Abstract

Academic and community research partnerships have gained traction as a potential bridge between the university and local area to address pressing social issues. A key question for developing justice-oriented research is how to integrate best practices for creating genuine, authentic research partnerships. In this paper, we discuss the process of building a critical community-engaged project that examines how urban redevelopment changes neighborhoods within immigrant and/or communities of color. Focusing on Long Beach, California, in this article, we detail the development of a mixed-methods study that involves undergraduate students and community members as co-collaborators. We discuss the use and outcomes of co-walking as method, emphasizing observational findings, as well as the process of building team collaboration. We find that neighborhoods in Long Beach are changing rapidly in terms of the use of greening, increased technology integration within neighborhoods, and modern aesthetics, revealing that new residents will likely be younger and single residents with disposable income and no children. From this process, we identified a more critical question for the research project: “Development for whom?”. We argue that co-walking as method is an observational and relational process that assists with the foundational steps of building a critical community-engaged research project.

1. Introduction

The call for more critical community-engaged research (CER) approaches has challenged universities to question their contribution to the public good. Academic and community partnerships in research have gained traction as a potential bridge between the university and the local area to address pressing social issues. However, developing justice-oriented research raises a key question: how can university-based research teams integrate best practices for building critical community-engaged projects, particularly genuine, authentic research partnerships? Inspired by scholars such as Gordon da Cruz (2017), we discuss the use of walking as method (Cheng 2014; Jung 2014; Newhouse 2012; Pierce and Lawhon 2015; Sletto and Vasudevan 2021) as an observational and relational process for building a critical community-engaged project that examines how urban redevelopment changes neighborhoods within immigrant communities and/or communities of color.

Focusing on the city of Long Beach, California, located 20 miles south of Los Angeles, we detail the process of developing an interdisciplinary mixed-methods study that involves undergraduate students and community members as co-collaborators. Drawing on the participatory method of observational co-walking, we discuss the selection of and engagement with four neighborhoods in Long Beach as case studies. These neighborhoods have a large population of racial minorities and/or a notable immigrant population, have been heavily redeveloped since 2015, and are in ongoing or advanced stages of gentrification. We found that neighborhoods in Long Beach are changing rapidly in terms of the use of greening, increased technology integration with neighborhood products and services, and modern aesthetics, revealing that new residents will likely be younger and single residents with disposable income and no children. From this process, we identified a more guiding question for the project: “Development for whom?”. In this article, we highlight two key outcomes of using observational co-walking. First, walking offers an embodied observational process (Pierce and Lawhon 2015) that gave the research team the opportunity to immerse ourselves in the neighborhoods of study and see “up close” the changes to multiple spaces, such as the streets, alleys, businesses, and parks, which helped formulate research questions. These questions are based on the empirically observed material conditions of these neighborhoods, helping the research team connect local to global processes to explain why neighborhoods are changing and their impact on immigrant communities and/or communities of color. Secondly, co-walking facilitated a process that was important for building the research team’s partnerships. Observational co-walking provided an interactive pedagogical mentorship for students from the studied neighborhoods and gave them a chance to lead data collection and be key knowledge holders and producers. We discuss the outcomes of our walking, emphasizing the observational findings, as well as the process of building team collaboration. We argue that observational co-walking as method is an observational and relational process that assists with the foundational steps of building a critical community-engaged research project.

In this article, we highlight the work of the House It SoCal project, a team of faculty and undergraduate scholars of color at California State University, Long Beach (CSULB) studying housing instability. Situated in Los Angeles County in southern California, CSULB serves a majority student-of-color, Pell-Grant-eligible population with a notable and growing number of first-generation and transfer students. Developing a critical community-engaged project means first reflecting on the process of both “collaboratively developing critically conscious knowledge” and “authentically locating expertise” (Gordon da Cruz 2017), both of which are key components of critical CER.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Building Community-Engaged Research and Partnerships

Much of the substantial existing scholarship on community-engaged research (CER) addresses the process of conducting such research, mostly from the perspective of academia. Scholars reflect on the process of developing and sustaining community partnerships, various ways to engage with the community, and the impact of CER as it relates to policy change and community capacity building (Patraporn 2019; Sangalang et al. 2015; Stoecker 1999). The literature on community-engaged research utilizes case studies to discuss the research process and findings or reviews and analyzes themes and concepts across the existing literature (Beaulieu et al. 2018; Gordon da Cruz 2017; Minkler and Wallerstein 2008).

A main theme in this literature is the challenge of conducting community-engaged research, particularly best practices for building equitable university and community research partnerships. Practicing ethics and understanding differences in norms, values, power, and privilege requires the establishment and negotiation of roles, addressing the imbalance of power, as well as constant reflection and communication about centering projects based on justice and knowledge from within communities (Campano et al. 2015; Curnow 2017; Mendes et al. 2014; Minkler and Wallerstein 2008; Sandwick et al. 2018). Researchers need to first reflect on their goals and the degree to which this matches the community’s strategy and then consequently exercise flexibility and pragmatism in research design, implementation, and analysis (Nation et al. 2011).

Moreover, authentically engaging marginalized populations—particularly Black, indigenous, and people of color—remains an obstacle to successful CER. For example, in their meta-analysis of national health and medical trials, an area where community-engaged research has been readily employed, Brown and Moyer (2010) found that Asian Americans, Blacks, and Latinos had few positive perspectives of medical research relative to whites (see also George et al. 2014). To remedy this distrust, engaged scholars must spend a significant amount of time developing partnerships, listening, and being in dialogue with those directly impacted by the policies and issues on which their research is focused (Ma et al. 2004; Sandwick et al. 2018).

2.2. Applying a Critical Approach to CER

To address the challenges of developing meaningful CER, Gordon da Cruz (2017) proposes researchers employ a critical approach to CER. Dr. Cynthia Gordon da Cruz coined the term critical community-engaged scholarship to distinguish it from the myriad related terms utilized in the field—namely community-based research, community-engaged scholarship, CER, and publicly engaged scholarship, among others—which do not necessarily center the communities for which the work is being done. Essentially, critical CER emerged as a concept to emphasize the importance of researchers engaging community members in an authentic way that acknowledges power dynamics, aiming to redistribute power and make society more just. This is opposed to an inauthentic approach where, for example, few community representatives are included to provide their opinions, resulting in unequal power or roles in decision making. According to Gordon da Cruz, critical CER also centers research outcomes on justice rather than just “public good” and transformative change as opposed to incremental change. This approach challenges the existing framework, which suggests that seeking the “public good” is sufficient. With critical CER, the goal of transformative change addresses the structures of oppression that are at the root of the social issues/problems being investigated. In adopting this approach, community-engaged scholars would prioritize, value, and respect the voice of marginalized communities. The critical CER approach addresses tensions and structures of power in community–university partnerships in terms of both methods and overall project outcomes.

