspects of the available information were identified. On several occasions, all the information was reviewed, and this task was repeated at different stages of the content analysis process.

- The information obtained from the different data collection tools was compared, aiming to gather fragments of shared ideas. To do this, annotations and colors were used to identify the various dimensions, categories, and subcategories.

- Description of the content, including comments from the participants regarding the specific topics being discussed at each moment. Textual quotes or images were selected that pertinently illustrated the topic studied according to their clarity and significance.

- Theoretical interpretation of the content of the information collected. The initial theoretical developments were taken up to interpret the content and draw conclusions.

All the analyses followed the principles of credibility and internal validity, reliability, and understanding of the quality of the research (Gibbs 2012).

3. Results and Discussion

The results obtained inform how to develop a complete participatory research process through a workshop on co-production. The results of the three phases—preparation, audience, and validity—are presented and discussed in this section.

3.1. Preparing the Workshop on Co-Production

The results show that the preparation phase must take into account at least the following three aspects: (1) the organization of the sessions (dates, time, place, etc.); (2) recruiting participants; and (3) the induction session for the people who have decided to participate as researchers.

3.1.1. Organization of the Sessions

The organization of the workshop requires special attention to the following key aspects to promote participation of families at social risk: the frequency, place, and time of the sessions, role assignation, and strategies for recruiting participants. The Lundy (2007) child participation model was taken into consideration. This is a specific model for children, which emerged as a way of promoting engagement of a part of the population that has been considered vulnerable for a long time. It was determined that the Lundy model could be equally valid with other types of vulnerable population, such as mothers at risk.

Regarding the place and time of the sessions, it was agreed that these would take place in the facilities of a socio-educational intervention service with families at risk in the [anonymized]. It was also decided that sessions would last two hours and would take place twice a week in the morning. These decisions were made to facilitate the continued attendance of the participants. Following the participation model from Lundy (2007), the impact of space was considered during the participation phase and, therefore, the place where the sessions took place was close and familiar to the participants. The time of the sessions was planned according to participant needs.

The periodicity and time of the workshop were adapted to promote participation, with the sessions reduced to once per week for a three-hour session. This was deemed necessary because some mothers worked, and some others attended training courses, making it difficult for them to participate in more frequent sessions.

The role of the professional researchers, as well as of the mother-researchers, is another aspect that was settled in the preparation phase. The professional researchers had to guide the activities during the session and guide the mother-researchers so that they could produce knowledge. As Bouma et al. (2018) state, the researcher is a facilitator who helps participants to build knowledge about themselves. In this case, the participants, the mothers, took a role as researchers and were in charge of the creation of knowledge through their own experiences. They are understood to be experts on their experiences and capable of generating content. According to (Xanthopoulou et al. 2022), there are a lot of benefits for people at risk by using this approach.

The complexity of this approach resides in designing the sessions so that the mother-researchers become empowered and can fulfil their role. This modification entails a change in the role of the professional researchers as well since they now have to oversee understanding of the perspectives of the people involved (Flewitt et al. 2018; Templeton et al. 2019). As Dixon et al. (2019) point out, those involved must become subjects of the research. In this study, it was observed that clarifying the roles of all the participants promoted a balance of power between the professional researchers and the mothers. According to Urrea-Monclús et al. (2023), the relationship among the researchers has to be formulated from a horizontal and non-hierarchical framework. Each person contributes with their own perspective. In this study, the mothers involved are always considered active subjects and are part of a participatory peer-research study according to the Dixon et al. (2019) classification.

3.1.2. Recruitment of Participants

Participants were recruited during a group session with experiential dynamics related to the triangle of parenting. The same methodology from the workshop was replicated so that the participants could become familiar with the proposed experience.

During the recruitment process, researchers explained the scope of the study and its implications, the information about the sessions (dates, time, place, etc.), and the activities they would need to complete to generate knowledge. Moreover, they were also informed of the role of all the people involved in the study and the consent forms were signed. As Bouma et al. (2018) claimed, we could observe that providing all the necessary information to the mothers resulted in them being capable of generating a real opinion about the workshop. Likewise, the relevance of first impressions was confirmed, and how welcoming participants and transmitting expectations have a direct impact on the participation of the people involved (Rodrigo et al. 2011).

