Abstract

Since the early 1970s, the origins of artists’ books have been extensively discussed and documented (Drücker, Lauf, Lippard, Phillpot, Gilbert et al.), yet the genre continues to generate new questions and paradoxes regarding its place and status within the visual arts as a primary medium. Whilst the conception of contemporary artists’ books lay in the medium’s potential for dissemination via mass production and portability, opportunities for distribution remain limited to a select number of outlets worldwide or, as an alternative, through the growing in number but time-limited artists’ book fairs, such as those established events in Barcelona, Berlin, Bristol, Leeds, London, New York and Seoul. In parallel with the development of screen-based digital technologies and social media platforms, we have experienced the exponential production of artists’ books in contemporary art practice, craft and design; a quiet revolution that emerged from both the centre and the fringes of the art world over six decades ago, developing relatively quickly as a gallery commodity through artefact/exhibition catalogue cross-overs, and more recently as a significant discipline in its own right within educational establishments. This begs the question, why, in an era of potentially print-free communication, do we continue to pursue the possibilities of the physical book format? What can the traditional structures of the codex, the leporello, the single section or that most basic and satisfying action of creasing a sheet of paper—the folio—offer the tech-savvy audience or maker? But artists’ publications offer alternative platforms for visual communication, resistant to formal forms of presentation, and they appeal to the hand and can question what it means to read in this digital age.

The popularity of artists’ books is evident in the number of fairs, self-publishing platforms, exhibitions, websites and course modules dedicated to them. Despite the omnipresence of digital screens, artists’ books continue to be made, shared and experienced. This survival, and indeed their proliferation as a form of creation, is rooted in their nature as resistant transmitters. Their resistance could be said to be multiple and their ability to transmit ideas unique. Artists’ books resist definition,1 taking multiple forms and pursuing multifarious themes. They transmit ideas and explore forms of knowledge transfer that go beyond the restrictions of a single artwork or written word. Their unique power and agency lie in their nature as hybrids. The practice of making artist’s books traverses the world of art but also the world of books and consequently ties in with multiple cultural practices and areas of knowledge (Burkhart 2006, p. 264). Their dependence on the physical engagement of the reader increases their potency as artworks, and as a ‘technology of enchantment’ (Gell 1992). For artists’ books, much like visual archives, call for perusal. They do not surrender happily to passive display, as their ideal habitat is in the hand rather than a glass cabinet. Consequently, they can circumvent some of the limitations of the mainstream art world. For the viewer activates and controls the space–time evolution of the narratives they propose. Their efficacy lies in the way they communicate, as the reception of an artist’s book is on multiple levels. Their strength lies in the fact that unlike sculptures or paintings, “you can touch, handle, and even in the swish of the pages and the clop of the covers, hear many artists’ books. Held in intimate proximity to our face and body, they reference our human scale” (Burkhart 2006, p. 262). This power of artists’ book as tools of enchantment and their transportability has helped them to flourish. Although present in museum collections2, libraries, art exhibitions and online platforms, it is in artist-run distribution centres and at the fairs dedicated to artists’ books where their power as resistant transmitters is most evident. For here, artists’ publications can function as objects of exchange and interaction, outwith the restrictions of institutional display cabinets. They may be objects of commerce but also generate dialogue and community. Their physical and temporal qualities and their ability to transmit and generate the exchange of ideas on multiple levels point to artists’ books as potent ‘mutable mobiles’ in this digital age.

1. Artists’ Books as Hybrids Resistant to Definition

The debate about how to define an artist’s book has existed since the early seventies. Indeed, the origins of artists’ books have been extensively discussed and documented (Drücker, Lippard, Phillpot et al.), yet the genre continues to generate new questions. As Drucker (1995) suggests, any definition of an artist’s book causes some publications to be excluded, for they move between formats, supports and ideas, between the unique and the multiple. Clive Phillpot’s Diagram (1982)3 points to a definition that incorporates books made or conceived by artists, encompassing book objects, literary books, and book art where the worlds of art and books overlap. Others, such as Annette Gilbert, prefer to focus on publishing as an artistic practice rather than on the artefacts produced, for any work published, “cannot be regarded independent of the publishing process and its determining factors” (Gilbert 2016, p. 7). What is clear, however, is that the publications made by artists cross boundaries. It is their hybrid or ‘mongrel’ (Burkhart 2006) nature that affords them their efficiency as transmitters. They sit at the juncture of established practices such as literature, art, graphic design and publishing. They permit the correlation and interrelation of different systems of representation, which in turn reveal new avenues and perspectives. There is not an all-encompassing version of what an artist’s book is, so much as multiple and conflicting visions. Accordingly, there are multifarious ways to describe artists’ books and a resulting ‘methodological abundance’ (Hannula 2009, p. 5) in their fabrication. Like archives, artists’ books can accommodate almost everything. Nevertheless, like archives, they are dependent on activation. Their narratives are constructed and layered through the recipient’s act of reading and manipulation. Just as the Mexican artist, writer and promoter of artists’ books, Ulises Carrión, suggested in 1975, in his manifesto, El Arte Nuevo de Hacer Libros4: “A book is a sequence of spaces. Each of these spaces is perceived at a different moment- a book is also a sequence of moments” (Carrión 1975). The strength of artists’ books is their agency as a form of ‘intermedia’ (Higgins 1966). They can combine multiple modes of art and provide ways to express ideas which may not be able to find their expression as paintings, wall pieces, sculptures or otherwise. Important aspects of their tenacity as transmitters are their portability and the sensorial experience they create.

