Abstract

This essay offers object biographies of two examples of Lakȟóta beaded regalia that traveled with Wild West performers to France in 1889 and in 1911, respectively, as exemplars of Gerald Vizenor’s concept of survivance. By examining the production of the objects by women artists within the Lakȟóta community and visually analyzing their designs, this article highlights the regalia as an opposition to both settler colonial political suppression and enforced attempts of cultural assimilation. The article stresses that the beadwork’s materiality bears traces of its intended circulation and public display that are enacted when Lakȟóta individuals wore the regalia in the context of Wild West performance in France. Both when rooted in the Lakȟóta community and when circulating through Wild West shows, the objects evince Lakȟóta survivance. When the regalia was acquired by non-Native individuals in France, who projected new meanings onto the objects, the function of the regalia as a public statement of Lakȟóta survivance subtly continued to operate through generated revenue for the community and through the visibility of Lakȟóta culture through continued circulation.

1. Introduction

When Wild West performers traveled to France in the decades before World War I, they transported Lakȟóta artistry and material culture with them.1 Performances ranged from re-enacting US western expansion in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in a large arena packed with spectators to living in exoticized villages claiming to feature quotidian indigenous life for visitors (Burns 2018b, p. 14). Elaborately beaded regalia, made by Lakȟóta women and worn by the performers, was a central part of these public displays. Lakȟóta regalia, referred to in Lakȟóta as wókȟoyake (Powers 1994, p. 66),2 comprises buckskin clothing, including shirts—in either tunic or jacket cuts—which are often painted, typically beaded, and embellished with hair and/or feathers; pants with a beaded band and fringe along the outside of the leg; and moccasins that are beaded on the top of the shoe.

This article analyzes two examples of beaded regalia that traveled to France in the context of Wild West performance. One, likely made in or before the 1880s, was probably worn by Íŋyaŋ Matȟó (Rocky Bear, c. 1850–1907), a performer with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West who participated in the tours in London in 1887 and in Paris in 1889 (Burns 2018b, pp. 31–35) (Figure 1). The other, made around the turn of the century, was worn by Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká (Spotted Weasel, c. 1852–c.1925–31), a Lakȟóta man who traveled with a group of Lakȟótas and Iroquois to live at the Jardin d’Acclimatation, a human zoo in the Bois de Boulogne, in 1911 (Figure 2) (Schneider 2011). Both sets of regalia are currently in French collections.

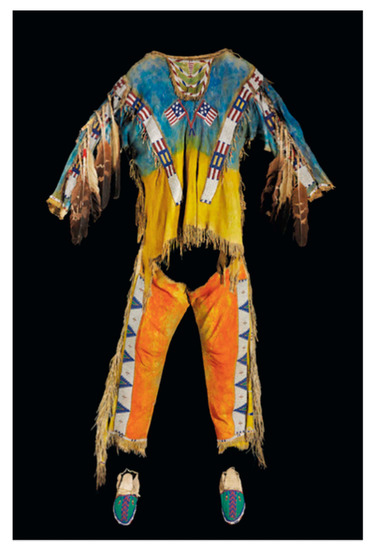

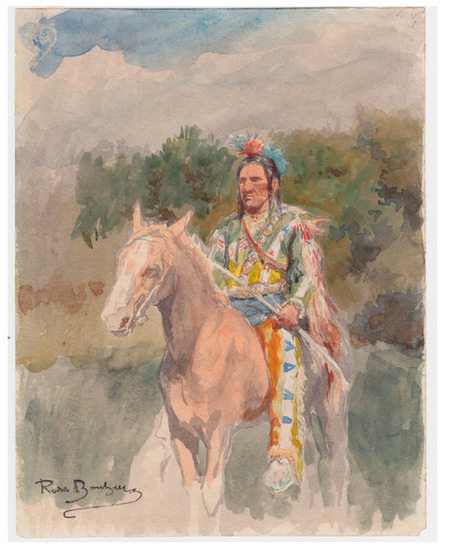

Figure 1.

Plains Indian buckskin tunic and leggings, c. 1880s, beadwork, eagle feathers, paint, and quillwork on deerskin. Musée de l’Atelier Rosa-Bonheur, Château de By, Thomery, France. Photograph taken by Christie’s Paris. Used by permission of the Musée de l’Atelier Rosa-Bonheur.

Figure 2.

Regalia of Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká. (a) front of jacket, pants, and moccasins, (b) back of jacket and pants. Late nineteenth or early twentieth century. Buckskin and beadwork. Musée franco-américaine du château de Blérancourt. Photograph taken by Adrien Didierjean and used by permission of RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY.

These objects intersect with several discourses related to the politics of American Indian art production and circulation in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As Johannes Fabian argues in Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object, common presumptions in the nineteenth century imagined so-called “primitive” people and their arts as insular and unchanging remnants of the past (Fabian 1983, p. 1; Meyer 2001, p. 35). In concord with this presumption, many assumed that American Indians were a “vanishing race” (Dippie 1982). Early scholarship analyzed beaded regalia as decontextualized anthropological specimens (Wissler 1904; Wissler 1915; Orchard [1929] 1975; Greci Green 2001, pp. 142–45). As a result of US government policies of assimilation, beading was concomitantly presumed to be a dying art. William Orchard, for instance, wrote in his 1929 study of beadwork, “with a new mode of living forced upon the Indians, the day is not far distant when distinctively Aboriginal American art will be a thing of the past” (Orchard [1929] 1975, p. 167). Beaded objects were also often sold as the tour circulated. As a result, the regalia might be dismissed as “inauthentic” canned culture billed for tourists or altered for a commercial market. For instance, in one of his critical essays on the victimization of Native performers, French author Éric Vuillard asks his reader to imagine the scene after a Buffalo Bill’s Wild West performance: “The spectacle is over; people wander round the Indian craft stalls and the hot-dog stands. They glance at the goods and try on a necklace. They’d love to have a tomahawk or even a feather headdress! This is what we now call merchandising. The Indians are selling products that derive from their genocide” (Vuillard 2016, p. 93). In his critique, Vuillard links the sale of Lakȟóta arts to erasure and commodification rather than survival. Yet, as this essay explores in dialogue with the scholarship of Ruth B. Phillips, Marsha Clift Bol, Linda Scarangella McNenly, Adriana Greci Green and Jenny Tone-Pah-Hote, the blending of non-Native commerce and Native art production is layered with nuance and spaces for hybrid meanings and interventions that reveal the agency of Native artists and performers (Phillips 1998; Cohodas 1997; Meyer and Royer 2001; Bol 1999; McNenly 2012, pp. 90–99; Greci Green 2001; Tone-Pah-Hote 2019). While some beaded regalia was made for spectacle and possible sale—performers were required to possess regalia to even audition for traveling shows like Buffalo Bill’s Wild West (Friesen 2017, pp. 83–84)—the artform makes statements about Lakȟóta cultural identity.

This essay highlights how Lakȟóta regalia worn at Wild West shows articulates Lakȟóta survivance. As Anishinaabe critic Gerald Vizenor has asserted, “Native American Indians have resisted empires, negotiated treaties, and as strategies of survivance, participated by stealth and cultural irony in the simulations of absence in order to secure the chance of a decisive presence in national literature, history and canonry” (Vizenor 2008, p. 17). He defines survivance as “the action, condition, quality, and sentiments of the verb survive, ‘to remain alive or in existence,’ to outlive, persevere with a suffix of survivancy” (Vizenor 2008, p. 19). Vizenor focuses on contingent, rather than fixed, identities as a central strategy to challenge political and social dominance in the US settler colonial frame (Vizenor 1994, p. 4). He defines imposed non-Native structures of identity as “manifest manners” in their enacting the discourse of manifest destiny (Vizenor 1994, pp. 5–6). Vizenor uses the term “trickster hermeneutics” to describe the flexible, adaptable, and deferred identities that American Indians have embraced to combat oppression (Vizenor 1994, pp. 14–15). He writes “Survivance is a practice, not an ideology, dissimulation, or a theory” which is “earned by interpretations” (Vizenor 2008, p. 11).

Art and material culture offer key opportunities for statements of survivance. Lakȟóta production of beaded objects opposed settler colonialism by asserting Lakȟóta culture. In its engagement with both tradition and with innovation in Lakȟóta art-making, beading can be read an example of what Jolene Rickard has described as “visual sovereignty” (Rickard 2011, p. 472). Rickard argues that the use of the concept of sovereignty can, like survivance, enable “self-defined renewal and resistance” in the face of oppression (Rickard 2011, p. 467). She concludes, “Sovereignty could serve as an overarching concept for interpreting the interconnected space of the colonial gaze, deconstruction of the colonizing image or text, and Indigeneity” (Rickard 2011, p. 471). As a cultural practice that continued and even flourished during US subjugation of the Lakȟóta nation, beading enacts a form of visual sovereignty. In its circulation, as well, Lakȟóta regalia communicates survivance. Vizenor and other Native studies scholars have considered how mobility can enact survivance through transmotion, which Vizenor explores as a “sense of native motion and an active presence [that] is sui generis sovereignty… Native stories of survivance are the creases of transmotion and sovereignty” (Vizenor 1998, p. 15). In their mobilities and adaptability, these beaded objects enact survivance, declaring the cultural sovereignty of the Lakȟóta nation as they deflect assimilation.

Object biographies of two examples of Lakȟóta beaded regalia that traveled with wild west performers to France in 1889 and in 1911 scaffold this analysis of Lakȟóta survivance. The essay addresses the production and materiality of beaded regalia, which inscribes the objects’ intended visibility and circulation; its wearing by Lakȟóta performers, which enables the mobility of Lakȟóta culture; and its appropriation in France by non-Native individuals. Even in its re-purposing in French visual culture, I suggest that the regalia continues to proclaim Lakȟóta survivance through generated revenue and through the objects’ continued circulation, as their Lakȟóta makers had intended, as a public representation of their culture. In the materiality of the garments, the gendered labor of production, and in the regalia’s subsequent mobility and re-imaginings by a French painter and a French filmmaker, regalia builds a temporally specific and rooted and also spatially-expansive Lakȟóta cosmopolitanism that operated as statements of survivance.

