1. Introduction

Social work education has historically positioned itself as a discipline committed to advancing social justice, human rights, and equity. Within this framework, the integration of gender perspectives emerges not only as an academic requirement but also as an ethical responsibility aligned with the profession’s mission of fostering social transformation. Since the Beijing Platform for Action (

UN 1995) and, more recently, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (

UN 2015), gender mainstreaming has been promoted as a global strategy to ensure that policies, practices, and institutions systematically incorporate gender analysis into their structures, decision making, and processes.

The SDG agenda situates gender equality (SDG 5) as both a stand-alone goal and a cross-cutting principle that underpins other objectives. In the context of higher education, this implies that achieving SDG 5 is inseparable from SDG 4 (quality education) and SDG 10 (reduced inequalities). For social work education, this means that gender-sensitive pedagogy is not only an internal curricular priority but also a lever for advancing inclusive and equitable societies. The interconnection of these goals positions universities as key actors in aligning professional training with sustainability and global justice, making gender mainstreaming central to the mission of preparing future practitioners.

In higher education, and particularly within social work programs, this approach has generated debates concerning curriculum design, pedagogical strategies, and field education. Nevertheless, the literature reveals a persistent gap between normative frameworks that advocate for gender equality and their concrete translation into teaching and professional preparation. This discrepancy raises critical questions regarding the effectiveness of pedagogical approaches and their impact on fostering professional self-efficacy for gender-sensitive practice.

This manuscript addresses that gap by synthesizing the literature on gender mainstreaming in social work education with specific reference to developments in Europe and Spain, while situating these within international trends. Notably, whereas Spain exemplifies a legally mandated, top–down approach, North America emphasizes accreditation standards and professional association guidelines, and Latin America and other regions of the Global South often draw on community-driven, activist-led models with variable institutional support. By making these contrasts explicit and situating them within sustainability discourses, the analysis highlights how gender mainstreaming in education can advance the interconnected aims of SDG 5, SDG 4, and SDG 10.

1.1. Normative Framework

At the global level, the Global Standards for Social Work Education and Training (

IASSW and IFSW 2020) position diversity, human rights, and equality as foundational principles of curricula and pedagogy, establishing gender equality not only as a compulsory standard but also as an aspirational goal for the profession. This vision aligns closely with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 5 on gender equality, SDG 4 on quality education, and SDG 10 on reducing inequalities (

UN 2015). Together, these frameworks highlight the role of social work education as a critical platform for advancing systemic social change rather than a purely technical training ground (

Dominelli 2017).

Building on this global framing, North American developments have placed strong emphasis on accreditation processes. The Council on Social Work Education’s (CSWE) Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards

(CSWE 2022) and the forthcoming Interpretation Guide (

CSWE 2025) embed anti-racism, diversity, equity, and inclusion (ADEI) across mission, curriculum, learning environment, and field education. By explicitly recognizing gender identity and sexual orientation as key dimensions of diversity, these standards operationalize equity commitments and prepare graduates to address intersecting forms of exclusion (

CSWE 2022;

Razack 2009).

Across the Atlantic, the European Union (EU) mandates gender equality through Article 8 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (

EU 2012) complemented by the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE), which provides tools such as gender budgeting and impact assessment. These efforts are reinforced by the European Higher Education Area and the Bologna Process, which integrate equality into quality assurance mechanisms (

Curaj et al. 2015;

EIGE 2022). Spain offers one of the most comprehensive models, where the Organic Law 3/2007 for Effective Equality (

Government of Spain 2007) and subsequent decrees (RD 6/2019 (

Government of Spain 2019); RD 901/2020a (

Government of Spain 2020a); RD 902/2020b (

Government of Spain 2020b)) legally require universities to adopt gender equality plans and mainstream gender across governance, teaching and research.

By contrast, in Latin America normative frameworks display significant variation. Countries such as Argentina and Chile have advanced progressive higher education policies shaped by strong feminist movements, embedding gender equality in curricular and institutional practices (

Guzmán and Montaño 2012;

Pérez Orozco 2014). Others rely more heavily on localized or ad hoc initiatives, which, while contributing to SDG 5, often lack systemic integration with SDG 4 and SDG 10.

A similar pattern of uneven adoption emerges across Africa and Asia, where gender mainstreaming is often shaped by UN-Women and UNESCO frameworks. However, resource limitations, postcolonial dynamics, and donor dependency constrain implementation, leaving many initiatives dependent on externally funded projects that advance gender equality (SDG 5) and inequality reduction (SDG 10) without systemic integration into higher education reform (SDG 4) (

Mama 2020;

UNESCO 2017).

Together, these regional trajectories illustrate distinct pathways: legislated models in Spain, accreditation-driven mechanisms in North America, quality-assurance approaches in Europe, and more community-oriented or donor-dependent strategies in Latin America, Africa, and Asia. For social work profession, these normative frameworks are not merely abstract policy instruments but intersect directly with faculty practice, student self-efficacy, and institutional climate (

Healy 2014;

Morley 1999). Yet their effectiveness ultimately depends on institutional uptake, faculty development, resource allocation, and enforcement, factors that determine whether gender mainstreaming remains rhetorical or becomes operational.

1.2. Research on Gender Mainstreaming in Social Work Education

Empirical research worldwide demonstrates both significant progress and persistent challenges in implementing gender mainstreaming within social work education. Despite the profession’s normative commitment to equality and social justice, integration of gender perspectives in teaching, curriculum design, and field education remains uneven. A systematic content analysis of 404 articles published in leading social work journals revealed that gender and gender inequality were rarely treated as central, structural phenomena, exposing a clear gap between rhetorical commitment and scholarly practice (

Dominelli 2020). Similarly, comparative studies across Europe have found that while universities often endorse gender mainstreaming principles, implementation tends to occur at a superficial or fragmented level, typically through elective modules, isolated workshops, or one-off lectures, rather than through comprehensive curriculum redesign or pedagogical transformation (

ETF 2022;

Lauritzen 2025;

Miralles-Cardona et al. 2025;

Rodríguez-Jaume and Gil-González 2025).

These findings point to the need for a closer examination of how gender mainstreaming is conceptualized, implemented, and experienced across contexts. The following subsections explore these dimensions in depth, addressing (1) the persistent implementation gaps and their drivers, (2) the uneven content domains where gender issues are addressed, and (3) the role of pedagogical approaches in fostering or constraining transformative gender learning in social work education.

1.2.1. Implementation Gaps and Their Drivers

Research literature on gender mainstreaming consistently documents the persistent implementation gap between policy and practice in higher education. Scholars identify several structural and conceptual drivers: ambiguity regarding whether gender mainstreaming should entail mere content inclusion or a broader restructuring of pedagogy and institutional culture; organizational inertia; political contestation; uneven faculty preparedness; and limited accountability mechanisms (

Lauritzen and Guldvik 2025;

Otero 2015).

In Spain, curriculum audits and program reviews indicate that gender-related content is frequently offered as elective rather than compulsory, resulting in uneven graduate competencies (

Díaz-Perea and González-Esteban 2019;

Raya and Montenegro-Leza 2021). Student-level evidence reflects this heterogeneity.

Álvarez-Bernardo et al. (

2024) document advances in addressing gender and sexual diversity but also persistent knowledge gaps regarding gender law and homonegativity. These findings underscore the importance of longitudinal, mandatory, and scaffolded learning pathways rather than isolated or optional modules. Qualitative studies further reveal that Spanish social work students often perceive gender content as peripheral or ‘add-on,’ reducing their confidence in applying such frameworks during field placements (

Raya and Montenegro-Leza 2021).

