Abstract

In early 2019, Australia’s Northern Territory (NT) government announced the $106 million funding and promotion of a new state-wide Territory Arts Trail featuring Indigenous art and culture under the banner “The World’s biggest art gallery is the NT.” Some of the destinations on the Arts Trail are Indigenous art centres, each one a nexus of contemporary creativity and cultural revitalisation, community activity and economic endeavour. Many of these art centres are extremely remote and contend with resourcing difficulties and a lack of visitor awareness. Tourists, both independent and organised, make their travelling decisions based upon a range of factors and today, the availability of accessible and engaging online information is vital. This makes the quality of the digital presence of remote art centres, particularly their website content, a critical determinant in visitor itineraries. This digital content also has untapped potential to contribute significant localised depth and texture to broader Indigenous arts education and comprehension. This article examines the context-based website content which supports remote Indigenous art centre tourism and suggests a strategic framework to improve website potential in further advancing commercial activities and Indigenous arts education.

1. Introduction

Several friends recently planning extended driving holidays through Central and Western Australia asked for suggestions and advice, hoping to visit remote Aboriginal art centres en route. They had attempted their own research but had often encountered a puzzling lack of detail and clarity when searching online. Art centres have a digital presence—websites and social media accounts—but the tourists had difficulty grasping the scope of experiences that they might encounter. Given the vast distances and often challenging road conditions in the Central and Western desert regions of Australia, refining the pre-planning for a remote Aboriginal art centre visit was considered essential. These visitors were arguably the ‘ideal’ cultural tourists: curious, culturally aware and well-prepared independent travellers who were actively seeking to broaden their understanding of Aboriginal art and culture—yet they hesitated to make their decisions without more information.

Whether independent or organised, tourists make their travelling decisions based upon a range of factors. Today, the availability of accessible, engaging online information is virtually non-negotiable (Cooper and Hall 2016). This makes the quality of a remote Indigenous art centre’s digital presence—particularly that of its website—a critical determinant in visitor itineraries and one which this article argues should be optimised. This article synthesizes research identifying the most important attributes of remote Indigenous tourism for Australian consumers (Akbar 2016), and perceived barriers to Indigenous tourism, with the development of strategic, information-rich art centre website content. In addition, it is also argued that existing art centre website content often appears to underutilise its capacity to contribute greater depth and texture to broader Indigenous arts education and insight. In light of this, an Indigenous art centre website framework is developed for content which jointly supports informed cultural tourism and localised Indigenous arts education.

Art centre websites have a global reach and art centres themselves have a mandate for the transmission of Indigenous culture into the world beyond their community (Parliament of Australia 2007). These two preconditions allow art centres to take a strategic position as global providers of website content enabling a rich insight into the localised social, cultural and historical contexts of remote contemporary Indigenous art, and as providers of website content which addresses the interests of prospective art centre tourists with tailored information. Fortunately for art centres, there is a great deal of congruence to be found in developing strategic website content which meets the criteria for both.

Section 2 of this article describes the Indigenous art centre model, identifying some of its unique characteristics, constraints and activities, including the potential for diversification through cultural tourism. Section 3 focuses on understanding Indigenous art centre involvement in Australia’s new Northern Territory Arts Trail campaign and highlights existing research into Indigenous tourism uptake. The potential for art centres to make tailored online information available to inform and interest prospective cultural tourists is consequently identified as a particular opportunity. Section 4 proposes that art centres enhance their websites with strategic content to help overcome perceived barriers to remote cultural tourism and to cultivate greater understanding and competencies in tourists. Existing research identifying the most important attributes of remote Indigenous tourism for domestic consumers (Akbar 2016) is utilised as a basis for sharpening and refining content. In Section 5, the additional aim of enhancing art centre websites to support Indigenous arts education is developed using an approach which encourages cross-cultural connections between art and audiences through explanations of social, cultural and historical contexts (Vogel 2013). This context-driven approach is transformed into a strategic art centre website framework for content which also, fortuitously, incorporates many important remote Indigenous tourism attributes (Akbar 2016) as well as being supportive of the sales activities of an art centre.

The overriding objectives of this website framework are twofold: firstly, to provide effective content to inform, interest and potentially influence tourist decision making and, secondly, to position art centre websites as globally accessible platforms for providing rich cross-cultural insight into the localised social, cultural and historical contexts of Indigenous art.

This article is written from a commercial arts administration perspective. However, it is essential that artists and art centres direct and manage any implementation of the art centre website framework within their own self-determined parameters.

2. Australian Indigenous Art Centres: Activities and Constraints

There are over 100 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-owned art centres in Central and Northern Australia.1 As intercultural enterprises which reflect the localised, contemporary lived Indigenous experience in different parts of Australia, many art centres are uniquely positioned to engage with visitors on multiple levels if they so choose. Each one operates within its own self-determined capacities as a primary location in its community for Indigenous art production and distribution (Parliament of Australia 2007), with communities sometimes comprising only several hundred people or fewer. Most remote art centres are located on country, where many Indigenous people prefer to live in intimate connection with the land (Figure 1). Some remote communities are inaccessible by road at certain times of the year and they might experience extreme summer temperatures, yet their art centres fulfil a diverse range of essential community-based mandates and functions year-round: Indigenous cultural maintenance and revitalisation; income generation and professional development for artists; employment and training in the art centre for community members and as unofficial ‘drop-in’ centres offering a point of contact to other services such as legal, health and aged care (Riederer 2018; Parliament of Australia 2007; Altman 2005). Art centres are governed by a board of local Indigenous community members with the day-to-day operations forming the responsibility of an art centre manager who is employed to meet a skills-based need (Jones et al. 2019).