2. Making Regalia: Communicating Survivance

During this period, beaded deerskin regalia was prepared, handsewn, and embroidered by Lakȟóta women for use within the community and, as many Lakȟóta began participating in Wild West shows in the 1880s, in performance contexts (Bol 1985; Hansen 2018; Lyford 1979, pp. 19, 31; Amiotte 2007, p. 246). No evidence exists of non-Native production of these objects before World War I with this degree of artisanship.3 The craft of tanning and beading threaded with sinew, or animal tendons (Lyford 1979, p. 38), was taught by Lakȟóta women to their daughters and granddaughters (Lyford 1979, pp. 58–60; Hansen 2018, p. 98). Beaded hides are so carefully sewn that the thread passes only within the thin layer of the buckskin, rather than through to the other side (Lyford 1979, p. 62). The art form was elevated through the establishment of craft societies for women, which enabled the passing of knowledge about beading and the celebration of beadwork production alongside other techniques, such as quillwork (Hansen 2018, pp. 124–25; Schneider 1983, pp. 112–13; Powell 1977, pp. 40–41; Berlo and Phillips 2019, p. 49).

Rather than an art form in an isolated community, beading was always tied to Lakȟóta cross-cultural interaction. For instance, its origins were found in trade with Euro-US settlers, which initially brought large pony beads, and, as we see here, tiny glass “seed beads” to trade in the borderlands (Penney 1992, p. 155; Lyford 1979, pp. 56–58; Orchard [1929] 1975, pp. 16–18, 95–96; Hansen 2018, p. 82). The beads were largely produced in Venice and in the Czech Republic (Bol 2018, pp. 8, 18). Embroidered objects made by Lakȟóta and other Plains and Eastern woodland nations were often traded among Native American nations as well as with settlers.

In the 1840s, Lakȟóta women began to bead elaborate designs on tunics to function as warrior shirts for Lakȟóta men. Such shirts identify their wearers—in Lakȟóta, wičháša itȟáŋčhaŋ—as leaders with authority to speak for their community (Hansen 2018, pp. 107–9; Horse Capture and Horse Capture 2001; Bol 2018, p. 20; Amiotte 2007, p. 246; Greci Green 2001, pp. 166–68; Powell 1977, pp. 47–50). They also served as metaphorical protection (Horse Capture 2016). In the pre-Reservation context, such shirts signified the prowess and social position of Lakȟóta warriors, and were often conferred upon admission to warrior societies (Hansen 2018, pp. 106–9). In giveaway ceremonies, in which leaders displayed their wealth and generosity by offering fine objects to others in the community, these shirts were prized belongings, believed to retain the sacred powers of previous wearers (Berlo and Amiotte 2016; Lyford 1979, p. 31; Schneider 1983, pp. 114–15; Bol 1989, pp. 310–13; Greci Green 2001, pp. 64–69; Amiotte 2007, p. 247). These social functions were continuous between the pre-Reservation and Reservation periods. As Bol argues, “The Lakota belief that clothing served as protection through its beaded designs and prayers was a pre-reservation value that was carried into the reservation era [as a] … method for combating the threat of assimilation” (Bol 2018, p. 20).

When Lakȟótas began traveling in Wild West performances in the 1880s, the regalia was re-purposed for circulation in this context. Luther Matȟó Nážiŋ (Luther Standing Bear, 1868–1939) recalled that when he helped with auditions for Wild West performance in Rushville, Nebraska in 1904, he participated in a “feast, to which all the Indians who wanted to go out with the show were invited to come in full costume, so we could ‘size them up’ and select those who had good outfits” (Standing Bear 1928, p. 270). In the early twentieth century, Lakȟóta women continued to make such garments, though in the decades following World War I, many traveling Lakȟóta performers began to acquire their garments through trade catalogues and larger scale manufacture moved into the non-Native world (Friesen 2017, pp. 83–84).4

The earlier of these two garments was made in advance of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West’s travel to Neuilly, a suburb of Paris for seven months in 1889. It may be an earlier shirtwearer tunic repurposed for the Wild West tour (Figure 1). In this shirt (Figure 3), a canvas of deerskin is painted with floating planes of blue on the shoulders and arms, fading into vibrant yellow at the base. Often featured on these shirts (see also Figure 4), these colors signify sky and rock, motifs central to Lakȟóta ontology as the iconic colors of Lakȟóta spirit beings Škáŋ, the most important spirit of the sky, “the blue of the dome above the world” (Dooling 1984, p. 6), and of Íŋyaŋ, the spirit of rock “from whom everything began,” signified by the color yellow (Dooling 1984, pp. 5–6; Posthumus 2018, pp. 75–77; Horse Capture and Horse Capture 2001, p. 148; Hassrick 1964, p. 247). The colors underscore the shirt as a microcosm of the Lakȟóta world, crystalizing connections between warriors and spirit beings. Porcupine quills affix eagle feathers and hair locks, both potent symbols of power (Hansen 2018, p. 108), to the sleeves of the shirt. Angular bands of beadwork connect the arms and body. Along the pants, red, yellow and green crosses intersperse between large blue triangles with smaller green, red and yellow triangles within; these shapes are among those commonly used on beadwork. While color held recognized meaning, these abstract shapes are not believed to have universal coding or symbolism within the Lakȟóta community (Bol 1989, p. 72; Koch 1977, p. 59; Powell 1977, p. 36).

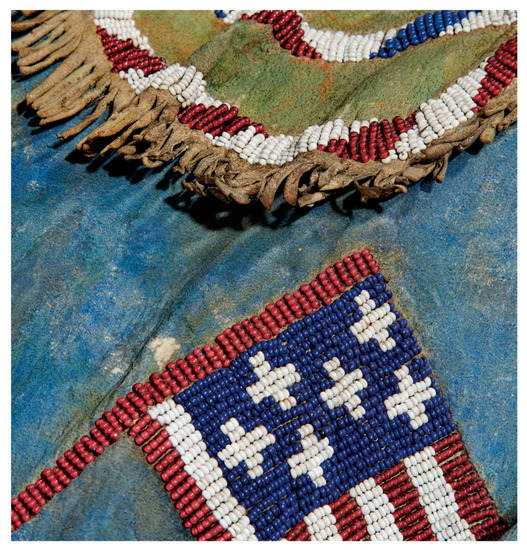

Figure 3.

Plains Indian buckskin tunic (detail of Figure 1), c. 1888, beadwork, eagle feathers, paint, and quillwork on deerskin. Musée de l’Atelier Rosa-Bonheur, Château de By, Thomery, France. Photograph taken by Christie’s Paris. Used by permission of the Musée de l’Atelier Rosa-Bonheur.

Figure 4.

Oglála Lakȟóta Shirt, c. 1868, tanned hide, wood cloth, pigments, glass beads, dyed porcupine quills, golden eagle feathers, northern flicker feathers, human hair, sinew, 97.79 cm × 48.26 cm. Plains Indian Museum, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, WY, Paul Dyck Collection, NA 202.1052. Used by permission of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West.

The attribution of this jacket to a Lakȟóta artist is suggested by its similarity with tunics credited to Lakȟóta beaders (Figure 4), such as a shirt from the late 1860s, which shares the blue and yellow fields, the shape of the beaded bands that form diagonals across the torso and that trace from shoulder to wrist, the lockets of human hair draping below the abstract beaded patterns, and the fringe at the base (Hansen 2018, pp. 110–11).5 Both beaded patterns exhibit what Joseph D. Horse Capture and George P. Horse Capture describe as the “strong, solid patterns surrounded by free background space [that] defined Lakȟóta beadwork before the mid 1880s” (Horse Capture and Horse Capture 2001, p. 147). The strips of beads threaded in a row on a single string, known as the line stitch, are visible in a detail of the pant beading depicting concentric isosceles triangles in a form descriptively titled the ‘tipi’ (Figure 5) (Lyford 1979, p. 74). This beading technique links the regalia with the practice of Lakȟóta women artists (Horse Capture and Horse Capture 2001, p. 147; Lyford 1979, pp. 61–62; Orchard [1929] 1975, pp. 151–54).

Figure 5.

Detail of Plains Indian buckskin leggings (Figure 1), c. 1888, Musée de l’Atelier Rosa-Bonheur, Château de By, Thomery, France. Photograph taken by Christie’s Paris. Used by permission of the Musée de l’Atelier Rosa-Bonheur.

Red, white and blue dominate the color scheme of the beadwork. This color choice might have been appropriate for the international audiences watching Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, though other Lakȟóta beaded objects that did not travel exhibit a similar color scheme (Pohrt 1975; Herbst and Kopp 1993). Reference to the colors of the US flag was literalized with heraldic flags at the center of the shirt on both sides. Yet, as several scholars have argued, the flag and colors did not likely offer a straightforward claim of allegiance in the early Reservation period (Bad Hand 1993; Schmittou and Logan 2002; Powers 1996). Rather, the flag often implied the possession of the power of an enemy. Anthropologists Douglas A. Schmittou and Michael H. Logan have observed that the Lakȟóta nation “resisted Euro-American expansion more successfully, and with greater resolve, than any other Plains tribe” and they were also the community which depicted US flags the most in their beadwork (Schmittou and Logan 2002, p. 560). Schmittou and Logan continue, “…Lakota artisans may have employed flag imagery as a visual code—one hidden to whites but known to them—for recalling, more so celebrating, victorious military campaigns against U.S. soldiers or other intrusive whites” (Schmittou and Logan 2002, p. 579). The US flag imagery likely functions as a power play, as well as a statement of the warrior tradition’s engagements with and resistance to the US military. The color scheme held multilayered resonance, rather than symbolizing blind patriotism. For example, the colors build a syncretism; as contemporary Lakȟóta artist Lynn Burnette, Sr. described, “The American flag’s red, white, and blue colors have always been interesting, good colors to Native Americans. The blue to us was where the forces we pray to are. The spirit world, Upper World. Red is power. White represents purity. The colors worked in very neatly” (cited in Schmittou and Logan 2002, p. 583).