At the European level, similar challenges emerge. Although gender mainstreaming is firmly embedded in European Union policy frameworks, such as the European Higher Education Area principles and the European Research Area’s Gender Equality Strategy (

European Commission 2022), translation into pedagogical practice varies widely across contexts. Studies conducted in Nordic countries highlight more institutionalized and coherent approaches. For instance,

Heikkinen (

2016) report that Finnish and Swedish social work programs integrate gender equality and intersectionality throughout coursework, supported by strong institutional mandates and gender-sensitive accreditation standards. Conversely, research from Southern Europe reveals a more fragmented picture.

Bustelo et al. (

2019) demonstrate that gender mainstreaming in Mediterranean universities often depends on individual faculty initiatives rather than systemic strategies, leading to inconsistencies in curricular depth and pedagogical coherence. Cross-national comparative studies confirm that leadership commitment, faculty development opportunities, and national political climates critically shape how gender equality is enacted within social work education (

Caspersen et al. 2017).

Across North American contexts, accreditation frameworks such as the Council on Social Work Education’s Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards (

CSWE 2022) explicitly embed commitments to gender and diversity, yet structured implementation remains uneven. The large-scale Social Work Students Speak Out! survey (

Craig et al. 2015) found that 44% of students reported limited inclusion of LGBTQ+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and other identities) content across courses, while one-third noted direct experiences of bias or microaggressions. Similarly,

McInroy et al. (

2014) identified a ‘perceived scarcity’ of gender-identity content in Canadian social work programs, contributing to fragmented understanding and weak practice connections. Building on this,

Craig et al. (

2017a) revealed that tensions between personal and professional identities among LGBTQ+ students can undermine confidence in applying critical gender perspectives in field practice. More recently,

Jacobson López et al. (

2025) found that the presence of inclusive policies in U.S. social work schools was paradoxically associated with both higher intervention rates and increased reports of discrimination, suggesting that policy frameworks alone are insufficient without cultural and institutional change and pointing to a need for stronger alignment between diversity rhetoric, faculty training, and practice-oriented pedagogy.

In Latin American universities, the integration of gender perspectives in social work curricula reflects both progressive activism and structural vulnerability.

Díaz Mateus and Méndez Villamizar (

2025) show that in Colombia, gender-related content often relies on individual faculty advocacy rather than institutional mandates. Regionally, the Inter-American Development Bank’s report Gender, Education, and Skills in Latin America (

Näslund-Hadley et al. 2024) highlights enduring gender gaps in learning outcomes, particularly in rural and Indigenous populations, revealing that systemic inequalities shape even higher education.

Tomazini (

2025) documents how emerging anti-gender discourses in Brazil, Costa Rica, and Peru have begun to influence curricular reform, producing political tensions and rollback effects. These findings echo earlier observations that the sustainability of gender education in social work often depends on external partnerships with feminist or LGBTQ+ organizations, which, while valuable, remain vulnerable to political cycles and faculty turnover (

Rojas Hernández et al. 2025;

Vázquez-Martínez 2021).

In the Global South, gender inclusion in social work education often takes a symbolic rather than substantive form.

Turton and Schmid (

2020) documents how South African educators strive to decolonize and indigenize social work curricula by integrating local epistemologies and traditional practices; however, these efforts face structural barriers such as inadequate institutional support, limited staff training, and curricular resistance. Similarly,

Veta and McLaughlin (

2022) report that across African contexts, imported curricula from the Global North persist, constraining adaptation to local gendered realities and social justice concerns. These dynamics often leave students underprepared to address the intersectional dimensions of gender, race, and coloniality in practice. Recent studies on youth inequality (

Erasmus et al. 2025) further demonstrate how gender remains a key structural axis of injustice, reinforcing the urgency of embedding gender-responsive pedagogy within broader agendas of social transformation and decolonial education.

1.2.2. Content Domains

Two curricular domains exemplify the unevenness of gender mainstreaming in social work education: sexual orientation, gender identity and expression (SOGIE), and gender-based violence (GBV). In the Spanish context, although progress has been made in promoting LGBTQ+ inclusion, the integration of SOGIE-related content remains inconsistent and often optional. Qualitative accounts from LGBTQ+ students reveal highly variable classroom climates, some characterized by validation and allyship, others by microaggressions or subtle exclusion.

Álvarez-Bernardo et al. (

2024) examined knowledge and attitudes toward sexual and gender diversity among 512 social work students at two Andalusian universities and found that, while most participants expressed favorable views toward LGBTQ+ populations, persistent deficits in theoretical grounding and applied competence were evident. Students tended to show ideological openness to diversity but lacked the analytical and practical tools required for inclusive practice. Similarly,

Pérez Castillo and Rubio Guzmán (

2025) observed that gendered expectations continue to influence vocational motivations and the formation of professional identity among social work students in Spain, thereby reinforcing stereotypes surrounding the feminization of care professions. Regarding GBV, its curricular treatment remains fragmented. The Teaching Guide for Social Work and Social Intervention with a Gender Perspective at the University of Granada stands out as a notable example of comprehensive integration, connecting gender-based violence to issues such as poverty, migration, homelessness, and intersectional discrimination within an ethical and practice-oriented framework (

University of Granada n.d.). However, beyond these isolated initiatives, typically concentrated in postgraduate programs, the systematic inclusion of GBV content across core undergraduate courses such as social policy, practice methods, or research design remains limited, leaving many students feeling underprepared to address gender-based violence in their professional practice (

Raya and Montenegro-Leza 2021).

Across Europe, comparative evidence reveals a persistent North–South and West–East divide in the inclusion of SOGIE and GBV themes within social work curricula. Nordic and Western European countries, such as Sweden, Norway, and the Netherlands, tend to embed these topics more structurally through inclusive pedagogical frameworks and accreditation standards. Gender and sexual diversity are often addressed transversally across courses on ethics, social policy, and human rights. By contrast, in Southern and Eastern Europe, institutional prioritization is weaker and faculty training more uneven, resulting in fragmented curricular efforts (

Lauritzen and Guldvik 2025). Studies from Italy and Norway (

European Commission 2021) highlight that the integration of gender equality content frequently depends on individual lecturers’ activism rather than formalized institutional policies. European initiatives such as the EIGE Gender Equality in Academia and Research (GEAR) Toolkit and the Social Work for Social Justice Network have underscored the gap between policy rhetoric and pedagogical translation, noting that sustainable mainstreaming requires strong institutional leadership and continuous faculty development (

EIGE 2022).

North American experiences reveal similar tensions between formal commitments and actual implementation. The large-scale Social Work Students Speak Out! survey (

Craig et al. 2015) gathered responses from over 1000 LGBTQ+ social work students in the United States and Canada, showing that 44% perceived minimal LGBTQ+ content in their training, while one-third reported exposure to homophobia or exclusionary dynamics. Students often felt ill-prepared to work with transgender or nonbinary clients, despite higher confidence in engaging with gay and lesbian populations. Subsequent analyses (

Wagaman et al. 2021) highlight the emotional burden placed on students who advocate for curricular change, describing their efforts as a form of ‘activist pedagogy.’ Faculty perspectives mirror this tension, with

Jacobson López et al. (

2025) finding that while most instructors supported the inclusion of LGB topics, fewer endorsed comprehensive trans-inclusive content, citing insufficient institutional resources. Programs implementing structural changes, such as microaggression training, inclusive data collection, and classroom redesign, have reported modest improvements in campus climate, though these remain exceptions rather than the rule. Innovative pedagogical tools, including simulation-based modules and interprofessional workshops, have improved students’ ability to assess and intervene in domestic violence and gender diversity cases (

Childress et al. 2024). However, such practices are often elective and lack sustained institutionalization.

