The Hollywood Dance-In: Abstract and Material Relations of Corporeal Reproduction

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Dance-ins thus served multiple roles simultaneously: they filled in for absent stars and functioned as choreographers’ assistants, “work[ing] out parts of routines” and helping to teach those routines to the stars. As such, the bodies of dance-ins not only accommodated the filmic apparatus; they also mediated the conversion of choreographic ideas into concrete steps, as well as the acquisition of choreography by film stars.1For while the stand-ins are not expected to act, but merely to correspond to the physical presence of those they represent, the dance-ins are supposed to help the dance director formulate his ideas. While the stars are off the set, the dance-ins work out parts of routines which they will later demonstrate to the leading dancers, thus saving the latter a good deal of time and energy.

2. The Dance-In as Material and Virtual Double

In the case of duos, the physical second dancer (what Gil calls the “actual body”) “realizes the virtual double of the dancer” (Gil 2006, p. 25). Even in the absence of a screen, the movement of dance depends on and produces an interplay between virtual and physical bodies.5Paradoxically, the narcissistic position of the dancer does not demand an “I.” Rather, it demands (at least) one other body that can detach itself from the visible body and dance with it. Thanks to the space of the body, the dancer, while dancing, creates virtual doubles or multiples of his or her body who guarantee a stable point of view over movement ….