Figure 1.

Ikuntji Artists, Haasts Bluff, NT. Image sourced from Ikuntji Artists website. Available online: https://ikuntji.com.au/about/about/ (accessed on 29 August 2019).

The role of the art centre manager is a pivotal one. In many cases, artists speak multiple Aboriginal languages with English as an additional language (Simpson 2019) and therefore communication must be managed accordingly. Strength in every aspect of successfully operating and growing a small to medium business in an isolated location with limited resources is required (Riederer 2018) and this often necessitates an inventive solutions-based approach. The culturally sensitive ability to build strong community ties, to provide individual and appropriate arts advice and to establish and maintain relationships between staff, artists, art centre directors, institutions and galleries is crucial to the success of the art centre. Pursuing multiple opportunities for exhibiting the artists’ work in institutions, galleries, art fairs and markets is vital and often requires travelling long distances with artists under challenging conditions (Parliament of Australia 2007; Riederer 2018; Altman 2005). Furthermore, an art centre manager may be asked to assist with an artist’s personal affairs, such as helping with paperwork and sourcing services (Wroth 2016). Most art centres operate under considerable staff, funding and location constraints and the development of new projects can be particularly challenging and time-consuming to implement (Altman 2005; Parliament of Australia 2007).

Art centres are expected to work cooperatively with government and service industries under an operational framework defined by the Indigenous Art Centre Plan. A number of business, cultural and strategic objectives are specified in this Plan, including the development and maintenance of an art centre website (Australian Government 2018). An art centre or its member artist is usually supported by a peak body, such as Desart in Alice Springs, which provides access to advocacy, marketing and business support to over forty art centres in Central Australia (1). To remain financially viable, art centres generally rely in part on State and Federal funding and philanthropy to augment their income from the sale of art and merchandise (Congreve and Burgess 2017). Ultimately, Altman (2005) describes art centres as hybrid organisations “…at once cultural and commercial, local and global, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal—fundamentally inter-cultural…”.

Diversifying income streams through cultural tourism is viewed by some art centres as an opportunity to promote additional economic independence and agency for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Indeed, the Indigenous Art Centre Plan advocates for diversification strategies as a particular goal (Australian Government 2018). Cultural tourism is pursued by art centres and communities in varying ways, from drop-in art centre gallery visits to the offering of culturally driven, highly immersive multi-day experiences for visitors (Butler 2017). In addition, some art centres are now actively promoted as particular tourism destinations by Australia’s Northern Territory government through their recently announced Territory Arts Trail initiative.2 The decision to promote an art centre as a visitor destination however, remains in the hands of its board members and the community. On that basis, and for many different reasons, not every art centre is prepared to pursue visitor-based cultural tourism as a diversifying strategy or indeed as a specific means of cross-cultural engagement (Butler 2017).

The term ‘cultural tourism’ tends to be associated with concepts of commodification (Watson et al. 2012; Ryan 2005), and this fuels unresolved debates about what, if anything, constitutes authenticity in the tourist experience (Watson et al. 2012). In putting aside the loaded issue of authenticity, cultural tourism can also be considered through the lens of the ‘tourism moment’ (Crouch 2012). Crouch (2012) describes the potential cognitive disruption and transformation of a tourism moment “as complex, enormously variable but surprisingly situated in one simple thing: the sometimes awkward, sometimes wonderful moments of negotiating who we are, how we feel in being alive” (Crouch 2012, p. 23).

Such a description has some clear parallels with particular ways in which our horizons can be expanded—and yet also intensely focused—when we engage deeply with works of art. The phenomenological framing (Ingram 2005) of embodiment and experience that Watson et al. (2012) also ascribes to the tourism moment has an interesting resonance with the individual process of subjective and sensory meaning-making to be found in the detailed contemplation of art. Andrews (2009) describes the performance of tourism as being “composed of times… moments that pierce that rhythm… and give rise to a heightened state of self and group awareness” (Andrews 2009). It is not surprising then that the fully embodied experience of visiting a remote Indigenous art centre, where the art itself reflects the artists’ local contemporary and cultural contexts, might give rise to a sense of cultural dislocation which ‘pierces the rhythm’ of preconceptions and assumptions. It is both the act of performing art centre tourism (Crouch 2012)—journeying, seeing, hearing, feeling—and the specific contemplation of the art found there that can add richness and depth to any pre-existing understanding and expand an in situ recognition of the significance of country, culture and agency for remote Indigenous communities.

3. Indigenous Cultural Tourism and Australia’s Territory Arts Trail

The Territory Arts Trail is a recently announced and evolving campaign. Australia’s Northern Territory government is investing $106 million to promote the Territory’s diverse Indigenous art and culture for its potential economic, social and cultural benefits. Art centres, festivals, Aboriginal rock art sites, art galleries, art fairs and cultural tours are all included (2). The centrepiece of the Territory Arts Trail is intended to be a National Aboriginal Art Gallery in Alice Springs, the concept and planning for which is under negotiation.3

The Arts Trail is conceived as a regionalised network of Indigenous art and cultural destinations within six NT geographic areas: Darwin and surrounds, Arnhem Land, the Katherine region, Kakadu and surrounds, the Alice Springs area and Uluru and surrounds.4 This is a staged campaign with existing visitor-ready arts and cultural experiences and sites already included on the Arts Trail with more to be added as other destinations meet NT Tourism’s operational checklist requirements. In addition to visitor infrastructure and accessibility, there is an emphasis on active websites and a social media presence.5