In this paper, we respond to two critical questions outlined by Gordon da Cruz (2017) to develop a critical CER project: (1) Are we collaboratively developing critically conscious knowledge? and (2) Are we authentically locating expertise? Similarly to Fine and Torre (2019), we utilize a critical community-engaged framework to reflect on our own process of data collection and knowledge creation, which centers on student involvement and community collaborations. We use two of Gordon da Cruz’s critical questions as part of a process of reflecting on ways to create knowledge to address social change. Walking as a method offers another perspective for studying neighborhood change and, in many cases, an alternative method to more traditional approaches in which knowledge has been acquired through surveys and interviews (Jung 2014; Pierce and Lawhon 2015). As neighborhoods and spaces change, it is imperative that we seek not just perceptions and self-reporting methods through surveys and interviews but also ways for people visually observe how their physical space and aesthetics change; such change has meaning for the sense of community and belonging, which are both critical to the health and well-being of Black, indigenous, and people of color (Anguelovski et al. 2020; Anguelovski 2015; Curran 2018; Desmond 2016; Gibbons et al. 2018; Hyra et al. 2019). The method of walking is an embodied practice of moving through and seeing spaces that remind people of experiences and spark ideas that they would not otherwise have been reminded of in an interview or survey (Pierce and Lawhon 2015).

2.3. Walking as Method: Observational Co-Walking of the City

Whereas much of the existing research on neighborhood change draws from perceptions via surveys (Carlson 2020; Preis et al. 2021), this research project expands on the literature by utilizing an observational and participatory approach to examine place and neighborhood change via urban redevelopment. Walking as method is an ethnographic approach that allows researchers to participate in the public life of the groups they are studying (Cheng 2014; Jung 2014; Newhouse 2012; Pierce and Lawhon 2015; Sletto and Vasudevan 2021). This method is particularly well-suited to studying urban space (Pierce and Lawhon 2015), offering another perspective to study the everydayness of urban life and change (Irwin 2006). Moreover, researchers who also live in the areas they observe contribute an in-depth and more nuanced perspective that adds to construct validity.

Walking is an immersive and exploratory method for understanding the context of the community of study through the direct observation of everyday urban space. As Rita Irwin (2006) states, walking allows the researcher to “notice the extraordinary in the ordinary” (p. 76). Walking opens up possibilities for the researcher to explore the field with a focus of study while also being open to the unplanned nature of “real life” (Newhouse 2012). Called different names, such as mindful walking (Jung 2014) or observational walking (Pierce and Lawhon 2015), conceptually, these approaches draw on the concept of dérive, which, according to Jung (2014), “…involves walking purposefully to understand how urban city landscape, architecture, spaces, and places affect emotions and behaviors of people living in the city, and therefore, helped develop a new approach to urban planning based on psychogeography to design more suitable and playful urban spaces for the future…” (p. 624). This method is especially important in the study of urban spatial changes and the potential impact on city residents as a starting point for building authentic research partnerships for policy-oriented research. Immersion via walking in urban life is focused on a reflexive process of understanding physical, social, and spatial contexts.

We use observational walking as a collaborative process of building critically conscious knowledge. Sletto and Vasudevan’s (2021) work on co-walking with students highlights the use of co-walking for co-production of knowledge as a key critical pedagogical approach. Inspired by critical pedagogy and indigenous epistemologies, the authors discuss how they use observational co-walking to “promote critical reflexivity and co-productive learning” (p. 4) as a process that disrupts epistemological assumptions about expertise between teacher and student and helps us more authentically locate expertise. Co-walking disrupts the formalized power relations between teacher and students, allowing both parties to connect with the world directly, fostering new learning environments that can empower all team members.

3. Methods

House It SoCal is an interdisciplinary mixed-methods project that examines the impact of housing instability on immigrants in southern California. For this article, from the perspective of residents and as outside researchers, our team of university faculty and undergraduate students describe two findings using co-walking: (1) our observations of how neighborhoods have changed as a result of urban development; and (2) the process of building research team collaboration. As a method of question building, the project observed four neighborhoods in Long Beach, a large coastal city in Los Angeles County with a large population of racial minorities and a significant immigrant population facing ongoing or advanced stages of gentrification. To observe physical changes in neighborhoods, our research team uses observational co-walking. The following sections discuss the planning and observation process in four Long Beach neighborhoods. With two main questions—“How does capital accumulation change space?” and “How has urban redevelopment changed the neighborhood?”—we detail the process of co-walking to make observations of neighborhood change in Long Beach. We first discuss the process of selecting these four neighborhoods and the steps of preparing and conducting walking as a method.

3.1. Neighborhood Selection

The Long Beach neighborhoods selected for this study shared two characteristics: (1) both had a large population of immigrant residents and (2) both were sites with booming urban development projects since 2015. After identifying neighborhoods with large populations of people of color and a notable population of immigrants (Long Beach Census Tracts 2010), we identified the neighborhoods affected by urban redevelopment, and we reviewed the City of Long Beach’s Development Services Department online interactive mapping tool (Long Beach publiCity 2021). In addition, we used the Urban Displacement Project’s (2021b) interactive map to confirm that these neighborhoods were in ongoing or advanced stages of gentrification. Based on these characteristics, we selected four neighborhoods as case studies: Downtown Long Beach, West Long Beach, North Long Beach, and Central Long Beach. Additionally, data from the US Census Bureau (2019a, 2019b, 2019c) was used to research the demographics of each area. Because of this, before walking these neighborhoods, the team made sure to walk within specific zip codes of each neighborhood. Downtown Long Beach was only walked within the 90802 zip code, as well as West Long Beach (90806), North Long Beach (90805), and Central Long Beach (90804).

The demographics of Downtown Long Beach (90802) consist of residents that come from diverse backgrounds, including Latinx (34.6%), followed by Black residents (16.2%), and Asians (9.8%). Furthermore, about one-fifth (20.8%) of those residing in this area are foreign-born, and the majority of these residents are unnaturalized (56.4%). Downtown Long Beach’s population is young; about half the population is younger than 50; 6.7% are between the ages of 20 to 24, 25.2% are between 25 and 34 years old, and 17.1% are between 35 and 44. In addition to their youth, the area has a median income of USD 54,616 (US Census Bureau 2019a, 2019b, 2019c).

West Long Beach (90806), also known as the Wrigley Area of Long Beach, is a diverse area, with 54% of the population being minorities; Asians make up the largest group, at 20.3%, and Black residents follow, at 17.4%. It is also important to note that 68.2% of the population are native-born to the US, whereas 31.8% are foreign-born (US Census Bureau 2019a, 2019b), and the median income for the area is USD 54,437 (US Census Bureau 2019c). The neighborhood was one of interest for the researchers due to various reasons. First, the Wrigley Area, more specifically Willow Street, and surrounding streets were on the border of two different areas, where one went through stable displacement and the other is experiencing ongoing displacement. While conducting preliminary research of the area prior to selection, the researchers noticed new trendier spots, such as coffee shops and a modern brewery, popping up near older spots. Trendy new spots are an indicator of gentrification, as they invite more white and affluent people to come to the neighborhood, eventually increasing the neighborhood’s economic value (Hyra 2015).

