Art and Identity in Late Antique Synagogues of the Roman-Byzantine Diaspora

Abstract

:Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| BASOR | The Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research |

References

- Ameling, Walter. 2004. Inscriptiones Judaicae Orientis, II: Kleinasien. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Avi-Yonah, Michael. 1960. The Mosaic Pavement of Ma’on (Nirim). Louis M. Rabinowitz Fund Bulletin 3: 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Balty, Janine. 1995. Une nouvelle mosaïque du IVe siècle dans l’édifice dit “au triclinos” à Apamée. In Mosaïques Antiques du Proche-Orient: Chronologie, Iconographie, Interpretation. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, pp. 177–90. [Google Scholar]

- Barag, Dan, Yosef Porat, and Ehud Netzer. 1981. The Synagogue at En-Gedi. In Ancient Synagogues Revealed. Edited by Lee Israel Levine. Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society, pp. 116–19. [Google Scholar]

- Baramki, Dimitri. 1938. An Early Byzantine Synagogue near Tell Es-Sultan. Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine 6: 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Boin, Douglas. 2013. Ostia in Late Antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Balty, Janine. 1991. La mosaïque romaine et byzantine en Syrie du Nord. Revue du Monde Musulman et de la Méditerranée 62: 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, Nadin. 2014. Uncomparable Buildings? The Synagogues in Priene and Sardis. Journal of Ancient Judaism 5: 167–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonz, Marianne Palmer. 1993. Differing Approaches to Religious Benefaction: The Late Third-Century Acquisition of the Sardis Synagogue. Harvard Theological Review 86: 139–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botermann, Helga. 1990. Die Synagoge von Sardes: Eine Synagoge aus dem 4. Jahrhundert? Zeitschrift für die Neutestamentliche Wissenschaft 81: 103–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, Scott, ed. 1996. Severus of Minorca: Letter on the Conversion of the Jews. Oxford: Clarendon. [Google Scholar]

- Brenk, Beat. 1991. Die Umwandlung der Synagoge von Apamea in eine Kirche. TESSERAE.Festschrift für Joseph Engemann. Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum. Ergänzungsband 18: 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Brooten, Bernadette. 1982. Women Leaders in the Ancient Synagogue: Inscriptional Evidence and Background Issues. Chico: Scholars Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buckler, William Hepburn, and David Moore Robinson. 1932. Sardis VII: I, Greek and Latin Inscriptions. Leyden: American Society for the Excavation of Sardis. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt, Nadin, and Mark Wilson. 2013. The late antique Synagogue in Priene: Its History, Architecture, and Context. Gephyra 10: 166–96. [Google Scholar]

- Cevik, Nevzat, Ozgu Comezoglu, Hüseyin Sami Öztürk, and Inci Turkoglu. 2010. Unique Discovery in Lycia: The Ancient Synagogue at Andriake, Port of Myra. Adalya 13: 335–66. [Google Scholar]

- Chaniotis, Angelos. 2002. The Jews of Aphrodisias: New Evidence and Old Problems. Scripta Classica Israelica 21: 209–42. [Google Scholar]

- Colafemmina, Cesare. 2012. The Jews in Calabria, a Documentary History of the Jews in Italy 33. Brill: The Goren-Goldstein Diaspora Research Centre, Tel Aviv University, Leiden. [Google Scholar]

- Costamagna, Liliana. 1991. La sinagoga di Bova Marina nel quadro degli insediamenti tardoantichi della costa Ionica meridionale della Calabria. Mélanges de l’école française de Rome 103: 611–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costamagna, Liliana. 1994. La sinagoga di Bova Marina. In Architettura Judaica in Italia: Ebraisimo, sito, Memoriadei Loughi. Edited by R. La Franca. Palermo: Flaccovio Editore, pp. 239–45. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrova, Elizabeta, Silvana Blaževska, and Miško Tutkovski. 2012. Early Christian Wall Paintings from the Episcopal Basilica in Stobi. Stobi: National Institution Stobi. [Google Scholar]

- Dothan, Moshe. 1983. Hammath Tiberias—Early Synagogues and the Hellenistic and Roman Remains (Final Excavation Report: I). Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Drbal, Vlastimil. 2009. Socrates in late antique Art and Philosophy: The Mosaic of Apamea. Series Byzantina 7: 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbabin, Katherine M. D. 1999. Mosaics of the Greek and Roman World. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dvorjetski, Estēe. 2005. The Synagogue-Church at Gerasa in Jordan. A Contribution to the Study of Ancient Synagogues. Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 121: 140–67. [Google Scholar]

