Abstract

This article underscores the romanticization of basket weaving in coastal Southern California in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and the survival of weaving knowledge. The deconstruction of outdated terminology, mainly the misnomer “Mission Indian”, highlights the interest in California’s Spanish colonial past that spurred consumer interest in Southern California basketry and the misrepresentation of diverse Indigenous communities. In response to this interest weavers seized opportunities to not only earn a living at a time of significant social change but also to pass on their practice when Native American communities were assimilating into mainstream society. By providing alternative labelling approaches, this article calls for museums to update their collection records and to work in collaboration with Southern California’s Native American communities to respectfully represent their weaving customs.

1. Introduction

This study investigates the misrepresentation of coastal Southern California’s diverse Native communities and their basketry in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century publications and collecting circles. Taking anthropologist Alfred Louis Kroeber’s 1922 publication, Basket Designs of the Mission Indians of California as a case study, I argue that his decision to describe the basketry of over six different culture groups as “Mission Indian” baskets sustained a late nineteenth-century trend to label baskets from Southern California’s Native communities with colonial terminology. Over 150 years prior, Spanish Franciscan missionaries had instituted a series of missions from which Native communities today continue to struggle in disassociating themselves as they seek to exercise self-determination. Through my critique of the “Mission Indian” label, I examine basket production in Southern California and highlight its survivance. As a descendant of “Mission Indians”, specifically from the Los Angeles Basin, I call for updated labeling practices that prioritize individual weavers and tribal identification.

Since the era predating colonization to the present-day, California Indian identity has shifted from being village-based to one of tribal nationhood shaped by colonial politics. At the time of the Spanish incursion, which officially began in 1769, coastal Southern California’s first peoples lived in villages typically overseen by hereditary leaders.1 This sense of community shifted as the Franciscans and soldiers relocated and recruited Native peoples to the missions. Tongva, Tataviam, Chumash, Acjachemen, Payomkowishum, Ipai, and other Indigenous peoples received new identities from the friars who baptized them with Spanish names at the missions. The friars used baptism as a tool to replace village identity and imposed a new, mission-affiliated identity on California Indian converts. Unfortunately, accounts written from a Native perspective are limited, thus making it difficult to know how converted peoples felt about their new names and identities.2

By the late nineteenth century, Native identity, as seen from an outside perspective became further linked to the missions. Florence Shipek observed that “the term Mission Indian had come to include all those Indians whose ancestors were in the Spanish missions from San Francisco south to San Diego at the Mexican border and also those portions of these groups who had remained free of the missions” (Shipek 1978, p. 610).3 This homogenization of California’s Indigenous communities extended beyond political discussions to publications and collectors’ circles which treated baskets as the product of one culture group rather than individual creators or artists. As will be addressed, some of the earliest publications include basket enthusiast George Wharton James’s 1901 guide, Indian Basketry: And How to Make Indian and Other Baskets and Otis Tufton Mason’s Aboriginal American Basketry: Studies in a Textile Art Without Machinery from 1904.

With rare exceptions, California basketry remains on the periphery of Native American art studies. Anthropologists have made significant contributions to our understanding of basket practices, yet little attention has been given to the social history of baskets and their makers. Building on the anthropological interest in basketry techniques and materials that has enabled communities to revive their weaving customs, I analyze the work of early twentieth-century basket weavers whose contributions made it possible for the Chumash, Tongva, Tataviam, Acjachemen, Payomkowishum, Kumeyaay, and neighboring tribes to revive their weaving practice in the latter half of the century. Through a social art historical and Indigenous lens as well as a decolonizing approach, I argue that twentieth-century basket weaving practices reflect basket weavers’ refusal to abandon their traditions. It has been argued that weavers made baskets as a vital source of income during a time of increasing financial instability (Farmer 2004; Bibby 1996). I acknowledge this reality yet push our understanding of agency further by positing that early twentieth-century basket weavers seized commercial sales of their work to sustain their culture in the face of racism, challenges to Indigenous citizenship, and restrictions on Indigenous land management practices.

Drawing upon my personal background as an Indigenous Californian, I bring a perspective that is sensitive to the complexities of Mission Indian identity. While I advocate for an updated approach to basket studies and labeling practices, I acknowledge that historic ties to the missions continue to shape tribal politics. Whereas ancestral knowledge is vital to the production of basketry, I selectively provided information that is relevant to this study and its discussion of survival and resilience. I bring my experience as a Native art historian to this investigation of basketry to dignify the ancestors as well as living weavers.

First, I trace the historical circumstances that shaped settlers’ and tourists’ fascination with California’s missions and the policies that reinforced a sense of “Mission Indian” identity. Then, I turn to baskets and weavers who embraced limited opportunities to sustain their weaving practice in the face of discrimination and limited access to resources. The second half of the article shifts focus to the social history of weaving from its decline to revival. An overview of museum practices acknowledges updated approaches and calls for the recognition of basket weavers as individual agents of cultural survivance.

2. Background

Baskets from California’s central and southern coast were essential to the everyday activities as well as funerary practices of our ancestors. These early weavers made baskets using ephemeral materials such as native plants, juncus textilis and sumac that they gathered according to the seasons. While weavers passed on their knowledge, which is discussed at length in the following section, they did not preserve baskets as future collectors would attempt to do (Weltfish 1930, p. 489; Kroeber 1925, p. 561).4 Even though precontact examples are rare, we know from the archaeological record that the weaving tradition can be traced back as early as 1000 BC (Elsasser 1978, p. 634). California’s first weavers buried baskets with the deceased and burned baskets at funerals (López and Moser 1981, p. 9). While traveling through the Santa Barbara Channel in the 1770s, Fray Pedro Font observed, “near the villages they have a place which we called the cemetery, where they bury their dead. It is made of several poles and planks painted with various colors, white, black, and red, and set up in the ground. And on some very tall, straight and slim poles which we called the towers, because we saw them from some distance, they place baskets which belonged to the deceased, and other things which perhaps were esteemed by them, such as little skirts, shells, and likewise in places some arrows” (Font 1933, pp. 253–54). Though highly valued within Native communities, baskets were not collectibles but personal belongings that remained with their owners after death. Some communities, however, gave baskets to the colonists and explorers they encountered, not anticipating that these vessels containing food and other gifts would inspire a collecting trend.

Some of the earliest descriptions of coastal Southern California baskets date to 1769, when members of the Portolá Expedition reached Alta California to claim the region for Spain. Following the orders of the Spanish crown, Captain Gaspar de Portolá led a group of Franciscan missionaries, soldiers, and Native families from Baja California to Alta California. Spread across three ships and two land excursions, this group of colonists and settlers seized the opportunity to occupy the region they saw as theirs for the taking (Beebe and Senkewicz 2001, pp. 108–9, 114–15). Their accounts reveal the authors’ admiration of the finely woven baskets California’s first peoples made, yet they left out the names of the weavers (Portolá 1909, p. 33; Crespí 2001, p. 397). This issue, which I address later, was part of a larger trend amongst collectors that excluded Native North American material culture from the realm of fine arts. Baskets may have appealed to a non-Native taste for the exotic, but their status as luxury objects would not emerge until some years after the Franciscans established missions.