The North Long Beach (90805) neighborhood is also home to a large minority population. The majority is Latinx, making up 59.9% of neighborhood residents, along with 20.2% Black residents and a notable Asian American community that makes up 11.9% of all residents. In addition to the racial makeup, it is important to note that 29.9% of residents are immigrants; 49% of the population are naturalized, and the other 51% are undocumented. Furthermore, 17.4% of the residents are between the ages of 25 and 34, and 12.8% are between the ages of 35 and 44 (US Census Bureau 2019a, 2019b, 2019c). In recent history, most notably in the 1930s, Long Beach redlined people of color from buying homes in certain neighborhoods, and by the 1960s, the neighborhood of North Long Beach fell subject to “blockbusting” (Addison 2019; Long Beach Health and Human Services 2022). Essentially, real estate agents convinced white residents that people of color were moving in, and in turn, white residents would sell their houses at a low price. The real estate agents would then resell the homes to Black homeowners for a much higher price, consequently making the area of North Long Beach a neighborhood where many Black residents reside (Addison 2019). Although historically seen as an area of the city with majority Black residents, displacement, as well as urban redevelopment of the neighborhood, has brought about shifts in demographics, resulting in the Black community no longer representing the majority in the area.

The fourth neighborhood studied was Long Beach’s Cambodia Town, a specific area on the east side of Long Beach that is about one mile long along Anaheim Street. Cambodia Town holds much cultural and community significance for Long Beach, especially for the Cambodian population, as many Khmer businesses were there. Racially, 58.4% of the residents are White, 18.1% are Asian, and Black residents make up 13.7% of the population. The median income is USD 52,948, and 73.8% of residents are native-born to the US, whereas 26.2% are foreign-born (US Census Bureau 2019a, 2019b, 2019c). Unfortunately, historic plazas and businesses that have been serving the ethnic community have been closing in the past few years. Walking through the neighborhood reminded us of the importance of such institutions to Cambodia Town and the community at large. For example, KH Market has been serving the community since the 1990s (Addison 2018) and was recently shut down in mid-2021. This closure of a historic market where we, the researchers, have fond memories was saddening and drew us to survey this area in particular when thinking of gentrification. Cambodia Town’s Plaza is part of an ongoing project to put in new businesses and revamp current ones but at the cost of a few longstanding “mom and pop” businesses.

3.2. Co-Observational Walking in Long Beach

The House It SoCal team is composed of faculty and students of color. The two students, who are also co-authors, are first-generation working-class students of color, sociology majors, and born and raised in Long Beach. The student collaborators were mentees in a university research program and contacted the faculty co-authors, who were mentors in the program, to participate on the research project. The mentees were selected due to their excellent academic record and research background, in addition to their community service in Long Beach on the topics of housing and immigrant experiences. The team’s demographics shape the mentors’ approach to working with undergraduates, particularly because the faculty’s own demographics and academic background are similar to those of the students. Focusing on mentorship, the faculty members—both of whom are women of color and were born in or have been residents of Long Beach—recognized the distinct and difficult role of the students, especially during the pandemic. We kept this in mind when planning the methodology and steps of the larger research project, utilizing digital and online measures as utilized in other similar participatory action research (Auerbach et al. 2022). For example, we made sure to meet frequently with the team on Zoom to ensure that questions and concerns were addressed quickly, both for the project’s timeline and the students’ assurance. Using team communication and project management platforms such Slack and Google Drive, we have facilitated group rapport despite primarily meeting via Zoom due to the pandemic. Walking allowed us to spend time in person while also adhering to social distancing and masking protocol for everyone’s health and safety. We began meeting in person for walks during a period of the pandemic when stricter restrictions had been lowered so we did not experience challenges in observing the everyday use of urban space by community members. In addition to collecting data, we allocated time during our meetings for professional development, for example, to discuss questions about graduate school, prepare a conference abstract, or write a research article on project findings. Overall, recognizing and valuing the unique experiences and capital of historically excluded communities of color (Fine and Torre 2019; Yosso 2005) informs the collaborative approach between faculty and students of color on this project. Developing rapport is key to building a sentiment of collaboration for the team, especially when building undergraduates’ and community members’ confidence in their own ability to discuss ideas and conduct research (Baum et al. 2006; McIntyre 2014). Because of the similar backgrounds of the academic researchers and undergraduate researchers/community members, the students felt confidence in their reflections, as well as in guiding the method and process for data collection and analysis (McIntyre 2014). These components were important for building the research team and instilling a sense of respect and value of the different contributions of all team members, regardless of experience or rank.

In the first meetings of the team, we started with our own personal observations of changes in Long Beach by asking, “What changes have we seen?”. For example, the KH Market was closing in May 2021, a staple store for the Cambodian community of Central Long Beach and a significant cultural loss for immigrant residents in the area (Niebla 2021). This event sparked a conversation on the changes we were seeing as we moved through the city, as well as the new businesses that have opened in the areas where ethnic businesses once were. Many of these changes were happening in the neighborhood of students, making the topic of study personal and relevant to their lived experiences. All co-authors come from immigrant backgrounds, so we began talking about the symbiotic relationship between global migrants and US cities. Making connections between local phenomena and global flows was important to highlight David Harvey’s work, which examines the city as an engine for the maintenance and reproduction of global capitalism (Harvey 2012). Furthermore, thinking about space and power, as well as race/ethnicity and nativism, we reflected on belonging in the twenty-first century and struggles of immigrants and their families to, first, integrate and, second, years later, face housing instability and possible displacement due to urban development.