3.1.3. Induction Session

The induction session with the mothers who agreed to participate in the study had two parts. First, they were reminded of the objective of the study, and the utility of the workshop was emphasized. This was designed to provide meaning to their contributions to obtain a resource that will help other families relate to one of the main strategies for achieving family resilience. Lietz (2013) found that “helping others” is a factor that mobilizes and consolidates resilience of the people who are offering it. Secondly, the sequence of the learning process that would be conducted in different sessions through group dynamics was detailed. The proposed activities were well received by the participants who talked about them freely. We were able to understand the group atmosphere and detect the need for guidance and support to complete the tasks.

“It is deemed necessary to include a professional to guide the group, remind them of the initial instruction and of the final objective”.FJMs1

The induction session served as a first introduction to the formats that could be used to co-produce the different dimensions of the Triángulo P+. From the whole range of format proposals and options, the participating mothers were free to choose the formats they preferred since allowing researchers to make their own decisions is the basis of peer-research (Dixon et al. 2019). The participants decided to use images alongside an explanatory audio recording to create the output of the session.

“When the group is reaching an agreement, the idea of putting together images with an explanation (audio) emerges. The group considers that other parents will understand the output better.”FJMs1

This session had an important role for the mother-researchers. It allowed them to experience their role as researchers, gave them knowledge about the research process, and they became familiar with the different formats for production available to them. According to the criteria provided by Bouma et al. (2018), the information given generated trust and assurance for the participants to share their opinions and generate knowledge. At the same time, this session allowed them to adjust their role within the group and become aware of the group atmosphere and the needs and preferences of the participants. Consequently, the induction session became the road map for the subsequent sessions.

3.2. Audience: Development of the Sessions on the Workshop on Co-Production

The audience phase consisted of co-production sessions: group sessions based on the experiential method with participatory, reflective, and productive dynamics. The results were organized around the four key elements outlined in the field journal and the session notes of the professional researchers: (1) sequence, (2) formats, (3) group atmosphere, and (4) materials and resources.

3.2.1. Sequence

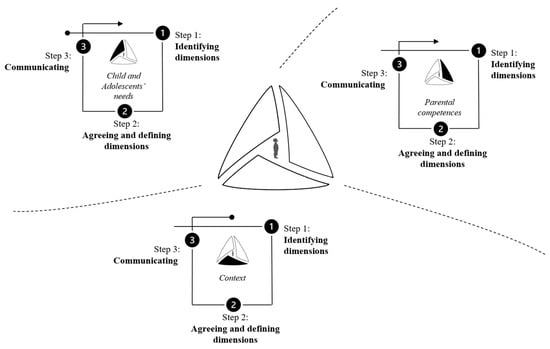

The results obtained helped to establish a methodological sequence to achieve a shared vision of parenting by creating resources for the Triángulo P+ (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sequences of the audience phase.

The sequence consisted of two sessions for each side of the triangle:

- Identifying dimensions: what are the developmental needs of the C&A? What parental competencies provide an answer to these needs? What contextual elements are necessary to respond to these needs? How can these be grouped?

- Agreeing and defining dimensions: looking for agreement on the definition of each dimension from the mother-researchers’ point of view.

- Communicating: How are each of the dimensions explained to other parents? This step consisted of creating a product that would help other parents understand the Triángulo P+. They used the content from steps 1 and 2, chose the format of the output, and created it.

The identification and agreement and definition steps were conducted as planned, in one single session, but for the step about communicating the decisions, more sessions were needed. The number of mother-researchers was limited, which prevented creating subgroups as had been planned. Consequently, the whole group of participants had to produce all the dimensions of the Triángulo P+. Moreover, the mothers needed greater support from the professional researchers during the creation of the content of their outputs given their situation of risk. The literature highlights that parents in families that experience negative events associated with social and/or economic crisis (Jaque et al. 2018) and which have high levels of parenting stress (Pérez Padilla et al. 2014) question their parental role as well as acknowledgement of their own learning (Valdés and Castro-Serrano 2017). More specifically, they required support in narrowing down the elements that would appear during the group discussion and in remembering the final objective of the workshop. As predicted during the induction session, this implied dedicating more time to completing the session which affected the whole sequence.

“The professionals observe that there are difficulties to reach an agreement to produce a single output. Therefore, it is important to guide them so that the output is original, agreed and non-personal”FJMs1

This three-step sequence was repeated to complete each side of the Triángulo P+ and allowed the mother-researchers to gain confidence in generating content and during the production process. They were given time and recognition so that they could develop their identity as learners (Valdés and Castro-Serrano 2017), since the external recognition helped them to see themselves in that role.