This warrior shirt builds such visual layers. On a tab at the back of the shirt between two cross forms, the thunderbird, Wakíŋyaŋ, a powerful spirit of the sky (Hassrick 1964, p. 247) that became a Ghost Dance symbol in 1890, literally presides over the flags (Figure 6). The red, white and blue on the bands is ruptured by a blue and yellow rectangle that echoes the blue and yellow painting of sky and rock on the shirt itself, as the reference to Lakȟóta ontology intersects with the US colors. Within the flags, the six stars do not connect with the existing number of US states, as frequently the case in beaded US flags in Lakȟóta art (Schmittou and Logan 2002, p. 583). Furthermore, the design is not a star, but a cross motif (Figure 7), as often produced in this flag imagery (Schmittou and Logan 2002, p. 583) and frequently in beadwork.6

Figure 6.

Rear view of Plains Indian buckskin tunic, c. 1888, beadwork, eagle feathers, paint, and quillwork on deerskin. Musée de l’Atelier Rosa-Bonheur, Château de By, Thomery, France. Photograph taken by Christie’s Paris. Used by permission of the Musée de l’Atelier Rosa-Bonheur.

Figure 7.

Detail of Plains Indian buckskin tunic (Figure 1), c. 1888, Musée de l’Atelier Rosa-Bonheur, Château de By, Thomery, France. Photograph taken by Christie’s Paris. Used by permission of the Musée de l’Atelier Rosa-Bonheur.

The overlapping US and Lakȟóta referents suggest the garment’s ties to its fraught historical moment. The early Reservation period was initiated as the Lakȟóta nation was politically and militarily suppressed by settler colonial expansion (Utley 2004; Ostler 2004; Gibbon 2003, pp. 150–61; Maddra 2006, pp. 17–18). What had been established as the Great Sioux Reservation in 1868 had been reduced in 1876 after a fruitless Black Hills gold rush, further enforcing Lakȟóta transition from nomadic hunting to settled society. In the spring of 1888 and again in March of 1889, on the eve of the departure of about 100 Lakȟóta performers to Paris, and, perhaps on the occasion of the production of this regalia, US government commissions traveled to the region, seeking to cut the remaining land in half with a low purchase price, and redesign the site as six small reservations separating the various Lakȟóta, Dakóta and Nakóta bands that comprise the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ (Greene 1970; Hoover 1989).7 Drawing on the Dawes Allotment Act of 1887, the commissions hoped to limit tribal movements and incite cultural assimilation by allocating farming lands to individuals and instating a bureaucratic system of oversight through delivering rations.

In the context of a push for assimilation, Lakȟóta’s choice of clothing was often politically inflected. Adopting Anglo clothing might suggest adaptation (whether willing or under duress), whereas wearing traditional clothing such as regalia implied an insistent tie with Lakȟótas’ cultural sovereignty (Bol 1989, pp. 387–88; Burns 2018b, pp. 128, 130).8 For example, when the commission negotiating the Sioux Act of 1889 arrived at Pine Ridge Reservation, they found staunch resistance in the Lakȟóta men wearing regalia who refused to sign the agreement (Greene 1970, pp. 52, 55). In spite of contentious debate, backdoor dealing resulted in enough signatures from other reservations in the Dakotas to pass the agreement in August 1889, and North and South Dakota formed as states in November of that year (Burns 2018b, p. 188, fn 11).

The continued production, donning, and circulation of beaded regalia during the enforced settlement of Lakȟóta society should be read as acts of survivance (Bol 1989, p. 442; Bol 1993; Bol 2018; Hansen 2007, pp. 235–36). This practice can be understood as an example of what Native American Studies scholar Jenny Tone-Pah-Hote has described as “expressive culture” in her study of Progressive-era Kiowa art and performance, which she defines as “regalia, adornment, figural art and dance” (Tone-Pah-Hote 2019, p. 5). This concept of “expressive culture” offers a productive frame for understanding Lakȟóta beaded regalia. Beading is decorative and symbolic within Lakȟóta belief systems. It is activated by being worn, enlivened by the human body that moved within it (McNenly 2012, pp. 90–99; Lyford 1979, p. 32). Within the community, its continued production subtly operated against oppression. Bol notes that regalia operates simultaneously as a “personal and a group identifier” (Bol 1989, p. 387). Lakȟóta beadwork marks an example of the processual and dynamic enacting of Lakȟóta identity, exhibiting the contingencies that characterize Vizenor’s framing of survivance. Beadwork is dynamic in its styles, colors, and designs both within and across communities, and it speaks to both continuity and change within Lakȟóta material culture. As Caroline Lyford writes, “The history of Sioux quill and beadwork is one of constant movement” (Lyford 1979, p. 66).

As Bol, Emma Hansen and other scholars of Lakȟóta beadwork have argued, the art form increased in vibrancy, thickness of beading, and complexity in the era of the most forceful repression of the Lakȟóta nation from about 1885 to 1914 (Bol 1989, p. 385; Bol 1993; Hansen 2018, pp. 93–94; Penney 1992, p. 49). Increasingly, objects were beaded entirely, rendering the hide beneath invisible. Beading grew as a symbol of Lakȟóta resilience and adaptation in response to occupation, and its subversion slipped under the radar of agents’ surveillance. As the Native American art historian Janet Berlo and Oglála Lakȟóta artist Arthur Amiotte have observed, “It is fortunate… that late nineteenth-century lawmakers did not understand the social role of art objects in Plains cultures. If they had, they likely would have been alarmed by the proliferation of fine beadwork during the Reservation Era and banned that as well” (Berlo and Amiotte 2016, p. 49).

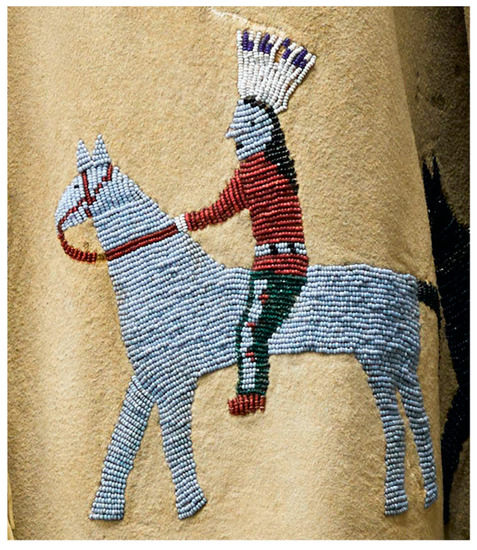

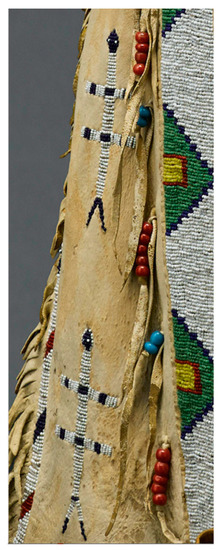

Beaders also turned towards narrative forms in the 1890s (Figure 2) (Bol 1989, pp. 406–30; Greci Green 2001, p. 182). In the slightly later jacket, which probably dates from the early twentieth century, the brightly-colored beaded forms construct images of warriors on horseback wearing war bonnets and stepping forward on an invisible groundline. Across the back, figures wear war bonnets with long trailers packed with feathers, signifying success in battle and generous deeds within the community (Figure 8). The attention to the beaded clothing of these figures adds a meta-level to the design of beading depicting beading. Some of the figures wield pistols, an iconography that transforms a traditional Lakȟóta warrior into a modern-day tribal protector and may signify reaction to US incursion. The strings of beads in the line stitch are sometimes applied in perpendicular directions—as in the warp and weft on a loom—to create subtle three-dimensionality, as seen in the horse’s head (Figure 9). The adaptation of a tailored jacket to be open in the front compared with the tunic design of the earlier warrior shirt is informed by Euro-US dress and intermarrying communities. Both the form of the shirt and the beading style shift in this short period.9 The jacket is paired with an earlier set of pants that shares triangular beading designs from the 1880s (see Figure 5).10 Schematic black and white dragonfly motifs line the edge (Figure 10). Dragonflies function as protective symbols in battle for several Plains nations (Hansen 2018, p. 53; Powell 1977, p. 50). In the reuse of the pants, the symbol reinforces the warrior past narrated by the beading in the jacket.

Figure 8.

Regalia of Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká. Detail of back (Figure 2b). Musée franco-américaine du château de Blérancourt. Photograph taken by Adrien Didierjean and used by permission of RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY.

Figure 9.

Regalia of Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká (Detail of Figure 2a). Late nineteenth or early twentieth century. Buckskin and beadwork. Musée franco-américaine du château de Blérancourt. Photograph taken by Adrien Didierjean and used by permission of RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY.

Figure 10.

Regalia of Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká (Detail of Figure 2a). Late nineteenth or early twentieth century. Buckskin and beadwork. Musée franco-américaine du château de Blérancourt. Photograph taken by Adrien Didierjean and used by permission of RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY.

The transition in style highlights a gender shift in Lakȟóta art practice; narrative art had traditionally been the purview of Lakȟóta men to celebrate earlier successes in hunting and battle on tipis, muslin or ledger paper (Berlo 1996; Bol 1985, p. 34; Lyford 1979, pp. 12–19). In the transition to reservation life, women took on the role of storytellers and translators of Lakȟóta histories as beading turned more explicitly figural and even narrative (Bol 1985, p. 42). Bol details this transition: “Lakota women supported the male tradition of prestige, assuming the tradition of depicting hunting and warfare scenes on their male relatives’ clothing and pipe bags in the female medium of beads in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries” (Bol 2018, p. 129). The labor of these women, whose names were largely unrecorded in the production of regalia but who attained “wealth and status through [their] craftwork,” shaped this Lakȟóta survivance (Schneider 1983, p. 116). This research reinforces Tone-Pah-Hote’s conclusion that Kiowa women artists in the Progressive era used beadwork as part of Kiowa nation building (Tone-Pah-Hote 2019, p. 13). Lakȟóta women artists’ representations of Lakȟóta histories are especially indicative of survivance in a period in which much of women’s longstanding political economy within their communities was sidelined; the settler colonial project expressly invited diplomatic dialogue, such as treaty signing, only with Lakȟóta men (Estes 2019, pp. 82–83).

