Singing to Emmanuel: The Wall Paintings of Sant Miquel in Terrassa and the 6th Century Artistic Reception of Byzantium in the Western Mediterranean

Abstract

:1. Introduction

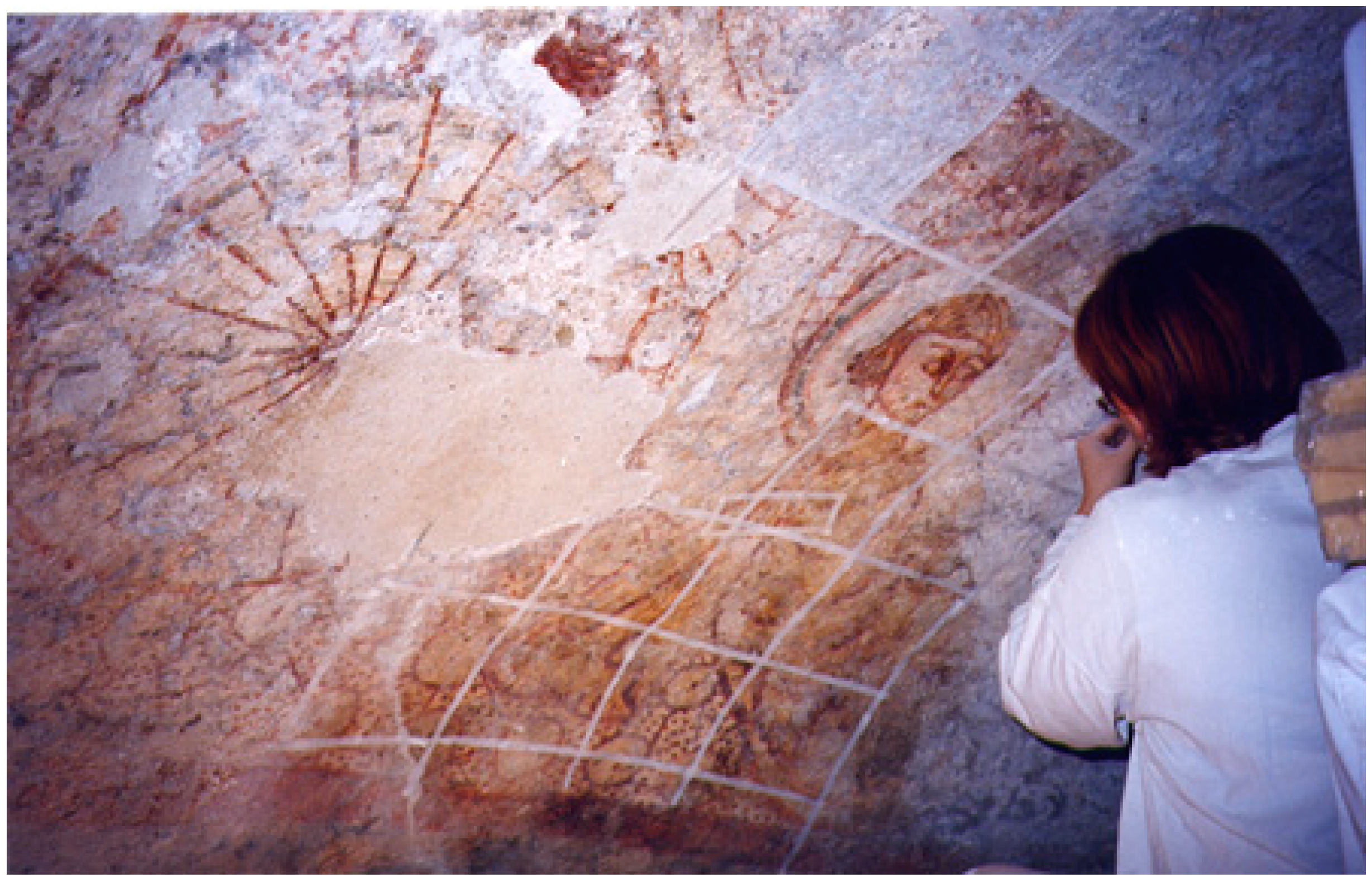

The technique’s identity, as well as some of the ornamental themes, compel us to believe that the two paintings [Santa Maria and Sant Miquel] should be considered to be contemporaries and perhaps to be the work of the same hand.