The importance of the order in which content was developed is another important result. Starting with the C&A needs helped establish the relationship with the parental competencies and with the context. In this regard, the idea of an adjusted perception of the parental role and the acknowledgment of children as individual subjects became more frequent in the participants’ speech. In this regard, the results indicated a positive evolution. During the first sessions on the C&A needs, the spontaneous speech revolved around the mothers’ care. A lack of perspective and attention to the C&A were observed in line with the work of (Rodrigo et al. 2009) with families at social risk. The authors identified a lack of adaptability to children’s needs as a common characteristic of parenting in situations of risk. Progressively the speeches evolved, and the explicit acknowledgment of the children’s needs allowed reflection about the interrelation between the dimensions of the Triángulo P+.

“I believe that we need to properly shower our children, properly get them ready, properly shower them”.Children’s output about C&A needs: Health and Growth

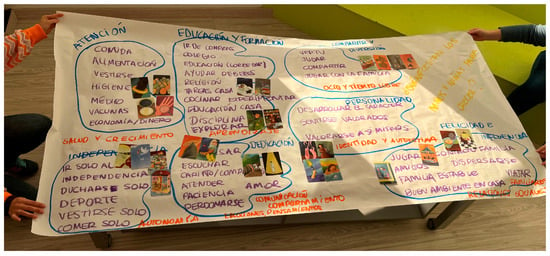

Occasionally, participants need to be reminded that they have to explain the C&A needs (Figure 3) and that they will have other spaces to talk about the competencies. Nonetheless, we recognize the importance and relevance of the process happening in this way since it demonstrates the importance of the interrelations of the parenting triangle.

Figure 3.

Identification of C&A needs.

“The title/label that appears in the literature has helped them reflect on each dimension”FJMs5

3.2.2. Formats

The mother-researchers chose the formats to create the outputs for each dimension of the Triángulo P+. However, the professional researchers had to promote decision-making and provide proactive support for the mother-researchers in the process of making decisions. The professional researchers sought to recognize their knowledge (Valdés and Castro-Serrano 2017) and to value them as generators of content (Bouma et al. 2018).

“The professionals allowed participants to debate the easiest and more understandable format for other parents. From the beginning, they did not have a clear opinion, and the professionals had to remind them about the final objective several times. They did so by giving examples.”FJMs3

The format was chosen according to the following: (1) how they would like to be informed about it, (2) how they would explain it to other people, and (3) the influence of the completed activities in the steps of identification, agreement, and definition.

The participants felt comfortable with audio formats (C&A needs) and simple and clear images alongside text (parental competencies and context). They refused more complex formats.

“It was considered that narration (explain it with their own words) was the best way for the message to reach parents and explain it to them. The professionals suggested whether the explanation could be done as a podcast, an interview… but they preferred a short and straightforward explanation.”FJMs3

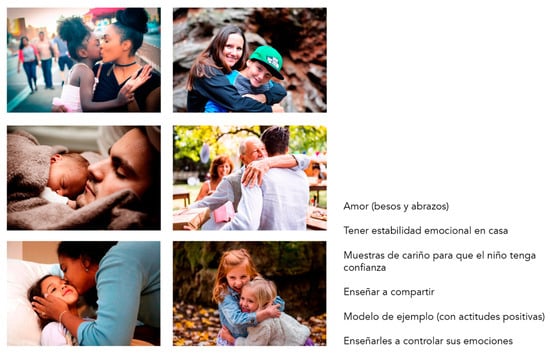

Similarly, abstract illustrations were used for the previous activities to define the needs. This made it more difficult for mothers to relate them to the content and consequently they decided to communicate through audio recordings. In contrast, real images were used to define parental competencies and context. The mother-researchers highly appreciated the images since they could make the connection with their family lives. However, they considered that images could have multiple interpretations. Therefore, they used images with explanatory sentences (Figure 4) to communicate these dimensions.

Figure 4.

Mothers’ output about parental competencies: Warmth, affection, and emotional stability.

“We can determine that the definition through images facilitates comprehension. Images from Dixit are far more abstract, and they struggle to identify them and understand the meaning.”FJMs5

The format of the real images allows them to make connections with their lives. They also use their own examples to express the ideas they have. FJMs6

3.2.3. Group Atmosphere

Regarding the dynamics of the group, four relevant aspects were observed: (1) size of the group, (2) group atmosphere, (3) group learning, and (4) regularity of attendance.

