On the Interpretation of Watercraft in Ancient Art

Abstract

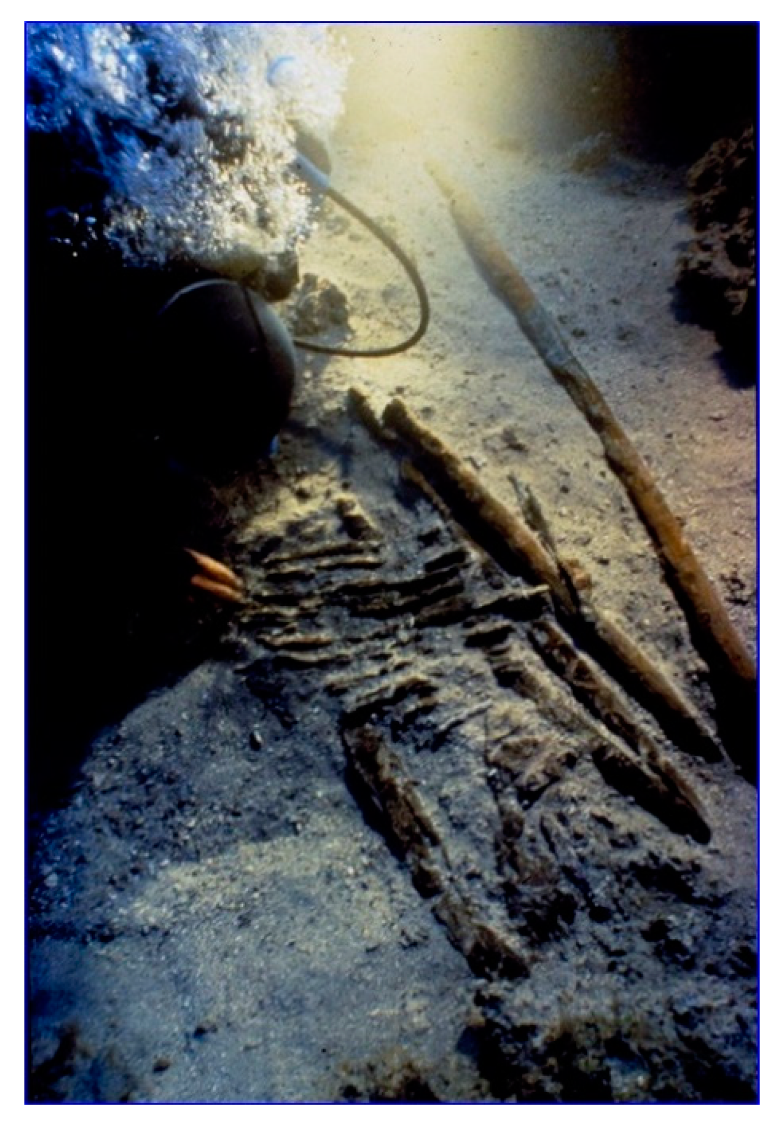

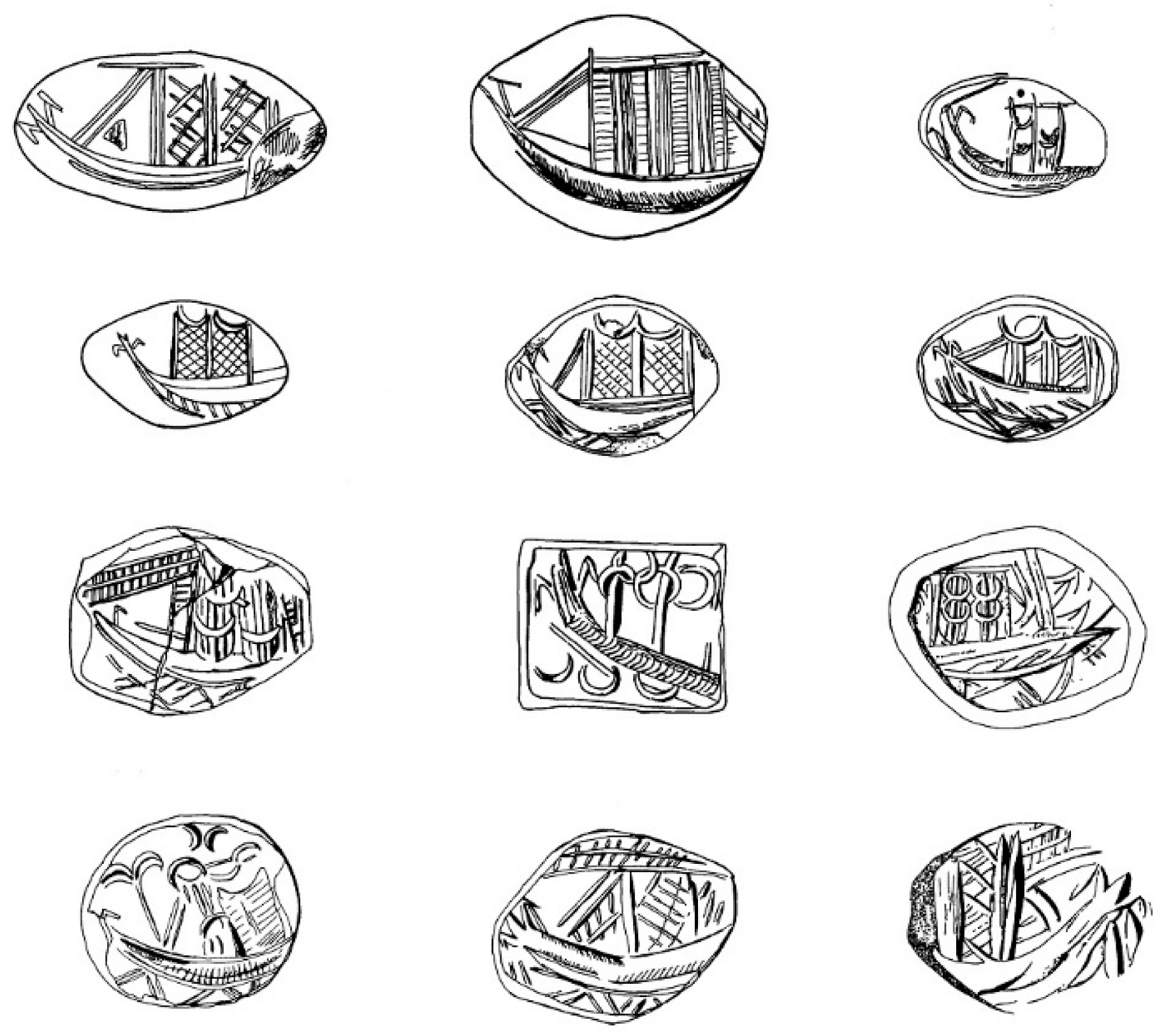

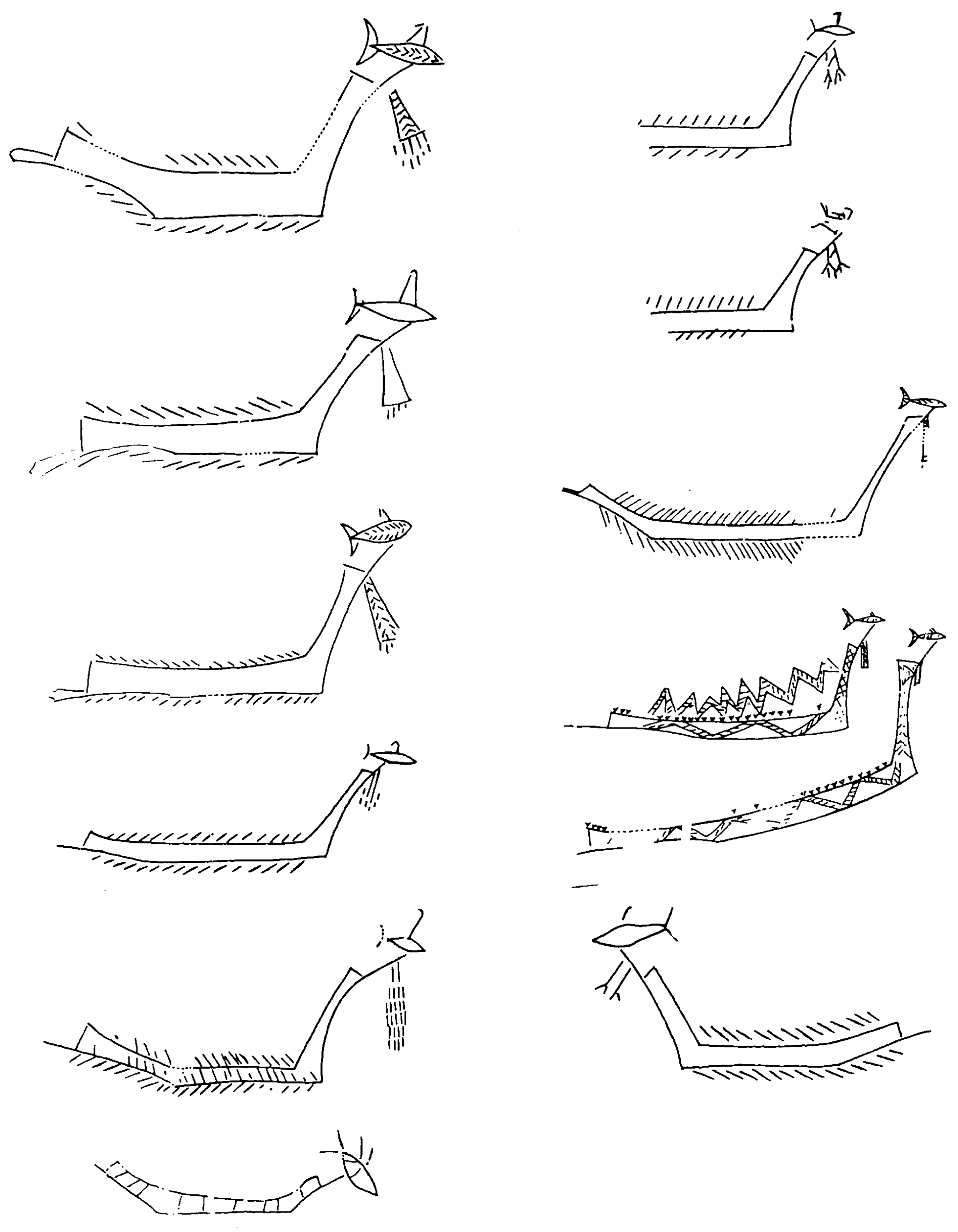

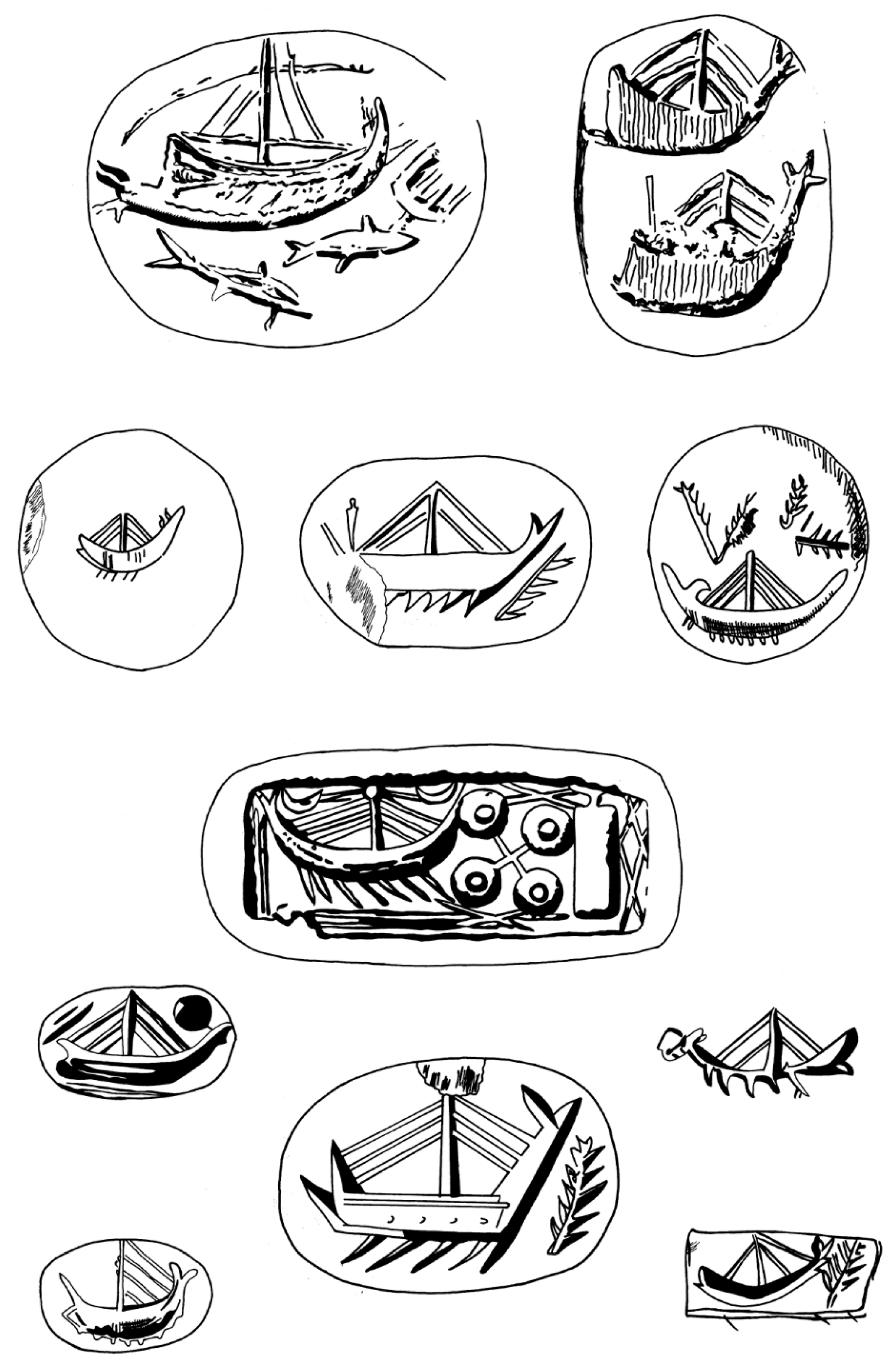

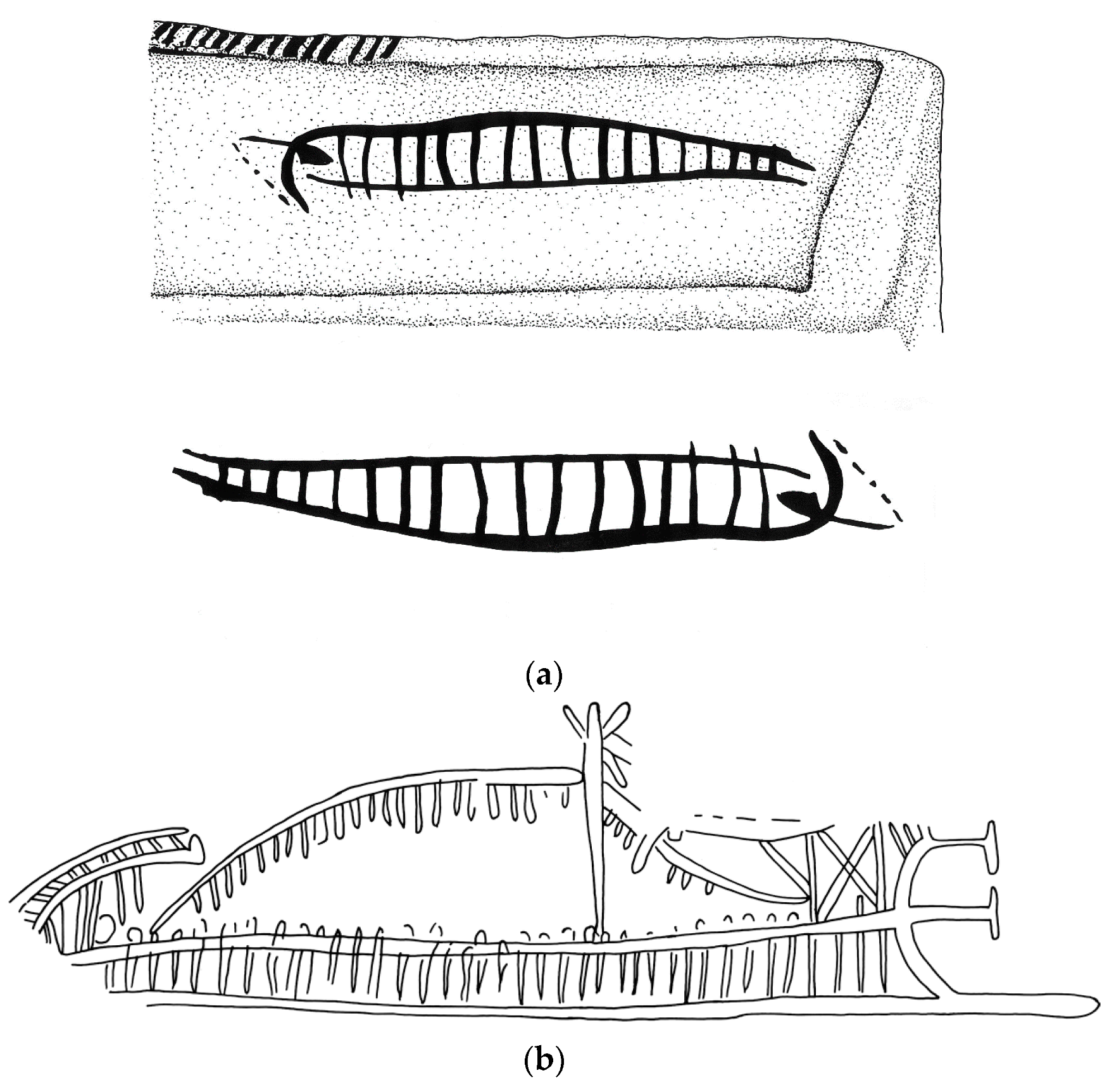

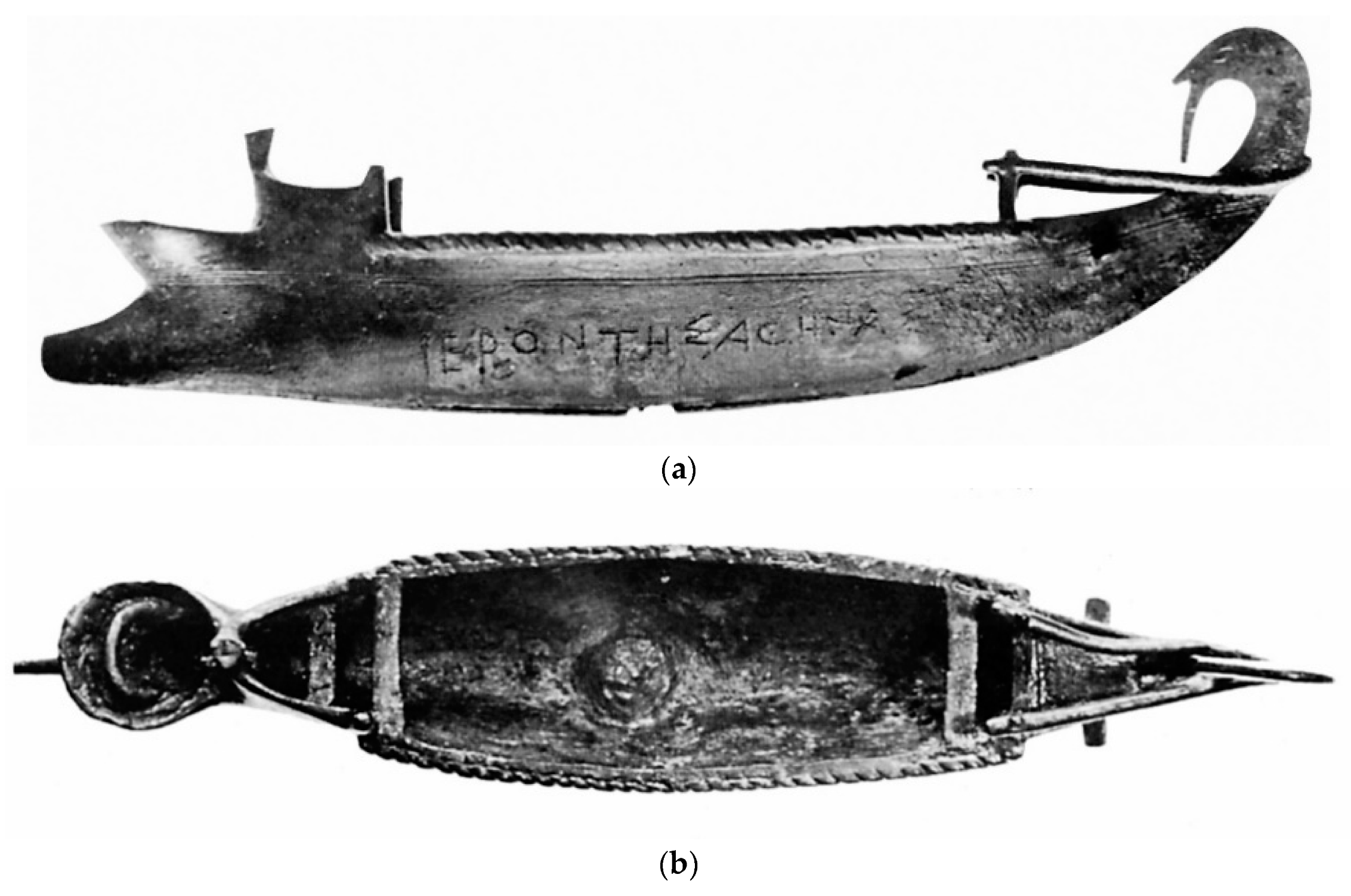

Until we excavate a sunken ancient vessel lying upside down on the sea bed, preserving in sand or mud most of the deck, we have to rely for our knowledge of the latter on vase painters, artists’ representations and more surely on graffiti by sailors.