From 1769 until 1821, Spain retained political and religious control over California and its inhabitants. Mexico’s 1821 independence from the Bourbon monarchy set in motion a brief period of control over California (Gutiérrez and Orsi 1998, p. 160). Next, Mexico initiated the Secularization Act of 1834, which freed Native converts from mission control, yet pushed them towards working on ranches owned by Mexican citizens (Hackel 2005, p. 386). The goal of secularization was to convert the missions into parishes overseen by priests rather than mendicant friars. The Mexican government paid little attention to these religious spaces. The neglected structures proved unsuitable for sheltering Indigenous inhabitants. Few neophytes, or converted Indians could return to their home villages which Mexican citizens had reoccupied and divided into ranches. This issue worsened after Mexico lost the Mexican-American war in 1846.

The Mexican government ceded California to the United States through the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which did not guarantee land in title for Native peoples who lived at the missions nor their descendants (Gutiérrez and Orsi 1998, p. 346; Pritzker 2000, p. 114). In one exception, Victoria Reid, also known as Bartolomea, was the daughter of the chief of the Tongva village of Comicrabit at the Santa Monica Bay near present-day Pacific Palisades (Dakin 1939, p. 33). Following Mission San Gabriel’s secularization Victoria received a land grant of 128 acres in 1830, due to her status as a chief’s daughter (McCawley 1996, p. 43; Reid 1968, p. 1). Other Tongva peoples were less fortunate (Cowan 1956, p. 31). Individuals from neighboring groups faced a similar situation. Without legal title to their ancestral land, few people could gather and hunt for resources as they had before the arrival of foreigners. Access restrictions impacted basket weaving as did changes in lifestyles.

Spain dominated California for nearly seven decades and left a lasting impact on the first peoples of California, but Native weavers managed to keep their traditions alive. At the missions, weavers preserved their art form that they conducted in the privacy of Indian rancherias and as seen at Mission San Buenaventura, Chumash weavers accommodated European influences in their practice. Three known weavers, Juana Basilia Sitmelelene, María Marta Zaputimeu, and María Sebastiana Suatimehue who were baptized at Mission San Buenaventura, wove baskets with symbols that appeared on the Spanish pesos (pieces of eight) that circulated in California in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century (Timbrook 2014, p. 52).5 These symbols including the Bourbon coat of arms and the pillars of Hercules signaled the lasting influence of the faltering monarchy in its overseas dominions.

Head Franciscan of Mission San Buenaventura, Fray José Señán encouraged the weavers to make baskets which in some instances he sent to the College of San Fernando in Mexico City, a Catholic seminary and New Spain’s headquarters of the Franciscan Order, as payment for church decorations (Señán 1962, p. 68; Smith 1982, p. 63). Private individuals also commissioned baskets as gifts, including one that is now in the collection of the National Museum of the American Indian.6 This early interest in baskets as trade and luxury goods for the elite foreshadowed future collecting trends and a Euro-American desire for baskets from communities located in the path of the missions.

Of all California’s basketry, the examples made at the missions that display European influence may be the strongest candidates for the “Mission Indian” label. Yet, as will be shown, “Mission Indian” baskets generally included examples made for the tourist trade. Though reflective of new trends in colonial California, the Chumash baskets from Mission San Buenaventura and other contemporaneous examples including a padre’s hat shaped basket possibly from Mission San Luis Obispo (now in the collection of the British Museum) are representative of pre-existing Indigenous knowledge. This knowledge of native plants, gathering sites, coiling techniques, and natural pigments was essential to the creation of the baskets for which coastal Southern California weavers became known.

3. Basket Weaving Knowledge

The main types of baskets found in California are either coiled or twined. Coiled baskets begin with a starting knot that spirals outward. The spiral is comprised of wefts that wrap around a foundation of warps. A twined basket foundation begins with warps that are tied together at the center. These warps extend out from the knot like a web that can be tightly woven or loose depending on the basket type. In Southern California, coiled basket warps are typically made of juncus, tule, willow or sumac, which are also used for the wefts that tie the warps together.

The tribes of Northern California predominantly weave twined baskets, whereas tribes from the Pomo to the south make both twined and coiled baskets.7 Tribes in coastal Southern California are best known for their tightly woven coiled baskets. Coiled trays, bowls and bottleneck baskets likely garnered the most attention amongst non-Native collectors and admirers. Unfortunately, these admirers overlooked the integral relationship of weaving to ecology.

Each wave of colonists brought invasive species and ideas to California that threatened the survival of native plants and animals. At the missions, the friars introduced foreign crops such as corn, wheat, beans, and vegetables. Farming practices exploited the land, which historically provided for the needs of California Indians. As resources became less available, weavers had to seek basketry materials beyond the missions. The Spanish government also discouraged controlled burns that were meant to regenerate new growth and prevent wild-fires (Anderson 2005, p. 136). By the early twentieth century, the United States Forest Service also suppressed fire burning practices deemed destructive (Anderson 2005, p. 119).

Despite attempts to resist change imposed by imperial regimes, Native peoples still experienced drastic cultural disruption. The Indigenous people who lived at the missions not only adopted European lifestyles, but they also replaced their languages with Spanish, some converted to Christianity and others even made art in the same tradition as the Europeans. Ironically, as Native peoples sought out new identities, non-Native collectors took an interest in Native American material culture. Publications about basketry emphasized an image of Indigenous culture untainted by Western influence. Kroeber’s publication further complicated a sense of authenticity through the anachronistic and misleading “Mission Indian” style, a category which came into popularity at the turn of the century (Cohodas 1997, p. 179).8

4. “Mission Indian” Style and Identity

Kroeber’s 1922 publication offered the first close look at “Mission Indian” basketry and the characteristics that set this group of baskets apart from others produced in California. The baskets Kroeber consulted represent a range of production years from the mission era (1769–1834), including a basket collected in the 1790s during the Vancouver expedition, and through the early twentieth century (Kroeber 1922, pp. 178, 182). These examples are listed and, in some cases, illustrated in his publication. Unfortunately, Kroeber never specified which years the “Mission Indian” style represented.9 Instead he focused on attributes found across a select group of baskets in the collections of the British Museum, American Museum of Natural History, the Museum of the American Indian (known today as the National Museum of the American Indian), and the University of California Museum of Anthropology (now known as the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum).10 According to his study of ninety-seven baskets, the main characteristics of “Mission Indian” basketry include: the use of Juncus, a “prevalence of mottled surfaces”, black as the only dye used, tri-color baskets, “plain twining or multiple foundation coiling”, patterns that lack “solid masses of coloring”, the use of the cross design, and the use of “large free-standing figures” (Kroeber 1922, pp. 154–55, 162, 163, 175). Kroeber identified the cross design as a Native element but attributed its common occurrence to Catholic influences. If the baskets studied bore both Native and European influences, then are we to assume that the “Mission Indian” style only represents baskets made after Spanish colonization or from communities directly impacted by the missions?