2. The Creation of the Bishopric of Egara

3. The Recovery of a Forgotten Beauty: Discovery and First Studies of the Paintings

4. Art, Music, and Liturgy at Sant Miquel

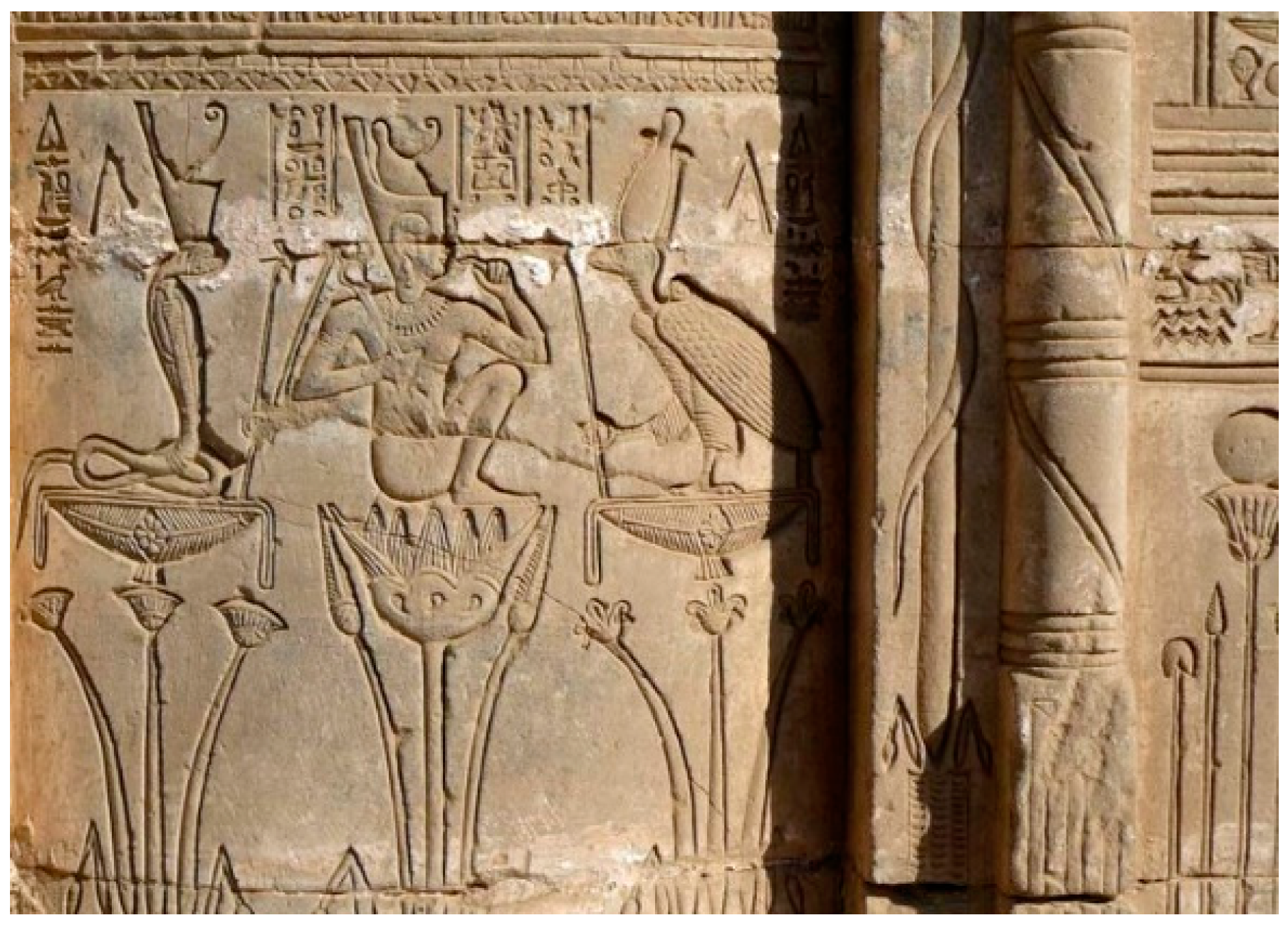

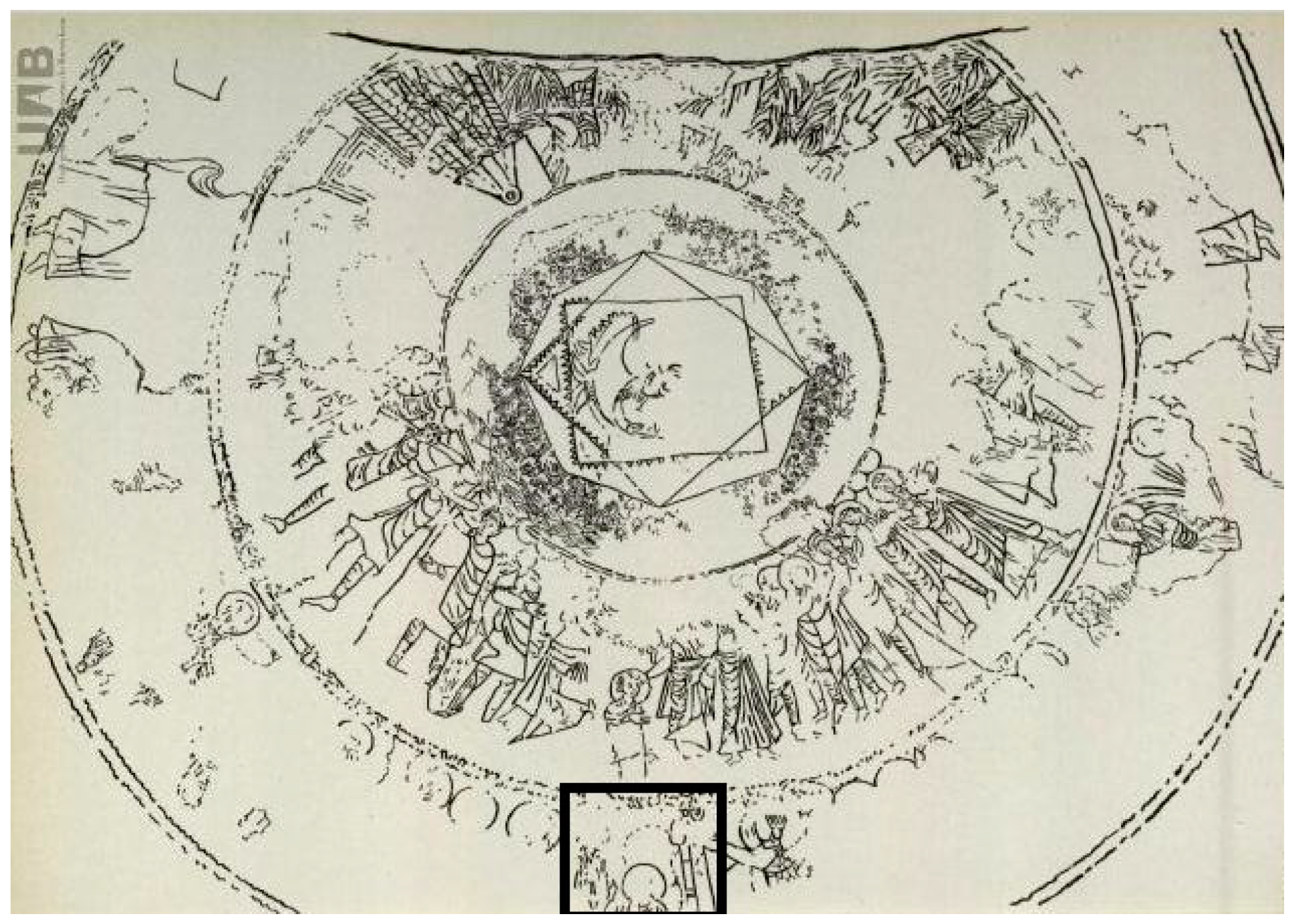

4.1. A Synoptic Theophany

4.2. Theophany as Presence

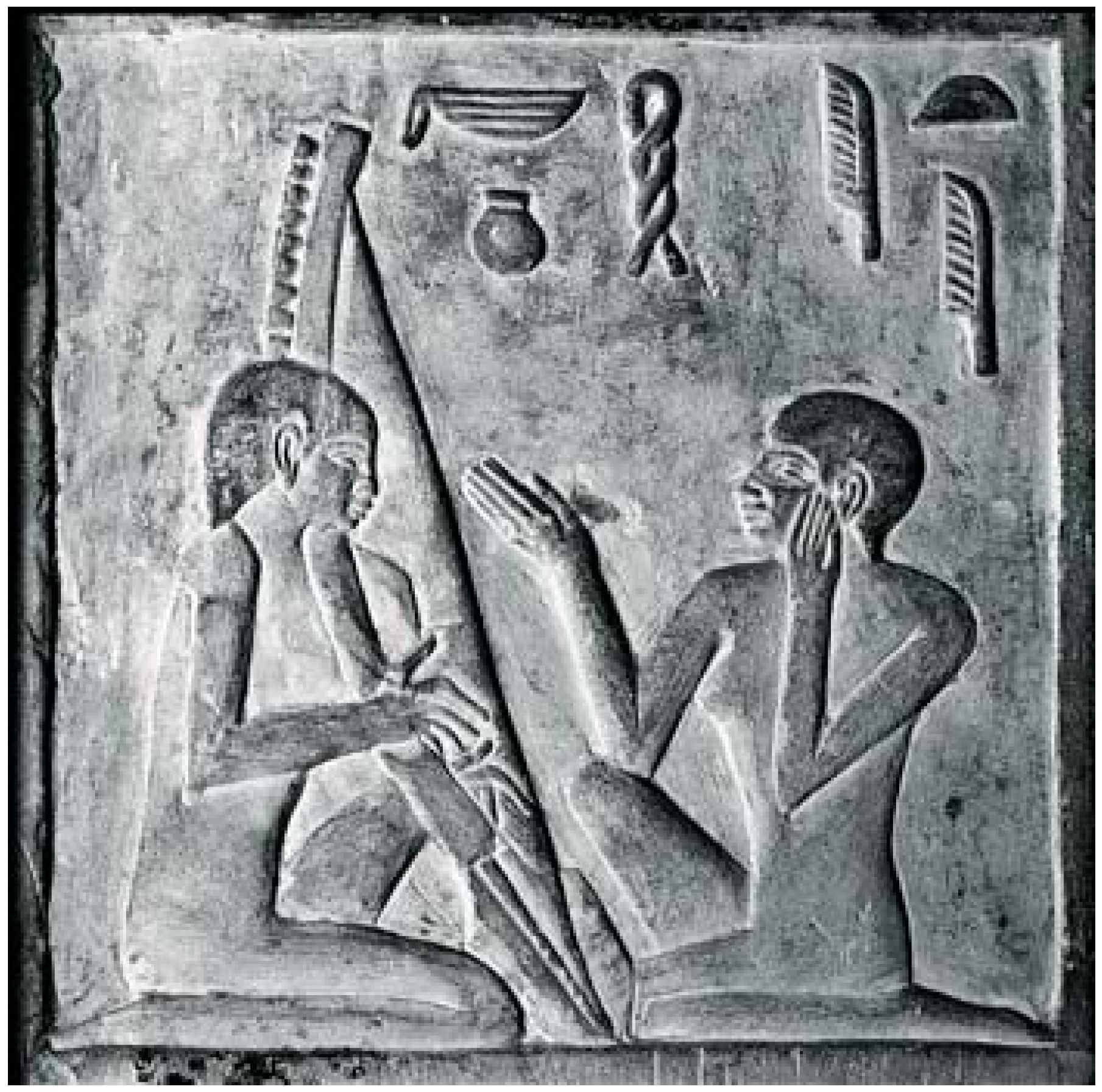

4.3. Singing to Christ Emmanuel

5. A Program against Arian Heresy?

The virgin will conceive and give birth to a son, and they will call him Emmanuel (which means “God with us).

And as for many years, the threatening heresy did not permit the celebration of the council of the Catholic Church, God, who was pleased to have extirpated the aforementioned heresy from our midst, admonished us to restore the ecclesiastic institutions according to the ancient traditions.

If any bishop or presbyter or deacon of any bishop engages in a heretical opinion and would be excommunicated for this reason, no bishop shall admit him in his Communion if he does not satisfy all those present before a common assembly with a confession of his faith. This same condition is established for the lay faithful in case they would be accused of heretical opinions.

Haec hic beata Theclavirgo Xρι(στσυ), ei patria Aegypt(us).Vixit ann(is) LXXVII, ut meruitin pace requievit D(omi)ni (hedera).

Stephanus Alexandrinus in honore Dei et omnius sanctorum die VIII idus Apriles anno tertio ordinationis eius cum suis sub pontificatu Georgii episcopii sanctissimi. Sigillum hic esto.