In 2017, the Northern Territory government announced opportunities for Indigenous arts and cultural enterprises to receive funding through the Arts Trail Regional Stimulus Grant Program. Funding has been made available for the upgrade of infrastructure and to improve access to and promotion of tourism experiences in preparation for the Territory Arts Trail’s 2019 marketing campaign.6 To date, over 25 Northern Territory art centres have received approximately $3.2 million in grant funding for various tourism initiatives under the terms of the Grant Program.7

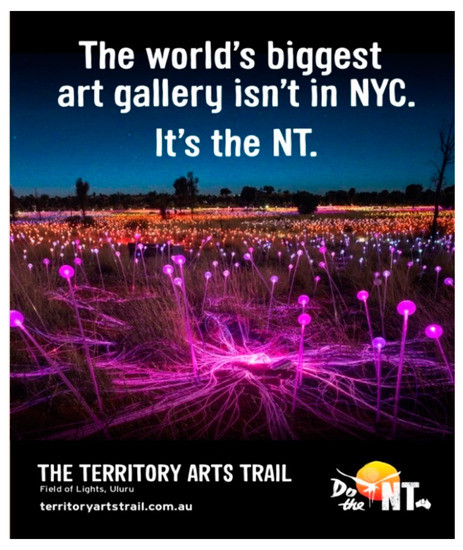

The target market for the Territory Arts Trail is identified as the domestic Australian traveller aged 35–49, who has a pre-existing interest in Indigenous art and culture and is seeking “new and distinctive experiences”.8 Interestingly, the campaign is not specifically directed at the mobile so-called Grey Nomad traveller who comprises 29% of the total caravanning population and often spends many months travelling widely in remote parts of Australia (Australian Government 2017). Nor are international travellers actively pursued under this campaign but there is an expectation of a flow-on effect (8). Advertising for the Territory Arts Trail containing vivid Northern Territory imagery is aimed at high foot traffic areas in major Australian cities with the primary message ‘The World’s biggest art gallery is the NT’ (8) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Northern Territory Arts Trail campaign image. Image sourced from the Territory Arts Trail Fact Sheet. Available online via a link at: http://newsroom.nt.gov.au/mediaRelease/28652 (accessed on 20 July 2019).

The Territory Arts Trail is arguably aspirational. The underlying demand for Indigenous tourism experiences is considered difficult to determine due to long-term incomplete data capture and methodological inconsistencies (Ruhanen and Whitford 2017; Mahadevan 2017). The accepted definition of an ‘Indigenous tourist’ as “a person who participates in at least one Indigenous tourism activity during their tourism experience” (Australian Government 2011) may be too broad for accuracy (Ruhanen et al. 2015). Ruhanen et al. (2015) and Ruhanen and Whitford (2017) have suggested that, together, these factors have led to overly optimistic expected demand and spending figures when compared to historical data. There is corresponding concern amongst some tourism researchers that government rhetoric promoting the perception of high levels of demand for Indigenous tourism is unsupported (Ruhanen and Whitford 2017; Akbar 2016), with tourist participation significantly lower than is generally believed.

An ‘Indigenous tourism activity’ is defined as a visit to an Indigenous site or community, or an experience with an Indigenous cultural activity or display (Australian Government 2011). Through their own analysis, Ruhanen et al. (2015) found that not only is the level of awareness of Indigenous tourism opportunities low amongst domestic and international tourists—25% and 20% respectively—but that those with a preference for engaging in Indigenous tourism experiences comprise only 12% of all tourists and those with the intention to participate sit at just 2%. Along with low tourist awareness, a general domestic tourist malaise due to ‘backyard’ familiarity appears to exist (Mahadevan 2017) and ambivalence that can be partially ascribed to the impact of negative media attention on remote Indigenous communities (Ruhanen et al. 2015). High travel costs to remote locations and the constraints of limited vacation time may add further doubt to tourist decision making (Akbar 2016; Ruhanen et al. 2015). The NT government’s advertising campaign for the Territory Arts Trail is arguably attempting to address only the macro level of the Indigenous tourism ‘awareness’ issue. As a consequence, remote art centres on the Territory Arts Trail, along with those located elsewhere in Australia, may benefit from being particularly strategic in making comprehensive and compelling online information available to engage the interest of potential tourists.

4. Art Centre Websites, Social Media and Cultural Tourism

This article now turns its attention to the development of information-rich art centre website content for cultural tourism purposes. Domestic tourists are of particular interest because they are identified as the target market for the Territory Arts Trail. In addition, website content rather than social media activity is the preferred platform for two reasons: firstly, because control over website content is maintained entirely by the art centre and secondly, due to the way in which websites are likely to be used for information gathering by consumers. While there is a dearth of current literature on the use of digital platforms in relation to art centres specifically, some previous research has confirmed that websites are considered critical to art centres and Indigenous tourism businesses generally (Bendor and Acker 2015; Petersen 2015; Akbar 2016).

By way of essential background, in 2018, 72% of small businesses (1–19 staff) in Australia had business websites, with the highest website penetration seen in the Cultural, Recreational and Personal Services sectors at 85% (Sensis 2018a). However, only 51% of small businesses had a social media presence (Sensis 2018a). Arguably, this suggests that consumers of information who act based on their prior experiences are most likely to first seek specific information from an art centre’s website. In addition, links from a business website generate the most social media traffic and higher visibility (Pant and Pant 2018; Sensis 2018b).

