The Role of Political Actors’ Preference Variation in the Decision-Making Process of the European Union

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Role of Interest Groups, Member State Preferences, and Domestic Politics in the EU Decision-Making Process

2.2. The Interaction Between Interest Groups and the Member States’ Preferences

2.3. Connecting the Input, Throughput, and Output of Decision-Making Processes

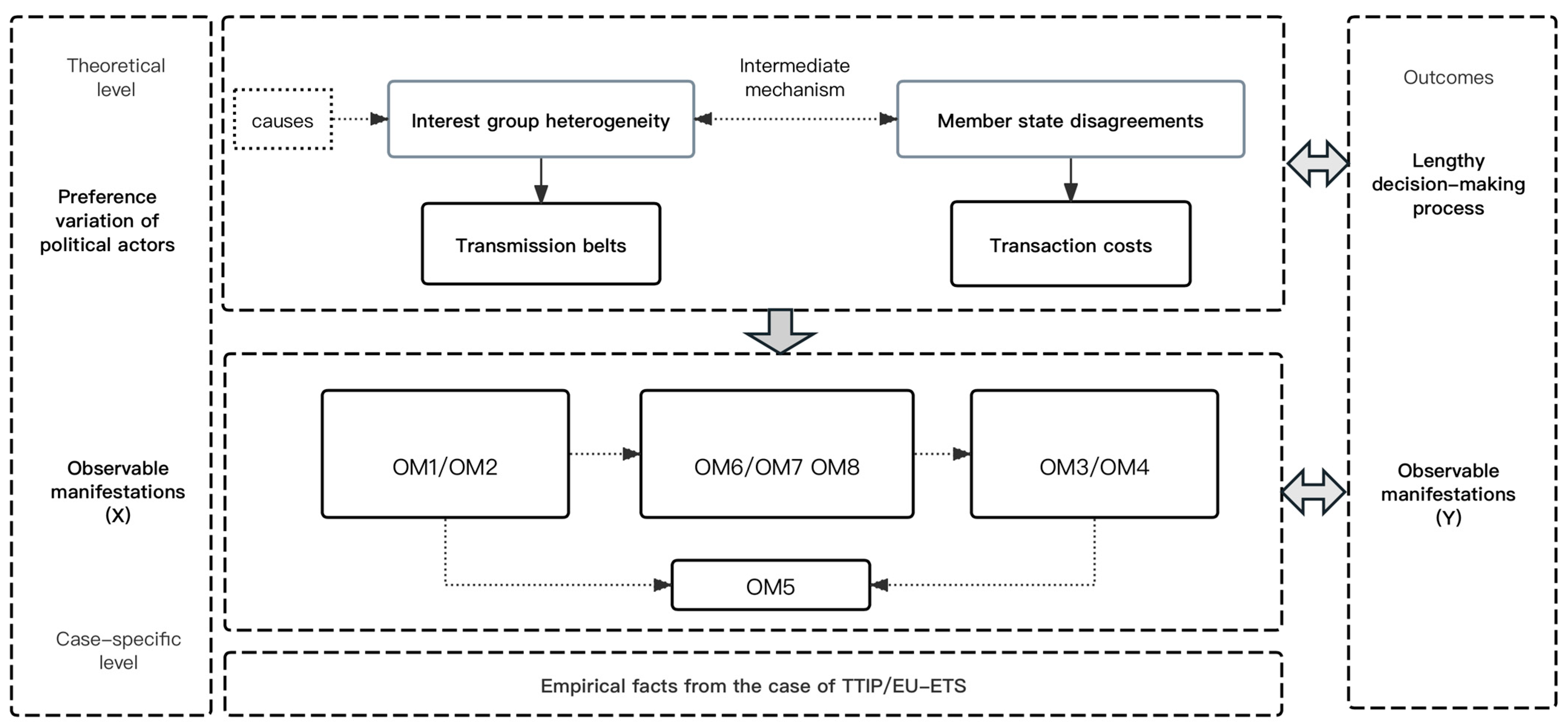

3. Causal Mechanism

3.1. Causal Mechanism Behind the Length of the Decision-Making Process

3.2. Cause: Transmission Belts from Interest Group Heterogeneity

3.3. Intermediate Mechanism: Transaction Costs of Member States’ Disagreement

3.4. Negotiation Outcomes: A Lengthy Decision-Making Process

4. Research Design

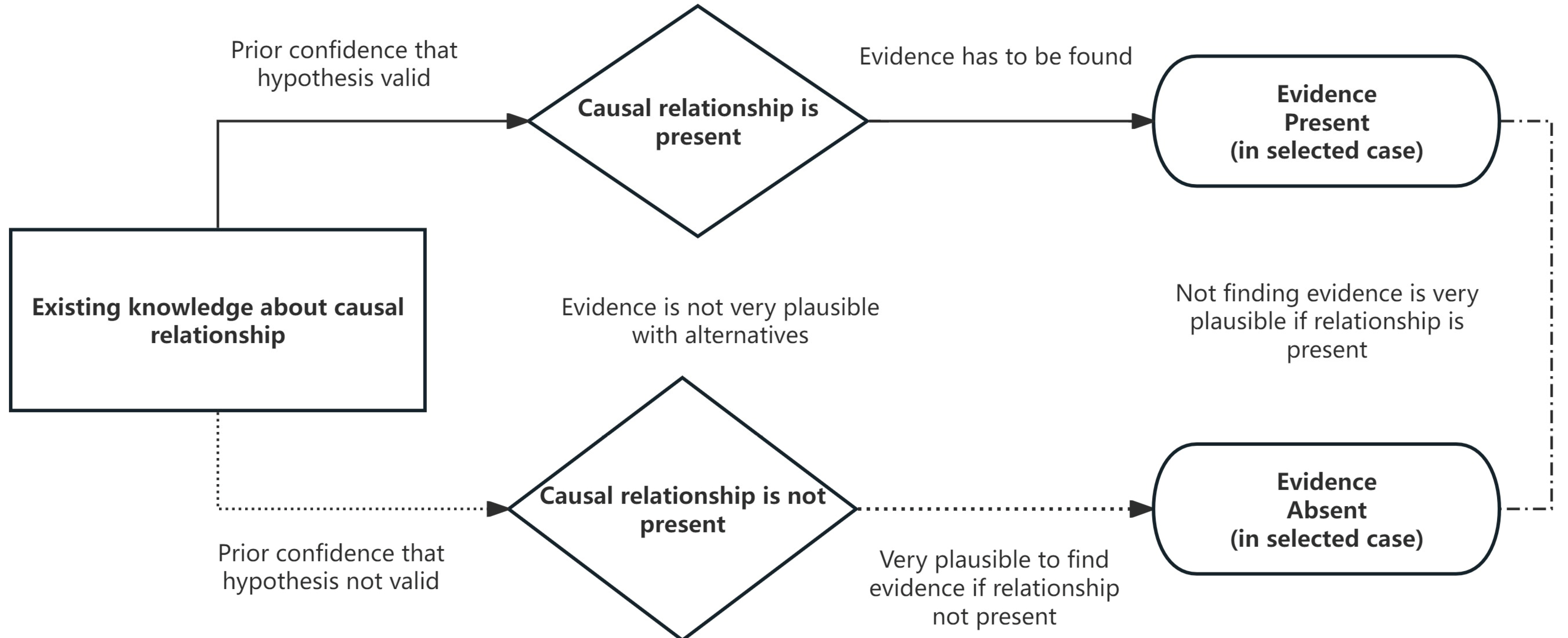

4.1. Methodological Approach: Process Tracing the Causal Mechanism

4.2. Case Selection and Sampling

- Several rounds of negotiation took place before the formal legislation was adopted;

- Different interest groups and member states were involved in the legislative negotiations;

- Negotiations became stuck, without withdrawal or formal rejection;

- The legislative proposal featured was complicated, multifactorial, and had specific contextual issues (Winnwa 2018).

4.3. Certainty, Uniqueness, and Hypothesis Testing

4.4. Document Data

4.5. Interview Data

5. Results

5.1. Evaluation of the Evidence on the TTIP

“There are divergent views within our various departments and ministries. Our [Germany] economy minister Sigmar Gabriel has previously stated that the EU-US trade talks have failed because the agreement on the table was unacceptable under the unequal conditions imposed by the US-led discussions, which more favored the US over the EU”(respondent#4).

