Perceptions. The Unbuilt Synagogue in Buda through Controversial Architectural Tenders (1912–1914)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Background of the Buda Synagogue Architectural Tender—Aims and Perspectives

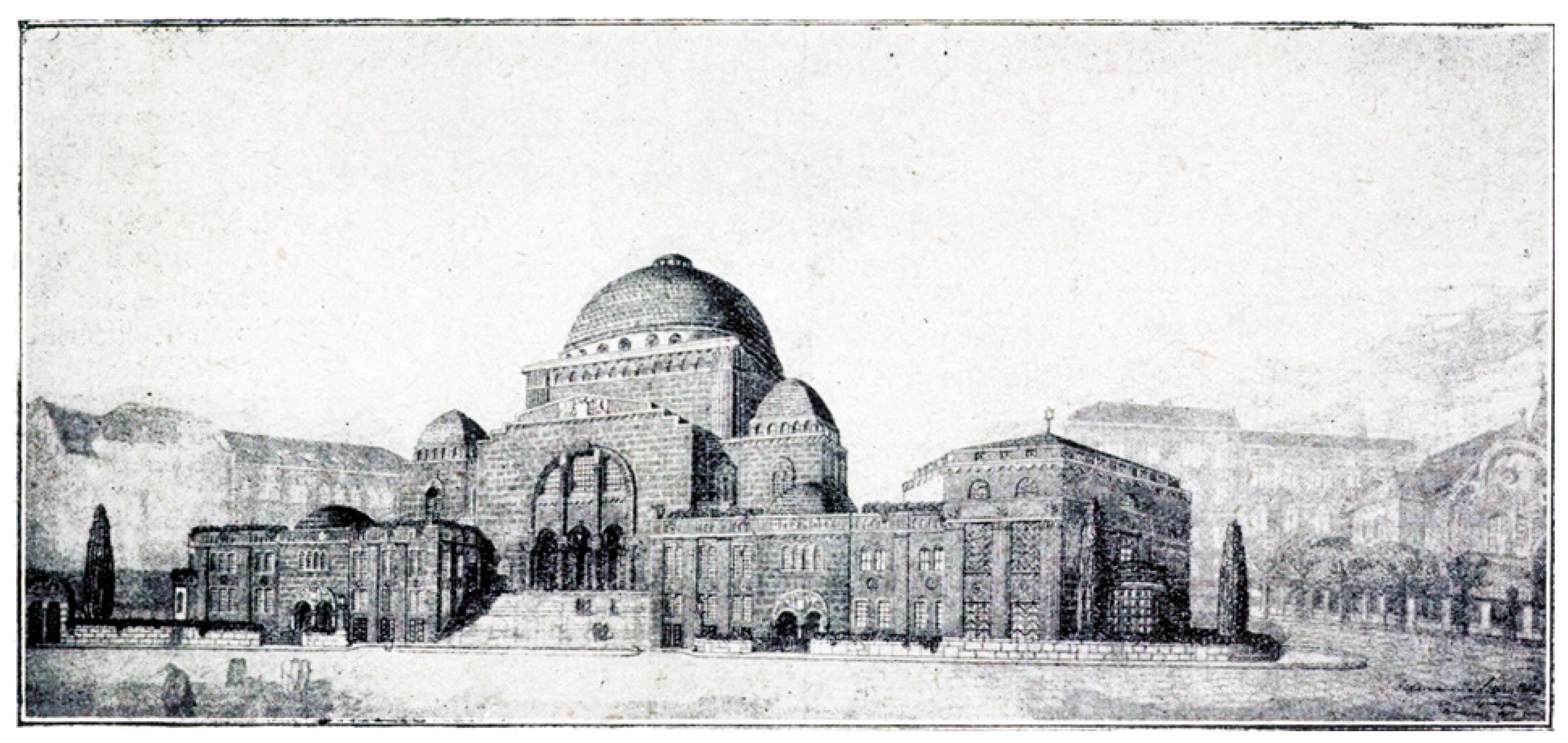

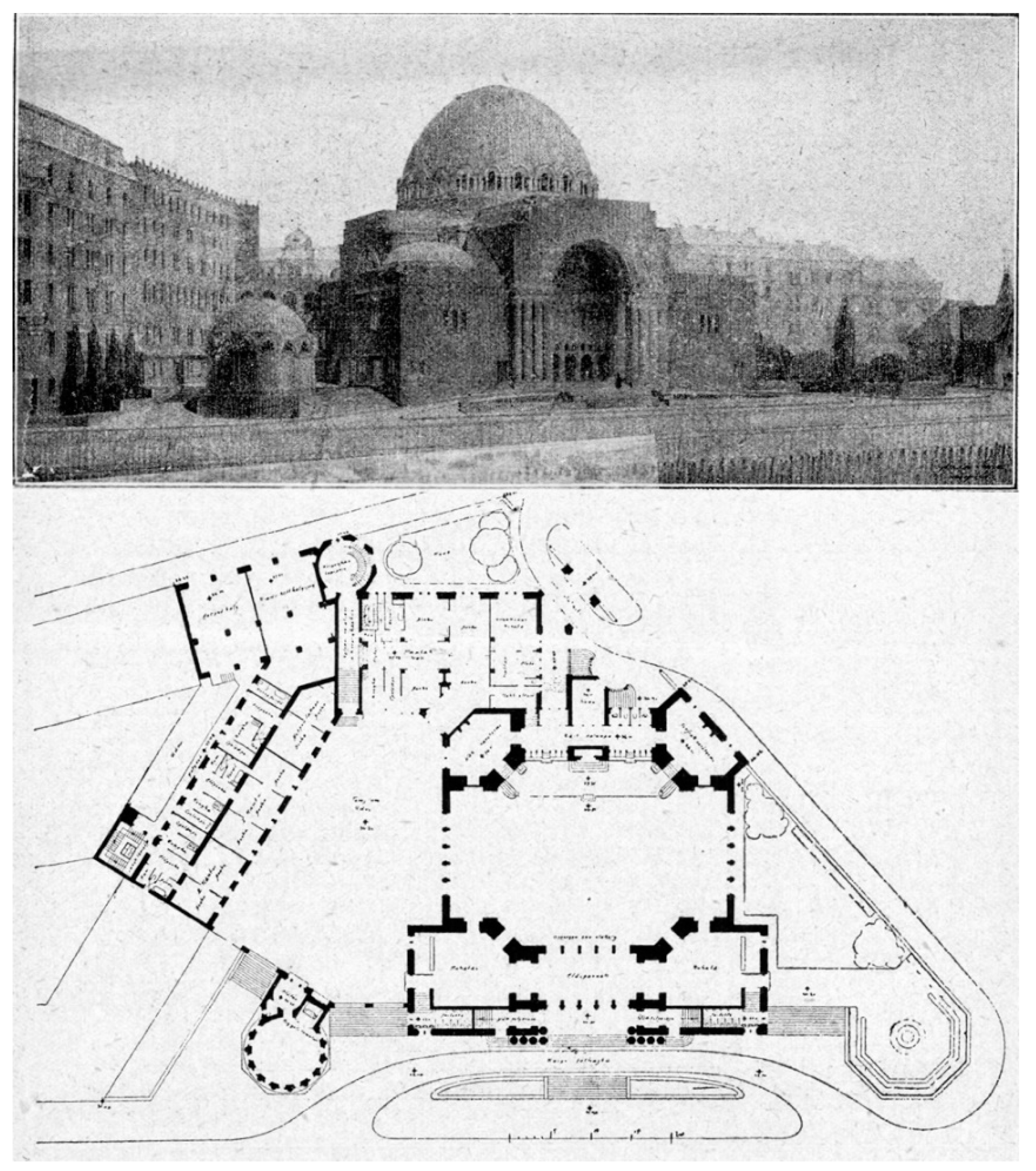

2.2. Architectural Competition in 1912: The Controversial Decision

Arthur Elek (pseudonym: e. a.): “The round, flat dome rises above the square of the temple. The tender protocol describes this architecture as »being abstract«. According to our view it is perfectly right because you really feel that it is not in its future material that its designer imagined it, but rather on the paper.”29 According to Rudolf Klein’s analysis: “The plan of the Buda Synagogue proves that it was prescient for Lajta to see the correspondence between modernism and the Judaic tradition: the rejection of ornamentation (pagan sacrifice), the abstraction (inconceivable God), the white and contentless walls (the primacy/freedom of ideas in the visually delimited concrete representations), the importance of the time factor (life as a time-warping phenomenon waiting for the Messiah), and the space-time of modern architecture, derived from Maimonides’ philosophy and Jewish mysticism through Einstein and Minkowski’s theories.”

2.3. Architectural Competition in 1913: Rumors

2.4. Architectural Competition in 1914: The Second Scandal

2.5. Architectural Competition in 1914: The Fundamental Idea

