Abstract

How might we understand the art—and perhaps something of the life—of Kiowa/Caddo artist T.C. Cannon by centering his engagement with music and in particular with a meditation on Cannon’s 000-18 Martin guitar, which greeted visitors to the landmark exhibition, T.C. Cannon: At the Edge of America? In the form of a personal reflective essay, T.C. Cannon’s Guitar contemplates my own history with similar guitars, songs from the folk-songwriter tradition, and questions of multi-media crossings—art, music, text, object—that demonstrate revealing stylistic affinities. The essay explores intergenerational relations between myself, Cannon, and my father Vine Deloria, Jr., the three of us evenly spaced over the course of the late twentieth century, and it does so in an effort to understand something about the historical impulses of the period between 1965 and 1978. In that moment—accessible to me through memories of affects more than memories of actions—Native politics and art were both figuring out ways to honor the past while making it new, creating distinctive forms that we can recognize around concepts such as survivance, sovereignty, and indigenous modernism.

The Peabody Essex Museum’s 2018 show T.C. Cannon: At the Edge of America staged a brilliant entrance, funneling visitors around a sharp corner and into the presence of six simultaneously perceptible objects of contemplation—paintings, lyrics, music, and material culture. On the most immediate wall was Cannon’s breathtaking, stake-in-the-ground, 1966 painting, Mama and Papa Have the Going Home Shiprock Blues. On a far wall to the right sat a late work (Cannon died in 1978), the Fauvist color spectacle Two Guns Arikara (1974–77), which had been framed as emblematic of the entire show (you’ll find it prominently—and rightly—featured in the giftshop’s notebooks and posters). In purple, lavender, green, blue, and red patterns and forms, it literally leapt off the wall. Tucked on a short wall midway between the two paintings was It’s Alright Ma, I’m Only Sighing (1966), a modernist portrait of Bob Dylan, replete with lettered and stenciled signifiers: Hohner (Dylan’s harmonica), Freewheel and Another Si (the albums Freewheeling Bob Dylan and Another Side of Bob Dylan), What’s with Zimmerman (a reference to Dylan’s name), among others, a reminder of the days Cannon spent in the studio blasting Dylan at a high volume.

Those were the visual texts, framing Cannon’s breakthroughs, his mature style, and his love for acoustic music and the 1960s folk tradition. For the viewer newly exploring Cannon and modern indigenous arts, the Dylan portrait might have seemed slightly off-key for a Native artist working Native imagery across various stylistic registers. Such was not the case, however. Tune your ear, and you were treated to a recording of Cannon singing an original song, Mama and Papa Got the Shiprock Blues, a musical companion to the painted work, the lyrics on the wall nearby offering a literary text that promised an introduction to the poetry and writing yet to come. In the song, Dylan mattered, stylistically. He morphed into Cannon, who morphed into Woody Guthrie, who morphed into an out-west Indian vision of the Greenwich Village folk scene, which in turn morphed into the painting on the wall:

Viewers were asked to enter the synesthetic: to observe the paintings, listen to the music, study the lyrics, draw a stylistic, historical, affective line between Cannon and Dylan, and contemplate a rich artistic career, all in an overlapping series of crystalline and complex multi-sensory moments.Mama, stay away from Gallup please‘cause when you see that greyhound comin’ cross the sandYou know it’s bound to be your manHeat the skillet put on some mutton stewOh mama, papa’s got the blues againOh mama, papa’s got the shiprock blues againKramer (2018)