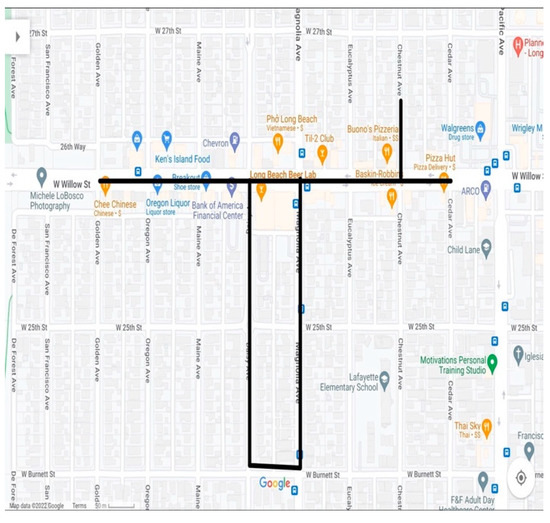

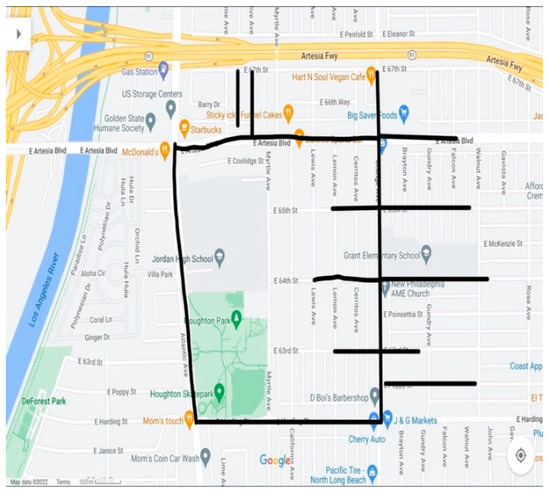

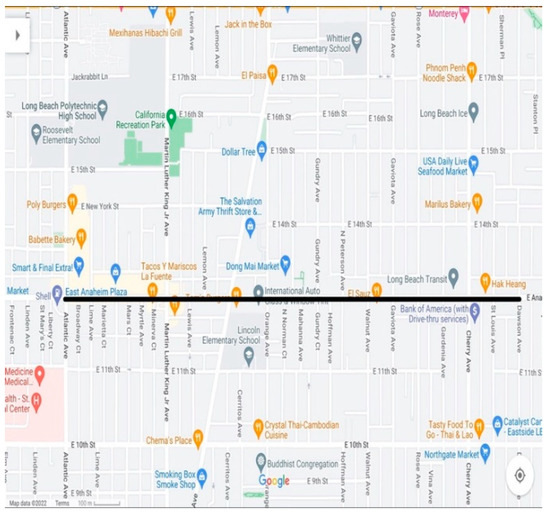

These discussions led to the guiding question for the project: How does capital accumulation change space? We explore this question by using walking to observe how urban renewal development has changed neighborhoods with large populations of immigrants and residents of color in Long Beach. To prepare to walk the neighborhoods, we first found maps to identify the street boundaries of the area and created a walking map of the streets (see Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4). With maps of current and future LB development projects in the neighborhood and key development projects, we created maps as guides for our walking. We also brought our cameras to photograph the urban development projects as visual ethnographic field notes. In addition, photographs allowed the entire team to examine the neighborhood changes together and identify recurring themes and thus also participate in the immersive method of walking. However, for this paper, we are focusing on solely reporting the findings from our observations walking each neighborhood.

Figure 1.

Path walked in Downtown Long Beach.

Figure 2.

Path walked in West Long Beach, Wrigley.

Figure 3.

Path walked in North Long Beach.

Figure 4.

Path walked in Cambodia Town.

3.3. Urban Redevelopment in Long Beach

The recent wave of urban development in Long Beach began ten years ago, with the passing of the Downtown Plan (2012). Located slightly south of Los Angeles, Long Beach’s effort to develop has been tied to the economic strategy of boosting the beach city’s tourist economy (Hytrek 2019). The Downtown Plan, approved on 10 January 2012 by Long Beach City Council, is “the development blueprint that would guide the direction of the downtown’s growth and land use for the next 25 years” (Flores 2022). With the passing of the Downtown Plan, height limits for skylines were lifted, and parking spots were reduced in downtown, ushering in a new urban development era in Long Beach. “Between 2013 and 2016, the City of Long Beach saw $734 million in development at 770 major project sites” (Urban Displacement Project 2021a). Similarly, as of mid-2019, “more than 7000 new housing units, 1000 new hotel rooms and 4-million square feet of new commercial, industrial and municipal space either completed or in the pipeline since 2017” (Munguia 2019). However, the Downtown Plan did not include adequate renter protections. Still a majority blue-collar city due to the proximity of the port and harbor industry jobs, Long Beach faces an urgent housing crisis due to a lack of available, affordable, and safe places to live. Now, this plan is used as a model for development in other areas of Long Beach, such as North Long Beach’s new Uptown Commons, a two-acre lot that houses a collection of restaurants in converted shipping containers.

However, these development plans have not taken into account the needs of long-time Long Beach residents, the majority of whom—more than 60% of residents—are renters (Long Beach Housing and Neighborhood Services 2022). The concerns raised in 2012 about the Downtown Plan, such as a lack of affordable housing, extreme rent burden, overcrowding, and homelessness, have come true (Flores 2022). For example, 81% of people who lived downtown were renters between 2010 and 2020, and during that decade, rents downtown increased by 32% (Housing Element 2021). Overall, almost half of all households in Long Beach are cost-burdened, meaning residents pay more than 30% of their monthly income on housing costs. Furthermore, 12% of households are overcrowded (Long Beach Housing and Neighborhood Services 2022). According to Long Beach journalist James Carroll (2021), the areas that experience the most overcrowding are renter-occupied households in Central, North, and West Long Beach. These neighborhoods also are home to immigrant communities in Long Beach.

Although renewed areas of Long Beach have benefited economically, these changes have affected immigrants who are also primarily renters. Among 113,259 immigrants who live in Long Beach, one-fourth of all live in Downtown, West, North, and Central Long Beach neighborhoods (US Census Bureau 2019a, 2019b, 2019c). Among this total, the majority are renters and have experienced housing burden for the past ten years; 63.5% of renters in 2010 and 65.4% of renters in 2019 (US Census Bureau 2010, 2019a). More than 50% of immigrants in Long Beach pay more than 30% of their household income in rent. In 2019, median gross rent was USD 1460, an amount significantly above the national median of USD 1097 and slightly below the median for California, at USD 1614 (US Census Bureau 2019a, 2019b, 2019c). In addition to increasing housing costs, overcrowding, and possible displacement, immigrant communities in Long Beach are seeing their neighborhoods change rapidly with the systemic closure of ethnic businesses (Niebla 2021), replaced by boutiques, cafes, and apartment developments that no longer cater to the long-settled communities.

4. Results

4.1. Greening

In the neighborhoods that we explored, we noticed that each neighborhood has begun to green their spaces. We define greening as initiatives the City and area are taking in order to decrease pollution and promote “clean air” modes. The City of Long Beach has been taking more green approaches in the city and encouraging its’ residents to do the same by providing more alternative modes of transportation and creating more urban parks and greenbelts.

While canvassing the neighborhoods, we noticed bike lanes appearing more frequently on the roads. When walking along the streets in Downtown Long Beach and North Long Beach, we saw newly painted bike lanes on the street. We find that this subtle change to the road conveys a message of the activities of the people residing in the surrounding neighborhoods. From seeing the bike lanes, we took notice of the rideshare bicycles and scooters around the area for people to take “greener” ways to traverse the city. However, we feel that these bike lanes imply that the people who would be able to use these ways of transportation would be a population who had more time, energy, and physical ability. This usually coincides with a younger demographic that prefers an environmentally conscious way of living.

Furthermore, within all the neighborhoods that have been explored, it was noted that there was a pattern of electric scooters and bikes that were being made available for residents. These alternative modes of transportation being more prominent throughout the city showcases how the city is pushing for transportation that is greener. In West Long Beach, our attention immediately fixed upon a designated BIRD electric scooter parking spot on the sidewalk where riders can drop off the scooter after using it for easy access. This parking spot also encourages people to check out and visit the area, marking it for increased foot traffic and revenue. Around the corner from this parking spot were Long Beach City bikes that the City has been placing more frequently around the city to encourage residents to use these alternative modes of transportation. Both the bikes and scooters are low-cost, making them not only a greener decision but a cost-efficient mode of transportation for residents. However, you needed a phone with access to a debit or credit card and knowledge of how to navigate the application to be able to rent the bikes and scooters.

