Reflections on Working Together in an Inclusive Research Team

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. About the Team and the Research Project

- Conduct focus groups with people with intellectual disabilities

- Conduct interviews with local government representatives

- Co-facilitate workshops with the local government

- Analyse and synthesise results from the focus groups and interviews

- Plan each next stage of the project and negotiate contributions

Inclusive Analysis of Data

2. Materials and Methods

- What has it been like for non-academics on the team to work at a university?

- What have we learnt working together?

- What has worked well?

- What would you do differently?

3. Results

3.1. Reflections on What Worked Well

JK: We are all from different backgrounds—not necessarily disability—and we all bring something special to the team.

JK: This office isn’t focused on disability-related work and have a different take on it. What I mean is, this office doesn’t have the word ‘disability’ in it

PC: Because our faculty and school had not undertaken any inclusive research before, there were no rules to guide us—this worried me at first. But then, we realised that we could do our best work, and no one was limiting our scope on what was inclusive or how to do it—instead we looked to the lived experience within the team, of self-advocacy and advocacy, to guide us. It worked well because we built our own rules and ways of working together.

PC: We had very supporting professional staff, who worked with us to ensure that the needs of everyone in the team were met—this might include accessing assistive technology, supporting with administration activities, accessing the building, finding spaces for us to work together.

JK: We are a dream team; I think when you are building a research team you have to have people who are on the same page with ideas and with the same outcome in mind.

PC: We could plan for regular meetings, and everyone could be kept up to date on the project’s progress and activities. I knew that Thursday was our project day. For me, I really appreciated everyone being together, and sharing the decision making on a regular basis. I would not have liked to be working remotely or managing the team individually—we really were together, working together.

JK: I have a lot of flexibility; I can have a break anytime I want.

JK: This was the first team where my manager totally understood the way that I like to operate; it took other employers a long time to adjust to the working style that I have.

PC: We established an understanding and respect for each other’s time availability and the time taken to plan for attendance and performance of key activities e.g., co-facilitating focus groups at various local government locations. It takes time to make sure that support staff are available, to organise transport and check accessibility of venues. For people with disability who rely on support staff and accessible transport to meet their job requirements, allowing for this forward planning is very important.

3.2. What Was Difficult—What We Would Do Differently

3.3. Barriers to Doing Best Practice Inclusive Research

PC: One thing I would do differently, as the manager of the inclusive team and project, and I would feel more confident about it now, is that I would employ more people with lived experience of intellectual disability on the core team. …in the intensive focus group and feedback parts of the research, such as when we are doing roundtables—I feel that expecting one person to represent diversity on the project, to come in part time, and to be present to co facilitate, co-interview, co-chair in those busy times. …puts pressure on that team member because of the value and importance of their lived experience.

3.4. Perspectives on the Label of Intellectual Disability

CD: The most striking thing for me working for the first time with people with intellectual disability has been the overwhelming discomfort with the label and facing the prejudice that is embedded […] in this. JK’s contributions to the work are insightful and very often profound. JK articulates the essence of things succinctly and keeps the project’s integrity, values on track with clear and kind redirection where we need it.

CD: I have personally really struggled with the appropriateness of the label “intellectual disability” when I believe the contribution of JK as a core team researcher and the focus group participants is in fact the critical work. The rest need to adjust, learn and be humbled to these ways of seeing and being in the world.

PC: We did our best to make the project and our teamwork a success. Sometimes things got in the way—like a structure or a system. For example, budget limitations meant we had to do things differently, not employ as many people, but we recognised that part of the learning process is accepting that our inclusive research might not be perfect first time, and that we can improve and build upon the process we have learnt along the way.

3.5. Reflections on Access and Inclusion in the Workplace

CD: The second thing I have learnt is the concept of accessibility extending well beyond the physical. This highlights the need for designers in the built environment to be far more educated.

AH: We found out early on that the campus wasn’t accessible in some ways. The fire stairs couldn’t house more than one person using a wheelchair.

JK: The online payroll system can be confusing and does not work with voice-to-text. I needed to have help to fill it in. We have got used to it now though.