Latin American social work education operates within a hybrid framework of activist engagement and fragile institutionalization. Partnerships with feminist NGOs (Non-Governmental Organizations), LGBTQ+ collectives, and community organizations serve as catalysts for curricular innovation (

Vázquez-Martínez 2021). These collaborations enrich learning through experiential approaches but are highly dependent on external advocacy networks and political climates. Recent scholarship emphasizes the need for decolonial approaches that ground gender pedagogy in local histories and social movements.

Garrett (

2024), for example, calls for Latin American social work to reconcile global gender equality discourses with regionally rooted epistemologies, particularly those emerging from Indigenous and Afro-descendant perspectives. Some universities have piloted modules that integrate gender-based violence response, sexual diversity, and community-based interventions; yet these often remain optional or extra-curricular. Student collectives frequently act as agents of change, pressuring institutions to adopt gender awareness workshops, anti-microaggression training, and inclusive fieldwork placements. Nonetheless, structural obstacles such as limited faculty capacity, absence of institutional incentives, and ideological resistance continue to constrain progress. These dynamics reflect broader dialogues on racialized gender and feminist–decolonial learning emerging in Latin American universities, which challenge Western epistemologies and call for more locally rooted and intersectional pedagogical strategies (

Mahali and Tate 2025).

Across the Global South, gender mainstreaming in social work education is shaped by limited resources, epistemic disjunctions, and colonial legacies. Curricula frequently reflect Western paradigms that inadequately address local gendered realities (

Levy and Okoye 2023). Recent reforms in African social work education have sought to ‘localize’ curricula, integrating indigenous knowledges, customary law, and gender-based poverty analysis (

Schmid and Morgenshtern 2019). Despite these advances,

Amadasun (

2022) observes that GBV education remains fragmented, often delivered through NGO-led initiatives disconnected from formal degree programs. Innovative experiments in Kenya, Ghana, and South Africa attempt to bridge this divide through case-based fieldwork, partnerships with women’s organizations, and intersectional modules on gender justice. While promising, such efforts face sustainability challenges due to underfunding, curricular overload, and limited faculty training.

All together, these findings underscore two overarching trends. First, while SOGIE inclusion in social work education has expanded globally, LGBTQ+ and TGNC (Transgender or Gender Nonconforming) students continue to encounter gaps between institutional rhetoric and lived experience (

Messinger et al. 2019). Second, GBV education remains insufficiently mainstreamed, despite evidence that simulation-based, community-engaged, and interprofessional learning can significantly enhance students’ practical competencies (

Childress et al. 2024;

Renner and Driessen 2023). Building stronger bridges between policy frameworks, faculty development, and student-centered pedagogies remains crucial for achieving substantive gender mainstreaming across the social work curriculum.

1.2.3. Pedagogy: From Content Inclusion to Transformative Learning

Scholarly consensus increasingly emphasizes the need to transcend mere content inclusion and adopt transformative pedagogies that reconfigure classroom dynamics, critical reflection, and professional identity. Within social work education, gender-responsive pedagogy (GRP) represents a multidimensional approach that embeds gender considerations into curriculum design, teaching strategies, and assessment practices (

Chapin and Warne 2020;

Doroba et al. 2015;

Thege et al. 2020). Rather than treating gender as an isolated topic, GRP reframes it as a core analytic lens for understanding power relations and professional ethics. Intersectional feminist pedagogy extends this approach by equipping students to interrogate interlocking systems of oppression (gender, race, class, sexuality, and ability) while cultivating reflexive awareness of positionality and privilege (

Crenshaw 1989). These pedagogical orientations align with ADEI (access, diversity, equity, inclusion) frameworks but resist gender-neutral framings that obscure structural inequality.

Within Spanish and broader European contexts, implementation of GRP remains heavily reliant on individual academic leadership. Studies reveal that students’ engagement with gender-sensitive perspectives often depends on whether their instructors champion such approaches, leading to uneven exposure and fragile continuity (

Bustelo et al. 2019;

Lauritzen and Guldvik 2025). Recent European research underscores the influence of institutional culture and reward systems: gender pedagogies thrive where teaching excellence frameworks explicitly value inclusivity and social justice competencies (

Caspersen et al. 2017). Universities that integrate reflexive and dialogic learning through portfolio assessment, peer learning, and field-based gender audits report stronger student outcomes in empathy, critical thinking, and social accountability than those that do not.

Pedagogical innovation has been more systematically developed in North American schools of social work. Programs that employ simulation-based learning, role-play, and interprofessional training have shown notable impact in strengthening students’ confidence and readiness for practice (

Childress et al. 2024;

Craig et al. 2017b). Yet even within these settings, tensions persist. Students often describe a disconnection between institutional commitments to diversity and classroom practice when faculty avoid or depoliticize gender discussions, reproducing implicit bias and silence (

Jacobson López et al. 2025;

Messinger et al. 2019). As feminist educators argue, transforming pedagogy requires not only innovative methodologies but also affective safety, dialogical engagement, and institutional accountability for inclusion (

Brookfield 2017;

Morley 1999).

Pedagogical approaches emerging from Latin American social work demonstrate the transformative potential of activist and community-based learning. Teaching practices grounded in education popular traditions foster deep critical reflection and connect academic content with social mobilization and lived realities (

Vázquez-Martínez 2021). Students engaged in community projects often report heightened political consciousness and stronger ethical commitment. However, when activism substitutes for institutional responsibility, these practices can generate burnout and instability, especially in underfunded or politically polarized environments.

Across the Global South, experiential learning partnerships with NGOs, women’s organizations, and grassroots networks provide valuable opportunities for applied gender training, yet they frequently lack curricular coherence or institutional ownership (

Amadasun 2022;

Levy and Okoye 2023). Educators note that without adequate faculty training and structural support, gender pedagogy risks remaining peripheral rather than transformative. Efforts to ‘decolonize’ the social work curriculum by integrating indigenous epistemologies and gender justice perspectives are gaining traction but face challenges of scale and sustainability (

Schmid and Morgenshtern 2019).

Overall, the adoption of gender-responsive and intersectionality-informed pedagogy in social work education remains uneven across contexts. Small-scale studies consistently show that these approaches enhance conceptual understanding, ethical sensitivity, and practical competence (

Thege et al. 2020). Yet faculty frequently cite lack of preparation, institutional backing, and curricular time as barriers to systemic implementation. Moreover, institutional climates that marginalize gender learning or treat it as optional risk undermining classroom progress, emphasizing the need to align explicit, implicit, and hidden curricula toward genuinely transformative practice (

Morley 1999). Recent studies in adjacent fields also contribute valuable insights into the operationalization of gender-informed pedagogy. For example,

Miralles-Cardona (

2025) examined how teacher education programs integrate gender perspectives in both content and method, revealing similar tensions between institutional rhetoric and classroom practice. Likewise, the G-STEAM Project’s comparative study (

Miralles-Cardona and Cardona-Moltó 2025) documents how European teacher trainers embed gender equality in STEM education through specific teaching strategies and reflective approaches. These findings align with the present study’s approach and underscore the need for cross-contextual learning in how professional education fields implement gender mainstreaming. Complementary contributions from social work and health education also stress the importance of self-efficacy and institutional accountability in advancing inclusive pedagogy (

Morley 1999).