Walking through these neighborhoods provided us with more information, as we could physically interact with the space and take note of things that could be glossed over if walking had not taken place. For example, going from the street, taking short cuts through alleys, and checking out the front and inside of businesses. This allowed us to reflect and sparked new questions. For one, how do greening and urban development correlate? We bring forth this inquiry because we noticed that areas that are becoming gentrified utilize rideshare bikes and other forms of green transportation that are owned by large companies. Thus, how does green gentrification support capital accumulation? As younger residents of the city, we are glad to see greener modes of transportation that are easy for us to use. However, we feel conflicted, as we know not everyone can use a greener and more cost-efficient mode of transportation.

The City has been taking steps to green urban spaces as well, which can be seen in their efforts to create safer and more accessible parks throughout the city. For example, in the neighborhood of North Long Beach lies Houghton Park, where there has been an effort to make the park greener, including a community garden, and the park itself has been fully updated. As we were walking, one of the research assistants reminisced about how Houghton Park looked when they were growing up and would visit the park whenever they came to the area to visit a family member. The student described that the park was unkept and remembered walking into potholes in the grass from time to time. It was not until recently that the City began to put an effort into beautifying and greening the park, making it more accessible and useful to residents. From this reflection, the team member discussed how they felt about the park being upkept now and how they felt that the city is becoming more gentrified throughout. The area is becoming nicer to appeal to more affluent people who could possibly move to the area. The member also felt that the City disregarded the residents that lived there before by not doing more to provide a better park for them to use beforehand. Upon hearing the research assistant’s experience and how they felt, the team developed the question, “Why is the city making these changes now, and who are these changes catering to? What was the catalyst for the new attention directed at this park?”. Uptown Commons, a new trendy compound with several restaurants and breweries in North Long Beach, is not far from this park, so we also discussed the question, “Is gentrification a virus that spreads and infects nearby areas?”.

4.2. Technology

In addition to the greening that was prominent in the neighborhoods that were canvassed, the amount of technology that was seen throughout each area was also noted. By technology, we refer to the integration of technology throughout the neighborhoods, such as rideshare transportation, QR codes, and contactless payment. We also discussed how the city itself utilizes technology, the different businesses moving towards more technology, and its potential impact on residents.

When walking throughout the neighborhood, we noticed that the scooters and bikes that are used to provide greener modes of transportation also represent how technology is becoming more integrated in the neighborhoods throughout Long Beach. The use of scooters and bikes requires a person to have access to a phone, credit card, and identification card. Furthermore, if a person has a phone, the phone itself must have enough data to reach the website and the process of payment. This point was not brought up during the walk but when the members were able to reflect on what they saw throughout the neighborhoods. When meeting again to discuss what we saw, we noted that the only way to access the bikes and scooters would be through a phone and card. If a person was of a lower-income status and did not have adequate data or a phone, they would not be able to utilize these greener modes of transportation. Furthermore, we discussed that these modes of transportation are more accessible to a group that is younger and more affluent. For one, younger generations are usually more tech-savvy, as they grew up using technology in school and life. Secondly, having a good phone and data to both access the website and process the payment for these rideshare bikes and scooters is limited to those who can afford it. As the city continues to utilize and promote these types of transportation that rely heavily on technology, it will continue to attract and entice a younger, more affluent population. Thus, this allowed the team to form the question, “How does integrating more technology throughout the city exclude certain residents?”. We were especially concerned about residents who belong to an older generation.

Restaurants and shops have been using contactless payment more frequently, especially since the pandemic, to minimize contact in public. These methods are being used, as they allows for ease of payment, as customers simply swipe, insert, or tap their card or phone to pay for their items. We noticed this in establishments such as the Starbucks and Wendy’s in North Long Beach. We, the researchers, used contactless payment via our phones at both establishments, as it was easy to tap our phone on the card reader. The ease of access and payment was attractive to us, as it did not require us to count physical money or find our wallet and insert our card. Reflecting on this, we noted the ease of paying for things but also how this might harm others. Contactless payments advantage those who have debit/credit cards and those who have good phones to use for Apple and Google Pay. However, contactless payment harms those who may have to stick to physical cash due to inability to get a credit/debit card, as well as those who are not able to get good phones with data. The increased usage of contactless payment made us question, “How does the advancement of technology better life but also harm? How do we help those not able to utilize and access the new technological advancements? Who are these new developments, that are supposed to better everyone’s life, really for? Who are urban developers really focused on?”.

The integration of technology has been popping up more in public-use spaces. For example, we noticed in Harvey Milk Park in Downtown Long Beach that the sign had a QR code for individuals to view the park virtually park and interact with different options through their phones. However, we observed that this excludes those who are poorer and may have devices that are not QR-code-compatible. This issue showcases how these technological innovations reveal antipoverty development that limits access for those with less income. It instead favors a younger population of residents who have money to afford both good data and phones that can read QR codes and are technologically savvy to know how to use the feature.

Discussing North Long Beach once again, we noticed QR codes to scan to see the virtual menus for the restaurants in Uptown Commons. Uptown Commons is a recent development with trendy restaurants surrounding by updated franchises. The piece of paper holding the QR code was relatively easy for us researchers to scan, as we were able to scan it via our camera app on our phones. As researchers who are tech-savvy, the codes were convenient and easy to utilize. During our discussion after the walk and what we saw, we talked about how these QR codes can be disadvantageous for certain groups of people. Those who may not have phones or good data to access the content from the QR code do not benefit from the “easier” method. Furthermore, some restaurants may only offer their menu virtually unless asked for a physical menu. This switch to virtual menus may deter those not able to access online content easily. In particular, people may not feel good enough to eat at restaurants if they cannot even access their menu, and they may feel out of place. This showcases how these areas that are being gentrified are catering to a younger audience for whom these services are both appealing and easy to use, while consequently pushing out older generations.

4.3. Aesthetics

One major way that we were able to identify a change in space was the current aesthetics and vibes of a neighborhood. As residents of the city, we noticed the physical changing of space via artworks and trendier businesses, along with the lack of businesses. We use the word “trendy” to describe businesses that follow modern aesthetics, which will be further discussed in the following paragraphs. The continuous change of space was present in all neighborhoods due to the increase in the number of trendy businesses, beautifications, and closing of certain businesses.

Throughout our walks in the neighborhoods of Long Beach, we noticed prominent the changes in aesthetics and look of many of the buildings. Furthermore, in some of the neighborhoods, we noticed more modern buildings and exteriors coexisting with out-of-date, dilapidated buildings. As researchers, we identify more modern-looking buildings by their use of neutral, monochromatic colors; wood paneling; and simplicity, all of which are aesthetics affiliated with gentrification. For example, in West Long Beach, a trendy Beer Lab was positioned next door to a rundown building housing small offices. This mixture can indicate a major sign of gentrification: trendier places beginning to take over next to the old places. The trendier place of Beer Lab will increase foot traffic to the area, which may make owners of buildings update their businesses to keep up with the trends and money. When seeing the duality of the businesses, we wondered, “When is the rundown building going to be updated? Or will it eventually become another trendy business?”.