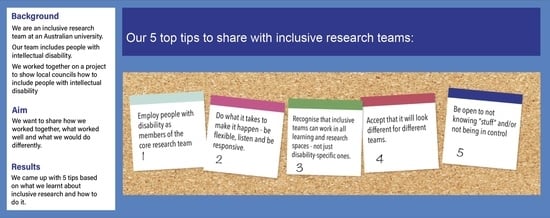

3.6. Inclusive Research Is Doable—Here Are Our Top Tips

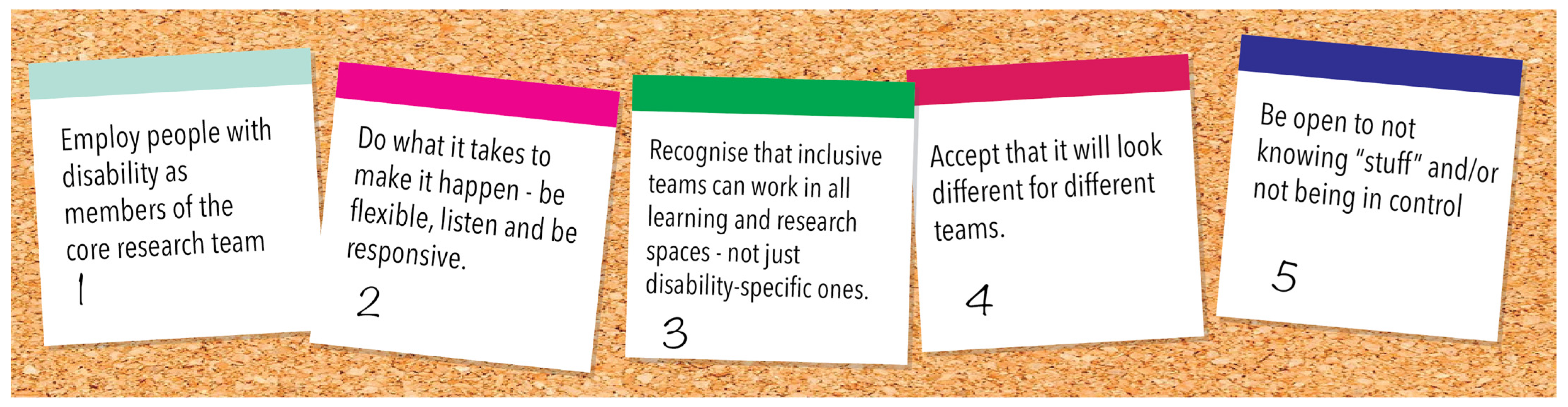

- Employ people with the lived experience of disability as members of the core research team. We regard this as one of the most valuable and critical features of the success of our project. We all worked together, bringing together a range of skills—each team member had the opportunity to take the lead and share their skills and knowledge about inclusive research. The project we worked on can be found here: https://www.uts.edu.au/node/284291/what-we-do-old/research/my-home-my-community (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Do what it takes to make it happen—be flexible, listen and be responsive. Build expertise and experience into the team—this includes the lived experience of people with an intellectual disability, as well as experienced advocacy and support experts, to ensure that peer skill building takes place. Work out early on how people prefer to work and communicate and adjust the team environment and processes to suit everyone. Partner with community organisations to bring additional inclusive research knowledge and expertise (we were grateful to be able to partner with the Council for Intellectual Disability (CID) for some parts of our project).

- Recognise that inclusive teams can work in all learning and research spaces—not just disability-specific ones. There are many opportunities to utilise the benefits and increased impact of community-led, diverse teams across the university campus.

- Accept that it’s going to look different for different teams. Everyone has different ways they like to work and different skills to contribute, and personalities work differently together. Not only this, but every project will have different priorities and outcomes.

- Be open to not knowing ”stuff” and/or not being in control. It is okay to not be an expert in inclusive research straight away. Listening and surrounding oneself with experienced people (both self-advocates and advocates) is a great way to navigate what inclusive research can be.