According to Kroeber, the “Mission Indians” were people who inhabited the area surrounding ten of Southern California’s missions: San Diego, San Luis Rey, San Juan Capistrano, San Gabriel, San Fernando, San Buenaventura, Santa Barbara, Santa Inés, La Purísima, and San Luis Obispo (Kroeber 1922, p. 153). This list does not account for the remaining eleven missions north of San Luis Obispo that, like their southern neighbors, impacted the lives of inland communities as well as those living directly in the path of the missions. Yet, Kroeber’s list is limited to those groups that shared similar weaving techniques. Prior to the Spanish invasion, these communities exchanged ideas, influencing one another’s material and visual culture. This exchange continued within and outside the missions as well as into the present.

The notion that weavers worked in a style that was somehow inherently tied to the missions or a group of people who may or may not have lived at the missions is misleading. In the 1980s, basket scholar Christopher Moser observed that the tradition of making “Mission” style baskets was declining (Herold 2005, p. 146). Despite popular belief and Kroeber’s attempt at defining a category that emerged in the wake of the curio trade, there never was a “Mission” style or tradition. Weavers certainly would have exchanged ideas that led to the emergence of new techniques or patterns within the context of the missions, but the missions as colonial institutions were not directly responsible for these changes—the weavers were.

Baskets embody generations of knowledge that existed well before Franciscan missionaries arrived in California. Thus, to describe baskets from the region Kroeber identified or any part of California as “Mission Indian” baskets sustains a narrative in which Indigenous peoples remain the passive subjects of a colonial regime. Kroeber’s study is part of a larger school of thought that California Indians were inextricably tied to the missions. In the nineteenth century, the United States government referred to all the tribes in the path of the missions as “Mission Indians”, yet by the twentieth century it only identified certain Southern California groups as such (Shipek 1978, p. 610). In their study of the Mission Indian Agency, Valerie Sherer Mathes and Phil Brigandi state that “The term ‘Mission Indians’ was commonly used during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as a generic term for Southern California’s native peoples. It reflects the conditions the Americans found in villages and reservations at the time, where in many cases even the Indians who had never had direct contact with the Spanish missions had adopted at least some of the trappings of Spanish civilization: the Spanish language, and Catholic beliefs (though both existed side by side with native languages and traditions), and European-style skills such as agriculture and adobe construction” (Mathes and Brigandi 2018, p. 193n1).

The lack of agreement regarding which tribes or communities constituted the “Mission Indian” category further sustains a colonial framework that dismisses the diversity of Southern California’s first peoples. Limited by nineteenth and twentieth-century biases, Mathes and Brigandi’s study underscores the post-Mission era assumptions that Native peoples were inherently tied to Spanish colonization. As they note, most Mission Indian reservations are in San Diego and Riverside counties (Mathes and Brigandi 2018, p. x). Only two missions (San Diego and San Luis Rey) and two assistant missions (San Antonio de Pala and Santa Ysabel) were located in San Diego county and none in Riverside county. Even if they did not live at the missions, California Indians learned Spanish to survive under Spanish and then Mexican rule, but that is no reason to call them “Mission Indians”. Yet, that did not prevent the United States government from appointing agents “to investigate the condition of the Mission Indians” (ibid.). The creation of the Mission Indian Agency in 1850, which underwent restructuring and was ultimately suspended in 1903, coincided with and perhaps legitimized the trend amongst basket collectors to label works from Southern California as “Mission Indian” baskets.

Through the process of naming groups as “Mission Indians”, federal agents and basket collectors reshaped a previously colonized sense of Native identity. Then, from 1919 until the 1970s, a group of California Native peoples identified themselves as the Mission Indian Federation, further complicating the idea that Indigenous identity was somehow connected to the colonial institutions that some have described as death camps (Thorne 1999, p. 191; McWilliams 1946, p. 29). In the latter case, however, the creation of the Mission Indian Federation afforded Indigenous peoples a platform to resist dominant structures and assert their self-determination.

One of the first scholars to write about the Mission Indian Federation, Tanis Thorne describes it as “southern California’s most popular and long-lived grass-roots organization in the twentieth-century” which was “extremely controversial in its day and remains so to the present” (Thorne 1999, p. 191). This group appealed to California Indians seeking a return to self-governance, yet it was not met warmly by all communities. Without going into detail about this group, I raise the example of the Mission Indian Federation to emphasize that some Native and non-Native people have accepted the term “Mission Indian” as a marker of identity. Meanwhile, others fervently reject the association with these institutions which conjure intergenerational memories of abuse and genocide. Given this tension over Mission Indian identity, I caution against discarding it altogether. I propose that scholars of basketry and other material culture acknowledge the community (or tribe) of a weaver and her or his name when known instead of using the misleading “Mission Indian” label.

5. “Mission Indian” Baskets and California’s Spanish Fantasy Heritage

Absent or incomplete provenance records present one of the greatest challenges to studying and cataloguing Native baskets. The names of only a handful of weavers who were active in the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth century exist in the historical record. Early ethnographers typically “did not pay much attention to Indian lady’s names” when documenting basketry provenance (Farmer 2004, p. 82). Only a handful of individuals recognized weavers’ names, yet for different purposes than I propose.

Within the first decade of the twentieth century, Mississippi-based collector Catherine Marshall Gardiner acquired baskets from California (Herold 2005, p. 112). She focused on popular styles, including the “Mission Indian” or “Mission-style” baskets, but also paid attention to those by noteworthy weavers. Her careful recording of artist names in provenance records signifies her awareness of the value baskets gained when associated with a famous weaver. Ramona Lubo (Mountain Cahuilla) was one such weaver whose work Gardiner pursued (Herold 2005, pp. 116–17) (Figure 1). Collectors particularly valued Lubo’s work for its fine craftsmanship and her perceived association with the fictional character in Helen Hunt Jackson’s famous 1884 novel, Ramona about a half Native-half Scottish woman raised on a Mexican rancho. Real-life individuals like Ramona Lubo who still practiced their Indigenous material culture appealed to this interest in a version of California’s history that celebrated Native Americans.

Figure 1.

“Ramona” star tray, Ramona Lubo (Mountain Cahuilla, c. 1847–1922), 1906, grass, sumac, juncus, diameter 15 ½ and height 5/8 inches. Gift of Catherine Marshall Gardiner, Collection of the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, Laurel, Mississippi, 23.85. (Used by permission of the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art)

Lubo represents a generation of weavers who made baskets for sale to collectors and tourists from around 1890 until 1930, in response to the growing interest in California Indian baskets that emerged with the Arts and Crafts Movement (López and Moser 1981, p. 5; Smith-Ferri 1998, p. 67). Ipai basket weaver Justin Farmer describes this era as the “Basket Renaissance…when making Indian baskets for sale became a major cottage industry” (Farmer 2004, p. 21). During this time, weavers made baskets that appealed to collectors’ interests, including the nostalgia for California’s Spanish fantasy heritage tied to the missions (Smith-Ferri 1998, p. 69). Coined by Carey McWilliams in the 1940s, “Spanish fantasy heritage” referred to the propaganda that drew tourists to California in search of a romanticized Spanish past (McWilliams 1968, p. 35; Kagan 2018, p. 227). Jackson’s Ramona helped to spur Anglo-American interest in California and its Native peoples, drawing tourists from the eastern United States who arrived in Southern California by way of the transcontinental railroad.