2. Artists’ Books as Tools of Enchantment or Mutable Mobiles

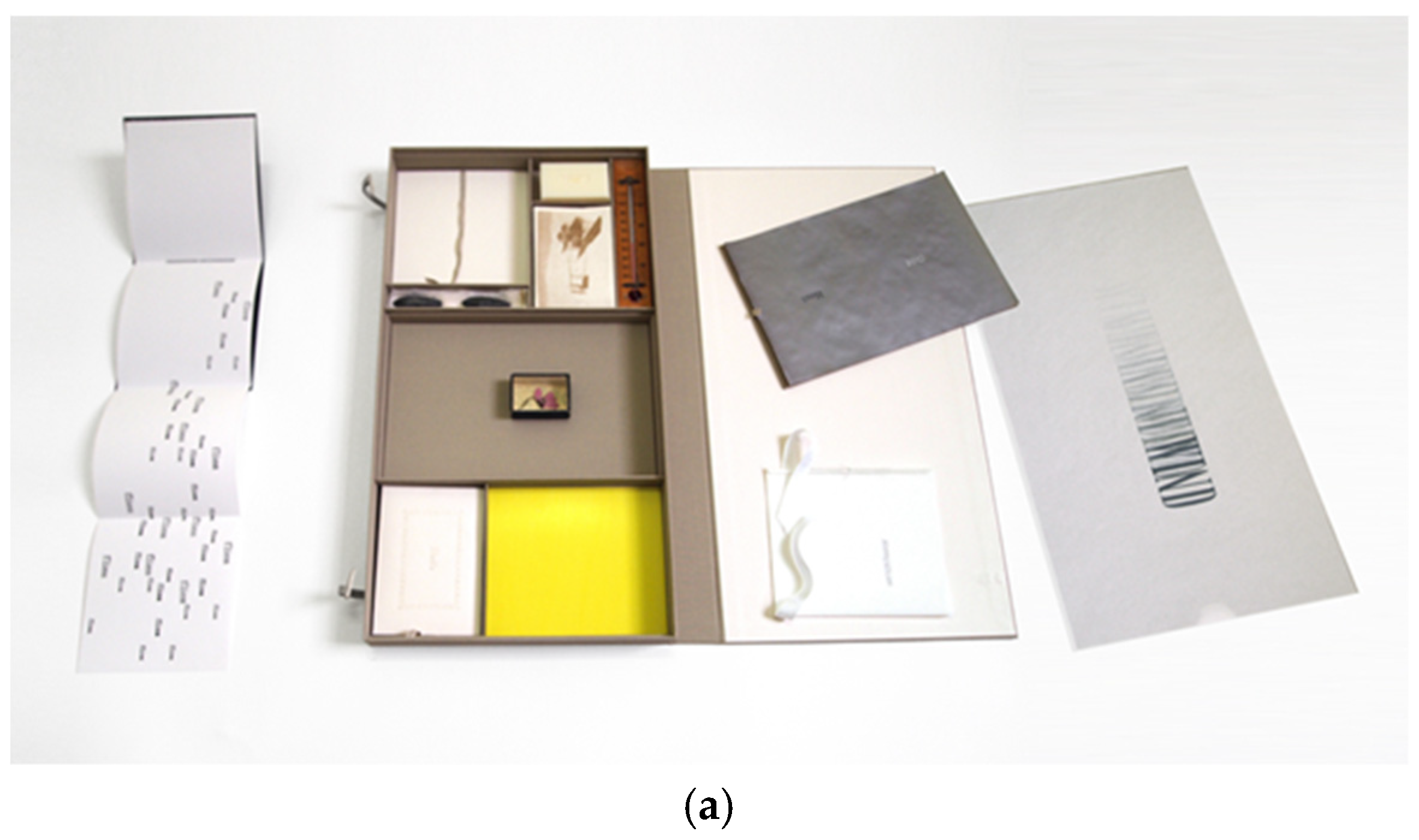

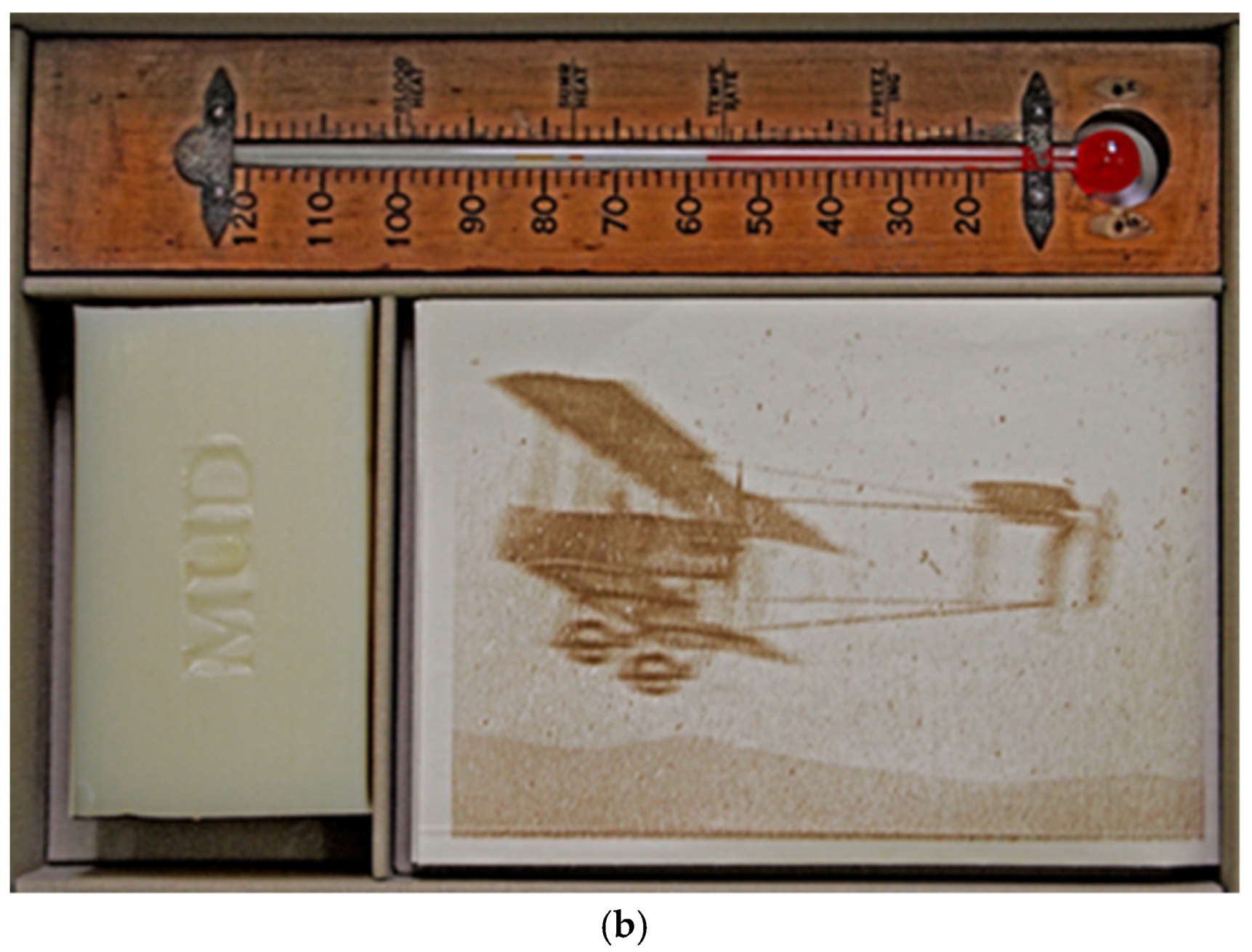

The presentation of artists’ books in two separate exhibitions highlighted the importance of the experiential nature of artists’ books and how they function as artworks. The first instance was the inclusion of a series of publications by Aleister Crowley in the exhibition Luz Negra5 at the CCCB in Barcelona and the second, the display of a book by Susie Wilson in Reflections of Camp Life at the Scottish Women’s Hospitals6, at Surgeon’s Hall in Edinburgh. The inclusion of Crowley’s and Wilson’s books in the exhibitions evidenced the growing presence of artists’ books within exhibitions but also the limitations inherent in their incorporation into the museum machine. The books were imprisoned behind glass. In the case of Crowley’s publications, only the covers were accessible, the viewer left to guess at their content. Unlike David Steir’s Boundless from 1983 (Drucker 1995, p. 177), where the viewer’s access to the content is intentionally impeded, the wire-binding of the circular book entirely enclosing its circumferences, in Luz Negra, it was the glass case that silenced the content. The books could not be manipulated and could only be judged by their covers. This resistance to formal display was equally evident in the presentation of Susie Wilson’s book Discomforts (2018, Figure 1a,b), although tempered in this instance as the book, a box, was displayed open. But within the glass cabinet, the contents of the box, neatly divided into sections, which held a thermometer, a cyclamen, a bar of soap, lead weights, images and various printed booklets, lay still. The invitingly translucent layers of Shoji paper, the smooth silkiness of the engraved soap or the letter pressed booklets, all lay tantalisingly out of reach. The narrative proposed by the artist, the imagined rhythm of the recipient’s experience as the fabric, flower, soapy, lead or paper elements are unpacked was paused, or could only be imagined. The contents of the leaflets, like Crawley’s publications, were left blind, the objects reduced to a curious still life within the museum cabinet.