4. Discussion

- “What kinds of knowledge are directly attributable to inclusive research (intellectual capital)?

- How these knowledge claims can be assessed and authenticated (methodological capital)

- The benefits of the experience to individual service user researchers (individual capital)

- In relation to project teams, what forms of partnership (managerial and social capital) make inclusive research effective and whether good science and inclusive research can be integrated.”

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). 2012. Intellectual Disability Australia. 2012 4433.0.55.003. Employment. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4433.0.55.003main+features452012#:~:text=Labour%20force%20data%20was%20collected,of%20the%20non%2Ddisabled%20population (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Bigby, Christine, Patsie Frawley, and Paul Ramcharan. 2014. Conceptualizing inclusive research with people with intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 27: 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonham, Gordon Scott, Sarah Basehart, Robert L. Schalock, Cristine Boswell Marchand, Nancy Kirchner, and Joan M. Remenap. 2004. Consumer-based quality of life assessment: The Maryland ask me! Project. Mental Retardation 42: 338–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Nicole, and Jennifer Leigh. 2018. Ableism in academia: Where are the disabled and ill academics? Disability & Society 33: 985–89. [Google Scholar]

- Buitendijk, Simone, Stephen Curry, and Katrien Maes. 2019. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion at Universities: The Power of a Systemic Approach. LERU Position Paper. Available online: https://www.leru.org/files/LERU-EDI-paper_final.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Bumble, Jennifer L., Eric W. Carter, Lauren K. Bethune, Tammy Day, and Elise D. McMillan. 2019. Community conversations on inclusive higher education for students with intellectual disability. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals 42: 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnemolla, Phillippa, Jack Kelly, Catherine Donnelley, Aine Healy, and Megan Taylor. 2021a. “If I was the Boss of My Local Government”: Perspectives of People with intellectual Disabilities on Improvong Inclusion. Sustainability 12: 9075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnemolla, Phillippa, Sally Robinson, and Kiri Lay. 2021b. Towards inclusive cities and social sustainability: A scoping review of initiatives to support the inclusion of people with intellectual disability in civic and social activities. City, Culture and Society 25: 100398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalachanová, Anna, Kirsten Jaeger Fjetland, and Anita Gjermestad. 2021. Citizenship in everyday life: Stories of people with intellectual disabilities in Norway. Nordic Social Work Research, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H., Faith Ngunjiri, and Kathy-Ann C. Hernandez. 2016. Collaborative Autoethnography. London: Routledge, vol. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll, Amy. 2008. Carnegie’s community-engagement classification: Intentions and insights. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 40: 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Gordon, and Paul Ramcharan. 2009. Valuing people and research: Outcomes of the learning disability research initiative. Tizard Learning Disability Review 14: 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High, Rachel, and Sally Robinson. 2021. Graduating University as a Woman with Down Syndrome: Reflecting on My Education. Social Sciences 10: 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Kelley, and Jan Walmsley. 2003. Inclusive Research with People with Learning Disabilities: Past Present and Futures. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, Katherine E., and Erin Stack. 2016. You say you want a revolution: An empirical study of community-based participatory research with people with developmental disabilities. Disability and Health Journal 9: 201–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellifont, Damian. 2021. Ableist ivory towers: A narrative review informing about the lived experiences of neurodivergent staff in contemporary higher education. Disability & Society, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, Paul, and Patsie Frawley. 2019. From ‘on’ to ‘with’ to ‘by: ‘People with a learning disability creating a space for the third wave of inclusive research. Qualitative Research 19: 382–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS Digital. 2021. Measures from the Adult Social Care Outcomes Framework, England 2020–2021 Digital NHS. Government Statistical Service. Available online: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/adult-social-care-outcomes-framework-ascof/england-2020-21 (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Nicolaidis, Christina, Dora Raymaker, Marsha Katz, Mary Oschwald, Rebecca Goe, Sandra Leotti, Leah Grantham, Eddie Plourde, Janice Salomon, Rosemary B. Hughes, and et al. 2015. Community-based participatory research to adapt health measures for use by people with developmental disabilities. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action 9: 157–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nicolaidis, Christina, Dora Raymaker, Steven K. Kapp, Amelia Baggs, E. Ashkenazy, Katherine McDonald, Michael Weiner, Joelle Maslak, Morrigan Hunter, and Andrea Joyce. 2019. The AASPIRE practice-based guidelines for the inclusion of autistic adults in research as co-researchers and study participants. Autism 23: 2007–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nind, Melanie. 2014. What Is Inclusive Research? London: A&C Black. [Google Scholar]