6. Chronology

6.1. Archaeological Verdict

6.2. The Verdict of the Restorers

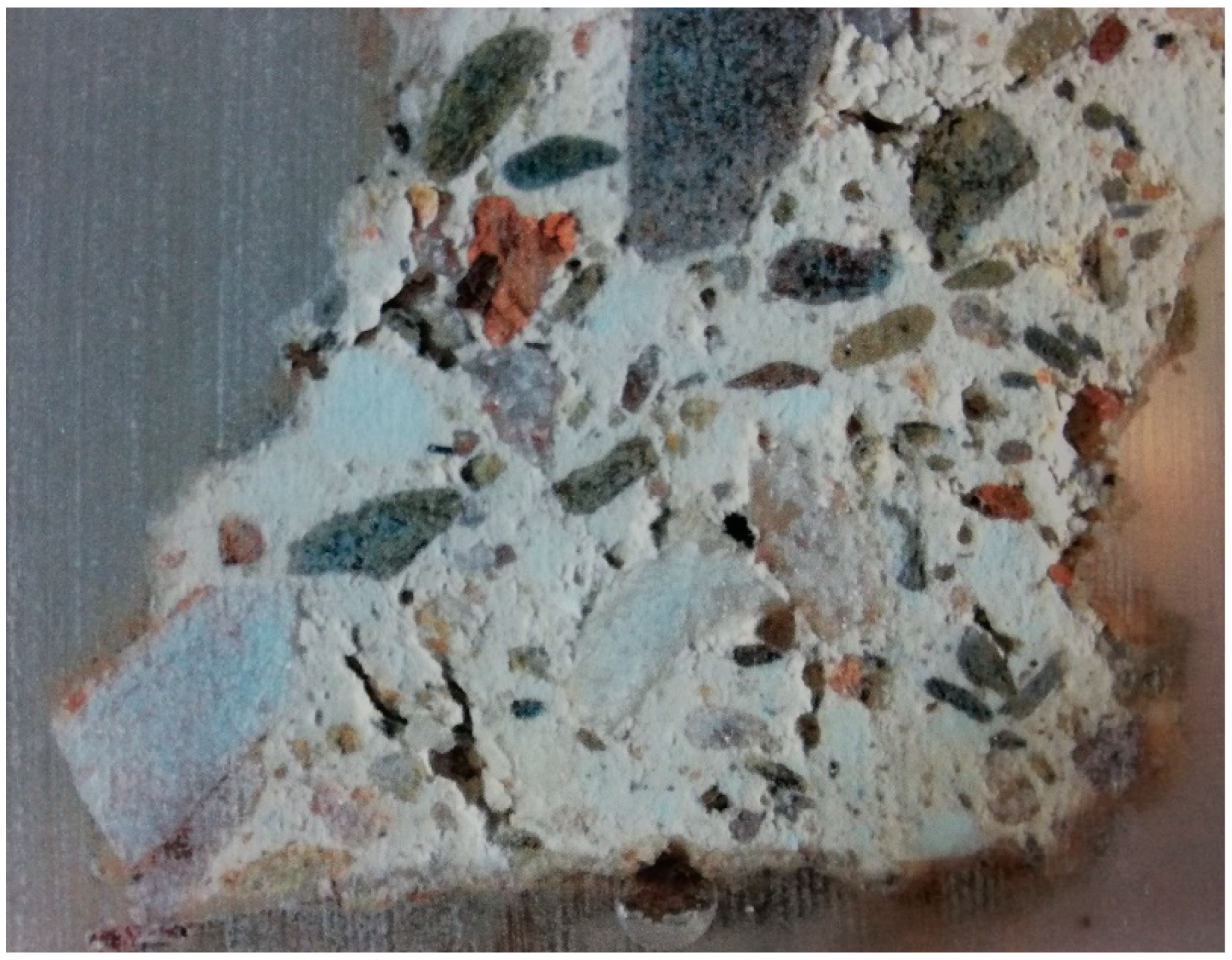

Two very similar types of mortar have been detected between them: the one used for joints and the other from the intonaco layer (…). The composition of the lime studied under the electron microscope has defined the type of material: calcium carbonate (…). The compositional uniformity of the materials confirms that the different strata correspond to the same time period and are contemporary to the construction of the cupola.

In light of the obtained data, it is perfectly possible to contextualize the time periods of the paintings to be contemporary with the construction of the cupola.

6.3. The Verdict of the Epigraphists

7. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ainaud de Lasarte, Joan. 1959. Terrassa. Les églises d’Égara. In Congrès Archéologique de France “Catalogne”, CXVIIe Session. Paris: Société Française d’Archéologie, pp. 189–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ainaud de Lasarte, Joan. 1976. Los templos visigótico-románicos de Tarrasa. Madrid: Editora Nacional. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrós i Monsonís, Jordi. 1980. Les obres de restauració de l’antiga seu del bisbat d’Ègara. Quaderns d’Estudis Medievals 2: 101–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrós i Monsonís, Jordi. 1982a. Obres de restauració dels edificis de la seu de l’antic bisbat d’Ègara. Baptisteri de Sant Miquel. Quaderns d’Estudis Medievals 8: 491–507. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrós i Monsonís, Jordi. 1982b. Obres de restauració dels edificis de la seu de l’antic bisbat d’Ègara. Església de Santa Maria. Quaderns d’Estudis Medievals 10: 583–606. [Google Scholar]

- Amengual i Batlle, Josep. 2013. Tarragona, Cartagena, Elx i Toledo. Metropolitans i vicaris papals en el segle VI. Revista Catalana de Teologia 38: 547–90. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, William. 2007. Menas Flasks in the West. Pilgrimage and Trade at the End of Antiquity. Ancient West & East 6: 221–43. [Google Scholar]

- ARCOR. 2001. Sant Miquel de Terrassa. Documentació de l’obra i de la restauració, juny–juliol 2001. Terrassa: Arcor. Taller. Estudi. Conservació i Restauració de Pintura. [Google Scholar]

- ARCOR. 2002. Sant Miquel de Terrassa. Documentació de la restauració d’octubre 2001 a març 2002 i noves aportacions a la documentació de l’obra. Terrassa: Arcor. Taller. Estudi. Conservació i Restauració de Pintura. [Google Scholar]

- Arias Abellan, Carmen. 2000. Itinerarios Latinos a Jerusalén y al Oriente Cristiano. Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla. [Google Scholar]

- Bangert, Susanne. 2006. Menas ampullae, a case study of long-distance contacts. Reading Medieval Studies XXXII: 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bango Torviso, Isidro. 1997. La vieja liturgia hispana y la interpretación funcional del templo prerrománico. In VII Semana de Estudios Medievales (Nájera, 29 de julio al 2 de agosto de 1996). Edited by José Ignacio de la Iglesia Duarte. Nájera: Instituto de Estudios Riojanos, pp. 61–120. [Google Scholar]

- Barral i Altet, Xavier. 1981. L’art pre-romànic a Catalunya. Segles IX-X. Barcelona: Edicions 62. [Google Scholar]

- Bäumer, Suitbert. 1905. Geschichte des Breviers, French ed. Freiburg im Breisgau and Paris: Herder. First published 1895. [Google Scholar]

- Belting-Ihm, Christa. 1960. Die Programme der christlichen Apsismalerei vom 4. Jahrhundert bis zur Mitte des 8. Jahrhunderts. Wiesbaden: Forschungen zur Kunstgeschichte und christlichen Archäologie, pp. 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Belting-Ihm, Christa. 1989. Theophanic Images of Divine Majesty in Early Medieval Italian Church Decoration. In Italian Church decoration of the Middle Ages and Early Renaissance. Functions, Forms and Regional Tradition. Edited by William Tronzo. Bologna: Nuova Alfa, pp. 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrán de Heredia, Júlia. 2019. La Barcelona visigoda: un puente entre dos mundos. La basílica dels Sants màrtirs Just i Pastor: de la ciudad romana a la ciudad altomedieval. Barcelona: Ateneu Universitari Sant Pacià. [Google Scholar]

- Blázquez Martínez, José María. 1967. Posible origen africano del cristianismo español. Archivo Español de Arqueología 40: 30–50. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker, Leslie. 2009. Gesture in Byzantium. In The Politics of Gesture: Historical Perspectives. Edited by Michael Braddick. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 36–56. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano i Tresserra, Anna, Imma Vilamala, and Antoni González Moreno-Navarro. 1993. Les restauracions de les esglésies de Sant Pere de Terrassa. L’actuació del Servei de Catalogació i Conservació de Monuments de la Diputació de Barcelona, 1915–1951, Monografies 3. Barcelona: Diputació de Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- Christe, Yves. 1969. Les grands portails romans. Études sur l’iconologie des théophanies romanes. Genéve: Études et documents públiés par les Instituts d’Histoire de la Faculté de Lettres de l’Université de Genève, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Cirici i Pellicer, Alexandre. 1945. Contribución al estudio de las Iglesias de Terrassa. Ampurias VII–VIII: 215–32. [Google Scholar]

- Clédat, Jean. 1904. Le monastère et la nécropole de Baouît, Tome I, Fascicules 1-2. Le Caire: Mémories publiés par les membres de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale du Caire, XII. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Walter William Spencer, and José Ricart Gudiol. 1950. Ars Hispaniae I: Pintura e Imageneria Románicas. Madrid: Plus Ultra. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Stephen J. 2001. The Cult of Saint Thecla: A tradition of Women’s Piety in Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Santiago Fernández, Javier. 2009. El hábito epigráfico en la Hispania visigoda. In VIII Jornadas Científicas Sobre Documentación de la Hispania Altomedieval (siglos VI–IX). Edited by Nicolás Ávila Seoane, Manuel Joaquín Salamanca López and Leonor Zozaya Montes. Madrid: Dpto. de Ciencias y Técnicas Historiográficas, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, pp. 291–344. [Google Scholar]