3. Conclusions: Wider Context of the Buda Synagogue

4. Materials and Methods

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FKT. 1928. Fővárosi Közmunkák Tanácsának Hivatalos Jelentése [1923–1927]. Budapest: Hellas Irodalmi és Nyomdai Részvénytársaság. [Google Scholar]

- Kann, Robert A. 1977. A History of the Habsburg Empire, 1526–1918. Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Rudolf. 2013. Lajta építészete és a zsidó szellem. In Az Építészet Mesterei—Lajta Béla, 1st ed. Edited by János Gerle. Budapest: Holnap kiadó, pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Rudolf. 2017. Zsinagógák Magyarországon 1782–1918. Budapest: Terc. [Google Scholar]

- Lajta Archive. 2010. A Budai Zsinagóga Pályaterve, 1912. (I. díj). Available online: http://lajtaarchiv.hu/muvek/a-budai-zsinagoga-palyaterve-1912-xii-krisztina-korut-moszkva-ter/ (accessed on 11 August 2019).

- Moravánszky, Ákos. 1998. Competing Visions: Aesthetic Invention and Social Imagination in Central European Architecture, 1867–1918. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sisa, József. 1982. A Rumbach utcai zsinagóga, Otto Wagner ifjúkori alkotása. Ars Hungarica 1: 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Újvári, Péter, ed. 1929. Magyar Zsidó Lexikon. p. 149. Available online: http://www.elib.hu/04000/04093/html/ (accessed on 12 September 2019).

| 1 | The Eclectic-Art Nouveau building became a focus of interest in 2018 when it was bought by the National Bank of Hungary and its renovation and conversion was launched. |