Websites reflect an enterprise’s identity and shape a consumer’s opinion about that enterprise—they are a virtual front-of-house. Shaltoni (2017) found that while social media is relatively easy to manage as a small business tool and generally costs little other than time to establish and maintain, websites will continue to be important into the near future because they allow full control of content with better search engine marketing and branding: “In other words, social media business pages are very important, but not enough” (Shaltoni 2017). This is a point that art centres should consider carefully when focusing their attention on their digital presence; comprehensive websites along with actively managed social media accounts both serve important and complementary purposes. The peak body Desart suggests that its art centre members largely focus their digital efforts in social media activity, particularly Instagram (Holcombe-James 2018). However, this article argues there is value in ensuring that a strategic and comprehensive art centre website exists alongside of any social media activity. In 2018, a surveyed majority of small businesses in Australia indicated that their websites had improved their business effectiveness largely due to increased exposure to their consumers, whereas social media’s perceived main advantage was in marketing and sales (Sensis 2018a, 2018b).

Most if not all remote art centres have websites. As mentioned previously, this is part of the Indigenous Art Centre Plan (Australian Government 2018) and many art centres sell their artists’ work online. However, a review of a number of remote art centre websites within the Northern Territory and beyond suggests that the potential exists to significantly enhance their content and embed far greater localised social, cultural, historical and geographic context around the art. This is, in effect, a subtle re-positioning of art centres as particular agents of knowledge transfer. Such web content instantly becomes a globally accessible and centralised repository of comprehensive text and images which are selected and managed by the art centre. As will be explained, it is information which may influence tourist decision making as well as facilitate greater localised Indigenous arts insight, and potentially, research. This is, of course, in addition to a website’s online art sales function, which is central to many art centre websites (Petersen 2015; Bendor and Acker 2015). In an approach of this kind—which is an art centre-driven undertaking—Indigenous artists have self-determined authorial scope and their voices have the power to directly educate and inform the cultural perceptions and understanding of a global audience.

As noted already, art centres operate under significant funding and staffing constraints and the enhancement of website content is no small project. However, options for supporting such a project exist. Conducting the research, interviews and the photography/video production needed could be managed by the art centre in collaboration with tertiary and cultural institutions through tailored programs undertaken by arts research interns and writers in residence. Professional arts writers and researchers can also be located through consultancy registers. Funding for website enhancement could be sourced through grants, including the Arts Trail Regional Stimulus Grant Program or the Commonwealth’s Indigenous Visual Arts Industry Support Program (IVAIS), which provides funding to art centres for activities that contribute to “the continued production, exhibition, critique, purchase and collection of Indigenous visual art” (Australian Government 2018–2019). Funding and necessary skill sets may also be sourced through corporate sponsorship and philanthropy, including engagement with volunteers. It is essential however, that the direction and oversight of such a project remains in the hands of the artists and art centre.

If there is no information, or no positive information about a destination, tourists will not visit (Hinch and Butler 2009). This underscores the importance of information that is easily accessible for travellers and optimised for mobile devices. It also underwrites the Territory Arts Trail’s emphasis on digital capabilities (8). Furthermore, Ruhanen and Whitford (2017) make the clear point that educational strategies must be scaffolded around Indigenous tourism by both governments and tourism enterprises in order to enhance cultural understanding and competencies in tourists. Comprehensive art centre websites incorporating extensive localised social, cultural and historical text and images can support this education process and prime pre-visit knowledge and interest. This seems especially important for independent travellers sourcing their own travel information, but also has relevance for those travelling with organised tour groups who visit art centres.

Some of the perceived barriers to the uptake of Indigenous tourism have been identified in the literature (Akbar 2016; Mahadevan 2017; Pomering and White 2011; Ruhanen et al. 2015): perceptions that Indigenous tourism is ‘inauthentic;’ concerns regarding remote travel; perceptions that Indigenous tourism experiences are not diverse and are already familiar to domestic tourists, along with the effect of damaging racial stereotypes and negative media attention. If these barriers to tourist participation are recognised by art centres, there is potential to address them. Strategic website content providing images and descriptions of the diverse visitor experiences and impressions to be found at the art centre and which counter pre-conceptions could be effective in this role. Additionally, descriptions on the art centre website of localised cultural information explaining language groups, kinship systems, storylines and custodianship obligations in a way that is acceptable to the community can support deeper cross-cultural awareness and interest—particularly when it is available to users in a centralized, accessible location. For example, the Central Land Council’s website9 provides cultural information of this kind which offers an interesting context for art-making activities—but only if tourists know to search for it.

Akbar’s (2016) doctoral research identified the attributes that are of most importance to Australian domestic consumers when considering remote Indigenous tourism—highly relevant information for art centres promoting their tourism experiences whether they are located on or off the Arts Trail. In order of preference the attributes are: breathtaking landscapes; iconic landmarks; economic development; interaction with local people; Dreaming stories; high quality fresh produce such as seafood; safety and preparation; meeting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people; Australian history; quality family/social time (Akbar 2016). A number of these preferred features are central to art centre tourism. Incorporating this information into website content where appropriate arguably has the potential to inform, refine and possibly influence tourists’ decision making.

Augmenting an art centre website with high-quality images and video of the surrounding landscape; images and video of artists working and on country; quotes from artists; explanations of the social, historical and cultural contexts within which the community operates—language, schooling, employment opportunities, health services—all paint a picture of contemporary community life which shapes the artists’ work and may also pre-prime particular interests in visitors. For example, Iwantja Arts’ website10 includes artist quotes and images in a way that captures aspects of their contemporary lives in Indulkana in South Australia and is both engaging and informative. Warmun Art Centre,11 located in Western Australia, includes website images of bush trips undertaken by artists and describes the important cultural rejuvenation, education and artistic development benefits found in those experiences.