- Del Amo Guinovart, Mª Dolores. 1997. Tecla et Theclae. De la santa de Iconio a la beata tarraconense. In El temps sota control. Homenatge a F. Xavier Ricomá Vendrell. Tarragona: Diputació de Tarragona, pp. 123–29. [Google Scholar]

- Del Amo Guinovart, Mª Dolores. 2001. Obispos y eclesiásticos de Tarraco desde inicios del Cristianismo a la invasión sarracena del 711 d.C. Butlletí Arqueològic 23: 259–80. [Google Scholar]

- Dewald, Ernest. 1915. The Iconography of the Ascension. American Journal of Archaeology 19: 277–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz y Díaz, Manuel Cecilio. 1967. Entorno a los orígenes del Cristianismo hispánico. In Las raíces de España. Edited by José Manuel Gómez Tabanera. Madrid: Instituto Español de Antropología, pp. 423–43. [Google Scholar]

- Drescher, James. 1946. Apa Mêna: A Selection of Coptic Texts Relating to St. Menas. Cairo: Publications de la Société d’archéologie copte. [Google Scholar]

- Escribano Paño, María Victoria. 1998. Zaragoza en la Antigüedad Tardía (285–714). Historia de Zaragoza 3. Zaragoza: Ayuntamiento. Servicio de Cultura. [Google Scholar]

- Ferotin, Marius, ed. 1904. Le Liber Ordinum en usage dans l’Église wisigothique et mozárabe d’Espagne du cinquième au onzième siècle. Paris: Firmin-Didot. [Google Scholar]

- Ferran, Domènec. 2009. Ecclesiae egarenses. Les esglésies de Sant Pere de Terrassa. Barcelona: Lunwerg. [Google Scholar]

- Ferran, Domènec. 2015. Les pintures murals de l’absis de Sant Miquel. Anàlisi iconogràfica. Terme 30: 118–25. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzerald Johnson, Scott. 2006. The Life and Miracles of Thecla. A Literary Study. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Flórez, Enrique. 1754. España Sagrada, Teatro geográfico-histórico de la Iglesia de España. Tomo III. Madrid: En la oficina de Antonio Marín. [Google Scholar]

- Flórez, Enrique. 1770. España Sagrada, Teatro geográfico-histórico de la Iglesia de España. Tomo XXV. Madrid: En la oficina de Antonio Marín. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Llinares, Gemma, Antonio Moro, and Francesc Tuset. 2009. La Seu Episcopal d’Égara. Arqueologia d’un conjunt cristià del segle IV al segle IX. Serie Documenta 8; Tarragona: Institut Català d’Arqueologia Clàssica. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Llinares, Gemma, Antonio Moro, and Francesc Tuset. 2015. L’edifici funerari de Sant Miquel. Terme 30: 75–100. [Google Scholar]

- Gomá, Isidro. 1907. Fundamentos históricos del culto a S. Pablo y Sta. Tecla. Boletín Arquológico de la Real Sociedad Arqueológica Tarraconense VII: 669–94. [Google Scholar]

- Grabar, André. 1945. Une fresque visigothique et l´iconographie du silence. Cahiers Arqueologiques 1: 124–28. [Google Scholar]

- Grabar, André. 1958. Ampoules de Terre sainte (Monza-Bobbio). Paris: Klincksieck. [Google Scholar]

- Grabar, André. 1970. Deux portails sculptés paléochrétiens en Egipte et d’Asie Mineure, et les portails romans. Cahiers Archéologiques XX: 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gros i Pujol, Miquel dels Sants. 1992. Les Wisigoths et les liturgies occidentales. In L’Europe héritiére de l’Espagne wisigothique—Rencontres de la Casa de Velázquez. Edited by Jacques Fontaine. Madrid: Casa de Velázquez, pp. 125–35. [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann, Peter. 1989. Abu Mina I: Die Gruftkirche und die Gruft. Mainz am Rhein: P. von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann, Peter. 1998. The Pilgrimage Center of Abu Mina. In Pilgrimage and Holy Space in Late Antique Egypt. Edited by David Frankfurter. Leiden: Brill, pp. 291–302. [Google Scholar]

- Guardia, Milagros. 1992. La pintura mural pre-romànica de les esglésies de Sant Pere de Terrassa. Noves propostes d’estudi. In Actes del I Simposi Internacional sobre les Esglésies de Sant Pere de Terrassa (20–22 de novembre de 1991). Terrassa: Centre d’Estudis Històrics-Arxiu Històric Comarcal, pp. 153–60. [Google Scholar]

- Iacobini, Antonio. 2000. Visione dipinte. Immagini della contemplazione negli affreschi di Bawit. Roma: Viella. [Google Scholar]

- Keay, Simon. 1996. Tarraco in Late Antiquity. In Towns in transition. Urban Evolution in Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages. Edited by Neil Christie and Simon T. Loseby. Aldershot: Scolar, pp. 18–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, Charles Louis. 1928. Notes on Some Spanish Frescoes. Art Studies 6: 123–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, Charles Louis. 1930. Romanesque Mural Painting of Catalonia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, Magdalena. 2014. Coptic music culture. Tradition, structure, and variation. In Coptic Civilization. Two Thousand Years of Christianity in Egypt. Edited by Gawdat Gabra. Cairo-New York: The American University in Cairo Press, pp. 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- López Vilar, Jordi, and Diana Gorostidi. 2015a. Les inscripcions visigodes de l’absis de Sant Miquel. Terme 30: 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- López Vilar, Jordi, and Diana Gorostidi. 2015b. Noves consideracions sobre la inscripció tarraconense de la beata Thecla (segle V). Pyrenae 46: 131–46. [Google Scholar]

- Mac Coull, Leslie. S. B. 1986. Redating the Inscription of El-Moallaqa. Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 64: 230–34. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, Henry. 1977. The Depiction of Sorrow in Middle Byzantine Art. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 3: 123–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancho, Carles. 2012. La peinture murale de haut Moyen Âge en Catalogne (IX–X siècle). Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Mancho, Carles. 2018. La decorazione delle chiese di Sant Pere de Terrassa, esempio dell’uso politico di monumenti tardo-antichi nell’altomedioevo. Hortus Artium Medievalium 24: 152–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniche, Lisa. 1991. Music and Musicians in Ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maraval, Pierre. 1982. Égérie. Journal de Voyage. Introduction, Texte Critique, Traduction, Notes, Index et Cartes. Paris: Éditions du Cerf. [Google Scholar]