| 2 | Gyula Sándy (Prešov, 1868–Budapest, 1953), architect and university lecturer. In addition to renovating monuments, he designed buildings including numerous Lutheran churches in Budapest and Pest county (e.g., the Reformed Church in Nagykőrös), schools and community institutions, like the postal palaces in Budapest and Zagreb. |

| 3 | Béla Lajta (Leitersdorfer until 1907) (Óbuda, 1873–Vienna, 1920), architect. His early works were greatly influenced by Ödön Lechner. After 1905 he moved away from the characteristic Lechner style. The buildings, designed after 1909, are identified by simple, geometrical and monumental forms, but never gave up the use of ornamentation—most of their ornamental motifs of folk art emphasize structural or functional elements. His work can be divided into four eras: Floral Art Nouveau, Arts and Crafts, Art Deco, Geometric Art Nouveau or Early Modern. He created significant buildings in each of these eras. |

| 4 | On 17 June 1746, Maria Theresa banned all Jews from Buda, September 8 was the deadline for emigration. The city still collected the tax for 1746, and the Jews left the city before the deadline. Some of the exiles settled in Old Buda, others scattered throughout the country and the rest migrated to Poland (Újvári 1929, p. 146). In 1783 Joseph II. proclaimed the “Systematica gentis judaicae regulatio”, the law of free movement, which nevertheless restrcited Jews from settling in mining towns (Újvári 1929, p. 212). |