Building on these pedagogical insights, it is also important to recognize that culture and gender are deeply interconnected, and their intersection significantly shapes how gender mainstreaming is interpreted, received, and implemented across contexts. Cultural norms influence understandings of gender roles, power hierarchies, and professional behavior, which can either reinforce or challenge efforts to integrate gender perspectives in education. In multicultural classrooms or international frameworks, gender equality is not a universally neutral concept, but one mediated by cultural meanings and identities. As such, effective gender mainstreaming in social work education must not only address structural inequality but also engage with cultural diversity and intersectionality, acknowledging how gender intersects with ethnicity, religion, migration background, and other social categories. This intersectional lens is particularly critical in field education and practice settings, where students must navigate culturally complex situations and apply gender-sensitive approaches in contextually appropriate ways (

Crenshaw 1989). Ignoring cultural dimensions risks promoting a one-size-fits-all model of gender mainstreaming that fails to resonate with lived realities.

The preceding sections reveal a multidimensional yet fragmented picture of gender mainstreaming in social work education at three interrelated levels: (1) at the policy level, where ambitious frameworks and accreditation mandates coexist with limited institutional translation, resulting in a persistent implementation gap; (2) within curricula, where critical gender domains, particularly those addressing SOGIE and gender-based violence, are often relegated to elective modules or inconsistently integrated across programs; and (3) in pedagogical practice, where the adoption of gender-responsive and intersectional approaches remains partial and largely dependent on individual faculty leadership rather than embedded within institutional culture.

This body of evidence underscores a structural paradox: social work education, while normatively grounded in principles of equality and human rights, continues to reproduce gender-blind practices through fragmented curricula, uneven faculty engagement, and implicit norms that marginalize gender discourse. Students frequently perceive gender content as peripheral, which undermines their capacity to integrate equality frameworks into professional reasoning, fieldwork, and practice-based decision making. Such inconsistencies point to an urgent need to investigate not only what gender content is taught but how it is taught, and how pedagogical strategies influence students’ development of gender-responsive competence. Building on this rationale, the next section delineates the problem statement and research purpose, focusing on the relationship between gender-responsive pedagogy, institutional context, and social work students’ self-efficacy for gender-sensitive practice.

1.2.4. Gender-Sensitive Models and Field Education Approaches

Recent models of gender-sensitive practice in social work education have increasingly emphasized intersectional and praxis-oriented frameworks that go beyond content inclusion to integrate experiential, critical, and reflective learning. One such model is the Gender-Responsive Pedagogy for Social Work (GRP-SW), adapted from feminist pedagogical principles and grounded in anti-oppressive practice, which emphasizes participatory classroom dynamics, student positionality, and the co-construction of knowledge (

Chapin and Warne 2020). Programs adopting this model, particularly in North America and parts of Scandinavia, report enhanced student capacity to engage with complex gendered realities in practice settings (

Thege et al. 2020).

Field education has also seen innovations that aim to embed gender equity in real-world settings. Simulation-based learning modules, gender audits during internships, and community-based participatory projects have been used to scaffold students’ practical competence (

Childress et al. 2024). In Latin America and parts of the Global South, activist-led placements and decolonial fieldwork curricula are gaining ground, integrating feminist community engagement into social work education (

Garrett 2024). These approaches underscore the potential of field education not only as a site for skill acquisition, but as a platform for students to contest systemic inequalities and promote gender justice within professional practice.

1.3. Problem Statement and Purpose

Despite robust global and national commitments to gender equality, social work education continues to struggle with translating gender mainstreaming policies into pedagogical and curricular practice (

EIGE 2022;

UN Women 2018). As a profession grounded in social justice and human rights, social work has an ethical obligation to integrate gender analysis into the preparation of future practitioners. Yet, across Europe, and notably in Spain, this integration remains fragmented, uneven, and often dependent on individual faculty commitment rather than on coherent institutional frameworks (

Bustelo et al. 2019;

Lauritzen and Guldvik 2025). Moreover, critical gender domains, particularly those addressing SOGIE and gender-based violence, are frequently treated as elective or peripheral, resulting in inconsistent graduate competencies and reinforcing the perception of gender as an ancillary topic (

Díaz-Perea and González-Esteban 2019;

Raya and Montenegro-Leza 2021).

As a result, a persistent gap emerges between social work’s social justice mandate and the limited institutionalization of gender-sensitive training. This ‘implementation gap’ undermines both the ethical integrity and the practical efficacy of social work education, producing graduates who may feel ill-equipped to identify gendered harms, challenge discriminatory practices, or implement transformative strategies. Consequently, gender content is often perceived as peripheral, weakening the transfer of theoretical knowledge to field and community practice (

Raya and Montenegro-Leza 2021).

Social Cognitive Theory provides a useful lens to understand these dynamics through the concept of self-efficacy understood as individuals’ beliefs in their capacity to organize and execute actions to achieve desired outcomes (

Bandura 1997). Within social work education, gender-responsive and intersectional pedagogies can enhance self-efficacy through experiential and reflective learning that fosters mastery, vicarious learning, and emotional engagement (

Brookfield 2017). Conversely, hidden curricula that marginalize gender may erode confidence and reinforce gender-blind professional cultures.

In light of these challenges, the present study seeks to address this gap by examining how social work educators in a Spanish higher education institution integrate gender-responsive pedagogy into their teaching, and how these pedagogical strategies relate to students’ self-efficacy for gender-sensitive practice. By adopting a practice-oriented lens, the research explores the intersection between teaching approaches, institutional context, and student learning outcomes across three key domains of professional formation: knowledge, skills, and values. Building on this rationale, the study therefore poses the following research questions:

- (1)

How do social work educators incorporate gender equality, particularly SOGIE and GBV, into course content and pedagogical methods?

- (2)

To what extent do social work students feel confident and capable of applying gender-responsive practices as a result of their training?

Are there gender-based differences in students’ self-assessed knowledge, skills, and attitudes?

How are teaching approaches and curricular content associated with students’ gender-related self-efficacy?

- (3)

How does institutional climate (such as equality plans and gender mainstreaming in curricula and teaching) facilitate or constrain the relationship between pedagogy and student self-efficacy?

By linking gender-responsive pedagogy, student self-efficacy, and institutional context, the study aims to identify enabling conditions and barriers that shape gender mainstreaming in social work education, contributing to more transformative and equity-oriented professional training.