Akbar’s (2016) findings indicate that Indigenous cultural tourists tend to be highly educated. This suggests they are likely to value undertaking their own in-depth research into art centre tourism options. Providing descriptive cultural, social and historical contexts for art-making as well as video and images, particularly of the physical geography of the community, may help tourists in selecting and favourably anticipating the likely scope of their art centre experiences.

Building cultural knowledge and competencies in Indigenous tourists is critical (Ruhanen and Whitford 2017) and the type of social and cultural information found on the website of art centre Buku-Larrnggay Mulka,12 located in Northeast Arnhem Land, is an example of this. It includes extensive video footage as well as specific information on clans, language, names and spiritual themes and clan-based modern history. Another strategy is leveraging business awards, particularly as economic development is viewed as an important tourism attribute. Ikuntji Artists13 in Central Australia displays images of their artists receiving a recent business award. This adds context and credibility to an art centre’s profile, particularly in the face of historical negative media attention towards Indigenous communities (Akbar 2016). Website links to media articles, publications and representing galleries and exhibition histories provide potential visitors with additional insight and a sense of an art centre’s scope of activities.

Promoting the relational nature of the social and cross-cultural exchanges, insights, connections and interpersonal experiences to be found in a visit to an art centre appears to be especially important (Jones et al. 2016). Artists taking on the role of educators and teachers, such as in an art centre-run workshop for example, can alter visitors’ preconceptions. In addition, Carson (2017) suggests that tourists who seek to experience the ‘backstage’ of cultural destinations are also motivated by the opportunity to ‘make,’ ‘do’ and also ‘watch.’ An immersive creative or cultural experience is something that art centres such as Maruku Arts14 at Uluru promote through their website with their painting workshops, and Waringarri Aboriginal Arts15 at Kununurra offer through their art centre and on-country walking tours. Websites should certainly be the platform upon which immersive art centre experiences, including multi-day educational field schools and volunteer opportunities, are explained fully, not the least as markers of their location-specific difference and diversity (Butler 2017).

The remoteness of some art centres as tourist destinations can be considered either a positive or a negative, depending on tourist attitudes and a range of variables such as transport, time available and tolerance for risk and discomfort (Akbar 2016). Smith (2012) makes the point that the journey to and from a cultural site is part of the process of negotiating and creating meaning before arrival at the destination; that a commitment is being made to the entire embodied experience. This aspect of active choice in the adventure of remote travel, and the potential for accessing unique and ‘breathtaking landscapes’ can be a valuable point of positive difference in the location details explained on an art centre’s website—along with thoroughly detailed instructions on how to reach the art centre, under what conditions travel may be attempted, whether permits are required for travelling on Aboriginal land and specific instructions for how to request those permits. Information is key (Hinch and Butler 2009).

5. Art Centre Websites as Platforms for Greater Insight into Indigenous Art and Culture

Whilst the potential economic and socio-cultural benefits to art centres derived from tourism campaigns such as the Territory Arts Trail could have positive community impacts (Ruhanen and Whitford 2017), Indigenous art centres have always operated under unique mandates. The Australian Senate Inquiry Indigenous Art—Securing the Future (Parliament of Australia 2007) confirmed that “4.7 Art centres have two key cultural roles: they facilitate the maintenance of Indigenous culture within the community, as well as facilitating the transmission of that culture to the world beyond the community” (Parliament of Australia 2007). Cultural tourism is just one of the ways in which art centres might fulfil this mandate and there are, of course, many others. Art centre managers actively seek global relationships with galleries and institutions to create opportunities for the exhibition and sale of contemporary Indigenous art. Artists participate in nation-wide art awards which draw large audiences such as the annual National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards and the Wynne Prize for landscape. Art and craft, such as spinifex or pandanus weaving, printed fabric and punu, or wood carving, are showcased in galleries and art fairs; art is sold online through art centre websites and onsite through art centre galleries. Joint projects are undertaken with non-Indigenous designers, such as the recent collaboration between artists from the remote Mangkaja art centre in Western Australia and Australian fashion label Gorman (ABC Kimberley 2019). In addition, ties are formed with tertiary institutions, enabling diverse Indigenous arts and culture research. In light of this mandate for cultural transmission, art centres—which are clearly foundational to the Indigenous arts sector—also have a unique grassroots opportunity to add much depth and accessibility to global Indigenous arts education and research via the authority of their own websites.

Interpreting and comprehending remotely produced Indigenous art requires an extensive matrix of knowledge: Indigenous cultural origins and visual systems, the ways meaning is communicated through art and an awareness of the social and historical conditions giving rise to its production (Myers 1994; Morphy 2008; Girgirba and Taylor 2017). Implicit in this knowledge matrix is a recognition of the intrinsic transcultural factors that have shaped Indigenous art since colonisation (Morphy 2008). As with the promotion of art centre tourism, expansive website content designed for the education of audiences—that is, cultural ‘transmission’—can provide grassroots social, cultural and historical context which is reflective of the contemporary lived experience of an artist in their community. Increasingly globalised ‘art worlds’ and a burgeoning art industry of collectors and investors have particular interests in context, and the understanding of context supports the making of those cross-cultural connections (Vogel 2013). In today’s globalised world, these connections must be driven by an appreciation of cross-cultural similarities, hybridities and differences. Digital platforms such as art centre websites have the potential to build greater contextual connections between the art and a global audience, with the increase in art collector and investor numbers also a major driver of demand for information which can be found easily and rapidly online (Vogel 2013).