The development of the workshop with five participants allowed us to confirm the arguments from Fugard and Potts (2015). They argue that greater depth, perspicacity, and individuality are achieved with small groups. In this study, the professional researchers guided and helped all the participants closely throughout the whole sequence of co-production. The mothers’ lack of experience and insecurities required the constant clarification of concepts and of the objectives. These barriers were overcome by the relationship of trust created between the professional researchers and the mother-researchers, as well as their recognition as experts (Lindström et al. 2024).

Respect and team spirit permeated the group atmosphere. This allowed the mother-researchers to feel comfortable to participate in the activities. On the other hand, the participants shared some common features and experience in parenting which resulted in mutual support, an aspect that has been acknowledged as a benefit of group methodology in the parental education of families at social risk (Rodrigo et al. 2010).

“It is worth highlighting that the group was very comfortable, maybe because they were mothers, with children of similar age and shared experiences.”FJMs1

The shared creation of knowledge between the professional researchers and mother-researchers was another result. The sessions based on group learning (Balsells et al. 2015) promoted the creation of a shared construct after sharing knowledge, joint reflections, and building consensus about parenting.

“It is worth pointing out that the peers were respected when giving the opinion and that discourse was organized according to what the other mothers had explained.”FJMs1

Regarding attendance, the mother-researchers’ varying commitments caused changes in the day and time of the sessions.

“Due to their personal agendas, it was difficult for the mothers to participate in the study twice a week. That is why it was decided to conduct one session per week, with a longer duration.”FJMs4

3.2.4. Materials and Resources

Real images and representative signs were used on each of the dimensions of Triángulo P+. These resources were the driving force from which the mother-researchers were able to generate content. Using visual resources and materials allowed them to create connections between the content and their lived experiences. At the same time, this type of material helped the participants to express themselves and eliminated some idiomatic barriers that existed within the group (Kenny et al. 2023).

3.3. Internal Validity of the Outputs

The validation phase consisted of ensuring that the final outputs accurately reflected the dimensions defined by the participants. The outputs were revised and analyzed by the mother-researchers before their publication.

The group session on validation was conducted in a room at the University, as opposed to the place where the audience phase was conducted—the social service facilities. This choice resulted in a greater recognition of the role of researchers for the mothers. At the same time, their contributions helped to establish the final result of the outputs. Each output was shown and assessed before either accepting or modifying it.

The outputs related to the dimensions of the C&A needs and parental competencies were jointly created. Their validation consisted of checking that the understanding of the output was unambiguous. The mother-researchers confirmed the understanding of the outputs and their appropriateness for a specific audience. They commented on their satisfaction when observing their outputs and on the fact that these outputs could help other people in situations similar to theirs.

“… to help other people who can learn with our opinion”SMVs9

“it depends on what we learn, other people… we can explain it to other people and that is why it is important that they have a guide as to how to do it.”SMVs9

“it is important because with our contributions we can help the people who are developing the project and circulate it among other families.”SMVs9

The outputs related to the contextual dimensions were designed together, but the production was conducted by the professional researchers due to lack of time. In this case, the mother-researchers had to validate the final output according to what they had imagined.

Another result from the validation phase was the need to constantly keep in mind the role of the mothers as researchers and to reach consensus about the proposed changes through open questions and dialogue. The joint reflection led to making decisions and reaching consensus about the changes that had to be implemented in the outputs so that these could be transferred without influence by the professional researchers’ subjectivity.

4. Conclusions and Implications for Practice

This study has confirmed the relevance of a peer participatory research model involving mothers at social risk. Participation of this group is in its early stages and has been limited by systemic and methodological issues, as indicated by Levac (2013). Key elements for each phase of the participatory research model—preparation, audience, and validation—were identified to ensure the optimal development of the research (Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4). The study highlighted that, although the research followed a peer-led approach, the level of participation of those involved is not a fixed standard; rather, it is a decision that must be adjusted in accordance with the study’s objectives, the context, and the capacities of the professional research team. This result reinforces the findings of Fortin et al. (2014), Yang (2019), and Sonsteng-Person et al. (2023), who applied participatory research models in different risk situations. Consequently, varying degrees of responsibility may be assigned to participants as researchers throughout the different stages of the study. For instance, they may be involved in the initial design and preparation phase, contribute to the formulation of objectives, and participate in the dissemination of findings. Alternatively, they may be involved after the design phase, engaging in fieldwork, analysis, and the interpretation of research outcomes.