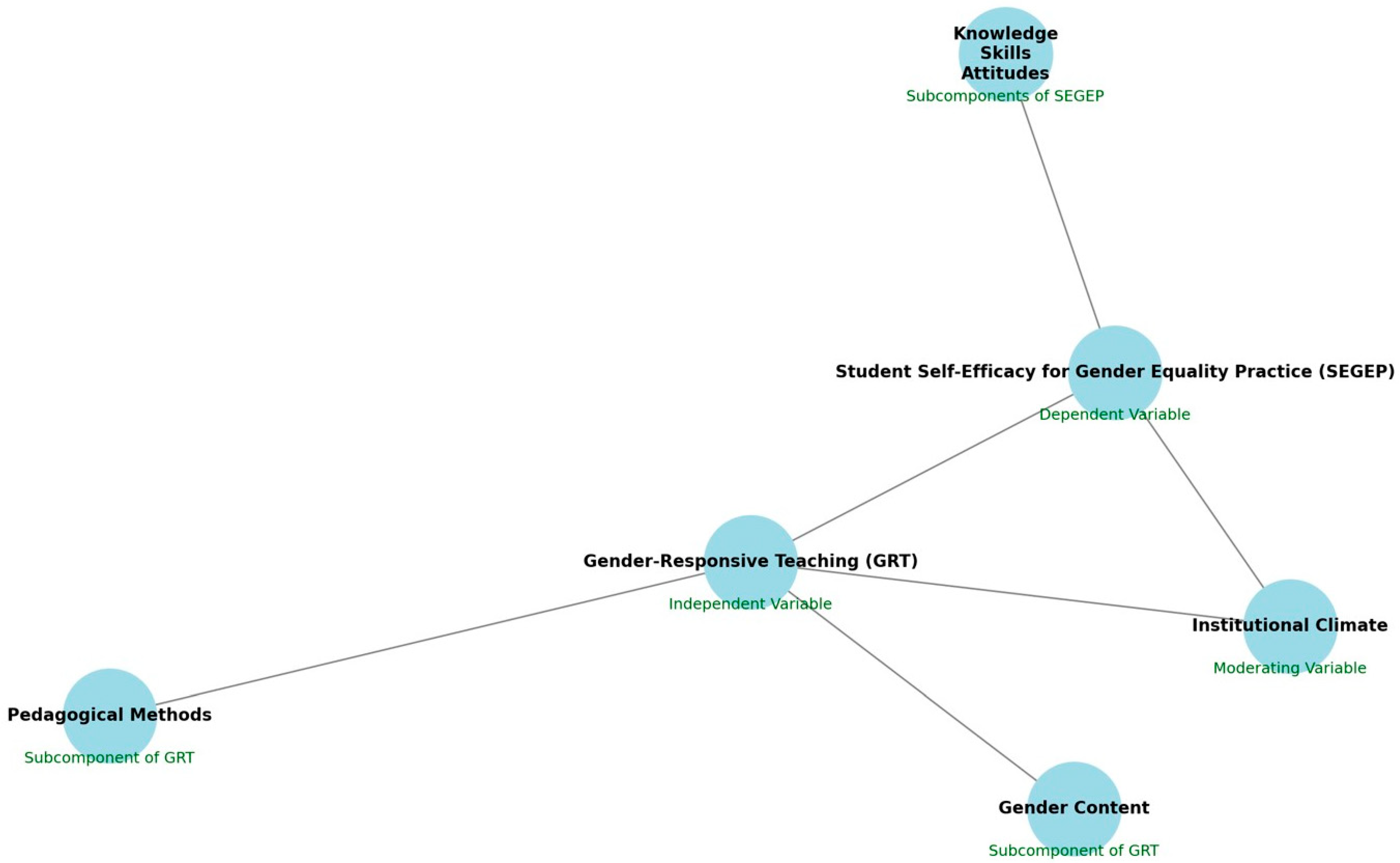

Figure 1 presents a simplified conceptual map of the hypothesized relationships among key study variables, showing how gender-responsive teaching and institutional climate influence students’ self-efficacy for gender-equality practice. The inclusion of Social Cognitive Theory (

Bandura 1997) in this study is grounded in its relevance for understanding how individuals develop confidence and competence in applying learned knowledge to real-world contexts. In particular, the concept of self-efficacy, a central construct within this theory, offers a robust explanatory framework for analyzing how students perceive their ability to engage in gender-sensitive practice. Within professional education, and specifically in social work, self-efficacy influences not only knowledge acquisition but also students’ willingness to act on their values in complex field situations. By integrating this theoretical lens, the study moves beyond descriptive assessments of content or pedagogy to examine how pedagogical strategies—such as participatory, intersectional, and reflective teaching—enhance or hinder students’ perceived capacity to implement gender-equitable practices in their future professional roles.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

The study employed a quantitative, non-experimental approach with a descriptive, cross-sectional survey design, incorporating comparative and correlational components to address the research questions (

Creswell and Clark 2018).

2.2. Participants and Context

The research was conducted at a publicly funded university in the Valencian Community, Spain. Founded in 1979, the institution is a modern, multidisciplinary university committed to teaching, research, and innovation. It currently enrolls approximately 24,000 students (academic year 2022–2023) (

University of Alicante 2024), with about 126 graduating annually in Social Work. The majority of these graduates were Spanish nationals (97%), with 3% of participants identifying as being of Latin American descent. In terms of gender, 80% were women. Data on socio-economic status was not collected. The bachelor’s degree in Social Work prepares professionals for social intervention with individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities, fostering competencies in mediation, education, advocacy, and social transformation (

Consejo General del Trabajo Social (CGTS) 2020).

Since the enactment of the Organic Law 3/2007 for the Effective Equality of Women and Men (

Government of Spain 2007), the university has developed several gender equality initiatives and is currently implementing its Fourth Equality Plan (

University of Alicante 2022). Nonetheless, progress in Axis 2: Teaching with a Gender Perspective remains limited. Only a small proportion of undergraduate programs incorporate gender-related competencies or offer specific courses on gender issues. In particular, seven out of 45 undergraduate programs (15.5%) include gender-focused courses, three compulsory and four elective. Although some faculty members report integrating gender perspectives into their teaching, most syllabi contain no explicit references to gender in learning objectives, course content, or teaching methodologies.

Participants consisted of 166 undergraduate students enrolled in the bachelor’s degree in Social Work at the University of Alicante. The sample was purposively selected to include students in their third and fourth years of study, as they had completed most of their academic training and were nearing the transition to professional practice. Given that the Social Work program admits approximately 200 new students each year, this sample can be considered broadly representative of the current student body within the degree program. Of these, 89 (53.6%) were in their third year and 77 (46.4%) in their fourth year. Ages ranged from 19 to 48 years (M = 22.58, SD = 3.79). The majority identified as female (n = 133; 80.1%) and nearly all as Spanish nationals (97%). A total of 38.6% (n = 64) reported having received formal gender training (range = 2–360 h; M = 29.79, SD = 45.96), whereas 61.4% (n = 102) had not. Approximately half of the students perceived institutional changes in governance following the implementation of gender equality policies, and 59% (n = 98) reported changes in teaching practices, compared to 41% (n = 68) who did not. Overall, participants rated gender equality training as highly important for their professional preparation (M = 9.15, SD = 1.66).

2.3. Instruments

Three instruments were used to measure faculty gender-responsive teaching practices, students’ self-efficacy for gender equality, and institutional climate.

Gender-Responsive Teaching (GRT) index: This scale measures gender-sensitive teaching practices and forms part of the Education for Sustainable Development Index for Gender Equality (

Miralles-Cardona 2024). It comprises 13 items grouped into two correlated factors: (1) Gender Content Taught (7 items), which assesses the extent to which educators integrate gender equality content into their teaching, and (2) Gender-Responsive Teaching Methods (6 items), which evaluates the use of inclusive and equitable pedagogical strategies. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Never to 5 = Always), with higher scores indicating greater integration of gender content and more frequent use of gender-responsive methods. Prior validation with preservice teachers showed high internal consistency (α > 0.90), strong content validity (CVI = 0.97;

Lawshe 1975), and sound construct validity (

Miralles-Cardona 2025). In this study, the factorial structure replicated the original two-factor model, except that one item (“Lecture-based teaching”) was removed after exploratory factor analysis and replaced with “Intersectional approach” to better align with social work pedagogy.

Self-Efficacy for Gender Equality Practice (SEGEP-SW): Students perceived self-efficacy was measured using an adaptation of the Teacher Efficacy for Gender Equality Practice (TEGEP) scale (

Miralles-Cardona et al. 2022). The adapted version for social work students included 20 items across three subscales: (1) Efficacy in Gender Knowledge (8 items), (2) Efficacy in Gender-Responsive Skills (8 items), and (3) Efficacy in Gender Attitudes (4 items). Items (e.g., “I can…,” “I am confident in…,” “I am able to…”) were rated on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 6 = Strongly Agree), with higher scores indicating stronger perceived competence in gender knowledge, skills, and attitudes. The SEGEP-SW demonstrated high internal consistency (α > 0.90) and validity comparable to previous samples in teacher education (

Kitta and Cardona-Moltó 2022;

Miralles-Cardona et al. 2023). Items from the Efficacy in Gender-Responsive Skills factor were adapted to the social work context; for instance, the TEGEP item “Creating learning environments that foster gender collaboration” was reformulated as “Building social environments that foster gender-equal participation and collaboration.”