“We [France] believed there was no political support in Paris for the TTIP negotiations because they sought a pure, straightforward, and definite halt in order to continue subsequent conversations on a reasonable ground”(respondent#11).

“Our economic organizations have always demanded that the negotiations should be halted, and the entire process restarted. However, we as a government [Austrian] strive to function as a neutral responder and to ensure that our positions are not dominated by certain interest groups”(respondent#2).

“We (the Council) have consistently urged member states and the European Commission to coordinate their efforts to explain the benefits of the agreement and strengthen interaction with national parliaments and civil society organizations. Finally, the Council of Foreign Ministers endorsed the working group’s provisional agreements reached following a lengthy discussion of the TTIP negotiations”(respondent#2).

“We (European Commission) recognized that successful trade legislation and better implementation are a joint responsibility of the Commission, the Parliament, and the Council”(respondent#1).

“The TTIP negotiations should achieve an ambitious and balanced agreement that benefits all member states equally. It would neither accept an arrangement that would lower standards, nor would it consent to a proposal that would jeopardize its ability to govern public policy objectives”(respondent#10).

“The legislative procedure that we shaped was the European Parliament’s democratic responsibility. As a result, our MEPs approved (447 votes in favor, 229 votes against, and 30 abstentions) the inclusion of a new public legal mechanism for resolving disputes between investors and member states”(respondent#3).