The advent of the railroad system encouraged and enabled travel across the southwestern states. Beginning with the railroad’s 1880 arrival in New Mexico, entrepreneurs seized the opportunity to sell Native American “artifacts” to travelers by opening curio shops and trading posts at popular stations such as Santa Fe.11 As Jonathan Batkin argues, the market for Native American goods, mainly Pueblo pottery extended beyond tourism. According to him, “Pueblo potters took their wares to Santa Fe, where they sold or traded them to curio dealers” (Batkin 1999, p. 282). This practice had roots in the late seventeenth century when Pueblo peoples sold and traded their wares to the Spanish (Batkin, email to author, 30 May 2019). While future investigations may uncover a parallel situation, that appears not to be the case in Southern California.12 A different model emerged in California where one of the most influential dealers, Grace Nicholson became known for visiting Native communities and obtaining baskets that she sold in her Old Curio Shop in Pasadena.

Though Kroeber was the first scholar to define “Mission Indian” basketry, the category may have its origins in the curio trade.13 Originally from Philadelphia, Nicholson arrived in Pasadena in 1901 and quickly started acquiring baskets from the surrounding Southern California communities. In a 1902 correspondence with Nicholson regarding baskets, basket aficionado and Smithsonian Institution curator of ethnology Otis Tufton Mason referenced the Mission Indians. He wrote, “Your purpose to devote yourself to the Mission Indians is worthy of all praise” (Packer 1994, p. 314). Upon immersing herself in California’s Native American basket scene, Nicholson became acquainted with weavers from the “Mission Indian” tribes. In 1905, she acquired “a large, deep utilitarian bowl from the Luiseño at Pala Mission” (Herold 2005, p. 115). Now in the collection of the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, this basket has an attributed creation date of 1875.14

Nicholson would continue to acquire baskets for private collectors like Catherine Marshall Gardiner. Gardiner and other collectors were interested in the style and symbolic value of baskets rather than the unique characteristics of an individual tribe’s basketry. Collectors, dealers, and scholars’ interactions shaped early twentieth-century collecting trends. As she developed her collection, Gardiner referenced Mason’s, Aboriginal Basketry: Studies in a Textile Art without Machinery, which included instructions for collectors to identify certain qualities in baskets and styles unique to “Mission Indian” weavers (Shipek 1978, p. 113; Mason 1904, pp. 538–40). She may have been familiar with James’s Indian Basketry: And How to Make Indian and Other Baskets which also mentioned “Mission Indian” baskets. Meanwhile, Nicholson and Kroeber’s paths crossed during a field school that Kroeber led in the summer of 1908 (Packer 1994, p. 319). Though Nicholson did not hold a high opinion of Kroeber, they shared an interest in collecting the materials that “remained of a dying culture” (ibid.).

This fear that “real” Native Americans were on the verge of extinction spurred collectors to acquire baskets and to see the places where their makers lived. Misleading narratives of a mild climate, peaceful Indians, benevolent Catholic priests, and land-owning Spaniards drew tourists to the missions where recently settled Anglo-Americans promoted California’s Spanish past through fiestas and plays (McWilliams 1968, pp. 40–41). As McWilliams pointed out, this fantasy heritage hid the racist attitudes that continued to place Mexicans on the margins of Anglo-American society. This racism motivated Mexicans in California, New Mexico, and Texas to claim Spanish rather than mixed or Indian blood (McWilliams 1968, pp. 42–43). California Indians faced similar challenges. While they saw their ancestors celebrated as peaceful, docile converts in John McGroarty’s wildly inaccurate The Mission Play, which debuted in San Gabriel, California in 1912, California Indians also took on new identities out of fear of discrimination in mainstream society (Deverell 2004, p. 162).

“If Anglo-Americans accept their art and culture, why have they not accepted the people?” (McWilliams 1968, pp. 41–42). This question posed by Jovita Gonzales de Mireles regarding the Mexican situation in early twentieth century Southern California could easily apply to California Indians. Anglo-Americans like Catherine Marshall Gardiner hunted down baskets that fit the “Mission Indian” style that to them represented a romantic Spanish past which never existed. Weavers like Ramona Valenzuela (Ipai) and Anita Civé (Cupeño) lived outside the missions, in Mesa Grande and San Ignacio, respectively, during this era of fantasy and racism. Gardiner purchased coiled baskets that each of these weavers made between 1900 and 1923 (Figure 2). Though Gardiner, Nicholson, Kroeber, Mason, and James admired baskets by weavers who worked in the “Mission Indian” style, they did little to help improve the situation of Southern California’s Native peoples. The basket craze aided a handful of weavers in supporting their families in the early twentieth century, but it proved unsustainable as lifestyles shifted.