Table 2.

Aspects that facilitate the preparation phase.

Table 3.

Aspects that facilitate the audience phase.

Table 4.

Aspects that facilitate the validation phase.

Beyond merely describing the experience, this study proposes a structured framework for peer participatory research, establishing the essential phases of the process and the key facilitators within each stage. Through the co-production of the Triángulo P+, it was observed that the participation of mothers contributes to the development of a socio-educational resource for self-assessment in parenting, employing accessible language adapted to the understanding of families at social risk. Additionally, this model allows for a deeper understanding of parenting practices among the participating mothers. Moreover, the findings indicate that being in a situation of social risk does not constitute a barrier to research participation. On the contrary, they suggest that engaging mothers as researchers enables the emergence of new perspectives on parenting in contexts of vulnerability, grounded in their lived experiences and expertise in child-rearing.

These findings reinforce the notion that peer participatory research, when appropriately structured, can yield robust results with greater validity for those directly involved. All of the above underscore the value of peer participatory research as a strategy for ensuring that both research undertaken and policy derived from this should be rooted in a profound understanding of the needs and perspectives of those who directly experience these realities. The proposed methodology and the insights gained may serve as a reference for future research seeking to incorporate groups in situations of vulnerability into processes of co-producing knowledge.

5. Limitations

A limitation of this study is the lack of flow during the activities due to the inconsistent attendance of the participants and their socio-educational level. The use of abstract materials created difficulties in making connections among the concepts from the mothers.

An additional limitation worth mentioning is the participation of mothers only, excluding the fathers’ perspectives. As Vizoso-Gómez (2024) point out in their systematic revision of child abuse and parental burnout, some authors support the idea that mothers are more committed to raising their children and tend to actively participate in research.

6. Future Research

In future research, it would be necessary to expand the validation phase with external validation whereby other parents could assess the adequacy of the outputs created by the mother-researchers. Moreover, in agreement with the model followed (Urrea-Monclús et al. 2023), it would be interesting to analyze the last phase of transference, when the outputs are put into use and their efficacy and utility can be tested.

It would also be interesting to repeat this study with parents who are not in a situation of risk to observe what outcomes are generated based on different parental experiences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.-T. and M.À.B.; Methodology, A.B.-T., M.À.B., A.U.-M. and S.R.-P.; Validation, S.R.-P.; Investigation, A.B.-T.; Resources, A.U.-M.; Data curation, S.R.-P.; Writing—original draft, A.B.-T., M.À.B. and A.U.-M.; Writing—review & editing, M.À.B.; Supervision, M.À.B.; Funding acquisition, M.À.B. and A.U.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was developed by the research group GRIAF (Research group in Childhood, Adolescence, and Families) (2021 SGR 00513), and it was financed by the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, the Spanish State Research Agency and the European Regional Development Fund (PID2022-137305NB-C21).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Lleida (protocol code CERT07 and 2020-01-01).