- Martí i Bonet, Josep Maria. 1992. Els origens del Bisbat d´Égara. In Actes del I Simposi Internacional sobre les Esglésies de Sant Pere de Terrassa (20–22 de novembre de 1991). Terrassa: Centre d’Estudis Històrics-Arxiu Històric Comarcal, pp. 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Martí i Bonet, Josep Maria. 2004. Barcelona i Égara-Terrassa. In Història primerenca fins l’alta edat Mitjana de les dues Esglésies Diocesanes. Barcelona: Arxiu Diocesà. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Delgado Sánchez, José Manuel. 2018. El canto litúrgico en la reforma del rito mozárabe de Cisneros: Tradición, pervivencia y restauración. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad de Castilla-la Mancha, Cuenca, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Migne, Jacques Paul, ed. 1844–1855. Patrologia Latina. París. [Google Scholar]

- Mundó i Marcet, Ascani. 1992. El bisbat d´Égara de l´època tardo-romana a la Carolíngia. In Actes del I Simposi Internacional sobre les Esglésies de Sant Pere de Terrassa (20–22 de novembre de 1991). Terrassa: Centre d’Estudis Històrics-Arxiu Històric Comarcal, pp. 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Notre messe. 1963. Notre messe selon la liturgie copte dite de Saint Basile le Grand, 3e ed. rev. et corr. sous le Pontificat de S.B. Stéphanos Ier. Le Caire: Editions du Foyer Catholique. [Google Scholar]

- Papaconstantinou, Arieta. 2007. The cult of saints: A haven of continuity in a changing world? In Egypt in the Byzantine World. Edited by en Roger S. Bagnall. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 350–67. [Google Scholar]

- Peers, Glenn. 2007. Vision and community among Christians and Muslims: the al-Mu’allaqa lintel and its eight-century context. Arte Medievale 6: 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Pentcheva, Bissera. 2000. Imagined Images: Vision of Salvation and Intercession in Double-Sided Icon from Poganovo. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 54: 139–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijoan, Josep, and Josep Gudiol. 1948. Les pintures murals romàniques de Catalunya. In Monumenta Cataloniae. Barcelona: Alpha, vol. IV. [Google Scholar]

- Pinell, Jordi. 1998. Liturgia Hispánica. Barcelona: Centre de Pastoral Litúrgica. [Google Scholar]

- Presedo Velo, Francisco. 2003. La España Bizantina. Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla. Secretariado de Publicaciones. [Google Scholar]

- Puig i Cadafalch, Josep. 1931. Les peintures du VIe siècle de la cathédrale d’Egara. Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions &Belles-Lettres 75: 154–62. [Google Scholar]

- Puig i Cadafalch, Josep. 1932a. Les pintures del segle vie de la catedral d’Egara (Terrassa) a Catalunya. Butlletí dels Museus d’Art de Barcelona vol. II: 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Puig i Cadafalch, Josep. 1932b. Les pintures del segle vie de la catedral d’Egara (Terrassa) a Catalunya. Arxiu del Centre Excursionista de Terrassa any XIV, 2ª ep. n°80: 86–91. [Google Scholar]

- Puig i Cadafalch, Josep. 1936. Les pintures del segle vi de la catedral d’Egara (Terrassa). Anuari de l’Institut d’Estudis Catalans VIII: 141–49. [Google Scholar]

- Puig i Cadafalch, Josep. 1948. Noves descobertes a la catedral d’Ègara. Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans. [Google Scholar]

- Ranesi, Rudi, Lourdes Domedel, and Conxa Armengol. 2004. Projecte de Restauració de les Pintures Murals de Santa Maria de Terrassa. Terrassa. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez G. de Ceballos, Alfonso. 1965. El reflejo de la liturgia visigótico-mozárabe en el arte español de los siglos VII al X. Miscelánea Comillas: Revista de Ciencias Humanas y Sociales 21: 293–327. [Google Scholar]

- Roig Buxó, Jordi, Coll Riera, Joan Manuel, and Josep-A. Molina i Vallmitjana. 1995. L’església vella de Sant Menna. Sentmenat del segle V al segle XX. Sentmenat: Ajuntament. [Google Scholar]

- Sacopoulo, Marina. 1957. Le linteau copte dit d’Al-Moallaka. Cahiers Archeologiques 9: 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Schiller, Gertrud. 1971. Ikonographie der christlichen Kunst. Gutersloh: Gutersloher Verlagshaus Gerd Mohn. [Google Scholar]

- Schlunk, Helmut. 1945. Relaciones entre la Península Ibérica y Bizancio durante la época visigoda. Archivo Español de Arqueología 18: 177–204. [Google Scholar]

- Schlunk, Helmut. 1964. Byzantinische Bauplastik aus Spanien. Madrider Mitteilungen 5: 234–54. [Google Scholar]

- Schlunk, Helmut. 1971. La iglesia de San Gîao, cerca de Nazaré. Contribución al estudio de la influencia de la liturgia de las iglesias prerrománicas de la península Ibérica. In Actas do II Congresso Nacional de Arqueología. II. Coimbra: Ministério de Educação Nacional, pp. 509–28. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Victor. 1991. Ascensione. In Enciclopedia dell’Arte Medievale. II. Rome: Enciclopedia Italiana, pp. 572–77. [Google Scholar]

- Semoglou, Athanasios. 2012. La théophanie de Latôme et les exercices d‘interprétations artistiques durant les ‘renaissances’ byzantines. Les noveuax signifiants de (la vision de) Dieu. Paper presented at Byzantium Renaissances: Dialogue of Cultures, Heritage of Antiqiuty Tradition and Modernity, Warsaw, Poland, 19–21 October 2011; Edited by Michal Janocha, Aleksandra Sulikowska and Irina Tatarova. pp. 231–39. [Google Scholar]

- Semoglou, Athanasios. 2014. H Θέκλα στην αυγή του Χριστιανισμού: εικονογραφική μελέτη της πρώτης γυναίκας μάρτυρα στην τέχνη της Υστερης Aρχαιότητας. Thessalonikē: Aristoteleio Panepitēmio Thessalonikēs, Kentro Vyzantinōn Ereunōn. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, James. 1967. The Meaning of ‘Maiestas Domini’ in Hosios David. Byzantion 37: 143–52. [Google Scholar]

- Soler i Jimenez, Joan. 2003. El territori d´Égara, des de la Seu Episcopal fins al Castrum Terracense (segles V–X). Alguns residus antics en la toponímia altmedieval. Terme 18: 59–95. [Google Scholar]

- Soler i Palet, Josep. 1928. Egara-Terrassa. Terrassa: Tallers Gràfics Joan Morral. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Edward Arthur. 2014. Los godos en España. Madrid: Alianza Editorial. First published 1971. [Google Scholar]