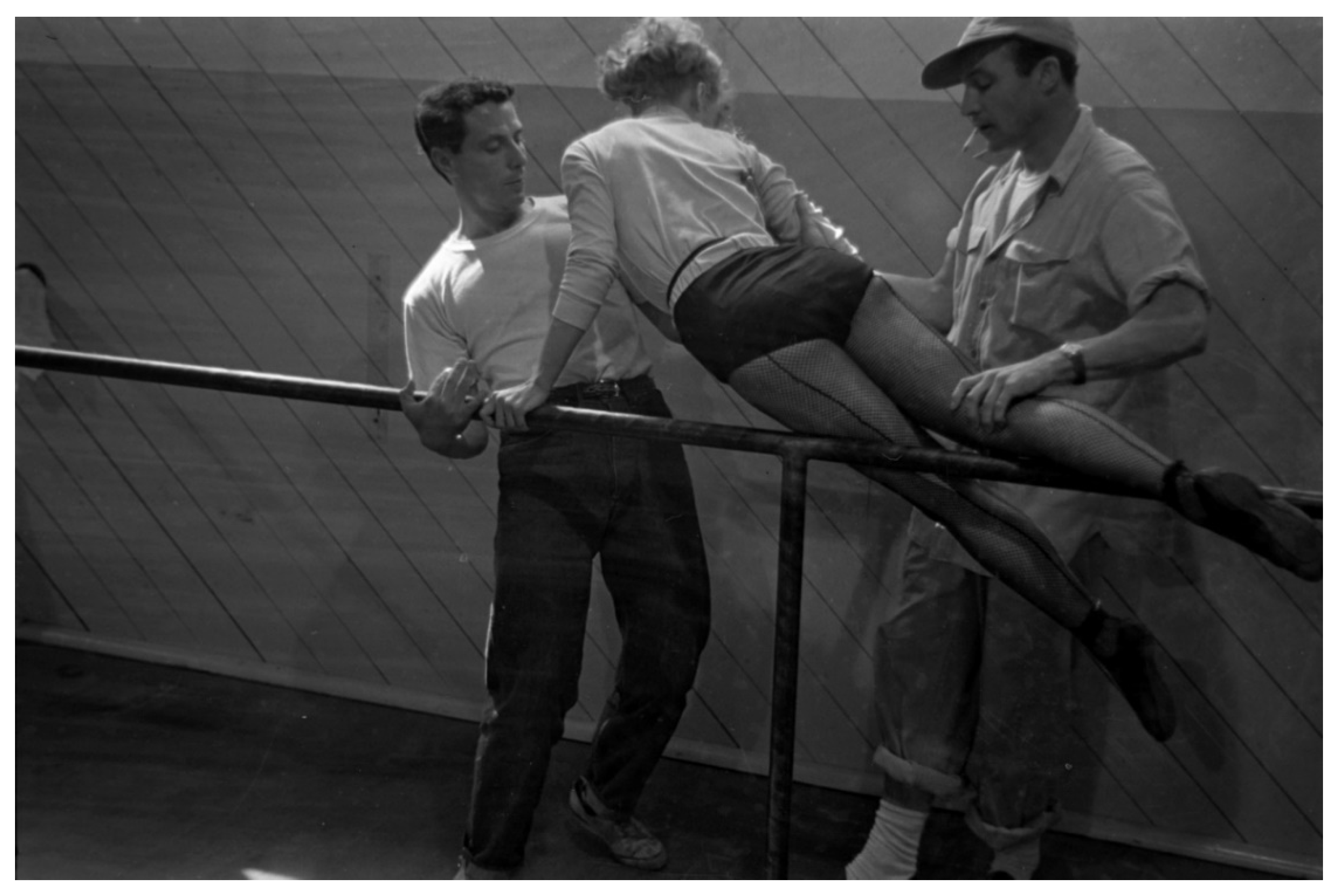

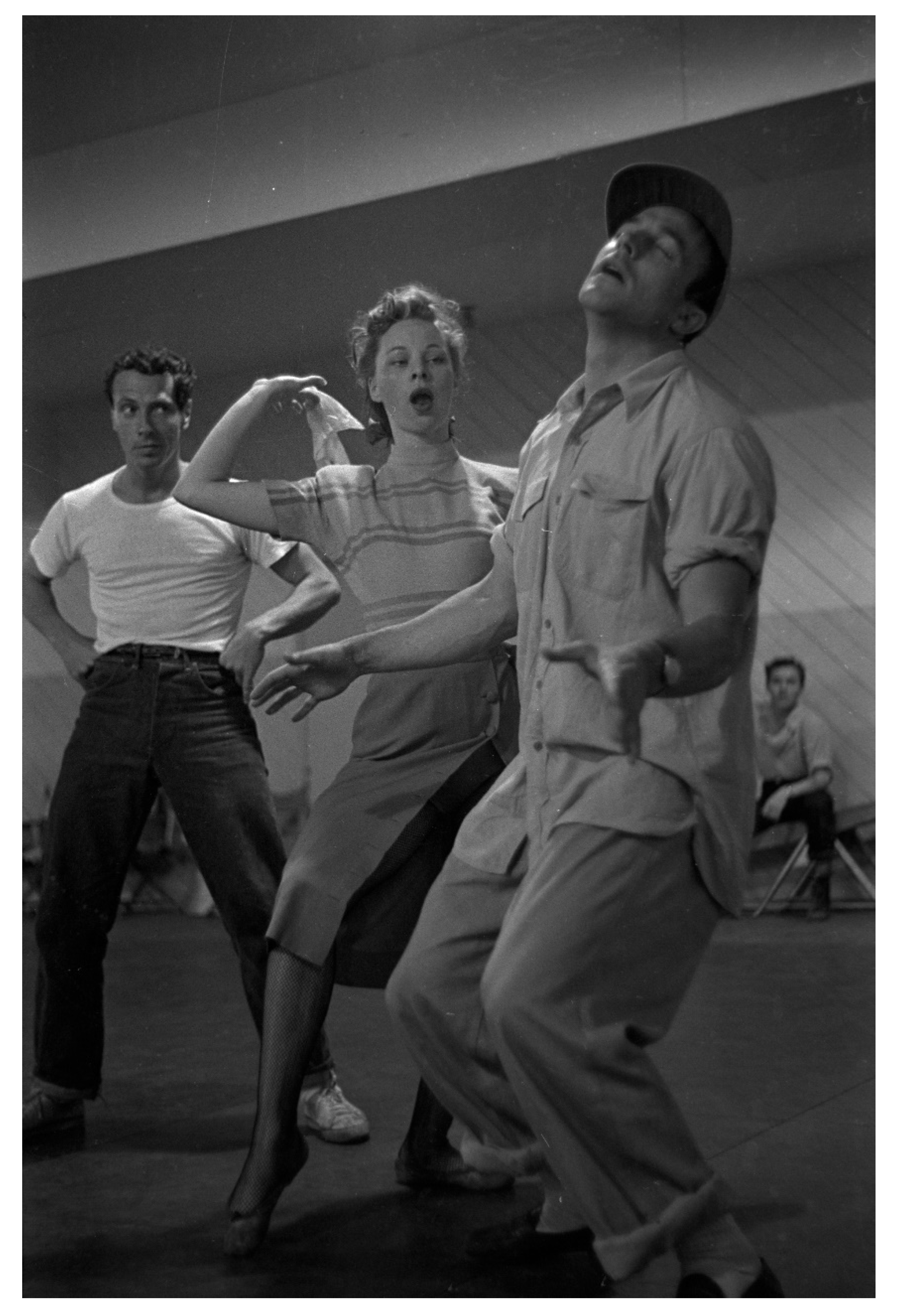

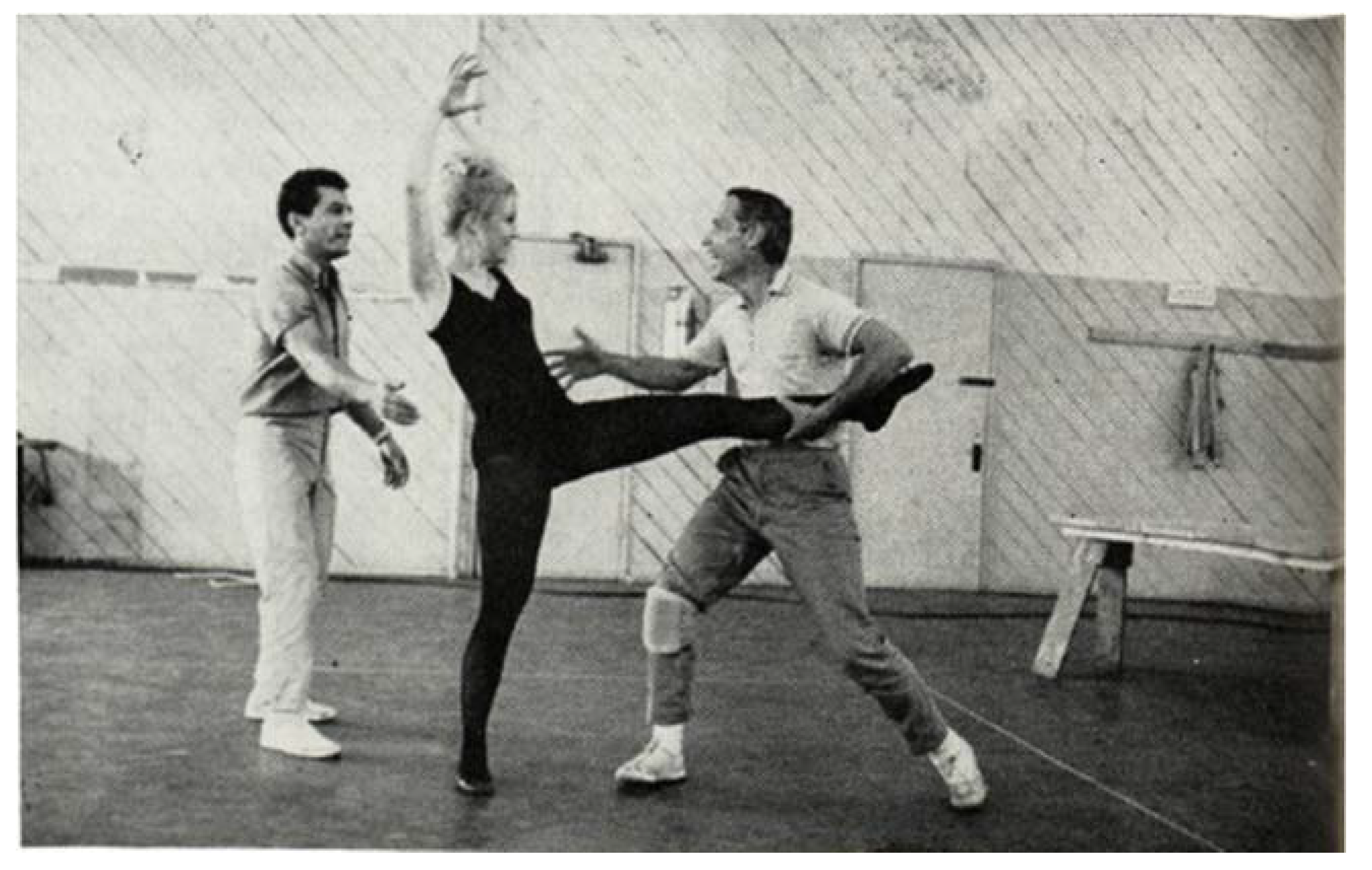

Here, Romero, who was officially employed as an assistant dance director to Robert Alton on Words and Music, does much more than hit Kelly’s predetermined marks and much more than save the star from fatigue; he engages in a steady back-and-forth exchange with Kelly, who juggles his roles as dancer in and choreographer of “Slaughter,” to help determine what and where those marks should be. Unlike a stand-in, Romero does this not by temporarily becoming the object of the camera’s gaze (helping the camera choreograph moves before filming commences) but by inhabiting Kelly’s physicality and projecting it back to Kelly. Lifting Vera-Ellen in Kelly’s place, Romero helps Kelly visualize his own body in the partnering choreography and plot the next moves accordingly. In these moments, Romero is both the object of Kelly’s gaze and a reflection of Kelly’s corporeality. Or, considering Kelly’s comment that the two matched each other in strength and size and that “we’d look at each other,” it is more accurate to say that the two men served as mirrors for one another as they tested out different movement possibilities with Vera-Ellen.We’d stand, we’d look at each other and try these different lifts …. At times like that, you want to see how a lift will look. If he does something whether accidentally or tries something, or I’ll say, “Try another twist. We know we have her up there.” And he does something, I’ll see it. Even if he doesn’t quite know what he did because so much of that, as you know, is trial and error, when you get a variation on a lift.

3. The Dance-In as Queer Mode of Reproduction

In response, Eichenbaum comments, “You’re like a human video recorder,” to which Romero gives a simple “Yes.” In this telling, Romero casts himself as both the choreographer’s shadow and as much more than shadow.7 As an assistant, he stands behind the choreographer’s body while standing in for the choreographer’s bodily memory. Required to pick up new choreography nearly instantaneously, he mirrors back whatever movement has just been demonstrated.The way it normally works is you stand behind the choreographer, and every time he makes a move, you learn it. You have to be plenty sharp at picking things up because he doesn’t know what he’s going to leave in or take out. He throws out so much stuff that he doesn’t always remember what he’s done. He’ll come back to you and say, “What did I just do?” And you have to repeat whatever he demonstrated.

For clarification, Eichenbaum asks if Romero means “that Gene Kelly didn’t want anyone to see that you were helping him.” “He didn’t want anyone to know that he might need help,” Romero replies (Eichenbaum 2004, p. 166).One day I’m in a rehearsal room with Gene Kelly, and he’s doing this number, you see, when suddenly he gets stuck. “Alex,” he says, “what can I do next?” I think to myself, “Well, he never went in that direction and maybe we could add a turn over here,” and suddenly this thing is coming together. He says, “That’s great. Do a little more.” So I choreograph at least a quarter of the number, and he’s applauding me, when suddenly the door opens and in walks the producer, Arthur Freed. Gene pushes me aside and says, “Cool it, Alex.”

Gene Kelly’s attempt to disguise his reliance on Romero seems driven by just this fear. To expose Romero, the assistant and dance-in, as the creator of a chunk of film choreography might threaten Kelly’s status as “author, father, First.” “You have to understand,” Romero tells Eischenbaum, “that he had a huge reputation to maintain” (Eichenbaum 2004, p. 166).8a fear of indiscreet origins …. The fear is that the copy will not only tamper with the original, but will author the original—or, perhaps most fearful, that the copy (the rib, the second) will come to be acknowledged as author, father, First.(Schneider 2001, p. 96, emphasis in original)