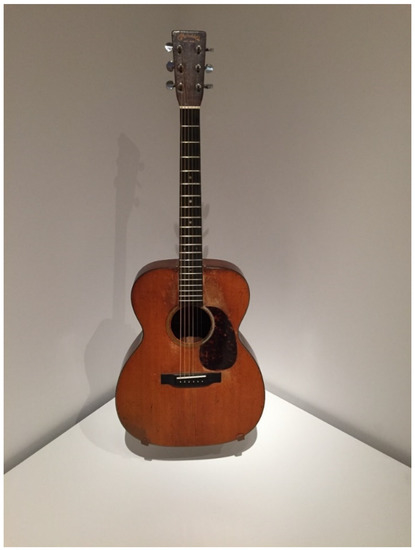

But what really made the space transcendent was the sixth object: T.C. Cannon’s guitar, perched on a stand in the corner (Figure 1). Simultaneously visual, aural, and material, the guitar (a seemingly incidental curiosity in the context of the exhibit) was in fact the master key, the singular text that made the section, and thus the exhibit, into a complex holism. That unifying sensibility—inputs from everywhere producing art that spoke to everything—captured the essence of the indigenous modernism given full, if brief, flower in Cannon’s work. Indeed, such a holistic, relational and incorporative way of thinking is central to indigenous worldviews. Cannon’s painting placed such ways of thinking, seeing, and being in dialogue with both the experience of modernity—as a material condition—and with modernisms—dominant aesthetic expressions often inclined to either take indigenous expression as “primitive” or to ignore it altogether. The resulting work exemplified a new and stunning aesthetic, a distinctly Native kind of modernism.

Figure 1.

T.C. Cannon’s 000-18 Martin Guitar, as displayed at PEM, T.C. Cannon: At the Edge of America. Photograph by Philip J. Deloria.

T.C. Cannon’s C.F. Martin guitar has had some hard use, as evidenced by the wear patterns. Varnish has been displaced southwest of the sound hole, where fingerpickers rested their thumbs thousands of times over the years. Above the sound hole and around the rim, you find scrapes and scratches from over-enthusiastic players with flatpicks. The headstock is dented and grooved from those inevitable moments when you turn too suddenly and bash into something. The spruce top has aged and weathered into a mellow woodiness, and the mahogany back and sides are a rich nutty brown. Amidst the glory of Cannon’s art, the guitar was among the most beautiful objects present in the room.

Cannon was born in 1946, 13 years after my father, Native American activist and intellectual Vine Deloria Jr. I was born in 1959, 13 years after T.C. Cannon. He sits exactly one-half generation between us, so Cannon’s glory years were those of both my father’s mature thinking and my own coming of age. The two were not contemporaries; nor were Cannon and me. But call each of us a half-contemporary of the other, perhaps capable of imagining the world of people thirteen years ahead or behind us, grasping understandings we could not quite muster in relation to parents or children. If I could dimly capture T.C. Cannon’s 1960s and 1970s, perhaps I could catch a glimpse of my father’s world. And if my dad had looked generationally forward at Cannon, perhaps he might have seen something of mine. T.C. Cannon occupies an eerie place in a shared generational world that unites the politics and aesthetics of a particular historical moment. The guitar sits at the center of it.

In 1977, as Cannon was painting what no one anticipated would be some of his last pieces, I drove up to Boulder from Golden, Colorado, with $500 I had earned doing paper routes and mowing lawns, to a funky guitar shop off Pearl Street, and bought a 1971 Martin D-28 guitar. It’s my best and favorite guitar to this day, a big booming “dreadnought” guitar built to try to keep up, volume-wise, with banjos and fiddles (a noble, but hopeless task). I was a kid, $500 seemed like a really good deal on a Martin at that time, and my friends were playing fiberglass-back Ovations and chuffy gut-stringed folk guitars. For Cannon, and for myself, the Martin was it, the very best you could do. I did not know it, but there was a reason for the bargain price. The music booms of the 1960s strained the capacity of the Martin factory (which, to this day, is a mix of industrial, craft, and hand production, one of the reasons Martins are such excellent guitars). The luthiers at Martin placed the bridge on some of their early 70s guitars about 1/8 of an inch off, making the instruments uneven in their tuning across the neck. That was my guitar (a few years later, it took about $1000 to fix—but the repair produced a really wonderful instrument) (Johnston et al. 2008, 2009).

T.C. Cannon’s Martin was a 000-18. It was made in 1940, and so is part of an entire guitar folklore concerning “the pre-war Martins”. Rosewood guitars (like my D-28) were made at that time with rare Brazilian rosewood from some of the last stands of great guitar wood. Cannon’s guitar is mahogany—but it too is excellent old wood, with a rosewood fretboard. Guitar aficionados will wax endlessly about the ways that the bindings and the glues and the interior bracing and joint supports on these guitars bonded together over time, functioning as if a single unified piece of deliciously resonating wood. In the late 1970s, I worked at Ferretta Music, a folky guitar store in a funky part of Denver, where we had, at one time, three pre-war Martins on the wall, each priced at over $3000. Today, a 000-18 from 1940 might cost nearly $13,000. Cannon got his, I’m told, from his landlord, who had accompanied it through some part of its hard life. Despite its seeming misadventures, it is an excellent guitar and it must have set him back something, even then.