When walking around Cambodia Town along Anaheim Street and nearby smaller streets, it was hard to miss that the multiple businesses that were closed down had been ethnic businesses. In one plaza, where the famous KH Market had been located, only about one-third of businesses remained open. It is important to note that the KH Market plaza was culturally important to the research assistants and to Cambodia Town as a whole. As community members ourselves whose families would frequent the plaza to purchase items from the supermarket and other stores within the plaza, we asked, “How will the plaza be changed to serve a different audience?” and, “Why does this need to happen?”. We are already seeing changes being made to the plaza, where an updated, modern-looking Subway has taken its place as a prominent business in a changing plaza. Furthermore, the majority of businesses closed in the plaza were smaller businesses were most likely owned by the ethnic community. As we walked, we discussed several questions: “What does the closure of so many businesses mean for the community in the future? Much empty space remains available for people to use and revamp, but what will be the drawbacks? Will trendier places begin popping up in the area? Will that inevitably draw in more affluent residents and push out those who have lived in the community for years? How does the closure of these culturally significant businesses affect the surrounding community?”

Referring to the Beer Lab in West Long Beach, it has a more modern look with the simple use of three neutral colors: beige, gray, and brown. This look gives the restaurant a more simplistic yet modern aesthetic consistent with more affluent areas. To add to this idea of simplicity and neutrality being today’s new aesthetic, many new and modern buildings had adopted this style by using wood paneling in almost all neighborhoods surveyed. These slabs of dark brown wood were visible in almost every updated modern building we saw and begged the question, “How did this look become the new aesthetic?”. It was visible at the Beer Lab in West Long Beach, Wendy’s and Starbucks in North Long Beach, multiple businesses along the street in West Long Beach, and scattered all over Downtown Long Beach. Could it be because the wood paneling creates a warm and comforting feeling for people, as it reminds them of home? Could it be because these simple slabs of wood reflect the simplicity that is desired in modern trends? Why are businesses updating to reflect this current trend of wood paneling, and for whom? When first looking at the businesses with wood paneling present in their design, it was a bit repetitive, but this is where we noted a commonality between the trendier businesses. During reflections and discussions after all our walks, it felt as if we entered upscale and more affluent areas when the businesses adapted modern aesthetics; we felt as if we were stuck in the past once we were in areas that had smaller and more rundown businesses. This made us wonder, “How does a trend begin? Why do the aesthetics of a business matter so much? If one business adapts modern aesthetics, does the one next door follow suit? Who are these businesses targeting? Who is this development for?”

Uptown Commons in North Long Beach is a new plaza development that was approved in 2018; restaurants began opening in 2020 (Lee 2020; Long Beach Development Services 2018). This plaza seemingly represents what North Long Beach can turn into, as the area has plans for revitalization and hopes to create more business revenue through urban development projects in the near future. Uptown Commons Plaza is the start of the planned future for North Long Beach, as it showcases different types of trendy businesses and a coffee shop that follows the aesthetic of gentrification. The entire plaza has businesses that follow bold colors, and a “natural” feel of wood paneling or plants that makes the establishments feel more elevated and appealing to younger or more affluent populations. This location has also integrated technology, which further proves that Uptown Commons is not appealing to North Long Beach residents but affluent and younger people who have the time, experience, and energy to come to this establishment. Uptown Commons is one of many developments around the city that is catering to younger generations. Once again, we beg the question, “Why and for whom is this development? What are the purposeful and accidental implications of these new developments?”

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Although each neighborhood was different, similar patterns emerged across each area related to greening, technology, and gentrification aesthetics. From investment in e-scooters and bikes to updating and creating more urban parks and greenbelts, we identified greening as extensions of gentrification. We witnessed the use of small green spaces, often built with hostile architecture, as a means to surveil public space and as an anti-homeless strategy. We also found the theme of technology was important, as we saw how access to these new public and private spaces was mediated by the ability to have electronics, smartphone apps, and be technological savvy. From using QR codes to electric scooters and cashless payment, technology has been integrated into urban renewal projects to promote efficiency and eco-friendliness. However, this assumes that all residents have access to cell phones, phone service, and a debit or credit card for payment, along with the knowledge of how to use different applications to access information, goods, and services. Lastly, we identified similar architecture, structures, and items in each neighborhood that we deemed aesthetics of gentrification: modern and clean lines, wood paneling, muted and brightly colored buildings with murals, and trendy coffee shops and restaurants. Along with the presence of electric scooters, we identified gentrification aesthetics of not only art galleries and food trucks but empty shopping plazas and the closing of local “mom and pop” businesses.

In each neighborhood, areas were being redeveloped; however, the changes seem geared towards a younger, hipper new resident, with coffee shops, breweries, and yoga studios replacing ethnic businesses that had catered to immigrant communities. Overall, we found that neighborhoods with immigrants and communities of color in Long Beach are areas where urban development is rapidly changing. Although these changes are injecting much-needed economic investment, the changes do not reflect the needs of long-term immigrant residents. Rather, urban development seems to be geared towards younger, single, childless urban residents with disposable income. As current and past residents of Long Beach, walking and seeing the changes, especially the closure of key businesses, was difficult for the team members. We expressed feelings of displacement, sadness, and exclusion, as redevelopment is happening in a way that does not align with our interests or those of our families. For example, our downtown walks, we stood in front of the closed Chuck E. Cheese, a family chain restaurant and arcade where children’s birthday parties are celebrated. Students talked about hanging out in this exact location with family, and a faculty member reminisced about holding their own child’s birthday party there years ago.

Co-walking offered us a chance to reflect together on the losses and erasures of key sites in neighborhoods and the impact of these changes on sense of community and belonging, which are both critical to the health and well-being of immigrants and residents of color (Gibbons et al. 2018; Hyra et al. 2019).

In this paper, as both residents and outside researchers, we describe two outcomes using co-walking: (1) our observations of how neighborhoods have changed as a result of urban development; and (2) the process of building research team collaboration. Observational co-walking offers an immersive and embodied method to explore urban space as a process of question building and pedagogical mentorship (Pierce and Lawhon 2015). As a data collection process, walking offers researchers a sensory experience of everyday life in “real time” (Irwin 2006), from seeing the sights to hearing the constant din of construction and smelling the food wafting from restaurants. As we walked together, we would interact with each other as we reacted to what we were seeing, hearing, smelling, and feeling. Furthermore, by immersing ourselves in the setting we are studying (Cheng 2014; Jung 2014; Newhouse 2012; Pierce and Lawhon 2015; Sletto and Vasudevan 2021), we are able to see similar patterns across all areas that show the local manifestations of globalization to explain why neighborhoods are changing in order to “develop a new approach to urban planning based on psychogeography to design more and playful urban spaces for the future…” (Jung 2014, p. 624). Thus, the practice of walking helped us develop research questions for a critical community-engaged project. In our process of walking the four neighborhoods, we identified a more critical question for the research project: “Development for whom?”. Furthermore, we drafted questions for future steps of the larger project: “How has cultural globalization helped create an aesthetics of gentrification? How does the use of greening support capital accumulation? What is the consequence of community-member-owned establishments being replaced? How does late-stage capitalism hurt communities like these? How do communities of color perceive this change?”