Figure 1.

(a) Wilson, S. Discomforts, 2018. Letterpress, plate lithography on paper, soap, newsprint, Shoji paper with mixed media objects, Edition 1 of 2. (Photo: Paul Keir). (b) Wilson, S. Discomforts (Detail) Imprinted soap, thermometer, photolithographic print (Photo: Paul Keir).

The museum display in both these instances impeded access to the sensorial experience of reading artists’ books, where the materiality of a page, or an object, forms part of the transmission of ideas. A problem identified by Clive Phillpot, the curator and director of the library at MOMA from 1977 to 1994, when he argues, “Exhibiting books that normally exist as mobile hand-held devices, as one-opening-objects under glass, is clearly problematic. Perhaps, ideally, one should acquire at least two copies of every publication represented in a collection? This would ensure that one copy could remain closed (or be open at only one place) for long periods of time, while the other copy can be allowed to deteriorate through frequent use”7. Other solutions have been to film the reader’s experience, as in the video of Nosaltres i els agermanats (Perejaume et al. 2012)8 by Perejaume, Enric Cassases and Pascal Comelade, in which the viewer watches a choreographed interaction with the pages to the soundtrack of Comelade’s score incorporated in a vinyl record within the book. Others use scanned or photographed digital facsimiles. But on the screen many important aspects of the reader’s experience are altered for, at their best, artists’ books offer complex narratives that can function on many levels. This occurs within a very human scale and the specific space–time activated by the viewer.

This experiential nature of artists’ books forms part of their power or agency as a ‘technology of enchantment’ (Gell 1992). In his consideration of the network of social relations in which an artwork is embedded, the anthropologist Alfred Gell defines the art object as a technology of enchantment, a device “for securing the acquiescence of individuals in the network of intentionalities in which they are enmeshed” (Gell 1992, p. 43). He proposes art objects as agents of thought-control (Gell 1998, pp. 44–46) and identifies the technical virtuosity and our uncertainty about how the art object is thought to have come into the world as the source of their power. The viewer or, to use Gell’s terminology, the ‘recipient’ infers or ‘abducts’ the identity, actions, or intentions of those who have created the work of art. The value of the artwork is therefore proportional to its ‘cognitive stickiness’ (Gell 1998, p. 86): the difficulty it provokes in the beholder in unravelling the intentions of the agent. In artists’ books, these intentions can be embedded in the words, images and objects and surfaces of the book, but also within the sensorial experience of the reading. They are mobile agents of enchantment.

Their transportability means they could be compared to the portable documents or ‘inscriptions’ generated within the scientific community (Latour 1999). Inscriptions Bruno Latour identifies as including “… all the types of transformation through which an entity becomes materialised into a sign, an archive, a document, a piece of paper, a trace” (Latour 1999, p. 306). They encompass all forms of register or written documents made by scientists. They are designed to transmit information or ideas corresponding to an entity within the science nexus. Like artists’ books, scientific ‘inscriptions’ can be understood as the end product of a series of operations designed to mobilize or promote an idea, which may or may not be aesthetic objects. Inscriptions are designed to facilitate the comparison, reproduction and quantification of the information they contain. They are instrumental in what Latour describes as the “cascade of ever simplified inscriptions” that mobilises opinion (Latour 1986, p. 16). Where scientific ‘inscriptions’ could be said to differ from artists’ books, however, is in their aim to present symbols that are referred to directly and univocally. They are designed as objects that “have the properties of being mobile but also immutable, presentable, readable and combinable with one another” (Latour 1986, p. 6). Scientific inscriptions seek a transparent view, one that is syntactically and semantically clear. They are designed, as tools of persuasion, to ensure intersubjective agreement rather than the ‘cognitive stickiness’, which Gell points to as intrinsic to artworks. Artists’ books share some of the qualities of Latour’s ‘immutable mobiles’ (Latour 1986, p. 7), as they are easily transportable and can be readily combined and consulted on a flat surface. The reinterpretation of Stéphane Mallarmé’s Un coup de Dés in later artists’ books by artists such as Broodthaers and Michalis Pichler could even be identified as a ‘cascade of simplified inscriptions’. For in Marcel Broodthaers’ book, with the same title, from 1969, the layout of the original texts is blocked out in black and printed on transparent paper, reducing Mallarmé’s poem to a form of binary code, whereas in Pichler’s later interpretation, from 2019, the blocks of text are cut away by laser to resemble the holes of a Pianola score. But artists’ books diverge from the ‘immutable mobiles’ of science in their mutability. They act as technologies of enchantment rather than persuasion. They have a syntactic density (Goodman 1978, pp. 67–68) and seek a multiplicity of interpretations or, as Gell proposes, the “abduction of agency” (Gell 1992). The current proliferation of artists’ books is due to their power as mobile tools of enchantment, through their direct engagement with the recipient, and their mutability. They function as ‘mutable mobiles’.