- Engemann, Josef. 1968–1969. Bemerkungen zu römischen Gläsern mit Goldfoliendekor. Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum 11/12: 7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Fantar, Mounir. 2009. Sur la découverte d’un espace cultuel juif à Clipea (Tunisie). Comptes Rendus des Séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 153: 1083–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, Louis Harry. 1993. Jew and Gentile in the Ancient World: Attitudes and Interactions from Alexander to Justinian. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, Steven. 1997. This Holy Place: On the Sanctity of the Synagogue during the Greco-Roman Period. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, Steven. 2005. Liturgy and the Art of the Dura Europos Synagogue. In Liturgy in the Life of the Synagogue: Studies in the History of Jewish Prayer. Edited by R. Langer and S. Fine. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 41–71. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, Steven, and Leonard Rutgers. 1996. New Light on Judaism in Asia Minor during late antiquity: Two Recently Identified Inscribed Menorahs. Jewish Studies Quarterly 3: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Fraade, Steven, D. 2019. Facing the Holy Ark: In Words and in Images. Near Eastern Archaeology 82: 156–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksen, Paula. 2016. ‘If It Looks like a Duck, and It Quacks like a Duck …’ On Not Giving up the Godfearers. In A Most Reliable Witness: Essays in Honor of Ross Shepard Kraemer. Edited by Susan Ashbrook Harvey, Nathaniel DesRosiers, Shira L. Lander, Jacqueline Pastis and Daniel Ullucci. Providence: Brown Judaic Series, pp. 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hachlili, Rachel. 1998. Ancient Jewish Art and Archeology in the Diaspora. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Hachlili, Rachel. 2010. The Dura-Europos Synagogue Wall Paintings: A Question of Origin and Interpretation. In Follow the Wise: Studies in Jewish History and Culture in Honor of Lee I. Levine. Edited by Zeev Weiss, Oded Irshai, Jodi Magness and Seth Schwartz. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 403–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hachlili, Rachel. 2018. The Menorah: Evolving into the Most Important Jewish Symbol. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Hanfmann, George M. A. 1967. The Ninth Campaign at Sardis. BASOR 187: 9–32, 50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hanfmann, George Maxim Anossov, and Nancy Hirschland Ramage. 1978. Sculpture from Sardis: The Finds through 1975. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, Edward D. 1982. St. Stephen in Minorca: An Episode in Jewish—Christian Relations in the Early 5th Century A.D. The Journal of Theological Studies 33: 106–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilan, Zvi. 1991. Ancient Synagogues in Israel. Tel Aviv: Ministry of Defense. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, Herbert Leon. 2000. The Sepphoris Mosaic and Christian art. In From Dura to Sepphoris: Studies in Jewish Art and Society in late Antiquity. Edited by Lee Israel Levine and Zeev Weiss. Portsmouth: Journal of Roman Archaeology, pp. 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kiperwasser, Reuven, and Serge Ruzer. 2013. The Holy Land and Its Inhabitors in Travel Stories of Bar-Sauma. Cathedra 148: 41–70. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Kolarik, Ruth. 2014. Synagogue Floors from the Balkans Religious and Historical Implications. Niš and Byzantium 12: 115–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kraabel, Alf Thomas. 1979. The Diaspora Synagogue: Archeological and Epigraphic Evidence since Sukenik. In Aufstieg und Niedergang der Romischen Welt, II, 19.1. Edited by Hildegard Temporini and Wolfgang Haase. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter, pp. 477–510. [Google Scholar]

- Kraeling, Carl Hermann. 1979. The Synagogue: The Excavations at Dura-Europos, Final Report VIII/I. New Haven: Yale University Press, New York: Ktav Pub. House. [Google Scholar]

- Kroll, John H. 2001. The Greek Inscriptions of the Sardis Synagogue. Harvard Theological Review 94: 5–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, Doro. 1947. Antioch Mosaic Pavements. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, Lee Israel. 2005. The Ancient Synagogue: The First Thousand Years. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, Lee Israel. 2012. Visual Judaism in late Antiquity. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Linder, Amnon. 1987. The Jews in Roman Imperial Legislation. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. [Google Scholar]