An enhanced ‘knowledge transfer’ role played by art centres may also support the ability to sustain art sales in a global market. Acker (2016) identifies the need to contextualise Indigenous art for audiences as crucial to its future commercial viability. He maintains that education cannot be left to chance. Some international audiences in particular need a great deal of contextual background to form meaningful insight into Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art (Acker 2016). Indeed, McLean (2013) has suggested that the contemporary art world is such a highly contested space that Indigenous artists must actively seize what they want, they cannot rely on slow and uncertain change. Expansive, contextual art centre website content which promotes arts education can therefore also support to an art centre’s sales activities. One only has to wander through an art fair to see potential buyers searching for artist and art centre information on their phones.

Vogel (2013) is specific about information which has a critical relevance for creating cross-cultural context around art. Her approach focuses on social, historical and cultural links between the art and its audience and therefore has particular resonance with the way in which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art must be comprehended (Morphy 2008; Myers 1994; Neale 2014). Vogel describes the making of cross-cultural connections between art and audiences in the following way: discussing art in terms of values, its role in society, and in terms of contemporary developments; considering art in relation to social, economic, political and scientific global developments, and making connections to “build bridges between traditions, cultures, and historical eras” (Vogel 2013).

In concrete terms, Vogel’s approach for placing valuable context around art for audiences can also be transformed into a strategic framework for website content. In doing so, we also conveniently incorporate a number of the important Indigenous tourism preferences identified in Akbar’s (2016) research including local geography and landscape, insight into Indigenous communities, economic development, Dreaming stories and Australian history. A website based on Vogel’s approach with descriptive text, images and video reflecting and describing the contexts of Indigenous art may therefore have multiple potential benefits: supporting Indigenous self-determination and cultural knowledge retention, enhancing arts education and research, as well as promoting the art centre’s commercial objectives of sales and tourism. When curated by the art centre, it reinforces the artists’ own agency and self-determination in this knowledge transfer. Certainly, galleries and institutions also provide valuable online descriptive text and images for exhibiting artists, but this is managed largely at the discretion of the gallery or institution.

A tailored art centre website using Vogel’s context-driven approach for making connections between Indigenous art and its audiences would include the following elements adapted as appropriate:

- High-quality images and descriptions of the physical location of the art centre including its surrounding community and, importantly, its natural environment. As an example, some of the images seen on the website of Mimili Maku Arts16 located in South Australia depict artists displaying their work in interesting ways within the dramatic local landscape.

- Descriptions of the contemporary social contexts for art production in the community. This includes culturally sensitive explanations of such things as inherited cultural rights and authority, gender responsibilities and opportunities for education and employment. An example of this can be seen on the website of Injalak Arts17 from West Arnhem Land, which incorporates localised language, community, country and custodianship information into its ‘Culture’ webpage.

- Descriptions of the contemporary cultural contexts for art production, such as the significance of Dreaming cosmology, connection to country and the contemporary and customary role and value of art in society. These are fundamental to gaining insight into the art.

- Identification of current and historical issues affecting the local community and region such as land rights and environmental matters. An example of this is evidenced in the Pormpuraaw Art and Culture Centre’s18 webpage describing the use of ‘ghost nets’ in art-making, which are abandoned fishing nets found washed up in the Gulf of Carpentaria causing far reaching impact to marine life.

- Art historical information relevant to the art centre as a whole. This may include the origins of art production in the community. For example, Ikuntji Artists19 in Central Australia mentions their important historical role as a former women’s centre on their website. In addition to this, images of work produced over time, explanations of key visual systems, mediums and materials, and the ways meaning may be communicated through art are vital for making audience connections. Information of this kind can be seen in the explanations of memorial poles, bark painting and fibre weaving on the website of Arnhem Land’s Buku-Larrnggay Mulka.20

- Artist biographies, samples of work and exhibition histories. The art centre website may be the only record of an artist’s body of work which is accessible to a global audience. Without including individual artist biographies, a collective, ethnographic frame for the art may be implied and this is agency-limiting for an artist and at odds with the positioning of Indigenous art as contemporary fine art. Finally, clear links to relevant publications, partner galleries and media coverage provides additional and valuable context around the art.

The art centre website framework described above takes an expansive and complementary approach to the usual knowledge transfer paradigms for Indigenous arts education. It also conveniently incorporates content which addresses some of the perceived barriers to Indigenous tourism, highlights a number of the most preferred features of remote Indigenous tourism and fosters cross-cultural competencies in those interested in visiting art centres. The framework emphasises the distinct value in a localised approach, allowing every art centre to highlight their own cultural, social, historical and geographic diversity.

6. Conclusions

Art centre cultural tourism is a focus of this article, with the Northern Territory’s investment in the new Territory Arts Trail a catalyst for inquiry. This article has argued that art centres can strategically position themselves to provide deep context around their art with the use of a practical website framework for tailored content which offers both cultural tourism and Indigenous arts education benefits. Developing an enhanced website with the framework described is a project that must be directed and controlled by an art centre and its member artists using external skills as needed. It consequently supports artists’ self-determination and agency. Art centres are certainly constrained by funds and resources and this makes new projects particularly challenging. However, some initial solutions have been suggested in the article to overcome these constraints.

This article presents the following main points in support of its argument for a framework to create strategic art centre website content for cultural tourism and Indigenous arts education purposes:

- Australia’s new Northern Territory Arts Trail campaign includes a number of remote art centres as tourism destinations. Existing research into Indigenous tourism uptake indicates low awareness and an even lower preference for its participation. Given that tourists first require information in order to make their travelling decisions, the opportunity exists for art centres to make strategic website content available to inform and possibly influence prospective cultural tourists.

- Art centres can enhance their websites with content to address some of the perceived barriers to remote Indigenous cultural tourism and to cultivate cross-cultural competencies in tourists. Existing tourism research is also utilized as a basis for sharpening and refining content to highlight the Indigenous tourism attributes most important to domestic consumers (Akbar 2016), and which may have the potential to influence tourist decision making.