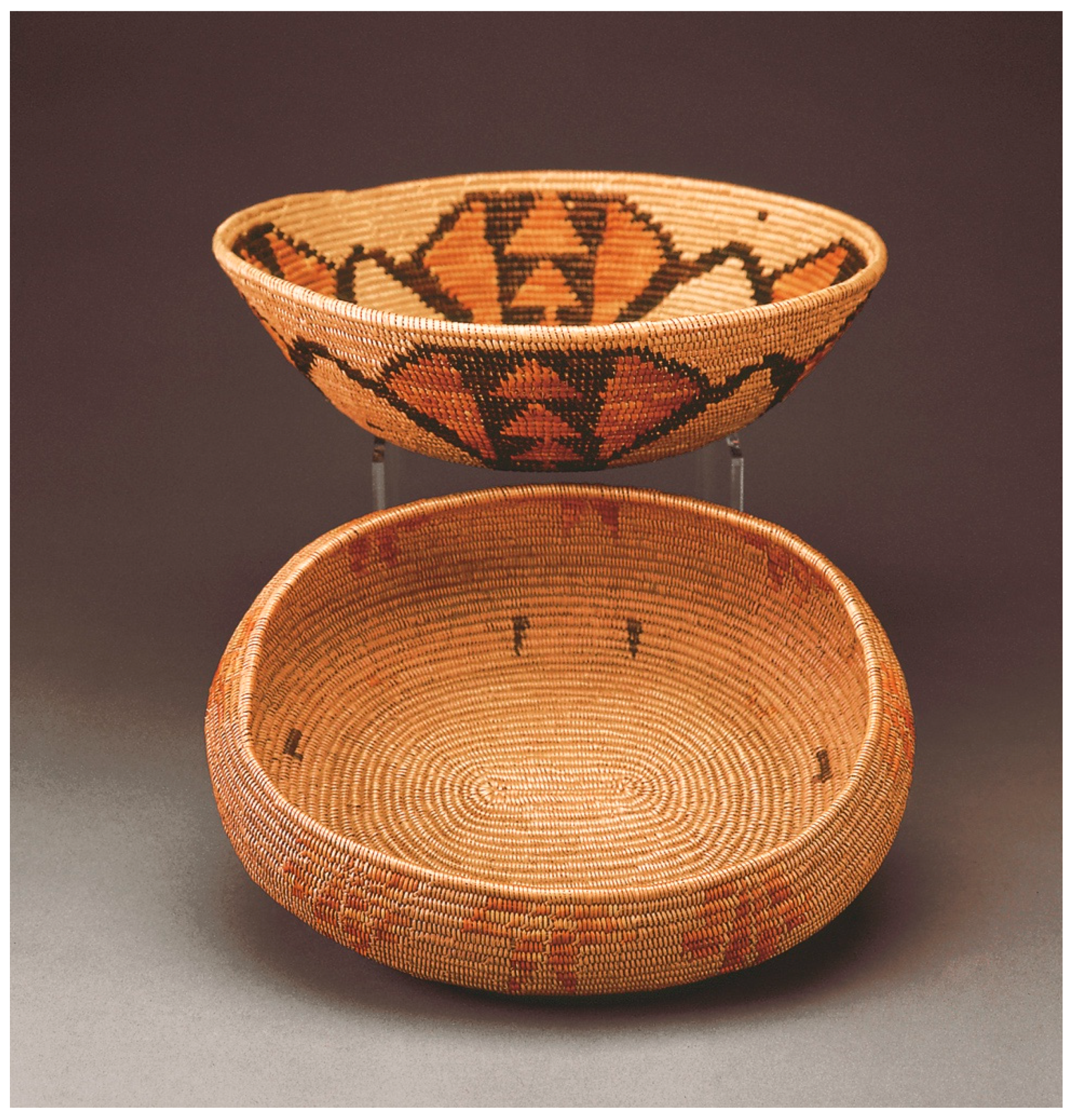

Figure 2.

Bowl with Flower or Star, Anita Civé (Cupeño), 1900–1901, grasses, juncus, dyed juncus, diameter 11 ¼ and height 3 ¼ inches. Gift of Catherine Marshall Gardiner, Collection of the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, Laurel, Mississippi, 23.112. (Top). Oval bowl, Ramona Valenzuela (Ipai), before 1923, grass, three-leaf sumac, rush, 3 ¼ × 9 × 10 ½ inches. Gift of Catherine Marshall Gardiner, Collection of the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, Laurel, Mississippi, 23.88. (Bottom). (Used by permission of the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art)

Fearful that Native Americans were vanishing along with their material culture, Anglo-Americans not only collected Indigenous baskets but also put their makers on display. Though California Indians were missing from San Diego’s Panama-California Exposition of 1915–1917, they later appeared in the 1935–1937 California Pacific International Exposition also held in San Diego’s Balboa Park. At the latter venue, California Indians appeared alongside Native peoples who came from other communities outside of California. Both expositions reinforced California’s Spanish fantasy heritage that was captured in temporary structures that combined Moorish and Mission architectural aesthetics (Kagan 2018, p. 236). Within or nearby these structures, visitors could witness weavers making baskets, thereby recreating the fantasy of California Natives working peacefully in the missions. Such displays showed that Native people still practiced their ancestors’ artistic traditions in the 1930s but they also objectified Native art and Indigenous people. Unfortunately, the historical record provides little information about the Native experience at the California Pacific International Exposition and related venues. Photographs, however, provide a glimpse of the contrived settings in which Native peoples were placed.

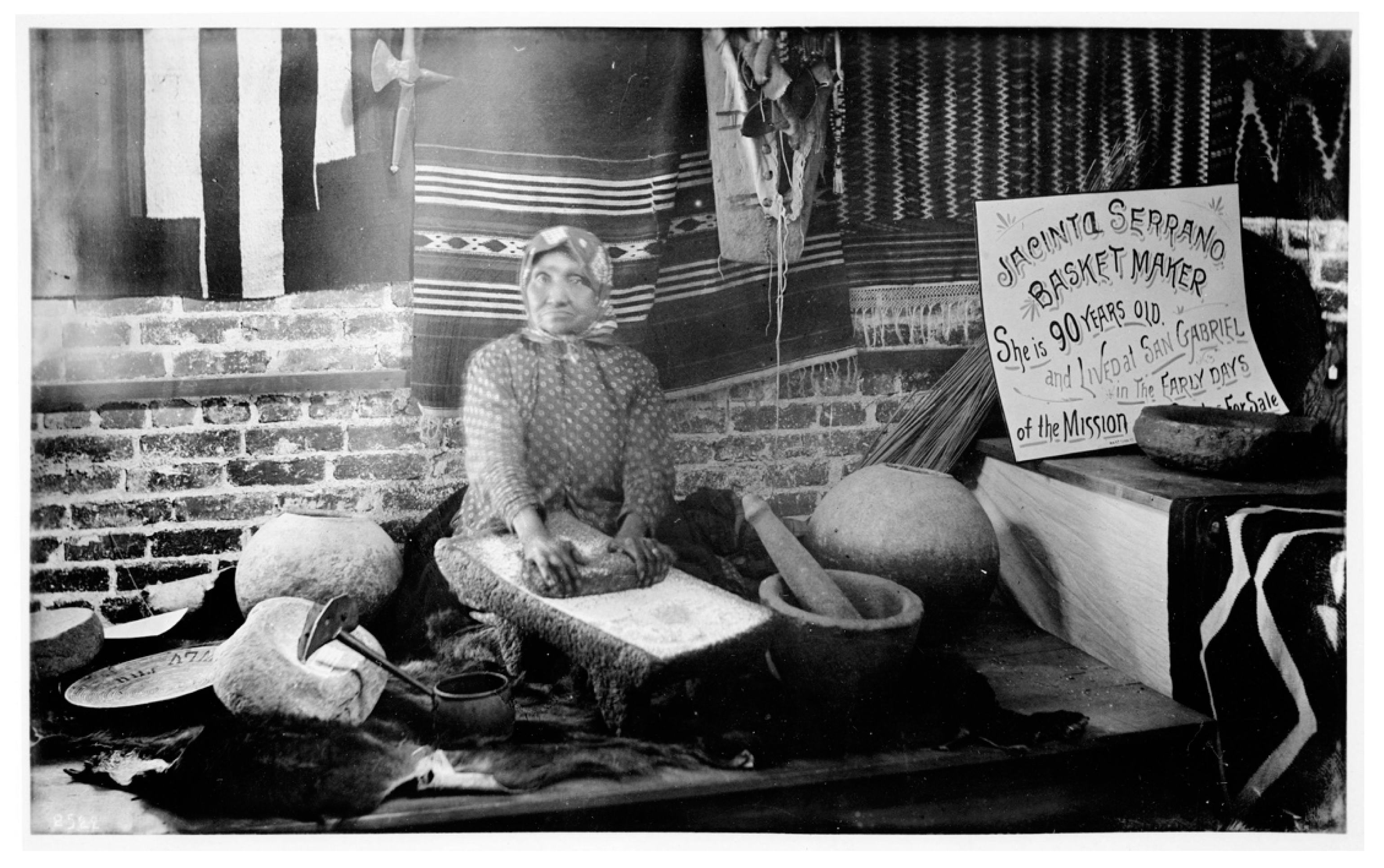

A black and white photograph portrays an elderly woman, identified as Jacinta Serrano sitting on the floor with a metate (mortar) in front of her lap (Figure 3). She holds a stone mano (pestle) in her hands as she looks towards the camera. A mix of vessel types sit on the floor besides the subject who is identified by a sign that reads: “Jacinta Serrano, Basketmaker. She is 90 years old and lived at San Gabriel in the early days of the Mission.”15 Without the sign, how would we know that Jacinta Serrano lived at Mission San Gabriel? Why is this fact important? Appearing to be staged, this photograph captures a moment of transition for Native peoples. Serrano is wearing contemporary clothing. Though the sign states she is a basket maker, she is not actually weaving. Plus, the textiles behind her may be from the southwest, rather than California. Only two baskets can be seen in the photo; one to Serrano’s left, which holds up the sign, and a tray to her right, nestled amongst stone mortars.