4. The Dance-In as Homosocial Buddy

Much of this could also describe the relational structure between Romero and Kelly, who alternatingly observe and incorporate one another, who reproduce themselves in the image of one another, and who, in so doing, (re)produce themselves. Recalling that one of Romero’s fundamental roles was to have his “brain picked” by choreographers, the metaphor of vampirism to describe his queer relationality with Kelly seems remarkably apropos.Vampirism works more like an inverted form of identification—identification pulled inside out—where the subject, in the act of interiorizing the other, simultaneously reproduces itself externally in that other. Vampirism is both other-incorporating and self-reproducing; it delimits a more ambiguous space where desire and identification appear less opposed than coterminous, where the desire to be the other (identification) draws its very sustenance from the desire to have the other.12

5. The Dance-In as Dark Copy

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acharya, Rohini, and Eric Kaufman. 2019. Turns of ‘Fate’: Jack Cole, Jazz and Bharata Natyam in Diasporic Translation. Studies in Musical Theatre 13: 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bench, Harmony. 2004. Virtual Embodiment and the Materiality of Images. Extensions: The Journal of Embodied Technology 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bhabha, Homi. 1984. Of Mimicry and Man. October 28: 125–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billman, Larry. 1997. Film Choreographers and Dance Directors: An Illustrated Biographical Encyclopedia, with a History and Filmographies, 1893 through 1995. Jefferson: McFarland. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers-Letson, Joshua. 2018. After the Party: A Manifesto for Queer of Color Life. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chase, Barrie. 2019. Interview with Author. Personal Interview. Venice, May 8. [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm, Ann. 2000. Missing Persons and Bodies of Evidence. Camera Obscura 43: 123–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Roy. 1962. Alex Romero Compares Hollywood and Broadway. Dance Magazine 36: 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Clover, Carol. 1995. Dancin’ in the Rain. Critical Inquiry 21: 722–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohan, Steven. 2005. Incongruous Entertainment: Camp, Cultural Value, and the MGM Musical. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Croft, Clare. 2017. Introduction. In Queer Dance: Meanings and Makings. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Dirks, Tim. n.d. AFI’s Greatest Movie Musicals. AMC Filmsite. Available online: https://www.filmsite.org/afi25musicals.html (accessed on 27 September 2019).

- Dodds, Sherril. 2001. Dance on Screen: Genres and Media from Hollywood to Experimental Art. London: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Doty, Alexander. 1993. Making Things Perfectly Queer. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum, Rose. 2004. The Assistant. In Masters of Movement: Portraits of America’s Great Choreographers. Washington: Smithsonian Books, pp. 164–75. [Google Scholar]

- Finklea & Austerlitz. 1953. “Finklea & Austerlitz, Alias Charisse & Astaire”. Newsweek, July 6, pp. 48–50. [Google Scholar]

- Flatley, Jonathan. 2017. Like Andy Warhol. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, Susan Leigh. 1997. Dancing Bodies. In Meaning in Motion: New Cultural Studies of Dance. Edited by Jane Desmond. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 235–58. [Google Scholar]

- Fuss, Diana. 1992. Fashion and the Homospectatorial Look. Critical Inquiry 18: 713–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstner, David Anthony. 2002. Dancer from the Dance: Gene Kelly, Television, and the Beauty of Movement. Velvet Light Trap. Available online: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A92589215/LitRC?u=ucriverside&sid=LitRC&xid=fe8c2665 (accessed on 30 August 2019).

- Getsy, David J. 2015. Abstract Bodies: Sixties Sculpture in the Expanded Field of Gender. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, José. 2006. Paradoxical Body. TDR: The Drama Review 50: 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschild, Brenda Dixon. 1996. Digging the Africanist Presence in American Performance: Dance and Other Contexts. Westport: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, Brian Eugenio. 2015. Latin Numbers: Playing Latino in Twentieth Century U.S. Popular Performance. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Grover. 1938. Star Shadows. Colliers, April 30, pp. 18, 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, Gene. 1958. Dancing: A Man’s Game. Omnibus, Hosted by Alistair Cooke, Produced by Robert Saudak. New York: NBC, December 21. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, Gene. 1975. Transcript of interview by Marilyn Hunt. *MGZMT 5-234, Jerome Robbins Dance Division. New York: New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, Patricia Ward. 2017. Facebook Post. October 7. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10159537747250061&set=p.10159537747250061&type=3&theater (accessed on 19 June 2019).