- Nind, Melanie, and Hilra Vinha. 2012. Doing Research Inclusively, Doing Research Well? Report of the Study: Quality and Capacity in Inclusive Research with People with Learning Disabilities. Available online: https://www.southampton.ac.uk/assets/imported/transforms/content-block/UsefulDownloads_Download/97706C004C4F4E68A8B54DB90EE0977D/full_report_doing_research.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Nind, Melanie, and Hilra Vinha. 2014. Doing research inclusively: Bridges to multiple possibilities in inclusive research. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 42: 102–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotner, Anthony J., and Kathleen J. Marshall. 2015. Postsecondary education programs for students with an intellectual disability: Facilitators and barriers to implementation. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 53: 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Sally, Phillippa Carnemolla, Kiri Lay, and Jack Kelly. 2022. Involving people with intellectual disability in setting priorities for building community inclusion at a local government level. British Journal of Learning Disabilities. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Ariel, and Brendan Durkin. 2020. “Team is everything”: Reflections on trust, logistics and methodological choices in collaborative interviewing. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 48: 115–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Ariel, Jessica M. Kramer, Ellen S. Cohn, and Katherine E. McDonald. 2020. “That felt like real engagement”: Fostering and maintaining inclusive research collaborations with individuals with intellectual disability. Qualitative Health Research 30: 236–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, Erin E., and Katherine McDonald. 2018. We are “both in charge, the academics and self-advocates”: Empowerment in community-based participatory research. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 15: 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strnadová, Iva, and Jan Walmsley. 2018. Peer-reviewed articles on inclusive research: Do co-researchers with intellectual disabilities have a voice? Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 31: 132–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strnadová, Iva, Therese M. Cumming, Marie Knox, Trevor Parmenter, and Welcome to Our Class Research Group. 2014. Building an inclusive research team: The importance of team building and skills training. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 27: 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroman, Katherine M. 2019. “And Then You Can Prove Them Wrong”: The College Experiences of Students with Intellectual and Developmental Disability Labels. Ph.D. thesis, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley, Jan, Iva Strnadova, and Kelley Johnson. 2018. The added value of inclusive research. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 31: 751–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehman, Paul, Joshua Taylor, Valerie Brooke, Lauren Avellone, Holly Whittenburg, Whitney Ham, Alissa Molinellu Brooke, and Staci Carr. 2018. Toward competitive employment for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities: What progress have we made and where do we need to go. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 43: 131–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Emma, and Michelle F. Morgan. 2012. Yes! I am a researcher. The research story of a young adult with Down syndrome. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 40: 101–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Erin, and Robert Campain. 2020. Fostering Employment for People with Intellectual Disability: The Evidence to Date. Available online: Everyonecanwork.org.au (accessed on 10 January 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carnemolla, P.; Kelly, J.; Donnelley, C.; Healy, A. Reflections on Working Together in an Inclusive Research Team. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11050182

Carnemolla P, Kelly J, Donnelley C, Healy A. Reflections on Working Together in an Inclusive Research Team. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(5):182. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11050182

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarnemolla, Phillippa, Jack Kelly, Catherine Donnelley, and Aine Healy. 2022. "Reflections on Working Together in an Inclusive Research Team" Social Sciences 11, no. 5: 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11050182

APA StyleCarnemolla, P., Kelly, J., Donnelley, C., & Healy, A. (2022). Reflections on Working Together in an Inclusive Research Team. Social Sciences, 11(5), 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11050182