With artists’ books, this engagement is ideally visual, haptic and temporal, as exemplified in the case of the display of Wilson’s and Crawley’s books. Artists’ books invite the recipient to read with their eyes, ears and fingers. The turning of a page or unpacking of box can incorporate dissonant textures, weights and sounds, and these shifts suggest rather than point to an established or fixed narrative. This reading experience differs from the swipe of a finger on a tablet screen or keyboard or the almost mechanical turning of the page of a paperback. I should clarify here that while some artists’ books are performatic by nature and others take advantage of the possibilities of digital platforms, in this instance, I am interested specifically in artists’ books that are made out of tangible materials such as paper, fabric, glass, leather, etc. I believe it is the materiality of artists’ books that helps to trigger sensorial readings that go beyond the written word. The different materials allow the artist’s intentions to be transmitted through sight, sound, touch and smell, making the experience of the object haptic and cognitive. In the hand, an artist’s book establishes a unique space for the receiver. Some books, such as Barbara Ryan’s Walpurgisnächte Odour (Ryan 2018)10, published by Wild Pansy Press, amplify this aspect. Documenting transmissions the artist ‘received’ from particular sites in Berlin and Brandenburg, the book depicts characters from both the corporeal world and the recorded ‘ghost frequencies’ of Walpurgisnächte. It makes the odours manifest through odour pouches, or in the fourth series with perfume bottles, the whole creating a synaesthetic translation of the real and fictional. Others opt for simpler solutions, maintaining the feel and smell of glossy magazines from the fifties, but subverting the graphic language, through editing and abstraction, as in L’architecture d’Aujourd’hui by Giménez (2015)11. Idiosyncratic by nature, artists’ books create unique, new spaces for communication on a very human scale. The recipient activates the artistic device, offering a return to the sense of discovery implicit in young children’s pop-up books or finger-feel narratives. The stories they tell are not necessarily linear, as in the trilogy of cross-referring narratives in the foldable book, El fin del mundo by Anna Andorrà, Mariam Koraichi and Mònica Ruiz (Figure 2)12, where three narrative threads unfold, causing the initial hexagonal format of the book to expand into a rich labyrinth of interlinking visuals and text. Conversely, in Julie Chen’s True to Life (Chen 2005), it is the chance combinations of text and image created through the manipulation of the sliding parts in the rectangular structure, which is part tablet, part puzzle. The loss of the interplay of words, forms and narrative sequences within a museum cabinet means the richness of these publications is muffled and points to why alternative routes have been sought for their presentation and exchange.

Figure 2.

Andorrà, A, Koriachi, M., Ruíz, M. El fin del mundo, 2019, Edition of 6, Lithography, Linocut and Embossing on Arches, Book closed 12 cm × 14 cm × 1.5 cm) (Photo: Z46).