- TRACER. 2009. Memoria Final de Restauración de las Pinturas Murales del ábside de la Iglesia de Santa María de Terrassa (Barcelona). Madrid: Diputación Foral de Álava. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo Girvés, Margarita. 2003. Los exilios de católicos y arrianos bajo Leogivildo y Recaredo. Hispania Sacra 55: 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo Girvés, Margarita. 2004. El exilio bizantino: Hispania y el Mediterráneo occidental (siglos V–VII). In Bizancio y la Península ibérica. De la antigüedad tardía a la Edad Moderna. Edited by Inmaculada Pérez Martín and Pedro Bádenas de la Peña. Madrid: CSIC, pp. 117–54. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo Girvés, Margarita. 2012. Hispania y Bizancio. Una relación desconocida. Madrid: Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Meer, Frédéric. 1938. Maiestas Domini: Theophanies de l’Apocalypse dans L’Art Chrétien—Etude sur les Origines d’una iconographie spéciale du Christ. Paris and Roma: Citta del Vaticano, Roma, Pontificio istituto di archeologia cristiana. [Google Scholar]

- Vilaseca, Lluís, and Núria Guasch. 2004. Diagnosi de materials de les pintures murals de la cúpula de l’església de Santa Maria de Terrassa. In Projecte de Restauració de les Pintures Murals de Santa Maria de Terrassa. Edited by Rudi Ranesi, Domedel Lourdes and Armengol Conxa. Terrassa. [Google Scholar]

- Vinulović, Ljubica. 2018. The Miracle of Latomos: From the Apse of the Hosios David to the Icon from Poganovo. In The Migration of the Idea of Salvation, Migrations in Visual Art. Edited by Jelena Erdeljan, Martin Germ, Ivana Prijatelj Pavičić and Marina Vicelja Matijašić. Belgrade: University of Belgrade, pp. 175–86. [Google Scholar]

- Vives, José. 1963. Concilios Visigóticos e Hispano-Romanos. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Instituto Enrique Flórez. [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaíno Sánchez, Jaime. 2009. La presencia bizantina en Hispania (siglos VI-VII). La documentación arqueológica. Murcia: Universidad de Murcia. [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaíno Sánchez, Jaime. 2013. Hispania y Oriente durante el período de ocupación bizantina (siglos VI-VII). La documentación arqueológica. In El Oriente griego en la Península Ibérica. Epigrafía e Historia. Edited by María Paz de la Hoz and Gloria Mora. Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia, pp. 281–305. [Google Scholar]

- Weitzmann, Kurt. 1976. The Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai. The Icons I: From de the sixth to the tenth Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, John. 1971. Egeria’s Travels. London: SPCK. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The minutes of the Council of Santa Maria Maggiore, the letters of the bishops of Tarragona and the response from Pope Hilarius are found in the Collectio Canonum Hispania from the 7th century, the work of Saint Isidoro in the year 634. See (Migne 1844–1855, pl. 58, col. 12–20; 67, col. 315–20). |

| 2 | Egara Weekly Magazine, Year I, núm.5. Terrassa, 25 December 1892. |

| 3 | See (ARCOR 2001, 2002). Information preserved in the archive of the Museum of Terrassa. |

| 4 | In pagan monuments, the Sun was represented as a radiated disc, or in Syria as a rosette with outspread petals, or as a cross limited by points. The Moon, for its part, appears represented as a rosette in the form of a helix or in its crescent shape, at times alone and at other times inscribed in a circle. These representational forms were quickly adopted by Christian artists, and we have preserved good examples of them in the Rabbula Gospels (6th century). |

| 5 | Christe (1969, p. 69), Mancho (2012, pp. 343–94), and Ferran (2015) accepted the identification of the theme as that of the Ascension. |

| 6 | Regarding the iconography of the Ascension, see (Dewald 1915; Van der Meer 1938, pp. 185–88, 196–98; Belting-Ihm 1960, pp. 95–112, 1989, pp. 43–59; Schiller 1971, pp. 141–64; Schmidt 1991, pp. 572–77). |

| 7 | Regarding the ampullae from the Holy Land housed in Monza and Bobbio, see (Grabar 1958). |

| 8 | For the latest published studies on the pictorial decoration of Bawit, see (Iacobini 2000). The author considers that in the images of Bawit, there is a hierarchic relationship between the different textual sources, with the vision of Ezequiel as their primary source of inspiration (Iacobini 2000, pp. 107–19). On the contrary, Van der Meer (1938, pp. 266–71) proposed a liturgical matrix for the theophanies of Chapels XVII and XXVI of Bawit. The presence of the Trisagion in the book of Christ leads him to think that the theophanies of Bawit are the evocation that figures in the introduction of the Trisagion sung in the liturgy. |

| 9 | Regarding the mosaic of Hosios David see (Snyder 1967, pp. 145–52; Pentcheva 2000, pp. 139–53; Semoglou 2012, pp. 231–39; Vinulović 2018, pp. 175–86). |

| 10 | Dewald recognized three predominant iconographic types within Carolingian art: (1). Christ ascending to the top of a mountain top in the presence of angels, the Apostolic College and the Virgin; (2). Christ, shown with his back to the spectator, walking toward the top of a mountain of rocks and raising his left hand to Heaven; and (3) Christ emerging between the disciples and raising his left hand toward the dextera domini. See (Dewald 1915, pp. 296–97). |

| 11 | |

| 12 | See the example of San Pedro de la Mata (Casalgordo, Sonseca, Toledo) or of Santa María de Melque (San Martín de Montalbán, Toledo). |

| 13 | “There dwells all the fullness of the Godhead, on the peak of truly heavenly Sinai/[…]the angels and they ceaselessly honor him with thrice-holy voice singing and saying: Holy, holy, holy are you, O lord: heaven and earth are full of your holy glory/For the are filled with your greatness, O Lord of great mercy, as you are invisible in the heavens amidst manifold powers, and you were content to dwell together with us mortals/ having become incarnate from the Mother of God, Mary, who has never known man. Be a helper to Abba Theodore the patriarch and George the deacon and oeconomus. Pachon 12, indiction 3, year of Diocletian 451”. Transcription by Mac Coull (1986). |

| 14 | Carles Mancho considers the Apostles to not be kneeling, but rather seated (Mancho 2012, p. 375), and compares the paintings of Sant Miquel with a Reichenau Gospel from the first quarter of the 9th century (Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Cod.lat. 23631, fol. 197r), which represents the Apparition of Christ to the Disciples (John 20, 19–23). |

| 15 | According to Maguire, in Middle Byzantine art the hand clasped to the mouth in depictions of the Ascensions means simple silence or speechlessness. He refers to the mid-9th century fresco of the Ascension in S. Clement in Rome, where one of the apostles standing on the right of the scene claps one hand over his mouth, while in his other he hold a scroll. An explanation of his actions may found in a poem by the 7th-century Pope Honorius I, which describes “The Apostles in Amazement at the Ascension of Christ to the Heavens”. The apostles also cover their mouths with their hands in the tenth-century Ascension painting at Ayvali Kilise in Cappadocia. See (Maguire 1977, pp. 123–74). About the gesture in Byzantium see also (Brubaker 2009, pp. 36–56). |