Institutional Climate for Gender Equality: This construct refers to the organizational environment that facilitates or constrains the integration of a gender perspective in teaching, reflecting the coherence between institutional discourse, policies, and everyday practices. In this study, it was measured using five items from the Spanish version of the Education for Sustainable Development Index for Gender Equality (ESD-5) (

Miralles-Cardona 2024). Items 1 and 2 assessed perceived gender-related changes in governance and teaching (Yes/No responses). Items 3–5 evaluated the inclusion of gender issues in degree programs, curricula, and subjects on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 6 = Strongly Agree). Affirmative responses and higher Likert scores indicated stronger institutional commitment to gender mainstreaming and greater inclusion of gender content across programs. These items demonstrated good content and concurrent validity with the GRT and SEGEP-SW scales in the present sample.

2.4. Data Collection and Procedure

The study complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the EU General Data Protection Regulation (

European Parliament 2016). Exemption from full review was granted by the University of Alicante Research Ethics Committee (Approval Code: UA12162/2023).

Following ethical approval, contact was established with instructors teaching a compulsory course within the Bachelor’s Degree in Social Work program. Data were collected from all class groups of this course during regular sessions in the second semester of the 2023–2024 academic year.

The questionnaire comprised three sections: (1) demographic information (8 items), (2) the Gender-Responsive Teaching (GRT) Index (13 items), and (3) the Self-Efficacy for Gender Equality Practice Scale for Social Work (SEGEP-SW; 20 items). Participation was voluntary, anonymous, and confidential. Informed consent was obtained, and participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. Students who declined participation returned blank questionnaires. The survey required approximately 10–15 min to complete. A response rate of 75% was achieved, indicating adequate representativeness and minimal nonresponse bias.

2.5. Data Analysis

Before conducting the main analyses, all study variables were examined for accuracy, missing values, and adherence to assumptions of univariate normality (skewness ≤ 3.0 and kurtosis ≤ 10.0;

Weston and Gore 2006) as well as for potential outliers. Construct validity of the GRT and SEGEP-SW scales was assessed within the study sample through exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses (EFA and CFA). Model fit was evaluated using multiple indices, including the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Values above 0.90 for TLI and CFI and below 0.10 for RMSEA indicated acceptable model fit (

Bentler 1990). Details of data screening and validity evidence are presented in

Section 3.

Following these preliminary procedures, descriptive statistics, independent-samples t tests, and correlational analyses were conducted to examine gender-responsive teaching practices, students’ self-efficacy, and the influence of institutional climate on the relationship between pedagogy and student self-efficacy. Effect sizes were computed using Cohen’s d to assess the magnitude of group differences, where applicable.

Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated to explore associations between gender-responsive teaching (both content and methods) and students’ self-efficacy across dimensions of gender knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Additional analyses tested whether institutional climate and gender-focused training mediated or moderated the relationship between teaching practices and self-efficacy. To control for Type I error inflation arising from multiple independent-samples t-tests across the three domains of the Self-Efficacy Scale (Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes), Bonferroni corrections were applied within each domain. Given the number of comparisons conducted (Knowledge: 9 tests; Skills: 9 tests; Attitudes: 5 tests), adjusted significance thresholds were set at α = 0.0056 for the Knowledge and Skills domains and α = 0.01 for the Attitudes domain. Bonferroni corrections were also applied to the correlation analyses. Because each correlational table reflects a distinct set of hypotheses, we calculated adjusted thresholds separately for each one. These corrected values are reported in the table notes. All statistical tests were interpreted against these corrected alpha levels. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 28 and R version 4.4, with the significance level set at p < 0.05 for all tests.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Results and Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Preliminary screening indicated that the dataset met the criteria for accuracy, completeness, and adherence to statistical assumptions. Only cases with complete responses on the GRT index and the SEGEP-SW scale were included in the analyses. Descriptive statistics (

Table 1 and

Table 2) showed that GRT item means ranged from 2.67 to 3.90, reflecting mid-to-high response levels. Skewness values were slightly negative (−0.43 to −0.98), and kurtosis values (−1.01 to +1.14) were within acceptable limits. For the Self-Efficacy scale (range 1–6), mean scores were 4.76 (

SD = 0.67) for

Knowledge, 4.41 (

SD = 0.71) for

Skills, and 5.20 (

SD = 0.66) for

Attitudes, indicating generally high perceived competence. Although some items, particularly in the Self-Efficacy scale, showed mild negative skewness and leptokurtosis (e.g., Item 38, kurtosis = 5.75), these deviations were not severe.

Univariate outliers (<2%) identified through standardized z-scores and boxplots were retained due to negligible influence. Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s tests confirmed approximate normality and homogeneity of variances (p > 0.05). The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) values of 0.783 for the GRT Index and 0.861 for the Self-Efficacy scale, along with significant Bartlett’s tests of sphericity (p < 0.001), indicated adequate sampling and suitability for factor analysis. Exploratory factor analyses (Promax rotation) supported the hypothesized structures: two factors for the GRT index (55.45% of variance explained) and three factors for the Self-Efficacy scale (53.14% of variance explained). Reliability coefficients were satisfactory across all dimensions (α range = 0.74–0.90).

Confirmatory factor analyses using robust Maximum Likelihood Estimation and Full Information Maximum Likelihood further supported the expected structures of both instruments. For the GRT index, a two-factor model with correlated latent variables—Gender Content Taught and Gender-Responsive Teaching Methods—showed acceptable fit, χ2(64) = 97.65, p = 0.004, CFI = 0.908, TLI = 0.888, RMSEA = 0.066 (90% CI [0.035, 0.093]), SRMR = 0.070. All standardized loadings (0.32–0.74) were significant (p < 0.001), and composite reliability was acceptable (ω = 0.77 and 0.73). For the Self-Efficacy scale, the three-factor model—Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes—demonstrated a marginally acceptable fit, χ2(167) = 280.63, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.903, TLI = 0.890, RMSEA = 0.066 (90% CI [0.051, 0.080]), SRMR = 0.060. Factor loadings ranged from 0.47 to 0.80, and reliability values were high (α/ω range = 0.76–0.86).

Taken together, these findings confirm the construct validity, internal consistency, and theoretical soundness of both instruments. The GRT index effectively captures the dual dimensions of gender content and pedagogical methods, whereas the Self-Efficacy scale provides a reliable measure of gender-responsive competence across cognitive, behavioral, and attitudinal domains. Both instruments demonstrated strong psychometric properties and are suitable for research and educational assessment in social work education.

3.2. Gender Content Domains and Pedagogical Approaches

Descriptive analyses of the Gender-Responsive Teaching (GRT) index (

Table 3) revealed that faculty integrate gender-related content into their teaching, but the extent varies considerably across topics. The highest means were obtained for social justice and equity (

M = 3.90,

SD = 1.11), gender inequalities (

M = 3.82,

SD = 0.93), and gender-based violence (

M = 3.76,

SD = 0.94). In these areas, nearly 70% of students reported that faculty addressed these issues “often” or “always.” In contrast, items such as foundations and principles of gender equality (

M = 2.87,

SD = 1.05) and gender identity/expression (

M = 3.20,

SD = 0.92) were covered less consistently, with a substantial proportion of students indicating that they were addressed only “sometimes” or “rarely.”