Informed Consent Statement

Following the ethical and data protection criteria, the mothers were informed and confirmed their consent by signature for their role as mother-researchers, for their acknowledgement as the authors of the resulting outputs, and for the audio recordings and pictures taken during the workshop. The documents are kept by the professional researchers. It is worth mentioning that the mothers’ participation in the study was voluntary. Moreover, the mothers were informed that they could leave the session should they feel uncomfortable. As a reward for their generous and active participation as researchers, the mothers were invited to a session of personal care once the workshop was completed.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available at https://modeloframe.com/.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Department of “Inovación y Acción Social” of the City Council of Lleida for their invaluable support in conducting this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aguilar, Sonia, and Julio Barroso. 2015. La triangulación de datos como estrategia en investigación educativa. Píxel-Bit, Revista de Medios y Educación 47: 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsells, Maria Àngels, Aida Urrea-Monclús, Ainoa Mateos, Alícia Borrego, Arnau Erta-Majó, Anna Massons-Ribas, Eduard Vaquero, Laura Fernández-Rodrigo, Betlem Armengol, M. Alba Forné, and et al. 2023. TRIÁNGULO P+. El Triángulo de la Parentalidad Positiva Como Recurso para la Metodología Individual y Familiar. En M.À. Balsells (dir.), Colección FRAME+P: Balsells M.À. (dir). El Trabajo con la Familia de Origen en el Sistema de Protección a la Infancia y la Adolescencia, Vol. 4. Available online: https://repositori.udl.cat/handle/10459.1/464447 (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Balsells, Maria Àngels, Aida Urrea-Monclús, Carmen Ponce, Eduard Vaquero, and Alicia Navajas. 2019. Claves de acción socioeducativa para promover la participación de las familias en procesos de acogimiento. [Socio-educative key actions to promote family participation in foster care processes]. Educación XX1 22: 401–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsells, Maria Àngels, Crescencia Pastor, Pere Amorós, Núria Fuentes-Peláez, Mari Cruz Molina, Ainoa Mateos, Eduard Vaquero, Carmen Ponce, Maria Isabel Mateo, Belén Parra, and et al. 2015. Caminar en Familia: Programa de Competencias Parentales Durante el Acogimiento y la Reunificación Familiar. Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Centro de Publicaciones. Available online: http://www.msssi.gob.es/ssi/familiasInfancia/ayudas/docs2013-14/docs2016/CaminarenFamilia.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Bouma, Helen, Mónica López-López, Erik J. Knorth, and Hans Grietens. 2018. Meaningful participation for children in the Dutch child protection system: A critical analysis of relevant provisions in policy documents. Child Abuse and Neglect 82: 279–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberland, Claire, Carl Lacharité, Marie-È. Clément, and Danielle Lessard. 2014. Predictors of Development of Vulnerable Children Receiving Child Welfare Services. Journal of Child and Family Studies 24: 2975–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberland, Claire, Marie-È Clément, Carl Lacharité, and Véronique Bouchard. 2012. Quality of Exposure to the AIDES Social Innovation and Developmental Outcomes Innovation and Developmental Outcomes of the Children and Parents. Keeping Children Safe in an Uncertain Word: Learning from Evidence and Practice. Available online: https://initiativeaides.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/qualityofexposureoftheaides.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Consejo de Europa. 2006. Recomendación Rec (2006) del Comité de Ministros a los Estados Miembros Sobre Políticas de Apoyo al Ejercicio Positivo de la Parentalidad. (Adoptada por el Comité de Ministros el 13 de Diciembre de 2006 en la 983.ª Reunión de los Delegados de los Ministros). Available online: http://rm.coe.int/native/09000016805d6dda (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Daly, Mary, Rachel Bray, Zlata Bruckauf, Jasmina Byrne, Alice Margaria, Ninoslava Pecnik, and Maureen Samms-Vaughan. 2015. Family and Parenting Support: Policy and Provision in a Global Context. Innocenti Insight. Florence: UNICEF Office of Research. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, Emma. 2017. Saying it like it is? Power, participation and research involving young people. Social Inclusion 5: 228–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health. 2000. Framework for the assessment of children in need and their families. Child Care in Practice 6: 174–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, Joanne R. 2018. Revolutionizin Participation in Child Protection Proceedings. Ph.D. thesis, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, Jo, Jade Ward, and Sarah Blower. 2019. “They sat and actually listened to what we think about the care system”: The use of participation, consultation, peer research and co-production to raise the voices of young people in and leaving care in England. Child Care in Practice 25: 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erta-Majó, Arnau, and Eduard Vaquero. 2023. La Educación transmedia en el ámbito no formal: Una revisión sistemática. Revista Fuentes 25: 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flewitt, Rosie, Phil Jones, John Potter, Myrrh Domingo, Paul Collins, Ellie Munday, and Karen Stenning. 2018. ‘I enjoyed it because … you could do whatever you wanted and be creative’: Three principles for participatory research and pedagogy. International Journal of Research and Method in Education 41: 372–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, Rebecca, Suzanne F. Jackson, Jessica Maher, and Catherine Moravac. 2014. I was here: Young mothers who have experienced homelessness use photovoice and participatory qualitative analysis to demonstrate strengths and assets. Global Health Promotion 22: 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugard, Andrew J. B., and Henry W. W. Potts. 2015. Supporting thinking on sample sizes for thematic analyses: A quantitative tool. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 18: 669–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, Graham. 2012. El Análisis de Datos Cualitativos en Investigación Cualitativa. Ediciones Morata. Available online: https://dpp2016blog.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/graham-gibbs-el-anc3a1lisis-de-datos-cualitativos-en-investigacic3b3n-cualitativa.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Jaque, Maritza E., Ailin X. Sandoval, and Marina C. Alarcón. 2018. Familias en situaciones de crisis crónicas: Características e intervención. Cuadernos de Trabajo Social 32: 165–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, Henry. 2006. Where Old and New Media Collide; NYU Press. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qffwr (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Kenny, Neil, Alison Doyle, and Finbar Horgan. 2023. Transformative Inclusion: Differentiating Qualitative Research Methods to Support Participation for Individuals With Complex Communication or Cognitive Profiles. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 22: 160940692211469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacharité, Carl. 2017. Programme d’aide Personnelle, Familiale et Communautaire: PAPFC2. Program Guide, 2nd ed. CEIDEF/UQTR: Available online: https://oraprdnt.uqtr.uquebec.ca/pls/public/docs/GSC4103/F_1176562899_Guide_PAPFC2_anglais_170322.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Lemay, Louise. 2013. Pratiques évaluatives et structuration du rapport parent-intervenant dans le champ du travail social en contexte de protection de la jeunesse: Enjeux, défis et repères pour l’action. In Le Travail Social, Théories, Méthodologies et Pratiques. Edited by Elizabeth Harper and Herni Dorvil. Québec: Presses de l’Universitaires du Québec, pp. 313–38. [Google Scholar]