| 5 | Architect Marcell Komor (Pest, 1868–Deutschkreutz, 1944) and architect Dezső Jakab (Vadu Crișului, 1864–Budapest, 1932) are two great figures of the national Art Nouveau movement (Hungarian Sezession) initiated by Ödön Lechner. They started working together in 1897 and opened their office in 1899. Their cooperation lasted until 1918. Their urban planning assignments included the creation of a new city centre in Târgu Mureș, and the Palace of Culture which was one of the most conceptual creations of the era. Additionally, several public buildings were designed for Subotica (Synagogue, 1902; City Hall, 1908–1910; Bank, 1907; savings bank, 1908; buildings in Palić, 1909–1912), as well as the Erkel Theater (1912–1913) and Palace Hotel (1910–1911) in Budapest; city hall and a music palace (1906) in Bratislava (etc.). |

| 6 | Ödön Lechner (Pest, 1845–Budapest, 1914) was the father of the Hungarian Secession movement (Hungary’s brand of art nouveau). He aimed to create a distinct National Style blending art nouveau with Hungarian folk motifs and Oriental elements. As a creator of the independent Hungarian style of architectural identity, he had many followers, including Béla Lajta, Lipot Baumhorn, Dezső Jakab and Marcell Komor. Lechner’s most famous buildings are the Museum of Applied Arts (1896), the Geologiacal Institute Building (1899) and the Hungarian State Treasury (1901) in Budapest. |

| 7 | Béla Löffler (Budapest, 1880–?) and Sándor Löffler (Samu) (Budapest, 1877–?), architect brothers that worked at the turn of the century and during the Early Modernist period. In 1906 they opened an independent office. Several tenement buildings in Budapest were designed following the principles and detailed practice of the Lajta Office (Magda Court, 1911–1912; Burger house, 1908). Their most significant work is the Kazinczy Street Synagogue (1912), along with the school and the community building. Between 1897 and 1899 Béla worked in the office of Frigyes Spiegel, and later at Béla Lajta’s. His design that was submitted to an international competition for the synagogue in Antwerp in 1923 was successful. In 1925, his design won the competition for the National Theater in Jerusalem. He later had a design office in Alexandria. Sándor was primarily responsible for management and office administration during the time of their cooperation. After the war, he independently designed apartment buildings in Budapest. |

| 8 | Franz Roeckle (1879–1953), a Lichteinstein-based architect who won the competition for the design of the Westend synagogue. In 1932, he joined the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, however, in 1924 he was in charge of the building of the Institute of Social Research. |

| 9 | Ezrey [Komor, Marcell]: “Zsidó templom Budán.” Vállalkozók Lapja, 7 January 1914, p. x. |

| 10 | Pesti Napló, 27 September 1907, p. 13. |

| 11 | In the citation referred to as FKT, according to the original name, Fővárosi Közmunkák Tanácsa in Hungarian. |

| 12 | Historical unit for measure—quadratklafter (Ger.), orgia quadrata (Lat.) |

| 13 | “Tervpályázat új főtemplomunk építésére.” A Budai Izraelita Hitközség Értesítője, 1912, pp. 13–16. |

| 14 | Lipót Baumhorn (Kisbér, 1860–Kisbér, 1932), architect. He is undoubtedly the most renown individual in Hungarian synagogue architecture. His most creative decades of work involved the design and construction of synagogues, however his work was not limited to the design of synagogues. His designs for savings banks, schools, residential buildings and palaces are also of great importance. In his buildings, the signs and aspirations of the late Eclectic and Art Nouveau styles can be observed at the same time. |

| 15 | The architect was only involved in the first competition, thus we are aware of the 1912 contest. |