- Knowles, Mark. 2013. The Man Who Made the Jailhouse Rock: Alex Romero, Hollywood Choreographer. Jefferson: McFarland. [Google Scholar]

- Kraut, Anthea. 2019. The Dance-in and the Re/production of White Corporeality. International Journal of Screendance 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krayenbuhl, Pamela G. 2017. Dancing Race and Masculinity across Midcentury Screens: The Nicholas Brothers, Gene Kelly, and Elvis Presley on American Film and TV. Order No. 10277718. Ph.D. dissertation, Northwestern University, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. Available online: https://search.proquest.com/docview/1911776488?accountid=14521 (accessed on 30 August 2019).

- Levine, Debra. 2012. Jack Cole. Dance Heritage Coalition. 8p. Available online: http://www.danceheritage.org/treasures/cole_essay_levine.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2019).

- Levine, Debra. 2013. George Chakiris, Choreographer’s Assistant for Judy Garland’s 1956 Vegas Revue. Artsmeme. September 16. Available online: https://artsmeme.com/2013/09/16/chakiris-choreographer-assistant-judy-garlands-vegas-debut-1956/?fbclid=IwAR3qMGRM1TZHS2IdsY7QdIUKgkrs1_mbQGONWtGof1odcSQzeMZ5iH0VenU (accessed on 3 June 2019).

- Loney, Glen. 1984. Unsung Genius: The Passion of Dancer-Choreographer Jack Cole. New York: Franklin Watts. [Google Scholar]

- Lott, Eric. 1993. Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Middle Class. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Macías, Anthony. 2008. Mexican American Mojo: Popular Music, Dance, and Urban Culture in Los Angeles, 1935–1968. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, Susan. 2004. Modern Dance, Negro Dance: Race in Motion. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Cruz, Paloma. 2016. Unfixing the Race: Midcentury Sonic Latinidad in the Shadow of Hollywood. Latino Studies 14: 150–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, Adrienne L. 2004. Being Rita Hayworth: Labor, Identity, and Hollywood Stardom. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Richard. 1994. Warhol’s Clones. Yale Journal of Criticism 7: 79–109. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D. A. 1998. Place for Us: Essay on the Broadway Musical. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, José Esteban. 1999. Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, José Esteban. 2013. Race, Sex, and the Incommensurate: Gary Fisher with Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick. In Queer Futures: Reconsidering Ethics, Activism, and the Political. Edited by Elahe Haschemi Yekani, Eveline Kilian and Beatrice Michaelis. New York: Rougledge, pp. 103–15. [Google Scholar]

- On the Town, 1949. Directed by Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen. Produced by Arthur Freed. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Burbank: Warner Home Video. DVD 2008.

- Paredez, Deborah. 2009. Selenidad: Selena, Latinos, and the Performance of Memory. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paredez, Deborah. 2014. ‘Queer for Uncle Sam’: Anita’s Latina Diva Citizenship in West Side Story. Latino Studies 12: 332–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, Luis, and Peter Rubie. 2000. Hispanics in Hollywood: A Celebration of 100 Years in Film and Television. Hollywood: Lone Eagle. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, Douglas. 2012. Screendance: Inscribing the Ephemeral Image. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Rebecca. 2001. Hello Dolly Well Hello Dolly: The Double and Its Theatre. In Performance and Psychoanalysis. Edited by Adrian Kear and Patrick Campbell. New York: Routledge, pp. 94–114. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Rebecca. 2005. Solo Solo Solo. In After Criticism: New Responses to Art and Performance. Edited by Gavin Butt. Malden: Blackwell, pp. 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. 2016. Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Slide, Anthony. 2012. Hollywood Unknowns: A History of Extras, Bit Players, and Stand-Ins. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press. [Google Scholar]