- Levac, Leah. 2013. ‘Is this for real?’ participatory research, intersectionality, and the development of leader and collective efficacy with young mothers. Action Research 11: 423–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léveillé, Sophie, and Claire Chamberland. 2010. Toward a general model for child welfare and protection services: A meta-evaluation of international experiences regarding the adoption of the Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and Their Families (FACNF). Children and Youth Services Review 32: 929–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietz, Cynthia A. 2013. Family Resilience in the Context of High-Risk Situations. In Handbook of Family Resilience. New York: Springer, pp. 153–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, Michael A., Nicole E. Brandt, Kimberly D. Becker, Bethany R. Lee, Richard P. Barth, Eric L. Daleiden, and Bruce F. Chorpita. 2014. Identifying the Common Elements of Treatment Engagement Interventions in Children’s Mental Health Services. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 17: 283–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, Janika, Teemu Rantanen, and Temu Toikko. 2024. Narratives of experts by experience: A journey from criminal to expert. Journal of Social Work 24: 415–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundy, Laura. 2007. Voice is not enough: Conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. British Education Research Journal 33: 927–42. [Google Scholar]

- Majee, Wilson, Nameri Conteh, Joachim Jacobs, and Lisa Wegner. 2022. Needs ranking: A qualitative study using a participatory approach. Health & Social Care in the Community 30: E5095–E5104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, Ainoa, Eduard Vaquero, Aida Urrea-Monclús, and Belen Parra. 2020. Contar con la infancia en situación de riesgo en los procesos de investigación: Pasos hacia la coproducción. Sociedad e Infancias 4: 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, Ainoa, Maria Àngels Balsells, Núria Fuentes-Peláez, and Maria Jose Rodrigo. 2021. Listening to children: Evaluation of a positive parenting programme through art-based research. Children & Society 35: 311–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, Paola, Sara Serbati, and Marco Ius. 2011. P.I.P.P.I. Programma di Intervento Per la Prevenzione dell’Istituzionalizzazione. Guida Operativa. Padova: Università degli Studi di Padova, Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali. [Google Scholar]