Patterns for teaching methods were similar. Students reported more frequent exposure to intersectionality as a teaching lens (M = 3.30, SD = 1.12) and project-based teaching (M = 3.02, SD = 1.04). However, more interactive or innovative strategies such as case study-based teaching (M = 2.67, SD = 1.09), guided discovery (M = 2.80, SD = 1.11), and online/technology-based teaching (M = 2.72, SD = 1.19) were reported as used infrequently, mostly “rarely” or “sometimes.”

Overall, these findings suggest that while faculty prioritize core gender-related issues, such as inequality, equity, and violence, the pedagogical strategies employed are uneven and tend to rely less on active, student-centered approaches that research has shown to be effective in developing gender-responsive competencies.

3.3. Student Self-Efficacy for Gender Equality Practice

Students reported relatively high levels of self-efficacy in gender-responsive practice (

Table 4). In the

Knowledge domain, overall means were close to 5, with particularly high ratings for items such as gender stereotypes (

M = 5.07,

SD = 0.85) and gender-based violence (

M = 5.12,

SD = 0.94). By contrast, the lowest knowledge-related score was for gender biases (

M = 3.72,

SD = 1.19), suggesting that students feel less confident in identifying and addressing implicit biases compared to more explicit concepts such as roles or stereotypes.

Skills were rated moderately high (

M = 4.41,

SD = 0.68). Students reported stronger efficacy in building collaborative environments (

M = 4.68,

SD = 0.93) and collaborating with professionals (

M = 4.52,

SD = 0.99). Lower scores were observed for engaging families or entities in gender equality initiatives (

M = 4.07,

SD = 1.02), highlighting an area where participants feel less prepared.

Attitudes were the most highly endorsed domain (

M = 5.20,

SD = 0.60). Almost all students strongly agreed with statements such as criticizing tolerance toward discrimination and violence (

M = 5.54,

SD = 0.73) and conveying values of equity and diversity (

M = 5.33,

SD = 0.81).

In regard to gender differences in terms of gender knowledge, skills, and attitudes, independent-samples

t-tests (

Table 4) showed no significant gender differences across any of the three domains of gender Knowledge, Skills and Attitudes, indicating that both male and female students perceive similar levels of self-efficacy in applying gender-responsive practices. After applying Bonferroni corrections to account for multiple comparisons within each domain, no gender differences reached statistical significance in the Knowledge (adjusted α = 0.0056), Skills (adjusted α = 0.0056), or Attitudes (adjusted α = 0.01) dimensions. These results confirm that male and female students reported comparable levels of gender-related knowledge, skills, and attitudes. However, the association between teaching approaches and curricular content with student gender-related self-efficacy for gender-sensitive practice resulted statistically significant across the three domains. As

Table 5 shows, gender-responsive teaching methods were significantly correlated with all three domains of self-efficacy:

Knowledge (

r = 0.231,

p < 0.01),

Skills (

r = 0.239,

p < 0.01), and

Attitudes (

r = 0.181,

p < 0.05). The strongest association was with overall self-efficacy (

r = 0.275,

p < 0.01). By contrast, gender content taught was positively but not significantly correlated with student self-efficacy (ranging from

r = 0.095 to

r = 0.163), indicating weak and non-significant correlations.

These results highlight that the methods employed by faculty are more strongly associated with students’ sense of efficacy than the quantity of gender-related content included in coursework. In other words, students’ confidence in their gender-responsive practice appears to be more sensitive to how teaching is delivered than to what is taught.

3.4. Institutional Climate as a Moderator of the Relationship Between Pedagogy and Self-Efficacy

The role of institutional climate was examined by analyzing students’ perceptions of changes across different levels of the university context—governance, degree structure, curricula, teaching, and subject content. Inspection of

Table 6 and

Table 7 revealed mixed effects.

Institutional climate and teaching practices: Perceived changes in degree structure (r = 0.251–0.327, p < 0.01), curricula (r = 0.282–0.340, p < 0.01), and subjects (r = 0.244–0.329, p < 0.01) were significantly and positively correlated with faculty use of gender-responsive teaching practices. In contrast, perceived changes in governance were negatively correlated with teaching practices (r = −0.219 to −0.312, p < 0.05), suggesting that top-down policy reforms may not always translate effectively into classroom-level implementation.

Institutional climate and student self-efficacy: Perceived changes in degree structure (r = 0.241, p < 0.01) and subject content (r = 0.252, p < 0.01) were positively associated with students’ self-efficacy for gender equality. Conversely, perceived changes in governance were negatively associated (r = −0.175, p < 0.05). Neither perceived changes in curricula nor general teaching showed significant effects on self-efficacy.

Together, these findings indicate that institutional reforms at the degree and course levels are most strongly associated with gender-responsive teaching and students’ self-efficacy, whereas governance-level changes do not necessarily translate into benefits for teaching practice or student outcomes. In other words, governance-level initiatives, while important for institutional policy, do not necessarily translate into meaningful improvements at the classroom or student level and may even create a perception-practice gap.

4. Discussion

This study examined the extent to which gender-responsive pedagogy is embedded in social work education and how these practices influence students’ perceived self-efficacy for gender-sensitive practice. The results offer valuable insights into three interrelated areas: faculty teaching practices, students’ confidence in gender-related knowledge, skills, and attitudes, and the role of institutional climate in shaping these outcomes.

First, findings regarding faculty practices confirm previous evidence of the uneven implementation of gender mainstreaming in higher education (

Lauritzen and Guldvik 2025;

Miralles-Cardona 2025;

Raya and Montenegro-Leza 2021). Faculty were more likely to address topics such as inequality, equity, and gender-based violence, while foundational principles of gender equality and gender identity issues appeared less frequently. This pattern reflects trends observed in Spanish universities, where gender mainstreaming often remains confined to thematic content rather than embedded as a transversal pedagogical approach (

Tobías-Olarte 2018). It also echoes European findings that highlight an emphasis on visible gender issues while overlooking structural and intersectional dimensions. Moreover, the limited use of participatory methods such as case studies, guided inquiry, or digital learning tools supports earlier observations that gender-responsive pedagogy frequently depends on individual faculty initiatives rather than institutionalized curriculum design (

Chapin and Warne 2020).

Second, student outcomes revealed high self-efficacy in gender knowledge and attitudes but comparatively lower confidence in gender-responsive skills, particularly those requiring engagement with families and communities. These results align with studies showing that students often feel conceptually prepared yet struggle to apply gender frameworks in practice (

Messinger et al. 2019;

Miralles-Cardona et al. 2022). In Spanish social work programs, similar patterns have been identified, with students exhibiting strong theoretical awareness but limited experiential opportunities to operationalize gender analysis in fieldwork (

Raya and Montenegro-Leza 2021). Feminist theory has not only advanced the critique of gender inequality but has also contributed to rethinking

masculinity as a socially constructed, relational, and dynamic identity shaped by power and privilege. In the context of gender mainstreaming in social work education, this implies that engaging with feminism is not solely about addressing women’s rights but also about critically interrogating how dominant norms of masculinity, such as emotional suppression, authority, or distance from care work, are reproduced or challenged in professional training (

Connell and Messerschmidt 2005;

Hooks 2000). Educational strategies that center feminist and intersectional approaches can help students of all genders to deconstruct harmful masculine ideals and foster more egalitarian professional identities. This is particularly relevant in social work, where care, empathy, and collaboration—often undervalued in masculinized settings—are central competencies. Thus, feminism and masculinity are deeply interconnected: feminist pedagogy not only empowers marginalized genders but also opens transformative pathways for reconfiguring masculinities toward gender justice (

Pease 2019;

Elliott 2016). The absence of significant gender differences in self-efficacy contrasts with earlier findings of uneven preparedness between male and female students (

Otero 2015), possibly indicating a gradual normalization of gender equality discourse within the institutional culture studied.