1. Introduction: Why Iconography?

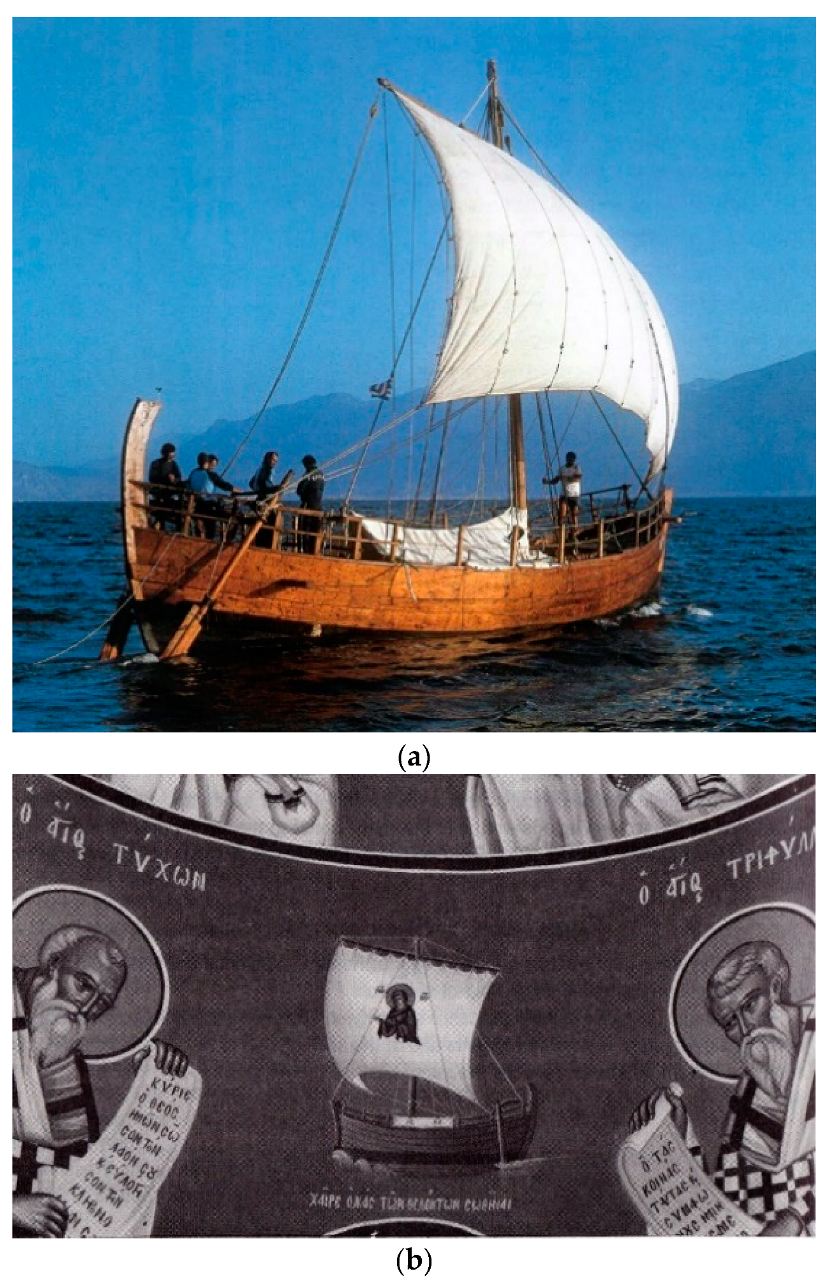

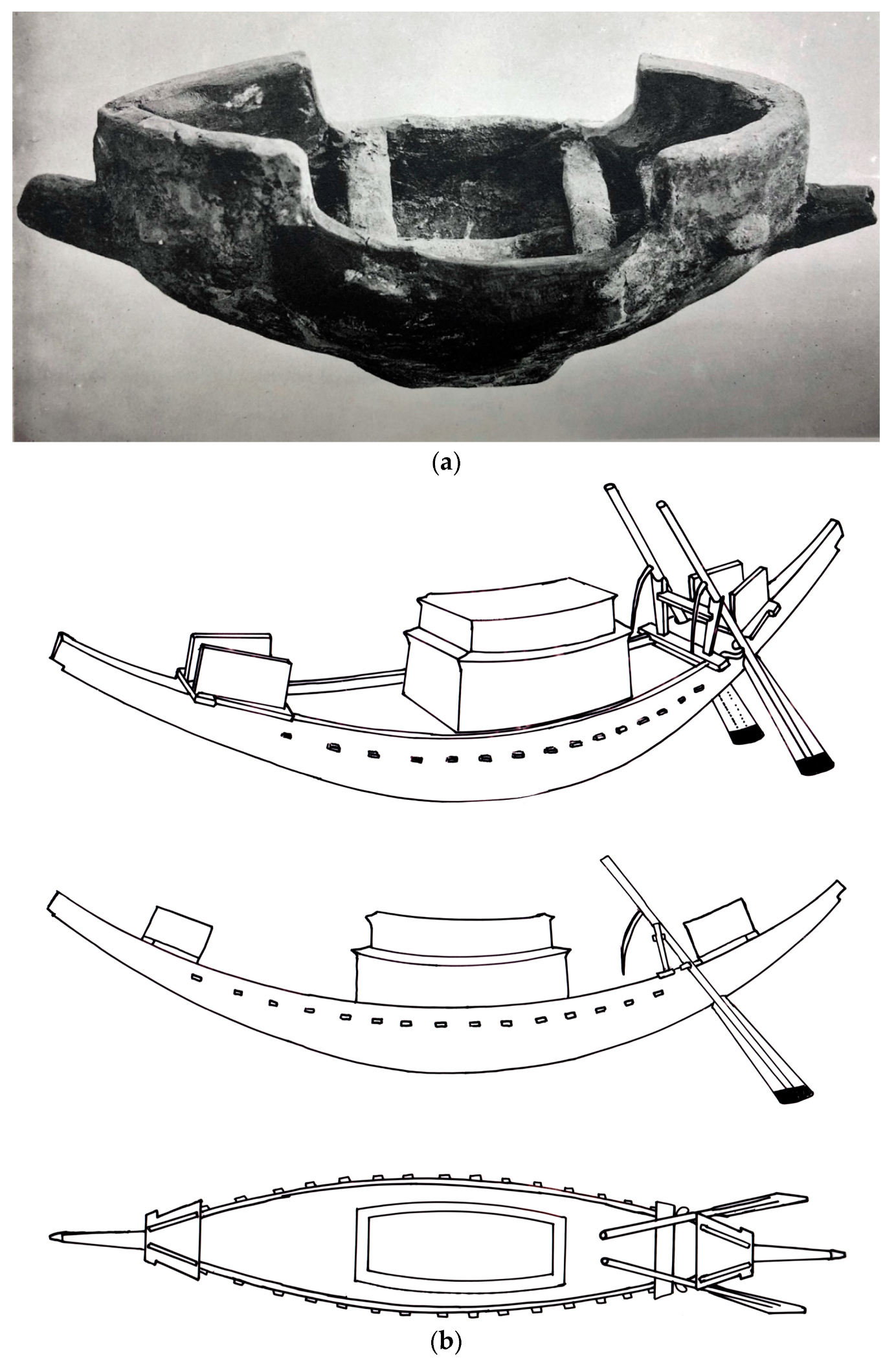

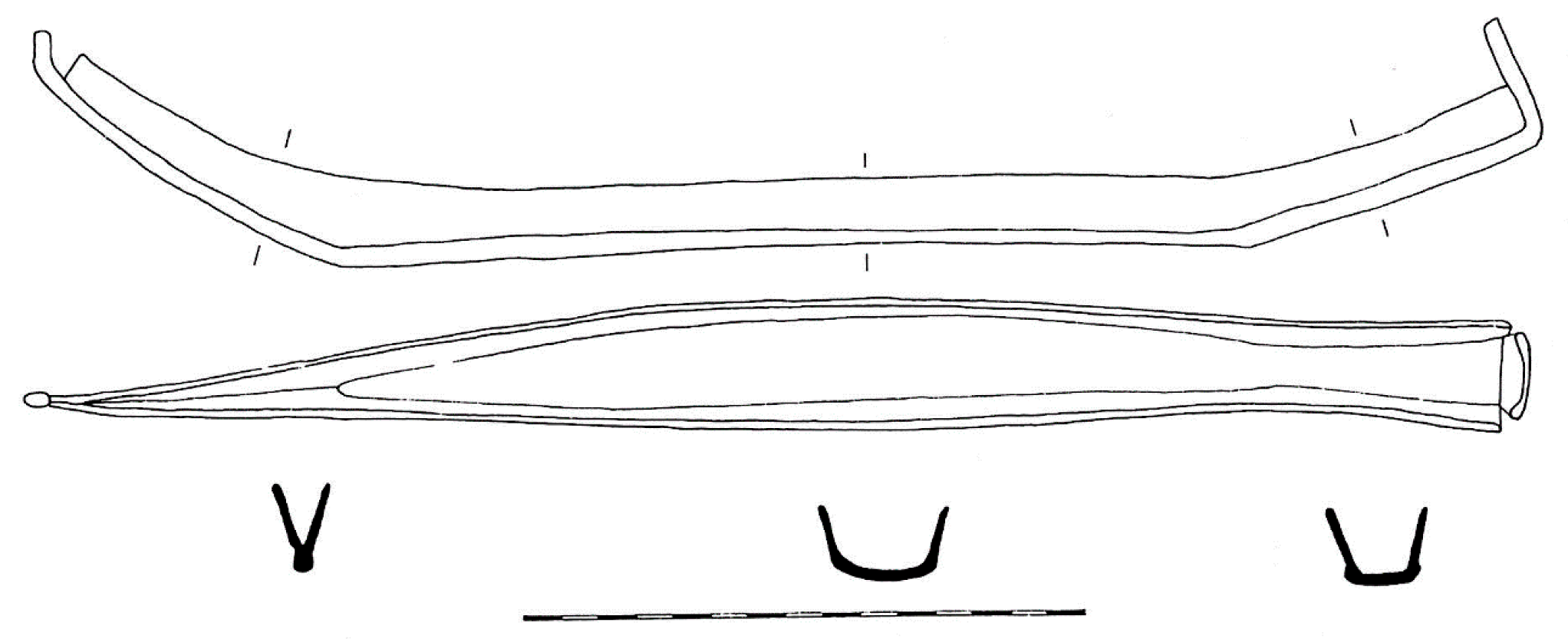

Because only the lower portions of Bronze Age hulls have been preserved, these Egyptian models and pictures are the most reliable guide for reconstructing the mast and yards, rigging, steering, and other parts of the ship that are not completely buried, and thereby preserved, at the time of wrecking…. By sheer coincidence, the preserved hulls and iconography are perfect complements, since the pictures never indicate what is below the water line.

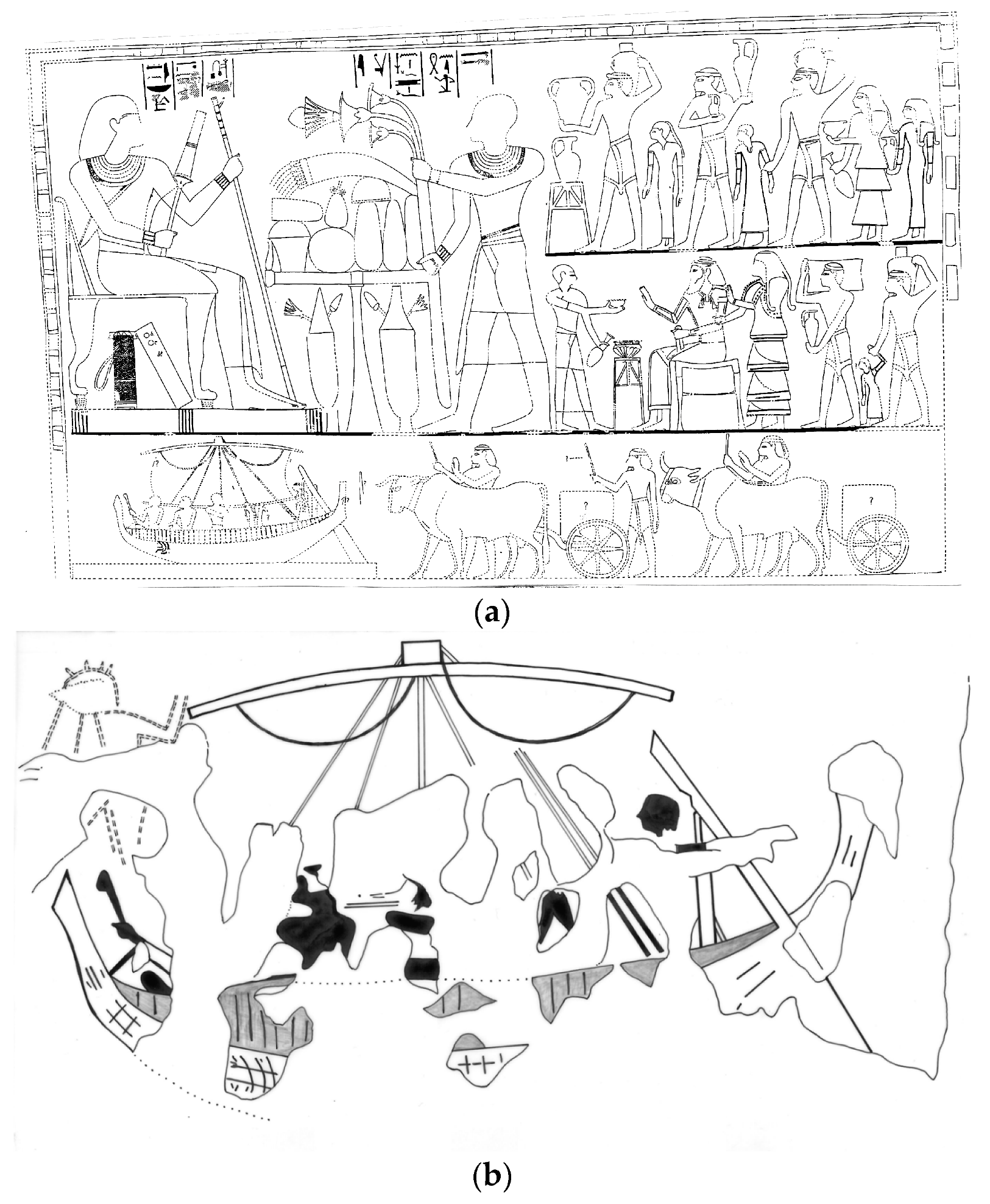

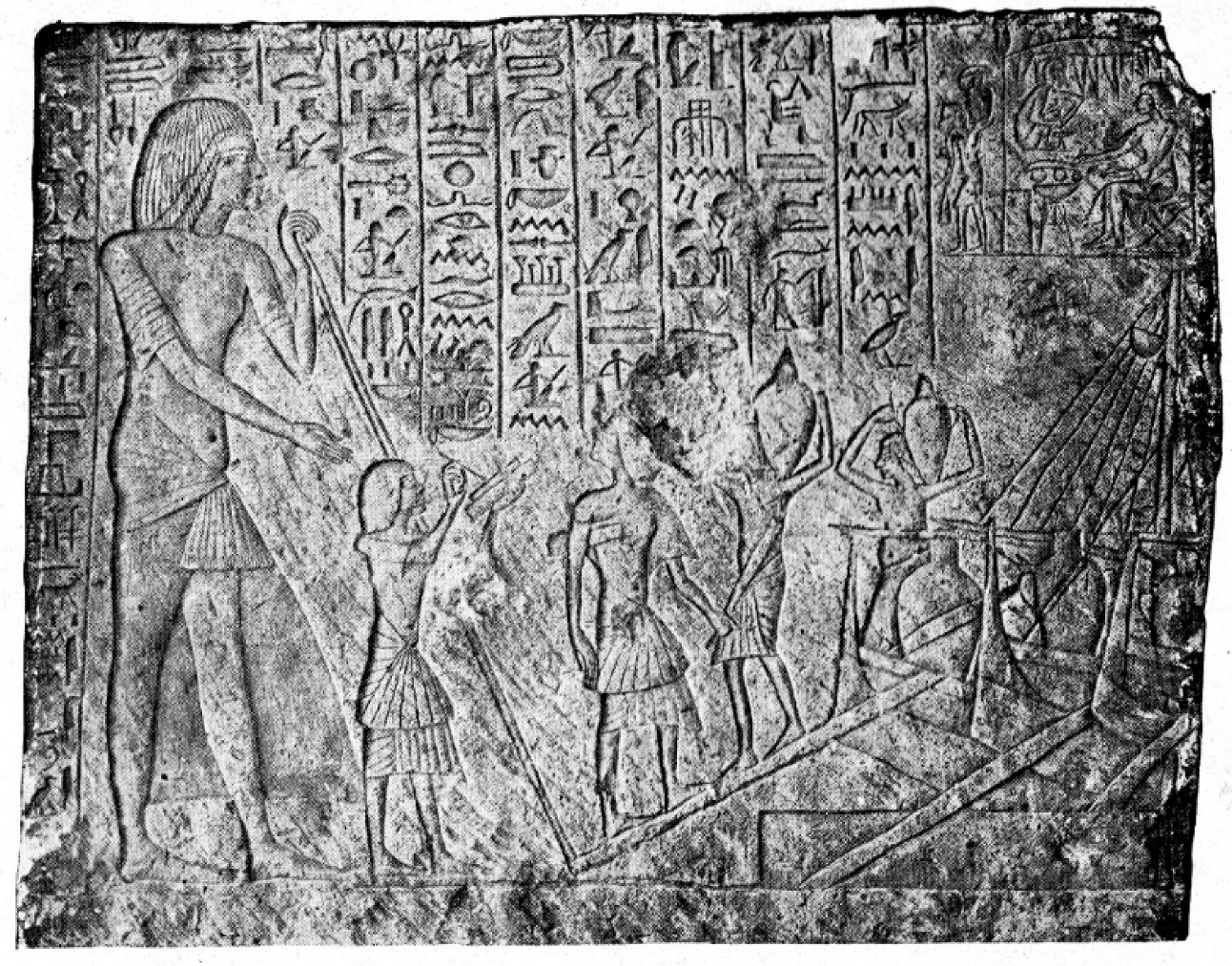

If the study of written documents and that of excavated objects have their special difficulties and limitations, the interpretation of pictured records, forming a third division of historical research, also offers scope for philological and archaeological knowledge, as well as wide experience and some psychological sense. We may ask then what measure of truth can be reached in this third field, and particularly in that realm which is just now claiming special attention—the precise valuation of such scenes as illuminate the international relations of Egypt in the imperial period.

It is all important, therefore, that an inquiry should be made into the reliability of these pictures, and it is as well to realize at the outset, to prevent disappointment, that modern standards of historical exactness will have to be imported by us into the study of these records. We shall not find them ready for us there… Burbage, the inventor of the calculating machine, was once asked by a lady whether, if he put in the wrong figures, it would still come out right! Mathematics suggests that the value for knowledge of the above quotient would be relative to the accuracy or inaccuracy of the “facts”, multiplied by n (the number of items used), but would demand that minus quantities (the silence and lacunae of the sources) should rank equally with plus quantities in the calculation. History is not in the least an exact science. The vaguest branches of knowledge have much wider room in them than arithmetic has. The ideal historian is he who to a base of great industry adds in perfect proportion the strong acid of purified scepticism and the rare precipitant of refined telepathy.

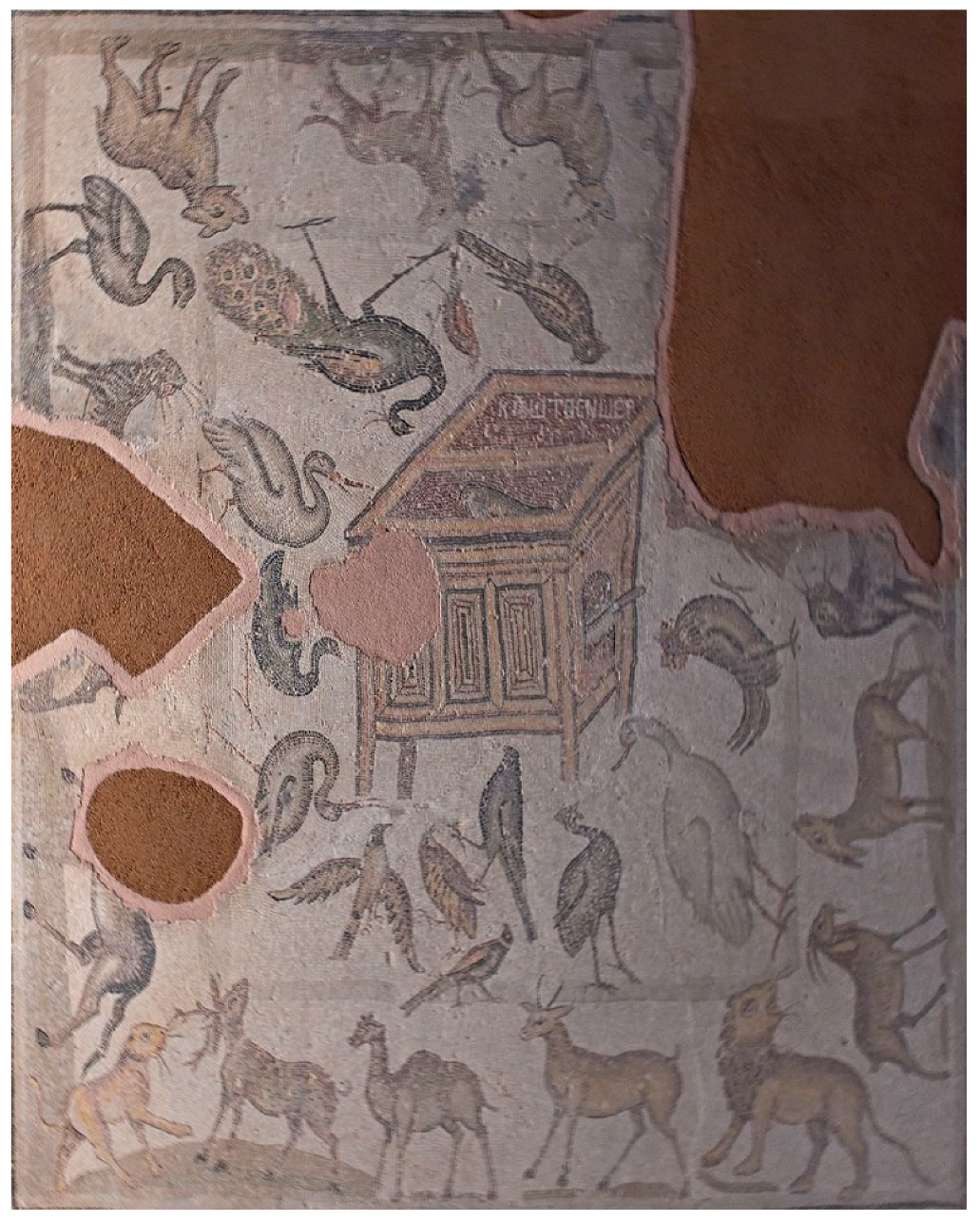

Textual evidence—Any pertinent contemporaneous written information must be evaluated to determine whether it can contribute to a better understanding of the image under study. Texts may deal with ships, their construction, their nationalities, their destinations, as well as a myriad of other considerations as, for example, a change in terminology that may supply an explanation for the odd manner in which artists depicted Noah’s Ark in Late Antiquity.5