| 16 | The denominations of Art Nouveau came from the Secession, the modern art group in Vienna to Habsburg Central Europe (szecesszió in Hungarian), although the artists (and people in general) attempted to withstand the influence of Vienna, as the fear of cultural Germanization was present (Kann 1977, pp. 552–53). The regional impact in general and in art and architecture (due to Otto Wagner, Joseph Maria Olbrich and Adolf Loos) was significant, further because Vienna has been recognised as a centre of Art Nouveau besides Brussels, Barcelona, Munich and Paris since the start. In the fin-de-siècle art history, both the local versions and the general phenomenon in the Habsburg Central Europe are apt to interpretation in the context of the achievements of Viennese architects (Moravánszky 1998, p. 151). |

| 17 | “Tervpályázat új főtemplomunk építésére.” A Budai Izraelita Hitközség Értesítője, 1912, p. 14. |

| 18 | Manó Pollák (Sučany, 1854–Budapest, 1937): architect. He designed buildings in the Art Nouveau style. |

| 19 | Julian Wagner (?–?), Austrian origin master builder. |

| 20 | “Tervpályázat új főtemplomunk építésére.” A Budai Izraelita Hitközség Értesítője, 1912, p. 16. |

| 21 | “A budai izraelita templom tervpályázata.” Tervpályázatok. Magyar Építőművészet, 1912, p. 17. |

| 22 | Izidor (Imre) Scheer, from 1907 Gondos (1860–Eger, 1930), architect and master builder. In 1892 he opened his office, designed tenement houses, business centres and a factory. He took part in important architectural competitions: in 1898 with László Vágó and József Vágó in the competition of the Synagogue in Lipótváros, and in 1928 he was one of the few Hungarian architects to take part in the international competition for the Palace of Nations (Geneva). |

| 23 | Dávid Jónás (Pest, 1871–Budapest, 1951), architect. He worked in Atelier Felmer and Helmer, then returned to Budapest in 1900. For a long time he worked with his brother Zsigmond Jónás building villas and apartment houses, and later became the architect of the Hungarian State Railways. |

| 24 | Zsigmond Jónás (Budapest, 1879–Budapest, 1936), architect. In 1906 he was awarded the gold medal of the Hungarian Society of Engineers and Architects. For a long time he worked with his brother Dávid Jónás. Their jointly designed buildings includde the Szénássy and Bárczay department stores, the Palace of Tolnai’s World Journal, and the Goldberger warehouse. |

| 25 | Ármin Leindörfer (Leimdörfer) (?–?), architect from Budapest. |

| 26 | Vilmos Magyar (?–?), architect and architectural writer. |

| 27 | Magyar, Vilmos. “A budai zsinagóga pályázata.” Építő Ipar, 14 July 1912, p. 272. |

| 28 | Lengyel, Géza (pseudonym: -et.). “A budai új zsidótemplom. Tervkiállítás a MÉSZ-ben.” Pesti Napló, 4 July 1912, p. 13. |

| 29 | Elek, Artúr (pseudonym: e. a.). “a budai új zsinagóga pályatervei.” Az Ujsag, 4 July 1912. |

| 30 | Lengyel, Géza (pseudonym: -et.). “A budai új zsidótemplom. Tervkiállítás a MÉSZ-ben.” Pesti Napló, 4 July 1912, p. 13. |

| 31 | Elek, Artúr (pseudonym: e. a.). “a budai új zsinagóga pályatervei.” Az Ujsag, 4 July 1912. |

| 32 | Magyar, Vilmos. “A budai zsinagóga pályázata.” Építő Ipar, 14 July 1912, p. 272. |

| 33 | Elek, Artúr (pseudonym: e. a.). “a budai új zsinagóga pályatervei.” Az Ujsag, 4 July 1912. |