As Bol has deftly argued, the narrative in beadwork is both retrospective and forward looking: “Because art was an important link to the values of the old order, the continued production of traditional objects was not only a pleasant task but a reinforcement of meaningful social organization… their culture maintains continuity with the past, but not just as a replica of an earlier era; Lakota culture is also the present and the future” (Bol 1999, p. 228). This beaded jacket reveals the transition in Lakȟóta beadwork from abstract and symbolic to narrative that framed a major shift in Lakȟóta art-making in the early Reservation period. This transition redefined gender roles and reasserted Lakȟóta culture. In sum, Lakȟóta beaders used the visual to claim Lakȟóta cultural sovereignty.

3. Mobility as Lakȟóta Survivance

These two Lakȟóta beaded garments articulated Lakȟóta survivance both within and outside the local community, not only in production, but also in circulation. The regalia’s materiality enacts adaptations of Lakȟóta culture in dialogue with performance, settler colonial forces, and cosmopolitanism. The objects offer both a rootedness as a statement of cultural sovereignty and an intended, incipient mobility that articulates Lakȟóta survivance abroad. As Tone-Pah-Hote observes, “Recognizing the strategic uses of mobility by Native people during this time helps us to understand their survival” (Tone-Pah-Hote 2019, p. 6). This research also reinforces Elizabeth Harney’s and Ruth B. Phillips’s recent call to consider “the importance of mobility in stories of modernity” within “broader transnational frameworks” (Harney and Phillips 2018, pp. 19, 22).

Beaders anticipated the circulation of regalia in the non-Native world as a public assertion of Lakȟóta identity. For example, W.H. Barten, who operated a mercantile store in Gordon, Nebraska and who participated in the trade in these objects, observed in 1907, “The Indians here are making a good deal of beadwork to send to their relatives in your show” (cited in Bol 2018, p. 220). Buffalo Bill’s Wild West spurred production of beadwork, not only for performers to wear, but also to sell (Bol 1989, pp. 431–32). While some early writers on beadwork complained that “the trader’s influence is responsible for the perceptible decline” (Orchard [1929] 1975, p. 167), scholars of Lakȟóta beadwork can make no connoisseurly distinction between objects made within the community and those produced for circulation, performance or sale (Bol 1999, p. 223). Unlike objects made in other Native American nations, such as Hopi katsinam, which were produced differently for tourist trade than for ritual worship (Pearlstone 2001), there is no clear differentiation between beadwork intended for tourists, circulating performers, and for the Lakȟóta community. Rather, beaders planned for potential mobility and alternate contexts.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West acted out the quelling and assimilation of American Indian communities in its display of the mythic settling of the American West and used Lakȟóta regalia to authenticate its purportedly historical narrative (Warren 2005; Kasson 2000, p. 162). It placed US expansion across the continent within the wider frame of European colonialism (Rydell and Kroes 2005, p. 111). Show organizers sought to take advantage of crowds gathering for “international curiosities” at the Exposition Universelle. Lakȟóta performers operated within a slippage of performing both as themselves and as actors (McNenly 2012; Peers 2007; Deloria 1981). In this context, the regalia asserted the continued presence of Lakȟóta people, belying the claim of erasure presented by Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. While stereotypes shaped these displays, American Indians wearing regalia and circulating representations of them also challenged the demands of assimilation asserted by the Office of Indian Affairs (Maddra 2006; Moses 1996; Friesen 2017; Greci Green 2001, p. 117).

Bol has argued that Lakȟóta beadwork in Wild West performance “provided a means for the Lakota to announce their national identity literally to the world; and the fact that audiences responded with enthusiasm and overwhelming numbers validated Lakota identity” (Bol 1985, p. 46). These dialogic objects, she asserts, functioned as “mediator[s] between the non-Indian world and Lakota tradition, being an acceptable form in both worlds” (Bol 1985, p. 46). I would add that the regalia reinforced Lakȟóta survivance both in its rooted context within Lakȟóta community and in its increasing participation in the global economy as it traveled. Though before non-Native eyes, the performance context perpetuates the function of these shirts as public statements of Lakȟóta identity. The vibrant colors and elaborate designs were deliberately eye-catching, seeking publicity through vivacity. The performers who carried this regalia to Europe followed in the footsteps of dozens of Native performers before them, including the Ojibwe and Iowa participants in George Catlin’s Parisian stint in 1845 and a group of Omahas who lived at the Jardin d’Acclimatation outside of Paris in 1883 (Weaver 2014; Feest 1999; Wernitznig 2007). Expectations of these Lakȟóta performers were framed by these earlier encounters, and artists from Eugene Delacroix to Maximilien Luce made representations in response to these visitors (Horton 2016; Cabau 2014).

The earlier regalia was likely worn by Íŋyaŋ Matȟó in Paris at Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in 1889. This attribution is aided by a watercolor painting (Figure 11) made by Rosa Bonheur, a French animalier who made paintings in the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West encampment in Neuilly (Burns 2018b, pp. 61–77). The watercolor depicts this celebrity performer on horseback wearing the regalia, its vibrant colors apparent in the blue triangles along the pant legs and the blue and yellow wash of the buckskin. Íŋyaŋ Matȟó’s regalia functioned on a few registers at once. His clothing reinforced stereotypes about American Indian identity, which became increasingly framed by the feathered bonnet and beaded buckskin garments in this period (Ewers 1965; Bol 1999, p. 215; Bol 1989, p. 431; Greci Green 2001, p. 105). These stereotypes are cemented by newspaper representations that identify him as “Un Peau-Rouge (A Redskin)” rather than a named individual (Tissandier 1889, p. 88).

Figure 11.

Rosa Bonheur, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Performer on Horseback, Íŋyaŋ Matȟó, 1889, watercolor on paper. Private collection. Photograph taken by the author and reproduced with permission of the owner.

It can be difficult to obtain sources on Native performers and equally difficult to interpret them given the scrutiny of reservation agents and the Office of Indian Affairs. Furthermore, as McNenly argues, “resistance” in the context of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West is often “evasive rather than oppositional” (McNenly 2012, p. 69). As a celebrity Buffalo Bill’s Wild West performer, Íŋyaŋ Matȟó navigated tenuous political terrain in both adapting to US government assimilation efforts and continuing to perpetuate traditional Lakȟóta culture (Maddra 2006, pp. 77–80; Burns 2018b, pp. 32–25, 59–62). Documents trace Íŋyaŋ Matȟó’s oscillation between acceptance and critique of settler colonial politics. He sometimes wore Anglo-US clothing (photographs, McCracken Research Library, Buffalo Bill Center of the West), and in a statement to the acting commissioner of Indian affairs Robert V. Belt, who was investigating possible mistreatment of the Native American performers in 1890, described himself as “a ‘progressive’ Indian who had always worked with the government, despite incurring the wrath of his own people” (paraphrased by Maddra 2006, p. 77). But in that same year when he returned from France, he also told the Chicago Tribune that the performers had “seen two hells—Pine Ridge Agency and Mount Vesuvius” (Poor Lo 1890). In 1896, he was again labeled as a “progressive” (Peace Jubilee 1896).

In Paris, Íŋyaŋ Matȟó made comments to the press about the chaos in the French Assemblée Nationale compared with political discourse in the Lakȟóta nation (cited in Napier 1999, p. 396). He critiqued US settler colonial policy as he expressed memories of the pre-reservation Plains in response to Albert Bierstadt’s The Last of the Buffalo (1888, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC) then on view in Paris (Burns 2018a, pp. 141–45). He noted the history of the Plains landscape of nomadic Lakȟóta bands, “when the Indian was master of all he could survey, and he then surveyed a large tract” (Burns 2018a, p. 141). The Lakȟóta performers in Paris in the summer of 1889 contested the Sioux Act, which would open eleven million acres to non-Native settlement. When Whitelaw Reid, who served as the US ambassador to France, visited the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West encampment to elicit signatures, the performers refused to sign (Burns 2018b, p. 58). As a celebrity performer and spokesperson for the group, Íŋyaŋ Matȟó’s role as a wičháša itȟáŋčhaŋ is retained. In this context, his shirt-wearing fortified his authority to speak, perpetuating the function of Lakȟóta warrior societies in a conflicted context. While curator Ted Brasser has suggested that by the late nineteenth century, the concept of the wičháša itȟáŋčhaŋ “had lost its political significance,” suggesting that the shirts became obsolete signifiers (Brasser 2000, p. 131), in the context of attempted oppression of the Lakȟóta nation, as individuals steered uneasy politics that called for complete assimilation, I suggest that this traditional garment likely retained its ideological significance. His regalia demarcated a presence of Lakȟóta local culture abroad during a period of persistent attempts at erasure. In wearing it in performance and circulating in it in Paris and in Marseilles on this tour, Íŋyaŋ Matȟó enacted Lakȟóta survivance in France as he disrupted presumptions of American Indians as disappearing. The beadwork intercepts the settler colonial fantasy of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. Íŋyaŋ Matȟó also invokes trickster politics as he embraces the slippage of meaning between performance and reception. For example, he evaded fixed identities when he noted his ability to subvert the expectations of his audience. For instance, he noted in 1896 that “Sioux have plenty fun, too. He dance Omaha dance when he feel like fun; white man no understand and say it war dance; no war dance, but dance for fun… White man no understand all of Indian fun…” (cited in Kasson 2000, p. 212). Íŋyaŋ Matȟó’s deflection of “manifest manners,” and choice to display, or to obscure, Lakȟóta culture proclaimed an agency reinforced by the regalia.