- Magness, Jodi. 2005. The Date of the Sardis Synagogue in Light of the Numismatic Evidence. American Journal of Archaeology 109: 443–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magness, Jodi, Shua Kisilevitz, Matthew Grey, Dennis Mizzi, Daniel Schindler, Martin Wells, Karen Britt, Ra’anan Boustan, Shana O’Connell, Emily Hubbard, and et al. 2018. The Huqoq Excavation Project: 2014–17 Interim Report. BASOR 380: 61–131. [Google Scholar]

- Majewski, Lawrence J. 1967. Evidence for the Interior Decoration of the Synagogue. BASOR 187: 32–50. [Google Scholar]

- Matassa, Lidia D. 2018. Invention of the First-Century Synagogue. Edited by Jason M Silverman and Murray Watson. Atlanta: SBL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mayence, Fernand. 1935. La quatrième campagne de fouilles à Apamée. l’Antiquité Classique 4: 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayence, Fernand. 1939. La VIe campagne de fouilles à Apamée. l’Antiquité Classique 8: 201–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoleone-Lemaire, Jacqueline, and Jean Charles Balty. 1969. L’église à Atrium de la Grande Colonnade. Bruxelles: Centre Belge de recherches archéologiques à Apamée de Syrie. [Google Scholar]

- Nau, François. 1927. Deux épisodes de l‘histoire juive sous Theodose II (423–438) d’après la vie de Barsauma le Syrien. Revue des Études Juives 83: 184–206. [Google Scholar]

- Netzer, Ehud, and Gideon Foerster. 2005. The Synagogue at Saranda, Albania. Qadmoniot 129: 45–53. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Noga-Banai, Galit. 2008. Between the Menorot: New Light on a Fourth Century Jewish Representative Composition. Viator 39: 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noy, David. 1993. Jewish Inscriptions of Western Europe, I: Italy, Spain and Gaul. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Noy, David. 1995. Jewish Inscriptions of Western Europe, II: The City of Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Noy, David, and Susan Sorek. 2003. ‘Peace and Mercy upon all your Blessed People’: Jews and Christians at Apamea in late antiquity. Jewish Culture and History 6: 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Noy, David, Alexander Panayotov, and Hanswulf Bloedhorn. 2004. Inscriptiones Judaicae Orientis, I: Eastern Europe. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Ovadia, Asher. 1981. The Synagogue at Gaza. In Ancient Synagogues Revealed. Edited by Lee I. Levine. Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society, pp. 129–31. [Google Scholar]

- Panayotov, Alexander. 2004. The Jews in the Balkan Provinces of the Roman Empire: The Evidence from the Territory of Bulgaria. In Negotiating Diaspora: Jewish Strategies in the Roman Empire. Edited by John Martyn Gurney Barclay. London: T & T Clark International, pp. 38–65. [Google Scholar]

- Parkes, James. 1961. Conflict of the Church and the Synagogue: A Study in the Origins of Antisemitism. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society. [Google Scholar]

- Rajak, Tessa. 2006. The Jewish Diaspora. In Cambridge History of Christianity, I. Edited by Margaret M. Mitchell and Frances M. Young. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Rautman, Marcus. 2010. Daniel at Sardis. BASOR 358: 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautman, Marcus. 2015. A menorah Plaque from the Center of Sardis. Journal of Roman Archaeology 28: 431–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth-Gerson, Leah. 2001. The Jews of Syria as Reflected in the Greek Inscriptions. Jerusalem: The Zalman Shazar Center for Jewish History. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Rutgers, Leonard Victor. 1995. The Jews in Late Ancient Rome: Evidence of Cultural Interaction in the Roman Diaspora. Leiden: E.J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Rutgers, Leonard Victor. 1996. Diaspora Synagogues: Synagogue Archeology. In Sacred Realm: The Emergence of the Synagogue in the Ancient World. Edited by Steven Fine. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 67–95. [Google Scholar]