5.2. Evaluation of the Evidence on the EU ETS

“We reach a quick consensus in 80% of situations, but 20% of the policy issues we address are challenging or extremely difficult, requiring more time and effort”(respondent#21).

“Stakeholders from the industry expressed concerns about various components of the system. They argued that the proposed new restricted one-off flexibility with the EU ETS for nine member states with a maximum allocation of 100 million ETS credits should be scrapped”(respondent#18).

“We [the Netherlands] insisted on complying that each member state’s designated administrative or judicial authorities have the authority to impose the penalties outlined in Article 16 (3) in order to ensure conformity with the provisions. Member states’ representatives play a critical role in ensuring consensus among members by considering all perspectives and ensuring that all members take a homogeneous position”(respondent#5).

“We [the Czech Republic] have urged that the European Commission conduct an in-depth examination of the EU ETS’s operation and efficacy while simultaneously embarking on a fierce debate about alternative strategies for greenhouse gas emission reduction. As a result, the common position incorporated 23 of the 73 amendments proposed by the European Parliament in the first reading”(respondent#7).

“(…) Ok, here is the information that I have learned in this case. The common position contains five amendments that the European Commission did not adopt in its modified proposal. As the accession discussions do not provide for it, agreements must be reached with the applicant nations. The Commission has agreed to this amendment in principle by replacing ‘third parties’ with ‘Parties specified in Annex B of the Kyoto Protocol that have ratified that Protocol’. The amendment section referring to agreements with applicant countries was rejected, as emissions trading was expected to occur in applicant countries because of the scheme’s implementation. The Common Position acknowledges that links should be established only with Kyoto Protocol Annex B Parties and goes further in that direction by stating that ‘agreements’ should be concluded with third countries listed in Annex B to the Kyoto Protocol”(Respondent#14).

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Observable Manifestations | Certainty, Uniqueness, and Hypothesis Tests |

|---|---|

| C1. OM1. Interest groups hold a negative attitude or opposing opinions about a policy which is to be adopted via consultations; they require the legislative proposals to be adjusted. | High certainty: evidence needs to be found in the consultation documents to prove the presence of interest groups. Low uniqueness: the presence of negative opinions from interest groups can be explained by conflict constellation in EU institutions. The evidence was found: the hypothesis passes the hook test. |

| OM2. Interest groups work hard to reinforce the function of interest groups’ transmission belts. | Low certainty: there may be other factors affecting the decision-making processes behind the interest groups’ transmission belts. High uniqueness: if found, the evidence cannot be explained by alternative hypotheses. The evidence was found: the hypothesis passes the smoking gun test. |

| C2. OM3. Different member states take opposing positions in different Council meetings, increasing the transaction costs required to reach a deal. | High certainty: evidence of increased transaction costs needs to be found to prove the presence of member states’ opposing positions. High uniqueness: if found, the evidence cannot be explained by alternative hypotheses. The evidence was found: the hypothesis passes the doubly decisive test. |

| OM4. Member states must debate, in the Council, the politically sensitive issues that remain unresolved, before finally adopting Coreper I/II Part 2 (B items) resolution after discussion. | High certainty: evidence of COREPER II/ B items needs to be found to prove their presence. High uniqueness: if found, the evidence cannot be explained by alternative hypotheses. The evidence was found: the hypothesis passes the doubly decisive test. |

| OM5. On high-profile issues, conflicts arise between the Commission and national parliaments. | Low certainty: there may be other evidence of decision-making delays besides conflicts between the Commission and national parliaments. Low uniqueness: the presence of conflicts on high-profile issues can be explained by alternative hypotheses. The evidence was found: the hypothesis passes the straw-in-the-wind test. |

| C3. OM6. Member states are most responsive to the demands of stakeholders from their own territories. | High certainty: evidence of member states’ representatives interacting with interest groups needs to be found to prove the presence of this interaction. High uniqueness: if found, the evidence cannot be explained by alternative hypotheses. The evidence was found: the hypothesis passes the doubly decisive test. |

| OM7. Interest groups will be likely to have a negative effect as transmission belts if their members have negative opinions and member states have heterogeneous preferences for EU legislative proposals, which may lead to prolonged legislative decision-making. | High certainty: evidence of the combination of heterogeneous position-taking by interest groups and member states needs to be found to prove its presence. High uniqueness: if found, the evidence cannot be explained by alternative hypotheses. The evidence was found: the hypothesis passes the doubly decisive test. |

| Y. OM8. Interest groups’ demands influence the preferences of member states and the strategies of EU legislators | Low certainty: there may be other evidence of interest groups’ influence besides the debates of member states in the Council. High uniqueness: if found, the evidence cannot be explained by alternative hypotheses. The evidence was found: the hypothesis passes the smoking gun test. |