- Art centres can create strategic website content which highlights the social, historical, cultural and geographic contexts of Indigenous art as a way of making cross-cultural connections between the art and audiences (Vogel 2013). This contextual approach is localised, adaptable and educational. It supports art sales and it also conveniently incorporates a number of the most important features of remote Indigenous tourism, such as ‘breathtaking landscapes’ as well as information to address tourism barriers. In this article, explaining context is used as the scaffold of a framework for tailored art centre website content with the aim of supporting informed cultural tourism and localised insight into Indigenous arts.

Art centre websites have a global reach and art centres themselves have a mandate for the transmission of Indigenous culture beyond their community. Connections between Indigenous art and any of its global audiences, whether cultural tourists or otherwise, must be scaffolded by an appreciation of cross-cultural similarities, hybridities and differences. Knowing this, art centres can utilise the framework for website content developed here to provide rich context around the art which supports their cultural tourism initiatives and furthers Indigenous arts education and insight.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- ABC Kimberley. 2019. Gorman Mangkaja Collection Breaks New Ground for Indigenous Fashion Design Collaboration. July 21. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-07-21/gorman-fashion-label-collaborates-with-indigenous-artists/11328248 (accessed on 14 August 2019).

- Acker, Tim. 2016. Somewhere in the World: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art and its Place in the Global Art Market. Cooperative Research Centre for Remote Economic Participation Research Report CR017. Available online: https://nintione.com.au/resource/CR017_AboriginalTorresStraitIslanderArtPlaceGlobalArtMarket.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2019).

- Akbar, Skye. 2016. Marketing Remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Tourism to Australians. Ph.D. Thesis, University of South Australia and Cooperative Research Centre for Remote Economic Participation, Adelaide, Australia, April. Available online: https://nintione.com.au/resource/AkbarS_PhD_MarketingRemoteAboriginalTorresStraitIslanderTourismToAustralians.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- Altman, Jon. 2005. Brokering Aboriginal Art: A Critical Perspective on Marketing, Institutions and the State. In Kenneth Myer Lecture in Arts and Entertainment Management. Edited by Ruth Rentschler. Geelong: Centre for Leisure Management Research, Bowater School of Management and Marketing, Deakin University, pp. 1–24. Available online: https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/145184/1/Altman_Myer_2005_0.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- Andrews, Hazel. 2009. Tourism as a ‘moment of being’. Suomen Anthropology: Journal of the Finnish Anthropological Society 34: 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government. 2011. Snapshots 2011-Indigenous Tourism Visitors in Australia. Tourism Research Australia. Available online: https://www.tra.gov.au/Archive-TRA-Old-site/Research/View-all-publications/All-Publications/snapshots-2011-indigenous-tourism-visitors-in-australia (accessed on 23 August 2019).

- Australian Government. 2017. TRA Case Study: Caravan Industry Association of Australia. Austrade: Tourism Research Australia. Available online: https://www.tra.gov.au/Data-and-Research/publications (accessed on 21 July 2019).

- Australian Government. 2018. Indigenous Art Centre Plan. Department of Communications and the Arts. pp. 1–9. Available online: https://www.arts.gov.au/documents/indigenous-art-centre-plan (accessed on 20 July 2019).

- Australian Government. 2018–2019. Forecast Opportunity View—IVAISO2018/19. Grant Connect. Available online: https://www.grants.gov.au/?event=public.FO.show&FOUUID=B1ADBC83-C31B-FEEA-FD2A105C84FFEA61 (accessed on 28 July 2019).

- Bendor, Iris, and Tim Acker. 2015. The Use and Benefits of eBusiness to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Centres—Summary of Key Finding from Bachelor of Business (Honours) in Marketing. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Economies Project. Available online: https://nintione.com.au/resource/Summary_UseBenefitsEBusinesstoAboriginalAndTorresStraitIslanderArtCentres_BachBusHonsMktg.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2019).

- Butler, Sally. 2017. ‘Temporary Belonging’: Indigenous Cultural Tourism and Community Art Centres. In Performing Cultural Tourism: Communities, Tourists and Creative Practices. Edited by Susan Carson and Mark Pennings. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, pp. 13–28. ISBN 978-1-315-17446-4. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, Susan. 2017. Methodologies of Touristic Exchange: An Introduction. In Performing Cultural Tourism: Communities, Tourists and Creative Practices. Edited by Susan Carson and Mark Pennings. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, pp. 1–9. ISBN 978-1-315-17446-4. [Google Scholar]

- Congreve, Susan, and John Burgess. 2017. Remote Art Centres and Indigenous Development. Journal of Management and Organization 23: 803–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Chris, and C. Michael Hall. 2016. Contemporary Tourism: An International Approach. Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers Ltd., p. 115. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, David. 2012. Meaning, Encounter and Performativity: Threads and Moments of Spacetimes in Doing Tourism. In The Cultural Moment in Tourism. Edited by Laurajane Smith, Emma Waterton and Steve Watson. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, pp. 19–37. ISBN 978-0-415-61115-2. [Google Scholar]

- Girgirba, Kumpaya, and Ngalangka Nola Taylor. 2017. Follow in their Footprints. In Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters; Edited by Margo Neale. Canberra: National Museum of Australia Press, pp. 26–27. ISBN 9781921953293. [Google Scholar]

- Hinch, Tom, and Richard Butler. 2009. Indigenous Tourism. Tourism Analysis 14: 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcombe-James, Indigo. 2018. Social Media—How to Make it Work. In The Desert Art Centre Guidebook. Edited by Karen Riederer. Alice Springs: Desart Inc., p. 112. Available online: https://desart.com.au/wp-content/uploads/sites/40/Desart_guidebook_e-version_2018.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2019).