Cannon’s 000-18 is even across its full range. The bass is thick and surprisingly powerful, and the treble is shiny and bright, with no trace of watery thinness; the mid-range is sweet and strong. It’s got an excellent feel—it’s been grooved by other fingers and these have bequeathed a kind of auratic power, something like the art Cannon left behind. The 000 series is a smaller guitar, with a more pronounced waist, which emphasizes the gendered aesthetic of the instrument: its humanized form is female. And the guitar is a sexualized instrument, of course. You don’t need Elvis Presley (who had a 000-18 early in his career) to know that. The steely rationalized grid of the guitar’s neck—tuners, frets, strings—is all about controlling sound with precision: raise and lower the pitch by changing the thickness of the string, its tension, and its length. The organic form of the body—curves, sound hole, shoulders—is about producing sound through vibration and resonance.

Combine head, neck, and body and you have music—in ways that demand further contemplation. On the one hand, the guitar gives us metaphors of control, domination, perhaps even gendered violence (and indeed Cannon’s writings contain uncomfortable passages and dated language that can give one pause in this regard). On the other, the guitar has long been associated with mutuality, romantic love and longing. These aspects also appear in Cannon’s work, which is sometimes tinged with regret or colored by curiosity, sometimes painted in the frank terms of lust.

It’s not just that Cannon made music. It is that the experience of making music—and making it on a guitar—put him in a particular kind of aesthetic place. Cannon’s studio was not just a jam of paint and canvas; it was also a place of music, instruments, tape recorders, late-night sessions, the occasional mind-altering substance. The guitar, in this sense, is not simply a fusion of organic sound and rational control; it’s the occasion for the creation of bonds between people. And so, the social domination-love-lust of the guitar—sitting there in Cannon’s studio, beckoning him—resonates across images like Favorite Wife (1972) or Mona Lisa Must’ve Had the Highway Blues (1973) or Dutch Girl (Margot) (1975). When Cannon painted an odalisque with heart in hand, the guitar beckons. When Cannon chose to show the ink color sequences in his woodcuts, the guitar echoes. It’s always lurking there somewhere.

We divide time by decade, even though we know it is a poor conceit. Cannon’s career (and arguably that of my father) suggests the shared cultural (in)coherence, not of “the 60s” or “the 70s,” but of a moment from 1965 or so, through 1978, more or less. The Kiowa/Comanche guitarist Jesse Ed Davis was screaming the solo on Jackson Browne’s Doctor My Eyes and playing with a who’s who of rock and roll heroes. On the FM band, deep-voiced, slow-talking DJs were playing Kaw jazzman Jim Pepper’s luminous Witchi Tai To. As T.C. Cannon is blasting music through his studio while he creates some of his finest work, my father is playing not-mix cassette tapes in his office, while he finishes the five-year burst (1969–1974) that produced seven books, four of them monumental, and a raft of articles and chapters. The tapes are custom-made by him, and they repeat a favorite song over and over again for 45 min. My bedroom is beneath his office, and I hear him singing along, as he bashes the keys of his IBM Selectric. Mostly it is the music of his childhood, but there are songs that intrude from the present, including Dylan’s Like a Rolling Stone. As with Cannon’s workspace, the office doubles as a kind of music studio. The two of them were doing something quite similar: music, politics, cultural production, singing along to a meaningful, connected soundtrack. And of course, I was struggling to get my own fingers lined up on the frets and contemplating the Martin guitar that might be waiting for me.