3. Alternative Platforms for Documentation and Distribution

The need to find new pathways for dissemination is present throughout the history of artists’ books. It was suggested in Ulises Carrión’s manifesto but became paramount in the platforms he went on to establish for the presentation and consultation of artists’ books. For Carrión, as Borja-Villel suggests, the book became a “catalyst for experimenting with the structures that govern the relations between texts, objects, and images, and for trying out new avenues and forms of authorship and artist-reader participation” (Schraenen 2016, p. 3). In 1975, he opened the bookshop–gallery Other Books & So at Herengracht 227, in Amsterdam. Numerous artists, such as Sol LeWitt, Dieter Roth, herman de vries or Stanley Brouwn, had previously distributed their own work as publications and in 1974, the artist trio, General Idea, established Art Metropole, which they conceived as an alternative distribution centre and archive (Smith 2016, p. 10). Carrión’s Other Books and So was similar to Art Metropole, in that it was a platform directed at the presentation, production and distribution of books that were art and not literature, or as the flyer announced; “non books, anti books, pseudo books, quasi books, concrete books, visual books, conceptual books, structural books, project books, statements books, instruction books” (Schraenen 2016, p. 17). The style of presentation invited the visitor to look at and make contact with the books, most of which were laid out flat on tables and shelves. Despite its short life, Other Books & So remains a paradigm in the history of artists’ books and publications for its modus operandi in presenting and promoting artists’ books. Its founding can be seen within the context of that time, when many artists took responsibility for the distribution of their works. These initiatives, as Schraenen (2016, p. 18) suggests, “were involved in the construction of an international network dedicated to the exchange of works and ideas.” By establishing an informal space for exchange and consultation, Carrión’s bookshop and subsequent archive were conceived as artworks and as “a memory system that eluded the interest of the traditional art circuit yet would be capable of evoking countless memories for numerous people” (Schraenen 2016, p. 19). The short lifespan of Carrión’s endeavours, truncated by his premature death, pays testimony to the economic difficulties of maintaining a permanent space dedicated to the promotion of artists’ publications, a situation echoed by the demise of other enterprises dedicated to artists’ books such as the Hardware Gallery13 in London (1986–2001) or more recently Multiplos14 in Barcelona (2011–2018). Some spaces do prevail, however, like Art Metropole15 and Boekie Woekie16 established in Amsterdam in 1986, while others, such as Motto17, diversify, distributing artists’ books alongside magazines and general art books. Nevertheless, it is larger platforms like the non-profit organisation Printed Matter, Inc.18, dedicated to the ‘dissemination, understanding and appreciation of artists’ books’, established in New York in 1976 or the imprint Book Works19 established in 1984 in London that publishes and promotes artists’ publications, which have thrived. Their hybrid nature and diversification undoubtedly facilitate their prolonged success. Nevertheless, the costs and difficulties of maintaining a permanent physical space, coupled perhaps with the waning circulation of mail art, have propitiated the development of online platforms, pop-up shops and, in particular, the proliferation of fairs dedicated to artists’ publications.

4. Book Fairs as Nodes for Dialogue and the Generation of Community

These events make artists’ books available to many different kinds of audience. They adhere to a fairly standard format, with a community of imprints and artists gathering to present their publications over one or two days, often complemented by workshops, talks and performances. They function as commercial venues but also as spaces for communication. At fairs, recipients can access, purchase and debate the contents of the books. The informality of the setting makes the books and their makers accessible to recipients and makers. Books are handled, discussed, opened and closed within an environment of debate, curiosity and laughter. Deluxe artists’ books rub shoulders with fanzines, flipbooks, sculptural books, or other more humble limited editions. Readers and makers gain an understanding of the reception and fabrication of an artist’s book. Narratives are shared and expanded through the reading of the books and the dialogues established with those presenting them (Figure 3a,b).

Figure 3.

(a) Zejun Yao introducing visually impaired visitors to artists’ books at PAGES, The Tetley, Leeds, UK, 2019 (Photo: Jules Lister/The Tetley). (b) Artist/maker/publisher in conversation with visitors to PAGES, The Tetley, Leeds, UK, 2019 (Photo: Jules Lister/The Tetley).

Fairs offer the kind of exchange envisaged by Carrión with his bookshop, but within an evolving international network. The pop-up communities established, like the books presented, blur geographical boundaries. As meeting points, the fairs stimulate new interpretations and collaborations. They function as venues of commerce but also as nodes of exchange. The final hours of such book fairs often give rise to book swapping between makers and imprints (Pichler 2016, p. 207). The importance of this exchange, rather than the profitability of such events, has possibly contributed to this growth in the number of fairs dedicated to artists’ books. Their multiplication, since the early editions of PAGES in Leeds (1997) or Printed Matter’s New York Art Book Fair (2004) is evident, with the number of institutional fairs such as BABE, Arts Llibris, Singapore Art Book Fair or Miss Read, as well as Frankfurt, London or New York but is also visible in the mushrooming of smaller events, such as Gutter Fest and PRINT.ed20 in Barcelona, Printing Plant Art Book Fair in Amsterdam, Libros Mutantes in Madrid or Volumes in Zurich21.