- Valis Hill, Constance. 2001. From Bharata Natyam to Bop: Jack Cole’s ‘Modern’ Jazz Dance. Dance Research Journal 33: 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincs, Kim. 2016. Virtualizing Dance. In The Oxford Handbook of Screendance Studies. Edited by Douglas Rosenberg. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 263–82. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, Stacy. 2006. ‘We’ll Always Be Bosom Buddies’: Female Duets and the Queering of Broadway Musical Theater. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 12: 351–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The labor of a dance-in thus overlapped considerably with that of an assistant dance director. Speaking about his work with choreographer Robert Alton on Judy Garland’s 1956 Las Vegas revue, dancer George Chakiris told historian Debra Levine, “Alton had two assistants. On Joan Weaner he choreographed what Judy was going to do. He taught me what the guys would do—and I taught them. That’s what choreographers did. They worked with assistants shaping the material before working with the star” (Levine 2013). |

| 2 | In a 2019 interview, Hollywood dancer Barrie Chase, who worked on both sides of the dance-in/star equation, confirmed that because stars had so many demands on them and so little time to rehearse, it is safe to assume that dance-ins were present on any Hollywood film that featured dancing (Chase 2019). My gratitude to Debra Levine for facilitating my interview with Chase. |

| 3 | Across the fields of media studies, dance studies, and their interdisciplinary intersections, it is standard to think of the body as that which is mediated by technology (Rosenberg 2012, p. 11; Dodds 2001). Yet, one of the premises of this essay is that, by attending more closely to the mediations and exchanges that precede the creation of the film image, we might conceive of the “live body” as something that is produced and reproduced in ways that make it more similar to the “screen body” than something that exists in opposition to the screen. At the same time, I’m interested in exploring the ways the body (often posited, especially in the field of visual art, in opposition to, or as that which grounds, the abstract), as well as the reproduction of movement across bodies, depend on and call into being abstract, ambiguous, and often ambivalent forces and meanings that are polyvalent and “unforeclosed.” See (Getsy 2015, especially pp. xiv, 41, 276–78). |

| 4 | As Knowles points out, it is practically impossible to identify with any certainty all of the films on which Romero worked, given how regularly he was asked to assist on an isolated film number (Knowles 2013, pp. 4–5). |

| 5 | My use of the term “virtual” here and throughout this essay is meant to refer to that which exists in relation to but exceeds the material, encompassing the imagined and the imaged, the projected and the abstracted, that which prefigures, accompanies, and remains of the physical body when it is not physically present. A more thorough discussion of what constitutes the virtual is outside the scope if this essay. For a useful survey of theories of and approaches to the virtual in dance, see (Vincs 2016) and (Bench 2004). |

| 6 | Patricia Ward Kelly’s post also quotes Gene Kelly as saying that Hoctor was “the first female dance-in a male star ever had” (Kelly 2017). |

| 7 | Stand-ins were frequently figured as stars’ shadows. See, for example, (Jones 1938). |

| 8 | Romero also tells Eichenbaum that Fred Astaire acknowledged his reliance on Romero to Arthur Freed, suggesting that this anxiety around authorship and originality was not monolithic (Eichenbaum 2004, p. 166). |

| 9 | |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 12 | José Muñoz quotes this same passage from Fuss as part of his development of a model of subject formation that allows for “desire’s coterminous relationship with identification” (Muñoz 1999, p. 13). See also Jonathan Flatley’s discussion of Andy Warhol’s project of “likeness,” which “made space for Warhol to conceive of attraction, affection and attachment without relying on the homo/hetero opposition so central to modern ideas of sexual identity and desire” (Flatley 2017, p. 5). My thanks to Rebecca Chaleff for calling Flatley’s text to my attention. Richard Meyer’s analysis of Warhol’s clones is also pertinent here. Meyer writes that “When a movie still of Elvis Presley seeks itself through Warholian repetition, it discovers a homoeroticism that its original Hollywood context could not acknowledge” (Meyer 1994, p. 96). We might also see the dance-in as a site of homoerotically charged repetition, although a repetition that precedes rather than succeeds the “original Hollywood context.” As such, the dance-in once again disrupts the chronology of original and copy. |

| 13 | See also (Bhabha 1984) on the racial dynamics of mimesis. |

| 14 | According to Knowles, the Quiroga family lived at 3861 Second Avenue in Los Angeles (Knowles 2013, p. 14). |