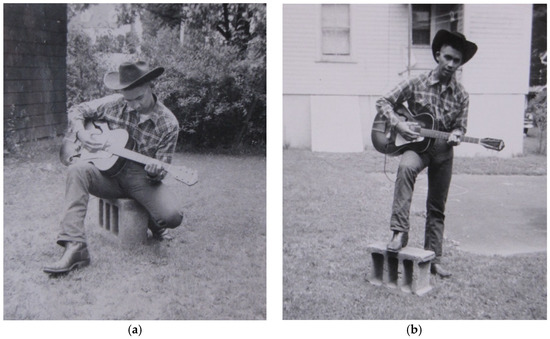

Go back a few years: Cannon is maybe five years old; my dad is 18, and he too has gotten hold of a guitar, learned a few chords, and strolled out into the backyard with a camera, looking to imagine himself, not (yet) as Bob Dylan, but maybe as Gene Autry or Webb Pierce (Figure 2). It looks inexpensive, a western swing instrument with f-holes, perhaps an arch-top electric (is that a pickup under the strings and a cable dangling down?). It’s not clear that my dad is actually playing anything. Perhaps he’s doing a kind of E boogie shuffle pattern as he sits on his cinder block, happy in his hat, boots, and snap shirt? Or standing there with a C-form E7 chord mid-neck? Or am I just being charitable?

Figure 2.

Vine Deloria Jr., posing with guitar, early 1950s. (a) Is he playing an E boogie shuffle? (b) Is he playing a C-form E7 chord? Author’s collection.

It was 1973 when my father revealed his secret guitar fetish to me. Signed up for middle-school guitar class, but without a guitar, I was eager but unable to start making music. After the missed baseball games and concerts (I do not begrudge him this; he had important work of his own), my dad showed up big, walking in dramatically as the first class began and presenting me with a new Harmony guitar, chipboard case with red lining, bright wood, steel strings. Later, we would spend one of our very best days together, haunting the pawnshops of Denver’s South Broadway area, and acquiring a 1959 Sears Silvertone amp, recovered in trendy black Naugahyde, to accompany my first electric guitar, the younger twin of that arch-top f-hole guitar my dad had clutched that day on the cinder blocks.

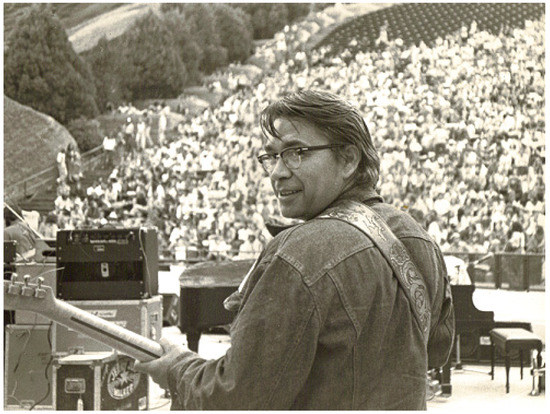

My father’s finest musical moment will come in 1976, as Cannon was painting political pieces like Washington Landscape with Peace Medal Indian or his massive mural, Epochs in Plains History: Mother Earth, Father Sun, The Children Themselves. Through a series of friendships and circumstances, we find ourselves backstage at a Jerry Jeff Walker show at Colorado’s Red Rocks Amphitheater. Half goaded, half encouraged by Walker sideman Gary P. Nunn, my father slips out onstage, dons Jerry Jeff’s Telecaster and grins back over his shoulder, the crowd stacking up behind him (Figure 3). He is reliving his teenage guitar fantasy, and it is not crazy to think that such moments (he hung out with a lot of musicians in the mid-1970s) helped power a change in his own writing, away from his previous political works into his hardest and most complicated book, The Metaphysics of Modern Existence, published in 1979.

Figure 3.

Vine Deloria, Jr. at Red Rocks Amphitheater, Golden, Colorado, 1976. Photograph by Gary P. Nunn. Author’s collection.

Here were two creators working out arguments, politics, and music, but we should note that amidst their similarities, they seem to have moved in parallel when it came to visual arts. It’s hard not to recall now one particular moment when my father came home with a signed Fritz Scholder lithograph, nonchalantly rolled up and rubber-banded. It got thumbtacked on a wall for a while, then rolled up some more, then tossed in the basement, then consigned to the garage and then eventually just vanished. Meanwhile, we acquired Sioux pottery, an act of tribal loyalty and aesthetic tone-deafness, and an indication of just how far our family was from the happening art world of T.C. Cannon.1 A half-generation apart, and concerned with similar questions and processes, one might anticipate that Cannon and my father would have had many things to talk about. The latter’s track record of disengagement with visual arts, however, suggests otherwise—that their most significant point of connection might well have been that guitar.