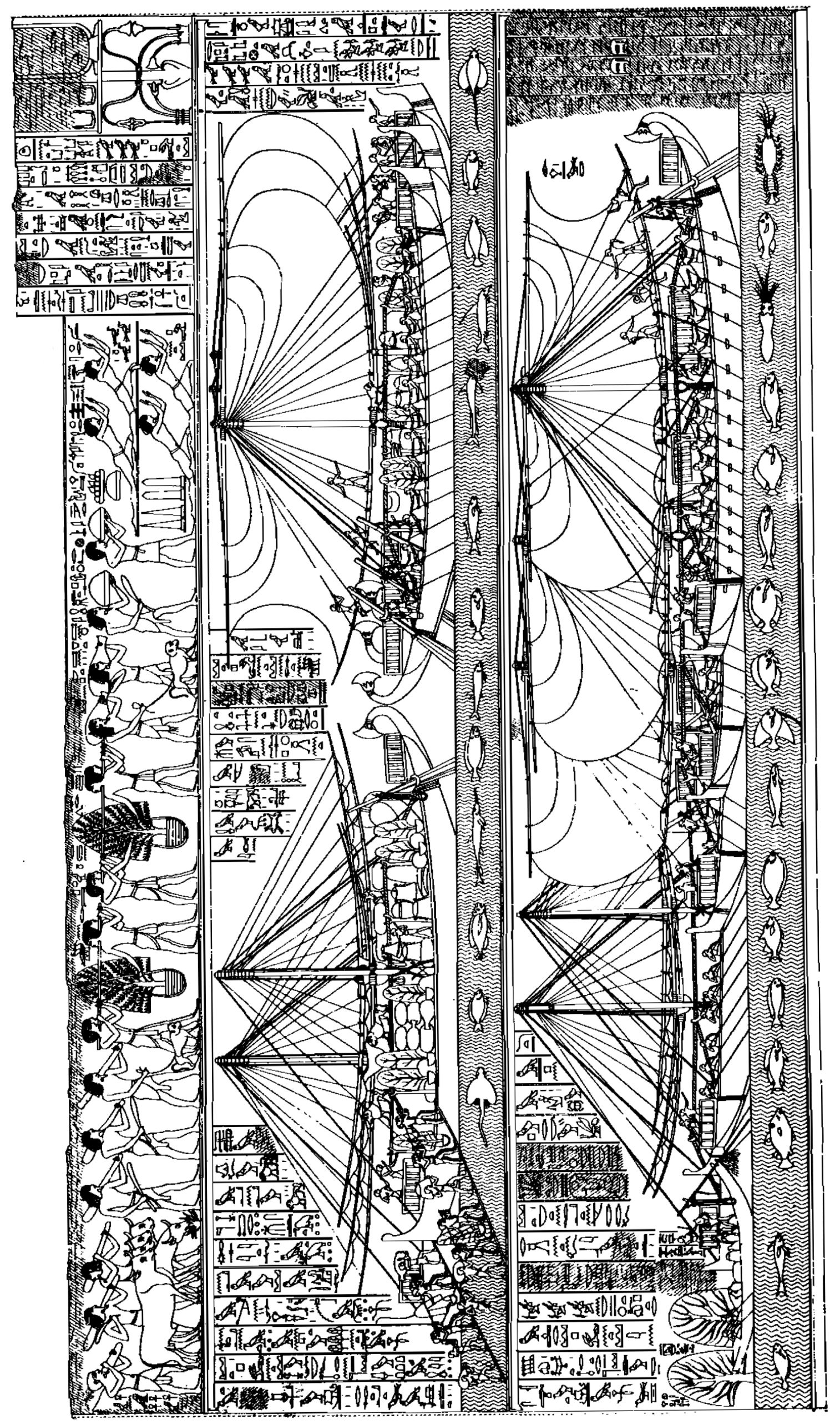

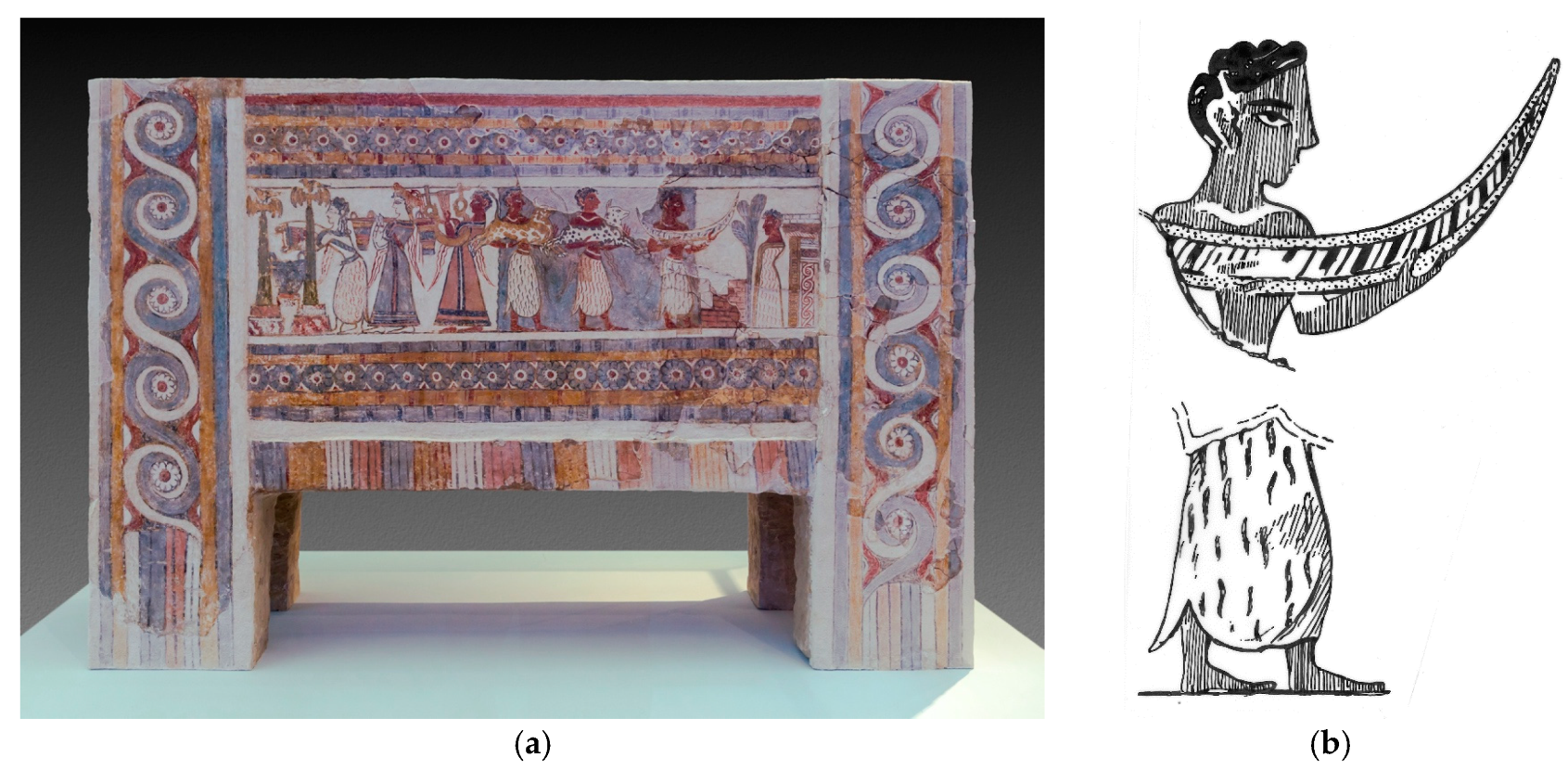

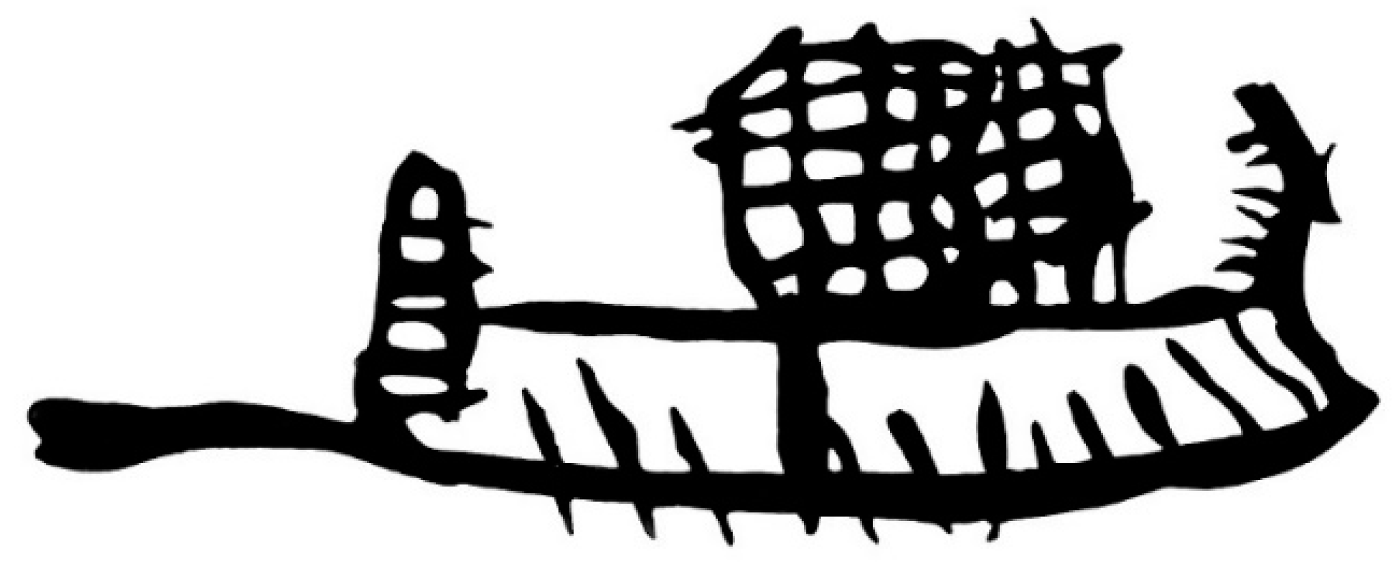

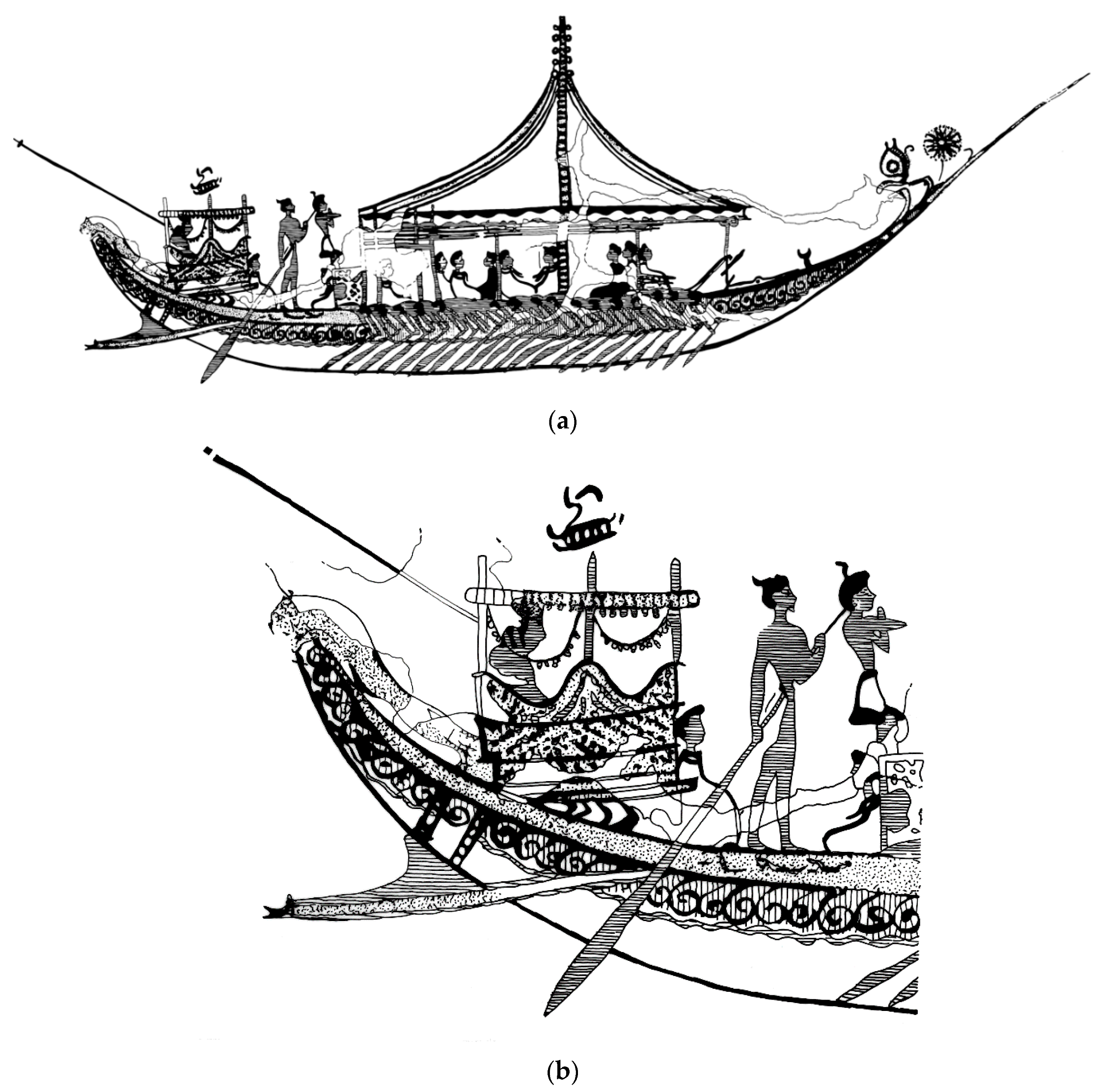

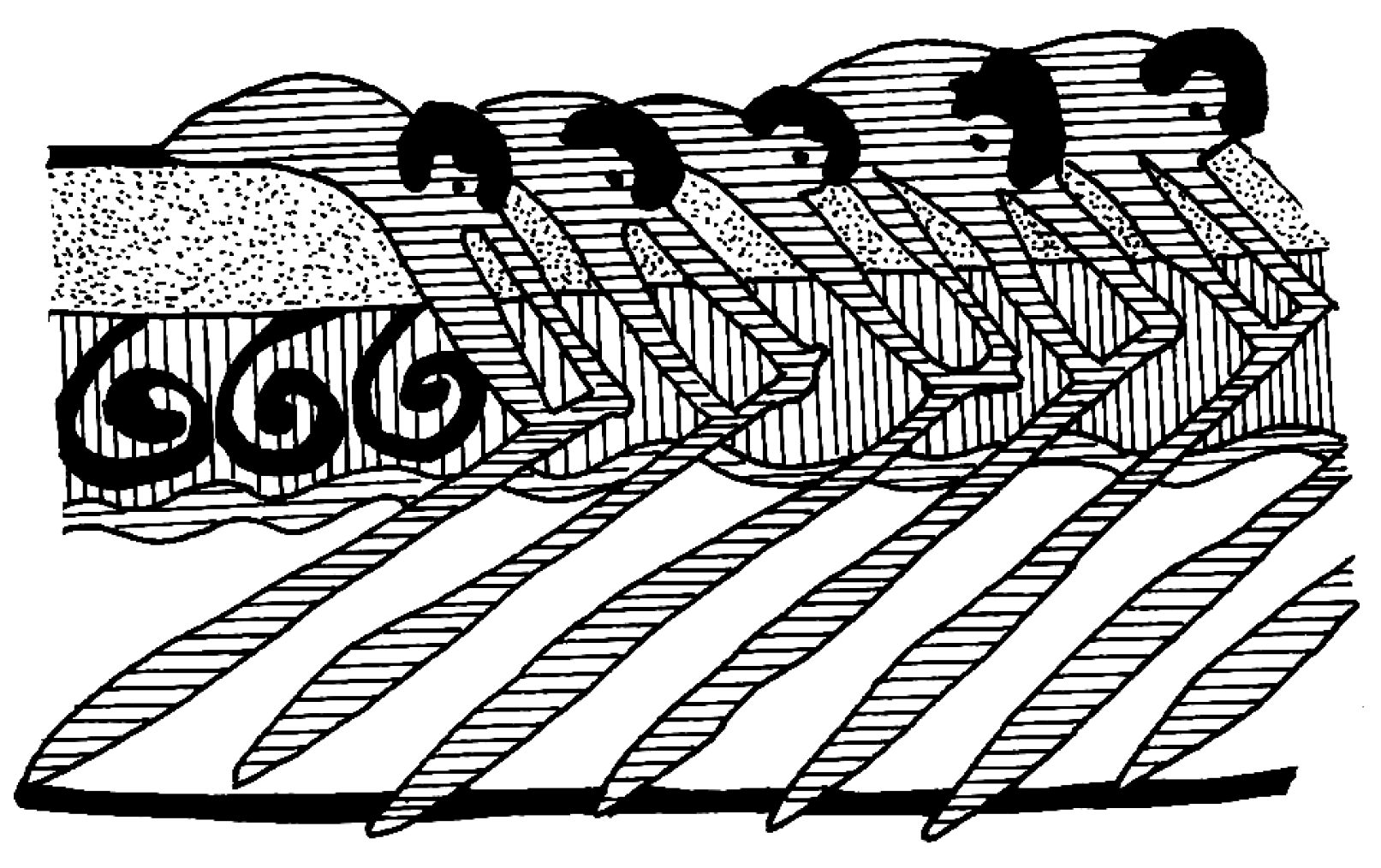

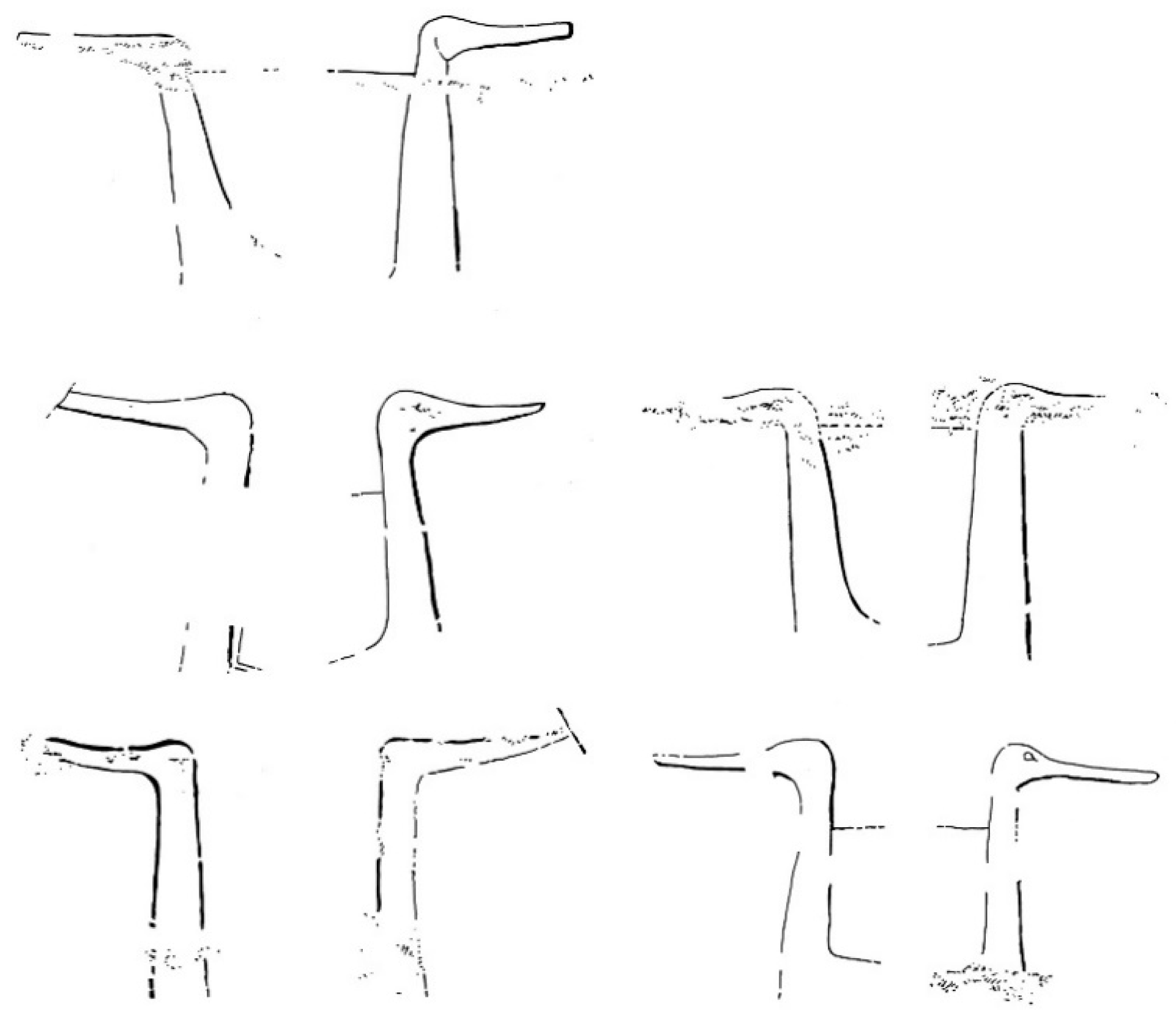

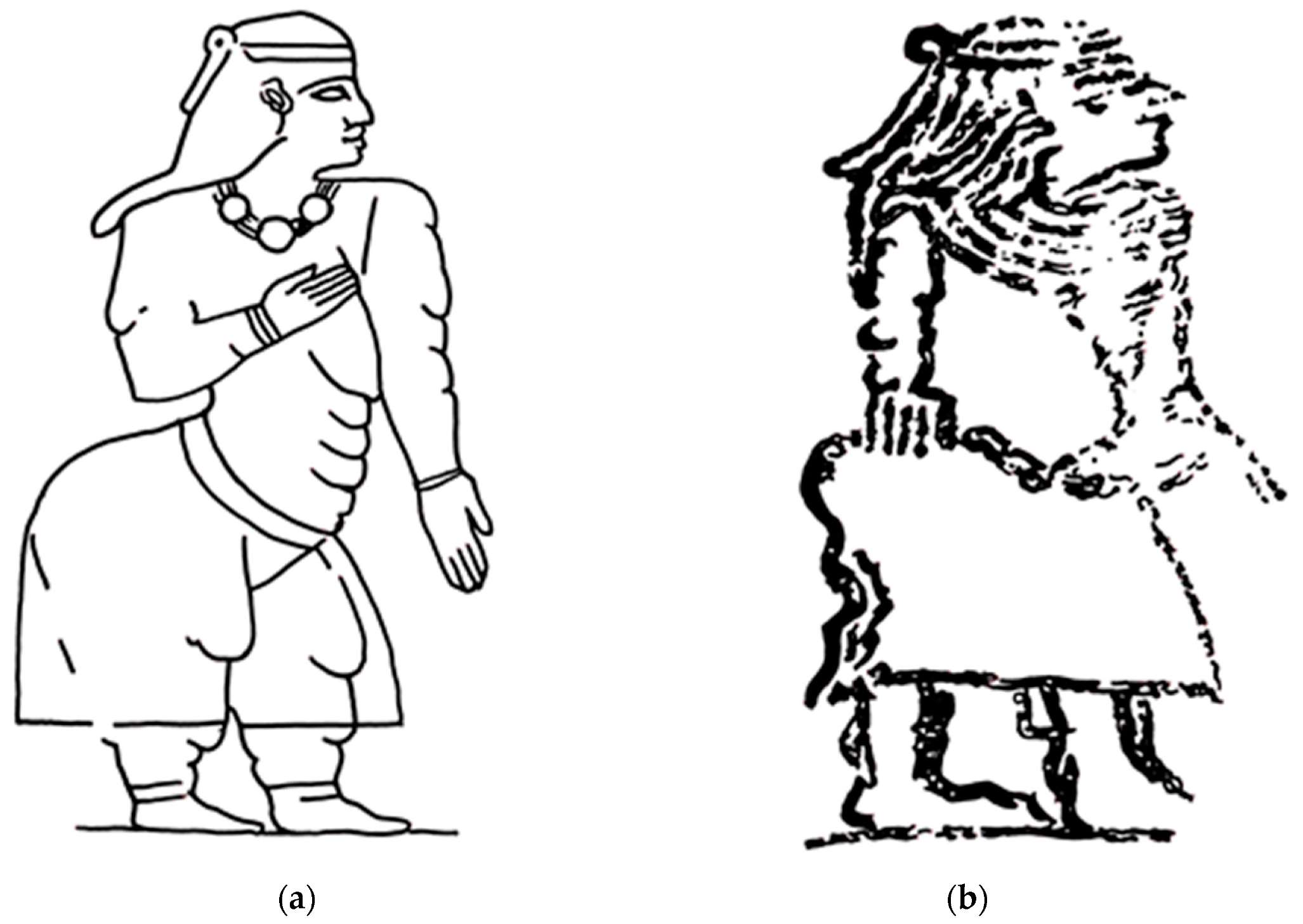

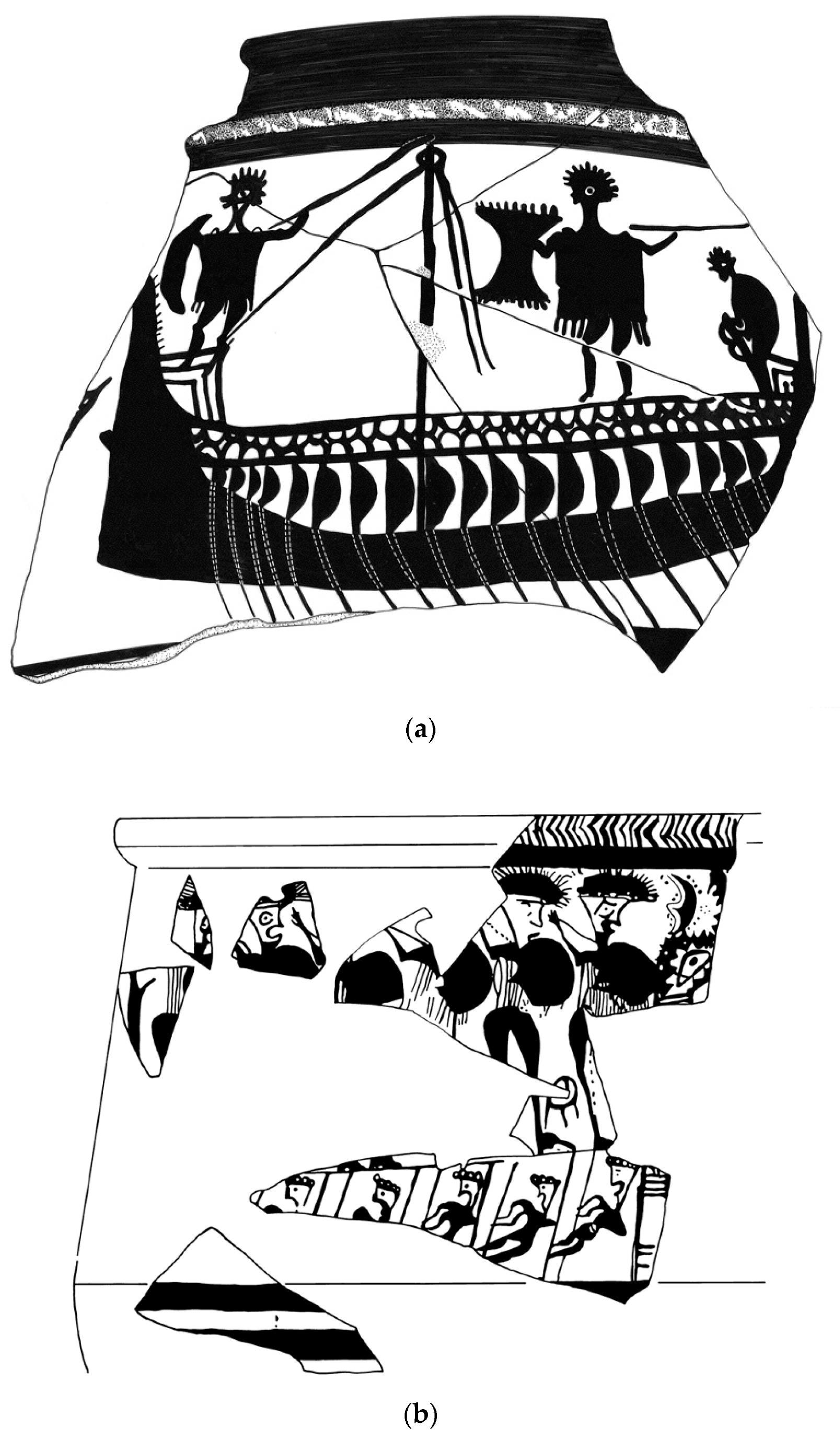

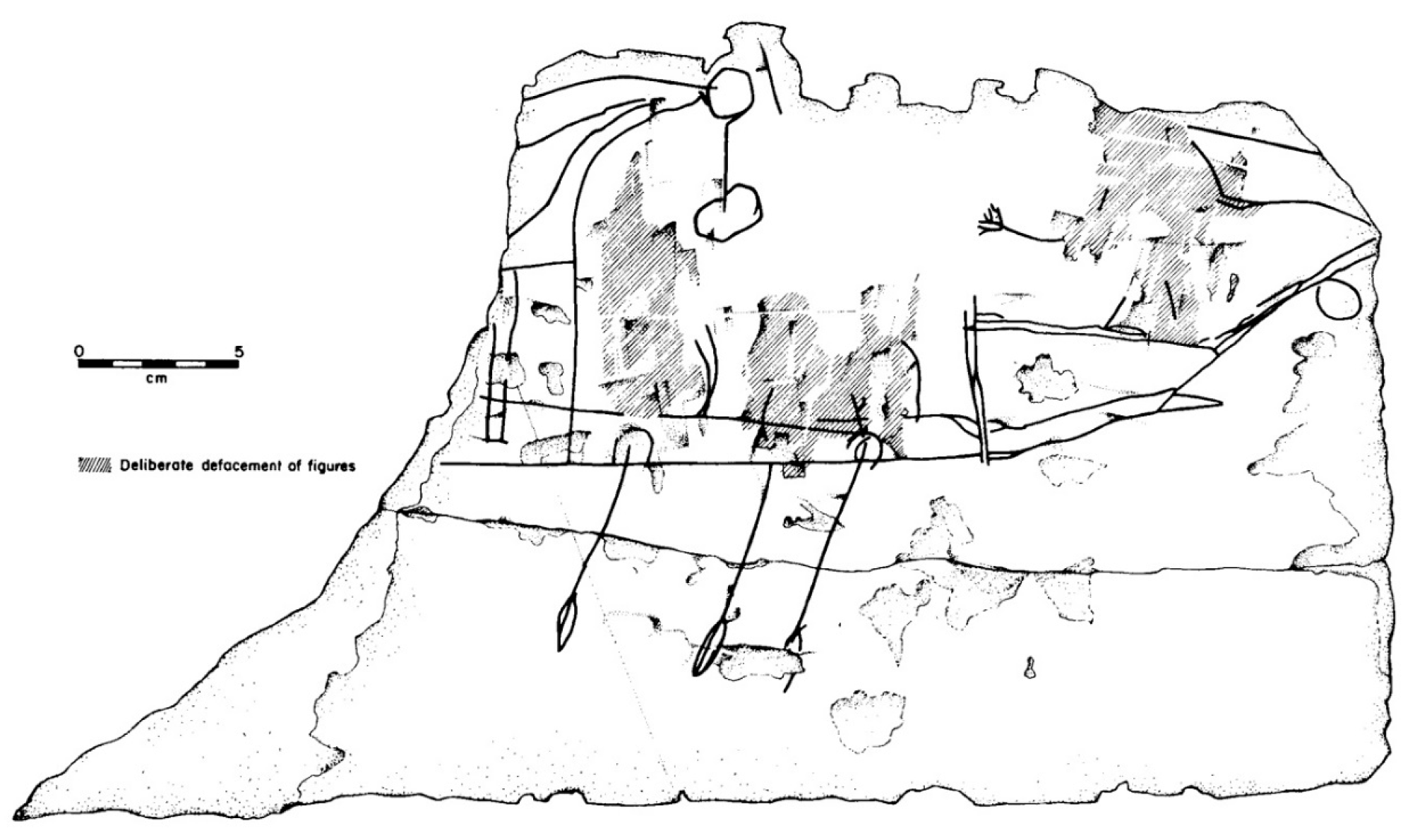

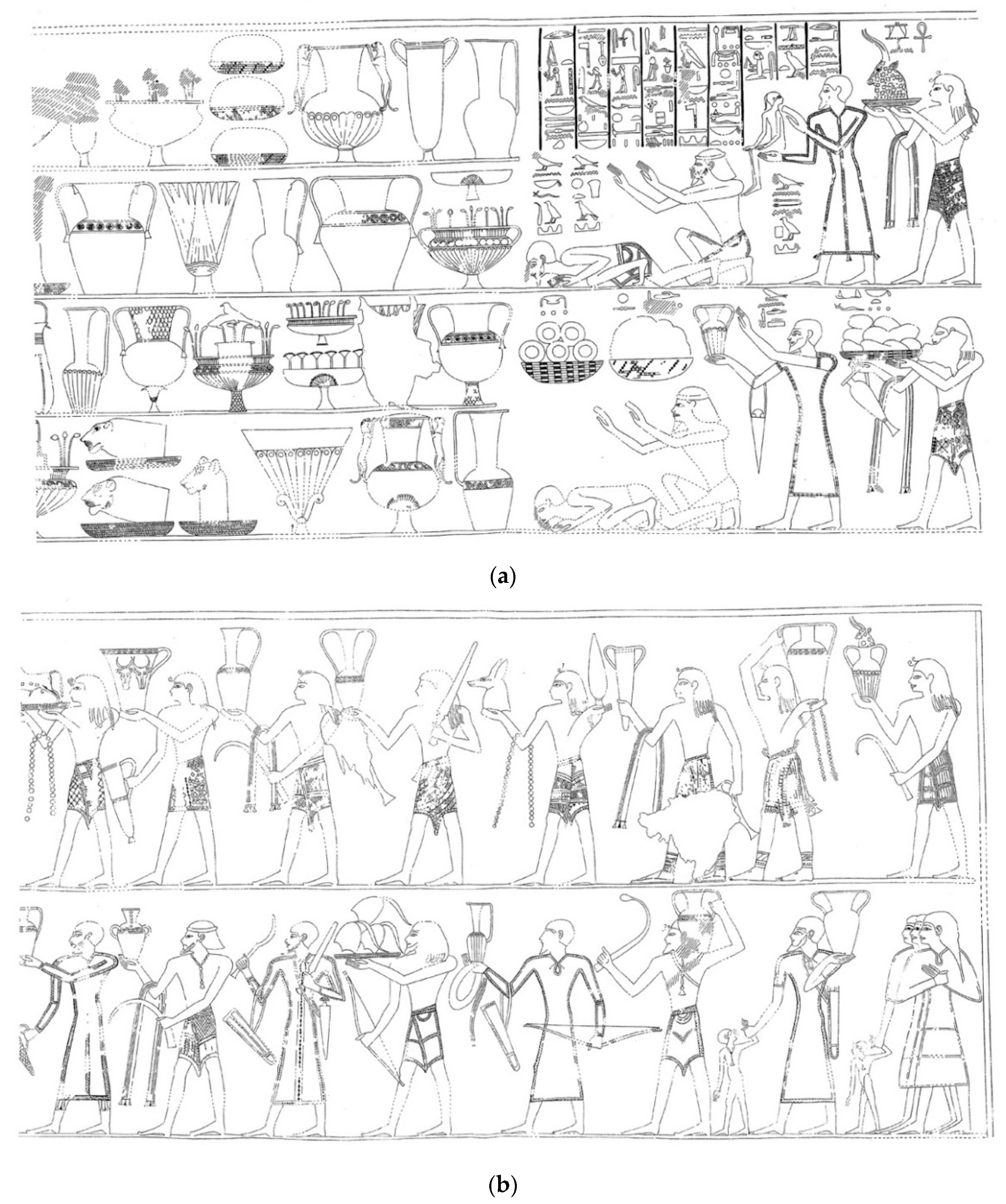

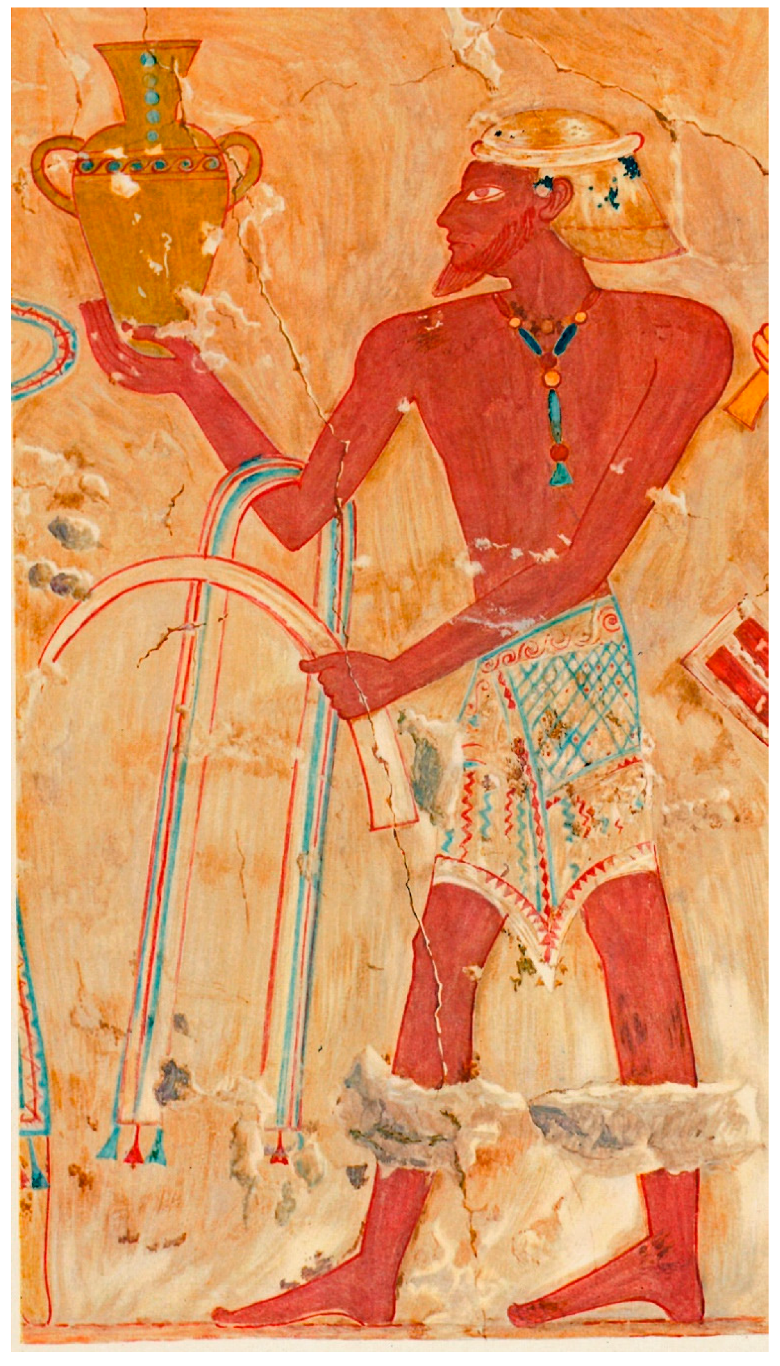

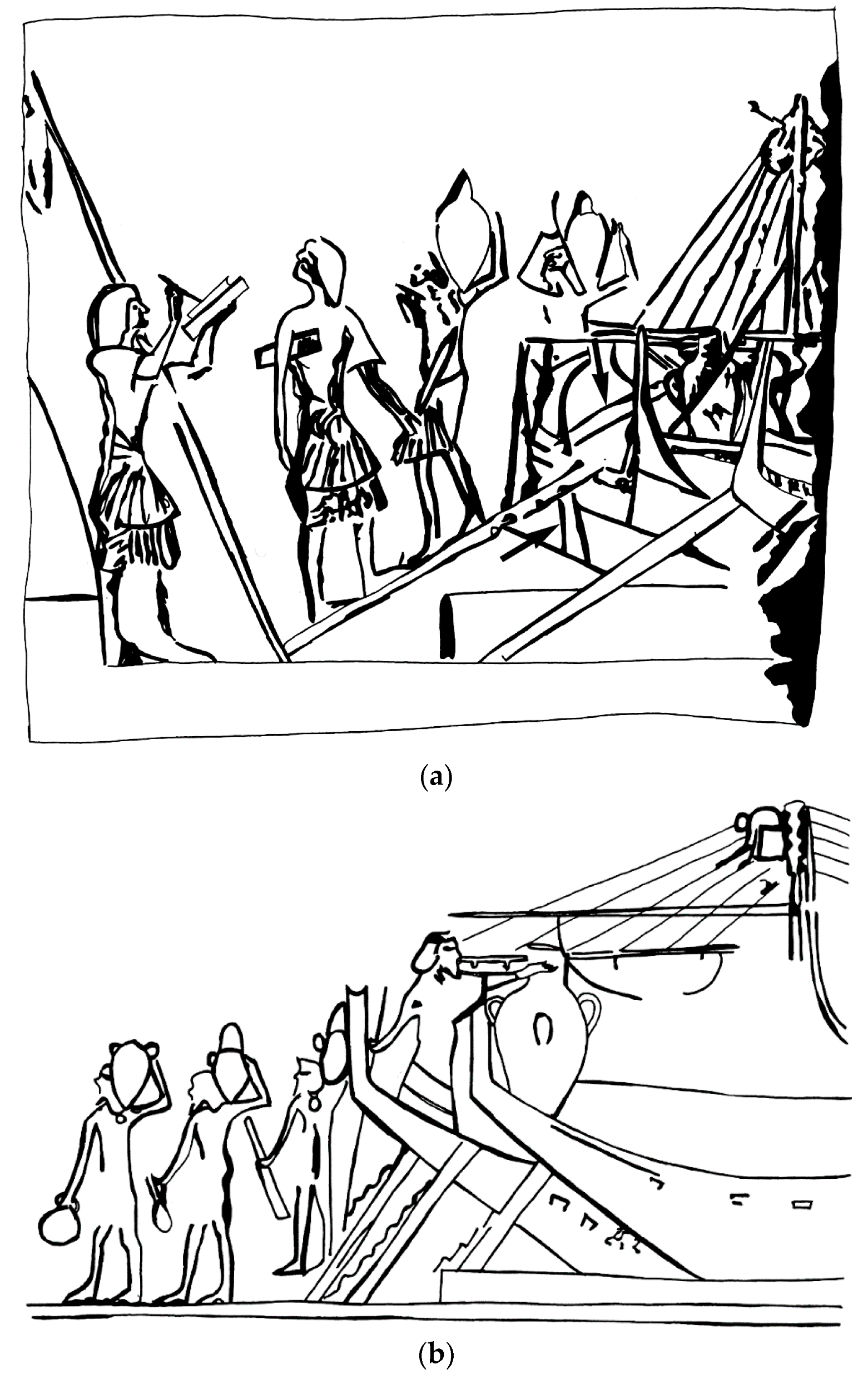

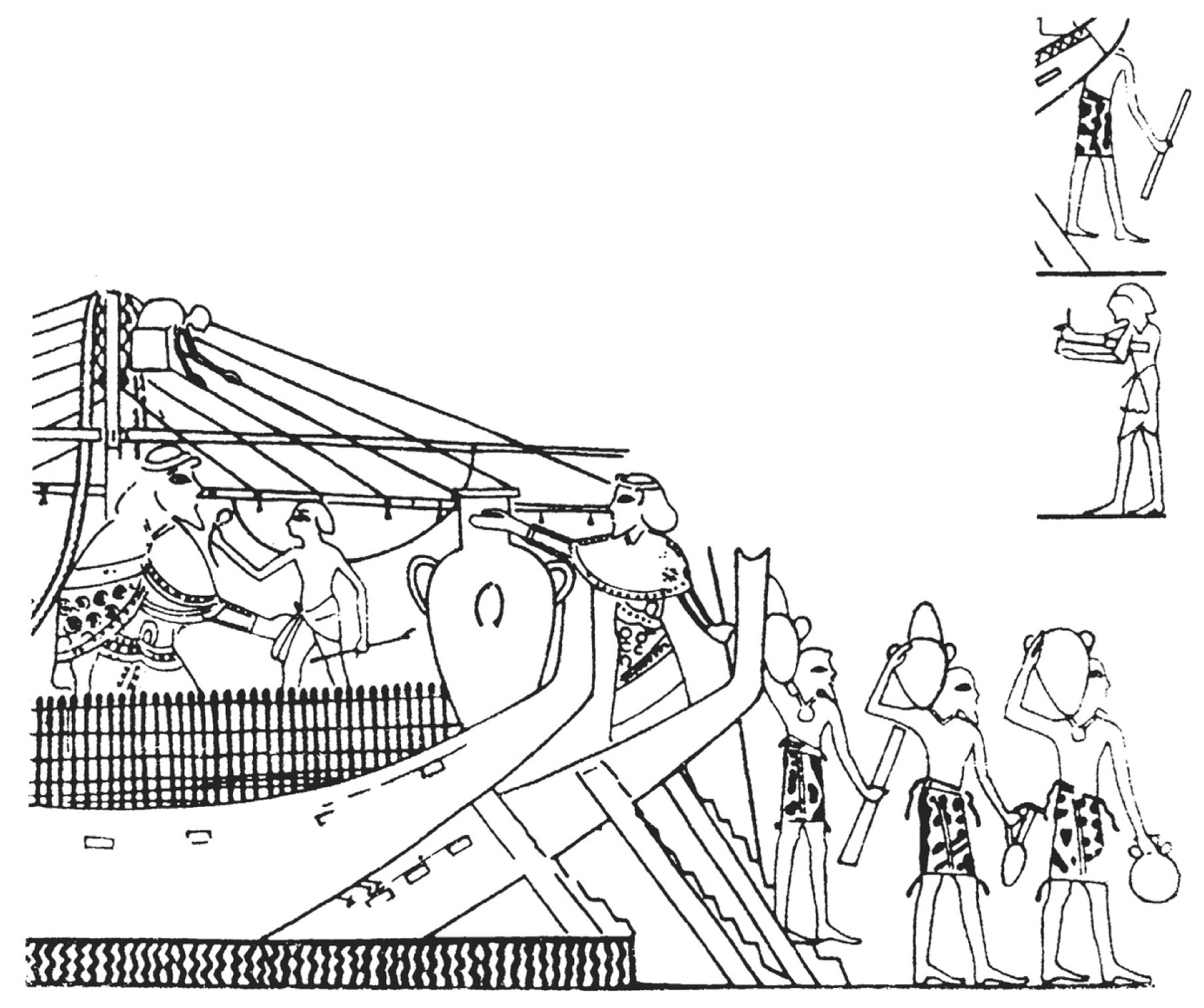

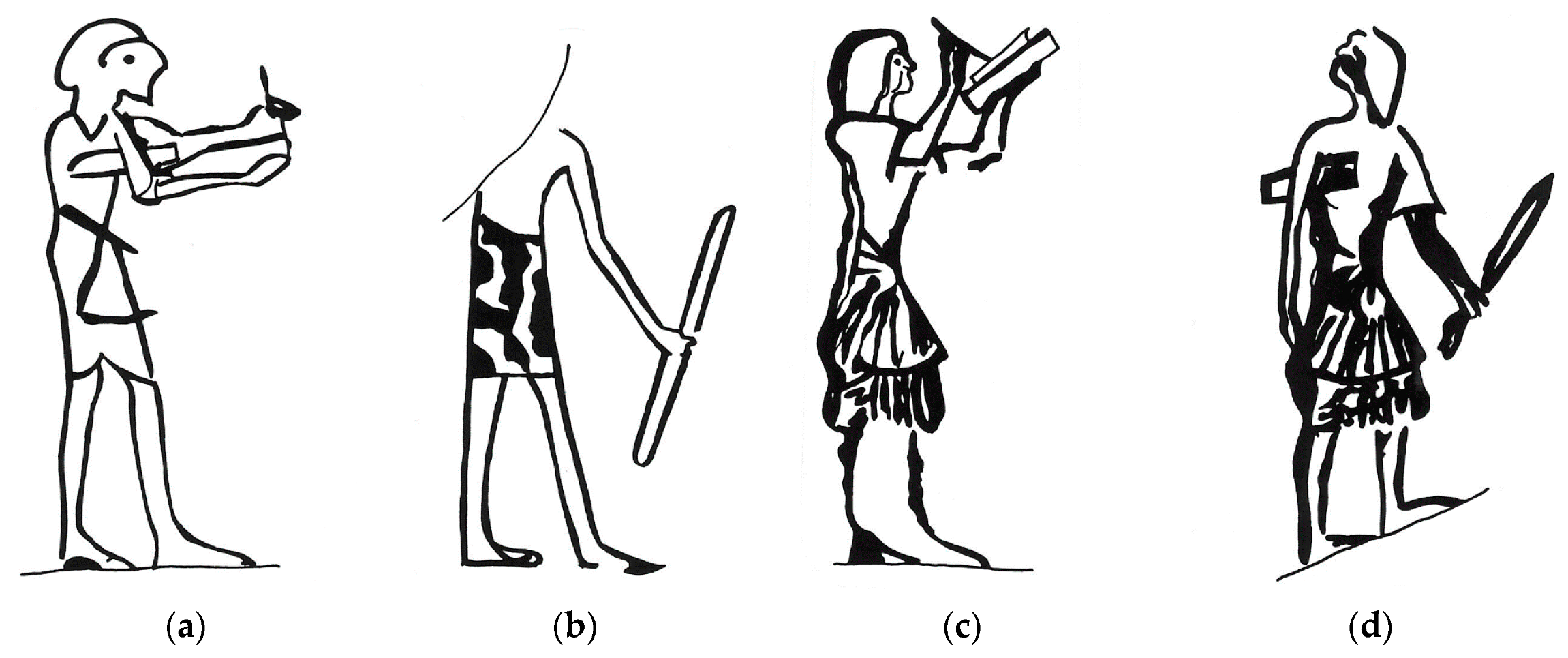

Archaeological evidence—The actual remains of vessels and their equipment are, of course, of intrinsic relevance. Ships, subject to the comments above regarding preservation, remain the main source for our understanding of hull construction techniques and the shapes of vessels along with myriad other details. Shipwrecks still can surprise regarding aspects of the upper structures of ancient hulls. Note, for example, the discovery of fragments of a wickerwork fencing on the Uluburun shipwreck, which supplies an important archaeological confirmation to the fencing that is depicted on representations of Syro-Canaanite ships as they appear in the tombs of Kenamun and Nebamun (TT 17; Amenhotep II) New Kingdom nobles at Thebes (compare