Figure 3.

“Jacinta Serrano, last San Gabriel Mission Indian basket maker”, C. C. Pierce (1861–1946), approximately 1887. C. C. Pierce Collection of Photographs, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California, photCL Pierce 01731. (Photograph is in the public domain)

The photograph is given an approximate date of 1887, but this contrived scene captures a moment from the 1888 Art Loan Exhibition in Pasadena. Described as “one of the last surviving neophytes of Father Junipero Serra’s flock”, Serrano was positioned as a living basketry display (Carr 1892, p. 607). Organized by basket collector Ann Picher, the exhibition was part of a larger effort to “make a historical and ethnological study of Mission Natives and their baskets” (Cohodas 1997, p. 184). The note about Serrano’s age and connection to a mission (presumably San Gabriel) sent a conflicting message about “Mission Indian” weavers. On the one hand, Serrano’s association with the mission may be an indicator of authenticity that other weavers who never lived at the mission lacked. On the other hand, the sign’s emphasis on her advanced age, perhaps inadvertently, foreshadowed the decline of weaving with the passing of skilled weavers in the early twentieth century.

The tourist market encouraged basket weaving, but few Native people saw basket weaving as a feasible way to make a living in the twentieth century. Between the 1920s until the 1970s, when weaving underwent a period of dormancy, few master weavers passed on their knowledge to young people within their communities. Brian Bibby has noted that “By the 1940s the market for basketry began to ebb, and the Second World War brought further disruptions” (Bibby 1996, p. 3). The Second World War and the boarding school system, amongst other societal changes, disrupted community connections for Native peoples and pulled them further away from their traditions. Young women did not embrace weaving, since “it wasn’t very chic to be an ‘Indian’ basket weaver in the 1940s or 1950s” (Bibby 1996, p. 4). Native parents felt discouraged about teaching their children Indigenous customs due to prejudice within Anglo-American society and young people were less inclined to pursue cultural knowledge in favor of immersing themselves in mainstream trends.

6. Weaving Programs and Land Management Practices

Though Southern California Native basket weaving fell out of common practice in the mid- twentieth century, weaving knowledge survived. Concerned community members and allies pursued revitalization efforts in the 1980s with the passing of the older generation of weavers. By 1992 basket weavers throughout the state organized the California Indian Basketweavers Association (CIBA), which promotes traditional weaving and offers educational resources. The smaller, Southern California-based group Nex’wetem also holds gatherings for weavers to share their knowledge. Native Californians from across tribal nations now find opportunities to learn their ancestors’ weaving techniques and they are sharing that knowledge with younger generations. Organizations like CIBA and Nex’wetem have been key to helping communities revive their practices, but obstacles remain.16

Pressures from careers and family responsibilities prevent California Indian people from full-time dedication to cultivating basket materials and weaving. Access to materials is another hurdle for weavers, particularly those from tribes that are not federally recognized. Unlike their predecessors who lived in environments undisturbed by pollution and urban development, basket weavers today deal with impediments to gathering materials. The state of California owns most of the land where weavers prefer to gather materials. To collect materials on government land, weavers must obtain permits with the help of CIBA and tribal governments. As part of the organization’s vision, CIBA assists basket weavers “by increasing California Indian access to traditional cultural resources on public and tribal lands and traditional gathering sites, and encouraging the reintroduction of such resources and designation of gathering areas on such lands.”17 This step is crucial in creating a sustainable practice for weavers across California’s communities. Weaving materials cannot be bought in a store but come from the land that our ancestors protected and cultivated for generations before us.

Most weavers respect the plants that provide basket weaving materials and teach their students how to respectfully gather. Weavers collect essential materials during appropriate seasons to harvest basket plants. They respect one another’s collecting sites by identifying their own section rather than competing for plants in one spot. So as not to overharvest native plants, weavers only take what they need and leave plants intact to regenerate new growth for the next collecting season.

By continuing to gather materials, weavers help to cultivate native plants, minimize old growth, and help landowners take proper care of the ecosystem. This process is not about buying into a stereotypical image of Indians created in the American imagination, but an integral component of maintaining balance between the environment and its inhabitants. Colonial power structures overlooked this knowledge, which government entities are now recognizing as vital to creating a sustainable future for California. In 2016, the Karuk tribe of northwestern California and the United States Forest Service burned a five-acre plot of forest in the Karuk tribal region. Collaborating with the Forest Service, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, and the University of California, Berkeley, the Karuk tribe is practicing agroforestry to study the benefits of controlled burns on the ecosystem (Little 2018). For the Karuk, like other communities along California’s Pacific coast, forests are valuable resources for food, medicinal and basketry plants. Forging relationships with government agencies opens opportunities for tribes to act as stewards of their ancestral lands. This article calls for government agencies to enter similar partnerships with southwestern California’s communities. Perhaps efforts by museums and other cultural institutions will help foster such relationships.

7. Museum Practices

The 2018 film, The Art of Basket Weaving, sponsored by CIBA, the Autry Museum of the American West and Southern California broadcaster KCETLink, provides viewers with Native perspectives regarding land stewardship and its connection to basketry.18 In the film, living weavers across California, scholars, and a basket dealer speak about the importance of this practice in maintaining Native knowledge and raising awareness of ecological challenges. In conjunction with the film, the Autry Museum opened a series of exhibits in 2015 as part of their “California Continued” project, which includes a “Human Nature” ethnobotanical garden of California native plants. At workshops held in the garden, weavers from various communities teach museum visitors how to weave baskets. Seeing weavers in person helps break down assumptions about Indians and allows them to speak for themselves.

The Autry Museum’s efforts reflect changes taking place at museums to acknowledge the living community and their knowledge that is embedded in the baskets exhibited behind glass. Exhibits cannot heal the wounds of intergenerational trauma that the missions created for California Indians. Nor can they erase a false sense of identity that the Spanish fantasy heritage continues to instill in tourists and generations of fourth grade students who visit California’s missions and museums where Native voices are nearly absent.