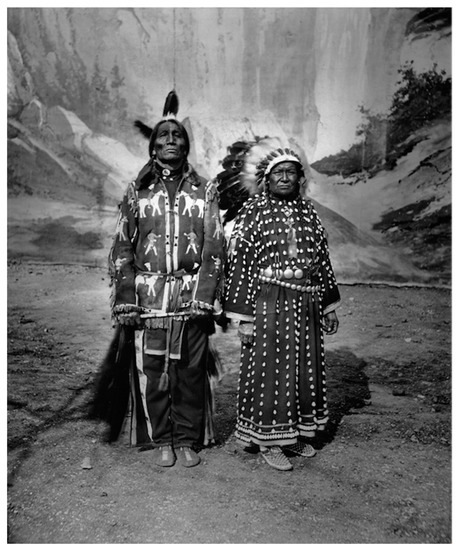

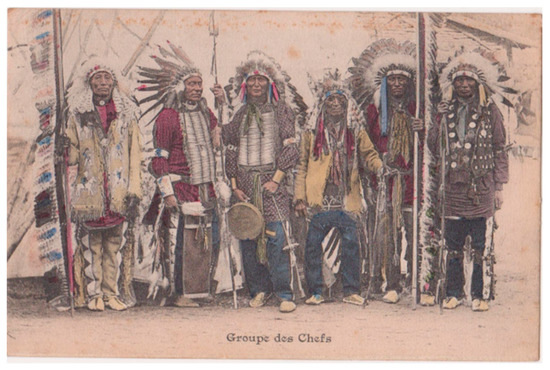

The later piece of narrative beaded regalia was used by Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká, a celebrity Lakȟóta performer in the early twentieth century. He was an irregular traveler with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West beginning in 1895 (Burns 2018b, pp. 45–47), but participated regularly in European tours of other American Indian groups. In the years before World War I, he joined performance tours in London, Brussels, and Hamburg. His mobility is anticipated by the mobility of the figures within the beaded imagery on his jacket. He wears the regalia in photographs and postcards from London in 1909, alongside his wife Ȟanŋté Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká (Cedar Spotted Weasel, 1851–ca. 1934) (Figure 12) and at the Jardin d’Acclimatation in Paris in 1911 (Figure 13), where he appears at far left in a postcard inaccurately projecting every individual as a “chief.” In both images, the garment appears oversized for him, his hands disappearing under the edges of the sleeves and the pants baggy. The misfit suggests that it may have been inherited in a giveaway or from another performer, evidence of the Lakȟóta practice of generosity within the community. Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká vivifies a Lakȟóta warrior past, less through the shirt’s hybrid jacket model, and more through the circulation of the beaded narrative motif of the figures.

Figure 12.

Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká and Ȟanŋté Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká in London, 1909, photographic print, 29 cm × 24 cm, Denver Public Library, X-32146. Photograph used by permission of Denver Public Library.

Figure 13.

Postcard of “Group of Chiefs” “Groupe des Chefs” at the Jardin d’Acclimatation, Paris, 1911, Collection of Didier Lévêque, Paris. Photograph used by permission of the owner.

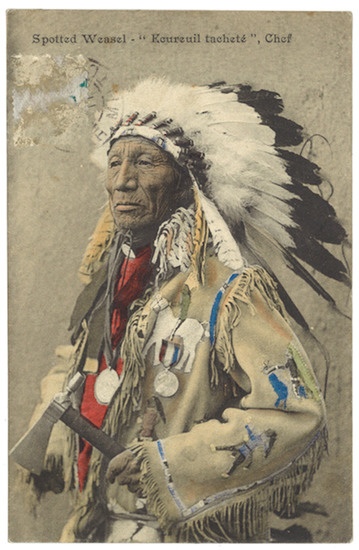

A hand-colored postcard depicting Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká wearing the regalia, a war bonnet, and two peace medals while holding a tomahawk circulated from the Jardin d’Acclimatation in 1911 (Figure 14). The juxtaposition of medals and beaded narrative suggests a layered dialogue of diplomacies; peace medals were offerings from the US government to American Indian dignitaries who participated in treaties and negotiations in Washington, DC (Lubbers 1994), yet as with the US flag on beadwork, wearing them did not necessarily signal allegiance. As the thunderbird image presides over the flags (Figure 6), the beaded figure on horseback straddles the medal on Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká’s jacket. In the context of the beaded narrative that speaks to the warrior history of the Lakȟóta nation, the medals imply Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká’s power and diplomacy skills in negotiating those contemporary politics.

Figure 14.

Postcard of Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká, Paris, 1911, Collection of Didier Lévêque, Paris. Photograph used by permission of the owner.

Even as the beaded garments circulated in hybrid Native and non-Native contexts, they maintained their potential to convey Lakȟóta survivance. They offered a layered public assertion of the survival, adaptation, and mobility of Lakȟóta. As Bol has argued, Wild West performance, “provided the arena for external reinforcement of the cultural self-image, with costume acting as an important vehicle” (Bol 1985, p. 44). This cosmopolitan mobility expands scholarly understanding of Lakȟóta culture; as Berlo and Amiotte have recently argued, “For far too long, outsiders have tended to romanticize and reify so-called traditional Plains life, as if it were separate from a larger world.” Instead Berlo and Amiotte “stress the complexity and cosmopolitan nature of Native life” (Berlo and Amiotte 2016, p. 34) that Lakȟóta beadwork traveling abroad also exemplifies. As Maximilian C. Forte insists, the terms “indigenous” and “cosmopolitan” need not be incompatible (Forte 2010, p. 14). Lakȟóta survivance through circulating beadwork is shaped by the performance context for which regalia was used. This adaptation is a marker of survivance. In spite of some mistranslations in reception and the structured frame of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, the garments asserted Lakȟóta culture in France through the performers who wore them.

4. French Projections: Visibility and Lakȟóta Beadwork in French Art and Visual Culture

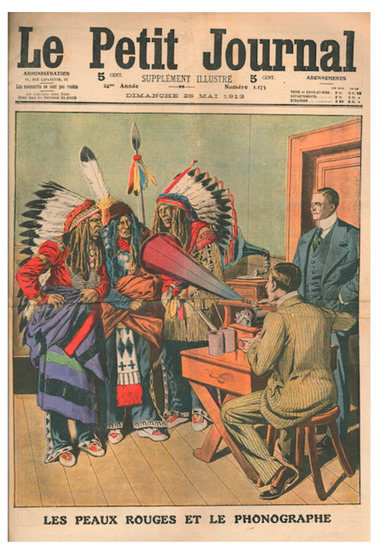

Dominant discourse in fin-de-siécle France held that American Indians were disappearing (Burns 2018b, p. 16). In a critical article published on the eve of the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890, Le Petit Journal asserted, that soon “the Sioux will be no longer… except an object for collection” (les Sioux ne seront plus… que des pieces de collection) (Nos Gravures 1890, p. 8). The same magazine printed a cover illustration in 1913 that reified such presumed erasure in figuring a scene reported from Washington, D.C. of American Indians with various Plains objects, including war bonnets, dentalium shell vests, a tobacco bag, a spear, and beaded pants and jackets as they spoke into a recording device enabled by the phonograph (Figure 15). The language recording would enable historians to study Lakȟóta culture because, according to the accompanying article, “this disappearance is inevitable” (cet disparaton est inéluctable) (Explication 1913, p. 162). The emphasis on the garments in this context implies that these, too, are obsolete relics of a past, destined for a museum after the anticipated extinction of Plains culture. The figures are framed as pre-modern in the face of the newest technology, the recording phonograph, which projects like a bullhorn into their faces. This defeatist language has infiltrated some current writing on Buffalo Bill’s Wild West; Éric Vuillard for instance, argues that the performance “relegated the Indians to imperceptibility” during “the final moments of their history” (Vuillard 2016, pp. 127, 137). Historically and today, Vizenor would describe these perspectives, which imply the Lakȟóta culture and people as extinct, as indicative of “manifest manners,” which “favor the siumulations of the indian traditionalist, an ironic primitive with no cultural antecedence” (Vizenor 1994, p. x). Survivance counters these presumptions and “simulation with stories of cultural conversions and native modernity” (Vizenor 1994, p. x).

Figure 15.

Cover of Le Petit Journal, “American Indians and the Phonograph” (“Les Peaux Rouges et le Phònographe”). 25 May 1913. Collection of the Author. Photograph taken by the author.

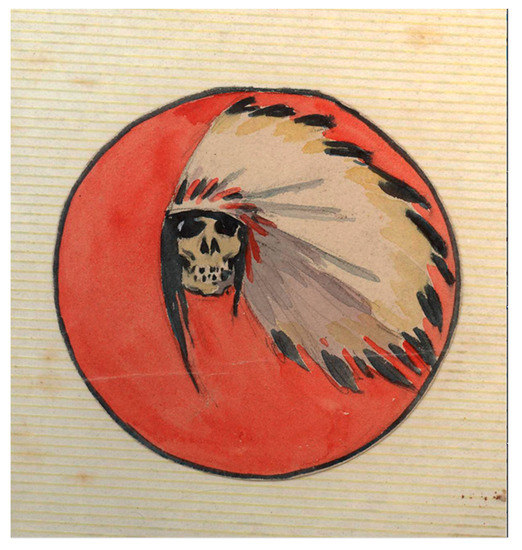

French painter Rosa Bonheur and actor Jean Paul Arthur Hamman, the French individuals who acquired Íŋyaŋ Matȟó’s and Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká’s regalia when they returned to Pine Ridge Reservation, may have shared these expectations of American Indian disappearance. Bonheur wrote in a letter in the context of her visits to the encampment in Neuilly at Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, “You know, I’ve got a real passion for this unfortunate race, and it’s utterly deplorable that they’re doomed to extinction by the white usurpers” (Burns 2018b, p. 69). Hamman, who adopted the nickname “Joë” (pronounced Jo-eh) when he began acting in French-made silent westerns, made a sketch of a skull wearing a war bonnet and encased in a blood-red circular medallion (Figure 16). His pairing of death with a war bonnet is unequivocal. Bonheur and Hamman had seen earlier performances of American Indian travelers in France (Burns 2018b, pp. 12, 43). Both re-purposed the regalia in their own art projects in painting and film, Bonheur in a series of paintings made during the last ten years of her life, and Hamman as an actor in a 1912 film, Prairie en Feu, produced in the Camargue in the south of France. These representations impose new registers of meaning on the regalia, which become exoticized costumes that frame Bonheur’s and Hamman’s investments in their local politics and cultures (Burns 2018b, pp. 43–45, 49–54, 64–85). In their appropriations, both artists make presumptions of the regalia’s rootedness in Lakȟóta culture, yet it is the mobility of these objects, a trickster politics, that activated this transnational entanglement.