Figure 8 to Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 9) (Pulak 1992, p. 11 figure 12; Pulak 1995, p. 54 Abb. 25; Pulak 2008, pp. 302, 303 figure 99; Wachsmann 1998, pp. 44–45, 51, 56, 217).6

Ethnographical evidence—At times the manner in which ancient cultures perceived their world seems to be inexplicable to modern observers. Comparisons to ethnographical parallels from the present, or the recent past, aid in penetrating the conceptual world of bygone times. Studying the construction, manners of propulsion, and use of traditional ships of the present and recent past, can provide valuable clues to research enigmas. Utilizing ethnographic materials from disparate cultures across the globe and over vast expanses of time does not argue for any direct cultural connection: rather, it addresses the consideration that the human psyche, given similar problems and available materials, will tend towards analogous solutions and expressions (see, for example, Hornell 1938a, 1938b, 1943; Wachsmann 1980, pp. 292, 293 figure 7, 294 figure 8, 295; Wachsmann 1998, pp. 71, 73 figure 5.6, 74 figure 5.7, 75, 77 figure 5.14, 78 figure 5.15, 79 figure 5.17–18, 80 figure 5.19–21, 81 figure 5.22, 185 figure 8.44, 190, 193 figure 8.60, 194 figure 8.63, 195, 196 figure 8.65, 197 figure 8.66–67; Wachsmann 2002a; 2002b).