5. Conclusions

Proffered across tables, artists’ books can be activated, their potency as ‘mutable mobiles’ evident in the discussions that arise as pages are turned. As Drucker stated in 1995, “paper may be precious, printing technologies transform, and production methods expand—but the potential of the book as a creative form will remain available for exploration” (Drucker 1995, p. 364). In 2019, there are no limits to what artists’ books can be and no rules governing their fabrication. Their buoyant existence is evident both within the mainstream art world, one example being the presentation of the third exhibition dedicated to publications Muestreo#3. Anti-books at MACBA’s Centre for Documentation in Barcelona and the accompanying series of talks El que pot un llibre (What a book can do)22 in autumn 2019, and beyond it. Books are visible in bookshops, online platforms and book fairs. They remain intriguing interlopers, or as Lippard suggested, “a significant subcurrent beneath the artworld mainstream that threatens to introduce blood, sweat, and tears to the flow of liquitex, bronze, and bubbly” (Lippard 1985, p. 56). The hybrid nature of artists’ books, their “multisensory, experiential, and culturally embedded aspects” (Burkhart 2006, p. 248) enable them to act as counterpoints to the omnipresent social networks and forms of communication that digital media offer, while also offering a vehicle for highlighting the poetry embedded in them, as in the work of Kenneth Goldsmith23. They provide alternative avenues of exploration for both makers and readers. Their resistance to definition and passive display and their ability to act as catalysts for other forms of communication and reading point to the possibility of artists’ books prevailing as mutable mobiles for the foreseeable future.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge that all the images included within this article are published thanks to the kind permission of the photographers and artists concerned. The experience of participating as an artist in fairs such as PAGES, All Inked Up and Arts Llibris, and organizing the fair PRINTed at EINA, Espai Barra de Ferro, Barcelona have informed aspects of the article and the choice of certain examples.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Andorrà, Anna, Mariam Koraichi, and Mònica Ruiz. 2019. El fin del mundo. Barcelona: Espai Barra de Ferro. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhart, Anne L. 2006. “Mongrel Nature:” A Consideration of Artists’ Books and Their Implications for Art Education. Studies in Art Education 47: 248–68. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25475784 (accessed on 15 August 2019). [CrossRef]

- Carrión, Ulises. 1975. El Nuevo Arte de Hacer Libros. Available online: https://monoskop.org/images/f/f6/Carrion_Ulises_1975_El_arte_nuevo_de_hacer_libros.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2019).

- Chen, Julie. 2005. True to Life. Flying Fish Press: Available online: http://www.flyingfishpress.com/booksinprint/truetolife.html (accessed on 15 August 2019).

- Drucker, Johanna. 1995. The Century of Artists’ Books. New York: Granary Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gell, Alfred. 1992. The Technology of Enchantment and the Enchantment of Technology. In Anthropology, Art, and Aesthetics. Edited by Jeremy Coote. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gell, Alfred. 1998. Art and Agency, An Anthropological Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, Annette. 2016. Publishing as Artistic Practice. Edited by Annette Gilbert. Berlin: Sternberg Press, pp. 6–39. [Google Scholar]

- Giménez, Regina. 2015. L’architecture d’Ajourd’hui. Barcelona: Los Cinco Delfines. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, Nelson. 1978. Ways of Worldmaking. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Hannula, Mika. 2009. Catch me if you can: Chances and Challenges of Artistic Research. Art & Research, A Journal of Ideas, Contexts and Methods 2. Available online: http://www.artandresearch.org.uk/v2n2/pdfs/hannula1.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2019).

- Higgins, Dick. 1966. lntermedia. New York: Something Else Newsletter, vol. 1, Available online: http://www.primaryinformation.org/something-else-press-newsletters-1966-83/ (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- Latour, Bruno. 1986. Visualisation and Cognition: Drawing Things Together. In Knowledge and Society Studies in the Sociology of Culture Past and Present. Edited by Henrika Kuklick. Stamford: Jai Press, vol. 6, pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, Bruno. 1999. Pandora’s Hope. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lippard, Lucy R. 1985. Conspicuous Consumption, New Artists books. In Artists Books, A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook. Edited by Joan Lyons. Rochester: Visual Studies Press Workshop Press, pp. 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Maroto, David, and Clive Phillpot. 2017. Interview with Clive Phillpot. SOBRE, 148–57, 05/2017–04/2018. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325533191_Interview_with_Clive_Phillpot (accessed on 1 June 2019).

- Perejaume, Enric Cassases, and Pascal Comelade. 2012. Nosaltres i els Agermanats. Barcelona: Tinta Invisible. [Google Scholar]

- Phillpot, Clive. 1982. Books, Bookworks, Book Objects, Artists’ Books. Artforum 20: 77. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, Barbara. 2018. Walpurgisnächte. Leeds: Wild Pansy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pichler, Michalis. 2016. Book Swapping & Seriosity Dummies from Fragments: Life and Opinions of a Real Existing Artist. In Publishing as Artistic Practice. Edited by Annette Gilbert. Berlin: Sternberg Press, pp. 206–9. [Google Scholar]

- Schraenen, Guy. 2016. Ulises Carrión, Querido Lector. No Lea. (Exhibition Catalogue). Madrid: MNCARS, Available online: https://www.museoreinasofia.es/sites/default/files/publicaciones/ulises_carrion_ingles_web_15-11-16.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2019).