Figure 16.

Joë Hamman, sketch of medallion with skull and war bonnet, undated. Pen, ink and watercolor on paper, collection of Jacques and Chantal Nissou, Fontvieille, France. Photograph taken by the author and reproduced with permission of the owner.

How might the acquisition of the regalia, and French artists’ representations of Lakȟóta people wearing it, convey Lakȟóta survivance, even in the face of romanticizing tropes of Indianness and presumed erasure? Within projections of meaning in the non-Lakȟóta world, is survivance retained? This section argues that these examples of beaded regalia still held the potential to communicate Lakȟóta survivance through the benefit of sale to the performers and their families and through the insistent visibility of the Lakȟóta nation that continued, and even expanded through these non-Native projections.

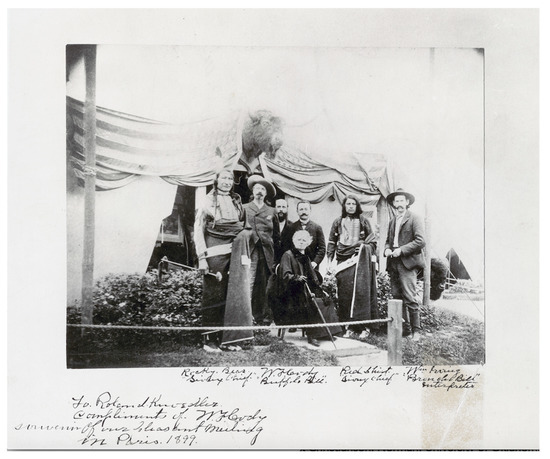

4.1. Sale

Bonheur’s partner, the US painter Anna Klumpke, suggests that the regalia was a gift from art dealer Roland Knoedler after she had spent time painting in the encampment at Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in Neuilly. Bonheur wrote that after “lunch in [William F. Cody’s] tent with M. Tedesco, Mr. Knoedler, and two magnificent Indians,” “Mr. Knoedler gave me the great chief’s superb costume over there” (Klumpke 1997, pp. 193, 24). A sitting in which Íŋyaŋ Matȟó stands at left marks this event with a photograph printed and inscribed to Knoedler by Cody (Figure 17). Knoedler may have negotiated its transfer as gift, or purchased the regalia from Íŋyaŋ Matȟó directly. If the former, it can be seen as part of the legacy of Lakȟóta generosity that framed giveaways within the community. US sculptor Cyrus Dallin met Bonheur in the encampment, and recalled that Bonheur had given Íŋyaŋ Matȟó a ring (Dallin n.d., pp. 5–6). Thus, there may have been a gift exchange, or of currency, for Íŋyaŋ Matȟó’s regalia.

Figure 17.

William F. Cody and group at Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, Paris, 1889. McCracken Research Library, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, P.60367. Used by permission of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, WY.

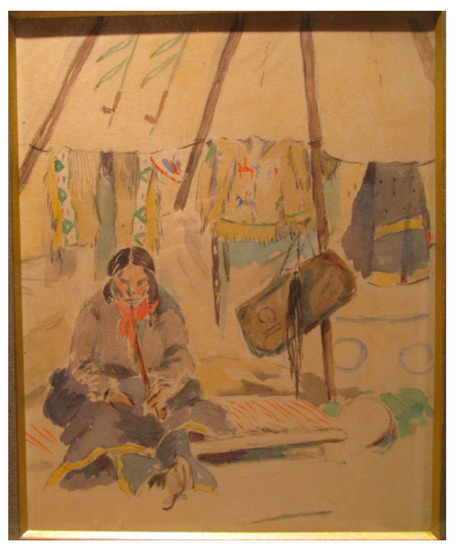

Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká’s regalia was probably purchased after the performer’s visit to the Jardin d’Acclimatation in 1911 by Hamman, an Indian enthusiast. Its collector later spun elaborate stories of its having been a gift at Pine Ridge Reservation in 1904 (Hamman 1973; Burns 2018b, pp. 43–45), a claim rendered improbable through the existence of the postcards depicting Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká wearing the jacket in London in 1909 (Figure 12) and at the Jardin d’Acclimatation in 1911 (Figure 13 and Figure 14) as well as doctored photographs of Hamman that replace the background of a Paris garden with tipis (Dubois 1993, p. 27; Burns 2018b, p. 45).11 While narrative beadwork depicting figures on horseback became common in this period, no two identical beaded jackets are extant. Hamman commemorated his unlikely story in a later watercolor imagining Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká contemplatively smoking a long pipe inside a tipi, with the regalia hanging on a line behind him as though the warrior was resting before the laurels of his narrated past (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

Joë Hamman, Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká, nd, watercolor, Collection of Jacques and Chantal Nissou, Fontvieille, France. Photograph taken by the author and reproduced with permission of the owner.

Even as commodities in a global economy, Lakȟóta regalia continued to offer visual proof of Lakȟóta survivance. As Erik Cohen, a historian of tourism, argues, “commoditization does not necessarily destroy the meaning of cultural products… old meanings… may remain salient” (Cohen 1988, p. 383). Cohen intriguingly suggests that even as objects are sold, other discourses may remain. Phillips and Christopher B. Steiner reinforce the possibilities in the interwoven meanings between art and commerce in the settler colonial context; they posit, “The makers of objects have frequently manipulated commodity production in order to serve economic needs as well as new demands for self-representation and self-identification made urgent by the establishment of colonial hegemonies” (Phillips and Steiner 1999, p. 4). The market for beaded Lakȟóta objects brought money and opportunities for public statements of continued Lakȟóta presence. Economics, politics, and the visual interweave in these proclamations of Lakȟóta survivance.

The sale of beaded regalia at Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and other Wild West performances might be tied with Lakȟóta survivance. Letters to Wild West performers in France such as Jacob Ištá Ská (Jacob White Eyes, c. 1870–1935), who traveled on the 1905–1906 tour, were peppered with requests for beaded vests and moccasins (Venture and Temple 2010, p. 43). This revenue supplemented income from performing. Objects were frequently sold as the tour moved, and beading for the performers increased, as Barten had observed in 1907 (Bol 2018, p. 220; Bol 1989, p. 432). Some performers sent money from participating in the show and from selling Lakȟóta-produced objects to their families (McNenly 2012, pp. 57–61). Such sales also enabled the acquisition of European goods, which were then transported back to the Plains (Standing Bear 1928, p. 268). For instance, Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká returned from England in 1909 with five trunks (Moses 1996, p. 200). As Amiotte described in an interview, relatives plied performers with lists of requested objects to acquire (Amiotte 2018). The regalia became part of the trade network in the global economy and offered crucial income and agency for Lakȟótas, whose economy was largely crippled by the US-imposed move to reservation structure, decreases in rations, and insistence that men farm nonarable land. This economic adaptability reinforced Lakȟóta survivance.

4.2. Visibility

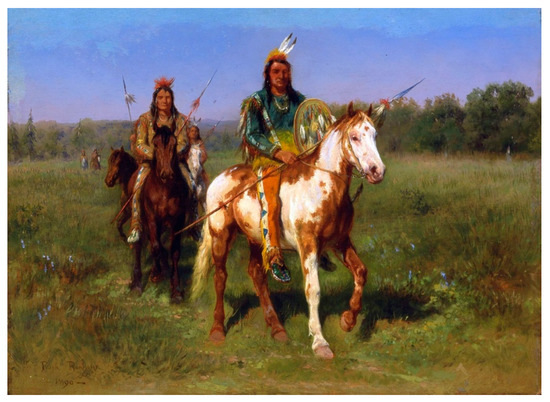

Bonheur and Hamman both reproduced the regalia in their artistic projects. While they introduced new meanings, the public circulation of their representations inadvertently extended the goals of their Lakȟóta makers and wearers. Bonheur made paintings imagining the American West, using sketches (including Figure 11) to make oil paintings, such as Mounted Indians Carrying Spears (Figure 19) (Burns 2018b, pp. 61–77). She constructs some new narratives in her depictions of the regalia. The beads become flattened into abstract planes of color. She adds a feathered shield copied from Catlin’s North American Indian12. Departing from her sketch (Figure 11), she reverses the warrior shirt to reveal the thunderbird from the back. The feathers and hairlocks wave behind the arms in her translation, rather than in the front of the jacket as in its original context. She also removes the flags, perhaps erasing what she interpreted as a signifier of patriotism and a marker of modernity by signaling the nation-state.

Figure 19.

Rosa Bonheur, Mounted Indians Carrying Spears, 1890, oil on board, Whitney Gallery of Western Art, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Partial Bequest of Vernon R. Drwenski and Museum Purchase, 8.046. Used by permission of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, WY.

But in the mobility of the figures, their self-assuredness in the landscape, and her reproduction of the beaded regalia within her painting, Bonheur perhaps unwittingly extends the discourse of the public assertion of Lakȟóta culture that the beaded regalia itself made in France when worn by the performers13. Her paintings were exhibited in London and at Georges Petit Gallery in Paris in 1897, this oil possibly among them (Burns 2018b, p. 67). As with photographs and postcards depicting Buffalo Bill’s Wild West performers wearing the distinctive marker of beaded regalia, the visibility of Lakȟóta culture is retained in this mitigated form. This public display of Lakȟóta art expands in these international viewing spaces. While the regalia remained in Bonheur’s studio, where it is still on display today, French and US visitors had frequented Bonheur’s atelier to meet the artist and see her menagerie of animals since the late 1850s (Dorr 1859). This semi-public reception space extends the accessibility and the visibility of the regalia.