| 16 | The Trisagion is an echo of the biblical passage in which the seraphim sing out to the Lord: “Holy, Holy, Holy is the Lord God Almighty” (Isaiah 6,3). It is repeated in the Apocalypse: “Holy, Holy, Holy is the Lord God Almighty who was, and is, and is to come” (Apocalypse 4,8). It emerged in Eastern Christianity and was often used as an instrument to combat the heresies that cast doubt on the dual nature of Christ. From the primitive form of Trisagion, Hispanic priests wrote new texts emphasizing the power and royalty of Christ through the use of Apocalyptic texts. Documented for the first time at the Council of Chalcedon (451), it was introduced to the Hispano-Mozarabic liturgy due to the influence of the Eastern liturgies (Pinell 1998, pp. 152–53; Martín-Delgado Sánchez 2018, pp. 64–65), and was recited by ministers serving at the altar, by clerics of the choir and by worshippers. |

| 17 | Proof of the term in the East resides in an icon housed in the picture gallery of the Monastery of Santa Caterina del Sinai (7th century), where the image of a majestic Christ appears joined by the inscription E[MMA]NOYHA. See (Weitzmann 1976, p. 41, n.B16). |

| 18 | According to the Júlia Bertrán de Heredia, it is very probable that when the Visigoths installed themselves in Barcino, they would have occupied the official episcopal nucleus, which today is under the present cathedral and under the Plaza del Rey, and that the Catholics were ousted to Sant Just i Pastor, where an older Church probably already would have existed, a fact that would justify the relocation of the Catholic Episcopal group to this part of the city. |

| 19 | Three canons were approved at the Council, stating that presbyters and deacons should be reordained and that Arian churches that had been reconsecrated by Arian bishops without receiving the blessing of a Catholic Bishop must be reconsecrated. See (Vives 1963, pp. 154–55; Escribano Paño 1998, p. 85). |

| 20 | I do not share a belief in the proposal set forth by Professor Carles Mancho, who considered the paintings of Sant Miquel to have been commissioned by the Bishop of Barcelona, Frodoí (861–890), as a response to the clerics adhering to the ancient Hispanic liturgy, who had attempted to usurp episcopal rights of those accused of heresy. For that, he would have used the theme of the Ascension, which would equate the Hispanic rite with the Adoptionist heresy, a doctrine that argued that Christ would have been elevated to a category of the divine by appointment by God himself through his adoption. I believe that this hypothesis does not take two important premises into account. On one hand, Elipando, Archbishop of Toledo and one of the main defenders of the Adoptionist heresy, died in the year 805 at the See of Toledo with no disciple to continue his thesis. On the other, in the year 794 at the council of Frankfurt and presided by Charlemagne himself, Adoptionism was condemned. Consequently, the conflict involving Adoptionism would be very far from the time of Frodoí. |

| 21 | For further information of the reception of Western Liturgies see: (Díaz y Díaz 1967; Blázquez Martínez 1967; Gros i Pujol 1992). |

| 22 | Hormisdas, Ep. 24, ad Ioannem Tarraconensem, PL 63,422 i 84, 819–820: “Salutantes igitur caritatem qua jungimur, per Cassianum diaconum tuum signifi camus, nos direxisse generalia constituta, quibus vel ea quae juxta canones servari debeant competenter ediximus, vel circa eos qui ex clero Graecorum veniunt, quam habere oporteat cautionem, suffi cienter instruximus”. In the same letter, Hormisdas expressed that Ioannes deserved the affection of Christians due to his loyalty to the norms of the Catholics and the Fathers. Consequently, he conferred the mission to restore Hispanic churches to the ancient discipline: “remuneramus sollicitudinem tuam, et conservados privilegiado metropolitanorum vices vobis Apostolicae sedis eatenus delegamus.” We can deduce that in Hispania there existed situations of heresy, opposed to the Catholic faith. See (Amengual i Batlle 2013; Gomá 1907, pp. 689–93; Del Amo Guinovart 2001, p. 275). |

| 23 | Among the rites most profoundly marked by an Eastern-Byzantine influence, the Greek Trisagion specifically figures (Presedo Velo 2003, p. 116), a rite which Van der Meer saw as the source of the theophanic images from Coptic Egypt, with which Terrassa has an undeniable bond. |

| 24 | According to the latest studies (López Vilar and Gorostidi 2015b), no relationship exists between this Thecla and the cult of worship in place during the medieval period of Santa Tecla as patron saint of Tarragona, contrary to what some authors have proposed (Del Amo Guinovart 1997). |

| 25 | |

| 26 | |

| 27 | For a general description and study of the cult of Santa Tecla, see (Davis 2001; Fitzerald Johnson 2006, pp. 67–112; Semoglou 2014). |

| 28 | By the sixth century, Abu Mina had been transformed into a huge pilgrimage center whose focal point was the tomb of the martyr. See (Drescher 1946; Grossmann 1989, 1998, pp. 291–302; Papaconstantinou 2007, pp. 350–67). |

| 29 | |

| 30 | We only know of two churches in Catalonia dedicated to Saint Menas: Sant Mena de Sentmenat (Vallès Occidental) and Sant Mena de Vilablareix (Girona). |

| 31 | According to the restorers, this technique is different from the traditional Roman fresco technique described by Vitruvius and is also different from Catalonian Roman frescoes, which have a finer arriccio and a regular thickness in the layer covering it. See (ARCOR 2001, 2002). |

| 32 | See (Ranesi et al. 2004). The paintings of Santa Maria were finally restored in the years 2008 and 2009 by the TRACER company (TRACER 2009, p. 42). |

| 33 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez Márquez, C. Singing to Emmanuel: The Wall Paintings of Sant Miquel in Terrassa and the 6th Century Artistic Reception of Byzantium in the Western Mediterranean. Arts 2019, 8, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040128

Sánchez Márquez C. Singing to Emmanuel: The Wall Paintings of Sant Miquel in Terrassa and the 6th Century Artistic Reception of Byzantium in the Western Mediterranean. Arts. 2019; 8(4):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040128

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez Márquez, Carles. 2019. "Singing to Emmanuel: The Wall Paintings of Sant Miquel in Terrassa and the 6th Century Artistic Reception of Byzantium in the Western Mediterranean" Arts 8, no. 4: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040128

APA StyleSánchez Márquez, C. (2019). Singing to Emmanuel: The Wall Paintings of Sant Miquel in Terrassa and the 6th Century Artistic Reception of Byzantium in the Western Mediterranean. Arts, 8(4), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040128