- Rutgers, Leonard Victor. 1998. The Hidden Heritage of Diaspora Judaism. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Seager, Andrew R. 1972. The Building History of the Sardis Synagogue. American Journal of Archeology 76: 425–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seager, Andrew R., and Alf Thomas Kraabel. 1983. The Synagogue and the Jewish Community. In Sardis from Prehistoric to Roman Times: Results of the Archaeological Exploration of Sardis 1958–75. Edited by George Maxim Anossov Hanfmann. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 169–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard, A. R. R. 1979. Jews, Christians and Heretics in Acmonia and Eumenia. Anatolian Studies 29: 169–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukenik, Eleazar Lipa. 1932. The Ancient Synagogue of Beth Alpha. Jerusalem: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sukenik, Eleazar Lipa. 1935. The Ancient Synagogue of El-Hammeh. Jerusalem: R. Mass. [Google Scholar]

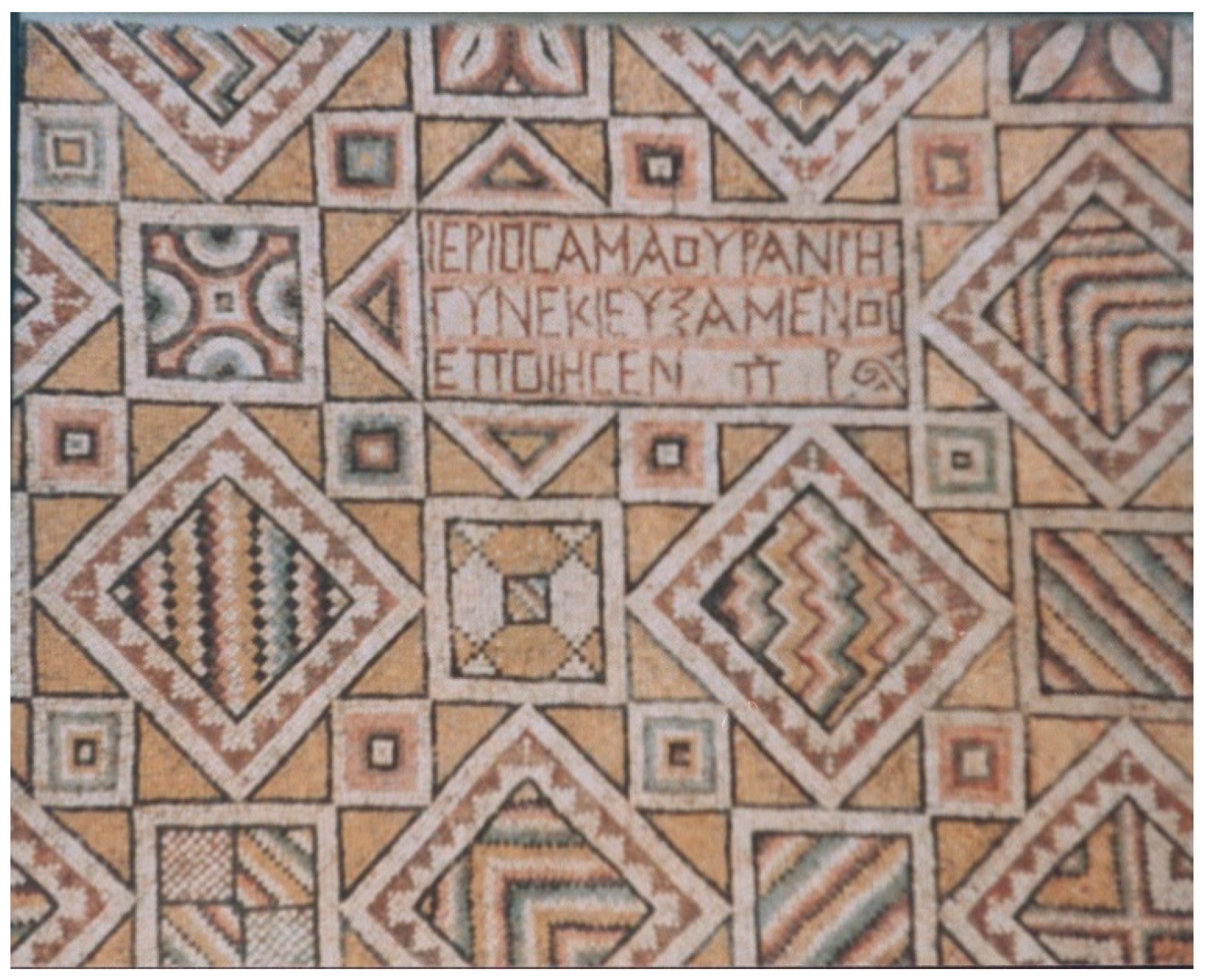

- Sukenik, Eleazar Lipa. 1950–1951. The Mosaic Inscriptions in the Synagogue at Apamea on the Orontes. The Hebrew Union College Annual 23: 541–51. [Google Scholar]