Despite all the scratching around the sound hole of T.C. Cannon’s guitar, the 000-18 is not usually considered the instrument of aggressive flatpickers and big strummers (though one could argue that both Cannon and my father were big and bold players). It’s great for fingerpicking and has a slight hint of folk delicacy. In that sense, it demands a bit more subtlety and thought than the big dreadnoughts. There’s a style at work in the 000, as there is in all guitars. The instrument can be wielded with force and power, but only by exercising a certain brand of care. The 000 is the guitar of Ry Cooder and Norman Blake—and Woody Guthrie, whose sound permeates Cannon’s music, via Rambling Jack Elliot, Dylan, and other 60s folkies. Guthrie, it is worth remembering, was known to pummel his guitar, making it carry a sonic message to accompany his political claim, painted on the top of many of his instruments: “This Machine Kills Fascists”. Both Cannon and my father understood the continuities and overlaps in that kind of politics.

Guthrie, Elliot, and Dylan were troubadours of opposition, drawing on (and often speaking to) the “folk,” those situated at the social margins, bearing the hurts of powerlessness, and surviving, frequently with wit, humor, and intelligence. Rambling Jack Elliot was one of the musicians who passed through our house, and he modeled this critical survival aesthetic. We spent the better part of one night talking about Guthrie (mostly) and Dylan (a little), with the occasional guitar interlude. While we talked, Elliot’s dog was chewing a large hole in our screen door. The next morning, he stood staring at it as he prepared to depart, then paused, grinned, took off his cowboy shirt and handed it to my dad. “Sorry about that. Here’s what I’ve got”. And then he grabbed his guitar and headed down the road. How could you not love him?

Taken together, Guthrie, Elliot, and Dylan bridged the oppositional politics of the period between the 1930s and 1960s. But we can turn to Dylan, specifically, to help mark a shared critical moment of political and stylistic transformation in the mid-1960s. Cannon’s painting It’s Alright Ma, I’m Only Sighing (1966) takes its title from a line in Dylan’s “It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding) from 1965’s Bringing it All Back Home, the album said to mark Dylan’s turn from acoustic folk to electric music, and from straight-up political folk music to literary, surrealist lyrical exploration. Cannon’s landmark 1966 paintings It’s Alright Ma and Mama and Papa Have the Going Home Shiprock Blues mark a turn in his work as well, away from older Kiowa painting traditions and toward the new kinds of modernisms that he would explore over the next decade. As Dylan pivoted and Cannon joined him, so too did my father, serving as executive director of the National Congress of American Indians from 1964–1967, a reorientation that would culminate in his pathbreaking 1969 book, Custer Died for Your Sins. Here was the beginning of that incredible period—not a decade, but a shared half-generation of time—from about 1965 to 1978.

Cannon cared a lot about music. Like my father, he sensed that secret possibilities opened up when you invested in it, either as listener or performer. At the minimum, all of us were hoping to get a bit of joy from our guitars. But we were also intuiting a deep synesthetic, connective, relational power. Those guitars, we knew, would somehow make us better at painting and writing, and maybe other things besides. And so Cannon put music in dialogue with his art and was willing to invest in a guitar that took him straight back to Woody Guthrie and maybe something of his rural Oklahoma roots—and to Bob Dylan, who mostly owned Gibsons in the 1960s but who turned to Martin 00s and 000s in the 1970s.

Cannon seems also to have had that musician’s itch to turn on a tape recorder when friends were around jamming in the studio. But this is not simply a musician’s habit or an artist’s sketchbook; it’s also a Native thing—or at least it was in our house. My dad had a Sony reel-to-reel, which got pulled out and turned on when stories were being passed around. My grandfather almost always insisted on being recorded when he was telling Dakota stories or singing songs, and as a result, the world is surprisingly full of old tapes of him. Periodically, someone will be cleaning out an attic, find one, and send it to me.

This taping habit is what enables us to resurrect recordings of Cannon’s music. Just as the guitar itself comes to life when lifted from its coffin-like velvet case, so too does Cannon’s voice sing from the grave on those old tapes. It’s both art and artifact. Here is some noodling around with friends; there is a blues riff; here is a beautiful original song that begins with the spoken phrase, “This is for Susan Swartzberg”. That line immediately takes you somewhere quietly interesting in Cannon’s life, to which a sketch captioned Susan Swartzberg ___________!! (1975) offers hints. It shows a lovely woman, captured in the full glory of both eroticism and 1970s style, an arched eyebrow, short hair waving to echo the mountains in the background and a billowing patterned blouse, a breast blended subtly into the lines and swirls.