2. Shaving with Occam’s Razor

3. From Detail to Abstract

4. Question the Source

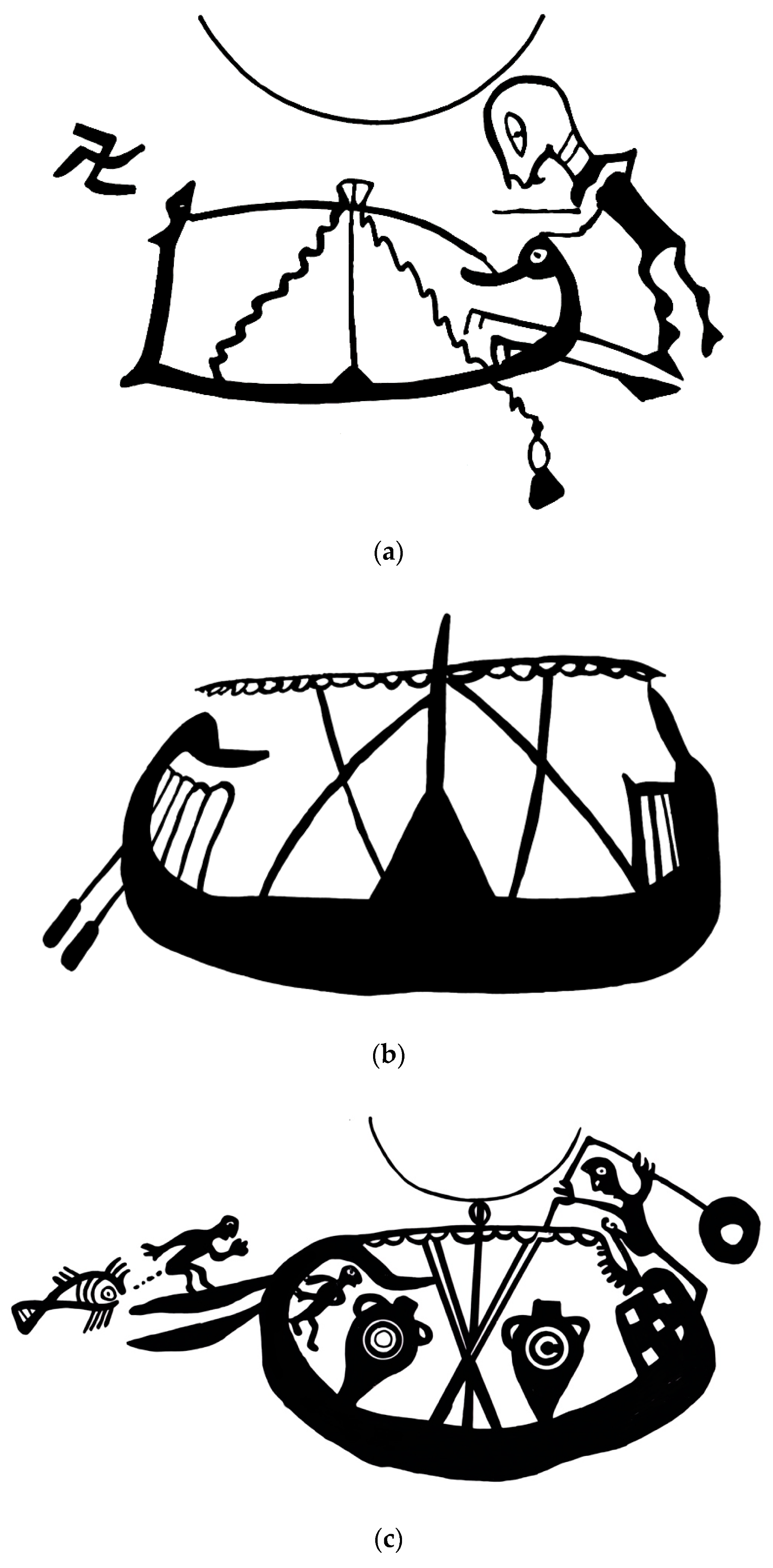

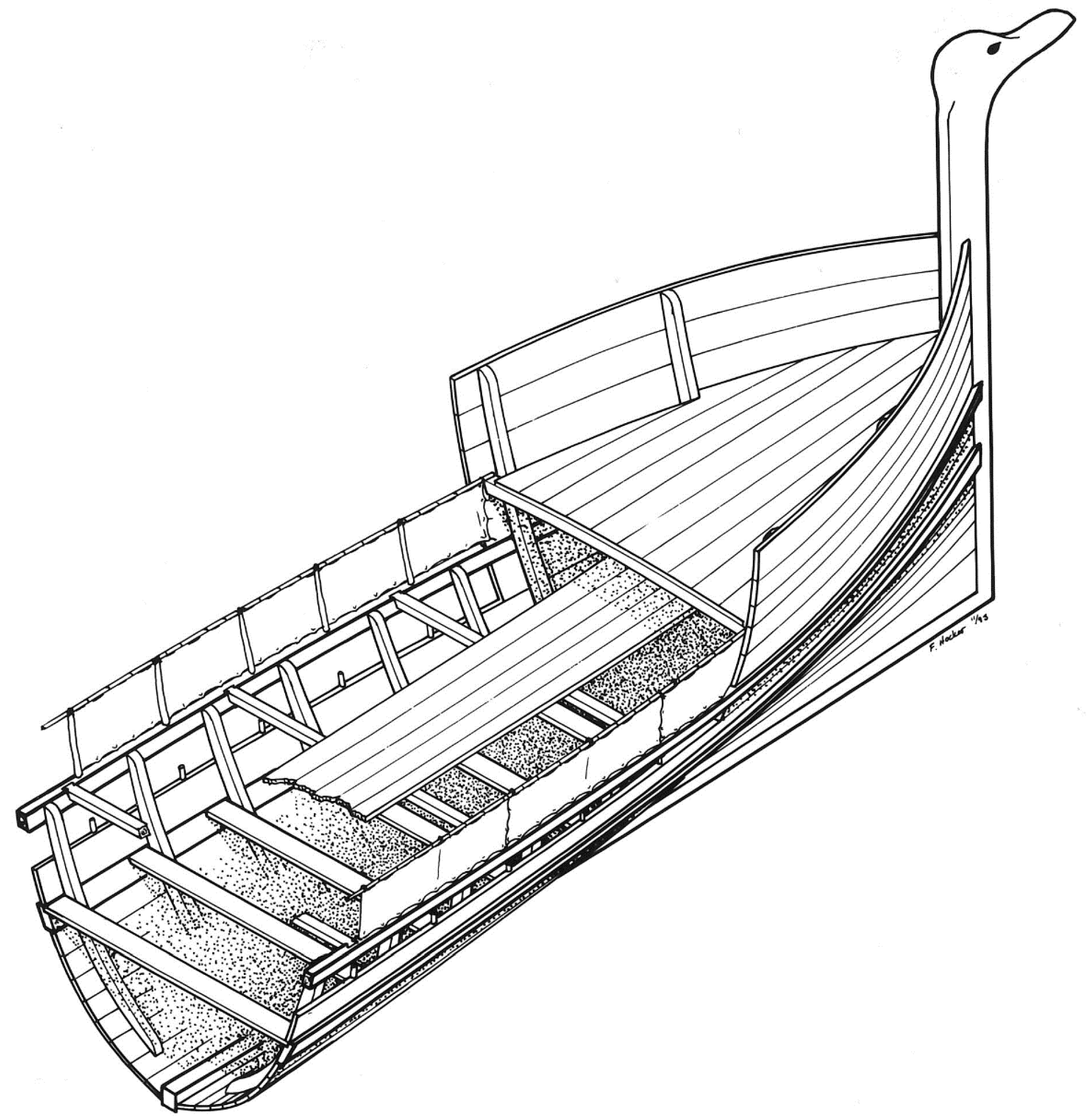

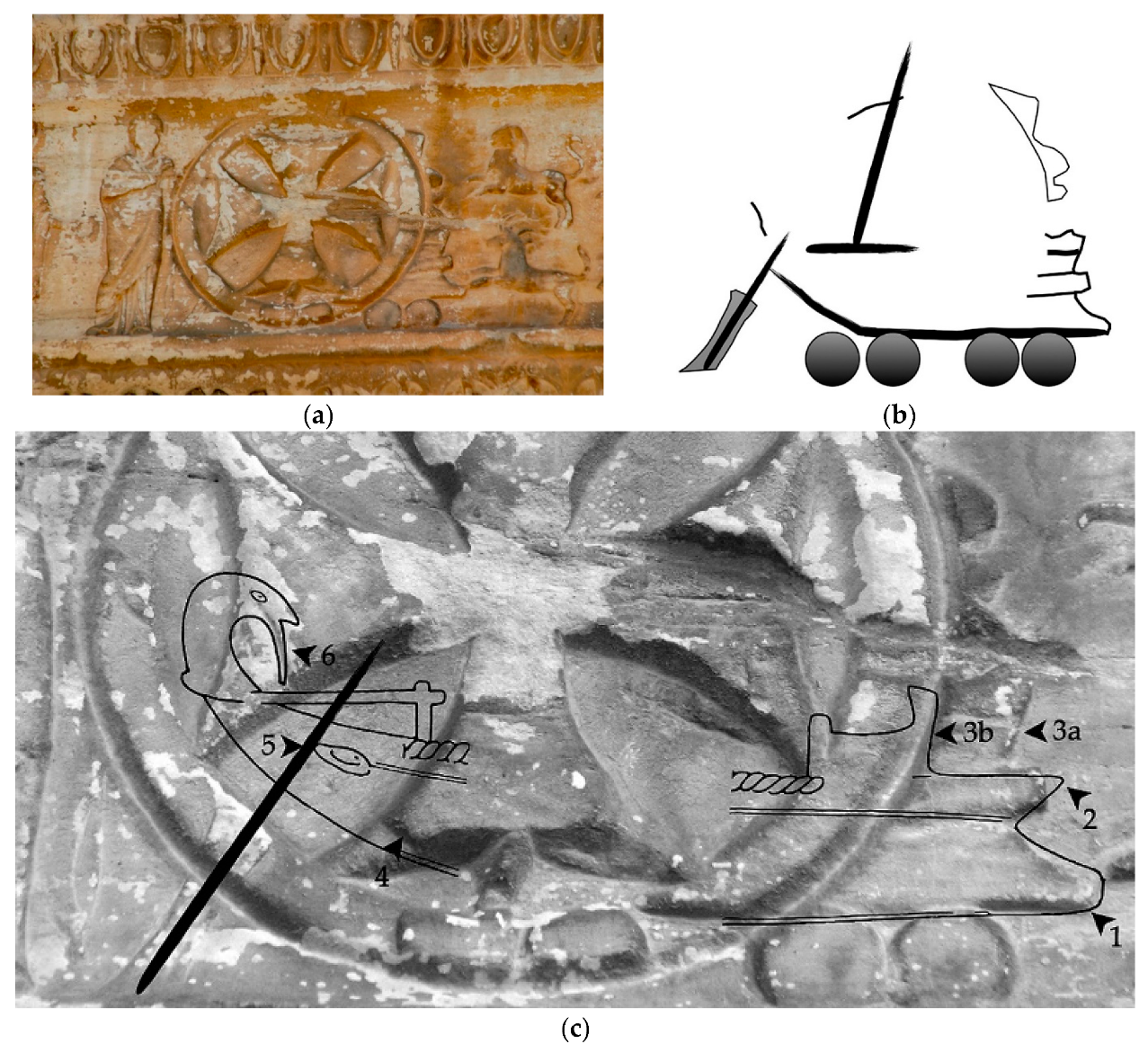

- The Kinneret Boat (Sea of Galilee Boat) dates to the first century BC–first century AD (Figure 2a,b). The vessel was discovered on the western shores of the Sea of Galilee, Israel (Steffy 1990; Wachsmann 1990; 2009; 2015). A contemporaneous mosaic from the adjacent site of Migdal depicts a vessel like the Kinneret Boat, fully rigged, crewed, and with its mast and sail furled (Figure 2c) (Corbo 1978). This resemblance to the Kinneret Boat led me to erroneously conclude that the vessel in the mosaic represented an accurate contemporaneous depiction of the vessel type (Steffy and Wachsmann 1990). Ronny Reich (1991) notes, however, that there are other items arrayed around the ‘boat’ in the mosaic, which include a pair of Hellenistic/Roman-period scrapers (strigili), together with what Reich interprets as an ointment bottle (aryballos) attached to a ring with a chain, a drinking cup (kantharos), and a fish. In other words, the mosaic portrays a still life scene, including a model of one of the local vessels. Here again we have a situation that is analogous to that of the Hagia Triada Sarcophagus: in this case, a mosaic depiction of a model of an actual vessel.12

5. Modern Changes

6. On Ship Typologies

The task cannot consist merely of collecting and arranging the items offered and then deducing the solution, as if by an operation in mathematics or chemical analysis.…we long for exact historical truth and have so much to build on these deeply buried foundations, to remember how little it was the purpose of the ancient artist to record exact facts and still less to be of help to those who would come to his record without previous familiarity with its subject and its conventions. If we deal with his delightful, and, properly dealt with, most instructive pictures as if they were illustrations to an encyclopedia, we only delude ourselves and render his unintended services to the far future a diminution, instead of an increase of knowledge … We must be sadly content to know nothing if there is nothing to know. We must be as ready to score above the line as below, admitting the large total which has been lost to us by the carelessness and impulsiveness of our partner (the ancient witness) as well as the positive gains we have made together.

7. Which Way Forward?

8. Cultural Continua

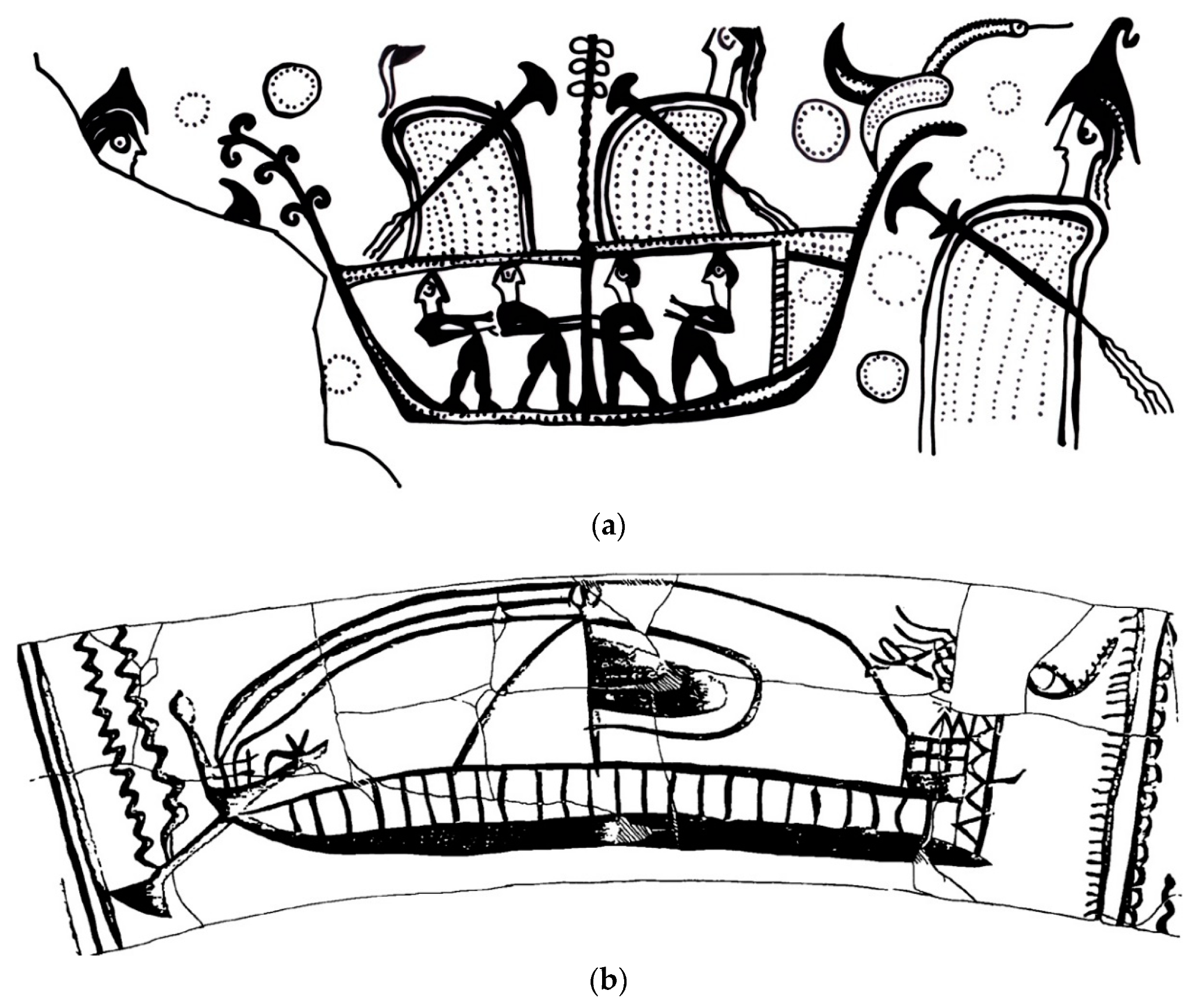

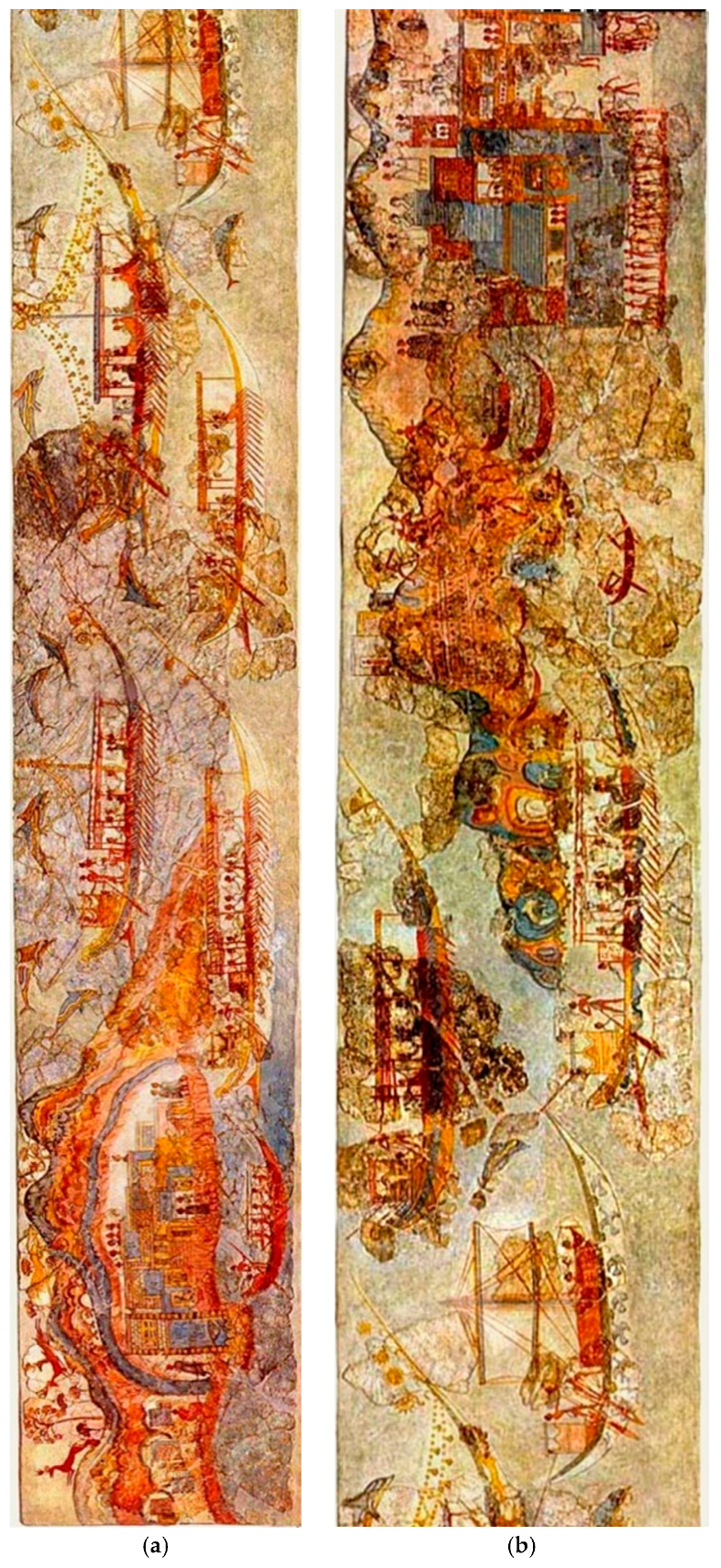

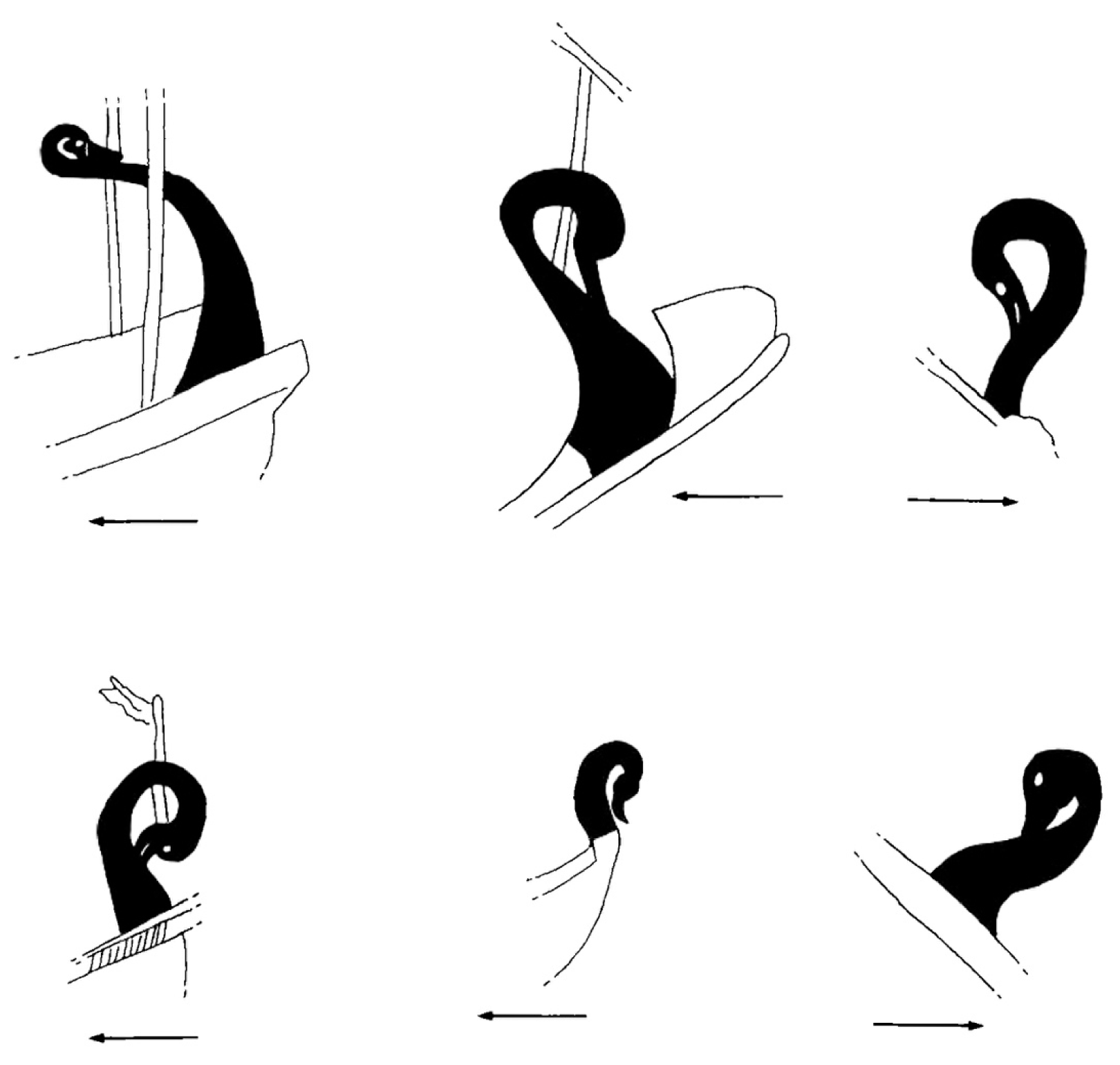

- They are highly decorated and carry ornamented bowsprits missing on the functional ships.

- While the processional ships have masts and sails, in all cases, the sails, and sometimes also the masts, have been lowered.

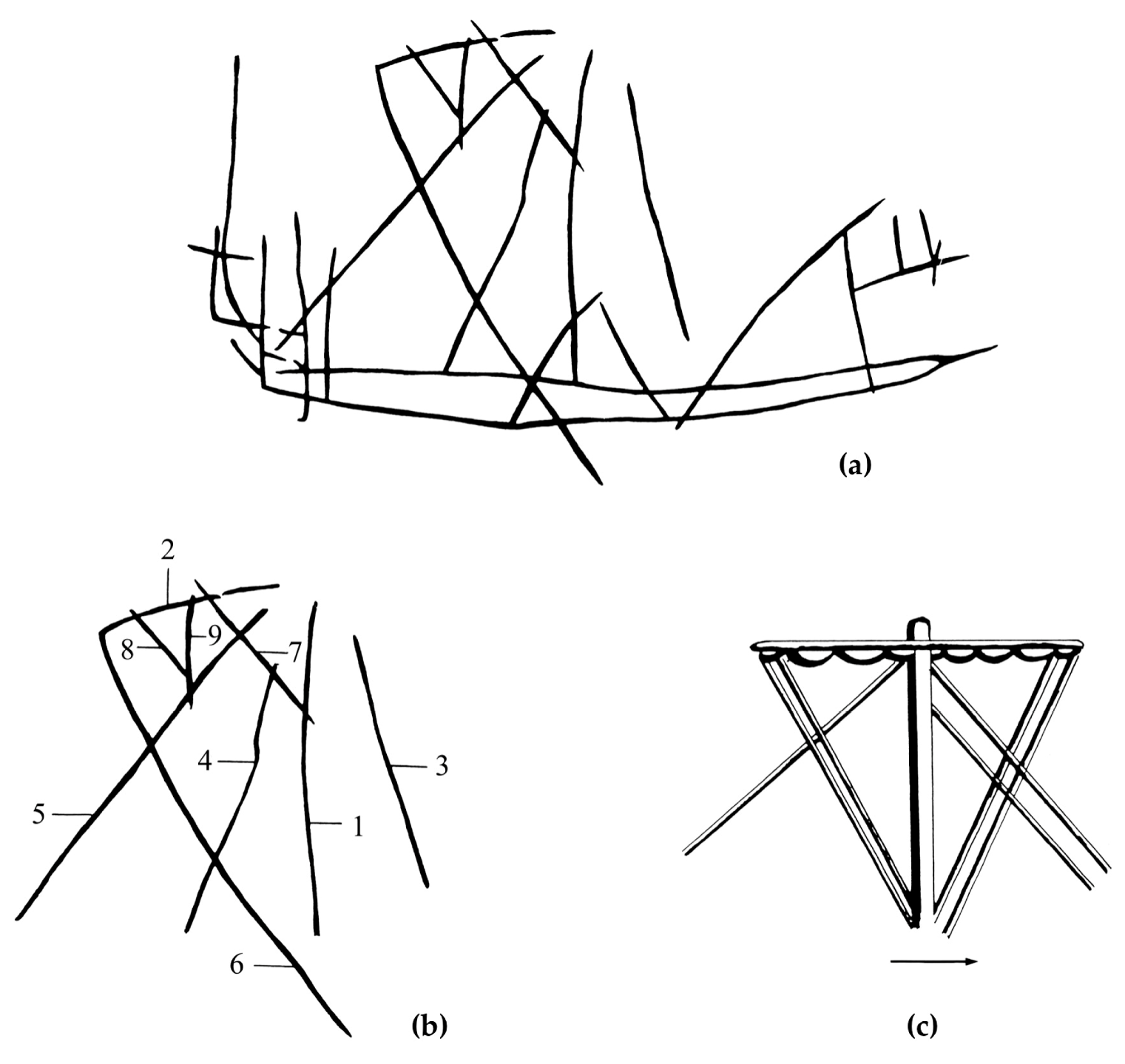

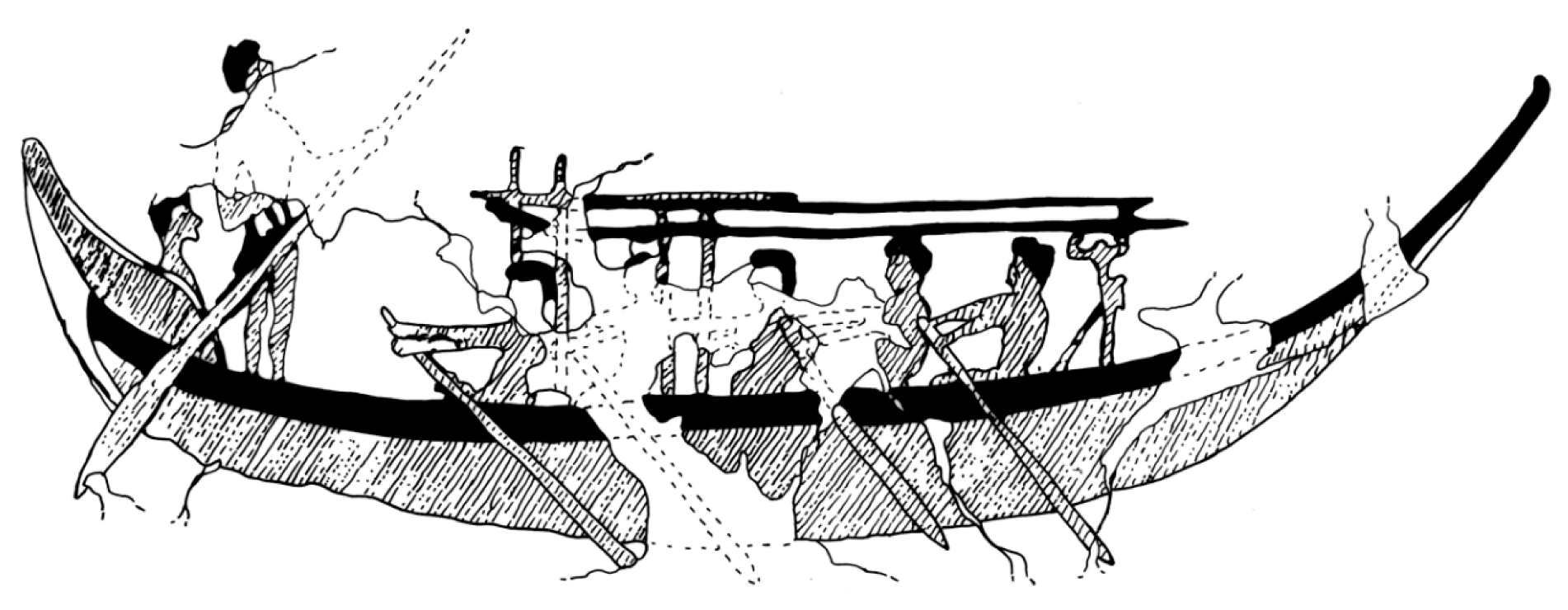

- Perhaps most surprisingly, the ships move under paddles, not oars. The awkward manner in which the paddlers strain, bending over the sides of the hull, makes it abundantly clear that paddling was not the accustomed manner of propulsion for these vessels (Figure 29a and Figure 30). Furthermore, in the same scene, a vessel accompanying the procession moves under oar, which indicates that the Therans knew both forms of propulsion well (Figure 28a [far left of scene] and Figure 31).

- However, for the present discussion, the most significant factor is that each of the processional ships carries a horizontal device under its stern (Figure 29b). This extension, repeatedly depicted in great detail in the fresco, appears to be clearly lashed to the sterns of the processional vessels. Those not taking part in the regatta lack the device.

Now, at Athens in Classical times it was the practice to send the embassy to the annual spring festival of Apollo at Delos in a vessel that was so old fashioned that people were able to say it was the one in which Theseus had sailed to Crete. Why not a similar situation here? That the six ships are an archaic style of craft called into use for a special religious ceremony? Either that or they are current models that are deliberately being handled in archaic fashion, as demanded by the ceremony in which they take part?