| 15 | On Cole’s multi-racial borrowings, see (Loney 1984; Valis Hill 2001; Levine 2012; Acharya and Kaufman 2019). |

| 16 | As Reyes and Rubie tell us, the “Good Neighbor Policy” period from the late 1930s through the 1940s, during which Hollywood sought to exploit the South American film market as it faced the wartime loss of access to European markets, “saw the further development of the Hispanic American actor in Hollywood.” Those who became stars—like Cesar Romero, Rita Hayworth, and Anthony Quinn—“had no accents, were either born or raised in the United States, and portrayed ethnically diverse roles including American types” (Reyes and Rubie 2000, p. 21). For Hayworth, who was born Margarita Cansino, an “ambivalence” between ethnic specificity and American unmarkedness was “a constant of her stardom” (McLean 2004, p. 36). Romero’s career might also bear similarities with that of the post-war light-skinned Mexican singer Andy Russell, about whom Paloma Martinez-Cruz writes, “With an Anglicized name, light complexion, and a sonically White performance profile, Russell serves as a counterpoint to radical Latino performance because he did not cut what might be described as an ‘oppositional’ path to the top of the charts.” But, she maintains, “his serenely cheerful, bilingual self-representation” and his emphasis on his “Americanness” should not be equated with an assimilationist stance (Martinez-Cruz 2016, p. 159). Romero’s closeness to white Hollywood may have been a source of conflict between him and the Mexican comedian Cantinflas. Describing this conflict, Knowles reports that “Alex found out that Cantinflas was shunning him because he considered Alex a pochos, a Spanish word meaning a native-born Mexican who denies his heritage. Cantinflas’ behavior was hurtful to Alex, who always maintained a fierce pride about his Mexican heritage” (Knowles 2013, p. 190 n.9). |

| 17 | Macías’s observation that “Even though Mexican Americans were relatively freer to move about a wider range of the city than African Americans were, doing so exposed them to further police discrimination” is relevant here (Macías 2008, p. 95). |

| 18 | On the privilege of being read as “unmarked” in dance, see (Manning 2004). In addition to appearing as an uncredited chorus dancer in a number of films, Romero doubled for Jules Munshin in portions of the “Day in New York” ballet number in On the Town. |

| 19 | Here I invoke Homi Bhabha’s terms for the ambivalence of the colonized subject, who mimics but can never achieve the whiteness of the colonizer (Bhabha 1984, p. 132). As I have been suggesting throughout, the relational schema of the dance-in required mimicry in two directions. In fact, as Krayenbuhl points out, Kelly darkened his skin for his role in The Pirate (1948), which was “likely a purposeful means of marking Kelly’s character as ‘Latin,’ since he claims to come from Madrid” (Kelly 2017, pp. 151–52). Romero and Kelly began working together after Kelly’s appearance in The Pirate. |

| 20 | My reading of Muñoz is informed and enriched by (Chambers-Letson 2018). |

| 21 | My thanks to Clare Croft for underscoring intimacy as central to the queer relations between dance-in and star. |

| 22 | See also Paredez (2014, p. 347) on “the ambivalence shared by many Latinas/os in their journeys toward citizenship.” |

| 23 | Although the Dance Magazine article does not address the ethnic/racial identity of Ruiz, it does discuss Romero’s and Mimieux’s: “Alex Romero is of Spanish extraction, Yvette Mimieux’s mother is Mexican. A mutual interest in bull-fighting is inevitable. The subject is discussed, with gestures, as Yvette and her much-respected choreographer stroll across the studio lot” (Clark 1962). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kraut, A. The Hollywood Dance-In: Abstract and Material Relations of Corporeal Reproduction. Arts 2019, 8, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040133

Kraut A. The Hollywood Dance-In: Abstract and Material Relations of Corporeal Reproduction. Arts. 2019; 8(4):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040133

Chicago/Turabian StyleKraut, Anthea. 2019. "The Hollywood Dance-In: Abstract and Material Relations of Corporeal Reproduction" Arts 8, no. 4: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040133

APA StyleKraut, A. (2019). The Hollywood Dance-In: Abstract and Material Relations of Corporeal Reproduction. Arts, 8(4), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040133