| OM9. The heterogeneous opinions of interest groups can shape decision-making outcomes by impacting the negotiation among member states in the Council | High certainty: evidence of the heterogeneous opinions of interest groups in the consultation documents need to be found to prove its presence. High uniqueness: if found, the evidence cannot be explained by alternative hypotheses. The evidence was found: the hypothesis passes the doubly decisive test. |

| OM10. Interview and observation data confirm that the interaction effects lead to EU decision-making delay | High certainty: evidence of withdrawal or formal rejection in the specific negotiation needs to be found to prove that the interaction effects lead to EU decision-making delays. High uniqueness: if found, the evidence cannot be explained by alternative hypotheses. The evidence was found: the hypothesis passes the doubly decisive test. |

| Respondent | Date | Affiliation | Position and Political Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent#1 | 18 November 2020 | European Commission Official | Trade Commissioner Trade Policy Counselor |

| Respondent#2 | 14 December 2020 | The Council Official | Council, Principal Administrator/Head of Sector |

| Respondent#3 | 11 January 2021 | European Parliament Official | Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Germany—Social Democratic Party of Germany |

| Respondent#4 | 16 February 2021 | Representative official of Germany | Permanent representation, Germany Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance |

| Respondent#5 | 3 March 2021 | Representative official of the Netherlands | Permanent representation, Netherlands Chair of the Bureau Independence/Democracy Group |

| Respondent#6 | 15 March 2021 | Representative official of Poland | Permanent representation, Poland Group of the European People’s Party (Christian Democrats) |

| Respondent#7 | 24 March 2021 | Representative official of Czech Republic | Perm Rep, Czech Presidency President of the Senate |

| Respondent#8 | 24 January 2022 | Representative official of Slovenia | Minister for Digital Transformation, Slovenia |

| Respondent#9 | 24 January 2022 | European Commission Official | Common Secretariat of the Conference on the Future of Europe; European Commission |

| Respondent#10 | 24 January 2022 | European Parliament Official | Deputy Head of Office of EP Secretary General, with responsibility for Constitutional and Institutional Affairs, and former MEP |

| Respondent#11 | 24 January 2022 | European Parliament Official | Member of EP Committee on Internal Market and Consumer Protection and Special Committee |

| Respondent#12 | 24 January 2022 | European Commission Official | Former Secretary General, European Commission; former EU Ambassador to the US; former COO, European External Action Service (EEAS) |

| Respondent#13 | 25 January 2022 | Expert from think tank | Associate Senior Research Fellow, Energy, Resources and Climate Change Unit (CEPS) |

| Respondent#14 | 25 January 2022 | European Commission Official | Cabinet of European Commission VP Frans Timmermans |

| Respondent#15 | 25 January 2022 | Expert from think tank | Visiting Scholar, Carnegie Europe |

| Respondent#16 | 25 January 2022 | European Parliament Official | MEP, Member of EP Foreign Affairs (AFET) Committee and Rapporteur on ‘The future of EU-US relations’ report |

| Respondent#17 | 25 January 2022 | Expert from think tank | Adjunct Professor, Sciences Po, Paris; Non-Resident Senior Fellow, German Marshall Fund (GMF); former member of the Policy Planning Staff, US Department of State |

| Respondent#18 | 25 January 2022 | Expert from think tank | Director, GMF Brussels |

| Respondent#19 | 25 January 2022 | European Parliament Official | MEP, Vice-President of the European Parliament |

| Respondent#20 | 25 January 2022 | Expert from think tank | Senior Policy Advisor, Policy Planning Unit, Office of the Secretary General, NATO |

| Respondent#21 | 25 January 2022 | Expert from think tank | Head of Climate Action Tracking Service (CART), European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS) |

| Date | Key Events |

|---|---|

| 14 June 2013 Initial legislation | EU directives for the negotiations for a Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the EU and the US unanimously adopted by the Council on 14 June 2013 |

| February 2013 | EU-commissioned ‘ad hoc high-level expert group’ published a paper, highlighting the need for a free-trade area between the European Union and the United States (taken up by President Obama and President of the Commission Barroso) |

| 23 May 2013 | European Parliament voted on a resolution for the exclusion of culture and audio-visual services from the negotiation mandate. |

| 14 June 2013 | Council agrees on the exclusion of audio-visual services from the mandate in its directives for the negotiation of the TTIP |

| 8–11 July 2013 | 1st round of negotiations (Washington DC) |

| 11–15 November 2013 | 2nd round of negotiations (Brussels) |

| 16–20 December 2013 | 3rd round of negotiations (Washington DC) |

| January 2014 | launch of the EU advisory group |

| 10–14 March 2014 | 4th round of negotiations (Brussels) |

| 19–23 May 2014 | 5th round of negotiations (Arlington, Virginia) |

| July 2014 | publication of the EU position papers |

| 14–18 July 2014 | 6th round of negotiations (Brussels) |

| October 2014 | publication of the EU negotiations mandate |

| 29 September 2014 | 7th round of negotiations (Chevy Chase, Maryland) |

| November 2014 | Announcement by the EU Commission of further transparency and access to documents for MEPs and the Council |