- Talgam, Rina. 2014. Mosaics of Faith: Floors of Pagans, Jews, Samaritans, Christians, and Muslims in the Holy Land. Jerusalem: Yad Ben-Zvi Press, University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tzaferis, Vassilios. 1982. The Ancient Synagogue at Ma’oz Hayyim. Israel Exploration Journal 32: 215–44. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoogen, Violette. 1964. Apamée de Syrie aux Musées Royaux d’art et D’histoire. Bruxelles: M. Weissenbruch. [Google Scholar]

- Villey, Thomas. Forthcoming. La question de la licéité des images dans le judaïsme ancien à travers l’exemple des pavements en mosaïque de deux synagogues africaines. In Actes de la Table Ronde Image et Droit: Le Droit aux Images, Rome, 2–3 Décembre 2013. forthcoming.

- Walsh, Robyn Faith. 2016. Reconsidering the Synagogue/Basilica of Elche, Spain. Jewish Studies Quarterly 23: 91–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, Zeev. 2005. The Sepphoris Synagogue. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, Ze’ev. 2016. Decorating the Sacred Realm: Biblical Depictions in Synagogues and Churches of Ancient Palestine. In Jewish Art in Its Late Antique Context. Edited by U. Leibner and C. Hezser. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, pp. 121–68. [Google Scholar]

- Weitzmann, Kurt, and Herbert Kessler. 1990. The Frescoes of the Dura Synagogue and Christian Art. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks. [Google Scholar]

- Werlin, Steven. 2015. Southern Palestine, 300–800 C.E.: Living on the Edge. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- White, L. Michael. 1990. Building God’s House in the Roman World: Architectural Adaptation among Pagans, Jews, and Christians. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- White, L. Michael. 1997. Synagogue and Society in Imperial Ostia: Archaeological and Epigraphic Evidence. Harvard Theological Review 90: 23–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilken, Robert Louis. 1983. John Chrysostom and the Jews: Rhetoric and Reality in the Late 4th Century. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yegül, Fikret K. 1986. The Bath-Gymnasium Complex at Sardis. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Some scholars classify Gerasa as a Diasporan synagogue; however, I believe there is a clear affinity between the synagogues in the provinces of Palestine and Arabia, including Gerasa and the synagogue at Naveh in the Hauran, Moreover, the mosaic floor at the synagogue of Gerasa (and the church above it) appertains to a regional artistic tradition of mosaic floors in synagogues and churches in the provinces of Palestine and Arabia. See (Talgam 2014, pp. 319–22). Therefore, I have defined ‘Diaspora’ as the area outside of these provinces. Unfortunately, I do not address the Babylonian diaspora in this article as hitherto not a single synagogue has been uncovered in this region. See (Levine 2005, pp. 286–91). |

| 2 | For several key studies that include additional references, see (Kraeling 1979; Weitzmann and Kessler 1990; Fine 2005; Hachlili 2010; Levine 2012, pp. 97–118). |

| 3 | For collections of Jewish inscriptions from the various regions, see (Noy 1993, 1995; Noy et al. 2004; Ameling 2004). See also (Rutgers 1995; Panayotov 2004). For the map of the Jewish diaspora based on archeological finds and literary evidence, published by Haifa University’s Jewish Diaspora mapping project, see: https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/viewer?mid=1fiMBoXPJrqzEV-5PU0dKMVMbQbk&ll=32.46113771566362%2C27.950343482299445&z=4. |

| 4 | The Jewish identity of the building is still disputed, see (Matassa 2018, pp. 37–77). |

| 5 | However, it seems that at the time of the Ostia synagogue’s construction the area along the seashore was settled and active. See (White 1997, pp. 27–28; Boin 2013, pp. 119–20). |