9. Corpus Delicti

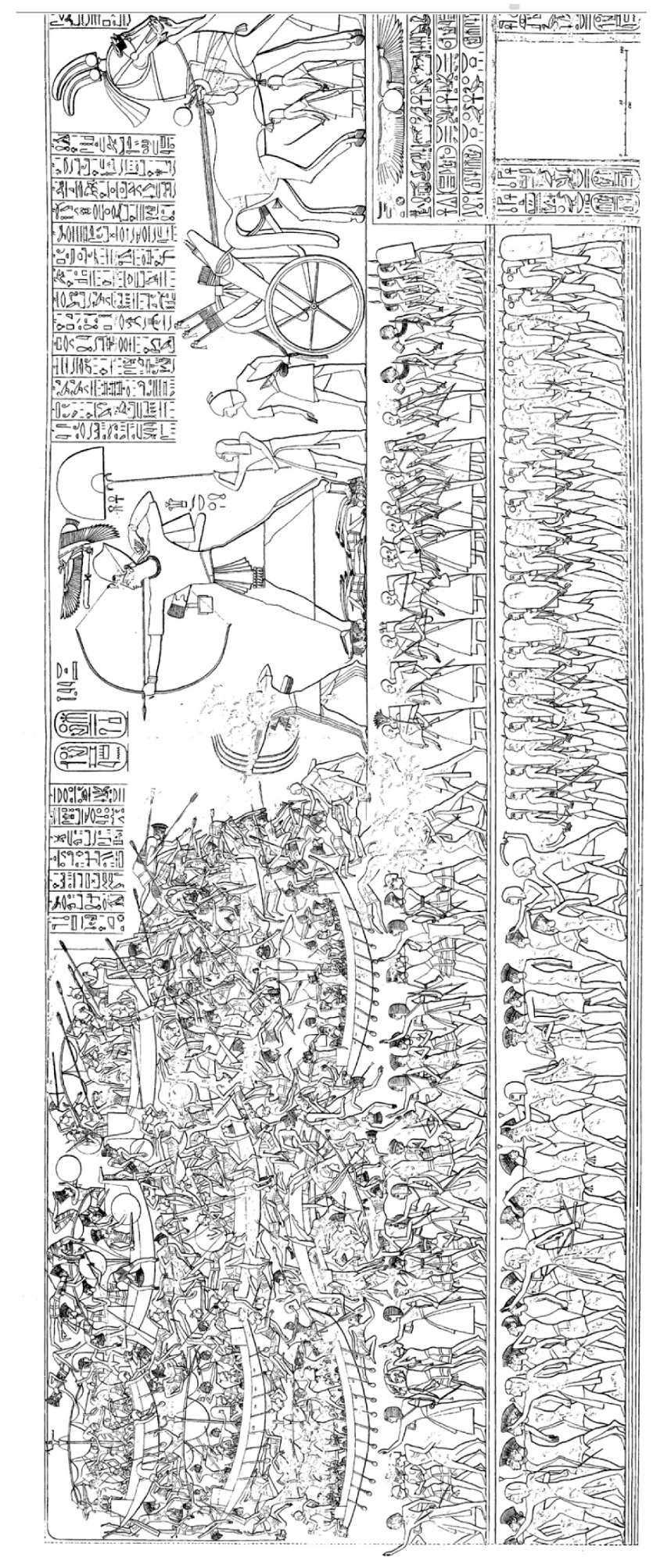

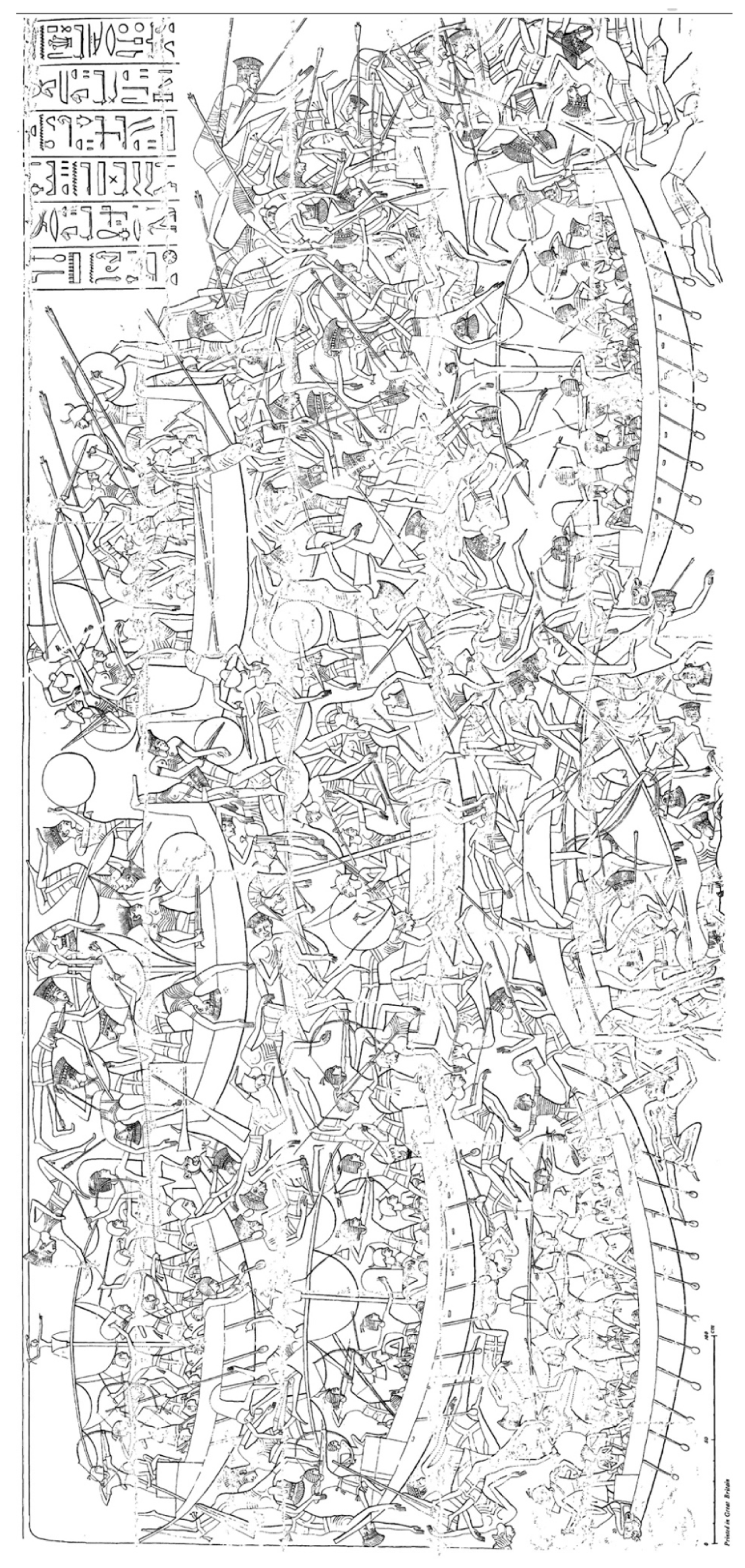

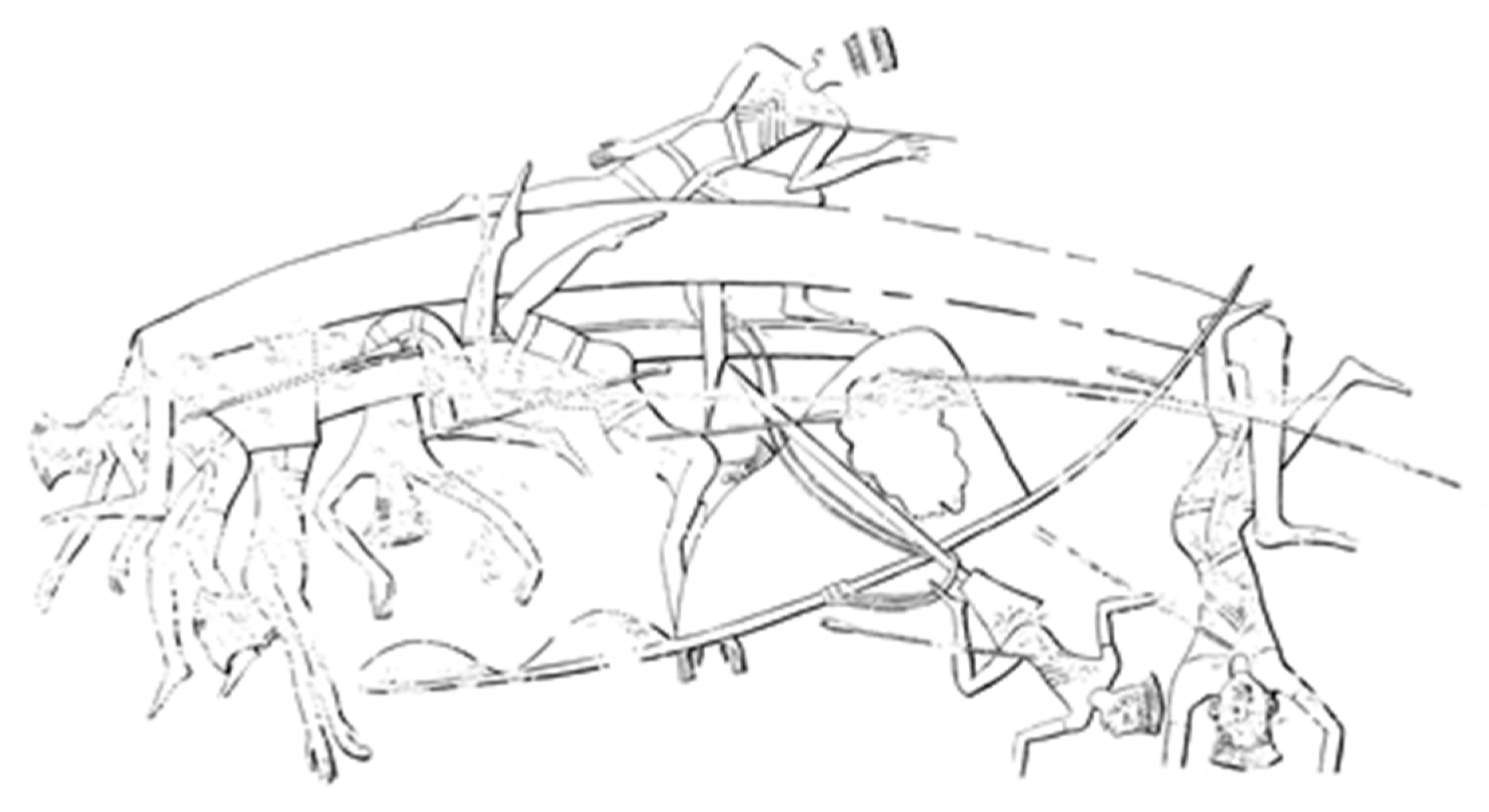

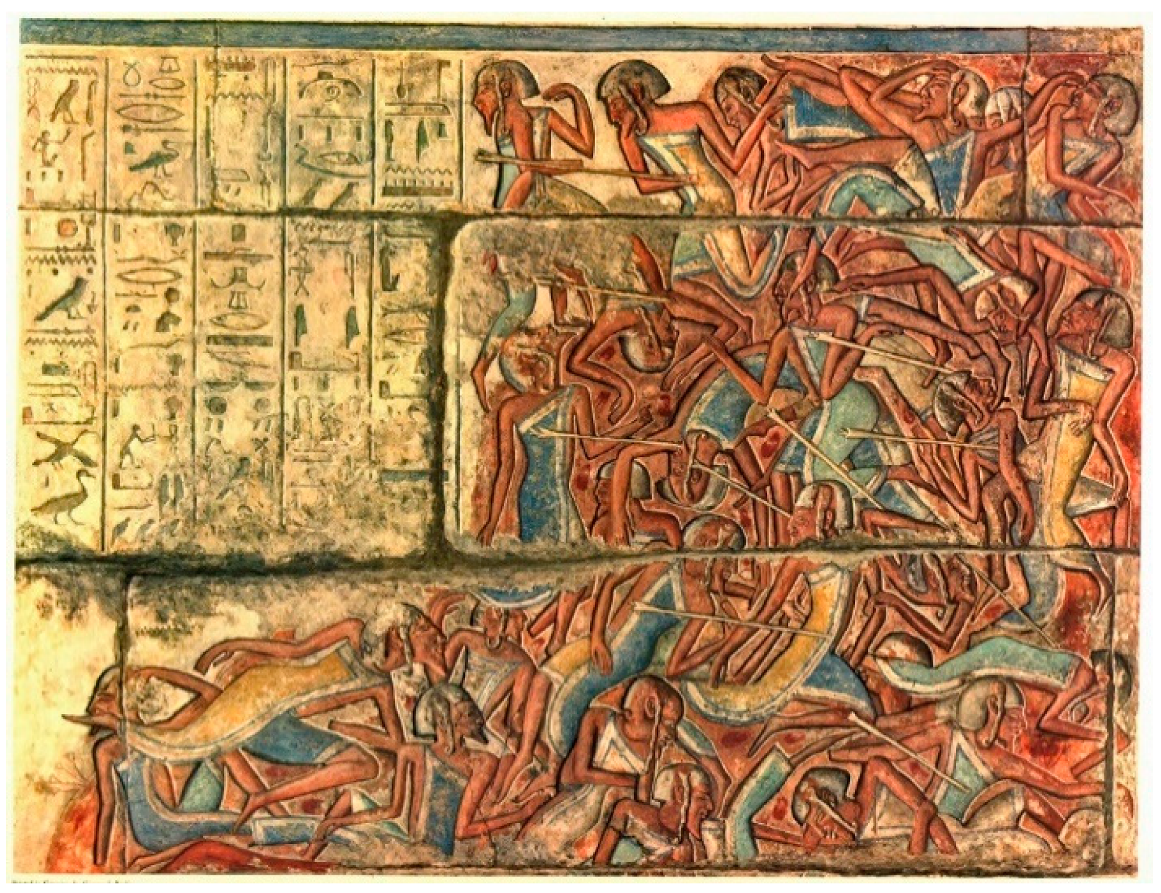

Here, in the upper portions of the relief, even the water-color paint is unusually well preserved, and we find that the bare sculpture has been extensively supplemented by painted details distinctly enriching the composition. The colors of the garments worn by the Libyans clearly stand out. Between the bodies of the slain as they lie upon the battlefield appear pools of blood. The painter has suggested the presence of the open country by painting in wild flowers that spring up among the dead. Moreover, it is apparent that the action takes place in a hilly region, for streams of blood run down between the bodies as the enemy attempt to escape across the hills from the Pharaoh’s pursuing shafts. The details of the monarch’s accouterments are indicated in color, relieving him of the almost naked appearance that is often presented by his sculptured figure when divested of its paint. It is not infrequent to find such details as bow strings or lance shafts partly carved and partly represented in paint. The characteristic tattoo marks on the bodies of the Tjemhu are also only painted in pigment. When all of these painted details have disappeared, though the sculptured design might remain in fairly good condition, much of the life of the original scene is gone and many aids to its interpretation are lost.

10. Size Does Matter

11. To Be or Not to Be

12. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Glossary of Nautical Terms

| APHLASTON | Sternpost ornament, typically carried by warships beginning in the Classical period |

| AFTER OR AFT | Toward the stern. |

| ARTEMON | Foresail. |

| BACKSTAY | An element of the standing rigging that provides longitudinal support to the mast running aft from the top of the mast. |

| BOOM | A spar used to spread the foot of a sail. |

| BOWSPRIT | A spar extending forward from the bow. |

| BRACE | Rigging element attached to a yard’s extremities to control a square sail’s angle to the wind. |

| BRAILED SAIL | A rig that employs brailing lines, also known as brails, to control the amount of sail exposed to the wind as well as for determining the sail’s geometry. |

| BRAILING LINES (BRAILS) | Lines attached at intervals to the foot of the sail and brought vertically up through “brailing rings” or “brailing fairleads” sewn to the sail. The lines are carried up over the yard and then brought astern in a bunch. Sail is controlled in a manner similar to that of modern Venetian blinds. |

| CROWS NEST | Platform, often enclosed, near or at the top of the mast for a lookout. |

| FORECASTLE | A short, raised deck located in a vessel’s bow. |

| FORESTAY | An element of the standing rigging that provides longitudinal support to the mast running forward from the top of the mast. |

| FURL | To fold up and secure neatly. Used to describe a sail that is in the stored position. |

| GALLEY | A seagoing vessel propelled primarily by oar. Galleys usually carried sail also. |

| GUNWALE | Uppermost run of planking on a vessel’s side. |

| HALYARDS | Lines used to position the yard. |

| HOGGING TRUSS | An arrangement of ropes running over stanchions connecting a vessel’s extremities to prevent vertical distortion of the hull in which the ends sag and the midship area rises. |

| KEEL | The primary longitudinal central timber of most vessels. |

| LIFT | A line running from the masthead that supports a yard or a boom. |

| LINES DRAWINGS | A hull’s shape expressed by geometric progressions, normally including profile, front, back and top views. |

| QUARTER RUDDER | A rudder that is affixed to a vessel at the side in the stern. |

| SHEER PLAN | Plan view of a hull as seen from the side. |

| STANCHION | A load-bearing vertical post. |

| STARBOARD | Right. |

| STEM | The upright timber attached to the forward extremity of the keel or keel plank. |

| TABERNACLE | A base that permits the mast to be stepped or struck. |

| TRANSOM | A flat transverse plane forming a vessel’s stern. |

| TUTELA | Likeness of a ship’s guardian deity. |

| WINDWARD | Towards the direction of the wind. |

| YARD | A spar used to spread a square sail on a mast. |

References

- Avi-Yonah, Michael. 1982. The Mosaics of Mopsuestia—Church or Synagogue? In Ancient Synagogues Revealed. Edited by Lee I. Levine. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, Detroit: Wayne State University Press, pp. 186–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bachhuber, Christoph. 2013. Review: The Gurob Ship-Cart Model and Its Mediterranean Context by Shelley Wachsmann. INA Quarterly 40: 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard, Robert Duane. 2001. Deep Black Sea. National Geographic Magazine 199: 52–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard, Robert Duane, Ann Margaret McCann, Dana Yoerger, Louis Whitcomb, David Mindell, John Oleson, Hanumant Singh, Brendon Foley, John Adams, Dennis Piechota, and et al. 2000. The Discovery of Ancient History in the Deep Sea Using Advanced Deep Submergence Technology. Deep-Sea Research I 47: 1591–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basch, Lucien. 1975. Another Punic Wreck in Sicily: Its Ram 1. A Typological Sketch. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 4: 201–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basch, Lucien. 1978. Le navire mnš et autres notes de voyage in Égypte. Mariner’s Mirror 64: 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basch, Lucien. 1987. Le musée imaginaire de la marine antique. Athens: Hellenic Institute for the Preservation of Nautical Tradition. [Google Scholar]

- Basch, Lucien, and Michal Artzy. 1985. App. 2. Ship Graffiti at Kition. In Excavations at Kition V: I: The Pre-Phoenician Levels, Areas I and II. Edited by Karageorghis Vassos and M. Demas. Nicosia: Department of Antiquities, pp. 322–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bascom, Willard. 1976. Deep Water, Ancient Ships: The Treasure Vault of the Mediterranean. Garden City: Doubleday & Company, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, George Fletcher, ed. 1967. Cape Gelidonya: A Bronze Age Shipwreck. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, N.S 57: 8. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, George Fletcher. 1972. The Earliest Seafarers in the Mediterranean and the Near East. In A History of Seafaring Based on Underwater Archaeology. Edited by George F. Bass. New York: Walker and Company, pp. 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, George Fletcher. 1976. Archaeology Beneath the Sea. New York: Harper Colophone Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, George F. 1987. Oldest Known Shipwreck Reveals Bronze Age Splendors. National Geographic Magazine 172: 693–733. [Google Scholar]

- Beaux, Nathalie. 1990. Le cabinet de curiosités de Thoutmosis III. Orientalia Lovanensia Analecta 36. Louvain: Dép. Oriëntalistiek. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, Jack L. 1961. A Problem in Orientalizing Cretan Birds: Mycenaean or Philistine Prototypes? Journal of Near Eastern Studies 20: 73–84, pls. 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, Jack L. 1975. Birds on Cypro-Geometric Pottery. In The Archaeology of Cyprus: Recent Developments. Edited by N. Robertson. Park Ridge: Noyes Press, pp. 129–50. [Google Scholar]

- Betts, John H. 1968. Trees in the Wind on Cretan Sealing. American Journal of Archaeology 72: 149–50, pl. 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, John H. 1973. Ships on Minoan Seals. In Marine Archaeology, Paper presented at the Twenty-Third Symposium of the Colston Research Society, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK, April 4–8. Edited by D. J. Blackman. London: Archon Books, pp. 325–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Robert S. 1997. The Theban Landscape of Rameses II. In Ancient Egypt, The Aegean and the Near East: Studies in Honor of Martha Rhoads Bell. Edited by Jack Phillips. San Antonio: Van Siclen Books, pp. 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Biebel, F. M. 1938. The Mosaics. In Gerasas: City of the Decapolis. Edited by Carl H. Kraeling. New Haven: American Schools of Oriental Research, pp. 297–352. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman, John. 1967. The Khaniale Tekke Tombs, II. Annual of the British School at Athens 62: 57–75, pls. 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenheimer, Shimon Fritz. 1949. Animal Life in Biblical Lands: From the Stone Age to the End of the Nineteenth Century. Jerusalem: Bialik Institute, vol. I. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer, Shimon Fritz. 1960. Animal and Man in Bible Lands: Text. Collection de travaux de l‘Académie international d’histoire des sciences 10. Lieden: E.J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer, Shimon Fritz. 1972. Animal and Man in Bible Lands: Figures and Plates. Collection de travaux de l’Académie international d’histoire des sciences 10. Lieden: E.J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Breasted, James Henry, ed. 1988. Ancient Records of Egypt. 5 vols, London: Histories & Mysteries of Man Ltd, (Reprint). [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, Michael L., Dan Davis, Chris Roman, Ilya Buynevich, Alexis Catsambis, Meko Kofahl, Derya Ürkmez, J. Ian Vaughn, Maureen Merrigan, and Muhammet Duman. 2013. Ocean Dynamics and Anthropogenic Impacts along the southern Black Sea Shelf Examined through the Preservation of Pre-Modern Shipwrecks. Continental Shelf Research 53: 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britt, Karen, and Raanan Boustan. 2019. Artistic Influences in Synagogue Mosaics: Putting the Huqoq Synagogue in Context. Biblical Archaeology Review 45: 39–45, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Broad, William J. 2016. ‘We Couldn’t Believe Our Eyes:’ A Lost World of Shipwrecks is Found. New York Times. November 12. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/12/science/shipwrecks-black-sea-archaeology.html?_r=0 (accessed on 21 August 2019).

- Bruni, Stefano, and Marta Abbado. 2000. Le Navi Antiche di Pisa: Ad un anno Dall’inizio delle Ricerche. Firenze: Editizioni Polistampa. [Google Scholar]

- Budde, Ludwig. 1960. Die frühchristlichen Mosaiken von Misis-Mopsuhestia in Kilikien. Pantheon 18: 116–26. [Google Scholar]

- Budde, Ludwig. 1969. Antike Mosaiken in Kilikien. Recklinghausen: Aurel Bongers, vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- Camilli, Andrea, and Elisabetta Setari, eds. 2005. Ancient Shipwrecks of Pisa: A Guide. Milano: Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici della Toscana and Mondadori Electa S.p.A. [Google Scholar]

- Cariolou, Glafkos A. 1997. KYRENIA II: The Return from Cyprus to Greece of the Replica of a Hellenic Merchant Ship. In Res Maritimae: Cyprus and the Eastern Mediterranean from Prehistory to Late Antiquity, Paper presented at the Second International Symposium “Cities on the Sea”, Nicosia, Cyprus, October 18–22. Cyprus American Archaeological Research Institute Monograph Series; vol. 1, Edited by Stuart Swiny, Robert L. Hohlfelder and Helena Wylde Swiny. Atlanta: Scholars Press, pp. 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Tristan, Daniel A. Contreras, Justin Holcomb, Danica D. Mihailović, Panagiotis Karkanas, Guillaume Guérin, Ninon Taffin, Dimitris Athanasoulis, and Christelle Lahaye. 2019. Earliest Occupation of the Central Aegean (Naxos), Greece: Implications for Hominin and Homo Sapiens’ Behavior and Dispersals. Science Advances 5. Available online: https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/5/10/eaax0997 (accessed on 27 October 2019). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casson, Lionel. 1975. Bronze Age Ships. The Evidence of the Thera Wall Paintings. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 4: 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casson, Lionel. 1995. Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World. Reprint with addenda and corrigenda 1971. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coldstream, John Nicolas. 2006. Geometric Greece: 900-700 BC. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, John E. 1985. “Frying Pans” of the Early Bronze Age Aegean. American Journal of Archaeology 89: 191–219, pls. 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbo, Virgilio P. 1978. Piazza e villa urbana a Magdala. Liber Annuus 28: 232–40, pls. 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Dakoronia, Fanouria. 1990. War-Ships on Sherds of LH IIIC Kraters from Kynos. In Tropis, Paper presented at the 5th International Symposium on Ship Construction in Antiquity, Delphi, Greece, August 27–29. Edited by Harry Tzalas. Athens: Hellenic Institute for the Preservation of Ship Construction in Antiquity, vol. II, pp. 117–22. [Google Scholar]

- Dakoronia, Fanouria. 1995. Editor’s Note (War-Ships on Sherds of LH IIIC Kraters from Kynos?). In Tropis, Paper presented at the 3rd International Symposium on Ship Construction in Antiquity, Athens, Greece, August 24–27. Edited by Harry Tzalas. Athens: Hellenic Institute for the Preservation of Ship Construction in Antiquity, vol. III, pp. 147–48. [Google Scholar]

- Dakoronia, Fanouria. 2006. Mycenaean Pictorial Style at Kynos, East Lokris. In Pictorial Pursuits: Figurative Painting on Mycenaean and Geometric Pottery. Papers from Two Seminars at the Swedish Institute at Athens in 1999 and 2001. Edited by Eva Rystedt and Berit Wells. Stockholm: Svenska Institutet i Athen, pp. 23–29. [Google Scholar]