| 2–6 February 2015 | 8th round of negotiations (Brussels) |

| 20–24 April 2015 | 9th round of negotiations (Washington DC) |

| 13–17 July 2015 | 10th round of negotiations (Brussels) |

| 19–23 October 2015 | 11th round of negotiations (Miami) |

| 22–26 February 2016 | 12th round of negotiations (Brussels) |

| 24 April 2016 | US President Obama and German Chancellor Merkel commit to completing talks on the TTIP before his term ends in January |

| 25–29 April 2016 | 13th round of negotiations (New York) |

| 2 May 2016 | Greenpeace leaks |

| 24 June 2016 | Britain votes to leave the European Union, loses part in TTIP talks |

| 13–15 July 2018 | 14th round of negotiations (Brussels) |

| 18 January 2019 Final legislation | Recommendation for a final Council decision authorizing the opening of negotiations of an agreement with the United States of America on the elimination of tariffs for industrial goods COM/2019/16 |

| Date | Formal Legislative Procedure |

|---|---|

| 14 June 2013 | EU directives for the negotiations of a Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the EU and the US unanimously adopted by the Council |

| 9 October 2014 | EU directives for the negotiations of a Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the EU and the US declassified and made public by the Council |

| 8 July 2015 | European Parliament resolution containing the European Parliament’s recommendations to the European Commission on the negotiations for the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) (2014/2228(INI)) |

| 24 April 2016 | Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation) (Text with EEA relevance) |

| 27 April 2016 | Directive (EU) 2016/680 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data by competent authorities for the purposes of the prevention, investigation, detection, or prosecution of criminal offenses or the execution of criminal penalties, and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Council Framework Decision 2008/977/JHA |

| 25 July 2018 | Directives for the negotiations with the United States of America for an agreement on the elimination of tariffs for industrial goods |

| 9 April 2019 | Council decision authorizing the opening of negotiations with the United States of America for an agreement on conformity assessment |

| Directives for negotiations with the United States of America for an agreement on conformity assessment | |

| 18 January 2019 | European Commission adopted proposals for negotiating directives for its trade talks with the United States: one on conformity assessment and one on the elimination of tariffs for industrial goods (conformity assessment AND industrial tariff elimination) |

| Date | Formal Legislative Procedure |

|---|---|

| 23 October 2001 | Legislative proposal published |

| 28 November 2001 | Committee referral announced in Parliament, 1st reading/single reading |

| 12 December 2001 | 1st round of debate in Council |

| 4 March 2002 | 2nd round of debate in Council |

| 25 June 2002 | 3rd round of debate in Council |

| 10 September 2002 | Vote in committee, 1st reading/single reading |

| 10 September 2002 | Committee report tabled for plenary, 1st reading/single reading |

| 10 October 2002 | 1st round of debate in Parliament. Decision by Parliament, 1st reading/single reading |

| 17 October 2002 | 4th round of debate in Council |

| 27 November 2002 | Modified legislative proposal published |

| 18 March 2003 | Council position published |

| 27 March 2003 | Committee referral announced in Parliament, 2nd reading |

| 11 June 2003 | Vote in committee, 2nd reading. Committee recommendation tabled for plenary, 2nd reading |

| 1 July 2003 | 2nd round of debate in Parliament |

| 2 July 2003 | Decision by Parliament, 2nd reading |

| 22 July 2003 | Act approved by Council, 2nd reading, final act signed |

| 13 October 2003 | End of procedure in Parliament |

| 25 October 2003 | Final act published in Official Journal |

| Final legislation | Directive 2003/87/EC establishing a system for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading system within the EU |

Appendix B. Interview Questions

- Case 1: Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), online interview (Zoom/Teams) (26 questions)

- Role of respondent in TTIP legislation

- What is the role of your institution in TTIP negotiation?

- What are your main tasks and duty in the process of TTIP negotiation?

- Please describe the process of negotiation in the Council

- Whether there were any disagreements on the proposals among member states or groups of member states?

- If was, which member state and why they opposed? On the whole proposal or parts of it? Which parts?

- Did the position of member states strongly diverge?

- Did Germany and France play a particular role?

- What was the role of Germany, France and Austria? Why did they make such strong statements? Did they also defend them in the Council meeting? How did the other member states react?

- Has the interest groups’ negative opinions on TTIP negotiations affected the member states’ decision?

- Has the member states’ position affected the Commission’s decision?

- Role of the different Council presidencies

- Did the German presidency play a particular role?

- How was German position?

- How were the other presidencies?

- Individual opinions

- What do you think will be the main factors that affected the position-taking on this proposal?

- Have you noticed that negotiators mention time invested in the Council meeting as a cost?

- What is the opinion of your institutions towards the TTIP negotiations and EU ETS directive?