Third, correlations between pedagogy and self-efficacy highlight the stronger influence of teaching methods over content coverage. This supports research on transformative and feminist pedagogies emphasizing that how gender is taught—through active, reflective, and dialogical strategies—has a more lasting impact on professional identity formation than content transmission alone (

Brookfield 2017;

Morley 1999;

Thege et al. 2020). In the Spanish context, these findings reinforce arguments that advancing gender-sensitive pedagogy requires sustained faculty training and alignment between equality policies and classroom practices (

Raya and Montenegro-Leza 2021). They also underline the importance of experiential and reflective learning as mechanisms for enhancing mastery, vicarious experience, and emotional engagement (

Childress et al. 2024).

Finally, the analysis of institutional climate showed that perceived changes at the degree and subject level were more strongly associated with both faculty practice and student self-efficacy than governance-level reforms. This finding supports the view that institutional change must extend beyond policy rhetoric to achieve tangible curricular and pedagogical transformation (

EIGE 2022;

UN Women 2018). Consistent with

Tobías-Olarte (

2018), these results suggest that effective institutional change in Spanish universities requires greater coordination between equality units and academic departments to prevent symbolic compliance and ensure meaningful implementation. The negative correlations with governance changes may reflect a perceived implementation gap, in which top–down reforms fail to translate into everyday teaching practices, a pattern documented in both Spanish and European contexts (

Díaz-Perea and González-Esteban 2019;

EIGE 2022).

Overall, the findings reaffirm that effective gender mainstreaming in higher education depends on both structural and cultural transformation, that is, combining legal mandates with pedagogical innovation. While social work students in this context appear well prepared in gender knowledge and attitudes, sustained investment in pedagogical innovation, faculty development, and program-level integration remains necessary to strengthen gender-responsive skills and ensure that institutional reforms genuinely foster equality in classroom and professional practice.

Limitations, Practical Implications and Recommendations

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the study employed a cross-sectional design, which restricts the ability to draw causal inferences. Longitudinal studies are necessary to assess how exposure to gender-responsive pedagogy influences self-efficacy over time. Second, data were self-reported, which introduces the possibility of social desirability bias, particularly given the normative value attached to gender equality in the Spanish context. Third, the sample was drawn from a single institution, limiting the generalizability of findings to other higher education settings or international contexts. Fourth, while validated instruments were adapted for social work education, future research could benefit from mixed-methods approaches that combine survey data with classroom observations and qualitative interviews. Future studies should also consider including comparison groups such as students enrolled in dedicated gender-focused courses to assess whether targeted instruction produces different outcomes from mainstreamed approaches.

Despite these limitations, the findings have significant implications for social work education. First, they demonstrate the need to move beyond content inclusion toward pedagogical transformation. Faculty training and institutional development programs should emphasize active learning, simulations, case-based discussions, and experiential projects that build students’ applied competence in gender-sensitive practice. Second, curricula should ensure systematic and mandatory integration of key domains such as gender identity, diversity, and gender-based violence, addressing the gaps identified in this study. Third, program-level accountability mechanisms are essential to ensure that governance-level policies translate into meaningful classroom practice. This includes embedding gender equality within learning outcomes, accreditation reviews, and quality assurance frameworks.

Recommendations for policy and practice include the following. At the institutional level, the participating institution should:

Mandate integration of gender-responsive pedagogy across all social work courses rather than leaving it to the discretion of individual faculty.

Invest in professional development for faculty, with workshops on feminist, intersectional, and experiential pedagogy.

Strengthen assessment frameworks, ensuring that self-efficacy in gender knowledge, skills, and attitudes is systematically evaluated.

Link institutional equality plans with teaching practice, creating incentives for faculty who effectively embed gender perspectives.

At the policy level, national and European frameworks could: (a) require universities to report on the implementation of gender equality plans in teaching and learning, not only governance; (b) provide funding for innovation in gender-responsive teaching methods, particularly in professional degrees such as social work; and (c) encourage cross-national collaborations to share good practices and create common benchmarks for gender mainstreaming in higher education.

For social work educators, the practical message is clear: how gender is taught matters more than how much content is included. This means designing classroom experiences that engage students in critical reflection, role-play, and collaborative problem solving, rather than treating gender as an abstract topic. Educators should also prioritize applied skills development, particularly in areas where students reported lower confidence, such as engaging families and communities in gender equality initiatives.

For institutions, the findings emphasize the need to align institutional climate and classroom practice. Governance-level reforms will remain symbolic unless translated into tangible curricular change at the program and subject level. Practical steps may include embedding required modules on SOGIE and gender-based violence, integrating gender into field placement criteria, and fostering partnerships with community organizations that provide experiential learning opportunities.

Ultimately, these findings reinforce the notion that preparing future social workers for gender-sensitive practice requires more than policy compliance. It demands a cultural and pedagogical shift in higher education that equips students not only with knowledge but also with the skills and values necessary to advance gender equality in professional practice.

To summarize, the results collectively demonstrate that:

Content integration of gender issues in social work education is progressing, but teaching methods lag behind, limiting the transformative potential of gender-responsive teaching.

Students display high self-efficacy in gender-related knowledge and attitudes, but have more modest confidence in practical skills, particularly those involving external collaboration.

Teaching methods show a stronger association with students perceived self-efficacy than content coverage, underscoring the value of participatory and practice-oriented pedagogies.

Institutional climate matters: reforms in curricula and teaching structures support GRT, whereas governance changes alone may be insufficient.

These findings contribute to the growing literature on gender mainstreaming in social work education by emphasizing the interplay between pedagogy, institutional structures, and student outcomes, suggesting that strengthening gender-responsive methods such as case studies, project-based learning, and intersectional approaches may better equip students to transfer knowledge into practice.

Building on these findings, several implications emerge for curriculum design, faculty development, and institutional strategy. First, the strong association between teaching methods and students’ gender self-efficacy reinforces the need to prioritize active, participatory pedagogies—such as simulations, gender case audits, and community-based learning—as standard components of professional education, rather than optional enhancements (

Childress et al. 2024). These strategies not only foster skill development but also strengthen students’ ability to transfer theoretical knowledge into field-based decision-making.

Second, the weaker or non-significant effect of governance-level reforms suggests that top-down equality plans alone are insufficient unless accompanied by bottom-up implementation mechanisms that reach program and classroom levels. Institutions should therefore invest in intermediary structures—such as gender task forces within faculties, teaching innovation grants for equity projects, and cross-departmental training communities—to bridge this gap between policy and pedagogy (

Brookfield 2017).

Third, the study highlights content–method misalignment: although gender topics are present in curricula, the absence of inclusive and interactive methods limits their transformative potential. Curriculum reviews should therefore evaluate not only what content is included but also how it is delivered, with periodic assessments of student competencies in applying gender frameworks to real-world contexts.

Finally, the high student endorsement of gender-responsive attitudes, combined with lower confidence in applied skills, indicates a readiness for deeper engagement. This presents an opportunity to embed formative feedback cycles within field education allowing students to reflect on their gender-related interventions, receive structured input from supervisors, and build professional confidence through practice-informed learning.