Hundreds if not thousands of unknown weavers were responsible for passing on their knowledge of basket materials, techniques, patterns, and stories. Yet, their contributions remain overlooked. With limited exceptions, museums continue to identify works as “Mission Indian” baskets. As seen with the examples Gardiner collected and later gifted to the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, weavers’ names can be found in provenance records along with their tribal affiliation. Following the examples of the Lauren Rogers Museum, this study calls for collectors and institutions to identify baskets by the maker’s name and tribe, when known, rather than placing them into the “Mission Indian” category. Unfortunately, not all early collectors kept such detailed records, thus leaving out names and tribes. In the absence of this information, museums can consult with tribes and basket experts to identify the closest possible tribe or maker.

Working in collaboration with the author on a previous project the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture has taken another approach to identifying a basket’s culture of origin when a specific tribe or maker is unknown. Though object records for 11 baskets in the ethnology collection retain the word Mission that is now placed in quotation marks, the museum also lists Southern California or proposes the most likely tribe name. For instance, when conducting a search of the collection, one will find a basket for which the culture of origin is given as: Pomo?, “Mission”? (my emphasis). This approach signals a shift in museology practice to involve Native community members, but more work remains to be done.

Unless museum staff are regularly handling “Mission Indian” baskets, they may be unaware of outdated labels within their collection. I present this study in anticipation that museums will look at their collections and take initial steps to update records, perhaps following the Burke Museum example with the eventual goal of replacing “Mission” or “Mission Indian”. As a next step, museums ought to respectively consult with Native community members and weavers. Collectors and museums also have a responsibility to acknowledge the survival of basket weaving and the individuals who are revitalizing the knowledge tied to it. Without information about the people who made the baskets, museum displays perpetuate the idea that California Indians only lived in the past.

8. Conclusions

This study has shown that despite early twentieth-century fears that real Indians and their traditions would “die out”, the knowledge integral to basketry made it possible for Southern California’s Native communities to revive and sustain their practice independently from Spanish colonization. Kroeber used “Mission Indian” in his basket publication because it was common parlance for categorizing many of Southern California’s Native people. Yet, that does not justify its usage which has proliferated subsequent publications on basketry, provenance records, and museum labels. This confusing category, which was anachronistic even for the early twentieth century, no longer deserves a place in museums. Through its re-evaluation of labeling practices, this study calls for museums to update their records and offers a starting point for future scholars to think critically about the ongoing colonization of Native peoples and their practices.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This research took place during my term as a fellow of the President’s Postdoctoral Fellowship Program at UC Santa Cruz. I would like to thank my faculty mentor, Amy Lonetree for inviting me to contribute to this special issue of Arts. I am grateful to Jonathan Batkin, Director of the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian for providing valuable feedback and insight on the curio trade. Many thanks to the anonymous reviewers and editors who offered helpful suggestions and constructive comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Anderson, M. Kat. 2005. Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California’s Natural Resources. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Batkin, Jonathan. 1999. Tourism is Overrated: Pueblo Pottery and the Early Curio Trade, 1880–1910. In Unpacking Culture: Art and Commodity in Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds. Edited by Ruth B. Phillips and Christopher B. Steiner. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 283–99. [Google Scholar]

- Batkin, Jonathan. 2008. The Native American Curio Trade in New Mexico. Santa Fe: Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian. [Google Scholar]

- Beebe, Rose Marie, and Robert M. Senkewicz. 2001. Lands of Promise and Despair: Chronicles of Early California, 1535–1846. Santa Clara and Berkeley: Santa Clara University/Heyday Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bibby, Brian. 1996. The Fine Art of California Indian Basketry. Sacramento and Berkeley: Crocker Art Museum/Heyday Books. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, Jeanne C. 1892. Among the Basket Makers. Californian Illustrated Magazine 2: 597–610. [Google Scholar]

- Cohodas, Marvin. 1997. Basket Weavers for the California Curio Trade: Elizabeth and Louise Hickox. Tucson and Los Angeles: University of Arizona Press/The Southwest Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan, Robert G. 1956. Ranchos of California: A List of Spanish Concessions 1775–1822 and Mexican Grants 1822–1846. Fresno: Academy Library Guild. [Google Scholar]

- Crespí, Juan. 2001. A Description of Distant Roads: Original Journals of the First Expedition into California, 1769–1770. Edited and translated by Alan K. Brown. San Diego: San Diego State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dakin, Susanna. 1939. Scotch Paisano in Old Los Angeles: Hugo Reid’s Life in California, 1832–1852. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deverell, William. 2004. Whitewashed Adobe: The Rise of Los Angeles and the Remaking of Its Mexican Past. Los Angles and Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- DuBois, Constance Goddard. 1903. Manzanita Basketry, A Revival. Papoose 1: 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Elsasser, Albert B. 1978. Basketry. In Handbook of North American Indians, V.8: California. Edited by Robert F. Heizer. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, pp. 626–41. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, Justin F. 2004. Southern California Luiseño Indian Baskets: A Study of Seventy-Six Baskets in the Riverside Municipal Museum Collection. Fullerton: The Justin Farmer Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Font, Pedro. 1933. Font’s Complete Diary: A Chronicle of the Founding of San Francisco. Translated by Herbert Eugene Bolton. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, Ramón A., and Richard J. Orsi. 1998. Contested Eden: California Before the Gold Rush. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hackel, Steven W. 2005. Children of Coyote, Missionaries of Saint Francis: Indian-Spanish Relations in Colonial California 1769–1850. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Herold, Joyce. 2005. Baskets of California. In By Native Hands: Woven Treasures from the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art. Edited by Jill R. Chancey. Laurel: Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, pp. 108–65. [Google Scholar]

- James, George Wharton. 1904. Indian Basketry: And How to Make Indian and Other Baskets, 3rd ed. New York: Henry Malkan. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan, Richard L. 2018. The Invention of Junípero Serra and the “Spanish Craze”. In The Worlds of Junípero Serra: Historical Contexts and Cultural Representations. Edited by Steven W. Hackel. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 227–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kroeber, Alfred L. 1922. Basket Designs of the Mission Indians of California. New York: American Museum of Natural History. [Google Scholar]

- Kroeber, Alfred L. 1925. Handbook of the Indians of California. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Little, Jane Braxton. 2018. The California Indigenous Peoples Using Fire for Agroforestry. Pacific Standard. Available online: https://psmag.com/environment/the-indigenous-groups-using-fire-for-agriculture (accessed on 6 March 2019).