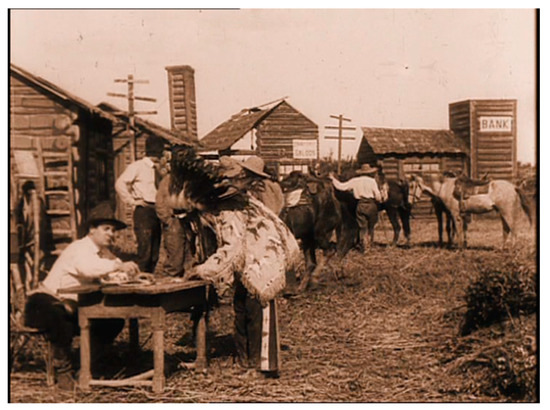

Hamman wore Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká’s regalia as a costume when he played the lead in Prairie en Feu, or “Prairie on Fire,” directed by Jean Durand and released in 1912 (Figure 20) (Burns 2018b, pp. 43–45). The film creates an imaginary Sioux Falls, South Dakota in the sandy Camargue, a marshy region in the south of France, as a settler village boasting log cabins, a saloon, a bank, and an encampment of Indians with campfires and painted tipis. Yellow Fox, a Lakȟóta “chief” played by Hamman, is cheated on his rations by the district farmer, Mr. Brooks. When he protests, Brooks shoots at him and the bullet grazes his hand. Yellow Fox retaliates by plotting with his community to set the village and fields on fire. Much of the thirteen-minute film is devoted to the racing horses of the red-face Indian actors and the villagers, who escape and murder the rest of his community. Rather than be killed or assimilated by settlers, Yellow Fox removes his war bonnet and beaded jacket, throws his hands up into the air in desperation amid the smoke, and self-immolates.

Figure 20.

Jean Durand, Still from Gaumont Cinema, Prairie en Feu, 1912. Photograph taken by the author.

Though it spectacularizes its subject and makes similar presumptions about the “vanishing race” that frame Buffalo Bill’s Wild West (Dippie 1982), Prairie en feu encourages viewers to engage with fraught Lakȟóta -US politics in emphasizing the contemporaneous construction of a reservation system, allotments, and boss farmers. This system of oppression was lived experience for Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká, who was mentioned in a newspaper article about the delivery of meat rations in 1891 (Troops and Indians 1891, p. 3). The conclusion warns about the risk to Lakȟóta culture signified by the relinquished regalia; this argument directly articulates period perceptions of regalia as statements of Lakȟóta cultural identity challenged by US assimilation policy. In the film’s use of Itȟúŋkasan Glešká’s regalia and attempts to transport the viewer to the geographic reorganization of Lakȟóta communities, the beadwork reasserts Lakȟóta culture as the film publicizes the garment’s circulation abroad. This dissemination furthers the intentions of the regalia’s Lakȟóta makers to produce circulating statements of Lakȟóta culture. The mobility of Itȟúŋkasaŋ Glešká’s regalia exceeds that of Bonheur’s painting in oil which would have been viewed in more private contexts; in this popularly shown film, Lakȟóta art circulates endlessly, not only for French viewers, but also for US viewers when the film traveled there (Anonymous 1912a, 1912b).

In these French contexts, new meanings resulting from appropriation do not automatically disqualify the regalia’s earlier statements of Lakȟóta survivance. The adaptability of these objects, enabled by their makers’ emphasis on visibility, characterizes their survivance. The regalia is unique among many Native American art objects, which often function within religious, ceremonial contexts meant for initiated members of the community alone. This beaded regalia, however, expands its statements of survivance because it was intended for public viewing and circulation in the non-Native world. As Greci Green argues, “the Lakota learned how to frame the public showing of their culture so that it would not be shut down completely” (Greci Green 2001, p. 129). There is continuity between that goal and the perpetuated circulation of the regalia in these new forms. While subsequent owners repurposed the objects and recontextualized them within their own cultural discourses, these new meanings did not contradict the original makers’ goals of publicizing Lakȟóta culture.

5. Conclusions

In “Geographies of Modernism,” Andreas Huyssen calls for scholars to analyze “the uneven flows of translation, transmission and appropriation” (Huyssen 2007, p. 194). Beaded regalia built a unique set of cultural signifiers that were intertwined with Lakȟóta beliefs and politics. In the context of enforced reservation structures, it underscores Lakȟótas’ use of culture to articulate survivance and to insist on sovereignty through art production. Its circulation abroad builds a Lakȟóta cosmopolitanism that belies the presumptions furthered in popular imagery, such as in Le Petit Journal cover (Figure 15). Both rooted in its making in the Lakȟóta community in the midst of political and social oppression and circulating through the mobility of Lakȟóta performers, the objects evince Lakȟóta survivance. Its material—beads, sinew, buckskin—and colorful designs bear traces of its intended circulation and visibility in a performance context and, further, subtly, in non-Native visual culture. In its various contexts, the regalia disrupts the presumption held by “manifest manners” that Lakȟóta culture was in decline.

Funding

This research was funded by support from Auburn University; the Buffalo Bill Center of the West; the New England Regional Fellowship Consortium Grant; the Terra Foundation for American Art; the Smithsonian Museum of American Art; Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art; and the University of Nottingham.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to special issue editors Sascha Scott and Amy Lonetree and three anonymous peer reviewers for their productive feedback on this article. In addition to feedback on this material after lectures delivered at University of California-Los Angeles, Virginia Polytechnique Institute, Georgia State University, the University of Oklahoma, and the University of Nottingham, I also had helpful dialogues with Arthur Amiotte, Tawa Ducheneaux, Kathryn Floyd, Steve Friesen, Mishuana Goeman, Toby Herbst, Saloni Mathur, Stella Nair, Hunter Old Elk, and Emily Voelker that have productively shaped this analysis. I also thank Macie Ma for shepherding this manuscript through the review and publication process and Auburn University research assistant Avery Agostinelli for research support.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Amiotte, Arthur. 2007. A New and Different Life on a Small Part of a Very Old Place: Traditional Arts in the Early Reservation Period in the Dakotas, 1870–1920. In Memory and Vision: Arts, Cultures, and Lives of Plains Indian People. Edited by Emma I. Hansen. Cody: Buffalo Bill Historical Center, pp. 246–51. [Google Scholar]

- Amiotte, Arthur. 2018. Interview with the author. September 13. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 1912a. At the Picture Shows. Daily East Oregonian, June 20, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 1912b. Review of Sales Company Films. New York Dramatic Mirror, April 17, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Bad Hand, Howard. 1993. The American Flag in Lakota Tradition. In The Flag in American Indian Art. Edited by Toby Herbst and Joel Kopp. Cooperstown: New York State Historical Association, pp. 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Berlo, Janet Catherine. 1996. Plains Indian Drawings 1865–1935: Pages from a Visual History. New York: Harry N. Abrams. [Google Scholar]

- Berlo, Janet Catherine, and Arthur Amiotte. 2016. Generosity, Trade and Reciprocity among the Lakota: Three Moments in Time. In Plains Indian Art of the Early Reservation Era: The Donald Danforth Jr. Collection at the Saint Louis Art Museum. Edited by Jill Ahlberg Yohe. St. Louis: St. Louis Art Museum, pp. 32–72. [Google Scholar]

- Berlo, Janet Catherine, and Ruth B. Phillips. 2019. ‘Encircles Everything’: A Transformative History of Native Women’s Arts. In Hearts of our People: Native Women Artists. Edited by Jill Ahlberg Yohe and Teri Greeves. Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Art, pp. 43–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bol, Marsha Clift. 1985. Lakota Women’s Artistic Strategies in Support of the Social System. American Indian Culture and Research Journal 9: 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bol, Marsha Clift. 1989. Gender in Art: A Comparison of Lakota Men’s and Women’s Art, 1820–1920. Ph.D. dissertation, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bol, Marsha Clift. 1993. Lakota Beaded Costumes of the Early Reservation Era. In Arts of Africa, Oceania and the Americas: Selected Readings. Edited by Janet Catherine Berlo and Lee Ann Wilson. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, pp. 363–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bol, Marsha Clift. 1999. Defining Lakota Tourist Art, 1880–915. In Unpacking Culture: Art and Commodity in Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds. Edited by Ruth B. Phillips and Christopher Steiner. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 214–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bol, Marsha Clift. 2018. The Art and Tradition of Beadwork. Layton: Gibbs Smith. [Google Scholar]

- Brasser, Ted J. 2000. Plains. In Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Edited by Gilbert T. Vincent. Cooperstown: Fenimore Art Museum, pp. 103–85. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Emily C. 2018a. Art, Ethnography and Politics: The Transnational Context of Bierstadt’s The Last of the Buffalo in Paris. In Albert Bierstadt: Witness to a Changing West. Edited by Peter H. Hassrick. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, pp. 123–150. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Emily C. 2018b. Transnational Frontiers: The American West in France. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cabau, Agathe. 2014. l’Iconographie Amérindienne Aux Salons Parisiens et Expositions Universelles Françaises (1781–1914). Ph.D. dissertation, Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Erik. 1988. Authenticity and Commoditization in Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 15: 371–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohodas, Marvin. 1997. Basket Weavers for the California Curio Trade: Elizabeth and Louise Hickox. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Conn, Dick. 1960. Western Sioux Beadwork. American Indian Hobbyist 6: 113–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dallin, Cyrus E. n.d. The Spirit of Life. Typescript, Cyrus E. Dallin Papers. Arlington: Robbins Memorial Library.

- Deloria, Vine, Jr. 1981. The Indians. In Buffalo Bill and the Wild West. Brooklyn: Brooklyn Museum, pp. 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Dippie, Brian W. 1982. The Vanishing American: White Attitudes and U.S. Indian Policy. Middleton: Wesleyan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dooling, Dorothea M., ed. 1984. The Sons of the Wind: The Sacred Stories of the Lakota. New York: Parabola. [Google Scholar]

- Dorr, Sarah A. Hayward. 1859. Diary Entry, February 4, 1859, John H. Hayward Family Papers. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, Daniel. 1993. Indianism in France. European Review of Native American Studies 7: 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Estes, Nick. 2019. Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Ewers, John C. 1965. The Emergence of the Plains Indian as the Symbol of the North American Indian. In Smithsonian Institution, Annual Report, 1964. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, pp. 531–44. [Google Scholar]

- Explication de Nos Gravures: Les Peaux Rouges et le Phònographe; 1913, Le Petit Journal, May 25, 162.