In addition to being a method for observing neighborhood change, co-walking is also a process for developing research partnerships. Our focus on building team collaboration and challenging power hierarchies ensured that our university team of faculty and students felt confident to share their ideas and conduct research. By using a critical pedagogical approach when working with underrepresented students at a minority-serving institution (Gordon da Cruz 2017; Yosso 2005), we collectively acknowledged the structures of oppression and power relations that have shaped our experiences as people of color in the United States, along with our respective education and college experiences. Often, administrators use a deficit perspective when working with historically excluded student populations (Yosso 2005). However, we recognize that these students do not lack capital; rather, they have a wealth of capital that might not be deemed valuable at first glance (Yosso 2005). We believe that these students and community members hold valuable insight and experiences that are immensely beneficial for research outcomes (Fine and Torre 2019; Yosso 2005). On this project, having students as co-collaborators who were also long-time Long Beach residents gave us different perspectives on neighborhood change from people who were living there. In this vein, they were local experts, and walking provided them a chance to lead data collection and highlight them as key knowledge holders and producers. Co-walking was a collaborative process of co-producing critically conscious knowledge that can empower all team members (Sletto and Vasudevan 2021).

In this study, we ask the question, “How can university-based research teams integrate best practices for building critical community-engaged projects, particularly genuine, authentic research partnerships?”. Developing a critical community-engaged project means first reflecting on the process of “collaboratively developing critically conscious knowledge” and “authentically locating expertise” (Gordon da Cruz 2017), both of which are key components of critical CER. The critical CER approach addresses tensions and structures of power in community–university partnerships in terms of both methods and the overall project outcomes. We argue that observational co-walking as method is an observational and relational process that assists with the foundational steps of building a critical community-engaged research project. This method is especially important in the study of urban spatial changes and the potential impact on city residents as a starting point for building authentic research partnerships for policy-oriented research (Patraporn 2019; Sangalang et al. 2015; Stoecker 1999). Co-walking not only offered a method for a more intimate insight into the material conditions of the city, but it centered and valued the contributions of all team members’ expertise, regardless of rank or experience.

For our team, the process of planning and conducting co-walking facilitated confidence in the students, better communication between team members, and an enduring sense of collaboration and excitement, which has benefitted the next steps of the larger project. Overall, this process helped remedy distrust (Ma et al. 2004; Sandwick et al. 2018) and created strong bonds within the research team (Baum et al. 2006; McIntyre 2014).

Our research is limited by the number of observers and the bias we hold as women and people of color. We also represent a perspective that is younger; thus, what we observe and note may be different than those who are male, white, and older. By detailing these steps, we add to the literature on community-engaged research by demonstrating the reflexive internal process of developing a critical community-engaged project by using innovative methods for building genuine, authentic research partnerships.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.L.; methodology, C.M.L.; formal analysis, C.M.L. and R.V.P.; investigation, C.M.L., K.L. and K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.L., R.V.P., K.L. and K.K.; writing—review and editing, C.M.L., R.V.P., K.L. and K.K.; visualization, K.L. and K.K.; supervision, C.M.L. and R.V.P.; project administration, C.M.L. and R.V.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of California State University, Long Beach (reference #18-362; 10 September 2020) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the CSULB University Research Opportunity Program for their continued support of our undergraduate research assistants, and Jordan Gonzales for the copyediting work on this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Addison, Brian. 2018. Serving Cambodian Community for Decades, Owners of KH Market Given Two Weeks’ Notice Before Hearing on Demolition. Long Beach Post. December 4. Available online: https://lbpost.com/news/cambodia-town-kh-market-gentrification-demolition/ (accessed on 2 June 2021).

- Addison, Brian. 2019. How Black Residents of Long Beach Fought Racist Real Estate Policies and Influenced a Nation. Long Beach Post. April 7. Available online: https://lbpost.com/hi-lo/art/womens-black-history-month-racist-real-estate-policies (accessed on 2 June 2021).

- Anguelovski, Isabelle. 2015. Healthy Food Stores, Greenlining and Food Gentrification: Contesting New Forms of Privilege, Displacement and Locally Unwanted Land Uses in Racially Mixed Neighborhoods. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39: 1209–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguelovski, Isabelle, Margarita Triguero-Mas, James J. T. Connolly, Panagiota Kotsila, Galia Shokry, Carmen Pérez Del Pulgar, Melissa Garcia-Lamarca, Lucia Argüelles, Julia Mangione, Kaitlyn Dietz, and et al. 2020. Gentrification and Health in Two Global Cities: A call to identify impacts for socially-vulnerable residents. Cities & Health 4: 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, Jeremy, Solange Muñoz, Uduak Affiah, Gerónimo Barrera de la Torre, Susanne Börner, Hyunji Cho, Rachael Cofield, Cara Marie DiEnno, Garrett Graddy-Lovelace, Susanna Klassen, and et al. 2022. Displacement of the Scholar? Participatory Action Research Under COVID-19. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 6: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, Fran, Colin MacDougall, and Danielle Smith. 2006. Participatory Action Research. Journal of Epidemiol Community Health 60: 854–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beaulieu, Marianne, Mylaine Breton, and Astrid Brousselle. 2018. Conceptualizing 20 Years of Engaged Scholarship: A Scoping Review. PLoS ONE 13: e0193201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brown, Margaret, and Anne Moyer. 2010. Predictors of Awareness of Clinical Trials and Feelings about the Use of Medical Information for Research in a Nationally Representative US Sample. Ethnicity & Health 15: 223–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campano, Gerald, María Paula Ghiso, and Bethany J. Welch. 2015. Ethical and Professional Norms in Community-Based Research. Harvard Educational Review 85: 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, H. Jacob. 2020. Measuring Displacement: Assessing Proxies for Involuntary Residential Mobility. City & Community 19: 573–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, James Andrew. 2021. Long Beach has a Major Overcrowding Crisis. Available online: https://forthe.org/perspectives/long-beach-overcrowding-crisis/ (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Cheng, Yi’En. 2014. Telling Stories of the City: Walking Ethnography, Affective Materialities, and Mobile Encounters. Space and Culture 17: 211–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curnow, Joe. 2017. Challenging the Empowerment Expectation: Learning, Alienation and Design Possibilities in Community University Research. Gateways: Internal Journal of Community Research and Engagement 10: 229–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Curran, Winifred. 2018. “Mexicans love red” and Other Gentrification Myths: Displacements and Contestations in the gentrification of Pilsen, Chicago, USA. Urban Studies 55: 1711–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmond, Matthew. 2016. Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City. New York: Broadway Books. [Google Scholar]

- Downtown Plan. 2012. City of Long Beach. Available online: https://www.longbeach.gov/globalassets/lbds/media-library/documents/planning/advance/downtown/downtownplan_sections-1-2-reduced (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Fine, Michelle, and María Elena Torre. 2019. Critical Participatory Action Research: A Feminist Project for Validity and Solidarity. Psychology of Women Quarterly 43: 433–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, Kevin. 2022. The Downtown Plan: 10 Years of Rent Hikes & Displacements. Available online: https://forthe.org/journalism/downtown-plan-10-years/ (accessed on 22 January 2022).