- López, Raúl A., and Christopher L. Moser. 1981. Rods, Bundles & Stitches: A Century of Southern California Indian Basketry. Riverside: Riverside Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, Otis Tufton. 1904. Aboriginal American Basketry: Studies in a Textile Art without Machinery. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Mathes, Valerie Sherer, and Phil Brigandi. 2018. Reservations, Removal, and Reform: The Mission Indian Agents of Southern California, 1878–1903. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCawley, William. 1996. The First Angelinos: The Gabrielino Indians of Los Angeles. Banning and Novato: Malki Museum Press/Ballena Press. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, Carey. 1946. Southern California Country: An Island on the Land. New York: Duell, Sloan & Pearce. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, Carey. 1968. North from Mexico: The Spanish-Speaking People of the United States. New York: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Packer, Rhonda. 1994. Grace Nicholson: An Entrepreneur of Culture. Southern California Quarterly 76: 309–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portolá, Gaspar de. 1909. Diary of Gaspar de Portolá During the California Expedition of 1769–1770. Berkeley: Publications of the Academy of Pacific Coast History. [Google Scholar]

- Pritzker, Barry M. 2000. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, Hugo. 1968. The Indians of Los Angeles County: Hugo Reid’s Letters of 1852. Edited and annotated by Robert F. Heizer. Los Angeles: Southwest Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Señán, José. 1962. The Letters of José Señán, O. F. M. 1796–1823. Translated by Paul D. Nathan. Edited by Lesley Byrd Simpson. Ventura: Ventura County Historical Society. [Google Scholar]

- Shipek, Florence C. 1978. History of Southern California Mission Indians. In Handbook of North American Indians, V.8: California. Edited by Robert F. Heizer. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, pp. 610–18. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Lillian. 1982. Three Inscribed Chumash Baskets with Designs from Spanish Colonial Coins. American Indian Art Magazine 7: 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Ferri, Sherrie. 1998. Weaving a Tradition: Pomo Indian Baskets from 1850 through 1996. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Tac, Pablo. 1958. Indian Life and Customs at Mission San Luis Rey: A Record of California Mission Life. San Luis Rey: Old Mission. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, Tanis. 1999. On the Fault Line: Political Violence at Campo Fiesta and National Reform in Indian Policy. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 21: 182–212. [Google Scholar]

- Timbrook, Janice. 2014. Six Chumash Presentation Baskets. American Indian Art Magazine 39: 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Weltfish, Gene. 1930. Prehistoric North American Basketry Techniques and Modern Distributions. American Anthropologist 32: 454–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Spanish explorers initially visited and explored California’s Pacific coast in 1542. |

| 2 | Pablo Tac wrote the first known account of the Indigenous experience at a mission, specifically Mission San Luis Rey de Francia where he was born in 1822. He did not specify how he felt about the new names given to himself or his people. Tac’s writings have been compiled in Pablo Tac, Indian Life and Customs at Mission San Luis Rey: A Record of California Mission Life (San Luis Rey: Tac 1958). Tongva leader Toypurina did not leave a written account, but expressed her anger at the missions during a 1785 trial regarding her attempted uprising against Mission San Gabriel. |

| 3 | It is generally understood that mission-based names like “Gabrielino” came into use after California’s 1850 statehood. William McCawley observed that “The name Gabrielino, originally spelled Gabrieleños, came into use around 1876 to describe the Indians living in the Los Angeles area at the time of Spanish colonization in 1769” (McCawley 1996, p. 9). |

| 4 | In 1930, archaeologists uncovered the remnants of a pre-Hispanic twined basket on Pimu (also known as Santa Catalina Island) (Weltfish 1930, p. 489). Archaeologists also found a burden basket and storage basket within a Chumash cave (Kroeber 1925, p. 561). |

| 5 | For the weavers’ baptismal records, see “Early California Population Project”, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, https://huntingtonlibrary.libguides.com/c.php?g=892731&p=6419407 (accessed on 1 March 2019). |

| 6 | For information on the basket, see “Basket tray”, National Museum of the American Indian, https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/edanmdm:NMAI_265795?q=juana+basilia&record=2&hlterm=juana%2Bbasilia&inline=true (accessed on 20 March 2019). |

| 7 | The northern tribes to which I refer include the Cahto, Wailaki, Lassik, Wintu, Yana, Atsugewi, Achumawi, Mattole, Bear River, Nongatl, Wiyot, Whilkut, Chimariko, Hupa, Chilula, Yurok, Tolowa, Karuk, Shasta, and Modoc. |

| 8 | Marvin Cohodas pointed out that “Mission” style also encompassed lace and drawn work and furniture produced within and outside the missions. “Southern California’s Native Mission peoples impacted significantly on the national Arts and Crafts Movement, often referred to as the ‘mission’ style, owing to the national popularity of lace and drawn work produced in part by Native women in mission and government schools, and of furniture produced in part by Native men at the Sherman Institute in Riverside” (Cohodas 1997, p. 179). |

| 9 | Neither Mason nor James give dates for “Mission Indian” baskets (Mason 1904; James 1904). |

| 10 | Not all the baskets listed match the accession numbers or culture groups that these institutions use today. |

| 11 | For a close study of the curio trade in New Mexico, see Batkin (1999) and Batkin (2008). |

| 12 | Historical evidence from 1769 to the 1820s indicates that weavers gave baskets as gifts to foreign explorers and made them at the request of mission friars without monetary compensation. Previously mentioned, Juana Basilia’s 1820 basket in the National Museum of the American Indian collection may be one of the earliest examples of a known weaver making a basket at the request of a private individual rather than the Church. Prior instances of Southern California weavers selling or trading their work directly to Spanish colonists remain underexplored. |

| 13 | Future investigations may uncover the first instance of “Mission Indian” used to describe basket types. It appears to be a generic term that basket collectors and enthusiasts, as well as government agents, used freely to describe baskets from Southern California tribes, both coastal and inland, around the year 1900. Aside from Kroeber’s publication that lists the tribes considered Mission Indians, there is no consensus amongst collectors, scholars, and aficionados regarding which tribes fit into this category. In a 1903 article on “Manzanita” baskets from Diegueño (Kumeyaay) weavers, Constance Goddard DuBois called the makers Mission Indians and referred to Mission baskets, indicating that other tribes worked in the style. However, she did not state which groups, beside the Diegueño made Mission baskets (DuBois 1903, p. 26). The following year, Mason attempted to identify the Mission Indians, stating, “Mission Indian basket makers belong to the Shoshonean and Yuman families. They receive their several names from the Franciscan missions of Southern California, into which they were gathered, and where their tribal identity was lost. In the present state of knowledge, it is not possible to distinguish the linguistic family by the shape, technic, or designs of basketry” (Mason 1904, p. 481). Meanwhile, James wrote, “Below the Tahachapi, throughout Southern California and in the Coast Valleys between Santa Barbara and Monterey, are all that remain of the once numerous Mission Indians. These, as the name implies, were the tribes who were under the dominion of the Franciscan friars who controlled the Missions of California. The original names and locations of these people are now but a tradition, and they are generally known by some comparatively recently-given local name” (James 1904, p. 59). |

| 14 | For more information about this basket, see “Object Record”, Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, https://lrma.pastperfectonline.com/webobject/E35DFA3A-65A3-4F3D-ACA5-876223625310 (accessed on 21 May 2019). |

| 15 | “Jacinta Serrano, last San Gabriel Mission Indian basket maker”, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, https://hdl.huntington.org/digital/collection/p15150coll2/id/3640 (accessed on 4 February 2019). |

| 16 | For information on the California Indian Basketweavers Association, visit https://ciba.org/ or follow the organization on Instagram @CIBA.BASKETS. Information about Nex’wetem is best acquired through word of mouth. |

| 17 | “Our Vision”, California Indian Basketweavers Association, https://ciba.org/our-vision/ (accessed on 4 February 2019). |

| 18 | “The Art of Basket Weaving”, KCET ArtBound, https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/episodes/the-art-of-basket-weaving (accessed on 9 February 2019). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).