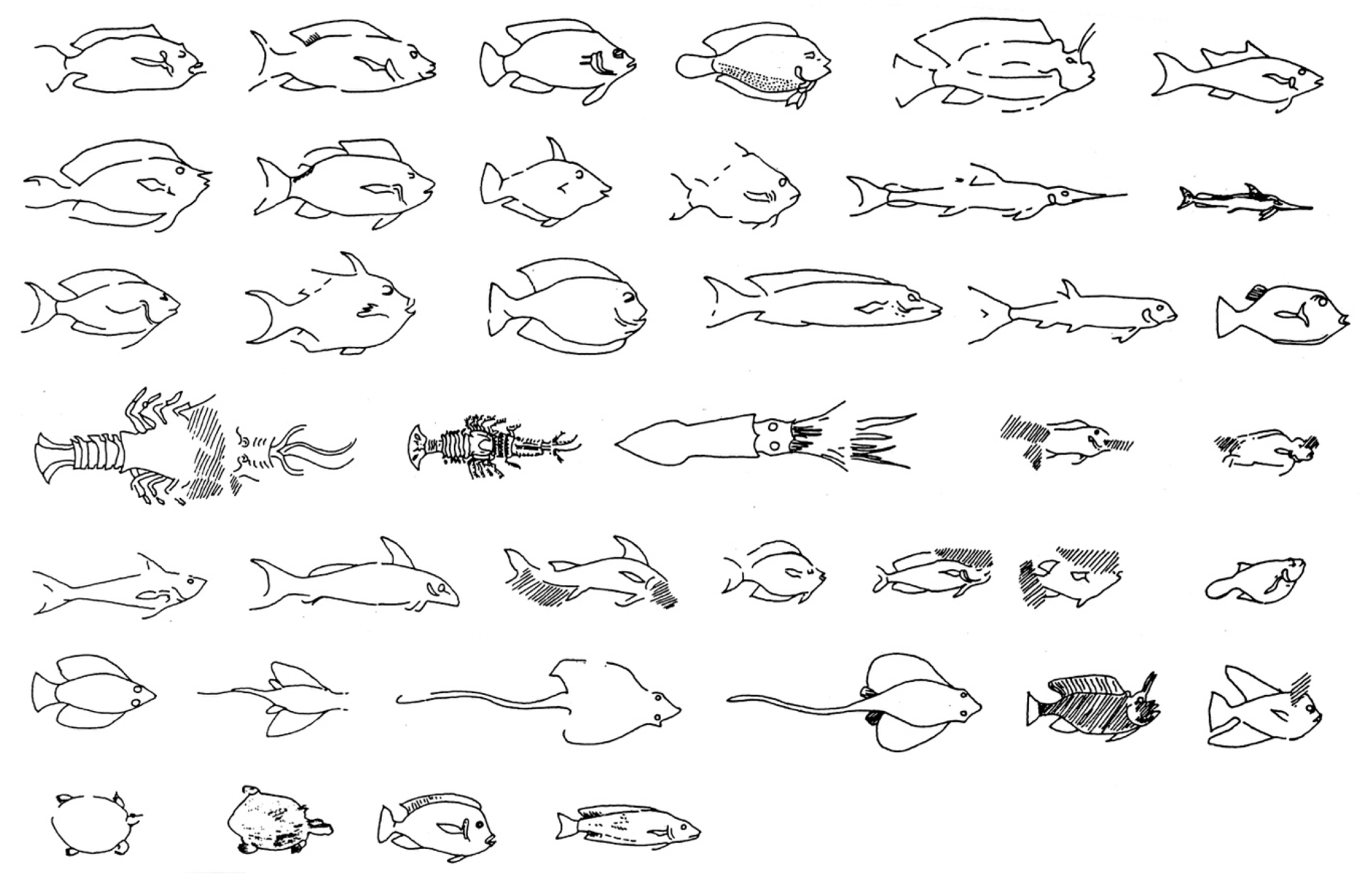

- Danelius, Eva, and Heinz Steinitz. 1967. The Fishes and Other Aquatic Animals on the Punt-Reliefs at Deir El-Bahri. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 53: 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Daressy, George. 1895. Une flottille phénicienne d’apres une peinture récente. Revue Archéologique 27: 286–92, pls. XIV–XV. [Google Scholar]

- Dauphin, Claudine. 1978. Byzantine Pattern Books: A Re-examination of the Problem in the Light of the “Inhabited Scroll”. Art History 1: 400–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Nina, and Norman de Garis Davies. 1933. The Tombs of Menkheperrasonb, Amenmose, and Another. Theban Tombs Series V; London: The Egypt Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Norman de Garis. 1930. The Egyptian Expedition: The Work of the Graphic Branch of the Expedition. Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art 25: 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Norman de Garis. 1943. The Tomb of Rech-mi-rē’ at Thebes. Publications of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Egyptian Expedition XI. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, vol. II. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Norman de Garis and Raymond Oliver Faulkner. 1947. A Syrian Trading Venture in Egypt. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 33: 40–6, pl. VIII. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dothan, Trude. 1982. The Philistines and Their Material Culture. New Haven and Jerusalem: Yale University Press and Israel Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Doumas, Christos. 1983. Thera: Pompeii of the Ancient Aegean. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Doumas, Christos. 1992. The Wall-Paintings of Thera. Translated by Alex Doumas. Athens: The Thera Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, Noreen. 1998. Iconography and the Interpretation of Ancient Egyptian Watercraft. Master’s thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Dunand, Maurice. 1937. Fouilles de Byblos: 1926–1932 Atlas. Paris: Librairie orientaliste Paul Geuthner, vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- Dunand, Maurice. 1939. Fouilles de Byblos: 1926–1932 Text. Paris: Librairie orientaliste Paul Geuthner, vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- Edgerton, William F., and John A. Wilson. 1936. Historical Records of Ramses III: The Texts in Medinet Habu. 2 vols, Translated with Explanatory Notes. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization No. 12. Chicago: The Oriental Institute, University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Rainey, Anson Frank, and William M. Schniedewind. 2015. The El-Amarna Correspondence: A New Edition of the Cuneiform Letters from the Site of El-Amarna Based on Collations of All Extant Tablets. 2 vols, Handbook of Oriental Studies 110; Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Epigraphic Survey. 1930. Medinet Habu: Earlier Historical Records of Ramses III. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Arthur. 1964. The Palace of Minos. 4 vols, London: Biblo and Tannen, (Reprint). [Google Scholar]

- Février, James G. 1949–1950. L’ancienne marine phénicienne et les découvertes récentes. La Nouvelle Clio 1–2: 128–43. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel, Irving. 2014. The Ark Before Noah: Decoding the Story of the Flood. New York: Doubletree. [Google Scholar]

- Friedländer, Julius, and Alfred von Sallet. 1877. Das königliche Münzkabinet. Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, Honor. 1969a. The Stone Anchors of Byblos. Melanges de l’Université Saint-Joseph, Beyrouth 45: 425–43, pls. I–VII. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, Honor. 1969b. The Stone Anchors of Ugarit. Ugaritica 6: 235–45. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, Honor. 1991. Anchors Sacred and Profane: Ugarite-Ras Shamra, 1986: The Stone Anchors Revised and Compared. In Ras Shamra-Ougarit VI: Arts et Industries de la Pierre. Edited by Marguerite Yon. Paris and Lyon: Editions Recherche sur les Civilisations and Maison de l’Orient, pp. 355–410. [Google Scholar]

- Furumark, Arne. 1941. The Mycenaean Pottery: Analysis and Classification. Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets, Historie och Atikvitets Akademien. [Google Scholar]

- Glanville, Stephen Ranulph Kingdon. 1931. Records of a Royal Dockyard of the Time of Thutmose III: Papyrus Museum 10056: Part I. Zeitschrift für Agyptische Sprache und Altertumskund 66: 105–21. [Google Scholar]

- Glanville, Stephen Ranulph Kingdon. 1932. Records of a Royal Dockyard of the Time of Thutmose III: Papyrus Museum 10056: Part II. Commentary. Zeitschrift für Agyptische Sprache und Altertumskund 68: 7–41. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, E. Bruce, ed. 2010. Encyclopedia of Perception. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Ltd, vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- Goodenough, Erwin Ramsdell. 1953a. Jewish Symbols in the Greco-Roman Period. The Archaeological Evidence from the Diaspora. Bollinger Series 37; New York: Pantheon Books, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Goodenough, Erwin Ramsdell. 1953b. Jewish Symbols in the Greco-Roman Period. Illustrations. Bollinger Series 37; New York: Pantheon Books, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Grattan, David W. 1987. Waterlogged Wood. In Conservation of Marine Archaeological Objects. Edited by Colin Pearson. London: Butterworths, pp. 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, Robert. 1988. The Greek Myths. 2 vols, Harmondsworth: Penguin, (Reprint). [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Dorothea. 1974. Seewessen. Archaeologia Homerica. Bd. 1, Kapitel G. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Reprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Gressmann, Hugo. 1926–1927. Altorientalische Texte Zum Alten Testament. 2 vols, Berlin and Leipzig: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Gressmann, Hugo. 1980. Jewish Life in Ancient Rome. In Jewish Studies in Memory of Israel Abrahams by the Faculty and Visiting Teachers of the Jewish Institute of Religion. Edited by the Alexander Kohut Memorial Foundation. New York: Arno Press, pp. 170–91. [Google Scholar]

- Grimal, Nicholas-Christophe. 1992. A History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford and Cambridge: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Guttandin, Thomas. 2009. Vom Einbaum zum Plankeschiff: “Geschnäbelte” Boote als Konstruktionsprinzip im mittelminoischen Schiffsbau. Skyllis (Deutsche Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Unterwasserarchäeologie e.V.) 9: 124–37. [Google Scholar]

- Guttandin, Thomas, Diamantis Panagiotopoulos, and Gerhard Plath. 2010. Die Inseln der Winde: Die experimentelle Archäologie lässt Minos’ Flotte wieder segeln. Ruperto Carola (Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidleberg) 2: 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Guttandin, Thomas, Diamantis Panagiotopoulos, Hermann Pflug, and Gerhard Plath. 2011. Inseln der Winde: Die Maritime Kultur der bronzezeitlichen Ägäis. Heidelberg: Institut für Klassische Archäologie der Universität Heidelberg. [Google Scholar]

- Hammacher, Abraham Marie. 1985. René Magritte. Translated by James Brockway. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Herdendorf, Charles E., Tommy Thompson, and Robert D. Evans. 1995. Science on a Deep-Ocean Shipwreck. The Ohio Journal of Science 95: 4–224. [Google Scholar]

- Hocker, Frederick M. 1998a. Appendix: Did Hatshepsut’s Punt Ships Have Keels? In Shelley Wachsmann, Seagoing Ships and Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant. College Station and London: Texas A&M University Press and Chatham Press, pp. 245–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hocker, Frederick M. 1998b. Glossary of Nautical Terms. In Shelley Wachsmann, Seagoing Ships and Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, London: Chatham Press, pp. 377–81. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmeier, James K. 2018. A Possible Location in Northwest Sinai for the Sea and Land Battles between the Sea Peoples and Ramesses III. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 380: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornell, James. 1938a. Boat Oculi Survivals: Additional Records. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 68: 339–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornell, James. 1938b. Boat Processions in Egypt. Man 38: 145–46, pls. I–J. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornell, James. 1943. The Prow of the Ship: Sanctuary of the Tutelary Deity. Man 43: 121–28, pl. B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornell, James. 1970. Water Transport: Origins and Early Evolution. Reprint 1946. Newport Abbot: David & Charles. [Google Scholar]

- Ingholt, Harald. 1940. Rapport Préliminaire sur sept Campagnes de Fouilles à Hama en Syrie (1932–1938). Copenhagen: E. Munksgaard. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, Robin M. 2007. Early Christian Images and Exegesis. In Picturing the Bible: The Earliest Christian Art. Edited by Jeffrey Spier. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, Paul F. 1982. Bronze Age Cycladic Ships: An Overview. In Temple University Aegean Symposium 7. Paper presented at the Symposium Trade and Travel in the Cyclades during the Bronze Age, Department of Art History, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA, March 5; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, Paul. 1973. Stern First in the Stone Age? International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 2: 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Dilwyn. 1990. Model Boats from the Tomb of Tut‘Ankhamūn. Tut’ankhamūn’s Tomb Series 9; Oxford: Griffith Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, Daniel. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [Google Scholar]

- Karageorghis, Vassos, and Jean Des Gagniers. 1974. La céramique chypriote de style figuré. Âge du fer (1050–500 Av. J.-C.): Illustrations et Descriptions des Vases. Rome: Edizioni dell’Ateneo. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, Herbert L. 2007. The Word Made Flesh in Early Decorated Bibles. In Picturing the Bible: The Earliest Christian Art. Edited by J. Spier. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 141–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, Geoffrey Stephen. 1949. Ships on Geometric Vases. Annual of the British School at Athens 44: 93–153, pls. 38–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchen, Kenneth A. 1971. Punt and How to Get There. Orientalia 40: 184–207. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Reven Chaim. 2016. A Tale of Two Arks. Ohr Somayach. September 24. Available online: https://ohr.edu/7030 (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Kloner, Amos, and Shelley Wachsmann. 1978. A Ship Graffito from Khirbet Rafi. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 7: 227–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeyer, Jan. 1969. Deterioration of Wood by Marine Fungi in the Deep Sea. In Symposium on Materials Performance and the Deep Sea. (1969). Materials Performance and the Deep Sea. Philadelphia: American Society for Testing and Materials, pp. 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Korrés, George S. 1989. Representation of a Late Mycenaean Ship on the Pyxis from Tragana, Pylos. In Tropis, Paper presented at the First International Symposium on Ship Construction in Antiquity, Piraeus, August 30–September 1. Edited by Harry Tzalas. Athens: Hellenic Institute for the Preservation of Nautical Tradition, vol. I, pp. 177–202, 199, (In Greek with English summary). [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen, Kristian. 2019. Representations of Representations: Rock Art, Miniatures and Models. In Tidens landskap: En vänbok till Anders Andrén. Edited by Cecilia Ljung, Anna Andreassen Sjogren, Ingrid Berg, Elin Engstrom, Ann-Mari Ha, Hans Stenholm, Kristina Jonsson, Alison Klevnas, Linda Qvistrom and Torun Zachrisson. Lund: Nordic Academic Press, pp. 65–67. [Google Scholar]

- Landström, Bjorn. 1970. Ships of the Pharaohs. Garden City: Doubleday & Company, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Legrain, George. 1917. Le logement et transport des barques sacrées et des statues des dieux dans quelques temples égyptiens. Bulletin de L’institut Français D’archéologie Orientale 13: 1–76, pls. I–VII. [Google Scholar]

- Lenz, John R. 1998. Appendix: Homer’s νηυσὶ κορωνίσιν. In Shelley Wachsmann, Seagoing Ships and Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant. College Station and London: Texas A&M University Press and Chatham Press, pp. 199–200. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Charlotte R. 1974. The Ayia Triadha Sarcophagus: A Study of Late Minoan and Mycenaean Funerary Practices and Reliefs. Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology 41. Göteborg: P. Åstrom. [Google Scholar]

- Magness, Jodi, Shua Kisilevitz, Matthew Grey, Dennis Mizzi, Daniel Schindler, Martin Wells, Karen Britt, Raanan Boustan, Shana O’Connell, Emily Hubbard, and et al. 2018. The Huqoq Excavation Project: 2014–2017 Interim Report. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 380: 61–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magness, Jodi, Shua Kislilevitz, Matthew Grey, Dennis Mizzi, Karen Britt, and Raanan Boustan. 2019. Inside the Huqoq Synagogue. Biblical Archaeology Review 45: 24–38. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, S. W. 2010. Chronology and Terminology. In The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean (ca. 3000–1000 BC). Edited by Eric H. Cline. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Marinatos, Spyridon. 1933. La marine créto-mycénienne. Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 57: 170–235, pls. XIII–XVII. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinatos, Spyridon. 1974. Excavations at Thera. (1972 Season), Text and Plates. Athens: Bibliotheke tes en Athenais Archaeiologikes Etaireias, vol. VI. [Google Scholar]

- Mark, Samuel. 2005. Homeric Seafaring. College Station: Texas A&M Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mark, Samuel. 2017. The Depiction in the Tomb of Nebamun: The Earliest Egyptian Ship without a Hogging Truss. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 16: 68–86. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Geoffrey Thorndike. 1991. The Hidden Tombs of Memphis: New Discoveries from the Time of Tutankhamun and Ramses the Great. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Mazar, Amihai. 1990. Archaeology of the Land of the Bible: 10,000–586 B.C.E. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Mazar, Amihai. 1992. The Iron Age I. In The Archaeology of Ancient Israel. Edited by A. Ben-Tor. West Hanover: Yale University Press and The Open University of Israel, pp. 258–301. [Google Scholar]

- Meiberg, Linda Gail. 2011. Figural Motifs on Philistine Pottery and Their Connections to the Aegean World, Cyprus and Coastal Anatolia. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Merriman, Ann. 2011. Egyptian Watercraft Models from the Predynastic to Third Intermediate Periods. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Miriam Webster s.v. Occam’s Razor. n.d. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Occam%27s%20razor (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Monroe, Christopher Mountfort. 2009. Scales of Fate: Trade, Tradition, and Transformation in the Eastern Mediterranean ca. 1350–1175 BCE. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Lyvia. 1988. The Miniature Wall Paintings of Thera: A Study in Aegean Culture and Iconography. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, John Sinclair, and R. T. Williams. 1968. Greek Oared Ships: 900–322 B.C. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mountjoy, Penelope A. 2005. Mycenaean Connections with the Near East in LH IIIC: Ships and Sea Peoples. Emporia: Aegeans in the Central and Eastern Mediterranean. Paper presented at the 10th International Aegean Conference/10e Rencontre égéenne internationale, Athens Italian School of Archaeology, Athina, Athens, April 14–18; Edited by Robert Laffineur and E. Greco. Liège and Austin: University of Liège Histoire de l’Art et Archéologie de la Grèce Antique and University of Austin Program in Aegean Scripts and Prehistory, pp. 423–27, pls. XCV–XCVIII. [Google Scholar]

- Mountjoy, Penelope A. 2006. Mycenaean Pictorial Pottery from Anatolia in the Transitional LH IIIB2–LH IIIC Early and the LH IIIC Phases. In Pictorial Pursuits: Figurative Painting on Mycenaean and Geometric Pottery, Papers from the Two Seminars at the Swedish Institute in 1999 and 2001. Edited by E. Rystedt and B. Wells. Stockholm: Svenska Institutet i Athen, pp. 107–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mountjoy, Penelope Anne. 2011. A Bronze Age Ship from Ashkelon with Particular Reference to the Bronze Age Ship from Bademgediği Tepe. American Journal of Archaeology 115: 483–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muckelroy, Keith. 1978. Maritime Archaeology. London: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, W. Max. 1904. Neue Darstellungen “mykenischer” Gesandter und phönizischer Schiffe in altägyptischen Wandgemälden. Mitteilungen der Vorderasiatischen Gesellschaft 9: 113–80, Tafs. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Muraoka, T. 2009. A Greek-English Lexicon of the Septuagint. Louvain, Paris and Walpole: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Naville, Edouard. 1898. The Temple of Deir el Bahri: End of the Northern half and Southern Half of the Middle Platform. London: Egypt Exploration Fund, vol. III. [Google Scholar]

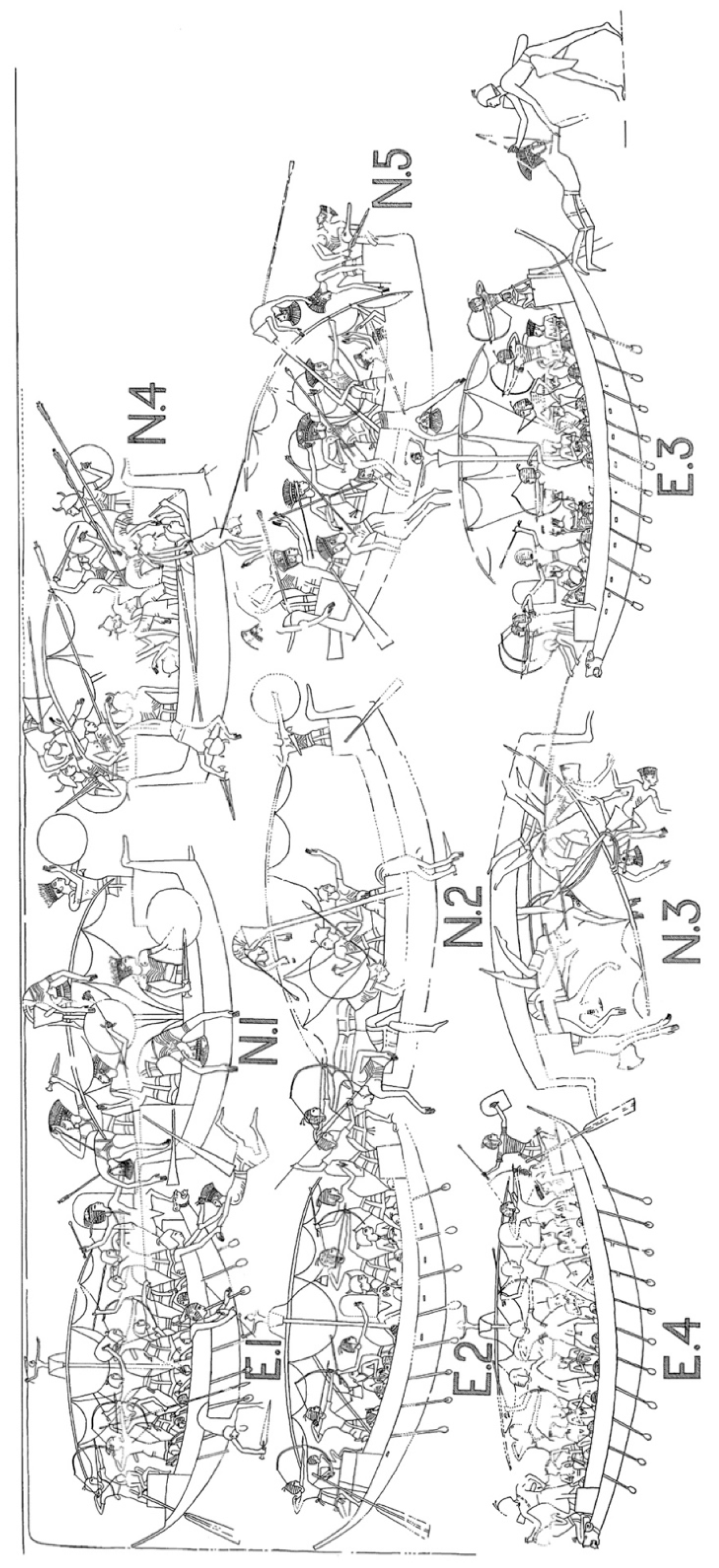

- Nelson, Harold H. 1929. The Epigraphic Survey of the Great Temple of Medinet Habu (Seasons 1924–1925 to 1927–1928). Medinet Habu 1924–1928. Oriental Institute Communications 5: 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Harold H. 1943. The Naval Battle Pictured at Medinet Habu. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 2: 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, Troy Joseph. 1999. A Marble Ophthalmos from Tektaș Burnu. INA Quarterly 26: 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, Troy Joseph. 2001. A Preliminary Report on Ophthalmoi from the Tektaș Burnu Shipwreck. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 30: 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, Troy Joseph. 2006. Archaeological Evidence for Ship Eyes: An Analysis of their Form and Function. Master’s thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Onassoglou, Artemis. 1985. Die >Talismanischen< Siegel. Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Öniz, Hakan. 2019. A New Bronze Age Shipwreck with Ingots in the West of Antalya—Preliminary Results. Palestine Exploration Quarterly 151: 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanassoglou, D. A., and Ch. A. Georgouli. 2009. The ‘Frying Pans’ of the Early Bronze Age Aegean: An Experimental Approach to Their Possible Use as Liquid Mirrors. Archaeometry 51: 658–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, William H. 1978. Egyptian Drawing. New York: E.P. Dutton. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, Ralph Kenneth. 2005. Was Noah’s Ark a Sewn Boat? Biblical Archaeology Review 31: 18–23, 55–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, Ralph Kenneth. 2003. The Boatbuilding Sequence in the Gilgamesh Epic and the Sewn Boat Relation. Ph.D. dissertation, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Bertha, and Rosalind Louisa Beaufort Moss. 1981. Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs, and Paintings III: Memphis; Part 2. Saqqâra to Dahshûr, 2nd ed. Revised and Augmented by Jaromír Málek. Oxford: Griffith Institute, Ashmolean Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, James B. 1951. Syrians as Pictured in the Paintings of the Theban Tombs. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 122: 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulak, Cemal Mustafa. 1992. The Shipwreck at Ulu Burun, Turkey: 1992 Excavation Season. INA Quarterly 19: 4–11, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Pulak, Cemal. 1995. Das Shiffswrack von Uluburun. In Poseidons Reich: Archäologie unter Wasser. Zaberns Bildbände zur Archäologie 23. Mainz: P. von Zabern, pp. 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Pulak, Cemal. 2008. The Uluburun Shipwreck and Late Bronze Age Trade. In Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C. Edited by Joan Aruz, Kim Benzel and Jean M. Evans. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 288–305, artifact catalogue, pp. 306–10, 313–21, 324–33, 336–48, 350–58, 366–70, 372–78, 382–85. [Google Scholar]

- Rainey, Anson Frank. 1963. A Canaanite at Ugarit. Israel Exploration Journal 13: 43–5. [Google Scholar]

- Rainey, Anson Frank. 1967. A Social Structure of Ugarit. Jerusalem: Mosad Byalik. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Rainey, Anson Frank. 1996. Who Is a Canaanite? A Review of the Textual Evidence. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 304: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainey, Anson Frank, and R. Steven Notley. 2006. The Sacred Bridge: Carta’s Atlas of the Biblical World. Jerusalem: Carta. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, Ronny. 1991. A Note on the Roman Mosaic at Magdala on the Sea of Galilee. Liber Annuus 41: 455–58, pls. 53–54. [Google Scholar]

- Reisner, George Andrew. 1913. Models of Ships and Boats. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale. [Google Scholar]

- Renfrew, Colin. 1967. Cycladic Metallurgy and the Aegean Early Bronze Age. American Journal of Archaeology 71: 1–20, pls. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieth, Eric. 2016. Navires et Construction Navale au Moyen Âge: Archéologie de la Baltique à la Méditerranée. Paris: Picard. [Google Scholar]

- Riis, Paul Jørgen. 1948. Hama: Fouilles et recherches 1931–1938: Les Cimetières à Crémation. Copenhagen: Gyldendakske Boghandel, Nordisk Forlag, vol. II: 3. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, Alan. 1936. Addendum A: Axe-Head of the Royal Boat-Crew of Cheops (or Sahew-Rā [?]). In A Catalogue of Egyptian Scarabs, Scaraboids, Seals and Amulets in the Palestine Archaeological Museum. Cairo: l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, pp. 283–88. [Google Scholar]

- Säve-Söderbergh, Torgny. 1946. The Navy of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Uppsala: Lundequistska Bokhandeln. [Google Scholar]

- Säve-Söderbergh, Torgny. 1957. Four Eighteenth Dynasty Tombs. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer, Heinrich. 1974. Principles of Egyptian Art. Translated by John Baines. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Hans D. 1993. The Rediscovery of Iniuia. Egyptian Archaeology 3: 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Maria C. 1982. Ship Cabins of the Bronze Age Aegean. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 11: 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shirley, J. J. 2007. The Life and Career of Nebamun, the Physician of the King in Thebes. In The Archaeology and Art of Ancient Egypt: Essays in Honor of David B. O’Connor. Annales du service des antiquités de l’Égypte. Edited by Zahi A. Hawass and Janet Richards. Cairo: Conseil suprême des antiquités de de l’Égypte, pp. 381–401. [Google Scholar]

- Sylvester, David. 1992. Magritte: The Silence of the World. New York: Menil Foundation, Harry N. Abrams, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöquist, Erik. 1940. Problems of the Late Cypriote Bronze Age. Stockholm: Swedish Cyprus Expedition. [Google Scholar]