The guitar smiles knowingly from the tape. An ascending fingerpicked riff carries you back to the Western singer-songwriter translations of the 60s folk scene: it’s Colorado and New Mexico, mountains and streams and some picture of nature and love and art all together. That’s a style, too. Look at one of Cannon’s late self-portraits (Self Portrait in the Studio, 1975). There he is in the coolest cowboy clothes ever, neckerchief and hat and sunglasses, brushes in hand, perched in front of a big window that frames both the sound and appearance of that world completely. My dad and T.C. Cannon lived in that world; I apprehended it from a youthful distance and desired it, hoping to call it into being every time I pulled out my guitar and wished for some new love to materialize, or some sacred voice to speak from a mountain or a river. Cannon left behind an artist’s meditation on the self-portrait, upon which we might play:

Those were the 1970s, and Cannon did not simply live in them; he defined them, even as his painting both embodied and transcended them. And then, there was a car accident and he was gone.WonderingWhether to leave or stay a bit longerShould I stay the nightAnd paint the purple area out of that cornerOr maybe add some political ague to that dancer’s face?Wasn’t that a great river I saw this morning?I wish I knew someone important or holy to share it with. Maybe that transient ladywith green shoes from California? She is a niceAmerican, what with her great breasts and allKramer (2018, pp. 72–73)

I was fortunate to play T.C. Cannon’s guitar at the Peabody Essex, to appreciate the recent restoration work that has returned it to acoustic glory, to revel in the quality of the instrument, to try to capture, in a musical instant, the aura of Cannon’s moment. But which moment? Certainly, an artist’s New Mexico studio in the mid-70s, proximate to the 1960s but not of them, exactly. That’s not all, however. His paintings place you, alive and sentient, in 1940s Oklahoma, 1860s Minnesota, 1960s Santa Fe. Here’s Vietnam, fully engaged with the nineteenth-century Plains Wars, and there’s a Southern Plains powwow from just last week. Cannon’s indigenous modernism was multi-inspired, synesthetic, complicated. Even as it demanded a transcendence of the boundaries of sound, image, lyric, and object, so did it demand a large recognition of Native transcendence of all the categories that sought to capture Indian people, that demanded the familiar groveling performances, that corralled them on the reservations of primitivism or crude politics. Cannon’s guitar was hardly incidental; it was central and definitive. The guitar was both the critical emblem and the dynamic tool of Cannon’s transcendence.

The exhibit T.C. Cannon: At the Edge of America recognized this criticality coming and going. The show closed with the large mural, Epochs in Plains History: Mother Earth, Father Sun, The Children Themselves (1976–77), painted at the same moment my father was holding a guitar at Red Rocks and grinning sheepishly, a bit like Rambling Jack Elliot. It closes also with music—and with the same guitar that opened the exhibit. Choctaw artist Samantha Crain used Cannon’s guitar to record her own powerful song, One Who Stands in the Sun, which played in the gallery and was accompanied by a beautiful performance video. Crain’s song was crafted in dialogic response to Epochs in Plains History, connecting past, present and future in a stunning example of musical and narrative survivance—the unstable term Ojibwe critic Gerald Vizenor coined to describe an indigenous sense of “presence,” active and continuous over time through the telling of stories (and art and music) that recognize but refuse to wallow in tragedy, and which instead create life and power in the rejection of and resistance to domination (Vizenor 1999).

At the Peabody Essex, I listened to Cannon sing Susan Swartzberg’s song several times but did not quite catch it. What I did catch, more easily, was Cannon’s version of another song, a cover of Louise, written by now-mostly-anonymous Greenwich Village folkie Paul Siebel, and released in 1970. Louise was immediately covered by Linda Ronstadt, Leo Kottke, Bonnie Raitt and many others. It’s not an easy song. Here are bits of two verses:

And the conclusion:Well they all said Louise was not half badIt was written on the walls and window shadesAnd how she’d act the little girlA deceiver, don’t believe her that’s her trade …They’d always put her down below their kindStill some cried when she died this afternoonLouise rode home on the mail trainSomewhere to the south I heard it said …