- Do you think which type of political actors have exactly the preferred influence on the legislative process?

- Who do you think is the winner of the negotiations?

- What would you say has been the most successful strategy in the negotiations?

- The Council-European Commission interactions

- How much did the Council disagree with the initial Commission proposal?

- How much did the Council insist on changing the Commission proposal?

- Did the EP position matter to the Council? Did they discuss with stakeholders from the EP?

- Who coordinated the debate between the institutions?

- Conciliation of heterogeneous positions

- How were the disagreements solved?

- Who proposed a solution? What solution did they propose?

- Was there a compromises or deals?

- Whose opinions would be the most influential?

- Case 2: EU Emissions Trading System (EU-ETS) Directive, online interview (Zoom/Teams) (20 questions)

- General questions

- To what extent the interest groups’ opinions influence the member states’ positions on the directive?

- Why did this proposal delay?

- The European Commission

- What was the Commission’s position on this proposal?

- How did the Commission handle the negotiations?

- How did it react to the Council’s division? Did it interfere with the Council’s decision?

- Did the Commission consider changing its position?

- Did the Commission react to the Council not agreeing on a position?

- Is the Commission closer to the Parliament or the Council on this directive?

- The Council

- What are the main points of disagreement in the Council?

- Why is the Council so divided on this issue? Who opposed the proposal most in the Council? What are the arguments by the opposing member states?

- Which member states defend similar positions?

- Which role does Germany play in the negotiations? Did it change positions?

- How did the Czech Presidency approach the conflicts? Why did they fail to forge consensus?

- How did the other member states’ presidency approach the conflicts?

- Were there any further negotiations after the Council decided to withdrawal the Parliament’s amendments?

- The Council and The European Parliament

- How did the Council judge the EP’s position? (Accept? Reject? Withdrawal?)

- How did the Council receive the EP’s criticism for not taking a position?

- Do you know any of division inside of the Parliament?

- What were the main points of disagreement?

- Which amendments were particularly problematic?

References

- Agence Europe. 2014. Opinion: US, EU Betraying Democratic Ideals by Refusing to Release TTIP Negotiations Texts. Brussels: Agence Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Agence Europe. 2015a. European Parliament Adopts its Recommendations for TTIP Negotiations. Brussels: Agence Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Agence Europe. 2015b. WTO Format to Eventually Replace TPP. Stockholm: TTIP–Sweden’s National Trade Board. [Google Scholar]

- Agence Europe. 2016. Germany and France Clash Over Transatlantic Trade Deal as Opposition Grows. Brussels: Agence Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Albareda, Adrià, and Caelesta Braun. 2019. Organizing transmission belts: The effect of organizational design on interest group access to EU policy-making. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 57: 468–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, Derek. 2017. Process-tracing methods in social science. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beach, Derek, and Rasmus Brun Pedersen. 2013. Process-Tracing Methods: Foundations and Guidelines. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berkhout, Joost, Marcel Hanegraaff, and Caelesta Braun. 2017. Is the EU Different? Comparing the Diversity of National and EU-Level Systems of Interest Organisations. West European Politics 40: 1109–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, Edward, and Pierpaolo Settembri. 2008. Legislative output after enlargement: Similar number, shifting nature. The Institutions of the Enlarged European Union 10: 183. [Google Scholar]

- Beyers, Jan, and Iskander De Bruycker. 2018. Lobbying makes (strange) bedfellows: Explaining the formation and composition of lobbying coalitions in EU legislative politics. Political Studies 66: 959–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyers, Jan, and Guido Dierickx. 1998. The Working Groups of the Council of the European Union: Supranational or Intergovernmental Negotiations? JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 36: 289–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binderkrantz, Anne Skorkjær. 2009. Membership recruitment and internal democracy in interest groups: Do group–membership relations vary between group types? West European Politics 32: 657–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunea, Adriana, Raimondas Ibenskas, and Florian Weiler. 2022. Interest group networks in the European Union. European Journal of Political Research 61: 718–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coen, David, Alexander Katsaitis, and Matia Vannoni. 2024. Lobbying in the European Union: Multi-venue and multi-actor strategies in the European Union. In Handbook on Lobbying and Public Policy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 271–85. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, David. 2011. Understanding Process Tracing. PS: Political Science and Politics 44: 823–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, Rory, and Robert Thomson. 2016. Bicameralism, nationality and party cohesion in the European Parliament. Party Politics 22: 773–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Medeiros Albrecht, Macedo. 2023. Bureaucrats, interest groups and policymaking: A comprehensive overview from the turn of the century. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 10: 565. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, Robert A. 2005. Who Governs?: Democracy and Power in an American City. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Ruiter, Rik, and Rens Vliegenthart. 2018. Understanding media attention paid to negotiations on EU legislative acts: A cross-national study of the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. Comparative European Politics 16: 649–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wilde, Pieter. 2007. Politicisation of European integration: Bringing the process into focus. In University of Oslo ARENA Working Paper. Oslo: University of Oslo. [Google Scholar]