| 6 | |

| 7 | Mosaic carpets did not adorn the synagogues at Delos, Dura Europos, Priene and Andriake, though only the last two were operational in the Byzantine period, when, under Christian influence, mosaic carpets became a prominent decorative medium in synagogues. The main decorative medium in the synagogues of Priene and Andriake is the sculptural medium, mainly carved marble slabs. See (Burkhardt and Wilson 2013, pp. 177–78; Cevik et al. 2010, pp. 341–44). |

| 8 | |

| 9 | This mosaic evokes women’s special status in the community: the inscriptions mention eight women as independent donors and mentions the others with their husbands. According to the inscriptions, they financed the installation of over half the carpet. On dedicatory inscriptions that reference female donors to antique synagogues, see (Brooten 1982, pp. 157–65). |

| 10 | |

| 11 | See (Balty 1991; Dunbabin 1999, pp. 176–86). |

| 12 | See (Verhoogen 1964, p. 16). |

| 13 | |

| 14 | |

| 15 | As such, the northwestern entrance was obviously the main entrance. Excavators found an intact amphora and fragments of other amphorae in a room adjoining the prayer hall, indicating its possible use as a storeroom for food. Two amphorae handles stamped with menorahs attest the amphorae’s use by community members. A pitcher containing over 3000 bronze coins, dated mostly to the 5th century, was found in another room. See (Colafemmina 2012, pp. 2–3). |

| 16 | |

| 17 | (See (Costamagna 1991, p. 628; 1994, p. 243). |

| 18 | The excavators identify four architectural phases of the building, the fourth an uncontrovertibly Jewish structure, and the third debatably so. Magness, by contrast, suggested that the synagogue was established as late as the mid-6th century. See (Seager 1972, pp. 433–35; Botermann 1990; Bonz 1993; Magness 2005). |

| 19 | An inscription that enumerates the city’s public fountains mentions ‘the synagogue’s fountain’: συναγωγῆ [ς κρήνη—]. If indeed this is the said fountain, it appears to have serviced not just the Jewish community but rather all the city’s inhabitants. See (Buckler and Robinson 1932, pp. 37–40). |

| 20 | |

| 21 | |

| 22 | See (Hanfmann and Ramage 1978, pp. 63–65, figs. 92–101 [lions], pp. 148–49, figs. 379–82 [table of eagles]). For a discussion regarding the significance of these spolia objects in the prayer hall, see (Levine 2012, pp. 304–6). |

| 23 | |

| 24 | See (Seager 1972, p. 435). |

| 25 | Additional mosaic fragments that are identified with this phase are mostly geometric and decorative. See (Netzer and Foerster 2005, pp. 47–49). |

| 26 | See (ibid., pp. 49–53). |

| 27 | Anthropomorphic images are completely absent from Diasporan Jewish art of the Byzantine period, yet manifest extensively in the frescoes at Dura Europos from the mid-3rd century. An exception is a small engraving depicting the biblical story of Daniel in the lion’s den discovered at the Sardis synagogue; see below, note 53. |

| 28 | Hachlili argues that the menorah appears frequently alongside the lulav and ethrog in Diasporan synagogues and much less often alongside the shofar. See (Hachlili 1998, p. 354; 2018, pp. 133–35). |

| 29 | See (Panayotov 2004, pp. 41–45). |

| 30 | See (Fantar 2009, p. 1085, fig. 2). |

| 31 | See (Walsh 2016, pp. 96–99). |

| 32 | See (Hachlili 1998, pl. II: 9–10). |

| 33 | Most of the artistic works were found in the prayer hall, and several in the forecourt and in the stores near the synagogue. Recently, Marcus Rautman published a marble slab engraved with a menorah flanked by a lulav and an ethrog that was uncovered at the city’s center (field 55). See (Burkhardt 2014, p. 198; Rautman 2015). |

| 34 | See (Hachlili 1998, p. 236). |

| 35 | See (Balty 1995, pp. 177–90, pl. XVIII: 1–2). This is the plate’s number. In Levi 1947 (below), vol I is text, and vol. II is plates. |

| 36 | See in the 4th century mosaic carpet from the Yakto Complex in Daphne, near Antioch (Levi 1947, vol. I, pp. 280–81; vol. II, pl. 111: a), as well as in the 5th century mosaic from the ‘House of Ge and Season’ in Daphne, where a protome of a female personification populates the central medallion (ibid., vol. I, pp. 346–47; vol. II, pl. 82: a). Of the ties between the Jewish communities of Antioch and Apamea we can learn from two dedicatory inscriptions from the synagogue that mention the donation of ‘Ilasios (son) of Isakios, archisynagogos of the Antiochians’. See: (Roth-Gerson 2001, pp. 54, 57). |