Ah but the wind is blowing cold tonightSo good night Louise, good night

I started playing Louise in about 1978, the same year that T.C. Cannon died. It was around the moment when I had achieved a basic level of proficiency—I could get through a song pretty well. The question was, could I ever really get inside a song? It is the same question a visual or literary artist must confront: the difference between execution and inspiration, making it simple in order to make it complicated (or maybe vice versa). It is the gap in which something meaningful just might happen—something magical, spiritual, aesthetic—if you decide to paint the purple area out of the corner. There are moments when you can see those gaps in the distance, though it is not clear whether or not you can ever get there.

Holding Cannon’s guitar, and singing that song to honor him, marked such a moment. The song begins with a double entendre: “They all said Louise was not half bad”. In the instant, back in 1978 (and three decades later), when I first thought I might be able to close the gap, I realized this: if you smirked when you said that line … if you smirked even in your mind … even a little bit … If you went to the cheap sexual innuendo, you’d play it cheap, as a kind of honky-tonk song.

But if you flipped it—if you placed yourself in the position of thinking that Louise was more good than she was bad, that she was a person worthy of respect and memory—then you’d do the song (or write the poem or paint the painting) completely differently. You’d try your best to offer a transcendence that might bind together that which had been shattered, or shatter that which smirked and took its power for granted. You might find yourself singing—like Cannon and like my father—in an indigenous idiom of both pain and possibility.

Louise was a kind of survivance elegy, and when I put on the headphones and heard T.C. Cannon sing it, I realized that it was his elegy—a song for an artist who died too soon. Singing it to him, chording on his guitar, among his paintings: this was a practice of indigenous aesthetics, an elegy for everything that had ended too soon, and an assertion of all that was to come. It was in fact the simplest lesson: Cannon’s art was Native art, not because of its subject matter or the blood-quantum identity of its maker—though I suppose that these things mattered—but because it was. He loved Bob Dylan for Dylan, and he loved Louise, and maybe a woman named Susan Swartzberg, and certainly his guitar, and in the process indigenized the whole lot of it, churned it up, made it new, made it old, made it.

I’ve come to believe that a guitar takes on the qualities of its owners. Like a painting, it demands we grapple with the auratic power contained in wood grain and metal strings. There was once a near-perfect day on which my fingers touched the same fretboard, turned the same tuners, felt the same wood that T.C. Cannon’s hands had touched and felt. The canvases nearby were no different in their materiality (though the curators would not let me touch them). My Louise came out of the same sound hole that Cannon’s did; with no smirk, only a touch of sadness. The wind was blowing cold, and perhaps the answers were blowing in it too, blowing toward eternity and the critical moment, the gap, the flashing up of meaning at the instant of danger, the unanswered question. Contemplating exactly that, Cannon recorded—though not for the guitar, I’m guessing—what must be something of a last word:

Good night T.C. Cannon, good night.Enough of this poetic parody,I must turn my attention to the critical momentat hand. I’m glad I see rivers free, as opposed tothe view taken by scientists and swimmers.where are all the rivers at this time of night?

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Karen Kramer and Dan Monroe of the Peabody Essex Museum for inviting me to Salem to play T.C. Cannon’s guitar in May 2018, and to Ann Braude for companionship on the visit, and seriousness about the whole enterprise.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Johnston, Richard, Dick Boak, and Mike Longworth. 2008. Martin Guitars: A History. New York: Hal Leonard Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, Richard, Dick Boak, and Mike Longworth. 2009. Martin Guitars: A Technical Reference. New York: Hal Leonard Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, Karen, ed. 2018. T.C. Cannon: At the Edge of America. Salem: Peabody Essex Museum, pp. 54 (Mama and Papa lyrics), 56 (Mama and Papa), 137 (Two Guns Arikara), 106 (It’s Alright Ma, I’m Only Sighing). [Google Scholar]

- Vizenor, Gerald. 1999. Manifest Manners: Narratives on PostIndian Survivance. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, p. vii. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Lakota and Dakota people are known for brilliant aesthetic production: bead and quillwork, easel and hide painting, material culture. Pottery traditions would not necessarily rank at the top of that list; the craftspeople at Sioux Pottery have been creating work since 1958. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).