- Fabian, Johannes. 1983. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feest, Christian F., ed. 1999. Indians and Europe: An Interdisciplinary Collection of Essays. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feltz, Clyde. 1957. Old Time Sioux Costume. American Indian Hobbyist 4: 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, Maximilian C. 2010. Indigenous Cosmopolitans: Transnational and Transcultural Indigeneity in the Twenty-First Century. New York: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Friesen, Steve. 2017. Lakota Performers in Europe: Their Culture and the Artifacts They Left Behind. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon, Guy. 2003. The Sioux: The Dakota and Lakota Nations. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Greci Green, Adriana. 2001. Performances and Celebrations: Displaying Lakota Identity, 1880–1915. Ph.D. dissertation, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, Jerome A. 1970. The Sioux Land Commission of 1889: Prelude to Wounded Knee. South Dakota History 1: 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hamman, Joë. 1973. La réserve des Sioux de Pine Ridge en 1904. Western Revue 14: 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Emma I. 2007. Memory and Vision: Arts, Cultures, and Lives of Plains Indian Peoples. Cody: Buffalo Bill Historical Center. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Emma I. 2018. Plains Indians Buffalo Cultures: Art from the Paul Dyck Collection. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harney, Elizabeth, and Ruth B. Phillips, eds. 2018. Mapping Modernisms: Art, Indigeneity, Colonialism. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hassrick, Royal B. 1964. The Sioux: Life and Customs of a Warrior Society. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Herbst, Toby, and Joel Kopp, eds. 1993. The Flag in American Indian Art. Cooperstown: New York State Historical Association. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover, Herbert T. 1989. The Sioux Agreement and its Aftermath. South Dakota History 19: 59–84. [Google Scholar]

- Horse Capture, Joe. 2016. Men’s Clothing. In Plains Indian Art of the Early Reservation Era: The Donald Danforth Jr. Collection at the Saint Louis Art Museum. Edited by Jill Ahlberg Yohe. St. Louis: St. Louis Art Museum, pp. 140–42. [Google Scholar]

- Horse Capture, Joseph D., and George P. Horse Capture. 2001. Beauty, Honor and Tradition: The Legacy of Plains Indian Shirts. Washington, DC: National Museum of the American Indian. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, Jessica L. 2016. Ojibwa ‘Tableaux Vivants’: George Catlin, Robert Houle and Transcultural Materialism. Art History 39: 124–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyssen, Andreas. 2007. Geographies of Modernism in a Globalizing World. New German Critique 100 34: 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasson, Joy. 2000. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West: Celebrity, Memory, and Popular History. New York: Hill and Wang. [Google Scholar]

- Klumpke, Anna. 1997. Rosa Bonheur: The Artist’s (Auto)biography. Translated and Edited by Gretchen van Slyke. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, Ronald P. 1977. Dress Clothing of the Plains Indians. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lubbers, Klaus. 1994. Strategies of Appropriating the West: The Evidence of Indian Peace Medals. American Art 8: 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyford, Carrie A. 1979. Quill and Beadwork of the Western Sioux. Boulder: Johnson Books. [Google Scholar]

- Maddra, Sam. 2006. Hostiles? The Lakota Ghost Dance and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- McNenly, Linda Scarangella. 2012. Native Performers in Wild West Shows: From Buffalo Bill to Euro Disney. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Leroy N. 2001. In Search of Native American Aesthetics. Journal of Aesthetic Education 25: 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Carter Jones, and Diana Royer, eds. 2001. Selling the Indian: Commercializing and Appropriating American Indian Cultures. Tuscon: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moses, L.G. 1996. Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883–1933. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Napier, Rita G. 1999. Across the Big Water: American Indians’ Perceptions of Europe and Europeans, 1887–1906. In Indians and Europe, An Interdisciplinary Collection of Essays. Edited by Christian F. Feest. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, pp. 383–401. [Google Scholar]

- Nos Gravures: La révolte des derniers Peaux-Rouges. 1890, Le Petit Journal, December 13, 8.

- Orchard, William C. 1975. Beads and Beadwork of the American Indians. New York: Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation. First published 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Ostler, Jeffrey. 2004. The Plains Sioux and U.S. Colonialism from Lewis and Clark to Wounded Knee. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peace Jubilee: Chippewa and Sioux Indians. 1896, Ashlant Daily Press, September 12, 1.

- Pearlstone, Zena. 2001. Katsina: Commodified and Appropriated Images of Hopi Supernaturals. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History. [Google Scholar]

- Peers, Laura. 2007. Playing Ourselves: Interpreting Native Histories at Historic Reconstructions. Lanham: AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Penney, David W. 1992. Art of the American Indian Frontier: The Chandler-Pohrt Collection. Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Ruth B. 1998. Trading Identities: The Souvenir in Native North American Art from the Northeast, 1700–1900. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Ruth B., and Christopher B. Steiner, eds. 1999. Art, Authenticity and the Baggage of Cultural Encounter. In Unpacking Culture: Art and Commodity in Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pohrt, Richard A. 1975. The American Indian, the American Flag. Flint: Flint Institute of Arts. [Google Scholar]

- “Poor Lo in Diamonds: Buffalo Bill’s Braves Return from Europe in Foppish Array.”. 1890, Chicago Daily Tribune, November 18, 1.

- Posthumus, David C. 2018. All My Relatives: Exploring Lakota Ontology, Belief and Ritual. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, Father Peter. 1977. Beauty for New Life: An Introduction to Cheyenne and Lakota Sacred Art. In The Native American Heritage: A Survey of North American Indian Art. Edited by Evan Maclyn Maurer. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, pp. 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Power, Susan. 2019. Nellie Two Bears Gates: Chronicling History through Beadwork. In Hearts of our People: Native Women Artists. Edited by Jill Ahlberg Yohe and Teri Greeves. Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Art, p. 193. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, William K. 1994. Innovation in Lakota Powwow Costumes. American Indian Art Magazine 19: 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, William K. 1996. The American Flag in Lakota Art: An Ecology of Signs. Whispering Wind 28: 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rickard, Jolene. 2011. Visualizing Sovereignty in the Time of Biometric Sensors. South Atlantic Quarterly 110: 465–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydell, Robert, and Rob Kroes. 2005. Buffalo Bill in Bologna: The Americanization of the World, 1869–1922. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmittou, Douglas, and Michael H. Logan. 2002. Fluidity of Meaning: Flag Imagery in Plains Indian Art. American Indian Quarterly 26: 559–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Mary Jane. 1983. Women’s Work: An Examination of Women’s Roles in Plains Indian Arts and Crafts. In The Hidden Half: Studies of Plains Indian Women. Edited by Patricia Albers and Beatrice Medicine. Washington, DC: University Press of America, pp. 101–21. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, William H. 2011. The Jardin d’Acclimatation, Zoos and Naturalization. In Human Zoos: The Invention of the Savage. Paris: Musée du Quai Branly, pp. 130–44. [Google Scholar]

- Standing Bear, Luther. 1928. My People the Sioux. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Tissandier, Gaston. 1889. Les Peaux-Rouges et les américans de frontière, à Paris. La Nature, Revue des Sciences et de Leurs Applications Aux Arts et à L’Industrie 6: 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Tone-Pah-Hote, Jenny. 2019. Crafting and Indigenous Nation: Kiowa Expressive Culture in the Progressive Era. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Torrence, Gaylord. 2014. The Plains Indians: Artists of the Earth and Sky. Paris: Musée du Quai Branly. [Google Scholar]

- Troops and Indians. 1891, Evening Star (Washington, DC), January 29, 3.

- Utley, Robert M. 2004. The Last Days of the Sioux Nation, 2nd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Venture, Remi, and Frédéric Jacques Temple, eds. 2010. Car mon Coeur et Rouge: Des Indiens en Camargue/Folco de Baroncelli. Marseille: Editions Gaussen. [Google Scholar]

- Vizenor, Gerald. 1994. Manifest Manners: Postindian Warriors of Survivance. Hanover: Wesleyan University Press of New England. [Google Scholar]

- Vizenor, Gerald. 1998. Fugitive Poses: Native American Indian Scenes of Absence and Presence. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vizenor, Gerald. 2008. Aesthetics of Survivance: Literary Theory and Practice. In Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence. Edited by Gerald Vizenor. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Vuillard, Éric. 2016. Sorrow of the Earth: Buffalo Bill, Sitting Bull and the Tragedy of Show Business. Translated by Ann Jefferson. London: Pushkin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, Louis S. 2005. Buffalo Bill’s America: William Cody and the Wild West Show. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, Jace. 2014. The Red Atlantic: American Indigenes and the Making of the Modern World, 1000–1927. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wernitznig, Dagmar. 2007. Europe’s Indians, Indians in Europe: European Perceptions and Appropriations of Native American Cultures from Pocahontas to the Present. Lanham: University Press of America. [Google Scholar]

- Wissler, Clark. 1904. Decorative Art of the Sioux Indians. Museum of Natural History Bulletin 18: 231–78. [Google Scholar]

- Wissler, Clark. 1915. Costumes of the Plains Indians. Anthropological Papers (American Museum of Natural History) 17: 45–100. [Google Scholar]

- Yohe, Jill Ahlberg, and Beth Harris. 2018. Nellie Two Bears Gates, Suitcase. Smarthistory. December 18. Available online: https://smarthistory.org/two-bear-gates-suitcase/ (accessed on 13 August 2019).

| 1 | Most of the performers in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West came from the Lakȟóta nation, though they occassionally acted or figured in postcard imagery as members of other tribal nations (Friesen 2017; Moses 1996, p. 170; McNenly 2012, p. 41). Performer records at the William F. Cody Papers, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, WY list a group of Pawnee performers in 1885. The program for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in London in 1887 lists Shoshone, Cheyenne, and Arapaho individuals, but these are assigned identities for the mostly Lakȟóta performers in the international venue. As Luther Matȟó Nážiŋ (Luther Standing Bear, 1868–1939) recalled about performing in London in the 1902–03 tour, “While all the Indians belonged to the Sioux tribe, we were supposed to represent four different tribes, each tribe to ride animals of one color” (Standing Bear 1928, p. 252). |