| 37 | See (Kolarik 2014, pp. 118–19). |

| 38 | |

| 39 | |

| 40 | |

| 41 | See (Drbal 2009). |

| 42 | Boin suggests that he is an umpire or a trainer, see (Boin 2013, pp. 61–62). |

| 43 | The same phenomenon appears in frescoes in Stobi: geometric mosaic carpets decorated the Episcopal Basilica—built during the first half of the 4th century, and considered the earliest church in Macedonia, The remains of the fresco found in the Church and in the nearby baptistery reveal figural depictions that adorned the walls as early as the 4th century. By contrast, remains of the fresco and stucco from the walls of the city’s synagogue are devoid of figural motifs. See (Dimitrova et al. 2012). |

| 44 | It is noteworthy that geometric aniconic carpets also adorned Roman and Byzantine structures during the 4th and 5th centuries: in Jewish society, however, they became the default due to reservations concerning figural art. |

| 45 | This is the case with Hammath Tiberias stage Ia, see (Dothan 1983, pp. 37, 93; Talgam 2014, p. 406), Jericho, see (Baramki 1938; Werlin 2015, pp. 72–84), and the late mosaic carpet in the center of the prayer hall in Susiya, see (Werlin 2015, pp. 152–54). The third stage of the mosaic carpet in Ma’oz Hayyim is aniconic as well, although it is dated prior to the Moslem conquest, see (Tzaferis 1982, pp. 223–27). Limited use of animal figures is evident in two additional mosaic carpets, in the synagogues of Ein Gedi and Hammath Gader. See (Barag et al. 1981, p. 119; Sukenik 1935, pp. 35–38). |

| 46 | Out of 26 mosaic carpets, 16 include images, four are aniconic and two present very few images (Ein Gedi and Hammath Gader). Another four mosaics were uncovered in a partial state that precludes their evaluation. |

| 47 | |

| 48 | |

| 49 | In Huqoq only the season of Autumn has survived, and for the first time, the season is depicted as a male figure. See (Magness et al. 2018, p. 100, fig. 37 [Huqoq]; Ilan 1991, p. 315 [Susiya]). |

| 50 | See (Weiss 2005, p. 105, fig. 46). |

| 51 | See (ibid., p. 119, fig. 61). |

| 52 | |

| 53 | On Dura Europos see above, note 2. Several years ago, another depiction of a biblical scene from a Diasporan synagogue, that of Sardis, was published. On three fragments of a gray marble slab is an engraving of a figure confronting four lions. The depiction was identified as Daniel in the lions’ den—a familiar biblical motif in Palestinians’ synagogue décor. That said, it should be noted that the marble fragments were found in a corner of the peristyle forecourt, together with artifacts dating to the early 7th century, and their context in the space of the synagogue is not very clear. See (Rautman 2010). |

| 54 | |

| 55 | |

| 56 | Several marble plaques from various sites in Asia Minor that portray two spirals under the branches of a menorah - on either side of the central branch allude to the liturgical context. Fine and Rutgers propose that these images represent the synagogue scrolls, while their incorporation in the depiction of the menorah creates a strong affinity between the menorah of the Temple and the Torah scrolls of the synagogue, and is a visual expression of the conception of the synagogue as a ‘lesser sanctuary’. See (Fine and Rutgers 1996, pp. 12–17; Cevik et al. 2010, pp. 341–43). |

| 57 | This panel appears in Hammath Tiberias, Sephorris, Beit Alpha, Na’aran, and the Samaritan synagogue at Beit She’an. In Susiya two gazelles flank the menorahs. |

| 58 | For the affinity between the Ark of the Covenant and the Torah Shrine in rabbinic literature and late antique Jewish art, see (Fraade 2019). |

| 59 | B. Megillah 29a. |

| 60 | Noga-Banai discerns the historical background of this composition’s simultaneous appearance in the synagogue of Hammath Tiberias and in the Jewish Roman catacombs, during the second half of the 4th century. See (Noga-Banai 2008). If Talgam is correct in her assumption that during the 5th–6th century this panel’s context related to a Jewish-Christian polemic, then its absence from the Diasporan synagogues is quite clear, similar to the argument above in relation to the biblical depictions. See (Talgam 2014, pp. 266–68, 303–14). |