- Milani, Paola, Sara Serbati, Marco Ius, Diego Di Masi, and Ombretta Zanon. 2013. Programma di Intervento per la Prevenzione dell’Istituzionalizzazione. Padova: Università degli Studi di Padova, Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Monique B., Leon Kuczynski, Carolyn Y. Tubbs, and Cristopher Ross. 2010. We care about care: Advice by children in care for children in care, foster parents and child welfare workers about the transition into foster care. Child & Family Social Work 15: 176–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterling, Kathy L., and Meekyung Han. 2011. Reunification outcomes among Mexican immigrant families in the child welfare system. Children and Youth Services Review 33: 1658–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, Melissa Shamini P. 2020. Multimodal Engagement through a Transmedia Storytelling Project for Undergraduate Students. GEMA Online® Journal of Language Studies 20: 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Padilla, Javier, Susana Menéndez Álvarez-Dardet, and Maria Victoria Hidalgo. 2014. Estrés parental, estrategias de afrontamiento y evaluación del riesgo en madres de familias en riesgo usuarias de los Servicios Sociales. Psychosocial Intervention 23: 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rapley, Tim. 2014. Los Análisis de la Conversación, del Discurso y de Documentos en Investigación Cualitativa. Madrid: Ediciones Morata. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo, Maria Jose, Juan Carlos Martín-Quintana, Eduardo Cabrera, and Maria Luisa Máiquez. 2009. Las competencias parentales en contextos de riesgo psicosocial. Psychosocial Intervention 18: 113–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, Maria Jose, Maria Luisa Máiquez, and Juan Carlos Martín-Quintana. 2010. La Educación Parental Como Recurso Psicoeducativo para Promover la Parentalidad Positiva. Madrid: Federación Española de Municipios y Provincias (FEMP). Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/en/ssi/familiasInfancia/parentalidadPos2010/docs/folletoParentalidad2.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Rodrigo, Maria Jose, Maria Luisa Máiquez, and Juan Carlos Martín-Quintana. 2011. Buenas Prácticas Profesionales para el Apoyo de la Parentalidad Positiva. Madrid: Federación Española de Municipios y Provincias (FEMP). Available online: https://www.dsca.gob.es/sites/default/files/derechos-sociales/BuenasPractParentalidadPositiva_0.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Sonsteng-Person, Melanie, Victoria Copeland, Javier García-Pérez, Darlene Abrams, Laura Liévano-Karim, Rachel Marquardt, Brittany Jarman, Jesse Van Leeuwen, Sara Taitingfong, Riahannon Valdez, and et al. 2023. “What i would do to take away your pain”: A photovoice project conducted by mothers of children with medical complexity. Qualitative Health Research 33: 204–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudt, Marlys. 2007. Treatment Engagement with Caregivers of At-risk Children: Gaps in Research and Conceptualization. Journal of Child and Family Studies 16: 183–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeton, Michelle, Maria Lohan, Laura Lundy, and Carmel Kelly. 2019. Young people’s sexual readiness: Insights gained from comparing a researchers’ and youth advisory group’s interpretation. Culture, Health and Sexuality 22: 987–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tisdall, E. Kay M. 2017. Conceptualising children and young people’s participation: Examining vulnerability, social accountability and co-production. The Internacional Journal of Human Rights 21: 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toros, Karmen, Diana Maria DiNitto, and Anne Tiko. 2018. Family engagement in the child welfare system: A scoping review. Children and Youth Services Review 88: 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrea-Monclús, Aida, M. Àngels Balsells, Maria Alba Forné Samitier, and Laura Fernández-Rodrigo. 2023. Adolescències: Reptes, Propostes i Orientacionsper a les Polítiques Municipal. Barcelona: Diputació de Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés, Antonia, and Borja Castro-Serrano. 2017. Experiencias clave de aprendizaje de adultos chilenos en situación de vulnerabilidad: El reconocimiento como motivo de aprendizaje. Estudios Pedagógicos (Valdivia) 43: 325–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valles, Miguel S. 2009. Técnicas Cualitativas de Investigación Social. Reflexión Metodológica y Práctica Profesional. Madrid: Síntesis. [Google Scholar]

- Vaquero, Eduard, Maria Àngels Balsells, Laura Fernández-Rodrigo, Núria Fuentes-Peláez, and Ainoa Mateos. 2022. La Educación Parental Desde un Enfoque Interseccional: Perspectiva de Género e Interseccionalidad. Formación Online Continuada. Aprender Juntos, Crecer en Familia. Available online: https://fundacionlacaixa.org/documents/234043/559336/educacion-parental-desde-enfoque-interseccional.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Vizoso-Gómez, Carmen Maria. 2024. Maltrato infantil y burnout parental. Revisión sistemática. Pedagogia Social Revista Interuniversitaria 44: 177–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, Penny, Mary Ryan, and Rose McCabe. 2022. Participating in Research: Experiences of People Presenting to the Emergency Department With Self-Harm or Suicidality. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 21: 160940692211102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Jing. 2019. Participatory action research: Promoting partnership between a social work team and mothers of hemophiliac children. Action Research 18: 102–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatchmenoff, Diane K. 2005. Measuring Client Engagement From the Client’s Perspective in Nonvoluntary Child Protective Services. Research on Social Work Practice 15: 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).