- George, Sheba, Nelida Duran, and Keith Norris. 2014. A Systematic Review of Barriers and Facilitators to Minority Research Participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. American Journal of Public Health 104: e16–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbons, Joseph, Michael Barton, and Elizabeth Brault. 2018. Evaluating Gentrification’s Relation to Neighborhood and City Health. PLoS ONE 13: e0207432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gordon da Cruz, Cynthia. 2017. Critical Community-Engaged Scholarship: Communities and Universities Striving for Racial Justice. Peabody Journal of Education 92: 363–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, David. 2012. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. New York: Verso Books. [Google Scholar]

- Housing Element. 2021. City of Long Beach General Plan. Available online: https://longbeach.gov/globalassets/lbds/media-library/documents/planning/housing-element-update/proposed-2021-2029-housing-element--6th-cycle----released-11-5-21 (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Hyra, Derek. 2015. Greasing the Wheels of Social Integration: Housing and Beyond in Mixed-Income, Mixed-Race Neighborhoods. Housing Policy Debate 25: 785–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyra, Derek, Dominic Moulden, Carley Weted, and Mindy Fullilove. 2019. A Method for Making the Just City: Housing, Gentrification, and Health. Housing Policy Debate 29: 421–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hytrek, Gary. 2019. Space, Power, and Justice: The Politics of Building an Urban Justice Movement, Long Beach, California, USA. Urban Geography 41: 736–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, Rita L. 2006. Walking to Create an Aesthetic and Spiritual Currere. Visual Arts Research 32: 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Yuha. 2014. Mindful Walking: The Serendipitous Journey of Community-Based Ethnography. Qualitative Inquiry 20: 621–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Hunter. 2020. Uptown Commons Welcomes Two New Restaurants to North Long Beach. Press Telegram. September 5. Available online: https://www.presstelegram.com/2020/09/05/uptown-commons-welcomes-two-new-restaurants-to-north-long-beach/ (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Long Beach Census Tracts. 2010. 2010 Census Tract Boundaries, City of Long Beach, California. Available online: https://www.longbeach.gov/globalassets/ti/media-library/documents/gis/map-catalog/2010censustracts (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Long Beach Development Services. 2018. 2018 In Review Planning Commission. City of Long Beach Development Service Department. Available online: https://www.longbeach.gov/globalassets/lbds/media-library/documents/publications/annual-reports/planning-commission-2018-in-review-mobile (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Long Beach Health and Human Services. 2022. Timeline of Racial Inequities in Long Beach. City of Long Beach. Available online: https://longbeach.gov/health/healthy-living/office-of-equity/reconciliation/equity-timeline/ (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Long Beach Housing and Neighborhood Services. 2022. Available online: https://longbeach.gov/lbds/hn/srtd/?s=03 (accessed on 22 January 2022).

- Long Beach publiCity. 2021. City of Long Beach Development Service Department. Available online: https://long-beach-ca-publicity.tolemi.com/ (accessed on 22 January 2022).

- Ma, Grace X., Jamil I. Toubeeh, Xuefen Su, and Rosita L. Edwards. 2004. ATECAR: An Asian American Community-Based Participatory Research Model on Tobacco and Cancer Control. Health Promotion Practice 5: 382–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, Alice. 2014. Participatory Action Research. Thousands Oak: Sage. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, Wendy, Jacque Gingras, Pamela Robinson, and Janice Waddell. 2014. Community-University Research Partnerships: A Role for University Research Centers? Community Development 45: 165–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkler, Meredith, and Nina Wallerstein. 2008. Community-Based Participatory Research: From Process to Outcomes. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Munguia, Hayley. 2019. The Press-Telegram’s new interactive map will help you see the scope of Long Beach’s development boom, a phenomenon decades in the making. Long Beach Press-Telegram. April 7. Available online: https://www.presstelegram.com/2019/04/07/the-press-telegrams-new-interactive-map-will-help-you-see-the-scope-of-long-beachs-development-boom-a-phenomenon-decades-in-the-making/ (accessed on 2 June 2021).

- Nation, Maury, Kimberly Bess, Adam Voight, Douglas D. Perkins, and Paul Juarez. 2011. Levels of Community Engagement in Youth Violence Prevention: The Role of Power in Sustaining Successful University-Community Partnerships. American Journal of Community Psychology 48: 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newhouse, Léonie S. 2012. Footing It, or Why I Walk. African Geographical Review 31: 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niebla, Crystal. 2021. “A holder of culture”: Cambodia Town’s KH Market to Close by the End of May. Long Beach Post. Available online: https://lbpost.com/news/a-holder-of-culture-cambodia-towns-kh-market-to-close-by-the-end-of-may (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Patraporn, R. Varisa. 2019. Serving the People in Long Beach, California: Advancing Justice for Southeast Asian Youth through Community University Research Partnerships. AAPI Nexus Journal: Policy, Practice and Community 16: 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, Joseph, and Mary Lawhon. 2015. Walking as Method: Toward Methodological Forthrightness and Comparability in Urban Geographical Research. The Professional Geographer 67: 655–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preis, Benjamin, Aarthi Janakiraman, Alex Bob, and Justin Steil. 2021. Mapping Gentrification and Displacement Pressure: An Exploration of Four Distinct Methodologies. Urban Studies 58: 405–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sandwick, Talia, Michelle Fine, Andrew Cory Greene, Brett G. Stoudt, María Elena Torre, and Leigh Patel. 2018. Promise and Provocation: Humble Reflections on Critical Participatory Action Research for Social Policy. Urban Education 53: 473–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangalang, Cindy, Suely Ngouy, and Anna S. Lau. 2015. Using Community Based Participatory Research to Identify Health Issues for Cambodian American Youth. Family and Community Health 38: 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sletto, Bjørn, and Raksha Vasudevan. 2021. Walking with Youth in Los Platanitos: Learning Mobilities, Youth Inclusion, and Co-production in International Planning Studios. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoecker, Randy. 1999. Are Academics Irrelevant? Roles for Scholars in Participatory Research. American Behavioral Scientist 42: 840–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban Displacement Project. 2021a. Los Angeles Story Map: Long Beach. Available online: https://www.urbandisplacement.org/maps/los-angeles-story-map/ (accessed on 22 January 2022).

- Urban Displacement Project. 2021b. Available online: https://www.urbandisplacement.org/maps/los-angeles-gentrification-and-displacement/ (accessed on 22 January 2022).

- US Census Bureau. 2010. American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates Subject Tables. Available online: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=foreign%20born&g=1600000US0643000&y=2010&tid=ACSST5Y2010.S0502 (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- US Census Bureau. 2019a. American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates Data Profiles. Available online: https://api.census.gov/data/2019/acs/acs1/profile (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- US Census Bureau. 2019b. American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates Data Profiles. Available online: https://api.census.gov/cedsci/ (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- US Census Bureau. 2019c. American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates Subject Tables. Available online: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=S0502%3A%20SELECTED%20CHARACTERISTICS%20OF%20THE%20FOREIGN-BORN%20POPULATION%20BY%20PERIOD%20OF%20ENTRY%20INTO%20THE%20UNITED%20STATES&g=1600000US0643000&y=2019&tid=ACSST5Y2019.S0502 (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- Yosso, Tara J. 2005. Whose Culture Has Capital? A Critical Race Theory Discussion of Community Cultural Wealth. Race Ethnicity and Education 8: 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).