| 61 | |

| 62 | See below, note 66. |

| 63 | Various attestations indicate that members of the Jewish community held offices in the municipal administration. At Sardis, nine community members held the title βουλευτής, member of the city council, and three others held offices in the imperial provincial administration, see (Kroll 2001, p. 10). A funerary inscription from arcosolium D7 in Venosa mentions two people holding the office of Maiores civitatis that is generally understood as civic leaders, see (Noy 1993, p. 119). Severus of Minorca’s Letter on the Conversion of the Jews also elicits this conclusion. He depicts a reality whereby Jews held key political and social posts in the city of Magona, at the eastern end of the island of Minorca, at the beginning of the 5th century. See (Bradbury 1996, pp. 25–43). |

| 64 | Most famous of this evidence is the dedicatory inscription of Aphrodisias from Asia Minor, dated to the 4th or 5th century that includes the names of 54 God fearers (in addition to 68 Jews and three gentiles), some of whom members of the city council, who donated to the Jewish community. The sermons of John Chrystosom against members of his community whom he accused of Judaizing attest to the appeal of Judaism to Christians during the late 4th century in Antioch. Similar warnings appear in the writings of Origen, Ephrem the Syrian and others. The literature on this issue is very extensive; the following are some key studies that include additional bibliography. See (Sheppard 1979; Wilken 1983, pp. 66–94; Feldman 1993, pp. 383–415; Rutgers 1998, pp. 219–24; Chaniotis 2002, pp. 226–32; Levine 2005, pp. 292–99; Rajak 2006, pp. 63–65; Fredriksen 2016). |

| 65 | Rutgers proposes a cause and effect connection between the two phenomena: the stable and secure status of the Jewish communities throughout the Roman Empire during the first centuries CE, and the prominence of the synagogues in the municipal fabric, provoked hostility towards them. This hostility was explicit both in the legal realm – in the laws of Theodosius directed against the synagogues—and in the practical realm, in their physical destruction and their conversion into churches. See (Rutgers 1998, pp. 119–21; Linder 1987, pp. 73–74). |

| 66 | Literary sources shed light on synagogues that were destroyed by Christians, such as those at Rome, Edessa, Callinicum on the Euphrates, Rabat Moab (Areopolis) and Alexandria, as well as synagogues that were converted into churches at Magona (Minorca), Ravenna and Dertona (Italy), Tipasa (Algeria) and Antioch. See (Parkes 1961, pp. 166–68, 187, 204–7, 212–14, 236–38, 244, 263–64; Hunt 1982; Noy and Sorek 2003, pp. 20–22). At the same time, there were strong communities that managed to persist and even thrive, as therenovations conducted at the synagogues of Sardis and Ostia during the 5th and 6th centuries attest. |

| 67 | The closest sites that were damaged are in Transjordan: Gerasa, where in 530/1, a church was built atop the synagogue of the 4th and 5th centuries and the synagogue, and Rabat Moab that, according to historical sources, was destroyed by the monk Barsauma at the beginning of the 5th century. See (Dvorjetski 2005; pp. 158–60; Nau 1927, pp. 186–91; Kiperwasser and Ruzer 2013, p. 49). |

| 68 | As maintained by Noy and Sorek regarding the mosaic at Apamea, see (Noy and Sorek 2003, p. 13), as well as by Villey regarding the North African synagogues of Kelibia and Hammam Lif, and their avoidance of human images, in contrast with contemporary church mosaics. See (Fantar 2009; Villey forthcoming). |

| 69 | See (Levine 2005, pp. 307–8). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuval-Hacham, N. Art and Identity in Late Antique Synagogues of the Roman-Byzantine Diaspora. Arts 2019, 8, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040164

Yuval-Hacham N. Art and Identity in Late Antique Synagogues of the Roman-Byzantine Diaspora. Arts. 2019; 8(4):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040164

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuval-Hacham, Noa. 2019. "Art and Identity in Late Antique Synagogues of the Roman-Byzantine Diaspora" Arts 8, no. 4: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040164

APA StyleYuval-Hacham, N. (2019). Art and Identity in Late Antique Synagogues of the Roman-Byzantine Diaspora. Arts, 8(4), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040164