- De Wilde, Pieter, and Michael Zürn. 2012. Can the politicization of European integration be reversed? JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 50: 137–53. [Google Scholar]

- De Wilde, Pieter, Anna Leupold, and Henning Schmidtke. 2018. The Differentiated Politicisation of European Governance. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dionigi, Maja Kluger, and Anne Rasmussen. 2019. The Ordinary Legislative Procedure. Oxford: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. [Google Scholar]

- Dür, Andreas, and Gemma Mateo. 2012. Who lobbies the European Union? National interest groups in a multilevel polity. Journal of European Public Policy 19: 969–87. [Google Scholar]

- Dür, Andreas, Patrick Bernhagen, and David Marshall. 2015. Interest group success in the European Union: When (and why) does business lose? Comparative Political Studies 48: 951–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2019. Call for Proposals for Regulatory Cooperation Activities with Regard to the Regulation 1049/2001 and in Accordance with Regulation (EC) No 2018/1725. 29 April 2019. Brussels: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Flöthe, Linda. 2020. Representation through information? When and why interest groups inform policymakers about public preferences. Journal of European Public Policy 27: 528–46. [Google Scholar]

- Flöthe, Linda, and Anne Rasmussen. 2019. Public voices in the heavenly chorus? Group type bias and opinion representation. Journal of European Public Policy 26: 824–42. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, Justin. 2017. Interest Representation in the European Union. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Haag, Maximilian, Steffen Hurka, and Constantin Kaplaner. 2024. Policy complexity and implementation performance in the European Union. In Regulation and Governance. Hoboken: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Richard L., and Alan V. Deardorff. 2006. Lobbying as legislative subsidy. American Political Science Review 100: 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häge, Frank M. 2011. The European Union policy-making dataset. European Union Politics 12: 455–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks. 2009. A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: From permissive consensus to constraining dissensus. British Journal of Political Science 39: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hurka, Steffen, and Maximilian Haag. 2020. Policy complexity and legislative duration in the European Union. European Union Politics 21: 87–108. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, Andrew, and Robert Thomson. 2019. The Responsiveness of Legislative Actors to Stakeholders Demands in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy 26: 676–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, Adrian, and Phillip Baker. 2015. What can causal process tracing offer to policy studies? A review of the literature. Policy Studies Journal 43: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, Brandy. 2014. Unraveling representative bureaucracy: A systematic analysis of the literature. Administration and Society 46: 395–421. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler-Koch, Beate. 2010. Civil Society and EU Democracy: ‘Astroturf’ Representation? Journal of European Public Policy 17: 100–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler-Koch, Beate, and Christine Quittkat. 2013. De-Mystification of Participatory Democracy: EU-Governance and Civil Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler-Koch, Beate, and Vanessa Buth. 2013. The Balancing Act of European Civil Society. In De-Mystification of Participatory Democracy: EU-Governance and Civil Society. Oxford: Oxford Academic, p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- Koop, Christel, Christine Reh, and Edoardo Bressanelli. 2022. Agenda-setting under pressure: Does domestic politics influence the European Commission? European Journal of Political Research 61: 46–66. [Google Scholar]

- Laloux, Thomas. 2020. Informal Negotiations in EU Legislative Decision-Making: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. European Political Science 19: 443–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Yuxuan. 2024. Influence of Different Stakeholders on the Duration of Legislative Decision-Making in the European Union. Interest Groups and Advocacy 13: 167–91. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney, James. 2012. The Logic of Process Tracing Tests in the Social Sciences. Sociological Methods and Research 41: 570–97. [Google Scholar]

- Michalowitz, Irina. 2004. Analysing structured paths of lobbying behaviour: Why discussing the involvement of ‘civil society’ does not solve the EU’s democratic deficit. Journal of European Integration 26: 145–73. [Google Scholar]

- Moravcsik, Andrew. 2013. The Choice for Europe: Social Purpose and State Power from Messina to Maastricht. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, Gary. 2023. Interest Groups and the Policy-Making Process. Politics in the Republic of Ireland. London: Routledge, pp. 312–40. [Google Scholar]

- Naurin, Daniel, and Anne Rasmussen, eds. 2011. Special Issue on Linking Inter-and Intra-institutional Change in the European Union. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Perarnaud, Clement, and Javier Arregui. 2022. Do Member States’ Permanent Representations Matter for Their Bargaining Success? Evidence from the EU Council of Ministers. Journal of European Public Policy 29: 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, Robert D. 1988. Diplomacy and Domestic Politics: The Logic of Two-Level Games. International Organization 42: 427–60. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, Anne, and Christine Reh. 2017. The consequences of concluding codecision early: Trilogues and intra-institutional bargaining success. In Legislative Codecision in the European Union. London: Routledge, pp. 66–84. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, Anne, and Dimiter Toshkov. 2013. The effect of stakeholder involvement on legislative duration: Consultation of external actors and legislative duration in the European Union. European Union Politics 14: 366–87. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, Maja Kluger. 2015. The Battle for Influence: The Politics of Business Lobbying in the European Parliament. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 53: 365–82. [Google Scholar]