| 34 | Budapesti Hírlap, 18 January 1913, p. 17. |

| 35 | Fővárosi Közlöny, 12 August 1910, p. 1435. |

| 36 | Budapesti Hirlap, 2 July 1913, p. 14. |

| 37 | Az Ujság, 18 July 1913, p. 15. |

| 38 | József Porgesz (Öcsöd, 1880–1944, in a concentration camp in Germany), architect. Together with Sándor Skutetzky won the Kazincy Street Synagogue architectural tender. Although their work was the best among the competitors, the Pest Autonomous Orthodox Jewish Community chose to build the design of the Löffler brothers. |

| 39 | Pesti Napló, 27 July 1913 and 29 July 1913, p. 15. |

| 40 | Magyar, Vilmos: “A budai zsidó templom második tervpályázata.” Épitő Ipar, 3 August 1913, p. 339. |

| 41 | Magyar, Vilmos: “A budai zsidó templom második tervpályázata.” Épitő Ipar, 15 July 1913, p. 330. |

| 42 | Pesti Napló, 18 December 1913, p. 19. |

| 43 | “A megsértett magyar építőművészet.” Világ, 3 January 1914, p. 12. |

| 44 | Pesti Napló, 3 January 1914, p. 17. |

| 45 | Budapesti Hírlap, 16 January 1914, p. 15. |

| 46 | Ezrey [Komor, Marcell]: “Zsidó templom Budán.” Vállalkozók Lapja, 7 January 1914, p. x. |

| 47 | Világ, 14 March 1914, p. 12. |

| 48 | Budapesti Hírlap, 14 March 1914, p. 17. Pesti Napló, 14 March 1914, p. 18. Magyarország, 15 March 1914, p. 18. |

| 49 | S.M. (pseudonym): “A budai zsidótemplom tervpályázata.” Építő Ipar–Építő Művészet, 22 March 1914, p. 119. |

| 50 | Magyar, Vilmos: “A budai zsidó templom juryje.” Építő Ipar–Építő Művészet, 22 March 1914, p. 121. |

| 51 | S.M. (pseudonym): “A budai zsidótemplom tervpályázata.” Építő Ipar–Építő Művészet, 22 March 1914, p. 119. |

| 52 | Ibid. |

| 53 | Magyar, Vilmos: “Marsnak szekerén.” Épitő Ipar–Építő Művészet, 4 October 1914, pp. 365–67. |

| 54 | Fővárosi Közlöny, 12 October 1910, p. 1433. |

| 55 | Ibid. |

| 56 | Budapesti Közlöny, 14 May 1936, p. 2. |

| 57 | Világ, 8 July 1913, p. 17. |

| 58 | The Hungarian government terminated its union with Austria on 31 October 1918, officially dissolving the Austro–Hungarian state. The Trianon Treaty was the peace treaty between defeated Hungary (as one of the successor states of the Austro–Hungarian Empire) and the victorious Entente Powers which ended World War I. The treaty, and the accompanying dissolution of the Austro–Hungarian Empire, defined Hungary’s new borders, and created many small multinational states in place of the empire. |

| 59 | The aim of the law was to restrict the number of Jews to 6% of the universities’ population, which was their proportion in Hungary at that time. |

| 60 | “Az új budai zsinagóga felavatása.” Pesti Napló, 15 September 1936, p. 13. |

| 61 | “Az új lágymányosi templom.” Tér és Forma, 1936, vol. 12, pp. 353–56. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lovra, É. Perceptions. The Unbuilt Synagogue in Buda through Controversial Architectural Tenders (1912–1914). Arts 2019, 8, 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040149

Lovra É. Perceptions. The Unbuilt Synagogue in Buda through Controversial Architectural Tenders (1912–1914). Arts. 2019; 8(4):149. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040149

Chicago/Turabian StyleLovra, Éva. 2019. "Perceptions. The Unbuilt Synagogue in Buda through Controversial Architectural Tenders (1912–1914)" Arts 8, no. 4: 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040149

APA StyleLovra, É. (2019). Perceptions. The Unbuilt Synagogue in Buda through Controversial Architectural Tenders (1912–1914). Arts, 8(4), 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040149