- Smith, Sarah E. K. 2016. General Idea, Life and Work. Toronto: Art Canada Institute. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Even the punctuation of the term artist’s book mutates. In some cases, the apostrophe sits before, in others, it follows the ‘s’, and in others it disappears completely. Here, I use the punctuation artist’s book when referring to a singular publication and switch to the plural of artists’ books when describing a plurality of publications or instances when the book has been fabricated by more than one artist. |

| 2 | As evidenced by the many artists’ books collections in the USA. See: https://www.andrew.cmu.edu/user/md2z/ArtistsBooksDirectory/ArtistsBookIndex.html In Europe, there are examples such as the Manchester Metropolitan University, https://mmuspecialcollections.wordpress.com/books-2/artists-books/ the V&A http://www.vam.ac.uk/page/a/artists-books/ or the Centre for Artist’s Publications, Bremen, which forms part of the Weserburg Museum für Moderne Kunst. This unique collection of artists’ books originated in the Archive of Small Press and Communications established by the international curator, publisher and adviser, Guy Schraenen in Antwerp. See: https://www.guyschraenenediteur.com/a-s-p-c/ and https://weserburg.de/en. |

| 3 | Phillpot (1982) Diagram in “Books, Bookworks, Book Objects, Artists’ Books”, Artforum, vol. 20. |

| 4 | Carrión (1975) “The New Art of Making Books”, published in Plural (literary supplement of the newspaper Excélsior), México, Feb 1975. |

| 5 | Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona, 16 May 2018–21 October 2018. Luz Negra, Tradiciones secretas en el arte desde los años cincuenta. See: https://www.cccb.org/es/exposiciones/Ficha/la-luz-negra/228235. |

| 6 | Surgeon’s Hall Museum, 10 November 2018–30 March 2019. Field Notes: Reflections of Camp Life at the Scottish Women’s Hospitals. |

| 7 | Maroto and Phillpot (2017) “Interview with Clive Phillpot.” SOBRE No. 3, pp. 148–57, May 2017–April 2018, (retrieved: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325533191_Interview_with_Clive_Phillpot, 1 June 2019). |

| 8 | Perejaume et al. (2012) Nosaltres i els agermanats, Barcelona: Tinta Invisible, (retrieved: https://www.gravat.com/ca/works/nosaltres-i-els-agermanats). |

| 9 | |

| 10 | |

| 11 | Giménez (2015) L’architecture d’Ajourd’hui, Barcelona. Published by Enric Farrés Duran, within the editorial project Los Cinco Delfines. See: http://latamuda.com/regina-gimenez-larchitecture-daujourdhui. |

| 12 | Andorrà et al. (2019). El fin del mundo, Barcelona, Espai Barra de Ferro. See: https://barradeferro.wordpress.com/2019/05/10/el-fin-del-mundo/. |

| 13 | Dedicated to contemporary printmaking, the gallery/bookstore, established in 1986, before moving in 1993 to Highgate, Hardware was a forerunner in the promotion of artists books in the UK. See: http://www.deirdrekellyartistbookcollection.com/hardware-gallery. |

| 14 | Founded by Anna Pahissa, Multiplos was situated in various locations in Barcelona before its demise at the end of 2017. Lleó, R. “Interview with Anna Pahissa”, Barcelona, A*DESK, 25 April 2016, https://a-desk.org/en/magazine/interview-with-anna-pahissa/ (accessed on 14 August 2019). |

| 15 | The extent of the endeavours of Art Metropole, set up by General Idea, (AA Bronson, Felix Partz and Jorge Zontal) is evident in the collection of 13,000 publications they transferred in 1997 to the National Gallery of Canada. For further information of Art Metropole’s current activites and archive. See: https://artmetropole.com/. |

| 16 | Boekie Woekie was originally envisaged by its six founders as a shop for their own publications. After four decades, and having relocated, it now stocks around 7000 self-published or small press books. See https://boekiewoekie.com/pages/about-boekie-woekie. |

| 17 | |

| 18 | |

| 19 | |

| 20 | The fair PRINTed dedicated to singular publications, held annually at EINA, Espai Barra de Ferro in Barcelona, was established by Enric Mas and the author in 2015. |

| 21 | The list is too long to itemise here; in Spain alone, the last seven years have seen the appearance of fairs such as Gutter Fest, Arts Libris, PRINTed in Barcelona and Libros Mutantes, MasQueLibros in Madrid, as well as Librarte in Castilla y Leon and Fala in Alicante, to name only a few. The breadth of the smorgasbord of artists’ book fairs taking place across the globe is made visible by the lists published by Das Kunstbuch, see: https://daskunstbuch.at/art-book-fairs-2018/, Printed Matter, see: https://www.printedmatter.org/services/the-bulletin/book-and-zine-fairs or Stencil, see: http://stencil.wiki/fairs. |

| 22 | MACBA, Barcelona, Muestreo #3. See: https://www.macba.cat/es/el-que-pot-un-llibre. |

| 23 | Louisiana Channel, Malinovski, P. Interview with Kenneth Goldsmith, Assume no Readership, New York, 2014, retrieved from https://channel.louisiana.dk/video/kenneth-goldsmith-assume-no-readership. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).