- Spier, Jeffrey, ed. 2007a. Picturing the Bible: The Earliest Christian Art. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey Spier, ed. 2007b. The Earliest Christian Art: From Personal Salvation to Imperial Power. In Picturing the Bible: The Earliest Christian Art. Jeffrey Spier, ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Stager, Lawrence E., and Penelope Anne Mountjoy. 2007. A Pictorial Krater from Philistine Ashkelon. In Up to the Gates of Ekron: Essays on the Archaeology and History of the Eastern Mediterranean in Honor of Seymour Gitin. Edited by Sidnie White Crawford, Amnon Ben-Tor, Amihai Mazar, William G. Dever and Joseph Aviram. Jerusalem: W.F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research and Israel Exploration Society, pp. 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Steffy, John Richard. 1985. The Herculaneum Boat: Preliminary Notes on Hull Details. American Journal of Archaeology 89: 519–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffy, John Richard. 1990. The Boat: A Preliminary Study of Its Construction. In The Excavations of an Ancient Boat in the Sea of Galilee (Lake Kinneret). Atiqot 19. Edited by Shelley Wachsmann. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, pp. 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- Steffy, John Richard. 1994. Wooden Ship Building and the Interpretation of Shipwrecks. College Station: Texas A&M Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steffy, J. Richard, and Shelley Wachsmann. 1990. The Midgal Boat Mosaic. In The Excavations of an Ancient Boat from the Sea of Galilee (Lake Kinneret). Edited by Shelley Wachsmann. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, pp. 115–18. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, Michael Allen. 2012. A Categorisation and Examination of Egyptian Ships and Boats from the Rise of the Old to the End of the Middle Kingdoms. BAR International Series 2358; Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Strasser, Thomas F., Eleni Panagopoulou, Curtis N. Runnels, Priscilla M. Murray, Nicholas Thompson, Panayiotis Karkanas, Floyd W. McCoy, and Karl W. Wegmann. 2010. Stone Age Seafaring in the Mediterranean: Evidence from the Plakias Region for Lower Paleolithic and Mesolithic Habitation of Crete. Hesperia 79: 145–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talgam, Rina. 2014. Mosaics of Faith: Floors of Pagans, Jews, Samaritans, Christians, and Muslims in the Holy Land. Jerusalem: Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Torczyner, Harry. 1979. Magritte: The True Art of Painting. New York: Abradale Press and Harry N. Abrams, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Thurneyssen, Jacques. 1979. Artists Mistakes. A Reply. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 8: 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trebilco, Peter R. 1991. Jewish Communities in Asia Minor. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky, Amos, and Daniel Kahneman. 1974. Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science 185: 1124–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzalas, Harry. 1990. Kyrenia II in the Fresco of Pedoula Church, Cyprus. A Comparison with Ancient Ship Iconography. In Tropis, Paper presented at the Second International Symposium on Ship Construction in Antiquity, Delphi, Greece, 27–29 August 1990. Edited by Harry Tzalas. Athens: Hellenic Institute for the Preservation of Nautical Tradition, vol. II, pp. 323–27. [Google Scholar]

- Van Effenterre, M. 1978. Cretan Ships on Seal-Stones: Some Observations. In Thera and the Aegean World, Paper presented at the Second International Scientific Congress, Santorini, Greece, August. Edited by Christos Doumas. London: Thera and the Aegean World, vol. I, pp. 593–97. [Google Scholar]

- Vinson, Steve M. 1993. The Earliest Representations of Brailed Sails. Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 30: 133–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Bissing, Friedrich Wilhelm. 1913. Die Kultur des alten Ägyptens. Leipzig: Quelle & Meyer. [Google Scholar]

- Wachsmann, Shelley. 1980. The Thera Waterborne Procession Reconsidered. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 9: 287–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachsmann, Shelley. 1981. The Ships of the Sea Peoples. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 10: 187–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachsmann, Shelley. 1982. The Ships of the Sea Peoples (IJNA 10.3: 187–220): Additional Notes. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 11: 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachsmann, Shelley. 1986. Is Cyprus Ancient Alashiya? New Evidence from an Egyptian Tablet. Biblical Archaeologist 49: 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachsmann, Shelley. 1987. Aegeans in the Theban Tombs. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 20. Leuven: Uitgeverij Peters. [Google Scholar]

- Wachsmann, Shelley, ed. 1990. The Excavations of an Ancient Boat from the Sea of Galilee (Lake Kinneret). Atiqot 19. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority. [Google Scholar]

- Wachsmann, Shelley. 1995. Paddled and Oared Ships Before the Iron Age. In The Age of the Galley: Mediterranean Oared Vessels since Pre-Classical Times. Conway’s History of the Ship. Edited by Robert Gardiner and John Morrison. London: Naval Institute Press, pp. 10–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wachsmann, Shelley. 1996. Bird-Head Devices on Mediterranean Ships. In Tropis, Paper presented at the Fourth International Symposium on Ship Construction in Antiquity, Athens, Greece, August 28–31. Edited by Harry Tzalas. Athens: Hellenic Institute for the Preservation of Nautical Tradition, vol. IV, pp. 539–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wachsmann, Shelley. 1998. Seagoing Ships and Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant. College Station and London: Texas A&M University Press and Chatham Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wachsmann, Shelley. 2002a. The Moulid of Abu el Haggag: A Contemporary Boat Festival in Egypt. In Tropis, Paper presented at the 7th International Symposium on Ship Construction in Antiquity, Lamia, Greece, August 28–30. Edited by Harry Tzalas. Athens: Hellenic Institute for the Preservation of Ship Construction in Antiquity, vol. VII: II, pp. 821–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wachsmann, Shelley. 2002b. Sailing into Egypt’s Past: Does a Celebration of Luxor’s Patron Saint Echo Ancient Pharaonic Traditions? Archaeology 55: 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wachsmann, Shelley. 2007–2008. Deep Submergence Archaeology: The Final Frontier. Skyllis (Deutsche Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Unterwasserarchäeologie e.V.) 8: 130–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wachsmann, Shelley. 2009. The Sea of Galilee Boat, 3rd ed. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wachsmann, Shelley. 2011a. Deep-Submergence Archaeology. In The Oxford Handbook of Maritime Archaeology. Edited by Alexis Catsambis, Ben Ford and Donny L. Hamilton. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 202–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wachsmann, Shelley. 2011b. Which Way Forward? On the Directionality of Minoan/Cycladic Ships. Skyllis (Deutsche Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Unterwasserarchäeologie e.V.) 11: 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wachsmann, Shelley. 2012. Panathenaic Ships: The Iconographic Evidence. Hesperia 81: 237–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachsmann, Shelley. 2013. The Gurob Ship-Cart Model and Its Mediterranean Context. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wachsmann, Shelley. 2015. Understanding the Boat from the Time of Jesus: Galilean Seafaring. Jerusalem: Carta. [Google Scholar]

- Wachsmann, Shelley. In preparation. A Ship Depicted on a Funerary Urn from Hama, Syria, Reconsidered.

- Wedde, Michael. 1999. War at Sea: The Mycenaean and Iron Age Oared Galley. In Polemos: Le contexte guerrier en Égée à l’Age du Bronze, Paper presented at the Actes de la 7e Recontre Égéene Internationale, Université de Liège, Liège, Belgium, Avril 14–17. Edited by Robert Laffineur. Liège: Univerité de Liège and the University of Texas at Austin, vol. II, pp. 465–76, pls. LXXVII–XCII. [Google Scholar]

- Wedde, Michael. 2000. Towards a Hermeneutics of Aegean Bronze Age Ship Imagery. Mannheim and Möhnesee: Bibliopolis. [Google Scholar]

- Wedde, Michael. 2002. Birdshead Revisited: The Bow Morphology of the Early Greek Galley. In Tropis, Paper presented at the 7th International Symposium on Ship Construction in Antiquity, Lamia, Greece, August 28–30. Edited by Harry Tzalas. Athens: Hellenic Institute for the Preservation of Ship Construction in Antiquity, vol. VII: II, pp. 837–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wente, Edward Frank, Jr. 2003. The Report of Wenamun. In The Literature of Ancient Egypt: An Anthology of Stories, Instructions, and Poetry. Edited by William Kelley Simpson. Third Edition. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 116–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wessel, C. J. 1969. The Information Background in the Field of Biological Deterioration of Nonmetallic Materials. In Materials Performance and the Deep Sea, Paper presented at the Seventy-first Annual Meeting, American Society for Testing and Materials, San Francisco, CA, USA, June 23–29. ASTM Special Technical Publication 445. Philadelphia: American Society for Testing and Materials, pp. 131–41. [Google Scholar]

- Whitewright, Julian. 2018. Sailing and Sailing Rigs in the Ancient Mediterranean: Implications of Continuity, Variation and Change in Propulsion Technology. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 47: 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wreszinski, Walter. 1988. Atlas zur Altaegyptischen Kulturgeschichte. Genève: Slatkine Reprints, vol. II. [Google Scholar]

- Yasur-Landau, Asaf. 2010. On Birds and Dragons: A Note on the Sea Peoples and Mycenaean Ships. In Pax Hethitica: Studies on the Hittites and Their Neighbours in Honor of Itamar Singer. Edited by Yoram Cohen, Amir Gilan and Jared L. Millers. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 399–410. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | On the early days of nautical archaeology, see (Bass 1976). For relevant nautical vocabulary, see below, Appendix A: Glossary of Nautical Terms. |

| 2 | One hopes that the recent discovery of a cargo of what appear to be pillow-shaped copper (oxhide?) ingots in the region of Kumluca, Turkey, might indicate a Minoan shipwreck with surviving hull remains (Öniz 2019). |

| 3 | I use the term ‘Syro-Canaanite’ here to denote the cultural entities that inhabited the shores of the eastern Mediterranean, from the Bay of Iskenderun in the north to the shores of Sinai in the south during the Middle and Late Bronze Ages (circa 2000–1200 BC). Syro-Canaanite remains preferable to the term ‘Canaanite’ as at Ugarit, located in modern-day northern Syria, Canaanites were regarded as foreigners and more suitable than the term ‘Phoenician’, for although this culture derived from the Canaanites, it evolved its own material culture, which differed from its Bronze Age antecedents (Rainey 1963, 1996; Mazar 1990, pp. 355–57; Mazar 1992, pp. 296–97). On the borders of Canaan proper, see (Rainey 1996; Rainey and Notley 2006, pp. 34–36). |

| 4 | On ships’ eyes (Gk. opthalmoi; Lat. oculi), see (Hornell 1938a, 1970, pp. 285–89; Casson 1995, pp. 64, 212 no. 49, figures 119, 65–68, 72, 81, 91, 107, 115, 119–122, 125–126, 145, 191–192; Nowak 1999, 2001, 2006, and there additional references). |

| 5 | See below, Section 11. To Be or not to Be. |

| 6 | On the ship of Nebamun, see (Wachsmann 1998, pp. 45–47, and there additional bibliography). Samuel Mark (2017) identifies the Nebamun ship as Egyptian rather than Syro-Canaanite, but this vessel remains irrevocably coupled to the scene in the register above it showing Nebamun, a physician, administering to a Syro-Canaanite personage, presumably the ship’s owner (Figure 9a). This connection is so obvious that even Torgny Säve-Söderbergh (1946, p. 56), perhaps the most forceful advocate for the preeminence of Egyptian shipping, concedes the vessel’s Syro-Canaanite identity. As J.J. Shirley (2007, p. 384) notes in her restudy of Nebamun’s tomb “…the idea that the Syrian’s presence would have no bearing on the remainder of the scene contradicts ancient Egyptian artistic principles generally and the conventions of tomb depictions in particular…. Indeed, I am unaware of any New Kingdom tomb where a scene that is clearly the main component of a wall’s decoration would have elements completely unrelated to each other.” |

| 7 | For a good example of an exquisitely bad example in collecting evidence, see my own experience with the Gurob ship-cart model (Wachsmann 2013, pp. xvii–xviii). |

| 8 | In his review of my book on the Gurob ship-cart model (2013) Christoph Bachhuber (2013, p. 29) disparages my “repeated invocation of ‘Occam’s Razor’”, which in his opinion “may work for aspects of ancient ship design” but “does not work for issues related to ethnicity and identity”. In my view, Bachhuber here does not give sufficient consideration to bias, which is certainly not limited to issues of hull construction. |

| 9 | On changes to the relative sizes of various elements in nautical scenes, see below, Section 10. Size Does Matter. |

| 10 | See below, Section 8. Cultural Continua, figure 29. On Minoan/Cycladic stern castles (ikria), see (Marinatos 1974, pp. 49, pls. 100, 108, 11s, color pls. 4, 9; Van Effenterre 1978; Shaw 1982; Doumas 1983, p. 32, color pl. XI; 1992, pp. 60–70 figures 35, 71–74 figure 36, 75–77 figure 37, 80 figure 39, 81 figure 40, 86 figures 49–50, 87 figure 51, 88 figure 52, 89 figures 53–54, 90 figure 55, 91 figure 56, 92 figure 57, 93 figure 58, 94 figures 59–60, 95 figures 61–62; Wachsmann 1998, pp. 93 figure 6.14–15, 94, 99, 111 figure 6.48). |

| 11 | On evidence linking the Gurob model to Dionysian cult, which apparently arrived in Egypt during the period of Sea People migrations, see (Wachsmann 2013, pp. 41–57, 59, 120–32, 203–4). |

| 12 | Similarly, but much farther afield, Kristian Kristiansen (2019) proposes that elements of Scandinavian rock art depict models. |

| 13 | I intend to correct this error in an upcoming publication (Wachsmann in preparation). |

| 14 | See below, Section 9. Corpus Delecti. |

| 15 | On determining the directionality of Early Cycladic long ships, see below, Section 8. Cultural Continua. |

| 16 | Earlier Lucien Basch (1975, pp. 201, 202 figure 2) had identified the left end as the bow. |

| 17 | Herodotus (Histories 2.36.4), writing in the fifth-century BC, states that the Egyptians alone had the curious habit of running their brails on the ‘inside’, that is the after side, of their sails (Basch 1978, pp. 115, 116 figure 28–29, 118; Casson 1995, p. 234 no. 42; Vinson 1993, p. 135 no. 11). |

| 18 | See also figures below, in Section 8. Cultural Continua. |

| 19 | See above, Section 2. Shaving with Occam’s Razor. |

| 20 | Often these ships depict bird heads with upturned beaks, a feature unparalleled in birds appearing in Aegean or Philistine art (Figure 21b). The upturned beak may represent a central European Urnfield influence (Wachsmann 1998, p. 180 figure 30: A). |

| 21 | For additional examples of this ship type, see below and Section 10. Size Does Matter. |

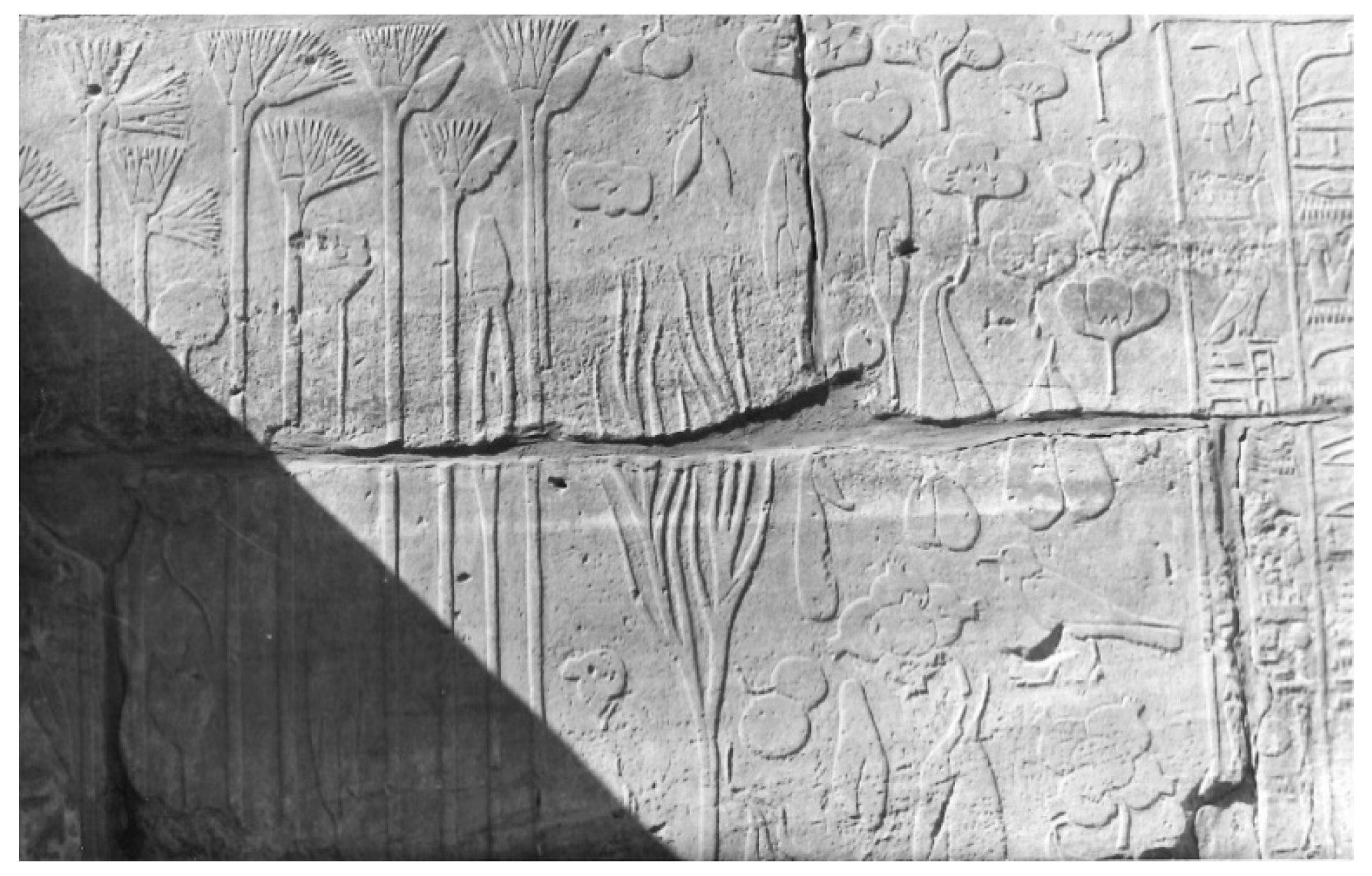

| 22 | On Thutmose III’s Botanical Garden at Karnak, see also below, Section 11. To Be or Not to Be. |

| 23 | Lionel Casson (1995, p. 51, figures 67–69) had previously used the same method to interpret the construction of Geometric-period galleys. |

| 24 | See also below, Section 10. Size Does Matter. |

| 25 | See above, Section 6. On Ship Typologies. |

| 26 | Dates for the Bronze Age in the eastern Mediterranean vary by region. Here I employ the accepted Aegean chronology (Manning 2010, p. 23 table 2: 2). Sometimes we must concede that certain questions will remain unresolvable with the evidence at hand. For example, in Figure 42a did the artist invert the galley in the larnax in order to signify that the bones interred in it were the result of a shipwreck, because the artist painted when bending over the larnax or for some other unknown reason? |

| 27 | On the three-dimensional evidence for stanchions on the Gurob ship-cart model, see (Wachsmann 2013, pp. 13–16). |

| 28 | On the tomb of Iniwia (also written Nia or Iniuia), see also (Porter and Moss 1981, p. 707; Martin 1991, p. 200; Schneider 1993). |

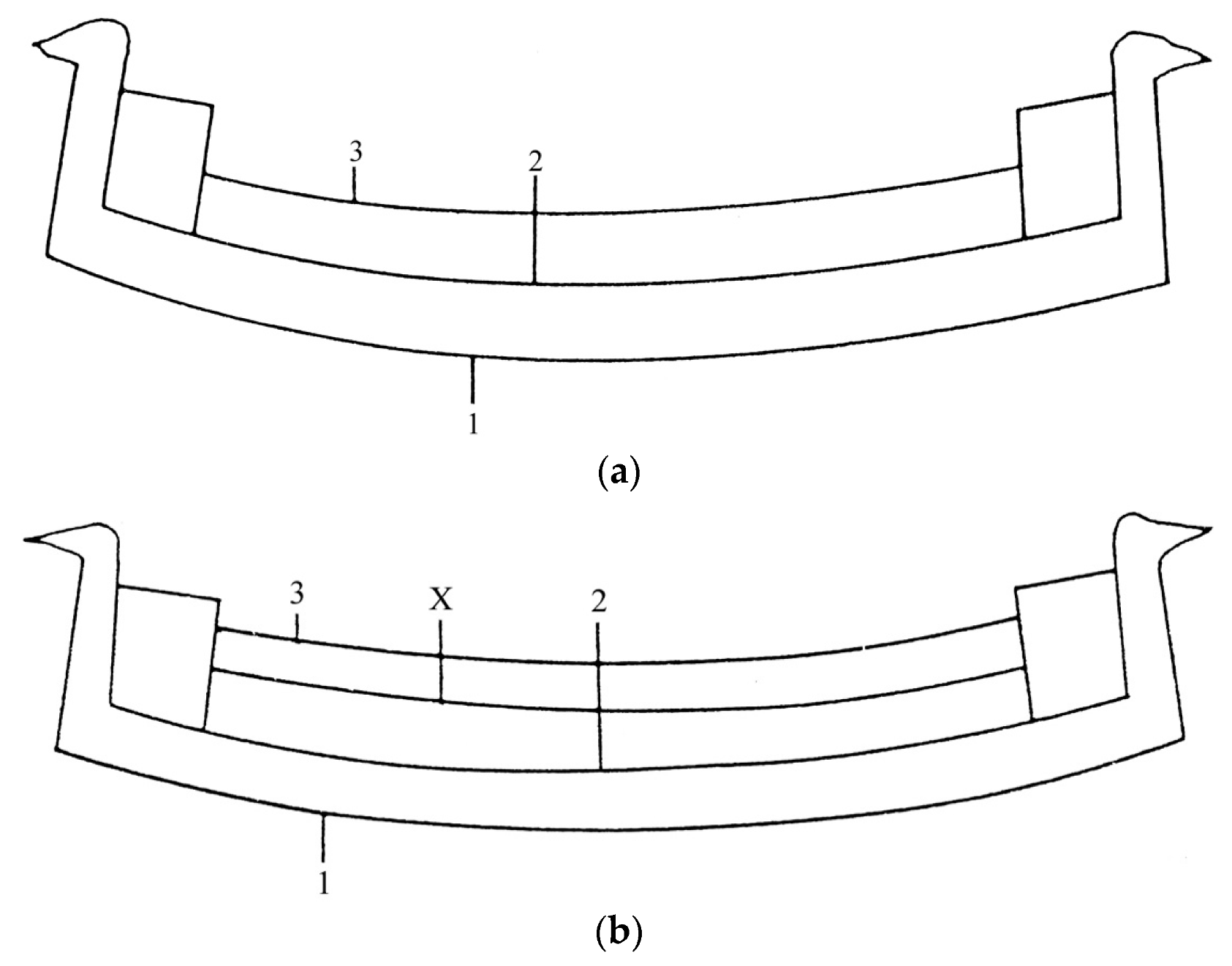

| 29 | On hogging trusses and the question of keels on Egyptian seagoing ships, see (Hocker 1998a; Wachsmann 1998, pp. 14–15, 18, 24–26, 45, 56, 74, 228 figure 10.9, 242, 248–250, 367 no. 15, 346 no. 55, and there additional bibliography). |

| 30 | On changes of clothing in Egyptian wall paintings, see (Pritchard 1951; Wachsmann 1987, pp. 44–48, and there additional references). |

| 31 | Although badly damaged, a third Deluge scene mosaic in the late-fifth century AD synagogue at Jerash, Jordan, may never have had an ark represented in it, rather focusing on the covenant the Lord made with Noah after the flood (Genesis 8:20–22, 9:1–17; Biebel 1938, pp. 319–22, pls. LXIII–LXIV; Talgam 2014, pp. 319, 320 figures 394–395, 321 figures 396–397). On the possible use of pattern books in creating Byzantine-period mosaics, see (Dauphin 1978). |

| 32 | While not obvious on the coin in Figure 55, better preserved coins from this series show the bird with a raven’s beak (Spier 2007a, catal. 171, figure 1: B). |

| 33 | On the information to be gleaned on hull construction techniques from the cognate story of Utnapishtim, the Mesopotamian flood survivor from the Epic of Gilgamesh, see (Pedersen 2003; 2005). |

| 34 | Noah’s Ark: Genesis 6: 14–16, 18. The Ark of the Covenant: Exodus 25: 10, 13–15, 16, 21–22, 26: 33–34, 30: 6, 26, 31: 7, 35: 12, 37: 1, 5, 39: 35, 40: 3, 5, 20–21; Leviticus 16: 2; Numbers 3: 31, 4: 5, 8: 89, 10: 33, 35, 14: 44; Deuteronomy 10: 8, 31: 9, 25, 26; Joshua 3: 3–4, 6, 8, 11, 13–15, 17, 4: 7, 9–11, 16, 18, 6: 4, 6–9, 11–13, 7: 6, 9: 33; Judges 20: 27; I Samuel 3: 3, 4: 3–6, 11, 13, 17–19, 21, 5: 1–4, 7–8, 10–12, 6: 1–3, 8, 11, 13, 15, 18–21; 7: 1–2, 14: 18; II Samuel 6: 2–4, 6–7, 9, 10–13, 15–17, 7: 2, 11: 11, 15: 24–25, 15: 25, 29; I Kings 2: 26, 3: 15, 6: 19, 8: 1, 3, 5–7, 9, 21; I Chronicles 6: 31; 13: 3, 5–7, 9–10, 13–14, 15: 1–3, 12, 14–15, 23–29, 16: 1, 4, 6, 37, 17: 1, 22: 19, 28: 2, 18; II Chronicles 1: 4, 5: 2, 4–10, 6: 41, 8: 11, 35: 3; Psalms 132: 8; Jeremiah 3: 16. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wachsmann, S. On the Interpretation of Watercraft in Ancient Art. Arts 2019, 8, 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040165

Wachsmann S. On the Interpretation of Watercraft in Ancient Art. Arts. 2019; 8(4):165. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040165

Chicago/Turabian StyleWachsmann, Shelley. 2019. "On the Interpretation of Watercraft in Ancient Art" Arts 8, no. 4: 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040165

APA StyleWachsmann, S. (2019). On the Interpretation of Watercraft in Ancient Art. Arts, 8(4), 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040165