- Riccucci, Norma M., Gregg G. Van Ryzin, and Karima Jackson. 2018. Representative bureaucracy, race, and policing: A survey experiment. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 28: 506–18. [Google Scholar]

- Rohlfing, Ingo. 2012. Case Studies and Causal Inference: An Integrative Framework. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Scharpf, Fritz W. 1999. Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic? Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scharpf, Fritz W. 2009. Legitimacy in the Multilevel European Polity. European Political Science Review 1: 173–204. [Google Scholar]

- Scharpf, Fritz W. 2018. Games Real Actors Play: Actor-Centered Institutionalism in Policy Research. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Vivien A. 2009. Re-Envisioning the European Union: Identity, Democracy, Economy. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 47: 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, Vivien A. 2013. Democracy and Legitimacy in the European Union Revisited: Input, Output and ‘Throughput’. Political Studies 61: 2–22. [Google Scholar]

- Stefano, Vettorazzi. 2022. Fit for 55: Revision of the EU Emissions Trading System; Belgium: EPRS European Parliamentary Research Service. Available online: https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/gnjg42 (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- The Christian Science Monitor. 2016. Why Transatlantic Trade Deal Faces Stiffening Wind from Europe. Boston: The Christian Science Monitor. [Google Scholar]

- Toshkov, Dimiter, Lowery David, and Carroll Brain. 2013. Timing is everything? Organized interests and the timing of legislative activity. Interest Groups and Advocacy 2: 48–70. [Google Scholar]

- Tömmel, Ingeborg. 2017. The European Union: What It Is and How It Works. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Truman, David B. 1971. The Governmental Process: Political Interests and Public Opinion. Institute of Governmental Studies. Berkeley: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Van Evera, Stephen. 2016. Guide to Methods for Students of Political Science. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- VOA News. 2016. Germans Rally Against Planned EU Trade Deals with US. Washington, DC: VOA News. [Google Scholar]

- Winnwa, Isabel. 2018. Staging Policy Fiascoes: Unveiling the EU’s Strategic Game with Policy-Making Failure. Doctoral dissertation, Otto-Friedrich-Universität Bamberg, Fakultät Sozial-und Wirtschaftswissenschaften, Bamberg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

| Cause | Transmission Belts from the Interest Groups’ Heterogeneity |

|---|---|

| OM 1 | Evidence of conflicting demands in interest groups’ divergent public statements |

| OM 2 | Lobbying efforts or position papers from key interest groups. |

| Intermediate Mechanism | Transaction Costs of Member States’ Disagreement |

|---|---|

| OM 3 | Evidence of divergent member state negotiation positions |

| OM 4 | High-profile policies and politically sensitive issues documented in Council records |

| OM 5 | Official documents, public statements, or negotiation positions showing alignment with interest groups demands |

| Outcome | Institutional Complexity Results in a Lengthy Decision-Making Process |

|---|---|

| OM 6 | Evidence of procedural delays |

| OM 7 | Prolonged legislative timelines |

| OM 8 | Multiple rounds of negotiation |

| Cases | Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) | EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) |

|---|---|---|

| Policy type | Trade and investment agreement. | Market-based environmental regulation. |

| Stakeholder structure | Stakeholder consultations included business groups, civil society, and policymakers from both the EU and the US. | Consultations with industries, environmental groups, and member states, with regular revisions (e.g., Fit for 55). |

| Public engagement level |

|

|

| Institutional constraints |

|

|

| Similarities |

| |

| Types | Certainty | Uniqueness | Strength | Sufficiency for Inferring Causality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hoop test | High | Low | Stronger | Insufficient |

| Smoking gun test | Low | High | Stronger | Sufficient |

| Doubly decisive test | High | High | Strongest | Sufficient |

| Straw-in-the-wind test | Low | Low | Weakest | Insufficient * |

| Year | Germany | France |

|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 63% | 58% |

| 2015 | 55% | 52% |

| 2016 | 20% | 18% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lei, Y. The Role of Political Actors’ Preference Variation in the Decision-Making Process of the European Union. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14040193

Lei Y. The Role of Political Actors’ Preference Variation in the Decision-Making Process of the European Union. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(4):193. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14040193

Chicago/Turabian StyleLei, Yuxuan. 2025. "The Role of Political Actors’ Preference Variation in the Decision-Making Process of the European Union" Social Sciences 14, no. 4: 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14040193

APA StyleLei, Y. (2025). The Role of Political Actors’ Preference Variation in the Decision-Making Process of the European Union. Social Sciences, 14(4), 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14040193