- Ingram, Gloria. 2005. A Phenomenological Investigation of Tourists’ Experience of Australian Indigenous Culture. In Indigenous Tourism: The Commodification and Management of Culture. Edited by Chris Ryan and Michelle Aicken. Oxford: Elsevier, pp. 21–34. ISBN 0-08-044620-5. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Tod, Jessica Booth, and Tim Acker. 2016. The Changing Business of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art: Markets, Audiences, Artists and the Large Art Fairs. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 46: 107–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Janice, Pi-Shen Seet, Tim Acker, and Michelle Whittle. 2019. Barriers to grassroots innovation: The phenomenon of social-commercial-cultural trilemmas in remote indigenous art centres. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevan, Renuka. 2017. Examining Domestic and International Visits in Australia’s Aboriginal Tourism. Tourism Economics 24: 127–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, Ian. 2013. Surviving ‘The Contemporary:’ What Aboriginal artists want and how to get it. Contemporary Visual Art + Culture Broadsheet 42: 167–73. [Google Scholar]

- Morphy, Howard. 2008. Becoming Art: Exploring Cross-Cultural Categories. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, p. 167. ISBN 9781921410123. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, Fred. 1994. Beyond the Intentional Fallacy: Art Criticism and the Ethnography of Aboriginal Acrylic Painting. Visual Anthropology Review 10: 10–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale, Margo. 2014. Whose Identity Crisis? Between the Ethnographic and the Art Museum. In Double Desire: Transculturation and Aboriginal Contemporary Art. Edited by Ian McLean. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 287–310. [Google Scholar]

- Pant, Gautam, and Shagun Pant. 2018. Visibility of Corporate Websites: The Role of Information Prosociality. Decision Support Systems 106: 119–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parliament of Australia. 2007. Report on Indigenous Art—Securing the Future: Australia’s Indigenous Visual Arts and Craft Sector; Art Centres. pp. 27–52. Available online: https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Environment_and_Communications/Completed_inquiries/2004-07/indigenousarts/report/index (accessed on 17 August 2019).

- Petersen, Kim. 2015. Sustainability of Remote Aboriginal Art Centres in Australian Desert Communities. Ph.D. Thesis, Curtin University, Perth, Australia. Available online: https://espace.curtin.edu.au/handle/20.500.11937/1170 (accessed on 14 August 2019).

- Pomering, Alan, and Leanne White. 2011. The Portrayal of Indigenous Identity in Australian Tourism Brand Advertising: Engendering an Image of Extraordinary Reality or Staged Authenticity? Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 7: 165–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riederer, Karen, ed. 2018. The Desert Art Centre Guidebook. Alice Springs: Desart Inc., p. 6. Available online: https://desart.com.au/wp-content/uploads/sites/40/Desart_guidebook_e-version_2018.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2019).

- Ruhanen, Lisa, and Michelle Whitford. 2017. Indigenous Tourism in Australia: History, Trends and Future Directions. In Indigenous Tourism: Cases from Australia and New Zealand. Edited by Michelle Whitford, Lisa Ruhanen and Anna Carr. Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers Ltd., pp. 9–23. ISBN 978-1-911396-40-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhanen, Lisa, Michelle Whitford, and Char-lee McLennan. 2015. Indigenous Tourism in Australia: Time for a Reality Check. Tourism Management, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Chris. 2005. Introduction: Tourist-Host Nexus—Research Considerations. In Indigenous Tourism: The Commodification and Management of Culture. Edited by Chris Ryan and Michelle Aicken. Oxford: Elsevier, pp. 1–11. ISBN 0-08-044620-5. [Google Scholar]

- Sensis. 2018a. Yellow Digital Report 2018: The Online Experience of Consumers and Small to Medium Businesses (SMBs). pp. 45–54. Available online: https://www.yellow.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/2018-Yellow-Digital-Report.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2019).

- Sensis. 2018b. Yellow Social Media Report 2018: Part Two-Businesses. pp. 7–12. Available online: https://www.yellow.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Yellow-Social-Media-Report-2018-Businesses.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2019).

- Shaltoni, Abdel Monim. 2017. From Websites to Social Media: Exploring the Adoption of Internet Marketing in Emerging Industrial Markets. The Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 32: 1009–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, Jane. 2019. The State of Australia’s Indigenous Languages—And how we can help people speak them more often. The Conversation. January 21. Available online: http://theconversation.com/the-state-of-australias-indigenous-languages-and-how-we-can-help-people-speak-them-more-often-109662 (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- Smith, Laurajane. 2012. The Cultural ‘Work ‘of Tourism. In The Cultural Moment in Tourism. Edited by Laurajane Smith, Emma Waterton and Steve Watson. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, pp. 210–34. ISBN 978-0-415-61115-2. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, Sabine B. 2013. Bridging the World: The Role of Art Criticism Today. In The Global Contemporary and the Rise of the New Art Worlds. Edited by Hans Belting, Andrea Buddensieg and Peter Weibel. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 255–60. ISBN 9780262518345. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, Steve, Emma Waterton, and Laurajane Smith. 2012. Moments, Instances and Experiences. In The Cultural Moment in Tourism. Edited by Laurajane Smith, Emma Waterton and Steve Watson. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-0-415-61115-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wroth, David. 2016. Tiwi Design Art Centre: A Peaceful Place for Art. Japingka Aboriginal Art Gallery. Available online: https://japingkaaboriginalart.com/articles/tiwi-island-arts-centre/ (accessed on 28 July 2019).

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).